Functions and relevance of spatial co-presence: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic for evidence-based workplace and human capital management

- 1Institute of Facility Management, Department of Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur, Switzerland

- 2Institute for Organizational Viability, School of Management and Law, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur, Switzerland

Introduction: This study aims to analyze the role of co-presence against the background of COVID-19 pandemic to derive implications for an interdisciplinary, evidence-based workplace and human capital management. A theoretical framework is outlined that considers a range of topics from task performance to social and organizational contextual factors.

Methods: In a single organization qualitative case study, five focus group interviews including a total of 20 employees of an IT consultancy were conducted to identify the effects of the mandatory remote working regimes imposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic on task and contextual performance.

Results: Findings show that individual performance was assessed to have increased while internal processes remained at similar levels compared to pre-pandemic levels. Organizational culture, social contact, and identity, however, were reported to have considerably deteriorated in the view of the participants.

Discussion: The study shows that for a company that was very experienced with distributed working, the reduction of co-presence had important effects on performance and culture. Findings suggest that co-presence must be carefully managed in the future. This could become a new joint priority for workplace design, workplace management, and human capital management.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis is a disruption for workplace management. It forced many organizations to adapt their ways of working and to switch to remote work and work-from-home for all employees that were not place-bound due to the nature of their work. This change occurred within a very short period of time and also affected organizations that had not previously allowed this form of work and employees that did not have experience with remote working. Therefore, results from previous studies on remote work and work-from-home may not apply to this situation since they are based on studies in organizations where these forms of working were practiced only occasionally or infrequently and have not affected most employees within an organization but only a minority (Carillo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Furthermore, previous studies may suffer a selection bias because remote work and work-from-home in most cases were voluntary (e.g., Lapierre et al., 2016), i.e., existing findings may hold mainly or only for those employees that were interested and engaged in this form of work (Wang et al., 2021).

In light of this profound and unprecedented change, we argue that previous evidence-based design approaches may fall short and fail to address changing circumstances in two ways: (1) they emphasize individual level outcomes and neglect social or team and organization level effects of designing work environments. (2) they are based on the implicit assumption that work mainly happens in corporate offices, i.e., do not research the role and function of work environments for employees who do not spend most of their time there. We conclude that with the massive adoption of remote work and work-from-home (a situation that is sometimes labelled as “new normal”) different or new expectations towards the work environment emerge.

During lockdowns and mandatory work-from-home periods, employees have become accustomed to using digital collaboration infrastructures and adapted their work routines to working remotely.

Recent surveys (e.g., Barrero et al., 2021; Ipsen et al., 2021) indicate that the desire to extend work-from-home is widespread and that employees feel they are more productive in the home office. Many studies (e.g., Beno and Hvorecky, 2021; Galanti et al., 2021) operationalize productivity as perceived individual task performance and neglect other forms of productivity (see Borman and Motowidlo, 1997; Ng and Feldmann, 2008) and productivity at different levels (team, department, organization) (but see Tagliaro and Migliore, 2022). Borman and Motowidlo (1997) distinguish between task performance (employee activities that contribute the organization’s “technical core”) and contextual performance (activities that contribute to organizational effectiveness through shaping of the organizational, social, and psychological context). The contextual aspect of work performance is typically not specified in task descriptions but is considered indispensable for the optimal performance of work groups and organizations (Organ and Paine, 1999).

Looking at the different levels of organizational productivity, which is more than the sum of individual performance (cf. Rousseau, 1985; Kozlowski and Klein, 2000), there are many reasons to emphasize the importance of physical co-presence in the office:

- Collaboration and teamwork are essential to the success of an organization. How well teams function and work together depends on factors such as social and task cohesion (West, 2012; Dey and Ganesh, 2020).

- Opportunities for interaction and physical proximity have a positive impact on team dynamics (Allen, 2007).

- Spatial proximity supports the establishment and maintenance of social relationships and the development of sympathy (Shin et al., 2019).

- Co-presence facilitates spontaneous coordination (Heath & Luff, 1992; Suchman, 1997).

- Co-presence supports knowledge transfer in teams and organizations (Kaschig et al., 2016).

- Culture is transmitted through actions, most of which are not intentionally targeted at transmitting culture in organizations but occur as work activities or routines (Schein, 2004).

- Socialization (and other forms of organizational learning) takes place through listening to and observing the actions of colleagues (Cerasoli et al., 2018).

