- Faculty of Education, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

Teachers in township schools are vulnerable because of the low socio-economic conditions of the communities in which their schools are located. Such factors coupled with personal challenges can have a negative impact on their health. The aim of this research was to investigate the value of health-promoting leadership (HPL) in township schools. A qualitative approach was followed to gather information about the latter. Data were gathered by means of diary keeping, recording and individual interviews. Sixteen participants participated in the research and were engaged in the research for 4 months. A total of 32 interviews were conducted; each participant was interviewed twice. The findings revealed that HPL was perceived as relevant to the participating schools as it enhanced healthy working conditions, such as a health-promoting culture, health awareness and close working relationships (community). It is recommended that more attention be given to HPL, focusing on physical environments and safety and providing social support and health awareness programs to enhance teachers’ physical and mental health.

Introduction

In South Africa, “township” schools are associated with negative narratives and historical baggage due to historical circumstances. During the Apartheid regime, “townships” were very unstable because of political struggles and unrest at the time. In 1976, youth upheavals led by student movements erupted in “township” schools to liberate educational provisioning in South Africa. Constant police raids rendered most schools dysfunctional, and learners explored enrolling in urban schools (Monyooe, 2017). Townships are residential areas in South Africa that originated as racially segregated, low-cost housing developments for Black laborers to remain closer to their places of employment in cities and towns (Mampane and Bouwer, 2011). Today, township life is mostly associated with poverty, crime and violence, and it has even been equated to “war zones” when the safety of residents becomes compromised (Leoschut, 2006). Townships in South Africa remain largely poor and black.

Township schools are very challenging and difficult to manage compared with many schools in the suburbs and in rural areas. This complexity can be ascribed to the socio-economic conditions of communities in which township schools are located. Township schools are especially vulnerable due to unsafe conditions and threats of violence because of their location (Xaba, 2006). These schools are situated in areas with high poverty, unemployment and high rates of crime and violence. Research confirms the occurrence of violence, crime and adverse conditions in South African township schools (Burton, 2008). Teachers become targets of violent activities in such contexts. A study by Shields et al. (2015) revealed that teachers in townships in South Africa experience high levels of psychological distress, which they perceived as related to their exposure to violence and aggression. Additionally, township schools are still underresourced and have numerous administrative problems (Zoch, 2017). The issue of insufficient resources is aggravated by the fact that nearly all schools in poor communities are no-fee schools, rendering little prospect of supplementing subsidies from the Department of Basic Education (DBE) or reducing overcrowding. They are, therefore, allocated more funding than schools in affluent areas. However, the funds are not meant to be used for hiring teachers (South Africa, 1996) to address teaching capacity. The teacher–learner ratio is much higher than in schools in wealthier areas. Teachers — specifically those who work in underresourced contexts — experience negative wellbeing (Wessels and Wood, 2019). Overcrowdedness can contribute to unrelenting or continuous teacher stress, leading to poor health and lack of wellbeing. According to Fu et al. (2022), health-promoting leadership (HPL) can alleviate health complaints caused by citizenship fatigue by helping teachers to replenish their personal resources. Daniel and Strauss (2010) regard schools in townships in South Africa as highly stressful workplaces. HPL enhances the health of subordinates in several ways. First, HPL is integral to developing health-promoting environments (Skott, 2022), which may lead to enhanced teacher performance, commitment and satisfaction. Second, leaders may also change working conditions by creating a supportive working atmosphere and nourishing resources that foster employee health (Bregenzer et al., 2019). Third, in a study conducted by Velasco et al. (2022), it was recognized that school principals had a key role to play in promoting care in relationships and flexibility across the entire community. In this context, the important role of in-school leadership and management practices of principals has repeatedly been emphasized (Rowling and Samdal, 2011; Dadaczynski and Paulus, 2015). The fact that leadership aims to stimulate cultural change based on shared values and visions (Samdal and Rowling, 2011) proves the need for every generation of school leaders to confront the dominant forces of tradition to take schools and school systems in a new direction (Bogotch, 2011). This is also relevant to school leaders who strive to initiate, support and sustain health-promoting change processes in their school. Thus, continued and effective schoolwide health interventions that can give rise to sustained change, and improvement in the health and wellbeing of the school community are unlikely without good principal leadership.

Daily, numerous South African children travel to schools that are relatively far from their homes (Lancaster, 2012) in search of better education, yet many schools in the townships are still crowded. These schools (mostly) cater to the poorest learners who cannot attend schooling elsewhere (Altonji and Mansfield, 2011). In addition to the high enrolment numbers, there is performance pressure in township schools; some schools perform well academically, and others underperform. For instance, a township in Ekurhuleni — one of the top three performing high schools — had 1,041 learners enrolled in 2018; Raymond Mhlaba — a secondary school in the Johannesburg North district — had a pass rate of 100% in 2016, 98% in 2017, and 100% in 2018, with 1,021 learners enrolled in the latter year (Dlamini, 2018). In the Free State, the top-performing school in the province for 2018 had 2,700 learners enrolled and obtained a pass rate of 98%. This school was situated in a township. In addition, two of the three schools that attained a 100% pass rate in the Sedibeng District in 2018 are situated in a township, and one of them had 1,280 enrolled learners (Department of Basic Education [DBE], 2018).

This scenario has raised hope that township schools can overcome the difficulties they face. However, although this can be applauded, the above-mentioned is a small fraction of the schools that can achieve good results, which necessitates strategies that would enable more township schools to perform better. Teachers in township schools are under pressure to produce good results. The inability to perform effectively has been associated with demotivation and demoralization of both teachers and learners. High-performance pressure tends to signify high risk and heavy demand, suggesting that the current performance is insufficient and the level of performance needs to be improved through various means (Li et al., 2018). If teachers could enhance their health and wellbeing, they would be better prepared to fulfill their role as supportive, caring teachers and address the challenges that arise from the circumstances in which they teach (Fredrickson, 2013). Good leadership that recognizes and supports teachers’ efforts is crucial to cultivating a health-promoting culture and climate (Horstmann and Eckerth, 2016). As leaders can influence critical working conditions, they are often perceived as key to creating successful, healthy workplaces (Aitken, 2007). Moreover, research on health-promoting leadership indicates that this holistic view of health can optimize nurturing outcomes, such as work-related health, job satisfaction, quality of care, and patient safety (Akerjordet et al., 2018). The same can be said for teaching outcomes.

