Remote Education/Homeschooling During the COVID-19 Pandemic, School Attendance Problems, and School Return–Teachers’ Experiences and Reflections

- 1Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioural Research in Education, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Child Welfare, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

According to Norway’s Educational Act (§2-1), all children and youths from age 6 to 16 have a right and an obligation to attend free and inclusive education, and most of them attend public schools. Attending school is important for students’ social and academic development and learning; however, some children do not attend school caused by a myriad of possible reasons. Interventions for students with school attendance problems (SAPs) must be individually adopted for each student based on a careful assessment of the difficulties and strengths of individuals and in the student’s environment. Homeschooling might be one intervention for students with SAPs; however, researchers and stakeholders do not agree that this is an optimal intervention. Schools that were closed from the middle of March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to investigate remote education more closely. An explorative study was conducted that analyzed 248 teachers’ in-depth perspectives on how to use and integrate experiences from the period of remote education for students with SAPs when schools reopen. Moreover, teachers’ perspectives on whether school return would be harder or easier for SAP students following remote education were investigated. The teachers’ experiences might be useful when planning school return for students who have been absent for prolonged periods.

Introduction

School attendance problems (SAPs) are a concern in many countries because attending school is important for students’ academic, emotional, and social learning (e.g., Kearney, 2008). Home education or homeschooling is an intervention for some students who have been absent for a prolonged period, as a part of a gradual return that connects the student to school and to schoolwork at home. However, this is a controversial topic in the literature (Kearney, 2016). Some researchers (e.g., McShane et al., 2004; Melvin and Tonge, 2012) claim that students should not do schoolwork at home because it is believed to prolong absence. Others (e.g., Kearney, 2016) argue that doing schoolwork at home might reduce the anxiety of falling behind academically and ultimately make school return easier. When schools in many countries closed in the middle of March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers had to immediately provide education at home to teach their students using various digital solutions, tools, and skills. The concept “emergency remote education” clearly separate the practice during the period of closed schools from planned practices such as distance education, e-learning, online education, homeschooling, or other concepts being used in different countries, and (Bozkurt et al., 2020).1 No national guidelines existed in Norway about how to do remote education; however, the curriculum and the Education Act were still applicable. The main aim of this study was to investigate teachers’ perspectives on how to integrate their experiences of remote education during the pandemic for students with SAPs when schools reopen and to investigate their perceptions of how the experiences from remote education could impact school return.

School Attendance Problems

Attending school is important for students’ behavioral, social, economic, and educational learning (e.g., Kearney, 2008; Ansari et al., 2020), in addition to the fact that in Norway, education is a right and an obligation from age 6 to 16 (grade level 1–10). However, SAPs are a concern in many countries, and research in this area is increasing. SAPs are usually seen as unauthorized absences, which are absences not recorded as illnesses or with permission from the school (Dalziel and Henthorne, 2005). Many types of SAPs exist, such as truancy, school refusal, school withdrawal, and school exclusion (e.g., Heyne et al., 2019). In this study, all types of unauthorized/undocumented SAPs are included based on criteria adapted from Kearney (2008). The reasons for SAPs are multiple and often complex (Egger et al., 2003; Heyne et al., 2011; Ingul and Nordahl, 2013; Havik et al., 2014, 2015; Blöte et al., 2015).

Thambirajah et al. (2008) proposed a vicious cycle to describe how absence might be maintained for students with anxiety-based school refusal. This cycle visualizes how an absent student might lose opportunities to improve peer relationships and social functioning and therefore experience social isolation. These students may also fall behind in schoolwork, making school return difficult because they fear school failure. Together, these factors might increase students’ levels of anxiety as anxiety-provoking situations at school are avoided. Although this circle mainly explains anxiety-based school refusal, it is also relevant to understand other types of SAPs.

Traditional Homeschooling

According to the Educational Act in Norway, parents can decide to provide education at home for their children. They might do this for several reasons, such as long-term illness, concern about and dissatisfaction with the educational system, school environment, or available academic instruction, failure to meet their child’s needs, inadequate responses to bullying or well-being, and the provision of religious or moral instruction (e.g., Medlin, 2000; NCES, 2009; Mitchell, 2021). Moreover, some parents of SAP students might fear harmful situations in school or be critical of the school, teacher, or education (e.g., Kearney, 2008; Thambirajah et al., 2008) and want their child to be educated at home. In traditional homeschooling, parents administer the education and the educational goals. The quality should be the same as in public education as explained in the Educational Act, and municipalities are required to evaluate the education provided.

