You Can’t Fix What Is Not Broken: Contextualizing the Imbalance of Perceptions About Heritage Language Bilingualism

- 1Department of Language and Culture (ISK), Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

- 2Department of Spanish and Portuguese Studies, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

- 3Universidad Nebrija, Madrid, Spain

In this article, we discuss the perceptions of researchers who work on heritage language bilingualism (HLB), educators who teach heritage speakers (HSs), and, crucially, HSs themselves regarding the nature of bilingualism in general as well as HLB specifically. Despite the fact that all groups are invested in HLB and that researchers and educators tend to have a similar basic understanding of HLB development and share common goals regarding heritage language (HL) teaching and learning, there are non-trivial differences and disconnects between them. In our view, beyond the various aspects of the societal milieu that significantly contribute to this state of affairs, we maintain that these differences also reflect unfortunate miscommunication regarding how the object and outcomes of HLB research is packaged, contextualized and communicated to HSs and teachers who have direct influence over their education. Considering this, the main goal and contribution of the present work is to provide a forum in which the many voices involved in HL research/teaching/learning are acknowledged and the knock-on effects of such acknowledgement are meaningfully considered.

Introduction

Since the 1960s there has been a shift in the way researchers conceive of and approach the study of bilingualism. Prior to the 1960s, it was largely believed that the juggling of more than one language in a single mind introduced confusion for the developing child, potentially resulting in detrimental outcomes for the so-called full acquisition of either language and/or in various effects on social and cognitive development more generally. In the extreme, some concluded that bilingualism could exacerbate, if not result in intellectual disabilities (Saer, 1923; Goodenough, 1926).

While it is not unreasonable to hypothesize that the cognitive demands inherent to bilingualism could have some developmental tradeoffs (indeed there are some), the context that framed the pre-1960s approach was enabled and sustained by ignoring the actual global reality of bilingualism. Bilingualism has long been the default state of linguistic knowledge globally. Although it is true that bilingualism is relatively exceptional (although not exceedingly so) in some Western societies, especially where English is the majority native language, acquiring two or more languages from a very early age in other contexts such as Asia and Africa represents a more accurate, comprehensive view of the world’s population. Given that roughly 60% of the global population is bilingual (even multilingual) (e.g., Romaine, 1995; Grosjean, 1998; Grosjean, 2019)—in some countries over 90%—it does not make much sense a priori that acquiring more than one language would be a good candidate for stunting “natural” development in children. Indeed, unless there were some discernible differences one could meaningfully attribute to the ranges of outcomes (and correcting for co-occurring variables such as socioeconomic status) seen in children in default-monolingual as compared to societal default-bi-multilingual contexts, a deficit null hypothesis seems ill-conceived from the outset. To be sure, no such evidence exists.

As alluded to above, Western-centric research began to correct itself in the early 1960s, starting with a seminal study by Peal and Lambert (1962), henceforth P&L. P&L questioned the extent to which so-called bilingual deficit evidence reflected more the modality in which bilinguals were being tested at the time than anything one could generalize as a byproduct of bilingualism itself. A majority of the evidence indicating a potential bilingual deficit largely related to intelligence measured through language itself. Rightly, P&L proposed that if bilinguals were truly “confused” and bilingualism could be teased out as the deterministic variable inducing impaired trajectories of cognitive development, then such should be confirmable in tests of nonverbal intelligence. Alternatively, P&L hypothesized that the verbal modality tested in the societal language promoted monolinguals to seemingly better success. P&L conjectured that if language was removed from the testing modality, monolingual and bilingual children would show no differences, even if monolinguals might show higher scores within verbal measures.

Interestingly, the predictions of P&L were only partially confirmed. In their work, bilingual children not only outperformed monolingual peers on tests related to nonverbal intelligence but rather outperformed monolinguals on virtually all measures. Contrary to previous research, why was this so in P&L’s sample? P&L were pioneering beyond the way in which they framed the question. They controlled for many extraneous variables neglected in the previous literature that could render so-called monolingual and bilingual aggregates incomparable. Via P&L we began to understand that not only could bilingualism be a neutral factor for development, but rather potentially offer some benefits. In many ways, P&L marks a first step at what has become a primary focus in the cognitive science study of bilingualism in the modern era (seeBialystok, 2016, 2017 for discussion, seeLeivada et al., 2020 for discussion of related contemporary debates in this domain).

Peal and Lambert (1962) and the proliferation of studies ever since marks a reckoning with reality, a lesson of sorts we capitalize on for our discussion herein related to heritage language bilingualism (HLB). Such work underscores the need for pushing beyond what seems intuitive (questioning the very nature of that intuition) in how research frames and how it approaches bilingualism studies more generally. Despite the fact that nearly 60 years have passed since P&L, societal views and the valuation of bilingualism have not exactly caught up. Acknowleding this is of non-trvial significance. Afterall, it is well-established in the sociolinguistic literature that attitudes regarding languages—e.g., their perceived relative prestige, value and capital, motivations for their use/maintainence—within the global, national and community social mileus bring much to bear on the quantity, quality and context of accessing input and how individuals (unconsciously) are positioned to acquire and use language. Furthermore, this same research clearly points out that perceptions and practices at the family and individual level are highly deterministic for individual linguistic (variation) outcomes, language maintanence/change in individuals over the lifespan, language survival/shift diachronically, language policy and education (e.g., Fishman, 1991; Appel and Muysken, 2005; Hornerberger and Mckay, 2010; Tagliamonte, 2012; Chevrot and Foulkes, 2013; Johnson, 2013; Schmid, 2013; Ennser-Kananen and King, 2018). These same factors can have influence on the ways in which research itself is framed, how findings are interpreted and how the passing along of such is packaged and disseminated. Perhaps, then, it should not be so suprising that even in 2021, we find many health professionals, policy makers and other relevant stakeholders in predominantly monolingual societies still believing that bilingualism is a stumbling block to language acquisition, overall academic achievement and a potential source of mental confusion for children.

It would be unreasonable to expect people outside of any active research field to be intimately aware of the empirical basis underlying a so-called evidence-based message. However, it is fair to expect that any given message itself be evidence-based, consistent with the underlying support for it, and be accessible to stakeholders and end-users. Such a statement is universally pertinent, but especially so in the context of HLB. As researchers in HLB, we should take stock, iteratively, to (re)consider how we frame our object of study, especially the conclusions we draw and the terminological language we apply. The main point of research is, first and foremost, to accurately describe something and offer insights to fully understanding it. Doing this, of course, has consequences in the real world. While at the conscious level we tend to focus on the positive consequences, it is prudent to be mindful of the full gamut of potential consequences research can bring to bear. Arguably, the most impactful consequences are the ones that logically follow from claims, framing or terminology we use, yet are misguided and unintended.

As a case in point, the quotes below are particularly illuminating. Previous research has demonstrated for example, that heritage speakers (HSs) often show signs of low self-esteem or language shyness as it pertains to their linguistic abilities in their own native languages coupled with concerns regarding their minority ethnic identities and the general status of their heritage language (HL) (e.g., Carreira and Beeman, 2014). No doubt, a complex set of factors contribute to this state of affairs. That said, one important yet often neglected issue in unpacking the complexities of contributing variables involves the consideration of how HLB is framed and approached in general. The potential negative consequences cannot be overstated. Let us consider the following quotes referring to HSs and their grammars:

“In situations of societal bilingualism, the functionally restricted language evidences grammatical simplification, among other phenomena. The question that arises is whether this stage of grammatical simplification is due to imperfect or incomplete acquisition in the early years of life, or a result of processes of attrition or loss of acquired knowledge of the underused language.”