In search of a turnaround strategy that could lead to more township schools that are effective and better performing, the researcher investigated the relevance of HPL, drawing on Eriksson et al.’s (2010) postulation of the importance of developing HPL as a contribution to organizational capacity building for health-promoting workplaces. Research on HPL indicates that more knowledge is needed about how leaders really succeed in crafting healthy workplaces and healthy employees (Skarholt et al., 2016). As HPL creates a culture of health-promoting workplaces and values and inspires and motivates employee participation in this instance (Žižek et al., 2017), it becomes important to investigate its relevance to teachers in township schools. Prior identification of the elements of HPL relevant to township schools can lead to a solution to enhance healthy working conditions for teachers. Although the relevance of HPL to healthcare settings (Akerjordet et al., 2018) and organizations or industries (Skarholt et al., 2016) has been investigated, literature on the importance of HPL in education is scant. Relevance in this study is defined as the value HPL might add to health promotion in township schools to the benefit of teachers who work in such contexts. The two questions that guided this research were as follows: What elements of HPL are relevant to township secondary schools? What is the relevance of HPL to teachers in township schools?

Background

There is high teacher turnover in South Africa, which Mampane (2012) regards as a crisis. Literature indicates that teacher turnover can be ascribed to several factors, including insufficient supportive and communicative leadership. According to Milner and Khoza (2008:4), teachers’ stress levels are extremely high, and it seems that little has been done in the education sector to combat or ameliorate this issue. Moreover, the DBE has been struggling with a high rate of teacher absenteeism, negligence of duties and alcohol abuse (Bipath et al., 2019), which have a negative impact on teaching and learning and the academic performance of learners. Research by the Centre for Development and Enterprise (Fengu, 2017) found that 40% of teaching time is wasted due to teacher absenteeism and teachers skipping class. Moreover, a study conducted by The New Age (2017) ascribed teacher absenteeism to sick leave that accounted for 66% of absenteeism cases. Moreover, although the phenomenon of teacher absenteeism is a norm in developing countries, in South Africa, it is aggravated by the burden of HIV and AIDS. The high number of orphans and vulnerable learners in township schools weighs on teachers who must support them in every way. Unlike in many developing and developed countries, “the HIV and AIDS pandemic in South Africa has been a key driver for the emergence and development of EAPs (employee assistance program) in both public and private sectors” (Govender and Vandayar, 2018:14). As social ills remain unabated and such an environment can have a major impact on teachers’ health, leadership in township schools needs to look for ways to boost staff morale by minimizing stress, enhancing recovery and reducing the risk of burnout to support employee health. This can be done by building and retaining a healthy and positively motivated workforce (Whitehead, 2006) and linking good leadership to employee health.

To stop this malaise, the DBE developed an employee assistance program (EAP). The EAP in education developed from a need for resources for teacher employees. The EAP is closely linked to HPL because it provides constructive assistance in the form of confidential counseling and referral of every employee who experiences personal and work-related problems (South Africa, 1999). Both the Employee Assistance Programme Association of South Africa (EAPA-SA, 2005:5) and HPL focus on the issue that such programs revolve around the identification and resolution of “productivity problems associated with employees impaired by personal concerns.” However, the EAP is based on the “troubled employee” concept, which suggests that an employee who accesses such services must be out of control, especially if they have been referred by a manager. In the education sector in South Africa, the EAP is run in schools at the district level and in some provinces, it is offered externally by outsourced services. The findings of a study conducted by Taute and Manzini (2009) on factors hindering the utilization of EAPs in the Department of Labour in South Africa revealed a link between the EAP and the disciplinary processes of the department implementing the program. HPL is more holistic as it is based on socio-ecological models aimed at improving individual as well as organizational and environmental determinants of health (Eriksson et al., 2010). Therefore, there is a need for school leaders who can form, stimulate and change the work environment substantially by leading in a health-promoting manner.

The arguments advanced in this article are that HPL is necessary for the effectiveness of township schools and that perceptions of relevance are important in HPL. As there may be different perceptions of HPL, leaders must take cognizance of the implication of consistent attitudes toward HPL.

Conceptual framework

HPL originates from “supporting good leadership in general and improving general working conditions of managers” (Eriksson et al., 2011). Thus, good leadership in school health promotion is paramount. Good leaders promote employee health through supportive behavior, such as individual consideration, positive feedback (Winkler et al., 2015) and recognizing employees’ achievements (Gurt et al., 2011). Skarholt et al. (2016) concur and add that health-promoting leaders are hands-on and inclusive. A supportive leadership style means that the most important aspect of HPL is to support, motivate (Eriksson, 2011) and inspire employees. Leaders must establish readiness for change within the school community and act as role models in the change process (Dadaczynski and Paulus, 2015:266). Therefore, it seems the concept of HPL is often used to link ideas about good leadership to employee health. Health-promoting leadership may improve performance at the employee, team and organizational levels (Yao et al., 2021). This research focused on employee health and wellbeing at the organizational level.

Health-promoting leaders have the important task of organizing health-promotion activities and developing a health-promoting workplace (Eriksson et al., 2011). They must initiate and support activities to promote the health and work satisfaction of employees (Eriksson, 2011). Specific leadership behaviors entail health communication, setting agendas for workplace health promotion, and motivating and inspiring employees to participate in health-promotion activities (Gurt et al., 2011). Such leadership is “concerned with creating a culture for health-promoting workplaces and values” (Eriksson et al., 2010:111). Developing a health-promoting workplace is based on a wider view that stresses the responsibility of leaders to develop a healthy physical and psychosocial work environment (Eriksson, 2011).

The concept of perceived relevance refers to the degree to which individuals perceive an object to be self-related or in some way instrumental in achieving their personal goals and values (Celsi and Olson, 1988). According to Keller (1987:3), people are motivated to engage in an activity “if it is perceived to be linked to the satisfaction of personal needs (the value aspect) and if there is a positive expectancy for success (the expectancy aspect).” Relevance involves the process and value of the outcome of HPL initiatives. While no formal definition for perceived relevance has been proposed, here it is argued that relevance is a perception that HPL (broadly defined) is linked to township teacher effectiveness. Drawing on this definition, this study defines the perceived relevance of HPL as the extent to which school managers and teachers perceive it to be self-related or useful in health promotion, resulting in achieving an enhancing effect on teaching and learning in township schools. In this research, relevance is conceptualized as school managers’ and teachers’ beliefs that HPL would provide them with a health value and that value comes from both how leadership is provided and the value of the health interventions and initiatives. Therefore, perceived relevance is subjective and may differ greatly between participants.

