Exploring monkeypox virus proteins and rapid detection techniques

- Department of Biology, School of Sciences and Humanities, Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan

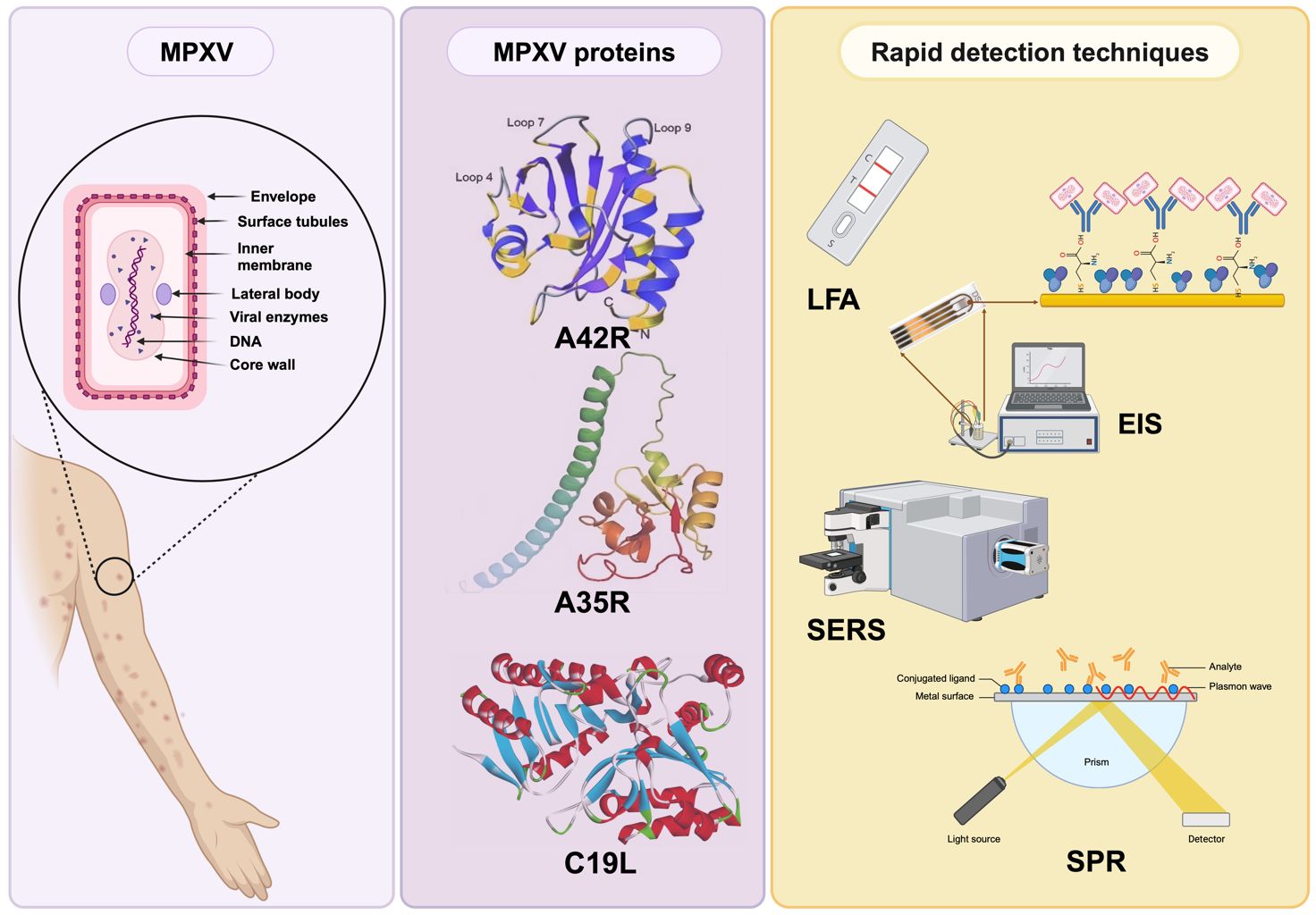

Monkeypox (mpox) is an infectious disease caused by the mpox virus and can potentially lead to fatal outcomes. It resembles infections caused by viruses from other families, challenging identification. The pathogenesis, transmission, and clinical manifestations of mpox and other Orthopoxvirus species are similar due to their closely related genetic material. This review provides a comprehensive discussion of the roles of various proteins, including extracellular enveloped virus (EEV), intracellular mature virus (IMV), and profilin-like proteins of mpox. It also highlights recent diagnostic techniques based on these proteins to detect this infection rapidly.

Introduction

Mpox (formerly referred to as monkeypox) is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV) that belongs to the Orthopoxvirus (OPXV) genus of the Poxviridae family (Gubser et al., 2004). It results in symptoms that start with fever, headache, and back pain and are followed by systematic rash and blisters (Magnus et al., 1959; Cho and Wenner, 1973). These symptoms are similar to infections caused by other members of the same genus, such as the variola virus (VARV) and vaccinia virus (VACV). In addition, mpox resembles infections caused by viruses from other families. For example, chickenpox, caused by the varicella-zoster virus, a member of the Herpesvirus family, exhibits symptoms similar to MPXV infections (Chauhan et al., 2023). Since the clinical presentation of these diseases in humans shares similarities, diagnosing mpox relying on the observable symptoms is challenging.

Mpox has the potential to lead to a fatal outcome, resulting in a mortality rate ranging from 1% to 10%, depending on the specific clade of the MPXV strain causing the infection and the level of access to advanced healthcare services (Adalja and Inglesby, 2022). At present, no specific treatment is available for the MPXV infection. However, supportive care plays a vital role in managing the symptoms, including using medications to alleviate fever and pain. The smallpox vaccine can provide partial protection (85%) against monkeypox, but its effectiveness is not guaranteed in all cases (Fine et al., 1988). Hughes et al. (2014) discovered a specific epitope of the MPXV through a monoclonal antibody designed for the heparan binding site on the MPXV envelope protein. Hence, this finding paved the way for more specific serologic assays for mpox detection (Al-Musa et al., 2022).

Current MPXV detection methods include viral isolation, electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and PCR (polymerase chain reaction)/rtPCR (reverse transcription PCR) (Li et al., 2006; McCollum and Damon, 2014; Karagoz et al., 2023). However, these techniques require advanced technical skills, state-of-the-art laboratories, and specialized training and fail to meet the demand for timely and rapid identification of MPXV infection (McCollum and Damon, 2014; Halvaei et al., 2023). Consequently, there is a need for reliable detection approaches to accurately identify MPXV-infected individuals and control the spread of the disease. In this paper, our focus centers on the pathogenesis and biological traits of mpox while also detailing the characterization of MPXV envelope proteins, including A29L, H3L, E8L, M1R, L1R, C19L, A35R, B6R, and the profilin-like mpox A42R protein. These proteins are highlighted as potential targets for a range of detection methods. Additionally, we provide an overview of recent advancements in rapid detection techniques for mpox.

