A Thematic Approach to Realize Multidisciplinary Community Service-Learning Education to Address Complex Societal Problems: A-Win-Win-Win Situation?

- Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences (FALW), Athena Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Universities are under increasing pressure to become more and better involved in society as part of their third mission, to which Community Service learning (CSL) can contribute. To date, most CSL projects are mono-disciplinary, single courses, often of a short-term nature. In order to address the increasingly complex problems facing society, there is a need to adopt multi–and interdisciplinary CSL approaches that allow for a range of perspectives. The article describes and analyzes how a thematic CSL approach was initiated at the VU Amsterdam starting from the needs of a local community. Once loneliness was identified as an important and relevant issue, the approach evolved in order to include multiple courses and internships from different programs offered by two faculties and various stakeholders and community organizations. Taking an action–research approach, the CSL team evaluated the process of its development, outcomes and contributions, as well as possible benefits and considerations. In addition to more tangible outcomes arising from many student projects, the approach assists in building new community networks, supports project continuity, deepens knowledge, encourages new collaborations, reduces CSL-created workload and finally increases student development, motivation and sense of ownership. Overall, it can be concluded that the thematic approach can contribute to addressing complex problems as it allows for multidisciplinary collaborations while not imposing too great a burden on the established curriculum. This makes the thematic CSL approach a valuable stepping stone in advancing CSL in universities, and so contribute to fulfilling their third mission.

Introduction

Universities’ so-called third mission has been broadly understood as conscious and strategic actions to make a greater contribution to society. This includes activities involving the generation, use, application and exploitation of knowledge and other capabilities outside academic environments (Koryakina et al., 2015). Universities are under increasing pressure to be more and better involved in society as part of their third mission (Zomer and Benneworth, 2011; Compagnucci and Spigarelli, 2020).

Community Service Learning (CSL) (as defined by Bringle and Hatcher, 1995 p. 112) is a pedagogy that contributes to the third mission as it promotes students’ learning through their active participation in experiences of community engagement (Folgueiras et al, 2020). It is considered an effective pedagogy for improving social engagement and at the same time enhancing students’ skills and aptitudes. CSL stimulates (among others) critical thinking, problem-solving competencies, personal development, interpersonal skills and cultural understanding (Conway et al, 2009; Celio et al, 2011; Warren, 2012; Yorio and Ye, 2012; Aramburuzabala et al, 2019). Moreover, CSL has the potential to benefit community partners. In addition to more direct tangible outcomes as a result of a project, CSL activities are said to increase community capacity as they have the potential to bring together various community partners and members (Gelmon, 2001; Vernon and Foster, 2002; Norton et al., 2018). It has also been suggested that CSL can benefit faculty members as it fosters personal growth (Harrison, et al, 2013) and improves teaching experience (Pribbenow, 2005) and practices (Bringle, 2017).

Notwithstanding these benefits, CSL has as yet unexplored potential. A recent literature review of the design principles for integrating CSL into higher education courses noted that most CSL activities are assignments for students to address social issues from the perspective of a specific discipline or program (Tijsma et al., 2020). Of the 20 CSL case studies included in that review none took a multidisciplinary approach. Rather, the case studies discussed courses in a specific disciplinary domain, although the field of study varied greatly from public relations to Spanish, statistics, geriatrics, IT, marketing and others. This suggests that CSL has potential benefits across a range of disciplines but that the existing literature reports only limited crossover between them. Moreover, concerns have been raised about the short-term time investment linked to most CSL projects conducted as part of existing courses (Tryon and Ross, 2012). More specifically, these issues relate to students’ lack of commitment, ethical issues when working with vulnerable groups, lack of capacity to train or supervise short-term CSL students, and issues relating to timing and project management (Tryon and Ross, 2012). These issues could lead to exploiting the goodwill of community partners. Indeed, studies on the perspectives of community partners have shown they would like ways to develop longer-term CSL activities (Sandy and Holland, 2006).

The mono-disciplinary, single course and short-term nature of most CSL projects becomes especially problematic given that the world is facing increasingly complex problems such as sustainability and social segregation (Delano-Oriaran et al., 2015). These problems never have clear-cut solutions and are often dynamic (Ramaley, 2014). Addressing these problems involves many stakeholders with different values and priorities. Indeed, addressing ‘wicked’ problems requires an approach that builds upon various (disciplinary) perspectives (Fitzgerald et al, 2012; Huang and London, 2016; Ramaley, 2014). This makes it necessary to establish new kinds of engagement that build true university–community partnerships based on reciprocity and mutual benefits and with an intentional focus on resolving a wide range of complex societal problems (Fitzgerald et al., 2012).

In this article we present and analyze the findings of a Dutch university in attempting to contribute to this objective. More specifically, we describe and analyze how the CSL team of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (henceforth the VU Amsterdam), developed and experimented with a ‘thematic CSL approach’ to address complex societal issues. The aim of this approach was to involve multiple courses and internships from various programs in different faculties and involving a range of stakeholders and community organizations in this overall CSL activity in order to contribute to addressing a complex societal issue. With this case study we aim, first, to evaluate the benefits and related considerations of a thematic CSL approach; and second, to examine how the approach contributed addressing a complex societal issue in the local area of Amsterdam New-West.

Context of the Case Study

The VU Amsterdam states in its Strategic Plan 2020–2025 that it takes responsibility for people and the planet by offering values-driven education. One of the strategies to realize this is to develop future-proof forms of education (Strategy VU 2020–2025 p. 43). Among other goals, the VU Amsterdam plans to make CSL university-wide. In order to realize this, in 2018 the VU established a Community Service-Learning program as part of a wider ‘Broader Mind’ student program. The CSL team, consisting of lecturers, researchers and support staff, develops this CSL program. CSL is described in the Educational Vision of the VU Amsterdam as a form of education in which students apply their knowledge and skills for the benefit of society and learn from the experience (VU Amsterdam Educational Vision, 2018). The CSL team investigates implementation strategies for CSL in the VU Amsterdam.

At the start of Community Service-Learning program, the CSL team organized a ‘Meet & Match’ event in the local area of Amsterdam New-West. The aim of the event was to identify societal issues that could be addressed by students as part of the educational program. In total 43 people participated in the event including; local civil society organizations (CSOs), representatives of the municipality of Amsterdam, teachers, researchers and students from the VU Amsterdam, and residents from the city district Amsterdam New-West. Through focus group discussions (FGDs) with those participants, ‘loneliness’ (Box 1) was identified as one of the major constraints people in the area were facing. Following this, there were joint reflections between the CSL team and various stakeholders to define ‘how students of the VU Amsterdam could contribute to addressing ‘loneliness’ in Amsterdam New-West. These joint reflections led to the conclusion that it would be complex (and unethical) to address loneliness in a single course within a single program. Therefore, the CSL team decided to experiment with a ‘thematic CSL approach’ that clustered multiple courses and internships from a range of programs offered by different faculties to address one complex issue.

BOX 1 Description of the complex problems of loneliness.

Loneliness is a complex problem, since it involves various dimensions. First, there are divergent reasons for a person to feel lonely; it could include infrequent participation in social activities, having few social contacts, and feeling that you don’t belong to any group. Moreover, there is a fragmentation of knowledge amongst the stakeholders (e.g., elderly residents, policymakers, housing providers, healthcare providers and technology developers), and their interests often do not converge. Therefore, effective actions to deal with the problem requires multi-stakeholder approaches that bring together different perspectives and narrow the gap between them (Williams and Braun, 2019).

