Pivoting in the Time of COVID-19: An in-Depth Case Study at the Nexus of Food Insecurity, Resilience, System Re-Organizing, and Caring for the Community

- 1Department of Communication Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, United States

- 2Department of Communication, Journalism, and Media, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA, United States

According to the School Nutrition Association, nearly 100,000 schools serve free or reduced school lunches and breakfasts daily to approximately 34. 34 million students nationwide. However, as COVID-19 forced many schools to close, students who depended on the public schools to meet the majority of their nutritional needs faced an even larger battle with food insecurity. Recognizing this unmet need, and that food insecurity was intertwined with other needs within the community, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and its satellite contemporary art space the Momentary, partnered with the Northwest Arkansas Food Bank and over 30 additional partner organizations to pivot their existing outreach services. In this case study, we identify lessons learned by Crystal Bridges that might be useful for other organizations who seek to foster meaningful engagement with the public, especially in times of crisis. Specifically, we focus on three main lessons: 1) how the museum created a plan to learn through the pivot in order to capture their own lessons, 2) how the members of the organization experienced a sense of coming together (congregation) during the pivot, and 3) how the organization planned to improve both internal and external communication.

Introduction

In March of 2020, when quarantine was falling over much of the United States, people became very concerned about stocking their homes with food. In the following weeks and months, what began as “stocking up” quickly slid into stockpiling and even hoarding large amounts of perishable and non-perishable foods. Behavioral economists, in particular, were interested in how people were spending money, especially on food, in order to gain a sense of security, and how it led to unusual hoarding behaviors (Baddeley, 2020). However, the “security” afforded to those who had the luxury to store-up resources was not felt by all; some of the most vulnerable in our society watched as their trusted sources of sustenance began to dry up.

According to the School Nutrition Association, nearly 100,000 schools serve free or reduced school lunches and breakfasts daily to approximately 34.34 million students nationwide (Okamoto, 2020). However, as COVID-19 forced many schools to close, students who depended on the public schools to meet the majority of their nutritional needs faced an even larger battle with food insecurity. In light of this, the USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) introduced “key flexibilities” and contingencies to existing programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Child Nutrition Programs, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), among others (Falkheimer and Heide, 2006). For example, the Nationwide Parent/Guardian Meal Pick-up Waiver allowed parents/guardians to pick-up meals and bring them home to their children though the 2020–2021 school year.

Even with all of this flexibility being introduced into the system, unmet need continued to be a problem in many communities. A survey of school nutrition professionals conducted from April 30th-May 8th representing 1,894 school districts nationwide, showed that “95% of respondents were engaged in emergency meal assistance, and combined, these districts reported serving more than 134 million meals in April alone” (Buzanell, 2010).

Recognizing this unmet need, and that food insecurity was intertwined with other needs within the community, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and its satellite contemporary art space the Momentary, partnered with the Northwest Arkansas Food Bank and over 30 additional partner organizations to pivot their existing outreach services. The Chief Education Officer explained, “Art and arts programming are powerful aids to dispel the effects of social isolation, but we also have team members who can be of service to the community in other ways right now” (Buzzanell and Houston, 2018).

Crystal Bridges reallocated staff and resources to focus on five areas of support: “food, internet, housing, artist relief, and a campaign for social belonging to foster connections with vulnerable, isolated groups.” As a result, they’ve distributed nearly 2,000 food boxes per week to area food pantries, as well as an additional 3,600 meals for school children. Delivering food that could be prepared by children for themselves (and often for other children in the family), directly to the apartments and homes where they lived helped fill a gap in support services. In this way, our approach is similar to Okamoto (2020), Houston (2018) in that we position Crystal Bridges as an organization that acts “as a scaffolding which connects individual and community levels of resilience” (p. 619).

We now live in an era of crisis acceleration (McGreavy, 2016) wherein organizations have to monitor increasingly complex risks with the potential to become crises, and once they do become crises, organizations must move quickly. This essay takes a case study approach to interrogate how one community organization used communication to adapt quickly to crisis and mobilize resources to address multiple scales and types of resilience (Gordon and Hunt, 2019a). The communication and organizing successes by Crystal Bridges in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies resistance to acquiesce to the intersectional inequities already existent within United States society, amplified since early 2020, and particularly the conventional food system (Schraedley et al., 2020). This case study illuminates how communication processes can support adaptive crisis behavior, organizational restructuring, building resilience, and creatively advancing food security (Gladwell, 2000). Specifically, we seek to identify lessons learned by Crystal Bridges during the pivoting process, that might be useful for other organizations who seek to foster meaningful engagement with the public, especially in times of crisis. To this end, we performed a textual analysis of the in-depth evaluation materials produced by Crystal Bridges (based on data gathered before, during, and after the pivot) to identify barriers and facilitators to reaching their goals. To frame and clarify information in the lessons learned documents we gathered, we spoke with five employees who were instrumental in the communication, operations, and logistics of the pivot (Sipiora and James, 2002). The stories of their lived experiences compliment and extend the textual analysis, and are included as “personal correspondence” within this article. We seek to add to the growing literature on resilience, specifically by exploring these stories for lessons learned as an integration of “tragedy as well as triumph” that acknowledges “the frailty and vulnerability of the human spirit as well as its strength (Barlett and Chase, 2004). In other words, when we directly asked people to reflect on their experiences of what worked well and what didn’t work during the pivot, they shared tragedy and triumph from their perspectives at the “intersections of people, place and identity” (p. 619) during a time of crisis.

