Predicting the level of social media use among journalists: machine learning analysis

- 1Public Relations Department, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- 2Mathematics & Computer Science, Southern Arkansas University, Magnolia, AR, United States

- 3Communication & Media College, Al Ain University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 4Editor of Centre for India West Asia Dialogue, New Delhi, India

- 5Public Relations Department, University of Kalba, Kalba, United Arab Emirates

Within the long-drawn of COVID-19, the impact of social media is important for the public and journalists to re-engage with each other due to the relentless churning out of information. This paper investigates Arab journalists' use of social media during COVID-19 through Machine Learning (ML) models to predict future use and the main factor(s) deriving the respondents to such use. It aims to analyze the relationship between Arab journalists' online activity and their use of social media platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic. To assess the frequency of social media usage among Arab journalists and its correlation with their primary tasks and accomplishments. To test the accuracy of these models, we collected 1,443 Arab journalists via an online survey in 2020 using a random sampling approach. Key variables like online active journalists, Facebook group usage, and frequency of usage were studied. The received responses were subjected to ML analysis such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree, and Ensemble Bagged Tree (EBT). The EBT predicted that Arab journalists would continue to rely on social media to various degrees as a viable source to fulfill their main tasks and accomplishments.

Introduction

Social media is one of the most vital sources of news and information for many journalists including Arab journalists (Mansour, 2018; Fahmy et al., 2022), because of its involvement in connecting users, sharing common interests and etc. (Alhuntushi and Lugo-Ocando, 2020; Busty et al., 2020). For Arab journalists, social media has helped in creating news stories, connecting journalists, interactions, and news presentations. These social media platforms are perceived among Arab journalists as drivers of social empowerment and public opinion, thereby endowing them with several opportunities and challenges, especially as the state remains a powerful player in discourse construction in public spaces and memories. The need for instantaneous news updates post Arab Uprisings gave rise to amateurish yet alternative forms of “truth-telling” in the heavily authoritarian media regimes.

Studies (Mansour, 2018; Fahmy et al., 2022) indicated that social media platforms are commonly used by Egyptian journalists, especially in unforeseen times such as COVID-19 (Amici, 2020; Jamil and Appiah-Adjei, 2020). Consequently, this transformation has changed how journalists deal with news and information and depend on social media platforms. The primary social media used were microblogging sections, forums and comments, social networking sites, media sharing and bookmarking sites. At the same time, the lack of authenticity and credibility of news sources are major challenges (Mansour, 2018). According to the Arab Barometer Report (2021), information and news disseminated through social media in Arab countries during the pandemic reached faster than traditional media. The profiles of doctors suggesting ways to prevent COVID-19 infection and direct communication with the government's social media platforms have also increased reliance on social media usage (Elkalliny, 2021).

Technologically, most Arab media organizations have adopted social media platforms (Lewis and Molyneux, 2018; Geçer et al., 2020) to improve communication and interaction with users (Richter and Kozman, 2021; Fahmy et al., 2022). This has enabled most Arab journalists to increase their capabilities in seeking and gathering information from social media; however, little is known about this. Jallow (2015) defines social media as the merging of global journalism. This definition includes its use as a new power to enhance the global connectivity. Boyd and Ellison (2007) have defined social media as web-based services which allow individuals to construct a public profile within the specified norms of the platform, form online connections with other users they follow and view other connections made by their contacts within the system (Boyd and Ellison, 2007).

Such platforms have steadily emerged into many Arab journalistic practices, news organizations (e.g., Al-Jazeera, Al-Arabiya, and Arab News) that have required journalists to familiarize themselves with these new platforms (Cottrill, 2015; Mansour, 2018) in their workforces. Arab journalists, like others, are expected to adopt technologies and use them to build relationships with their followers (Fatima, 2020). Cottrill (2015) found that 75 percent of social media-savvy journalists daily access and log into social media for news and information, enhancing why journalists choose such platforms in their routine works. As Arab journalists do not fall in the Western typologies of identification of journalists, Weaver and Willnat (2012) have identified them as “Change Agents” and “Guardians” who are now trying to contextualize their socio-empirical realities within the transformations caused by social media. They are now re-initiating and rediscovering their passions of pan-Arab identity and helping to reshape Arab identity and flow of news from the Global South (Kirat, 2020).

Research elsewhere has looked at how journalists have used new digital platforms that have brought ease, speed and accessibility to all kinds of information, and communication (Geçer et al., 2020), and to maximize their usage in journalism practices by professionals and journalists (Bruns, 2018; Lewis and Molyneux, 2018; Khamis and El-Ibiary, 2022) and engagement with others. However, there is little direct attention to how and why Arab journalists rely on new media as a news source and for the types of stories they cover (Alhuntushi and Lugo-Ocando, 2020; Fatima, 2020) during COVID-19 (Alhuntushi and Lugo-Ocando, 2020; Litvinenko et al., 2022) and their future adoption. Simultaneously, the news organizations have also adopted prevention-focused methodologies to check the social media engagement of their journalists to mitigate any new forms of risks emerging in the social media age (Lee, 2016).

Arab journalists' attitudes toward social media during COVID-19 are still relatively underexplored. The lack of empirical investigation within the Arab world, especially taking into consideration how Arab journalists dealt with and reported the COVID-19 pandemic through social media's technological penetration has been an acute research gap aimed at filling this gap. The study, therefore, aimed to analyze the relationship between Arab journalists' online activity and their use of social media platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic. To assess the frequency of social media usage among Arab journalists and its correlation with their primary tasks and accomplishments. To investigate the impact of social media groups usage on Arab journalists' engagement with information dissemination and consumption. By integrating the impact of machine learning within the socio-cultural context of the Arab world, the paper also perceives the outcome to help other futuristic research in this domain. This research also aims to predict the future adoption of social media by Arab journalists for various other pandemic and post-pandemic-related research.

Literature review

Social media dependency and Arab journalism

Media have been the center of information and knowledge for almost a century for both the public and journalists to engage with each other in dynamic ways (McPhail and Phipps, 2020). For example, the public should be aware of issues and journalists should do their jobs. The type of dependency here is exchangeable, where the media has been able to provide the public with information they need (McQuail, 2010) and journalists rely on the public to get their news stories, especially in the era of social media and the online sphere. Media dependency, especially in the context of social media became an emerging trend during the COVID-19 pandemic when the social media pages of doctors, COVID warriors, public authorities and local institutions were followed more keenly by users and their response aided journalists to form their views (Alam et al., 2020; Osmann et al., 2021). The paper understands that the media dependency theory had been articulated with reference to the audience and therefore, it tries to contextualize it within the framework of how journalists have grown dependent on social media to further add to the theory. With the instability factor caused by COVID-19, it is necessary to further broaden the theoretical framework of Media Dependency Theory to update it with the transforming times. Therefore, among the various theories linked to the role of media in disseminating news and information, dependency theory has a particular stance how, e.g., journalists depend on social media platforms and how they cover news stories. Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) illustrated media dependency as “the dependency of audiences [journalists] on media information sources [social media] that leads to modifications in both personal and social processes” (p. 5). In doing so, media dependency increases in “the presence of structural instability” or ambiguity (e.g., COVID-19) in society as Melki and Kozman (2021) cited.

