- College of Education, Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, MI, United States

There exists much potential for the use of community-based partnerships to support preservice teachers' learning and development. These opportunities can also expand preservice teachers' understanding of when and where teaching and learning take place. This paper reports the results of a qualitative, yearlong pilot study focused on secondary preservice teachers' (N = 42) weekly community-based field experiences at a newly opened secondary public museum school, located in a large Midwestern urban area. Specifically, preservice teachers worked weekly with sixth grade students in an urban public museum setting as part of a required undergraduate content area literacy teacher education course. This study highlights ways this community-based field experience served as an important clinical component for preservice teacher learning. Working in this community-based setting provided expanded and varied opportunities for preservice teacher learning, including practice using and facilitating small group instruction and opportunities to support adolescents' learning through accessing, exploring, and examining museum artifacts and exhibits. Therefore, community-based field experiences, when and where feasible, may serve as an important clinical component for preservice teacher learning.

I really like that I get to work with a small group of students. It's a fresh experience on teaching that I don't get in my [pre-student teaching] placement. It allows me to get to know the students better because I have more time with each individual student. I also appreciate that we are able to use the [museum] exhibits to enrich their experiences.

–Preservice teacher participant.

Introduction

Field-based experiences are a central tenant of global teacher education, in which preservice teachers transition from theory to practice (Ball and Cohen, 1999). Whether in conjunction with educational foundations courses, methods classes, or practica-centered internships, preservice teachers in many countries are often placed in local PK-12 classrooms to observe and work with PK-12 teachers and students (Burn and Mutton, 2015). The assumption is that these field experiences will enable preservice teachers to better understand and facilitate their own transition from student to classroom teacher (Heafner et al., 2014). The purpose of these placements is for preservice teachers' experiences to be what Ball and Cohen (1999) term, “practice-based teacher education,” which roots preservice teachers' experiences and learning directly within formal learning settings such as PK-12 schools and classrooms (Forzani, 2014).

According to McDonald et al. (2011), field experiences that take place outside traditional PK-12 settings, such as community-based field experiences may also be used to support and extend “practice-based teacher education.” Community-based settings include informal learning settings, such as parks, neighborhoods, libraries, wetlands, museums, and local historical sites (Gruenewald and Smith, 2010). For example (Hamilton et al., in press), found that community-based field experiences in settings such as public museums, children's museums, and construction sites served to provide preservice teachers additional opportunities to apply pedagogy and engage in varied teaching practices. As a result, preservice teachers' understanding of when and where teaching and learning take place expanded. Additionally, there is a need for and value of expanding preservice teachers' field experiences beyond traditional school settings to settings within the broader community as evidenced in Barchuk et al. (2015) study of preservice teachers working in a community-based field experience in an African Nova Scotian community as well as Harkins and Barchuk's (2015) examination of preservice teacher learning in diverse practicum settings such as non-profit, government-affiliated health care institutions, museums, community colleges, as well as environmental and humanitarian organizations. Expanding field experiences to include community-based settings further informs preservice teachers' understanding and awareness of when and where teaching and learning take place, allowing them see and experience teaching and learning pedagogy and practice beyond traditional PK-12 school settings (Hamilton et al., in press; McGregor et al., 2010; Brayko, 2013; Harkins and Barchuk, 2015).

Given the need for varied clinical field experiences, especially in community-based settings, there exists much potential for partnerships between museums, PK-12 schools, and teacher education programs to support preservice teacher learning. One way is through partnering with a public museum school. For the purposes of this study, the museum school model is one in which a public-school district or charter school authorizer partners with a local museum to embed a school within the museum itself (Institute of Museum Library Services., 2004). Such partnerships “blur institutional barriers and leverage the physical space, collections, exhibitions, and content knowledge of museums to broaden and deepen students' educational experiences” (p. 15). Including teacher education programs as part of this partnership may serve to support preservice teacher learning (Gupta et al., 2010; Stetson and Stroud, 2014). There exists a lot of research focused on partnerships between museums and PK-12 schools in which museums and its artifacts, exhibits, programs, and spaces are shared with PK-12 students on-site or in local PK-12 classrooms. This study responds to Conway et al. (2014) finding that preservice teachers need varied and purposeful opportunities for integrated “workplace learning” in settings the authors term, “learningplaces.” Such “learningplaces” settings exist to challenge, scaffold, and support preservice teacher learning and development. Moreover, this study is also a response to Zeichner's (2010, 2012) call for more studies focused on preservice teacher learning in community-based settings.

Theoretical Framework

According to Hallman and Rodriguez (2015), learning to teach is a complex and ongoing process in which preservice teachers have multiple opportunities to learn and also examine theory and pedagogy, which is accomplished when engaging in field experiences within formal and informal educational settings, such as community-based ones. Guillen and Zeichner (2018) suggest that teacher educators can help preservice teachers bridge theory and practice when working in settings outside traditional PK-12 educational environments. If preservice teachers are to expand their understanding of teaching and learning beyond “traditional” school settings, what Lortie (1975) termed “apprenticeships of observation,” they must participate in field experiences that provide experiences in settings different from those they experienced as PK-12 students (Brayko, 2013).

In reframing preservice teacher education and its field experiences, Zeichner (2010) used Bhabha's (1990) “third space” theory to argue for the inclusion of more community-based field experiences and sites within university teacher preparation programs. According to Zeichner (2010), these “third spaces” exist beyond college/university settings and traditional K-12 contexts, such as schools and learning centers. Zeichner suggests that these community-based sites function as a “third space” for teaching and learning, offering additional opportunities for preservice teacher learning, growth, and development. Some teacher education programs use community-based contexts as third spaces to embed and promote the use of community-based field experiences. In doing so, such spaces are intended to further augment preservice teachers' learning and deepen novice teachers' connections with and service to local communities. Some examples of “third space” community-based contexts include museums, nature preserves and parks, and history centers (Richmond, 2017).

Therefore, this study is informed by tenets of social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978; Lave and Wenger, 1991), specifically that learning and knowledge creation are socially constructed through experiences with others and the world (Vygotsky, 1978). Within preservice teacher education, field- and community-based experiences provide opportunities for preservice teachers to develop as beginning teachers as they socially construct understandings of teaching and learning as they learn from their experiences within the field. When preservice teachers have opportunities to socially construct understandings of teaching and learning through observation and trying different pedagogical moves in pre-student teaching field placements—something Grossman et al. (2009) term “approximations of practice”—they begin to develop clinical skills, including greater confidence, deeper understanding of pedagogy and practice, as well as automaticity of routines. When engaging in approximations of practice, preservice teachers have opportunities to move beyond the familiar and often comfortable role of student to that of teacher (Hamilton and Van Duinen, 2019).

Utilizing community-based field experiences to augment traditional PK-12 clinical field placements enables preservice teachers opportunities to socially construct their learning as they examine and assess teaching and learning within and across various contexts. In doing so, they engage in “legitimate peripheral participation” (Lave and Wenger, 1991) within those settings, adding to their understanding of teaching and learning as socially and culturally constructed processes and experiences (ten Dam and Blom, 2006). As members of teacher education classes and active participants in local schools and communities, preservice teachers should actively conceptualize and construct learning through university-based coursework and experiences in community- and field-based settings (Hamilton et al., in press).

Given the potential for preservice teacher learning and development in community-based settings, this study centers on preservice teacher learning within one such setting, namely a secondary public museum school located within a large, urban Midwestern public museum. This year long qualitative study, which focuses on the first year of a two-year study, centers on the following research questions:

1. What opportunities exist for preservice teacher learning in a community-based field setting?

2. What learning do preservice teachers report as a result of working with sixth-grade students in a community-based field setting?

Literature Review

Clinical Field Experiences

As noted previously, clinical field placements are intended to support preservice teachers' learning about the profession through an immersion into the places of education by engaging in activities central to the profession, such as observing, assisting, and teaching alongside practitioners. However, simply placing preservice teachers in places such as PK-12 schools and classrooms does not necessarily improve their preparation, pedagogy, or practice (Grossman and McDonald, 2008; Valencia et al., 2009; McDonald et al., 2014). Thus, varied and purposeful clinical field experiences within formal and informal learning settings, such as community-based settings, as well as ongoing opportunities to observe and reflect are part of learning to teach (Author, in press; Nichols, 2014; Hallman and Rodriguez, 2015).

