Social support and coping among female foreign domestic helpers experiencing abuse and exploitation in Hong Kong

- Department of Communication Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Introduction: In Hong Kong, female foreign domestic workers are hired to assist with household chores and care. This study examined the coping and support-seeking strategies that the workers use to tackle workplace abuse and exploitation within the structural confines of their employment.

Methods: A mixed-method design that incorporated a face-to-face survey with 106 migrant domestic workers and 21 in-depth interviews was adopted.

Results and discussion: The results showed that most participants experienced some form of abuse or exploitation. Verbal threats and time exploitation were the most common forms of abuse and exploitation, respectively. Participants' marginalized group status muted their voices when workplace hazards occurred. Accordingly, they preferred emotion-based coping over problem-based coping when encountering abuse and exploitation. Their focus on emotional management was reflected in their acceptance of workplace conflicts as taken-for-granted norms, their avoidance of communicating with employers, and their nonconfrontational endurance of adverse working conditions. Aligned with participants' focus on emotion management, they also reported a stronger need for emotional support than other support functions. Their major sources of emotional support were religious beliefs and other migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. Employers had the potential to fulfill the workers' support needs, but they must take the initiative due to imbalanced power relations.

Introduction

A foreign domestic helper (FDH) is a full-time—most often female—migrant worker who lives with the employer's family to perform general household chores and care. The increased number of FDHs around the world reflects a trend of transnational mobilities based on the globalization of capitalist economies (Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Deng et al., 2021). Migrant workers move from capital-poor to capital-rich countries to seek employment opportunities. However, the trade-off of pursuing financial benefits is the risk of losing social and ethnic status in the host society (Chiu and Asian Migrant Centre, 2005). Domestic work has long been criticized for producing subalternity of the workers by the intersection of gender ideology, class ideology, and a “culture of servitude” (Qayum and Ray, 2003, p. 527; Kaur-Gill et al., 2021). The unbalanced power structure inherent in the work environments render FDHs vulnerable to exploitation and abuse that could have adverse impacts on their health (Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Parreñas et al., 2021). The purpose of this study is to explore FDHs' experiences with abuse and exploitation embedded in the structural settings of their employment and the coping and support-seeking strategies they use to deal with health hazards in the workplace.

Exploitation and abuse among FDHs

The history of FDHs in Hong Kong started in the 1970s when Hong Kong experienced rapid economic growth and more females joined the employment market to earn a living. Hiring FDHs became a way to release the female labor force from the family and cover the gendered responsibility of managing households (Ho et al., 2018; Tam et al., 2018). In 2020, there were 373,884 FDHs in Hong Kong, representing 10% of the overall workforce and providing services to 12% of local households (Immigration Department, 2021; Census Statistics Department, 2021a). Most FDHs (99%) were female and from the Philippines (56%) and Indonesia (42%). In 2020, their monthly wage ranged between HK$4,000 and HK$4,900 (~US$513–US$630), which was affordable for many middle-class Hong Kong families, considering that the median monthly household income for domestic households of four is HK$42,000 (Census Statistics Department, 2021b). The wages of FDHs are higher than local average wages in the Philippines and Indonesia and sometimes even higher than white-collar jobs back home, thus motivating many women to work overseas (Chiu and Asian Migrant Centre, 2005).

While Hong Kong laws protect FDHs' basic needs—food, accommodation, medical services, and insurance—and their responsibilities of only providing live-in domestic services at the residence of their employer and only serving the members of the household (Labour Department, 2022), exploitation and abuse are reported from time to time that pose harm to FDHs' physical and psychological health (Amnesty International, 2014; Mission for Migrant Workers, 2022). Exploitation involves the act of taking unfair advantage of an employee and using their vulnerability to fulfill the employer's own benefit (Zwolinski and Wertheimer, 2017). By law, FDHs should receive welfare, such as a monthly food allowance of HK$1,075, free medical service, and at least one break of no less than 24 h every seven days (Labour Department, 2022). FDHs are entitled to paid annual leave within a period of 12 months following completion of 1 year of service. Exploitation may occur when employers violate the standard employment contract regulated by the government (Immigration Department, 2003). Alternatively, abuse refers to deliberate and intentional unjust practices that cause mistreatment of the workers (Amnesty International, 2014; Okechukwu et al., 2014). Physical abuse involves the use of physical force that creates injuries. Verbal abuse occurs when someone in the workplace uses vexatious comments including swearing, calling names, verbal threats, and insults to embarrass, humiliate, or disregard the worker. Sexual abuse is present in unwanted and unwelcomed behaviors that are conducted in a sexual way without consent (Ullah, 2015).

Human rights organizations have raised concerns about the high rates of overwork and abuse among domestic workers (Amnesty International, 2014; Mission for Migrant Workers, 2022). However, filing complaints about workplace abuse and exploitation is uncommon among FDHs, and getting legal recognition is even rarer (Cheung, 2022). Previous research noted that the barriers to reporting abuse and exploitation may include difficulties in collecting evidence, lack of legal knowledge, feelings of insecurity due to language insufficiency, lack of a witness, a perception of passive responses from the police, fear of being punished, fear of losing their job, and fear of experiencing secondary victimization during the lengthy legal processes (Chiu and Asian Migrant Centre, 2005; Cheung et al., 2019; Cheung, 2022). These findings suggest that FDHs tend to handle workplace hazards on their own, and their nonassertive responses to exploitation and abuse in public discourse seem to echo their muted group status in Hong Kong society (Kaur-Gill et al., 2021).

Structural and cultural underpinnings of abuse and exploitation

Critical scholars have argued that workplace health hazards like abuse and exploitation are not only related to interpersonal factors, such as individual employers' misbehaviors, but also to structural factors, such as the live-in work arrangement and state policies (Lan, 2003; Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Lai and Fong, 2020; Parreñas et al., 2021), and cultural factors, such as societal discrimination (Ladegaard, 2013; Ullah, 2015; Liao and Gan, 2020).

From the structural perspective, FDHs are required to work and live in the employer's residence (Immigration Department, 2003). The live-in arrangement blurs the boundary between work and home and is conducive to long working hours, overloading of tasks, and disruption of resting time (Cheng, 2003; Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Lai and Fong, 2020). Specifically, more than 95% of FDHs in Hong Kong are employed as the sole domestic worker in the household (Census Statistics Department, 2021b). The isolated occupational environment without the presence of co-workers may increase FDHs' difficulties in negotiating a separation of time on and time off (Lai and Fong, 2020). Furthermore, many FDHs in Hong Kong do not have a private room in the house (Mission for Migrant Workers, 2022). This is either because the family has a confined living space, which is common in Hong Kong, or because the FDHs are asked to share a room with the care recipients (Lan, 2003; Lai and Fong, 2020). The removal of the spatial distances between FDHs and the employer's family exposes the former to constant surveillance and creates the expectation of round-the-clock presence (Lan, 2003; Yeoh and Huang, 2010). The workers' lack of control over time, space, privacy, and their bodies may eventually develop into sleep deprivation, loneliness, depression, stress disorders, fatigue, injuries, and other physical and psychological health problems (Malhotra et al., 2013; Bernadas, 2015). Poor performance due to any of the health issues could in turn provoke the employer's aggressive and violent reaction against the domestic workers, resulting in the reproduction of a hazardous workplace (Lai and Fong, 2020).

Besides the spatial settings of the workplace, the state's immigration and labor policies may reinforce power inequities in the employer–employee relations and subject FDHs to exploitation and abuse (Bernadas, 2015; Parreñas et al., 2021). In Hong Kong, FDHs' legal residency is bound to their employment contracts. Applications for change of employer within the first two-year contract “will not normally be approved” (Immigration Department, 2022, p. 4). The immigration policy excludes FDHs from eligibility for permanent residence regardless of the number of continuous years they work here (Immigration Ordinance Cap, 2021). Upon the completion or termination of the employment contract, FDHs are required to leave Hong Kong within 14 days unless they can find a new employer during the two-week period (Labour Department, 2022). Furthermore, Hong Kong has no regulation on statutory maximum working hours. Together, the policies are prone to create “unfree laborers” who are locked in their contract and are pressured to accept working conditions that are detrimental to their health (Parreñas et al., 2021, p. 4671).