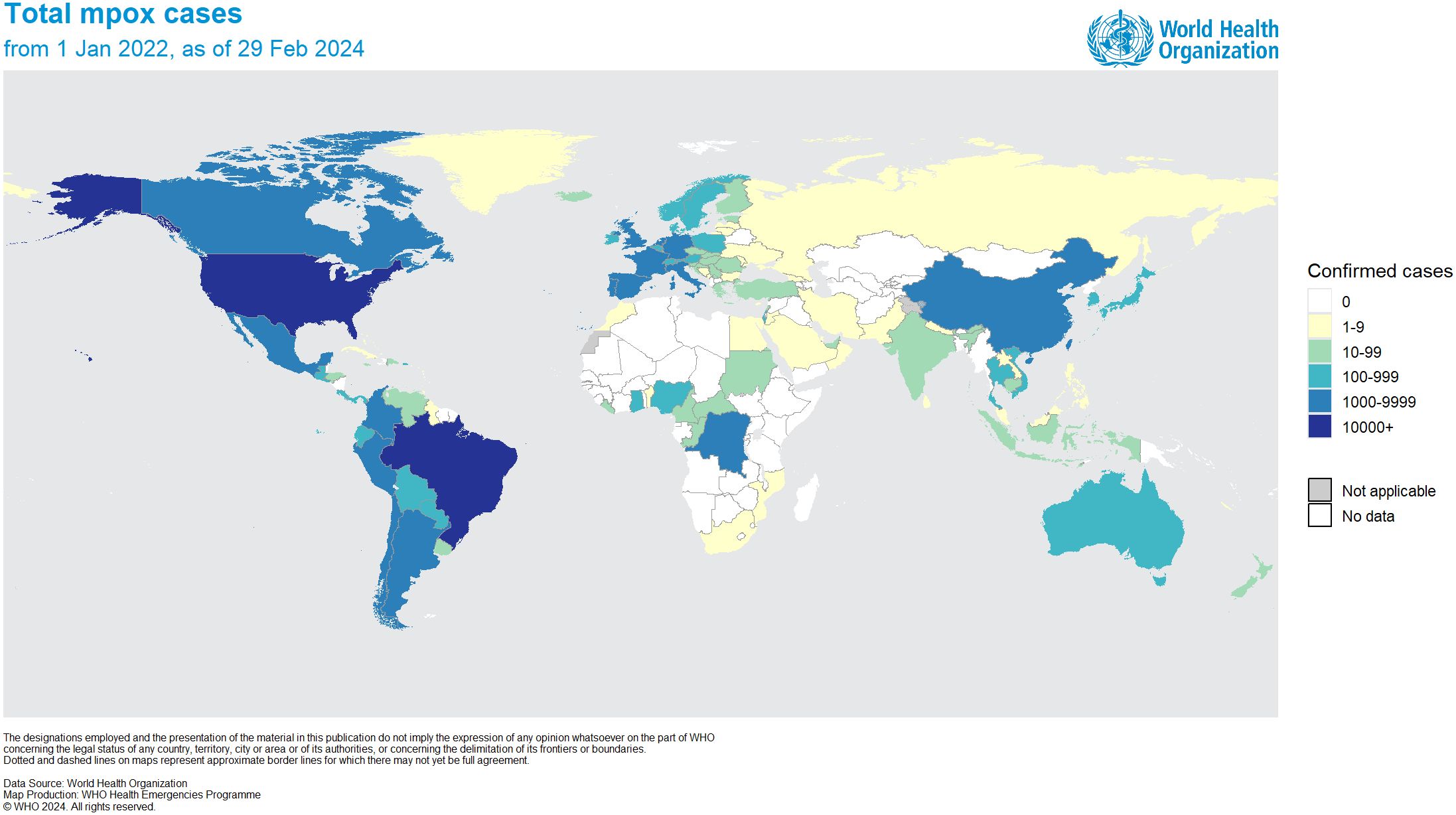

Epidemiology

The first case of mpox was found in a nine-month-old infant in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Since 1970, there has been an increase in mpox outbreaks, mainly occurring on the African continent (Breman et al., 1980; Alakunle et al., 2020). Specifically, between 1970 and 1995, 388 out of 418 recorded cases of mpox were documented in Zaire (currently known as DRC) (Shchelkunov et al., 2001). Since May 2022, mpox cases have been reported in Europe and North America. As of February 29, 2024, the ongoing mpox outbreak has resulted in over 94,707 laboratory-confirmed cases, including 181 deaths. Approximately 715 cases have been reported worldwide monthly (World Health Organization, 2024). These cases are spread across 117 countries, of which only seven had previously reported cases of MPXV before 2022 (Figure 1). Due to the rising global cases, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated MPXV as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on July 23, 2022 (World Health Organization, 2022). According to the latest data received, the number of laboratory-confirmed cases reported monthly has increased by 1.6% compared to January, with the majority of cases originating from the USA (31.9%) and Europe (31.2%) (World Health Organization, 2024).

Figure 1 Distribution of confirmed MPXV cases worldwide as of February 29, 2024 (adapted with permission from World Health Organization, 2024).

Biological features

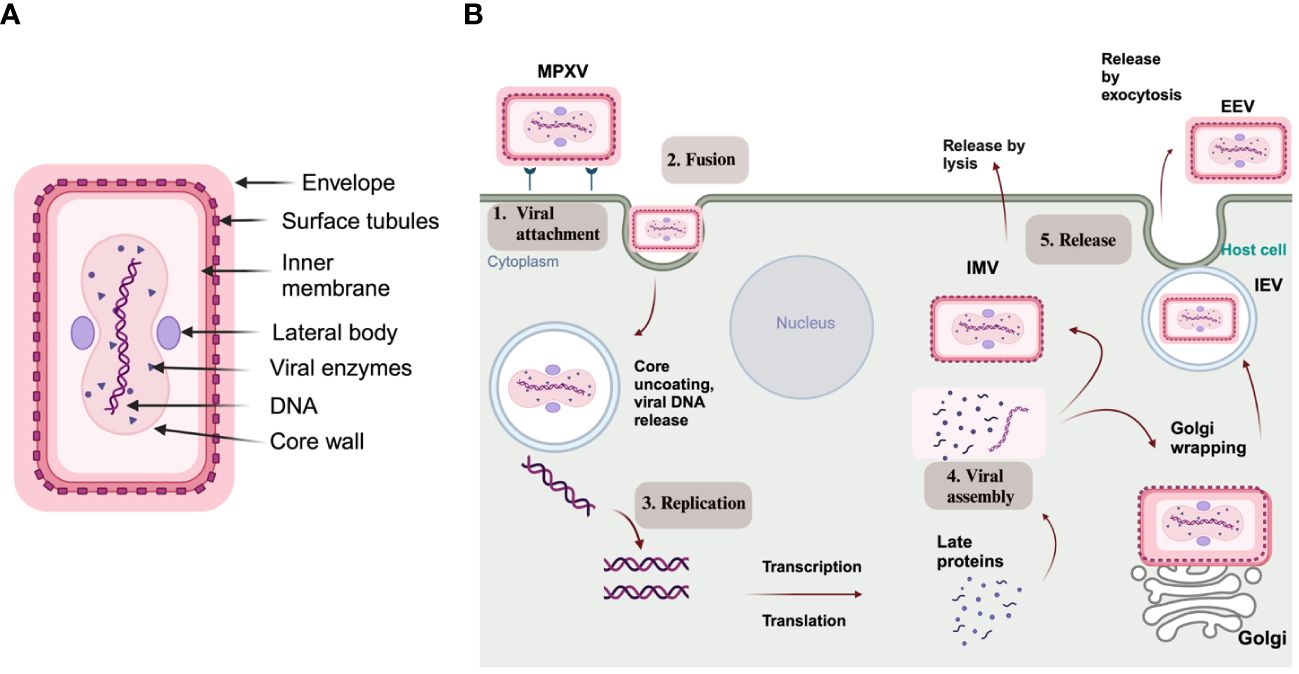

MPXV is characterized as an enveloped double-stranded (ds) DNA virus, and its genome size is approximately 197 kb, encoding nearly 190 proteins (Shchelkunov et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2022). The virus structure includes a lipoprotein envelope, a viral core, and two lateral bodies, as depicted in Figure 2A (Witt et al., 2023). The genome comprises two variable regions on both the right and left sides and a conserved large central genomic region occupied with core genes. The variable regions are composed of genes responsible for encoding proteins related to virulence and determining host range, where significant differences between MPXV and VARV occur. Meanwhile, the core region encodes structural proteins and essential enzymes, which share 96.3% similarity with the core region of the VACV (Shchelkunov et al., 2001).

Figure 2 (A) Structure of MPXV; (B) Schematic representation of an MPXV replication cycle, including (1) viral attachment, (2) fusion, (3) replication, (4) viral assembly, and (5) release from the host cell (created via BioRender.com).

The ds nature of MPXV’s genetic material has advantages and disadvantages from a detection perspective. Unlike positive-sense single-stranded (ss) RNA viruses, like SARS-CoV-2, which can directly initiate the synthesis of viral proteins upon entering the host cell, DNA viruses need to first convert their DNA to RNA before expressing viral proteins (Durmuş and Ülgen, 2017). Consequently, MPXV can stay in the body longer before exhibiting noticeable symptoms in infected individuals (Bhalla and Payam, 2023). Hence, it can lead to the unnoticed spread of infection within the community. This phenomenon most likely played a role in the undetected spread of MPXV in various geographical areas, challenging researchers to develop new approaches, including diagnostic tools and biosensors. However, the advantage of DNA viruses is that they are comparatively more straightforward and more accurate in detecting using PCR tests than RNA viruses. DNA virus detection does not require reverse transcription before PCR (Bhalla and Payam, 2023).

Poxviruses, including MPXV, are recognized for their distinctive structure, which is typically brick-shaped or oval, with a size ranging from 200 to 250 nm (Cho and Wenner, 1973). Based on the genome sequence, MPXV is phylogenetically classified into two clades: clade 1, which is found in central Africa and the Congo basin, and clade 2, which is from West Africa. However, the phylogenomic analysis, including those from the 2022 outbreaks, revealed that these outbreaks were caused by a recently evolved clade called “hMPXV-1A” lineage B.1 (Luna et al., 2022).

Pathogenesis

The virus can be transmitted from animals to humans or from humans to humans via direct and close contact, spreading through blood, body fluids, and dermal or mucosal injuries. During human-to-human transmission, MPXV enters through the upper respiratory tract, including the oropharynx and nasopharynx, or via intradermal routes (Li et al., 2022b). The clinical features of MPXV highly resemble smallpox disease, which also presents 10-14 days of incubation followed by two days of skin rash formation. Like smallpox, the development of rash includes phases such as macular, popular, vesicular, and pustular (Weaver and Isaacs, 2008; Hughes et al., 2014). Hence, the differentiation of these diseases by clinical presentation is quite challenging.

As with other poxviruses, MPXV replication occurs in the cytoplasm and undergoes through virally encoded RNA polymerase. As depicted in Figure 2B, MPXV pathogenesis includes viral particle attachment, fusion, viral genome replication, virion assembly, and release from the infected host cell. During these steps, two types of infectious forms of MPXV are produced: extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) and intracellular mature virus (IMV). The EEV is released through exocytosis and comprises a lipid membrane wrapped around the intracellular IMV particle originating from the Golgi apparatus or endosomes. On the other hand, the IMV is released during cell lysis and has a stable lipoprotein envelope, making it suitable for transmission between animals (Gong et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2022).

The entry fusion step involves a complex interaction with multiple receptors, namely heparan sulfate, glycosaminoglycans, and chondroitin (Montanuy et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2014; Khanna et al., 2017). It has also been proposed that genes responsible for viral replication enzymes and structural proteins are highly homologous among OPXVs (Shi et al., 2022). Senkevich et al. (2005) proposed that the fusion entry mechanism is conserved among the poxvirus family, which suggests that this primary mechanism developed early in their evolution and remains unchanged. Hence, MPXV can possess standard features in its entry-fusion step with other members, especially VACV.

