- 1English Department, College of Languages and Translation, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

- 2English Skills Department, Preparatory Year, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

Comprehension is one of the most crucial factors contributing to acquiring a new language; therefore, teachers must facilitate language comprehensibility using the best teaching practices to help learners understand the target language. This study aimed to identify tertiary EFL teachers’ practices for teaching language comprehensibility to assist in highlighting the comprehensibility practices tertiary EFL teachers employ to ensure that students understand, interact with, and use the English language. To identify the extent that the teachers employ language comprehensibility practices in an EFL context, the descriptive-correlational approach was employed. A closed-item questionnaire was administered to a sample of 65 teachers in Najran University, Saudi Arabia in the academic year 2021–2022. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v. 23) was used to analyze the data. The results showed that tertiary EFL teachers taught language comprehensibility very skillfully. Also, no significant difference in teaching language comprehensibility was found concerning the gender variable. There were, however, differences in the means of the sample’s responses towards methods of teaching language comprehensibility according to years of experience, particularly for those with the most years of experience. Considering the results, the study suggested paying more attention to integrating language comprehensibility practices in EFL contexts.

Introduction

Comprehensibility is vital in any foreign language learning, and “success in language learning is attributed to successful language teaching” (Kosar and Dolapçıoğlu, 2021, p. 231). In general, teaching is a demanding career that constantly looks for individuals with knowledge of the specifics and pedagogical nuances (Shulman, 1986). Teaching, on one hand, refers to all processes and activities designed to impart knowledge, skills, and understanding at all levels of education. The goal of teaching is to ensure learning, so if learning does not take place, the goal is not achieved. Soga (2000) sees education as a planned arrangement between the teacher and the learner on a particular subject to achieve learning using appropriate methods and materials. Based on the professional principle, teaching is a planned, logical, well-organized process of transmitting knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Teaching is an art and a science that must be properly planned to ensure effective education. Also, it requires flexibility, creativity, and responsibility to provide an educational environment to respond to the learner’s needs (Tulbure, 2012). In addition, teaching requires a well-trained and prepared teacher to deliver content to learners in simple, clear, and understandable ways since effective teaching is linked to students’ successful learning. Kosar and Dolapçıoğlu (2021) reported that teachers’ employment of interactive activities and pair and group work could promote students’ English language learning. Therefore, it is a process that a teacher needs to learn consciously. Therefore, teachers need not only to know the content but also how students perceive and understand language. In addition, teaching is intricate and complex; it includes several tasks and moves. Ball and Forzani (2009) argue that the profession of teaching entails the primary duties that instructors should carry out to help students learn. These practices are called teaching practices. It is essential to discover the specific actions that support and promote efficient learning when teaching. Teaching methods are beneficial actions that promote efficient learning. Therefore, a teaching strategy is an instructional method or plan for classroom actions or interactions to achieve specific learning objectives, including induction, referencing, use of examples, planned repetition, stimuli, effective use of questions, and summarization (Ayua, 2017). A teaching strategy is a generalized plan of the lesson(s) that includes the structure of the learner’s desired behavior in terms of the objectives of the instruction and an outline of the tactics needed to implement the strategy. Teaching strategies are the techniques used to assist students in learning the course material that is necessary for success and creating attainable future goals. Teaching strategies let teachers choose the best approach to deal with a specific target group by identifying the many accessible learning methods (Sarode, 2018). Various elements are integral to the teaching and learning process; however, “effective teaching strategies such as using evidence-based practices, high leverage practices, and proper scaffolding will help ensure that my students are obtaining a quality education” (Lampe, 2022, p. 32). Effective teaching includes not only tools, techniques, and strategies for improving student learning but also understanding the context, mainly how students learn, how they process information, what motivates them to learn more, and what hinders the learning process. An effective teaching strategy helps students achieve their goals and succeed in life. Classroom teaching practices refer to a set of observable and measurable actions that a teacher can engage in to support their students. They include learning discovery, problem-based learning, collaboration, classroom discussion, “learning in group, lecture method, and interview methods as well as reading practice” (Tanjung, 2022, p. 7). Effective teachers have a foundation of practices they continually engage in that promote academic achievement and appropriate behavior and build relationships with students and families. Furthermore, they adapt these practices based on students’ needs to support all students within the classroom environment effectively (Macsuga-Gage et al., 2012). Instructional practices are techniques that teachers use to help students become independent learners. These practices become learning practices when students independently choose appropriate practices and use them effectively to accomplish tasks or achieve goals. Instructional practices can motivate and help students focus and organize information for understanding and remembering and monitor and evaluate learning (Learning, 2002). To compete in this rapidly changing world, today’s students will need creativity, problem-solving abilities, a passion for learning, a work ethic, and lifelong learning opportunities. Students, through instruction-based teaching practices, can develop these abilities. Best practices are applied to all grade-level students in higher education, and these practices engage and motivate students to learn and achieve their desired goals. Students who receive a balanced curriculum and possess the knowledge, skills, and abilities to convey and link ideas and concepts across disciplines will be successful according to standardized tests and other indicators of student success (Sarode, 2018). Hence, the researchers believe that EFL teachers must know the appropriate EFL teaching strategies, and techniques to employ them to help students comprehend and use the target language. In the same context, teaching practices, too, for language comprehensibility become crucial for students’ learning comprehension, interaction, and use of the English language. It is hoped that this study would assist in highlighting the comprehensibility practices tertiary EFL teachers employ to ensure that students understand, interact with, and use the English language correctly.