Addressing Food Justice During a Prolonged Crisis

Crystal Bridges was charged by their Board of Directors to find a way to continue to serve the community when the COVID-19 global public health crisis shut down much of the “business as usual” flows between societal institutions and individuals. This shutdown occurred in all sectors including private, public, and not-for-profit. As an art museum, Crystal Bridges, fits into the not-for-profit space and has a mission to “welcome all to celebrate the American spirit in a setting that unites the power of art with the beauty of nature.” (Department of Educat) The Mission Statement language to “welcome all” is taken seriously. As a world-class art museum, Crystal Bridges operates in a space where culture is celebrated and world-class art is available to share with the community. Like many art museums, sharing art with the community means the community is welcome to visit the museum and take in the permanent and temporary exhibitions. In addition to the exhibits, visitors to Crystal Bridges have access to educational programming, the beauty of the grounds (120 acres in the Northwest Arkansas Ozarks), and meals or snacks in the on-site restaurant and café. During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic across the United States in March 2020, Crystal Bridges, like many other community organizations, was forced to shut its doors to the public. This posed a particularly unique challenge to continue its normal operations in order to carry out the organization’s mission.

In addition to Crystal Bridges’ mission and the Board of Directors (BOD) charge to find a way to continue to serve the community, after a recent evaluation of the organization’s operations and programming, a decision was made to bolster their community engagement. The previous year, Crystal Bridges had committed its Community Engagement focus to work on anti-racist initiatives (Orr, 2009). Art museums often operate as a “coded space” where certain groups of people don’t necessarily feel welcome inside the museum’s various spaces, and Crystal Bridges discovered that it too had work to do in this area (Hertz et al., 2020). In particular, Crystal Bridges discovered that people of color reported they were more comfortable with behavioral norms in outside spaces, resulting in a “perception barrier” for this demographic to feel welcome and comfortable inside the museum’s walls. Combining the goal of inclusion with the feedback they received about comfort levels in the museum revealed the need to make changes. This context combined with the dynamic needs of the unfolding pandemic led to an opportunity to not just bolster, but re-imagine the organization’s community engagement.

When the museum was required to shut its doors to the public due to the spread of the COVID-19 virus, this also meant that it no longer had work for dozens of employees the organization employed to support and engage with visitors inside the museum. The organization’s board of directors and other members of leadership teams recognized an environmental change that may have caused a “tipping point” (Fisher et al., 2020). Crystal Bridges was in a kairotic moment-a time of crisis and opportunity (Poppendieck, 1999).