- Socialization and (co-)experience of culture supports identity and identification with teams and the organization (Ashforth et al., 2008).

Taken together, these functions refer to business (task performance), internal processes and social contact among co-workers, organizational culture, and identity (related to contextual performance). They are based on or affected by physical co-presence as an individual’s sense of being close enough to colleagues to be perceived and to perceive them (Goffman, 1963). According to Goffman (1963), physical co-presence renders individuals accessible, available, and subject to each other.

With the increasing trend towards spatially distributed, virtual work, organizations need to consider how they will manage functions of co-presence and what spatial and organizational means they will use or develop to do so. Some studies suggest that in the future, offices will serve much more than before the pandemic as meeting places where teams and individuals come together in search of interaction (Marzban et al., 2021; Tagliaro and Migliore, 2022). Therefore, the question is how the role of the office is currently changing and will change in the future, especially in its social dimension and with regards to contextual performance (Fayard et al., 2021; Mergener and Trübner, 2022). In this context, it is necessary to examine to what extent the above-mentioned points can be supported by workplace and human capital management practices and where co-presence brings a unique advantage.

Given the disruptive nature of the pandemic that forced organizations and employees to switch to remote work and work-from-home, we conducted a qualitative case study in order to explore employees’ assessments and experiences of co-presence at work and its implications.

2 Methods

2.1 Details of case study

The research was conducted as a single-organization case study. The main goal of the research was to explore the collective views and meanings that lie behind those views of co-presence in the particular context of a medium-sized company. The organization studied is a Swiss software engineering and consultancy company with about 300 employees, 70% of which are working in several locations in Switzerland and 30% abroad. Most employees are software engineers and consultants. Employees are used to distributed work since most of them spend the most significant part of their worktime with clients and at clients’ premises. Most of them are organized in groups by organizational structure and many are members of intra-organizational specialist groups or communities of practice.

2.2 Participants

In order to identify the role and functions of co-presence from the employees’ point of view and against the background of the COVID-19 crisis, five focus group interviews with four employees each were conducted in August 2021. Participants were selected by the human resources department of the company with the aim to compose a representative sample of employees. The 20 participants make up around 10 percent of the company’s workforce working in Switzerland and reflect some of its main demographic characteristics such as function, age, and gender. The group of participants was composed of 14 software experts, four managers, and two administrative staff; all of whom worked remotely during the lockdown and already had experience with remote working prior to the lockdown. 16 participants were male and four female. The number of five focus groups and 20 participants is considered appropriate since previous studies show that up to 90% of themes are discoverable within three to six focus groups (Guest et al., 2017).

2.3 Focus group interviews

The focus group discussion is a technique where a group of employees is brought together to discuss a specific topic. It aims at drawing from personal experiences, perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes of the participants through a moderated interaction (e.g., Nyumba et al., 2018). In this setting, researchers adopt the role of facilitators and aim at moderating a group discussion among participants using a list of questions as guidance for the sessions.

The group interviews lasted 1.5 h on average. The focus group interviews covered six topics related to the role of co-presence. In addition to the business or task performance-related topic of service provision, five topics referring to contextual performance were included:

- service provision, i.e., core business

- internal processes,

- organizational culture,

- leadership,

- social contact, and

- identity.

In each focus group, a qualitative assessment of each of the six topics before and during the COVID-19 pandemic was made in the group discussions. The discussions lasted between 90–120 min. At the end of the sessions, participants were asked to give a summative quantitative statement per topic by sticking stickers on scales drawn on flipcharts.

2.4 Data analysis

During the focus group interviews both researchers took notes. Notes were integrated into a protocol after each session and the protocols served as data for the subsequent qualitative analysis. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used to analyze the interview data. Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 79) describe thematic analysis as “a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data.” The authors read through the interview transcripts multiple times to identify underlying themes and through multiple iterative, parallel counter-readings formed a common understanding to assure interrater reliability. This abductive process resulted in a thematic category system with core examples along the six core perspectives.