Literature review

Language comprehensibility, as defined by Glisan and Donato (2017), refers to how foreign language teachers can make a language understandable to students, establish situations that encourage foreign language comprehensibility, and involve students in intelligible interactions. According to Glisan and Donato (2017), this three-pillar practice of language comprehensibility for students (language, context, and interaction) was based on literature and previous studies. As argued by Swain (1985), comprehensible language is crucial because language comprehensibility enables students to identify knowledge gaps, speculate about alternative ways to convey ideas, and concentrate on how language generates meaning. Glisan and Donato (2017) opined that students need to use the target language in real-world situations to advance their proficiency. Empirical literature on the teaching practices of language comprehensibility is very limited. However, the following studies are presented to get the insight of the subject matters researched in the current study. For example, Maquire et al. (1999) opines that clear learning experiences boost retention. And, for students to gain language abilities, effective language instruction must offer highly understandable, meaningful, and engaging speaking and text in the target language. In this sense, meaning is crucial for fostering comprehension and learning (Sousa, 2011). Therefore, effective teaching in terms of comprehension must focus on making meaning clear for learners. It is also to ensure that they are not demotivated. The use of language as a mediating tool, or more particularly how we speak to learners, is crucial for learning (Glisan and Donato, 2017), and the effectiveness of this can affect what pupils learn and do not learn. Instead of merely serving as information for internal processing in learners’ brains, using the foreign language for teaching becomes a tool to moderate language acquisition and growth. Students can perform with the aid and achieve what they cannot do on their own. Thanks to the way, professors speak to them and interact with them. As they communicate in the target language, learners can be heard discussing the language (they use), challenging their usage, and seeking help when necessary. It has been discovered that learners can significantly improve their capacity to function in meaningful ways in the target language through cooperative and supportive interactions with teachers and with each other (Glisan and Donato, 2017).

Teachers can employ many tactics to promote understanding and support meaning-making in conversation so that students can communicate and use language imaginatively without worrying about receiving too much feedback or criticism. In a nutshell, students should be taught using the input they learn about the target language on the spot. The input must be understandable to encourage learning a foreign language. Both students and teachers would find it challenging to learn another language without understandable input (Simpson, 2021). Language learning and teaching is a two-way process (input and output), and comprehensibility practices are crucial to facilitate learners mastering the target language. The issue of how to make input understandable becomes significant if input comprehensibility is required for L2 acquisition. This can be accomplished by streamlining and altering the input given to learners of foreign languages (Hasan, 2008). Troyan et al. (2013) implemented a practice-based approach centered around three key practices: comprehensive use of the target language during instruction, questioning to develop and gauge student understanding, teaching grammar inductively in meaningful contexts and co-constructing understanding. Saito et al. (2022) examined the possibility of establishing quick and reliable automated comprehensibility assessments in which they gathered many spectrograms to build an acoustic model for each speech class. The spectrogram transmitted a variety of nonlinguistic elements “such as speaker, age, gender, and microphone” (p. 8). In a pilot study, Thrasher (2022) investigated the effects the physiological foreign language anxiety and oral comprehensibility. Participants had reduced anxiety in virtual reality, according to the findings. Finally, raters discovered that participants were more comprehensible in virtual reality and when they self-reported having less anxiousness. Vraciu and Curell (2022) study compared the presence of discourse features and strategies that support students’ input comprehension and output in a series of English-medium instruction classes taught by English L1 and English L2 lecturers. The findings demonstrated that both instructors used a range of techniques to encourage comprehensible input and student involvement. Comparatively to his English L2 counterpart, the English L1 lecturer supported more comprehensible input. Friedrich and Heise (2019) tested the notion that gender-neutral language makes texts harder to comprehend. After reading a material, exclusively masculine forms or consistently mixed masculine and feminine forms, that was randomly allocated to 355 students who later responded to a comprehensibility questionnaire. Participants who had read a text written in gender-neutral language did not rate the text’s comprehensibility lower than those who read the text written exclusively in masculine forms. The findings suggested that using gender-neutral language does not make a text less comprehensible.

In addition to the studies cited above, foreign/s language teaching practices have been examined worldwide, revealing varying results. Intarapanich (2013) identified the strategies and approaches to teaching English as a foreign language in Thai primary and secondary schools. Observation and interviews with five teachers were used to collect data. The results showed that EFL teachers mostly used three teaching approaches: communicative, grammar translation, and total physical response. As for teaching strategies at the secondary level, the used instruments were conversations, role-play, debates, and group work. Whereas, at the primary level, the used instruments were pair work, group work, drills, spelling games, and songs. Kuznetsova (2015) experimented with three EFL teaching methods with 60 students at the technical faculties in Russia. For the study objective, the used tool was a test to collect data. According to the results, pupils who learned through the communicative approach had the best grades, followed by those who studied directly, and those who used the grammar-translation method performed the least well. The American Council on Teaching Foreign Languages suggests best practices for second language classes. Kuhlman (2017) looked at these methods. He identified six fundamentally sound instructional strategies, including the usage of the target language, communicative activities, context-based grammar, fair criticism, reverse engineering, and the application of authentic materials. In their 2018 study, Rahman et al. compared two ESL teachers’ views and actual practices concerning communicative language teaching in a Bangladeshi school. Used instruments were semi-structured interviews and observation to collect data. The results showed that the instructors did hold a sophisticated set of views, but these beliefs were not necessarily manifested in their classroom actions. Most importantly, the teaching practices prevalent in the classroom were communicative activities, deductive teaching methods, and a focus on memorizing grammar and vocabulary. Jansem (2019) examined the teaching practices used in communicative language teaching classes. Eight Thai instructors participated in the study, and the data were collected through classroom observations and semi-structured post-teaching interviews. The results showed that communicative language teaching practices involved four standard features: encouraging “small talk” in the target language, starting the lesson with a lead-in and presentation strategy, responding positively to students’ linguistic errors, and emphasizing semi-communicative activities. Khalil and Semono-Eke (2020) investigated the most effective and practical teaching techniques for general English and the English language for specific purposes in the Saudi context. Sixty-three English teachers from various Saudi Arabian universities completed an open-ended questionnaire. The findings indicated that English language instructors preferred to combine other teaching techniques with communicative language teaching.