MPXV proteins

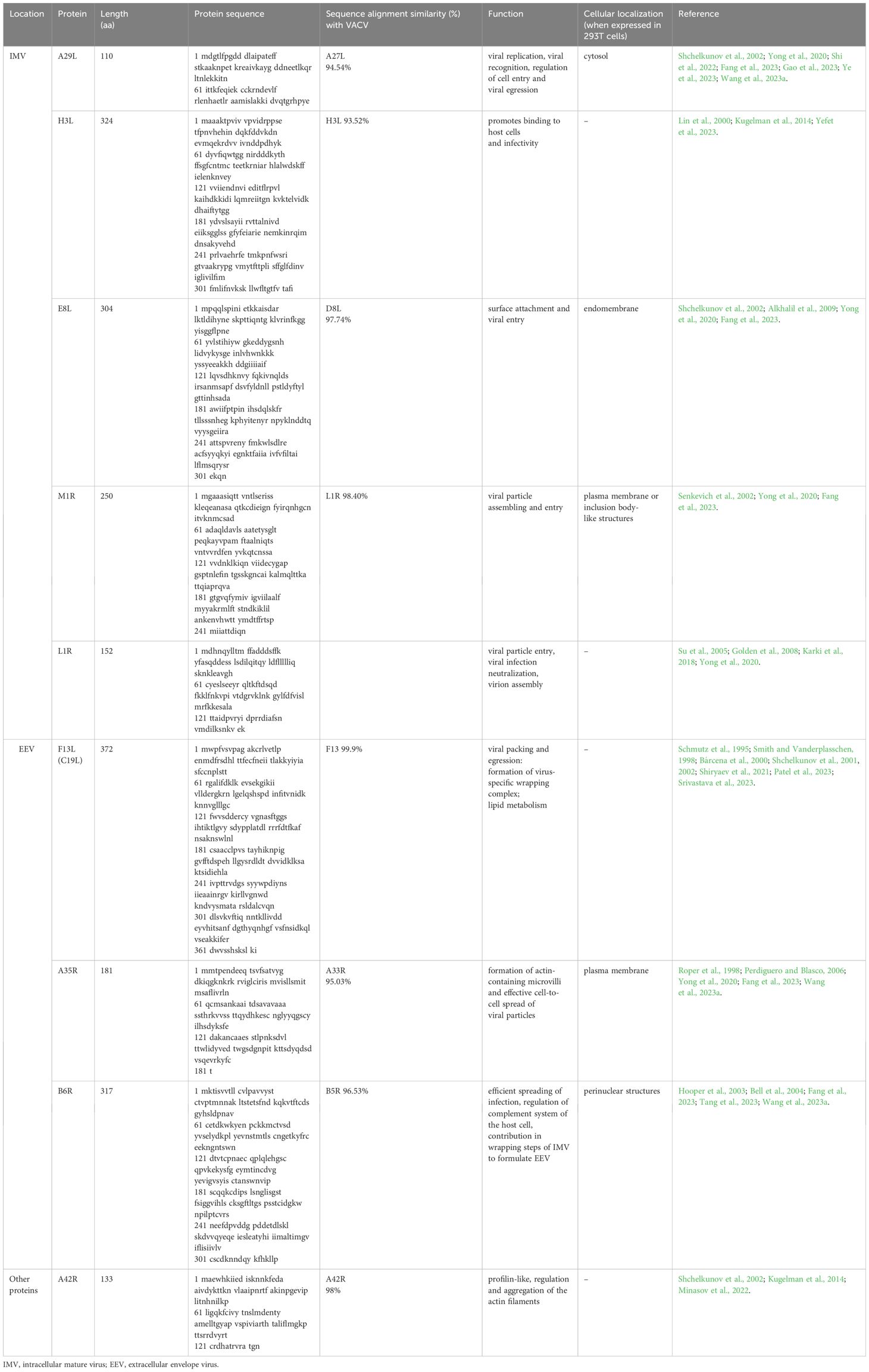

The genes encoding the MPXV structural proteins are located within the highly conserved central genomic region and expressed in different forms of the mpox virus. The EEV form of MPXV expresses 25 membrane proteins, including C19L, A35R, and B6R (Table 1). In contrast, the IMV form expresses proteins such as A29, M1R, E8L, H3L, and L1R (Shchelkunov et al., 2002). According to Freyn et al. (2022), specific MPXV proteins, homologs of VACV, such as M1 and A29, are involved in the cellular entry process of mature virus (MV), and A35 and B6 are identified as contributors to the transmission mechanism on the enveloped virus (EV) surface. Among these proteins, A35 has been identified as an essential factor for poxvirus virulence. Studies have shown that the loss of A35 protein resulted in a 1000-fold attenuation in virulence (Freyn et al., 2022). Moreover, studies indicate that antibodies against the L1R protein, located in the outer membrane of MV, can prevent the virus from infecting cells, suggesting that L1R might also have a role in the viral entry step (Shi et al., 2022).

IMV proteins

A29

MPXV A29, the ortholog of VACV A27, is a protein found on the viral envelope, particularly on IMV. It plays a crucial role in viral replication, the fusion of the virus with the host cell membrane, and viral egress (Shchelkunov et al., 2002; Gao et al., 2023). Additionally, MPXV A29 is the primary target in immunoassays that aim to detect MPXV (Shi et al., 2022). Shi et al. (2022) demonstrated the interaction of MPXV A29 protein with glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). They proposed a model for MPXV host entry, which includes (1) attachment of MPXV virion to the host cell surface through binding to heparan sulfate (HS), (2) initiation of fusion by host cell protease, and (3) eventual entry of virions into the host cell.

MPXV A29 shares a composition similarity of 94.54% with the VACV A27 (Wang et al., 2023a). Both proteins consist of 110 amino acids, which are categorized into functional parts, including an N-terminal signal peptide, a heparin-binding site (HBS), an α-helical coiled-coil domain, and a C-terminal anchoring domain (Vaázquez and Esteban, 1999). The HBS sequences of VACV 27A (STKAAKKPEAKR) and MPXV A29 (STKAAKNPETKR) differ in a single amino acid that occurred in a specific “KKPE” sequence that is essential for heparin-binding (Shih et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2022). However, despite this slight difference in the HBS sequence, Hughes et al. (2014) demonstrated that MPXV A29 and VACV 27A have a similar binding affinity to heparin.

H3L

The H3L antigen is expressed in the MV form, facilitating binding to host cells and enhancing infectivity (Lin et al., 2000). Additionally, it was discovered that anti-H3L antibodies can protect animals from a fatal attack (Davies et al., 2005). Moreover, H3L was identified as a target for T and B cells in vaccinated mice and humans (Davies et al., 2005). Specifically, H3L contains at least two recognized human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I-restricted T-cell epitopes that can trigger a potent interferon (IFN) response. This makes H3L a focus of cellular immune responses (Ostrout et al., 2007).

Yefet et al. (2023) demonstrated that MPXV antigen H3L stimulates the production of antibodies and B cells in MPXV recoverees. They also reported that such individuals have a higher frequency of H3L-specific IgG+ B cells than those recently vaccinated against the virus (Yefet et al., 2023). Meanwhile, a report by Khlusevich et al. (2022) suggests that substituting residue 233A in H3L may disrupt a B-cell epitope, making it unrecognizable by anti-VACV polyclonal antibodies.

H3L is 93.52% homologous to VACV antigen H3L (Yefet et al., 2023). Yang et al. (2023a) chemically synthesized six MPXV protective antigens (PAs) and found that H3L had the lowest cross-reactivity compared to A29L, M1R, E8L, B6R, and A35R. Its cross-reactivity value against the VACV TianTan strain (VTT) - elicited anti-serum was 33%. They also reported that, upon examining the amino acid sequences of H3 and H3L, it was observed that the 233rd residue in H3L underwent a mutation from alanine to serine. This mutation likely contributed to the limited cross-reactivity of H3L against the anti-serum elicited by VTT. Mice vaccinated with recombinant H3L protein developed an elevated level of neutralizing antibodies (mean 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50) 1:3,760) against VACV, allowing them to withstand intranasal exposures with fatal virus concentrations (Davies et al., 2005). As a result, the H3L protein is one of the main focus areas for MPXV vaccine development (Wang et al., 2023a).

E8L

E8L is an IMV surface membrane protein of 304 amino acids (Shchelkunov et al., 2002). According to UniProt, E8L (Q8V4Y0) is made up of three domains, namely the virion surface (1-275), transmembrane (276-294), and intra-virion domain (295-304) (Fantini et al., 2022). In a recent study by Fang et al. (2023), the E8L antigen was chosen for a polyvalent mRNA vaccine, and it was observed that its expression in 293T cells led to localization in the endomembrane. E8L works as a cell surface binding protein and specifically binds to chondroitin, regulating viral entry (Alkhalil et al., 2009).

It was previously shown that lipid rafts containing negatively charged gangliosides are one of the common entrance pathways OPXV uses (Byrd et al., 2013). Consequently, Fantini et al. (2022) identified the ganglioside-binding domain on the MPXV E8L protein. Using a multiparametric approach, they identified three linear epitopes overlapping with the annular ganglioside-binding motif of E8L, including amino acid sequences 43–62, 94–113, and 204–223. Consequently, these epitopes were suggested as immunogens in a vaccine formulation specific to the mpox.

M1R

M1R, an extensively preserved myristoylated surface membrane protein within IMV, plays a crucial role in the assembly and entry of viral particles (Tang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). As Yefet et al. (2023) highlighted, M1R is 98.4% homologous to the L1R of VACV. Meanwhile, Yang et al. (2023a) discovered that M1R has the most considerable cross-reactivity rate of 94% out of six MPXV PAs. This cross-reactivity may be due to B-cell epitopes, particularly those found in regions 69–91 aa and 137–155 aa regions, which overlap with those found in L1 (Heraud et al., 2006). Senkevich et al. (2002) mentioned that VACV L1R is found on the IMV membrane. In intracellular viruses, the outer domain of the L1R has three intramolecular disulfide bonds that face the cytoplasm.

M1R and L1R are essential targets for neutralizing antibodies in smallpox and cowpox viruses (CPXV) (Papukashvili et al., 2022). Fang et al. (2023) reported that M1R can be found in structures resembling the plasma membrane or inclusion bodies. Another study by Franceschi et al. (2015) demonstrated that M1R is essential for safeguarding mice against challenges, but its efficacy needs to be improved through Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccination. Despite their protective potential, booster vaccinations are necessary to ensure adequate protection (Franceschi et al., 2015).

