An Institutional Field of People Living with HIV/AIDS Organizations in Tanzania: Agency, Culture, Dialogue, and Structure

- The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA

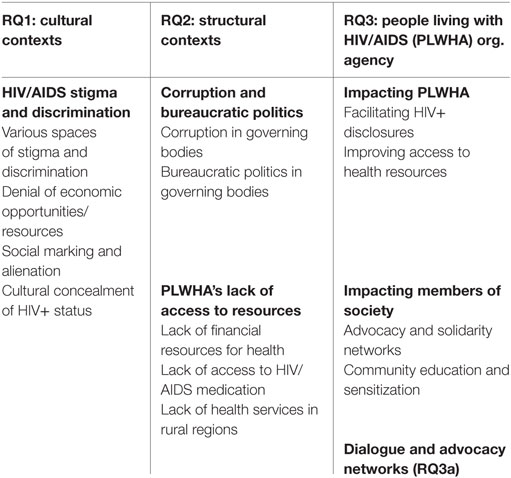

Communication research on public health organizations and people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) have paid insufficient attention to PLWHA organizations. These organizations, constituted and operated by PLWHA, advocate on behalf of PLWHA with more powerful institutions in society and serve as sources of empowerment and support. I drew on the culture-centered approach to health communication and institutional perspectives on health organizations to explore PLWHA organizations in Tanzania, namely, their cultural and structural contexts, agency, and dialogue. Tanzania has 1.5 million PLWHA and a 5.3% adult prevalence rate that ranks it as 12th highest in the world. Through interviews with leaders of 10 PLWHA organizations, I found a cultural context of HIV stigma and discrimination, a structural context consisting of corruption and bureaucratic politics in governing bodies as well as lack of access to resources, agency to impact PLWHA and members of society in a variety of ways, and processes of dialogue within advocacy networks of PLWHA organizations and in network collaborations with the government. I conclude with implications for improving the organizations’ interactions with their structural context and for developing the contribution from the culture-centered approach to health communication on structures as health organizations and systems.

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) organizations are understudied in communication research. PLWHA organizations are non-profit organizations (NPOs) constituted and operated primarily by volunteers who are PLWHA. These organizations emerge out of dissatisfaction with responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic by more powerful societal actors (e.g., government); they pursue the interests of PLWHA by advocating on behalf of PLWHA in their communities and societies (Maguire et al., 2001). It is important to focus on PLWHA organizations because PLWHA in the Global South face continuing problems such as stigma and discrimination (Okoror et al., 2014). Moreover, these organizations have implications for the empowerment, support, and well-being of PLWHA.

Although one body of communication research on health organizations has recognized a variety of public health organizations (e.g., Cooren et al., 2008; Desouza and Dutta, 2008; Zoller, 2010; Cooper and Shumate, 2012) and another body of research on PLWHA has considered various contexts that shape and are shaped by PLWHA (e.g., Hardy et al., 2006; Miller and Rubin, 2007; Iwelunmor et al., 2010; Ho and Robles, 2011), neither body of work has focused much on PLWHA organizations.

The United Nations (UN) estimated that 71% of worldwide HIV infections and 75% of AIDS-related deaths take place in sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2015). These estimates point to the continuing importance of HIV/AIDS research in this context. I drew on the culture-centered approach to health communication (CCA) (Dutta, 2008) and institutional perspectives on health organizations (Lammers et al., 2003) to conduct interviews with 11 PLWHA who were leaders of 10 PLWHA organizations in Tanzania. Findings pointed to the cultural and structural contexts of the organizations, their exercises of agency, and their engagement with processes of dialogue.

Tanzania is a nation of 51 million located in east Africa (Central Intelligence Agency, 2015). Its major languages are Arabic, English, and Swahili (Maxon, 2009). The UN estimated that Tanzania has 1.5 million PLWHA and a 5.3% adult HIV prevalence rate that ranks it the 12th highest in the world (United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2015). I next review the communication literature on public health organizations and PLWHA after which I present the research questions, methods, and findings. I conclude with a discussion and implications.

Literature Review

Communication and Public Health Organizations

Whereas hospitals specialize in the care and treatment of illness, the mandate of public health organizations exceeds that of treatment, oftentimes emphasizing prevention (Zoller, 2010). Because public health organizations operate in and across various sectors, communication research has examined those from the governmental sector (e.g., Barbour et al., 2016), the intergovernmental sector (e.g., Johnny and Mitchell, 2006), and the non-governmental (NGO) sector (e.g., Desouza and Dutta, 2008). In an example encompassing the governmental sector, Murray et al. (2011) explored the partnership between the Catholic Church and Brazil’s Ministry of Health. They found that a series of meetings between the two organizations, starting in 1999, led to the creation of the AIDS Pastoral, a regional Latin-American network for HIV/AIDS care and prevention that combined biomedical and spiritual approaches. In an example incorporating the intergovernmental sector, Atouba and Shumate (2010) examined the network structure among 108 international development organizations. They hypothesized that organizations from the same sector will have a greater chance of forming collaborative relationships. They found this to be true of the intergovernmental sector but not of the NGO sector. As an example from the NPO sector, Murphy (2013) conducted an ethnography of a partnership between a US academic institution and a Kenyan NGO engaged in HIV/AIDS education. The study found that tensions, which arose when the global (e.g., science) met the local (e.g., norms) in the partnership’s interactions, sustained as well as temporarily shifted power relations between a postcolonial global North and South.

Studies of Communication Contexts of PLWHA

People living with HIV/AIDS have been studied in four different contexts: interpersonal, organizational, cultural, and structural. Although these contexts intersect (e.g., the forms of social support PLWHA obtain from health professionals shapes and is shaped by organizational, cultural, and structural contexts), I begin by examining literature emphasizing the interpersonal context. In subsequent sections, I review literature emphasizing organizational, cultural, and structural contexts. Although this review is informative in terms of the considerations and findings of previous communication research on PLWHA, very little attention has been paid to Tanzania. Yet, a majority of the studies that attended to the cultural and structural contexts of PLWHA were based in Africa and, as such, may bear some similarities with the Tanzanian context.

The Interpersonal Contexts of PLWHA

Studies with emphasis on the interpersonal context find PLWHA obtain social support from family, friends, and professionals. From these support networks, PLWHA receive emotional, informational, and instrumental support (e.g., Oetzel et al., 2014). For example, Miller and Rubin (2011) studied Kenyan PLWHA through focus groups and surveys to discover PLWHA motivations for obtaining support from religious leaders. They found participants seeking emotional support more than material support. Studies have also examined PLWHA’s status disclosures such as strategies and target reactions (e.g., Miller and Rubin, 2007; Catona et al., 2015). For example, Caughlin et al. (2009) studied U.S. college students’ reactions to disclosure messages from a hypothetical sibling. They found mostly positive reactions to plain and simple messages.