To conclude, previous research has focused on EFL teaching practices from a general perspective. Few studies, perhaps, have paid attention to the specific instructional methods and techniques that EFL teachers must acquire and teach to their students to ensure comprehensibility, that is, successful language learning and use. Students must understand, interact with others, and use the target language. Highlighting the existing gap, this study attempted to identify the teaching practices that facilitate language comprehensibility for students when used by tertiary EFL teachers. Furthermore, the study examined the use of EFL teaching comprehensibility practices concerning the variables of the teacher’s gender and years of teaching experience. Hence, the statement of the problem is formulated in the following research questions:

1. To what extent do teachers practice language comprehensibility in an EFL context?

2. Are there any differences in teachers’ methods of practicing language comprehensibility in an EFL context due to gender?

3. Are there any differences in teachers’ methods of practicing language comprehensibility in an EFL context due to years of experience?

Materials and methods

Research design

The study aimed to identify tertiary EFL teachers’ practices of teaching language comprehensibility. It also correlated the sample’s responses with their gender and years of teaching experience. Therefore, the researchers used the descriptive-correlational approach to gather and evaluate data to describe the relationship among the variables and how one phenomenon is related to another (Lappe, 2000). Obeidat et al. (2014) define the descriptive-correlational approach as that which studies a specific phenomenon by surveying the opinions of all members of the research population or large samples of them. It aims to describe and interpret the phenomenon quantitatively or qualitatively in terms of its nature and degree of occurrence.

Participants

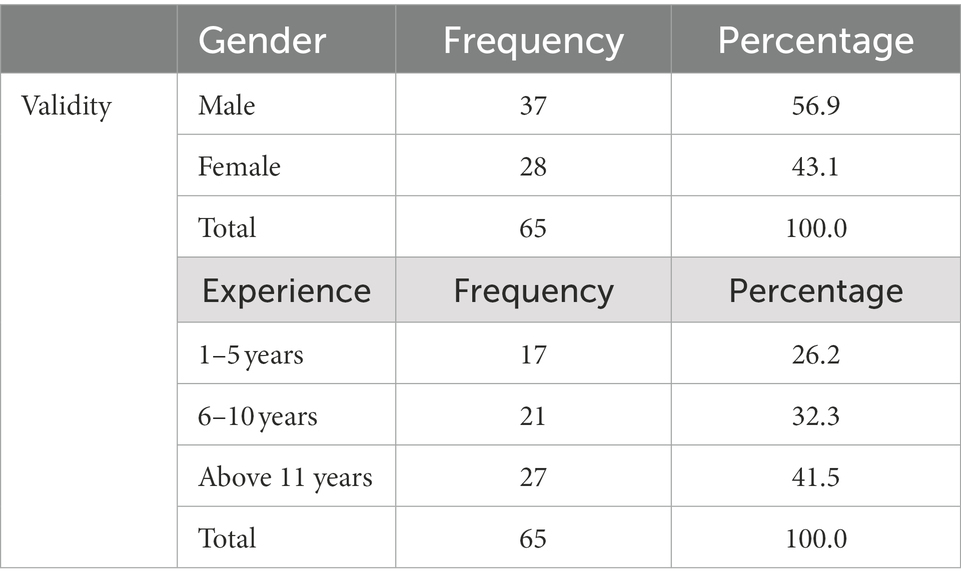

The study consisted of 85 EFL tertiary teachers at Najran University, Saudi Arabia in the academic year 2021–2022. They teach English as a foreign language in the university’s various colleges, including the College of Languages and Translation, Preparatory Year, and the Applied College. The faculty members are of different nationalities, including Saudi, Jordanian, Yemeni, Egyptian, Indian, Pakistani, Sudanese, and Algerian. They hold bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate degrees in various disciplines such as the English language, English language teaching, translation, applied linguistics, and linguistics. The study sample was drawn conveniently; an electronic link for the study instrument (questionnaire) was created and circulated to the targeted group. The link was made available for 2 weeks to receive responses. The participants’ consent form was shared and obtained online. Before the participants completed the questionnaire, they were asked to read the consent form and to express their wish to participate in the study. Those who agreed to participate in the study reached 65, representing 76.5% of the study population. Table 1 shows the distribution of the study sample according to the demographic information utilized in the current study.

Research instruments

The study targeted tertiary EFL teachers’ practices of teaching language comprehensibility. Therefore, the researchers surveyed theoretical literature and previous studies related to the topic of the study. The questionnaire of the current study was elaborated from Glisan and Donato (2017). In its initial version, the closed-item questionnaire consisted of 15 items distributed under three domains on a five-point Likert scale (Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree). The first domain was devoted to comprehensible language and covered seven items. The second domain was about contexts for comprehension and included four items. Finally, comprehensible interactions with learners came with four items. Also, there was a section on the participants’ demographic information: gender and years of teaching experience.

