Good teaching—The adaptive balance between compulsion and freedom

- Department of Education and Rehabilitation, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

What is good teaching? This question is as old as people have reflected on this topic, and its answers in the European context date back to antiquity. This essay elaborates on and justifies one complex answer to the question: good teaching is the adaptive balance between compulsion and freedom. The key questions addressed by the essay are as follows: (1) What arguments favor teaching within a framework of compulsion and what arguments favor teaching in a framework of freedom? (2) How can these possibilities be reconciled? (3) Does a myth of good teaching derive from these possibilities? To answer these questions, we first examine the different dimensions related to good teaching in science and other domains of life. We then develop criteria for defining compulsion and freedom in the context of teaching. This is followed by depicting arguments for organizing teaching in a framework of compulsion and those for organizing teaching in a framework of freedom. The thesis (compulsion) and antithesis (freedom) are then synthesized by constructing a concept of a balance between both positions according to the ideas of philosophy, sociology, theories of education, and learning theory. Therefore, the basic approach of this essay is dialectical. We select big ideas, confront them against each other, and attempt to find a synthesis without any claim to the historical completeness or completeness of concepts. Based on history, we emphasize the idea that, from the time of enlightment to modern learning theories, similar lines of arguments support each other.

Introduction

What is good teaching? This question is as old as people have reflected on this topic. Answers to this question in the European context date back to antiquity. Here, we elaborate on and justify one complex answer to this question: good teaching is the adaptive balance between compulsion and freedom. We start by examining different dimensions of good teaching and developing criteria for defining compulsion and freedom in the context of teaching. We then offer arguments for organizing teaching within the framework of compulsion versus the framework of freedom. The thesis and antithesis are then synthesized into a concept that balances both positions according to ideas of philosophy, sociology, theories of education, and learning theory. Comparatively, we show how arguments from very different contexts and countries support each other. Using a historic basis, we put an emphasis on the idea that from the time of enlightment to modern learning theories, similar lines of arguments can be detected.

Dimensions of good teaching

The answers to the question of good teaching since antique philosophy in Greece until now have circled around a few dimensions. Accordingly, good teaching relates to many different domains not only of science, but also of domains and beliefs of our life. We find references to:

• Societal demands: For example, Socrates was killed in Athens because his false teaching was supposedly spoiling the youth (Plato, 2017). Socrates was accused of not having sufficiently reflected societal demands.

• Institutional demands: For example, American instructional design was originally developed to improve instruction for soldiers in order to make them more effective warriors (Richey, 1992). Instructional design later was adopted in schools; thus, Gagné’s famous “Conditions of Human Learning” was initially a military handbook.

• Religious demands: For example, content to be taught is rejected, because it does not comply with religious norms, as it is for some people the case with evolution theory (Smith et al., 1995).

• Belief systems beyond religion, such as gender: For example, content and interaction have to represent diversity (Bell et al., 2017).

• Inclusion according to the UN Disability Rights Convention (United Nations, 2006).

• Meeting learners’ needs and prerequisites (Helmke, 2017).

• Selection of content or the structure of content is usually considered the base of teaching objectives (Klafki, 2007).

• Interaction designs such as instruction-oriented or constructivist-oriented (Reinmann and Mandl, 2006).

• Theories of motivation: For example, good teaching has to be in accordance with Deci and Ryan’s (1985) motivation theory, Keller’s ARCS model (Keller, 2010), etc.

• Learning theories, such as behaviorist or cognitive learning theories (Haselgrove, 2016) and theories of using technology for learning (Sailer et al., 2021).

• Use of particular patterns, such as classroom management techniques (c.f., Evertson et al., 2006; Emmer and Evertson, 2009; Kiel et al., 2013).

• Empirical studies developing dimensions of good teaching (Marzano, 2000), the most famous being Hattie’s (2008) meta-analysis.

There is most likely no way to make this list complete. We believe these dimensions largely represent important lines of the current discourse. They show that the answer to the question of good teaching is related to the frame in which teaching takes place (society, institution, religion, normative frames, etc.) to criteria for the selection of content, to setting the frame of action or interaction patterns, to theories around teaching, learning, and its prerequisites, and to empirical research. However, although we have many dimensions, there are two opposing views, particularly in reference to content selection and the setting of action and interaction designs, which have many variants.

The famous British idealist philosopher Oakeshott (2004, 136) puts these opposing views in a striking statement: the big question in education is, “Is learning to be understood as acquiring knowledge, or is it to be regarded as a process in which the learner makes the most of himself?” Following Oakeshott, the Oxford educational psychologist Gary Thomas formulates, “Put starkly, the big debate is about how much emphasis should be on the learning of facts, and how much it should be put on the encouragement of thinking” (Thomas, 2013, 16). Thomas argues that this debate goes back to Aristotle and is now reflected in the terms “formal and progressive education.”

This debate is not only Anglo-Saxon. Klafki (2007), a very influential professor of primary education in the post-Second-World-War-Germany, distinguished between “materiale Bildung” (material education) and “formale Bildung” (formal education). “Materiale Bildung” is about encyclopedic knowledge, the learning of facts, whereas “formale Bildung” is about the formation of a personality. John Dewey combines the Anglo-Saxon and German worlds. He makes the distinction between “conservative and progressive education” (Dewey, 1909). The prototype for conservative education for him is the late 18th- and early 19th-century German pedagogue and philosopher Herbart (1969), whom Dewey received thoroughly. According to Dewey’s correct interpretation, Herbart emphasizes that the formation of the mind takes place by setting up certain associations or connections of content by means of a subject matter presented from without. Dewey, as a progressive, preferred the view of the living and active subject exploring its environment, who does not wait for presentations from without.