The Organizational Contexts of PLWHA

Research on the Canadian Treatment Advocate Council (CTAC), a multisectoral collaborative initiative formed in 1996, distinguished among three types of HIV/AIDS NPOs (Maguire et al., 2001, 2004; Maguire and Hardy, 2005; Hardy et al., 2006). One type was HIV/AIDS service organizations. These were NPOs (of paid non-PLWHA employees) that provided health and social services to PLWHA (e.g., counseling, housing). Another type was PLWHA organizations. They arose out of dissatisfaction with response to the epidemic by governments, the medical research establishment, and pharmaceutical companies and had a political agenda to confront these actors on behalf of PLWHA. Another type was AIDS activist organizations. These were radical organizations of volunteers living with HIV/AIDS who engaged in confrontational tactics such as civil disobedience and demonstrations.

Research on HIV/AIDS organizations has mostly focused on HIV/AIDS service organizations (e.g., Dearing et al., 1996; Arya and Lin, 2007; Okoror et al., 2014). For example, Kwait et al. (2001) used network analysis to study different types of collaborative linkages among 30 HIV/AIDS service organizations in Baltimore, MD, USA. They found ad hoc networks based on information-exchange and client-referral linkages having greater densities than formal networks based on written-agreement and joint-program linkages.

The Cultural Contexts of PLWHA

Studies of the cultural contexts of PLWHA have focused on the cultural beliefs, practices, traditions, and values of African communities that shape the experiences of PLWHA. These studies describe a cultural context where families play a central role in the experiences of PLWHA, gender inequality characterizes the experience of female PLWHA, societies place high value on childbearing and parenting, PLWHA encounter extreme levels of stigma and discrimination, and faith and spirituality are considered important resources for coping with HIV/AIDS (e.g., Dageid and Duckert, 2008; Greeff et al., 2008; Iwelunmor et al., 2010; McArthur et al., 2013; Mupenda et al., 2014). For example, Saleem et al. (2016) interviewed 10 female and 11 male PLWHA in Tanzania to study their post-diagnosis childbearing experiences. Although most had not discussed childbearing with a provider before deciding to conceive, they received mixed reactions from various parties. From providers, they received negative reactions such as reprimands for getting pregnant without seeking advice. From partners and the extended family, they received pressure to have children.

The Structural Contexts of PLWHA

Studies of PLWHA rarely attend to their structural contexts. One exception comes from DeJong and Mortagy’s (2013) study of the Sudanese PLWHA Care Association. They recognized structural constraints on the organization’s fight against stigma and discrimination when they acknowledged how difficulty it was for members to engage in association activities requiring personal expenses (e.g., transportation costs) because their HIV-positive status exacerbated their levels of poverty. Another exception comes from Ho and Robles (2011) who interviewed 24 PLWHA to understand their treatment experiences for HIV-related neuropathy. Participants expressed vulnerability from neuropathy symptoms that led to job loss and lack of insurance. They expressed a need for acupuncture and massage therapy (AMT) to counter or complement biomedical pills. Yet, they raised concerns about structural issues such as funding reductions for AMT that threatened its availability and cost.

The Culture-Centered Approach to Health Communication

Culture-centered approaches to health represent departures from mainstream Western theories of health that emphasize individual/psychological determinants of health. They instead emphasize sociocultural factors that shape community health, particularly in non-Western communities (see Singhal, 2003; Airhihenbuwa et al., 2014; Dutta, 2015).

I next review the central ideas of the CCA and the research that has adopted it. The CCA is a framework that attends to the various contexts found in the PLWHA literature (particularly organizational, cultural, and structural). Inspired by subaltern and postcolonial studies, the CCA examines the interplay of agency, culture, dialogue, and structure in the health of the marginalized in postcolonial contexts (Dutta, 2008). It prioritizes inquiry that challenges the dominant architecture of Western knowledge/illness models and contributes cultural constructions of health by the marginalized (e.g., Sastry, 2016). Structures form the economic bases of the material and social components of society. Although conceived primarily as constraining and painful (Dutta, 2007), structures constrain and enable access to resources (Dutta, 2015). Structures are also less-encompassing health systems such as administrative arrangements, clinics, and hospitals (Dutta, 2008). Culture is the dynamic web of beliefs, values, and meanings that generate community norms and traditions. Agency challenges notions of the subaltern as passive objects to be acted upon and foregrounds their knowledgeability, networks of solidarity, and resistances (Dutta, 2015). Dialogue points to engagement with community voices that facilitates indigenous constructions of health and the participation of members in articulating health problems and solutions.

Studies have drawn on the CCA to study marginalized groups coping with or vulnerable to HIV/AIDS (Acharya and Dutta, 2012; de Souza, 2012; Basu et al., 2016). For example, Muturi and Mwangi (2011) conducted focus groups with older Kenyan adults to provide suggestions for HIV prevention. They found recommendations for communicators (e.g., religious leaders), contexts (e.g., public meetings), and programs (e.g., mass HIV testing).

Although the interpersonal context of PLWHA (e.g., family communication) intersects with the other three contexts, I draw on the culture-centered approach to health communication to engage primarily in inquiry of the organizational, cultural, and structural contexts of PLWHA.

Institutional Perspectives on Health Organizations

Institutional perspectives are missing from studies of PLWHA organizations. These perspectives transcend a focus on any one organization to that of a field of organizations and emphasize similar properties of organizations explained by a shared environment (e.g., Seo and Creed, 2002; Scott, 2014). Lammers et al. (2003) applied tenets from institutional perspectives to health organizations such as “hospitals, health maintenance organizations, or health advocacy groups” (p. 320). They outlined institutional tenets such as (a) organizations emerge as means to achieve culturally valued ends, (b) the external rather than the internal environment provides the logic of organizational systems, (c) society is characterized by “pervasive beliefs about appropriate conduct that are idiosyncratic to organizations in a particular sector” (p. 321), and (d) isomorphic processes of organizational fields contribute to uniformity across organizations.

Communication research on public health organizations and PLWHA have rarely acknowledged PLWHA organizations. More importantly, they have yet to study a field or set of these organizations and they have rarely considered the structural contexts of PLWHA. Research that attends to these issues can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the contexts that shape and are shaped by these understudied organizations and the ways in which they act in concert and/or similarly. Accordingly, I posed the following research questions—animated by the central CCA concepts of agency, culture, dialogue, and structure—of a field of organizations constituted and operated by the marginalized (PLWHA) in the postcolonial context of Tanzania:

RQ1: What characterizes the cultural context of a field of PLWHA organizations?

RQ2: What characterizes the structural context of a field of PLWHA organizations?

RQ3: How are PLWHA organizations and their members exercising agency?

RQ3a: How, if at all, are PLWHA organizations engaging in dialogue?

Materials and Methods

Procedures

This field study received authorization from the office of the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology and my university’s Institutional Review Board. Upon approvals, I recruited leaders of HIV/AIDS NGOs in Dar es Salaam (DSM) for interviews. DSM, a city of five million, is the most populated in Tanzania (Central Intelligence Agency, 2015). Available data on DSM indicate an adult HIV/AIDS prevalence rate of 7%; this includes a 31% rate for female commercial sex workers, 22% for men who have sex with men, and 16% for intravenous drug users (Results from the 2011–12 Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey: HIV Fact Sheet by Region, 2015). I recruited participants through site visits to NGO offices; phone calls, text messages, and e-mails; and snowball sampling. I scheduled private interviews with participants in office spaces belonging to their NGO. I began by having participants complete informed consent to research and demographics forms.1 The interviews were semistructured, and I conducted them in English.2 I also audio-recorded the interviews and took notes. Upon completion, I compensated each participant $15 in Tanzanian shillings for their time and asked them for contacts who occupied leadership positions in Tanzanian HIV/AIDS NGOs.