Since the early 2000s, the way Arab journalists have relied on social media can be highlighted as follows: First, during the early 2000s, social media (as a new phenomenon) did not have a great influence on Arab journalism for several reasons such as many of these platforms started a social rather than professional tool (al-Az'azi, 2015; Mounir, 2017); many Arab journalists did not have the ability to use social media in their work (Ziani et al., 2017); lack the necessary knowledge and IT skills to adopt such platforms in journalism; social media's roles and influence in society have not been acknowledged by media organizations (Mounir, 2017); and most Arab governments monitored and controlled the flow of information content meaning that Arab journalists had to live in such environment (Richter and Kozman, 2021). However, such period can be seen as the foundation for the spark of an awakening of the public to know what is going on around, and where Arab journalists started to use social media and attempted to understand its impact on society and build their relationship with the public (Al-Najjar, 2011; Elareshi et al., 2020). Generational change continued to be another reason for media dependency, as newsrooms in the Arab world also started diversifying in their realms, adding more inclusion-based approaches and how their online behavior also carried professional responsibility to public discourses (Newman, 2022).

During the same period, Arab media organizations (especially Pan-Arab news e.g., Al-Jazeera) became aware of the importance such platforms in journalism alongside broadcasting satellite services (El Gody, 2021). This led Arab journalists to increasingly develop in collecting online news from multiple sources and employing that information in their online news story production, as well as platforms to create, share and produce news stories and gain recognition from their followers (Khamis and Vaughn, 2011; Lewis and Al Nashmi, 2019) and finding avenues to reach a wide audience (Broersma and Eldridge, 2019; Fahmy and Abdul Majeed, 2020). To Broersma and Eldridge (2019), social media is perceived as something normalized and regularly fitted into the functions of journalism, and used to market journalists' stories (Bruns, 2018). This is especially true for well-established news outlets such as BBC Arabic, Al-Arabiya and Al-Jazeera media services.

Second, during and after the 2011 Arab uprisings, it became clear that social media's role in the period has been at the heart of much scholarly research (Tank and Ari-Matti, 2012; Sultan, 2013). Many Arab journalists turned to social media and connected with the public and political movement, and this was seen as the real point of dependence on social media that allowed the discovery of online possibilities of communication with others, and more importantly to overcome the Arab government media and their alliance's restrictions by both the journalists and citizens (Wolfsfeld et al., 2013; Al-Jenaibi, 2020; Badr, 2021). This allows them to be close to their users and share different content more easily and freely with them. Social media roles in the street mobilization of the 2011 event cannot be ignored (Ghannam, 2012; Rane and Salem, 2012) as they contribute to the transmission of various information and images by Arab protection, activities, and journalists inside and outside the Arab world (O'Rourke, 2011; Lynch, 2015).

Given its low cost and influence, many Arab print media have started to switch to online formats and dropped their print editions such as the Saudi Al-Majalla newspaper, the UAE sports magazine Super, the Gulf News, and Lebanon's An-Nahar daily. This meant that Arab journalists were more reliant on social and online media content and were free from traditional journalism and how traditional media lacks engagement with the public (Badr, 2021). However, this does not mean that most Arab journalists were ready to fully adopt such platforms in their work as many obstacles still occurred such as lack of knowledge, training and skill in using social media professionally (Alawneh and Muhammed, 2016; Mansour, 2018) as well as lack of trust in social media information (al-Az'azi, 2015; Mounir, 2017).

Third, Arab journalists and their dependence on such platforms for news and information and in the production of journalistic topics during the COVID-19. Unsurprisingly, several Arab journalists have used social media as one of the main sources of their news stories (Badr, 2021), as gathering news stories was very difficult due to travel restrictions applied to most Arab journalists. They were required to work from home for the first time. For example, Faisal Abbas, the editor-in-chief of Arab News in a conference Zoom talking to Richard Quest organized by the American University of Sharjah (UAE) addressed the journalists' roles in fighting the pandemic in newsrooms including the struggles and the decision-making process where most his journalist team had to work, cover and share news stories from home (AlSadr, 2021). Social media and the Internet consequently became the main windows for them to collect information and data, and disseminate it to the public, which led to integration into the dynamics of journalism as Bossio (2017) indicates. COVID-19 intensified collaborative online formats of exchanging advice and sources in many Arab countries (Badr, 2021).

Arab journalists and the COVID-19 pandemic

After COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in early March 2020, people in the Arab world, like elsewhere, looked for protection, guidance, and information from their governments, mainstream, and alternative media (e.g., social media) (Fatima, 2020; El-Elimat et al., 2021). The latter has been an essential source during the crisis for both people and journalists (AlSadr, 2021). Since most Arab people and journalists now use social media on daily basis, it has become an effective online space to share experiences and information about the virus. At the same time, the emergence of global infodemic due to rampant political and medical misinformation created necessity to cross-check data, as panic, conspiracy theories and xenophobia started rising at a global level. Social media were primarily used for searches related to medical advice, virus transmission, vaccines and medical treatments, conspiracies, public authorities, lockdown measures, public reactions and community spread. The reliance on social media by Arab journalists during the COVID-19 pandemic holds significant importance for several reasons such as timely dissemination of information and news. Social media platforms enable Arab journalists to disseminate information quickly and efficiently to a wide audience, audience engagement, and trust-building. Social media facilitates direct engagement between journalists and their audience, fostering transparency, trust, and credibility.

The first Arab country to officially report the presence of COVID-19 was the UAE with five cases in January 2020, followed by Egypt (Alandijany et al., 2020; Alwahaibi et al., 2020). In May 2020, 290,428 cases were reported in all Arab countries, resulting in 3,696 deaths and around 157,886 cases were cured. Such figures placed Arab countries fourth after the US, Brazil, and Russia in terms of COVID-19 confirmed cases (Alwahaibi et al., 2020).