Silva-Corvalán (2014):(265)

“Because HL speakers are members of the HL group, their imperfections are very salient to more proficient speakers, who may respond by correcting and even with ridicule.”

Krashen (1998):(41)

In bold (our adding), we highlight wording that in our view contributes, albeit unintentionally, to the issue at hand. Word choices such as “imperfect” or “incomplete” passively concede that there is something lost or less-than about the linguistic knowledge of HSs. If we look at the publication dates, one could argue that these are outdated references with equally outdated framing of HLB. Surely, the field has experienced great advances over the last two decades. That said, this kind of language and qualifiers are deeply rooted in HLB; even by scholars who have advocated for terminological prudence and consideration for the value and diversity HLB entails. Consider the wording in bold from excerpts published in just the last 2 years:

“The hindered process of acquisition and development of Spanish underlies incompletely or partially acquired grammatical domains.”

“The literature to date has provided many examples of heritage speakers whose proficiencies differ from those of monolinguals, and in this context heritage speakers have often been portrayed as “incomplete” learners: “An incomplete learner or heritage speaker of language A is an individual who grew up speaking (or only hearing) A as his/her first language but for whom A was then replaced by another language as dominant and primary (Polinsky, 2008: 40).”

“[Heritage speakers] consistently have a higher integrative motivation to regain or further develop their heritage language, but at the same time they have unique needs (…)”

Beaudrie (2020):(3)

As we see it, these excerpts reveal a position on the matter; one that is influenced by (and entrenched in) traditional dynamics of power, the potential implications of which might very well fly under the radar of consciousness to the authors. Intentions aside, it is useful to ponder if such framing, which exists at the popular level and apparently at the academic level too, might create a feedback loop contributing to or reinforcing the very observations of affective obstacles HSs often face. The main goal of the present article, accordingly, is to engage in a dialogue that acknowledges and addresses this very possibility. In parallel to the important shift in messaging on bilingualism since the 1960s, the remainder of this article hones in on the specific case of HLB where we believe precise clarifications are warranted and better connections, if not communication, between all invested parties from researchers to educators to, crucially, HSs themselves are in need of fostering. After all, messaging related to HLB can be inconsistent or incoherent, if not in important ways divorced across various stakeholders.

It is well known that HSs, despite being a type of native speaker of their respective home or community minority languages (Rothman and Treffers-Daller, 2014), tend to differ in linguistic competence and performance from other native speakers whose acquisition takes place in a context where the same language is the sole (or one of the) dominant language(s) of the greater society (seeMontrul, 2008; Montrul, 2016; Polinksy, 2018 for reviews). Regardless of the term used to describe them (seePascual y Cabo and Rothman, 2012; Kupisch and Rothman, 2018; Dominguez et al., 2019 for discussion and dissenting points of view), HS differences typically refer to unexpected variation from a baseline of the illusive “ideal” dominant-native speaker or to the grammar of formal linguistic descriptions. There are many conspiring reasons for why differences obtain, most relating directly or indirectly to the opportunities HSs have for convergence on the (standard) baseline against which they are often described. Despite such differences, it is largely accepted that HS grammars are coherent, universally compliant ones in and of themselves (Rothman, 2009; Pascual y Cabo and Rothman, 2012; Kupisch and Rothman, 2018; Putnam et al., 2018; Bayram et al., 2019; Dominguez et al., 2019; Bousquette and Putnam, 2020; Polinsky and Scontras, 2020). In light of this juxtaposition of linguistic facts and factors, understanding the needs of HSs or the purpose of HL teaching in adulthood as a means to “regain” or “further develop” the natively acquired HL variety is often misguided.

Any discussion on the present topic cannot take place in a vacuum devoid of understanding the perspectives and perceptions of those most intimately involved. While individual stakeholder groups have been consulted (e.g., Ducar, 2008; Vergara Wilson and Pascual y Cabo, 2019), engaging researchers, educators and HS end-users together is not commonplace. Herein, we consider the views of HSs alongside those that do primary research on HLB and educators who work with HSs. We present an analysis of a common questionnaire administered to the above-mentioned groups. In light of this, we attempt to understand the perceptual point of departure for all three parties involved in the process of HL teaching/learning in an effort to later consider where and how converging of perspectives is needed, useful and possible. Doing so is timely, precisely because of the upswing in emerging programs at the university level designed specifically for HL bilinguals in the context of the United States (e.g. Beaudrie, 2012; Beaudrie, 2020). Should the goal of HL teaching be to fill in gaps or fix deficits, eradicating the differences that characterize HS grammatical knowledge from the prescriptive standard baseline? Can approaching HL education from such a perspective be true to its should-be neutrality on evaluating or (indirectly) promoting what constitutes a proper grammar?

It is important to highlight from the outset that our aim herein is not to converge on a singular approach to, or to make specific recommendations for the teaching of HLs per se. Rather, the goal is to provide a forum to acknowledge and appreciate the many voices involved in HL teaching/learning with a particular focus on how unpacking the answers to the questions in the survey sheds light on how more meaningful, successful and empathetic teaching/learning can begin to unfold. There are many steps to doing this and, to be sure, our efforts merely constitute a piece of the puzzle. It is, however, a foundational one to build responsible bridges between research and evidence-based practice informed by and in consideration of HSs’ perceptions and needs. In doing so, we maintain that this effort will also contribute to addressing and dispelling some myths that are particularly pertinent for those who teach HSs and also to HSs themselves.

Although we do not wish to enter too deeply into the lively discussion related to the so-called “appropriateness” of the HL variety in all domains of use, it should not be ignored. As Flores and Rosa (2015) put it, appropriateness-based approaches to HL teaching frame HSs’ linguistic practices as “deficient” regardless of how closely they follow supposed rules of appropriateness. We agree with the general tenets of those highlighting the myriad shortcomings and (unintentional) pitfalls of questioning the appropriateness of HL varieties in particular settings (e.g., Flores and Rosa, 2015), and argue that HL education should not be understood as a gap-filler, but rather as a unique case of supplemental native-language arts education. In such a light, understanding what HSs’ perspectives, attitudes and motivations for engaging in HL learning are, inclusive of unpacking the social forces that contribute to their perceptions, becomes all the more important (e.g., Clark et al., 1990; Clark et al., 1991).

In terms of linguistic competency, we know that monolingual adult grammars can vary considerably from prescriptive standard baselines depending on a host of several sociolinguistic variables, for example, socioeconomic status and literacy levels (e.g., Dąbrowska, 1997; Dąbrowska, 2012). It should not be surprising, therefore, that HSs also differ from the same prescriptive standard baselines to greater or lesser extents depending on a number of factors that include (but are not limited to) literacy exposure to the standard HL variety (Bayram et al., 2017; Kupisch and Rothman, 2018)1. In this particular regard, while we support a view where HL programs offer structured engagement with bilingual literacy skills that are additive, not subtractive or replacing to their coherent HL variety, we need to be cautious about the fact that our claims can legitimize an unintended promotion of some varieties over others. We align with others in suggesting that the point of departure for HL education in adulthood needs to take on similar pedagogical approaches as in predominantly “monolingual” societies where dialect variation exists on a large scale. For example, the remit of language education in the United States is not to replace African American Englishes for native speakers of these varieties. Such an approach respects the legitimacy of and linguistic completeness/complexity of “other” dialects, such as African American Englishes (Green, 2002; Delpit, 2006), while acknowledging the utility of acquiring the prescriptive standard variety while integrating language awareness with critical language skills. Viewing HL education in similar terms will aid educators and students in understanding and promoting the legitimacy of HL varieties and maximize time by avoiding attempts, if not ill-conceived temptation, to fix what is not broken in the first place.