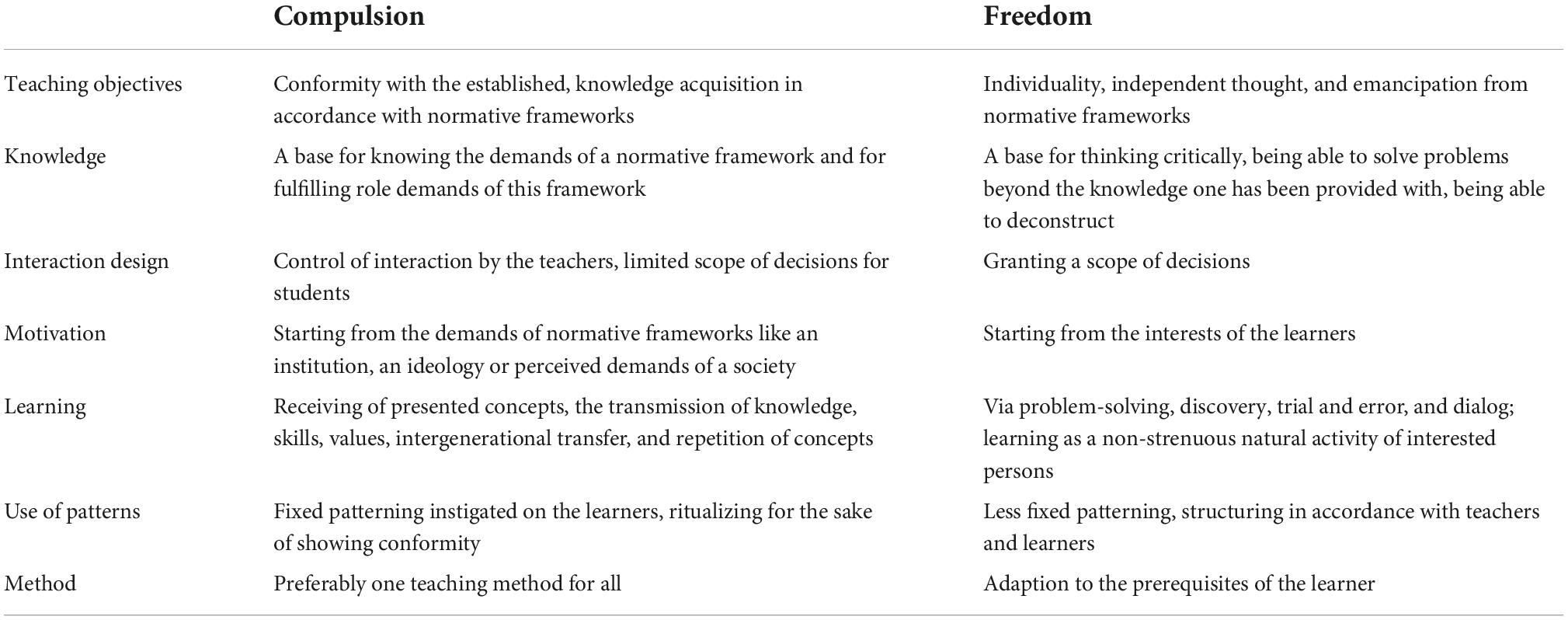

At least for progressive proponents, the idea behind these positions is that teaching and learning are intertwined: teaching is setting the frame of learning, and vice versa; different learners with different prerequisites require different settings of the frame by the teachers. Quite often, statements on learning are statements about creating teaching situations by teachers. In this essay, we assume that what Dewey calls the conservative position and that Klafki terms material education (Klafki, 2007) is more related to the transmission of knowledge (c.f., Thomas, 2013). The transmitters of knowledge (teachers) usually want to make sure that their transmission works—they want control during transmission. Those who prefer the progressive idea, which is more related to the development of the knowledge of a self-determined individual, grant the learner more space for individual content selection or individually set or rather collaboratively negotiated action/interaction patterns. However, the persons in favor of progressive education do not give up the desire to influence the youth. In summary, we can say that the idea of transmission is more bound to compulsion. The idea of the self-determined individual is more bound to freedom. Visualizing this dichotomy on the grounds of typical patterns of teaching theories, we depict these opposing views as depicted in Table 1 (inspired by Thomas, 2013).

According to this interpretation of the opposing views, this essay addresses the following questions:

(1) What arguments favor teaching within the framework of compulsion versus the framework of freedom?

(2) How can these possibilities be reconciled?

(3) Does a myth of good teaching derive from these possibilities?

Arguments in favor of compulsion

At the beginning is the idea of compulsion. Repressive political systems, such as feudal medieval or colonial modern states, as well as modern authoritarian states, which do not believe in individual development, usually want a broad conformity of what is taught at school with their societal and political ideas. However, according to Adorno et al. (1959), authoritarianism is not only instigated on people. It also arises from a “social adjustment through pleasure in subordination and obedience.” This adjustment results from or is interlinked with a repressive social environment. This system of instigation and acceptance is at school best supported by learning arrangements in which the students cannot decide too much on the interaction, where learning usually consists of receiving selected contents according to societal demands and not according to the students’ interests, and where patterns are instigated that do not yield surprising results and allow control. There is a line of outstanding examples of this, starting from Spartan education, called agoge (Marrou, 1982; Zwick, 2006). Agoge means that male children are taken away from their parents to make excellent warriors, loyal to the state and not to the families, in a context of strict rules that were not allowed to be broken. Many historians love to compare Spartan’s ideas with modern ones in relation to autocratic or totalitarian states (c.f., Hodkinson and Macgregor Morris, 2012). In this context, particular emphasis is placed on comparing Spartan education with education during the Third Reich (Roche, 2012). Marrou, the classic researcher of education in classic antiquity, claims that during these times, in Sparta as well as in Athens or Rome, teaching did not address the students’ needs. It was repetitive and accompanied by coercion as physical punishment; in other words, it was “brutal” (Marrou, 1982).

Not at all brutal was Comenius (1896) at the beginning of the 17th century. Together with Ratke he was one of the co-inventers of the term “didactics” in Europe and one of the first modern theorizers on teaching and learning. In his main work “Great Didactic,” he advocated to teach gently and pleasantly. However, he was obsessed by the idea of order and control. According to Comenius, everything in the context of teaching and learning had to be well structured and neatly arranged. Education for him is organizing processes like a “clockwork” set by the teachers and not by the learners. For Comenius the teacher was not only a sun warming the learners but also a “printing press” imprinting knowledge into the learners. This was not possible without compulsion and control.

The concepts of compulsion and control obviously have an appeal up to our times. The French philosopher Foucault (1977), in his worldwide received but also widely disputed research on “Discipline and Punish” shows how the concepts of compulsion and control were and are ubiquitous in all parts of a modern society—education, prison, hospitals, etc. Regardless of different opinions about Foucault’s correct interpretations, from a normative point of view, we must consider that corporal punishment in schools, which was abolished in Germany not until 1972 and in the UK in 1998, is still legal in many states of the USA or even reintroduced (e.g., in one district of Missouri) and is still allowed in many other countries. Empirical research shows that even if corporal punishment is forbidden at school, it is manifold and widely accepted (Gershoff, 2017). In other words, serious forms of compulsion in teaching situations are still popular and are not at all outdated. However, compulsion is not only corporal punishment. As sketched above, it is reflected in teaching objectives, interaction designs, teaching methods, etc. Compulsion wants to direct learners in specific directions. Modern authoritarian states have to find a balance between not undermining their stability via education and the necessity of providing education in order to have a flourishing economy (Sanborn and Thyne, 2014). This has resulted in many forms of education with many constraints. Control of content, learning outcomes, and interaction are very important to achieve a balance (Sanborn and Thyne, 2014).

This view of political frames holds true for many other strict normative frames. Religion works quite similarly to the frame of a state or society. Inclusion, postcolonial theories, or gender theories are no religion, but they offer a frame of strict and strong beliefs, which work as filters for perception and actions (Pajares, 1992). Not following these beliefs in daily actions may lead to societal sanctions. A historical example from the realm of religion and education is the German Francke (1964), who belongs to the period of enlightenment. Francke was a very influential pietist, a religious movement, very popular from the late 17th century to the mid-18th century, with influences up to the 19th century. He was not only a theologist but also an influential educator who founded a few schools in Halle following his ideas. This makes his point of view particularly interesting. He said:

“Mostly, stress is placed on breaking the natural will, hence predominantly to see who only teaches youth in order to make scholars, considers thereby care of the mind, which is good, but not enough, since he forgets the best which is to create the desire to obey” (Francke, 1964, 15, translation by the authors).

