Measuring Privileged Identity in Educational Environments: Development and Validation of the Privileged Identity Exploration Scale

- 1Department of Educational Policy and Leadership Studies, College of Education, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States

- 2Department of Student Affairs in Higher Education, College of Education and Communications, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA, United States

- 3Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, School of Education and Human Sciences, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

- 4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5CU Engage, School of Education, University of Colorado–Boulder, Boulder, CO, United States

- 6Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, School of Education, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, United States

The present study describes the development and validation of an instrument to measure defensive reactions individuals display in difficult dialogues while exploring privileged identities and interacting across difference. The increased focus on difficult dialogues when exploring privileged social identities in educational environments points to a need for the Privileged Identity Exploration Scale (PIE-S). The Privileged Identity Exploration Model (PIE) (Watt, College Student Affairs Journal., 2007, 26, 114–126; Watt et al., Counselor Education and Supervision., 2009, 49, 86–105) identifies eight defensive reactions. Using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, we identified and confirmed four constructs of privileged identity exploration that students exhibit when interacting across social differences, the PIE Scale (PIE-S). We provide a brief overview of the development of the PIE-S, as well as future directions for research and applications to training and facilitation in various educational settings.

Introduction

Higher education and student affairs professionals coordinate and implement programs with attempts to foster constructive social interactions (Torres et al., 2012; Watt, 2012). These experiences afford students the opportunity to recognize and understand the social and privileged identities that may exist within themselves and how these identities inform interactions with difference. Privileged identities are socially constructed identities linked to historically to aspects of social or political advantages in a society (Case et al., 2012). Privileged identities might include any socially constructed identity that has advantages, for instance, racial (White), sexual (Heterosexual), gender (cis-gender Male), religious (Christian), and/or ability (Able-bodied) identities. As students learn about their social identities and positionality, they experience dissonance as they engage others across difference (race, ideology, sexual identities, etc.), which can often turn an educational space (classrooms, workshops, trainings, diversity experiences) into a hostile learning environment. This study describes the development and validation of an instrument to measure defensive reactions individuals display in difficult dialogues while exploring privileged identities and interacting across difference.

Educators who are effective at navigating hostile environments can guide and support students’ development in growth-producing ways. However, it is often challenging to measure the range of defense reactions students might display while engaged in controversial dialogue. It is difficult to anticipate these reactions, which leaves educators without the ability to devise the best strategies to guide students through these difficult dialogues in ways that will support their development. Furthermore, given the increased number of students from non-dominant groups attending predominantly White institutions (Fischer, 2007; Omi and Winant, 2014) and the number of White individuals going into the K-16 education profession (Kayes, 2006), educators are having cross-racial discussions about how to dismantle Whiteness and racial injustice to improve the multicultural competency of helping professionals (Watt et al., 2009; Linley, 2017; Martinez-Cola et al., 2018). Recent sociopolitical events have also amplified that there is a general disregard and lack of awareness among students for how they see themselves in relation to others who are different from them. In light of these polarizing viewpoints, there is a need to train individuals and organizations on how to dialogue productively so that they can work together to address complex social problems. Learning more about the various defensive reactions that can arise can help educators to devise better strategies for facilitation that supports creating environments that nurture student development.

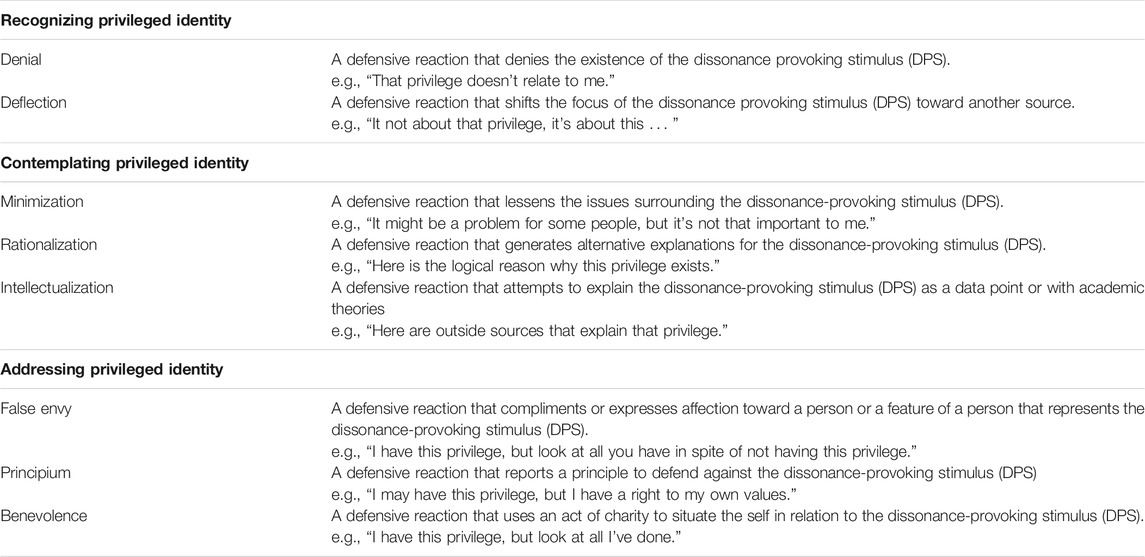

The Privileged Identity Exploration (PIE) model (Watt, 2007; Watt, 2015) provides a framework that educators can use to identify how individuals express defensiveness in reaction to difficult classroom dialogues about racism, sexism, homophobia, and ableism. The PIE model emerged from a qualitative study conducted in 2007 using Consensual Qualitative Methods (CQR) (Watt, 2007; Watt et al., 2009). The preliminary investigation included analyzing data from 27 personal narratives and reactions papers of nine White female counselor trainees; the sample was representative of the counselor trainees at the predominantly White institution in which the study was conducted. The study revealed a pattern of eight defensive reactions associated with behaviors that individuals display when engaging in difficult dialogues about social justice issues and/or circumstances that brings about an awareness of one’s privilege identity; with a specific focus on White privilege identity. The eight defensive reactions in the PIE model codify observable defenses that arise in individuals when they are introduced to a dissonance-provoking stimulus (DPS). The eight defenses identified in the PIE Model are characterized into three groups: recognizing (denial and deflection), contemplating (minimization, rationalization, and intellectualization), and addressing (false envy, principium, and benevolence) privileged identity. Table 1 provides a description of each defense. A defensive reaction occurs when a person confronts “dissimilar opinions, experiences, ideologies, epistemologies and/or constructions of reality about self, society, and/or identity” (Watt, 2015, p. 41). The dissonance is animated by fear (afraid to go deeper) or entitlement (should not have to go deeper), which creates disequilibrium.

