#socialiseresponsibly. Analyzing the Rhetorical Structure of Heineken TV Commercials During the Pandemic

- 1Department of Communication and Information Studies, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

- 2Department of English and Communication, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

This work analyzes the efforts by the company Heineken to address in their marketing campaigns the social responsibility and wellbeing of their customers during the pandemic. By particularly looking at the audio-visual design strategies used in 15 TV commercials produced and published during the years 2020–2022, a multimodal analysis of the filmic montage structures examines how the company establishes a coherent process of core marketing and convinces recipients to socialize responsibly under pandemic conditions. The analysis follows the current trend in empirical multimodality research to pursue analyses of digital corpora with the theories and methods developed in the field. Particularly, it uses an ELAN annotation scheme for the description of specific camera techniques (such as camera distance and perspective) as well as the discourse relations holding between the shots and segments identified in the commercials. The findings show that the company mainly uses one specific type of rhetorical structure, the narrative commentary, that puts the social actors shown in many different scenes into the foreground and therefore strongly focuses on the company's strategy of positive social behavior.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has immensely challenged social and cultural life in recent years with drastic restrictions on social gatherings and engagement. These restrictions have not only affected many of the normal social conventions and typical procedures of daily life but also quickly changed the communication about it. In this paper, we address one particular way of this kind of revised communication with an empirical multimodal analysis of TV commercials by the company Heineken. By zooming in on their specific video montage structures and techniques to tell stories about the “new” life of their customers at home during the lockdown, we aim to show how a fine-grained analysis of the technical elements and the resulting rhetorical patterns helps outlining the particular strategies used in marketing campaigns that needed to adjust to the pandemic circumstances.

The marketing sector has in fact rapidly identified the need for such adjustments, especially those campaigns that promote products that are often consumed together, such as (alcoholic) beverages or food, for example. While smaller brands initially suspended their current campaigns, many larger and global companies showed immediate reactions and used their campaigns to call for solidarity and social distancing. Coca Cola, for example, used the Time Square advertising billboard in New York for promoting “Staying apart is the best way to stay united” by pulling apart the letters of their brand name1 and McDonald's similarly revised their famous “golden arches” by putting them further apart (see Valinksy, 2020). Hence, these companies revised the verbo-visual arrangement of their logos and brand names to illustrate and directly demonstrate the social adjustments and modifications.

Other brands such as Guinness and Burger King called for social distancing by showing images of a sofa or the ingredients for a self-made burger at home; other companies such as Jack Daniel's or Budweiser invited people to cheer for the new actions that are needed during the pandemic, such as, for example, “making social distancing social”2.

Our focus in this paper lies on the company Heineken and its global initiative promoted with the hashtag #socialiseresponsibly. The company is already known for their efforts to contribute to the environment and sustainable living, e.g., by scaling up green electricity and biogas (see Pearce, 2020) or aiming for sustainable low carbon glass bottles (see Pearce, 2021). They also follow strategies for responsible drinking with campaigns such as “Enjoy Heineken Responsibly” or “When you drive, never drink”. During the pandemic, Heineken has launched the #socialiseresponsibly initiative by first promoting their campaign “Ode to Close” in April 20203. On their website, they explain it as follows and invite to spread the message by sharing the initial video with the same title:

“Holding hands is on hold. Can't say hi up close let alone high-five. Back-pats have to be held back. Heineken® has been bringing people close for over 150 years. In this new normal we will keep doing that by encouraging people to socialize responsibly. Connect online. Toast your friend over a con-call, send a message of care to your bestie. Stay apart but stay together because we're in this together and soon we'll be together again!” (https://www.heineken.com/dz/fr/campagnes/socialise-responsibly, accessed March 1, 2022).

Since then, the company has posted a diversity of videos all accompanied by the hashtag #socialiseresponsibly and promoted on several social media platforms. While earlier ones support several of their campaigns for social distancing and the “new normal” of being at home (“Connections” and “We'll Meet Again”), later ones accommodate recent changes in the pandemic circumstances and call for responsible gatherings in bars as part of their campaigns “Back to the Bars” (July 2020) or “A Lockdown Love Story” (November 2021). With this, the company accommodates the many challenges that their marketing strategy was confronted with, including not only the promotion of their own products, but at the same time marketing social responsibility as well as creating awareness of the risks that heavy consumption of alcohol might bring under pandemic circumstances.

Interestingly, most of the videos used in this larger initiative follow a more or less uniform marketing style, usually known as “cause marketing” (cf. Rego and Hamilton, 2021). This business practice is part of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities in which companies use their business practices to improve social wellbeing (cf. Kotler and Lee, 2005). While some interest is currently focusing on the perception of such marketing strategies during the pandemic (e.g., Marinelli, 2021; Martino et al., 2021), our own interest lies in the products of these marketing strategies, the commercials themselves, and in the question of how the audio-visual and multimodal arrangement of the videos, i.e., their filmic montage, supports this kind of business practice and the resulting persuasive purposes. We think that it is particularly the homogenous structure and design of the videos that not only presents a coherent and uniform campaign but also efficiently communicates its overall message of socializing responsibly. As Forceville (2007, p. 17) suggests, “advertising has straightforward purposes: the bottom line is that it makes positive claims about a product or service” and this “unequivocally steers and constrains the construal and interpretation of any meaningful element a commercial might contain”. While Forceville himself focuses on metaphors as such meaningful elements in Dutch TV commercials, we are particularly interested in the specific texture of the Heineken videos which we assume to be very typical for the genre of television commercials and whose overall coherence and unity supports the construal of positive claims about the Heineken product and their social responsibility idea.

In the following, we will therefore ask how exactly the videos are multimodally structured to meet these persuasive goals of advertising while at the same time being entertaining and addressing the personal experiences of their customers. A detailed analysis of the videos' texture in terms of their rhetorical structure will show that not only the marketing strategy in all Heineken commercials is uniform and coherent, but also and in particular the structural arrangement and design of the videos. This formal homogeneity and overall coherence of the marketing strategy facilitates the reception of the video, their persuasive messages, and with this also supports the achievement of social wellbeing.

In order to show how the multimodal arrangement of the videos directly enables the interpretation of these positive claims, we will pursue our analysis with a framework that is based on previous work in the context of film and TV analysis and puts a strong emphasis on the rhetorical structure of audio-visual artifacts (see Bateman, 2007, 2013; Wildfeuer, 2014, 2018; Drummond and Wildfeuer, 2020). Building on the basic question of how “signifying substances” are used in film and how they take up structural rules (cf. Metz, 1974; Bateman and Schmidt, 2012), the main aim of this analysis is to find out how the various expressive resources (such as moving images, camera editing techniques, music, sound, etc.) work together intersemiotically to “provide cues concerning the ‘structure' that a viewer is being invited to attribute to a film as it unfolds” (Bateman and Schmidt, 2012, p. 92). We seek to outline how the Heineken videos provide such cues for the message of social responsibility during the pandemic via their specific rhetorical structure. In the next section we will explain the theoretical background of this framework and the details of aiming at a description of the structural consequences of audio-visual material. On this basis, we will demonstrate the material and analytical framework and present the results of our corpus analysis. The discussion will then evaluate Heineken's audio-visual strategy more closely and critically.

Analyzing the Rhetorical Structure of TV Commercials

Commercials shown on TV and/or published online on YouTube are complex multimodal, i.e., audio-visual artifacts that construct their meaning with the help of diverse semiotic modes, such as moving images, spoken and written language, music, lighting, etc. The interplay of these forms, or modes, their intersemiosis (cf., e.g., Liu and O'Halloran, 2009; Wildfeuer, 2012), is often described with regard to the discursive structure they construct, e.g., in the form of a narrative (as in films and TV series) or with a more documentary, explanatory, rhetorical, or persuasive purpose (see, e.g., Van Leeuwen, 1991; Bateman and Schmidt-Borcherding, 2018; see also the different contributions in Pennock-Speck and del Saz-Rubio, 2013). TV commercials often combine several of these purposes by telling a short story and at the same time following the communicative goal of advertising, i.e., promoting a product and persuading people to take the action shown or suggested in the commercial, i.e., buying it and enjoying it in a specific surrounding or with friends and family, for example.

