“Abbiamo detto con te no che tu hai ta da di da dim (Moves Right Hand on the Beat)”—The Interplay of Semiotic Modes in Chamber Music Lessons Under a Multimodal and Interactional Perspective

- Institute for Romance Studies, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

This study analyzes the interplay of semiotic modes employed by a teacher and music students in a chamber music lesson for instructing, learning, and discussing. In particular, it describes how specific higher-level actions are accomplished through the mutual contextualization of talk and further audible and visible semiotic resources, such as gesture, gaze, material objects, vocalizing, and music. The focus lies on modal complexity, i.e., how different modes cohere to build action, and on modal intensity, i.e., the importance of specific modes related to their useful modal reaches. This study also attends to the linking and coherent coordination of interactional turns by the participants to achieve a mutual understanding of musical ideas and concepts. The rich multimodal texture of instructional, negotiation, and discussion actions in chamber music lessons stresses the role of multimodality and multimodal coherence in investigating music and pedagogy from an interactional perspective.

Introduction

This study focuses on the question of how different modes are used to communicate and interact in a multimodal way between professor/teacher and musicians/students in chamber music lessons at a conservatory in Italy. The short extract in the title of this study shows how the professor for chamber music connects speech (“abbiamo detto con te no che tu hai”—we said with you know that you have), vocal imitations (“ta da di da dim”), and gesture (“moves right hand on the beat”) to talk about music with the students. These are only three among other semiotic modes that come into play in chamber music lessons for different practices such as locating, addressing, evaluating, correcting, and instructing. The modes “cohere”—in Bateman's (2014a) terms—in a multimodal ensemble, i.e., they “naturally” belong together and are involved in the process of multimodal meaning-making.

To explore multimodal practices in chamber music lessons, this study adopts a mixed-methods approach by combining multimodal (inter)action analysis (Norris, 2004, 2011, 2016, 2019) and multimodal conversation analysis (Deppermann, 2013, 2018; Mondada, 2014, 2016, 2019a). I will work with a corpus consisting of video data from chamber music lessons at the music conservatoire Claudio Monteverdi Bolzano. This study aims to fill a gap in the multimodal study of institutional/didactic/musical communication.

The following research questions will be addressed in this study:

• How do the different modes in chamber music lessons cooperate to build a multimodal structure or a ‘multimodal gestalt' (cf. Mondada, 2014)? How are they orchestrated in the emergent and incremental character of the social interaction between professors and musicians?

• How many modes are involved in any higher-level action (modal complexity)? How strongly are individual modes engaged during an interactional sequence (modal intensity, cf. Pirini, 2014, p. 83)?

• How is multimodal coherence reached within and between modes?

In this study, first, I briefly review some of the previous studies on pedagogic/didactic musical settings and findings on multimodal characteristics. Second, I will describe the institutional and didactic context of chamber music lessons and the associated discursive rights and obligations. In a third step, after laying the methodological foundations for concrete analysis, I will examine the role of different modes adopted in interactional sequences by professors and musicians with the help of two examples taken from our corpus. In this section, I will try to answer the research questions and identify the functions of the (typical) modes employed by the parties involved in chamber music lessons. In the final step, I will discuss the results and provide an outlook for further studies.

Multimodal Interaction

This study enters the analysis of complex and dynamic types of multimodality as it deals with a setting which is still underexplored in terms of the interaction and combination of multiple modes: chamber music lessons. Multimodal interaction in chamber music lessons can be analyzed as taking place within a “site of engagement” (Norris, 2004, p. 44–46, 2016, p. 123). A ‘site of engagement' can be interpreted as “the real-time window opened through the intersection of social practice(s) and mediational means that makes that lower (or higher level) action the focal point of attention of the relevant participants” (Norris, 2004, p. 45). It includes social actors, the physical environment, and the acting with and through it in time (Norris, 2016, p. 123). In this sense, any social action between the social actors in the physical environment of a chamber music lesson is mediated by semiotic modes, i.e., “a set of resources, shaped over time by socially and culturally organized communities, for making meaning” (Jewitt et al., 2016, p. 15) (e.g., speech, gesture, gaze, facial expression, music, and handling of objects).

For example, when, in chamber music lessons, the professor instructs how to play a certain passage in the score, he or she performs a higher-level action that is constructed through a multitude of chained lower-level actions (e.g., uttering, gesturing, directing the gaze, singing/vocalizing a passage, and so on). Any higher-level action is demarcated by a socially constituted and identifiable beginning and closing point (cf. Norris, 2004, p. 11). The higher-level action of correcting in a chamber music lesson, for example, starts with the vocalization of a “problematic” passage in the score and ends with a verbal explanation. The lower-level actions that constitute a higher-level action—or, in terms of Norris (2016, p. 125) “the smallest pragmatic meaning unit of a mode” —then, are mediated by the mediational means of spoken language, gesture, gaze, vocal imitations, etc. Lower-level and higher-level actions are interdependent in interaction: “they are produced by, and produce, the other” (Pirini, 2017, p. 112). The interaction between teacher and students in chamber music lessons can also be mediated by the mediational means of objects, such as the score (as a “frozen action,” cf. Pirini, 2014, p. 80), which is “‘translated' […] into musical sound and becomes the object of interpretation and interaction” (Stöckl and Messner, 2021).

To describe how different modes are interlinked and to explain what happens when various modes combine in interactional sequences in chamber music lessons to build higher-level and lower-level actions, I will include the concepts of “modal intensity,” “modal complexity,” and “multimodal coherence.” “Modal intensity” was introduced by Norris (2004, p. 90) for “the intensity or weight a mode carries in the construction of a higher-level action.” For example, in the higher-level action of locating a passage in the score by the professor, the weight of speech as a mode can be higher than that of gesture as a mode. Higher-level actions may also be of different “modal complexity,”a concept that refers “to the interrelationship of modes in a particular social action” (Pirini, 2014, p. 83). Modal complexity can be understood as “lower-level action complexity,” i.e., the complexity of lower-level actions producing/produced by a higher-level action. In chamber music lessons, the higher-level action of correcting has a higher modal complexity than the higher-level action of evaluating, as the former may include modes such as speech, gesture, gaze, vocalizations, and body posture, and the latter being composed predominantly by spoken utterances.