TABLE 1. Description of privileged identity exploration model constructs with associated defenses (Watt, 2015).

While Watt et al. (2009) initial study involved uncovering defensive reactions to singular identities (e.g., race), the present study expands upon that research to include an intersectional lens that acknowledges the reality of possessing multiple, concurrent, privileged, and oppressed identities when responding to DPS. We explore the relationship between a subset of social identity characteristics (race, gender) on defensive reactions to triangulate findings from previous qualitative work on PIE. Further, the present study provides emerging quantitative support for the framework. We describe the development and validation of the Privileged Identity Exploration Scale (PIE-S) as a tool and framework to measure students’ defensive reactions when exploring their privileged identity. The results of this work are discussed in relation to the various ways researchers and educators can use the PIE-S instrument and PIE model to understand how individuals enter difficult dialogues in multicultural classroom spaces.

Theoretical Foundations

Cognitive dissonance is a common occurrence in multicultural courses as people engage with ideas that challenge their worldviews and cause them mental discomfort (Assaf and Dooley, 2006; Boatright-Horowitz et al., 2012; Chan and Treacy, 1996; Watt, 2015). When individuals feel as if their prior beliefs are threatened and their voice is being silenced, they retreat to traditional thinking and practices (Assaf and Dooley, 2006). Acts of resistance to multicultural course content may include open defiance, but more often takes the form of passive resistance. According to Hill (2009), passive resistance may appear as “marginal cooperation, lack of involvement, and excuse making when asked to carry out diversity policies” (p. 39).

Some studies of resistance to multicultural courses have looked at individual differences to explain why some individuals are able to become advocates of multicultural values while others resort to defensive actions. Hill-Jackson et al. (2007) described five dispositions in the multicultural classroom to demonstrate a range of attitudes and perspectives that contribute to acceptance or resistance of course concepts. They point to low cognitive complexity, limited worldview, lack of intercultural sensitivity, low self-efficacy, and ethical deficiency as leading to resistance in individual students. Other studies examine resistance as a positive outcome of difficult subject matter and not a description of a particular kind of student (Chan and Treacy, 1996), noting that resistance demonstrates a wrestling with complex concepts, thus opening up possibilities for dialogue (Abowitz, 2000). In this way, resistance is a normal response people have when introduced to a complex concept; it is human to first resist the idea and protect oneself from it (Harmon-Jones and Mills, 2019). People also want to resolve the resistance (Festinger, 1957) and defensive reactions are strategies one uses when faced with a complexity or a conflict. Defenses protect one from a reality, a new and/or different way of seeing the world. In interacting with others, these defensive reactions animate the resistance and lead to tensions that can derail productive dialogue (Watt, 2015).

This framing of defensive reactions as normal and potentially productive is important, as it shifts the responsibility of dealing with dissonance from the individual alone to the facilitator and the classroom community. Chan and Treacy (1996) describe multiculturalism as potentially transformative, as we look at systems of power that decenter us from our limited worldview and fundamental beliefs. In order to become transformative, however, individuals need structured environments to risk potential change and opportunities to explore and question without pressure to adopt certain beliefs or principles. Jaekel (2016) concurs with this need to help students develop and move beyond resistance and recommends doing so in part by holding institutions and leaders accountable to the same examination of power that we ask students to perform regarding their privileged identities.

Lacking in this literature are measures that capture how individuals, in particular students, react in regard to their privileged identities. Undergraduate courses that focus on diversity and multiculturalism have provided important sites for the collection of quantitative measures relating to White privilege. Some quantitative studies report positive findings regarding changes in students’ attitudes about racism, including the demonstration of improved judgments of Black students (Chang, 2002), and increased acknowledgment of structural racism in response to content about White privilege (Boatright-Horowitz et al., 2013). However, in the larger body of literature regarding outcomes of diversity coursework, findings are complex, only interrogate experiences of students of color, and often vary by social identity (Denson and Bowman, 2017).

Results from other quantitative and mixed method studies elaborate on the differing results of diversity courses that focused on racism and White privilege. Henderson-King and Kaleta (2000) found that for students who were enrolled in courses that incorporated social diversity, intergroup tolerance neither increased nor decreased. However, for those undergraduate students who were not enrolled in such courses, tolerance of others decreased over the course of a semester. Case (2007) research regarding attitudes toward affirmative action also demonstrated multiple outcomes, including increased support for affirmative action and greater self-awareness of White privilege and racism, as well as a heightened sense of White guilt and increased racial prejudice. Other studies reported both positive and negative outcomes, where the latter was often fueled by a sense of White guilt (Boatright-Horowitz et al., 2012; Kernahan and Davis, 2007). Students’ beliefs toward White guilt, White privilege, and in American meritocracy (Swank et al., 2001; Asada et al., 2003; Munroe and Pearson, 2006) have also been linked to their acceptance of multicultural learning environments. These constructs, however, do not measure students’ degree and expressions of resistance when confronted with dissonance-provoking stimuli in multicultural spaces. This investigation sought to operationalize defensive reactions through the development and validation of the PIE-S. Guided by the PIE model, the PIE-S proposes to assess how individuals express defensive reactions to difficult classroom dialogues about racism across identity groups.

Materials and Methods

There were two systematic studies completed to develop the PIE-S: scale development and scale validation. Human subjects research approval was obtained for both studies from the first author’s institutional review board. This section begins with a description of the research team and the sample, followed by the procedures and analysis process of the two PIE-S studies.

Research Team

The Multicultural Initiatives (MCI) Research Team, including interdisciplinary faculty from multiple institutions of higher education, doctoral students, and master’s students, worked collaboratively during the 4-years process. The research team underwent a rigorous process of individual and group learning, including personal storytelling, examination of social identities, and skill enhancement for engaging in difficult dialogues. The social identities of the members on the research team varied by race, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, age, and other social identity variables. All team members had prior academic knowledge and experience with the PIE model and multiculturalism.