Validity of the study instrument

Face validity

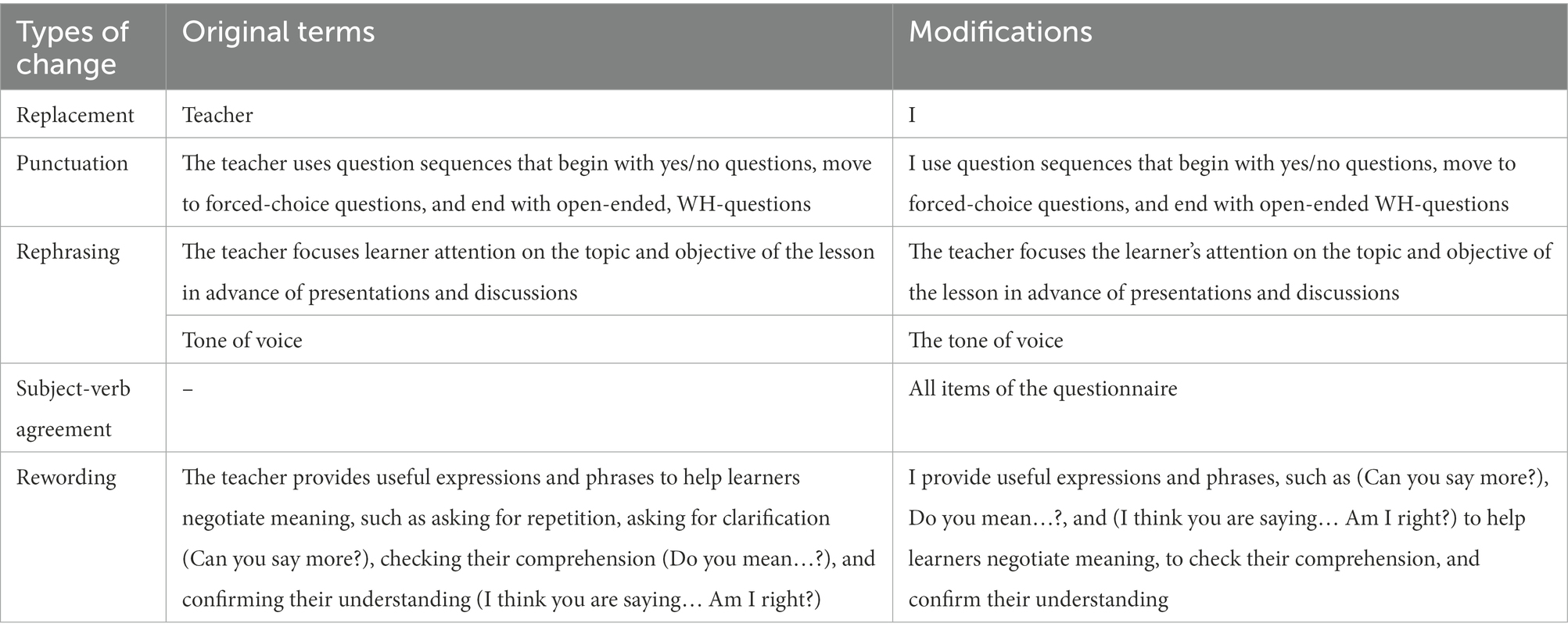

The questionnaire’s validity was verified by presenting it to five experienced faculty members of the College of Languages and Translation at Najran University. They specialize in English language teaching and learning. Their directions and suggestions included adding, replacing, deleting, and modifying inappropriate items. The experts also ensured that the wording and language were precise, and the questionnaire was free from spelling and typographical errors. In addition, the experts made sure the questionnaire’s applicability in the Saudi context. Suggestions, enjoying a high percentage of agreement by the experts, were considered. The experts’ suggested modifications are shown in Table 2.

Internal consistency

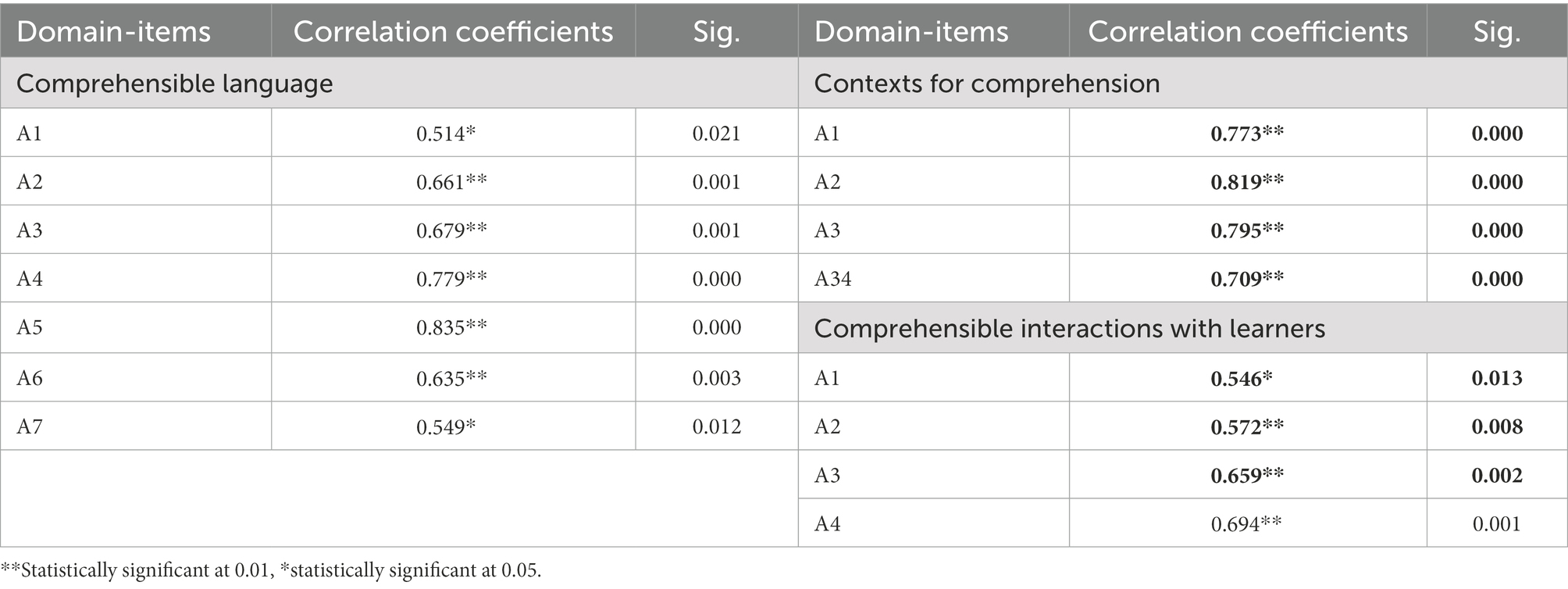

The study instrument was applied to an exploratory sample of 20 faculty members outside the study sample. Items’ correlation to the domain’s overall score was determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Also, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the scale domains and overall score was evaluated. Table 3 depicts the results.