Clinical field experiences are also an important component of teacher education programs. These field experiences, termed, “practice-based teacher education” (Ball and Cohen, 1999; Forzani, 2014) reflect a commitment on the part of teacher educators to ensure that preservice teachers have opportunities to practice skills, dispositions, and knowledge they acquire as part of their teacher education program. As such, clinical field experiences provide support and preparation for preservice teachers as they learn to teach and play a critical role in teacher preparation (Feiman-Nemser et al., 2014). However, for such preparation to be successful these experiences should include community-based settings (Guillen and Zeichner, 2018), such as community centers, museums, and other non-profit service agencies. These experiences should also be directly connected and applicable to preservice teachers' university coursework (Hamilton and Van Duinen, 2019).

The overall purpose of pre-student teaching field placements is somewhat universal, namely to provide preservice teachers with opportunities to transition from theory to practice (Darling-Hammond, 2014). Research indicates that early, diverse, and sustained field experiences are one key to a successful teacher education program (Coffey, 2010; Zeichner, 2010; Darling-Hammond, 2014). However, these contexts and experiences vary widely (National Council of Accreditation for Teacher Education., 2010; Forzani, 2014). Additionally, there is a growing movement for teacher education to be “turned on its head,” specifically connected to clinical field experiences and practice (Blue Ribbon Panel on Clinical Preparation Partnerships for Improved Student Learning., 2010).

According to Conway et al. (2014), clinical field experiences should connect “workplace learning” research with teacher education, so that clinical experiences and settings become “learningplaces” that directly support preservice teacher learning. Building on research connected to “learningplaces,” Gravett et al. (2019) note that although it can be complicated, developing relationships and partnerships with PK-12 schools serves to support field-based preservice teacher learning, particularly if such partnerships position PK-12 schools as “learningplaces” where preservice teachers' professional practice and knowledge is integrated, supported, and mentored. In doing so, “learningplace” settings support preservice teacher learning in the field through “communities of networked expertise” (as cited in Hakkarainen et al., 2004). This networked expertise reflects the interwoven, connected nature of learning from and with multiple stakeholders, such as: PK-12 teachers, administrators, parents, and students, teacher educators, and professionals in the community.

Field experiences also help preservice teachers develop a broader professional vision and understanding of PK-12 students, schools, and the cultural contexts in which teaching and learning is situated (Zeichner, 2012). These field experiences are of significant importance in urban teacher education, given the multifaceted and interconnected issues which exist in many urban school districts (Zeichner, 2010; Williamson et al., 2016). Moreover, urban districts and students offer teacher education programs and preservice teachers sources of expertise as well as opportunities to more fully understand and collaborate within the communities in which they work and serve (Zeichner et al., 2014; Emdin, 2016). As a result, connecting teacher education more centrally to clinical practice and the urban sites in which this practice occurs requires teacher educators to explicitly teach about and, when possible, work on-site within the actual clinical settings.

Community-Based Field Experiences

In their study of the University of Washington's Elementary Teacher Education Program (ELTEP) and the role community-based field experiences played in supporting preservice teachers, McDonald et al. (2011) found that community-based field experiences may serve to broaden preservice teachers' understanding of teaching and learning. As their findings indicate, community-based field experiences afford additional opportunities—beyond traditional PK-12 school settings—for preservice teachers to see and understand when and where teaching and learning occur. These settings also present opportunities for preservice teachers to socially construct knowledge and gain experience, both of which are necessary to expand preservice teachers' understanding of teaching and learning.

Community-based settings also function as “third spaces” Zeichner (2010), making them an important augmentation to traditional PK-12 field experiences. Zeichner studied campus-field programs across the United States that created “hybrid spaces in teacher education where academic and practitioner knowledge and knowledge that exists in communities come together…” (p. 89). The results of this study indicate that the purpose of explicitly including community-based settings as part of preservice teachers' field experience is so that preservice teachers have experiences teaching and learning in settings that are not directly connected to traditional PK-12 settings. Although some may argue that these community-based experiences include before or after school and/or lunch programs, these are still experiences situated within the familiar setting of a PK-12 school and, thus, do not serve to place and/or facilitate preservice teacher learning within a broader community-based context.

When working in community-based settings, preservice teachers have opportunities to “conceptualize their own learning and the learning of their students in new ways” (Hallman and Rodriguez, 2015, p. 100). This finding was the result of their study of a practice- and community-based field placement in which preservice teachers worked with youth through a partnership with an organization serving homeless families. Working in this community-based setting challenged participants to reconsider the role of “teacher.” As a result, preservice teachers identified ways social, economic, and cultural backgrounds of the homeless youth with whom they worked directly impacted these teaching and learning experiences.

Similarly, Danyluk and Burns (2016) study of Canadian preservice teachers who worked on a housing construction site during their student teaching semester supports the importance of community-based field experiences for preservice teachers. Through this experience, participants became co-learners with their mentor teachers and the 10th grade students with whom they worked. Based on findings from their study, these researchers suggest that community-based field experiences “hold real promise for developing the essential capacities and effective teaching practice needed for the twenty-first century and beyond” (p. 207).

Public Museums as Community-Based Settings

When teacher education courses and their corresponding field experiences are directly embedded in community-based settings, preservice teachers have opportunities and contexts for direct learning and application within an experiential environment (Zeichner et al., 2015; Guillen and Zeichner, 2018). In the United States, museums have a long-standing tradition of being centers of education and outreach (Lasky, 2009). For example, Rawlinson's, Nelson, Osterman and Sullivan (2007) 3-year study of the “Artful Citizenship” project highlights museum-school partnerships. Specifically, as part of schools' social studies curriculum, the museum-school partnerships embedded the use of museum artifacts in classrooms as a means of increasing participating at-risk third-fifth grade students' critical thinking and literacy skills. Results of the study indicate that students in the treatment group achieved higher scores on the state standardized tests in the areas of reading and math.

Another example of museums serving as a community-based setting is evidenced in Rahm's (2016) study of two Canadian sixth-grade teachers' experiences with school-museum partnerships. This partnership was in collaboration with the Supporting Montreal Schools Program, sponsored by the Ministry of Education of Quebec. This program was created to promote the educational success of disadvantaged students in Montreal, Canada. Findings indicated that these teachers' science-based pedagogy and practice were positively impacted through their museum-school partnerships. This partnership also made museum and community resources accessible to teachers and students in new, transformative ways.

As part of the United States Department of Education's Student Art Exhibit Program and through a joint effort between the Association of Art Museum Directors and the United States Department of Education, sixteen museum-school education programs from museums throughout the United States were featured at the opening of the student art exhibit “Museums: pARTners in Learning 2015” which featured works from participating PK-12 students whose teachers collaborated with participating museums (Balingit, 2015). Annually, the Institute of Museum Library Services. (2017) awards the National Medal for Museum and Library Service, the highest national award for museums and libraries. Of the 10 medals awarded in 2017, three were awarded to museums—all of which demonstrated innovative programming and partnerships aimed at supporting community and PK-12 student education.

Teacher Education and Public Museums

Museums have long been places of learning for PK-12 students and teachers. However, they may be underutilized as training grounds for preservice teachers, as there is a need for “more museum outreach through teacher preparation” (Rawlinson et al., 2007, p. 172). This finding comes from their study of the “Artful Citizenship” project, in which they recommend connecting and embedding preservice teacher education within museums to support preservice teacher learning and development. This is a finding also supported by Powell's (2012) study of the partnership between the Corcoran Gallery of Art Museum and the Corcoran College of Art and Design, located in Falls Church, Virginia. Participants designed and utilized an exhibit, “30 Americans” to engage a wide range of stakeholders, including PK-12 teachers and students. Connected to teacher education, as part of Corcoran College of Art and Design's “Arts 101” program, an outreach program aimed at supporting middle school students' learning through visual arts exploration, graduate Art Education preservice teachers partnered with Washington, D.C. middle school teachers and students to co-teach lesson plans they designed as well as work with middle school students on-site at the Corcoran Gallery of Art Museum. Presented as an exhibit with accompanying curriculum which promoted culturally responsive teaching and learning, the relationship between this museum and local middle schools allowed preservice teachers to plan lessons, co-teach, and engage students in museum-based educational programming.

Connecting teacher education to a museum setting, Wylder et al. (2014) studied a summer program involving gifted and talented elementary students enrolled in Florida State University Schools. This program required students to curate a yearlong, one-gallery exhibition at the Florida State University Museum and Fine Arts. Part of this program included a limited number of art education and preservice teacher interns who, at various points in the summer, assisted elementary students during the curation process. Considered a success, researchers suggested that a key component to facilitating relationships between external schools, preservice teacher education, and local museums is “an enthusiastic teacher partner who views the museum as a vehicle for teaching” (p. 94).