Samples

Unique samples were used for each study. The first sample (study 1) was used for scale development and included a total of 864 students who participated in an online survey. To triangulate data with the initial qualitative work on privileged racial identity (Watt, 2007; Watt et al., 2009), which served as the foundation for the scale, all students in Study 1 were sampled from the same institution of higher education as the previous qualitative studies. We conducted census sampling and sent a mass email inviting all students to participate in the study. We used listwise deletion to remove any participant who did not complete at least 90% of the survey. When looking at the missing data pattern, this approach primarily removed respondents who started and did not continue pass the first page of survey questions. Further, we specifically chose listwise deletion for our sample given the research suggesting the gains from other ways of handling missing data are minor (Cheema, 2014). The final analytic sample included only White students who did not identify with any other racial category (n = 499, 30.86% cisgender men, 65.73% cisgender women). First year undergraduate students accounted for 24% of the study 1 sample and master’s students had the next highest representation (18%). Other students included: 10% second year, 15% third year, and 13% fourth year undergraduate students, as well as 13% professional students, and 5% doctoral students. The age of the sample ranged from 18 to 59. Students of aged 18 to 22 represented 59% of the sample, with students under 33 years comprising 91% of the sample. The sample consisted of 99% domestic students and 1% international students. The students’ home origins included 59% from suburban settings, 29% from rural settings, and 12% from urban settings. Students from middle socioeconomic status represented 81% of the sample. An additional 9% identified as high social class and 9% identified as low social class. Students with a disability (physical, visual, auditory, cognitive or mental, emotional, or other) represented 21% of the total sample, with 2% opting not to disclose their ability status and 77% identifying no persistent or recurrent condition.

The second sample (study 2) was used for scale validation. The sample was collected in two separate waves from three institutions of higher education in three different states. In the first wave, the survey data was collected via census sampling from a large, public, historically, and predominantly White institution (HPWI); an institutional mass e-mail was sent to all graduate and undergraduate students. The sample was expanded to two more institutions-another large, public, HPWI in the Midwest, as well as a midsize, public, HPWI in the Northeast. The methods of data collection respectively yielded 1,080 participants. The overall sample included primarily undergraduate students (81%). Of the sampled students, 58% described their home of origin as a suburban setting, 33% rural, and 9% urban. Cisgender women are overrepresented in the sample (66%). Cisgender men represented 29%, less than 2% identify as transgender or as another gender identity not listed, and 1% of the sample identified as gender non-conforming or gender queer. Students who were differently abled represent 17% of respondents, with 80% indicated no recurrent or persistent conditions, and 3% who preferred not to answer. Students’ social class indicated a left skewed normal distribution with 68% identifying as middle class. When removing cases with more than 10% missing data, the final analytic sample for the validation was 745 (75.83% White, 24.17% all other races1; 25.65% cisgender male, 51.48% cisgender female, 22.87% non-binary). The validation included all races to provide information related to generalizability.

Procedures and Data Analysis

The instrument development process involved two studies, modeled from Dawis (1987) rational-empirical approach, and was guided by standards and guidelines of scale construction (DeVellis, 2003; Worthington and Whittaker, 2006).

Scale Development (Study 1)

The goal of this study was to generate and distinguish items for inclusion in the instrument to empirically measure defenses from the PIE model. The first study involved 1) item development and 2) item analysis (Dawis, 1987). The goal of item development was to generate sufficient items to encompass the key constructs in the proposed PIE-S. The MCI team began with initial item development, selection of items, and a card sort procedure. A content validity check, expert focus group, and factor analysis were then completed; 80 items, across the eight defenses in the PIE model were generated. Once the initial set of items was established, the MCI team performed a two-step process of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the first sample of participants to evaluate the proposed scale. In the item analysis step, the team identified the items that would remain in the revised scale, informed by statistical and theoretical considerations.

Scale Validation (Study 2)

After determining the appropriate factor structure of the PIE-S, the goal of the scale validation was to determine the scale’s convergent and discriminant validity by examining the factors’ relationships to four criterion measures (described below) informed by resistance theory and the higher education literature about students’ experiences with diversity: beliefs in descriptive meritocracy (Zimmerman and Reyna, 2013), White guilt (Swim and Miller, 1999), racial attitudes (i.e., Attitudes Toward Blacks; Brigham, 1993), and social desirability (Crowne and Marlowe, 1960).

Criterion Measures

Descriptive meritocracy. The possibility that one’s accomplishments may be unearned conflicts with the belief that people tend to earn what they deserve, so we predicted that belief in meritocracy would positively predict denying or avoiding White privilege–two defenses that may preserve the sense that one’s accomplishments are one’s own (see also Knowles et al., 2014). We measured beliefs about meritocracy with the Zimmerman and Reyna (2013) Descriptive Beliefs Scale for Meritocracy. This scale arranges eight affirmative and reverse-scored items on a 5-point scale from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). A sample item from the scale is “In America, people get rewarded for their effort.” Responses were reverse-coded when necessary such that higher scores correspond with stronger beliefs about meritocracy. Zimmerman and Reyna reported a satisfactory internal consistency of 0.63. The coefficient alpha for the current sample was 0.75.

White guilt. People feel collective guilt when they see their group as responsible for unjust harm to others (Doosje et al., 1998). Those who feel White guilt should engage in defenses that acknowledge the existence of White privilege and that one may benefit from privilege, and thus we predicted that White guilt would negatively predict denying and avoiding. Furthermore, engaging in overcompensating and moralizing require that a person acknowledge privilege, and may act to assuage feelings of guilt, so we predicted that White guilt would positively predict overcompensating and moralizing. We measured White guilt with Swim and Miller (1999) White Guilt Scale. This scale comprises five items, each containing the term “guilt” or guilty” to reflect the respondent’s self-perception of White guilt. The items are arranged a 5-point Likert scale from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). A sample item from the scale is, “I feel guilty about the benefits and privileges that I receive as a White American.” A higher score reflects stronger feelings of White guilt. The authors reported a strong internal consistency of 0.86. The coefficient alpha for the current sample was 0.90. A higher score reflects strong feelings of White guilt.

Racial attitudes. To ensure that the PIE-S factors were not simply measuring prejudicial attitudes, we measured explicit positive racial attitudes toward Blacks. We expected that the factors would covary with racial attitudes (negatively for avoiding and denying, positively for moralizing and overcompensating), but not at such a magnitude that would suggest redundancy between the measures. Racial attitudes (i.e., prejudice) were measured using 12 items across two relevant subscales of Brigham (1993) measure of Attitudes Toward Blacks. The Social Distance subscale measures discomfort associated with interacting with Black people (e.g., “I would rather not have Blacks live in the same apartment building I live in.”) and the Affective Reactions subscale measures prejudice-related reactions (e.g., “I get very upset when I hear a White make a prejudicial remark about Blacks,” reverse-scored). Items are arranged on a 7-point Likert-type scale, anchored at one (strongly disagree) and seven (strongly agree). Higher scores on both subscales indicate greater anti-Black hostility. Brigham reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 which was consistent with the coefficient alpha for the current sample (0.85).