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the items and the domain’s overall score were statistically significant at 0.01 or 0.05, as shown in Table 3. The items of the first domain, which measure “comprehensible language,” had correlation coefficients between 0.514* and 0.835** with the domain’s overall score. The items of the second domain (contexts for comprehension) and the domain’s overall score had correlation coefficients that ranged from 0.709 to 0.819. The items of the third domain—comprehensible interactions with learners—had correlation values ranging from 0.546* to 0.694** with the domain’s overall score. All values of the items were of statistical significance with a 0.05 threshold or lower. Also, Pearson correlation coefficients between the scale’s overall score and domains as displayed in Table 4.

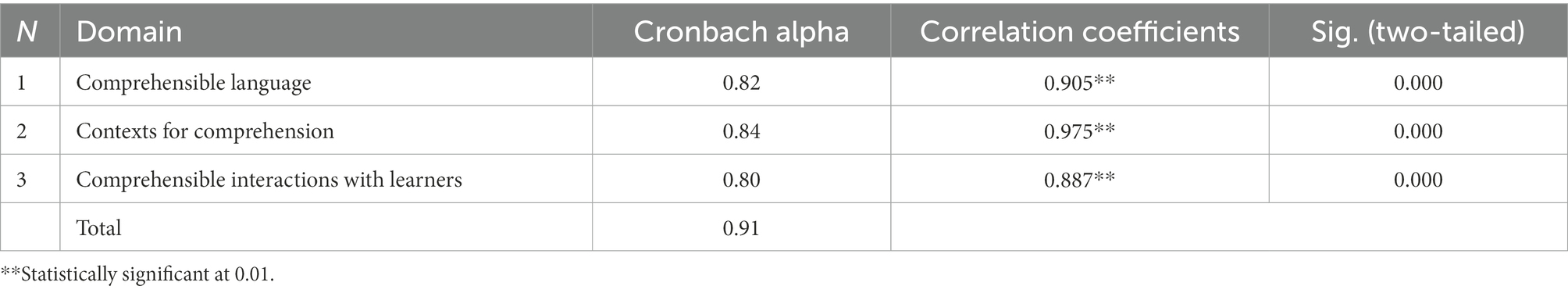

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the domain and scale total scores were statistically significant at 0.01, as shown in Table 4. With a significance threshold of 0.00, Pearson correlation values ranged from 0.887 to 0.975. As a result, the researchers confirmed the validity of the study tool.

Reliability of the study instruments

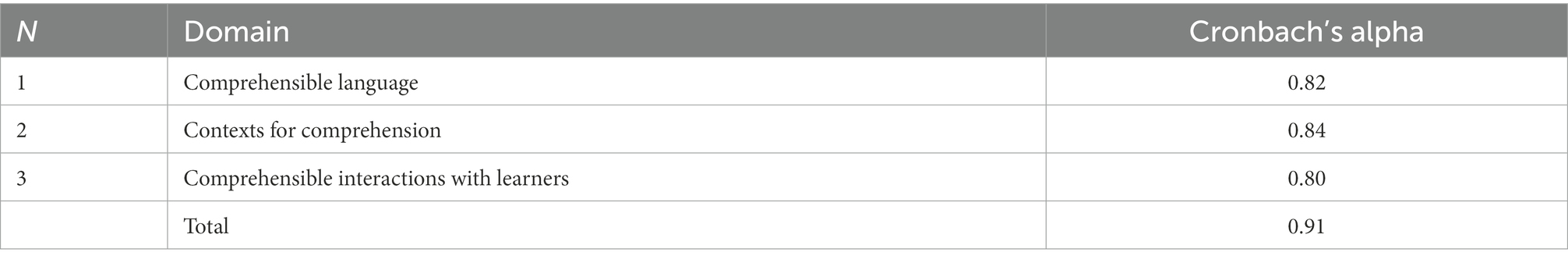

The researchers extracted the reliability coefficients of the domains and the total scale using Cronbach’s alpha equation. Table 5 displays the results.

According to Table 5, the reliability coefficient using Cronbach’s alpha of the total score of the study scale was 0.91. The reliability coefficients of the scale domains ranged between 0.80 and 0.84. Therefore, the scale is highly reliable and appropriate for the study.

Statistical processing

The researchers used the statistical software SPSS v23 to analyze the study results and answer its questions. The scale’s consistency was verified using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The reliability of the study scale was checked by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Means, standard deviations, and ranks were extracted to answer the first research question, “To what extent do teachers practice language comprehensibility in an EFL context.” The following grading was adopted to verify the scale’s items and domains to determine the degree of agreement based on the term equation: 1–1.80 = very low, >1.80–2.60 = low, >2.60–3.40 = medium, >3.40–4.20 = high, >4.20–5 = very high. The t-test for independent samples (gender variable) was used to answer the second research question, “Are there any differences in the teachers’ practices of teaching language comprehensibility in an EFL context with gender differences.” A one-variable analysis of variance (experience) was employed to answer the third research question, “Are there any differences in teachers’ methods of practicing language comprehensibility in an EFL context due to years of experience.”

Results

The means, standard deviations, and ranks of the study sample’s responses about the extent to which they teach language comprehensibility to undergraduates in an EFL context were extracted. Table 6 predicts the results.

Table 6 shows that EFL teachers taught language comprehensibility in the EFL context at a very high level (M = 4.23, SD = 0.494). Specifically, the second domain (contexts for comprehension) scored the highest (M = 4.30, SD = 0.466) followed by the third domain (comprehensible interactions with learners) (M = 4.28, SD = 0.506). The first domain (comprehensible language) came last (M = 4.16, SD = 0.605). According to the results in Table 6, the standard deviations of the domains and the total scale were relatively low. This result indicates that the responses were homogenous. That is to say, EFL teachers agree on the practices of language comprehensibility in the EFL context. At the domain level, context and interaction for comprehension scored very high (M = 4.30, 4.28, SD = 0.466, 506) with language comprehension scoring high (M = 4.16, SD = 0.605). See Tables 2–8 for more details.

