Refining concepts for empirical multimodal research: defining semiotic modes and semiotic resources

- Centre for Language and Linguistics, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, United Kingdom

The issue of defining key concepts in multimodal research is at the same time ongoing and of pivotal importance. Building on John Bateman’s categorisation of modes, and paying special attention to the concept of materiality within the discussion, the paper provides a clear differentiation between semiotic modes and semiotic resources and discusses the relationship between the two. These will be defined by also looking at how they differ from another key concept in multimodal research, i.e., media, and examples will be provided to illustrate how the newly defined concepts can guide empirical investigations of multimodal texts and their reception. The paper aims to continue the discussions around these key concepts amongst multimodal scholars, so that agreement in the field can eventually be reached.

1 Introduction

The issue of defining key concepts in multimodal research is at the same time ongoing and of pivotal importance. This paper aims to contribute to ongoing discussions by offering a clear differentiation between semiotic modes and semiotic resources as well as a discussion of the relationship between the two. Although the concept of semiotic mode is of key importance to multimodal research, a review of the literature in the field shows, at best, contrasting definitions and, at worst, the suggestion that a clear understanding of what modes are may be of no use at all. The last stance is the one taken by Machin (2013) who asserts that, since it has proved very difficult to ascertain what constitutes modes, “MCDS (Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies) may turn out to have less use with the issue of what modes are in themselves as with how different kinds of semiotic resources can play a part in realising discourses since they are good at doing different things” (p. 349). Notwithstanding the importance of the last part of his assertion, I believe it may be equally difficult to establish what different things modes are good at if we do not first establish what they are.

A similar point can be made for the concept of semiotic resources, which is sometimes seen as an overall umbrella term for anything that can be used for meaning-making, and whose nature and composition is often vaguely defined. Indeed, as Bateman (2021a, p. 56) states:

Considerable theoretical uncertainty therefore remains concerning just how potentially “overlapping” semiotic systems might best be approached, both theoretically and practically during analysis. This is not helped by the fact that the notion of “semiotic resource” is also intrinsically vague — anything that may serve a semiotic purpose may be a resource: van Leeuwen even writes, for example, of “genre” being a semiotic resource (Van Leeuwen, 2005: 128). This does not provide support for empirical analysis.

The starting point for clarifying the ontological status of modes and resources, as well as the relationship between the two, will be the definitions of semiotic modes provided by Bateman (2011, 2016) and Bateman and Schmidt (2012). After revisiting some of the literature definitions around the concepts of modes and resources, a proposal is put forward to differentiate between the two. The differentiation is based on the (relatively) stable material properties of semiotic modes and on the ability of semiotic resources to be deployed and articulated through different materialities. Semiotic resources are then categorised in this present paper by drawing on the Systemic Functional Linguistic (henceforth SFL) ideational, interpersonal and textual metafunctions (e.g., Halliday, 1978), and four dimensions are discussed: discursive resources, pragmatic resources, stylistic resources and textual resources. Finally, a proposal is put forward to place semiotic resources at an intermediate stratum between paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation, and discourse semantics within the composition of a mode. The reason for this, the paper argues, is that this intermediate stratum will help explain how the semiotic codes, by which I refer to the first two strata in Bateman’s (2011) model, take the specific configurations that allow to activate certain interpretations (and not others) at the final stratum of discourse semantics.

A discussion about semiotic modes and semiotic resources, however, cannot do without addressing another key concept in multimodal research, namely media. By looking at all three concepts, i.e., modes, resources and media, a central role is attributed to the material dimension of signification and interpretation. On the one hand, the paper argues that materiality is a key constitutive component of modes and media, both of which rely on relatively stable and historically developed material substances. On the other hand, it is argued that materiality, despite gaining importance once semiotic resources are deployed in actual texts, does not represent a constitutive element of semiotic resources, which are instead defined as abstract metafunctional constructs that can be realised through different materialities and/or semiotic codes.

The paper begins by discussing and defining semiotic modes and semiotic resources as well as by clarifying the relationship between the two. Since, however, “we do not find ‘free-floating’ instances of semiotic modes,” media will also be discussed, as they “group semiotic modes dynamically into socioculturally and historically situated configurations” (Bateman, 2017, p. 168). The role of materiality for multimodal research will then be discussed in order to establish two parallel lines of empirical enquiry. The first is how the materiality of the signs and sign systems affects their deployment in communication; the second is how socio-cultural conventions, as well as technological advancement, shape and alter the range of material configurations that can be deployed through specific modes, media and genres. These will be further explored in the following section, which outlines implications for empirical multimodal research and offers pointers for potential research endeavours that can focus both on text production and text reception at three different levels of analysis (cf. Bateman, 2021b, pp. 3–4): (i) investigating which semiotic resources and metafunctions individual modes can actualise; (ii) investigating the relationship between different modes actualising the same semiotic resources and metafunctions; (iii) investigating the contribution of individual modes to perform the three metafunctions of a communicative event.

2 Semiotic modes

The most problematic issue with defining and categorising modes seems to be the difficulty to establish clear boundaries between them (Machin, 2013, p. 349). Within many approaches to multimodality, however, modes have been generally equated to systems of signs, e.g., speech, writing, gestures, sounds, etc. (Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001, p. 6; p. 9; Forceville, 2009, p. 23; Page, 2009, p. 6; Kress, 2010, p. 79; Stöckl, 2014). Kress (2010, p. 87) identifies both a social and a formal dimension of modes, with the former relating to specific communities and their contingent “social-representational needs,” and the latter aligning with Halliday’s (1978) three metafunctions (i.e., ideational, interpersonal and textual). The formal dimension in Kress’ formulation (built on Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996), however, has been criticised on the grounds that not all modes seem to be able to fulfil all the three metafunctions (Van Leeuwen, 1999, pp. 190–191; Bateman, 2021b, p. 4) and that not all modes can and should be treated in the way language has within the SFL tradition (Machin, 2016, p. 327).

One notable exception to the equation of modes with sign systems is O’Halloran (2005, pp. 20-21) who maintains that modes are related to the sensory channels of communication, while defining the systems of signs as semiotic resources. The latter view, however, has been criticised on the grounds that “modes cut across sensory channels, so the nature of a sign is not sufficiently characterised by looking at its path of perception” (Stöckl, 2014, p. 11). A similar point is made by Bateman (2021a, pp. 49–50), who also highlights how the “conflation of the material and the semiotic, mak[es] analysis and demarcation of data unnecessarily complex.” In agreement with Stöckl and Bateman, the five senses of seeing, hearing, touching, smelling and tasting will be understood in this paper to refer to sensory channels and not modes.

Notwithstanding the need to avoid conflating the material and the semiotic, Bateman (2011) and Bateman and Schmidt (2012) claim that the materiality of the medium as well as that of the systems of signs, need to be taken into consideration for a full account of what modes are and therefore do not provide a list of modes but, rather, a breakdown of the layers of a “three-stratal organisation” that comprise modes, namely (i) a material substrate; (ii) paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation (e.g., a lexicon and a grammar in the case of language); (iii) a discourse semantics through which the ‘semiotic code’, defined as the combination of (i) and (ii) above, becomes interpretable, and hence a “fully fledged semiotic mode” (Bateman, 2011, pp. 20–22).1 Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) also stress the importance of the discursive dimension of modes by stating that these “allow the simultaneous realisation of discourses and types of (inter) action” (p. 21).