In our view, there is an obvious need for understanding more precisely where there are overlaps and mismatches between what empirical research shows and the beliefs HSs and HL educators have regarding what a HL is, its development and outcomes, as well as what all this entails for the teaching of the HL in adulthood. The data we discuss below, therefore, focuses on beliefs and expectations of the three principle agents involved in this process; namely HL learners, HL educators, and HL researchers. To this end, a twofold aim was articulated as follows:

Aim 1: to understand their beliefs and attitudes towards the nature of bilingualism in general.

Aim 2: to understand their beliefs and attitudes towards the nature of HLB specifically, inclusive of their valuation of HS linguistic competence.

Methods

Participants

We collected data from 133 participants, all residing in the United States. They are diverse in terms of age, socioeconomic/education background and geographical location. There are three groups of participants: 90 HSs of Spanish (N = 69 females); 30 active educators of Spanish as a HL (N = 24 females); and 13 active researchers in the field of Spanish HL bilingualism (N = 8 females).

All HSs, aged between 18 and 28, were dominant bilingual speakers of American English. At the time of testing, they were enrolled in beginning to advanced Spanish classes that were part of a HL teaching program at a Southwestern university in the United States. Prior to enrolling in the HL program, which consists of a sequence of three semester-long courses combining linguistic and socio-culturally relevant content, the HSs reported having taken Spanish classes in programs designed for L2 learners for an average of 4.52 years (SD = 3.05).

All participants from the teacher group were active faculty members, aged between 26 and 69. Their employment spanned from elementary to university-level institutions across the United States (K-12-level N = 20, College-level N = 10). The average time of teaching HSs was 8.2 years (SD = 7.37). The participants from the researchers’ group, aged from 29 to 68, were recruited from different universities across the United States (Teaching-intensive institutions N = 5; Research-intensive institutions N = 8).

Our description of the data includes group and individual level analyses. We bring the data together comparatively as a first pass attempt to capture complementary perspectives towards understanding how various stakeholders perceive HL outcomes, the role of bespoke instruction in the prescriptive standard variety of the HL, and the valuation of bilingualism in general. The second pass hones in on the range of responses within each group and what these might reveal towards a more complete understanding of the same general questions.

Materials and Procedure

An online questionnaire was administered to obtain information from all three groups. The questions targeted information about attitudes towards bilingualism in general and more specifically, about HLB (see Online Questionnaire section for detailed description of the online questionnaire).

Online Questionnaire

There were a total of 13 items. Three questions sought to gather demographic information such as age, gender identity, and group membership (HS, educator or researcher) (Questions 1–3). Nine Likert-scale questions (scale of 0–10, where 0 represents strong disagreement and 10 strong agreement) were asked related to attitudes towards bilingualism in general and HLB more specifically. Questions, 4–7, related to bilingualism in general and were the following:

4. To me, a true bilingual is only really someone who is able to speak both languages equally well.

5. I think bilinguals are smarter than monolinguals.

6. To me, bilingualism should be the norm, in other words, as a society, we should aim to create opportunities for everyone to learn second languages and eventually become bilingual.

7. In my view, I see bilingualism as a positive thing which confers many advantages (i.e., access to culture, links to my heritage and family, better job opportunities, cognitive boosts).

Using the same Likert scale, Questions 8–12 assessed participants’ agreement or disagreement with statements related to attitudes towards HLB more specifically:

8. In my view, the linguistic needs of bilingual/heritage speakers are different from traditional second language learners and because of that bilingual/heritage speakers need to be provided with tailormade/specific language instruction in order to address their needs.

9. In my view, heritage speakers mix their languages (Spanish and English) when they speak as a strategy to compensate for their lack of linguistic knowledge in either of their two languages.

10. In your view, do you think it is important to promote native/home language maintenance among bilingual/heritage speakers?

11. In your view, how important is it for a heritage speaker to get good at grammar in order for their Spanish to sound more like a native speaker?

12. In my view, one goal of education for heritage speakers in Spanish via bilingual schools or in university classes should be to allow them to be able to stay in Spanish without having the need to switch back and forth to English and/or speak Spanish more correctly.

Finally, one open-ended question with unlimited space (13) was asked to afford an opportunity for participants to express their perceptions in their own words.

13. How would you describe, in general terms, the Spanish of the heritage speakers you have come across?

Procedure

We used Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) to administer the questionnaire. All participants completed it using their own devices. The HS group received course-credit for participating in the study. The participants from the educators and researchers’ groups were recruited via an online advertisement posted both on Twitter and Facebook. None of the participants from the educators or researchers’ groups received monetary compensation from participating in the study.

Results

Recall that Aim 1 was to: understand HSs, HL educators, and HL researchers’ beliefs and attitude towards the nature of bilingualism, and Aim 2 was to: understand HSs, HL educators, and HL researchers’ beliefs and attitude towards the nature of HLB and how they view the linguistic competence of HSs. With addressing these aims in mind, we describe the results of the questionnaire from all three groups: HSs, educators, and researchers.

Attitude Towards General Bilingualism

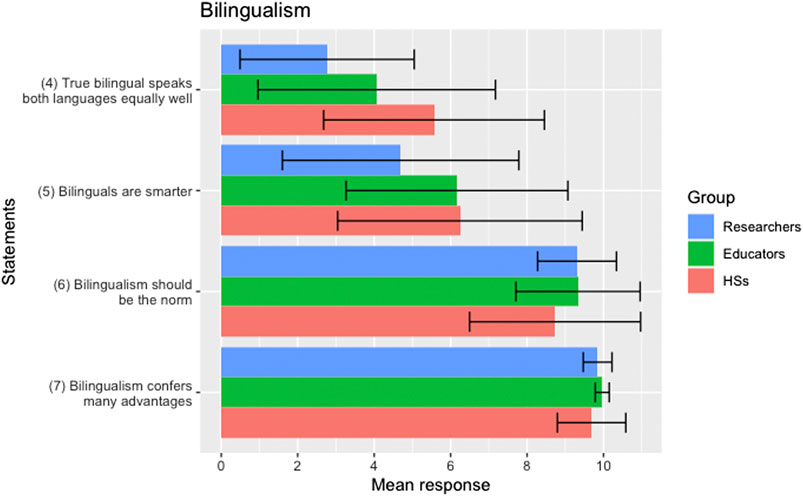

The participants’ average responses to questions/statements related to bilingualism in general (4–7 above) are summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Figure 1. The higher the mean response, the stronger the participants agreed to statements provided. We ran a Kruskal-Wallis H test to explore whether there are any significant differences in the responses among the three groups. We also ran pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon rank sum test to explore where the differences among the groups obtain.