Gendered-based teachers’ practices of language comprehensibility

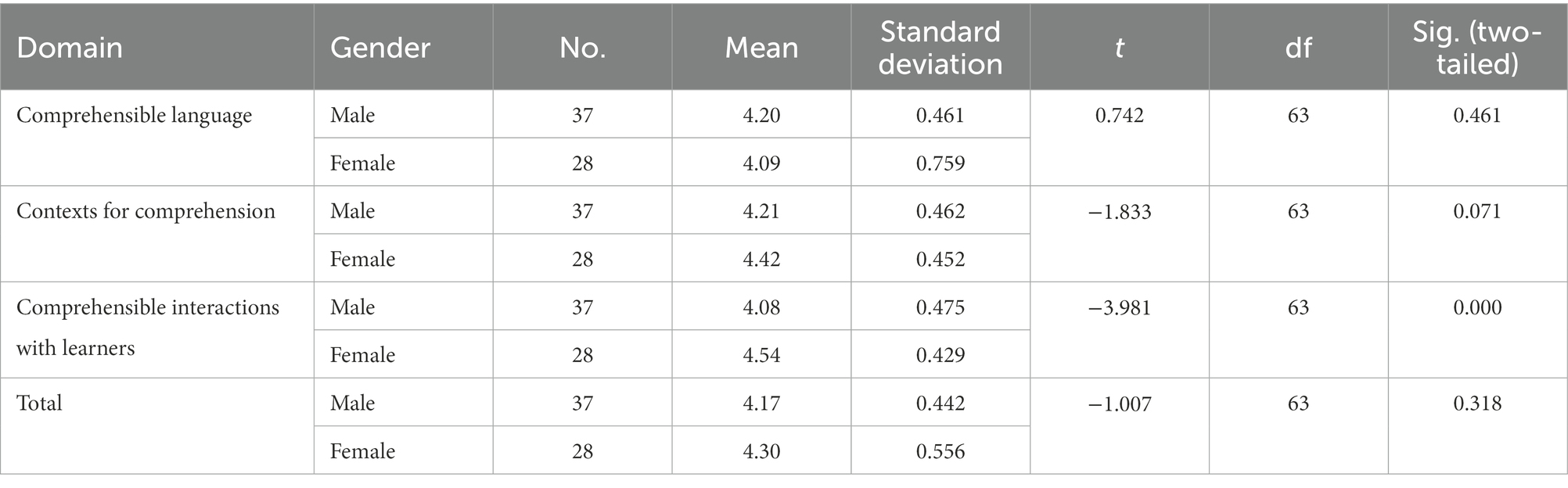

The collected data were computed using a t-test to show differences in tertiary teachers’ practices of teaching language comprehensibility to undergraduates in an EFL context due to gender. Table 7 shows the results.

According to Table 7, there were no gender-based variations in the study sample’s responses that were statistically significant at 0.05. The results showed no differences in all domains and the total scale, except for the third domain, in which there were differences in favor of females.

Teaching experience-based teachers’ practices of language comprehensibility

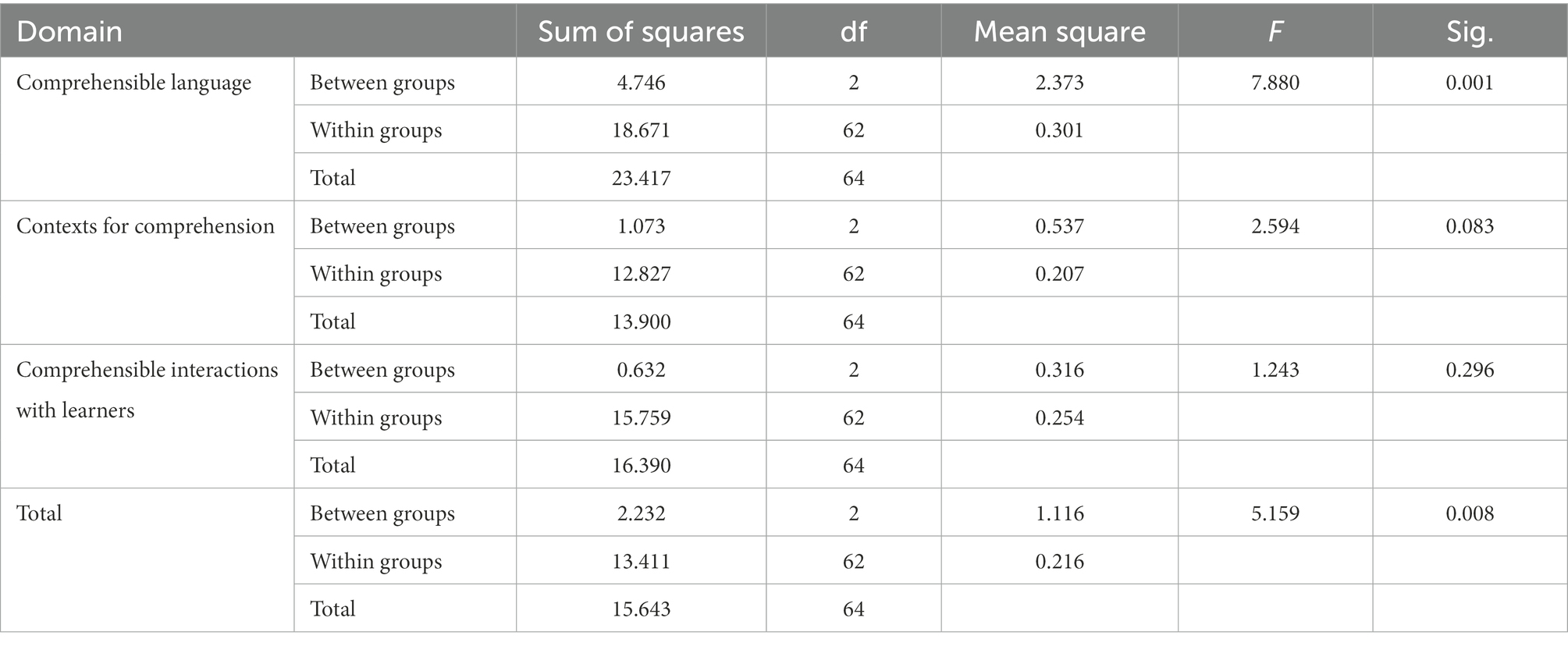

A one-way ANOVA variance analysis was used to show the significance of differences between the responses based on years of experience.