Last but not least, in this study, I will focus on the linking and interaction of semiotic modes, i.e., on “intermodal harmony” (Norris and Maier, 2014, p. 390), “intermodal relations” (Caple, 2008), “modal density” (Norris, 2009, p. 84–88), or “multimodal coherence” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 151–164). I will illustrate “how diverse combinations of semiotic modes can work together to form coherent communicative artifacts” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 171) and “how […] disparate message components with potentially very different properties combine to produce “more” than what can be achieved in isolation” (Bateman, 2016, p. 37). In this study, I understand “multimodal coherence” as the interplay between different semiotic modes. I will look at how modes interact with other modes and how they contribute to others in the multimodal ensemble (cf. Jewitt, 2009, p. 25). The meaning realized by different modes may be “aligned” or not, i.e., modes can also be complementary; modes can be contradictory when used to refer to distinct aspects of meaning, or in tension (cf. Jewitt, 2009, p. 25). I will use these ideas about alignment and complementarity along with modal density (made up of intensity and complexity of modes) to explore multimodal coherence. In doing so, it is important to focus on the holistic and gestalt-like properties of any multimodal coordination or action, postulated in the analytical framework of conversation analysis (Deppermann, 2013, p. 2). Thus, multimodal resources are linked to the participant's perspective and not to “a priori assumptions about distinct modalities to be assembled” (Deppermann, 2013, p. 2). The second understanding of coherence is linked to the interactively generated communication and understanding of music.

Multimodality in Music Pedagogy

To date, research in a pedagogic/didactic music context has been limited, and the chamber music lesson context has not yet become the subject of academic interest. The research that has been conducted so far has looked at, for example, instrument lessons and music master classes. Studies on such musical settings focus frequently on giving direction and/or evaluation of learner performance by the instructor/master through linguistic and embodied practices. Stevanovic (2020, 2021), for example, focused on specific directive forms in combination with gestures (e.g., the teacher explains and shows the movement of the bow) in violin lessons to mobilize student compliance. The author analyzed music instrument teachers' use of noun metaphors and metonymies related to body positions associated with playing and handling a musical instrument. Along similar lines, Stevanovic and Kuusisto (2019) considered teachers' talk, bodily conduct, and the material environment (including the musical instruments and note stands) in instrument lessons to elicit desired changes in their student's knowledge and skill. Also, Ivaldi's (2016) study of the interplay of talk, vocalizations, and visual demonstrations in one-to-one lessons at a music conservatoire and Nishizaka's (2006) description of how talk, gestures, and the physical handling of objects (e.g., bow) work to (re)structure the environment and to establish learning targets in violin lessons that contribute to this line of research. Tolins (2013) also looked at the role of non-lexical vocalizations combined with gestures, prosody, and bodily movements in music lessons when providing assessments of a student's play. All these studies highlight the complex interplay of different modes, such as talk, vocalizations, gestures, and embodied movements, material artifacts, and physical space of the lesson: “participants in interaction use spoken utterances, embodied behavior, and material artifacts in concert with each other in order to coordinate their joint activities and to reach a mutual understanding of what they are up to at each moment of interaction” (Stevanovic and Kuusisto, 2019, p. 5). The concept of “concert” between different modes by Stevanovic and Kuusisto already made a reference to multimodal coherence. In this study, I aim to describe in a more detailed way how coherence could be reached within and between modes and also between the different actors involved in the setting.

The combination of different semiotic modes in the interaction among instrument/vocal teachers and students is also observable in the growing corpus of studies concerned with instructional activities in vocal and instrumental master classes (cf. also studies on music instruction in orchestra rehearsals, e.g., Weeks, 1996; Veronesi, 2014; Messner, 2020; Stöckl and Messner, 2021). Reed and Szczepek Reed (2013, 2014), and also Szczepek Reed et al. (2013) considered the sequentiality and emergence of different turns in master classes, i.e., talk-based instructions by the master followed by non-talk-based performing actions by the student-performers. In other words, teachers' instructions involve verbal, embodied, sung, and other enacted practices, while students respond to these instructions by playing or singing rather than talking. In my findings, student performers do not always react with ‘musical answers' to the instructional turns by the teacher, but they rather use the same/comparable modalities as the teacher applies (vocalizing, gesturing, miming, etc.). We will see that this can also lead to negotiation processes between instructor and performer and have an impact on the collective understanding of music.

Hsu et al. (2021) analyzed parallel syntactic structures in speaking and depicting in cello master classes, whereas Szczepek Reed (2021) focused on the role of the body in singing instruction in music master classes. Haviland (2007, 2011) also showed how professional musicians alternate verbal comments and suggestions with physical expressions (i.e., embodied demonstrations such as playing the instrument, miming, singing, gesturing, and manipulating the score, the students' bodies, and their instruments) to give music students feedback on their musical performance. The study of Sambre and Feyaerts (2017) also fits in this study as they examined the multimodal construction of musical meaning in a trumpet master class through the combination of speech, metaphorical hand gestures, and material objects (e.g., instrument and musical score). The authors describe musical interactions as “multimodal and embodied phenomena” (Sambre and Feyaerts, 2017, p. 10) and emphasize the role of bodily performance in musical master classes. Also, this study enters the analysis of multimodal phenomena and clusters in musical interaction processes such as chamber music lessons and investigates the complexity of the modes that are employed for any higher-level action (e.g., instructing, explaining, demonstrating, and evaluating) and the intensity of these modes (i.e., the relative importance of a semiotic mode).

My study contributes to the described body of research in institutional, didactic, and musical interaction by exploring multimodal coherence between modes used by the participants in a chamber music lesson at a music conservatoire. The investigation aims to offer useful insights on “the situated nature of collective music-making” (Veronesi, 2014, p. 469) as well as on didactics and pedagogy.

The Institutional Context of Chamber Music Lessons

In chamber music lessons, a teacher and a group of music students work together on a musical piece in order to perform it later in front of an audience (without the teacher). Joint practical action is, therefore, constitutive for this specific institutional and didactic setting, where the teacher corrects, instructs, makes suggestions for musical interpretation, and structures the ongoing interaction (“doing being teacher”), and the musicians transpose the directives on their instruments and also correct their performance themselves musically and verbally (“doing being student”). The focus is, in this study, such as in comparable musical settings, e.g., instrument lessons and musical master classes, on correcting and instructing learner performance.

The resulting constant alternation between verbal conception (by the professor/teacher) and physical implementation (by the musicians/students) makes chamber music lessons a multimodal setting par excellence. Music lessons prove to be specifically tailored to transforming ideas and concepts that are initially captured linguistically into (primarily) non-linguistic forms of expression (musical performance). Physical resources, however, do not only play a role in the second responsive position but they can also be part of the instructing activities themselves (cf. the concepts “instruction” vs. “instructed action,” Garfinkel, 2002, chap. 6), for example, when the teacher shows the students by performing illustrative gestures and vocal imitations of sonic qualities how they should interpret a certain musical passage on their instruments.