3 Results

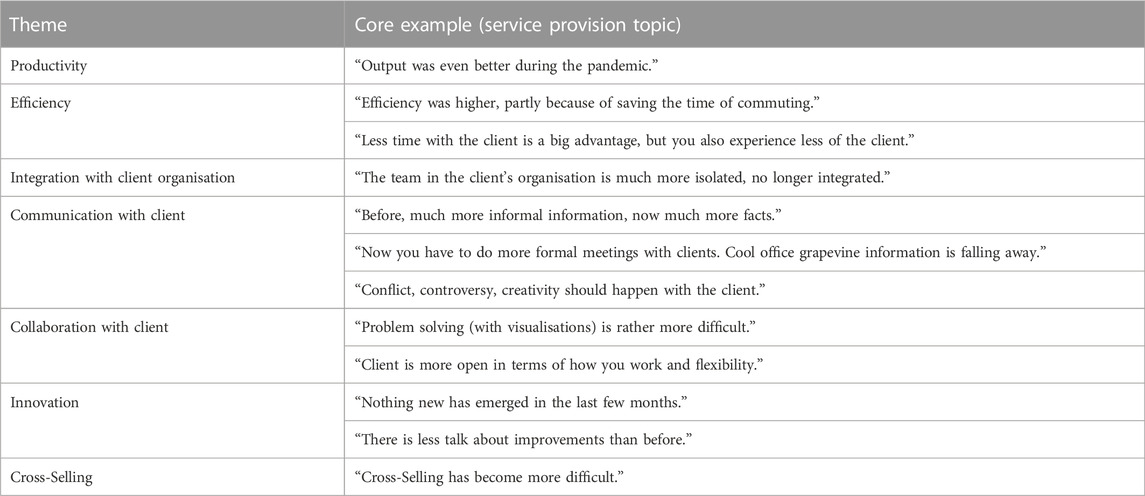

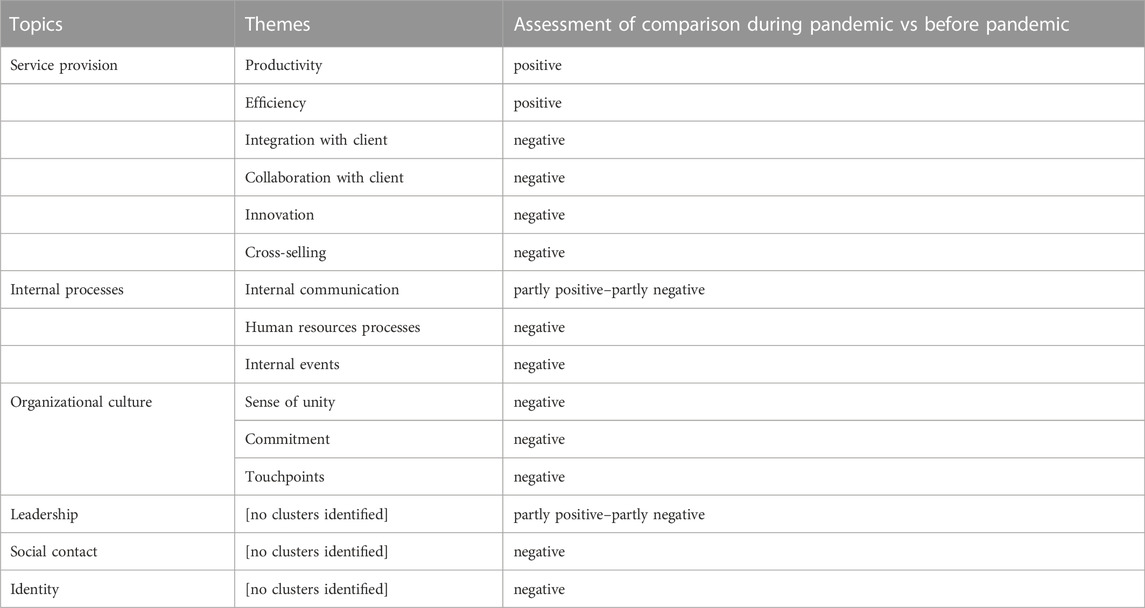

The resulting category system consisted of six topics and 12 themes. Table 1 shows the topics and themes identified for the service provision, internal processes, and organizational culture topics. The assessment of the comparison of the situation during the pandemic with the situation before the pandemic was inferred by the researchers based on the contents of the focus groups that are presented in the following sections.

TABLE 1. Overview of topics, themes, and assessment of difference during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic.