For a pietist like Francke, salvation could be hoped for only by the suppression of corrupted individuality. This is the core of his belief system. If the self-will is broken, the youth will be able to wait for the grace of god. In other words, his religious beliefs influenced his ideas about education and his actions in education. Astonishingly, the great philosopher of enlightment, Immanuel Kant, who suffered as a youth at the schools of Francke, agreed, at least to some extent, with Francke. The German idealist philosopher said:

“Thus, for example, children are sent to school initially not already with the intention that they should learn something there, but rather that they may grow accustomed to sitting still and observing punctually what they are told, so that in the future they may not put into practice actually and instantly each notion that strikes them” (Kant, 2007, 438).

The first lesson is that compulsion is not only bound to a state of mind but also to frameworks in which teaching takes place. Societal makeup is only one important framework. Dewey investigated the relationship of this framework with regard to school. According to him, school is an embryonic society that has to reflect societal demands in its organization of teaching and learning (Dewey, 1899). Hartmut von Hentig, a German educational scientist, argues in a similar way. Having Dewey in mind and referring to antique Athens, he considers school as a polis—that is, the antique Greek word for a city state ruled by the body of the citizens. As a polis, school for him is a small society where one learns for the big society outside the school (von Hentig, 1993). For example, if we expect our modern society to be a postcolonial society, school as an embryonic society has to embody postcolonial attitudes, interaction patterns, and fight racism.

If we look at compulsion from the perspective of learning theories, behaviorism is a good candidate for a concept that supports the idea of not providing too much freedom in teaching situations. Behaviorism arose as a counter reaction to an introspective psychology that relies on unobservable mental events (Gerrig and Zimbardo, 2012; Butler and McManus, 2014). For behaviorism, this was a non-scientific approach. To be scientific, behaviorism considers the human mind as an inaccessible black box, whereas behavior represents an entity that is accessible to science, because there is the possibility of observing, categorizing, and controlling. Learning in this framework appears to be a more or less controllable input–output relationship. Teachers are expected to create arrangements that provide deliberated inputs. These inputs are intended to yield well-defined outputs. The roots of this thinking go back to the beginning of the 20th century and have to be associated with names such as Thorndike, Skinner, or Watson (Gerrig and Zimbardo, 2012). The basic instruments for creating these arrangements are, on the one hand, classical conditioning. On the other hand, it is reinforcement—that is, if a student shows the desired output, he will be rewarded, and if not, the student will be sanctioned. Both instruments have been studied minutely. We know from these studies many concepts that are valid today—that is, how conditioned responses die away, generalize, how emotions can be conditioned, how rewards work over time, etc. (Gerrig and Zimbardo, 2012; Butler and McManus, 2014).

Ideas such as these are taken up for school teaching. A prominent and influential example is Mager’s ideas on instruction, originally developed in the sixties of the last century. The focal point of his thought in his classical book (Mager, 1962) is a three-step process: (1) identification and specification of the behavior that will be accepted as evidence that the learner has achieved an objective; (2) description of the desired behavior and the conditions under which the behavior occurs; and (3) description of criteria for how well the learner must perform to be considered acceptable. The underlying idea is that an elaborated performance description serves as a base of evidence that learners have mastered an objective. Mager’s conceptualizations found their way into instructional design and European conceptualizations of teaching. Over the course of time, he revised his original model and complemented it with cognitive aspects. Popular instructional design models, such as those developed by Gagné (1965) or Dick et al. (2005), more than less reveal Mager’s steps supplemented by evaluative steps, revising steps, steps of selecting instructional methods, criterion-referenced tests, etc. The so-called first-generation instructional design (Merrill et al., 1990), which is more closely linked to behaviorist ideas, has Mager in its heart and gives privilege to control of the learning process and learner, in contrast to creative surprising solutions and a broad scope of decisions granted to learners. In Germany, the learning objective-centered didactic or the curricular didactic took up Mager’s ideas (Möller, 1995).

Even in non-behaviorist constructivist contexts, we find the idea of some compulsion. One example is Ausubel’s (1977) meaningful verbal learning, which was largely influenced by Piaget’s constructivism. The basic assumption of meaningful verbal learning is that ideas to be learned have to be related in a sensible way to ideas that the learner already possesses. According to Ausubel, who assumes a hierarchical structure of our concepts in the mind, in learning processes initiated by teachers, the cognitive structure of learners has to be strengthened. Therefore, he proposes as one popular outcome of his ideas the so-called advance organizer, which provides a bird view of the general structure or a “big picture” of the material to be learned. In contrast to behaviorists, Ausubel focuses on what is inside the students’ heads. Their previous experiences and prior knowledge form the basis for learning. Educational psychologists agree that until today (Stern, 2015). However, addressing the hierarchical structure of knowledge in order to connect new knowledge with prior knowledge leaves little space for learners’ decisions on content selection, selection of interaction patterns, etc.

The idea of an association of concepts as central processes in our minds is not new. Members of the so-called philosophical associanist school, such as the philosophers Locke (1690) and Hume (2007), have developed ideas on the association of ideas. Locke, in his essay “Concerning Human Understanding,” wrote a chapter on this. According to him, some of our ideas have natural connections, and some connections are not justified. Hume developed the idea that resemblance, continuity in time and space, and cause or effect connect our ideas. We also must mention the German philosopher and systemizer of education, Herbart, who was a generation later than Locke and Hume. He pushed the idea that new knowledge has to be strictly connected to prior knowledge. This idea is pretty close to the idea of Piaget’s assimilation and is also connected with modern empirical research on the significance of building on students’ prior knowledge (e.g., Stern, 2015). All this is not the same as Ausubel’s concept but can be taken as a kind of pre-idea of his concept (Fleck, 1979).

A last context in the framework of compulsion that is worth mentioning is classroom management. As Marrou (1982) told us, in antiquity, this management usually quite often consisted of corporal punishment when the students showed undesired behaviors. Even earlier in classic pharaonic Egypt, the hieroglyph for education was a beating man (Zwick, 2006, 92). Modern classroom management theories (c.f., Kiel et al., 2013) in the tradition of Kounin or Evertson, two outstanding figures in this realm, are usually in favor of establishing rules in the classroom that have to be obeyed. Further, Kounin (1970) demanded “withitness.” This is a teacher’s awareness of what is going on in all parts of the classroom and the need for learners to know this. One message of modern classroom management is that rules or patterns of interaction in the classroom are necessary to provide a social frame that makes learning and development possible (Evertson et al., 2006; Emmer and Evertson, 2009). They might be negotiated freely or set by teachers. It is hoped that in a supportive classroom, rule violations do not occur too often, but if they usually occur, they are sanctioned.