In order to achieve this goal, commercials provide reasons to their audience in order to persuade them of the validity of the call for action by implicitly expressing the standpoint: “You should buy product X” (see Van Eemeren et al., 2002; cf. Wildfeuer and Pollaroli, 2018 for movie trailers as a specific type of commercials). In the case of Heineken, this standpoint is expanded by the idea of social responsibility: “You should buy product X—and consume it responsibly”. According to the principles of Pragma-Dialectics (Van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 2004; Van Eemeren, 2010), this standpoint is usually a practical standpoint which is often supported by evaluative ones that say something about the quality of the product or give reasons why it is good to act responsibly. These evaluative standpoints are then supported by arguments that are constructed multimodally—and several recent approaches provide frameworks for analyzing this multimodal construction of the argumentation in advertisements or similar genres (see, e.g., Kjeldsen, 2012; Rocci et al., 2013).

In this paper, we will not focus on the exact reconstruction of these standpoints and the accompanying arguments, but instead on the rhetorical structure of the commercials and the discursive unfolding of their story and/or the argumentation. The latter is consequently not seen as an internal property of the multimodal artifacts, but as a process of building a plausible interpretation of the standpoints according to rhetorical patterns in the text (Van den Hoven and Yang, 2013; see Wildfeuer, 2018). Following Van den Hoven and Yang (2013, p. 409), with these rhetorical patterns, “the rhetor attempts to reinforce or alter the way an audience perceives its reality”4. In their analysis, the authors identify mimetic and diegetic relations in audio-visual texts that “account for the rhetor's pragmatic intention, which is the change that the rhetor tries to establish in the audience's perception of its reality” (Van den Hoven and Yang, 2013, p. 409).

While a general interest on rhetorical patterns in both visual as well as audio-visual advertisements is to be observed for quite some time now (see, e.g., McQuarrie and Mick, 1999; Van Enschot et al., 2008; Urios-Aparisi, 2009; Pollaroli and Rocci, 2015; Bort-Mir, 2021), the particular focus on rhetorical relations as argumentative means has only more recently come to the fore (cf. Labrador et al., 2014; Wildfeuer, 2018). Similarly, there are now several approaches to audio-visual analysis within the multimodality context (including our own work) that provide frameworks for a clear identification of these relations and for a precise examination of the relational meaning-making and abductive reasoning as part of the recipients' cognitive capacity (e.g., Van Leeuwen, 1991; Tseng and Bateman, 2012; Wildfeuer, 2014). A triangulation of these approaches seems a very promising and fruitful endeavor for the analysis of rhetorical patterns in audio-visual communication (see also the discussion in Wildfeuer, 2018).

One of the approaches from a multimodality context that will serve as a starting point for the analysis in this study is the notable work by John Bateman who developed a comprehensive framework for describing structural consequences in film in his “grande paradigmatique of film” (2007). Bateman's (2007) reorientation of the “language-film analogy” from perspectives adopted especially by Metz's (1974) grande syntagmatique ensures the fine-grained analysis of the filmic montage both on the syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes of the filmic discourse level.

In the context of film studies, “montage” is usually understood as a technical term for filmic structuring in general. It is concerned with editing filmic material by arranging shots according to an idea a director or producer wants to communicate (Reisz and Milar, 1971). This use of montage has also largely characterized television production and products such as commercials or documentaries adapt this technique to organize their discourse for audience consumption. Although montage is well researched in film (and TV) studies, there seems to be surprisingly inadequate literature on such description of its contribution to multimodal meaning making in television contents like commercials, music videos, documentaries and news programs, especially given the fact that television and film have similar processes of production and meaning creation as well as adopting the spatiotemporal resources that are used in their textual makeup. In available works that discuss “montage” itself from a multimodal perspective, it is seen as a semiotic mode that contributes to the meaning-making processes (Bateman et al., 2017)—and this then builds on the “similarity between inter-shot filmic relations, on the one hand, and the inter-clausal discourse relations or linguistic connectives on the other” (Tseng and Bateman, 2012, p. 103).