Data Reduction

For the study reported here, I focused on 11 interviews from a larger study involving 36 interviews with Tanzanian leaders of HIV/AIDS NGOs. The larger study consisted of interviews conducted in Tanzania over a 3-month period (where I also enrolled in a short course in Swahili and visited places such as Arusha, Bagamoyo, and Kigoma) and Skype interviews conducted upon my return to the US. The 11 interviews were of leaders of 10 PLWHA organizations. I identified them as such through status disclosures, interview content, and NGO names. I conducted nine of these interviews in person and two over Skype.

Participants and PLWHA Organizations

All 11 participants were natives of Tanzania. They held titles such as “Executive Director” and “Executive Chairperson.” Eight were males and three were females. They averaged 44.36 years of age (ranging from 24–62 years). Seven had the equivalent of high school diplomas, two had bachelor’s degrees, one had a Master’s degree, and one reported “other.” They averaged 8.36 years of employment with their current NGO (ranging from 2 to 21 years).

All 10 NGOs were based in DSM. On average, they had existed for 12.00 years (range: 6–21 years). Seven reported nationwide operations and three reported community-based operations. Six described their organization as networks composed of several PLWHA organizations. Two described their networks as community based and the other four described theirs as national.

The 11 interviews averaged 53.05 min (ranging from 31.31 to 77.52 min). To enhance credibility (Lincoln and Guba, 1985), I employed a transcriptionist of east African descent who comfortably understood participants’ accents. Transcriptions resulted in approximately 182 single-spaced pages of text. Moreover, I improved the accuracy of the transcriptions with a team of graduate students, one of whom, born and raised in Kenya, was fluent in Swahili.

Data Analysis

To address the research questions, I drew on the constant comparative method (CCM) (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Corbin and Strauss, 2015). In building from a comparative analysis of units to broader themes, the CCM consists of identifying units, open coding, and axial coding.3

I began by deciding on the most basic unit for data analysis (Miles et al., 2014). Although analysts can choose among several units that vary in size and abstraction, I chose semantic relationships or units of meaning (Spradley, 1979) because they can be specified in direct relevance to research questions, they are not restricted to a specific length, and they encourage the analyst to engage with latent content (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005).

I identified units separately for each RQ. For RQ1, I searched for “X as an element of culture encompassing PLWHA organizations.” In line with a directed approach (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005), I drew guidance from literature highlighting African cultural contexts of PLWHA (e.g., Saleem et al., 2016). I posed questions of the data such as “What beliefs, meanings, and values encompass PLWHA organizations?” For RQ2, I searched the transcripts for “X as an aspect of structure encompassing PLWHA organizations.” Also in line with a directed approach, I drew guidance from CCA research on structures (e.g., Sastry, 2016). I posed questions such as “What are the broader socio-economic constraints on PLWHA organizations?” For RQ3, I searched for “X as PLWHA organization/member agency.” Here, I drew guidance from CCA research emphasizing agency (e.g., Basu and Dutta, 2008). I posed questions such as “How are PLWHA organizations/members interacting with culture and structure?” For RQ3a, I probed data that addressed RQ3 for the communication processes of dialogue (Dutta, 2008).

I performed open coding separately for each RQ (Corbin and Strauss, 2015). Open coding involves constant comparison between units, deciding on labels (or codes) for new units, and identifying and labeling emergent themes. I sorted units receiving identical or similar codes into themes and labeled them. I observed the practice of coding the data in every way (Glaser, 1978). Stated differently—I gave a unit multiple codes when it seemed appropriate.

After arriving at a set of themes for each RQ, I performed axial coding by identifying relationships among themes, integrating them into categories, and deciding on labels. For RQ1 on culture, I integrated four themes into one category. For RQ2 on structure, I collapsed five themes into two categories, and for RQ3 on agency, I merged four themes into two categories.

Findings

The Cultural Contexts of PLWHA Organizations

HIV/AIDS Stigma and Discrimination

For RQ1, I found four themes for the category on HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination: the various spaces of stigma and discrimination, the denial of economic opportunities and material resources, social marking and alienation, and cultural concealment of HIV-positive status.

The Various Spaces of Stigma and Discrimination

Participants highlighted the pervasive nature of HIV stigma and discrimination by reporting on occurrences in diverse spaces such as families, government offices, religious organizations, schools, and workplaces. For example, Rehema,4 a female executive chairperson, spoke of violence that women living with HIV suffered from their husbands who were also HIV positive, “Men were not able to go to the clinic, so they were using their wives’ drugs. That’s why we are fighting against gender violence, drug sharing, because if you don’t give the drugs to your husband, your husband can beat you.” Rehema broached the problem of drug sharing. As a result of stigma associated with obtaining HIV medication in public, men shared their wives’ HIV medication; this practice oftentimes resulted in domestic violence when wives refused to share. In addition to the families, Imani, a male chairperson, spoke of stigma and discrimination in workplaces, “if you are found to be positive while in the job, they sometimes create an unconducive environment so that you can leave.” In contrast, Juma, a male executive director, recounted his challenges with government:

We struggled for around one year because [government] did not get our vision. When we talk about we are positive living, we need to be registered, they said, “why do you ask to be registered? Because you are going to be buried very soon. Why should we give you registration because you are going to die?” It was a terrible environment.

Juma shared the resistance he faced from government officials while trying to register his PLWHA organization. Because the officials regarded HIV/AIDS as a death sentence (see Iwelunmor and Airhihenbuwa, 2012), they failed to understand the need for the organization.

Denial of Economic Opportunities and Material Resources

In addition to diverse spaces of stigma and discrimination, I found denial of economic opportunities and material resources as another theme. PLWHA were denied economic opportunities such as businesses and jobs. Imani spoke of this denial, “In communities, some people who are entrepreneurs, who have small businesses. They are making fish or selling bananas, foodstuffs. If they [potential clients] know you are infected, they don’t come to buy at your place simply because you are infected.” Neema, a female executive secretary, made the following contribution, “The problem is that most people lose their jobs if they know that they are HIV-positive.” In addition to denial of economic opportunities, PLWHA were also denied material resources such as property. Omary, a male general secretary, gave an example from the family context, “When someone in the family, maybe the father of the family passes away, the other family members discriminate against the mother and children. Sometimes they take all the wealth that the father had left.” While talking about the withholding of financial resources for PLWHA from the government, Biko, a male program coordinator, made the following comment, “Because of stigma and discrimination, we were discriminated, that’s why we had to fight that we belong to this nation and we are entitled to whatever is there for us. So to people with a discriminative mind, it’s war.”

Social Marking and Alienation

In addition to denial of economic opportunities and material resources, I also found the theme of social marking and alienation. This theme characterized the social isolation and marginalization of PLWHA. For example, participants described situations where HIV-positive children attending schools were being marked. Omary explained, “Because it happened that one of the primary schools in this country, they were forcing to put red ribbons on children with HIV.” This type of marking, in turn, led to the social alienation and isolation of PLWHA. Juma, in assessing the social treatment of PLWHA, spoke of this alienation, “It is improving over time but some people do not want to see or hear from people who are already infected.” Imani spoke also of this alienation and isolation, but by organizations in the community, “Because there are some organizations, because of stigma and discrimination in which the stigma index still is very high, of which if concerned with [PLWHA], especially young people, they are not very much interested in working with you.”