Another example of teacher education connected to museums is Stetson and Stroud's (2014) study focused on early elementary preservice teachers placed in the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History's public preschool. Results of this study indicate that working with preschool students within a public museum setting allowed for easy access to museum artifacts and exhibits as well as participation in student-centered, hands-on learning opportunities within the classrooms and the museum. Preservice teachers' motivation for teaching and their understanding of active, inquiry-based learning also increased as a result of their collective field placement experience in this museum preschool.

When working in museum settings, future teachers' thinking and learning is augmented through experiences with museum-based activities and curriculum development, a finding from Greenwood and Greenwood and Kirschbaum's (2014) study of a partnership between the Tsongas Industrial History Center in Lowell, Massachusetts and the University of Massachusetts Lowell Graduate School of Education. In this study, graduate teacher candidates had opportunities to participate in various workshops and generate units of study they could use in their future classrooms. Internationally, Seligmann's (2014) study of partnerships between museums and colleges of education in Denmark highlight ways preservice teachers collaborated with various museums to generate curricular materials and resources to support museum-based learning. Results of this study indicated that these partnerships further equipped preservice teachers with knowledge and understanding related to incorporating local museums into their future teaching. Thus, as Trofanenko (2014) notes, when teacher educators and museum personnel partner there exists opportunities for “cross boundary work” through community-based partnerships. Such partnerships, in addition to providing preservice teachers with a community setting in which teaching and learning occur that may also serve to enhance and expand preservice (and inservice) teachers' historical, communal, and cultural understandings.

Method

Site, Context, and Participants

Located in the second largest city in the Midwestern state in which this study took place, City Public Museum School (CPMS)1 opened in the fall of 2015 and enrolled 60 sixth graders. It was located within the City Museum and shared office and classroom space with the museum. The City Museum is the oldest and second largest public museum in the state and has more than 250,000 specimens and artifacts. Considered a “theme school,” CPMS is part of City Public Schools, the second largest urban school district in the state. Each year CPMS will add one grade until it is a fully functioning sixth-twelfth grade secondary school. Unlike other City Public Schools' theme schools which use student achievement data to determine student entrance, admittance to CPMS is based on parent/guardian choice and lottery selection. Midwestern University (MU) is a large, regional state university with a 4-year teacher preparation program that is located within walking distance of the CPMS.

This project is the result of a collaborative effort between the CPMS principal, its two sixth grade teachers and an MU professor (first author) who taught a required semester-long, three-credit secondary content area literacy course (ED 300), taken the semester before student teaching. During the academic year in which this pilot study took place, ED 300 students spent approximately 45–50 min/week during class working on-site at the CPMS with assigned small groups of sixth grade students. These small groups were termed “M&M groups,” which reflects the roles of the ED 300 student (i.e., “mentor”) and the sixth-grade students (i.e., “musees”). As outlined in the ED 300 syllabus for both courses, this partnership provided a community-based field experience opportunity.

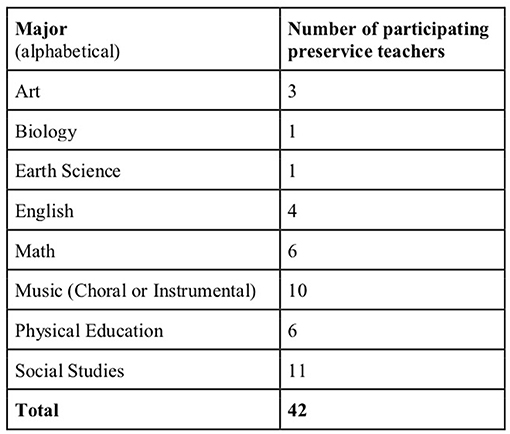

Given this community-based partnership, both MU and CPS Institutional Review Boards approved this study's protocol. Participants in this study included 4th year MU secondary preservice teachers (N = 42) enrolled in ED 300 during the fall (n = 28) or spring (n = 14) semester during the academic year this study took place. The difference in the number of students across sections and semesters is reflective of typical MU enrollment patterns for teacher education (i.e., more students enroll in the fall semester with intentions of student teaching and graduating in the spring semester than those who enroll in the spring semester and then wait to student teach and graduate until the following fall semester).

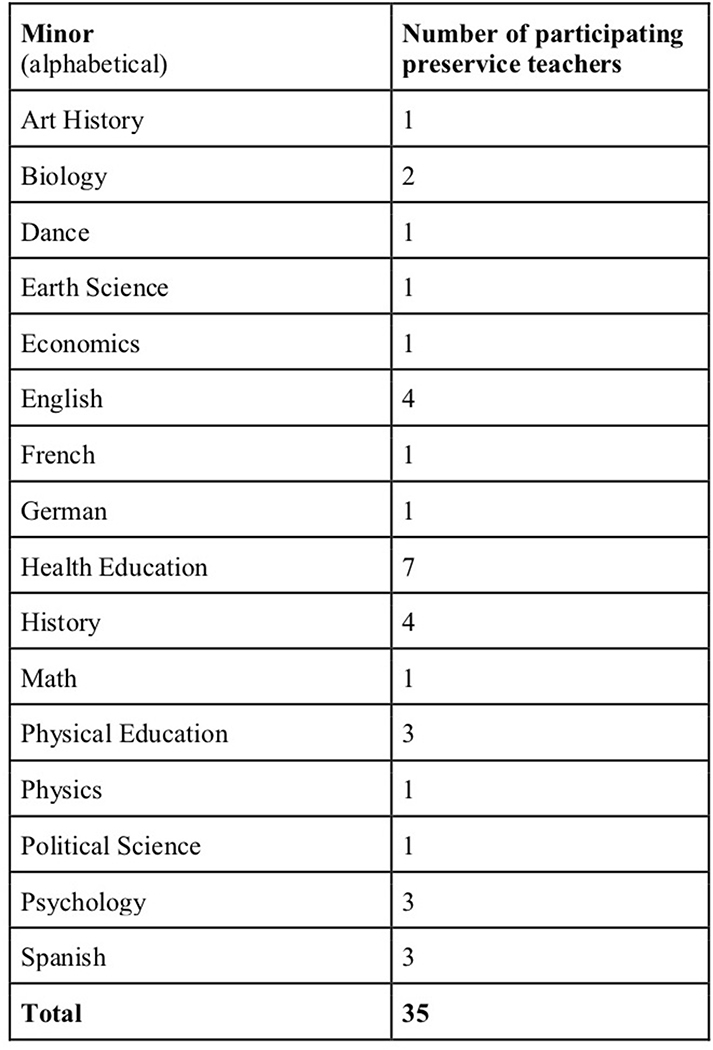

Participants' majors (Figure 1) and minors (Figure 2) varied during both semesters, which provided multiple disciplinary perspectives.

Figure 2. Participating preservice teachers' minors (due to personal choice and/or state certification requirements, some participants had more than one minor and others had no minor).

Although mentors' majors and minors are included here to reflect the diversity of participants' disciplinary backgrounds, we did not seek to study or compare their disciplinary perspectives or pedagogies. MU students' participation was voluntary and remained confidential until the completion of the semester (100% of preservice teachers enrolled in both semesters elected to participate). Participants also included the CPMS principal and its two sixth grade teachers (n = 3). Written informed consent was obtained from all MU and CPMS participants. Although CPMS sixth grade students were involved in the M&M groups, they were not considered research subjects and in accordance with national regulations as well as the MU and CPS ethics committees that approved this study's protocol, written informed parental/guardian consent was not required nor was a waiver of consent deemed necessary for CPMS sixth grade students.

Due to the variation in enrollment for each semester, as discussed previously, during the fall semester, M&M groups included one mentor (i.e., MU preservice teacher) and 2–3 musees (sixth grade students) per group. In the spring semester, because there were less preservice teachers enrolled in ED 300, M&M groups contained one mentor (i.e., MU preservice teacher) and 4–5 musees per group. Prior to each M&M group meeting, the partnering sixth-grade teacher utilized Google Documents to provide written directions, expectations, and necessary materials, which were shared by the ED 300 course instructor with mentors at the beginning of class. Throughout this placement, the ED 300 instructor and the CPMS partnering sixth grade teacher communicated regularly, co-planned when applicable, and worked to support each M&M group and member.