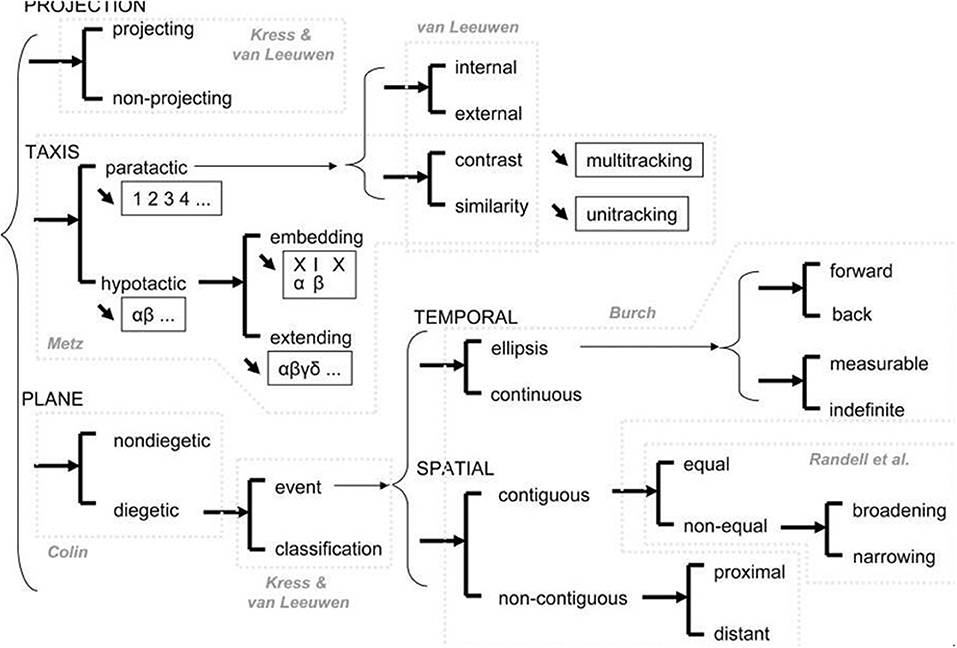

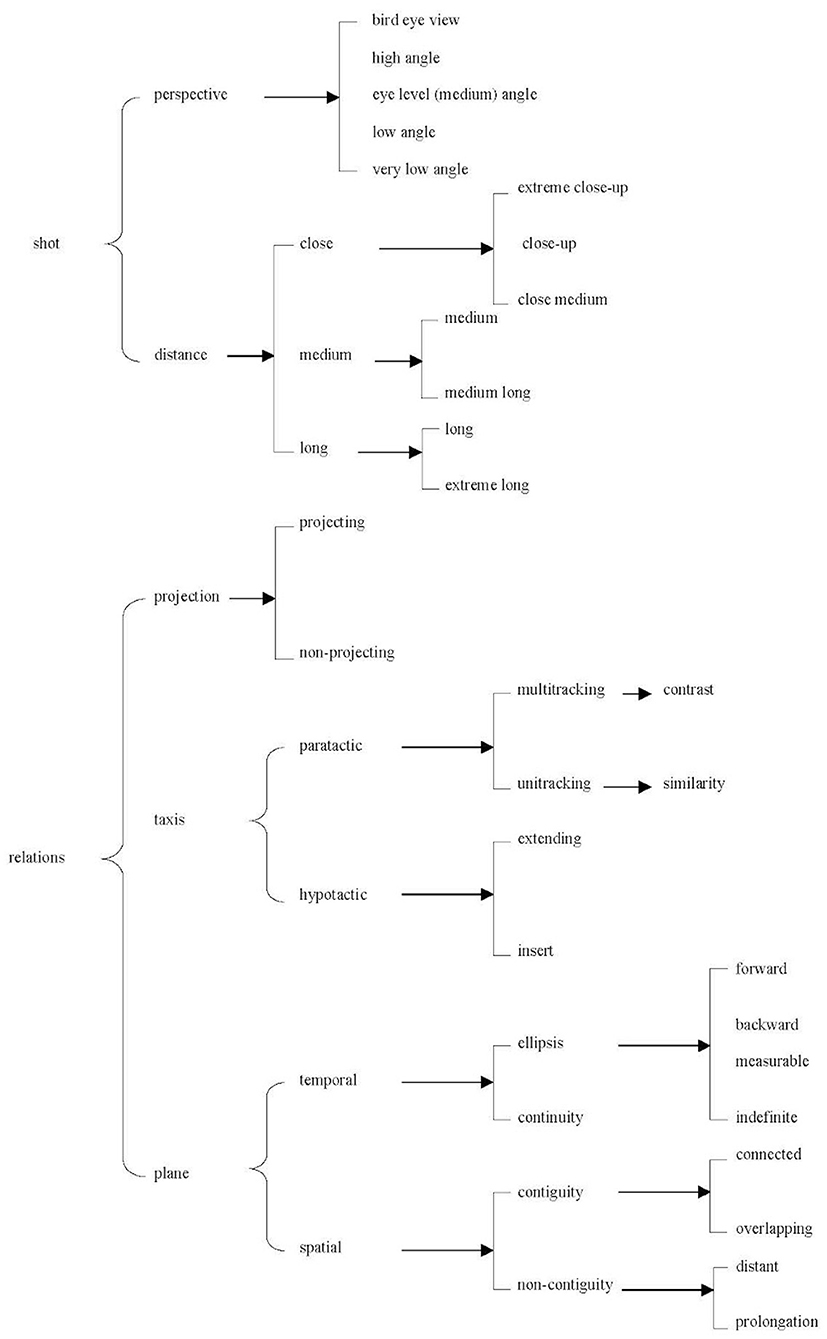

Bateman's model of the “grande paradigmatique” is given in Figure 1. The system network5 characterizes three major components whose realizations lead to further choices: projection, taxis, and plane. The first component, projection, has the subclassifications of projecting and non-projecting and describes whether the relationship between two separate elements is dependent on some form of sensing. In film, a point-of-view shot clearly defines projection, while flashback and flashforward describe a non-projecting relation between shots. Taxis describes syntagmatic dependencies of segments and has the two general subclassifications of hypotaxis and parataxis. Hypotactic structures establish some subordinating structural organization with options such as extending or embedding ideas or elements. Paratactic syntagmatic structures on the other hand do not have a typical subordinating relation. Their organizational structures are more coordinating and independent, compared to hypotactic structures. The paratactic multitracking structure requires at least four consecutive elements in the sequence to establish an alternation situation. Unitracking, in contrast, is a sequence of similar independent elements with no interdependency or subordinate relation. The plane component focuses on the spatiotemporal qualities inherent in the segment or individual elements. The temporal relationship may for example be continuous or ellipted with further realizations, while spatial relations classify contiguous and non-contiguous delicacies with further choices. Time is described as continuous, if events in the previous element or sequence seem to be continued in the next, it is ellipted if there is evidence of difference in time. Space or locale is described as connected when there is identification of some features from the previous element also present in the next element. It is however prolonged or distanced when there is no such evidence. More details of these components are given in Bateman (2007); they build the basis for the annotation scheme developed for the analysis of the Heineken corpus.

Figure 1. The grande paradigmatique developed by Bateman (2007).

The initial work by Bateman (2007) has been taken up in the broader socio-functionally oriented approach by Bateman and Schmidt (2012) and we will elaborate further on the frameworks' methodological input for the present study in the next section. So far, it has largely been used in the analysis of feature films with no evidence of its application to television commercials. However, Bateman (2013, p. 659) himself argues that it is very possible to analyze rhetorical strategies like those inherent in verbal language by focusing on the discourse stratum of film and describing relationships between all sorts of audio-visual shots with regard to their dependency structures and temporal and spatial coherence, for example. We similarly argue for such an analysis in Wildfeuer (2018, p. 24) by addressing the “question of how filmic and other multimodal discourses argue without directly delivering propositionally expressed arguments”.

In the following, we will direct this question to the corpus of Heineken commercials by using a multimodal annotation approach and by analyzing the discursive and rhetorical structure of these commercials from a more quantitatively-oriented perspective, i.e., in all 15 commercials of Heineken's initiative. For this, we orientate toward the general trend in multimodality research to achieve a stronger empirical foundation for the analysis of multimodal artifacts (see Bateman, 2013; Pflaeging et al., 2021) by applying the qualitative analysis of rhetorical relations as provided in Bateman's framework to our corpus and by describing patterns and systematic overlaps between the various commercials. We develop an annotation scheme for the description and annotation of both technical details such as camera perspective, for example, as well as the discourse analytical details of finding rhetorical relations between audio-visual units. With this, we locate our analysis within the context of empirically-driven corpus analysis and address the particular “need to cater for multi-level annotations that provide information concerning various facets of the material under study, ranging from technical features, to transcriptions of selected perspectives on the data […], to hypotheses about category attributions to individual segments or units, and the relationships between them” (Bateman, 2014, p. 23; Pflaeging et al., 2021, p. 251). We will explain the methodological details of our analysis, which are based on a pilot study with a corpus of Ghanaian TV commercials, and the annotation scheme in the following.

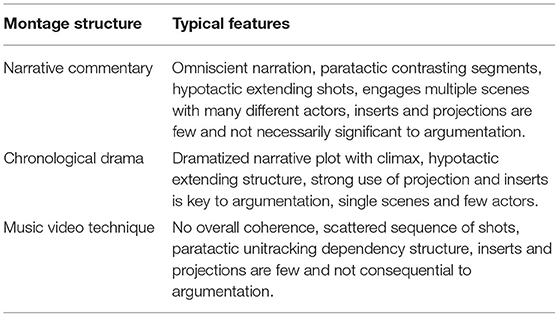

Methodological Framework, Annotation Scheme, and Corpus

As indicated above, our analysis of the Heineken corpus builds on a pilot study of analyzing Ghanaian alcohol beverage TV commercials that the second author has pursued as part of his PhD dissertation. The aim of this pilot project was to examine how these commercials are structured to meet persuasive goals of advertising while being informative, educational and entertaining. The study adopts the framework of the grande paradigmatique developed by Bateman (2007) and Bateman and Schmidt (2012, see also above) and identifies three specific montage structures used in advertising alcohol on television in Ghana: the narrative commentary, the chronological drama, as well as the music video technique. All three structures use specific features that can be identified with the analytical levels of the grande paradigmatique, i.e., according to patterns of plane, taxis, and projection. We explain these structures and the general functionality of the framework with a short example analysis of one of the commercials from our corpus.

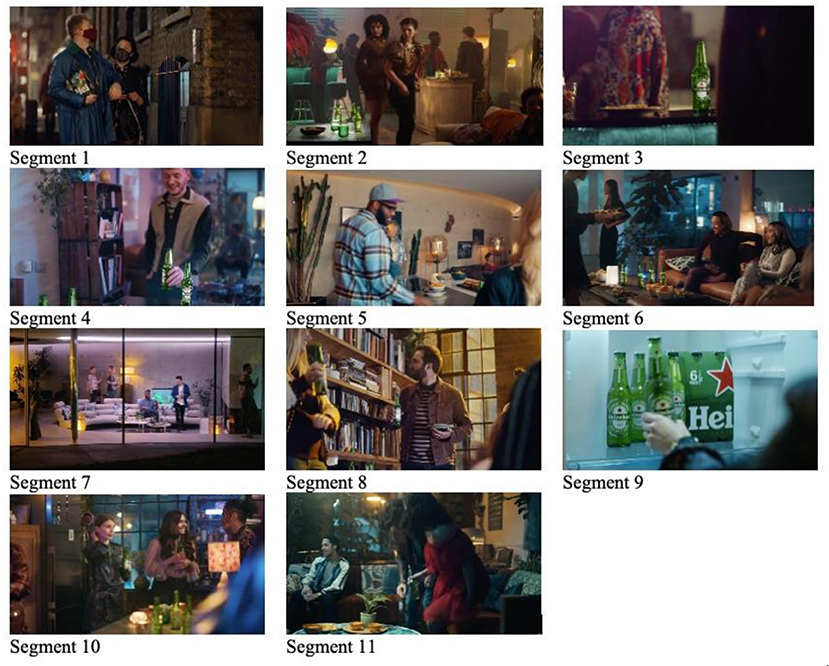

The commercial “Home Gatherings” was produced in May 2021 as part of Heineken's initiative to continuously inform and encourage consumers to socialize responsibly during the pandemic. Since the commercial is one of those produced post-lockdown, the message is highlighted using various gatherings of people in homes. The commercial is 62 s long and has a total of 52 shots that are combined into 11 different discourse segments6. Figure 2 gives an overview of these segments and we will focus on two of these for an in-depth analysis in the following: segment 2 and segment 9.