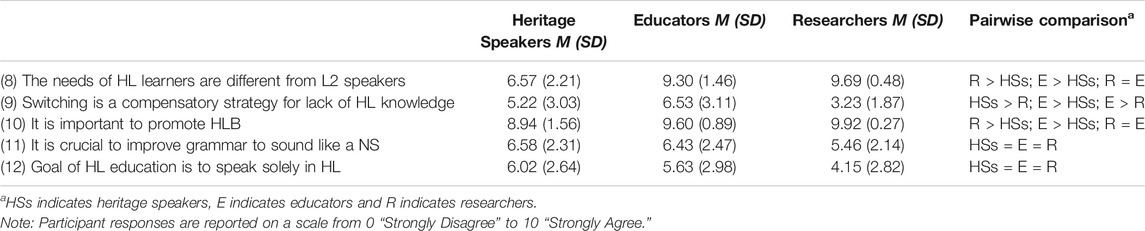

TABLE 1. Summary of the responses for questions related to bilingualism for HSs, educators, and researchers.

FIGURE 1. Summary of the responses for questions related to Bilingualism for HSs, Educators, and Researchers. Note: Participant responses are reported on a scale from 0 “Strongly Disagree” to 10 “Strongly Agree.”

As can be seen, all groups have a favorable view of bilingualism in general. In fact, they overwhelmingly agree that bilingualism can confer multifarious benefits (statement 7) and even consider that it should be the default norm (statement 6) in modern societies. The differences among groups are evident, however, in their responses to statement (4): To me, a true bilingual is only really someone who is able to speak both languages equally well. While it seems to be the case that HSs do not strongly agree nor disagree with this statement (M = 5.56), the educators slightly disagree (M = 4.06), and the researchers (M = 2.76) strongly disagree that one must speak both languages equally well to qualify as a true bilingual. Indeed, a Kruskal-Wallis H test showed that there was a statistically significant difference in responses among the groups for the statement (4) only, x2 (2) = 13.11, p = 0.001, with significant differences between HSs and researchers (p = 0.004) as well as HSs and educators (p = 0.03) but no differences between researchers and educators (p = 0.25).

It is not surprising that for statements (6) and (7) all groups were at near-ceiling in favor of bilingualism. After all, all participants in the current study live in an area in the United States where bilingualism—mainly in English and Spanish—is prevalent in their society where 21.6% of the relevant (over 63 million people) speaks a language other than English at home (United States Census Bureau's, 2019; Zeigler and Camarota, 2019). Moreover, as indicated by the low standard deviation, the responses to statements (6) and (7) are clustered around 7–10 (higher end of the scale) with little variability, indicating that there is a general consensus among all participants. Nevertheless, there is greater individual variability in the responses for (4) and (5), which is worth further consideration. For statement (5): I think bilinguals are smarter than monolinguals, HSs’ and educators’ average responses are 6.24 and 6.16 respectively. While they do not consider HSs as “less” than the monolinguals in regard to their overall intelligence, the clustering of responses around the middle ground shows that they have a reasonable gauge on the confines of bilingualism.

Interestingly, the only question that elicited a difference in evaluation among the groups was (4). HSs believed more strongly, on average, that to be a true bilingual, one must speak both languages equally well. Qualitatively, we can see that there is a wide range of responses among the HSs—while 10 out of 90 participants responded that they completely agree with this statement (i.e., response of 10), six out of 90 responded that they completely disagree with this statement (i.e., response of 1). Such bundles at the extreme ends of the spectrum are not prevalent in the responses of educators (e.g., only 2 out of 30 educators completely agreed) and such an evaluation is completely lacking for the researchers.

Not least given the admitted fluidity of what any given individual could take to be “a true bilingual” and/or “equally well” coupled with differences by virtue of training in how the groups are likely to understand the constructs that underlie such a statement, it is not surprising that statement (4) displayed such variation. To be sure, researchers who study bilingualism are more likely to have a more prescribed academic approach to such statements, as it pertains directly to their object of scientific inquiry. Alternatively, HSs are more likely to understand this statement from a view that reflects lay societal norms and attitudes. When we consider the upper quartile of possible responses (8–10 on the Likert-scale), we can appreciate more dramatic distinctions. Whereas 29% of the HSs offered scores between 8 and 10, this was the case for only 18% of educators and 0% of researchers. This difference could be understood to indicate various things. Firstly, because a lack of balanced bilingualism is a hallmark of HL competence, this could be taken to reflect a perception on the part of nearly a third of the HSs surveyed that they consider themselves or other HSs as being not truly bilingual. Moreover, the fact that at least some educators seem to agree with this is food for thought and caution, considering that the bilinguals with which they are responsible to work with would fall outside of what they consider to be “properly” bilingual. Finally, the fact that no researcher shares such a perspective already underscores the potential disconnect between research and the real world, potentially highlighting that what we as researchers mean to convey is not exactly how the stakeholders of our research understand it (Pascual y Cabo and Rothman, 2012; Kupisch and Rothman, 2018).

Attitudes Towards Heritage Language Bilingualism

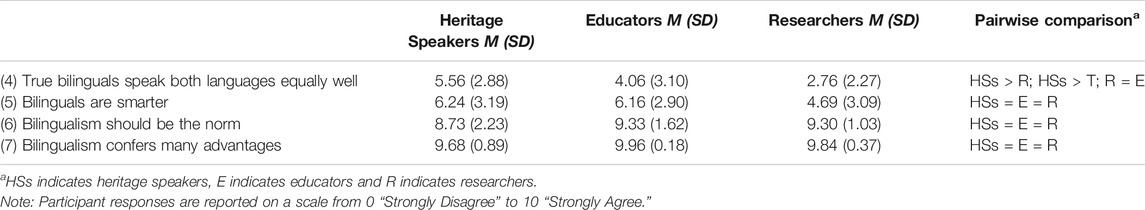

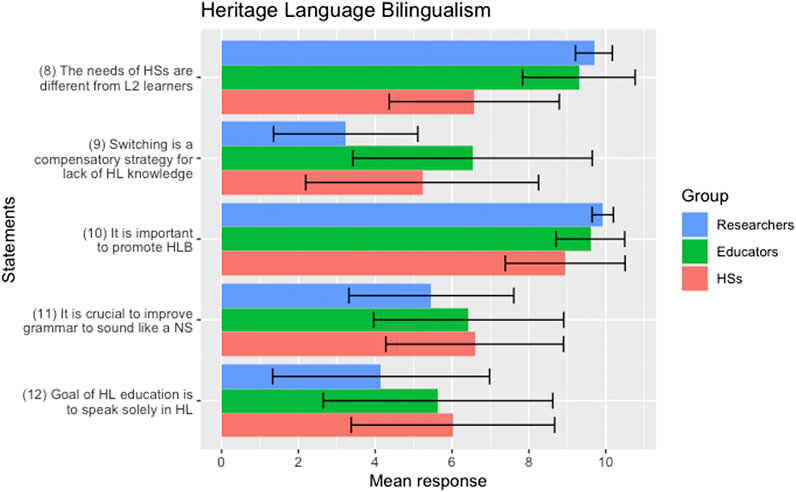

The participants’ average responses to statements (8)–(12) are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 2 above.

FIGURE 2. Summary of the responses for questions related to HLB for HSs, Educators, and Researchers. Note: Participant responses are reported on a scale from 0 “Strongly Disagree” to 10 “Strongly Agree.”