M&M groups were deliberately created based on the sixth grade students' needs and abilities (i.e., personality, social, emotional, academic, etc.). Additionally, the partnering sixth grade teacher also sought to match mentees with mentors, based on interests and major/minor emphases. Each M&M group was purposefully designed to optimize the mentor's and musees' learning and development. The substance of the work completed each week in the M&M groups purposefully aligned with the sixth-grade students' on-going work in their English Language Arts and Social Studies classes and included regular exploration of the City Museum, including specific exhibits and artifacts.

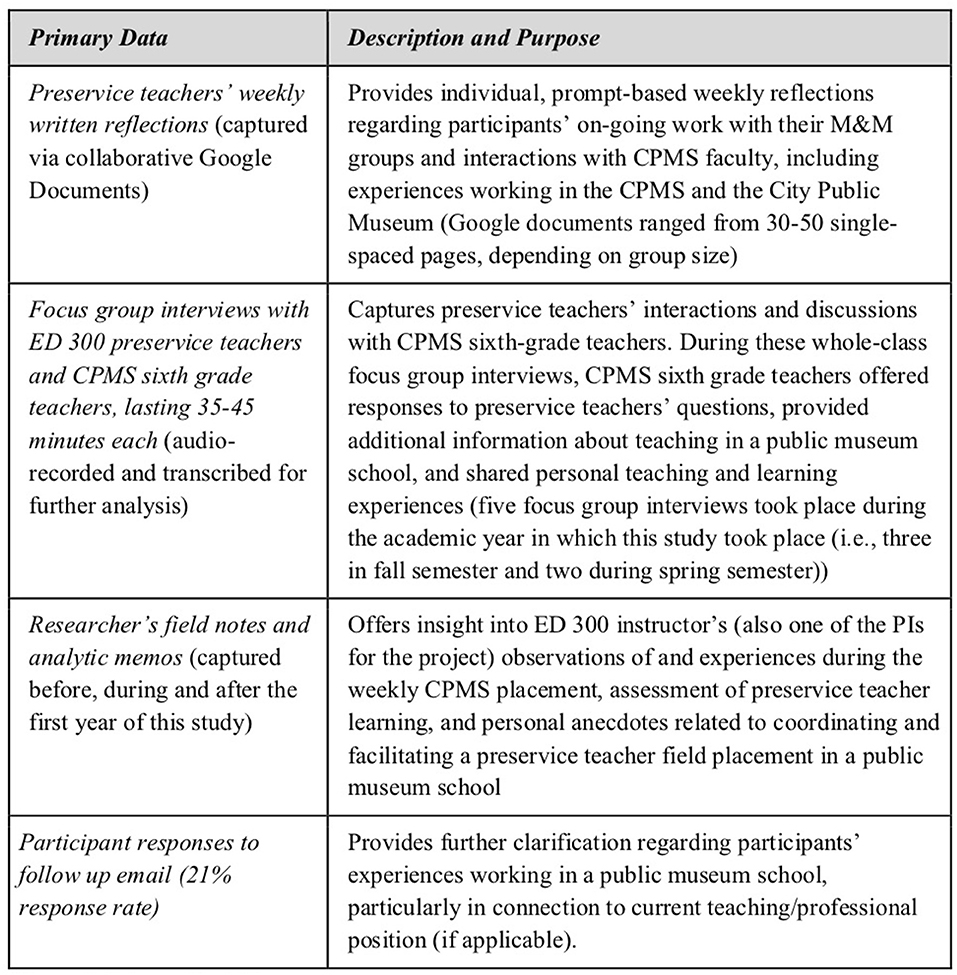

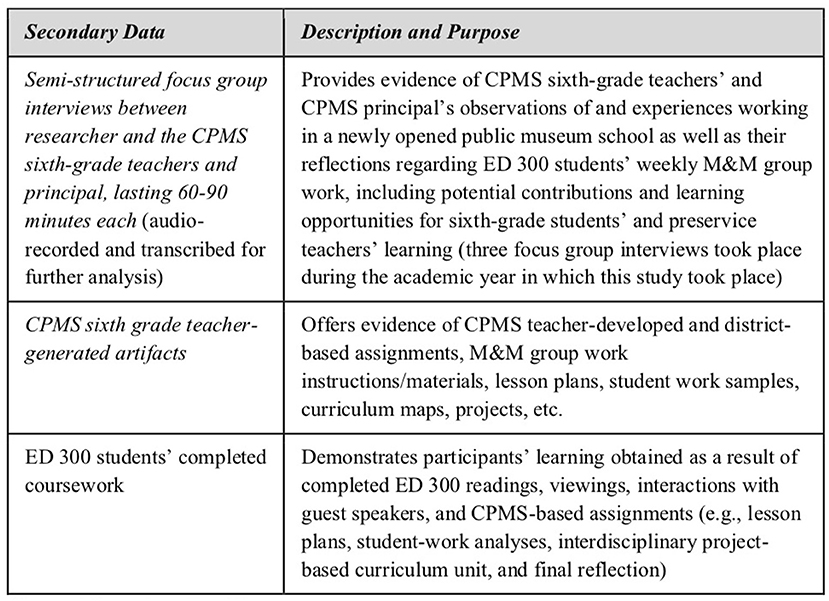

Data Sources

The data used to interpret and discuss the results to our research questions included both primary and secondary sources. Primary (Figure 3) and secondary (Figure 4) data sources were collected and analyzed to ascertain opportunities for preservice teacher learning within this community-based field experience.

Data Analysis

Given the clear line of preservice teacher education research that supports the importance of socially constructed learning through experience (Vygotsky, 1978), data were analyzed using Harkins and Barchuk's (2015) “approximations of practice” with attention to ways this community-based experience potentially served to support or challenge preservice teachers' apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). Moreover, the researchers also drew on Zeichner's (2010) conceptual use of “third spaces” as it related to the community-based setting and preservice teacher learning.

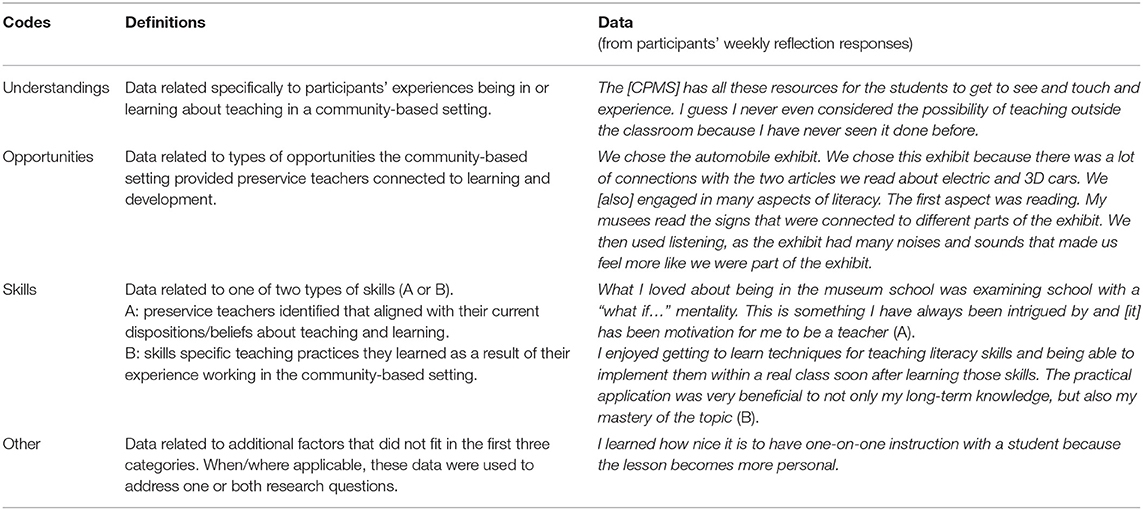

Data analysis of primary sources consisted of utilizing an interpretive approach through open coding (Miles et al., 2014) to first identify categories and then organize data, focused on preservice teacher learning in a community-based setting (i.e., public museum school). Participants' weekly written reflections were analyzed first, to identify and generate codes related to the two research questions. Analysis of these data included the use of content analysis (Newby, 2010; Miles et al., 2014) and constant comparative methodology (Corbin and Strauss, 2008), in which participants' weekly reflection responses were analyzed individually, first within their small groups and then within the context of their classmates' responses (within each semester). Finally, participants' responses across both semesters were analyzed and compared.