3.1 Service provision

In terms of service provision, the results of the focus group interviews revealed seven themes affected by the coronavirus pandemic and with a distinct role of co-presence (Table 2). Since service provision refers to the core business of the company, it was the most intensely discussed of all topics. The first theme that emerged from the data analysis was productivity. This theme refers to the output of work and tended to be discussed positively. However, some participants stated some concerns that the quality of the output may have suffered from providing services in a remote mode during lockdowns and mandatory work-from-home periods. In terms of efficiency, the second theme of the service provision topic, participants agreed that saving time commuting and travelling to clients positively contributed to efficiency. Working remotely also increased flexibility in service provision since employees of the company could compose teams more flexibly since they did not have to travel to clients’ premises. Some concerns regarding efficiency were mentioned for communication: due to the lack of informal communication possibilities with clients, communication became more formal and “all information exchange needs to be scheduled” as one participant mentioned. Similarly, integration with the client organization–the third theme - was considered more difficult. Working from a distance made it difficult to identify key people in the client organization and to deliberately build up a network. Participants reported major changes in the communication with clients: ad hoc and informal information exchange was massively reduced and had to be replaced through more formal, scheduled meetings. When communication occurred, the quality was experienced as different because non-verbal and visual feedback was reduced. Participants reported that this impaired mainly non-routine communication. Status updates and similar routine communication was considered to work well in online settings. However, conversations with difficult content, such as potentially conflictual strategic topics, conflict, criticism, controversy, or creativity should take place in co-located settings. Concerning the collaboration with the clients, participants mentioned that generally, team spirit was reduced or missing and that “there was less energy in the processes.” Work tasks that are dependent on visualizations were considered more difficult. Consequently, such tasks were less developed jointly in the team. Innovation was considered to be impaired through the forced remote settings. Some participants considered co-presence as a prerequisite for innovation. A participant mentioned, referring to processes, practices, and routines: “Nothing new has emerged in the last few months; we may [only] have become more productive. One tries to find one’s way in the existing.” Finally, cross-selling was reported to have become more difficult because employees from the consultancy did not overhear potential client needs.

3.2 Internal processes

The second topic of the study is internal processes. Three themes emerged from the analysis: internal communication, human resources processes, and internal events.

Participants experienced internal communication and internal meetings as better than before the pandemic because the meetings were more focused and shorter in the online mode. This mainly applied to formal and routine meetings within the teams. For informal, sensitive, or personal content, however, participants missed the co-located meetings. Some had the impression, that despite an “excess of videoconferencing, contact is rather sparse.” Furthermore, participants mentioned that colleagues and managers were generally accessible easier than before the pandemic. Generally, signaling availability in Microsoft Teams and similar platforms was considered useful, particularly to reduce interruptions and distractions. On the other hand, communications outside the team boundaries have broken down. One participant mentioned: “Spontaneous discussions across team boundaries are missing but are often the best conversations.” Some participants referred to learning activities that play an important role in the company. They noticed that technical and highly structured learning did not suffer from the shift to the online mode. However, interactive learning and training sessions suffered from the change.

Also referring to internal communication, participants stated that processes could not be abbreviated via less formal channels anymore. As an example, internal IT support was mentioned. Short routes to IT support were not possible anymore and requests had to follow the formal process via tickets which was considered much more time-consuming.

The second theme pertaining to the internal processes topic is human resources processes. Here, the onboarding of new employees was reported as the major issue. Onboarding of new colleagues was considered to be very difficult because emotional bonds could not be established as quickly and naturally as before the pandemic.

Internal events are the third theme in the topic. Participants mentioned internal academies, communities of practice, and workshops. They agreed that the formal and technical quality of these events remained good but co-learning and community-related work became more difficult because of the limited possibilities for social interaction. Playful and experimental sessions have fallen away. One workshop leader mentioned that “trainings, internal academies and workshops are a pain because you do not feel people.”

3.3 Organizational culture

Thematic analysis revealed three themes in the third topic researched, organizational culture. The themes are: sense of unity, commitment, and touchpoints. Regarding the sense of unity, participants bemoaned the perceived reduction of the collaboration culture that they identified as a core characteristic of the organizational culture. Socializing was identified as another key characteristic of the company culture. Participants mentioned that company-wide online sessions (such as virtual town hall sessions or focus days) were satisfactory content-wise but lacked the social element, e.g., with talks at the coffee machine. Furthermore, the organization became more anonymous, as one participant mentioned: “You no longer know all your colleagues.” Some participants stated that it had become difficult to “feel” the company or that they tended to lose the attachment to the organization. One participant summarized: “There is no longer any difference between [name of the company] and other companies. [name of the company] exists only on paper.”