The bar graph in Figure 2 illustrates that all groups responded similarly to statement (12): In my view, one goal of education for HSs in Spanish via bilingual schools or in university classes should be to allow them to be able to stay in Spanish without having the need to switch back and forth to English and/or speak Spanish more correctly, and to question (11): In your view, how important is it for a heritage speaker to get good at grammar in order for their Spanish to sound more like a native speaker? That is, all groups appear to not have any strong opinions towards either of these, as the mean responses to both cluster around the middle (range 4.15–6.58). This result is also backed up in the statistics—a Kruskal-Wallis H test showed that there were no statistically significant differences in responses among the groups for statement (12), x2 (2) = 4.78., p = 0.09, as well as statement (11), x2 (2) = 3.17., p = 0.20. Although the responses show no polarization in the direction that would indicate unambiguous opposition to statements that are both evaluative and prescriptive in nature, the fact that no group shows agreement to any degree with the implications of such statements suggests a tacit rejection of purely normative views. While we might have expected researchers in particular to demonstrate sharper aversion to such statements, we must keep in mind that researchers are also individuals that live in societies where these views are commonly held and not readily perceived as negative statements. As such, neutrality to them might be viewed as opposition to the implicit valuation such statements entail without commitment to rejecting outright a view commonly held.

In contrast, there is a stark difference in responses among the three groups for the following questions/statements: (10) In your view, do you think it is important to promote native/home language maintenance among bilingual/heritage speakers?, x2 (2) = 9,03., p = 0.01, (9) In my view, heritage speakers mix their languages (Spanish and English) when they speak as a strategy to compensate for their lack of linguistic knowledge in either of their two languages., x2 (2) = 10.76., p = 0.004, and (8) In my view, the linguistic needs of bilingual/heritage speakers are different from traditional second language learners and because of that bilingual/heritage speakers need to be provided with tailormade/specific language instruction in order to address their needs., x2 (2) = 47.81., p < 0.001. For both statements (8) and (10), there are no significant differences in responses between the researchers and the educators, but we see a clear difference between HSs and researchers (p’s < 0.05) as well as HSs and educators (p’s < 0.05). In other words, educators and researchers who work closely with HSs appear to appreciate more the importance of HLB education and the special needs of HSs than the HSs themselves. It is interesting to note here that although the responses of HSs in regard to question (8) are reflected positively (mean = 6.57), the value that appears most frequently is in fact “5” (23/90 participants). The fact that many HSs opted for choosing the most “neutral” response may be a result of their uncertainty in understanding what the needs of HSs relative to L2 learners are and what kind of differential support is required. If on the right track, this is particularly interesting. Obviously, HSs know that traditional L2 learners are two things: 1) not native speakers of the given language and 2) adult learners in need of support to acquire/learn the target language. If (some) HSs do not functionally distinguish themselves from L2 learners, it might indicate two things: they do not recognize their own nativeness in the HL and they view that, like L2 learners, their task is to acquire a particular variety for which they need equivalent guidance. Researchers and educators, on the other hand, seem to have a rather unified idea of the distinction between L2 speakers and HSs, stressing that the types of linguistic support that these two groups require are indeed different. For instance, only 2/30 educators responded “5” to question (8), while no responses under “9” were observed for the researchers. Of course, this is not surprising given that educators and researchers are formally trained in not only language pedagogy, but also in theories of bilingualism, whereby fundamental differences between native language acquisition (as in the case of HSs) and second language learning (as in the case of L2 learners) are introduced.

In regards to question (10), although many HSs completely agree that it is important for HLB to be promoted (54/90), the standard deviation of their responses (SD = 1.56) is much higher than the educators’ (SD = 0.89) and the researchers’ (SD = 0.27), indicating a larger spread in their data. As seen in their homogenous responses, none of the educators or researchers chose a value below 7 (which is still very much towards the positive spectrum on the scale). In contrast, some HSs surprisingly chose a value as low as 4, which sits at the negative end of the spectrum. This indicates a varying understanding of the potential societal values of HLB among the HSs themselves. Less neutrally put, it seems reasonable to understand their answers as a byproduct reflection of the sum total of their actual experiences of being a HS. Notwithstanding this practical experience, at least for some, a positive outlook on the utility/benefits of HLB has not developed. Upon reflection, it is rather disappointing and revealing that HSs, even after participating in a language program specifically tailored to serve their specific needs, still hold such mixed views. While it is rather gratifying to see that both educators and researchers believe that HLB is worthy of promotion, something is clearly lost in transmission. Ultimately, it seems more important that the target group should understand the value of their own experience more than those that study it as an academic observation. How, if not why, this is being lost in transmission is worthy of serious consideration, to which we return in the discussion.

The only difference that was found in the responses between educators and researchers was in regards to statement (9): In my view, heritage speakers mix their languages (Spanish and English) when they speak as a strategy to compensate for their lack of linguistic knowledge in either of their two languages. The educators agreed more strongly to this statement than the researchers (p = 0.005), suggesting that educators view language switching in classrooms as more or less a behavior that stems from not having sufficient HL competence in the HL. This is not terribly surprising, given that such a view can seem intuitive and there have been studies suggesting as much (e.g., McClure, 1981). The stigmatization of code-switching as “deficient” behavior has itself undergone a major conceptual shift within the relevant literature (Klimpfinger, 2009). There is now a general consensus among researchers that code-switching is a creative manifestation of bilingual practices that facilitates communication, learning, and especially social interactions and group/peer inclusion (e.g., Poplack, 2000; Romaine, 2001; Toribio, 2002; Söderberg Arnfast and Jørgensen, 2003; Macaro, 2006; García and Wei, 2014; Wei, 2018). Moreover, upon careful consideration code-switching practices, especially beyond the lexicon, actually reflect high levels of representational knowledge and sophistication in both languages (Jake and Myers-Scotton, 1997; MacSwan, 2000; López et al., 2017; Couto et al., 2019). The responses of the educators went above and beyond our initial expectation for their potential conservatism in this respect. It is worth noting that they agreed more strongly to statement (9) than the HSs themselves, who, we surmised, would be more likely to arrive at such an opinion given their tangible experiences of having been directly and indirectly told this over their lifespan. The view of the educators clearly reflects more a subjective opinion rather than fact, influenced from monolingual normative biases. The immediate concern this should evoke is not to be understated, considering these are the very same people who interact with and have influence over HSs in a learning setting (as opposed to researchers who are mostly observers). After all, opinions shape practice. And so, regardless of otherwise well intentions, there is little doubt that such an underlying opinion has consequences in how they approach the goals and their own undertaking of HL teaching. As such, and given their answers to other questions, there are some incompatibilities within their own views. Whereas they see the clear value of bilingualism and are consciously aware that HLB is worthy of fostering, such awareness does not entail continuity in how this should play out across the board. Understandably, influencing societal norms affect intuitions/opinions, which become hard habits to break.

Open-Ended Questions

As indicated in Online Questionnaire, participants were asked to answer the following open-ended question: “How would you describe the Spanish of the HSs you have come across?”. We asked this question in an open-response format to provide an opportunity for participants to freely express their views. Obviously, we cannot examine in depth all responses, nor apply any type of statistical treatment for this type of question. Instead, we believe it to be fruitful to present some authentic responses verbatim and present these thematically as we saw trends in the responses.

Variable Outcomes

The HSs often described the Spanish competence of other HSs as either “good” or “bad” such as:

“They speak it really well and fluently.” (Hispanic, HS in their second semester of the HL program, Intermediate proficiency (DELE score = 36), 10 years of past formal Spanish education)

“Terrible, no one (even) speaks Spanish in a Spanish class.” (Hispanic, HS in their first semester of the HL program, Intermediate proficiency (DELE score = 25), 5 years of past formal Spanish education).

Some HSs, however, acknowledged that the competence of the HL varies vastly among speakers:

“They all vary on how they were brought up by their family.” (Hispanic, HS in their second semester of the HL program, Low to intermediate proficiency (DELE score = 23), 4 years of past formal Spanish education).