In doing so, different modes are linked coherently to create a joint action, i.e., imitational singing/vocalizing, gesture, gaze, body posture/movement, and talk are tied together by the professor to correct/instruct the musicians. Besides, students can also make use of several modes when reacting (linguistically) to the instructions and corrections by the teacher, e.g., they can implement musical patterns or deictic gestures on their instruments in a verbal sequence. This interplay of various modes, predominantly intertwined in a coherent way with each other, leads to multimodal meaning-making in chamber music lessons. The general aim of this study was to elucidate the interrelations between the different multiple semiotic modes needed to investigate coherence-building.

Data Collection and Methodology

The extracts presented below are part of a corpus of data collected in a chamber music lesson in April 2018 at the conservatoire Claudio Monteverdi Bolzano (~2 h of data). The author was present at these recordings as the clarinetist in the student's trio (piano, cello, and clarinet). The ensemble, together with a professor for chamber music, was rehearsing and elaborating the trio for piano, clarinet, and violoncello in a-minor, opus 114 from Johannes Brahms.

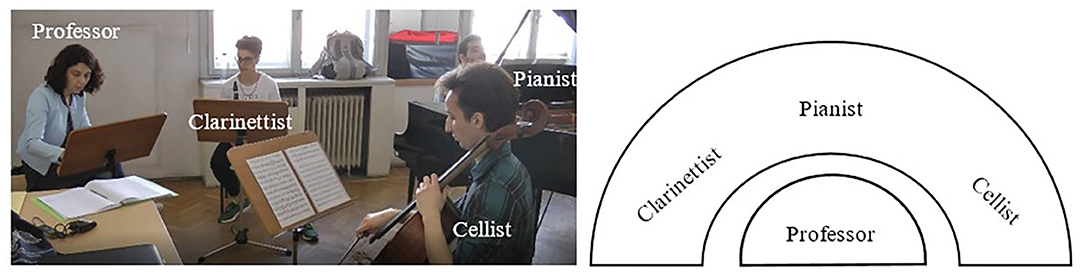

During the chamber music lessons, the students sit in a semicircle facing the professor and simultaneously facing each other; the professor sits (or stands) in front of them. This specific arrangement of the participants is part of the participation framework and constitutive for the joint work (cf. Figure 1).

The resulting recordings have been transcribed following GAT II conventions (Selting et al., 2009) for verbal parts of the interaction and Mondada's conventions (Mondada, 2018, 2019a) for embodied aspects of the conversation. The data were analyzed with multimodal conversation analysis and multimodal (inter)action analysis. Conversation analysis adopts a microanalytic approach to procedures used by social actors to produce interactional conduct and meaning. It describes how talk and other bodily behaviors in interaction are organized sequentially, i.e., it argues that the meaning of an action is linked to the interpretation of the prior action(s) (Heritage, 1984; Schegloff, 2007; Sidnell, 2010; Clift, 2016). In institutional interaction, conversation analysis has been used to explain how talk and other semiotic modes are employed to orientate toward specific institutional goals as well as to handle special constraints (e.g., in turn-taking and turn design) and specific inferential frameworks. Conversation analysis describes how social institutions, such as chamber music lesson interaction examined in this study, are “talked into being” (Heritage, 1984, p. 290).

Multimodal (inter)action analysis takes the action as a unit of analysis and looks at three action types and their inter-connections (lower-level, higher-level, and frozen actions) within a “site of engagement”, i.e., a real-time window onto social practices and actions (cf. Norris, 2004, 2016). Chamber music lessons become a site of engagement because different practices (e.g., rehearsing a piece of music, discussing music, correcting musical performance, and repeating music) are performed at a particular time in a particular place by different social actors (e.g., teacher and students). Another aim of multimodal (inter)action analysis is to explore how various modes (e.g., talk, gesture, and object handling) play together in interaction (modal complexity) and how these modes fluctuate in hierarchies (modal intensity).

Results

Extract 1: “Abbiamo detto con te no che tu hai ta da di da dim”

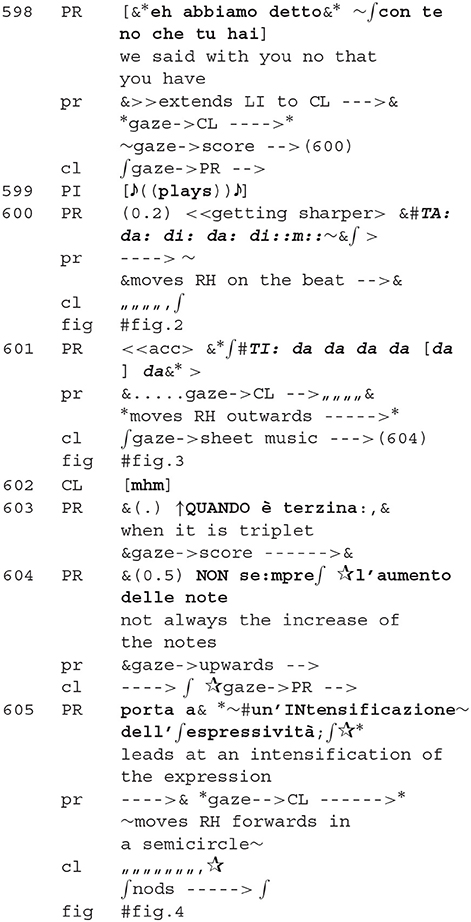

Extract 1 represents an interaction episode between the professor (PR) and the clarinetist (CL). Prior to this sequence, the professor discussed with the pianist (PI) how to play a passage in the score. When the professor switches to the dialogue with the clarinet, the pianist plays some notes on his instrument (L599, and it can be assumed that he is trying out what has been talked about before). In the snippet, several different modes come about through concrete lower-level (e.g., index finger extended in a specific direction, L598) and higher-level actions (e.g., demonstrating vocally a passage in the score, L600-601).

The sequence starts with multimodal addressing of the clarinetist (L598). As can be noted, the professor not only verbally addresses the clarinetist (“con te”—with you, “tu”—you) but also demonstrates it visually, in which she extends the left index and turns the gaze toward the clarinetist. The clarinetist replies to the addressing with a gaze in the direction of the teacher. Simultaneously to this addressing sequence, which also projects a subsequent explanation of the music, the pianist plays on his instrument (L599).