Table 8 illustrates significant differences at the level of 0.05 between the means of the responses in teaching language comprehensibility to undergraduates in an EFL context according to years of experience. The differences were shown in all domains and the total degree of the scale except for the third domain. Multiple comparisons using Scheffe’s test were used to show the statistical significance of these differences as depicted (See Supplementary Appendix B). The analysis showed statistical differences between the methods used to teach language comprehensibility to undergraduates in an EFL context between the participants with 1 to 5 years of experience and those above 11 years. The significance was highest for those with the most years of experience.

The main findings of the study are summarized as follows:

– Tertiary EFL teachers practiced teaching language comprehensibility at a very high level.

– There were no significant differences in the means of the responses in teaching language comprehensibility to undergraduates in an EFL context regarding gender.

– There existed differences in the means of the responses about teaching language comprehensibility based on years of experience with the teachers with the most years of experience showing the most significant difference.

Discussion

The current study aimed to identify tertiary EFL teachers’ practices of teaching language comprehensibility to maintain their students’ understanding, interaction with, and use of the English language. The results are discussed question-wise.

The first research question: To what extent do teachers practice language comprehensibility in an EFL context?

The data analysis showed that the tertiary EFL teachers practiced teaching language comprehensibility at a very high level. While context and interaction for comprehension scored very high, language comprehension scored high. These results indicate that EFL teachers are aware of and use language comprehensibility practices because they believe in their effectiveness in helping students understand, interact with, and use the English language. The results could be attributed to teaching experience and training courses that teachers received during their service. In general, these results are consistent with Intarapanich (2013) study, which showed that students who learned using the communicative method scored the highest marks on tests. The results further align with Rahman et al. (2018) study, which revealed that communicative teaching practices were prevalent in the Bangladeshi classroom. Similarly, Jansem (2019) showed that communicative language teaching practices were found to share specific teaching and learning environments, such as verbal interaction in English through encouraging (small talk) and starting the lesson with a lead-in and presentation strategy. Also, they included responding positively to students’ linguistic errors and emphasizing semi-communicative activities. In addition, Khalil and Semono-Eke (2020) indicated that English language instructors preferred combining other teaching techniques with communicative language teaching. Further, Kosar and Dolapçıoğlu (2021) highlighted teachers’ use of interactively learning activities to maximize their students’ English learning.

The second research question: Are there any differences in teachers’ methods of practicing language comprehensibility in an EFL context due to gender?

The results showed no significant differences existed in the means of participants’ responses in teaching language comprehensibility to undergraduates in an EFL context regarding gender. These results mean that the variable of gender did not play any role in varying participants’ views of teaching language comprehensibility practices. This result could be due to the EFL teachers’ similar contextual conditions, such as physical and social concerning curriculum, teaching practices, and aids and teaching approaches, namely the communicative teaching approach. This result is not line with that by Saito et al. (2022) concluded that a variety of nonlinguistic elements such as speaker, age, gender, and microphone may affect automated speech recognition.

The third research question: Are there any differences in teachers’ methods of practicing language comprehensibility in an EFL context due to years of experience?

There were differences in the means of the responses about teaching language comprehensibility based on years of experience with the teachers with the most years of experience showing the most significant difference. This result means that the teaching experience played a role in varying the participants’ views on teaching language comprehensibility. The teachers who had more years of teaching experience surpassed employing language comprehensibility practices than their peers who had less teaching experience. This result may be because of the accumulative teaching experiences that EFL teachers acquire through their working years, in which they are more exposed to different teaching practices and curricula of English language skills. The current result accords with Kosar and Dolapçıoğlu (2021) study, which indicated significant differences in EFL teachers’ beliefs concerning teaching practices attributed to teaching experience.

Conclusion

The study focused on EFL teachers’ teaching practices concerning language comprehension, interaction, and context. Furthermore, EFL teachers’ practices of teaching language comprehensibility correlated with their gender and years of teaching experience. The results showed that EFL teachers used comprehensible teaching practices at a high level. No difference existed in the teaching practices according to gender; however, the teacher’s level of experience was a significant variable for the high years of experience. These results imply that students need to identify the role of teaching practices on comprehensibility in their language comprehension, interaction, and use to achieve better learning outcomes. Considering the results of the present study, the researchers suggest paying more attention to integrating language comprehensibility practices in EFL contexts through training courses that enhance these strategies.

Limitations and recommendations

The current study focused only on EFL teachers’ foreign language comprehensibility teaching practices to facilitate students’ language comprehension, interaction, and use. Also, the present study was applied at the tertiary level in one university in Saudi Arabia; therefore, the generalization of results may not apply. In addition, this study was quantitative; a closed-item questionnaire was used to collect data; therefore, the reliability of the data depended on the participants’ seriousness in answering the questions since no other instruments were used to triangulate the data. Further research is suggested on examining the effectiveness of comprehensibility teaching practices on EFL students’ language proficiency level from their point of view.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee Deanship of Scientific Research, Najran University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AA and MN designed the study and collected and analyzed the data. KA-M drafted and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Najran University for funding this work under the Research Groups Funding program grant code (NU/RG/SEHRC/11/1).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc. 2022.1068628/full#supplementary-material

References

Ball, D. L., and Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 60, 497–511. doi: 10.1177/0022487109348479

Friedrich, M. C. G., and Heise, E. (2019). Does the use of gender-fair language influence the comprehensibility of texts? An experiment using an authentic contract manipulating single role nouns and pronouns. Swiss J. Psychol. 78, 51–60. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185/a000223

Glisan, E. W., and Donato, R. (2017). Enacting the work of language instruction: High-leverage teaching practices. American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, Alexandria, VA.