The material substrate in the first stratum allows the signs and the sign systems to be perceivable and, at the same time defines them. As for the second stratum, i.e., “paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation”, Bateman and Wildfeuer (2014, p. 186) maintain that “this ‘mid-level’, or mediating stratum generally operates compositionally and can be characterized independently of context.” The final stratum, discourse semantics, provides the connecting ‘tissue’ between the “somehow ‘interpretable’ in context” (Bateman, 2011, p. 21) “semiotic code” and its situated communicative enactment by “provid[ing] the pragmatic interpretative mechanisms necessary for relating the forms a semiotic mode distinguishes to their contexts of use and for demarcating the intended range of interpretation of those forms” (ibid, p. 181, emphasis in original). It can be argued, however, that within this definition it remains unclear just how the paradigmatic and syntagmatic structures in the first two strata take the specific forms that constrain the interpretative options at the level of discourse semantics. The latter relies on elements that are already beyond the materiality of the semiotic code, e.g., genre recognition, recognition of metafunctions, cultural understanding and so on, and that, moreover, are very often performed by the combination of modes in complex multimodal artefacts (Bateman, 2021b, p. 4).

Two aspects of Bateman and colleagues’ work, however, already include a potential solution to the problem outlined above, and this is the use of the word “resources” at different stages in the development of the model to refer to the second stratum of their classification. Bateman (2011, p. 20) uses the concept of semiotic resources to describe “semiotically charged organisations of material that can be employed for sign-construction,” which in his theorisation equates to the second tier of the “three-strata organisation” of semiotic modes. More recently, Hiippala and Bateman (2021, pp. 407–408) refer to the second stratum as expressive resources, which are “assumed to be subject to a paradigmatic organization that allows making selections among them and combining them into larger syntagmatic organizations” and examples of which, within the context of a diagrammatic mode, are written language and line drawings. My proposal is that the construction and structuring of syntagmatic and paradigmatic resources within the actual deployment of a mode are not only constrained by the material qualities of the stratum below but also by abstract, potential metafunctional constructs that guide paradigmatic and syntagmatic choices and take specific forms at the discourse semantics stratum to activate certain interpretations and not others. An example is necessary at this stage to illustrate this line of thinking.

If we take the written language mode as deployed in an academic article, there will be a number of metafunctional considerations that will influence both the paradigmatic and syntagmatic levels in the second stratum of the model. Stylistic considerations, for example, will guide the choice of lexicon amongst the paradigmatic options by selecting more formal lexical options; likewise, at the syntagmatic level, certain syntactical structures will be preferred by selecting, in the case of English academic writing, subordinate clauses and passive voices. These choices are at the same time not a defining feature of the paradigmatic and syntagmatic structures of the written language code nor dictated by the internal structure of the code, but by the external socio-cultural expectations connected with the deployment of the mode for a specific communicative purpose. The stylistic metafunctional constructs considered at the paradigmatic and syntagmatic level, once selected and realised, will enable a restricted number of interpretations at the final level of discourse semantics.

However, if we accept the necessity to include this set of metafunctional constructs somewhere between the material substrate and the discourse semantics stratum, the question arises of where they should be placed in the model. One option is that the ‘expressive resources’ in the second stratum are expanded to include the metafunctional constructs alongside paradigmatic and syntagmatic options; another is to posit a further stratum that sits between the second and third strata of the model, thus creating a four-stratal model. Before being able to answer this question, however, the exact nature of these ‘resources’ needs to be established as well as their relationship with the strata as they currently appear in Bateman’s model. The following section will argue that the concept of semiotic resources, once clearly defined, can provide the answer to the question above.

3 Semiotic resources

As Van Leeuwen (2005, p. 3) states, the idea of semiotic resources is taken from Halliday’s SFL, in which grammar is described as a “resource for making meanings” (Halliday, 1978, p. 192). Van Leeuwen then goes on to give a detailed description of what this means:

In social semiotics resources are signifiers, observable actions and objects that have been drawn into the domain of social communication and that have a theoretical semiotic potential constituted by all their past uses and all their potential uses and an actual semiotic potential constituted by those past uses that are known to and considered relevant by the users of the resource, and by such potential uses as might be uncovered by the users on the basis of their specific needs and interests. Such uses take place in a social context, and this context may either have rules or best practices that regulate how specific semiotic resources can be used, or leave the users relatively free in their use of the resource (Van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 4; emphasis in original).

The way semiotic resources are defined in the quotation above means they encompass pretty much anything that can be used for meaning-making, provided that they are one of possible options from which users can choose and that they can be used following a more or less strict set of rules. It is for this reason that Kress and van Leeuwen (2001, pp. 21–22) suggest that not only modes but also media are examples of semiotic resources, once the “principles of semiosis [of media] begin to be conceived of in more abstract ways (as ‘grammars’ of some kind).” Despite the fuzziness of the boundaries of semiotic resources in van Leeuwen’s definition, and hence the difficulty to apply the concept in empirical investigations, it is important to note the point that the intended context of use will influence the choice of resources to be deployed, a point to which I will return later in this section.

Unlike Kress and van Leeuwen, O’Halloran (2005, p. 20) does not include media amongst semiotic resources and lists “speech, music and diegetic sound” (in effect what almost everyone else defined as modes) amongst examples of semiotic resources. Bateman (2011, p. 20) defines semiotic resources as “semiotically charged organisations of material that can be employed for sign-construction,” which, as we have seen in the previous section, equates to the second tier of their three-stratal organisation of semiotic modes. Machin and Mayr (2012), finally, do not define semiotic resources as such, but talk about lexical and visual repertoires, which are the two dealt with in their book, in lieu of semiotic resources. There is, therefore, either considerable overlap between modes and semiotic resources to the point that one of the terms becomes redundant, or a lack of clear boundaries, which conflates very different concepts under the same broad umbrella of meaning-making.

As Bateman (2021a, p. 55) notes, however, the conflation of semiotic modes with a broader notion of semiotic resources “results in ‘semiotic mode’ saying little more than is already covered by the term ‘semiotic resource’.” I would argue, therefore, that the effort to define semiotic modes has to be coupled with the effort to provide a clear definition and classification of semiotic resources. Providing clear-cut, discrete categories and constructs within the broad (and vague) umbrella of ‘resources’ allows researchers to focus empirical investigations, as I will show in section 6. It has to be stressed at this point that the categorisation of semiotic resources that follows is embedded within the composition of a semiotic mode, while, following van Leeuwen’s definition of semiotic resources quoted earlier, being also affected by the intended context of use in which the modes will be deployed.

To begin our categorisation of semiotic resources as part of a mode, I would argue that these can be defined as abstract, potential metafunctional constructs that can be realised through different materialities and/or semiotic codes. Bateman (2021a, p. 49) theorises a similar “‘abstract’ or ‘generalised’ materiality” when he discusses the concept of canvas. A canvas is defined as the materiality of a semiotic mode “when viewed with respect to the specific forms of traces required by that semiotic mode” (Bateman, 2021a, p. 46, emphasis in original). A parallel can be drawn with semiotic resources as they, too, albeit already existing as abstract constructs, will take different materialities and leave different traces, depending on the semiotic codes deployed to actualise them. It has to be noted at this point that the constructs I propose should be regarded as ‘code-dependent contributions of resources’ to communicative metafunctions and not as the overall final actualisation. For example, different modes will contribute different aspects to the genre of lectures, but their contribution will be guided by the semiotic resources component within the mode composition and, in turn, limit the possible genre recognition options at the level of discourse semantics (see further below). Now that an initial definition of semiotic resources has been offered, it is possible to address the question raised at the end of the previous section, that is whether semiotic resources should be placed with paradigmatic and syntagmatic structures in the second stratum of Bateman’s model, or whether a further stratum should be added to the model, thus making it a four-stratal one. Following an answer to this issue, I will then provide an initial, tentative categorisation of semiotic resources as belonging to four dimensions, discursive, pragmatic, stylistic and textual, based on SFL metafunctions.