From the cultural perspective, racial and occupational discrimination may interact with the structural factors to exacerbate FDHs' vulnerability to workplace hazards (Ullah, 2015). FDHs' ethnic minority status, low-wage occupation, limited local language proficiency, and unfamiliarity with cultural practices in the host society may marginalize them into the “cultural other” (Ladegaard, 2013, p. 138) and cultivate employer discrimination against them (Chiu and Asian Migrant Centre, 2005; Ullah, 2015; Liao and Gan, 2020). For instance, in the ethnic Chinese-dominant society of Hong Kong, although half of the population speaks English, Cantonese is the dominant language used at home and in everyday life (Census Statistics Department, 2017). Filipino workers can speak English—a national language in the Philippines—to their employers. However, they still need Cantonese-speaking skills to communicate with children and older family members. Alternatively, most Indonesian workers only use Cantonese to communicate with their employers and family members (Legislative Council Secretariat, 2017). While most FDHs only have low to medium levels of local language proficiency, the language barriers could result in misunderstanding, bias, and subsequent maltreatment (Liao and Gan, 2020).

Past research has provided extensive analyses of how structural and cultural factors transform FDHs' workplace into a potential locus of health hazards (Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Ullah, 2015; Kaur-Gill et al., 2021; Parreñas et al., 2021). There is also evidence to support the relationship between FDHs' workplace settings and aggression and violence emanating from the employers (Lai and Fong, 2020). While considerable attention has been given to influencing factors at the macro level, little is known about how FDHs exert agency to handle workplace hazards on a day-to-day basis. Among the available studies that have examined FDHs' strategies for workplace health management, most have focused on social support, which involves engaging external sources to acquire assistance and resources (Oktavianus and Lin, 2021; Piocos et al., 2022). It is worth exploring how FDHs address abuse and exploitation using internal resources when seeking help from others is not a preferred option given their muted status. Thus, this study seeks to explore both the coping and support-seeking strategies used by FDHs to understand their ways of dealing with health hazards within the structural confines of their employment.

Coping and social support

Coping and social support are two types of personal resources that can ease a person's adaptation and psychological wellbeing (Hsu and Tung, 2010). Coping, as the internal personal resource, involves one's cognitive or behavioral effort to manage stress and demands (Roohafza et al., 2014). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) identified two types of coping styles: problem-based and emotion-based. Problem-based coping involves problem identification and problem solving through the process of removing, altering, or reducing the cause of stress. Emotion-based coping focuses on regulating emotional responses toward stressors, which include strategies such as selective attention, meaning-making, mental or behavioral disengagement, and seeking emotional support from others. Currently, limited knowledge is available regarding the strategies used by FDHs to cope with exploitation and abuse (Østbye et al., 2013; Tam et al., 2018). Coping may play a particularly critical role in FDHs' health management as the structural conditions of their employment are likely to isolate them from external help sources and pressure them to rely only on internal personal resources to handle workplace hardships. This highlights the importance of exploring coping from the FDHs' perspective.

Social support, as the external personal resource, can be examined from a perceptual perspective, which focuses on individuals' perceptions of the availability of general or specific support resources from others (Reinhardt et al., 2006). Support can also be examined from a functional perspective, which attends to the functions of social support in enhancing health. Support functions can be further divided into three types: emotional support, informational support, and instrumental support (Goldsmith and Albrecht, 2011). Emotional support refers to affection that provides empathy, caring, love, and trust. Informational support involves the transmission of useful or needed information in the form of advice, guidance, input, or suggestions. Instrumental support emphasizes aids in kind, including money, time, labor, and modification of the environment. The three support functions are not discrete. For instance, while instrumental support may consist of actions that provide physical help, it can also generate a feeling of emotional support to the receiver.

A review of the literature indicates that social support is beneficial to migrant workers' physical and psychological health (Kuo and Tsai, 1986; Noh and Kaspar, 2003; Baig and Chang, 2020). Social support can create buffers to mitigate the adverse impacts of stress on health (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al., 2006; Chou, 2012). It can also have direct impacts on health by enhancing migrant workers' psychological states (e.g., a sense of connection and self-worth) and by improving their physical conditions through the provision of tangible aids (Oktavianus and Lin, 2021).

However, social support deficiency could be a problem among FDHs since most of them have migrated alone and lack strong-tie support networks consisting of family members and close friends in the host countries (Lin and Sun, 2010). Previous research indicated that FDHs seldom communicate their support needs with close kin back home because they do not want the latter to worry or offer unhelpful advice (McKay, 2007; Piocos et al., 2022). Instead, FDHs in Hong Kong may seek informational support from local community organizations, fellow migrant workers, or their employers to acquire health tips and advice on ways of accessing health services (Oktavianus and Lin, 2021; Piocos et al., 2022). When facing serious health challenges, such as COVID-19 virus, seeking emotional support from other FDHs and community organizations helps FDHs release negative feelings and gain a sense of companionship. Instrumental support from community organizations, such as assistance in acquiring protective materials, can also generate a positive impact on FDHs' physical and psychological health (Oktavianus and Lin, 2021). Despite these studies of social support for general health, less is known about Hong Kong FDHs' support needs from different sources and the health benefits of different support functions in circumstances of exploitation and abuse. Furthermore, empirical evidence shows that Hong Kong FDHs' frequency of support seeking is low (Baig and Chang, 2020). FDHs' infrequent engagement with support sources suggests that social support may only represent one aspect of their approach to managing abuse and exploitation. An exploration of their use of both internal personal resources (i.e., coping) and external personal resources (i.e., social support) may offer more insights into their ways of addressing health hazards at work.

Altogether, previous studies have analyzed how the employment conditions of domestic work foster power inequalities and violence in the workplace (Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Lai and Fong, 2020; Parreñas et al., 2021). More research can be done to specify the types of exploitation and abuse that Hong Kong FDHs experience in their work life. Moreover, while FDHs' voices have long been muted in the workplace as well as in the public discourse (Kaur-Gill et al., 2021), it is important to foreground their voices about how they combine the use of coping and support resources to maintain their wellbeing in hazardous work environments. Accordingly, this study raised the following research questions:

RQ1: What are FDHs' experiences with abuse and exploitation?

RQ2: What are the coping and support-seeking strategies that FDHs use to deal with abuse and exploitation?

Methods

Given the limited studies of FDH workplace hazards in Hong Kong at the time the study was conducted, we adopted a mixed-method design that incorporated a quantitative survey and in-depth interviews. The survey helped identify forms of abuse and exploitation that Hong Kong FDHs experienced at work, the importance of different support sources and support functions in the migrant workers' experiences with abuse and exploitation, and their preferred coping strategies. The in-depth interviews, which provided the major findings of this study, helped develop a deeper understanding of reasons behind exploitation and abuse and participants' views regarding their coping and support-seeking strategies for dealing with workplace hazards. This mixed-method design allowed us to converge and compare results from different forms of data and enabled between-method triangulation of the data to enhance the validity of the results (Creswell and Creswell, 2017).

A university's research ethics committee approved the project. All participants were FDHs working in Hong Kong. The data collection period was between February and April 2019. The first and third authors recruited survey and interview participants from common FDH meet-up areas (e.g., public spaces and parks) from five different districts of Hong Kong, including Kowloon Tong, Mong Kok, Central, Tsuen Wan, and Tsim Sha Tsui. Maximum variation sampling was used to obtain a sample diverse in demographics, work experience, and types of families for which FDHs worked (Suri, 2011). As most FDHs have only one free day per week, data collection was only performed on Sundays, the typical day off for FDHs. Ultimately, 200 FDHs were contacted. Among them, 118 took part in the survey and 106 completed the questionnaire. Eighteen survey participants subsequently agreed to be our interview participants. Another three FDHs participated in the interviews only. In total, there were 106 valid cases for the survey and 21 valid cases for the interviews.

Survey

Data collection

The first and third author conducted face-to-face surveys with FDHs using paper-and-pencil questionnaires and an online survey platform through Qualtrics on an iPad. The survey questionnaire was in three languages: English, Tagalog, and Bahasa Indonesia. All questions were created in English and then translated into Tagalog and Bahasa Indonesia with assistance from native speakers.