The second theme of the organizational culture topic is commitment. The changing role of commitment is substantiated by statements about the short-term rescheduling of priorities (“a meeting has come up…”) and participation in online meetings: “At on-site events, you can’t just run away, cancellations at short notice are too easy online, something has been lost in terms of culture.”

Touchpoints are the third theme of the organizational culture topic. The participants unanimously regretted that organizational events had been cancelled and they were missing company specific rituals that had shaped organizational culture. Since the employees spend lots of time with different clients, socializing events played an important role that got lost during the pandemic and left participants with the question of what the actual current company culture looked like. Some participants missed feedback loops when events took place virtually. Furthermore, they stated that the socialization of new colleagues used to take place via work shadowing, and that it was difficult to replace this. Socialization took much more time, and participants concluded that the integration of new members of the organization generally required co-presence.

3.4 Leadership

The fourth topic, leadership, was unanimously perceived as unchanged or barely changed by both, managers and employees. Participants referred to their experience with distributed working. Due to the nature of the work in the organization, formal exchange between managers and employees happened in scheduled meetings and often online or by telephone.

3.5 Social contact

The fifth topic of the study is social contact. Participants mentioned various aspects. They said that human relations were impaired by the pandemic. One participant mentioned that “Seeing and being seen… being perceived as a human being is somewhat lost.” Before the pandemic, many things were experienced casually (contact, conversation, etc.), during the pandemic, one had to actively seek exchange. Participants also explained that contact with colleagues was easier due to the use of ICT tools, but the personal contact was missing. They were missing informal discussions and felt that the content of conversations was limited to work. Furthermore, the exchange of ideas beyond the “normal working group” was missed by some. For a team to function, participants felt that knowing each other was a pre-requisite. They observed that it was difficult for new employees to establish their network within the company. Teambuilding was assessed as easier in physical co-presence both, with client teams and within the company. One participant mentioned that as a flip side, efficiency in the office during the pandemic was reduced because “everyone always wants to socialize in the office now.”

3.6 Identity

Finally, the sixth topic was identity. Participants agreed that identification with the company was easier and better before the pandemic. Some were even worried about the connections of employees with the company and had the impression that the employees could “no longer feel the company.” They questioned whether any identity-forming activities or events remained during the pandemic and mentioned that formerly, the company’s culture and employees’ identification was strongly shaped by events such as training, social, and festive gatherings. With increasing duration of the pandemic, it was “not so clear anymore where employees felt at home.”

3.7 Summative assessments

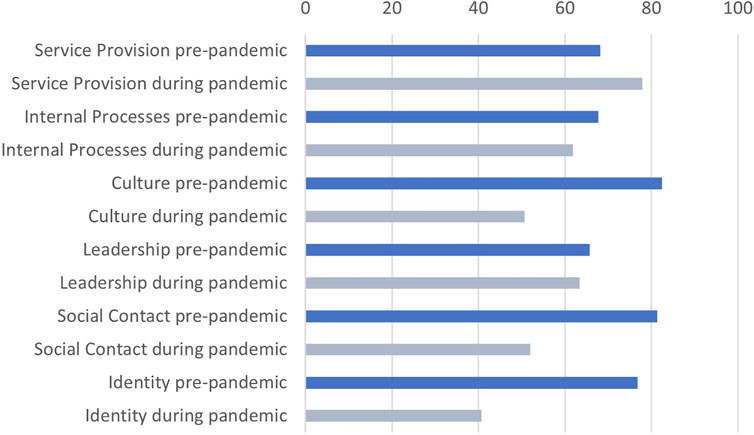

The participants of the focus group interviews summarized their “before” and “during the pandemic” assessment of the topics discussed by placing stickers on scales drawn on flipcharts. These quantitative statements are displayed in Figure 1 transformed on a scale from 0 (low) to100 (high) by measuring the position of the stickers on the flipcharts.

FIGURE 1. Mean values of focus group participants’ summative quantitative assessments of the topics (n = 17; 0 = low/dissatisfactory, 100 = high/satisfactory).