In summary, compulsion is bound to normative frames and belief systems. These frames are supported by particular views on learning that are most prominent in modern times behaviorist theories. Another strand of theories also supports compulsion to some extent. These are the meaningful verbal learning or associanist theories. Both have in focus the idea that our knowledge or concepts are structured in our brain in terms of favorable or unfavorable and necessary or unnecessary connections.

Arguments in favor of freedom

Freedom as an individual freedom where individuals can participate in societal affairs is a relatively new idea in the history of mankind and in the history of teaching. However, tender shoots of this idea date far back. In modern times, this idea materializes during the enlightment. Montesquieu (1748) developed the concept of separation of powers, Rousseau (1762) propagated a new political system for regaining human freedom and de Gouges (1979) challenged male authority with her “Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen.” Ideas of liberty, freedom, tolerance, and fraternity flourished in the French Revolution and across Europe. In 1789, not only did the revolution in France start, but at the very same time in the former British colony on the other side of the Atlantic, the “Bill of Rights” was ratified by eleven states.

Such ideas formed another view of education and learning. Rousseau and Locke were prominent and influential figures in developing new concepts for teaching and educating (Locke, 1690). Rousseau was most likely one of the most influential figures in modern education. With reference to learning and teaching, he was not interested primarily in imparting knowledge in terms of the content selected by the teachers. He wanted to enable the youth to reason. In his own words:

“To make a man reasonable is the coping stone of a good education, and yet you profess to train a child through his reason! You begin at the wrong end, you make the end the means. If children understood reason they would not need education, but by talking to them from their earliest age in a language they do not understand you accustom them to be satisfied with words […]” (Rousseau, 1921, 53).

This quote is from his world-famous novel on education, “Emile or Education.” The quote postulates the ability to reason as the most important objective of education, but he opposes reasoning as a primary means of education (“and yet …”). On the very same page of the quote, he accuses Locke of not having understood that the ability to reason does not arise from reason disconnected from reality. How can one connect reason with reality? Rousseau described a boy, Emile, raised in the countryside, who learned via various learning experiences arranged by his tutor. Emile was supposed to interact with his environment, to experience the consequences of his actions, and to learn from interaction and the consequences. Reasoning arises from interaction and not from the transmission of content. However, Rousseau’s Emile is not as free in his actions as a sympathetic interpretation of the novel makes us believe. The tutor was very influential, setting a strict frame of Emile’s learning experiences, so Emile had the impression of freedom, but he was actually manipulated, and some interpreters has called the tutor “totalitarian” (Oelkers, 2001).

Regardless of the correct interpretation of Rousseau, he sets the stage for another thinking on arranging teaching and learning. His ideas on learning flourished over a long time, and they are quite in tune with modern theories on learning that oppose behaviorist ideas. Inspired by Dewey’s (1910) ideas on “How We Think,” a few thinkers on progressive education, Piaget’s constructivism and the ideas of the Russian Vygotsky (1978), a so-called “cognitive revolution,” emerged in the 60s and 70s of the last century. Influential names include Bruner, Ausubel, Glaser, Wittrock, and many others in the US (see Zierer and Seel, 2012). In Europe, Aebli (1987) was a very influential researcher who followed similar concepts, and one who was very practically oriented was Kubli (1983).

These scholars rejected the black box and were interested in what was going on in the students’ minds. The basic idea of cognitive approaches of this kind is that learning is not a passive reflective process but an active complex construction. While we are in an environment, we interact with its objects, we organize them in our minds, and we can recognize and manipulate them according to our organizations. Bruner (1957) wanted to go “beyond the information given” and developed the idea of “discovery learning” (Bruner, 1961). Similar to Dewey, he saw problems as the starting point of learning, which ideally takes place in interactions with the environment. In his own words, “Practice in discovering for oneself teaches one to acquire information in a way that makes that information more readily viable in problem solving” (Bruner, 1961). This quote resembles Rousseau’s quote above to a considerable extent. These ideas have been integrated into so-called second- and third-generation instructional designs (see Merrill et al., 1990; Zierer and Seel, 2012).

Cognitivist ideas of this kind, particularly discovery learning, are closely linked to granting students more freedom. Some basic principles of modern discovery learning are as follows (Kiel, 2022): Teachers are more organizers of learning arrangements or learning environments than transmitters of knowledge. Therefore, learners take more responsibility for their learning processes and they can develop solutions beyond the teachers’ expectations. Teaching is not unidirectional but teachers and learners collaborate on setting tasks and interaction rules. Last but not least, content is less important than problem-solving ability.

Overall, this suggests more freedom for the learners but also more responsibility for the learning process. How much freedom is granted, how open tasks should be articulated, and how much guidance of teachers is necessary have been highly disputed down the ages. In 2006 and 2007, there was a series of six articles in the “Educational Psychologist” arguing about the necessary amount of guidance in successful learning processes (Kirschner et al., 2016; see the summary by Vogel et al., 2017, 54–56). However, no clear answer has been offered, but a consensus exists that guidance and formats of tasks have to be adapted to the learners’ needs and prerequisites.

Apart from theories in the context of instructional design, some more radical constructivist concepts have been developed to grant the learning processes of learners more freedom. We mention only one of these approaches—Project Zero from Harvard University—which has been in existence for 50 years. In Europe, it is not as popular as instructional design. A good summary of the project’s ideas is offered in the book “Making Thinking Visible” (Ritchhart et al., 2011), written by a Harvard researcher and two practitioners. Their basic assumptions are: (1) “Thinking doesn’t happen in a lockstep, sequential manner, systematically processing from one level to the next. It is much messier, complex, dynamic, and interconnected than that,” (2) the role of teachers needs a shift “from the delivery of information to fostering students’ engagement with ideas”; and (3) teachers have to make the students’ “thinking visible” in order to work with it (Ritchhart et al., 2011, 26, 34). In other words, the authors from Harvard do not believe too much in hierarchies; they reject black boxes and favor letting students find their own way to engage with content.

How does this take place? The authors offer a couple of activities called “thinking routines” to engage with content. The routines are simple patterns of thinking that can be used over and over again. Some of the routines are verbal routines which address exploration, connection making or conclusion. These are questions like “What’s going on here?” and “What do you see that makes you say so?” Some other routines are non-verbal as the CSI (Color, Symbol, and Image) routine. This routine demands to attribute a color to a content, for example, a color to the Declaration of Independence, a novel like James Joyce’s Ulysses etc. After having attributed a color to a content the students are asked for justifying or explaining the attribution. This approach is closely linked to educational theories of critical thinking. Core critical thinking skills are analysis, interpretation, self-regulation, inference, explanation, and evaluation (Facione, 2020). With the help of these skills, learners are able to check and uncover assumptions, explore alternative perspectives, and take informed actions as a result. Such thinking skills are among the basic competences for solving problems.