Cultural Concealment of HIV-Positive Status

In addition to social marking and alienation, I found a theme on cultural concealment of HIV-positive status. Because of the prevalence of HIV stigma and discrimination and cultural taboos around sex-related topics, Tanzanians were largely silent on HIV-related topics such as HIV-positive status. Neema shared the following about parents withholding the HIV-positive status of their children, “What can I say? If the children are HIV+, the parents know but they do not tell their children that they are positive.” Remmy, a male monitoring and evaluation officer, spoke of how Tanzanian youth initially concealed their HIV-positive status, “we have been working with young people living with HIV/AIDS for quite a long time now. In the earlier stages, it was not easy. Most of this people were not open and they used to hide their status.” Jakaya, another male monitoring and evaluation officer, identified his PLWHA organization’s clients as those who had difficulty disclosing their HIV-positive status to family members: “These are people who share the home and don’t have education about HIV/AIDS. And they are worried of coming in front to say themselves that they are suffering.” This theme pointed to a culture of silence and concealment around a positive HIV status. For a summary of findings, see Table 1.

The Structural Contexts of PLWHA Organizations

Corruption and Bureaucratic Politics

For RQ2, I present the “corruption and bureaucratic politics” category before the “lack of access to health resources” category.

Corruption in Governing Bodies

This category centered on the subtle corruption of government officials and the political and opaque practices of the government and the national council5 surrounding the funding of HIV programs. PLWHA organizations were required to officially register their existence with the government and to obtain permission to conduct programs. In their interactions with the government, participants reported corrupt practices where officials subtly sought to extract bribes. Jakaya described his experience as follows, “When you go asking for permission for a bonanza, the first idea that goes in their mind is that you have funds. They tend to delay or to make things hard in order for you to at least give them something.” Believing the NGOs had funding to implement the HIV programs for which they were seeking permits, government officials would create unnecessary delays and hurdles in order to receive bribes. Oresto, a male chief executive officer, described the government’s unrealistic expectations of his PLWHA organization’s finances: “Working with the government as a key partner, well, there has been too much expectations. The government was expecting so much from the organization. Given the internal problems like financing, the organization was not able to meet the expectations.”

Bureaucratic Politics in Governing Bodies

Participants further described the funding for HIV programs by the government and the national council as corrupt and lacking transparency. Biko pointed to corrupt officials who refused to release funds even after being authorized to do so: “The officials in certain positions may create problems when releasing funds. They just sit on the requests. Even if they have been authorized, somebody [government official] can decide to do what they want to do.” Participants also complained about the lack of transparency in the decision-making processes of governing bodies on the funding of HIV programs6:

Jakaya: The experience has been good so far because we have collaborated [with the national council] in implementing a number of projects. It has also helped our organization and others secure funds for implementing activities for reaching people living with HIV/AIDS although it also has its own politics and stuff like that.

I: What do you mean by politics?

Jakaya: Sometimes things are not as smooth or as easy as they are expected to be. There are many opportunities but due to some politics, some get funds while some do not. It is hard to know the criteria for this one to get it and this one not.

Participants pointed to the subtle corruption of government officials and the opaque decision-making processes of the government and the national council in funding HIV programs.

Lack of Access to Health Resources

For RQ2, I also found the category of lack of access to health resources. It consisted of the three themes of “lack of financial resources for health,” “lack of access to HIV/AIDS medication,” and “lack of health services in rural regions.”

Lack of Financial Resources for Health

Participants discussed the lack of financial resources for health for individual PLWHA, the government, the national council, and their own NGOs. Omary discussed the government’s lack of financial resources as compromising its ability to deliver on the promise of free HIV medication: “They say that this treatment is provided by the government for free but when you go to ask it, they say that it depends on the cash the government has. If there is no cash, there is no service. It disturbs people.” Biko spoke of the diversion of funds meant for PLWHA:

There are some funds which are supposed to go to people. For instance, to purchase medicine for opportunistic diseases, but in most cases are not available. Even some funds are meant for nutrition to people already diagnosed with HIV and TB that are diverted to others.

Rehema spoke of her NGO’s lack of financial resources, “Our organization is for women living with HIV, people living with HIV. We have got many challenges here because nowadays, HIV funds, pockets have already nothing.” Pengo, a male executive chairperson, spoke of the lack of financial resources for individual PLWHA. He made the point that PLWHA would stop taking HIV medication if they could not afford food:

Most of the people have been sick for a long time; they have sold their property. Now they are poor. So they can’t access even three meals a day; most of them are so poor. So they are stopping taking drugs because they don’t have food.

This theme covered the lack of financial resources for health at various levels: individual PLWHA, the PLWHA organizations, the national council, and the government.

Lack of Access to HIV/AIDS Medication

In addition to lack of financial resources for health, participants reported difficult access to antiretroviral medication (ARV). Oresto connected the lack of access to medication to the lack of government resources for health:

We see that donors are reducing amount of financing to HIV/AIDS. This has created a burden for the government. It has actually threatened those who are being put on treatment because they are not certain whether this is going to be available. Because once you are on treatment, it’s for life. You cannot opt not to take it today, saying that you may re-start in the next month. That is all about defaulting. It is about impacting on adherence to treatment as well.

Pengo spoke of the high cost of ARVs and the effort to make it more affordable, “The drug was high cost so we try to force to reduce the price of ARV drugs and then to advocate with the pharmaceutical companies in South Africa and East Africa, and xxxx and other organizations.” Rehema spoke on lack of access to authentic ARVs: “Two years ago there was a problem of getting ARVs. Then they discussed in parliament, but up to date, there is no serious action taken against people who made that bad thing of fake ARVs.” Omary spoke of a drug shortage at dispensaries that led to receiving incomplete doses:

Most people are sick and the ability to get the right dose is difficult. I don’t know but, for example, here in town, we manage to access drugs, but not all the time. Maybe you are supposed to be given one month dose, sometimes you are provided with half-a-month. When they go, there is a shortage of drugs.

Despite government policy to provide free ARVs to PLWHA, several reported difficult access.

Lack of Health Services in Rural Regions of Tanzania

In addition to lack of financial resources for health and lack of access to medication, participants spoke of difficult access to health services for PLWHA living in rural regions. Biko said, “We know our country is very vast and some areas are very remote. There are villages which since independence they have never seen a government official. Those people are left alone dying there. If they get the disease, no assistance is going on.” Omary also spoke on this theme as follows, “Another area is that in the rural places, infrastructure is not good. It is not easy for the ministry of health to make sure that medicine is well supplied in the HIV-infected rural areas. Some of them are missing those areas.” Pengo described the types of challenges that PLWHA in rural areas face:

HIV is a problem because of affordability and accessibility of the drugs because most of the care treatment centers are located at cities or district headquarters. So clients are coming from the villages where it’s too far to access the treatment. So accessing the treatment depends on when he gets some money or when he borrows money from someone else, which will enable him or her to travel from point A to point B to access the drug. So that can cause problems for the one taking drugs. So that’s a very big problem.