Measures

The questionnaire comprised seven demographic questions and 34 items measuring abuse, exploitation, coping strategies, support sources, and support functions.

Demographics

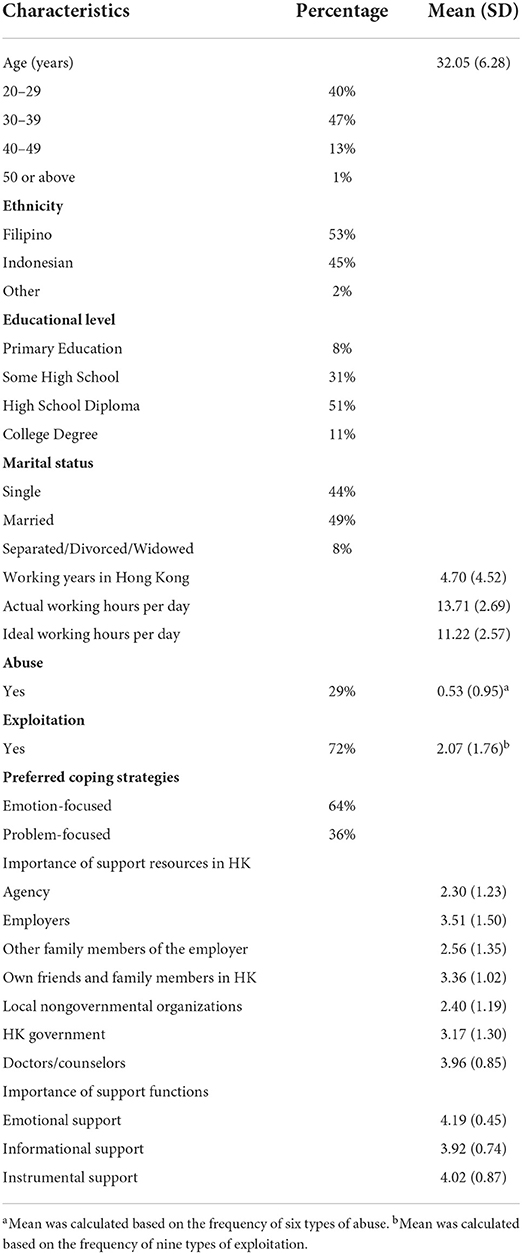

Participants were asked to report demographic information including age, ethnicity, highest education degree, marital status, years of working in Hong Kong, actual working hours per day, and ideal working hours per day. Most participants came from the Philippines (53%) and Indonesia (45%). Their average age was 32.05 (SD = 6.28) and they had worked in Hong Kong for an average of 4.70 years (SD = 4.52). Close to 40% of them had primary education or some high school, 51% held a high school diploma, and the other 11% had a college degree. On average, their actual working hours per day were 13.71 h (SD = 2.69), which was higher than the ideal of 11.22 h (SD = 2.57).

Abuse

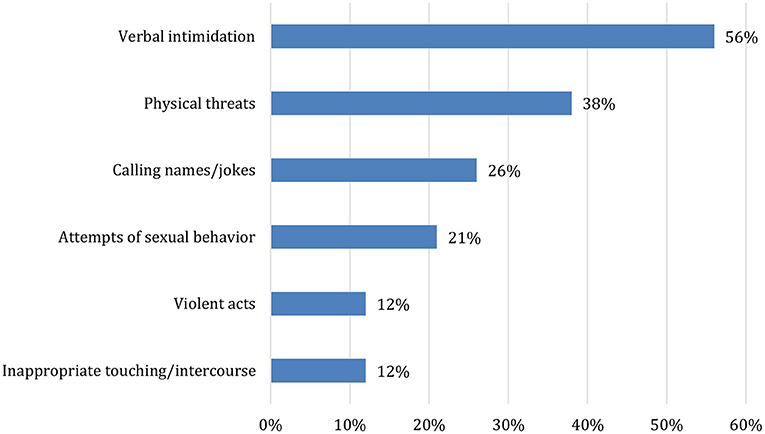

Based on the definition of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2008), six questions were developed to measure abuse using a dichotomous scale (1 = yes; 0 = no). Physical abuse was measured using two items: “I have been physically injured by the acts of violence of my employer or his/her family members” and “I have been intimidated or threatened by the physical actions of my employer or his/her family members.” Verbal abuse was measured using two items: “I have been verbally intimidated or threatened by my employer or his/her family members” and “My employer or his/her family members have made jokes about me and called me names and terms I did not like.” Another two items were used to measure sexual abuse: “I have experienced attempts of a sexual nature from my employer or his/her family members without my consent” and “I have experienced forced and inappropriate touching and/or even sexual intercourse.” The reliability of the six items was low (Cronbach's α = 0.57), indicating that participants' experiences with different types of abuse varied. The sum of the six items was first calculated (M = 0.53, SD = 0.95) and then recoded to generate a composite variable, with 1 indicating experiencing at least one type of abuse and 0 indicating no experience.

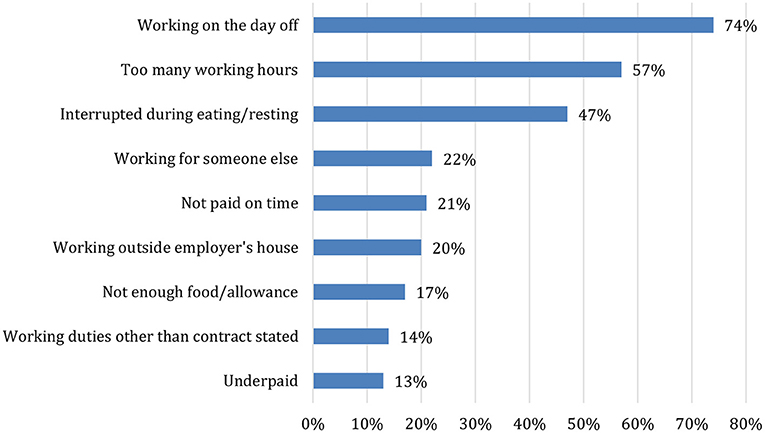

Exploitation

Nine items adapted from a 2014 Amnesty International study were used to measure exploitation using a dichotomous scale (1 = yes; 0 = no). Sample questions included: “I have been asked to work even if I was on my regular day off”; “I don't get paid on time”; “I am not offered enough food/food allowance”; and “I have worked duties other than what my contract has stated.” The inter-item reliability was 0.60, indicating an inconsistency in participants' experiences with different types of exploitation. The sum of the nine items was first calculated (M = 2.07, SD = 1.76) and then recoded to generate a composite variable, with 1 indicating experiencing at least one type of exploitation and 0 indicating no experience.

Coping strategies

Based on Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) categorization, participants were asked: “In what way do you tend to deal with workplace conflicts and problems?” Two options were provided to measure their use of problem-based coping or emotion-based coping: “I try to tackle the problems” and “I try to manage my feelings and emotions.”

Support sources

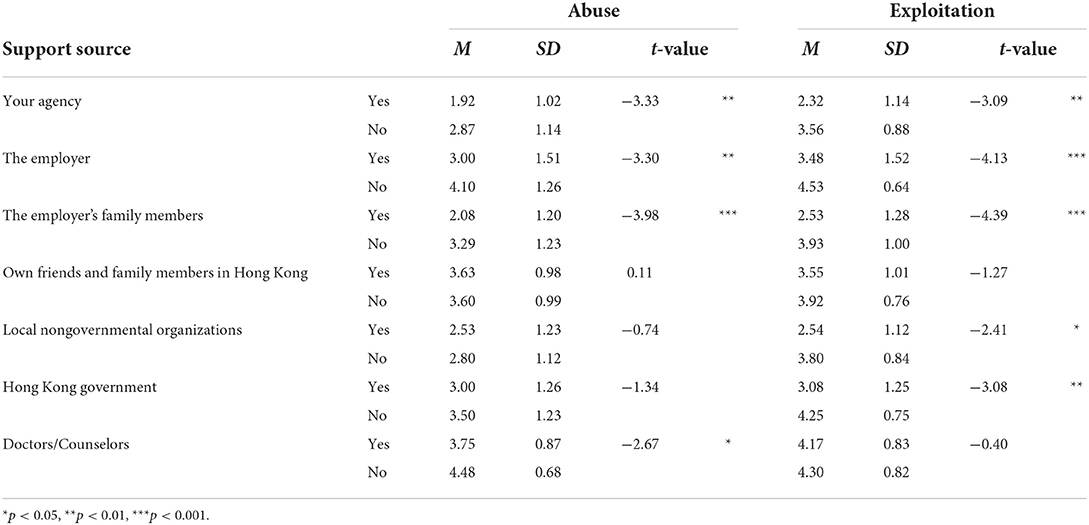

Participants were asked to assess the importance of support in dealing with problems of abuse and exploitation from seven sources: “your agency, employers, other family members of the employer, own friends and family members in Hong Kong, local nongovernmental organizations, Hong Kong government, and doctors/counselors” (1 = not at all important; 5 = extremely important). The reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.63) showed an inconsistency in participants' perceptions of different support sources. Thus, we treated support sources as separate variables in subsequent analyses.