Based on recommendations by Creswell and Miller (2000) as well as Newby (2010), member checking was used to ensure trustworthiness and that data were appropriately analyzed. Participating preservice teachers were also asked to confirm the validity of the data by examining their weekly reflections and commenting on its accuracy. Additionally, researchers asked a focus group of participants to verify that the codes and themes made sense and were accurate representations of their experiences (Creswell and Miller, 2000).

To ensure coding reliability during the initial coding, an additional reviewer was utilized to maintain inter-coder agreement (Lombard et al., 2002). Utilizing the two research questions to guide the initial analyses, researchers sought to identify and understand the opportunities this community-based field experience presented as well as the learning preservice teachers reported as a result of working in this community-based setting. Connected to opportunities and preservice teacher learning, six categories were first identified but during additional rounds of analyses two categories were collapsed.

These four categories (Table 1) were then applied to the remaining primary data sources, and patterns within and across categories were also examined.

Data triangulation with secondary sources occurred using Corbin and Strauss's (2008) constant comparative method. Additionally, to increase the trustworthiness of the results (Creswell and Miller, 2000) an external auditor was utilized to examine the complete an audit trail (i.e., field observation notes, interview notes, participant weekly reflections, and all drafts of interpretation of data). Finally, including participant feedback maintains clarity and transparency between participants and researchers which serves to strengthen results and solidify interpretive validity (Johnson, 1997; Hamilton, 2016). Therefore, after the data analyses processes were completed, participants were contacted via email by the first author and invited to share their current teaching experiences as well as comment on findings. Of the 42 participants contacted, nine (21%) provided feedback which was considered and used in the revision processes.

Findings

In this section, findings are organized by the two research questions guiding this study, namely opportunities for preservice teacher learning in this community-based setting and preservice teacher learning as a result of working in this setting.

Unique Opportunities for Learning in a Community-Based Setting

Data analyses reveals that there existed a variety of opportunities for secondary preservice teacher learning in a public museum school. Of particular importance, working within a large, urban public museum, mentors (i.e., preservice teachers) and their musees (i.e., sixth graders) had opportunities to regularly explore, analyze, and discuss various permanent and traveling collections as well as museum exhibits and related artifacts. Having access to and facilitating adolescent learning in a public museum setting, preservice teachers had opportunities to directly link the sixth graders' learning outcomes in their English Language Arts and/or social studies classes to the museum through small group work and assigned tasks. In other words, the uniqueness of this community-based setting (i.e., a school located within a public museum) afforded participants regular opportunities to learn to teach through accessing, exploring and examining the museum's permanent and traveling exhibits as well as its many artifacts, something not available in traditional PK-12 settings. The experience of working in a public museum also expanded many preservice teachers' understanding of PK-12 schooling and when and where teaching and learning take place.

Moreover, some of the participants' “apprenticeships of observation” were challenged as a result of this community-based field placement experience. As Zeichner (2010) posits, additional opportunities for preservice teachers to learn, grow, and develop teaching and learning skills were afforded by teaching and learning in a third space, specifically the museum itself, especially the exhibits. For example, during the first semester when CPMS students engaged in writing a heritage story focused on their family history they first explored others' stories. With their M&M groups, MU mentors and their musees studied two permanent City Museum exhibits. The first centered on Native American tribes who first settled the land on which the city was later built and the other focused on the more than 45 ethnic groups who currently inhabit the city and its suburbs. As a result of exploring these exhibits and considering the actual location of the museum and the city in which this study occurred, participants reported that they were able to support their musees' learning through asking questions about the exhibits, pointing out specific artifacts, and inviting feedback connected to the content of the exhibits as it related to the sixth grade curriculum. In this instance, this place (i.e., the museum) allowed a different, more contextual and local connection to curriculum standards because the preservice teachers and the sixth-grade students engage in experiential learning. They interact directly with exhibits and artifacts in the place (i.e., the city) about which these exhibits showcase and teach. In contrast, when curriculum standards are taught in traditional secondary classrooms and schools, students most often learn content without the added benefit of experiencing it through direct immersion in exhibits and artifacts, directly tied to this content.

Additionally, MU students and their M&M groups explored one of the City Museum's permanent exhibits (i.e., a three-quarters scaled recreation of the city during the 1890's). Spending time in this exhibit challenged MU students to help their musees identify, discuss, and connect adolescents' twenty-first Century lived experiences with those who lived in the same city more than 130 years ago. Reflecting on the museum as a learning space (i.e., “learningplace”), one mentor explained, “I learned a bit about how to utilize the space you are in…[the City Museum] is a huge area and it provided many different opportunities to learn across the curriculum.” Another participant noted, “I love the public atmosphere the musees get to be in. These students are in the real world. The school is not some false atmosphere. It is the real deal. [CPMS] is a gold mine for student learning.” Similarly, after a class session one participant reflected, “the students can use their exhibits to learn and bring their education to life.” Reflecting on the opportunity to teach and learn in a public museum, another participant reported,

The [CPMS] has all these resources for the students to get to see and touch and experience. I guess I never even considered the possibility of teaching outside the classroom because I have never seen it done before. But working with the musees and seeing how much they know and how much they take in from their surroundings has been eye opening. I think so highly of [CPMS] and what they are doing for the students by introducing them to this different style of education.

As a result of the opportunity to work in this community-based setting [i.e., third space (Zeichner, 2010)] participants also reported having an expanded awareness of the additional affordances for teaching and learning within a public museum school and the public museum itself. The unique experiences encountered while learning in this third space appealed to preservice teachers as a way to connect sixth-grade students directly to the content, including building their schema and supporting new learning. Learning about teaching while in this third space seemed to allow pre-service teachers a place in which to connect seemingly abstract concepts to real, tangible exhibits, artifacts, and stories. As a result, there existed additional experiences, supports, and resources for both preservice and sixth-grade students' learning.

Some participants also shared that after spending time in the City Museum working with their M&M groups, they began to actively find ways to connect their M&M group work to the museum itself. Drawing on the affordances of being in a public museum school provided ready access to permanent and traveling exhibits, as well as artifacts. In connection to a personal narrative writing assignment their musees were working on, one participant explained how they connected a museum exhibit to support their musees' learning and literacy development. Specifically, as they were supporting the development of their musees' narrative writing, they explained:

Initially, I was going to just have them work on their writing….I told them that I would be available to answer any questions they had and we could take advantage of the time in that way. Then, as I sat for a moment and they began to write, I was thinking about whether or not that was the best way to help them right then and if doing that would help them best learn in the short amount of time we had together. I thought about how both of the students had great ideas but could use greater depth and details for their narratives or perhaps even a model. Then, I got a great idea! I thought of the “[name of the exhibit focused on people groups native to this area]” exhibit and how there were all kinds of personal immigrant stories that would serve as perfect models for [my musees'] stories. Though we didn't have very much time left for them to explore it, I figured it would be a great resource for them if they found something they wanted to look back at later since the exhibit is just right across from their classroom (one of the perks of being in a museum!). This teaches them autonomy, me thinking quick on my feet and risk-taking, and [it's] a way to make use of the space they get to learn in and I get to teach them in.

Connected to having the opportunity to work and teach in a public museum, another mentor reflected,

The [CPMS] is a land of endless teaching opportunities. Students have at their disposal materials that are thousands of years old that they can handle. If they cannot handle them, then students can walk to the exhibit and personally examine the object. Learning does not have to be done from an image when real history surrounds students….I dream about having the resources that the [CPMS] has to teach with.

Unlike more traditional PK-12 school field experiences, working in this community-based setting provided additional opportunities for preservice teachers to think in new and different ways about how to use the community-setting (i.e., a public museum) to support and extend adolescents' thinking and learning. As the CPMS principal explained during a focus group interview, “preservice teachers need to be made aware [of] the extent to which this type of education and the kind of experiential approach that we're talking about [here at the CPMS] really cuts against the grain.” When asked for clarification, both the CPMS teachers and principal agreed that preservice teacher field experiences in a public museum school, such as CPMS, provided an “exposure to possibility.” This “exposure” was a direct result of having an opportunity to teach in a community setting [Zeichner's (2010) third space], which served to open preservice teachers up to what else might be possible outside of a traditional PK-12 classroom.