Pengo pointed to distance and money as treatment barriers faced by PLWHA residing in rural regions. For a summary of the findings, see Table 1.

Agency of PLWHA Organizations

Impacting PLWHA

For RQ3, I first present the categories of “Impacting PLWHA” and “Impacting members of Tanzanian society.” I then address RQ3a by presenting the theme “advocacy networks and dialogue.” For “Impacting PLWHA,” I next present the themes “facilitating HIV-positive status disclosures” and “improving access to health resources.”

Facilitating HIV-Positive Status Disclosures

HIV stigma and discrimination largely led to the silencing of PLWHA. Neema spoke of the detrimental effects of stigma and discrimination that she hoped to help PLWHA overcome, “I am HIV+. I can encourage other young people who are positive, but they discriminate themselves. They are afraid to speak and open up their status.” As a result of the silencing of PLWHA, the PLWHA organizations encouraged people to disclose their HIV-positive status. Imani spoke on this when he stated “since inception this organization was started to advocate for young people to come up and disclose their status so that they can advocate for stigma and discrimination as well as encourage others to live positively.” Through HIV-positive disclosures, PLWHA resisted the cultural norms and practices that silenced them, they overcame any fears they had of others becoming aware of their status, and they became examples for others to follow. An initiative by which some organizations facilitated status disclosures (particularly those of youth) was youth clubs.

PLWHA organizations dedicated to youth implemented youth clubs to educate PLWHA (e.g., sexual reproductive rights) and to create a discursive space where they could open up. As Jakaya put it, “we have tried to create those clubs for young people so that they can be more easily open and talk about their challenges and things like that.” Participants consulted with leaders of institutions that served PLWHA (e.g., clinics, hospitals, and schools) to form youth clubs within those institutions. The clubs relied on activities that appealed to youth. For example, in response to my interview question on the best way to reach Tanzanian youth, Neema expanded on the activities of youth clubs, “The best way to reach youth is through edu-entertainment. When we go to work with young people, most of the young people, they like music. That is why I said edu-entertainment because they like music, drama, and theater.”

Improving Members’ Access to Health Resources

In addition to facilitating status disclosures, the organizations also worked to improve members’ access to health resources. For example, Pengo described his organization’s effort to reduce the cost of HIV medication:

The drug was very high costed so we try to force to reduce the price of ARV drugs and then to advocate with the pharmaceutical companies in South Africa and east Africa. We have been advocating in South Africa. We have been advocating in Kenya to reduce the price. In the end, we find that we win that and the cost of the drug was dropped and now people are issuing the drugs in our country.

Jakaya too described his NGO’s efforts at improving PLWHA access to health resources, “We advocate for the rights of [PLWHA] by ensuring they have access to quality health services or education services. We also sometimes help organize young [PLWHA] with economic opportunities, entrepreneurship.” Juma also spoke of assistance to orphans living in rural regions, “We are using our organization to help people who are living in villages outside of Dar es Salaam. We call remote areas. We go there with uniforms, scholastic materials, we supply them.” By recognizing areas of difficult access to health resources, the organizations performed advocacy work, empowered PLWHA to obtain resources, and/or directly provided resources.

Impacting Members of Tanzanian Society

For RQ3, I found the category of “impacting members of Tanzanian society.” This category included the themes of “advocacy and solidarity networks” and “community education and sensitization.”

Advocacy and Solidarity Networks

PLWHA organizations formed networks to involve PLWHA at the grassroots and to leverage their collective influence in advocacy with the government. Pengo, a network leader, described his network as follows, “Small small organizations in the districts are coming together and forming a network.” Biko, another network leader, described his three-district network, “It has only three members, three networks. But every network has its own members. For instance, Kinondoni [one of Dar es Salaam’s three municipalities] alone has 42 small NGOs which are members of this network.”

Participants pointed to an association between the prevalence of stigma and discrimination in a community and the development and size of networks. For example, Biko stated, “In the past we were discriminated, segregated, and stigma was high. So that was one of the reasons we [PLWHA organizations] decided to come together.” In another example, Pengo stated, “In other districts, the level of stigma is very high. For other districts, the level of stigma is very low. So we can have a big number of organizations within a district. But for a district where the stigma is very high, it is a very little number.”

The networks challenged stigma and discrimination at grassroots and national levels. A national-level example comes from a network’s involvement in shaping policy on marking HIV-positive schoolchildren. Oresto, another network leader, spoke to this when he said “In the past, we actually wanted to influence some policies, especially the policy that was discriminating schoolchildren who were living with HIV/AIDS, because they were being labeled.”

Through advocacy to the government, the networks also sought to improve PLWHA’s access to health resources. Pengo articulated his network’s vision as such, “The vision of the organizations is to see that all PLWHA are not discriminated in that they are accessing the quality treatment as per the universal access.” Biko spoke of his network’s “fight” for the government to prioritize funding for HIV/AIDS:

You know some leaders think that HIV/AIDS is not a priority. They have their own priorities. Whatever it is that’s a priority to him, he would like to channel the funds to those areas. And they leave alone [PLWHA]. That is why the council and organizations have stood together and fought the war.

Rehema, another network leader, also spoke of working with the government to improve access to health resources for PLWHA, “Because when you are working with [PLWHA], you sometimes need support from government. So in order for government to know what exactly you need, you must sit together and see how you can solve the issue that is needed by [PLWHA].” She went on to give examples of PLWHA issues her network had broached: more ARVs, better nutrition, better health facilities, and integrated health care.

Community Education and Sensitization

In addition to networks, the organizations also combatted HIV stigma and discrimination by educating communities. Juma shared, “There was a misunderstanding of information about HIV/AIDS. There was a misunderstanding about deaths. That’s why we came together and we decided to form the organization first to combat stigma and discrimination and to advocate for human rights as a people.” He later went on to describe his NGOs’ efforts at combatting stigma and discrimination, “Education and sensitization. We educate by using TVs. We educate as PLWHA by radio.” Another participant, Omary, stated, “We set up activities that involve the police force to make people aware that discrimination is illegal.” Remmy, on the other hand, described a diffusion process whereby those educated by his NGO would educate others, “My NGO deals with those people by providing education to other people who have the ability themselves to come out and say they are suffering from HIV/AIDS and go and give the education to other people.” The organizations drew on various channels to educate people about HIV and to combat stigma and discrimination.

In addition to educating communities, participants described efforts that targeted the clients and members of different organizations. As Juma put it, “We started slowly with staff, doctors, nurses, patients. They requested us to go to them to train them at their workplaces, at their markets, at their small businesses, and at their fisheries. Everywhere.” Similarly, Jakaya stated, “We have been working with care and treatment centers. We have also been working with schools, teachers in schools, trying to improve the environment where [PLWHA] can live just like any other human being without being discriminated or stigmatized.”