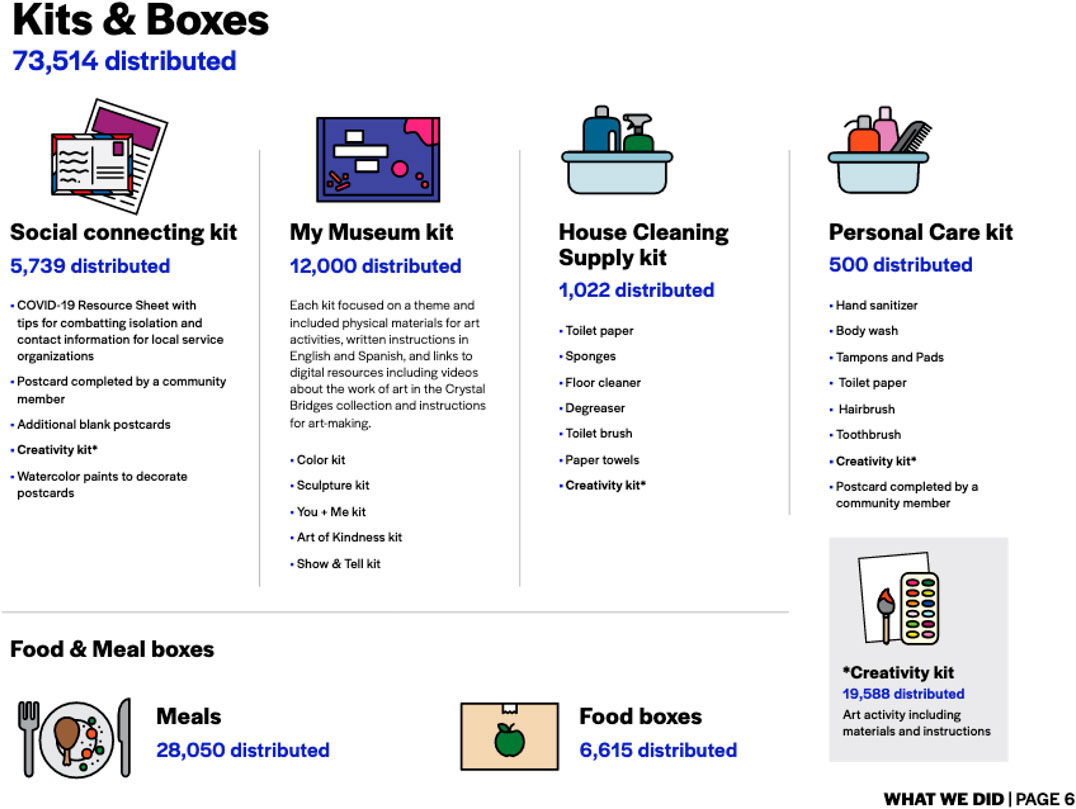

A series of Listening Sessions were set up with partner community agencies and key museum leadership in Education and Community Outreach departments. Some of these were the museum’s pre-existing partners and some would become new agency partners. As a result of these Listening Sessions, five areas of need and opportunity were identified. These five areas were: 1) food; 2) housing; 3) mental health; 4) suffering artists; and 5) a digital divide. Crystal Bridges decided to partner with specific community agencies in each of these areas of need as identified by the Listening Sessions and Community Needs Assessment. By early April, Crystal Bridges pivoted its operations from a “business as usual” cultural art institution to what could only be described as a crisis intervention and humanitarian relief organization. “Task Teams” (Gordon and Hunt, 2019b) composed of a Strategy team member, Community Engagement team member, museum Operations staff, an internal content specialist, and a community agency partner. As such these teams were cross-functional and a new form of Crystal Bridges-Community interface. The tasks each of these teams began to engage included the following: 1) food distribution; 2) household and personal care supply distribution; 3) social connecting; 4) artist support; and 5) internet and information sharing. These five task areas correlated with the results of the above-described Listening Sessions and Community Needs Assessments. The number of kits and boxes that were distributed for each task area are presented in the graphic below. The “social connecting kit” and the “my museum kit” were aimed at needs beyond those of food, personal care products, and house care products. The decision to centralize creative arts during this time was in response to the need to help improve quality of life, not just to sustain it. While reflecting on the children he visited, one of the team organizers said “We can give them food, but that only takes up a small fraction of their day. The rest of the time they might be stuck in an apartment with not much to do.” Although it was not the goal of our lessons learned work with the museum, this particular combination of food security work coupled with fostering creativity through the arts adds an additional item to Buzzanell’s (2018) call to investigate resilience through storytelling, rituals, routines, etc. Art and artistic expression are powerful ways to learn about the struggles and strategies of those in crisis.

The food distribution task grew out of the observations and knowledge gained by Crystal Bridges personnel through dialogue with the Northwest Arkansas Food Bank. The Northwest Arkansas Food Bank is located roughly 16 miles south of Crystal Bridges off I-49 in Bethel Heights. The food distribution task team began by mapping resources that Crystal Bridges could leverage during the COVID-19 crisis and museum shut down to engage the food insecure in their community. The Food Bank had lost much of its volunteer force as a result of the quarantine orders issued to protect public health against the spread of the virus. Thus, the Food Bank of Northwest Arkansas found itself in a position with a food supply that it couldn’t pack and distribute to county beneficiaries. In addition to the new challenges faced by the Food Bank of food (re)packing and distribution, supply chains in general became an exacerbated problem in the US for many communities, businesses, government agencies and programs, and schools at the onset of the pandemic in Spring 2020 (Abi-Nader et al., 2009). In this context, Crystal Bridges’ resource mapping identified two key assets that could potentially be marshalled and repurposed: its people and its command of physical space.

As a cultural institution, Crystal Bridges was invested in social justice and the opportunity to repurpose its people and its physical space in order to fill gaps and needs created by the pandemic became their new vision, purpose, and motivation. Food justice is an important but often overlooked subcategory of social justice but through Listening Sessions, Community Needs Assessments, Resource Mapping, and new networks for action (Abraham, 1971), Crystal Bridges was able to mitigate hunger and injustice amplified by the public health crisis while also advancing their own Community Engagement initiatives. This sort of crisis intervention and work revisioning is not the norm, particularly for community organizations who may not even have a mandate or mission to operate in these spaces or ways.

Of particular interest and import with regard to the food distribution task is: 1) the way in which Crystal Bridges arrived at a finding of real community need; 2) the way in which communication was central to that discovery; 3) the multi-level nature of the crisis that resulted in both food security and food justice shortcomings for the community.

After partnering with the Food Bank, the food distribution task team also needed to locate the populations most in need of a continuous flow of food. The Listening Sessions revealed that public schools in the community were having difficulty accessing food. Several of the K-12 public schools in the area are Title one Schools (Singer et al., 2020), which means that children from low-income families make up at least 40% of the school’s enrollment.1 Title one Schools receive federal funding to support low-income students’ ability to perform at the standard required by state academic standards. The funding is used for school-wide programming to help raise the performance of the lowest-performing students. The two factors of age (legal minors below 18 years of age and low-income backgrounds (according to official United States household income determinants), combined to create a very vulnerable population.