“Everyone has different levels of comprehension and I respect anyone who attempts to learn a second language.” (Hispanic, HS in their second semester of the HL program, Intermediate proficiency (DELE score = 20), 2 years of past formal Spanish education).

However, this notion of varied linguistic competence in HSs was more often emphasized by the educators and researchers as follows:

“I would describe it as its own variety of Spanish, probably the most heterogeneous.” (Educator at the College level, 0.5 years of experience in teaching HSs).

“I work (both as a researcher and as a teacher) with HSs that have very different levels of linguistic proficiency: I have worked with speakers who merely have a receptive knowledge of the language, and with others that exhibit a high level of fluency and grammatical accuracy.” (Educator at the College level, 7 years of experience in teaching HSs)

“I work mainly with K-2 students, some are at native-like abilities for their age, others struggle to converse completely in Spanish and generally speak more English than Spanish. There is a wide mix of language abilities.” (Educator at the K-12 level, 3 years of experience in teaching HSs).

“It's varied in terms of language reception and production. It is hard to label heritage bilingual speakers because they have multiple levels of linguistic production” (Researcher at Research-intensive institution).

Taken together, all groups seem to understand and acknowledge that individual differences in language competence is a hallmark of the HS continuum, but the researcher, and especially the educator, appear to particularly highlight this notion in their responses. Obviously, this is an expected response from the educators, who regularly communicate with HSs and witness firsthand their diverse background and linguistic competence. This observation is also in line with responses from questions about bilingualism in section 3.2.1. While the educators and researchers appear to be highly aware of the various needs and outcomes of HSs, HSs themselves show a tendency to categorically evaluate linguistic competence in relatively binary terms (e.g., use of words such as “good” or “bad”). What is unclear, however, is what participants have in mind as a baseline against which they are assessing perceived outcomes. In any case, what all this points to, with few exceptions (e.g., “its own variety of Spanish”), is a shared belief that there is binarity of right and wrong, correct and incorrect or, at least, more prestigious and normative. While mere observation of HSs alone would show that there is veracity in many of the statements in their most neutral interpretation (e.g., that there are high degrees of various and production/comprehension asymmetries), the way in which these observations are expressed leaves little doubt that evaluative assessment is ascribed to the observation of variation. This same trend is also evident in the Likert-scale questionnaire results, as illustrated by the clustering of responses towards both extreme ends of the scale in statement (4), whereby HSs were more likely to define a “true” bilingual as someone who speaks both languages equally well.

We would also like to draw attention to a quote by a HS who had just completed their second consecutive semester in the HL program: “Everyone has different levels of comprehension and I respect anyone who attempts to learn a second language.” Such a comment further highlights the results of the questionnaire reported earlier, in which the HS group responded least favorably to statement (e): The needs of HL are different from L2 speakers.” The fact that this HS described the Spanish of the HSs as “a second language” goes to show that some HSs have the idea that their home language is somehow a second (or non-native) language, because they confuse dominance and/or achieving the normative grammar as a qualifier of nativeness, a fallacy that also underscores much research in the area of HLB as well (Rothman and Treffers-Daller, 2014).

Language Register

The striking difference between the HSs and the educators as well as researchers is the term they used to describe the language register of HSs. For example, one of the HSs responded as follows:

“My parents learned it at home and in school. So (their Spanish is) a combination of broken and academic” (Hispanic, HS in their first semester of the HL program, Low proficiency (DELE score = 22, 2 years of past formal Spanish education)

Another HS also used the term “broken” to describe the language of Spanish HSs:

“I think the Spanish of the heritage bilingual speakers I have come in contact with is a little broken but able to be understood.” (Hispanic, HS in their first semester of the HL program, Low proficiency (DELE score = 18), 4 years of past formal Spanish education).

Others used the term “slang” to illustrate the language register that HSs often use:

“They talk in slang terms.” (Hispanic, HS in their first semester of the HL program, Low proficiency (DELE score = 13), 4 years of past formal Spanish education).

“Spanglish and many Mexican slang as well as sprinkles of Puerto Rican slang.” (Hispanic, HS in their first semester of the HL program, Intermediate proficiency (DELE score = 25), Less than a year of past formal Spanish education).

“Very good but with slang.” (Hispanic, HS in their second semester of the HL program, High proficiency (DELE score = 37), 7 years of past formal Spanish education).

It is important to note here that the terms that carry negative connotations used by the HSs—such as “broken” or “slang”—were never used by the educators or the researchers. Instead, they tended to use terms such as “informal” or “conversational” to outline the language register that HSs often use:

“An informal way of speaking Spanish, as in how they speak to friends. They have a hard time with more academic language and a much more difficult time writing without many errors and reading more difficult texts. They can speak really well but need help with other aspects.”

(Educator at the K-12 level, 3 years of experience in teaching HSs).

“They can speak in an informal register. Can't read or write according to their age.” (Educator at the College level, 1 year of experience in teaching HSs).

“Not a lot of familiarity with formal vocabulary in different social domains (education, professional life, etc). Sometimes misuse of grammatical gender, subjunctive, past tenses (preterite and imperfect) but nothing that can be extremely confusing when communicating with someone who was monolingually-raised in the heritage language.” (Researcher at Teaching-intensive institution).

The terminology used by the HSs to describe their own linguistic competence, such as “broken” or “slang,” is most likely influenced by their conscious or unconscious perception that there is something wrong with their grammar and that it should somehow be fixed. Perceptions do not emerge out of the blue, they are a byproduct of relevant experience. As such, the stark difference amongst HSs and the other groups are all the more illuminating, if not thought provoking. It is a shame that HSs should associate words like “broken” with the knowledge they have of their native language, when what they really mean to convey is awareness of the differences they display juxtaposed against a comparison (most likely the illusive monolingual) to which they are not really comparable in the relevant ways. As it would be untenable to compare the competence of a speaker of a specific American English dialect to a speaker of prescriptive standard British English, it does not make better sense to do the same implicitly between HSs and an illusive norm or even across other HSs. Why? Because just like in the case of comparing American to British Englishes, the potential for convergence on a variety to which one was not exposed is nonsensical. The levels of variation, especially in the absence of schooling in a particular prescriptive standard variety at a young age, which defines the experience of a majority of monolinguals, in quality and quantity of input, community size and a myriad of other factors that delimit opportunities for language use that pertain to HS individuals render such a comparison futile from the outset.

Discussion

Throughout this article we have documented the perceptions of and the narratives embraced not only by researchers and educators in the area of HLB, but also by the HSs themselves. While the scope, interests and primary concerns will naturally differ from group to group, uncontroversially, we are all committed to better our understanding of the all-encompassing (linguistic and socio-affective) nature of HLB so as to achieve a higher degree of bilingual and biliteracy development.