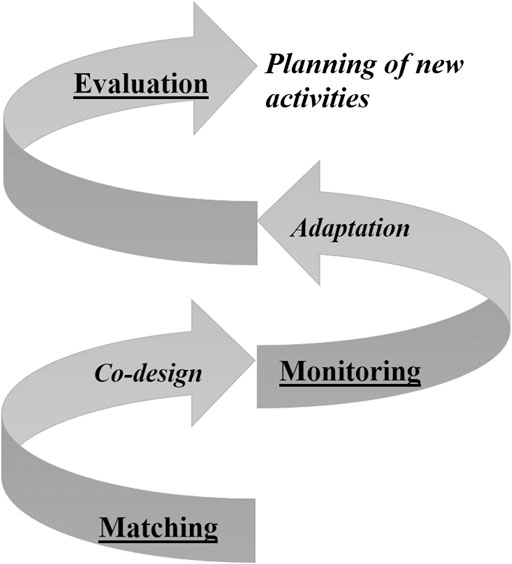

To develop ‘the thematic CSL approach’, the CLS team adopted an action–research approach (Lewin, 1946). This implies that the team seeks to realize transformative change in the university through the simultaneous process of taking action and doing research (Lewin, 1946). Analogous to the action research spirals, within this process we recognize three steps; matching of societal issues and course objectives, employing co-creation methods; monitoring, which could result in adaptation during the project; and evaluation, which results in planning new activities (Figure 1). The focus here will be on the benefits and the related considerations of the thematic approach and how it contributed to addressing the complex issue of loneliness—namely, the evaluation of the thematic approach. We also consider some of the background in the matching and monitoring, which is crucial in understanding the complexity of such a thematic approach. The following section will describe the development of the thematic approach initiative in relation to loneliness, mainly in relation to the matching and monitoring aspects. The method section describes how the evaluation was conducted, and the results reports on the benefits, considerations and the way the thematic approach contributed to addressing loneliness.

Development of the Thematic Approach

In this section we describe the development of the thematic approach in addressing the issue of loneliness in Amsterdam New-West. First, we describe how we identified specific community needs in relation to loneliness through a second ‘Meet & Match’ event. We then describe how each student project, consisting of courses or internships clusters, was matched to those needs (and to others subsequently identified), and monitored by the CSL team as part of the action research spirals.

In June 2018, a second ‘Meet & Match’ event was organized, the aim of which was to establish specific collaborations between the VU Amsterdam (through students’ projects) and local stakeholders of Amsterdam New-West in the theme loneliness. In total, 39 people participated in the event. The local stakeholders included four members of the municipality, two members of social housing corporations, two staff members of vocal education, ten representatives from various CSOs (such as VoorUit, Movisie, GGD and Combiwell), and two residents. The CSL team also identified and invited lecturers from the VU Amsterdam who were involved in teaching and/or research topics related to loneliness. From the VU 12 lecturers, three program directors and four administrative staff members attended. For all participants the overarching (main) research question was how to address loneliness in Amsterdam New-West. As expected, in assessing ‘loneliness’ with the various stakeholders the complexity of the issue became evident. For instance, depending on the affiliation of the stakeholders the target groups differed. Some stakeholders were specifically interested in the needs of local residents (housing organizations) whereas others were more interested in how the collaborations between various organizations might contribute to addressing the issue (municipality). This links back to the nature of loneliness as a complex problem and the need for multi-stakeholder approaches (Box 1).

Based on the needs of community members and partners, various topics were identified that led to several research questions to which students from different study programs could contribute as part of their course assignments and/or during their research internship. In general, research topics concerned loneliness in relation to poverty or elderly people, the role of communities and community cohesion, detection of loneliness, different forms of loneliness and taboos regarding loneliness. One specific research need identified by the municipality and two CSOs was to gain more insights into how policy changes could contribute to community capacity building in order to reduce loneliness in Amsterdam New-West. Among the lecturers, the coordinator of the course Analysis of Governmental Policy (AGP) that is part of the Master’s in Management Policy Analysis and Entrepreneurship (MPA) expressed an interest in addressing this question with the help of students enrolled on the course. As a result, at the event the AGP course was matched to address community needs in relation to recommendations regarding policy changes.

The AGP course is an existing CSL course offered to 150 students every year. It was offered in September–October 2018 and one of its learning goals is to write a policy advisory report on a complex issue related to health and life sciences in a group of 12 students. The course coordinator works with various commissioners. There was a direct match with the question, and the research could start relatively quickly. The course was closely monitored by one of the CSL team members, specifically in relation to the communication and collaboration between the students and the community partner. For example, students’ emails were looked at before they were sent to the commissioner, and the questionnaire used to gain insights into the community needs was thoroughly checked and revised before it was used. At the end of AGP course, 12 students made recommendations especially relevant to the municipality, but also for the two CSOs involved.

As a result of the initial phase of the research, questions for follow-up research arose. For example, one of the recommendations made by the APG course was to increase awareness of local activities, such as walk-in coffee moments and other social activities, among lonely residents. The question was how communication with these lonely residents could be organized. In order to address this, the CSL team assessed which bachelor’s or master’s programs could be matched to this research question and which courses, preferably offered between November 2018 and June 2019.

Health-related bachelor’s and master’s programs were assessed and discussions were organized with their lecturers about CSL opportunities. This resulted in a match with the second-year Health Communications course offered to about 50 students in the BSc in Health Sciences. The main learning goal is to develop and evaluate a communication intervention aimed at addressing a specific health problem within a well-defined target group. This course was identified as having the potential to provide insights into communication approaches regarding lonely residents. Together with the CSL team, some parts of the course were re-designed. For instance, lecturers with in-depth knowledge on loneliness were invited to give a presentation to better prepare the students and provide insights on the topic.

Three additional follow-up questions from the AGP course were identified in collaboration with community partners, namely the municipality and one CSO. These follow-up questions concerned the meaningful participation of lonely residents, the needs of key residents to increase community building, and factors related to successful cooperation in community coalitions. These topics require in-depth insights. Again, the CSL team assessed existing programs with the potential to deal with the relevant research questions in the available timeframe. This resulted in a match between possible internships possibilities in the MPA master’s program, which consisted (partly) of the same cohort as the 2018 AGP students. The three follow-up research questions on loneliness were offered to students undertaking the five-month internships starting in February 2019 in the next action–research cycle. The internships were monitored by the CSL team and there were regular check-in moments. Given the length of the internships, an extra mid-way interview was added to better monitor the students’ progress.

There were also more specific questions raised during the second Meet & Match event on loneliness. For example, a social housing corporation was specifically interested in the effects of emotional and social aging in old people’s homes. The CSL team again assessed which academic programs could be related to this topic. After identifying them, there were discussions with lecturers to see whether there could be a match. A match was established with the second-year BSc course on Geriatrics and Aging, which was offered to 90 students. One of its learning goals is to conduct a survey with older people about an aging issue.

Potentially, the question on the effects of emotional and social aging in old people’s homes matched the identified course. In previous years, the students taking this course chose their own aging issue after a day of volunteering in a health-care facility without the involvement of a community partner. The coordinator was motivated to look for ways in which the student projects could address an external community partner’s wider concerns, and so increase the impact of the course. In an attempt to match the community needs to the course objectives, it was decided to provide the students with a pre-developed questionnaire so that they could focus on the data collection. This re-design was needed given the short timeframe of the course (8 weeks) and the learning goals that mainly looked at data analysis. The CSL team co-developed the questionnaire in close collaboration with the community partner and the course coordinator. The CSL team, with one of the CSOs, also monitored the distribution of the questionnaire in old people’s homes.

The students on this BSc course on Geriatrics made recommendations to the social housing corporation on how to deal with the residents’ needs and wishes in relation to the themes of emotional and social aging. The students identified needs in relation to better advertising social activities, organizing more diverse activities, making the common spaces more attractive. The collaborations with this housing corporation continued into 2019, involving other housing complexes and other target groups.

After addressing policy considerations and related follow-up questions in relation to loneliness and answering more specific questions such as older people’s housing needs. Two CSOs expressed a need to look at the social constructs of community building in order to prevent loneliness. Given the nature of this need, the CSL team identified bachelor’s and master’s Sociology programs as suitable. The team made contact with various lecturers, among others with the Sociology internship and thesis coordinator, who was interested in taking on the loneliness topic for internships as the objectives matched the community needs.