Support functions

Eleven items were adapted from Sherbourne and Stewart's (1991) social-support scales. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each support function in dealing with problems of abuse and exploitation on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all important; 5 = extremely important). Sample questions included: “Make me feel loved and accepted” (emotional support, M = 4.19, SD = 0.45, Cronbach's α = 0.60); “suggest activities that distract me” (informational support, M = 3.92, SD = 0.74, Cronbach's α = 0.61); and “take care of things for me” (instrumental support, M = 4.02, SD = 0.87, Cronbach's α = 0.78).

Results

The survey provided preliminary information about FDHs' experience with abuse and exploitation that guided the interview design. Table 1 summarizes the results of descriptive analysis. Among the 106 survey participants, 29% of them (N = 34) reported experiencing at least one form of abuse (Figure 1). Among those who experienced abuse, verbal threats and intimidation were reported most often (56%), followed by threatening physical actions (38%), and calling names (26%). Alarmingly, seven participants (21%) reported experiencing attempts of sexual behavior in the work environment and four reported experiencing inappropriate touching (12%). Exploitation (M = 2.07, SD = 1.76) occurred more frequently than abuse (M = 0.53, SD =0.95). Seventy-two percent of the participants (N = 76) reported experiencing at least one form of exploitation (Figure 2). Among them, the top three forms of exploitation were all related to time exploitation, including asking participants to work on their day off (74%), for longer hours (57%), and while they were resting or eating (47%).

To explore how abuse and exploitation were related to FDHs' selection of coping strategies, chi-square tests of independence were performed. A significant relationship between abuse and coping strategies was found. Those who experienced at least one type of abuse preferred emotion-based coping (81%) more than problem-based coping (19%) compared to those without abuse experience (χ2 = 5.96, p < 0.05). Those who experienced exploitation also preferred emotion-based coping (69%) more than problem-based coping (31%). However, such a relationship did not achieve statistical significance (χ 2 = 2.83, p > 0.05).

To gain a better understanding of FDHs' assessments of support sources and support functions by their experience with abuse and exploitation, independent sample t-tests were performed. Table 2 showed that those who were abused were less likely to consider their agency (t = –3.33, p < 0.01), their employer (t = –3.30, p < 0.01), the employer's family members (t = –3.98, p < 0.001), and doctors and counselors (t = –2.67, p < 0.05) important support sources than those who were not abused. Those who experienced exploitation were less likely to rate their agency (t = –3.09, p < 0.01), their employer (t = –4.13, p < 0.001), the employer's family members (t = –4.39, p < 0.001), nongovernmental organizations (t = −2.41, p < 0.05), and the Hong Kong government (t = –3.08, p < 0.01) as important support sources than those who were not exploited.

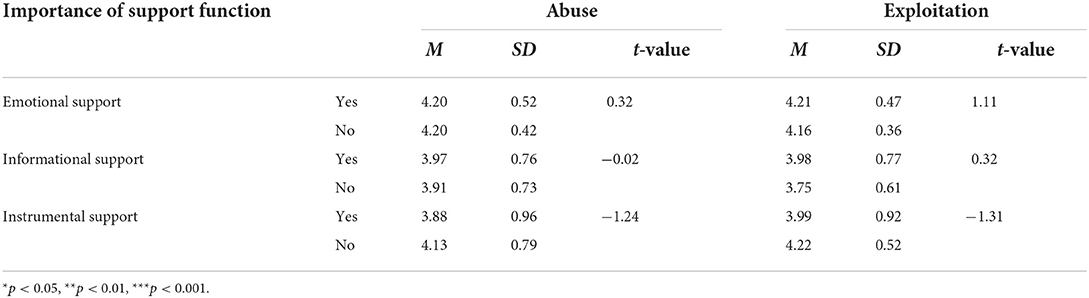

Finally, independent sample t-tests were performed to test whether abuse and exploitation had an impact on participants' perceptions of the importance of social support. Table 3 showed that regardless of their experience with abuse and exploitation, participants recognized the importance of emotional, informational, and instrumental support in dealing with workplace hardships.

In sum, the survey results provided basic information about participants' common experience with abuse and exploitation, their preferred use of emotion-based coping over problem-based coping, and the perceived unimportance of support from agencies, employers, and employers' family members. These findings were examined more deeply through the analysis of the interview study.

In-depth interviews

Procedure

The first and third authors conducted semi-structured interviews with 21 participants who experienced abuse or exploitation among the 200 FDHs we contacted. All participants were female, aged 30–45 years. Nineteen of them were Filipinos and two were Indonesians. The interviews were conducted in Cantonese and English and lasted between 25 and 40 min. Each interview participant received grocery coupons worth HK$100 in appreciation of their time.

A semi-structured interview protocol was used to guide data collection based on the theoretical framework and allow extended probing (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). The protocol contained four types of questions: general background (e.g., demographics); evaluation of relationships with the employer and the employer's family members (e.g., “How would you describe your relationship with your employers and their family members?”); experiences with abuse and exploitation (e.g., “Could you share with us how you were abused?”, “How did you react immediately to the abuse?”, “How did you react afterwards?”); and the role of social support and coping in dealing with abuse and exploitation (e.g., “Did you seek help from anyone?”, “Have you ever talked to anyone, such as friends, other family members from the household, the police, or an NGO, about your situation?”).

All interviews were conducted at the site where participants were recruited to minimize any disruption of their resting time. The interviewers were two female undergraduate students, whose younger age and gender helped mitigate power distance and gain trust from the interviewees. As all participants were interviewed in public places surrounded by their communities, the physical setting offered an additional sense of social protection. After 21 interviews, we observed repeated expressions and could not identify new ideas emerging from the data. Thus, we decided that data saturation was achieved, both based on our assessments of data properties and extant guidelines on sample sizes (Braun and Clarke, 2022; Hennink and Kaiser, 2022).

Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in Cantonese and English verbatim before translating into English for data analysis. With the research questions in mind, we performed theoretical thematic analysis to identify codes and themes around the theoretical concepts of abuse, exploitation, social support, and coping that were of interest to our research (Braun and Clarke, 2006). To be reflexive in data analysis, we attended to both the patterns of participant sense-making of theoretical concepts and the latent meanings of their experiences emerging from the data (Braun and Clarke, 2022).

We began the coding process with reading and re-reading the transcripts and line-by-line coding by marking each segment of the text that was related to the theoretical concepts. We then clustered recurring phrases and ideas into categories and potential themes. Finally, we finalized the overarching themes through reiterative comparisons and discussions among the authors. Table 4 shows the relevance between the theoretical concepts, sample codes, subthemes, and the finalized major themes. Participant validation—i.e., sharing findings from earlier interviews with later participants to ask for their validation and additional accounts—and between-method triangulation—i.e., triangulating our survey results with the interview findings—were used to increase the credibility of the results (Creswell and Creswell, 2017; Braun and Clarke, 2022).

Findings

Four major themes were extracted from the interview data. The first two themes described participants' experiences with abuse and exploitation. The third and fourth themes addressed the coping and support-seeking strategies they used.