Social desirability. Self-report measures are vulnerable to social desirability effects, particularly for sensitive issues (Crowne and Marlowe, 1960). To test the degree to which the PIE-S might be susceptible to social desirability effects, we used the short-form version of Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MC-Form A) (Reynolds, 1982). The original MC-SDS (Crowne and Marlowe, 1960) consists of 33 true-false items measuring one’s need to seek approval by answering questions deemed appropriate and culturally acceptable (e.g., “I’m always willing to admit it when I make a mistake”). Higher scores indicate greater concern for social approval and higher levels of unwillingness to respond truthfully. The original measure has an internal consistency of 0.88 and a test-retest stability coefficient of 0.89. The short form version of the instrument (Form C) consists of 13 of the original 33 items and has a correlation of 0.93 with the standard form (Reynolds, 1982). Reynolds reports that the internal consistency of the MC-Form A was 0.74. The coefficient alpha for the current sample was 0.71.

Demographic Measures

Race and gender identity comparisons. Scale validation was also examined by comparing the final subscales by different identity groups. First, we examined the zero-order correlations between each criterion measure and each PIE-S factor. Second, we conducted four OLS regressions, in which each PIE scale was separately regressed on the four criterion measures and then with gender and race. These regressions reveal both the unique relationship of each criterion measure with each PIE-S factor after accounting for all other variables in the regression, and the extent to which each PIE-S factor is accounted for by the criterion measures.

Results

PIE-S Factor Structure (Study 1)

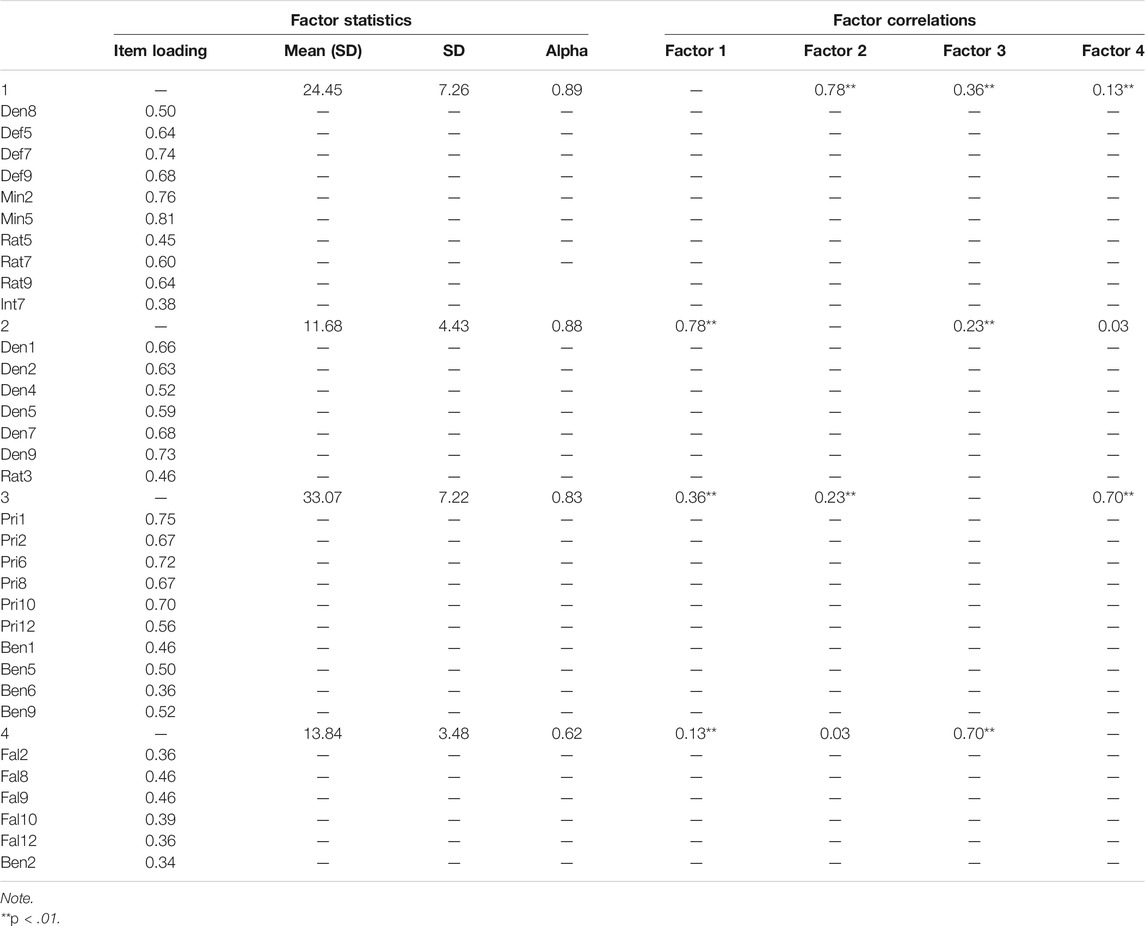

A Principal Factor Analysis (PFA) with promax rotation was conducted on the initial pool of 80 items to estimate the number of factors underlying the scale. The PFA suggested that a three-factor solution was most plausible; three factors reached an eigenvalue of greater than 1.0 and accounted for 33.4% of the common variance. Items with less than 0.40 loadings on one factor or with cross-loadings greater than 0.40 were examined more closely. Twenty-three items that either had strong cross-loadings or did not load strongly on any factor were eliminated, reducing the scale to 57 items. A second PFA was then run on the pool of 57 items to examine the effect of removing items on the factor structure. Four factors reaching an eigenvalue of greater than 1.0 accounted for 38.8% of the variance. We continued to examine items for clarity and factor loadings (>0.40) and as a result eliminated items, reducing the scale to 33 items and four factors. Before item reduction was complete, we made minor grammatical revisions to a few existing items. Item factor loadings for the final EFA are provided in Table 2, which also includes the means, standard deviations, and alpha coefficients for each of the factors. The alphas coefficients are moderate to strong across the four factors, ranging from 0.62 to 0.89. Also reported in this table are the inter-scale correlations for the four factors; the inter-scale correlations are appropriate, although the correlation between factors 1 and 2 (r = 0.78) and factors 3 and 4 (r = 0.7) are relatively high. This may be explained by how theoretically close the constructs of avoiding privilege and denying privilege are.