In these two lines, different semiotic modes interconnect in “cohesive chains” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 153): speech, gesture, and gaze are used by the professor for the higher-level action of addressing the clarinetist. By reacting through a gaze cue, the clarinetist shows the understanding that she is now the addressed one and that what follows concerns her. It is also interesting that the playing by the pianist does not disturb the verbal and visual turn of the teacher. This means that in this section, the turn of the professor stands over the musical turn of the piano student and that various modes with different properties (talk: acoustically, gesture and gaze: visually, and music: acoustically) can occur simultaneously, even if employed for contrasting higher-level actions (addressing a student vs. applying previous corrections/instructions on the instrument).

An even more complex interplay (or “lamination,” cf. Goodwin, 2013, p. 12; Veronesi, 2014, p. 479) between semiotic modes can be observed in the way the professor identifies and demonstrates a passage in the score (L600-601). The verbal addressing in L598 also frames and incorporates an embodied demonstration which follows in L600-601. The teacher uses onomatopoetic syllables (“ta,” “da,” “di” and “dim”) to demonstrate the musical passage vocally and also uses prosody to highlight certain musical aspects (cf. getting sharper in L600, accelerando/getting faster in L601, stressing the syllable “TA,” and stretching the sequences of sound). Simultaneously, she moves her right hand on the beat (L600, cf. Figure 2) and outward (L601, cf. Figure 3) and directs her gaze to the score and to the clarinetist. In this study, a “multimodal gestalt” (Haviland, 2007, p. 153; Mondada, 2014) emerges, “in which talk and embodied action have their own specific affordances and contribute, in different ways, to its construction” (Veronesi, 2014, p. 480). By vocalizing the passage from the score and also respecting melodic progression, rhythm, and accentuation, the professor not only locates a trouble source or correctable but she also identifies and demonstrates the trouble source/correctable; the moves in the right hand underline the sung demonstration. By gazing at the clarinetist, the teacher indicates once again that she and her playing are concerned. Thus, in this section, two higher-level actions become visible: locating a correctable and demonstrating the correctable. Nevertheless, locating is the priority activity: the mode of vocalizing is more in the service of locating the trouble source because the teacher implements an accelerando in her singing which is not written in the score and which takes her faster to the verbal explanation of the correctable (cf. L603-605).

In this locating/demonstrating section also, various cohesive chains bind the higher-level actions together: vocalizing, prosody, and gesture link the demonstration with a certain passage in the score, and gaze cues link it with an instructed person (the clarinetist) and also with the score. As a consequence, the combination of different modes “accumulates meanings that are not expressed in either of the modes individually” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 153). For instance, the singing without prosody could not be used to identify a trouble source, and the score without gazing at it could not be a common reference point for the teacher and the clarinetist (cf. the look of the clarinetist into her sheet music in L601, Figure 3). Furthermore, the vocal and visual demonstration of the professor leads to verbal ratification of the clarinetist (“mhm” in L602), which shows a mutual understanding of music.

In L603-605, the teacher then goes on with a verbal explanation of the vocally located passage in the score. In L603, she locates the correctable even verbally by referring to a specific rhythm (“quando è terzina”) and thus delimits the passage to be discussed more precisely. In L605, while continuing her turn-at-talk (“porta a un'intensificazione dell'espressività”), the teacher uses a gesture in the right hand (move forward in a semicircle, cf. Figure 4) to underline her explanation. This sort of “highlighting” (cf. Goodwin, 1994) is also observable in stressing the syllable “IN” in “intensification” (cf. also “QUANDO” and “NON”). The verbal explanation—in combination with the gesture and also a gaze in the direction of the clarinetist—presents the previous performance of the passage by the clarinetist as correctable and simultaneously instructs how not to play. Interestingly enough, even if the instruction by the professor remains indexical, the clarinet student ratifies it and shows understanding by nodding in L605.

Extract 2: “You Didn't Follow Him”

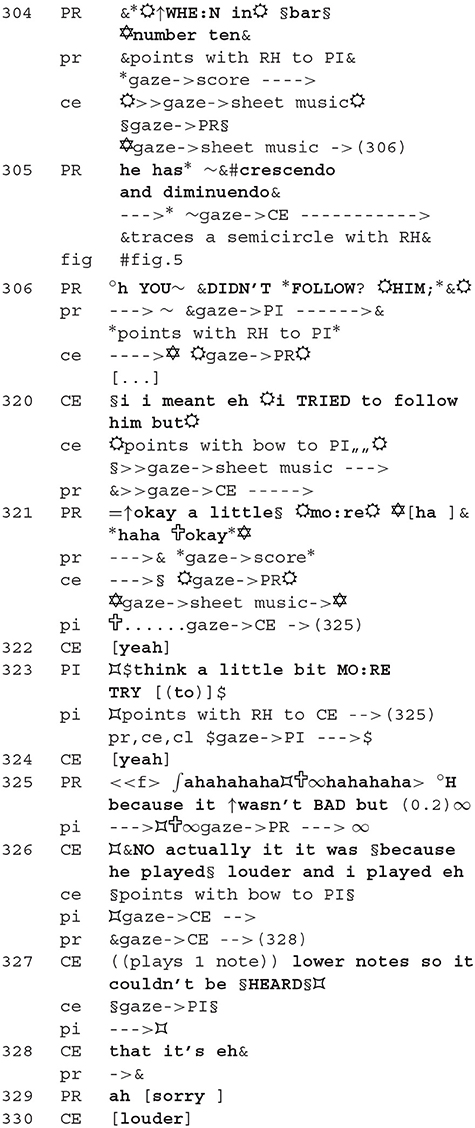

The following extract shows an interaction sequence between the professor (PR) and the violoncellist (CE). The professor, first, locates the trouble source in the score (L304-305) and then identifies the problem (L306). From L320 until the end of the extract, the teacher and the cellist negotiate the prior performance and the problem of not following the pianist. In L321 and 325, the teacher instructs the cellist to adapt even more to the musical line of the piano. The pianist (PI) also enters the dialogue by directing a slightly modified form of the teacher's instruction to the cellist (L323). In L326–330, the cellist explains why he was not able to follow the pianist as required. As in example 1, also in this snippet, several lower-level actions (e.g., uttering corrective instructions, L321, L323) and higher-level actions (e.g., locating, instructing, reasoning) set up the interaction and simultaneously constitute each other in interaction.