I propose that the second option, that is an additional independent stratum that sits between paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation and the final stratum of discourse semantics, should be adopted for the following reasons. Firstly, semiotic resources, as I defined them, represent abstract, a-material options that are not dependent on the materiality of the first two strata, but that can take different forms in relation to the materiality and related affordances of the first two strata. They can therefore be applied, in an abstract fashion, to any semiotic codes. However, some resources and related metafunctions may not be available at all to some codes: Van Leeuwen (1999, cf. Bateman, 2021b, p. 4), for example, problematises the idea of modes being able to fulfil all metafunctions:

Looking back I would now say that different semiotic modes have different metafunctional configurations, and that these metafunctional configurations are neither universal, nor a function of the intrinsic nature of the medium, but cultural, a result of the uses to which the semiotic modes have been put and the values that have been attached to them. Visual communication, for instance, does have its interpersonal resources, but they can only be realized on the back of ideation, so to speak. If you want to say ‘Hey you, come here’ by means of an image, you have to do it by representing someone who makes a ‘Hey you, come here’ gesture. You cannot do it directly. With sound it is the other way around. Sound does have its ideational resources, but they have to be realized on the back of interpersonal resources (Van Leeuwen, 1999, pp. 190–191, emphasis in original).

Furthermore, combinations of these resources can result in other communicative constructs, such as rhetorical strategies, which Bateman (2014, p. 250) defines as “some binding of, on the one hand, communicative ‘goals’ […] and, on the other hand, selected realisation strategies ranging over any of the semiotic modes that can be mobilised in an artefact.” There is therefore an ontological difference between the materiality of the paradigmatic and syntagmatic structures on the one hand, and the a-materiality of the semiotic resources, together with their potential combination into communicative strategies, on the other, which would be best reflected by placing them in a separate stratum.

Second, an intermediate stratum between the bottom two (material substrate + paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation) and the top one (discourse semantics) is necessary to negotiate at an abstract level between two set of sign-making forces: the material affordances of the code on the one side, and the socio-cultural expectations surrounding the mode deployment through specific media and genres on the other. This abstract negotiation is then actualised in specific, material, interpretable discourse semantics. For example, if we posit that the stratum of discourse semantics can include pragmatic competence such as genre recognition (Bateman, 2017), then it necessarily follows that the mode must have had access to relevant pragmatic options (or any other metafunctional constructs) at a lower stratum so that the interpretability of the mode at the level of discourse semantics can be ‘activated’ and hypotheses can be generated which involve ascribing them to particular semiotic resources (Hiippala and Bateman, 2022, p. 16). This process of hypothesis generation and identification of semiotic resources must include both a stage where the intended ones are selected from the options at the lower stratum (i.e., the proposed additional stratum of semiotic resources), and a stage where an intended audience is able to generate abductive hypotheses based on the material traces of those selections, as crystallised in the final stratum of discourse semantics. The choice of which semiotic resources to draw on can therefore happen through both bottom-up (text producer-driven) and top-down (context-driven) factors, or, indeed and perhaps more likely, a combination of both. Bottom-up, the range of resources that can be accessed will depend on the material codes, and related affordances, at the disposal of the text producer; within the accessible range of semiotic resources for the codes selected, individual, stylistic preferences of the sign-maker may also influence the selection of specific resources. Top-down, the choice of resources will be influenced by the contingent socio-cultural expectations related to the genres and media through which communication occurs. These socio-cultural expectations will also guide the correct interpretation of the multimodal artefact based on the specific discourse semantics resulting from the contribution of the co-occurring modes.

Let us provide some examples of both processes at work, beginning with the bottom-up scenario and considering the institutional practice of giving a lecture. The text-producer will have, depending on the technology available in the classroom, a number of modes they can choose from, including spoken language, written language as deployed in hand-outs and digital presentation material, images, diagrams and other visuals as deployed in hand-outs and digital presentation material, to mention some of the most commonly used, say, in British Higher Education. We can focus on one of these modes, the spoken language, and on one of the pragmatic semiotic resources necessary to fulfil the purpose of ‘enabling teaching and learning’, that of text types.2 The text producer will choose to activate those text types that are deemed to be functional to that purpose, i.e., informative and descriptive. These will then require specific syntagmatic and paradigmatic configurations available at the lower stratum and, together, form the material basis of a specific discourse semantics which will allow, on the one hand, the text producer to construct the multimodal communicative act by harmonising the various contributing modes, and, on the other, will allow the students to recognise and interpret (not necessarily at a conscious level) the meaningful contributions of the individual modes for the purpose of teaching and learning. If, alternatively, we take the related but different practice of academic conference presentation, the text producer, through the spoken language mode (and indeed other co-occurring modes) will necessarily make use of other text types in addition to the informative and descriptive, i.e., the argumentative, that are necessary to fulfil the purpose of convincing an audience that the propositions advanced in the presentation are to be accepted as valid. One could argue that argumentative text types will also be necessary in a lecture and, to a certain extent, this is probably the case. However, given the audience (students) and their expectations of the practice (learning, developing intellectual skills), as well as the relative position of power of the ‘expert’ lecturer vis-à-vis the ‘novice’ student, the choice of text types will be skewed towards the informative and descriptive rather than towards the argumentative. The opposite would apply in the practice of conference presentation, where the audience (peers) and their expectations (being presented with something original and scientifically tenable) will skew the text type proportions towards the argumentative one.

The final observations regarding audiences and their expectations take us already in the realm of top-down processes, that is the context-driven ones. Beside considerations around audiences and their expectations, the limitations imposed by institutionalised practices will also influence the choice of semiotic resources the codes are allowed to activate. This is also in line with the point highlighted at the beginning of this section in van Leeuwen’s broad definition of semiotic resources, that is that the intended context of use will influence the choice of semiotic resources (cf. also Bezemer, 2023, p. 16). Since the discourse semantics stratum involves situated and contextual discourse interpretations (Bateman, 2011, p. 22), the options of semiotic resources to deploy in such situated and contextual discourses will also be influenced by the cultural and institutional limitations posed by specific contexts. We can explicate the top-down process with the institutional practices introduced above but this time we will work through the model backwards (i.e., from the higher strata to the lower ones). The lecture social practice, which can also be seen as a genre, is not the only available option to fulfil the purpose of ‘enabling learning and teaching’, seminars and workshops being other notable alternatives. However, the institutional practice may impose restrictions on which genre to be used at a specific time and place, as may do the technology available. In turn, the (imposed) choice of a lecture over a seminar or workshop will require a specific discourse semantics that needs to allow for specific interpretations, for example concerning the role of the participants, their relative power in the proceedings, interactional turns and so on. The desired discourse semantics will then draw on the best suited abstract semiotic resources available at the lower stratum and these will take specific forms depending on the semiotic codes that can be utilised depending on the canvas(es) available. Whether or not the choice of the semiotic resource is driven by bottom-up (i.e., text producer) or top-down (i.e., contextual) factors is irrelevant with regard to the status of semiotic resources, that is a set of abstract, a-material options available to perform metafunctions.

A similar line of reasoning can be followed for the other dimensions of the semiotic resources as I will categorise them. However, the examples provided should suffice to explicate the ontological status of semiotic resources as a set of abstract, a-material options available in relation to specific codes as well as the need to be placed at an intermediate stratum between paradigmatic and syntagmatic properties, and discourse semantics. Put differently, what I maintain is that the stratum of semiotic resources provides the metafunctional coordinates that dictate a certain organisation of the axes. So, although they are a-material, they guide the structuring of the syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes so that only certain actual interpretations can be made available at the level of discourse semantics. Without these set of coordinates, i.e., the semiotic resources as defined here, we are missing the link that allows to move from all the possible paradigmatic and syntagmatic structural options available to a code to the actual ones that lead to a specific discourse semantics. At the level of discourse semantics, the paradigmatic and syntagmatic structures have already taken specific material configurations, thus achieving an ontological status that is the sum of strata (ii) (paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation) and (iii) (semiotic resources). These new material, metafunctionally-loaded configurations at the level of discourse semantics need to be necessarily fixed (and no longer potential and a-material). Without a fixed materiality it would not be possible for modes to co-occur based “on the affordances of the materialities being combined” within a specific medium (Bateman, 2016, p. 56). This material ontology of the individual discourse semantics of modes is also highlighted by Bateman (2011, p. 27, my emphasis):

Providing a formalised account of the kinds of semantics that applies for each semiotic mode, together with a close mapping between properties of the articulated material and those semantics, is the first step towards a well-founded account of the semantics of modes both individually and in combination.