Underlying reasons for workplace abuse

The first theme captured different types of workplace conflicts that FDHs encountered and were subsequently developed into abuse. The interview data revealed that verbal and physical abuse was related to participants' role as non-family caregivers who cared for children and the elderly and took the burden of the employers' emotions. Most participants shared that they were hired as caregivers to look after older members aged 80 and above who suffered from illnesses, such as dementia, or children aged from a few months old to under 15. The high demands on caregiving and conflicting orders from different family members became a major source of tension, leading to verbal and physical abuse. One participant recalled her experience of caring for an older person suffering from dementia:

Funny thing about the elderly. He would suddenly feel like he is powerful, he is very manly and capable. “I don't need a helper. I don't need you!” But he could actually barely move by himself. I cried all the time because of that. I would hide away and cry. It was the most difficult job I have ever had.

Another participant echoed:

The problem with the elderly, especially with his dementia, is that his memory is flaky and unstable, like he used to scold me all the time, saying that I was paid even better than him working at construction sites. I used to take care of another old lady, and she was worse. She always shouted at me with bad words, saying that there was something going on with me and her husband, but her husband passed away a long time ago.

Many caregivers worked with the employers' family members instead of the employers themselves. Conflicts occurred when participants were instructed by their employers to perform caregiving tasks but their attempts were rejected by the family members. Verbal abuse occurred through the use of bad words when the older members had cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia), when participants did not have equal power status to interact with them, or both.

Similarly, FDHs shared the responsibility of educating the children they were looking after, and this could turn into another reason for vigorous conflict and abuse. Participants shared that it was common for the children to disobey them, knowing that they were giving orders on behalf of their own parents. One participant recalled:

He would not eat his meal if I let him watch TV. So I would only allow it after he finished his meal, and he was angry about it. He would then ask to call his mother and I would hide the phone away.

The child eventually threatened to hit the participant with a chair. This was when physical abuse and verbal abuse like name-calling and cursing happened.

It was also common that the employers used FDHs as an emotional outlet for their own stress. Participants shared their experiences of being scolded and shouted at, “for no specific reasons,” simply because the employers were “just not in the mood” or “maybe she is being treated badly at work.” Other participants shared the experiences of being scolded by the employer who had to endure the stress of taking care of an ill parent:

It really was a difficult time for her and her father [with dementia], with her depression going on. She would just call my name, and I'd be like “Yes, ma'am,” and she would just go off and scold me. I don't even know what she was talking about.

The responsibility of being the emotional outlet sometimes resulted in disrespectful and abusive behaviors. Participants reported experiencing intimidating physical behaviors such as having a door slammed in their faces, being scolded and hit on the upper back, and being poked in the forehead. One participant gave this example:

Maybe something happened at work. She doesn't always get mad at home. It's like “bang!” [action of door slamming]. Sometimes she does this [action of slapping on the back of the head] from behind. And also this [action of poking].

Standing by 24/7

The second theme revealed participant experience with exploitation due to the live-in work arrangement. All participants shared that they suffered from time exploitation. The most common form of time exploitation was not having enough time during their day off. Additionally, the long working hours affected the quantity and quality of their resting time, which subsequently developed into a source of workplace distress.

Having 1day off per week meant a lot to participants. Particularly those caring for persons with dementia needed the break to relax and hang out with friends. One participant described it this way: “After 1 week of that hard work comes a small break. We can finally let loose and relax. This will make it easier, less like being in jail.” Participants shared that they could not spend their day off at home. “I will just get ordered around doing things.”

However, all participants stated that they never had a day off that lasted for 24 h as stated in the law. Most participants shared that even on their day off, they only left the house after their morning duties. For those who looked after older people or children, they were required to cook breakfast, drop off the children at their extracurricular activities before leaving for their actual day off, meaning their time off only started after 10 am. Furthermore, what time they had to come home also depended on the employers. Some participants pointed out that their employers would ask them to come home at a certain time to attend to duties such as cooking dinner for the elderly, preparing their uniforms for work, washing dishes, and finishing up the cleaning and preparation for the next day. One participant described her condition:

Usually if my mum [employer] does not ask me to stay, I'll leave at 7 am. If my mum asks me to be back at 3, I will go home. I will not have the whole day off. It is cut off.

Another participant shared how her days off were shortened:

My first time having a day off, my employer asked me to be home by 8 pm. But then I was late. I was late because it was so far away and I did not know the directions. It was my first time taking the Mass Transit Railway (MTR), and I did not know the way home. So I was half an hour late. Then the second time, I was asked to be home before 7 pm. And if I was ever late again, I'd have to be home by 6 pm.

Besides working on their day off, participants shared how working extra hours to cover household chores reduced their resting time during weekdays. Some pointed out that their employers were thoughtful enough to let them go to bed early, allowing them to leave the work until the following day. Yet they would not feel at ease even though it was allowed. Responses around this included: “I can't sleep knowing I did not finish my work. I would feel very uncomfortable,” and “I'd have to deal with it tomorrow, anyway.” Together, the explicit requirements from the employers and the internalization of work requirements made participants feel like they had to be on standby 24/7, and thus they rarely had a good rest.

It is what it is

The third theme revealed the mindsets underpinning participants' responses to workplace problems. Participants shared the tendency to accept adverse working conditions as normal in their work life. This perception shaped their coping strategies. Acceptance of the working conditions, avoidance of negotiation, and withholding were ways for participants to deal with hardships at work. Accordingly, they sought emotional support from religion or friends to withstand the stress and negative emotions.

A shared point of view was that workplace conflicts were the norm. “Just deal with it. All bosses are the same. Wherever you go, it is the same.” When asked about whether they would communicate with their employers about workplace problems such as breach of contract, the responses were similar: “It's always like that,” “This is work after all,” and “It's all the same.” Participants believed that there was not much they could do, regardless of how bad their situations were. Accordingly, they tended to isolate their personal feelings from work to avoid being distressed. One participant explained her way of dealing with hardship at work by saying, “I'm fine with it all. I don't think about it at all. As long as I get paid, I'm fine with anything.”

To some participants, the avoidance of communication was due to the fact that they recognized their employers' hands were also tied (e.g., caring for a family member with dementia). To others, refusal to negotiate with their employer was associated with the sense of powerlessness and the fear of being sent back home. Even those who covered work beyond household chores, such as washing the employer's minibuses for commercial use or helping at the employer's herb shop to manually cut hard substances like dried ginseng, accepted the assignment without an attempt to negotiate with their employer. One participant repeatedly mentioned: “I'm scared. I never say anything; I can't say it. Even if the food is not enough, I won't say anything.” This participant got only one egg for her breakfast and usually did not get paid on time. Yet she did not feel she could go to her employer because she was frightened by the consequences.

Accordingly, the most common verb used by our participants to explain their coping with stress was “withhold.” Participants believed that according to the work norms they had no choice but to accept the situation as it is. The majority of our participants mentioned that they were “used to it,” and considered their workplace problems “acceptable.” One participant explained: “Just let it be. It will be fine eventually, with time.” This reflected their focus on emotion management as the preferred way to cope with problems.

Consequently, it was common for participants to seek emotional support from external sources. With most of our participants being religious (the Indonesian participants were Muslims, and most Filipinos participants were Catholics), they considered praying as one of the most effective ways of helping them cope with stress. Praying was incorporated into their daily routine, and some even considered it the most important source of support. This finding extended beyond the survey results. One participant explained how she felt that praying was even more useful than talking things out with friends: “There is nothing like praying, because when we pray, we believe that God will look after us. Whatever happens, God knows, and he will help us out.” The belief that they were being looked after by God helped alleviate stress and gave participants strength to manage negative emotions. From a religious perspective, the good things in life are gifts from God, and the bad things are tests of life or their faith. Such a worldview eased participants' acceptance of their work conditions as it is.