Lines 304–306 contain an initial sequence in which a correctable is established by the teacher. This instructional sequence is introduced by two verbal locations of the correctable in the score. In L304, the professor indicates the respective bar number in the score (“bar number ten”), and in L305, she refers to a dynamic line, which the pianist has to play at that specific place (“he has crescendo and diminuendo”). This locating practice is followed by a verbal correction addressed to the cellist (“you didn't follow him”). The observable higher-level actions of locating and correcting are both made up of chained lower-level actions. Locating is made up of verbal utterances, hand pointing, tracing a semicircle, and gaze shifts (cf. Figure 5). Correcting comprises a verbal utterance, hand pointing, and gaze shifts. Various modes thus band together in cohesive chains: speech, gesture, and gaze. It can be observed that gestures, proxemics, and gaze are actively used by the mode of speech to extend the “range” (cf. Wildfeuer et al., 2020, p. 149).

It is possible to identify a further higher-level action, which is realized within the higher-level action of locating. In L304–305, as the teacher locates a passage in the score through talk and gaze (she looks at the score), she uses gaze to address the cellist and employs gestures (pointing) to involve the pianist indirectly in the interaction. As a matter of fact, she accomplishes two higher-level actions at the same time: locating and addressing. This timed coordination of various simultaneous activities constitutes a specific form of “multiactivity” (Mondada, 2012; Haddington et al., 2014). Interestingly enough, the cello student does not immediately reply to the addressing practice of the professor but looks at his sheet music until the end of L306. Only then, he shifts his gaze to the professor and thereby displays his understanding of the professor's prior turn as an addressing practice directed to him.

Then, in L320, the cellist explains verbally his feeling about the prior performance (“I tried to follow him”) and points with his bow in the direction of the pianist. This is followed by a verbal instruction from the professor in L321 (“a little more”) and another instruction from the pianist in L323 (“think a little bit more try (to)”). In this study, the pianist takes up the role of the instructor: he repeats the instruction of the teacher and uses a pointing gesture to direct the turn to the cellist. In doing so, he takes on “primary agency” (Pirini, 2017, p. 111, 127) for the higher-level action of instructing, i.e., agency for this specific action shifts from professor to student. The cellist ratifies both instructions verbally (“yeah”). In L325, the professor starts to laugh and gives a verbal account related to her prior instruction (“because it wasn't bad but”). The sequence can be interpreted as an attempt to ease the situation: the pianist takes the laughter of the teacher—which already starts in L321—as an opportunity to instruct the cellist and parodies in this way the professor. In L326, the cellist continues the syntactically incomplete turn of the professor (cf. the adversative conjunction “but” at the end of L325) through a further justification/account and points again with his bow in the direction of the pianist. He embeds a note on his instrument in his turn (cf. L327) and is thereby anticipating what he will talk about shortly later: the lower notes that “could not be heard.” The sequence is closed by a verbal apology from the professor (“sorry”) that ratifies in the same breath the explanation of the cellist.

In this section, various higher-level actions can be observed: justifying/accounting, instructing, and (indirectly) addressing. All these actions are cohesively connected through specific modes: for the higher-level action of justifying/accounting the modes of speech, gesture, gaze, and music play together; the higher-level action of instructing is realized through speech, gaze, and gesture; for addressing, visual (gaze) and gestural (pointing) modes are employed. In the higher-level action of justifying/accounting, in L325-326, the modes of speech and music are interwoven in a specific way: the cellist introduces verbally a following musical demonstration, i.e., he completes the verbal turn in an embodied way (cf. “syntactic-bodily gestalt,” Keevallik, 2015, p. 309). After this short musical performance, he takes up the account and repeats verbally what he played on his instrument (lower notes).

Discussion

Modal Complexity and Modal Intensity

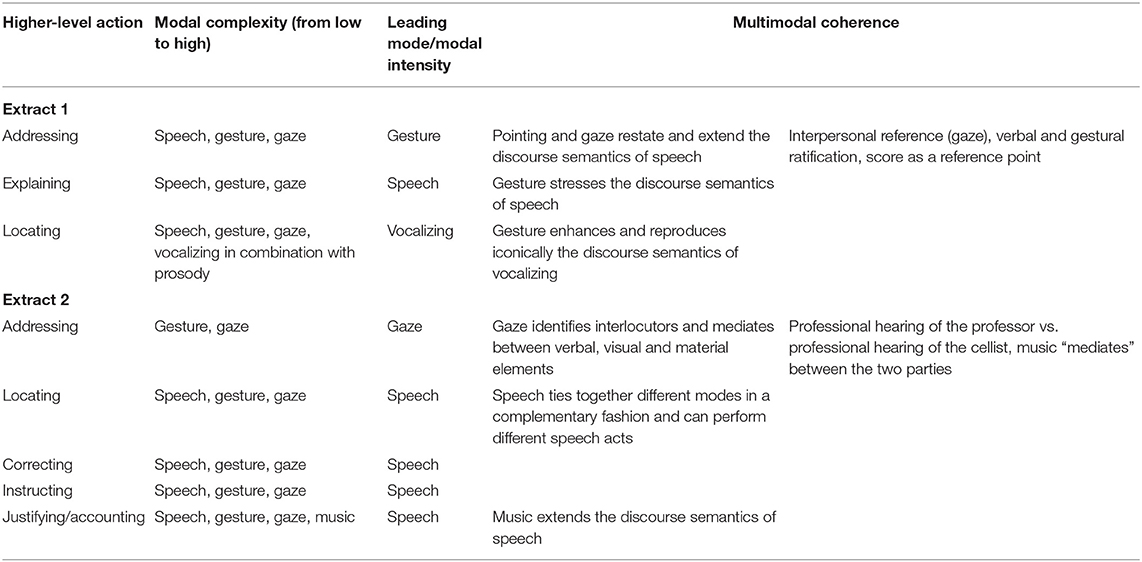

In extract 1, as can be noted, the number of semiotic modes employed, i.e., the modal complexity, and the relative importance of a semiotic mode, i.e., the modal intensity, for any higher-level action are quite different. The higher-level actions of addressing and explaining comprise three different modes (i.e., speech, gesture, and gaze), and the higher-level action of locating includes four modes (i.e., vocalizing with prosody, gesture, gaze, and speech). Speech as an auditive mode allows for personal and material reference (clarinetist, score) and for the expression of musical ideas and concepts. Gesture as a visual mode is used for pointing, highlighting musical concepts, and supporting sung demonstrations. Gaze handles interpersonal rapport and address, and it also shows the involvement of the teacher and the musicians with the score. Vocalizing, and prosody as one of its resources, finally, is an auditive mode that is employed to imitate musical qualities and to identify correctables.