Segment 2 has a total of four shots, presented by screenshots in Figure 3. The segment begins in shot 7 of the commercial and ends with shot 10. The first shot is a medium long shot centralizing two women standing among a group of people in what seems to be a home party. The women gaze at two bottles of Heineken behind them. The next shot focuses on two Heineken bottles on a table in the background of shot 7. Also present in the shot is a hand reaching for either bottle. The third shot in the sequence is a low angle medium shot of the women, with the outstretched arm of one of them toward the bottles. The final shot of the segment is a medium close-up of the women which highlights the confusion on their faces because they are unable to identify each other's bottle. Rhetorically, this segment clearly underscores and acknowledges some challenges consumers of Heineken are likely to face post-lockdown when people resume socializing in places and at events like home parties, clubs, and bars. Structurally, the segment is very subordinative. The various shots are organized hypotactically to extend ideas sequentially and chronologically: Shot 8 is a continuation of shot 7, while shot 9 is subordinate to shot 8 and shot 10 also continuous from shot 9. From the sequence, it is also clear that action and participants are presented in continuous time and a contiguous space or location. There is also a projecting relation between shot 7 and 8. In shot 7, it is obvious that the direction of the gaze of both centralized participants is toward the Heineken bottle, and this is made clearer in shot 8 using a point-of-view technique. The resulting relation (extending, connected and continuous, projecting) from this analysis together with the various camera techniques become the basis for the preferred interpretation of this segment. It is the starting point and sometimes the major semiotic mode for meaning making in such complex multimodal constructions.

Segment 9, represented in Figure 4, is constructed out of five shots. By the end of the 5th shot, a different rhetorical argument is made compared to the rhetoric in segment two, yet the structure remains unchanged. The segment begins with shot 38 of the commercial and continues until shot 42. In shot 38, we see a close-up shot of a hand reaching for a bottle of Heineken in an open fridge packed with the product. Shot 39 is a medium shot that provides a wider perspective of all other participants gathered around a table and captures a woman writing on a bottle. This is made clearer in shot 40, with a close-up shot of the labeling action or process. The next shot uses a similar camera distance to focus on the various participants' hands holding the bottles labeled with their names. Shot 42 reverts to a wider camera distance which captures all participants in full as they raise their bottles and converse. As mentioned above, the rhetorical argument projected in this sequence contrasts the sequence in segment 2. While the message in segment 2 is related to challenges Heineken consumers face because of dynamics in social convention introduced by the pandemic, the argument in segment 9 could be associated with solutions to these problems. Rhetorically, the sequence proposes a creative solution as simple as labeling the bottles for easy identification, so people do not get confused and drink from other people's bottles. From a discourse organization perspective, the segment is equally subordinative since the dependency relation between all five shots is hypotactic extending. The location is connected, and all five shots show events in real time. There is also a projection relation between shots 39 and 40 because viewers are shown what is written on the bottle in shot 40 from the point of view of the woman holding the bottle in shot 39.

In total, both segments provide a highly extending hypotactic syntagmatic construction of ideas. Since the individual segments each represent independent ideas and follow their own internal organization, their overall inter-segment construction is paratactic and there is no consistency in their spatiotemporal connection. The identified discourse structure represents one of the three specific types of montage structures that have been identified in the pilot study, the so-called narrative commentary. Narration in this kind of structure is used from an omniscient point of view and unfolds within several different segments, but not as an overall construction. For the corpus of Ghanaian alcohol commercials, it could be observed that the strong but varied representation of characters in several paratactic arrangements in this type of commercials allows recipients to directly associate with one or more characters. This is very similar in our example commercial in which a variety of people is shown drinking alcohol in different settings.

Another type of commercial identified for the Ghanaian corpus is the chronological drama which entertains viewers with a narrative plot that signifies the importance of the alcoholic beverage. In this type, a dramatized narrative becomes the ultimate persuasion element with a climax that highlights the values and (assumed) positive attributes or qualities of the product. The structure used to construct this narrative is mainly hypotactic and ensures that viewers are able to follow the story until the end. Projection is also highly used in this structure, while space and time are almost always connected. The third type of commercials is the so-called music video technique in which ideas or shots seem to lack coherence and are usually scattered with no clear pattern. It is thus very difficult to detect discourse units relevant for viewers to understand the commercial from a shot-by-shot perspective. However, these types of commercials still show spatial and temporal relations that are almost always connected. The dependency structure is best described as a paratactic unitracking, since the shots are autonomous and only pick out characters at random. In addition, coherence is often established via the music used in these commercials.

Table 1 gives an overview of all three montage structures identified in the pilot study on Ghanaian alcohol commercials. With the present study, we aim at identifying similar structures in the corpus of Heineken commercials and at evaluating whether the company uses a coherent montage style or specific rhetorical patterns to promote their product and the accompanying social issue of acting responsibly. Since the analysis of montage is closely connected to the technical details of camera perspective and distance, we are also interested in analyzing these more closely in each video.

Table 1. Overview of montage structures as identified in the pilot study on Ghanaian alcohol commercials.

For this, we developed a multi-level annotation scheme that is first of all based on the system network of the grande paradigmatique by Bateman (2007) and expanded by a level of description for the filmic technical elements of camera perspective and camera distance. Figure 5 presents the annotation scheme as a whole. Similar to other multi-level annotation schemes used for film and TV, the square brackets in this scheme represent mutually exclusive, “either/or” choices; round brackets, in contrast, stand for “and” choices and connect systems which are available simultaneously (see also Drummond and Wildfeuer, 2020, p. 40).

Figure 5. System Network for the annotation of rhetorical relations between shots in the Heineken commercials.

As becomes visible, on the highest level, the scheme differentiates between “shot” and “relations” as basic analytical units. A shot is usually seen as the outcome of some identified cut or transitional element in the audio-visual material, it is commonly defined as the basic filmic unit, although many studies also often focus on larger segments or sequences. In this project, we take the shot as the starting unit for the description of the camera perspective and distance as very foundational technical details. For each shot, we describe both the camera perspective and the camera distance with a pre-given choice of technical terms adopted from film studies which we use as a controlled vocabulary.

For each successive pair of shots, the analysis then establishes, on the second level of description, the paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations that hold according to the framework of the grande paradigmatique (see the example analysis above). We work successively through all three levels of the framework and describe the relation between the shots according to projection, taxis, and plane. In the evaluation of the results, we aim at bringing the analysis of the formal details together with the discourse analytical examination of the relations between the shots.