Research method

A qualitative approach was used to explore the perceptions of school managers and teachers of HPL in a township school context. This study was broadly phenomenological. It aimed to represent the participants’ lived experiences of HPL. Phenomenological research requires the researcher to enter into dialog with others to gain experiential descriptions from which transcripts are derived and examined (Van Manen, 2013).

Research participants

A purposive sampling method was chosen to identify research participants. This sampling method was chosen to match the sample to the aim of this research. The selection criteria were as follows: township high schools (non-fee paying); schools that had not obtained a matric pass rate of above 70% for three successive years (n = 3); 800+ learner enrolment; and schools that were performing well above 80% each year (n = 2) with 1,000+ learners. Regarding the latter, I chose schools in districts in two provinces: Limpopo (LP) and Free State (FS). As the data were readily available on the Internet, I decided to approach the schools, and they were willing to participate. The schools that had not performed above 70% were not easy to select as there were many such schools in Gauteng (GP). The decision was made to focus on one district in GP, namely Sedibeng West, due to its poor performance compared with other districts in the province.

Another inclusion criterion was school principals who completed the second cycle of continuing professional development (CPD). It was assumed that these principals had an opportunity to be trained in health promotion. Therefore, if the principal did not complete the second cycle, the school was not selected for the research, even if the school initially agreed to participate. All principals in this study had attended and completed the second cycle of CPD.

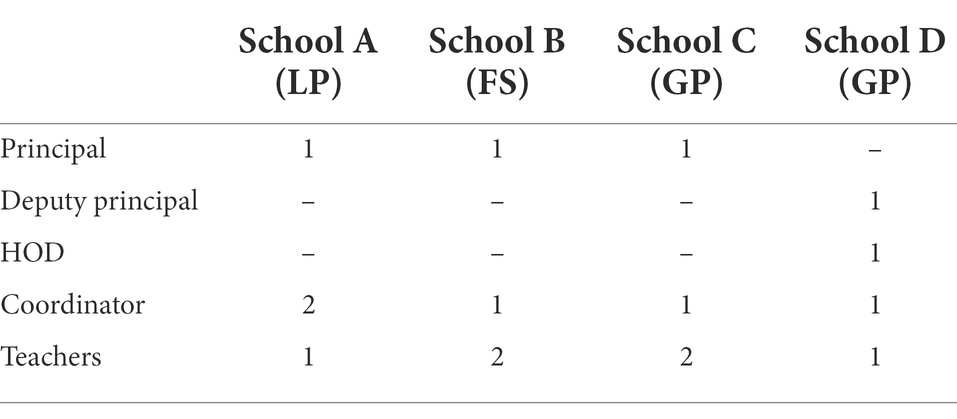

Three groups of participants were involved in this research because I wanted to obtain information from three strata: school managers; coordinators of health programs; and teachers. I recruited 20 participants from four township schools in the above-mentioned provinces of South Africa (two in G; one in LP, and one in the FS province). Sixteen were willing to participate (three principals, one deputy, one HoD, five coordinators, and six teachers). The principal of school D was not available, but the deputy was willing to participate in the research. Moreover, in the case of school D, the HoD was also a coordinator. Table 1 below indicates the number of participants from each school.

Data gathering

Two data collection methods were used: individual semi-structured interviews and diaries. In the literature, the combination of interviews and diaries as a data collection method is called the diary-interview method (Zimmerman and Weider, 1977). Thus, an interpretive micro-ethnographic research technique — in which a diary-keeping period was followed by an interview consisting of detailed questions about the diary entries — was used as the main data collection tool. The diary-interview method is participatory in nature as participants are fully involved in data gathering. Participants were encouraged to record their thoughts and feelings about health interventions for teachers and how HPL was provided in their schools. All participants were willing to keep a diary to record their observations of the endeavors of principals to create healthy workplaces and healthy employees.

As the participants had never been asked to keep diaries on health promotion, they were provided with guidelines and instructions on what they had to include and focus on. This pre-diary-keeping group session (a group of three participants from each school) was necessary to explain the research process and ensure that all participants understood their role in the data collection process. The participants were also informed that they could keep a written diary or audio and/or photo diaries (Jacelon and Imperio, 2005). All participants opted for a written diary. They mentioned that it was easier to keep a written diary on their tables where it would be easy to see every day. Thus, diaries were accessible whenever the participants wanted to make an entry. A diary-keeping pack — consisting of a notepad, my contact information, a copy of the signed consent form, and written instructions on what to record in the diary as well as prompt questions — was provided to each participant.

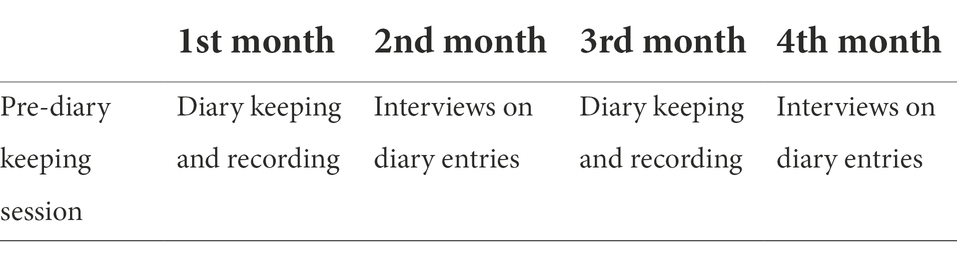

Participants were requested to participate in the research for 4 months: months one and three were for diary keeping and recording, and months two and four were for interviews on diary recordings. In the first month, the participants’ focus was on how healthy settings were created, their involvement in their creation, and their perceptions of the benefits of such settings to their health. The prompt questions for data collection in this month revolved around the process of health promotion and its value to participants. The second round of diary keeping was dedicated to the HPL of principals and its impact on participants’ health.