Four bachelor’s internships in the Faculty of Sociology focused on factors that promote or hinder community functioning and building and provided insights on the importance of active leadership, a safe meeting environment and setting specific meeting dates. The internships ran from April—June 2019. During this period, the CSL team and CSOs initiated meetings attended by three master’s students doing their internships (mentioned above) and the bachelor’s students to foster the exchange of knowledge among the students and with the community partners involved. One of the CSL team attended these meetings to monitor the interactions.

The master’s internships also provided insights into the needs of the lonely residents in Amsterdam New-West. The municipality and the one of the CSOs indicated that the next step would be to map these needs to the current social resources that they provided. To address this emerging need the CSL team assessed which programs could be linked to this research question and specifically which courses, preferably starting in September 2019. The preferred outcome would be an advisory report on the use of social resources.

The AGP course, which also kicked off the thematic approach, proved to be a good match as one of the learning goals is to provide such an advisory report. Twelve students from the September 2019 cohort on the AGP course built on the results of the interns and mapped the needs of lonely residents to the activities provided in the area. This provided the CSO with recommendations on how to better align their activities with these needs. While monitoring the course as it progressed, the CSL team noted that the community partner preferred not to interview lonely residents in the district, as they had already been subjected to various interviews during the earlier internships as well the first AGP course. The community partner involved expressed concerns about overburdening community members. In response, the CSL team suggested that the students use the results from the interviews conducted during the previous master’s internships to identify community needs. In order to adhere to the course objectives the students could interview members of the CSO in order to map the current social resources. This avoided overburdening community members with too many interviews while meeting the course objectives.

As part of the described action–research approach whereby courses were continually matched and monitored, the composition of the community partners varied. One community partner, namely the CSO VoorUit, was involved in all the projects, had worked in close collaboration with the CSL team, its extended network in the city district of Amsterdam New-West provided opportunities for connections with local communities. VoorUit was especially valuable in identifying community needs which the CSL team could then match to courses. To contribute to the monitoring of the loneliness theme, the CSL team employed a student assistant just after the first AGP course in 2018. The assistant could follow all the courses included in the loneliness theme and contribute to knowledge exchange and logistics. The student assistant contributed to creating an overview of the activities being conducted and the main outcomes achieved.

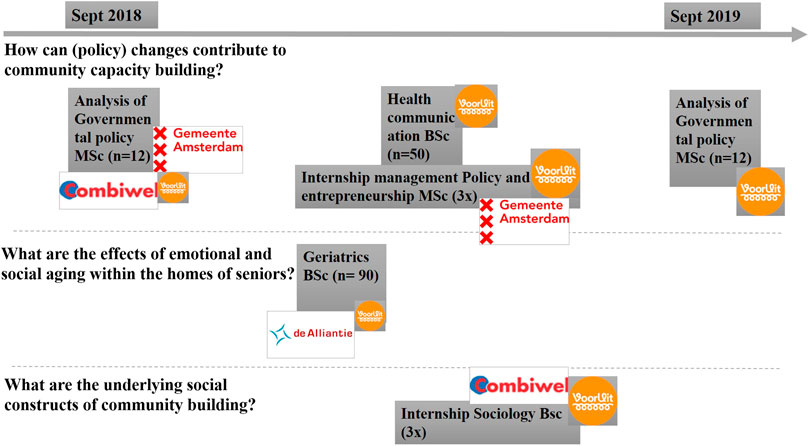

After a little more than a year since the second Meet & Match event hosted in June 2018, four courses (one including two students’ cohorts) and seven internships were included within this theme-based approach. The main outcomes of the CSL projects related to these courses were shared in presentations at the VU Amsterdam and disseminated in the form of scientific reports. At the presentations, representatives of the commissioning parties as well as community members were invited to the VU Amsterdam. Figure 2 shows a timeline of all the courses, internships and community partners that have contributed to addressing the problem of loneliness in Amsterdam New-West from September 2018 to October 2019. As already shown, courses and internships may run sequentially, building on each other’s results, or in parallel, addressing different research questions.

The results of the three master’s interns were also presented at a local event organized during the ‘Week of Loneliness’ in October 2019. This event was organized by two CSOs, The Hogeschool van Amsterdam, the municipality and the VU Amsterdam. Representatives of these stakeholders attended as well as students and local residents. At the event, students shared their results, which also provided a platform for local residents to share their stories with respect to loneliness. In this way, the event contributed to interesting conversations and gave rise to new partnerships and research topics. The VU Amsterdam, the Municipality of Amsterdam, and other community partners involved with the thematic approach also signed an agreement to continue devoting time and resources to address loneliness in the district of Amsterdam New-West. Thus, the event added to the continuity of the thematic approach.

Methods

As previously noted, the CSL team follows an action–research approach (Lewin, 1946) in developing the CSL thematic initiative, distinguishing between matching, monitoring and evaluation phases that also result in new activities (Figure 1). We described earlier the process of matching and monitoring student projects, consisting of courses or internship clusters to provide some background to how we developed the thematic approach in CSL, which we consider crucial in understanding its complexity. At the end of each student project, described in the previous section, the CSL team conducted evaluations with all the stakeholders in order to assess whether and how the thematic approach had contributed to addressing the issue of loneliness. We specifically enquired about the benefits and related considerations of a thematic CSL approach, research on which is ongoing. This article describes the first action–research spirals from the period of June 2018 to October 2019.

Data Collection

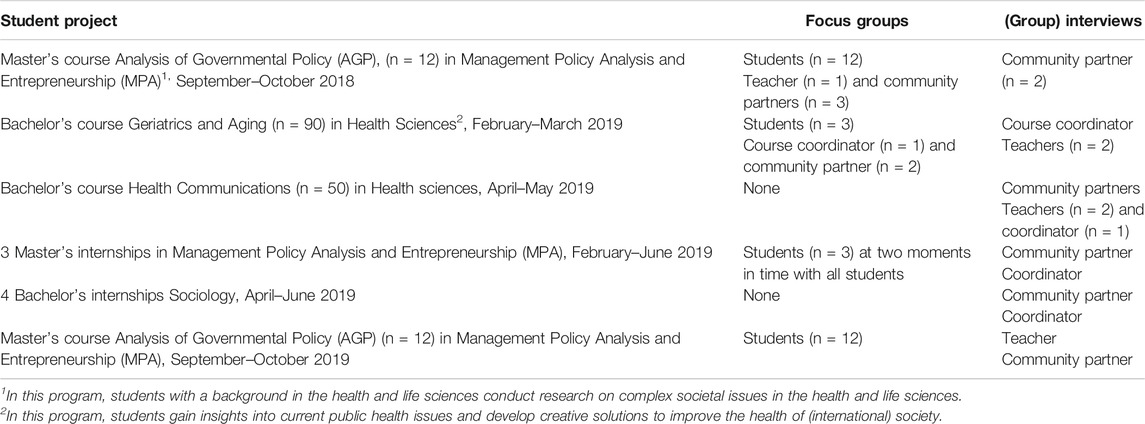

The current pilot study covered six student projects based in the MSc in Management Policy Analysis and Entrepreneurship, the BSc in Health and Life Sciences, and the BSc in Sociology, and two faculties (Faculty of Sciences and the Faculty of Social Sciences). From these student projects, four were drawn from courses and two were internship clusters (Figure 2). At the end of each student project, we reviewed the final reports and considered the main tangible outcomes as reported by the students to gain some insights into how the different projects addressed the issue of loneliness. We also conducted face-to-face, in-depth, semi-structured interviews or FGDs with the stakeholders—students, teachers and community partners. By including the perspective of all the stakeholders, we obtained a comprehensive understanding of phenomena, and thus increased the validity of our findings (triangulation of data). In total, 30 students, six members of commissioning parties (of which two were interviewed twice) and eight teachers/course coordinators were included in the data collection.