It can be argued that every described mode is involved in the multimodal interaction of a chamber music lesson for a reason: “it fulfils a function owing to and determined by its communicative strengths” (Stöckl and Messner, 2021, p. 12). This “modal reach” (Kress, 2010, p. 83) is connected to modal intensity, i.e., a specific mode is used for certain purposes and has, therefore, a higher modal intensity in particular contexts. In the higher-level actions observable in the transcript different modes are leading or dominant. In the higher-level action of addressing, gesture (or pointing) seems to take on a central role because it enables to disambiguate the verbal address terms employed by the teacher and to address the clarinetist in the most direct way. Vocalizing (in combination with prosody) is the dominant mode in the higher-level action of locating: it is able to identify a passage in the score by imitating musical qualities “without having to ‘translate' meaning from one mode (music) to another” (Stöckl and Messner, 2021, p. 13). Speech, finally, is central for explaining, discussing musical ideas, and instructing musical concepts.

The different higher-level actions are tied together by the omnipresent mode of gaze which is employed—together with talk and gesture—for addressing and focusing attention on the score as a frozen action. The score is the central object in the interaction between teacher and musicians in chamber music lessons: it specifies who has to play what and when. In a meta-communicative way, the participants in a chamber music lesson discuss what is written in the score and what it is played, i.e., they “translate” the score (cf. “transduction,” Kress, 2010, p. 124). By looking at the score, the teacher and the clarinetist signal “the importance of the frozen action and utilize it to glean information about specific parts of the music and its interpretation” (Stöckl and Messner, 2021, p. 14).

In terms of modal complexity, the transcript analysis of the second snippet shows that the combination of speech, gesture, and gaze is fundamental for the interaction between the participants in the chamber music lesson (cf. extract 1). The three modes interconnect in four of the five described higher-level actions: locating, correcting, justifying/accounting, and instructing. The mode of music, i.e., the lower-level action of playing an instrument, adds to only one higher-level action, namely, accounting; the higher-level action of addressing includes gaze and gesture.

In this study, music is added as a further semiotic mode to the modes of speech, gesture, gaze, etc. and fulfills specific functions. It is employed to quote and imitate a part of the prior performance section and simultaneously locate the respective passage in the score. As can be noted, musicians do not only play their instruments in musical performance parts but include tones also in the discussion parts. In extract 1, the pianist delivers a musical turn concurrently with a verbal turn of the teacher; in extract 2, the cellist switches a tone on his instrument into its own verbal turn. However, the music overlapping with another turn in extract 1 is more of a challenging nature, and the music played by the cellist in extract 2 supports the ongoing turn, i.e., it interplays as an embodied demonstration in a coherent way with the verbal description.

In the higher-level actions described for this snippet, a functionally leading modal resource can be identified, namely, speech. This specific mode has a key function due to the fact that “it ties together most modes in a complementary fashion” (Stöckl and Messner, 2021, p. 13): gesture, gaze, vocalizing, and music. Furthermore, speech is able to perform different speech acts, such as locating, correcting, instructing, accounting, justifying, explaining, and describing.

In the higher-level action of addressing, however, the gaze takes on a dominant role. By gazing in the direction of the cellist, the professor identifies him as her interlocutor and as a participant to whom the following corrective turn is addressed. The role of the gaze shifts depending on what kind of higher-level action is being produced, i.e., gaze function is contingent on and “inextricably linked to the material and communicative exigencies” (Geenen and Pirini, 2021, p. 100) of the higher-level action in focus. Gaze is also crucial for incorporating the score as frozen action into the chain of higher-level actions. The participants in the chamber music lesson shift their gaze between persons and the score/sheet music. In doing so, they signal the central role of the score, i.e., the frozen action for the interaction in this specific setting.

Different from what was observed in extract 1, the gesture is not brought into play as a central mode, even though it appears in all higher-level actions. Gesture combines with other modes to include other participants in the ongoing interaction (e.g., the pianist) or to illustrate dynamical aspects of music (e.g., crescendo and diminuendo).

Multimodal Coherence

By looking more precisely at the coherence between the different semiotic modes described above, it could be observed that all the modes in extract 1 are combined in a cohesive and coherent way to realize various communicative actions, such as addressing, explaining, locating, and instructing. Pointing and gaze, for example, restate and extend the meaning of the verbal addressing by the teacher in L598 (cf. “demonstrative reference,” Schubert and Sanchez-Stockhammer, 2022, p. 3). In lines 600–601, vocalizing and gesturing produced simultaneously contribute to identify a specific passage in the score; gesture in this study and especially the gesture in line 601 (teacher moves right hand outward) enhance and reproduce iconically the sung syllables. The gesture of the professor in L605 (moving the right hand forward in a semicircle) is used to highlight the verbal explanation of music. These “intersemiotic” relations (Caple, 2013, p. 122, 175) between the different modes are built on the principles of reformulation, expansion, and emphasis. Reformulation also plays a role in the “intrasemiotic” relations (Caple, 2013, p. 122, 175) that hold between the sequences of higher-level actions. The professor for chamber music not only locates the correctable by imitating vocally what is written in the score/what the clarinetist played before but also by referring verbally to a specific rhythm (“terzina”—triplet). Thus, she connects her singing with her turn-at-talk in a “logogenetic” way (cf. “logogenetic chains,” Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, p. 607) and proceeds to a possible interpretation of the passage and in the same breath to an implicit instruction. This kind of conjunctive relation can also be described with reference to van Leeuwen (2005, p. 219–231) taxonomic distinction between “elaboration” and “extension”: “elaboration” is linked to the repetition of information for the sake of specification or explanation, and “extension” means that new information is connected to previously provided information.

From another perspective, coherence refers to “the cognitive construction of discursive relations by recipients as a comprehension strategy” (Schubert and Sanchez-Stockhammer, 2022, p. 2). In our data, mutual comprehension and meaning are secured by interpersonal reference (primarily through gaze) and by verbal and gestural ratification sequences (cf. “mhm” and nodding by the clarinetist) realized in an emergent and incremental way. The score as a reference point for speaking about music and as pivotal to the interaction between the participants is also central for meaning-making and guaranteeing understanding.