Individual interviews were conducted twice to allow the participants to focus on and gain greater insight into each aspect of HPL. At the end of the first month, the participants were contacted to establish their readiness to be interviewed about their diary entries. Also, they had to indicate suitable dates, times and places for the interview. Individual interviews were conducted with each participant at a place and time that suited them. After each interview, participants were reminded that they had to take notes on the second issue of the investigation at the beginning of the third month. Interviews that were conducted at the end of the second month, immediately after the first phase of diary keeping, explored two aspects: the leadership characteristics of principals and the effect they had on teachers; and the efforts made by the school managers to create healthy school environments. The second round of interviews was regarded as post-diary “debriefing” interviews (Alaszewski, 2006) as they were conducted in the fourth month toward the finalization of data collection. During these sessions, participants shared information about their diary entries, what these entries meant to them and their experiences with the diary-interview method. I conducted two interviews with each participant, which amounted to 32 interview sessions. The diaries were collected from each participant after the second interview session. Separating the two facets of HPL gave me an opportunity to explore the entries diarists had made in more depth. Table 2 below summarizes the data collection process.

Data analysis

Data analysis started immediately after the first interviews had been recorded and transcribed. The data were handled manually by reading through the transcripts and comparing the information with the video recordings and diary entries of each participant. The aim of this process was to ensure that all data were captured correctly. First, I coded the data manually. Phrases from the transcripts that reflected participants’ perspectives were then identified and synthesized to identify common structures of experiences based on the traces of visible leadership provision in health promotion and its relevance to teachers in township schools. Thus, throughout the analysis and ongoing data gathering, care was taken to allow naturalistic data to emerge (inductive analysis) and to ensure that data were not forced into pre-conceived analytical boxes as in the case of deductive analysis. After coding the data, I examined how categories related to each other and identified three themes to explain the links.

Trustworthiness

The participants had 2 months for diary keeping and entering and 2 months for interviews based on their entries. Enough time was dedicated to the thought process and preparation for the questions before the interviews were conducted. Prolonged engagement with the participants and sites is in line with Erlandson et al.’s (1993) suggestion that this kind of engagement between the investigator and participants enables the former to gain an adequate understanding of an organization and establish a relationship of trust between the parties. The timing of the interviews was appropriate in that they were scheduled not too long after the record-keeping month; thus, the information was still fresh in the participants’ minds. To ensure credibility, different sources of data were collected for triangulation. Brewer and Hunter (1989) claim that the use of different methods in concert compensates for their individual limitations and exploits their respective benefits. Another form of triangulation was the involvement of a diverse group of informants – thus, indicating triangulation of data sources.

Ethical considerations

After obtaining ethical approval from the university and identifying the schools to be included in the study, I approached the principals for permission to conduct research at their schools. Each participant had to consent to participate in the study. Each participant signed two consent forms: one for participating in the study, and the other for their diaries that were to be used for specified purposes, namely publications and presentations. I decided to adopt a form of “process consent” (Dewing, 2007) with a view that informed consent is a continuous process. Participants were asked for verbal consent at each stage of data collection. They were reminded of their right to withdraw from the research at any time.

Results

Three themes emerged from the inductive data analysis: what was done to promote healthy settings in schools; how it was done; and the challenges the participating schools faced in their health-promotion endeavors. The first two themes are based on health-promotion activities in the five schools. The extracts used below emerged from both the diaries and interviews. Codes were used to identify the participants. Codes A1, B1 and C1 were the principals; D1 was the deputy; and D2 the HoD from school D. The coordinators were A2, A3, B2, C2, and D3, and teachers were A4, B3, B4, C3, C4, and D4.

Health-promoting leadership culture

Participants said that a culture of health promotion in their schools was created and sustained by activities that were done routinely over time. This seemed to be a tradition. However, the health-promoting culture of the participating schools only focused on the provision of resources, programing designed to promote wellness, and general information on how teachers could improve health. For instance, teachers from the participating schools were motivated to attend workshops on wellness. These meetings were meant to equip them with information on how to take care of their own health. Participants said: “The workshops are not regular; we have only one or two in a year” (participant A3); “mostly wellness workshops focus on stress management” (participant B2). Principals also invited health professionals and other experts to talk to staff members about health issues. Participants confirmed this by saying: “The principal would invite a psychologist to do group counseling” (participant A4); “he tries his best to support us health-wise, we have had motivational speakers, change agents and psychologists over the years” (participant C2).

Participants mentioned that their school’s physical environment was arranged so that they could promote health. Regarding this theme, the issues of safety, a welcoming environment and access to information on health were raised. As regards safety, the schools collaborated with community members for capacity. One participant mentioned: “[Programmes] that deal with vandalism where we work with members of the community to ensure that the school is safe, this is a priority in our school” (participant A1). Another participant said, “the police help us to keep the school safe from gangsters who use nyaope [this is a street drug commonly found in South Africa; it is a mixture of low-grade heroin, cannabis products, antiretroviral drugs and other materials added as cutting agents]” (participant B1), and “we also have adopt-a-cop whereby a police officer is allocated to the school” (participant C4). The cleanliness of the surroundings and the beautification of the school environment also took priority. Participants said the following in this regard: “The surroundings are clean…. Learners pick up the trash daily” (participant C1); “we have a duty rooster to make sure that teachers monitor cleaning of surroundings after break so as to keep our environment clean” (participant C2); “there is a committee for the maintenance of the school grounds” (participant A2); “EPWP is a project of the department of public works that assist[s] with the cleaning of the schoolyard and classes” (participant D2).

Participants also agreed that there was a culture of bereavement support. It was a tradition in the participating schools to pray for bereaved staff members, help with funeral arrangements and go to the family to express condolences. Participants said the following: “Each school has its own policy, but the aim is the same: to support the bereaved staff member” (participant B3); “it really helps to know that when you are in that situation staff members will support you fully, they even attend the funeral” (participant D2); “the school managers lead this [program], one of them will convey messages of condolences to the bereaved family, I lost my husband last year, the principal was very supportive, making sure I have everything I needed, he would even phone to check on me before the funeral and what I would like staff members to help me with, very comforting” (participant A2).