Our point of departure was the idea that despite sharing such noble common goals, there is a real pragmatic disconnect between said groups and that failing to recognize this runs the risk of impeding the shared objective. In our attempt to contextualize the disconnect, we have underscored some of the negative consequences that may stem from how HLB has been generally framed historically in the literature and, despite calling attention to it, remains (unconsciously) entrenched still. For example, in a top-down fashion, as is the standard way of proceeding from research to teaching and to learning, some of the labels that have been used to describe HLs and its speakers are, at the very least, unhelpful (e.g., incomplete, imperfect, broken, semi-speakers). While not originally intended to be evaluative or judgmental, these are loaded terms and their meanings—no matter the intention or perspective—are open for interpretation. Ultimately, this creates a situation in which nobody wins; particularly HL learners since they are the most vulnerable and affected group, but also educators and researchers for whom the starting point of framed conceptualization delimits their intended goals. With this in mind, returning now to a point we made earlier, the most crucial consequences are the ones that trickle down. Limitations to questionnaire aside, both our quantitative and qualitative data show some evidence of this. While admittedly we did not find striking differences between the three groups, we have identified some trends that are worth noting. For example, researchers’ answers show a general sense of alignment with best and most up-to-date academic and pedagogic practices. That said, it is important to mention that knowing this at the research level does not necessarily entail that the message has or will ever universally trickle down to key stakeholders such as policy makers, educators, parents and the like. As the reasons for this are very dynamic and multifarious, it is not our intention to pioneer a change therein, but to highlight it as a maximally relevant example of the disconnect more generally between research and practice in HL contexts. On the one hand, educators’ answers reveal that they are aware of the heterogeneity that defines HL learners and that, to some extent they understand and acknowledge that individual differences will have an effect on their students’ linguistic competence. On the other hand, they also show signs of antiquated teaching practices, such as the misnomer that HL learners make use of translingual practices as a compensatory strategy or that the goal of HL education is to stay on target 100% of the time (whatever that target should be aside). This is important because, in many HLB contexts, such as Spanish HL learners in the United States, HL learners often endure disenfranchisement, neglect and even hostility when those in charge do not have the training nor the experience necessary to provide them with optimal educational experiences.

The HL learners’ responses to the open-ended question reveal both the imbalance but also the consequences of the societally mis-guided perceptions of their HL. Their use of words such as “broken”, “slang” or “terrible” to describe their own linguistic systems indicates that they are not immune to political discourses (and other social forces) that delegitimize immigrant/minority languages/cultures and to the internalization of prejudiced assimilative-ideologies in the face of the prevalent (American) monolingualism/monoculturalism. That their educators may be (un)consciously contributing to this problem instead of increasing awareness to stop it, is certainly disconcerting. Considering this, the present work provides a lens through which this issue can be acknowledged and, accordingly, foster motivation to enable all stakeholders to participate in dialogue to move toward a productive outcome for all involved. To be sure, in many ways, this is already happening. Efforts to increase collaboration and communication between researchers, educators and the general audience can be seen in international research organizations and information centers. That said, to be maximally efficient, we ought to create additional educational spaces that allow for a greater understanding of the dynamics that are distinctive to HLs, its speakers, and the relationship that exists between them, particularly with regards to its potential consequences that these may have for HLs and their speakers.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Texas Tech University. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

FB Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing. MK Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing. AL Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Data Processing, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing, Project administration. DP Writing - review and editing. JR Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review and editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Funding

This work was partially funded by grants from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No 799652; and the Tromsø Forskningsstiftelse (TFS) Starting Grant (2019–2023).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students, educators, and reserchers who participated in this study. In addition, we would like to thank the instructors in the Spanish Program for Heritage Bilingual Speakers at Texas Tech University, specifically Yerko Sepúlveda, Gema López-Hevia, Cecilia Palacio-Ribón, Verónica Morales, Omar González, and Sylvia Flores, for their support in facilitating part of the data collection effort for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1As has been pointed out in recent work (e.g., Kasstan et al., 2018; Aalberse et al., 2019), it should follow that much of the noted HS individual variation can, at least in part, be explained in sociolinguistic terms. Indeed, the study of language variation, contact and change as influenced by social factors offers great promise for illuminating key factors contributing to how and why HLB reports such a wide spectrum of individual differences while providing a theoretical backdrop to make sense of, if not predict, apparent individual differences. Of course, some properties within heritage grammars tend to be significantly less susceptible to, if at all, individual variation across HSs, even when the HS grammar differs from that of monolinguals and independent of social factors. For such properties, formal, cognitive based linguistic approaches to language are seemingly in a privileged position to explain HS-monolingual distinct outcomes and even predict their probability of occurence (Lohndal et al., 2019; Polinsky and Scontras, 2020). In our view, any complete understanding of HLB must include a combination of sociolinguistic insights and theory alongside theories that focus more on the cognitive side of grammatical representions and processing in the mind. As the focus of the current paper, however, is not on trying to explain this, we leave this discussion for other venues.

References

Aalberse, S., Bauckus, A., and Muysken, P. (2019). Heritage languages: a language contact approach. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/sibil.58

Bayram, F., Kupisch, T., Pascual y Cabo, D., and Rothman, J. (2019). Terminology matters on theoretical grounds too!: Coherent grammars cannot be incomplete. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 41(2), 257–264. doi:10.1017/s0272263119000287

Bayram, F., Rothman, J., Iverson, M., Kupisch, T., Miller, D., Puig-Mayenco, E., et al. (2017). Differences in use without deficiencies in competence: passives in the Turkish and German of Turkish heritage speakers in Germany. Int. J. Bilingual Education Bilingualism 22, 919–939. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1324403

Beaudrie, S. M. (2020). Towards growth for Spanish heritage programs in the United States: key markers of success. Foreign Lang. Ann. 53 (3), 416–437. doi:10.1111/flan.12476

Bialystok, E. (2017). The bilingual adaptation: how minds accommodate experience. Psychol. Bull. 143, 233. doi:10.1037/bul0000099 |

Bousquette, J., and Putnam, M. T. (2020). Redefining language death: evidence from moribund grammers. Lang. Learn. 70, 185–228. doi:10.1111/lang.12362

Carreira, M., and Beeman, T. (2014). Voces: Latino students on life in the United States. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Chevrot, J., and Foulkes, P. (2013). Introduction: language acquisition and sociolinguistic variation. Linguistics 51 (2), 251–254. doi:10.1515/ling-2013-0010

Clark, R., Fairclough, N., Ivanič, R., and Martin‐Jones, M. (1990). Critical language awareness part I: a critical review of three current approaches to language awareness. Lang. Education 4 (4), 249–260. doi:10.1080/09500789009541291

Clark, R., Fairclough, N., Ivanič, R., and Martin‐Jones, M. (1991). Critical language awareness1part II: towards critical alternatives. Lang. Education 5 (1), 41–54. doi:10.1080/09500789109541298

Couto, P. M. C., and Gullberg, M. (2019). Code-switching within the noun phrase: evidence from three corpora. Int. J. Bilingualism 23 (2), 695–714. doi:10.1177/1367006917729543

Delpit, L. (2006). “What should teachers do?,” in Ebonics and culturally responsive instruction. Editor S. J. Nero (New York, USA/London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum), 93–101.

Domínguez, L., Hicks, G., and Slabakova, R. (2019). Terminology choice in generative acquisition research. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis 41 (2), 241–255. doi:10.1017/s0272263119000160

Ducar, C. M. (2008). Student voices: the missing link in the Spanish heritage language debate. Foreign Lang. Ann. 41 (3), 415–433. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2008.tb03305.x

Dąbrowska, E. (2012). Different speakers, different grammars: individual differences in native language attainment. Linguist. Approaches Bilingualism 2 (3), 219–253. doi:10.1075/lab.2.3.01dab

Dąbrowska, E. (1997). The LAD goes to school: a cautionary tale for nativists. Linguistics 35 (4), 735–766. doi:10.1515/ling.1997.35.4.735

Ennser-Kananen, J., and King, K. A. (2018). Heritage languages and language policy, in The Encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Editor C. A. Chapelle. doi:10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0500.pub2

Flores, N., and Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 85 (2), 149–171. doi:10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149

García, O., and Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: language, bilingualism and education. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 46–62.