The quantitative assessments reflect the qualitative information and show that service provision or productivity, respectively, was judged to be somewhat higher during the pandemic while internal processes and leadership were assessed slightly lower during the pandemic than before. Organizational culture, social contact, and identity on the other hand, seems to have been significantly negatively affected during pandemic (see Figure 1).

4 Discussion

Results from the five focus group interviews revealed a multitude of themes regarding the role and function of co-presence for service provision, internal processes, leadership, organizational culture, social contact, and identity. Participants largely agreed about the consequences of the pandemic and the new forms of working it induced for the leadership, social contact, and identity perspectives. While leadership was experienced as largely unaffected by the pandemic, social contact and identity were assessed as significantly impaired.

Participants’ experiences and assessment of the themes within the service provision, internal processes, and organizational culture perspectives were ambivalent:

Productivity and efficiency were assessed as more positive during the lockdowns and mandatory work-from-home periods than before the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast to this, integration, communication, and collaboration with the clients as well as innovation and cross-selling, were assessed negatively. Thus, there seem to be some tensions between individual efficiency (saving time on travelling and commuting, reduction of interruptions and distractions) on one hand and team and company performance, on the other hand. Hence, individual efficiency gains may come at the price of team effectiveness. As such, the effects of co-presence on contextual performance needs to be further researched.

The impact of reduced co-presence and increased online interaction on internal processes due to the COVID-19 crisis was assessed as ambiguous: participants stated that formal, technical, and structured processes improved or remained unaffected. Furthermore, the accessibility of colleagues and supervisors became easier, and participants could manage interruptions and distractions better. On the other hand, participants reported that informal meetings, conversations with personal or sensitive content, communications across team boundaries, interactive learning sessions, co-learning, community-related work, and playful or experimental sessions suffered from a lack of co-presence or fell completely away. Thus, the “social glue”, i.e., informal organization, processes, and interactions that create attachment of employees to their colleagues, was negatively affected while formal processes remained efficient and effective or even improved. A reduction of social reflexivity in teams may reduce task effectiveness, team member wellbeing, and innovation in the medium term (see West, 2012).

The quantitative summative statements indicate that culture was most affected by the change to working from home. Participants mentioned that the collaboration culture, previously a core element of organizational culture, suffered. This perception was correlated with a reduction of (informal) social contacts, particularly related to organizational events, and more anonymity in the organization. One indicator that was mentioned for these changes was the reduced commitment to scheduled online events. Furthermore, socialization, i.e., the transmission of culture to new organizational members, was considered as more difficult and time-consuming than before.

Taken together, these results show that formal task-oriented individual and group processes are perceived as working well for the participants. However, informal processes and social connections suffered from the transition to work from home. These findings are in line with recent studies (Marzban et al., 2021; Whillans et al., 2021; Tagliaro and Migliore, 2022). While Marzban and colleagues (2021) found some considerable differences in the perceptions of employees and organizations (senior managers), most topics of their study are also reflected in the present results. The qualitative approach presented in this study, however, revealed more clearly how the transition to work from home with regards to a social dimension were perceived.

It is important to note that the software engineers, architects, and consultants that participated in this study were used to remote work even before the pandemic. In fact, before the pandemic, most employees of the company studied spent most of their working time with clients on clients’ premises. Thus, the lockdowns and mandatory work from home phases mainly affected the time they spent with their colleagues and supervisors within the employer organization. This highlights the importance of physical co-presence for a workforce of predominantly distributed employees.

5 Limitations

It is in the nature of single case studies that results may not be generalizable due to the specific and rather small sample. Furthermore, data collection was limited to focus groups, and we did not have access to organizational performance indicators to complement the statements of the participants. However, the procedure resulted in a rich, context-specific, and holistic account of the situation, i.e., the effects of the pandemic and lockdowns from an employee’s point of view. As such it may inform and inspire further, rigorous quantitative and qualitative studies with larger and more diverse samples.