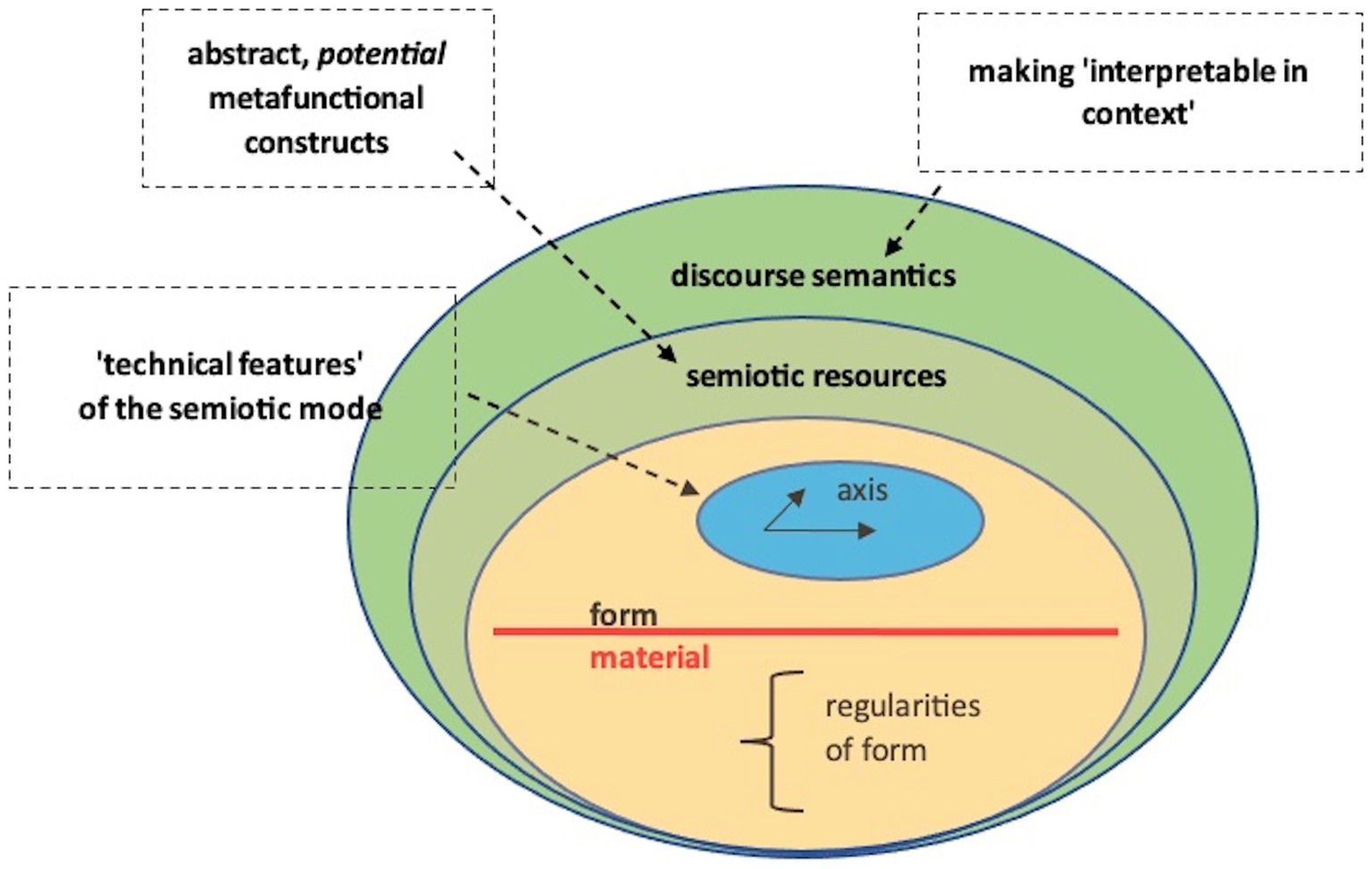

It has to be stressed, however, that the intermediate stratum I propose does not change the overall structure theorised by Bateman (2016), which sees the communicative event formed by modes interacting within specific media and being finally attributable to a genre that is recognisable by the participants in the communicative event. Based on the discussion so far, a four-stratal organisation of semiotic modes can be offered, which builds on the models discussed so far and comprises: (i) a material substrate; (ii) paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation; (iii) semiotic resources; (iv) discourse semantics. Figure 1 provides a schematic visualisation, based on Bateman (2016), of the expanded theoretical model of mode.

Figure 1. Visual schematisation of the expanded theoretical model of mode (after Bateman, 2016).