During the first two action–research spirals (involving the master’s course on AGP and the bachelor’s course on Geriatrics and Aging) FGDs were conducted with the coordinator/teacher and community partner. We noticed, however, that owing to power differentials among participants, some individuals might feel uncomfortable in this set-up to talk openly about their perceptions and assessment of the collaboration. For this reason, in both instances either the commissioner or course coordinator were also interviewed separately. In line with the action–research approach, we decided to adapt our approach to enable us to address our research question more accurately. From then on, to avoid power differentials among participants, FGDs were conducted to capture the students’ perspectives, and separate interviews were undertaken with teachers and community partners. The interviews and FGDs were conducted mainly in Dutch with the exception of the two AGP courses, which were conducted in English as they included non-Dutch-speaking students. Specifics of the various interviews and FGDs linked to each course or internship can be found in Table 1. We must acknowledge that the number of students who participated in the FGDs differed substantially for AGP, with 12 students, whereas only three students on the Geriatrics and Aging course participated. As participation was on voluntary basis, the CSL team found it harder to recruit bachelor’s students for the evaluations.

The research tools used in the interviews and FGDs followed a semi-structured design describing a topic list in relation to the context in which the course was set, the input, the process and the final product. The interview guide and the FGD script followed the same topic list, with the latter including additional elements to ensure that all participants could provide inputs on the discussion topics. For the current case study, the focus was on mainly the process and the product and specifically how a thematic approach might contribute to the process and the product, but also what benefits and considerations might arise in clustering multiple courses and internships to address one complex issue. When the participants were asked to describe the process, we included questions such as: What went well and what was challenging? With regard to the products, meaning the final reports as well as the learning experiences during the course, the participants were asked what they had learned, and whether and in what way they felt the product had added value to the community partners and community members involved.

Data Analysis

All interviews and FGDs were transcribed verbatim and analyzed by the first author. After analysis quotes were translated from Dutch into English. In the analysis here, only sections where teachers/course coordinators, community partners or students specifically referred to the loneliness theme were included for coding purposes, as we were specifically interested in the contributions, benefits and related considerations of the thematic approach (e.g., clustering multiple courses to address the issue of loneliness). We followed a thematic analysis approach based on open coding, meaning that the textual data were inductively coded and categorized in themes that are linked to the benefits of the thematic approach and related considerations. Initial codes linked to the benefits of the thematic approach considered starting up a project, more connections, more sustainability, greater motivation, and increased impact/deepening of knowledge. Codes related to possible drawbacks considered reduced freedom, repetition, overburdening target groups, and the need for greater investment. Within each category, quotes from different stakeholder groups were included. This initial coding was performed by the first author, supported by discussions with the second author on the codes and emerging themes.

In a second coding round we decided to consider the perspectives of the community partners separately from those of the teachers/course coordinators and students as this would provide more clarity and depth within the codes. This produced the structure as described in the results section. This round of coding was conducted by the first and second authors. When perspectives overlapped in the new coding structure, this is also reported in the results section.

Ethical Considerations

Participation in the study was on a voluntary basis. All parties signed an informed consent form before participating in the interviews or FGDs. Participants were told that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any stage if they wish to do so. Audio recordings and transcripts were safely stored. After transcription, the audio recordings were destroyed. All data transcripts have been anonymized. We completed an online ethics Self-Check form offered by the VU Amsterdam, consisting of 15 yes/no questions (Research ethics review, 2020). The Self-Check form confirmed that we did not require further evaluation by the Research Ethics Review Committee as participants signed an informed consent, no possible risks were posed, no vulnerable groups were interviewed, participants were not exposed to recruitment incentives or destressing material, no risks were posed to the researchers and finally participants were not deceived in any way and data was anonymized.

Results

In this section, we report on the evaluation phase of the action–research approach. We first reflect on how the thematic approach has contributed to addressing the issue of loneliness by considering the tangible outcomes of the different student projects in the pilot. Next, we look at how the thematic approach has contributed to addressing the issue of loneliness in Amsterdam New-West by considering the perspectives of the community partners involved in the project. Finally, we provide insights into the benefits and issues related to the thematic approach based on the experiences of the teachers, course coordinators and students.

Tangible Outcomes of Student Projects

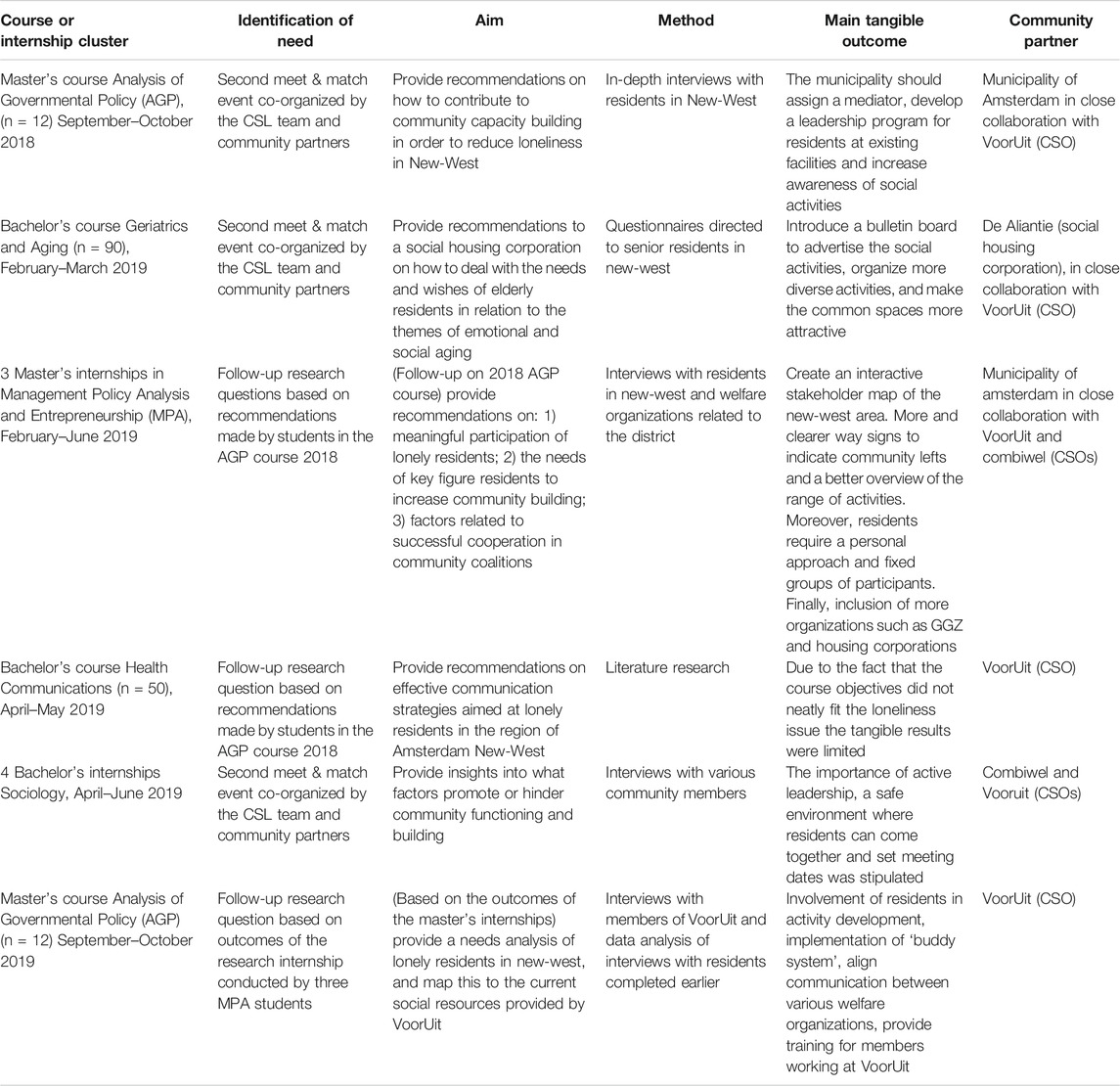

The student projects yielded various tangible outcomes that have contributed to addressing the issue of loneliness in Amsterdam New-West. These varied from recommendations concerning the needs of lonely residents in relation to increasing awareness, diversifying activities, and taking a more personal approach, to more structural advice with respect to the collaboration between the municipality and various CSOs. Table 2 shows the main tangible outcomes for each course or cluster of internships that contributed to addressing the issue of loneliness in Amsterdam New-West. Most of the outcomes are recommendations relevant to the commissioning parties. However, especially in relation to the various internships, it was also noted that the mere presence of the students for a substantial period of time had a positive and mediating effect on the communities, in particular on the people in direct contact with them.