Since we argue that the normative frame influences teaching and learning considerably, we have to ask in Dewey’s terms: do the teaching arrangements that grant freedom really contribute to an embryonic society at school, which reflects the society outside? To do this, we need a model representing as many modern societies as possible. This is not easy and is undoubtedly subject to many criticisms, whatever model one chooses. We think that the Polish philosopher Bauman (2000) provides a frame that catches a great variety of aspects of many modern societies. He describes the current state of the world as “liquid modernity.” At least postmodernists and many modernists will agree on the fluidity of our society (Ritzer and Murphy, 2014), which materializes via the rapid transfer of data across the globe, as well as a rapid transfer of goods, money, services, and, of course, ideas or concepts. Change is ubiquitous in our world.

Barz et al. (2001) combine the ideas of Bauman with Beck’s concept of reflexive modernization (Beck, 2009) and describe their basic ideas by referring to four core concepts:

(1) Delimitation: For example, borders are literally crossed by migrating people and in a figurative way borders are crossed by a pluralism of values and a deconstruction of established concepts which changes the composition of groups in all institutions of our society; proven contents are questioned by new people and new ideas.

(2) Fusion: For example, traditional media merge with new technologies and virtual spaces that demand new concepts of learning and teaching; a mobile phone today is not only a phone but also a storage, a music player, a computer, etc.

(3) Permeability: For example, social stratification still exists, but it does not determine lives as heavily as before; gender is supposed not solid anymore, one can move to more than one other.

(4) Changing configurations: For example, since among classic family and living concepts, we now have plural concepts of family, life, work, leisure, etc., which demand new types of flexible organization also in education.

The liquid society, as sketched here, lacks solidity as long-running structures, permanent concepts, or values we can rely on. Temporariness, vulnerability, and an inclination to constant change characterize this society. Teaching and learning must address this. If school, in Dewey’s terms, has to be an embryonic picture of the world outside, it has to enable learners to deal with the fragility around them. Facts transmitted from one generation to another become less important, and the ability to solve problems in rapidly changing environments gains importance. The idea of modern learning and teaching theories that regard learners as individuals who are able to solve problems and who can discover and interpret their environment and make deliberate decisions afterward suits the society sketched above to a considerable extent (Dochy et al., 2003). The shift from learning objectives to competence orientation, which is understood as the ability to solve problems (Weinert(ed.), 2001), is most likely a step toward dealing with our liquid world.

Reconciling the positions: The balance between compulsion and freedom

We consider the arguments for compulsion and freedom to be a thesis and antithesis. This section provides a synthesis of both. Theoretically, this synthesis is based on philosophical concepts, ideas from educational and cognitive psychology and educational concepts. We summarize some of the arguments and start with philosophy.

In his lectures on pedagogy, the German philosopher Kant writes about a paradox: “One of the biggest problems of education is how one can unite submission under lawful constraint with the capacity to use one’s freedom. For constraint is necessary. How do I cultivate freedom under constraint? I shall accustom my pupil to tolerate a constraint of his freedom, and I shall at the same time lead him to make good use of his freedom […]” (Kant, 2007, 446). For Kant, freedom is not limitless. There are always constraints. Kant argues that constraints at the beginning of the process of education have to be tighter, since children are not able to use freedom reasonably or wisely. Later in the process, it is possible to grant more freedom. Always, freedom, in terms of autonomy and being able to participate in societal affairs, has to be a non-negotiable objective. Many thinkers of education (e.g., Heitger et al., 2004) share this position. For Kant, freedom and compulsion are related. First, there are constraints, and later, the constraints can be resolved.

The British philosopher Oakeshott (1959) is a modern philosopher of our times but also belongs in a wide sense to an idealist philosophical school, as Kant does. In his worldwide essay “The Voice of Poetry in the Conservation of Mankind,” he depicts human beings as acting in a world of many meanings. These meanings have different voices: science, literature, art, common sense, etc. For example, each of these voices can comment on a concept such as democracy. These comments or expressions of the voices are called the “conversation of mankind.” Conversation for him is a “playing around” with ideas. The core of education in families and the school is, for him, introducing or initiating the younger ones into this conversation. According to him, one can only take part in a conversation when the person knows something; in other words, the person has to know facts, rules, or codes of conversation. However, children and youths are supposed to develop their own voices in their world of conversation in order to develop “virtuosity.” Oakeshott also relates to compulsion and freedom. At the beginning, there has to be pressure to learn some facts, the particular facts, rules, and codes of the voices. Later, men have to free themselves from what has been transmitted in order to develop their own voices.

We find similar ideas in the expert-novice theory (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1986; Berliner, 2001), a powerful concept in educational and cognitive psychology. This theory makes a difference between persons at relatively high performance levels in a given domain, the experts, and persons with a low performance level in a domain, the novices. The difference between the two is a continuum. Experts are faster and more accurate than novices when solving typical tasks of the domain; inoperable plans are given up earlier. Applied to learning and teaching, the theory defines a final objective of these processes: to become an expert. However, the theory defines as the starting point the stadium of a novice, a person who does not know enough to show a high performance; for example, a person who tries to speak a foreign language after 6 weeks of training. Novices need more guidance than experts in order to perform acceptably. This guidance usually represents constraints. Again, at the beginning of the process of learning, compulsion seems to be necessary to acquire what is necessary for later performances. A few socio-constructivist teaching models, such as cognitive apprenticeship (Collins, 1991), follow these ideas. Usually, we have phases: (1) modeling, (2) scaffolding, (3) fading, and (4) coaching. Fading, the phase of less support and more autonomy, points to the moment in which freedom is gradually granted. Independent of socio-constructivist theories, master–apprenticeship relations represent an old form of learning arrangements dating back to antiquity in Europe.

In the framework of educational psychology and cognitive psychology, particularly with reference to learning theories, “adaption” is an important term. Modern learning theories in the tradition of constructivist ideas argue in favor of adapting the teaching process to learners’ needs and prerequisites as a core concept of modern teaching. According to Helmke (2017, 45, translation by the authors), adaption is “the variation of subject-specific and subject-overarching content, the adjustment of difficulty and speed according to the specific learning situation and learning requirements of students (resp. student groups), the sensitive handling of diverging learning conditions and other attributes of students, especially regarding differences in their social, linguistic and cultural background and in their level of performance.” For freedom and compulsion, this means that there is no way to determine whether either of these dimensions is more important without looking at the particular situation and the particular prerequisites and needs of the learners. For example, in the context of special needs education, children with behavioral difficulties are usually confronted with systematic instruction and strict rules that they obey (Morse and Schuster, 2004). Otherwise, a socially competent learning group needs fewer regulations. Unfortunately, adaption is usually only related to learners. However, teachers require high competences to do what Helmke demands. It is necessary to adapt teaching also to teachers’ competences and needs. For example, some teachers need more structures and strict rules than others to be successful.