Small Group Learning Experiences

In traditional PK-12 school settings preservice teachers often work with adolescents in classroom settings in which whole group or small group instruction takes place. Regardless of the model, these school-based field experiences are most often centered on experiencing and attending to an entire classroom of learners at the same time. In contrast to a typical PK-12 classroom field experience, the structure of the M&M groups and the format of the M&M group time (45–60 min each week) afforded preservice teachers with opportunities to support musees' learning through small group facilitation in a public space. For example, working in assigned small M&M groups MU preservice teachers assisted CPMS students with tasks such as reading and analyzing passages of text, completing projects, editing and revising writing assignments, and discussing and connecting current events to curriculum. An unanticipated finding related to preservice teacher learning emerged as a result of the M&M small group instructional model utilized in this community-based field experience. Specifically, preservice teachers learned how to facilitate and assess student learning in small group settings.

As noted earlier, the partnering CPMS sixth-grade teacher placed musees in small groups and assigned one MU preservice teacher to each M&M group. Given the weekly opportunity to work with the same group of sixth grade students throughout the semester, ED 300 students practiced establishing group expectations and norms, eliciting student thinking, managing and monitoring adolescents in a public space, and supporting musees' thinking, learning, and literacy development. As one participant noted after reflecting on their experiences working with their M&M group,

I really like the small group because it gives students more individualized instruction while still sharing different viewpoints. I learned how nice it is to have one-on-one instruction with a student because the lesson becomes more personal. I also started to think about reading in a different way because we were able to predict but my musee was also noticing things because she knows what happens, and I really like getting out of the classroom to do work because it just changes the scene, even though sometimes it can be distracting with all the stuff and people in the museum.

Connected to working with their musees in a small group setting throughout the semester, another mentor observed this about their own learning and growth as a teacher.

I really enjoy getting extra practice with the middle school age group. I like the fact that I get to spend one-on-one time for an hour [each week] with the same age group. I also like the small groups. It is a good way to practice teaching in small groups, and for it's a safe environment.

Another noted the importance of getting to know their musees in a small group setting, which supported the mentor's ability to support their students' learning.

In the M&M small group interactions, I've noticed that students get to voice their own opinions more. It's easier to have everyone answer a question when you are in smaller groups. It's also easier for the person leading the small group discussion to see where students are struggling because you get to know your students better.

Reflecting on semester-long experience working as a mentor in an M&M group one participant explained,

I really like that I get to work with a small group of students. It's a fresh experience on teaching that I don't get in my [regular teacher assisting] placement. It allows me to get to the know the students better because I have more time with each individual student. I also appreciate that we are able to use the [museum] exhibits to enrich their experiences.

Similarly, another mentor reported, “I learned on how to adapt and take charge in a small group by providing helpful feedback to my musees.”

In contrast to the mentors' concurrent 20 h per week teacher assisting placements in which they mostly engaged in whole class observation/instruction and management in local schools, the M&M small group instructional model offered MU preservice teachers with opportunities to engage in approximations of practice and learning related to small group management and student engagement. As one mentor explained in the end-of-semester reflection about their experiences working in their M&M group in this community-based setting, “this is a unique way for the preservice teachers to get more individualized experience with their musees (than at their [traditional field] placements) and for the musees to get lots of academic attention and feedback.” Furthermore, as one of the CPMS teachers explained after observing the M&M groups during both semesters, “small groups is one of the hardest things to manage in a whole classroom. I think it's invaluable for preservice teachers to know that you need small groups and to figure out how to manage them and what to do with them.”

Connected to the M&M small group structure, one MU student shared, “I love how in small groups [CPMS] students feel more comfortable to speak their minds and to really express what they are thinking.” Another participant reported that in a small group setting, “musees were able to generate ideas based off of what each other were saying…it is also beneficial having only three people in the discussion because it is manageable and gives students more time to voice their opinions.” Still another explained, “I learned a lot from working with my musees. …I helped them get individualized attention that is very hard to get consistently in the [traditional] classroom.” Due to the nature of the partnership and the ways the M&M small groups were designed, learning how to teach in this community-based “third space” helped preservice teachers learn how to interact with and provide instruction and support for smaller groups of students.

After data analysis, the instructor followed up with participants later via email. Based on participants' responses, this community-based field experience appeared to inform participants' current in-service teaching experiences. For example, reflecting on their M&M group experiences and connecting it to their current role as an English and social studies teacher at a small private high school, one mentor explained, “working with two musees at the CPMS definitely helped me prepare to get small groups more engaged.” This mentor also shared how, as a result of their learning how to facilitate small group learning in public places, they have continued to incorporate hands-on, experiential opportunities with small groups.

We were learning about Romanticism in my English 3 class and instead of telling the kids that these authors loved nature (which I did as well), we went out into the woods located right behind the school and practiced writing, taking on the mindsets of the transcendentalists.

So, even when not teaching in a public museum school setting this learning experience still serves to influence some participants as current teachers in traditional school settings.

Alternatively, the M&M small group instructional model also challenged some participants' learning. One participant shared “…I have learned how difficult it is to give each student the attention that I want to give them.” This participant worked with one sixth grade student who had behavioral and academic challenges. They went on to explain, “since I struggle to keep one of my musees engaged and on task, I find that I am not able to give my other three musees as much attention as I think they deserve.”

Additionally, some participants noted that they sometimes struggled to keep their musees “on task” and “focused” when working in small groups on an assigned task. One participant reported, “it is difficult to focus on assignments and learning when you are surrounded by interesting artifacts, people, and excitement.” Another noted that “oftentimes, you could not find a quiet place to sit because of the amount of people in the museum, so you had to adapt so that you could easily capture the attention of your students.” Similarly, in their final reflection connected to their learning as a result of this community-based experience, one participant explained

A difficulty with the [CPMS] is the plethora of artifact/objects that are around. Students can be just as easily engaged or distracted. It takes a structured teacher to master the environment and to ensure that the [CPM] or any public setting is beneficial to learning/teaching.

In these ways, some of the additional logistics associated with teaching and learning in a public place presented challenges for preservice teachers. However, these challenges did not appear to detract from participants' overall perceptions and experiences related to working in this community-based setting.

Overall, participants overwhelmingly reported that they enjoyed working in this community-based setting and appreciated the opportunity to experience teaching and learning in a location outside a typical secondary school setting. The opportunities to build relationships with a small group of sixth-grade students as well as work in a museum setting each week was viewed positively, as evident in mentors' weekly CPMS reflections, feedback during Q/A sessions with the CPMS teachers, and end-of-semester feedback. Although they sometimes struggled to know how to best utilize the public museum setting and found management of some musees challenging, every participant indicated that they would choose to engage in this experience again, if offered the chance. For example, connected to the work in ED 300 and the City Public Museum one particularly enthusiastic participant shared the following in their end-of-semester response (also shared with participating CPMS teachers).

I am extremely thankful for seeing some of the struggle and the process behind planning lessons and planning for each day, getting to learn about classroom management within a classroom that is mobile, learning about cooperative teaching, engaging with a great group of [sixth-grade] students, learning within a practical classroom for real world application, getting to enjoy the actual City Public Museum each week, learning from two experienced teachers in a new role, being inspired by [CPMS principal] and [CPM President and CEO] at the beginning of the semester about creating and inspiring more inquisitive, thoughtful, explorative students, and MUCH, MUCH MORE.

Another participant from a different semester offered the following in their end-of-semester reflection, connected to their experiences teaching and learning in the City Public Museum School.

I thoroughly enjoyed being able to spend time with your students every week and was so glad to have had the opportunity to work with them. Every week I looked forward to Thursdays because of being able to spend time with such great students. Thank you again for allowing us to have such an awesome experience!

Similarly, another shared that they “loved every week!” and another responded, “I was so happy to be able to create new, fulfilling relationships with [CPMS] students and faculty members. This is a very valuable opportunity for teaching students because it provides a greater understanding of the job as a whole.”

The data are clear that this community-based setting afforded many opportunities for preservice teacher learning through regular, on-site experiences within a public museum and public museum school. However, the public, interactive, and active nature of the community-based setting also offered challenges connected to supporting and facilitating adolescents' learning. Although perceived as a challenge for some preservice teacher participants, management of student learning and expectations in small group settings remained an important component of preservice teacher learning. As a result, this community-based setting served as a third space (Zeichner, 2010), where preservice teachers had opportunities to not only learn about and manage small groups but they also did so in a public setting, accessible to and utilized regularly by museum patrons and visitors. This type of experience is not readily available in other, more traditional, K-12 schools and classroom settings.