Provision of health-promoting leadership

Participants indicated that supportive leadership was provided, but mainly in respect of tasks and responsibilities that teachers were entrusted with: “The principal supports learners and educators in their activities” (participant D3); “after attending meetings the principal gives feedback to us as the SMT” (participant B2); “he calls a meeting of all staff members to give feedback on the issues that were discussed in the meeting he attended” (participant C2); “the principal always enquires about how we are and the challenges we have in terms of teaching and learner discipline” (participant D4). Some principals went the extra mile by being hands-on in the implementation of some programs. This seemed to have helped them to get a better understanding of the challenges the teachers faced: “He supports by taking part in the activities and not just listening to us giving him feedback. Him taking initiative has encouraged other SMT members to do the same” (participant C4); “our principal is hands-on. He assists in monitoring, if there is a workshop he asks for reports from the attendees of the workshop and makes follow-up to ensure that [programs] are implemented as planned” (participant D2).

Some participants mentioned open communication between them, and their principals highlighted the importance of this factor in HPL: “What contributes to his success might be that he communicates with the SMT on all the [programs] that need to be implemented at school” (participant A3); “the principal plans with all the teachers, communication is important for him, he also encourages us to talk if there are challenges” (participant B2).

Three of the participating schools worked as a team. Teachers set a date at the beginning of the year to plan their subjects together. They supported each other in the teaching of topics by dividing them among themselves and as a result, one teacher taught the same topic at all three schools. These partnerships were initiated by principals and Grade 12 teachers. Participants said the following in this regard: “Helping each other with topics we are not comfortable with helps in reducing stress” (participant C3); “the support we provide for each other helps our students and us in terms of reducing the stress of teaching something one is not comfortable with” (participant D2); “we formally meet three times a year at the start of each term to plan and agree on who is the best among us in each of the topics for the term. Setting these plans in motion offload the burden on each of us, we would know exactly who is doing what” (participant A3); “such teamwork is not possible without the strong leadership of the principal, it cannot be sustainable, and I have to support it. Teaching a Grade 12 class is pressure from the beginning of the year to the end, and teachers demand more support” (participant D1); “twin-teaching works well in schools especially if the principal has a good relationship with the school[s] you want to work with, but if the school is underperforming then the district intervenes by assigning teachers who will help out with assisting teachers in the school to boost performance” (participant A1).

In the other two schools, support was based on a directive from the DBE at the national level. Therefore, it was a top–down initiative where underperforming schools (with a pass rate of less than 60% for three successive years) were mentored by principals of schools that were performing well. The principals of the latter schools would lead two schools for a period of 3 years, providing support and guidance to the SMT of the mentored school. Participants shared the following about their experiences of being mentored by principals of well-performing schools: “[I]t is a good thing to have a mentor, a principal of a good school, you expect him to guide you to improve the results” (participant B2); “it helps with reducing stress, we were demotivated, not knowing what to do, he came and revived our hope, it is not easy after having underperformed for years, you run out of ideas, he motivated us, in the following year we were starting to set high targets” (participant B4); “the only problem with a principal who is a mentor is too much focus on tasks, this reduces stress as there are plans and strategies in place, but life happens and people get sick ourselves, our loved ones, with that we are not supported much” (participant B3); “it is not an ideal situation, my ego is bruised and there are teachers who sympathize with me who will not listen to the mentor, it does not help much, the stress is added” (participant D1).

Challenges in health-promoting leadership

Participants highlighted several challenges which, in their view, rendered HPL ineffective at their schools. The first challenge was that support was selective and only focused on aspects the principal preferred: “[I]f it is a [program] that the principal likes he will support it and make sure that it happens and motivates everyone to be involved but if it is something he dislikes, he is not really active. He lets us do everything” (participant C3); “what is sometimes frustrating is that at times we try to solve a problem on our own and fail and when we go to him, he will be asking why we did not tell him from the start” (participant D3); “… if it is about projects that they like best. Like bullying in school. They will always be passionate about it, talk to parents about it, make us aware during SMT meetings about bullying that is happening in the school, and try to come up with solutions. But this does not happen in initiatives they are not passionate about” (participant A3).

Exhaustion and lack of motivation as time progressed were also mentioned as a challenge. This was not good for the beneficiaries of the programs. Participants mentioned the following in this regard: “Most [programs] start well at the beginning of the year and are monitored by the principal and the SMT but as the year goes no one is interested” (participant B4); “frankly speaking the principal will be there when we start to initiate the projects and most of the time we struggle especially if there are competitions that the learner need to go to, you have to fight with them for money, maybe if the project needs money they will help” (participant A2).

Although the EAP was not developed at the school level, participants mentioned its availability, how it was conducted, and its value. This is what they said: “The wellness [program] for teachers is available, but we prefer private health assistance, you do not want people to know about your problems, in EAP there is no privacy” (participant C1); “the principals refer the teacher that needs assistance, teachers do not just go there on their own” (participant B4); “teachers get an opportunity to be referred to specialists” (participant C4); “employee assistance [program] helps teachers that need counseling” (participant A1). However, two participants who also acknowledged the EAP’s potential to support them mentioned the flaws in how it was implemented and conducted: “The wellness policy for teachers is a good policy but it is not implemented correctly, there is no confidentiality” (participant A4); “the policy on the wellness of teachers is important but it is not working at school level, teachers are referred when they are regarded as problematic” (participant B4).

Discussion

A qualitative research method — using diary keeping, recording and individual interviews — was used to gather information on the value of HPL in township schools. Data were collected from 16 participants who were engaged in the research for 4 months. In total, 32 interviews were conducted; each participant was interviewed twice. The first finding revealed that the three elements of HPL relevant to township schools were the promotion of healthy working conditions, health awareness, and health-promoting culture. The second finding highlighted the perceived value of the factors relevant to township schools. The three factors contributed to a health-promoting workplace, focusing on both physical and psychosocial environments. This finding verifies that HPL is indeed necessary and reasonable for effective township schools, as it was perceived as instrumental in achieving personal and organizational goals. As mentioned earlier, perceived relevance is subjective. However, acknowledging that individuals have different and presumably biased perceptions of the value of HPL would reflect heterogeneity, implying consistencies in the effect of attitudes on HPL.