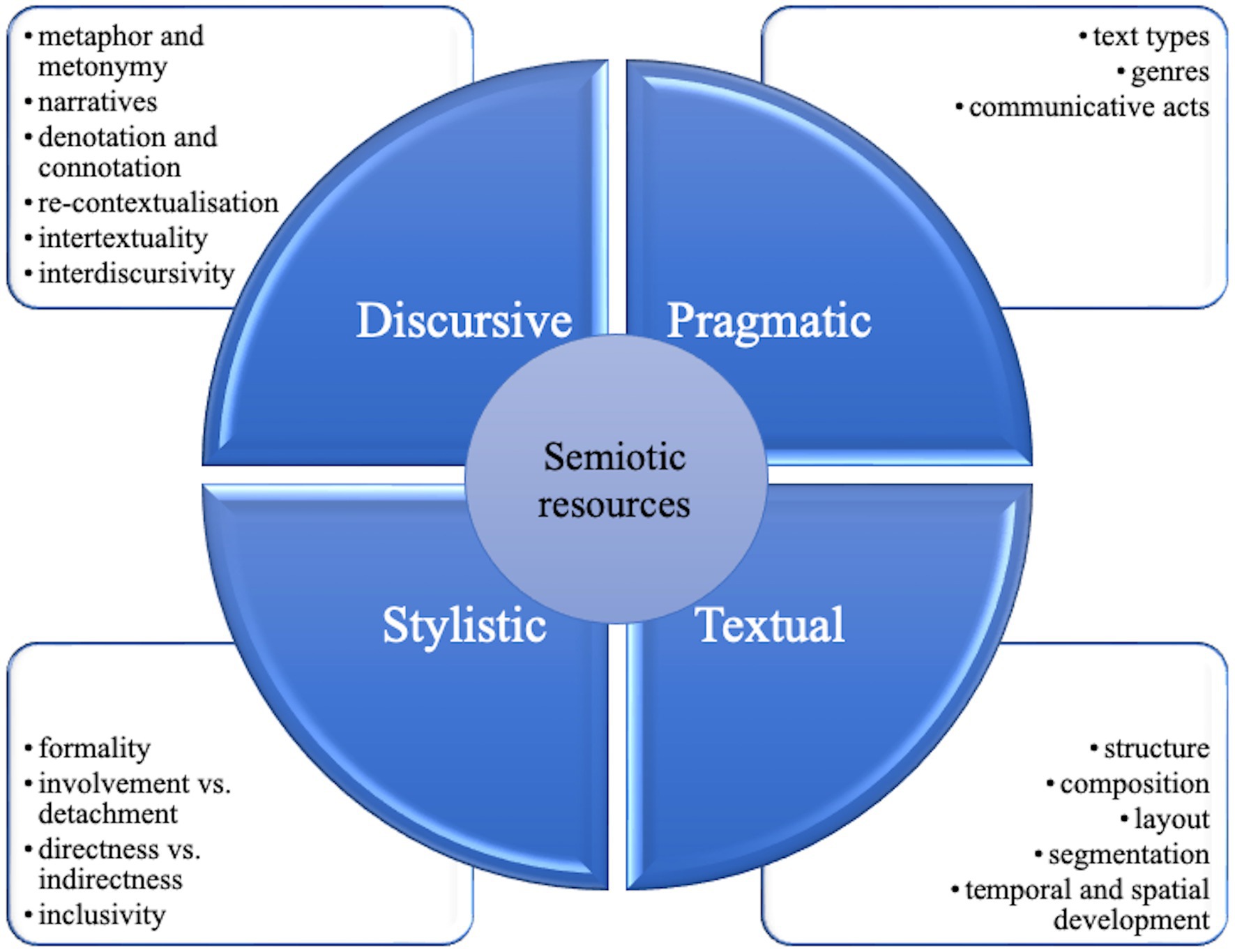

Now that the ontological status of semiotic resources and their relationship to modes have been established, we can move on to provide a finer categorisation of semiotic resources. To this purpose, I propose to arrange them into four macro areas: discursive, pragmatic, stylistic and textual. Discursive resources allow conceptualisation: they primarily attend to the content of communicative events and can be roughly equated with the SFL ideational metafunction. Examples of discursive resources include metaphor and metonymy, narratives, denotation and connotation, re-contextualisation, intertextuality and interdiscursivity. Pragmatic resources allow purpose: they primarily attend to the function of communicative events. Examples are text types (narration, report, description, exposition and argumentation), genres (travel documentaries, sci-fi films, etc.) and communicative acts (e.g., invitation, offer, command, request, etc.).3 Stylistic resources allow agency: they primarily attend to identities in communicative events. Examples are formality, involvement vs. detachment, directness vs. indirectness and inclusivity. Pragmatic and stylistic resources can be roughly equated with the SFL interpersonal metafunction. Finally, textual resources allow organisation: they primarily attend to the structure of communicative events and can be roughly equated with the SFL textual metafunction. Examples of textual resources include structure, composition, layout, segmentation, temporal and spatial development. Equating SFL metafunctions to the semiotic resources rather than to the semiotic modes gives the theoretical advantage to be able to account for those semiotic modes that do not present all three metafunctions (Van Leeuwen, 1999, pp. 190–191; Bateman, 2021b, p. 3), since these properties are now part of the semiotic resources. Figure 2 is a schematic representation of the semiotic resources as defined above, but the lists within each area should not be taken as exhaustive.

To summarise, this section aimed to provide clarifications and definitions on three fronts. First, it discussed the nature of semiotic resources and defined them as abstract potential metafunctional constructs. Second, it argued that a further stratum should be added to the theoretical definition of mode provided by Bateman and colleagues to accommodate the newly defined concept of semiotic resources, and discussed the relationship between the new stratum and those below and above it. Finally, it provided an initial, tentative categorisation of semiotic resources by grouping them under the categories of discursive, pragmatic, stylistic and textual and by equating them to the SFL ideational, interpersonal and textual metafunctions. The next section will look at the concept of media and discuss the relationship between semiotic modes, semiotic resources and media.

4 Media

A first, mostly agreed upon, distinction is made between modes and media and, accordingly, between multimodality and multimediality, with the former referring to the simultaneous deployment of different modes and the latter to the simultaneous deployment of different media. Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) refer to media as “the material resources used in the production of semiotic products and events, including both the tools and the materials used (e.g., the musical instrument and air; the chisel and the block of wood)” (p. 22, my emphasis) and connect media to the sensory system (ibid, p. 67). O’Halloran (2005), on the other hand, focuses on the distribution and reception of media, by defining them as the “material resources of the channel” and presenting, as examples, platforms such as the radio and websites (p. 20). Elleström (2010) offers a very sophisticated view of media and rejects the idea of modes being “[e]ntities such as ‘text’, ‘music’, ‘gesture’ or ‘image’” (p. 16). He sees media as the starting point and maintains that, in order to fully appreciate and analyse how media work, one needs to consider four different modalities that are all necessary conditions for any medium to exist: a material modality, a sensorial modality, a spatiotemporal modality and a semiotic modality. These “are to be found on a scale ranging from the tangible to the perceptual and the conceptual” (Elleström, 2010, p. 15) and, although not chronologically or hierarchically ordered, they can be approached in that order as each modality depends on the existence of the previous one to be accessed (ibid, p. 17). Materiality is therefore a defining feature of media and the latter, following Elleström (2010), can be defined as the material channels, be these animate or inanimate, through which communicative events are produced, distributed and received.

Of particular interest to our discussion is the semiotic modality. This modality attends to meaning, with the latter to “be understood as the product of a perceiving and conceiving subject situated in social circumstances” (Elleström, 2010, p. 21). The semiotic modality is what allows people to interpret signs through two different ways of thinking: an abstract one directed by propositional representations “created by conventional, symbolic sign functions,” that is signs that have no resemblance or association with the object they refer to (e.g., words or a red light to imply “stop”);4 a direct one directed by pictorial representations “created by indexical and iconic sign functions” (ibid, p. 22), that is signs that have an association with the object they refer to (an index, e.g., smoke signalling a fire) or that refers directly to the object (an icon, e.g., a photo or an emoji). Using terminology from Peirce’s semiotics, Elleström (2010, p. 22) therefore suggests “that convention (symbolic signs), resemblance (iconic signs) and contiguity (indexical signs) should be seen as the three main modes of the semiotic modality”.

Elleström’s discussion is centred around the focal concept of medium and the term modalities can create confusion in, for example, a social semiotic approach to multimodality where modality is used to refer to the degree of epistemic value of the signs (e.g., Van Leeuwen, 1999, p. 170).5 Despite the terminological confusion, I believe that his unpacking of what makes media what they are is compelling, as it touches on all the elements (materiality, senses, cognition and semiosis) that need to be considered in a multimodal approach to communication, particularly if the interaction of an audience with the media is also analysed. There are, however, some issues with Elleström’s all-encompassing definition of media, particularly when it comes to understanding the relationship between media and modes. Bateman (2017, p. 168) maintains that the primary role of media is to “provide the immediate context in which semiotic modes can be used.” He therefore argues that the relationship between media and modes is not one of interdependence and highlights how.

On the one hand, semiotic modes are always more ‘local’ organisations that take responsibility for the deployment of specific material regularities. They are definitionally independent of media. On the other hand, media are broader ‘second-order’ phenomena constituted by socioculturally specific bundlings of semiotic modes and, as a consequence, may not be directly perceptible in their own right (p. 172).

With reference to the role of semiotic resources as defined in section 3, a similar line of thought can be followed, first and foremost because semiotic resources are now defined as a constitutive component of semiotic modes. The representational force afforded by semiotic resources in the process of deploying modes in situated communicative contexts is also fully realised only when ascribed to a specific medium and, as per Bateman (2016), to a specific genre. As we have argued before, it is often the combination of modes with their individual metafunctional possibilities and limitations that, through the higher-order levels of media and genre, allows a communicative event to be able to realise all three metafunctions and therefore acquire full communicative effectiveness.

Now the hierarchical relationship between modes (which include semiotic resources) and media has been established we can turn to discuss in more detail the role of materiality in the analysis of multimodal texts and their reception.

5 Materiality

Materiality has played a key role in multimodal research since the very first discussions of the theoretical and analytical preoccupations of this line of scientific enquiry. Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) highlight this very clearly:

A semiotics which is intended to be adequate for the description of the multimodal world will need to be conscious of forms of meaning-making which are founded as much on the physiology of humans as bodily beings, and on the meaning potentials of the materials drawn into culturally produced semiosis, as on humans as social actors. All aspects of materiality and all the modes deployed in a multimodal object/phenomenon/text contribute to meaning (p. 28).