6 Conclusion

6.1 Managing co-presence as interdisciplinary service

The results show that for employees of the company time spent together was precious and important in terms of social connections, onboarding and socialization of new colleagues, experiencing and transmitting organizational culture, identity, and formal and informal task related processes. For the organization to maintain or re-establish these functions, spaces for socializing, meeting, and chance encounters are needed. In addition to specific functional qualities, these spaces must provide services and experience (cf. Petrulaitiene et al., 2018). One possible development for future workplace management is therefore a stronger interweaving of spatial infrastructure and services: In order for employees to use the social functions as much as possible when they are in the office, it must be ensured that the right colleagues can be contacted (physically, virtually, hybrid). To ensure this, community management (Merkel, 2015) and workplace experience services can be used. Such services are common today in co-working centers and should be reviewed in terms of need, scope, quality, and effort for transfer to work organizations. Based on this, such a system consisting of space, technology, employees, and services must be redeveloped for an even more mobile world of work. Since some areas of the social functions affect the area of HR management, new forms of cooperation between the support areas of workplace/facility management and HR management must also be developed. For example, specific communication skills, reflection of social interaction, and selection of corresponding tools might be a future key skill of leaders and high performing teams. Such an individual or team-based capability must deliberately be fostered and supported by HR practices and the growing body of AI-based HR Tech (e.g., Bersin, 2021; Mitchell and Brewer, 2021). For example, a radical intentional use of time for leaders and teams might be supported through an integration of workplace and employee experience management (Windlinger and Lange, 2021). Moreover, the emerging function of people analytics might serve as a hub for a systematic evidence-based workplace design. The basic idea of people analytics is to support data-based management decisions and to design people-oriented HR practices and services through iterative, incremental learning cycles (Ferrar and Green, 2022). The design of a human-centered work environment is key not only to workplace and employee experience but also to social learning in the flow of work (e.g., Lizier, 2022).

6.2 Team-based workplace strategies

More to the core of workplace management, workplace strategies should emphasize team-oriented spaces more strongly. The activity-based working (ABW) office concept has evolved as the current “standard office concept” in recent years. These concepts work well for individual work but are still suboptimal for teams. For the post-covid world of work, ABW concepts need to be further developed in such a way that they offer an infrastructure (space, technology, services) for both individual work and teamwork that jointly supports task and community related activities and eventually both, task and contextual performance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

Both authors conceived, designed, and conducted the research. First author wrote the inital paper, MG provided feedback and input to several versions of the draft. LW finalized the paper and submission.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, T. J. (2007). Architecture and communication among product development engineers. Calif. Manag. Rev. 49 (2), 23–41. doi:10.2307/41166381

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., and Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 34 (3), 325–374. doi:10.1177/0149206308316059

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., and Davis, S. J. (2021). Why working from home will stick. Available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28731/w28731.pdf.

Beno, M., and Hvorecky, J. (2021). Data on an Austrian company's productivity in the pre-covid-19 era, during the lockdown and after its easing: To work remotely or not? Front. Commun. 6. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.641199

Borman, W. C., and Motowidlo, S. J. (1997). Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 10 (2), 99–109. doi:10.1207/s15327043hup1002_3

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carillo, K., Cachat-Rosset, G., Marsan, J., Saba, T., and Klarsfeld, A. (2021). Adjusting to epidemic-induced telework: Empirical insights from teleworkers in France. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 30 (1), 69–88. doi:10.1080/0960085x.2020.1829512

Cerasoli, C. P., Alliger, G. M., Donsbach, J. S., Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I., and Orvis, K. A. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of informal learning behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 33 (2), 203–230. doi:10.1007/s10869-017-9492-y

Dey, C., and Ganesh, M. P. (2020). Impact of team design and technical factors on team cohesion. Team Perform. Manag. 26 (7-8), 357–374. doi:10.1108/Tpm-03-2020-0022

Fayard, A. L., Weeks, J., and Khan, M. (2021). Designing the hybrid office. Harv. Bus. Rev. 99 (2), 1–11.

Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., and Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63 (7), e426–e432. doi:10.1097/jom.0000000000002236

Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in public places - notes on the social organization of gatherings. New York: Free Press.

Guest, G., Namey, E., and McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field methods 29 (1), 3–22. doi:10.1177/1525822x16639015

Heath, C., and Luff, P. (1992). Crisis management and multimedia technology in London underground line control rooms. J. Comput. Supported Coop. Work 1 (1), 24–48.

Ipsen, C., van Veldhoven, M., Kirchner, K., and Hansen, J. P. (2021). Six key advantages and disadvantages of working from home in Europe during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (4), 1826. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041826

Kaschig, A., Maier, R., and Sandow, A. (2016). The effects of collecting and connecting activities on knowledge creation in organizations. J. Strategic Inf. Syst. 25 (4), 243–258. doi:10.1016/j.jsis.2016.08.002

Kozlowski, S. W. J., and Klein, K. J. (2000). “A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes,” in Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions. Editors K. J. Klein, and S. W. J. Kozlowski (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass), 3–90.