Arab governments took several strategies and measures to reduce the spread of the virus, but these strategies varied from one country to another, which subsequently affected the way information and restrictions were applied and understood (Alandijany et al., 2020; AlSadr, 2021), especially through social media. For example, surprisingly, countries such as Libya, Algeria, Lebanon, and Iraq, which severely suffer from unstable politics, health systems, and socioeconomic status have reported fewer cases compared to rich and stable countries such as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region (WHO-EMRO, 2020). This was perhaps due to the lack of accurate data and health systems in former countries.

In contrast, for example, the UAE announced emergency aid and decided on January 31, 2020 to provide all COVID-19 effected with free charge of medical care (MOHAP, 2020). Similar announcements and decisions were made in all GCC regions and some Arab countries. Such procedures slowed the spread of the virus, however, this could not happen without the cooperation of the public led by the media (especially social media) through multiple awareness campaigns in different languages, especially in the GCC region. Most Arab ministries of health stated to use social media to update, interact with the public and spread awareness about the virus and its treatment (Alwahaibi et al., 2020; MOHAP, 2020). Most journalists have used information and stories published on the Internet and social media by governmental, and non-governmental bodies (AlSadr, 2021) to report their news stories. The Governments of Libya, Egypt, Tunisia and Jordan had also applied emergency laws to limit the freedom of speech and expression to tackle the spread of information related to the pandemic and had also initiated domestic laws to control the narrative of the pandemic within their respective countries, thereby leading to a decrease in the press freedom score (AlAashry, 2022).

To our knowledge, this is the only study that uses ML to analyze and predict Arab journalists' adoption of social media. This research not only aims to understand the adoption of social media by Arab journalists but also predicts their future adoption, by answering the following research questions.

RQ1: How often do Arab journalists use social media as news sources and what their choices are?

RQ2: What are the most popular apps used as news sources by Arab journalists to write news stories?

RQ3: Which correct ML model needs to be employed to predict the respondent's future use of social media with high accuracy as well as the respondent's future use of social media to cover events?

Methods

Participants

A large cross-sectional survey of 1,443 Arab-journalists living across the Arab world was conducted through the Center for Research, Information and Documentation in Libya. Those who met the following criteria were recruited: frequently accessing social media (not only Facebook) for journalism; and online active journalists. After identifying potential respondents, a convincing sampling approach was used to invite and encourage journalists to participate in this study. This technique was used to select a sample from a larger population in such a way that each member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample (see, e.g., Tryfos, 1996 for further review). This methodology was employed, considering the timeframe of the study in 2020 obtain an unbiased result. The paper considers that 6-month time span is long for a study, especially in the nascent phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore, it strictly adheres to the repetitive patterns of usage to symbolize the existing trend.

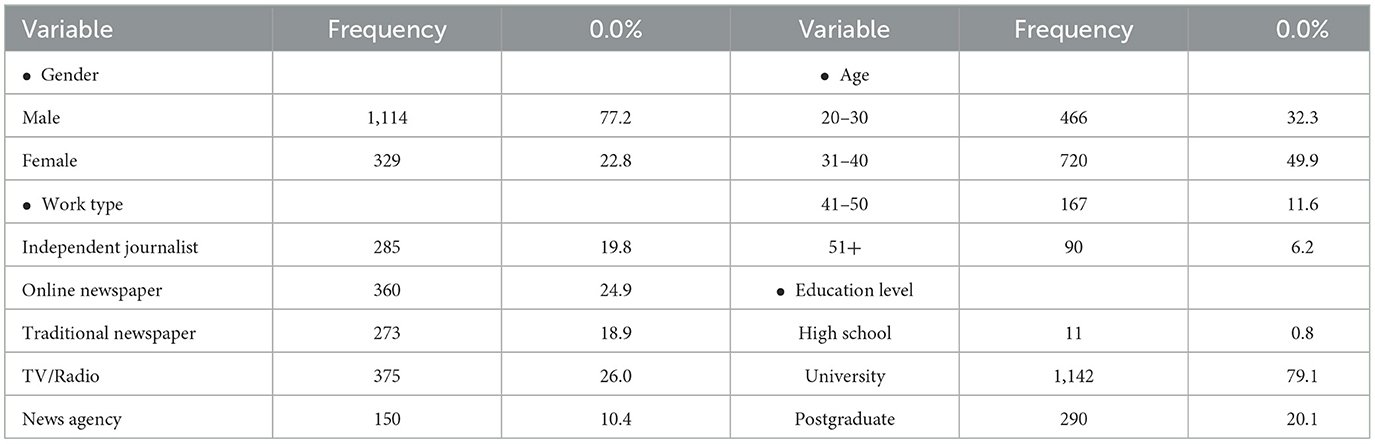

Data were collected between June and September 2020. Ethically, the data were collected anonymously, and the participant was completely voluntary which helped in drawing out more journalists and gathering their participation on sensitive issues. Table 1 shows the demographic sample. Note that in terms of gender distribution male respondents surpassed females. We have no clear explanation for this, but we acknowledged this as a sampling bias. At the same time, it can be assumed that this trend was noticed as more male journalists work in the Arab media sphere than women journalists. The ages of the respondents range from 20 to 51+. The main responses came from Mauritania (128), Jordan (123), Algeria (104), Tunisia (100), Iraq (99), Egypt (93), Morocco (92), Kuwait (87), Sudan (83), Saudi Arabia (71), Lebanon (69), Libya (63), Yemen and Palestine (both 59), Syria (58), Bahrain (54), UAE (42), Oman (36), and Qatar (23).

Questionnaire

An online survey was developed in Arabic and included several questions asking about how respondents used social media and their personal details (gender, age, education, work). The main reason for designing this questionnaire is that how much we can predict/estimate Arab journalists' use of such platform in the future or uncertainly time. The survey main questions were: Q1: “In general, how much do you use social media sites in journalism tasks?”. Q2: “With especially regarding COVID-19, to what extent do you depend on social media?”. Q3: “What is your most preferred social media Apps used to follow the COVID-19 news?”. Q4: “What are social media news stories that you follow?”, with 20 items measured on a three-point scale. In terms of internal validity, we asked three academic professors who are expert in journalism and check the validity of the questionnaire questions. The rate of agreement between three referees by chance was between 0.75 and 0.88 using Cronbach alpha test.

Data analysis

This paper utilizes couple of supervised ML techniques to predict the main factors deriving Arab journalists to use social media to accomplish their journalism tasks post-COVID-19 eras. To estimate a model's performance, a couple of models validations scores were used. The validation accuracy score estimates a model's performance on new data compared to the training data. We used the score to help us choose the best model. As a result, the following models were utilized:

• Decision Tree learning is one of the predictive modeling approaches used in ML (Quinlan, 1986). It uses a decision tree to go from observations (represented in the response to Q2, Q3 items 1–20) in this study to predict an item (represented in Q1). It relates to the decision-making process applied for selection of social media platforms and the frequency of the usage.