The different semiotic modes employed in extract 2 have different “modal affordances” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 145; Kress, 2010), i.e., different ways of signifying. Bateman (2014a, p. 145) raised the question of how multimodal coherence is possible despite this diversity and stated that coherence arises “in an “interaction” between the material on offer and reader/viewers' incorporation of that material into the unfolding message they are deriving for the communicative artifact they are processing” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 169). The participants in the chamber music lesson use the available “semiotic material” or modes to constitute their turns and interrelate them into various “modal configurations” (cf. Norris, 2009). Speech, gesture, and gaze are always simultaneously at play in given moments of a higher-level action. Speech, then, takes on a hierarchically higher position over the other two modes, i.e., the higher-level action of locating, for example, could not have been realized without the mode of speech. The hierarchical scale of gesture and gaze fluctuates depending on the process of action: gesture is more important than gaze when illustrating musical ideas; gaze takes on a central role when addressing different participants.

Multimodal coherence is also reached through the mutual understanding of music. In the second snippet, the professional hearing of the professor and the professional hearing of the cellist is in opposition to each other. The professor identifies a problem in the performance of the cellist but simultaneously evaluates his performance positively (cf. L325, “because it wasn't bad”) and thereby opens up room for interpretation. The cellist justifies the prior performance, explains his point of view, and shows the problem with his instrument. Interestingly, after the incorporation of a musical tone by the cellist in his justifying process, the professor apologizes (cf. “sorry” in L329) and ratifies the explanation of the cellist. In this study, music is able to “mediate” between two parties and to lead to consensus.

Conclusion

In this study, I have examined how various semiotic modes employed by the participants in a chamber music lesson meaningfully link and cooperate. The central concern of this study was the concept of multimodal coherence. On the one hand, I described multimodal coherence as linking the discourse semantics of individual modes (e.g., speech, gesture, gaze, vocalizing, and music) in order to create a joint one, i.e., a “multimodal gestalt.” On the other hand, I showed how coherence, understood as an interpersonal and intersubjective agreement, is sequentially built up between the participants.

The detailed analysis of two sequences has allowed to shed light on typical higher-level actions and to observe how different modes come into play to realize them. Special focus was laid on the modal complexity of the actions and the changing intensity of the modes at work (cf. Table 1). It was shown that modal complexity is high and that especially the modes of speech, gesture, and gaze contribute to build a “jointly constructed multimodal communicative act” (Bateman, 2014b, p. 165). In the higher-level actions of locating and justifying/accounting, two further auditive modes, namely vocalizing and music, also, take on a central role and seamlessly cooperate with speech, gesture, and gaze. My analysis also highlighted the importance and the contribution of specific modes to an action. It could be observed that speech, gesture, gaze, and vocalizing are leading modes in different higher-level actions. The power of speech lies in its potential to express different speech acts (e.g., referring to persons or objects, expressing ideas, and concepts); gesture supports verbal and vocal turns and serves for interpersonal reference; vocalizing is suited to demonstrating/imitating prior musical performances; gaze, finally, takes on a central role in addressing and in transitioning between verbal turns and visual orientation to the score. Different modes, thus, fulfill divergent functions in this specific context of a chamber music lesson and “provide discourse participants with various possibilities of pursuing their genre-related communicative goals, such as informing, entertaining, instructing or persuading the recipients” (Schubert and Sanchez-Stockhammer, 2022, p. 3).

My analysis supports the research focused on “revealing more of the multimodal discourse processes” (Bateman, 2014a, p. 170) and on its core idea: the coherence between semiotic modes. It offers the first glimpse into the full complexity and interplay of various semiotic modes in the still-underexplored setting of chamber music lessons. Natural next steps in this direction include an extension of the analysis to other interactional sequences in the same and in other chamber music lessons, as well as the examination of other comparable settings (e.g., master classes, instrument lessons, and orchestra rehearsals). This study also hints at the direction for future research on issues such as the consideration of the manifold uses and functions of objects/artifacts (e.g., musical instruments and score/sheet music), the investigation of the interactional dynamics between the professor and the music students, the emergent and incremental sequencing of verbal, vocal, gestural, and musical turns, and also the roles and functions of different languages employed by the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the current study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

My institution, the University of Innsbruck, has funded the present paper. All funds were covered by my institution.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor HS declared a past co-authorship with the author.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I thank the professor for chamber music and the music students for granting me permission to document them for research purposes and to utilize screenshots and the transcript of the video in this study. I am also indebted to the University of Innsbruck who kindly funded this study.

References

Bateman, J. A. (2014a). “Multimodal coherence research and its applications,” in The Pragmatics of Discourse Coherence, eds H. Gruber, and G. Redeker (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 145–177. doi: 10.1075/pbns.254.06bat

Bateman, J. A. (2014b). Text and Image. A Critical Introduction to the Visual/Verbal Divide. London; New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315773971

Bateman, J. A. (2016). “Methodological and theoretical issues for the empirical investigation of multimodality,” in Handbuch Sprache im multimodalen Kontext, eds N.-M. Klug, and H. Stöckl (Berlin: De Gruyter), 36–74. doi: 10.1515/9783110296099-003

Caple, H. (2008). “Intermodal relations in image nuclear news stories,” in Multimodal Semiotics. Functional Analysis in Contexts of Education, ed L. Unsworth (London: Continuum), 125–138.

Caple, H. (2013). Photojournalism: A Social Semiotic Approach. Basingstoke; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137314901

Clift, R. (2016). Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781139022767

Deppermann, A. (2013). Multimodal interaction from a conversation analytic perspective. J. Pragmat. 46, 1–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.014

Deppermann, A. (2018). “Sprache in der multimodalen Interaktion,” in Sprache im Kommunikativen, Interaktiven und Kulturellen Kontext, eds A. Deppermann, and S. Reineke (Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter), 51–85. doi: 10.1515/9783110538601-004

Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology's Program: Working Out Durkheim's Aphorism. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Geenen, J., and Pirini, J. (2021). “Interrelation: gaze and multimodal ensembles,” in Mediation and Multimodal Meaning Making in Digital Environments, eds I. Moschini, and M. G. Sindoni (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 85–102. doi: 10.4324/9781003225423-8

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. Am. Anthropol. 96, 606–633. doi: 10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

Goodwin, C. (2013). The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. J. Pragmat. 46, 8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.003

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., and Nevile, M., (2014). Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking. Amsterdam: Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/z.187

Halliday, M., and Matthiessen, C. (2014). Halliday's Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203783771

Haviland, J. B. (2007). “Master speakers, master gestures: a string quartet master class”, in Gesture and the Dynamic Dimension of Language, eds S. D. Duncan, E. T. Levy, and J. Cassell (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 147–172. doi: 10.1075/gs.1.16hav

Haviland, J. B. (2011). “Musical Spaces”, in Embodied Interaction. Language and Body in the Material World, eds. J. Streeck, C. Goodwin, and C. LeBaron (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). 289–304.