Contribution of the Thematic Approach

The following sections present the contributions specifically related to clustering courses to address different aspects of a complex issue such as loneliness. More specifically, we consider how the thematic approach has contributed to addressing this issue in Amsterdam New-West by considering the perspectives of the community partners involved in the project.

Building New Networks

The first major attribute of the thematic approach community partners mentioned is that it assists in building new networks. Several community partners stated that, as a result of the first course (AGP 2018), various partners, specifically the Municipality and two CSOs, that would have otherwise been disconnected, started working together and exchanging ideas:

‘[another community partner] also wants to participate, so more parties are inspired by this [2018 AGP course] to actively participate within the same theme and to take action.’ (community partner).

A community member commented that there were benefits even before starting this first course. The Meet & Match events co-organized by the CSL team and other stakeholders appeared to be a valuable way to start new collaborations, as the following quote illustrates:

‘ …the meet and match was organized [Meet & Match events], a clear theme arose [loneliness]. Then people came together, and it became clear that such a theme is just so important and essential. So that various partners have been working on it together.’ (community partner)

Continuity

Community members noted that another benefit yielded by the thematic approach was that of continuity. One community partner expressed finding it offered so much added value that the loneliness topic was given significant and continuous prominence at the VU Amsterdam. This community partner noted that the municipality of Amsterdam, for instance, tends to change thematic interest for political reasons, as often a topic is very prominent on the political agenda, but only for one year. For instance, loneliness could easily be supplanted by another theme such as ‘more green’ in the city, and then money is reallocated to the new theme. For her, a sustainable partnership based on a multi-year commitment to this theme was most important:

‘Loneliness, that is not a theme that is just about to resolve itself. But if you can do it together, you can get much more sustainably on these kinds of slow questions that will always continue to demand attention in [an] ever new guise.’ (community partner)

Interestingly, it was not only community partners who expressed this need for continuity. Teachers and students who were part of a thematic approach became aware of this need. For instance, one of the course coordinators noted the need for continuity as the students are still learning and it is unrealistic to expect that they will hand in a product that can be directly applied. We should therefore provide follow-up opportunities based on the results.

It should be noted, however, that when multiple courses and or internships focus on the same theme, there is a possibility of overburdening specific target groups in the community. The program did take steps to avoid this. For example, the 2019 AGP students did not interview the community members who had already been interviewed by students and internships in 2018, but used the data collected by their colleagues the year before and focused on collecting their own primary data, which is an important learning objective of this course, by interviewing other relevant groups.

In relation to greater continuity, various partners (the VU Amsterdam among them) that had been involved in the CSL courses and internships as part of the loneliness theme signed a covenant in which they committed to continuously devote time and resources to address the issue of loneliness in the district of Amsterdam New-West. This covenant was signed at a local event organized during the ‘Week of Loneliness’ in October 2019. This event provided a platform for community members, partners and students to share their experiences, and also gave rise to new partnerships and new research topics. In that way the event in itself also contributed to continuity.

Deepening of Knowledge

The CSL team’s action–research approach made it possible, together with community partners, to identify new ideas and research questions from the outcomes of the CSL projects on the loneliness theme. These new ideas and questions were connected to follow-up courses and internships, contributing to continuity, as noted by two community partners. One community partner took it a step further, noting that continuity not only provided benefits when working with multiple courses and internships on one theme, but that these kinds of collaborations could also lead to more in-depth knowledge:

‘The continuity but also the deepening of knowledge, I really hope for that. I really hope that in ten years’ time we will say something different about what loneliness is and what helps, than that we now say after three reports.’ (community partner)

This continuity and resulting deepening of knowledge are not outcomes of the thematic approach that can be taken as a given. They require active and constant time and effort from the parties involved, particularly the CSL team at the VU Amsterdam. Two of the community partners noted that in order to really use the thematic approach, there is a need to invest time and commitment to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and increase impact:

‘But you should monitor it [the exchange between students and courses] more closely if you want to get the most out of it. [...] Ultimately, the effect is increased because it is more connected.’ (community partner)

To achieve this, members of the CSL team ensured that a connection between various partners and coordinators was established. The team had to identify potential partners, course coordinators, and align interests in and possibilities for collaborating. The CSL team members were also involved in aligning the various research questions, enabling various courses to build on each other’s results. In addition, the CSL team decided to assign a student assistant to the theme of loneliness to provide extra logistical support. This assistant followed all the courses and summarized the main findings for each course, and thus obtained an overview of the main outcomes and possible follow-up questions. Linking a student assistant to a specific theme was well received by the course coordinators, as it enabled them to reduce the workload of aligning the course objectives to the theme and gave more meaning to the course by streamlining knowledge. This is illustrated by this quote from a course coordinator:

‘[Name student assistant] was also able to think along about the content, which was also very nice.’ (course coordinator)

The possibility of getting additional support to establish CSL projects on the theme of loneliness and the prominent role played by the CSL team in this process were noted by teachers and course coordinators. This topic is described in the following section, which reviews the benefits and considerations of a thematic approach.

Benefits and Considerations of the Thematic Approach

In the following sections we provide insights into the benefits and related considerations of the thematic approach, based on the experiences of the teachers, course coordinators and students.

Collaborations

The thematic approach encouraged collaborations both among community partners, and also between faculties and among students. For instance, the approach created new connections between the Faculty of Science and the Faculty of Social Sciences. The members of each faculty are now discussing the possibility of a joint publication on assessing impact of community-based interventions. One internship coordinator noted that these collaborations have much added value, making it possible to rely on and learn from each other as faculty members. The theme also contributed to collaboration among students, which community partners perceived as valuable by because they could exchange information and learn from each other, as the following quote illustrates:

‘That it was a group [of students within the internships] really has added value. So for the sequel I would like to steer towards having several students working on a theme.’ (community partner)

One internship coordinator suggested that we could have taken these networks one step further by including students from vocational education also working on this subject. He emphasized the need for an additional, more practical, approach:

‘How can you combine theory on one side with practice [hinting at vocational education]…? You have to be in both areas but then you need a team, you cannot do that on your own.’ (internship coordinator)

Awareness of Community and Student Development

Another benefit yielded by thematic approach was the positive effect on students’ knowledge of community issues and ability to identify and understand community needs. In this process, students in the 2018 AGP cohort also developed competencies related to ethical reasoning. The interaction with community members and partners, and an increased awareness of loneliness as a complex problem, have enabled them to realize that it would be unethical to just step in, do their research for four weeks and then leave. They found this especially troubling given the fact that the lonely residents already often have issues of trust and feel neglected. Just doing their research and not following up could do more harm than good. A conversation that took place in one FGD illustrates this point:

‘One of things that I find a little bit, ethically troubling I guess [...] these people have trust issues, things have been promised that were not kept. Or, you know, they had a contact person, but that switched five times in a year.’ (2018 AGP student)

Students noted that for such a project to be ethically valid, there should be some kind of follow-up and continuity. They recognized the importance of continuity, which the community partners also perceived as necessary and beneficial. A community partner involved in the 2018 APG course mentioned the importance of informing students about the importance of continuity. In their experience, the students were unclear about what was happening with their results, and expressed concerns in relation to continuity. This lack of communication was confirmed by one of the students:

‘At AGP [course] it was not clear what would be done after we were finished.’ (2018 AGP student/internship student).