Lapierre, L. M., van Steenbergen, E. F., Peeters, M. C. W., and Kluwer, E. S. (2016). Juggling work and family responsibilities when involuntarily working more from home: A multiwave study of financial sales professionals. J. Organ. Behav. 37 (6), 804–822. doi:10.1002/job.2075

Lizier, A. L. (2022). Re-considering the nature of work in complex adaptive organisations – fluid work as a driver of learning through work. J. Workplace Learn. 34 (2), 150–161. doi:10.1108/JWL-09-2020-0152

Marzban, S., Durakovic, I., Candido, C., and Mackey, M. (2021). Learning to work from home: Experience of Australian workers and organizational representatives during the first covid-19 lockdowns. J. Corp. Real Estate 23 (3), 203–222. doi:10.1108/Jcre-10-2020-0049

Mergener, A., and Trübner, M. (2022). Social relations and employees' rejection of working from home: A social exchange perspective. New Technology Work and Employment 37 (3), 469–487. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12247

Mitchell, A., and Brewer, P. E. (2021). Leading hybrid teams: Strategies for realizing the best of both worlds. Organ. Dyn. 51, 100866. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2021.100866

Ng, T. W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 93 (2), 392–423. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.392

Nyumba, O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., and Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9 (1), 20–32. doi:10.1111/2041-210x.12860

Organ, D. W., and Paine, J. B. (1999). “A new kind of performance for industrial and organizational psychology: Recent contributions to the study of organizational citizenship behavior,” in International review of industrial and organizational psychology. Editors C. L. Cooper, and I. T. Robertson (New York: John Wiley and Sons), 14, 337–368.

Petrulaitiene, V., Korba, P., Nenonen, S., Jylha, T., and Junnila, S. (2018). From walls to experience - servitization of workplaces. Facilities 36 (9-10), 525–544. doi:10.1108/F-07-2017-0072

Rousseau, D. M. (1985). Issues of level in organizational research: Multi-level and cross-level perspectives. Res. Organ. Behav. 7, 1–37.

Shin, J. E., Suh, E. M., Li, N. P., Eo, K., Chong, S. C., and Tsai, M. H. (2019). Darling, get closer to me: Spatial proximity amplifies interpersonal liking. Personality Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45 (2), 300–309. doi:10.1177/0146167218784903

Suchman, L. A. (1997). “Centers of coordination: A case and some themes,” in Discourse, tools, and reasoning. Essays on situated cognition. Editors L. B. Resnick, R. Säljö, C. Pontecorvo, and B. Burge (Berlin: Springer), 41–62.

Tagliaro, C., and Migliore, A. (2022). Covid-working": What to keep and what to leave? Evidence from an Italian company. J. Corp. Real Estate 24 (2), 76–92. doi:10.1108/Jcre-10-2020-0053

Wang, B., Liu, Y. K., Qian, J., and Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Appl. Psychol. - Int. Rev. 70 (1), 16–59. doi:10.1111/apps.12290

West, M. A. (2012). Effective teamwork: Practical lessons from organizational research. 3rd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Whillans, A., Perlow, L., and Turek, A. (2021). Experimenting during the shift to virtual team work: Learnings from how teams adapted their activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inf. Organ. 31 (1), 100343. doi:10.1016/j.infoandorg.2021.100343

Keywords: workplace management, co-presence, qualitative case study, productivity, organizational culture, identity, social contact

Citation: Windlinger L and Gerber M (2023) Functions and relevance of spatial co-presence: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic for evidence-based workplace and human capital management. Front. Built Environ. 9:1035154. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1035154

Received: 02 September 2022; Accepted: 11 January 2023;

Published: 24 January 2023.

Edited by:

Shauna Mallory-Hill, University of Manitoba, CanadaReviewed by:

Seyda Adiguzel Istil, Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, TürkiyeGrit Ngowtanasuwan, Mahasarakham University, Thailand

Copyright © 2023 Windlinger and Gerber. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lukas Windlinger, Lukas.windlinger@zhaw.ch

Lukas Windlinger

Lukas Windlinger Marius Gerber

Marius Gerber