• K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN), is a supervised ML algorithm that can be used for both classifications as well as regression predictive problems (Fix and Hodges, 1951). It helps in further extrapolating the trend of social media usage by the Arab journalists, depending on their gender, education and age levels.

• Random Forests and Bagged Tree (RFBT) are an ensemble learning method for classification, regression and other tasks that operate by constructing a multitude of decision trees at training time and outputting the class that is the mode of the classes (classification) or mean/average prediction (regression) of the individual trees (Ho, 1995, 1998). Random decision forests correct for decision trees' habit of overfitting to their training set. Random forests generally outperform decision trees, but their accuracy is lower than gradient boosted trees. However, data characteristics can affect their performance.

• Principle Component Analysis (PCA), is the process of computing the principal components (eigenvectors) and using them to perform a change of basis on the data, sometimes using only the first few principal components and ignoring the rest. For high-dimensional data (e.g., with several dimensions more than 10) dimension reduction is usually performed to avoid the effects of the curse of dimensionality. For example, the curse of dimensionality in the K-NN context means that the Euclidean distance is unhelpful in high dimensions because all vectors are almost equidistant to the search query vector (imagine multiple points lying more or less on a circle with the query point at the center; the distance from the query to all data points in the search space is almost the same). Hence, feature extraction and dimension reduction can be combined in one step using PCA.

Results

Social-media use

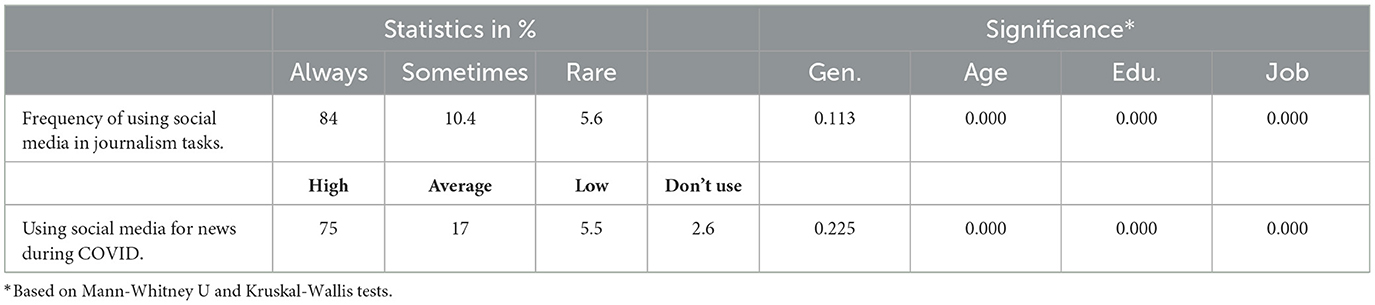

Respondents indicated using different social media platforms in general (RQ1). The majority of respondents indicated using social media sites “always”, while some used it “sometimes” or “rarely”. Not surprisingly, the popularity of social media sites among Arab journalists is already confirmed by early studies (Ziani et al., 2017; Mansour, 2018; Richter and Kozman, 2021). For example, Mansour (2018) found that most Egyptian journalists spent between 4 and 5 h daily using social media for their work.

Demographic differences in using social media in journalism tasks

The study found that social media platforms were reportedly used more by male than female journalists while taking into account that there is an unequal stakeholdership of male and female journalists in the Arab newsrooms (Table 2). Those aged 31–40 were more likely than other aged groups to regularly use social media in journalism tasks. This also applied to journalists at the university level and who work in traditional newspapers. Regarding COVID-19 news, the majority of respondents indicated highly relying on social media for such news. Female journalists were slightly more likely than males to use social media for COVID-19 news information. Those journalists aged 20–30 were more likely to depend on social media for COVID-19 news than other aged groups. This applied to those with high-school level and work in online newspapers.

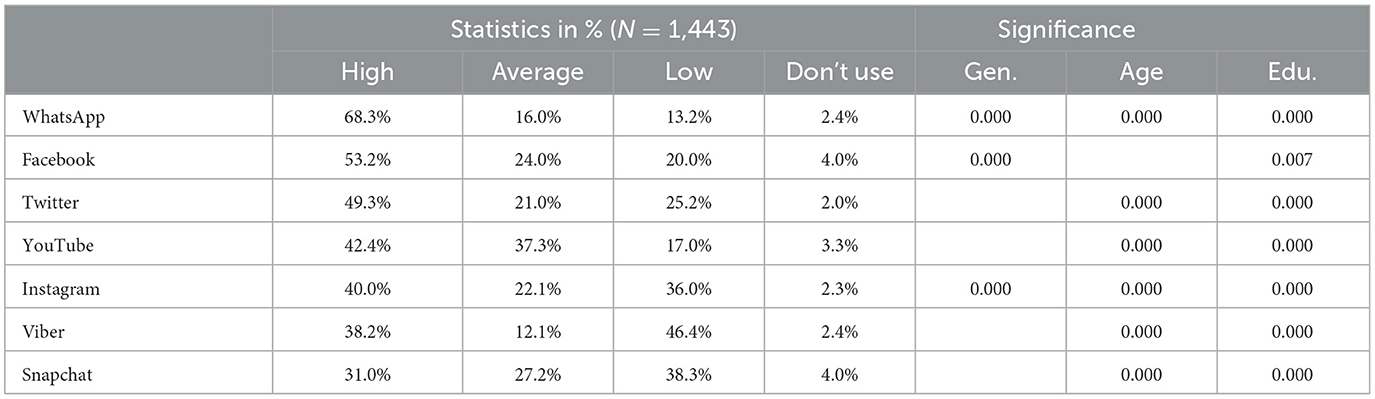

Social media apps as a source of news

Respondents were asked to state how often they used apps as a source of news (RQ2). Our results confirmed the emergence of WhatsApp and Facebook over others (Table 3). These two platforms were named as the most frequently used. Twitter and YouTube closely followed while Instagram, Viber, and Snapchat were lastly listed, with some variation evident between these platforms. Such results are consistent with past research indicating the usability of apps by journalists and others in the Arab and non-Arab worlds (Pavlik, 2000; Lewis and Molyneux, 2018; Djerf-Pierre et al., 2019; Geçer et al., 2020).