However, before looking at how materiality affects semiosis, it is worth discussing why it is important for the material to be part of multimodal research. Bateman (2021a, p. 36) highlights the role materiality can play in providing “a robust empirical methodology for multimodality studies.” As he argues,

Focusing attention on materiality naturally brings into close relief those very ‘objects of analysis’ (construed quite literally) that are of central concern for multimodality. It will consequently be argued that a better understanding of materiality contributes directly to methodology in that knowing more about materiality also supports more robust and well designed empirical studies (p. 36).

Bateman et al. (2017, p. 230) pose as the first step of empirical investigation the identification of the material properties of the communicative event under analysis. The four basic dimensions they discuss are temporality, space, role, and transience. Temporality refers to whether the traces are “dynamic” (e.g., a film) or “static” (e.g., a page in a book); space refers to whether they are two or three-dimensional; role refers to the relationship between an interpreter and the communicative event as being either ‘observational’ (i.e., as placed outside of the event) or “participatory” (i.e., as place inside of the event); transience refers to the traces being either “permanent” (e.g., ink on paper) or “fleeting” (e.g., gestures) (Bateman, 2021a, p. 40). Multimodal texts will not only present all these four dimensions at once, but also potentially have co-occurring bundlings of signifying material that belong to different dimensions; this will require the analyst to “slice” the communicative event in smaller analytical units, or “sub-slices”, for more fine-grained and precise analyses (Bateman, 2021a, pp. 42–43).

As Bateman (2021a, p. 43) also notes, however, the initial analysis of the four dimensions by itself cannot adequately deconstruct complex multimodal artefacts, since “it is not the case that situations can be positioned with absolute freedom along each of the dimensions given.” To this end (p. 43ff.), he proposes a more nuanced categorisation of the dimensions, which sees, for example, the role dimension being problematised by the fact that different interpreters may engage with the same materialities in different ways through their embodied perception, thus blurring the dichotomy observer/participant. Similarly, the dimension of transience is also broken down further by looking at aspects such as manner of (dis)appearance, degree of granularity and time depth. Bateman (2021a, p. 47, my emphasis), therefore, points out that “th[is] characterization of materiality […] is not that of physics but rather rests on active perceivers’ embodied engagement with materials for semiotic purposes.” This semiotically-oriented view of materiality expands empirical avenues for researching the reception of multimodal artefacts, since research in this area has highlighted how engagement differs depending on a number of individual factors, such as “the task or goal of the [text] examination, previous knowledge and expertise, expectations, emotions and attitudes. Apart from viewer characteristics, even the context in which [texts] are displayed, perceived and interpreted plays a role” (Holsanova, 2014, p. 340). This is an aspect I will discuss further in the next section.

Once the relevant slices and materialities are identified, one can proceed to analyse what different modes, and the canvases and media that support them, contribute to signification, and how they do so. At this level of analysis, one of the aspects often discussed in approaches to multimodal research is the idea of the affordances of materials. Affordances can be defined in terms of what the environment that surrounds us, whether of a natural or artificial type, allows us to do. As Gibson (2015, p. 120) puts it, “[t]he different substances of the environment have different affordances for nutrition and for manufacture. The different objects of the environment have different affordances for manipulation.” Amongst the objects that allow for manipulation, multimodal scholars have routinely included the modes and media of communication. Moreover, Gibson (2015, p. 121) argues that these affordances are neither subjective nor objective, or rather, that they can be both depending on the context and the observer/user; this is a property that can also be found in the Hallidayan concept of meaning potential, which has prompted some to see affordances as synonym of semiotic resources (Van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 5). The issue of what the affordances of modes and media are has certainly been the one discussed the most in the literature, either in terms of “abstract distinctions and commitments” (Bateman and Schmidt, 2012, p. 94) or in terms of their ideological load (Machin, 2013, pp. 349–350). However, Bezemer (2023, p. 6, emphasis in original) notes how Kress defines affordances “in terms of (i) materiality or inherent physical properties; and (ii) social and cultural conventions of using these properties for communication.” The second point hints to Gibson’s idea of affordances being both subjective and objective, but defines more clearly where the subjectivity lies, that is in the socio-cultural conventions surrounding communicative events and the modes deployed therein, which are inevitably contingent to historic specificities. This dual nature of affordances, therefore, points to different lines of enquiry that need to be taken into consideration when approaching multimodal communication.

On the one hand, we can focus on how the materiality of the signs and sign systems affect their deployment in communication. This can include looking at what semiotic resources can be accessed by specific semiotic codes and what material form they will take once deployed through specific media and genres as part of their mode contribution. Moreover, we can also look at how the materiality of the signs and their paradigmatic and syntagmatic structure bear representational force. On the other hand, we can focus on how socio-cultural conventions, as well as technological advancement, shape and alter the range of material configurations that can be deployed through specific modes, media and genres. Both lines of enquiry are pursued by Bateman (2014) when analysing the historical development of the genre of “bird field guides”. Along the first line of enquiry, he considered “what semiotic modes are being mobilised in the service of what kinds of rhetorical strategies” (p. 252) in various reiterations of the same genre at different points in time and through both non-digital and digital media.6 Along the second line of enquiry, he highlighted that, although the construction and deployment of rhetorical strategies relied on different modes as the media deployed changed over time unlocking new and different affordances to the modes, the rhetorical strategies themselves, as a communicative characteristic of the genre, remained unvaried.

It is worth noting at this stage, that both lines of empirical enquiry, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section, can be approached both from a formal, structuralist perspective and, as in this case of approaches within social semiotics and multimodal critical discourse analysis, from social and critical perspectives.

6 Implications for empirical research in multimodality

This section will look at the implications for empirical research in multimodality based on the discussion so far and will concentrate on the new conceptualisation of semiotic resources as carriers of metafunctional constructs as well as on the role of materiality as discussed in the previous section. Moreover, the discussion will cover both multimodal text analysis and multimodal text reception as well as pointing out aspects that can be of use to social and critical approaches to multimodal research.

The focus on metafunctions as a legitimate empirical avenue of research has recently been acknowledged by Bateman (2021b, p. 3), who points out that “[m]etafunctional accounts offer interpreters and producers resources for discussing and reflecting on just how information is structured and expressed and the social positions that appear to be being taken up in and by messages.” However, Bateman (2021b) also adds that:

Currently, descriptions such as those employing metafunctional distinctions […] presuppose particular kinds of meanings for forms of expression a priori – that is, many current frameworks in use conflate the identification of technical features, i.e., identifiable material forms, and those features’ meanings […] Reliably applicable categories have, however, not yet been established by corresponding empirical investigations of the semiotic resources considered. Establishing and developing a more reliable foundation for such descriptions therefore needs to be made a priority. (p. 4).

The categorisation of semiotic resources as proposed in this paper, if investigated both at the stages of multimodal text production and reception, can serve as a starting point to build those ‘reliably applicable categories’ Bateman calls for. The materiality of modes, media and sensory channels7 can provide research hypotheses based on their affordances and relation to semiotic resources. Hypotheses can then be tested empirically both from the perspective of text production and from the perspective of text reception.

As a starting point, three discrete, but related research focuses can be identified (cf. Bateman, 2021b, pp. 3–4): (i) investigating which semiotic resources and metafunctions individual modes can actualise (cf. also Bezemer, 2023, p. 11ff.); (ii) investigating the relationship between different modes actualising the same semiotic resources and metafunctions; (iii) investigating the contribution of individual modes to perform the three metafunctions of a communicative event. These research focuses can be pursued both qualitatively and quantitatively as neither paradigm is intrinsically better than the other in multimodal research, provide quality criteria are in place (Pflaeging et al., 2021, p. 6ff.). Moreover, these research focuses can be pursued from the perspective of both text analysis and text reception.