Hsu, H.-C., Brône, G., and Feyaerts, K. (2021). In other gestures: multimodal iteration in cello master classes. Linguistics Vanguard. 7, s4, 20200086. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2020-0086

Ivaldi, A. (2016). Students' and teachers' orientation to learning and performing in music conservatoire lesson interactions. Psychol. Music. 44, 202–218. doi: 10.1177/0305735614562226

Jewitt, C. (2009). “An introduction to multimodality”, in The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, ed C. Jewitt (London, New York: Routledge), 14–27.

Jewitt, C., Bezemer, J., and O'Halloran, K. (2016). Introducing Multimodality. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315638027

Keevallik, L. (2015). “Coordinating the temporalities of talk and dance,” in Temporality in Interaction, eds A. Deppermann, and S. Günthner (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 309–336. doi: 10.1075/slsi.27.10kee

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality. A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Messner, M. (2020). Gesangliche Demonstrationen als instruktive Praktik in der Orchesterprobe. Gesprächsforschung Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 21, 309–345.

Mondada, L. (2012). Talking and driving: multiactivity in the car. Semiotica. 191, 223–256. doi: 10.1515/sem-2012-0062

Mondada, L. (2014). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. J. Pragmat. 65, 137–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: language and the body in social interaction. J. Sociolinguist. 20, 336–366. doi: 10.1111/josl.1_12177

Mondada, L. (2018): Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: challenges for transcribing multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. 51, 85–106. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L. (2019a): Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. J. Pragmat. 145, 47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.016

Mondada, L. (2019b). Conventions for Multimodal Transcription. Available online at: https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription (accessed December 23, 2021).

Nishizaka, A. (2006). What to learn: the embodied structure of the environment. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 39, 119–154. doi: 10.1207/s15327973rlsi3902_1

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing Multimodal Interaction. A Methodological Framework. New York, NY; London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203379493

Norris, S. (2009). “Modal density and modal configurations: multimodal actions,” in The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, ed C. Jewitt (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 78–90.

Norris, S. (2011). Identity in (Inter)action. Introducing Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis. Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9781934078280

Norris, S. (2016). “Multimodal interaction: language and modal configuration,” in Handbuch Sprache im Multimodalen Kontext, eds N.-M. Klug, and H. Stöckl (Berlin: De Gruyter), 121–142. doi: 10.1515/9783110296099-006

Norris, S. (2019). Systematically Working with Multimodal Data: Research Methods in Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781119168355

Norris, S., and Maier, C. D., (2014). Interactions, Images, and Text: A Reader in Multimodality. London; New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.1515/9781614511175

Pirini, J. (2014). “Introduction to Multimodal (Inter)Action Analysis,” in Interactions, Images, and Text: A Reader in Multimodality, eds S. Norris, and C. D. Maier (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 77–91. doi: 10.1515/9781614511175.77

Pirini, J. (2017). Agency and co-production: a multimodal perspective. Multimodal Commun. 6, 109–128. doi: 10.1515/mc-2016-0027

Reed, D., and Szczepek Reed, B. (2013). “Building an instructional project. Actions as components of music masterclasses,” in Units of Talk. Units of Action, eds B. Szczepek Reed, and G. Raymond (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 313–341. doi: 10.1075/slsi.25.10ree

Reed, D., and Szczepek Reed, B. (2014). The emergence of learnables in music masterclasses. Soc. Semiotics 24, 446–467. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2014.929391

Sambre, P., and Feyaerts, K. (2017). Embodied musical meaning-making and multimodal viewpoints in a trumpet master class. J. Pragmat. 122, 10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2017.09.004

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511791208

Schubert, C., and Sanchez-Stockhammer, C. (2022). Introducing cohesion in multimodal discourse. Discourse Context Media. 45, 57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100565

Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J., Bergmann, P., et al. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 10, 353–502.

Sidnell, J. (2010). Conversation Analysis: An Introduction. London: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511635670

Stevanovic, M. (2020). “Mobilizing student compliance. On the directive use of Finnish second-person declaratives and interrogatives during violin instruction,” in Mobilizing Others. Grammar and lexis within larger activities, eds C. Taleghani-Nikazm, E. Betz, and P. Golato (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 115–145. doi: 10.1075/slsi.33.05ste

Stevanovic, M. (2021). Monitoring and evaluating body knowledge: metaphors and metonymies of body position in children's music instrument instruction. Linguistics Vanguard 7, s4, 20200093. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2020-0093

Stevanovic, M., and Kuusisto, A. (2019). Teacher directives in children's musical instrument instruction: activity context, student cooperation, and institutional priority. Scand. J. Educat. Res. 63, 1022–1040. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2018.1476405

Stöckl, H., and Messner, M. (2021). Tam pam pam pam and mi – fa – sol. Constituting musical instruction through multimodal interaction in orchestra rehearsals. Multimodal Commun. 10, 193–209. doi: 10.1515/mc-2021-0003

Szczepek Reed, B. (2021). Singing and the body: body-focused and concept-focused vocal instruction. Linguistics Vanguard 7, s4, 20200071. doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2020-0071

Szczepek Reed, B., Reed, D., and Haddon, E. (2013). NOW or NOT NOW: coordinating restarts in the pursuits of learnables in vocal masterclasses. Research on Lang. Soc. Interact. 46, 22–46. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2013.753714

Tolins, J. (2013). Assessment and direction through nonlexical vocalizations in music instruction. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 46, 47–64. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2013.753721

Veronesi, D. (2014). Correction sequences and semiotic resources in ensemble music workshops: the case of Conduction®. Soc. Semiotics 24, 468–494. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2014.929393

Weeks, P. (1996). A rehearsal of a Beethoven passage: an analysis of correction talk. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 29, 247–290. doi: 10.1207/s15327973rlsi2903_3

Keywords: modal complexity, modal intensity, multimodal coherence, multimodal conversation analysis, multimodal (inter)action analysis, music instruction, music learning

Citation: Messner M (2022) “Abbiamo detto con te no che tu hai ta da di da dim (Moves Right Hand on the Beat)”—The Interplay of Semiotic Modes in Chamber Music Lessons Under a Multimodal and Interactional Perspective. Front. Commun. 7:877184. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.877184

Received: 16 February 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 24 May 2022.

Edited by:

Hartmut Stöckl, University of Salzburg, AustriaReviewed by:

Jesse Pirini, Victoria University of Wellington, New ZealandClarice Gualberto, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

Copyright © 2022 Messner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monika Messner, monika.messner@uibk.ac.at

Monika Messner

Monika Messner