Demographic differences in using apps for news sources

Significantly, female journalists preferred Facebook as a main source for their gathering and producing news stories followed by Instagram and WhatsApp (Table 3). Those aged 20–30 were more likely than others to prefer Twitter, Viber, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and WhatsApp. Those with a high school level were more likely to do so compared to other aged groups for Twitter and WhatsApp. Facebook and Viber were preferred by journalists at postgraduate level than the others, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube were preferred by journalists at the university level.

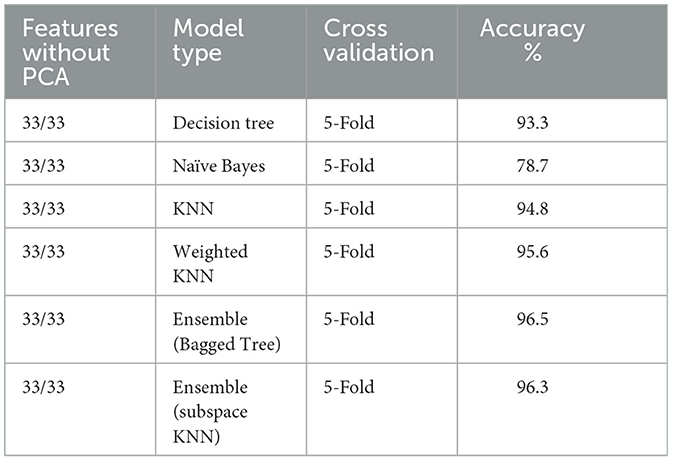

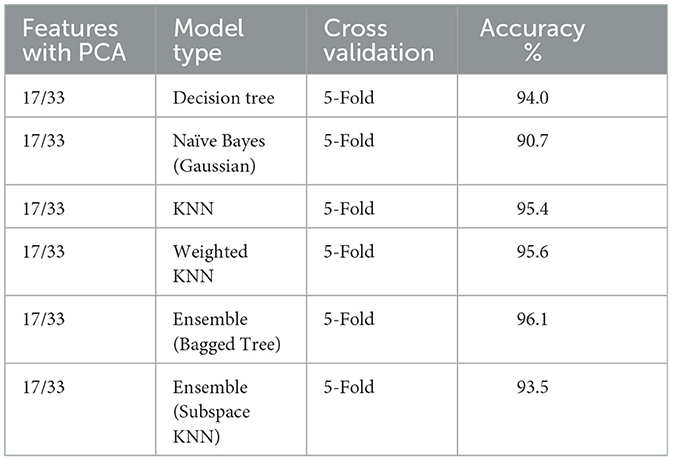

Social media usage predictions using different ML models

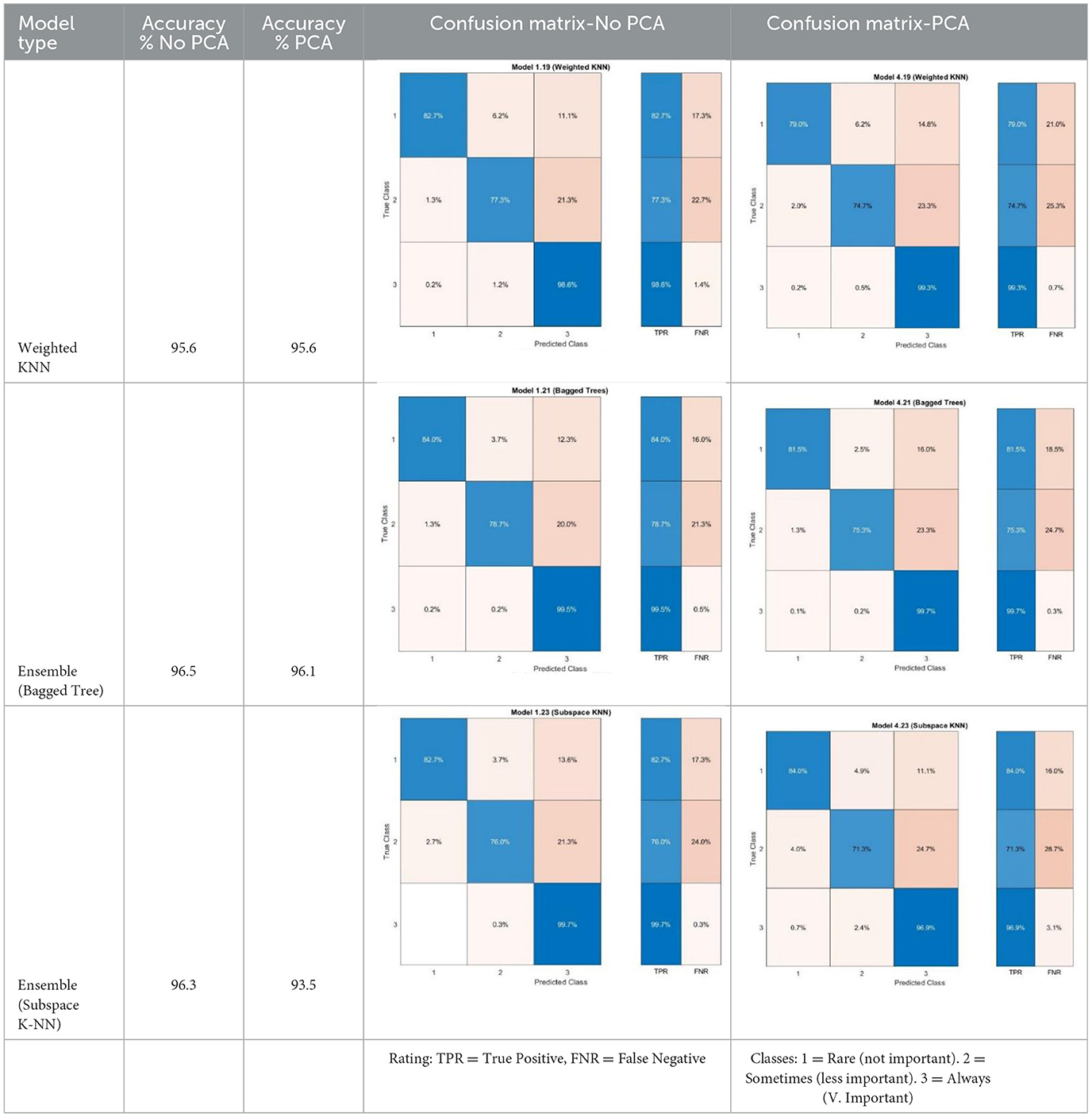

The best model that predicted the future use was the Ensemble (Bagged Tree) with an accuracy score obtained >96% (Tables 4A, 4B) (RQ3). This score represented the validation accuracy, which estimated the model's performance on new data compared to the training data. The score helped to choose the best model. For cross-validation, the score was the accuracy of all observations, counting each observation when it was in a held-out fold. Tables 4A, B showed the total observed points used of 1,443 rows and 34 columns of which (Q1) was used as a response and the rest 33 features (Q2–Q4 and beyond) were used as predictors. They contain the used models on all the features before using the dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA). Three models achieved the desired accuracy rate (>95%). Again the Ensemble model was the best performing with accuracy (>96%). In Table 5, the PCA was used to reduce the number of predictors used. Only 17 out of 33 variables were kept. The explained variance per component (in order) were as follows (Q2 = 66.6%, Q3.1 = 8.6%, Q3.2 = 4.2%, Q3.3 = 3.1%, Q3.4–Q3.8 = the range were 1.8 to 1.0%). The rest of the questions were insignificant to explain the model, hence were omitted. Figure 1 illustrates the visual explanation of the Ensemble model.