Some educational concepts are closely linked to the theories just mentioned. In Germany, one influential concept has been developed by Klafki. The German professor for primary education tried almost his entire life to determine what “Bildung” was (Klafki, 2007). According to Bruford (1975), this German term translates into “education for the cultivated mind.” His theory largely displays no explicit connection to modern psychological learning theories. However, certain similarities can be discovered. His thought is based on the humanities and is particularly influenced by Hegel’s dialectics. Trying to systemize theories of the cultivated mind in Germany, he came up, as mentioned above, with the thesis of “materiale Bildung,” that is, facts, encyclopedic knowledge, and “formale Bildung,” which are related to forming one’s personality. As a good Hegelian, he tried to find a synthesis, which he called “kategoriale Bildung” (categorial education). In his later versions of his theorizing, categories are “epochaltypische Schlüsselprobleme (epoch typical key problems),” such as the democratization of society, the question of war and peace, environment education, or the relation of genders. To deal with these key problems, according to Klafki, we need both “materiale Bildung” and “formale Bildung.” The teachers’ task is to pose problems in lessons in which learners need both types of Klafki’s dimensions. For example, if teachers create lessons on the climate catastrophe, learners need to acquire facts on global warming and its consequences before one turns to aspects such as how we can personally contribute to minimizing global warming, how we have to change our belief systems, etc. Although Klafki’s thinking is based in German humanities, his work can be related to ideas of problem-based learning or Bereiter’s ideas on instructional design (Kiel, 2017).

What do we learn from these four positions? Obviously, we can assume that all positions agree on using compulsion at the beginning of the learning–teaching processes, and they are in favor of granting more freedom in later stages. The underlying idea is that in some way, good or excellent performance needs knowledge in terms of facts but also in terms of basic actions to achieve mastery in performances. Furthermore, we can suppose that learners usually need guidance; otherwise, they do not come to know the necessary facts and actions to show mastery; however, this is defined in the positions mentioned above. The amount of guidance and compulsion associated with attaining mastery is highly disputed.

The dispute can be resolved through three ideas:

(1) Normative frames provided by society, curricula, influential institutions, religion, influential belief systems, etc. have a strong impact on how much freedom and compulsion will be granted, and they determine what is necessary in terms of content, interaction designs, etc.

(2) Preparing for our modern liquid society requires more than the transmission of established concepts. Problem solvers and flexible persons who are not intimidated by change, deconstruction, and variation are preferred. This makes arrangements in which one learns to use freedom wisely necessary.

(3) Modern learning theories, in the framework of the concepts of adaption, would argue that the amount of guidance and constraints and the point of granting freedom could never be determined without having a look at the individual needs and prerequisites of learners and teachers. Therefore, the decision to arrange learning in frameworks of compulsion or freedom relates to the interplay of different factors.

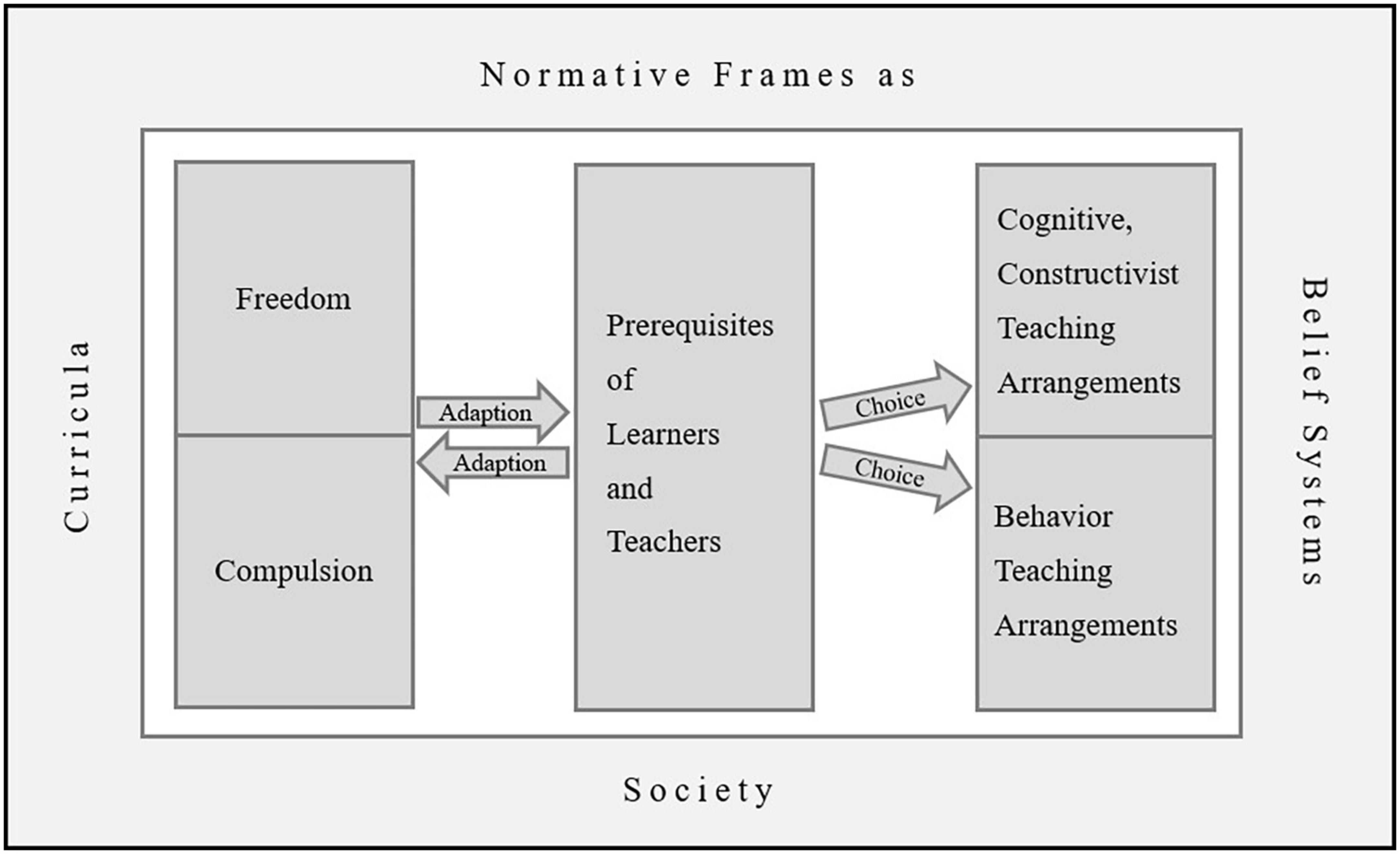

The following illustration (Figure 1) visualizes this interplay:

The exterior rectangle depicts normative frames existing in any society. There is no reference to religion, since we subsume religion under belief systems. The inner rectangles refer to the basic decisions of arranging teaching in a framework of freedom or compulsion. This decision is intertwined with the normative frame, but it also depends on the learners’ and teachers’ prerequisites. For example, if a curriculum demands arranging a teaching situation in terms of discovery learning, but the prerequisites of the learners do not enable them to do discovery learning, one has to change plans. Conversely, it is possible that a teacher does not feel competent in dealing with a discovery learning unit of this kind, and again plans have to be changed. After dealing with prerequisites, there is a choice to rely more on cognitive or constructivist teaching arrangements or on behaviorist arrangements. Usually, one always has a combination. Even very open learning arrangements require direct instruction as a starter. Techniques from the behaviorist toolkit, such as defining learning objectives, use reinforcement to make learning effective. Therefore, the illustration gives the impression of a linear process, but actually, it is an iterative process going forward and backward.