Dialogue and Advocacy Networks

For RQ3a, I found organizations engaged in dialogue within organizational networks and in network collaborations with governing bodies. Rehema described her network as follows, “We are in 20 regions. In these regions, we have women groups and other district organizations of women living with HIV. So these are our members.” She then described dialogic practices within the all-female network:

When we do something for national interest, we include them, we plan together, and then we implement together. We discuss issues within our organization, how to improve the quality of lives of women living with HIV. So when we meet, we discuss how we can access funds, how we can make their lives better, how women living with HIV can be involved with issues around them, and also we discuss advocacy issues in order to improve our lives.

By involving female PLWHA in decision-making, planning, and implementation, the advocacy network engaged its members in dialogue. Furthermore, other leaders of network organizations also described their collaborations with governing bodies as involving dialogue. For example, after claiming his organization was the first in Tanzania to import antiretroviral drugs from the global north, Juma stated, “It took, in our country, 5 years for the government to agree to sit with us and develop a national treatment and care plan.” This contribution implies a dialogic process, albeit delayed, where a national plan to provide HIV medication was created in partnership with the government. Biko also described a dialogic process taking place with government, “now with any intervention being done in the municipal, we are consulted and we give our consent or we participate. So in everything relating to HIV done by any council or government, we do participate. In the past, that was a dream.” See Table 1 for a summary of the study’s findings.

Discussion

Through in-depth interviews with leaders of 10 PLWHA NGO organizations in Tanzania, I find a cultural context of HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination (e.g., social marking and alienation), structural contexts consisting both of corruption and bureaucratic politics in governing bodies and lack of access to health resources (e.g., ARVs), organizational agency to impact PLWHA (e.g., improving access to health resources) and members of Tanzanian society (e.g., through advocacy networks of organizations), and dialogic processes in advocacy networks and in network collaborations with the Tanzanian government (see Table 1).

Several of the findings are consistent with those of previous research on PLWHA. First, my finding of a Tanzanian cultural context of HIV stigma and discrimination is consistent with findings of a high prevalence of HIV stigma and discrimination in African communities (e.g., Petros et al., 2006; Airhihenbuwa et al., 2009; Okoror et al., 2014). For example, drawing on a focus group study of women living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa to explore the experience of stigma in healthcare settings, Okoror et al. (2014) found stigmatizing practices such as specific file colors being used for HIV-positive patients and sections of the healthcare setting reserved only for PLWHA. Although Okoror et al. (2014) focused on stigma in a healthcare setting, this study’s participants reported stigma and discrimination in diverse spaces (e.g., families, workplaces). Second, my finding of a structural context of lack of health resources is also consistent with previous research on PLWHA (e.g., Ho and Robles, 2011; DeJong and Mortagy, 2013). For example, drawing on interviews with personnel of HIV/AIDS NGOs, Kiley and Hovorka (2006) researched the role of NGOs in Botswanna’s national response to HIV/AIDS. They found the NGOs constrained by a lack of financial and human resources. Although this study also found the NGOs suffering from lack of resources, the study found the problem of lack of access to be particularly acute for PLWHA in rural regions of Tanzania. Third, my finding of PLWHA organizations working to improve access to health resources (e.g., cost of treatment) is consistent with previous findings from research on PLWHA organizations (e.g., Maguire et al., 2001; DeJong and Mortagy, 2013). For example, research on the CTAC found PLWHA organizations working to secure affordable and effective treatment for PLWHA (e.g., Hardy et al., 2006). In light of the advent of ARVs and problems of its access in Tanzania (e.g., authenticity, shortages), the PLWHA organizations sought to improve their members’ consistent access to quality ARVs.

In addition to reinforcing previous research, these findings make new contributions. Whereas previous research that attended to the structural contexts of PLWHA focused on the experiences of PLWHA within these contexts, my finding of corruption and bureaucratic politics in governing bodies contributes the very processes that create the structural contexts. For example, in previous research, DeJong and Mortagy (2013) found that the poverty of members of a PLWHA organization, which made it difficult for them to afford such things as transportation fees, limited their engagement with the organization. In another example, Ho and Robles (2011) found PLWHA expressing vulnerability from lack of insurance and fears about the future availability and cost of AMT. Although insightful, these findings describe the experiences of PLWHA within particular structural contexts. My finding of corruption and bureaucratic politics where, for example, governmental officials created unnecessary delays and hurdles to extract bribes and refused to release funds allocated to PLWHA organizations begins to shed light on some of the very processes that create the structural contexts and the economic vulnerabilities experienced by PLWHA in Tanzania.

My findings also contribute new insights into the initiatives and partnerships of PLWHA organizations. To create discursive spaces that encourage HIV-positive disclosures and resist the cultural silence created by HIV stigma and discrimination, PLWHA organizations formed youth clubs. By partnering with organizations that catered to PLWHA such as clinics, hospitals, and schools, the PLWHA organizations leveraged their resources (e.g., programs, volunteers) to reach and impact young PLWHA that were clients of other organizations in the community.

My finding of networks of PLWHA organizations also makes new contributions to the literature. Although Maguire et al. (2001) were one of the first to introduce us to PLWHA organizations, the geographical, historical, structural, and cultural contexts of their PLWHA organizations differ markedly from those of this study. Furthermore, whereas Maguire et al.’s study focused on cross-sector partnerships, I found networks composed exclusively of NGOs. These networks embody important principles of institutional perspectives on health organizations in that they are constituted by multiple health organizations from the same sector (Lammers et al., 2003). The field mobilizes PLWHA organizations at the grassroots and draws upon their collective influence to advocate, at local and national levels, on behalf of Tanzanian PLWHA. Despite similarities in purpose, sector, and type of health organization, the networks also differ. While some are district networks, others span the whole nation, continental regions, and even the globe. Those in Tanzania also form around salient PLWHA identities (e.g., journalists living with HIV/AIDS, women living with HIV/AIDS, young PLWHA, 50+), suggestive of an underlying peer-education model where peers provide social influence and social support. An important contribution to culture-centered research is the principles of dialogue upon which the networks are formed and through which they operate. The networks unify the voices of PLWHA, facilitate their involvement in issues affecting them, and elevate their collective voice in decision-making forums (e.g., government) at local, national, and international levels.

These findings have implications for practice. Although the organizations are addressing stigma and discrimination and PLWHA’s lack of access to health resources, additional steps can be taken to address corruption and bureaucratic politics. In subtly extracting bribes and refusing to fund HIV programs, government and council officials are making erroneous assumptions about the urgency of the epidemic and the preexisting funds available to the NGOs. These assumptions can be countered and modified through ongoing dialogue between the NGOs and governing bodies—dialogue based on more robust partnerships on HIV initiatives, greater transparency on NGO finances, and mutual recognition of urgency. In the context of ongoing dialogue, erroneous assumptions can be modified, officials may lessen their expectations for financial gain, and they may more readily release funds allocated for HIV programs.

The findings have further implications for the CCA. Although the CCA conceives of “structures” as the economic bases of societies (Dutta, 2007) and as less-encompassing health organizations/systems (see Dutta, 2008), CCA research has emphasized the former. In light of this study’s focus on PLWHA organizations and findings on governing bodies and advocacy networks, these less-encompassing structures can be more fully theorized from a CCA perspective. They can be conceived as economic actors that are enabled and constrained by access to resources, as cultural systems characterized by particular health beliefs and values, and as collectives that have the ability to engage in processes of dialogue as they interact in particular ways with other actors in their cultural and structural contexts.