Furthermore, Table 5 presents the resulted Confusion Matrix (CM) of all the used models on the collected data set assessing the winner models that best predict how Arab journalist use social media in future journalism tasks.

While the fourth column above showed the model's results before applying the PCA, the fifth column presented the results after applying PCA. The inner columns for each CM showed the predicted classes. For example, the Weighted K-NN in the top row indicated that 84% of the journalists' opinions are correctly classified, meaning the true positive rate (TPR) for correctly classified points in this class, is shown in the highlighted cell in the TPR column. The False Negative (FNR) for incorrectly classified points in this class was 17.3%, shown in the light cells in the FNR column. Positive predictive values are in blue for the correctly predicted points in each class, and false discovery rates are in light colors for the incorrectly predicted points in each class.

Discussions and conclusion

Social media has changed how Arab journalists produce and share their news stories, helping to connect with each other as well as the public (Alawneh and Muhammed, 2016; Mansour, 2018; Fatima, 2020; Khamis and El-Ibiary, 2022). An online survey attempted to examine how Arab journalists use social media as news sources during COVID-19 outbreak (Khamis and Vaughn, 2011; Lewis and Al Nashmi, 2019) to better understand their usage and exercise. These journalists reported regularly access digital media during COVID. This study is one of its kind to examine such a subject on a large scale in the Arab countries, however, given all the heterogeneous among them in terms of the media system, media freedom, regulations, and finance the findings need to be understood with caution. The study also does not aim to generalize the results, especially taking into consideration the minute diversities existing within the pan-Arab world, in terms of state, citizenship, gender, religion, class etc. At the same time, the study done during the nascent phase of the COVID-19 pandemic does take into account that the trends, patterns and statistics would change as pandemic continued and cannot be studied in isolation. While the pandemic has undoubtedly accelerated the adoption of social media among journalists due to lockdowns and restrictions, it is important to recognize that the circumstances driving this reliance may not persist once the pandemic subsides. Our research aims to contribute to the theory by offering insights into the immediate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Arab journalists' social media usage patterns. Rather than making broad predictions about post-pandemic behavior, our focus is on understanding the specific context of crisis situations and times of uncertainty, which may necessitate increased reliance on social media for journalism.

In response to RQ1, evidence emerged here that respondents relied on social media platforms to produce and share their news stories (al-Az'azi, 2015; AlSadr, 2021; Mahamed et al., 2021). The way they used social media, especially during COVID-19, not only highlighted their interest but also their firm adoption to cover different news issues regarding COVID-19. Arab media organizations seemed they are welling to adopt social media in their work (Alawneh and Muhammed, 2016; Al-Rawi, 2020). However, this study did not examine organizations' perceptions; it mainly looked at the journalists' use in general trying to understand their usage.

Furthermore, differences usage of social media platforms occurred among respondents with younger and well-educated males working in traditional newspapers indicating so, compare with younger females working for online press, and findings confirmed Bruns' (2018) assumption. During COVID-19, it seemed that high-school-younger females working for online press were slightly more likely than males to use social media for their news. The way they access and use technologies has enhanced such use so that they were able to adopt social media in their work. Research indicates the dominance of social media as the main source of news in the Arab world, see, e.g., Mansour (2018). Others indicated that social media are used as a news-reporting mechanism and a news-sharing system especially during such uncertain times (Cottrill, 2015). In contrast, Mounir (2017) found that Algerian journalists did not use social media in their work as a main source of news due to a lack of information trust, and they preferred traditional sources. Alawneh and Muhammed (2016) found that Jordanian journalists rarely used Facebook and if so, they mainly for reading and searching for news stories. This was due to a lack of knowledge and skill on how to use Facebook in their work.

Respondents also indicated their usage of social media to communicate and for news organizations to reach a wider (Cottrill, 2015; Lee, 2015) (RQ2). WhatsApp has superseded its owner (Facebook) as the most preferred platform (Elareshi and Ziani, 2019). Twitter, YouTube and Instagram were less preferred (Lewis and Molyneux, 2018; Djerf-Pierre et al., 2019). These findings were in line with studies indicating that most journalists are active in social media as an “obvious and necessary step in journalism's digital-first transformation” (Lewis and Molyneux, 2018, p. 11). This could be for news ideas and share stories with the readers (Thomas, 2013; al-Az'azi, 2015; Safori, 2018).

The deep analysis revealed that we can predict with a very high degree of accuracy, how much an Arab journalist uses social media (various platforms) to accomplish the journalism tasks (RQ3). We themed our analysis around the different types of ML techniques to reach a high level of prediction accuracy with the datasets available. Following this, we deepened our analysis and presented a dimensionality reduction technique PCA, to serve three purposes: First, it helped in finding out the dominant features to predict the main factors deriving the Arab journalists to use social media to accomplish their journalistic practice. Second, it focused on future analysis using lightweight surveys (by limiting the number of questions needed) to arrive at almost the same accurate predict results. Finally, we highlighted some of the common ensemble ML techniques that outperformed their counterparts such as the Ensemble (Bagged Tree) vs. the regular Decision Tree and the Ensemble (Subspace KNN) vs. the simple KNN. It is also observed—as part of our systematic deep review—that the Weighted KNN accuracy remained the same with and without the use of PCA, which helped in future analysis decisions. Therefore, it is concluded that ML models were successfully used and predicted the continued use of major social media platforms by Arab journalists to cover future events. However, this means that our results are restricted to predict and cover only similar crises and times of uncertainly. For example, being locked down during COVID-19, Arab journalists were forced to depend on social media, but having the liberty of movement after COVID-19 may (may not) decrease/increase their dependency on and type of use of social media for journalism.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations can be highlighted in this research. For example, the use of online survey it has its own problematic, thus the generalizability of our findings is limited to those participating in this study. However, considering the time, cost-effectiveness, and restrictions during early COVID-19 period, the contribution of our results is linked to clear similarities and consistency to other studies in the same field. Therefore, more studies and deep analysis are needed to understand and predict use of social media and its future in Arab journalism field. Other futuristic studies in this domain can adopt other theories such as Uses and Gratifications model while contextualizing it with machine learning. Different other forms of sampling methods can also be used. We also noted that many other ML techniques not used in this paper might lead to more reliable results. Given this, we intend to update future research efforts repeatedly with new techniques. Finally, this research used a survey method to conduct the data, however, other research methods, such as a qualitative approach or even mixed methods may be conducted to study the same themes among Arab professionals and journalists.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Bahrain – Mass Communication, Tourism, and Arts Department Scientific Research Committee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