Moreover, in relation to building new and larger networks, one community partner indicated that the wide diversity of stakeholders involved in one project adds a layer of difficulty for the students, because they have to take account of all the different perspectives, values and ideas. He added that this added difficulty might well contribute to students’ development as it accurately reflects real-world challenges that students will need to learn to address. This enhanced student development was confirmed by an internship coordinator:

‘[when working within a theme with multiple partners] students are more likely to come into contact with contradictions and they have to find a way to deal with this and that is the reality they come into contact with.’ (internship coordinator)

However, there appears to be a trade-off between community involvement with the risk of overburdening the community, and how deeply students are able to relate to the relevant group, perhaps hampering the extent to which they can build awareness of community issues. For instance, as noted previously, the 2019 AGP students could not interview the community members who had already been interviewed by the internships and 2018 AGP to limit the possibility of overburdening specific community groups. Instead, the data gathered in the internship interviews was re-used and re-analyzed. Although the learning objectives of the course were achieved by interviewing members of the partner organization, this decision affected the way in which students could relate to the target group, as the following quote illustrates:

‘I thought that was a pity, because we also looked at the residents, but we have not been in contact with them [...] I sometimes found it difficult to imagine what makes them so unapproachable.’ (2019 AGP student)

Motivation

Greater motivation was a benefit of the thematic approach mentioned by a teacher, a coordinator and several students involved in the loneliness theme. The reasons for this motivation differed. One teacher noted that the idea of contributing to a larger goal (solving the complex issue of loneliness) increased her motivation:

‘But also, that the whole workgroup worked together on a larger goal [hinting towards loneliness]—I liked that the most.’ (teacher)

One of the coordinators noted that because the CSL team was already in contact with the community partner, there was more motivation to join the theme as it would not add much to the existing workload while still enabling her to integrate real cases into the course. An AGP student from the 2019 cohort noted that the event at the ‘Week of Loneliness’ where master’s students presented their internship results back to the community, was a real eye opener. She said that it became clear to her how the cohort was now building on the results of these master’s students and this increased her motivation as she felt that she was making a valuable contribution that could be picked up again by other students.

It should be noted that aspects of the thematic approach also reduced motivation for certain student groups. For example, some students indicated too much potential overlap or repetition of the subject in different courses. Specifically, students from the courses on geriatrics and health communications indicated that they already had one or sometimes two courses dealing with elderly people and/or loneliness and would have preferred to touch on more diverse topics within their bachelor’s program. Two teachers from the health communications course commented that whether motivation increased or decreased differed greatly depending on the individual student: some students found loneliness a very intriguing subject and were happy to have another course on this theme, whereas others were fed up with the topic after one course. In general, the teachers agreed that it is important to discuss various topics throughout the bachelor’s program, but to achieve more depth and a greater sense of ownership, it could be interesting for some themes to re-emerge, althoughperhaps not in several subsequent courses.

Sense of Ownership

Most students also showed greater responsibility for community projects. One student from the 2018 AGP cohort indicated that he was not particularly interested in loneliness until the topic came up in the course:

‘I was not really interested in loneliness specifically, but now since I am, yes, it definitely became part of me. I was thinking of maybe doing an internship within this area.’ (AGP student)

Indeed, three master’s students chose to further engage in the topic of loneliness in their internships. Interestingly, as the courses or internships progressed, students seemed to develop a sense of ownership of the theme, feeling in some way responsible to contribute to this complicated, widespread problem. The thematic approach offers the opportunity to do so by offering internships or other courses that consider the same theme.

In one course that was part of the thematic approach, some students reported that they felt a drop in their sense of ownership. This was because in previous years, students were free to choose a topic after one day of volunteering in a healthcare facility. In the course assignment, they then switched to a more narrowly focused question arising in the second Meet & Match event. Some students perceived this as having less to contribute themselves and so reduced their sense of ownership. Two students from the geriatrics course indicated that they would have preferred to choose their own research subject, as the following quote illustrates:

‘It is just more fun if you can think of a topic yourself, and since you can ask your own questions, it feels much more like you do the research yourself.’ (geriatrics student)

Reducing the Threshold for Adopting CSL

It was noted by teachers and coordinators that CSL usually demands an increased investment of time. Being part of the theme contributed to alleviating this problem. Two coordinators noted that the great advantage of the thematic approach is in reducing some of this investment of time as the collaboration with the partners is often already established and research topics have been defined by or together with the CSL team.

Although the threshold for adopting CSL can be reduced by being part of a thematic approach, it is still necessary to ensure an alignment between the CSL and the course objectives, and that adequate guidance to students is offered in this process. For instance, the course coordinators of the health communications course were initially happy to engage in CSL, especially because the questions had already been formulated and a collaboration between the partners and the CSL team established. During the course, however, they expressed their view that the topic of loneliness did not neatly fit with the course format. Originally, the students had to start with a health problem, and the course coordinators did not regard loneliness as a health problem. The teachers therefore decided to give students the opportunity to choose any health problem that might coincide with loneliness and make their health communication recommendations on this basis. As a consequence, one teacher noted that students found ways to link any disease to the issue of loneliness, making the results perhaps less valuable. This was also confirmed by the community partner involved.

Need for Interdisciplinary Bridges

Complex problems such as loneliness should be addressed from multiple perspectives. However, in our thematic approach to address loneliness, a perceived need for building interdisciplinary bridges remained. One teacher noted that the multi- or interdisciplinary component of the thematic approach is not sufficiently rewarded in universities’ current academic structures. In the following quote, one coordinator is hinting at the need for interdisciplinary, although this might not be well received by one’s peers:

‘Teachers work in a particular structure and if you just use the academic structure you can score very high; you can get promoted and you get praise after praise. But when you start messing around in the margins [hinting towards interdisciplinary work] then you are perceived as messing around and you stop putting yourself forward.’ (internship coordinator)

The coordinator went on to add that for many faculty members this is a reason not to engage in interdisciplinary education, but that reviewing academic structures and supporting collaborative practices at the institutional level could provide faculty incentives. Interestingly, the thematic approach, led by the CSL team and strengthened by a student assistant, appears to be able to establish the required linkages or bridges. In this way the CSL team creates a bridge between disciplines through the thematic approach while not imposing too much on the established curriculum.

Discussion

This article has described how a thematic approach to CSL was initiated at the VU Amsterdam, starting from the needs of a local community. To do so, the CSL team co-organized with social partners and facilitated two Meet & Match events in and with the community, by involving local residents, community partners, teachers, students and researchers from the VU Amsterdam. At the first event the theme of loneliness arose on the basis of community needs as an urgent and complex issue. In previous studies considering multi or interdisciplinary CSL, the collaborations often start with courses (Falk et al., 2012; Norton et al., 2018) or campus-initiated programs (Harrison et al, 2013), making our community-centered theme-based CSL approach perhaps unique. Following an action–research approach, the CSL team kept linking the specific issues arising from the second Meet & Match event, which was focused on loneliness specifically, and new ideas and knowledge generated during ongoing community-based activities to other courses and internships. Action–research projects can produce both theoretical and practical knowledge in a way that can inform future action (Reason and Bradbury, 2005). Our focus was to design a research process that is fluid, dynamic and flexible, and allows for the use of the knowledge being produced.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multidisciplinary theme-based initiative that started from and was completely built around community needs. As a result, by October 2019, a thematic approach comprised four courses (one including two student cohorts), seven internships and involved four different community partners and several residents of Amsterdam New-West. Our results show that the thematic CSL approach has contributed to addressing the issue of loneliness in this district. Over and above the more tangible outcomes as presented in Table 2, the approach assists in building new community networks. Moreover, it appears that the thematic approach has the potential to ensure project continuity and therefore deeper knowledge, which community partners and coordinators perceived as both positive and crucial. Teachers, course coordinators and students noted various benefits conferred by the thematic CSL approach. It has the potential to encourage new collaborations among students and faculty. Moreover, the thematic approach mitigates the increased workload related to CSL projects for course coordinators, because the collaboration with the partners is often already established and research questions are often (partly) formulated. Finally, the theme can assist in increasing student development, motivation and sense of ownership.