The second thing important to note is how Crystal Bridges determined this population’s unmet need. As a non-profit community organization with some standing, Crystal Bridges began its food distribution community outreach work by going through official channels. That is, an inquiry was made with Department of Education officials to verify the food access gap for community schools in Northwest Arkansas.2 Crystal Bridges intended to interface with the Department of Education (DOE) in order to ascertain potential causes to this food access problem and begin collaborating with the Food Bank and the DOE to intervene and help mitigate the problem. Strangely though, according to the DOE contact, there was no food access problem at the Title 1 schools (U.S. Department of Education, 2018). In an effort to cross-reference this information and messaging from official sources, Crystal Bridges began conversations with local school administrators to determine whether they were experiencing exacerbated food access problems in the face of COVID-19. The response received from these local community administrators was markedly different than the perspective of the DOE. In concert with this new information, Crystal Bridges took action and moved forward with their food distribution task team in order to help the Food Bank distribute available foodstuffs to local populations in real need. Crystal Bridges relied on personal relationships (and those individuals’ lived experiences) to cross-reference official sources of information and messaging regarding need. This triangulation of information is crucial in emergencies because distant, official sources may not have accurate on the ground, locally relevant, and accurate data or understanding. Scholars and analysts have anticipated the need for deliberately building more resilience into our local communities and basic life support systems for some time now.3 This became strikingly clear during 2020 with breakdowns in supply chains. Building community level resilience means building redundancies into the system. One of the kinds of redundancies that may be essential but overlooked or not considered in crisis mode is communication behavior. Information seeking behavior needs to change and multiple sources need to be consulted to arrive at the most accurate picture possible of needs, causes, gaps, resource availability, opportunities, and allies. The Midwest Academy has a community organizing and advocacy tool (strategy chart)4 that very much resembles many of the steps that Crystal Bridges took when re-organizing themselves in response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

The third point that is important to make here is that, based on the data, the situation that Crystal Bridges food distribution task team encountered actually addressed multiple levels of intervention. The first, most obvious level is food insecurity but the second, less obvious level is food justice. For a non-profit art museum to pivot in a time of crisis, do novel needs assessment, partnership building, resource mapping, and repurposing of their assets and capital is not expected, not the norm, and is laudable. In addition to this intervention, however, there is another level of action, food justice advocacy and this is a more systemic contribution to society.

A cursory first analysis might suggest that through their food distribution task design, Crystal Bridges is only reinforcing the perpetuation of a disempowering hunger management status quo for the school children of low-income households in Benton County. There is some legitimacy to this kind of critique. The anti-hunger movement has been in a “holding pattern” for some time now in the United States as more conventional approaches to solving food insecurity include potentially fraught relationships between food pantries, food banks, federal food programs, and agribusiness corporations.5 The charitable and philanthropic investments in hunger reduction in the United States not only offer financial benefits to corporations that are not in the business of sustainable community food systems but they also create a disempowered and dependent population. By establishing the anti-hunger structures and relationships that exist today in the US, food assistance recipients are treated as clients rather than partners. In Sweet Charity, Poppendieck contends that these clients end up often waiting in lines, feeling like dejected objects.6 This is not the same as partnering with the poor to help build their political and economic power. Instead, the “hunger problem couches income inequality in a veil of temporary need that heralds corporate philanthropy and draws attention away from systemic causes.”7

The leadership of Crystal Bridges wasn’t oblivious to these complexities as the Executive Director voiced regret about the limited sustainability of their food distribution crisis intervention.8 Nonetheless, committed and passionate anti-hunger advocates recognize these contradictions and have begun proposing viable alternatives. Even still, it is important to distinguish between crisis response and sustainable community development. With its mission, community organization type, and federal tax status as a 501c (3), Crystal Bridges may actually be positioned more as an agent of sustainable community development than an emergency response organization like the American Red Cross. In this case, however, Crystal Bridges’ reinvention of itself in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis has yet another level of engagement. In virtue of the BOD charge to find a way to continue to operate and serve the community, the overall Community Engagement strategy enabled Crystal Bridges employees to continue to have paid work, but the work itself would be very different than their normal day-to-day task performance. Even though the museum was mandated to shut its doors to the community, potentially removing employees from its payroll and further exacerbating the structural inequity that hunger is merely an ugly symptom of, it was able to creatively adapt and pivot its entire identity and structure and thereby attack both food insecurity as well as advance food justice through keeping community members and their households in gainful employment while contributing to an immediate need which highlighted even more weaknesses in the political and economic arrangements within United States society.