Myths of good teaching

At this point, we can identify an important source of myths about good teaching. All claims about knowing the best teaching method independent of the learners’ prerequisites and needs are useless. Concepts that look at children as young scientists eager to explore the environment and find solutions on their own are not superior to concepts that look at learners as empty vessels or a tabula rasa to be filled by the means of behaviorist methods, methods of meaningful verbal learning, or other highly structured methods. We had discussions of this kind on either side of the Atlantic. In the US, the so-called Ausubel-Bruner debate in the late 1960 and 1970, where Ausubel argued against Bruner’s early radical discovery concepts, is one example (Ausubel, 1978). In Germany, in the 1970 and parts of the 1980, many scientists were looking for the perfect teaching method (see Kiel, 2018). Modern learning theory and cognitive psychology taught us that this is not a seminal approach running short of important information—the prerequisites and needs of the learners provide one frame of what is possible and necessary and what is not.

Another frame of producing a myth about teaching is the attempt to justify granting more or less freedom by simply arguing only along the perspective of learning theories or only looking at the individual. Adaption to prerequisites is an important aspect, but normative frames are also very important, although they are often not too much appreciated by scientists. Norms do not determine what is going on in schools, but in institutionalized state schools, teachers are bound to them. In a repressive state, a teacher might be able to teach critical thinking but very likely will not do so because of sanctions. Vice versa, in a democratic state, not all teaching meets the ideals of autonomy because teachers have different belief systems.

Today, quite often, empirical research is misunderstood in a mythical way. In Germany, for the past 20 years, we have been having a discussion on open learning situations. In 2014, a scientist with a high reputation, Olaf Köller, argued that progressive teaching manifested in open learning situations and cross-year-learning is inferior to well-structured direct instruction, a statement that found its way into the popular press (see Brügelmann, 2017). This hurts many who believe in the ideals of freedom in progressive education. With the rise of Hattie’s meta-analysis, some teachers interpreted his findings on open learning situations, stating that “I use now direct instruction because, according to Hattie, it is more effective than open learning situations.” Such interpretations could be the origin of teaching myths. Unfortunately, Hattie’s dimensions are not the holy grail of teaching (see Brügelmann, 2017; Nielsen and KlitmØller, 2021). The 138 dimensions he identified are not related to each other, and we do not have too many statements on how to adapt these dimensions to learners’ prerequisites and needs.

Therefore, what is a good balance between compulsion and freedom? The answer is not easy to observe or measurable. A good balance considers the interplay of frames, individual prerequisites, and theories of learning and teaching arrangements.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EK and SW contributed to the conception of the manuscript, revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, N. (1959). The Authoritarian Personality. New York, NY: Harper and Row Publishers.

Aebli, H. (1987). Grundlagen des Lehrens: Eine allgemeine Didaktik auf psychologischer Grundlage [Principles of Teaching: General Didactics Based on Psychological Theories]. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Ausubel, D. P. (1977). The facilitation of meaningful verbal learning in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. 12, 162–178. doi: 10.1080/00461527709529171

Ausubel, D. P. (1978). In defense of advance organizers: a reply to the critics. Rev. Educ. Res. 48, 251–257.

Barz, H., Kampik, W., Singer, T., and Teuber, S. (2001). Neue Werte, neue Wünsche [New Values, New Desires]. Berlin: Metropolitan.

Bell, M. P., Connerley, M. L., and Cocchiara, F. K. (2017). The case for mandatory diversity education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 8, 597–609. doi: 10.5465/amle.8.4.zqr597

Berliner, D. (2001). Learning about and learning from expert teachers. Int. J. Ed. R. 35, 463–482. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00004-6

Bruford, W. H. (1975). The German Tradition of Self-cultivation: “Bildung” from Humboldt to Thomas Mann. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Brügelmann, H. (2017). “Offener Unterricht ist (k)ein erfolgreiche “Methode”. Zu den Grenzen standardisierter Wirkungsstudien in der Pädagogik,” in [Open Learning Is A(n) (Un)successful Method. On the Limits of Standardized Effects Study in Education] in Mythen – Irrtümer – Unwahrheiten [Myths – Errors –Untruths], ed. H.-U. Grunder (Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt), 201–207.

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educ. Rev. 31, 21–32. doi: 10.4324/9780203088609-13

Butler, G., and McManus, F. (2014). Psychology. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Collins, A. (1991). “Cognitive apprenticeship and instructional technology,” in Educational Values and Cognitive Instruction: Implications for Reform, eds L. Idol and B. F. Jones (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 121–138.

Comenius, J. A. (1896). Great Didactic of Jan Amos Comenius. Translated into English and edited with Biografical, Historical and Critical introductions M.A. Keatinge. London: Adam and Charles Black.

de Gouges, O. (1979). “Declaration of the rights of woman and female citizen,” in Women in Revolutionary Paris. 1789-1795, eds D. G. Levy, H. B. Applewhite, and M. D. Johnson (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press), 89–96.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-determination in Human Behaviour. New York, NY: Plenum.

Dewey, J. (1899). “The school and society,” in The Middle Works: 1899-1924, ed. J. A. Boydston (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press), 1.

Dick, W., Carey, L., and Carey, J. O. (2005). The Systematic Design of Instruction, 6th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., Van den Bossche, P., and Gijbels, D. (2003). Effects of problem-based learning: A metaanalysis. Learn. Instr. 13, 533–568. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(02)00025-7

Dreyfus, H. L., and Dreyfus, S. E. (1986). Mind Over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Emmer, E. T., and Evertson, C. M. (2009). Classroom Management for Middle and High School Teachers. Pearson: Upper Saddle River.

Evertson, C. M., Emmer, E. T., and Worsham, M. E. (2006). Classroom Management for Elementary Teachers. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Facione, P. A. (2020). Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts. Available online at: https://www.insightassessment.com/wp-content/uploads/ia/pdf/whatwhy.pdf [Accessed on September 13, 2022].

Fleck, L. (1979). Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Gershoff, E. T. (2017). School corporal punishment in global perspective: prevalence, outcomes, and efforts at intervention. Psychol. Health. Med. 22, 224–239. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1271955

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-analyses Relating to Achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Heitger, M., Böhm, W., and Ladenthin, V. (2004). Bildung als Selbstbestimmung [Cultivating the Mind as Self-determination]. Paderborn: Schöningh.

Helmke, A. (2017). Unterrichtsqualität und Lehrerprofessionalität: Diagnose, Evaluation und Verbesserung des Unterrichts [Quality of Teaching and Teacher Professionalism: Diagnosis, Evaluation and Improvement of Teaching], 7th Edn. Seelze-Velber: Klett/Kallmeyer.