Discussion

The two research questions guiding this study center on opportunities for preservice teacher learning in a community-based setting and preservice teachers' learning as a result of working with secondary students in such a setting. Based on this study's findings, despite some challenges facilitating adolescent learning in a public museum space, there exists realized opportunities for preservice teacher learning in this community-based setting, including regular access to a large public museum and opportunities to facilitate adolescent learning in small group settings. In this study, the City Public Museum served as a community-based “learningplace” (Conway et al., 2014) and, as a result, preservice teachers had access to a setting beyond a traditional PK-12 school and benefited from the networked expertise provided by CPMS musees, teachers, and the school administrator as well expertise offered in the form of curated museum exhibits and artifacts. As a result, preservice teachers' learning and knowledge were socially constructed through experiences working within a public museum setting (Vygotsky, 1978).

As noted previously, Zeichner's (2010) draws on Bhabha's (1990) “third space” theory to promote more community-based field experiences within teacher preparation programs. As evidenced by findings in this study, the CPMS functioned as a “third space” for teaching and learning, offering participating preservice teachers an opportunity to work in a “learningplace” (Conway et al., 2014) outside a traditional PK-12 setting. As a result of working in this third space, preservice teacher participants were afforded additional opportunities to learn, grow, and further develop their pedagogy and practice.

The results of this first-year pilot partnership indicate that spending time in and learning to teach in a community-based setting, in this case a public museum, provided multiple opportunities for and was beneficial to preservice teacher learning. In addition to contact with adolescent students, teachers, and administrators, the CPMS setting offered preservice teachers access to museum exhibits, spaces, and artifacts. As a result, preservice teachers had opportunities to think about how to incorporate the public museum into their M&M small group time to support adolescents' learning. The M&M small group model also provided opportunities for preservice teachers to engage in approximations of practice (Grossman et al., 2009), such as connecting curriculum with museum exhibits and artifacts as well as small group management and instruction. Engaging in these approximations of practice provided new opportunities for learning to teach (Zeichner et al., 2015) within a community-based “third space” (Zeichner, 2010) setting. Thus, having opportunities to engage in field experiences which provide multiple ways to think about teaching and learning as well as engage in specific approximations of practice (Grossman et al., 2009) affords opportunities to consider how to use community-based settings (i.e., “third spaces”) to support and extend learners' thinking and understanding.

These opportunities also challenge preservice teachers' apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975), expanding their understanding of and experiences with less “traditional” models of education. For example, working regularly with small groups of learners in a community-based setting provided preservice teachers with additional opportunities to understand and experience first hand how teaching and learning is socially and culturally constructed (ten Dam and Blom, 2006). Additionally, because this community-based field experience took place within a public museum setting these small group experiences also afforded opportunities for mentors and their musees to learn through direct immersion in and access to spaces especially designed for and dedicated to exploration and learning.

Based on self-reported preservice teacher data, this community-based school setting was unlike any they had experienced either in their own PK-12 experiences or in any of their current or previous clinical field experiences. Thus, being in a “new” public museum school and having the chance to be a part of the CPMS's first year likely influenced ED 300 students' perceptions of the school, their musees, as well as their own experiences. Regardless of this “new” setting, preservice teachers' learning occurred as a result of their active participation in this community-based setting as well as with their direct engagement with their musees, ED 300 instructor, and partnering CMPS staff. As a result, preservice teachers actively constructed and enacted understandings about teaching and learning through approximations of practice (Grossman et al., 2009) and as participants in the public museum setting.

Although ED 300 students were overwhelmingly positive regarding this community-based field experience and despite ongoing opportunities to engage in various approximations of practice (Grossman et al., 2009) throughout the semester, some preservice teachers expressed apprehension about whether they would want to teach outside a traditional PK-12 school setting. For example, some participants articulated uncertainty about how their specific discipline could be taught well in connection with a public museum as well as worries about managing the complications and logistics of working in this type of setting (e.g., working in a setting where the public is in regular attendance; excursions to locations in the community, including the public library, and local parks; integrating curriculum and co-teaching; planning interdisciplinary, museum-based units and lessons, etc.). Despite these concerns, Zeichner et al. (2015) suggest that teacher education must support preservice teachers' learning and experiences PK-12 schools and communities. Zeichner (2018) suggests that knowledge is socially constructed and contextualized in community-based settings and, as such, these “hybrid spaces” and “third spaces” (2010) may serve to expand preservice teachers' understanding of when, where, and how teaching and learning can and does take place.

In addition to opportunities for preservice teacher learning in a community-based setting, this study also provides insight into a model of clinical field experience centered on small group teaching and learning. In this setting, preservice teachers had opportunities to get to know adolescents over time and work directly with them to develop relationships and support their learning. As a result of working with the same small M&M group of musees each week, ED 300 students practiced targeted literacy and teaching strategies they learned about in ED 300 (i.e., approximations of practice), experimented with various management techniques, and provided both verbal and written feedback on their musees' work. As a result, this community-based field experience differed from traditional PK-12 field experiences which most often center on planning for and enacting whole-group instruction and whole-class classroom management. Thus, offering preservice teachers opportunities to work in “third space” (Zeichner, 2010) community-based settings, especially when using a model of small group facilitation and instruction, provides additional opportunities for preservice teachers to engage in approximations of practice (Grossman et al., 2009). Community-based settings, when functioning as a “third space,” (Zeichner, 2010) may also serve to further challenge and, perhaps, disrupt their apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975) because community-based settings are often less familiar and predictable, require more flexibility and adaptability, and require educators to consider creative, and often not-yet-experienced, ways to integrate these “third spaces” into their pedagogy and practice.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study has implications for preservice teacher education, given the unique community-based setting in which this study took place and the scope and sample size of the study, results are not generalizable. Furthermore, due to MU's proximity to the CPMS, this study may not be easily replicated in other settings. It is also important to note that the first year of this study took place during the first year the CPMS opened its doors. As a result, the “newness” of the school and setting may have more positively (or negatively) predisposed preservice teachers' responses and experiences.

As noted previously, there is variation in group sizes with the number of MU preservice teachers enrolled each semester (i.e., more in the fall than the spring semester). These numbers are dictated by university enrollment and patterns associated with when MU preservice teachers typically student teach (i.e., spring semester). Although these numbers are outside the researchers' control, based on the consistency of findings across both semesters it is likely that the variation in the number of preservice teachers or the number of sixth-grade students in the assigned M&M groups impacted preservice teachers' perceptions of their learning experiences in the course and/or the museum setting.

Although rich with opportunities for preservice teacher learning and university-school partnerships, there are few U.S. public museum schools and even fewer in close proximity to college/university settings. Additionally, this study does not include CPMS secondary student data, which could offer additional insight into ways in which ED 300 students' work with their M&M groups may have contributed to secondary student achievement and growth (beyond the scope of this study). Future research could include assessing possible connections between an embedded preservice community-based field and secondary student assessment data. Moreover, to determine long-term benefits or drawbacks of this type of community-based field experience, a multi-year study could be initiated to explore and ascertain potential and realized opportunities for preservice teacher learning over time. As such, more studies need to be conducted in various community-based placements to determine the efficacy of these settings and the ways it may serve to support and enhance “practice-based” (Ball and Cohen, 1999; Forzani, 2014) teacher education.

Conclusion

Clinical field placement experiences are an important component of teacher education, serving to prepare future teachers for the realities of teaching and learning in PK-12 schools. In addition to orienting preservice teachers to the realities of teaching and learning in school contexts, community-based field experiences also serve to expand preservice teachers' understanding of pedagogical approaches as well as opportunities to engage in approximations of practice (Grossman et al., 2009), particularly those they may not regularly have opportunities to try out in traditional PK-12 classroom settings. Thus, it is critical that preservice teachers have opportunities—when and where possible—to engage in varied clinical field experiences, particularly those which are situated in “third spaces” (Zeichner, 2010) and community-based (Brayko, 2013). Therefore, community-based field experiences, when and where feasible, may serve as an important clinical component for preservice teacher learning. Not without its challenges, working with adolescents in a community-based setting provides preservice teachers with opportunities to reconsider and expand their understanding of PK-12 education models, practice small group student management, foster adolescent engagement, as well as use the community-based setting's resources to support and extend adolescents' thinking and learning.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this study will not be made publicly available because these data are currently not de-identified and, as such, may not be made available to the general public per IRB protocol.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Grand Valley State University and Grand Rapids Public Schools' respective IRB boards' with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Grand Valley State University IRB board as well as Grand Rapids Public Schools' IRB.