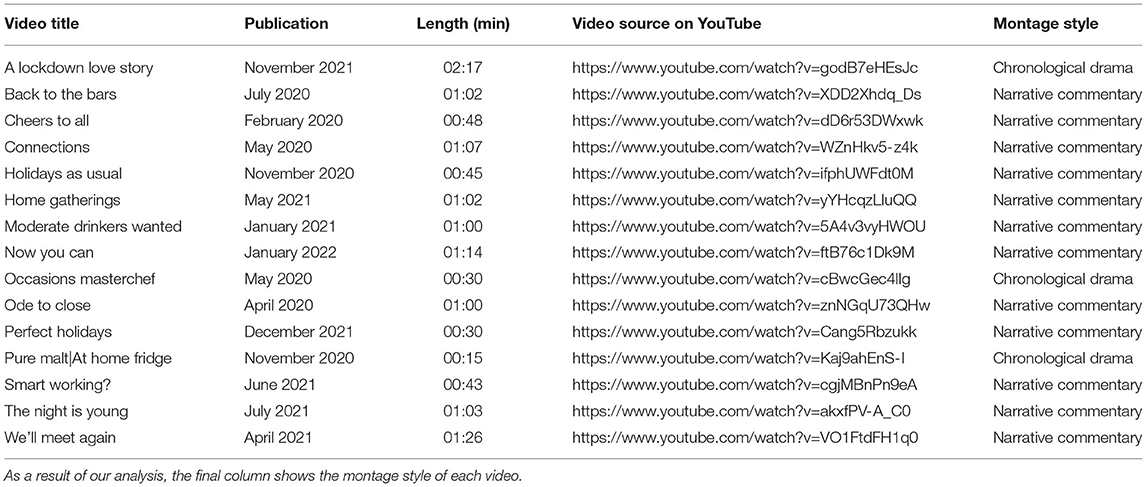

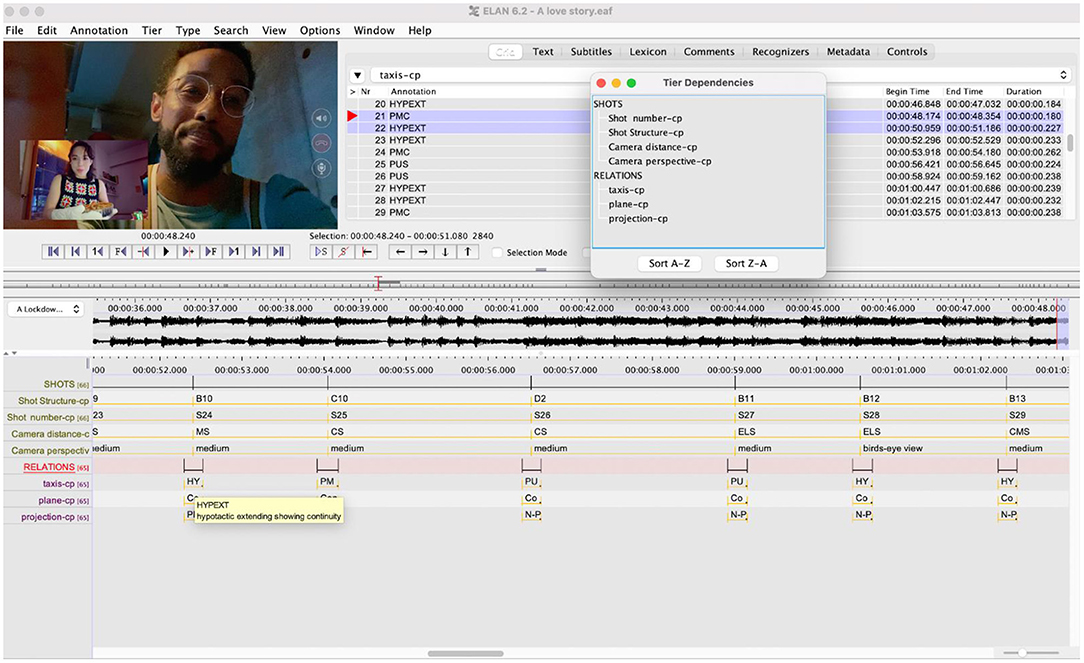

Our corpus contains 15 commercials that have been published by Heineken during the years 2020 and 2022. All of them can today be found on YouTube and we provide an overview of the videos and their sources in Table 2. All 15 commercials are annotated with the help of the annotation tool ELAN provided by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics (see Wittenburg et al., 2006; https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan). The linear display of the audio-visual material in ELAN ensures easy identification and coding of the properties of our system network. For this, we transferred and adapted it into a specific ELAN template with specific tiers to annotate the respective units and features. This means that both the technical aspects of each shot (i.e., camera perspective and camera distance) as well as the relation between the shots are annotated on the respective tiers. Relations between segments are annotated, respectively. Figure 6 gives a screenshot of the ELAN template and annotation for the analysis of the video “A Lockdown Story” as well as an overview of the different tiers and their dependencies we use for all videos. Each tier is tied to a so-called controlled vocabulary which provides all relevant annotation choices for this respective tier, i.e., the choices available in the system network given in Figure 5. While the annotation of shots is very straightforward, the annotation of relations between shots and segments is more challenging in that these relations represent results of inferential reasoning that happens “between” the units, but is of course not part of the material itself and thus does not take up any actual time code in the annotation. For the representation of the relations in the coding, we therefore decided to use short segments ranging from one shot (or segment) to the other and to annotate them with the controlled vocabulary available. This allowed us to later extract frequency values for the relations in each commercial and to say something about the construction of montage structures out of these relations.

Figure 6. Screenshot of our ELAN template for the analysis of “A Lockdown Story” with the tier dependencies in a separate window7.

Results

We structure the following presentation of the results of our annotation according to the scheme presented in the previous Section, i.e., on the two levels of description for (1) the technical details of the shots and (2) the rhetorical relations as well as the resulting discourse structure and type of commercial as identified above.

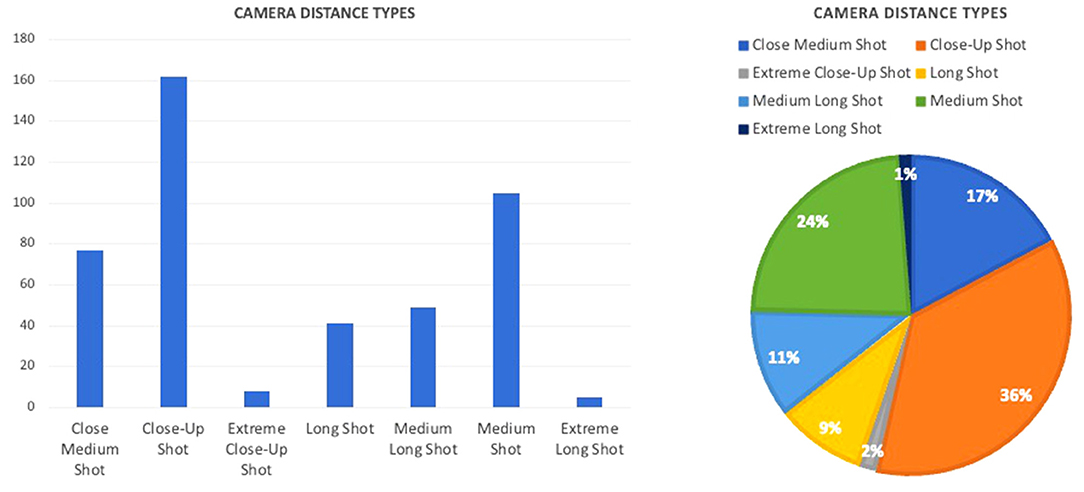

We start with the results for camera distance and camera perspectives in order to determine the shot characteristics that are dominantly used for the construction of the commercials. The choices for camera distance range from close-up shots to extreme long shots, and the findings suggest that the close-up shot is the most dominant type used in the Heineken campaign, namely in 36% of the shots. This is followed by the medium shot and then the close-medium shot with 24 and 17%, respectively. Long distance shot types, i.e., long shot (9%) and extreme long shot (1%) as well as the extreme close-up shots (2%), were the least used types in the corpus. Figure 7 gives an overview of the camera distance types identified in the 15 commercials.

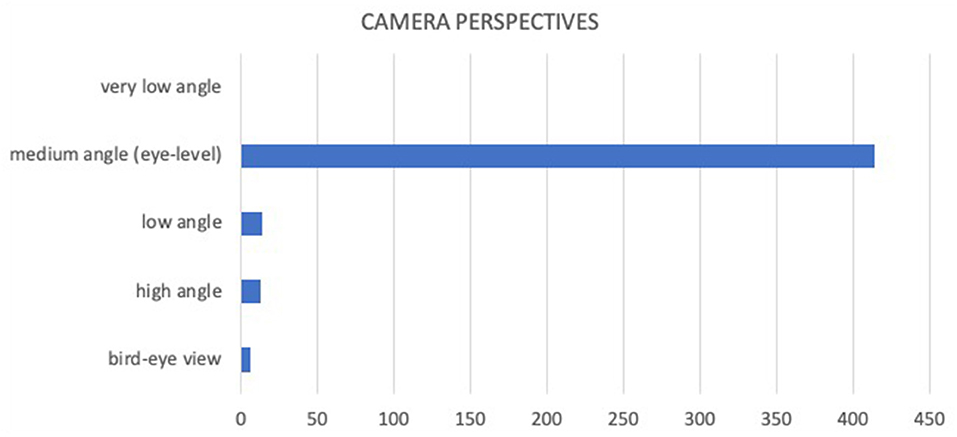

Our scheme also examined camera perspectives such as bird-eye view, very low angle, low angle, eye level or medium angle, and high angle. From the total 447 shots from all 15 commercials, the eye level perspective (medium angle) was overwhelmingly used in 414 occasions, i.e., in over 90% of all cases, with scattered instances of both high and low angles and only six records of the bird-eye view. This distribution is detailed in Figure 8.