The school community was developed by the schools themselves and the DBE. However, the bottom–up approach — thus, the schools took the initiative to build their own supportive communities — seemed to be effective. In all four participating schools, measures were taken to reduce work-related stress; however, the workload could not be reduced due to insufficient funds. School leaders play a supportive role in such initiatives. Positive relationships were established among teachers; they supported each other by forming a community. Participants said that the stress of teaching sections of the curriculum that they were not comfortable with, was reduced, consequently promoting a healthy work environment. Thus, a positive climate was created for teachers to support each other and share the teaching load. There was a belief that HPL was relevant to promoting personal and professional development. It seems that, although the historical background of challenges in segregated schools in South Africa still exists and disputes between well-equipped and underresourced schools remain, some township schools are creating ways to deal with this by considering professional learning communities as viable to alleviate teacher stress and be effective in teaching. It is important to create healthy working conditions in township schools where there is a need to deal with health-related factors. Workplace health promotion with the support of leadership has become a central focus of more recent research on HPL (Jiménez et al., 2017).

Twin teaching seemed to be empowering. The twinning of schools’ programs — a project of the Gauteng Department of Education — was piloted in 2015 in Gauteng province. The aim was to share resources and human resources among schools to help learners, especially those in formerly disadvantaged communities, to achieve more in their education. Initially, the aim of the program was to ensure social cohesion, as former “model C” schools would be twinned with schools in townships. The term “model C” is still commonly used to describe former Whites-only schools. It is the same concept that two of the participating schools seemed to have modified as they opted to twin with schools in the same area in which they were located. A township school twinning with another school that has resources is a deviation from the norm. This could mean that there is a prospect of professional development through the twinning of township schools. This modified version of twinning (self-selected teams/partners) focused more on professional development, as teachers who taught the same subject would share skills, expertise and experiences of the subject, creating a professional learning community and providing the twinning teachers an opportunity to be capacitated. Teachers working in self-selected teams show more positive ratings of enjoyment, shared responsibility, and collective self-efficacy expectations than those in imposed teams (Krammer et al., 2018). Team teaching provides emotional support (Mandel and Elserman, 2016). The shared teaching and learning activities yielded good results, as both schools achieved a 100% pass rate and became the top performers in their province in 2018. However, it cannot be assumed that these results were solely based on team teaching, as participants indicated to have been involved in team teaching in March, June, and September — thus, they spent less time together compared to the time they spent teaching on their own. However, literature on HPL suggests that creating empowering working conditions can influence an employee’s response to the workplace and, in turn, increase organizational commitment (Franke et al., 2014; Žižek et al., 2017). It can be argued that HPL in township schools, entails being at the forefront of initiatives that cultivate supportive work environments for teachers.

The participating school managers strove to build a health-promoting culture. The latter is defined as an environment that “places value on and is conducive to employee health and well-being” (Kent et al., 2016:9). This finding is consistent with the definition of leadership, which is associated with creating a shared culture and values to inspire and motivate employees (Yukl, 2002). Participants mentioned four aspects they deemed crucial: safety measures, cleanliness of the physical environment, support in times of bereavement, and health awareness. These are multi-focused intervention strategies that might have a greater impact on employee attendance than single-focused strategies (Dellve and Eriksson, 2017). The interventions target both individual and environmental issues, addressing individual behavior and social and environmental conditions for health. The first three aspects were particularly important to the participants due to their historical background and the socio-economic status of the communities in which the schools were located. These aspects could be critical to their health and wellbeing. The first two aspects involved the physical and mental health of the participants. HPL was evident in the provision of resources for health promotion — i.e., ensuring that there were structures in place for the safety of teachers. The factors of school culture that are health-promoting may cultivate a healthy climate and build a common identity. Feeling unsafe can be stressful and distract teachers from their main task of ensuring effective teaching and learning. The participating schools were all located in townships where crime and unemployment rates are perceived to be high. Both above-mentioned measures, if effectively implemented, may contribute to a low sick rate. For HPL to be of value, physical and mental wellbeing should be prioritized.

The last two aspects were related to health awareness, compassion and care for teachers. Health awareness initiatives are regarded as rare but imperative in the workplace. Teachers were provided with the opportunity to communicate about health-related topics to gain more understanding of how to deal with health issues. They were also motivated to participate in health-promotion activities. It seems that school managers felt responsible for their subordinates’ health; however, the focus was only on staff care. Health awareness of leaders is as important as staff care, as it has implications for behavior change. A study by Grimm et al. (2021) found that the stronger a leader’s health-orientation toward self-care, the stronger their health-orientation toward their employees. The principal’s focus on self-development plays a crucial role in successful leadership (Steyn, 2014), and the same can be said for HPL. This study also suggests that critical conditions for HPL are contextual — school managers created a caring environment by supporting teachers in times of bereavement. Acts do not only show care and compassion but also that the leaders were genuinely interested in their subordinates’ wellbeing. Acts of care in times of bereavement revealed school managers’ caring attitude and “ubuntu,” which according to Gade (2012), is a philosophy of Black cultures that emphasizes valuing communal relationships with others. These two aspects are associated with fair and authentic leadership (Perko et al., 2016). Social support develops a positive organizational culture. Moreover, employees who perceive their leader as caring experience better health (Franke et al., 2014). Caring, as postulated by Noddings (2005), is not only what one does, but also how and why one does it. School managers visited the bereaved families of their colleagues, offered condolences and organized staff members to assist with funeral arrangements to support the bereaved colleagues. This gesture goes beyond feelings of concern and sentiment to actions to achieve particular aims, especially the betterment of others. Moreover, this seems to be a more relationship-oriented leadership style, which could be of significance for work-related health. The value of being supported in times of bereavement is that teachers do not carry the burden of arranging a funeral and the expenses alone. Being cared for can teach them to be caring toward others in similar situations.

Conclusion

HPL was perceived as relevant to enhancing healthy conditions in the work environment. However, the findings of this research should be understood in terms of the extent to which the elements of HPL were relevant to teachers in township schools. This article discussed the relevance of HPL to township schools as a contribution to organizational capacity building. HPL seems to be a promising path and a vital part of the township school capacity for health promotion. The research revealed the behaviors of school leaders when it came to organizing health-promotion activities that contributed to the development of a health-promoting workplace. Although the leadership role of the school leaders — which included setting agendas for health promotion and motivating school staff members to participate — was visible in the activities, a focus on self-care was lacking. The lesson that can be learned by the international community is that critical conditions that can contribute to the success of HPL in workplaces are context related. Moreover, the value attached to HPL depends on perceptions of the relevance of the activities that promote individual health and those that create healthy workplaces.