L1R

L1R is a myristoylated membrane protein with a molecular weight ranging from 23 to 29 kDa, which shows significant conservation across OPXV (Su et al., 2005). It is situated on the surface of IMV and positioned beneath the envelope on EEV and can affect particle entry (Franke et al., 1990; Ravanello and Hruby, 1994; Wolffe et al., 1995). The general structure of L1R common to OPXVs comprises a cluster of α-helices that wrap a pair of two-stranded β-sheets linked by four loops (Su et al., 2005). Research suggests the L1R protein might play a role in the viral entry-fusion process. However, according to the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis, the MPXV L1R exhibits notably low affinity for HS, resulting in an resonance unit (RU) value of -1.3, in contrast to the MPXV A29 protein, which showed an RU value of approximately 400. Similarly, the L1R’s affinity to other GAGs, such as DS, chondroitin sulfate A (CSA), and chondroitin sulfate E (CSE), was insignificant (Shi et al., 2022). Also, the L1R protein is in charge of virion assembly. Since it is present on the surface of IMV, it is also a potent subject for evoking neutralizing antibodies (Karki et al., 2018). Moreover, monkeys vaccinated with L1R exhibited low levels of MPXV-neutralizing antibodies at the challenge despite having elevated anti-L1R antibodies detected by immunogen-specific ELISAs. This suggests that the DNA vaccine-induced anti-L1R response may have included a significant proportion of non-neutralizing antibodies. Additionally, these sera demonstrated higher levels of VACV-neutralizing antibodies, suggesting that vaccination with the MPXV L1R ortholog might be advantageous for protecting against mpox (Hooper et al., 2004).

By incorporating the tissue plasminogen leader sequence (tPA) into L1R, Golden et al. (2008) generated neutralizing antibody responses, demonstrating a geometric mean titer (GMT) of 489. Notably, this robust neutralization response was achieved with just two vaccinations. In the study conducted by Hooper et al. (2004), they investigated the efficacy of the L1R DNA vaccine in generating IMV-neutralizing antibodies and providing safety. The DNA vaccines were governed using a gene gun, and the results revealed increased levels of L1R-specific antibodies in the sera of the two vaccinated monkeys after the booster shot. Consequently, gene gun vaccination with either the 4pox DNA vaccine or the L1R DNA vaccine induced a lasting memory response, persisting for at least one to two years (e.g., monkey L201-1) (Hooper et al., 2004). Hence, alleviating the illness could result from lowering the effective challenge dose through neutralizing the challenging virus.

EEV proteins

F13

F13 (P37) is a critical envelope protein that is comprised of 372 amino acids. The MPXV gene C19L encodes it and is also called F13 (Patel et al., 2023). The F13 protein is located on the inner surface of the EEV outer membrane (Schmutz et al., 1995; Smith and Vanderplasschen, 1998). It is responsible for viral packaging and release from the host cell, facilitating viral spread and multiplication (Srivastava et al., 2023). Additionally, studies have shown that the P37 protein interacts with host membrane proteins Rab9 and TIP47 to create a virus-specific wrapping complex that is essential for the enveloped virus (Shiryaev et al., 2021; Srivastava et al., 2023). In addition to its primary function, the F13 protein also serves as an enzyme and participates in lipid metabolism (Bárcena et al., 2000).

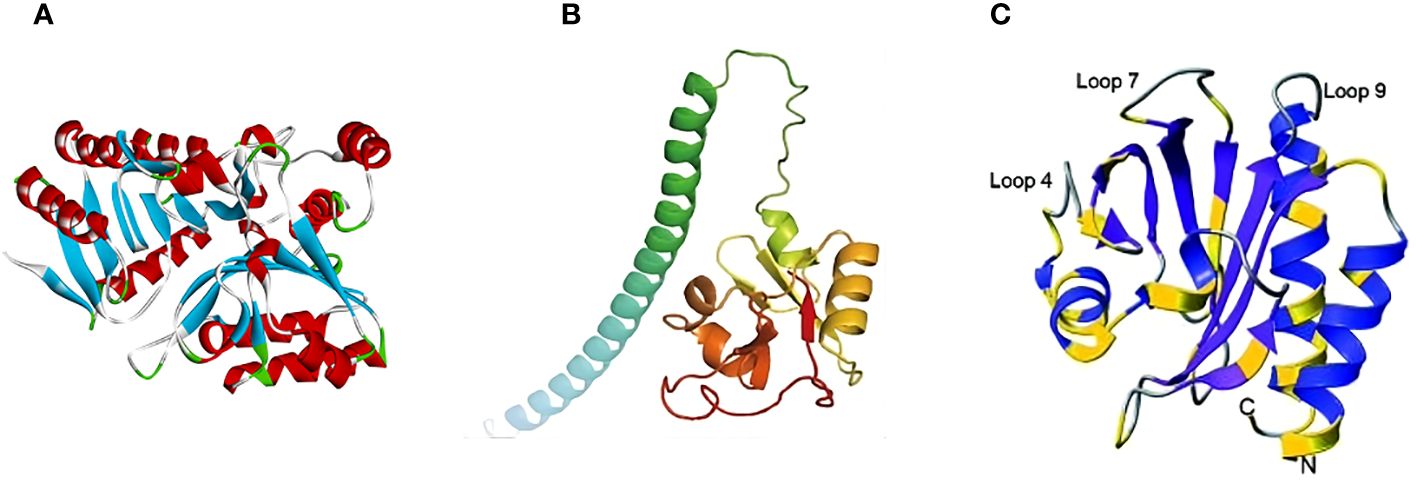

Several studies emphasized the importance of the P37 protein in the MPXV virus as a potential target for FDA-approved drugs. Shiryaev et al. (2021) noted that it has some significant benefits for virtual screening, like its relatively small size and the fact that homologs are absent in humans. The study performed high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) to identify FDA-approved drugs with higher binding affinity against MPXV. Similarly, Patel et al. (2023) predicted the 3D structure of the F13 envelope protein using Alphafold (Figure 3A), built a homology model, and evaluated it using docking, binding pose metadynamics, and molecular dynamics (MD). Likewise, another study found 15 multitargeting FDA-approved drugs that may inhibit P37 (viral packing and release), topoisomerase 1 (viral DNA replication and transcription), and thymidylate kinase (viral DNA synthesis) (Srivastava et al., 2023).

Figure 3 Predicted 3D structures of MPXV proteins: (A) F13 (adapted with permission from Patel et al., 2023); (B) A35R (adapted with permission from Zheng et al., 2022); and (C) A42R (adapted with permission from Minasov et al., 2022).

Li et al. (2022a) found that the F13 sequence is highly conserved in MPXV and VARV, and similarity ranges from 97.58% to 99.73%. Similarly, Srivastava et al. (2023) conducted a protein-protein blast analysis, revealing a sequence alignment similarity of 99.9% between MPXV and VACV. As a result, tecovirimat, formerly approved for treating smallpox, has shown potential for treating mpox. They identified the structure of the MPXV F13 protein and its residues interacting with tecovirimat through molecular simulations. Furthermore, MD analysis confirmed the drug’s efficacy against mpox (Li et al., 2022a). Additionally, there are recent studies that provide an overview of potential antivirals against P37 (Wang et al., 2023b; Ashley et al., 2024) and other mpox proteins (Bajrai et al., 2022; Kaur et al., 2023).

A35R

A35R, a homolog of VACV A33R, is an envelope glycoprotein of EV, contributing to the formation of actin-containing microvilli and facilitating the effective cell-to-cell spread of viral particles (Roper et al., 1998; Perdiguero and Blasco, 2006). According to Wang et al. (2023a), the A35R protein shares 95.03% similarity with the A33R protein from VACV. Su et al. (2010) found that VACV A33R is a homodimeric transmembrane protein that undergoes O- and N-glycosylation at the N-125 and N-135 sites, while MPXV A35R does not possess the corresponding N-125 site. Moreover, it was shown that a few amino acid differences between these two proteins could influence the effectiveness of the smallpox vaccine in providing cross-protection against mpox. For instance, the anti-A33 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) 1G10 and 10F10 showed high specificity for VACV A33R. However, in the case of MPXV A35R, 10F10 demonstrated an affinity to MPXV A35R, while 1G10 resulted in no binding (Golden and Hooper, 2008). The 3D structure of MPXV A35R was predicted by Zheng et al. (2022) using AlphaFold2 (Figure 3B). Consequently, the study showed the structural similarity of MPXV A35R and VACV A33R, especially in their globular domains (Zheng et al., 2022).

Fang et al. (2023) generated a polyvalent mRNA vaccine candidate, MPXVac-097, using five MPXV antigens such as A35R, B6R, A29L, E8L, and M1R linked by tandem dimer peptide linkage. As a result, after the second and third doses of the MPXVac-097 vaccination, antibody titer levels of A35R and E8L increased significantly, indicating a robust antibody response. However, the response was moderate to M1R and low to A29L and B6R antigens. The localization of the A35R protein to the plasma membrane was identified after expressing the A35R antigen in 293T cells (Fang et al., 2023). Three anti-MPXV A35 nanobodies from a non-immunized alpaca heavy-chain antibody (VHH) library were recently designed (Meng et al., 2023). As a result, VHH-1 demonstrated the highest affinity and specificity against MPXV A35R, with a half-maximal effective concentration EC50 of 0.010 µg/mL. Similarly, as the result of analysis using the protein A biosensor, VHH-1 demonstrated binding to the mpox A35R protein with an affinity constant of 54 nM, determined via the biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay, thereby providing a fundamental basis for the potential advancement of the diagnostic instruments for the mpox virus (Meng et al., 2023).