The second level of our analysis focuses on the relational elements that construct the argumentative or rhetorical structure of the Heineken corpus. We examine taxis, plane, and projection to determine both inter-shot and inter-segment dependencies, as well as contextual relations of time and space that logically contribute to the interpretation of the commercials.

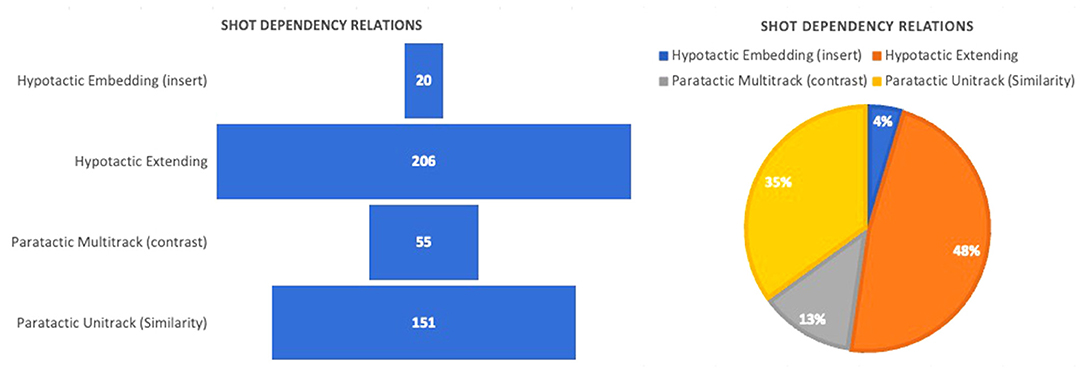

The results of our analysis of the four dependency types that make up taxis suggest a general preference for the paratactic unitracking relation and the hypotactic extending relation. As becomes visible in Figure 9, the hypotactic extending relation can be identified in most of the shot dependency relations; 48% of the relations between shots reveal this type, followed by the paratactic unitracking (35%), the paratactic multitracking (12%) and the hypotactic embedding (5%), respectively.

At the segment level, only two dependency relations are identified: the paratactic unitracking is used in 80% of the commercials and the hypotactic extending is adopted in the remaining 20%. Thus, in 12 commercials, the rhetorical structure consists of hypotactic extending relations when organizing shots, and paratactic unitracking at the segment level.

Following the analysis, these structural constructions in 12 of the commercials can be identified as narrative commentary, because lower-level shots are subordinate while higher level segments are independent (see also the last column in Table 2). For instance, several smaller sequences of individual shots might be used to describe the individual behavior of several actors in specific settings and these segments are shown in parallel, but chronology is only achieved within the shots that make up independent segments—and not via the overall structure of the whole commercial. At the segment level, relations between the individual segments are coordinative, offering a variety of similar events that are independent of each other.

In the remaining 3 commercials in the corpus, the organization is much simpler. Hypotactic extending structures organize the narrative at both shot and segment levels. Whether in multiple or single segment TVCs, ideas are constructed chronologically at both levels to ensure easy interpretation. The relations at both ends are subordinative and always rely on previous elements to make complete meanings. One particular example is the video “A Lockdown Love story” in which various scenes in different settings and moments tell the story of two characters who meet in an online game during the pandemic and share their lockdown lives and the resulting virtual relationship in messages and video calls for a while afterwards. The rhetorical construction of this video (and the other two commercials) is consistent with the chronological drama structure identified and discussed in the pilot study presented above.

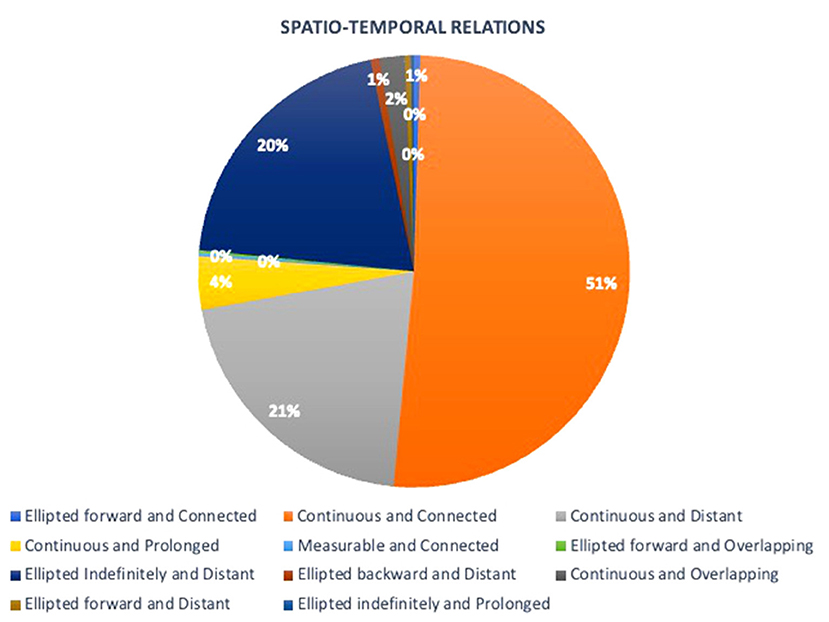

On the level of plane, which examines variations in the contiguity of space and continuity of time, our analysis reveals 11 different combinations of spatio-temporal relations used in the Heineken corpus. These combinations can all be detected at both the shot and segment level and our results suggest that at the shot level in most commercials time is continuous, and space is connected, which is consistent with the dominant hypotactic extending relations revealed on the level of taxis. Connected space and continuous time account for 51% in our analysis, followed by distant space and continuous time with 21%. These combinations describe situations where different people in different locations are presented in real time. For instance, people in different pubs, clubs, and parties at night or people in different locations joining the same virtual meeting and platforms. When ellipted, time is indefinite, and the location is usually distant. Thus, the relation of time between shots cannot be measured and their spatial qualities have no apparent similarities. This relation also accounts for 20% of spatio-temporal descriptions within shots. Figure 10 illustrates this distribution.

At the segment level however, indefinite time and distant space accounts for the majority of the spatio-temporal relations within segments. Fifty-three percent of our corpus use this relation to show various actors behaving in a similar manner. In six other commercials (40%), the relation describes a prolonged space and continuous time, where some spatial properties of the previous segment are found in the next segment. One commercial for instance shows an action that takes place with a friend on a dance floor in a club and another action at the counter with the bartender. Finally, structures with hypotactic extending relations usually have continuous and connected spatio-temporal relations, but this applies to only three commercials in our corpus.

Finally, projection, as the third level of description, is rarely used in our corpus. Only 18% of relations at the shot level show such qualities. However, whenever projection is used, there is a direct relationship between the product and the actor or one actor and another actor. From the actor's point of view, shots are contrasted to reveal a multitracking during dialogue or hypotactic embedding (inserts). At the segment level, projection is non-existent in both dramatized and commentary rhetorical structures.

Discussion

On the basis of the results reported for all annotation levels, we are now able to paint a better picture of the overall structural arrangements of the videos in our corpus and to connect these to the persuasive purpose of Heineken's #socialiseresponsibly strategy. We will structure this section similarly to the steps we followed for the presentation of the results and give a broader conclusion at the end.

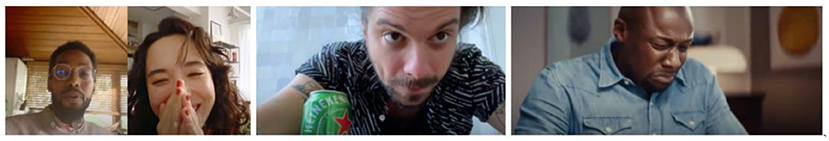

When looking at the use of camera perspective and distance in the videos and comparing this to the pilot study of Ghanaian commercials, the distribution in the Heineken corpus is consistent with the Ghanaian television commercials and shows typical patterns of audio-visual artifacts with smaller shot counts. The overall dominant use of close-up shots can be explained when looking at what is shown in the respective videos. Commercials that were produced and published during the early stages of the pandemic emphasized working from home and thus used these shots to highlight how different individuals could stay apart and still socialize responsibly using a host of social and new media platforms. In almost all 15 commercials, the close-up shot is also used to capture the product as well as highlight the facial expressions or reactions of people toward the socially accepted behavior of others. Figure 11 gives screenshots of some of those shots.