Limitations and Future Research

The study has a few limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, although the sample of 11 PLWHA is a small one, it represents leaders of 10 different PLWHA organizations and the reported themes have substantive grounding in the interviews. To generate more knowledge in particular of PLWHA advocacy networks, future studies can be based on a larger sample of network leaders. As these networks operate across sub-Saharan Africa and the world, future research can focus on transnational networks of PLWHA. Second, the study is limited in its exclusive focus on NGO leaders. Although they provide a valuable perspective, more insight (particularly into cultural and structural contexts) may be gained from samples that include rank and file members of PLWHA organizations. Third, the study is limited in including only PLWHA organizations based in the urban city of DSM. In light of the finding of difficult PLWHA access to health services in rural Tanzania, future research on PLWHA organizations can focus on those based and/or operating in rural communities of Tanzania.

Conclusion

The study draws on the CCA and institutional perspectives on health organizations to explore the cultural and structural contexts of PLWHA organizations, organizational agency, and dialogic processes. Although the PLWHA organizations face several problems in their cultural and structural contexts (e.g., stigma and discrimination, corruption), their formation of advocacy networks and their engagement of dialogic processes within and without these networks represent both theoretically interesting and indigenous communication processes for arriving at solutions that impact both PLWHA and policies affecting PLWHA in Tanzania.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I dedicate this article to the memory of my father and mentor Johnson Oluwole Olufowote (PhD, Plant Breeding, Cornell University, 1994) who slept in 2016. The study received funding from a University of Oklahoma College of Arts & Sciences Junior Faculty Summer Fellowship. I acknowledge invaluable assistance from the following with gaining authorization and collecting data in Tanzania: Dr. Herbert F. Makoye with the University of Dar es Salaam, Mrs. Yusta Mganga with the MS-Training Centre for Development Cooperation, Mr. Mupape Mukuli, and Dr. Michael J. Soreghan with the University of Oklahoma. I thank the following graduate students who assisted me with transcribing and managing the interview data: Johnson Aranda, Danni Liao, and Emma Wang. I also thank Dr. Michael W. Kramer with the University of Oklahoma for providing feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by a junior faculty summer fellowship and additional research funds from the author’s university.

Footnotes

- ^Through the demographics questionnaire, I measured variables such as age, education, gender, number of years employed with current NGO, place of birth, religion, and NGO jurisdiction.

- ^Sample questions included, “How, if at all, is HIV/AIDS in Tanzania a crisis?” “Please describe the work your organization does in the area of HIV/AIDS.” “Please describe your current role or duties.” “How does culture in Tanzania promote the spread of HIV/AIDS?” How does culture in Tanzania prevent HIV/AIDS?”

- ^By excluding the selective coding step of grounded theory (e.g., Glaser and Strauss, 1967), the CCM can be used to strike a balance between (a) openness to qualitative data and (b) the guiding lens of a preexisting theory.

- ^I use Tanzanian pseudonyms to represent contributions from the study’s participants.

- ^A non-profit governance structure for PLWHA organizations that represented PLWHA in government policy-making forums.

- ^In the following excerpt, “I” refers to interviewer.

References

Acharya, L., and Dutta, M. J. (2012). Deconstructing the portrayals of HIV/AIDS among campaign planners targeting tribal populations in Koraput, India: a culture-centered interrogation. Health Commun. 27, 629–640. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.622738

Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Ford, C. L., and Iwelunmor, J. I. (2014). Why culture matters in health interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Educ. Behav. 41, 78–84. doi:10.1177/1090198113487199

Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Okoror, T., Shefer, T., Brown, D., Iwelunmor, J., Smith, E., et al. (2009). Stigma, culture, and HIV and AIDS in the western cape, South Africa: an application of the PEN-3 cultural model for community-based research. J. Black Psychol. 35, 407–432. doi:10.1177/0095798408329941

Arya, B., and Lin, Z. (2007). Understanding collaboration outcomes from an extended resource-based view perspective: the roles of organizational characteristics, partner attributes, and network structures. J. Manage. 33, 697–723. doi:10.1177/0149206307305561

Atouba, Y., and Shumate, M. (2010). Interorganizational networking patterns among development organizations. J. Commun. 60, 293–317. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01483.x

Barbour, J. B., Doshi, M. J., and Hernandez, L. H. (2016). Telling global public health stories: narrative message design for issues management. Communic. Res. 43, 810–843. doi:10.1177/0093650215579224

Basu, A., Dillon, P. J., and Romero-Daza, N. (2016). Understanding culture and its influence on HIV/AIDS-related communication among minority men who have sex with men. Health Commun. 31, 1367–1374. doi:10.1080/10410236.2015.1072884

Basu, A., and Dutta, M. J. (2008). Participatory change in a campaign led by sex workers: connecting resistance to action-oriented agency. Qual. Health Res. 18, 106–119. doi:10.1177/1049732307309373

Catona, D., Greene, K., and Magsamen-Conrad, K. (2015). Perceived benefits and drawbacks of disclosure practice: an analysis of PLWHAs’ strategies for disclosing HIV status. J. Health Commun. 20, 1294–1301. doi:10.1080/10810730.2015.1018640

Caughlin, J. P., Bute, J. J., Donovan-Kicken, E., Kosenko, K. A., Ramey, M. E., and Brashers, D. E. (2009). Do message features influence reactions to HIV disclosures? A multiple-goals perspective. Health Commun. 24, 270–283. doi:10.1080/10410230902806070

Central Intelligence Agency. (2015). The World Factbook: Tanzania. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tz.html

Cooper, K. R., and Shumate, M. (2012). Interorganizational collaboration explored through the bona fide network perspective. Manage. Commun. Q. 26, 623–654. doi:10.1177/0893318912462014

Cooren, F., Brummans, B. H. J. M., and Charrieras, D. (2008). The coproduction of organizational presence: a study of Medecins Sans Frontieres in action. Hum. Relat. 61, 1339–1370. doi:10.1177/0018726708095707

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Dageid, W., and Duckert, F. (2008). Balancing between normality and social death: black, rural, South African women coping with HIV/AIDS. Qual. Health Res. 18, 182–195. doi:10.1177/1049732307312070

de Souza, R. (2012). Theorizing the relationship between HIV/AIDS, biomedicine, and culture using an urban Indian setting as a case study. Commun. Theory 22, 163–186. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01403.x

Dearing, J. W., Rogers, E. M., Meyer, G., Casey, M. K., Rao, N., Campo, S., et al. (1996). Social marketing and diffusion-based strategies for communicating with unique populations: HIV prevention in San Francisco. J. Health Commun. 1, 343–363. doi:10.1080/108107396127997

DeJong, J., and Mortagy, I. (2013). The struggle for recognition by people living with HIV/AIDS in Sudan. Qual. Health Res. 23, 782–794. doi:10.1177/1049732313482397

Desouza, R., and Dutta, M. J. (2008). Global and local networking for HIV/AIDS prevention: the case of the Saathii E-forum. J. Health Commun. 13, 326–344. doi:10.1080/10810730802063363

Dutta, M. J. (2007). Communicating about culture and health: theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun. Theory 17, 304–328. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x