Injustices across food chains share ecological and economic links.9 The national collaborative work of the Center for Whole Communities offers a field guide for community food system planning and evaluation—Whole Measures for Community Food Systems.10 This field guide lays out six relevant dimensions for evaluating a community food system: 1. Justice and Fairness; 2. Strong Communities; 3. Vibrant Farms; 4. Healthy People; 5. Sustainable Ecosystems; and 6. Thriving Local Economies. While the specific criteria for Food Justice include: 1. Provides food for all; 2. Reveals, challenges, and dismantles injustice in the food system; and 3. Creates just food system structures and cares for food system workers; and 4. Ensures that public institutions and local businesses support a just community food system.

While Crystal Bridges approach to ease the suffering of their community in the aftershock of nation-wide quarantines will not transform the United States food chain, it is also important to observe that their response advanced food justice by stepping in where others did not or could not (including the DOE and Northwest Arkansas Food Bank) to provide food to some of the most vulnerable in the community (children from predominantly low-income households) while also contributing to a thriving local economy by finding creative ways to keep their labor force on the payroll. While the particularities of the kairotic moment Crystal Bridges faced may not be replicable, their process and the thoughtful, effective outcomes instantiate the kind of creative rethinking and reworking more individuals and institutions will need to engage in order to creatively address persistent and troubling food system problems.11

Lessons Learned: Analysis of the Evaluation Materials

Crystal Bridges has a research team who was tasked with evaluating the effectiveness of the different initiatives launched during the pivot. This team crafted an evaluation plan “that would focus on the collective impact across the region and within Crystal Bridges and the Momentary.”12 The researchers asked three questions in their evaluative efforts; 1) “How did this project impact the organizations and staff members of Crystal Bridges and the Momentary?” 2) “How did this project impact Northwest Arkansas Communities?” and 3) “What have we learned that could impact future community engagement efforts?” Over the six-month period, the evaluation team worked with the community engagement team to learn about when new project phases were “ramping up or ending in order to schedule data collection activities in tandem” (p. 13). Our goal was to examine this document for the transferrable lessons that could be useful to other organizations that might find themselves in similar situations. From this analysis, we’ve identified lessons in three areas: 1) planning to learn, 2) organizational congregation through segregation, and 3) internal and external communication.

Category #1: Planning to Learn

Any new community engagement initiative should be evaluated not just for effectiveness at reaching outreach goals, but also for how the employees perceive their own work and efficacy. One of the highest priorities of the museum during the pivot was to provide work for employees who wanted to keep working. For example, many of the museum’s staff who were employed in the museum’s restaurant picked up hours packing the My Museum kits, personal hygiene kits, and cleaning kits. One employee wrote “Es una gran ayuda para la gente y claro que si. Tambien es una gran ayuda para nosotros los que trabajamos en la cocina, gracias a esto hemos tenido trabajo.” (It’s a great help for the people, of course it is. It’s also great help for those of us who work in the kitchen. Thanks to this, we have had work” (p. 17). Another employee wrote, “I’m thankful the museum is giving me the opportunity to earn wages” and another wrote “Also, it feels like it’s not just made up work. That we are actually contributing. That feels good” (p. 17).

It takes a lot of effort to maintain momentum for a project of this size and it is important that employees see their work as necessary, and their efforts as making a difference. 86% of the employees agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I feel proud of my organization’s community engagement initiatives during COVID-19.” One survey respondent said “Packing meals on the loading dock was really rewarding and I actually felt like my help made a difference.” Another respondent said “This has been one of the most meaningful projects I’ve worked on.” Initially, there was concern that highly trained professionals might not feel fulfilled with the assembly line style work putting together the kits for delivery. However, when people realized they could contribute meaningfully to the work that needed to be done, everyone stood to gain. For example, the creativity kit contained a craft that required a certain number of paperclips. Employees diligently counted out the paperclips, which was time consuming, until the chefs from the restaurant observed the process, filtered it through their own specific training, and recommended weighing the paperclips instead so that the process could be faster. These creative, collaborative opportunities provided the chance for people to recognize that their contributions could make a difference. It also provided a mechanism for building multiscalar resilience through redundancy and cross-functional task work that took advantage of knowledge and skill transference.

It was important for museum employees to feel valued throughout the process, but because of the assembly line style of work and the fact that most of the employees did not deliver the kits (in order to see those they served) team leaders worked to identify ways to prevent people from feeling disconnected from the fruits of their labor. One tactic was to build prototypes of the kits so that people who were assembling one part of it could see what the end result would look like. Another tactic was to capture stories and photos (when possible) of those receiving the kits, and make sure that the people assembling the kits saw that feedback. In this way, team leaders were working to create resilience in the community, but they were also concerned about the resilience of their employees through the process.

Staff members also reported personal learning that occurred throughout the process that enriched them in multiple ways. 77% reported that they felt more connected to Northwest Arkansas, and one staff member said they “felt ignorant of the disparities” across Northwest Arkansas prior to COVID and this project.