Figure 11. Screenshots of close-up shots from “A Lockdown Story”, “Connections”, and “Occasions Masterchef”.

Some commercials also use a higher number of close medium shots to show how hard people are trying to virtually connect and socialize during lockdown periods. Building on qualitative analyses of shots and other forms of images as representing particular kinds of social relations between the producer and the viewer (see, among many others, Kress and van Leeuwen, 2006; Zappavigna, 2016), we conclude from these results that the tallies of close-medium and medium shots therefore also underscore the social relationship represented in the commercials. They establish a more equal and socially accepted identification of viewers with the represented actors in the commercials. In contrast, medium shots were used mostly in videos that were published after times of lockdown, when people were allowed to go back to bars and parties. Consequently, these videos exactly capture different actors in bars and parties adjusting to the new normal and finding creative ways of being socially responsible as well as physically engaging with the product. Long shots, in contrast, were sparingly used for defining the immediate setting of a video, establishing the number of people present or showing how the actions contribute to the rhetorical argument of the commercial.

The use of one dominant camera perspective, i.e., the medium angle, in the corpus is similarly consistent with other audio-visual arrangements that represent participants whose features and roles are carefully constructed to identify with the audience. Consequently, the viewers of the Heineken videos are invited to accept the experiences of the represented participants or actors of the commercials as theirs when presented from an equal or eye level angle. It is thus unsurprising that regardless of the structural type of the video or the pandemic period in which it was published, many shots adopt this perspective. In the rare instances where the low angle is used, these shots highlight a specific action of the actors that has interpretational consequences for the commercial. For instance, in the video “Smart Working”, the low angle is used to reveal the action of the participants that try to hide people or objects in their surroundings or the Heineken bottle from the frame during online conferences or meetings on virtual business platforms. Figure 12 gives examples for these shot types. High angles were also sparingly used either as variations of the same shot in a sequence and do not necessarily have interpretational consequences. There were no records of the very low angle, while the bird-eye angle always provides an aerial view and a much wider perspective of the setting, although usually with no argumentative contribution.

Figure 12. Screenshots of shots with a low angle perspective from “Connections” and “Smart Working”.

Not only with regard to the choice of camera perspective and distance, but also and more particularly by looking at the rhetorical structure analysis reported in our results, we can summarize that the strong focus of Heineken's marketing strategy on the social behavior of their clients is mirrored directly in the multimodal arrangement of the videos. In both single and multiple scene commercials, the discourse structure is using a hypotactic extending pattern which shows different actors socializing responsibly in many different, but comparable ways. This kind of narrative commentary puts the product itself more in the background of the overall message, although it is itself dominantly visible in all videos via close-up or medium close-up shots.

The particular focus on the social actors in the Heineken videos allows further interesting observations: As an international brand, such a strategy seems rather apt, considering the heterogeneity of their audience. The majority of commercials promoting Heineken or similar products are often centered around sporting activities like soccer and Formula 1. However, in previous campaigns, there was a stronger focus on a single plot or story-point which ensures chronology. Although Heineken does not totally abandon this rhetorical structure in the #socialiseresposibly campaign, their aim is now to point to a broader argumentative strategy of identifying with more people in different situations rather than focusing on only a few individuals and advancing a single plot8. In mostly single scene commercials, narration is arranged chronologically to inform viewers of how people engage with the product and still act responsibly. On the shot level, projections and inserts are weaved into the structural organization to establish viewer perspectives and to identify specific social behaviors. Typical camera techniques include the medium shot, close-up shot and the medium close-up, as often used in dramatic genres. Unlike pre-pandemic commercials that adopt more unusual camera perspectives for dramatic effects, the angles used in our corpus are direct and at eye-level.

The dominance of hypotactic extending shots and paratactic contrasting segments points to the specific holistic approach of Heineken's strategic marketing. Parties in homes, clubs, and bars are usually major settings in alcohol commercials because they are typical social centers where alcohol is consumed. In pursuing responsible social behavior during the pandemic, Heineken adopted similar segments of different scenes to showcase how different people and groups in areas such as bars, homes, and clubs should act responsibly. Although the primary objective is to marketize the Heineken product, more emphasis is placed on the several hypotactically organized shots that construct responsible social behavior. Single autonomous shots or multiple short length shots are used in these situations to establish why people should buy Heineken and how they should consume the product responsibly. For instance, in the post-lockdown commercials “Home Gathering” that we analyze above, paratactic segments organize different situations where people find alternate ways to keep their bottles apart or separate, so they don't mistakenly drink from other people's bottles. As explained before, the commercial first establishes confusion over the new normal and ends with several creative measures people take to identify and keep apart their half-consumed Heineken from the cluster.

The rhetorical and relational structures discussed above offer valuable insights into montage as a semiotic mode in television production, and more importantly as a resource for organizing meaning in television commercials. As argued by Pennock-Speck and del Saz-Rubio (2019), studies on the multimodality of television commercials have not sufficiently investigated this mode of meaning making, probably due to theoretical inadequacies and methodological deficiencies. Our approach in this study offers a more comprehensive and exhaustive theoretical and methodical alternative to how rhetorical structure and argumentation are examined in audio-visual artifacts. By following functional perspectives, we have demonstrated how the logical organization of meaning is as crucial to interpretation as the represented resources in television commercials. The relational consequences we have identified in our corpus also affirm that television commercial genres could be identified by logical organizations of the audio-visual object, and not only through promotional stylistics like “problem-solution” techniques that have largely been discussed in previous studies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^See, e.g., https://adsofbrands.net/en/ads/coca-cola-staying-apart/12070 (accessed March 1, 2022).

2. ^See the ad “With Love, Jack” by Jack Daniel's: https://youtu.be/nmVRFui61U4 (accessed March 1, 2022).

3. ^Ode to Close on Youtube (2020). Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=znNGqU73QHw (accessed March 1, 2022).

4. ^Similarly, Alcolea-Banegas (2009, p. 270) defines filmic arguments as “the rhetorical and pragmatic effect(s) of the audiovisual discourse. In its action, the discourse reveals the consistency of rational argument and the efficiency of persuasive force”.

5. ^The framework is modeled as a so-called system network as long established for the description of linguistic details within the context of systemic-functional linguistics. Language in this context is seen as a “resource” for meaning-making which is characterized in terms of classificatory “networks of choice” that also show associated structural consequences, called realizations. Any linguistic unit is described by setting out the “abstract semiotic choices” that would lead to the construction, or “realization” of the unit in question.

6. ^A shot as a result of some identified cut or transitional element is usually seen as the basic filmic unit. Following Bateman (2007) Bateman and Schmidt's (2012) framework for the analysis of the rhetorical structure, however, the analytical unit of analysis is a segment which takes into account larger features like discourse barriers within a scene that again is defined by spatio-temporal circumstances such as the setting and time.

7. ^We thank the reviewers for insightful comments on our work and in particular the annotation scheme. One of them suggested making the scheme available for the research community through a central repository. Due to potential copyright issues with the video files, we decided not to do this, but we are happy to share the ELAN template or some other details of the scheme with everyone interested via email.

8. ^An additional observation we made during our analysis is the fact that with this Heineken also encourages diversity in their commercials. There seems to be more focus on the representation of gender, race, body type, and, to a large extent, also on age in the promotion of the product. To substantiate these observations further and find empirical evidence, additions to the annotation scheme in the form of categories for the representation of these identities and a more detailed analysis of these categories would of course be necessary.