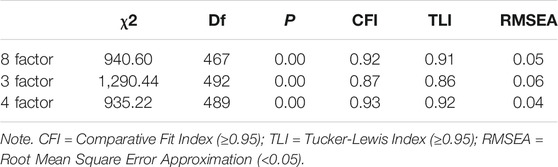

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the final 33-item version of the instrument to validate the factor structure. The CFA tested three models: 1) an eight-factor solution based on the original PIE model; 2) a three-factor model identified by the initial exploratory factor analysis; and 3) a four-factor model identified by the subsequent exploratory factor analysis. Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were used as fit indices. Cutoffs for fit indices were drawn from guidelines for adequate fit (RMSEA <0.10, CFI >0.90) (Huck, 2012) with more stringent criteria for optimal fit (RMSEA ≤ 0.06, CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95) (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Hanson and Kim, 2007). Model fit indices for the three models are provided in Table 3.

The results indicated that the four-factor model was a good fit for the data and the best fitting among the three models. The final 33-item scale consisted of the four subscales: Avoiding Privileged Identity, Denying Privileged Identity, Moralizing Privileged Identity, and Overcompensating for Privileged Identity. Higher scores on each subscale indicate greater likelihood of engaging in that type of defense in response to a dissonance-provoking stimulus. In the first study, alpha coefficients were 0.89, 0.88, 0.83, and 0.62 respectively. For the second study, coefficient alphas were 0.87, 0.87, 0.86, and 0.71, respectively.

Association Between PIE-S and Criterion Measures (Study 2)

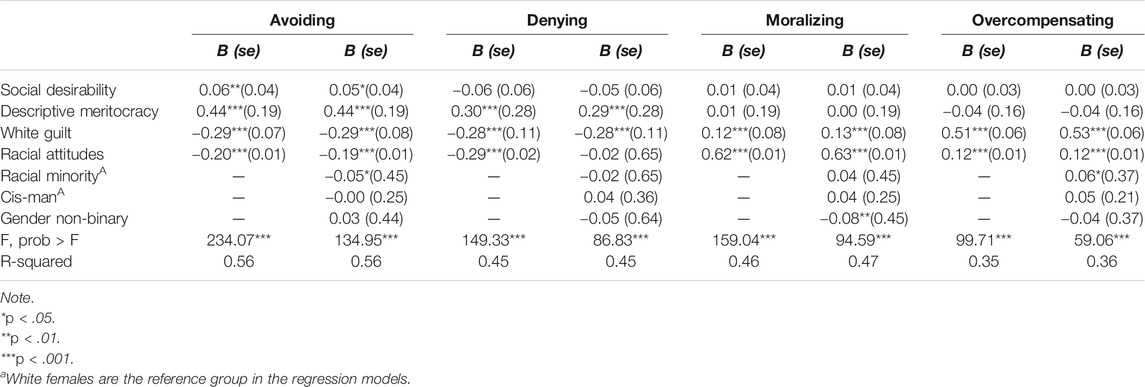

The validation study included analyzing 1) the extent to which each PIE-S factor is accounted for by the criterion measures, and 2) the relationship between a person’s race and gender identity and their defensive responses to difficult dialogues. Analyzing the correlations among PIE-S factors in relation to the criterion measures (Table 4) indicate evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. Similar to Study 1 results, the correlations between Avoiding and Denying (r = 0.68) and Moralizing and Overcompensating (r = 0.62) were moderately high compared to the other inter-scale correlations among the PIE-S factors indicating some degree of overlap between the PIE concepts. In relation to the criterion measures, Avoiding and Denying were again similarly associated (in effect size, direction, and significance) to descriptive meritocracy, White guilt, and racial attitudes. As expected, Moralizing and Overcompensating showed the opposite pattern, as they were both negatively associated with descriptive meritocracy, positively related to White guilt, and negatively related to racial attitudes, although the relationships appear to be stronger between Moralizing and racial attitudes, and Overcompensating and White guilt.

TABLE 4. Summary data, correlations, and alpha levels for PIE and criterion measures in validation sample.

As illustrated in Table 5, our OLS regression analyses found that while 35–56% of the variance in the four PIE-S factors was explained by the four criterion measures, a substantial portion of the variance in the PIE-S factors remained unaccounted for by these constructs. This result confirmed that the PIE-S displayed enough reliability to measure the privileged identity defenses and that these defenses capture a distinct construct related to students’ racial beliefs and attitudes.

TABLE 5. OLS regression results examining associations between PIE, criterion measures, race and gender in validation study.

When race (1 = all else, 0 = White) and gender identity (cis-gender men, cis-gender women, and non-binary) were included as main effects in the regression models, the effect of racial attitudes on denying became non-significant. Additionally, individuals from minoritized racial groups reported lower avoiding and higher overcompensating, when compared to White respondents. Respondents who identify as gender non-binary reported lower moralizing.

Discussion

The aim of the current investigation was to develop a valid quantitative instrument to measure the defenses individuals display when exploring their privileged identities. Experiencing dissonance-provoking stimuli (DPS) may trigger difficult feelings in students when confronted with the realities associated with their own privilege. They will then respond with observable defense mechanisms as a result of encountering the dissonance. Previous conceptions of privileged identity exploration (Watt, 2007; Watt, 2015) categorized those defenses that arise in individuals into a three-element structure: recognizing, contemplating, and addressing. The scale development and validation process revealed a reliable and valid four-factor structure: avoiding, denying, moralizing, and overcompensating for privileged identity. While these factors conceptually capture different elements of the privileged identity exploration process than the original model, they provide more detail about the motivations behind a defensive reaction that describe and capture the original conception of the PIE model.

Description of Resulting Four Factors

While the original PIE model included eight defensive reactions, a four-factor model was found. The discussion includes an explanation of the relationship between the final model and the original eight defenses of the PIE model. In brief, the four factors capture the essence of each of the eight defenses and the process of exploration that identifies reactions when recognizing, contemplating and/or addressing privileged identity.

Factor 1: Denying privileged identity (denial). Responses in this factor fit with a failure to recognize the reality of racism and its effects. This is reflected both in the nature of the items loading on this factor, and in their association with more negative racial attitudes. With this defense, racism is a myth, an illusion, or shadows from the past that no longer exist; racism is not an issue and the perceived effects of racism are really the result of something else. When reacting to the DPS, individuals who deny privileged identity remain emotionally and intellectually detached (from fear and/or entitlement) and actively displace the dissonance away from their sense of self. Fitting with this, greater denial corresponds to reporting lesser White guilt (i.e., a lower sense of responsibility for addressing racial privilege) and greater belief in descriptive meritocracy (which can serve to justify existing inequalities).