In addition to learning about the importance of performing valuable work, the employees learned lessons about the constraints of collecting sensitive data to determine project effectiveness, in a pandemic that requires social distancing and has other constraints. The research team tasked with evaluating the different initiatives during the pivot encountered hurdles to data collection. They made intentional decisions given these constraints, adjusted as they could, and explained them in their reporting. One of the most important considerations was to recognize power dynamics (between provider and recipient or evaluator and evaluation participant) and “scale” data accordingly. For the evaluators, this meant making the decision not to collect data directly from public individuals receiving critical resources. Rather, they “focused on understanding the collective impact from the scale of resources distributed, as well as on gathering feedback from community partner organizations” (p. 13). They wrote, “While these decisions produced limitations for the kinds of impact we can articulate, the evaluation team felt it was more important to forge or strengthen community partner relationships during this period” (p. 13). Constraints on data sensitivity can also lead to valuable lessons regarding culturally sensitive communication. One example of this is Crystal Bridges’ community needs assessment with Northwest Arkansas populations such as the Marshallese.8 This population is a comparatively closed community with higher than average language barriers.13 The development of the Personal Care Kits for the community was facilitated by increased cultural sensitivity of Crystal Bridges.

However, they were also creative about how they gathered data when they could. They honored the time of the participants (particularly networked organizations) by joining existing debriefs or regularly scheduled meetings to avoid adding another meeting to their schedules. They also delayed data collection or considered alternative ways of learning about a particular issue if they could.

Category #2: Congregation Through Segregation

Organizations who are faced with a shared, external threat, such as a pandemic, may pivot that threat into a way to experience new type of congregation within the organization and with organizational partners. In other words, a common threat can function to bring people together. Employees reported that they learned about the constraints facing employees who do different work in the organization, and 69% of employees reported feeling more connected to their co-workers as result of the community engagement efforts. Importantly, employees also reported learning more about the internal structures of partner organizations and the best strategies for communicating with these partners. When reflecting on the lessons learned, the School and Community Programs Coordinator mentioned that she had been working to engage the schools with the museum long before the pandemic (personal correspondence). She attended back-to-school meetings at the local schools in the fall to provide teachers the opportunity to integrate the museum and its educational offerings into their curriculum. She told us that building that network and making those connections outside of the time of crisis, enabled her to call upon those networks to identify the best ways to help during the crisis.

Her work with the schools outside of the time of crisis made it much easier for her to communicate with them during the crisis. She was able to organize the delivery of the kits with greater ease and the people she had already networked with became additional assets to spread the word about the work that Crystal Bridges was doing. For example, when they delivered the kits to the teachers they had already met, they were sure to make the boxes very conspicuously labeled so that they would draw attention. In effect, the teachers who received the brightly labeled kits functioned to advertise the opportunity to other teachers.

Crystal Bridges’ community engagement assessment combined with their pivot response to the pandemic, new forms of community organization partnership were discovered. Partnering with the Northwest Arkansas Food Bank allowed community needs to be better filled. In the aftermath of the initial widespread outbreaks and quarantines in March 2020, the Food Bank witnessed volunteer attrition and heightened community food insecurity. Because of the asset mapping conducted by Crystal Bridges in conjunction with their new community engagement efforts, an innovative partnership was formed to bridge the gap in terms of both food security workers as well as innovative food distribution networks. Due to the success of this particular temporary crisis response, Crystal Bridges has decided to continue its partnership with the Northwest Arkansas Food Bank in its redesign of their 2021 Community Engagement Pillars to include ASAP (Art + Social Impact Accelerator Program). This reveals that responding to a crisis with a community outreach/engagement based strategy combined with internal asset mapping can result in new organizational fields that better serve community needs and strengthen resiliency.

Category #3: Internal and External Communication

Some of the most important lessons from the pivot were about ways to improve both internal and external communication. When an organization creates a new system or initiates a large-scale change, the success or failure of that initiative is bound-up in the communication around it. For example, “The ways in which decisions were made and the flow of communication made it difficult for some task team members to understand the current status of each initiative, which in turn caused uncertainty” (p. 20). The pressure to move quickly in a crisis produces the context wherein this type of internal communication may not be as effective. One tension that arises in many organizational crises is the increased need for timely information to decrease uncertainty, with a decreased time to produce (and consume) these messages. Additionally, internal updates that are produced may not be read or understood when people are struggling to keep up with a changing work environment. One way to combat this is to standardize expectations when it comes to communication frequency and content. For example, if people knew they would receive an internal update on Mondays that summarized the work of the last week, projected the needs of the next week, and identified who would be responsible for following up, they may feel more certain about their work, even in a context of uncertainty. Additionally, organizations needing or choosing to pivot in response to crisis can build a new kind of expectancy value for adjusted communication behaviors into their organizational cultures. Leadership that practices more aggressive information-seeking behaviors can provide an example for others within an organization to follow. Internal communication between subordinates and superiors can be modeled after the crisis communication behaviors adopted by leadership. Such aggressive information-seeking behavior can reduce uncertainty for both task and social behaviors and provide better information flow through differing levels of an organization hierarchy.