Besides religion, friends were a major source of emotional support. Most participants mentioned that it was helpful to meet with friends at their Sunday gatherings. A common form of emotional support from friends was empathy. As one participant explained, “She understood. She was also looking after an older person. We were in the exact same situation, so she understood. Actually, she might be going through worse.” The participant stressed that most of her friends caring for older persons with serious illnesses were just as “miserable” as she was. Their similar experiences yielded empathy, but also normalized the acceptance of difficult work conditions. Notably, many participants mentioned that when they were out with friends, they unanimously left out work-related topics. Instead of detailing their difficulties and seeking advice from others, they preferred to utilize the time to enjoy each other's company. Emotional support was perceived to be more important than informational support from peers.

Likewise, family support was present in an implicit way. Participants came to Hong Kong to provide a better living for their family back home. Family was their major motivation and distractions from stress. However, when they called their family, they would not complain about work and seek advice. In fact, many participants did not want to mention work at all. “I don't want them to worry” was the theme shared by participants. As one participant said, “If I am talking with my family, I don't really mention difficulties at work because I don't want them to worry. If they ever ask about that, like ‘How's work?' I'll say, ‘Oh it's great!' [laughs].”

Like family, like friends

The final theme revealed participants' descriptions and expectations of ideal employer–employee relationships. While all participants had experienced some abuse or exploitation during their previous or current employment, the interview data revealed that their employers had the potential to provide all three types of support—emotional, instrumental, and informational—that they needed.

Employers could be an important source of emotional support. Some participants replied that they often chatted with their employers, and the conversations were not limited to giving and receiving orders but also might include other casual topics. For instance, one participant mentioned that her employer was particularly encouraging and motivated her to learn cooking, which was something she was passionate about. The encouragement and warmth that participants experienced enhanced their job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing. For those who cared for frail older adults, emotional support from the employers was helpful in mitigating caregiving stress, as one participant shared:

He [the older person with dementia] would never try to make you feel better. Except for my madam [employer]. When madam saw me upset and stressed out, she would buy me chocolate. That is how I got through that contract.

Emotional support could also be delivered through employers' appreciation and praises. One participant quoted her employer as saying, “We're so thankful to have you. You're such a nice helper.” Such support from employers was vital to the participants' endurance of hardships at work. Notably, the most supportive relationship that participants experienced was to be “like friends” or “like family.” As one participant shared: “Yeah, she is very nice to me. She treated me like family.” When being treated as an inseparable part of the family, participants felt their need for recognition and self-worth fulfilled.

Instrumental support from the employers was presented in the forms of resolving conflicts between FDHs and the employer's family members and offering medical and financial assistance. When conflicts involved communication with children or caring for older adults, most participants mentioned that they would go to their employers for assistance, and the latter would step in and resolve the situation by talking it through with the elderly or giving direct orders for the kids to listen to their helpers. The employer's instrumental support could be helpful in reducing the participant's vulnerability to abuse committed by family members.

Some participants received medical assistance from their employers, who might purchase medicine for them or take them to the hospital. Participants appreciated this instrumental support when they were ill in a foreign land. One participant shared that she could talk about her personal health conditions and gained medical assistance from her employer: “My doctor, uh, my employer, said you need to take medicine for the contraceptives so I would not get pregnant.” Another type of instrumental support was reflected in the extra money that some participants gained by doing work not stated in the contract, such as cleaning the house of the employer's other family members. “She asked me to go and clean her mother's house, and she would pay extra, like the wage of a day.” Differing from exploitation, which involved forcing the workers to do additional work without payment, a little extra money like this provided financial aid and was welcomed by participants.

Informational support included advice and suggestions about health, daily living, and assimilating to life in Hong Kong. Some participants shared how their employers would give them health advice, such as to go to bed early and attend to their diet and physical activity. One participant mentioned that her employer shared information about FDH abuse and ways to protect herself when he saw the news reporting similar issues. However, compared to emotional and instrumental support, the importance of informational support was less discussed by participants.

In sum, employers can be the source of distress or support capable of intervening in family members' abusive behaviors and fulfilling FDHs' needs for survival and recognition. The aid they provided to FDHs—particularly by offering emotional support—could critically boost FDHs' wellbeing in the employment conditions.

Discussion

Using a mixed-method design, this study examines FDHs' experience with abuse and exploitation and their use of coping and support resources to address health hazards at work. The survey yielded three results: (1) verbal threats and time exploitation are the most common forms of abuse and exploitation; (2) emotion-based coping is preferred over problem-based coping; and (3) the abused and the exploited rated employers and their family members low in importance of support. The interview findings resonate with the first two points and reveal nuances in FDHs' interactions with their employers and the coping and support resources they look for.

Both the quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that the most common form of abuse is verbal abuse, which includes verbal threats, shouting, scolding, and cursing. The interview findings further illustrate that although verbal abuse may come from the employers, most of the time the perpetrators are children and older family members. The employers would intervene in family members' abusive behaviors. However, particularly for those who care for persons with dementia, increased caregiving distress becomes unavoidable as the patients' syndrome progresses. Past studies indicated that family caregivers hire FDHs as the coping strategy to deal with caregiver distress (Ha et al., 2018; Basnyat and Chang, 2021). Our findings reveal that the caregiving stress mainly shifts from family caregivers to the hired non-family caregivers (i.e., the FDHs) rather than being effectively removed in home-care settings. Differing from previous research on precarious domestic work that mostly focused on employer aggression and violence (Ullah, 2015; Lai and Fong, 2020), our findings provide new information about how workplace hazards may come from the care recipients due to their deliberate practices or cognitive impairments. Either way, FDHs' susceptibility is tied to the tasks they are asked to perform within the employment structure.

Likewise, our study affirms the link between workplace settings and exploitation speculated in previous studies of precarious migration (Yeoh and Huang, 2010; Parreñas et al., 2021). The live-in arrangement creates the expectation of constant availability of service. As a result, time exploitation, which includes excessively long working hours, shortened rest days, and the need to stand by around the clock, is identified as the most common form of exploitation that FDHs experience. Our findings provide additional empirical evidence for how the employers can reinforce their control over FDHs and normalize the maximum use of the latter's labor through the structural settings of the live-in arrangement.

Our study also illustrates that FDHs are aware of their unfree status. However, they tend to conform to the asymmetrical power relations instead of negotiating with their employers. Orbe (1998) argued that nondominant groups may consider different contextual factors, such as the communication impacts on their group status, communicative orientations, and costs and rewards, when deciding their ways to interact with the dominant group. In the context of FDH employment in Hong Kong, the immigration policy eliminates FDHs' opportunity to become citizens and integrate into a culturally pluralistic society (Bernadas, 2015). Their group status is doomed to be separate from others. Yet their employment status denies any possibility to be fully disengaged from the dominant groups. Thus, the only way for them to fit in is to live by the dominant rules and accept their muted group status in the society (Orbe, 1998). Moreover, since FDHs' migration is fundamentally driven by financial reasons (Malhotra et al., 2013; Liao and Gan, 2020), they are unlikely to take aggressive communication orientations and confront their employers. The costs for breaking their dependence on the employers, which include losing their job and being sent back home, are too high for most to afford. The lack of positions to communicate with the employers may explain why most FDHs stay nonconfrontational and silent when workplace hazards occur (Cheung et al., 2019; Lai and Fong, 2020).

As open communication is inhibited, it is unsurprising that FDHs are prone to adopt emotion-based coping when encountering abuse and exploitation. This tendency is better illustrated in the qualitative findings. Acceptance, avoidance of confrontation, and viewing workplace conflicts as norms are common strategies used by FDHs to manage their emotions. Alternatively, problem-based coping is only adopted when FDHs try to resolve conflicts between them and care recipients through the employers. Our findings add insights into why abuse and exploitation cases are underreported (Cheung et al., 2019). When conflicts arise between FDHs and their employers, they submit to whatever work is assigned to them and avoid negotiating with their employers. The preference of emotion-based coping over problem-based coping demonstrates these workers' ways of adapting to the dominant structures and their endeavors to help their family back home by prolonging their stay in Hong Kong (McKay, 2007).