6.1 Investigating which semiotic resources and metafunctions individual modes can actualise

The first focus is on the material affordances of individual modes and the extent to which they can (and indeed do) actualise certain semiotic resources in a specific communicative context. The analysis would consider both the materiality of the modes themselves and the materiality of the media through which they are deployed. The aim here is to establish the signifying potentials of modes and the material aspects involved in the process of signification within specific communicative practices. Hypotheses can be generated from existing theory and qualitative studies and then tested on specific corpora, be these medium-based, genre-based, or a combination of both. Discrete sets of semiotic resources, discursive, pragmatic, stylistic and textual can be investigated so that reliable categories can be confirmed or rejected.

Interestingly, comparisons can be made between the same modes as deployed across different media and genres. This could shed some light on whether certain resources can be activated in all contexts; whether they are activated in a similar fashion or in different ways and, if the latter, what factors (both in terms of individual choices of the text producers and as imposed from the context of deployment of the modes) influence the syntagmatic and paradigmatic organisation of the mode as well as the resulting discourse semantics; whether their deployment has changed over time, as in Bateman’s (2014) study of rhetorical strategies in the ‘bird filed guides’ genre, and again, what factors might have contributed to such change.

From the point of view of reception studies, hypotheses regarding individual modes and metafunctional realisations that are generated through text analysis studies can be tested for identification, comprehension and interpretation. Alternatively, reception studies can be the starting point (perhaps through more qualitative approaches) for such categorisations, which can then be empirically tested on corpora of texts or on larger cohorts of participants in order to highlight trends and patterns.

These perspectives can inform both formal, structural approaches to multimodal research and critical ones. Researching the contextual factors that lead to certain realisations of metafunctions, or indeed to certain modes not performing a metafunction at their disposal in specific contexts, can point at aspects of power dynamics between institutions and practitioners, between participants in the communicative event, and so on.

6.2 Investigating the relationship between different modes actualising the same semiotic resources and metafunctions

The second focus may result from the analysis of the first as it may turn out that more than one mode is contributing to performing the same metafunctional construct. This may be by contributing to actualise the same semiotic resource, or it may be by contributing to perform the same metafunction by actualising complementary semiotic resources. The aim here is therefore to investigate the relationship between different modes when co-deployed in a multimodal artefact. Again, discrete categorisations of the semiotic resources along the lines suggested in this paper allows one to focus on specific resources and material realisations, not only by looking at communicative events as a whole, but also at slices and sub-slices of materials and related canvases as suggested by Bateman (2021a, pp. 42–43).

Similarly to what discussed with the first focus, hypotheses can be generated from existing theory and qualitative studies, and tested empirically and quantitatively across corpora and comparable datasets. This approach would enable investigations into patterns of co-dependency between modes as they realise specific semiotic resources and metafunctions; analysis of variances of the co-dependencies identified across media and genres; factors affecting variance, driven by both bottom-up and top-down considerations; medium- and genre-specific historical developments of semiotic resources and metafunctions over time.

Receptions studies here can add valuable information at three different levels: studies integrating psychophysiological measures (e.g., using eye-tracking technology) can offer insights on matters such as attention, focus and ‘reading’ paths, in order to investigate, for example, whether certain modes are mostly relied upon in the recognition of certain semiotic resources or metafunctions. Experimental studies manipulating the multimodal output or relying on qualitative instruments such as think-aloud protocols and retrospective interviews can offer insights on recognition and comprehension of semiotic resources and metafunctions when these are deployed by modes individually or co-deployed: these can incorporate the exclusion of expected metafunctional realisations and/or the inclusion of unexpected ones. Finally, qualitative studies can offer insights on the interpretation of certain semiotic resources and metafunctions as well as an assessment of their effectiveness vis-à-vis their intended use and function.

From a critical perspective, this approach can shed light on matters of persuasion, manipulation, legitimation and argumentation, or any other pragmatic goals, by investigating how certain modes and related semiotic resources achieve their goals. Again, the critical variant for this research focus can rely both on text analysis and text reception studies.

6.3 Investigating the contribution of individual modes to perform the three metafunctions of a communicative event

The third focus is a step up from the second one, with the aim to provide a more holistic description of which metafunctions and semiotic resources are present in a specific communicative event. Assuming a communicative event necessarily relies on engaging the participants at all three metafunctional levels, i.e., ideational, interpersonal and textual, the aim of this line of enquiry is to identify which modes perform a specific metafunction, whilst taking into consideration the other variables already mentioned, i.e., media and genres, and their situational specificities and historic development. Once again, the classification of semiotic resources proposed in this paper would facilitate focussed investigations that can span across modes and, within communicative events, across slices and sub-slices of materials.

Most of what highlighted for the second focus in terms of formulating hypotheses applies to this third line of enquiry too. However, a further analytical focus with this third approach is the co-dependency and individual contributions of sub-slices and slices of semiotically-charged materials to the overall performance of semiotic resources and metafunctions, thus taking the level of analysis from within individual canvases to across multiple co-occurring canvases. As with the previous levels of analysis, reception studies can be integrated here, in which slices and sub-slices of material can be manipulated for experimental purposes, and more qualitatively driven studies can explore matters of comprehension, interpretation and effectiveness of different (sub-)slices configurations.

More generally, and valid for all the three levels of analysis discussed, the advantage of a clearly distinct and defined concept of semiotic resources and a more nuanced understanding of how materiality affects signification at different stages of text production, distribution and reception, allows one to zoom in on specific aspects of semiosis and to be able to approach the object of research both qualitatively and quantitatively.

7 Conclusion

The paper has engaged with a crucial issue in multimodal research, that is a lingering confusion (or disagreement) around some key concepts needed to research and write about multimodality. The definition and composition of mode as proposed by Bateman (2011, 2016) and Bateman and Schmidt (2012) has been used as the starting point to provide a clearer distinction between the concepts of semiotic mode and semiotic resources. It has been argued that there is an ontological difference between these two aspects of semiosis, with the former being a combination of material and abstract elements and the latter having no materiality of their own, but the ability to manifest themselves through different materialities. Indeed, the metafunctional properties attributed to semiotic resources are often deployed and articulated not only through different materialities but also through the simultaneous co-occurrence of different modes and through accessing different sensory channels, which is another ontological difference between semiotic modes and semiotic resources. Semiotic resources have therefore been defined in this paper as abstract, potential metafunctional constructs that can be realised through different materialities and/or semiotic codes, and have been organised in four areas: discursive, pragmatic, stylistic and textual.

Once established the nature and ontological status of semiotic resources, the issue arose concerning their relationship with semiotic modes. The paper has argued that semiotic resources should be part of the constitutive elements of a mode and be placed at an intermediate stratum between the paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of organisation (the second stratum in Bateman’s model) and discourse semantics (the third stratum in Bateman’s model), thus creating a four-stratal definition of a semiotic mode. This new stratum of semiotic resources is necessary to explain how, in the process of deploying a mode (i.e., in the process of semiosis), the material substrate is organised in specific paradigmatic and syntagmatic forms to allow certain (and not other possible) interpretations at the level of discourse semantics. It has been also argued that the choice of semiotic resources to be adopted can be guided both by bottom-up (i.e., text producer-driven) and top-down (i.e., context-driven) factors.