References

Alcolea-Banegas, J. (2009). Visual arguments in film. Argumentation 23, 259–275. doi: 10.1007/s10503-008-9124-9

Bateman, J. A. (2007). Towards a grande paradigmatique of film: Christian Metz reloaded. Semiotica 167 4, 13–64. doi: 10.1515/SEM.2007.070

Bateman, J. A. (2013). Hallidayan Systemic-Functional Semiotics and the Analysis of the Moving Audio-Visual Image. Text & Talk. 33, 641–663, doi: 10.1515/text-2013-0029

Bateman, J. A. (2014). “Using multimodal corpora for empirical research”, in The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, 2nd Edn, ed. C. Jewitt (London: Routledge), 238–252.

Bateman, J. A., and Schmidt, K.-H. (2012). Multimodal Film Analysis: How Films Mean. London: Routledge.

Bateman, J. A., and Schmidt-Borcherding, F. (2018). The communicative effectiveness of education videos: towards an empirically-motivated multimodal account. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2, 3. doi: 10.3390/mti2030059

Bateman, J. A., Wildfeuer, J., and Hiippala, T. (2017). Multimodality Foundations, Research, Analysis. A Problem-Oriented Introduction. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bort-Mir, L. (2021). Developing, applying and testing FILMIP: the filmic metaphor identification procedure (PhD thesis). Castellón de la Plana: Universitat Jaume I.

Drummond, T., and Wildfeuer, J. (2020): “The multimodal annotation of gender differences in contemporary TV series,” in Annotations in Scholarly Editions Research. Functions, Differentiations, Systematization, eds J. Nantke, F. Schlupkothen (Berlin: de Gruyter), 35–58.

Forceville, C. (2007). Multimodal metaphor in 10 Dutch TV commercials. Public J. Semiotics I 1, 15–34. doi: 10.37693/pjos.2007.1.8812

Kjeldsen, J. E. (2012). “Pictorial argumentation in advertising: visual tropes and figures as a way of creating visual argumentation,” in Topical Themes in Argumentation Theory. Twenty Exploratory Studies, eds. F. H. Van Eemeren and B. Garssen (Dordrecht: Springer), 239–255.

Kotler, P., and Lee, N. (2005): Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company Your Cause. Hoboken: John Wiley.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. 2nd Edn. London: Arnold.

Labrador, B., Ramón, N., Alaiz-Moretón, H., and Sanjurjo-González, H. (2014). Rhetorical structure and persuasive language in the subgenre of online advertisements. English Specific Purp. 34, 38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2013.10.002

Liu, Y., and O'Halloran, K. L. (2009). Intersemiotic texture: analyzing cohesive devices between language and images. Soc. Semiotics 19, 367–388. doi: 10.1080/10350330903361059

Marinelli, L. (2021). CSR in the Time of Coronavirus. A Qualitative Study on the Perception of Coronavirus Cause Marketing Relief Response from the Perspective of Consumers. Master Thesis, Norwegian School of Economics. Available online at: https://openaccess.nhh.no/nhh-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2770090/masterthesis.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (accessed January 7, 2022).

Martino, F., Brooks, R., Browne, J., Carah, N., Zorbas, C., and Corben, K. (2021): The nature extent of online marketing by big food big alcoholic during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: content analysis study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 7, 3. 10.2196/25202 .

McQuarrie, E. F., and Mick, D. G. (1999). Visual rhetoric in advertising: text-interpretive, experimental, and reader-response analyses. J. Cons. Res. 26, 37–54. doi: 10.1086/209549

Pearce O. (2020): Heineken Announces its Achievement in 100% Green Energy. World Branding Forum. Available online at: https://brandingforum.org/featured/heineken-announces-its-achievement-in-100-green-energy/ (accessed December 7, 2021).

Pearce, O. (2021): Heineken and Glass Futures Collaborate on Low Carbon Glass Innovations. World Branding Forum. Available online at: https://brandingforum.org/featured/heineken-and-glass-futures-collaborate-on-low-carbon-glass-innovations/ (accessed December 7, 2021).

Pennock-Speck, B., and del Saz-Rubio, M. M. (2013). The Multimodal Analysis of Television Commercials. Valencia: University of Valencia Press.

Pennock-Speck, B., and del Saz-Rubio, M. M. (2019). The pragmatic-semiotic construction of male identities in contemporary advertising of male grooming products. Discour. Commun. 13, 2. doi: 10.1177/1750481318817621

Pflaeging, J., Wildfeuer, J., and Bateman, J. A. (eds.), (2021). Empirical Multimodality Research. Methods, Evaluations, Implications. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Pollaroli, C., and Rocci, A. (2015). The argumentative relevance of pictorial and multimodal metaphor in advertising. J Argument. Context 4,158–200. doi: 10.1075/jaic.4.2.02pol

Rego, M. M., and Hamilton, M. A. (2021). The importance of fit: a predictive model of cause marketing effects. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 33, 434–456. doi: 10.1080/10696679.2021.1901594

Rocci, A., Mazzali Lurati, S., and Pollaroli, C. (2013). “Is this the Italy we like? Multimodal argumentation in a Fiat Panda TV commercial,” in The Multimodal Analysis of Television Commercials, eds B. Pennock-Speck and M. M. del Saz Rubio (Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de València, PUV), 157–187.

Tseng, C., and Bateman, J. A. (2012). Multimodal narrative construction in Christopher Nolan's Memento: a description of method. J. Visual Commun. 11, 91–119. doi: 10.1177/1470357211424691

Urios-Aparisi, E. (2009). “Interaction of multimodal metaphor and metonymy in TV commercials: four case studies,” in Multimodal Metaphor, eds C. Forceville and E. Urios-Aparisi (Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton), 95–118.

Valinksy, J. (2020). McDonald's and Other Brands are Making 'Social Distancing' Logos. CNN Business. Available online at: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/26/business/social-distancing-brand-logos-coronavirus/index.html (accessed December 7, 2021).

Van den Hoven, P., and Yang, Y. (2013). The argumentative reconstruction of multimodal discourse, taking the ABC coverage of President Hu Jintao's visit to the USA as an example. Argumentation 27, 403–424. doi: 10.1007/s10503-013-9293-z

Van Eemeren, F. H. (2010). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse: Extending the Pragma-Dialectical Theory of Argumentation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Van Eemeren, F. H., and Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Van Eemeren, F. H., Grootendorst, R., and Snoeck Henkemans, A. F. (2002). Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Van Enschot, R., Hoeken, H., and van Mulken, M. (2008). Rhetoric in advertising: attitudes towards verbo-pictorial rhetorical figures. Inform. Design J. 16, 35–45. doi: 10.1075/idj.16.1.05ens

Van Leeuwen, T. (1991). Conjunctive structure in documentary film and television. Continuum 5, 76–114. doi: 10.1080/10304319109388216

Wildfeuer, J. (2012). Intersemiosis in film: towards a new organisation of semiotic resources in multimodal filmic text. Multi. Commun. 1, 276–304. doi: 10.1515/mc-2012-0016

Wildfeuer, J. (2014). Film Discourse Interpretation. Towards a New Paradigm for Multimodal Film Analysis. London: Routledge.

Wildfeuer, J., and Pollaroli, C. (2018). When context changes: the need for a dynamic notion of context in multimodal argumentation. Int. Rev. Pragm. 10, 179–197. doi: 10.1163/18773109-01002003

Wittenburg, P., Brugman, H., Russel, A., Klassmann, A., and Sloetjes, H. (2006). “ELAN: a professional framework for multimodality research,” in: Proceedings of LREC2006, Fith International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. Available online at: http://www.lat-mpi.eu/papers/papers-2006/elan-paper-final.pdf (accessed March 1, 2022).

Keywords: rhetorical structure, core marketing, social responsibility, multimodal annotation, TV commercials

Citation: Wildfeuer J and Coffie JA (2022) #socialiseresponsibly. Analyzing the Rhetorical Structure of Heineken TV Commercials During the Pandemic. Front. Commun. 7:887706. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.887706

Received: 01 March 2022; Accepted: 02 May 2022;

Published: 31 May 2022.

Edited by:

Hartmut Stöckl, University of Salzburg, AustriaReviewed by:

Sabine Tan, Curtin University, AustraliaIlaria Moschini, Università di Firenze, Italy

Lara Portmann, University of Bern, Switzerland

Copyright © 2022 Wildfeuer and Coffie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Janina Wildfeuer, j.wildfeuer@rug.nl

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Janina Wildfeuer

Janina Wildfeuer Joseph Adika Coffie

Joseph Adika Coffie