Since FDHs focus more on emotion management instead of problem-solving when encountering occupational hazards, they also report a stronger need for emotional support than for other support functions. The interview findings reveal the importance of emotional support in FDHs' work life. When seeking emotional support through prayer, they look for spiritual content and positive meaning-making of their work life. When looking for emotional support from friends, they prefer to use the limited resting time to enjoy each other's company rather than to complain about difficulties or about work conditions. When talking to their families back home, they avoid giving family members the opportunity to express concerns about their working and living conditions. Emotional support is acquired through the very presence of loved ones on the phone. Finally, the emotional support that FDHs need from employers is appreciation and recognition that provide buffers against caregiving stress. Findings from our study contribute to a better understanding of the various facets of emotional support and the functions of different support sources in enhancing FDHs' resistance to work-related distress. Agency is demonstrated in their engagement with external sources to acquire emotional strength and foster health self-management. However, inherent in their reliance on emotional support and emotion-based coping is the difficulty of communicating about work and the passive acceptance of their marginalized group status in the Hong Kong society (Orbe, 1998).

Finally, the quantitative findings of perceived low importance of employer support among the abused and the exploited and the qualitative findings of the importance of employer recognition suggest that although employers can potentially be a critical source of support, in reality such support is often absent. In the live-in work environment, FDHs work closely with their employers and rely on the latter to moderate their relationships with other family members. Concurrently, the employers rely on FDHs to share caregiving responsibilities. When positive dynamics exist, the employer and the FDH develop a quasi-family relationship and provide mutual support to each other (Ho et al., 2018). However, even if FDHs expect reciprocity in support, they are hesitant to seek support from their employers within the unbalanced power relations. Employer support is communicated top-down instead of bottom-up during the process. If the employer does not take the initiative, the dynamics can easily fall into a mutual reinforcement between FDHs' sense of powerlessness and their silent acceptance of subalternity in the employment structure.

Implications

This study foregrounds the perspective of FDHs and provides a space for members of this marginalized group to voice their seldom-heard experiences and concerns. Our findings have some practical implications that may offer insights into improving FDHs' quality of work life. First, while the rates of exploitation and abuse are alarmingly high, most workers do not know how to protect their rights and negotiate with their employers when workplace hazards occur. At the same time, they have a community ready to offer instrumental and informational aid beyond emotional support. Sunday gatherings are important sites for FDHs to expand their support networks and acquire needed resources. More outreach programs through Sunday gatherings may help improve FDHs' awareness of and access to resources available in Hong Kong.

Second, although employers could be a critical source of support, their support is often absent or insufficient. This explains the low perceived importance of their support in FDHs' handling of workplace hardships. However, as the interview findings revealed, in circumstances of child and elderly care, support deficiency might be because the employers fail to offer FDHs enough aid after burden transfer. Promotion programs aimed at enhancing FDHs' labor rights and skills for caring for frail persons may include both migrant workers and employers as target groups to encourage a safe and supportive work environment that mutually benefits the family and the workers.

Third, this study presents how the employment structure can conduce to workplace hazards and limit migrant workers' selection of external and internal resources to maintain their health. Immigration and labor policies are complex and multifaceted. However, insomuch as the government continues to incorporate FDHs into Hong Kong's workforce, there is a need to provide corresponding protective mechanisms at the structural level. Improving communication channels to ease the reporting and follow-up of abuse and exploitation cases is one approach. Broader discussions at the policy level must consider the impacts of the employment design on power dynamics in home settings and FDHs' access to aids as this study revealed.

Limitations

This study has three limitations. First, many participants only speak basic English or Cantonese, which may have prevented them from being able to fully articulate their experiences with abuse, exploitation, coping, and support. Knowing that language could be an issue, extra efforts were made to translate the survey questions into Tagalog and Bahasa Indonesia. Still, the language barrier may affect interview participants' sharing of their life stories. Our own experiences with the language barrier offer additional explanations regarding why migrant workers may encounter conflicts in the workplace, as similar communication issues may occur between them and their employers and the persons they care for. Second, this study was designed to use 3 months for data collection. However, we overlooked the fact that our potential participants were only available on Sundays. The misjudgment reduced the amount of time available for data collection and subsequently limited the sample size of our survey study. Practical issues like this should be considered in future research. Third, the interview data captured physical and verbal abuse but not sexual abuse, which was reported in the anonymous survey but absent in the interviews. It was unclear whether our interview participants did not have any relevant experiences to convey, or whether they were hesitant to share their stories with us. Building partnerships with migrant worker rights organizations and reaching FDHs through them might be a more ethical and sustainable way to explore this problem in the future.

Conclusion

Hiring FDHs has become a trend in Hong Kong and around the world in the wave of late capitalism. However, research has shown relatively less concern for issues related to coping and social support from the FDHs' perspective. This inspired us to examine FDHs' ways of dealing with abuse and exploitation within a power-imbalanced employment structure. In this study, whenever we addressed participants' current place as “your employer's house,” they would simply respond to our questions by referring to what was supposed to be their “workplace” as their “home.” The word choice reflects their perceptions of the space as their home instead of a place wherein they offer their labor. However, this has not been a common understanding among the employers and their family members, resulting in conflicts and difficulties that many FDHs experience in Hong Kong. This study may set a foundation for future research on FDHs and their interactions with various stakeholders. The findings may also be useful in bringing more insights into further development of support programs available and accessible to these workers.

Data availability statement

Due to privacy and ethical concerns, the data cannot be made publicly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to leannechang@hkbu.edu.hk.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong Baptist University (REC/19-20/0146). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CC and PM conducted the survey, interviews, and drafted the manuscript. LC revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amnesty International (2014). Submission to the legislative council's panel on manpower— policies relating to foreign domestic helpers and regulation of employment agencies. Available online at: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr13-14/english/panels/mp/papers/mp0227cb2-870-3-e.pdf (accessed January 1, 2022).

Baig, R. B., and Chang, C. W. (2020). Formal and informal social support systems for migrant domestic workers. Am. Behav. Sci. 64, 784–801. doi: 10.1177/0002764220910251

Basnyat, I., and Chang, L. (2021). Tensions in support for family caregivers of people with dementia in Singapore: a qualitative study. Dementia. 20, 2278–2293. doi: 10.1177/1471301221990567

Bernadas, J. M. A. C. (2015). Exploring the meanings and experiences of health among Filipino female household service workers in Hong Kong. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. 11, 95–107. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-05-2014-0019

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 9, 3–26. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196

CDC (2008). Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/CM_Surveillance-a.pdf (accessed January 1, 2022).

Census Statistics Department (2017). 2016 population by-census technical report. Available online at: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1120099/att/B11200992016XXXXB0100.pdf (accessed October 9, 2022).

Census Statistics Department (2021a). Thematic household survey: Report No. 72. Available online at: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/C0000016/att/B11302722021XXXXB0100.pdf (accessed January 1, 2022).

Census Statistics Department (2021b). Table E034: Median monthly domestic household income of economically active households by household size. Available online at: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/EIndexbySubject.html?scode=500andpcode=D5250038 (accessed January 1, 2022).

Cheng, S. J. A. (2003). Rethinking the globalization of domestic service: Foreign domestics, state control, and the politics of identity in Taiwan. Gend. Soc. 17, 166–186. doi: 10.1177/0891243202250717

Cheung, F. (2022). After escaping exploitation, trafficked domestic workers in Hong Kong face another hurdle – legal recognition. Hong Kong Free Press. Available online at: https://hongkongfp.com/2022/09/04/no-longer-scared-silenced-a-hong-kong-domestic-worker-survived-trafficking-to-become-a-community-leader/ (accessed October 9 2022).

Cheung, J. T. K., Tsoi, V. W. Y., Wong, K. H. K., and Chung, R. Y. (2019). Abuse and depression among Filipino foreign domestic helpers. A cross-sectional survey in Hong Kong. Public Health. 166, 121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.020

Chiu, S. W. K., and Asian Migrant Centre (2005). A stranger in the house: Foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong. Available online at: http://www.hkiaps.cuhk.edu.hk/wd/ni/20181024-101559_1_hkiaps_op162_secure.pdf (accessed January 1, 2022).

Chou, K. L. (2012). Perceived discrimination and depression among new migrants to Hong Kong: the moderating role of social support and neighborhood collective efficacy. J Affect Disord. 138, 63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.029

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th Edn. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage.