The School and Community Programs Coordinator reflected on one of the communication strategies that helped with both internal and external communication: communicating the tentativeness of a plan. She reflected on the need to provide information to people even if it is impossible to get rid of all uncertainty and what those messages might sound like. She said that one strategy is to tell people “this is the plan right now, but if it changes, here’s how we will change to adapt” (personal correspondence, January 1, 2021). This increased transparency can help organizations pivot more efficiently, even if the plan itself continues to change, the planning becomes the focus for internal communication and this process-orientation can facilitate more rapid and less stressful program and behavior change. Another strategy was to communicate that leadership was open to problem-solving ideas, as opposed to seeming as if leadership had all of the answers and were just handing them out. She said one way to do this was to say openly, “We think this is what we will do but if you have a different idea, please share it.” Rather than having to have all of the answers, leadership was open to building the best answers with the employees and partners.

Employees also had a chance to look back at the questions they initially asked about the project and what they would ask next time to help with both internal and external communication. The nature of how these questions changed is instructive for any organization who might be embarking on a new, large-scale change. For example, employees originally asked “How can we supply critical resources to those in need?” After reflection, they realized they needed to be asking much more refined questions. So that one question became five much more detailed questions. “If we’re supplying materials, who decides which resources are supplied? How will we store materials? How long do they take to purchase and ship? Where will they be assembled and who is responsible for assembling? How long will assembly take? What does the drop-off site look like and who is the lead contact there?” (p. 21). The process of looking back to “what we thought at the time” vs. “what we learned” enables organizations to be more resilient and apply the same logic of reasoning to other problems.

External communication with partnering organizations as well as the public was critical to the success of this project. Reflection on what worked and what didn’t work also led to important lessons for communication. Most of the feedback that Crystal Bridges received was about the products (contents of the kits) and some were about the process. For example, community partners reported that the size of the hand sanitizer bottles in the care kits were so large that they weren’t portable to some members experiencing hosing insecurity. Another example is that the personal care kits might not have taken cultural differences into consideration. One of the communities who were the hardest hit by the pandemic in Northwest Arkansas were the Marshallese. The personal care kits originally included tampons, which are inapplicable to this community “because of cultural differences.” The pragmatic feedback about the size of the hand sanitizer bottles, and the cultural feedback about the hygiene products were lessons at the content level, but the larger lesson was about working with partners earlier in the process to gather more information about the specific needs of the different communities before identifying any specific solutions.

Conclusion

Organizations have experienced the pandemic in different ways. Some organizations were forced to close their doors and would likely say that the pandemic led to an organizational crisis for them. Other organizations, specifically those whose mission is to aid others during crises, may not see the pandemic as causing a crisis for their particular organization. For example, a hurricane does not necessarily produce a crisis for the American Red Cross; they are in the business of responding to hurricanes. For Crystal Bridges, “the crisis moment would have been to shut down and leave our employees without work” (Executive Director and Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, personal communication, January 1, 2021). To avoid this crisis, Crystal Bridges quickly pivoted to address an emergent need, even though much of that need fell outside of the traditional wheelhouse of a community focused art organization. They were able to make this pivot because of the existing networks they had nurtured, their willingness to come together and set aside official roles and titles to get the necessary work done, using an external threat to create opportunity, and their adaptive internal and external communication strategies.

In the midst of the COVID-19 global pandemic, basic needs for both communities and individuals were undermined. This is particularly true for those that already relied on more external support networks, resources, and programs to meet those needs. Crises such as COVID-19 exacerbated inequities in societal access and distribution to basic needs such as food, as well as higher-order needs such as growth and creativity.14 Recognizing crisis as opportunity, Crystal Bridges pivoted to fill gaps in the newly amplified food access issues instigated by the pandemic. Providing a critical organizational role that no one else in the community was able to, they contributed substantively to an immediate community need while also staving off even worse inequity by repurposing their resources and personnel. In doing so, they were able to engage both food insecurity as well as food injustice. While food security is not the same as food sovereignty or food justice, many contemporary food advocates know that in spite of the seemingly thorny, intractable problems between these movements and discourses, they are inextricably bound together.15

We do not know what the next pandemic (or organizational crisis) might be. We do know that there will be more events that trigger the need to pivot in agile ways. The steps that Crystal Bridges took before, during, and after the initial phases of the pandemic to learn from the environment and their own effectiveness in meeting the needs of their partners is what will develop their capacity to weather crises and cultivate resilience.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://crystalbridges.org/community-engagement/.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The Communication Studies Department and the Office of the Dean at Texas State University supported this research by providing funding for the open access publication fees.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1https://schoolnutrition.org/aboutschoolmeals/schoolmealtrendsstats/

2https://www.fns.usda.gov/coronavirus#flex

3https://schoolnutrition.org/news-publications/press-releases/2020/sna-survey-reveals-covid-19-school-meal-trends-financial-impacts/

4https://crystalbridges.org/blog/crystal-bridges-mobilizes-staff-to-provide-food-arts-and-more-through-the-community-outreach-initiative/

5One of the employees who shared their story is the brother of the first author of this article. The original intent for this case study was to assist in quality improvement efforts with the museum, as well as to gather lessons that could be shared with other non-profits, especially museums who are in a position to meet similar community needs.