Author Contributions

EH was the lead author and researcher for this project, designed the study and collected the data and engaged in all aspects of this study, including analysis and writing. KM joined the team after the data had been collected and functioned as a second researcher on this project and engaged in data analysis, member checking—including work as an external auditor and directly involved in the writing and revision(s) of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnote

1. ^All names are pseudonyms.

References

Balingit, M. (2015). In this Arlington middle school class, teaching math really is an art. The Washington Post. Retrieved from: http://www.ikzadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/Teachers-are-using-theater-and-dance-to-teach-math-%E2%80%94-and-it%E2%80%99s-working-The-Washington-Post.pdf (accessed September 30, 2019).

Ball, D. L., and Cohen, D. K. (1999). “Developing practice, developing practitioners: toward a practice-based theory of professional education,” in Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice, eds G. Sykes and L. Darling-Hammond (San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, 3–32.

Barchuk, Z., Harkins, M. J., and Hill, C. (2015). “Promoting change in teacher education through interdisciplinary collaborative partnerships,” in Change and Progress in Canadian Teacher Education: Research on Recent Innovations in Teacher Preparation in Canada, eds L. Thomas and M. Hirschkorn (Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association for Teacher Education, 190–216.

Bhabha, H. (1990). “The third space: interview with Homi Bhabha,” in Identity: Community, Culture and Difference, ed J. Rutherford (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 207–221.

Blue Ribbon Panel on Clinical Preparation and Partnerships for Improved Student Learning. (2010). Transforming Teacher Education Through Clinical Practice: A National Strategy to Prepare Effective Teachers. Washington, DC: National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education.

Brayko, K. (2013). Community-based placements as contexts for disciplinary learning: a study of literacy teacher education outside of school. J. Teacher Educ. 64, 47–59. doi: 10.1177/0022487112458800

Burn, K., and Mutton, T. (2015). A review of ‘research-informed clinical practice' in initial teacher education. Oxford Rev. Educ. 41, 217–233. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1020104

Coffey, H. (2010). “They taught me”: the benefits of early community-based field experiences in teacher education. Teach Teacher Educ. 26, 335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.014

Conway, P. F., Murphy, R., and Rutherford, V. (2014). “Learningplace” practices and pre-service teacher education in Ireland: knowledge generation, partnerships and pedagogy,” in Workplace Learning in Teacher Education, eds O. McNamara, J. Murray and M. Jones (Springer: Dordrecht), 221–241. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7826-9_13

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures Fordeveloping Grounded Theory 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781452230153

Creswell, J. W., and Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Educ. Pract. 39, 124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Danyluk, P., and Burns, A. (2016). “Building new teacher capacities through an innovative practicum,” in What Should Canada's Teachers Know? Teacher Capacities: Knowledge, Beliefs and Skills, eds M. Hirschkorn and J. Mueller (Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association for Teacher Education), 192–212. Available online at: https://sites.google.com/site/cssecate/fall-working-conference

Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Strengthening clinical preparation: the holy grail of teacher education. Peabody J. Educ. 89, 547–561. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.939009

Emdin, C. (2016). For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of y'all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Feiman-Nemser, S., Tamir, E., and Hammerness, K. (eds.). (2014). Inspiring Teaching: Preparing Teachers to Succeed in Mission Driven Schools. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Forzani, F. M. (2014). Understanding “core practices” and “practice-based” teacher education: learning from the past. J. Teach. Educ. 65, 357–368. doi: 10.1177/0022487114533800

Gravett, S., Petersen, N., and Ramsaroo, S. (2019). A university and school working in partnership to develop professional practice knowledge for teaching. Front. Educ. 3:118. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00118

Greenwood, A., and Kirschbaum, S. (2014). Preparing teachers for place-based instruction at the Tsongas Industrial History Center. J. Museum Educ. 39, 20–27. doi: 10.1080/10598650.2014.11510792

Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., and Williamson, P. (2009). Teaching practice: a cross-professional perspective. Teach College Record 111, 2055–2100. Available online at: https://tedd.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Grossman-et-al-Teaching-Practice-A-Cross-Professional-Perspective-copy.pdf

Grossman, P., and McDonald, M. (2008). Back to the future: directions for research in teaching and teacher education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 45, 184–205. doi: 10.3102/0002831207312906

Gruenewald, D. A., and Smith, G. A. (eds.). (2010). “Creating a movement to ground learning in place,” in Place-Based Education in the Global Age, (New York, NY: Psychology Press; Routledge), 345–358.

Guillen, L., and Zeichner, K. (2018). A university-community partnership in teacher education from the perspectives of community-based teacher educators. J. Teach. Educ. 69, 140–153. doi: 10.1177/0022487117751133

Gupta, P., Adams, J., Kisiel, J., and Dewitt, J. (2010). Examining the complexities of school-museum partnerships. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 5, 685–699. doi: 10.1007/s11422-010-9264-8

Hakkarainen, K., Palonen, T., Paavola, S., and Lehtinen, E. (2004). Communities of Networked Expertise: Professional and Educational Perspectives. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Hallman, H. L., and Rodriguez, T. L. (2015). “Fostering community-based field experiences in teacher education,” in Rethinking Field Experiences in Preservice Teacher Preparation: Meeting New Challenges for Accountability, ed E. R. Hollins (New York, NY: Routledge), 99–116. doi: 10.4324/9781315795065

Hamilton, E.R., Burns, A., Leonard, A., and Taylor, L. (in press). Three museums a construction site: A collaborative self-study of learning from teaching in community-based settings. Study. Teach. Edu.

Hamilton, E. R. (2016). Picture this: multimodal representations of prospective teachers' metaphors about teachers and teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 55, 33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.12.007

Hamilton, E. R., and Van Duinen, D. V. (2019). Purposeful observations: learning to teach in pre-student teaching field placements. Teach. Educ. 53, 367–383. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2018.1425787

Harkins, M. J., and Barchuk, Z. (2015). “Changing landscape in teacher education: the influences of an alternative practicum on pre-service teachers concepts of teaching and learning in a global world,” in Change and Progress in Canadian Teacher Education: Research on Recent Innovations in Teacher Preparation in Canada, eds L. Thomas and M. Hirschkorn (Saskatchewan, MB: Canadian Association of Teacher Educators, 283–314.

Heafner, T., McIntyre, E., and Spooner, M. (2014). The CAEP standards and research on educator preparation programs: linking clinical partnerships with program impact. Peabody J. Educ. 89, 516–532. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.938998

Institute of Museum Library Services. (2004). Mapping New Paths: Museums, Libraries and K-12 Learning. Retrieved from: https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/publications/documents/chartingthelandscape_0.pdf (accessed September 30, 2019).

Institute of Museum Library Services. (2017). National Medal for Museum and Library Service. Retrieved from: https://www.imls.gov/issues/national-initiatives/national-medal-museum-and-library-service/2017-medals (accessed September 30, 2019).

Johnson, R. B. (1997). Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 118, 282–292.

Lasky, D. (2009). Learning from objects: a future for 21st century urban arts education. Perspect. Urban Educ. 6, 72–76. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ869348.pdf

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., and Campanella Bracken, C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 587–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

Lortie, D. C. (1975). Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

McDonald, M., Kazemi, E., Kelley-Petersen, M., Mikolasy, K., Thompson, J., Valencia, S. W., et al. (2014). Practice makes practice: learning to teach in teacher education. Peabody J. Educ. 89, 500–515. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.938997

McDonald, M., Tyson, K., Brayko, K., Bowman, M., Delport, J., and Shimomura, F. (2011). Innovation and impact in teacher education: community-based organizations as field placements for preservice teachers. Teach. College Record. 113, 1668–1700.

McGregor, C., Sanford, K., and Hopper, T. (2010). “ < Alter>ing experiences in the field: next practices,” in Field Experiences in the Context of Reform of Canadian Teacher Education Programs, eds T. Falkenberg and H. Smits (Winnipeg, MB: Faculty of Education of the University of Manitoba, 297–315.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

National Council of Accreditation for Teacher Education. (2010). Transforming Teacher Education Through Clinical Practice: A National Strategy to Prepare Effective Teachers. Washington, DC: Author.

Nichols, S. K. (2014). Museums, universities & pre-service teachers. J. Museum Educ. 39, 3–9. doi: 10.1080/10598650.2014.11510790

Powell, L. S. (2012). 30 Americans: an inspiration for culturally responsive teaching. Art Educ. 65, 33–40. doi: 10.1080/00043125.2012.11519190