This is in line with findings from previous studies on multi- and interdisciplinary CSL. Indeed, such projects benefited from the continued presence of faculty (Falk et al., 2012) and gained insights as a result of new collaborations, leading to better contextualization of the relevant problems (Norton et al., 2018). It was also noted that specifically linking various courses stimulates new collaborations (Cross and Eckberg, 2015) and so diversifies voices, which leads to better consideration of the issue both from the from faculty perspective (Harrison et al, 2013) as well as from the student perspective (Coleman et al, 2017).

In the current case study, the community partners emphasized the benefits of broader collaborations as result of the thematic approach, thereby diversifying collaborations and voices and adding to the project’s value (Falk et al., 2012; Lambert-Pennington et al, 2011; Norton et al., 2018). The community partners involved in the case study noted that these diverse collaborations create a better representation of the real world and helped stimulate the students’ professional development. Norton et al. (2018), who describe a project in which multiple CSL courses contributed to an urban regional planning program, also note that part of the aim, and of students’ learning process, is realizing and perhaps even addressing these ambiguities. Moreover, Norton et al. (2018) found that the students tend to have a mediating effect on various partners, resulting in improved and diversified interaction, in particular with community partners. More specifically, they note that community partners involved tend to be more probing, respectful, and thoughtful about each other thanks to the student involvement (Norton et al., 2018). Other findings of the case study are in line with those of Wiese and Sherman (2011), who describe an experiential service-learning project that combined environmental studies and marketing courses over a two-year period. For example, the case study revealed that faculty members appreciate the more satisfying teaching experience as they can contribute to a larger goal (Wiese and Sherman 2011).

It should be noted, however, that the thematic approach also raised certain issues to be addressed. For example, the case study revealed that some students prefer to have a theme that re-emerges throughout the program, because it further develops their knowledge on the topic, whereas other students prefer a wider range of topics and the freedom to choose their own (Roman, 2015; Werner et al, 2002). To accommodate both preferences and needs, internships could offer students the choice about whether to further engage in the topic (Johnston et al, 2004). The case study showed that this seems a promising approach as it also increases a sense of ownership. Another important consideration, which is related to project continuity, is that of making too many demands on specific community groups. This can be avoided by re-using and re-analyzing existing data, as was done with the 2019 AGP course. A consideration in doing so, however, is that students might be less able to relate to the target groups. In such instances, one should therefore carefully consider student development.

The VU Amsterdam states in its Mission that ‘students and staff have a deep connection with one another while being fully engaged with society as a whole (p. 6), and its vision states that the VU Amsterdam ‘want[s] the world to know about the societal impact of [its] educational and research activities’ (p. 54). We believe that our theme-based initiative, completely built on community-defined needs, has made a direct contribution towards putting this mission into practice. Moreover, this bottom-up approach offers greater benefits compared to previous studies on course-based multi- and interdisciplinary CSL. We therefore argue that this approach can be a valuable way for universities to keep faith with their third mission, because it especially considers community needs. Previous studies, particularly in relation to institutionalizing the third mission, have made the criticism that this process is usually considered from the institutional perspective (Furco, 2007) and lacks a more community-based view that emphasizes reciprocity (Curwood et al., 2011; Sweatman and Warner, 2020).

In order to develop future-proof forms of education, CSL is intended to be implemented throughout the VU Amsterdam, as stated in its Strategic Plan 2020–2025. So far our thematic approach has contributed to this aim. This article focuses on the issue of loneliness, which was identified as an urgent and complex problem by community members as well as by local CSOs in Amsterdam New-West. We argue, however, that the thematic approach could also be applied to other complex problems such as sustainability or inclusive mobility and are currently experimenting with ways to address such issues. Interestingly, clustering various courses to address complex societal issues makes it possible for faculties to do this while also respecting the integrity of their own discipline, allowing for multi- and interdisciplinary collaborations while not imposing too much on the established curriculum. These attributes make the thematic CSL approach a valuable stepping stone towards advancing CSL in universities, and so contribute to fulfilling their third mission.

Limitations of the Case Study and Suggestions for Future Research

In this article, we included data collected immediately after the CSL experience. While this allowed us to obtain rich data about the collaboration process that might otherwise have been lost, it was probably too soon to obtain more insights on the outcomes for students and community partners. Future research should also include data collected at different stages to assess the mid–and long-term effects of the CSL activities conducted as part of the thematic approach. The action–research approach easily allows for extra assessment, as occurred in the MPA internships, as the courses are already being monitored.

In addition, it should be acknowledged that, in relation to the focus groups conducted, the divergent number of students that participated might have had an impact on the quality of the results. We noticed that it was much more difficult to motivate the bachelor students to participate in focus groups. For example, only three bachelor students participated in the focus group of the geriatrics course (which consisted of 90 students in total). The bachelor students that did participate were in general more critical compared to the master students. We should therefore acknowledge that the data, reported at least when considered from the student perspective, might have been slightly optimistic.

In addition, as was noted in the section of the results, most of the tangible outcomes of the students’ projects were recommendations and might have lacked direct application purposes (Table 2). A sound problem analysis can make an important initial contribution to resolving complex problems (Alford and Head, 2017). The next step would be to put these recommendations into practice, for example by designing new means of communication or developing specific training programs. In should be noted, however, that rather than the product per se it might be even more important to consider the process in assessing the contribution of CSL activities, as was also noted by Clifford (2017) who emphasizes the importance of considering the constructs of process and solidarity, rather than simply focusing on the products and reciprocity. In addition, it might be interesting to monitor the application of the recommendations and undertake evaluations based on this process. Some more applied projects might fit better with higher vocational education. Therefore, as one of the internship coordinators in the case study suggested, collaborations between universities and higher vocational training should be further explored. At the time of writing, there is continuing research into thematic approaches and on ways to include vocational education.

Finally, the thematic approach presented in this article included only a limited number of programs (MSc MPA, BSc Health and Life Sciences, BSc Sociology), which are hosted by only two faculties at the VU Amsterdam, namely the Faculty of Sciences and the Faculty of Social Sciences. This was a limitation in terms of the kind of issues and questions that could be addressed in the CSL activities. We aim to include more disciplines and faculties in order to continue addressing loneliness and other complex problems. Beyond better contextualization of the issue, increasing the range of educational programs involved in the thematic approach could also be beneficial in reducing the likelihood of dealing with the same complex issue repeatedly in one program. The inclusion of multiple faculties will undoubtedly raise new opportunities and concerns to be addressed in future research activities.

Concluding Remarks

It appears that the thematic approach, where multiple courses and internships from various programs and different faculties were clustered to address one thematic issue, might offer a valuable way to contribute to addressing complex contemporary problems. As the research questions are built entirely around the community needs, the approach requires support to facilitate matching and possibly (re) design and adaptation of the courses. This requires an intermediary, in this case the CSL team. In our experience, the thematic approach can be a possible means to integrate a range of disciplines, while not imposing too much on the established academic curriculum. In this way, the thematic approach could serve as a valuable stepping stone towards advancing CSL in universities, helping them to fulfill their third mission.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Both EU and MZ have contributed to reviewing and writing the current paper. EU has also been involved in the analysis process. We thank Deborah Eade for english edditing of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Goldschmeding Foundation and Porticus, project Broader Mind for Students.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the community partners, students, the student assistant and course coordinators/teachers for their input in relation to their experience in developing the thematic approach. Their insights were critical to our research. Our gratitude goes especially to the course coordinators who checked and reviewed the article.

References

Alford, J., and Head, B. W. (2017). Wicked and less wicked problems: a typology and a contingency framework. Policy and Society. 36 3, 397-413. doi:10.1080/14494035.2017.1361634

P. Aramburuzabala, L. McIlrath, and H. Opazo (2019). in Embedding service learning in European higher education: developing a culture of civic engagement. 1st Edn(London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 268.

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A service-learning curriculum for faculty Michigan. J. of Comm. Serv. Learn. 2 (1), 112–122.