B6R

B6R is a glycoprotein that undergoes reversible lipid modifications called palmitoylation (Tang et al., 2023). These modifications are considered a crucial mechanism of protein trafficking to the membrane. Hence, it is essential for localizing B6R on the surface membrane of infected cells and the EEV (Guan and Fierke, 2011; Tang et al., 2023). B6R is the homolog of VACV B5R, showing a similarity of 96.53% (Wang et al., 2023a). Like B5R, B6R is vital for the efficient spreading of infection and is involved in the regulation of the complement system of the host cell (Smith and Vanderplasschen, 1998; Tang et al., 2023). B5R also contributes to formulating EEV during the wrapping steps of IMV (Bell et al., 2004). Fang et al. (2023) selected the MPXV B6R antigen as one of the candidates for inclusion in a polyvalent mRNA vaccine candidate, MPXVas-097. As discussed earlier, they showed a low antibody titer after a three-dose vaccination. The same study identified that its expression in 293T cells led to localization in perinuclear structures. Moreover, the B6R protein was recognized as the primary target for rt-PCR assay targeting MPXV. Li et al. (2006) designed an rt-PCR assay, namely a B6R assay, specifically detecting B6R envelope protein. As a result, all 15 strains of MPXV were detected at 10 ng with the B6R assay, and no cross-reaction was observed with other OPXV and bacterial strains.

Profilin-like proteins

A42R

The A42R protein is encoded by the gp153 locus of the MPXV virus, and its amino acid sequence highly resembles profilin proteins (Minasov et al., 2022). Profilins are actin-binding proteins that regulate and aggregate actin filaments (Pinto-Costa and Sousa, 2020). It was found that VACV A42R, homolog to profilin, shares 98% similarity with MPXV virus A42R, and it is a late synthesized protein that exhibits a weak affinity for actin (Minasov et al., 2022). In the previous studies, knockout of the open reading frames (ORF) for VACV A42R and CPXV A42R showed that they are not crucial for poxvirus replication in vivo (Blasco et al., 1991). However, according to the authors, they may play a vital role during viral replication in various cell lines (Minasov et al., 2022).

Minasov et al. (2022) identified the structure of MPXV A42R protein (Figure 3C) through the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) technique using X-ray diffraction data collected from crystals of seleno-methionine derivatized protein at a resolution of 1.52 Å. The principle of X-ray diffraction lies in the interaction of X-rays with the electron clouds on the crystal atoms, creating the diffraction pattern (Liebschner et al., 2019). The protein has an asymmetric structure composed of two polypeptide chains, chains A and B. Chain A is a full-length chain containing 133 amino acid residues. It begins with N-terminus alanine, which originates from the tobacco mosaic virus protease. On the other hand, chain B lacks N-terminal alanine and starts from the second amino acid up to the 133rd. Generally, the structure contains a seven-stranded antiparallel beta-sheet encircled by three alpha helices and a partially formed helix (Minasov et al., 2022). Structural analysis of MPXV A42R with bovine and human profilin proteins uncovered notable differences in critical functional regions. Specifically, it was revealed that, unlike profilins, MPXV A42R has a weak affinity for actin and no affinity for poly (l-proline). In addition to this, A42R may establish specific interactions with phosphatidylinositol lipids. This suggests that understanding the function of cellular profilin may not be sufficient to predict the role of MPXV A42R (Minasov et al., 2022).

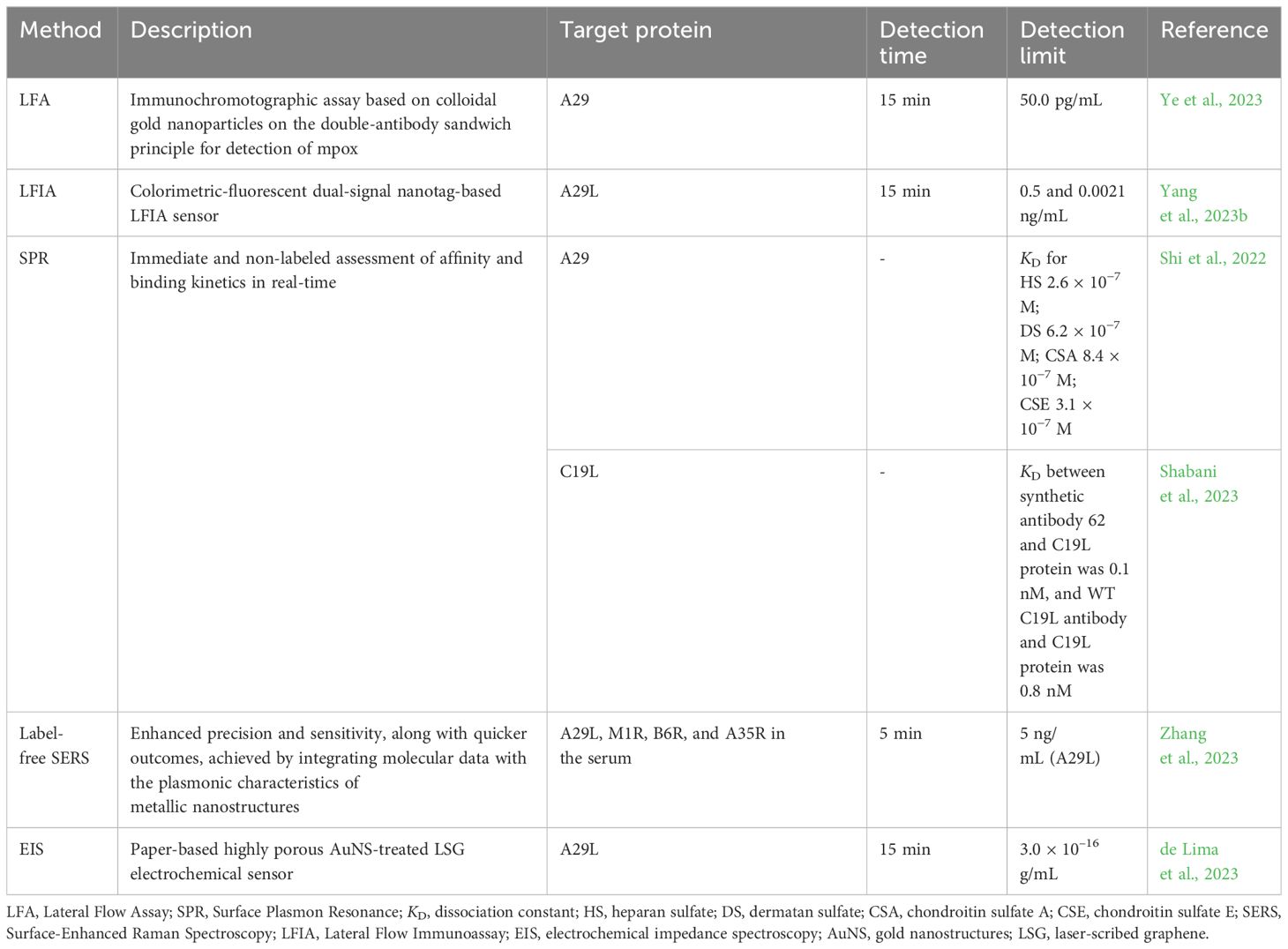

Rapid detection techniques

Several detection techniques for mpox are being used nowadays. For instance, lateral flow assay (LFA), also known as immunochromatography, is driven by capillary action and provides quick detection employing colloidal gold nanoparticles as immunolabels, producing results in 10-15 minutes at a cheap cost and with simple standardization (Urusov et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022; Ye et al., 2023). Immunology-based LFA assays are popular for quick test times and convenience (Qriouet et al., 2021). Ye et al. (2023) developed a colloidal gold immunochromatographic method for monkeypox virus detection that uses the A29 17-49 peptide sequence as the immunogen and produces monkeypox-specific mAbs. Rapid test strips were developed using the double-antibody sandwich approach, which has great specificity and sensitivity. It was found that two specific antibodies, namely mAb-7C5 and 5D8, resulted in the best sensitivity and detection of the limit of 50 pg mL−1 for the A29 protein (Table 2). Moreover, the test strips did not show cross-reactivity with other OPXVs, including VACV and CPXV, and other infections, such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A and B (Ye et al., 2023).

Yang et al. (2023b) established a dual-signal nanotag-based lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) system for swift and sensitive detection of the A29L protein. They investigated the ideal reaction time for LFIA, examining the T-line’s signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) across various time intervals. The findings indicated that a reaction period of 15 minutes proved adequate for quantitatively detecting MPXV. The dual-signal SiO2-Au core dual-QD shell (DQD) nanocomposite (Si-Au/DQD)-based LFIA has a colorimetric sensitivity of 0.5 ng/mL and fluorescence sensitivity of 0.021 ng/mL, outperforming the standard AuNP-based LFIA and ELISA procedures by 238 and 3.3 times, respectively (Yang et al., 2023b).

Virus proteins, including mpox, were also analyzed using alternative techniques such as SPR. Shi et al. (2022) showed the interaction of MPXV A29 protein with GAGs, HS, dermatan (DS), CSA, and CSE using SPR. As a result, the obtained dissociation constant (KD) values (Table 2) indicated that MPXV A29 exhibited a strong affinity for GAGs, including HS, DS, and CS. Likewise, the same study employed SPR to study the affinity of the MPXV L1R protein to GAG. Shabani et al. (2023) designed a new synthetic anti-MPXV C19L antibody (antibody 62) based on a heavy chain of human antibodies and a small peptide fragment at its beginning. The docking and molecular simulation analysis of the designed anti-MPXV C19L antibodies were applied to select the one with superior stability. The interaction between the C19L protein and the synthetic and wild-type anti-C19L antibodies was analyzed using SPR. The findings showed that synthetic antibodies’ KD value was lower than wild antibodies, 0.1 and 0.8 nM, respectively, meaning that synthetic antibodies had a higher affinity for MPXV C19L protein (Shabani et al., 2023). In this manner, SPR enabled a label-free, direct, and real-time quantitative assessment of molecular interactions (Shi et al., 2022).