Goodenough, F. L. (1926). Racial differences in the intelligence of school children. J. Exp. Psychol. 9 (5), 388–397. doi:10.1037/h0073325

Green, L. J. (2002). African American English: a linguistic introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Grosjean, F. (2019). A journey in languages and cultures: The life of a bicultural bilingual. Newyork, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198754947.001.0001

Grosjean, F. (1998). Studying bilinguals: methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism 1 (2), 131–149. doi:10.1017/s136672899800025x

N. H. Hornberger, and S. L. McKay (Editors) (2010). Sociolinguistics and language education. Bristol, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

Jake, J. L., and Myers-Scotton, C. (1997). Codeswitching and compromise strategies: implications for lexical structure. Int. J. Bilingualism 1 (1), 25–39. doi:10.1177/136700699700100103

Kasstan, J. R., Auer, A., and Salmons, J. (2018). Heritage-language speakers: theoretical and empirical challenges on sociolinguistic attitudes and prestige. Int. J. Bilingualism 22, 387–394. doi:10.1177/1367006918762151

Klimpfinger, T. (2009). “She’s mixing the two languages together” – forms and functions of code-switching in English as a Lingua Franca,” in English as a Lingua Franca: Studies and Findings. Editors A. Mauranen and E. Ranta (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 348–371.

Krashen, S. (1998). ”Language shyness and heritage language development,” in Heritage language development. Editors S. Krashen, L. Tse, and J. McQuillan (Culver City, CA: Language Education Associates), 41–49.

Kupisch, T., and Rothman, J. (2018). Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. Int. J. Bilingualism 22 (5), 564–582. doi:10.1177/1367006916654355

Leivada, E., Westergaard, M., Duñabeitia, J. A., and Rothman, J. (2020). On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition:(How) should we proceed? Bilingualism: Lang. Cogn. 24, 1–14. doi:10.1017/S1366728920000358

Lohndal, T., Rothman, J., Kupisch, T., and Westergaard, M. (2019). Heritage language acquisition: what it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Lang. Linguist Compass 13 (12), e12357. doi:10.1111/lnc3.12357

López, L., Alexiadou, A., and Veenstra, T. (2017). Code-switching by phase. Languages 2 (3), 9. doi:10.3390/languages2030009

Macaro, E. (2006). ”Codeswitching in the L2 classroom: a communication and learning strategy,” in Non-native language teachers. Perceptions, challenges and contributions to the profession. Editor E. Llurda (New York, NY: Springer), 63–84.

MacSwan, J. (2000). The architecture of the bilingual language faculty: evidence from intrasentential code switching. Bilingualism 3 (1), 37–54. doi:10.1017/s1366728900000122

McClure, C. R. (1981). Indexing U.S. Government periodicals: analysis and comments. Latino Lang. communicative Behav. 6, 69–84. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-025216-2.50011-9

Montrul, S. (2016). The acquisition of heritage languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Montrul, S. (2008). Review article: second language acquisition welcomes the heritage language learner: opportunities of a new field. Second Lang. Res. 24 (4), 487–506. doi:10.1177/0267658308095738

Beaudrie, S. M. (2012). “Research on university-based Spanish heritage language programs in the United States: the current state of affairs,” in Spanish as a heritage language in the United States: the state of the field. Editors Fairclough, M. A., and Beaudrie, S. M. (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 203–221.

Pascual y Cabo, D., and Rothman, J. (2012). The (il) logical problem of heritage speaker bilingualism and incomplete acquisition. Appl. linguistics 33 (4), 450–455. doi:10.1093/applin/ams037

Peal, E., and Lambert, W. E. (1962). The relation of bilingualism to intelligence. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 76 (27), 1–23. doi:10.1037/h0093840

Polinsky, M. (2008). Gender under incomplete acquisition: heritage speakers’ knowledge of noun categorization. Herit. Lang. J. 6, 40–71.

Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, Vol. 159.

Polinsky, M., and Scontras, G. (2020). A roadmap for heritage language research. Bilingualism 23 (1), 50–55. doi:10.1017/s1366728919000555

Poplack, S. (2000). Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en español: toward a typology of code-switching. Bilingualism Read. 18 (2), 221–256. doi:10.1515/ling.1980.18.7-8.581

Putnam, M. T., Kupisch, T., and Pascual y Cabo, D., (2018). “Different situations, similar outcomes: heritage grammars across the lifespan,” in Bilingual cognition and language: the state of the science across its subfields. Editors F. Bayram, N. Denhovska, D. Miller, J. Rothman, and L. Serratrice (Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins), 251–279.

Rothman, J., and Treffers-Daller, J. (2014). A prolegomenon to the construct of the native speaker: heritage speaker bilinguals are natives too!. Appl. linguistics 35 (1), 93–98. doi:10.1093/applin/amt049

Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: romance languages as heritage languages. Int. J. Bilingualism 13 (2), 155–163. doi:10.1177/1367006909339814

Saer, D. J. (1923). The effect of bilingualism on intelligence. Br. J. Psychol. Gen. Section 14, 25–38. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1923.tb00110.x

Silva-Corvalán, C. (2014). Bilingual language acquisition: Spanish and English in the first six years. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Silva-Corvalán, C. (2018). Simultaneous bilingualism: early developments, incomplete later outcomes? Int. J. Bilingualism 22 (5), 497–512. doi:10.1177/1367006916652061

Söderberg Arnfast, J., and Jorgensen, J. N. (2003). Code-switching as a communication, learning, and social negotiation strategy in first-year learners of Danish. Int. J. Appl. Linguistics 13 (1), 23–53. doi:10.1111/1473-4192.00036

Tagliamonte, S. A. (2012). Roots of English: Exploring the history of dialects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Toribio, A. J. (2002). Spanish-English code-switching among US Latinos. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2002 (158), 89–119. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2002.053

United States Census Bureau (2019). 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) Language Spoken at Home 1-year estimates. Avialable at: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Language%20Spoken%20at%20Home&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1601&hidePreview=false.

Vergara Wilson, D., and Pascual y Cabo, D. (2019). Linguistic diversity and student voice: the case of Spanish as a heritage language. J. Spanish Lang. Teach. 6 (2), 170–181. doi:10.1080/23247797.2019.1681639

Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl. Linguistics 39 (1), 9–30. doi:10.1093/applin/amx039

Keywords: heritage language bilingualism, heritage speakers, heritage language education, attitude, beliefs

Citation: Bayram F, Kubota M, Luque A, Pascual y Cabo D and Rothman J (2021) You Can’t Fix What Is Not Broken: Contextualizing the Imbalance of Perceptions About Heritage Language Bilingualism. Front. Educ. 6:628311. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.628311

Received: 11 November 2020; Accepted: 12 February 2021;

Published: 29 April 2021.

Edited by:

Roumyana Slabakova, University of Southampton, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mike Putnam, Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesGlaucia Silva, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, United States

Suzanne Aalberse, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Bayram, Kubota, Luque, Pascual y Cabo and Rothman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jason Rothman, jason.rothman@uit.no

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share co-first authorship

Fatih Bayram

Fatih Bayram Maki Kubota1†

Maki Kubota1†  Alicia Luque

Alicia Luque Diego Pascual y Cabo

Diego Pascual y Cabo Jason Rothman

Jason Rothman