Factor 2: Avoiding privileged identity (deflection, minimization, intellectualization, and rationalization). Responses in this factor fit with recognizing the existence of racism, but minimize, explain away, deflect, or intellectualize racism and its effects. With this defense, individuals can identify instances of racism, but generate other explanations for why racism and its effects exist. We observed that greater avoiding corresponds to more negative racial attitudes, and at nearly the same magnitude as denying. When reacting to the DPS, individuals who avoid exploring privileged identity remain emotionally detached, but can begin to engage intellectually to protect the self from disorienting information. In this vein, avoiding showed the strongest relationship of any factor to endorsement of descriptive meritocracy.

Factor 3: Overcompensating for privileged identity (false envy). Responses in this factor reflect an acknowledgment of racism with some contemplation of the realities of racism. With this defense, individuals may offer platitudes, compliments, and feigned jealousy toward the “other” or over-romanticize and objectify the “other” to address the effects of racism. The individual is likely in relationship with the DPS such as working alongside a person who experiences being marginalized due to race. When reacting to the DPS, individuals who overcompensate for privileged identity have an emotional response and awareness of the fear and entitlement that the DPS provokes. Our results found that overcompensating was associated with the highest effect size for White guilt, but lowest for racial attitudes compared to the other factors. Thus, when overcompensating, people have feelings toward the DPS but are still concerned with distancing the self from the disorienting information and the ways it is disorienting to them.

Factor 4: Moralizing privileged identity (principium and benevolence). Responses in this factor reflect an acknowledgment of racism with actions addressing the realities of racism. Along these lines, greater moralizing was associated with reporting more positive racial attitudes. With this defense, individuals’ responses acknowledge that racism exists and invoke morals and ethics as a sufficient way to address racism. However, this moral authority protects individuals from having to do much more than appear helpful by donating money or time. When reacting to the DPS, individuals who moralize privilege identity engage emotionally and intellectually with the DPS by more actively facing the fear and entitlement the dissonance provokes and see racism as something to be dealt with.

Relationships among the factors. Denying and avoiding correlated substantially with one another and exhibited similar patterns across the criterion variables (i.e., greater endorsement of meritocracy, lesser White guilt, and more negative racial attitudes). Overcompensating and moralizing, on the other hand, also correlated substantially with one another and likewise showed a similar pattern across the criterion variables (i.e., lesser endorsement of meritocracy, greater White guilt, and more positive racial attitudes). This suggests that those who are likely to respond to dissonance-provoking stimuli with denial are also likely to respond with avoidance, and that those who overcompensate are also likely to moralize. However, the fact that these were identified as four distinct factors, and that their positive correlations are not extremely large, suggests that they will still vary independently of one another. Interestingly, the correlations between denying or avoiding, on one hand, and overcompensating and moralizing, on the other, are all small or near-zero. Thus, despite the opposite patterns of correlations across the criterion variables, just because a person engages in Denial or Avoidance does not mean they won’t also engage in Overcompensating and Moralizing. This fits with the PIE approach, which assumes that people do not exhibit a statistic pattern of only one or two defenses, nor do they necessarily move out of certain defenses and into others, but that they may engage in multiple defenses, and different ones at different times (Watt, 2015).

Comparing the Four and Eight PIE Factors

The PIE model looks at how emotions, beliefs, and attitudes around a privileged social identity are animated upon facing dissonance; defensive reactions to dissonance-provoking stimuli are the external manifestations of the inner discomfort that arises when confronted with information that challenges one’s position with difference. Conceptually, the four-factor structure of avoiding, denying, overcompensating, and moralizing, offers a revised schema for noticing and naming PIE defenses in ourselves and others. Results showed relatively higher inter-scale correlations between some of the PIE-S factors, which may indicate that the structural elements may not be optimally adding unique contributions to the construct of privileged identity. Specific expressions of defensive reactions might reflect multiple of the four PIE factors identified here. For example, consider a course that explores social inequities in America and exposes many instances in which people of color were not included as equals in this society and how that has shaped the American cultural context of oppression. This idea might be new and dissonance provoking for those with racial privilege in the group. Those individuals might deflect and blame the historical teachings of an educational system that focuses on the role of White people, as the reason they are unaware of the contributions made to America by people of color. Inherent in this deflection may also be a denial and a minimization: The individuals may argue that the contribution of non-White people could not be substantial (denial) or that it must be small (minimization) because it was not taught in school. This defensive reaction may serve to protect individuals from the discomfort the new information causes. As researchers, we need to explore areas of overlap and distinctions and the utility of the substantive elemental difference in more depth. Further studies may consider analyses that can better describe potential distinct influences of each pair of factors.

The current results from this study do connect to previous studies by offering the factors of the PIE-S as potential mediating variables that link the literature on prejudicial racial attitudes (e.g., Swim and Miller, 1999; Brigham, 1993) with the transformative potential of multicultural learning environments to raise awareness of and shifts in those emotions and attitudes (Boatright-Horowitz et al., 2012; Munroe and Pearson, 2006). For example, Kernahan and Davis (2007) also used Swim and Miller (1999) White guilt scale (which we used as a criterion variable) and racism scales to assess the racial awareness and attitudes of students taking a diversity class. They found that students’ awareness of racism increased between the beginning and end of the class and that students agreed that “action is needed and that they should take responsibility” (Kernahan and Davis, 2007, p. 51). In the context of these findings, and similarly designed studies in the multicultural higher education literature (Boatright-Horowitz et al., 2012; Case, 2007; Munroe and Pearson, 2006; Swank et al., 2001), the PIE-S is a complementary measure that can demonstrate the different ways that individuals take action to alleviate discomfort because of their newfound awareness or guilt. As aforementioned, individuals are motivated to protect themselves from the discomfort that new information causes (Harmon-Jones and Mills, 2019), particularly in relation to privileged social identities (Watt, 2015). For some, taking action may involve avoiding difficult dialogues around charged social issues; for others, taking action may involve moralizing and engaging in charitable giving as a result of a sense of guilt and increased awareness. Common across the two scenarios is the animation of action that focuses on managing individuals’ reconciling of their guilt (emotions) or awareness (thoughts) so as not to be seen as racist, sexist, etc.; however, the behavior itself does not necessarily locate the self in challenging systemic oppression. Taking action and having a sense of responsibility is still focused on alleviating individual discomfort. The original PIE model acknowledges how emotions and thought intertwine to animate defensive reactions in individuals (Watt, 2015). The PIE-S expands upon the original model and existing studies by demonstrating empirically how different combinations of emotions and thought become expressed into different defensive reactions. Specifically, across the regression models, white guilt and racial attitudes were significantly associated with all four PIE-S factors but with varying valence (positive or negative regression coefficient) and magnitude (size of regression coefficient). Thus, in relation to existing research, the PIE-S presents an approach and measure to understanding the dynamic ways in which individual emotions, beliefs, and attitudes interact when people encounter difference (Watt, 2015).