Deng, J.-B., Wahyuni, H. I., and Yulianto, V. I. (2021), Labor migration from Southeast Asia to Taiwan: issues, public responses future development. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 10, 69–81. doi: 10.1108/AEDS-02-2019-0043

Goldsmith, D. J., and Albrecht, T. L. (2011). “Social support, social networks, and health,” in The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication, ed. T. L. Thompson, R. Parrott, and J. F. Nussbaum (New York, NY: Routledge), 335–348.

Ha, N. H. L., Chong, M. S., Choo, R. W. M., Tam, W. J., and Yap, P. L. K. (2018). Caregiving burden in foreign domestic workers caring for frail older adults in Singapore. Int. Psychogeriatr. 30, 1139–1147. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218000200

Hennink, M., and Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 292, 114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Ho, K. H., Chiang, V. C., Leung, D., and Ku, B. H. (2018). When foreign domestic helpers care for and about older people in their homes: i am a maid or a friend. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 5, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/2333393617753906

Hsu, H. C., and Tung, H. J. (2010). What makes you good and happy? Effects of internal and external resources to adaptation and psychological well-being for the disabled elderly in Taiwan. Aging Ment. Health. 14, 851–860. doi: 10.1080/13607861003800997

Immigration Department (2003). Standard employment contract and terms of employment for helpers. Available online at: https://www.immd.gov.hk/eng/forms/forms/fdhcontractterms.html (accessed October 9, 2022).

Immigration Department (2021). Statistics on the number of foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong. Available online at: https://data.gov.hk/en-data/dataset/hk-immd-set4-statistics-fdh (accessed January 1, 2022).

Immigration Department (2022). Quick guide for the employment of domestic helpers from abroad. Available online at: https://www.immd.gov.hk/pdforms/ID(E)989.pdf (accessed October 9, 2022).

Immigration Ordinance Cap (2021). Available online at: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap115!en.pdf (accessed 9 October 2022).

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., Jaakkola, M., and Reuter, A. (2006). Perceived discrimination, social support networks, and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 37, 293–311. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286925

Kaur-Gill, S., Pandi, A. R., and Dutta, M. J. (2021). Singapore's national discourse on foreign domestic workers: exploring perceptions of the margins. Journalism 22, 2991–3012. doi: 10.1177/1464884919879850

Kuo, W. H., and Tsai, Y. M. (1986). Social networking, hardiness and immigrant's mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 27, 133–149. doi: 10.2307/2136312

Labour Department (2022). Practical guide for employment of foreign domestic helpers: What foreign domestic helpers and their employers should know. Available online at: https://www.fdh.labour.gov.hk/res/pdf/FDHguideEnglish.pdf (accessed October 9, 2022).

Ladegaard, H. J. (2013). Demonising the cultural other: legitimising dehumanisation of foreign domestic helpers in the Hong Kong press. Dis. Cont. Media. 2, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2013.06.002

Lai, Y., and Fong, E. (2020). Work-related aggression in home-based working environment: experiences of migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. Am. Behav. Sci. 64, 722–739. doi: 10.1177/0002764220910227

Lan, P. C. (2003). Negotiating social boundaries and private zones: the micropolitics of employing migrant domestic workers. Soc. Probl. 50, 525–549. doi: 10.1525/sp.2003.50.4.525

Legislative Council Secretariat (2017). Foreign domestic helpers and evolving care duties in Hong Kong. Available at https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1617rb04-foreign-domestic-helpers-and-evolving-care-duties-in-hong-kong-20170720-e.pdf (accessed October 9, 2022).

Liao, T. F., and Gan, R. Y. (2020). Filipino and Indonesian migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong: their life courses in migration. Am Behav Sci. 64, 740–764. doi: 10.1177/0002764220910229

Lin, T. T. C., and Sun, S. H. L. (2010). Connection as a form of resisting control: mobile phone usage of foreign domestic workers in Singapore. Media Asia. 37, 183–192.

Malhotra, R., Arambepola, C., Tarun, S., de Silva, V., Kishore, J., and Østbye, T. (2013). Health issues of female foreign domestic workers: A systematic review of the scientific and gray literature. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 19, 261–277. doi: 10.1179/2049396713Y.0000000041

McKay, D. (2007). ‘Sending dollars shows feeling'–emotions and economies in Filipino migration. Mobilities 2, 175–194. doi: 10.1080/17450100701381532

Mission for Migrant Workers (2022). Service report 2021. Available online at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1muIIgkYnzHSuVl58c-d-EQ4EIoAbGbfQ/view (accessed October 9, 2022).

Noh, S., and Kaspar, V. (2003). Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am. J. Pub. Health. 93, 232–238. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.232

Okechukwu, C. A., Souza, K., Davis, K. D., and De Castro, A. B. (2014). Discrimination, harassment, abuse, and bullying in the workplace: contribution of workplace injustice to occupational health disparities. Am. J. Ind. Med. 57, 573–586. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22221

Oktavianus, J., and Lin, W. Y. (2021). Soliciting social support from migrant domestic workers' connections to storytelling networks during a public health crisis. Health Commun. 8, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2021.1996675

Orbe, M. P. (1998). From the standpoint (s) of traditionally muted groups: explicating a co-cultural communication theoretical model. Commun. Theor. 8, 1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.1998.tb00209.x

Østbye, T., Malhotra, R., Malhotra, C., Arambepola, C., and Chan, A. (2013). Does support from foreign domestic workers decrease the negative impact of informal caregiving? Results from Singapore survey on informal caregiving. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 68, 609–621. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt042

Parreñas, R. S., Kantachote, K., and Silvey, R. (2021). Soft violence: migrant domestic worker precarity and the management of unfree labour in Singapore. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 47, 4671–4687. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732614

Piocos, I. I. I. C. M, Vilog, R. B. T., and Bernadas, J. M. A. C. (2022). Interpersonal ties and health care: Examining the social networks of Filipino migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 30, 86–102. doi: 10.25133/JPSSv302022.006

Qayum, S., and Ray, R. (2003). Grappling with modernity: india's respectable classes and the culture of domestic servitude. Ethnography 4, 520–555. doi: 10.1177/146613810344002

Reinhardt, J. P., Boerner, K., and Horowitz, A. (2006). Good to have but not to use: differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 23, 117–129. doi: 10.1177/0265407506060182

Roohafza, H. R., Afshar, H., Keshteli, A. H., Mohammadi, N., Feizi, A., Taslimi, M., et al. (2014). What's the role of perceived social support and coping styles in depression and anxiety? J. Res. Med. Sci. 19, 944–949.

Sherbourne, C. D., and Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 32, 705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

Suri, H. (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 11, 63–75. doi: 10.3316/QRJ1102063

Tam, W. J., Koh, G. C. H., Legido-Quigley, H., Ha, N. H. L., and Yap, P. L. K. (2018). “I can't do this alone”: a study on foreign domestic workers providing long-term care for frail seniors at home. Int. Psychogeriatr. 30, 1269–1277. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217002459

Ullah, A. A. (2015). Abuse and violence against foreign domestic workers: a case from Hong Kong. Int. J. Area Stud. 10, 221–238. doi: 10.1515/ijas-2015-0010

Yeoh, B. S., and Huang, S. (2010). Transnational domestic workers and the negotiation of mobility and work practices in Singapore's home-spaces. Mobilities 5, 219–236. doi: 10.1080/17450101003665036

Zwolinski, M., and Wertheimer, A. (2017). Exploitation. Available online at: https://seop.illc.uva.nl/entries/exploitation/ (accessed January 1, 2022).

Keywords: abuse, exploitation, coping, social support, migrant health, women

Citation: Choy CY, Chang L and Man PY (2022) Social support and coping among female foreign domestic helpers experiencing abuse and exploitation in Hong Kong. Front. Commun. 7:1015193. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.1015193

Received: 09 August 2022; Accepted: 04 November 2022;

Published: 23 November 2022.

Edited by:

Rebecca T. de Souza, San Diego State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Xiaoman Zhao, Renmin University of China, ChinaSatveer Kaur-Gill, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, United States

Copyright © 2022 Choy, Chang and Man. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leanne Chang, leannechang@hkbu.edu.hk

Chin Yung Choy

Chin Yung Choy  Leanne Chang

Leanne Chang