Hasan, A. S. (2008). Making input comprehensible for foreign language acquisition. Damascus Univ. J. 24, 31–53.

Intarapanich, C. (2013). Teaching methods, approaches and strategies found in EFL classrooms: a case study in Lao Pdr. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 88, 306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.510

Jansem, A. (2019). Teaching practices and Knowledge Base of English as a foreign language teachers’ communicative language teaching implementation. Int. Educ. Stud. 12, 58–66. doi: 10.5539/ies.v12n7p58

Khalil, L., and Semono-Eke, B. K. (2020). Appropriate teaching methods for general English and English for specific purposes from teachers’ perspectives. Arab. World English J. 11, 253–269. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol11no1.19

Kosar, G., and Dolapçıoğlu, S. D. (2021). An inquiry into EFL Teachers' beliefs concerning effective teaching, student Learning and development. J. Pedagog. Res. 5, 221–234. doi: 10.33902/JPR.2021371747

Kuhlman, K. (2017). Best practices in foreign language Learning [unpublished Master's thesis]. Capstone Projects, Northwestern College: Orange City. Available at https://nwcommons.nwciowa.edu/education_masters/61/ (Accessed September 15, 2022).

Kuznetsova, E. M. (2015). E‑volution of foreign language teaching methods. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 6, 246–253. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n6s1p246

Lampe, D. (2022). Effective teaching strategies for an up-and-coming science teacher [unpublished master's thesis]. Western Oregon University, Monmouth, Oregon. Available at https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/205 (Accessed September 6, 2022).

Lappe, J. M. (2000). Taking the mystery out of research: descriptive correlational design. Orthop. Nurs. 19:81.

Learning, A. (2002). Instructional strategies; health and life skills guide to implementation (K–9). Alberta Learning, Alberta.

Macsuga-Gage, A. S., Simonsen, B., and Briere, D. E. (2012). Effective teaching practices: effective teaching practices that promote a positive classroom environment. Beyond Behav. 22, 14–22. doi: 10.1177/107429561202200104

Maquire, E. A., Frith, C. D., and Morris, R. G. M. (1999). The functional Neuroanatomy of comprehension and memory: the importance of prior knowledge. Brain 122, 1839–1850. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.10.1839

Obeidat, T., Adas, A., and Abdel-Haq, K. (2014). Scientific research: Its concept, tools and methods. Dar Al-Fikr.

Rahman, M. M., Singh, M. K. M., and Pandian, A. (2018). Exploring ESL teacher beliefs and classroom practices of CLT: a case study. Int. J. Instr. 11, 295–310. doi: 10.12973/iji.2018.11121a

Saito, K., Macmillan, K., Kachlicka, M., Kunihara, T., and Minematsu, N. (2022). Automated assessment of second language comprehensibility: review, training, validation, and generalization studies. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis., 1–30. doi: 10.1017/S0272263122000080

Sarode, R. D. (2018). Teaching strategies, styles and qualities of a teacher: a review for valuable higher education. Int. J. Curr. Eng Sci. Res. 5, 57–62.

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 15, 4–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X015002004

Simpson, V. (2021). Why comprehensible input is vital for foreign language learning. Language Kids World https://languagekids.com/why-comprehensible-input-is-vital-for-foreign-language-learning/ (Accessed August 29, 2022).

Soga, O. (2000). Education [unpublished manuscript]. National Teachers’ Institute (Study Center): Keffi.

Sousa, D. A. (2011). How the ELL brain learns (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA, United States: Corwin Press, doi: 10.4135/9781452219684.

Swain, M. (1985). “Communicative competence: some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development,” in Input in second language acquisition. eds. S. Gass and C. Madden (Rowley, MA: Newbury House), 235–257.

Tanjung, F. (2022). EFL teachers’ pedagogical practices based on their perception during Covid-19 pandemic. IJOTL-TL 7, 1–11. doi: 10.30957/ijoltl.v7i1.702

Thrasher, T. (2022). The impact of virtual reality on L2 French learners’ language anxiety and oral comprehensibility: an exploratory study. CALICO J. 39, 10–1558. doi: 10.1558/cj.42198

Troyan, F. J., Davin, K. J., and Donato, R. (2013). Exploring a practice-based approach to foreign language teacher preparation: a work in Progress. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 69, 154–180. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.1523

Tulbure, C. (2012). Learning styles, teaching strategies and academic achievement in higher education: a cross-sectional investigation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 33, 398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.151

Keywords: English as a foreign language, language comprehensibility, teaching practices, tertiary level, classroom, teachers, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Alzubi AAF, Nazim M and Al-Mwzaiji KNA (2023) Teaching practices for English as foreign language at the tertiary level: A comprehensibility perspective. Front. Educ. 7:1068628. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1068628

Edited by:

Fan Fang, Shantou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jamal Kaid Mohammad Ali, University of Bisha, Saudi ArabiaAman Rassouli, Bahçeşehir Cyprus University, Cyprus

Mohammad H. Al-khresheh, Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2023 Alzubi, Nazim and Al-Mwzaiji. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohd Nazim, ✉ bmF6aW1zcGVha2luZ0B5YWhvby5jby5pbg==

Ali Abbas Falah Alzubi1

Ali Abbas Falah Alzubi1 Mohd Nazim

Mohd Nazim