6Ibid

7“About” https://crystalbridges.org/about-crystal-bridges-art/

8Executive Director and Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, personal correspondence, January 1, 2021

9Chief Education Officer, personal correspondence, January 7, 2021.

102020 Community Engagement COVID-19 Report

11Andy Fisher (2020).

12Sr Project/Procurement/Operations Manager, personal correspondence, January 14, 2021.

13https://crystalbridges.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2020-Community-Engagement-COVID-19-Report.pdf

14People descended from the Marshall Islands.

15Procurement Manager, January, 14, 2021.

References

Abi-Nader, J., Ayson, A., Harris, K., Herrera, H., Eddins, D., Habib, D., et al. (2009). Whole Measures for Community Food Systems: Values-Based Planning and Evaluation. Fayston, VT: Center for Whole Communities.

Barlett, P. F., and Chase, G. W. (2004). Sustainability on Campus: Stories and Strategies for Change. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Buzanell, P. M. (2010). Resilience: Talking, Resisting, and Imagining New Normalices into Being. J. Commun. 60, 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01469.x

Buzzanell, P. M., and Houston, B. (2018). Communication and Resilience: Multilevel Applications and Insights. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46 (1), 1–4. doi:10.1080/00909882.2017.1412086

Falkheimer, J., and Heide, M. (2006). Multicultural Crisis Communication: Towards a Social Constructionist Perspective. J. Contingencies Crisis Man. 14 (4), 180–189. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5973.2006.00494.x

Fisher, A. (2020). “Hunger Incorporated: Who Benefits from Anti-hunger Efforts?” in S. Jayaraman, and K. De Master (Eds.) Bite Back: People Taking on Corporate Food and Winning. Berkeley: University of California Press

Gladwell, M. (2000). The Tipping Point: Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. New York: Little, Brown, and Company

Gordon, C., and Hunt, K. (2019a). Reform, justice and Sovereignty: A Food Systems Agenda for Environmental Communication. Environ. Commun. 13 (1), 9–22. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1435559

Gordon, C., and Hunt, K.. (2019b). Reform, Justice, and Sovereignty: A Food Systems Agenda for Environmental Communication. Environ. Commun. 13(1), 9–22. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1435559

Houston, B. (2018). Community Resilience and Communication: Dynamic Interconnections between and Among Individuals, Families, and Organizations. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46 (1), 19–22. doi:10.1080/00909882.2018.1426704

Hertz, J. (2020). “Taking Action to Create Change” in S. Jayaraman, and K. De Master (Eds.) Bite Back: People Taking on Corporate Food and Winning. Berkeley: University of California Press

McGreavy, B. (2016). Resilience as Discourse. Environ. Commun. 10 (1), 104–121. doi:10.1080/17524032.2015.1014390

Okamoto, K. E. (2020). As Resilient as an Ironweed:' Narrative Resilience in Nonprofit Organizing. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 48 (5), 618–636. doi:10.1080/00909882.2020.1820552

Orr, D. W. (2009). Down to the Wire: Confronting Climate Collapse. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780195393538.003.0005

Singer, R., Houston Grey, S., and Motter, J. (2020). Rooted Resistance: Agrarian Myth in Modern America. Fayetteville, AR: The University of Arkansas Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv12fw7m2

Schraedley, M. K., Bean, H., Dempsey, S. E., Dutta, M. J., Hunt, K. P., Ivancic, S. R., et al. (2020). Food (In)security Communication: a Journal of Applied Communication Research Forum Addressing Current Challenges and Future Possibilities. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 48 (2), 166–185. doi:10.1080/00909882.2020.1735648

Sipiora, P., and James, S. B. (2002). Rhetoric and Kairos: Essays in History, Theory, and Praxis. New York: SUNY Press

U.S. Department of Education (2018). Improving Basic Programs Operated by Local Educational Agencies (Title I, Part A). Retrieved from <https://www2.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta/index.html>.

Keywords: food justice, case study, crystal bridges museum of American art, lessons learned, crisis communication

Citation: Fox R and Frye J (2021) Pivoting in the Time of COVID-19: An in-Depth Case Study at the Nexus of Food Insecurity, Resilience, System Re-Organizing, and Caring for the Community. Front. Commun. 6:674715. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.674715

Received: 01 March 2021; Accepted: 28 May 2021;

Published: 24 June 2021.

Edited by:

Kathleen P. Hunt, SUNY New Paltz, United StatesReviewed by:

Kristen Okamoto, Clemson University, United StatesLeda Cooks, University of Massachusetts Amherst, United States

Copyright © 2021 Fox and Frye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebekah Fox, rf24@txstate.edu

Rebekah Fox

Rebekah Fox Joshua Frye

Joshua Frye