Dutta, M. J. (2015). Decolonizing communication for social change: a culture-centered approach. Commun. Theory 25, 123–143. doi:10.1111/comt.12067

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Greeff, M., Phetlhu, R., Makoae, L. N., Dlamini, P. S., Holzemer, W. L., Naidoo, J. R., et al. (2008). Disclosure of HIV status: experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qual. Health Res. 18, 311–324. doi:10.1177/1049732307311118

Hardy, C., Lawrence, T. B., and Phillips, N. (2006). Swimming with sharks: creating strategic change through multi-sector collaboration. Int. J. Strateg. Change Manage. 1, 96–112. doi:10.1504/IJSCM.2006.011105

Ho, E. Y., and Robles, J. S. (2011). Cultural resources for health participation: examining biomedicine, acupuncture, and message therapy for HIV-related peripheral neuropathy. Health Commun. 26, 135–146. doi:10.1080/10410236.2010.541991

Hsieh, H., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

Iwelunmor, J., and Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2012). Cultural implications of death and loss from AIDS among women in South Africa. Death Stud. 36, 134–151. doi:10.1080/07481187.2011.553332

Iwelunmor, J., Zungu, N., and Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2010). Rethinking HIV/AIDS disclosure among women within the context of motherhood in South Africa. Am. J. Public Health 100, 1393–1399. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.168989

Johnny, L., and Mitchell, C. (2006). “Live and let live”: an analysis of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination in international campaign posters. J. Health Commun. 11, 755–767. doi:10.1080/10810730600934708

Kiley, E. E., and Hovorka, A. (2006). Civil society organisations and the national HIV/AIDS response in Botswana. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 5, 162–178. doi:10.2989/16085900609490377

Kwait, J., Valente, T. W., and Celentano, D. D. (2001). Interorganizational relationships among HIV/AIDS service organizations in Baltimore: a network analysis. J. Urban Health 78, 468–487. doi:10.1093/jurban/78.3.468

Lammers, J. C., Barbour, J. B., and Duggan, A. P. (2003). “Organizational forms of the provision of health care: an institutional perspective,” in Handbook of Health Communication, eds T. L. Thompson, A. M. Dorsey, K. I. Miller, and R. Parrott (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 319–345.

Maguire, S., and Hardy, C. (2005). Identity and collaborative strategy in the Canadian HIV/AIDS treatment domain. Strateg. Organ. 3, 11–45. doi:10.1177/1476127005050112

Maguire, S., Hardy, C., and Lawrence, T. B. (2004). Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Acad. Manage. J. 47, 657–679. doi:10.2307/20159610

Maguire, S., Phillips, N., and Hardy, C. (2001). When ‘silence = death’, keep talking: trust, control, and the discursive construction of identity in the Canadian HIV/AIDS treatment domain. Organ. Stud. 22, 285–310. doi:10.1177/0170840601222005

Maxon, R. (2009). East Africa: An Introductory History, 3rd Edn. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

McArthur, M., Birdthistle, I., Seeley, J., Mpendo, J., and Asiki, G. (2013). How HIV diagnosis and disclosure affect sexual behavior and relationships in Ugandan fishing communities. Qual. Health Res. 23, 1125–1137. doi:10.1177/1049732313495327

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Miller, A. N., and Rubin, D. L. (2007). Factors leading to self-disclosure of a positive HIV diagnosis in Nairobi, Kenya: people living with HIV/AIDS in the sub-Sahara. Qual. Health Res. 17, 586–598. doi:10.1177/1049732307301498

Miller, A. N., and Rubin, D. L. (2011). “Communication with religious leaders about HIV: Perspectives of HIV-positive persons in Nairobi, Kenya,” in Health Communication and Faith Communities, eds A. N. Miller and D. L. Rubin (New York, NY: Hampton Press), 203–220.

Mupenda, B., Duvall, S., Maman, S., Pettifor, A., Holub, C., Taylor, E., et al. (2014). Terms used for people living with HIV in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Qual. Health Res. 24, 209–216. doi:10.1177/1049732313519869

Murphy, A. G. (2013). Discursive frictions: power, identity, and culture in an international working partnership. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 6, 1–20. doi:10.1080/17513057.2012.740683

Murray, L. R., Garcia, J., Munoz-Laboy, M., and Parker, R. G. (2011). Strange bedfellows: the Catholic Church and Brazilian National AIDS Program in the response to HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Soc. Sci. Med. 72, 945–952. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.004

Muturi, N., and Mwangi, S. (2011). Older adults’ perspectives on HIV/AIDS prevention strategies for rural Kenya. Health Commun. 26, 712–723. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.563354

Oetzel, J., Wilcox, B., Archiopoli, A., Avila, M., Hell, C., Hill, R., et al. (2014). Social support and social undermining as explanatory factors for health-related quality of life in people living with HIV/AIDS. J. Health Commun. 19, 660–675. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.837555

Okoror, T., Belue, R., Zungu, N., Adam, M. A., and Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2014). HIV positive women’s perceptions of stigma in health care settings in Western Cape, South Africa. Health Care Women Int. 35, 27–49. doi:10.1080/07399332.2012.736566

Petros, G., Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Simbayi, L., Ramlagan, S., and Brown, B. (2006). HIV/AIDS and ‘othering’ in South Africa: the blame goes on. Cult. Health Sex. 8, 67–77. doi:10.1080/13691050500391489

Results from the 2011–12 Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey: HIV Fact Sheet by Region. (2015). Available at: http://www.egov.go.tz/egov_uploads/documents/HIVFactsheetbyRegion_sw.pdf

Saleem, H. T., Surkan, P. J., Kerrigan, D., and Kennedy, C. E. (2016). Childbearing experiences following an HIV diagnosis in Iringa, Tanzania. Qual. Health Res. 26, 1473–1482. doi:10.1177/1049732315605273

Sastry, S. (2016). Long distance truck drivers and the structural context of health: a culture-centered investigation of Indian truckers’ health narratives. Health Commun. 31, 230–241. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.947466

Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Seo, M., and Creed, W. E. D. (2002). Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: a dialectical perspective. Acad. Manage. Rev. 27, 222–247. doi:10.2307/4134353

Singhal, A. (2003). Focusing on the forest, not just the tree: cultural strategies for combating AIDS. MICA Commun. Rev. 1, 21–28.

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2015). HIV Estimates with Uncertainty Bounds 1990-2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/HIV_estimates_with_uncertainty_bounds_1990-2014

Keywords: culture-centered approach, HIV/AIDS, institutional perspectives on health organizations, people living with HIV/AIDS organizations, sub-Saharan Africa

Citation: Olufowote JO (2017) An Institutional Field of People Living with HIV/AIDS Organizations in Tanzania: Agency, Culture, Dialogue, and Structure. Front. Commun. 2:1. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2017.00001

Received: 15 September 2016; Accepted: 12 January 2017;

Published: 31 January 2017

Edited by:

Shaunak Sastry, University of Cincinnati, USAReviewed by:

Raihan Jamil, Zayed University, United Arab EmiratesAgaptus Anaele, Emerson College, USA

Patrick J. Dillon, Kent State University at Stark, USA

Copyright: © 2017 Olufowote. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James Olumide Olufowote, olu@ou.edu

James Olumide Olufowote

James Olumide Olufowote