Bringle, R. G. (2017). Hybrid high-impact pedagogies: integrating service-learning with three other high-impact pedagogies Michigan. J. of Comm. Serv. Learn. 24 1, 49–63, doi:10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0024.105

Celio, C. I., Durlak, J., and Dymnicki, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. J. of Experi. Edu. 34 (2), 164–181. doi:10.1177/105382591103400205

Clifford, J. (2017). Talking about Service-Learning: Product or Process? Reciprocity or Solidarity? J. Exp. Educ. 21 (4), 1–13.

Coleman, K., Murdoch, J., Rayback, S., Seidl, A., and Wallin, K. (2017). Students’ understanding of sustainability and climate change across linked service-learning courses. J. Geosci. Educ. 65 (2), 158–167. doi:10.5408/16-168.1

Compagnucci, L., and Spigarelli, F. (2020). The third mission of the university: a systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 161, 120284. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120284

Conway, J. M., Amel, E. L., and Gerwien, D. P. (2009). Teaching and learning in the social context: A meta-analysis of service learning’s effects on academic, personal, social, and citizenship outcomes. Teach. Psychol. 36 (4), 233–245. doi:10.1080/00986280903172969

Cross, A., and Eckberg, D. A. (2015). Jigsaw research communities: coordinating research and service across multiple courses to serve a single community partner. J. of Pu. Scholar. in Hig. Edu. 5, 143–158.

Curwood, S. E., Munger, F., Mitchell, T., Mackeigan, M., and Farrar, A. (2011). Building effective community-university partnerships: are universities truly ready? Mich. J. Comm. Serv. Learn. 7 2, 15–26.

O. Delano-Oriaran, M. W. Penick-Parks, and S. Fondrie (2015). in The SAGE sourcebook of service-learning and civic engagement. California, CA: SAGE Publications.

Falk, A., Durington, M., and Lankford, E. (2012). Engaging sharp-leadenhall: an interdisciplinary faculty collaboration in service-learning. J. of Pub. Scholar. in High. Edu. 2, 31–46.

Fitzgerald, H. E., Bruns, K., Sonka, S. T., Furco, A., and Swanson, L. (2012). The centrality of engagement in higher education. J. of High. Edu Out. Engage. 16 3, 7–28.

Folgueiras, P., Aramburuzabala, P., Opazo, H., Mugarra, A., and Ruiz, A. (2020). Service-learning: a survey of experiences in Spain. Educ. Citizen Soc. Justice. 15 (2), 162–180. doi:10.1177/1746197918803857

Furco, A. (2007). Institutionalising service-leaming in higher education. High Educ. Chem. Eng.: Int. Perspect. chapter 6, 65–82.

Gelmon, S., Holland, B., Driscoll, A., Spring, A., and Kerrigan, S. (2001). Assessing service-learning and civic engagement: Principles and techniques. Rhode Island, RI: Campus Compact.

Harrison, B., Nelson, C., and Stroink, M. (2013). Being in community: a food security themed approach to public scholarship. J. of Pub. Scholar. in High. Edu. 3, 91–110.

Huang, G., and London, J. K. (2016). Mapping in and out of “messes”: an adaptive, participatory, and transdisciplinary approach to assessing cumulative environmental justice impacts. Landsc. Urban Plann. 154, 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.02.014

Johnston, F. E., Harkavy, I., Barg, F., Gerber, D., and Rulf, J. (2004). The urban nutrition initiative: bringing academically-based community service to the university of Pennsylvania’s department of anthropology. Mich. J. of Comm. Serv. Learn., 10 3, 100–106.

Koryakina, T., Sarrico, C. S., and Teixeira, P. N. (2015). Third mission activities: university managers’ perceptions on existing barriers. Eur. J. High Educ.5 3, 3–15. 10.1080/21568235.2015.1044544

Lambert-Pennington, K., Reardon, K. M., and Robinson, K. S. (2011). Revitalizing south memphis through an interdisciplinary community-university development partnership. Mich. J. of Comm. Serv. Learn. 17, 59–70.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. J. Soc. Issues, 17 (4). doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

Norton, R. K., Gerber, E. R., Fontaine, P., Hohner, G., and Koman, P. D. (2018). The Promise and Challenge of Integrating Multidisciplinary and Civically Engaged Learning. J. of Plan. Edu. and Res. doi:10.1177/0739456X18803435

Pribbenow, D. A. (2005). The impact of service-learning pedagogy on faculty teaching and learning. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn., 11 (2), 25–38.

Ramley, J. A. (2014). The changing role of higher education: learning to deal with wicked problems. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 18 (3), 7–22.

Reason, P., and Bradbury, H. (2005). in Handbook of action research: concise. Paperback Edn. California, CA: Sage.

Research ethics review (2020). Available at:https://fsw.vu.nl/en/research/research-ethics-review/index.aspx. (Accessed December 11, 2020).

Roman, A. V. (2015). Reflections on designing a MPA service-learning component: lessons learned. J. Hisp. High Educ., 14 (4), 355–376. Available at: https://www.vu.nl/en/Images/VU-instellingsplan-EN_tcm270-944662.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2015).

Sandy, M., and Holland, B. A. (2006). Different worlds and common ground: community partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13 (1), 30–43.

Sweatman, M., and Warner, A. (2020). A model for understanding the processes, characteristics, and the community-valued development outcomes of community-university partnerships. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 26 (1), 265–287. doi:10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0026.115

Tijsma, G., Hilverda, F., Scheffelaar, A., Alders, S., Schoonmade, L., Blignaut, N., and Zweekhorst, M. (2020). Becoming productive 21st century citizens: a systematic review uncovering design principles for integrating community service learning into higher education courses. Educ. res. 1-24. 390-413. doi:10.1080/00131881.2020.1836987

Tryon, E., and Ross, J. A. (2012). A community-university exchange project modeled after europe’s science shops. J. of high. edu. outr. and engage. 16 (2), 197–211.

Vernon, A., and Foster, L. (2002). Community agency perspectives in higher education service-learning and volunteerism. Serv-learn.through a multidiscip. lens. 2, 153–175.

VU Amsterdam’s Educational Vision (2018). Available at:https://www.vu.nl/en/Images/Onderwijsvisie_oktober_2018_Engels_tcm270-901390.pdf (Accessed December 10, 2020).

Warren, J. L. (2012). Does service-learning increase student learning? a meta-analysis. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 18 (2), 56–61.

Werner, C. M., Voce, R., Openshaw, K. G., and Simons, M. (2002). Designing service–learning to empower students and community: Jackson elementary builds a nature study center. J. of soc iss. 58 (3), 557–579. 10.1111/1540-4560.00276

Wiese, N. M., and Sherman, D. J. (2011). Integrating marketing and environmental studies through an interdisciplinary, experiential, service-learning approach. J. of mark. edu.33141–56.

Williams, S. E., and Braun, B. (2019). Loneliness and social isolation–a private problem, a public issue. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 111 (1), 30–43. doi:10.14307/JFCS111.1.7

Yorio, P. L., and Ye, F. (2012). A meta-analysis on the effects of service-learning on the social, personal, and cognitive outcomes of learning. Acad. of manage. learn. and edu. 11 (1), 9–27. doi:10.1177/0273475310389154

Keywords: community service learning, third mission, complex societal problems, reciprocity, action research, thematic approach, multidisciplinary, loneliness

Citation: Tijsma G, Urias E and Zweekhorst M (2021) A Thematic Approach to Realize Multidisciplinary Community Service-Learning Education to Address Complex Societal Problems: A-Win-Win-Win Situation?. Front. Educ. 5:617380. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.617380

Received: 14 October 2020; Accepted: 21 December 2020;

Published: 11 February 2021.

Edited by:

Miguel A. Santos Rego, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Isabel Menezes, University of Porto, PortugalLluísís Brage, University of the Balearic Islands, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Tijsma, Urias and Zweekhorst. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geertje Tijsma, g.tijsma@vu.nl

Geertje Tijsma

Geertje Tijsma Eduardo Urias

Eduardo Urias Marjolein Zweekhorst

Marjolein Zweekhorst