Because of its low cost, speed, high sensitivity, specificity, and noninvasiveness, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has been frequently utilized to detect harmful microorganisms (Huang et al., 2021). Unlabeled detection eliminates the need for attaching molecular markers like specific antibodies and nucleic acid sequences onto nanoparticle surfaces, simplifying the preparation of the enhanced substrate and allowing for rapid sample detection (Zhang et al., 2023). Zhang et al. (2023) also emphasized that despite SERS’s robust detection features, some technical hurdles in unlabeled virus identification must be overcome, such as the difficulty in recording signals and insufficient applicability because of the size distinction between SERS “hot spots” and viruses. Consequently, they used silver nanoparticles incubated with iodine ions and aggregated with calcium ions as substrates to resolve the limitation of unlabeled MPXV detection of the SERS. As a result, the new approach showed the detection of MPXV A29L protein at a concentration as low as 5 ng/mL and MPXV DNA at levels as low as 100 copies/mL within 2 minutes, which is close to the lower limit of PCR detection but faster. Furthermore, SERS has shown excellent potential for quantitatively detecting MPXV as it was able to identify four distinct MPXV proteins, including A29L, M1R, B6R, and A35R, in the serum in 5 minutes (Zhang et al., 2023).

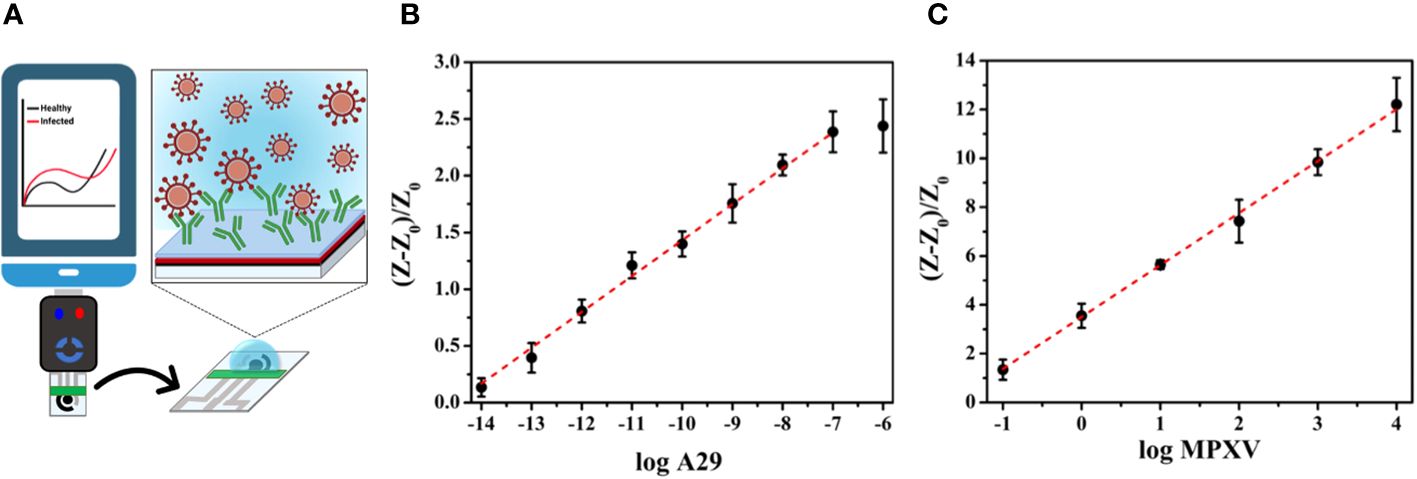

Electrochemical biosensors are another attractive approach that offer typical rapid testing times, convenient device portability, and compact device size, which lower sample volumes required for testing and remove sample pretreatment steps, making them suitable for point-of-care applications (POC). To ensure optimal use in POC settings, electrochemical devices must be reproducible and easily accessible, allowing them to be disposable and removing the requirement for trained personnel (Torres et al., 2021). de Lima et al. (2023) reported the first electrochemical POC assay for MPXV protein detection using a paper-based laser-scribed graphene (LSG) nanobiosensor (Figure 4A). The results showed that the test required a small amount of sample (2.5 µL), detection within 15 min, and a limit of detections (LODs) of 3.0 × 10–16 g mL–1 for A29 protein and 7.8 × 10–3 PFU L–1 for titered MPXV. The analytical curves for A29 protein and MPXV viral loads at various concentrations showed a linear correlation with a determination coefficient (R2) of 0.998 and 0.996, respectively (Figures 4B, C). Additionally, no instances of cross-reaction were detected when the nanobiosensor was tested alongside other poxvirus and non-poxvirus strains (de Lima et al., 2023).

Figure 4 (A) Schematic illustration of an LSG nanobiosensor-based electrochemical assay for MPXV detection linked to a portable potentiostat controlled via a smartphone; (B) The analytical curve presenting normalized resistance to charge transfer (RCT) values against the logarithm of the A29 protein concentration; (C) The analytical curve presenting the normalized RCT values against the logarithm of the titered MPXV sample (adapted with permission from de Lima et al., 2023).

Conclusion and future directions

Mpox, a zoonotic disease caused by MPXV, presents challenges in diagnosis due to symptom similarities with other infectious diseases. Despite the current decrease in confirmed infection cases, addressing the ongoing threat of mpox remains imperative, especially considering its potential emergence in previously non-endemic areas. Therefore, rapid and specific detection methods are crucial for controlling its global spread. Consequently, this review provided a comprehensive overview of the characterization of mpox proteins and the development of rapid techniques for MPXV detection. Specifically, we highlighted pathogenesis, the roles and structural characteristics of EEV (C19L, A35R, and B6R), IMV (A29, M1R, E8L, H3L, and L1R), and profilin-like proteins. Additionally, recent studies in diagnostic techniques such as LFA, LFIA, SPR, SERS, and EIS using these mpox proteins demonstrated promising paths for rapid detection of MPXV. Recently, viral detection methods based on aptamers have been developed with considerable success (Xi et al., 2021; Shola David and Kanayeva, 2022). Unlike protein biorecognition elements, including antibodies, nucleic acid aptamers can be readily paired with various electrochemical and optical sensing methods, opening new avenues for sensitive and rapid detection (Zhang et al., 2023). However, it is crucial to note that despite the advancements, there is still a gap in understanding most mpox proteins. Notably, while the 3D structure of A42R has been revealed, predicted 3D structures are available for proteins C19L and A35R, while others still need to be explored. This emphasizes the necessity for further research on mpox protein structure and function. Enhancing knowledge of mpox proteins is essential for improving diagnostic techniques to address emerging viral infections effectively.

Author contributions

DK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AB: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (grant AP19577309).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adalja, A., Inglesby, T. (2022). A novel international monkeypox outbreak. Ann. Internal Med. 175, pp.1175–1176. doi: 10.7326/M22-1581

Alakunle, E., Moens, U., Nchinda, G., Okeke, M. I. (2020). Monkeypox virus in Nigeria: infection biology, epidemiology, and evolution. Viruses 12, p.1257. doi: 10.3390/v12111257

Alkhalil, A., Strand, S., Mucker, E., Huggins, J. W., Jahrling, P. B., Ibrahim, S. M. (2009). Inhibition of Monkeypox virus replication by RNA interference. Virol. J. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-188

Al-Musa, A., Chou, J., LaBere, B. (2022). The resurgence of a neglected orthopoxvirus: Immunologic and clinical aspects of monkeypox virus infections over the past six decades. Clin. Immunol. 243, 109108. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2022.109108

Ashley, C. N., Broni, E., Wood, C. M., Okuneye, T., Ojukwu, M. P. T., Dong, Q., et al. (2024). Identifying potential monkeypox virus inhibitors: an in silico study targeting the A42R protein. Front. Cell. Infection Microbiol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1351737

Bajrai, L. H., Alharbi, A. S., El-Day, M. M., Bafaraj, A. G., Dwivedi, V. D., Azhar, E. I. (2022). Identification of antiviral compounds against monkeypox virus profilin-like protein A42R from plantago lanceolata. Molecules 27, 7718. doi: 10.3390/molecules27227718

Bárcena, J., Lorenzo, M. M., Sánchez-Puig, J. M., Blasco, R. (2000). Sequence and analysis of a swinepox virus homologue of the vaccinia virus major envelope protein P37 (F13L). J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1073–1085. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-1073

Bell, E., Shamim, M., Whitbeck, J. C., Sfyroera, G., Lambris, J. D., Isaacs, S. N. (2004). Antibodies against the extracellular enveloped virus B5R protein are mainly responsible for the EEV neutralizing capacity of vaccinia immune globulin. Virology 325, 425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.05.004

Bhalla, N., Payam, A. F. (2023). Addressing the silent spread of monkeypox disease with advanced analytical tools. Small 19 (9). doi: 10.1002/smll.202206633

Blasco, R., Cole, N. B., Moss, B. (1991). Sequence analysis, expression, and deletion of a vaccinia virus gene encoding a homolog of profilin, a eukaryotic actin-binding protein. J. Virol. 65, 4598–4608. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4598-4608.1991

Breman, J. G., Steniowski, M. V., Zanotto, E., Gromyko, A. I., Arita, I. (1980). Human monkeypox 1970-79. Bull. World Health Organ. 58 (2), 165.