ME: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. AA: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SC: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer MH declared a past co-authorship with the author(s) ME and AZ to the handling editor.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AlAashry, M. S. (2022). A critical analysis of journalists' freedom of expression and access to information while reporting on COVID-19 issues: a case of selected Arab countries. J. Inform. Commun. Ethics Soc. 20, 193–212. doi: 10.1108/JICES-06-2021-0066/FULL/HTML

Alam, F., Shaar, S., Dalvi, F., Sajjad, H., Nikolov, A., Mubarak, H., et al. (2020). Fighting the COVID-19 infodemic: modeling the perspective of journalists, fact-checkers, social media platforms, policy makers, and the society. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv: 2005.00033. doi: 10.18653/v1/2021.findings-emnlp.56

Alandijany, T. A., Faizo, A. A., and Azhar, E. I. (2020). Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries: current status and management practices. J. Infect. Public Health 13, 839–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.020

Alawneh, H., and Muhammed, S. (2016). Jordanian journalists' uses of Facebook and the gratifications gained: a survey study on a sample of Jordanian journalists. Alman. J. 22, 301–362 [in Arabic].

al-Az'azi, W. (2015). Yemeni journalists' use of social networks and satisfaction gained: a survey study. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 41, 75–133 [in Arabic].

Alhuntushi, A., and Lugo-Ocando, J. (2020). Articulating statistics in science news in Arab newspapers: the cases of Egypt, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. J. Pract. 16, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1808857

Al-Jenaibi, B. (2020). The role of Twitter in opening new domains of discourse in the public sphere: social media on communications in the Gulf countries. Int. J. Inform. Syst. Soc. Change 11, 1–18. doi: 10.4018/IJISSC.2020070101

Al-Najjar, A. (2011). Contesting patriotism and global journalism ethics in Arab journalism. J. Stud. 12, 747–756. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2011.614811

Al-Rawi, A. (2020). Social media and celebrity journalists' audience outreach in the MENA region. Afr. J. Stud. 41, 17–32. doi: 10.1080/23743670.2020.1754266

AlSadr, A. (2021). Abu Dhabi Festival Launches Young Media Leaders Forum in Partnership With American University of Sharjah. Dubai Global News. Available online at: https://www.dubaiglobalnews.com/2021/03/15/206726/ (accessed March 15, 2021).

Alwahaibi, N., Al-Maskari, M., Al-Dhahli, B., Al-Issaei, H., and Al-Bahlani, S. (2020). A review of the prevalence of COVID-19 in the Arab world. J. Infect. Dev. Count. 14, 1238–1245. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13270

Amici, P. (2020). Humor in the age of COVID-19 lockdown: an explorative qualitative study. Psychiatria Danubina 32, 15–20.

Badr, H. (2021). Social Media and the Internet in the Arab Region: What Remains Ten Years After the Arab Uprisings? Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Available online at: www.kas.de (accessed August 31, 2021).

Ball-Rokeach, S. J., and DeFleur, M. L. (1976). A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun. Res. 3, 3–21. doi: 10.1177/009365027600300101

Bossio, D. (2017). Journalism and Social Media: Practitioners, Organisations and Institutions. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Boyd, D., and Ellison, N. (2007). Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comp. Med. Commun. 13, 210–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Broersma, M., and Eldridge, S. A. (2019). Journalism and social media: redistribution of power? Media Commun. 7, 193–197. doi: 10.17645/mac.v7i1.2048

Bruns, A. (2018). Gatewatching and news curation: Journalism, social media, and the public sphere. Peter Lang. 113, 293. doi: 10.3726/b13293

Cottrill, E. (2015). Journalists' Use of Social Media Evolves. AXIA. Available online at: https://www.axiapr.com/blog/journalists-use-of-social-media-evolves (accessed January 14, 2021).

Djerf-Pierre, M., Lindgren, M., and Budinski, M. (2019). The role of journalism on YouTube: audience engagement with “superbug” reporting. Media Commun. 7, 235–247. doi: 10.17645/mac.v7i1.1758

Elareshi, M., and Ziani, A. (2019). Digital and interactive social media among Middle East women: empirical TAM study. Media Watch 10, 235–250. doi: 10.15655/mw/2019/v10i2/49642

Elareshi, M., Ziani, A., and Al Shami, A. (2020). Deep learning analysis of social media content used by Bahraini women: WhatsApp in focus. Convergence, 27, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/1354856520966914

El-Elimat, T., AbuAlSamen, M. M., Almomani, B. A., Al-Sawalha, N. A., and Alali, F. Q. (2021). Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS ONE 16, e0250555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250555

Elkalliny, S. (2021). The Impact of Social Media on Arab Health Risk Perception During COVID-19. Egypt: Arab Media and Society.

Fahmy, N., and Abdul Majeed, M. (2020). A field study of Arab data journalism practices in the digital era. J. Pract. 15, 170–191. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2019.1709532

Fahmy, S., Taha, B. M., and Karademir, H. (2022). Journalistic practices on Twitter: a comparative visual study on the personalization of conflict reporting on social media. Online Media Glob. Commun. 1, 23–59. doi: 10.1515/omgc-2022-0008

Fatima, S. S. (2020). Understanding the Construction of Journalistic Frames During Crisis Communication. Stockholom: Södertörn University | School of Social Sciences.

Fix, E., and Hodges, J. L. (1951). Nonparametric discrimination: consistency properties. Randolph Field Texas Project 21–49. doi: 10.1037/e471672008-001

Geçer, E., Yildirim, M., and Akgül, Ö. (2020). Sources of information in times of health crisis: evidence from Turkey during COVID-19. J. Public Health From Theory Pract. 1, 1113–1119. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/x76mn

Ghannam, J. (2012). Digital Media in the Arab World One Year After the Revolutions. Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance.