This study contributes to the understanding of HPL in education, particularly its relevance to township schools, as this issue has been poorly addressed in existing literature, especially in the field of education. It adds to undertakings that advance human resource practice by demonstrating a way to improve the wellbeing of teachers and enhance learner performance in township schools. The processes already embedded in the participating schools’ HPL initiatives may be possible vehicles to provide nationwide training in the importance of HPL in schools. The main limitation of this research was that the sample consisted of participants from only township schools. Further research can be conducted in other contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the EduREC North-West University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the contribution of the schools that participated in this research.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aitken, P. (2007). Walking the talk: the nature and role of leadership culture within organisation culture/s. J. Gen. Man. 32, 17–37. doi: 10.1177/030630700703200402

Akerjordet, K., Furunes, T., and Haver, A. (2018). Health-promoting leadership: an integrative review and future research agenda. J. Adv. Nurs. 74, 1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/jan.13567

Altonji, J. G., and Mansfield, R. (2011). “The role of family, school, and community characteristics in inequality in education and labor-market outcomes,” in Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. eds. G. Duncan and R. Murnane (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation), 339–358.

Bipath, K., Venketsamy, R., and Naidoo, L. (2019). Managing teacher absenteeism: lessons from independent primary schools in Gauteng, South Africa. S. A. J. Edu. 39, S1–S9. doi: 10.15700/saje.v39ns2a1808

Bogotch, I. (2011). “A history of public school leadership: the first century, 1837–1942” in The Sage Handbook of Educational Leadership. ed. W. Fenwich (New York: Sage Publications, Inc), 7–33.

Bregenzer, A., Felfe, J., Bergner, S., and Jiménez, P. (2019). How followers’ emotional stability and cultural value orientations moderate the impact of health-promoting leadership and abusive supervision on health-related resources. German J. Hum. Res. Man. 33, 307–336. doi: 10.1177/2397002218823300

Burton, P. (2008). Dealing With School Violence in South Africa. CJCP Issue Paper No. 4. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime.

Celsi, R. L., and Olson, J. C. (1988). The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 15, 210–224. doi: 10.1086/209158

Dadaczynski, K., and Paulus, P. (2015). “Healthy principals – healthy schools? A neglected perspective to school health promotion” in Schools for Health and Sustainability – Theory, Research and Practice. eds. V. Simovska and P. McNamara (New York: Springer), 253–273.

Daniel, D., and Strauss, E. (2010). Mostly I’m driven to tears, and feeling totally unappreciated: exploring the emotional wellness of high school teachers. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 9, 1385–1393. Available at: http://handle.net/10019.1/39551

Dellve, L., and Eriksson, A. (2017). Health-promoting managerial work: a theoretical framework for a leadership programme that supports knowledge and capability to craft sustainable work practices in daily practice and during organizational change. Societies 7, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/soc7020012

Department of Basic Education [DBE] (2018). National Senior Certificate: School Performance Report. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Dewing, J. (2007). Participatory research: a method for process consent for people who have dementia. Dementia Int. J. Soc Res. Pract. 6, 11–25. doi: 10.1177/1471301207075625

EAPA-SA (2005). Standards for Employee Assistance Programmes in South Africa. Johannesburg: EAPA-SA Board.

Eriksson, A. (2011). Health-promoting leadership: a study of the concept and critical conditions for implementation and evaluation. PhD thesis. Göteborg, Sweden: Nordic School of Public Health.

Eriksson, A., Axelsson, R., and Axelsson, S. (2010). Development of health promoting leadership – experiences of a training programme. Health Educ. 110, 109–124. doi: 10.1108/09654281011022441

Eriksson, A., Axelsson, R., and Axelsson, S. B. (2011). Health promoting leadership - different views of the concept. Work 40, 75–84. doi: 10.3233/wor-2011.1208

Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B., and Allen, S. D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: a guide to methods. London: Sage.

Fengu, S. (2017). South African teachers skip classes. News24 17 August 2017 Johannesburg. Available at: https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/sa-teachers-skip-classes-20170812 (Accessed March, 2021).

Franke, F., Felfe, J., and Pundt, A. (2014). The impact of health-oriented leadership on follower health: development and test of a new instrument measuring health-promoting leadership. German J. Resource Man. 28, 139–161. doi: 10.1177/239700221402800108

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 1–53. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Fu, B., Peng, J., and Wang, T. (2022). The health cost of organizational citizenship behavior: does health-promoting leadership matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:6343. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19106343

Gade, C. B. (2012). What is Ubuntu? Different Interpretations among South Africans of African Descent. South African Journ. of Philo. 31, 484–503. doi: 10.1080/02580136.2012.10751789

Govender, T., and Vandayar, R. (2018). EAP in South Africa: HIV/AIDS pandemic drives development. J. Empl. Assist. 48, 12–21. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/8392

Grimm, L. A., Bauer, G. F., and Jenny, G. J. (2021). Is the health-awareness of leaders related to the working conditions, engagement, and exhaustion in their teams? A multi-level mediation study. BMC Pub. Health 21, 1–11. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-368807/v1

Gurt, J., Schwennen, C., and Elke, G. (2011). Health-specific leadership: is there an association between leader consideration for the health of employees and their strain and well-being? Work Stress 25, 108–127. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2011.595947

Horstmann, D., and Eckerth, H. L. (2016). “The need for healthy leadership in the health care sector: consideration of specific conditions for implementation” in Healthy at Work. eds. M. Wiencke, M. Cacace, and S. Fischer (Cham: Springer)

Jacelon, C., and Imperio, K. (2005). Participant diaries as a source of data in research with older adults. Qual. Health Res. 15, 991–996. doi: 10.1177/1049732305278603

Jiménez, P., Bregenzer, A., Kallus, K. W., Fruhwirth, B., and Wagner-Hartl, V. (2017). Enhancing resources at the workplace with health-promoting leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:1264. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101264

Keller, J. M. (1987). Development and use of the ARCS model of motivational design. J. Instruc. Dev. 10, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02905780

Kent, K., Goetzel, R. Z., Roemer, E. C., Prasad, A., and Freundlich, N. (2016). Promoting healthy workplaces by building cultures of health and applying strategic communications. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 58, 114–122. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48500803