Implications for Practice

The increased focus on difficult dialogues and exploring privileged social identities in college environments points to a need for the Privileged Identity Exploration Scale (PIE-S). Conscious minded scholar-practitioners and researchers (Watt, 2015) frequently engaged in discussions about implications for practice in our varying campus and community roles. However, we also recognized the importance of instrument validation as a means to develop a strong methodological base for research and assessment approaches to inform practice. With these considerations in mind, the development and validity of the PIE-S calls for the need to translate research from multicultural assessments like this one for applied use in collegiate contexts and beyond. Students, faculty, and student affairs professionals can benefit from opportunities to gain self-awareness and develop the skills stemming assessments of their defensive reactions.

Ultimately, defensive reactions are often what derails productive dialogue across controversial difference. Using the PIE theory and PIE-S to assist in noticing, naming, and nurturing the awareness reactions might support facilitation of difficult dialogues that is compassionate and more productive (Watt, 2015). Facilitators can use the PIE research to improve their skills in being able to recognize defenses that can lead to greater understanding of the complexities of dialogues across differences. Awareness of the various shades of defensive reactions can strengthen the ability for both a facilitator and participants to sit with the discomfort of social divides that cause dissonance. Building the stamina to sit and work through conflict might increase the possibility that participants with polarizing differences to work through toward some equitable resolution of the disagreement. This research offers some hope that community members improve their ability to listen with more acuity to the conflicts they have with the people who see the world in fundamentally different ways.

Implications for Future Research

With the shifting racial demographics in the United States (see Omi and Winant, 2014), college environments will have situations where students from majority identities will encounter those with minoritized identities. These experiences could be considered dissonance-provoking stimuli for both students from both identities but will likely be a new experience for majority identified students. A limitation of the current work is that it has been based in predominantly White institutions and as a result draws from primarily White, female samples. While research on dissonance provoking stimuli and defensive reactions stemming from majority, White racial identity serves to normalize defensive reactions as a form of social cognition and deepens knowledge on interrupting modes of reproduction, future research needs to replicate this work in more diverse samples to expand the PIE model and scale. Scholars should consider further psychometric examinations of the PIE model and PIE-S. Researchers should continue to validate the measure including investigations regarding the epistemological consistency of the measure over time. These analyses might employ longitudinal studies with pre/posttest research designs to consider change in students while in college. Given that the current research utilized data from only three universities, scholars may also conduct research that utilizes larger and more diverse samples to further validate generalizability of the data. Replication and validation efforts should also cast a broader net and examine defensive reactions in general populations, not just from individuals interacting within institutions of higher education. Future versions of the scale should also consider defensive reactions to issues and identities beyond race to more comprehensively capture all dimensions of the original PIE model. Finally, the PIE-S attends to individual attitudes and perceptions of their own privileged identities. Research should consider behavioral dispositions that may be associated, or coexist, with attitudinal factors.

Conclusion

As college students learn about privilege and experience resistance, colleges have the opportunity to guide and support students’ development. Currently, there is no way to measure students’ defensive reactions leaving students, staff, and faculty without the ability to identify where students are to guide their development. PIE-S was developed as a valid and reliable instrument to measure defensive reactions to difficult dialogue regarding sociopolitical racial topics within a higher education context. The PIE-S offers quantitative evidence for the original PIE model (Watt, 2007; Watt, 2015) and has utility for both future and practice on campuses as communities find productive ways to engage across controversial social and political differences.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of intellectual property and licensing guidelines outlined by the University of Iowa. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to mci-team@uiowa.edu.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SW developed the theoretical framing of the study. JM, EP, KP, CK, and AM designed the study, developed the survey items, and collected the data. RN and DM refined the data analysis approach, cleaned, and analyzed the data. The MCI Consortium includes current and alumni members of the Multicultural Initiatives Research Team who contributed to the conceptualization of the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the statistical analyses and conceptualization of the final manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by a Faculty Research Grant from the Iowa Measurement Research Foundation (University of Iowa, College of Education, Iowa City, IA).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1“All other races” includes the following categories, which were collapsed for analyses due to small cell sizes: African American or Black; American Indian or Alaskan Native or Indigenous or First Nations; Arab or Middle Eastern; Asian or Asian American; Hispanic or Latina or Latino; Multiracial or Biracial; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; Other

References

Abowitz, K. K. (2000). A Pragmatist Revisioning of Resistance Theory. Am. Educ. Res. J. 37 (4), 877–907. doi:10.3102/00028312037004877

Asada, H., Swank, E., and Goldey, G. T. (2003). The Acceptance of a Multicultural Education Among Appalachian College Students. Res. Higher Educ. 44 (1), 99–120. doi:10.1023/a:1021369629549

Assaf, L. C., and Dooley, C. M. (2006). Everything They Were Giving Us Created Tension": Creating and Managing Tension in a Graduate-Level Multicultural Course Focused on Literacy Methods. Multicultural Educ. 14 (2), 42.

Boatright-Horowitz, S. L., Frazier, S., Harps-Logan, Y., and Crockett, N. (2013). Difficult Times for College Students of Color: Teaching white Students about White Privilege Provides hope for Change. Teach. Higher Educ. 18 (7), 698–708. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.836092

Boatright-Horowitz, S. L., Marraccini, M., and Harps-Logan, Y. (2012). Teaching Antiracism. J. Black Stud. 43 (8), 893–911. doi:10.1177/0021934712463235

Brigham, J. C. (1993). College Students' Racial Attitudes. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol 23 (23), 1933–1967. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01074.x

Case, K. A., Iuzzini, J., and Hopkins, M. (2012). Systems of Privilege: Intersections, Awareness, and Applications. J. Soc. Issues 68 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01732.x

Case, K. A. (2007). Raising White Privilege Awareness and Reducing Racial Prejudice: Assessing Diversity Course Effectiveness. Teach. Psychol. 34, 231–235. doi:10.1080/00986280701700250

Chan, C. S., and Treacy, M. J. (1996). Resistance in Multicultural Courses. Am. Behav. Scientist 40 (2), 212–221. doi:10.1177/0002764296040002012

Chang, M. J. (2002). The Impact of an Undergraduate Diversity Course Requirement on Students' Racial Views and Attitudes. J. Gen. Educ. 51 (1), 21–42. doi:10.1353/jge.2002.0002