Gody, A. (2021). Using Artificial Intelligence in the Al Jazeera Newsroom to Control Fake News. Al Jazeera Media Institute. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355058898 (accessed October 16, 2021).

Ho, T. K. (1995). “Random decision forests (PDF),” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (Montreal, QC), 278–282.

Ho, T. K. (1998). The random subspace method for constructing decision forests. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Machine Intellig. 20, 832–844. doi: 10.1109/34.709601

Jallow, A. Y. (2015). The emerging of global journalism and social media. Global Media J. 13, 1–10. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2628915

Jamil, S., and Appiah-Adjei, G. (2020). Battling with infodemic and disinfodemic: the quandary of journalists to report on COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Media Asia 47, 88–109. doi: 10.1080/01296612.2020.1853393

Khamis, S., and El-Ibiary, R. (2022). Egyptian women journalists' feminist voices in a shifting digitalized journalistic field. Digital J. 10, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2022.2039738

Khamis, S., and Vaughn, K. (2011). Cyberactivism in the Egyptian revolution: How civic engagement and citizen journalism tilted the balance. Arab Media Soc. 13.

Kirat, M. (2020). “Journalists in the United Arab Emirates,” in The Global Journalist in the 21st Century, eds D. Weaver and L. Willnat (New York, NY: Routledge), 458–469.

Lee, J. (2015). The double-edged sword: the effects of journalists' social media activities on audience perceptions of journalists and their news products. J. Comp. Mediat. Commun. 20, 113. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12113

Lee, J. (2016). Opportunity or risk? How news organizations frame social media in their guidelines for journalists. Commun. Rev. 19, 106–127. doi: 10.1080/10714421.2016.1161328

Lewis, N. P., and Al Nashmi, E. (2019). Data journalism in the Arab region: role conflict exposed. Digital J. 7, 1200–1214. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1617041

Lewis, S. C., and Molyneux, L. (2018). A decade of research on social media and journalism: assumptions, blind spots, and a way forward. Media Commun. 6, 11–23. doi: 10.17645/mac.v6i4.1562

Litvinenko, A., Borissova, A., and Smoliarova, A. (2022). Politicization of science journalism: How Russian journalists covered the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Stud. 23, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2021.2017791

Lynch, M. (2015). How the media trashed the transitions after the Arab spring. J. Democr. 26, 90–99. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0070

Mahamed, M., Omar, S. Z., and Krauss, S. E. (2021). Understanding citizen journalism from the perspective of young journalists in Malaysia. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 26, 133–144.

Mansour, E. (2018). The adoption and use of social media as a source of information by Egyptian government journalists. J. Librarian. Inform. Sci. 50, 48–67. doi: 10.1177/0961000616669977

McPhail, T., and Phipps, S. (2020). Global Communication: Theories, Stakeholders, and Trends, 5th Edn. New York, NY: Wiley Blackwell.

Melki, J., and Kozman, C. (2021). Media dependency, selective exposure and trust during war: media sources and information needs of displaced and non-displaced Syrians. Media War Conflict. (2021) 14, 93–113. doi: 10.1177/1750635219861907

MOHAP MOHAP-UAE, Ministry of Health and Prevention, United Arab of Emirates. (2020). SEHA Opens 13 Additional Drive-Through COVID-19 Testing Centres. MOHHAP-UAE. Available online at: https://www.mohap.gov.ae/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/2365.aspx (accessed November 20, 2020).

Mounir, E. (2017). Algerian journalists' use of social networks as a source of news “Facebook and Twitter as a model”: a descriptive study on a sample of the journalist of the written, audio and video sector in Algeria. Al-Resala J. Media Stud. 1, 219–242 [in Arabic].

Newman, N. (2022). Journalism, Media, and Technology Trends and Predictions 2022. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2022 (accessed November 05, 2022).

O'Rourke, S. (2011). Teaching journalism in Oman: reflections after the Arab spring. Pacific J. Rev. 17, 109–129. doi: 10.24135/pjr.v17i2.354

Osmann, J., Selva, M., and Feinstein, A. (2021). How have journalists been affected psychologically by their coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic? A descriptive study of two international news organisations. BMJ Open 11, e045675. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045675

Pavlik, J. (2000). The impact of technology on journalism. J. Stud. 1, 229–237. doi: 10.1080/14616700050028226

Rane, H., and Salem, S. (2012). Social media, social movements and the diffusion of ideas in the Arab uprisings. J. Int. Commun. 18, 97–111. doi: 10.1080/13216597.2012.662168

Richter, C., and Kozman, C., (eds). (2021). Arab Media Systems. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers.

Sultan, N. (2013). Al Jazeera: reflections on the Arab spring. J. Arab. Stud. 3, 249–264. doi: 10.1080/21534764.2013.863821

Tank, T. T., and Ari-Matti, A. (2012). Social Media - The New Power of Political Influence. Brussels: Suomen Toivo, 1–16.

Thomas, C. (2013). The Development of Journalism in the Face of Social Media Relationship to the Audience: A Study on Social Media's Impact on a Journalist's Role, Method and Relationship to the Audience (Sweden), 1–72.

Weaver, D., and Willnat, L. (Eds.). (2012). “The global journalist in the 21st century: Conclusion,” in The Global Journalist in the 21st Century (Routledge), 527–552.

WHO-EMRO (2020). WHO-EMRO, World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office. WHOEMRO. Available online at: https://twitter.com/WHOEMRO/status/1231987263220912128?s=20 (accessed November 12, 2020).

Wolfsfeld, G., Segev, E., and Sheafer, T. (2013). Social media and the Arab Spring: politics comes first. Int. J. Press Polit. 18, 115–137. doi: 10.1177/1940161212471716

Keywords: Arab journalists, Ensemble Bagged Tree, decision tree, online journalism, social media, Weighted KNN, COVID-19

Citation: Elareshi M, Al Shami A, Ziani A, Chaudhary S and Youssef N (2024) Predicting the level of social media use among journalists: machine learning analysis. Front. Commun. 9:1369961. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1369961

Received: 13 January 2024; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 19 March 2024.

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Yaron Ariel, Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel, IsraelMohammed Habes, Yarmouk University, Jordan

Copyright © 2024 Elareshi, Al Shami, Ziani, Chaudhary and Youssef. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mokhtar Elareshi, melareshi@sharjah.ac.ae

Mokhtar Elareshi

Mokhtar Elareshi Ahmad Al Shami

Ahmad Al Shami Abdulkrim Ziani

Abdulkrim Ziani Shubhda Chaudhary4

Shubhda Chaudhary4  Noora Youssef

Noora Youssef