Byrd, D., Amet, T., Hu, N., Lan, J., Hu, S., Yu, Q. (2013). Primary human leukocyte subsets differentially express vaccinia virus receptors enriched in lipid rafts. J. Virol. 87, 9301–9312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01545-13

Chauhan, R. P., Fogel, R., Limson, J. (2023). Overview of diagnostic methods, disease prevalence and transmission of MPOX (formerly monkeypox) in humans and animal reservoirs. Microorganisms 11, 1186. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11051186

Cho, C. T., Wenner, H. A. (1973). Monkeypox virus. Bacteriological Rev. 37, 1–18. doi: 10.1128/br.37.1.1-18.1973

Davies, D. H., McCausland, M. M., Valdez, C., Huynh, D., Hernandez, J. E., Mu, Y., et al. (2005). Vaccinia virus H3L envelope protein is a major target of neutralizing antibodies in humans and elicits protection against lethal challenge in mice. J. Virol. 79, 11724–11733. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11724-11733.2005

de Lima, L. F., Barbosa, P. P., Simeoni, C. L., de Paula, R., Proenca-Modena, J. L., de Araujo, W. R. (2023). Electrochemical paper-Based nanobiosensor for rapid and sensitive detection of monkeypox virus. ACS Appl. Materials Interfaces 15, 58079–58091. doi: 10.1021/acsami.3c10730

Durmuş, S., Ülgen, K.Ö. (2017). Comparative interactomics for virus–human protein–protein interactions: DNA viruses versus RNA viruses. FEBS Open Bio 7, 96–107. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12167

Fang, Z., Monteiro, V. S., Renauer, P. A., Shang, X., Suzuki, K., Ling, X., et al. (2023). Polyvalent mRNA vaccination elicited potent immune response to monkeypox virus surface antigens. Cell Res. 33, 407–410. doi: 10.1038/s41422-023-00792-5

Fantini, J., Chahinian, H., Yahi, N. (2022). A vaccine strategy based on the identification of an annular ganglioside binding motif in Monkeypox virus protein E8L. Viruses 14, 2531. doi: 10.3390/v14112531

Fine, P. E., Jezek, Z., Grab, B., Dixon, H. (1988). The transmission potential of monkeypox virus in human populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 17, 643–650. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.3.643

Franceschi, V., Parker, S., Jacca, S., Crump, R. W., Doronin, K., Hembrador, E., et al. (2015). BoHV-4-based vector single heterologous antigen delivery protects STAT1 (-/-) mice from monkeypoxvirus lethal challenge. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003850

Franke, C. A., Wilson, E. M., Hruby, D. E. (1990). Use of a cell-free system to identify the vaccinia virus L1R gene product as the major late myristylated virion protein M25. J. Virol. 64, 5988–5996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.5988-5996.1990

Freyn, A. W., Atyeo, C., Earl, P. L., Americo, J. L., Chuang, G. Y., Natarajan, H., et al. (2022). A monkeypox mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine targeting virus binding, entry, and transmission drives protection against lethal orthopoxviral challenge. BioRxiv, 2022–2012. doi: 10.1101/2022.12.17.520886

Gao, F., He, C., Liu, M., Yuan, P., Tian, S., Zheng, M., et al. (2023). Cross-reactive immune responses to monkeypox virus induced by MVA vaccination in mice. Virol. J. 20, 126. doi: 10.1186/s12985-023-02085-0

Golden, J. W., Hooper, J. W. (2008). Heterogeneity in the A33 protein impacts the cross-protective efficacy of a candidate smallpox DNA vaccine. Virology 377, 19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.003

Golden, J. W., Josleyn, M. D., Hooper, J. W. (2008). Targeting the vaccinia virus L1 protein to the cell surface enhances production of neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine 26, 3507–3515. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.017

Gong, Q., Wang, C., Chuai, X., Chiu, S. (2022). Monkeypox virus: a re-emergent threat to humans. Virologica Sin. 37, 477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.07.006

Guan, X., Fierke, C. A. (2011). Understanding protein palmitoylation: Biological significance and enzymology. Sci. China Chem. 54, 1888–1897. doi: 10.1007/s11426-011-4428-2

Gubser, C., Hué, S., Kellam, P., Smith, G. L. (2004). Poxvirus genomes: a phylogenetic analysis. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 105–117. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19565-0

Halvaei, P., Zandi, S., Zandi, M. (2023). Biosensor as a novel alternative approach for early diagnosis of monkeypox virus. Int. J. Surg. 109, 50–52. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000115

Heraud, J. M., Edghill-Smith, Y., Ayala, V., Kalisz, I., Parrino, J., Kalyanaraman, V. S., et al. (2006). Subunit recombinant vaccine protects against monkeypox. J. Immunol. 177, 2552–2564. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2552

Hooper, J. W., Custer, D. M., Thompson, E. (2003). Four-gene-combination DNA vaccine protects mice against a lethal vaccinia virus challenge and elicits appropriate antibody responses in nonhuman primates. Virology 306, 181–195. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(02)00038-7

Hooper, J. W., Thompson, E., Wilhelmsen, C., Zimmerman, M., Ichou, M. A., Steffen, S. E., et al. (2004). Smallpox DNA vaccine protects nonhuman primates against lethal monkeypox. J. Virol. 78, 4433–4443. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4433-4443.2004

Huang, J., Wen, J., Zhou, M., Ni, S., Le, W., Chen, G., et al. (2021). On-site detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen by deep learning-based surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and its biochemical foundations. Analytical Chem. 93, 9174–9182. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01061

Hughes, L. J., Goldstein, J., Pohl, J., Hooper, J. W., Pitts, R. L., Townsend, M. B., et al. (2014). A highly specific monoclonal antibody against monkeypox virus detects the heparin binding domain of A27. Virology 464, 264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.06.039

Karagoz, A., Tombuloglu, H., Alsaeed, M., Tombuloglu, G., AlRubaish, A. A., Mahmoud, A., et al. (2023). Monkeypox (mpox) virus: Classification, origin, transmission, genome organization, antiviral drugs, and molecular diagnosis. J. infection Public Health 16, 531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.02.003

Karki, M., Kumar, A., Venkatesan, G., Arya, S., Pandey, A. B. (2018). Genetic analysis of L1R myristoylated protein of Capripoxviruses reveals structural homogeneity among poxviruses. Infection Genet. Evol. 58, 224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.01.001

Kaur, M., Sharma, A., Kaur, H., Singh, M., Devi, B., Naresh Raj, A. R., et al. (2023). Screening of potential inhibitors against structural proteins from Monkeypox and related viruses of Poxviridae family via docking and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Biomolecular Structure Dynamics, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2259489

Khanna, M., Ranasinghe, C., Jackson, R., Parish, C. R. (2017). Heparan sulfate as a receptor for poxvirus infections and as a target for antiviral agents. J. Gen. Virol. 98, 2556–2568. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000921

Khlusevich, Y., Matveev, A., Emelyanova, L., Goncharova, E., Golosova, N., Pereverzev, I., et al. (2022). New p35 (H3L) epitope involved in vaccinia virus neutralization and its deimmunization. Viruses 14, 1224. doi: 10.3390/v14061224

Kugelman, J. R., Johnston, S. C., Mulembakani, P. M., Kisalu, N., Lee, M. S., Koroleva, G., et al. (2014). Genomic variability of monkeypox virus among humans, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerging Infect. Dis. 20, 232. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.130118

Kumar, N., Acharya, A., Gendelman, H. E., Byrareddy, S. N. (2022). The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J. Autoimmun. 131, 102855. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102855

Li, D., Liu, Y., Li, K., Zhang, L. (2022a). Targeting F13 from monkeypox virus and variola virus by tecovirimat: Molecular simulation analysis. J. infection 85, e99–e101. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.07.001

Li, Y., Olson, V. A., Laue, T., Laker, M. T., Damon, I. K. (2006). Detection of monkeypox virus with real-time PCR assays. J. Clin. Virol. 36, 194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.03.012

Li, H., Zhang, H., Ding, K., Wang, X. H., Sun, G. Y., Liu, Z. X., et al. (2022b). The evolving epidemiology of monkeypox virus. Cytokine Growth factor Rev. 68, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2022.10.002

Liebschner, D., Afonine, P. V., Baker, M. L., Bunkóczi, G., Chen, V. B., Croll, T. I., et al. (2019). Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Struct. Biol. 75, 861–877. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471

Lin, C. L., Chung, C. S., Heine, H. G., Chang, W. (2000). Vaccinia virus envelope H3L protein binds to cell surface heparan sulfate and is important for intracellular mature virion morphogenesis and virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 74, 3353–3365. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.7.3353-3365.2000

Luna, N., Ramírez, A. L., Muñoz, M., Ballesteros, N., Patiño, L. H., Castañeda, S. A., et al. (2022). Phylogenomic analysis of the monkeypox virus (MPXV) 2022 outbreak: Emergence of a novel viral lineage? Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 49, 102402. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102402

Magnus, P. V., Andersen, E. K., Petersen, K. B., Birch Andersen, A. (1959). A pox-like disease in cynomolgus monkeys. Acta Pathologica Microbiologica Scandinavica. 46 (2), 156–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1959.tb00328.x

McCollum, A. M., Damon, I. K. (2014). Human monkeypox. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 260–267. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit703

Meng, N., Cheng, X., Sun, M., Zhang, Y., Sun, X., Liu, X., et al. (2023). Screening, expression and identification of nanobody against monkeypox virus A35R. Int. J. Nanomedicine 18, 7173–7181. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S431619

Minasov, G., Inniss, N. L., Shuvalova, L., Anderson, W. F., Satchell, K. J. (2022). Structure of the Monkeypox virus profilin-like protein A42R reveals potential functional differences from cellular profilins. Acta Crystallographica Section F: Struct. Biol. Commun. 78, 371–377. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X22009128

Montanuy, I., Alejo, A., Alcami, A. (2011). Glycosaminoglycans mediate retention of the poxvirus type I interferon binding protein at the cell surface to locally block interferon antiviral responses. FASEB J. 25, 1960. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177188

Ostrout, N. D., McHugh, M. M., Tisch, D. J., Moormann, A. M., Brusic, V., Kazura, J. W. (2007). Long-term T cell memory to human leucocyte antigen-A2 supertype epitopes in humans vaccinated against smallpox. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 149, 265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03401.x

Papukashvili, D., Rcheulishvili, N., Liu, C., Wang, X., He, Y., Wang, P. G. (2022). Strategy of developing nucleic acid-based universal monkeypox vaccine candidates. Front. Immunol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1050309

Patel, C. N., Mall, R., Bensmail, H. (2023). AI-driven drug repurposing and binding pose meta dynamics identifies novel targets for monkeypox virus. J. Infection Public Health 16, 799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.03.007