Cheema, J. R. (2014). Some General Guidelines for Choosing Missing Data Handling Methods in Educational Research. J. Mod. App. Stat. Meth. 13 (2), 53–75. doi:10.22237/jmasm/1414814520

Crowne, D. P., and Marlowe, D. (1960). A New Scale of Social Desirability Independent of Psychopathology. J. Consulting Psychol. 24 (4), 349–354. doi:10.1037/h0047358

Denson, N., and Bowman, N. A. (2017). “Do diversity Courses Make a Difference? A Critical Examination of College Diversity Coursework and Student Outcomes,” in Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Editor M.B. Paulsen (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 35–84. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-48983-4_2

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 2nd ed.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N. R., Spears, R., and Manstead, A. S. R. (1998). Guilty by Association: When One's Group Has a Negative History. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 75 (4), 872–886. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.872

Fischer, E. M. J. (2007). Settling into Campus Life: Differences by Race/ethnicity in College Involvement and Outcomes. J. Higher Educ. 78 (2), 125–161. doi:10.1080/00221546.2007.11780871

Hanson, T. L., and Kim, J. (2007). Measuring Resilience and Youth Development: The Psychometric Properties of the Healthy Kids Survey. (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007–No. 034) (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory West). doi:10.1037/e607962011-001

Harmon-Jones, E., and Mills, J. (2019). “An Introduction to Cognitive Dissonance Theory and an Overview of Current Perspectives on the Theory,” in Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology. Editor E. Harmon-Jones (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 3–24. doi:10.1037/0000135-001

Henderson-King, D., and Kaleta, A. (2000). Learning about Social Diversity. J. Higher Educ. 71 (2), 142–164. doi:10.1080/00221546.2000.11778832

Hill, R. J. (2009). Incorporating Queers: Blowback, Backlash, and Other Forms of Resistance to Workplace Diversity Initiatives that Support Sexual Minorities. Adv. Developing Hum. Resour. 11 (1), 37–53. doi:10.1177/1523422308328128

Hill-Jackson, V., Sewell, K. L., and Waters, C. (2007). Having Our Say about Multicultural Education. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 43 (4), 174–181. doi:10.1080/00228958.2007.10516477

Hu, L. t., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Jaekel, K. (2016). What Is normal, True, and Right: a Critical Discourse Analysis of Students' Written Resistance Strategies on LGBTQ Topics. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 29 (6), 845–859. doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1162868

Kayes, P. E. (2006). New Paradigms for Diversifying Faculty and Staff in Higher Education: Uncovering Cultural Biases in the Search and Hiring Process. Multicultural Educ. 14 (2), 65–69.

Kernahan, C., and Davis, T. (2007). Changing Perspective: How Learning about Racism Influences Student Awareness and Emotion. Teach. Psychol. 34 (1), 49–52. doi:10.1080/00986280709336651

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M., and Unzueta, M. M. (2014). Deny, Distance, or Dismantle? How white Americans Manage a Privileged Identity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 (6), 594–609. doi:10.1177/1745691614554658

Linley, J. L. (2017). Teaching to Deconstruct Whiteness in Higher Education. Whiteness Educ. 2 (1), 48–59. doi:10.1080/23793406.2017.1362943

Martinez-Cola, M., English, R., Min, J., Peraza, J., Tambah, J., and Yebuah, C. (2018). When Pedagogy Is Painful: Teaching in Tumultuous Times. Teach. Sociol. 46 (2), 97–111. doi:10.1177/0092055x17754120

Munroe, A., and Pearson, C. (2006). The Munroe Multicultural Attitude Scale Questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 66 (5), 819–834. doi:10.1177/0013164405285542

Omi, M., and Winant, H. (2014). Racial Formation in the United States. New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203076804

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of Reliable and Valid Short Forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 38, 119–125. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<119::aid-jclp2270380118>3.0.co;2-i

Swank, E., Asada, H., and Lott, J. (2001). Student Acceptance of a Multicultural Education. J. Ethnic Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 10 (2), 85–103. doi:10.1300/j051v10n02_06

Swim, J. K., and Miller, D. L. (1999). White Guilt: Its Antecedents and Consequences for Attitudes toward Affirmative Action. Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 25 (4), 500–514. doi:10.1177/0146167299025004008

Torres, V., Arminio, J., and Pope, R. L. (2012). “Why Aren't We There yet?,” in Taking Personal Responsibility for Creating an Inclusive Campus (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC).

Watt, S. K., Curtis, G. C., Drummond, J., Kellogg, A. H., Lozano, A., Nicoli, G. T., et al. (2009). Privileged Identity Exploration: Examining Counselor Trainees' Reactions to Difficult Dialogues. Counselor Educ. Supervision 49 (2), 86–105. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00090.x

Watt, S. K. (2015). Designing Transformative Multicultural Initiatives: Theoretical Foundations, Practical Applications and Facilitator Considerations. VA: Sterling.Stylus.

Watt, S. K. (2007). Difficult Dialogues, Privilege and Social justice: Uses of the Privileged Identity Exploration (PIE) Model in Student Affairs Practice. Coll. Student Aff. J. 26 (2), 114–126.

Watt, S. K. (2012). “Moving beyond the Talk: From Difficult Dialogue to Action,” in Why Aren’t We There yet: Taking Personal Responsibility for Creating an Inclusive Campus. Editors J. Arminio, V. Torres, and R.L. Pope (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing), 131–144.

Worthington, R. L., and Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale Development Research. Couns. Psychol. 34 (6), 806–838. doi:10.1177/0011000006288127

Keywords: difficult dialogues, identity, race, student affairs, scale development, defenses

Citation: Watt SK, Mueller JA, Parker ET, Neel R, Pasquesi K, Kilgo CA, Mollet AL, Mahatmya D and Multicultural Initiatives Consortium (2021) Measuring Privileged Identity in Educational Environments: Development and Validation of the Privileged Identity Exploration Scale. Front. Educ. 6:620827. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.620827

Received: 01 April 2021; Accepted: 07 July 2021;

Published: 26 July 2021.

Edited by:

Royel Johnson, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesReviewed by:

Garry Kuan, Universiti Sains Malaysia Health Campus, MalaysiaCopyright © 2021 Watt, Mueller, Parker, Neel, Pasquesi, Kilgo, Mollet, Mahatmya and Multicultural Initiatives Consortium. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Duhita Mahatmya, duhita-mahatmya@uiowa.edu

Sherry K. Watt1

Sherry K. Watt1  Amanda L. Mollet

Amanda L. Mollet Duhita Mahatmya

Duhita Mahatmya