Krammer, M., Rossmann, P., Gastager, A., and Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (2018). Ways of composing teaching teams and their impact on teachers’ perceptions about collaboration. Eur. J. Teach. Edu. 41, 463–478. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2018.1462331

Lancaster, I. (2012). Modalities of mobility: Johannesburg learners’ daily negotiation of the uneven terrain of the City. S. A. Rev. Edu. 17, 49–63. Available at: https.//hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC99009

Leoschut, L. (2006). Double trouble: youth from violent families: easy victims of crime? S. A. Crime Quart. 16, 7–11. doi: 10.17159/2413-3108/2006/i16a998

Li, J., Ye, H., Tang, Y., Zhou, Z., and Hu, X. (2018). What are the effects of self-regulation phases and strategies for Chinese students? A meta-analysis of two decades research of the association between self-regulation and academic performance. Front. Psych. 9:2434. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02434

Mampane, P. M. (2012). The teacher turnover crisis, evidence from South Africa. Bus. Educ. Accred. 4, 73–83. Available at: https://ssm.com/abstract=2144991

Mampane, R., and Bouwer, C. (2011). The influence of township schools on the resilience of their learners. S. A. J. Educ. 31, 114–126. doi: 10.15700/saje.v31n1a408

Mandel, K., and Elserman, T. (2016). Team teaching in high school. Educ. Lead. 73, 74–77. Available at: https://search-ebscohost-com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=111519013

Milner, K., and Khoza, H. (2008). A comparison of teachers’ stress and school climate across schools. S. A. Journ. Educ. 28, 155–173. doi: 10.15700/saje.v28n2a38

Monyooe, L. (2017). Reclassifying township schools - South Africa’s educational tinkering expedition! Create. Edu. 8, 471–485.

Noddings, N. (2005). Caring in Education', the Encyclopedia of Informal Education. Available at www.infed.org/biblio/noddings_caring_in_education.htm.

Perko, L., Kinnunen, U., Tolvanen, A., and Feldt, T. (2016). Back to basics: the relevant importance of transformational and fair leadership for employee work engagement and exhaustion. Scandinavian J. Work Org. Psych. 1, 6–13. doi: 10.16993/sjwop.8

Rowling, L., and Samdal, O. (2011). Filling the black box of implementation for health-promoting schools. Health Edu. 111, 347–366. doi: 10.1108/09654281111161202

Samdal, O., and Rowling, L. (2011). Theoretical and empirical base for implementation components of health-promoting schools. Health Educ. 111, 367–390. doi: 10.1108/09654281111161211

Shields, N., Nadasen, K., and Hanneke, C. (2015). Teacher responses to school violence in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Appl. Soc. Sciety 9, 47–64. doi: 10.1177/1836724414528181

Skarholt, K., Blix, E. H., and Sandsund, M. (2016). Health promoting leadership practices in four Norwegian industries. Health Promot. Int. 31, 936–945. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav077

Skott, P. (2022). Successful health-promoting leadership – a question of synchronization. Health Educ. 122, 286–303. doi: 10.1108/HE-09-2020-0079

South Africa (1999). Employee Assistance Programs Association (EAPA). Standard for Employee Assistance Programme in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Steyn, G. M. (2014). Exploring successful principalship in south africa: a case study. Journal of Asian and African Studies 49, 347–361. doi: 10.1177/0021909613486621

Taute, F., and Manzini, K. (2009). Factors that hinder the utilisation of the employee assistance programme in the Department of Labour. Soc. Work 45, 385–393. doi: 10.15270/45-4-190

The New Age (2017). Teachers Overworked. Johannesburg: The New Age. Available at: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/hsrc-in-the-news/general/teachers-overworked

Van Manen, M. (2013). Phenomenology of practice. Available at: https://scholar.google.co.za/scholar?q=Van+Manen+M+2014.+Phenomenology+of+practice.&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart

Velasco, V., Coppola, L., and Veneruso, M. (2022). COVID-19 and the health promoting school in Italy: perspectives of educational leaders. Health Educ. J. 81, 69–84. doi: 10.29173/pandpr19803

Wessels, E., and Wood, L. (2019). Fostering teachers’ experiences of well-being: a participatory action learning and action research approach. S. A. J. Edu. 39:1. doi: 10.15700/saje.v39n1a1619

Whitehead, D. (2006). The health-promoting school: what role for nursing? J. Clinic. Nurs. 15, 264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01294.x

Winkler, E., Busch, C., Clasen, J., and Vowinkel, J. (2015). Changes in leadership behaviors predict changes in job satisfaction and well-being in low-skilled workers: a longitudinal investigation. J. Lead. Organ. Stud. 22, 72–87. doi: 10.1177/1548051814527771

Xaba, M. (2006). An investigation into the basic safety and security status of schools’ physical environments. S. A. J. Educ. 26, 565–580. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10520EJC32099

Yao, L., Li, P., and Wildy, H. (2021). Health-promoting leadership: concept, measurement, and research framework. Front. Psychol. 12:602333. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.602333

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in Organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Available at: https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Yukl-Leadership-in-Organizations-8th-Edition/PGM151705.html

Zimmerman, D., and Weider, D. L. (1977). Diary-interview method. Urban Life 5, 479–498. doi: 10.1177/089124167700500406

Žižek, S. S., Mulej, M., and Čančer, V. (2017). Health-Promoting Leadership Culture and its Role in Workplace Health Promotion. doi: 10.5772/65672

Zoch, A. (2017). The Effect of Neighbourhoods and School Quality on Education and Labour Market Outcomes in South Africa. Available at www.ekon.sun.ac.za/wpapers/2017/wp082017

Keywords: health-promoting leadership, health-promoting leadership in education, relevance of health-promoting leadership, township schools, effective schools

Citation: Kwatubana S (2022) Health-promoting leadership in education: Relevance to teachers in township schools. Front. Educ. 7:780737. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.780737

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Rakotoarisoa Maminirina Fenitra, Airlangga University, IndonesiaJill Sperandio, Lehigh University, United States

Pontso Moorosi, University of Warwick, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Kwatubana. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Siphokazi Kwatubana, c2lwaG8ua3dhdHViYW5hQG53dS5hYy56YQ==

Siphokazi Kwatubana

Siphokazi Kwatubana