Perdiguero, B., Blasco, R. (2006). Interaction between vaccinia virus extracellular virus envelope A33 and B5 glycoproteins. J. Virol. 80, 8763–8777. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00598-06

Pinto-Costa, R., Sousa, M. M. (2020). Profilin as a dual regulator of actin and microtubule dynamics. Cytoskeleton 77, 76–83. doi: 10.1002/cm.21586

Qriouet, Z., Cherrah, Y., Sefrioui, H., Qmichou, Z. (2021). Monoclonal antibodies application in lateral flow immunochromatographic assays for drugs of abuse detection. Molecules 26, 1058. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041058

Ravanello, M. P., Hruby, D. E. (1994). Conditional lethal expression of the vaccinia virus L1R myristylated protein reveals a role in virion assembly. J. Virol. 68, 6401–6410. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6401-6410.1994

Roper, R. L., Wolffe, E. J., Weisberg, A., Moss, B. (1998). The envelope protein encoded by the A33R gene is required for formation of actin-containing microvilli and efficient cell-to-cell spread of vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 72, 4192–4204. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.5.4192-4204.1998

Schmutz, C., Rindisbacher, L., Galmiche, M. C., Wittek, R. (1995). Biochemical analysis of the major vaccinia virus envelope antigen. Virology 213, 19–27. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1542

Senkevich, T. G., Ojeda, S., Townsley, A., Nelson, G. E., Moss, B. (2005). Poxvirus multiprotein entry–fusion complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 18572–18577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509239102

Senkevich, T. G., White, C. L., Koonin, E. V., Moss, B. (2002). Complete pathway for protein disulfide bond formation encoded by poxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 6667–6672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062163799

Shabani, S., Rashidi, M., Radgoudarzi, S., Jebali, A. (2023). The validation of artificial anti-monkeypox antibodies by in silico and experimental approaches. Immunity Inflammation Dis. 11, e834. doi: 10.1002/iid3.834

Shchelkunov, S. N., Totmenin, A. V., Babkin, I. V., Safronov, P. F., Ryazankina, O. I., Petrov, N. A., et al. (2001). Human monkeypox and smallpox viruses: genomic comparison. FEBS Lett. 509, 66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03144-1

Shchelkunov, S. N., Totmenin, A. V., Safronov, P. F., Mikheev, M. V., Gutorov, V. V., Ryazankina, O. I., et al. (2002). Analysis of the monkeypox virus genome. Virology 297, 172–194. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1446

Shi, D., He, P., Song, Y., Cheng, S., Linhardt, R. J., Dordick, J. S., et al. (2022). Kinetic and structural aspects of glycosaminoglycan–monkeypox virus protein A29 interactions using surface plasmon resonance. Molecules 27, 5898. doi: 10.3390/molecules27185898

Shih, P. C., Yang, M. S., Lin, S. C., Ho, Y., Hsiao, J. C., Wang, D. R., et al. (2009). A turn-like structure “KKPE” segment mediates the specific binding of viral protein A27 to heparin and heparan sulfate on cell surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 36535–36546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037267

Shiryaev, V. A., Skomorohov, M. Y., Leonova, M. V., Bormotov, N. I., Serova, O. A., Shishkina, L. N., et al. (2021). Adamantane derivatives as potential inhibitors of p37 major envelope protein and poxvirus reproduction. Design, synthesis and antiviral activity. Eur. J. Medicinal Chem. 221, 113485. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113485

Shola David, M., Kanayeva, D. (2022). Enzyme linked oligonucleotide assay for the sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Front. Cell. Infection Microbiol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1017542

Smith, G. L., Vanderplasschen, A. (1998). “Extracellular Enveloped Vaccinia Virus,” in Coronaviruses and Arteriviruses. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. ed. Enjuanes, L., Siddell, S. G., Spaan, W. (Boston, MA: Springer) 440, 395–414. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_51

Srivastava, V., Naik, B., Godara, P., Das, D., Mattaparthi, V. S. K., Prusty, D. (2023). Identification of FDA-approved drugs with triple targeting mode of action for the treatment of monkeypox: a high throughput virtual screening study. Mol. Diversity, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11030-023-10636-4

Su, H. P., Garman, S. C., Allison, T. J., Fogg, C., Moss, B., Garboczi, D. N. (2005). The 1.51-Å structure of the poxvirus L1 protein, a target of potent neutralizing antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501103102

Su, H. P., Singh, K., Gittis, A. G., Garboczi, D. N. (2010). The structure of the poxvirus A33 protein reveals a dimer of unique C-type lectin-like domains. J. Virol. 84, 2502–2510. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02247-09

Tang, D., Liu, X., Lu, J., Fan, H., Xu, X., Sun, K., et al. (2023). Recombinant proteins A29L, M1R, A35R, and B6R vaccination protects mice from mpox virus challenge. Front. Immunol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1203410

Torres, M. D., de Araujo, W. R., de Lima, L. F., Ferreira, A. L., de la Fuente-Nunez, C. (2021). Low-cost biosensor for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 at the point of care. Matter 4, 2403–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2021.05.003

Urusov, A. E., Zherdev, A. V., Dzantiev, B. B. (2019). Towards lateral flow quantitative assays: detection approaches. Biosensors 9, 89. doi: 10.3390/bios9030089

Vaázquez, M. I., Esteban, M. (1999). Identification of functional domains in the 14-kilodalton envelope protein (A27L) of vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 73, 9098–9109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.11.9098-9109.1999

Wang, J., Shahed-AI-Mahmud, M., Chen, A., Li, K., Tan, H., Joyce, R. (2023b). An overview of antivirals against monkeypox virus and other orthopoxviruses. J. medicinal Chem. 66, 4468–4490. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00069

Wang, Y., Yang, K., Zhou, H. (2023a). Immunogenic proteins and potential delivery platforms for mpox virus vaccine development: a rapid review. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules 245, 125515. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125515

Wang, Z., Zhao, J., Xu, X., Guo, L., Xu, L., Sun, M., et al. (2022). An overview for the nanoparticles-based quantitative lateral flow assay. Small Methods 6, 2101143. doi: 10.1002/smtd.202101143

Weaver, J. R., Isaacs, S. N. (2008). Monkeypox virus and insights into its immunomodulatory proteins. Immunol. Rev. 225, 96–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00691.x

Witt, A. S. A., Trindade, G. D. S., Souza, F. G. D., Serafim, M. S. M., da Costa, A. V. B., Silva, M. V. F., et al. (2023). Ultrastructural analysis of monkeypox virus replication in Vero cells. J. Med. Virol. 95, e28536. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28536

Wolffe, E. J., Vijaya, S., Moss, B. (1995). A myristylated membrane protein encoded by the vaccinia virus L1R open reading frame is the target of potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Virology 211, 53–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1378

World Health Organization (2022) Second meeting of the International Health Regulations, (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-07-2022-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-(ihr)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox (Accessed May 1, 2024)

World Health Organization (2024) 2022-23 MPXV (Monkeypox) Outbreak: Global Trends. Available online at: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/#2_Global_situation_update (Accessed May 1, 2024).

Xi, H., Jiang, H., Juhas, M., Zhang, Y. (2021). Multiplex biosensing for simultaneous detection of mutations in SARS-CoV-2. ACS Omega 6, 25846–25859. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c04024

Yang, L., Chen, Y., Li, S., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., Pei, R., et al. (2023a). Immunization of mice with vaccinia virus Tiantan strain yields antibodies cross-reactive with protective antigens of monkeypox virus. Virologica Sin. 38, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.virs.2022.10.004

Yang, X., Cheng, X., Wei, H., Tu, Z., Rong, Z., Wang, C., et al. (2023b). Fluorescence-enhanced dual signal lateral flow immunoassay for flexible and ultrasensitive detection of monkeypox virus. J. Nanobiotechnology 21, 450. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-02215-4

Ye, L., Lei, X., Xu, X., Xu, L., Kuang, H., Xu, C. (2023). Gold-based paper for antigen detection of monkeypox virus. Analyst 148, 985–994. doi: 10.1039/D2AN02043B

Yefet, R., Friedel, N., Tamir, H., Polonsky, K., Mor, M., Cherry-Mimran, L., et al. (2023). Monkeypox infection elicits strong antibody and B cell response against A35R and H3L antigens. IScience 26 (2), 105957. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.105957

Yong, S. E. F., Ng, O. T., Ho, Z. J. M., Mak, T. M., Marimuthu, K., Vasoo, S., et al. (2020). Imported monkeypox, Singapore. Emerging Infect. Dis. 26, 1826. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.191387

Zhang, Z., Jiang, H., Jiang, S., Dong, T., Wang, X., Wang, Y., et al. (2023). Rapid detection of the monkeypox virus genome and antigen proteins based on surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Materials Interfaces 15, 34419–34426. doi: 10.1021/acsami.3c04285

Keywords: monkeypox virus, mpox, extracellular enveloped virus proteins, intracellular mature virus proteins, profilin-like proteins, detection, biosensor

Citation: Sagdat K, Batyrkhan A and Kanayeva D (2024) Exploring monkeypox virus proteins and rapid detection techniques. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14:1414224. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1414224

Received: 08 April 2024; Accepted: 03 May 2024;

Published: 28 May 2024.

Edited by:

Moises Leon Juarez, Instituto Nacional de Perinatología (INPER), MexicoReviewed by:

Selvin Noé Palacios Rápalo, Center for Research and Advanced Studies (CINVESTAV), MexicoArnaud John Kombe Kombe, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, United States

José M. Reyes-Ruiz, Mexican Social Security Institute, Mexico

Copyright © 2024 Sagdat, Batyrkhan and Kanayeva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Damira Kanayeva, dkanayeva@nu.edu.kz

Kamila Sagdat

Kamila Sagdat Assel Batyrkhan

Assel Batyrkhan Damira Kanayeva

Damira Kanayeva