Moreover, since “we do not find ‘free-floating’ instances of semiotic modes” (Bateman, 2017, p. 168) the concept of media has also been discussed and a relationship of independence between media and modes established (Bateman, 2017, p. 172). With all the main concepts in place, and since materiality has been playing an increasingly important role in multimodal research to the point that focussing on it is necessary to provide “a robust empirical methodology for multimodality studies” (Bateman, 2021a, p. 36), the role of materiality in multimodal research has been discussed. Here two lines of enquiry have been identified as being ‘unlocked’ my a material approach to multimodality: the first concerns how the materiality of the signs and sign systems affects their deployment in communication; the second concerns how socio-cultural conventions, as well as technological advancement, shape and alter the range of material configurations that can be deployed through specific modes, media and genres. Finally, based on the new conceptualisation of semiotic modes and semiotic resources, and on the discussion around the role of materiality, implications have been outlined for empirical multimodal research and pointers offered as for potential research endeavours that can focus both on text production and text reception at three different levels of analysis (cf. Bateman, 2021b, pp. 3–4): (i) investigating which semiotic resources and metafunctions individual modes can actualise; (ii) investigating the relationship between different modes actualising the same semiotic resources and metafunctions; (iii) investigating the contribution of individual modes to perform the three metafunctions of a communicative event.

The work of John Bateman has paved the way towards a more systematic and empirically oriented way of doing multimodal research, especially within the social semiotics and SFL orientations. This paper is an attempt to build on this body of work and continue to strive for theoretical and methodological clarity in a discipline that is still in the process of establishing its own grounds and agreeing on key concepts, despite the incredible body of research carried out over the past three decades.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research funding at Canterbury Christ Church University covered the APCs for this paper.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Alex Cockain and John-Paul Riordan for their comments on the first draft of the paper. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their comments, which have considerably improved the clarity and focus of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^From this point onwards, following Bateman’s definition, a “semiotic code” is meant to refer to a context-potential sign system, whereas a “semiotic mode” is meant to refer to a context-actual sign system.

2. ^Text types, following the German school of text linguistics applied to translation (Nord, 1991, p. 18), refer to narration, report, description, exposition and argumentation.

3. ^I am using communicative acts in place of the most commonly used speech acts to extend this pragmatic concept to non-linguistic modes (see also Bucher’s (2017, p. 110 ff.) definition of multimodality as communicative action).

4. ^Although some words can be described as “iconic symbols” (e.g., onomatopoeic words) and “indexical symbols” (e.g., deictic words) (Chandler, 2017, p. 56).

5. ^More recently, Oja (2023) provides yet another understanding of modalities, using the term to refer to sensory modalities and arguing for a clear differentiation between semiotic modes and sensory modalities.

6. ^Bateman (2021b) further debunks the idea that digital media are to be treated differently than traditional media, and provides a taxonomy of configurations that can be applied to all communicative events.

7. ^Due to the limitation in space, I have not been able to provide an adequate treatment of sensory channels in this paper. However, there is already some work in this direction (e.g., Oja, 2023) and I am myself working on a contribution to this discussion.

References

Bateman, J. A. (2011). “The decomposability of semiotic modes” in Multimodal Studies: Multiple Approaches and Domains. eds. K. L. O’Halloran and B. A. Smith (London: Routledge), 17–38.

Bateman, J. A. (2014). “Genre in the age of multimodality: some conceptual refinements for practical analysis” in Evolution in genre: Emergence, variation, multimodality. eds. P. Evangelisti-Allori, V. K. Bhatia, and J. A. Bateman (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang), 237–269.

Bateman, J. A. (2016). “Methodological and theoretical issues in multimodality” in Handbuch Sprache im Multimodalen Kontext. eds. N. M. Klug and H. Stöckl (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter), 36–74.

Bateman, J. A. (2017). Triangulating transmediality: a multimodal semiotic framework relating media, modes and genres. Discourse Context Media 20, 160–174. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2017.06.009

Bateman, J. A. (2021a). “Dimensions of materiality” in Empirical multimodality research: methods, evaluations, implications. eds. J. Pflaeging, J. Wildfeuer, and J. A. Bateman (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter), 35–63.

Bateman, J. A. (2021b). What are digital media? Discourse Context Media 41:100502. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100502

Bateman, J. A., and Schmidt, K. H. (2012) Multimodal film analysis: How films mean. New York: Routledge.

Bateman, J. A., and Wildfeuer, J. (2014). A multimodal discourse theory of visual narrative. J. Pragmat. 74, 180–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.10.001

Bateman, J. A., Wildfeuer, J., and Hiippala, T. (2017) Multimodality: Foundations, research and analysis: A problem-oriented introduction. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Bezemer, J. (2023) What modes can and cannot do: Affordance in Gunther Kress’s theory of sign making. Text & Talk. doi: 10.1515/text-2022-0055

Bucher, H. J. (2017). “Understanding multimodal meaning making: theories of multimodality in the light of reception studies” in New studies in multimodality: conceptual and methodological elaborations. eds. O. Seizov and J. Wildfeuer (London & New York: Bloomsbury), 91–123.

Elleström, L. (2010) The modalities of media: a model for understanding intermedial relations. In Media Borders, multimodality and Intermediality, ed. L. Elleström (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 11–50.

Forceville, C. (2009). “Non-verbal and multimodal metaphor in a cognitivist framework: agendas for research” in Multimodal metaphor. eds. C. Forceville and E. Urios-Aparisi (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter), 19–35.

Gibson, J. J. (2015) The ecological approach to visual perception. New York & London: Psychology Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978) Language as a social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

Hiippala, T., and Bateman, J. A. (2021). Semiotically-grounded distant view of diagrams: insights from two multimodal corpora. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 37, 405–425. doi: 10.1093/llc/fqab063

Hiippala, T., and Bateman, J. A. (2022). “Introducing the diagrammatic semiotic mode” in Diagrammatic representation and inference: 13th international conference (diagrams 2022), Vol. 13462 of lecture notes in computer science. eds. V. Giardino, S. Linker, R. Burns, F. Bellucci, J.-M. Boucheix, and P. Viana (Cham: Springer), 3–19.

Holsanova, J. (2014). “In the eye of the beholder: visual communication from a recipient perspective” in Visual Communication. ed. D. Machin (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 331–356.

Kress, G. (2010) Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (1996) Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Psychology Press.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2001) Multimodal discourse: the modes and Media of Contemporary Communication, London: Arnold.

Machin, D. (2013). What is multimodal critical discourse studies? Crit. Discourse Stud. 10, 347–355. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2013.813770

Machin, D. (2016). The need for a social and affordance-driven multimodal critical discourse studies. Discourse Soc. 27, 322–334. doi: 10.1177/0957926516630903

O’Halloran, K. (2005) Mathematical discourse: Language, symbolism and visual images. London: Continuum.

Oja, M. (2023). Semiotic mode and sensory modality in multimodal semiotics: recognizing difference and building complementarity between the terms. Sign Syst. Stud. 51, 604–637. doi: 10.12697/SSS.2023.51.3-4.05

Page, R. (2009). “Introduction” in New perspectives on narrative and multimodality. ed. R. Page (London: Routledge), 1–13.

Pflaeging, J., Wildfeuer, J., and Bateman, J. A. (2021). “Introduction” in Empirical multimodality research: Methods, evaluations, implications. eds. J. Pflaeging, J. Wildfeuer, and J. A. Bateman (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter), 3–32.

Stöckl, H. (2014). “Semiotic paradigms and multimodality” in The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. ed. C. Jewitt. 2nd edn ed (London: Routledge), 274–286.

Keywords: semiotic modes, semiotic resources, media, materiality, empirical multimodality research

Citation: Castaldi J (2024) Refining concepts for empirical multimodal research: defining semiotic modes and semiotic resources. Front. Commun. 9:1336325. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1336325

Edited by:

Janina Wildfeuer, University of Groningen, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Tuomo Hiippala, University of Helsinki, FinlandHartmut Stöckl, University of Salzburg, Austria

Copyright © 2024 Castaldi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jacopo Castaldi, jacopo.castaldi@canterbury.ac.uk

Jacopo Castaldi

Jacopo Castaldi