Herbart, J. F. (1969). “Allgemeine Pädagogik aus dem Zweck der Erziehung abgeleitet [General Pedagogy Deduced from General Objectives of Education],” in Johann Friedrich Herbart: Pädagogische Texte [Johann Friedrich Herbart: Pedagogical Works], ed. W. von Asmus (Düsseldorf: Helmut Küpper).

Hodkinson, S., and Macgregor Morris, I. (2012). Sparta in Modern Thought. Politics, History, and Culture. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales.

Hume, D. (2007 [1748]). An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Trans P. Millican (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Kant, I. (2007). “Lectures on Pedagogy (1803),” in Anthropology, History, and Education (The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant), eds R. Louden and G. Zöller (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 434–485.

Keller, J. M. (2010). Motivational Design for Learning and Performance. The ARCS Model Approach. New York, NY: Springer.

Kiel, E. (2017). ““Schlüsselprobleme weiter denken!” [Rethinking Epoch Typical Key Problems!],” in Erziehungswissenschaftliche Reflexion und pädagogisch-politisches Engagement. Wolfgang Klafki weiterdenken [Educational Reflection and Educationally-politically Commitment. Rethinking Wolfgang Klafki], eds K.-H. Braun, F. Stübig, and H. Stübig (Wiesbaden: Springer), 109–123.

Kiel, E. (2018). “Unterrichtsforschung im Kontext der empirischen Bildungsforschung, [Teaching Research in the Context of Empirical Educational Research],” in Handbook Educational Research, eds R. Tippelt and B. Schmidt-Hertha (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 989–1010.

Kiel, E. (2022). Schulpädagogik. Normen – Theorie – Empirie [Education in the School. Norms – Theorie – Empiricism]. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Kiel, E., Frey, A., and Weiss, S. (2013). Trainingsbuch Klassenführung [Training Book Classroom Management]. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., and Clark, R. (2016). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educ. Psychol. 41, 75–86. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Klafki, W. (2007). Neue Studien zur Bildungstheorie und Didaktik. Zeitgemäße Allgemeinbildung und kritisch-konstruktive Didaktik [New Studies in Educational Theory and Didactics. Contemporary General Education and Critical-constructive Didactics]. Weinheim: Beltz.

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and Group Management in Classrooms. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Kubli, F. (1983). Erkenntnis und Didaktik. Piaget und die Schule [Recognition and Didactics: Piaget and the School]. Basel: Reinhardt.

Marrou, H. (1982). A History of Education in Antiquity, ed. G. Lamb (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin press).

Marzano, R. (2000). A New Era of School Reform: Going Where the Research Takes Us. Aurora, CO: McREL.

Merrill, M. D., Li, Z., and Jones, M. K. (1990). Limitations of first generation instructional design. Educ. Tec. 30, 7–11.

Möller, C. (1995). “Die curriculare Didaktik [Curricular Didactics],” in Didaktische Theorien [Didactical Theories], eds H. Gudjons, R. Teske, and R. Winkel (Hamburg: Bergmann und Helbig), 63–77.

Morse, T. E., and Schuster, J. W. (2004). Simultaneous prompting: A review of literature. Educ. Train. Dev. Disab. 39, 153–168.

Nielsen, K., and KlitmØller, J. (2021). Blind spots in visible learning: A critique of John Hattie as an educational theorist. Nord. Psychol. 73, 268–283. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2021.1962731

Oakeshott, M. (1959). The Voice of Poetry in the Conservation of Mankind. An Essay. London: Bowes & Bowes.

Oelkers, J. (2001). Einführung in die Theorie der Erziehung [Introduction in the Theory of Education]. Weinheim: Beltz.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 307–332. doi: 10.3102/00346543062003307

Plato (2017). Euthyphro. Apology. Crito. Phaedo, eds C. Emlyn-Jones and W. Preddy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Reinmann, G., and Mandl, H. (2006). “Unterrichten und Lernumgebungen gestalten” [Designing Lessons and Learning Environments],” in Pädagogische Psychologie [Educational Psychology], eds A. Krapp and B. Weidenmann (Weinheim: Beltz), 613–658.

Ritchhart, R., Church, M., and Morrison, K. (2011). Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Ritzer, G., and Murphy, J. (2014). “Festes in einer Welt des Flusses: Die Beständigkeit der Moderne in einer zunehmend postmodernen Welt” [The Resistance of the Modernity in an Increasing Postmodern World],” in Soziologie zwischen Postmoderne, Ethik und Gegenwartsdiagnose [Sociology between Postmodernism, Ethics and Diagnosis of the Present], eds M. Junge, T. Kron, and Z. Bauman (Wiesbaden: Springer Verlag), 45–68.

Roche, H. (2012). “Spartanische Pimpfe’: The importance of sparta in the educational ideology of the adolf hitler schools,” in Sparta in Modern Thought: Politics, History and Culture, eds S. Hodkinson and I. M. Morris (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales), 314–342.

Sailer, M., Schultz-Pernice, F., and Fischer, F. (2021). Contextual facilitators for learning activities involving technology in higher education: The C?-model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 121:106794. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106794

Sanborn, H., and Thyne, C. L. (2014). Learning democracy: education and the fall of authoritarian regimes. Brit. J. Polit. Sci. 44, 773–797. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000082

Smith, M. U., Siegel, H., and McInerney, J. D. (1995). Foundational issues in evolution education. Sci. Educ. 4, 23–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00486589

Stern, E. (2015). “Intelligence, prior knowledge, and learning,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn, Vol. 12, ed. J. D. Wright (Oxford: Elsevier), 323–328.

United Nations (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtm [Accessed on January 20, 2022].

Vogel, C., Weidlich, J., and Bastiaens, T. (2017). Instructional Design und Medien. Kultur und Sozialwissenschaften [Instructional Design and Media. Culture and Social Sciences].

von Hentig, H. (1993). Schule neu denken. Eine Übung in praktischer Vernunft [Rethinking School. An Exercise in Practical Reason]. München: Carl Hanser.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Zierer, K., and Seel, N. M. (2012). General Didactics and Instructional Design: eyes like twins. A transatlantic dialogue about similarities and differences, about the past and the future of two sciences of learning and teaching. SpringerPlus 1:15. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-1-15

Keywords: learning theory, teaching theory, teaching myth, behaviorism, compulsion, constructivism, freedom, modernization

Citation: Kiel E and Weiss S (2022) Good teaching—The adaptive balance between compulsion and freedom. Front. Educ. 7:1046317. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1046317

Received: 16 September 2022; Accepted: 16 November 2022;

Published: 02 December 2022.

Edited by:

Norbert M. Seel, University of Freiburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Katriina Maaranen, University of Helsinki, FinlandLudwig Haag, University of Bayreuth, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Kiel and Weiss. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ewald Kiel, kiel@lmu.de

Ewald Kiel

Ewald Kiel Sabine Weiss

Sabine Weiss