Home education or homeschooling is controversial in general and for students with SAPs (Kearney, 2016). One concern is the lack of socialization (Romanowski, 2006; Ray, 2013) and some researchers are critical of homeschooling movements and fear that it might lead to social isolation from other children (e.g., Mayberry et al., 1995; Lubienski, 2000; Monk, 2004). However, previous research indicates that parents are aware of the importance of children’s socialization when they are homeschooled, and they often encourage socialization for their children (e.g., Nelson, 2014; Neuman and Guterman, 2017; Fensham-Smith, 2021). A study by de Carvalho and Skipper (2019) provides insight into the social lives of three United Kingdom home-educated adolescent girls and their mothers. The findings indicate that the parents encouraged their children to socialize by organizing social activities and groups. Home educating networks had an important role in bringing families together and serving as a supportive network for parents and children that offered a variety of social interactions, and these adolescents participated in a range of social experiences (de Carvalho and Skipper, 2019). Therefore, there is no agreement on how homeschooling affects socialization, and more research is needed. In addition, this issue is part of a larger discussion because some students find socialization in school to be problematic (Mitchell, 2021).

Homeschooling and School Attendance Problems

Homeschooling might be an intervention in addition to partial school attendance for SAP students to prepare for gradual school return (e.g., Carroll, 1996; Thambirajah et al., 2008). However, when students with SAPs do schoolwork at home, they might believe this could be a lasting solution, leading to a vicious cycle that is difficult to break (Thambirajah et al., 2008; Wijetunge and Lakmini, 2011). When students’ complete schoolwork at home, they might not experience anxiety or worries related to school and might have better general well-being. In this way, homeschooling might be a good intervention to fill academic gaps and reduce students’ anxiety caused by school situations, which might make school return easier. However, findings from a recent study indicate that some students do not do schoolwork during emergency remote education, and 20% do not participate at all (Havik and Ingul, 2021a). This indicates that school at home during the pandemic may not fill academic gaps for all SAP students. These students fall behind academically, which potentially increases their anxiety about school return. School at home is therefore not a good solution for all SAP students (Havik and Ingul, 2021a).

Moreover, when students have school at home, SAP students might miss social experiences with peers and teachers, which is a concern about home education in general (e.g., Ray, 2013). For students who experience negative interactions in school, such as bullying (e.g., Havik et al., 2014, 2015), doing schoolwork at home might be liberating; but in the long-term school return might be even harder because they are socially isolated.

Some studies recommend homeschooling for students with school refusal who dislike and avoid school (Stroobant and Jones, 2006; Stroobant, 2008), arguing that students and their families might be in a stressful situation and that stressors are reduced when the student stays at home. Furthermore, this situation may lead to less unrest and disturbance at home, making everyday life easier for the whole family. However, others do not recommend homeschooling because it might promote avoidance (Melvin and Tonge, 2012). Moreover, homeschooling might increase students’ anxiety and thereby maintain avoidance (e.g., Thambirajah et al., 2008; Ek and Eriksson, 2013; Heyne and Sauter, 2013).

Developmental processes might slow or stop during homeschooling, even if it leads to sufficient academic learning. A study of parents of students with school refusal in the United Kingdom found that most of them wanted to continue home education because their children thrived academically and socially (Wray and Thomas, 2013). Findings from this study indicated that symptoms associated with school refusal mostly disappeared or were reduced during home education, which is in line with findings indicating that home education “virtually eliminates any mental illness” (Knox, 1989, p. 150) and that symptoms “either disappear completely with no aftereffects or decline considerably” (Fortune-Wood, 2007, p. 137). Wray and Thomas (2013) concluded that home education should be an alternative to school return from the parental perspective. However, although symptoms of mental illness disappear or decrease when stressors are removed, they may increase when stressors such as school return are reintroduced.

Remote Education During the Pandemic

Remote education for all students during a pandemic is different than traditional homeschooling for a few students. During the pandemic, digital/distance lessons were provided without any national guidelines to inform practice. Teachers were asked to immediately provide all teaching from home. Teachers used a variety of digital tools, and the majority gave live lessons daily by video communication (Fjørtoft, 2020).

Remote education may be provided differently between schools and teachers and Norwegian teachers reported using “trial and error” and guidance from colleagues/advisors at school as their main resource to increase competence in their digital practice during the pandemic (Fjørtoft, 2020). Fjørtoft’s study indicates that teachers believed they had mastered digital teaching without any major challenges, but some felt that digital teaching/tools required more preparation and better classroom management. Moreover, a key finding from a national survey of parents was that remote education during the pandemic largely consisted of students doing individual tasks with limited support from teachers (Blikstad-Balas et al., 2022).

In a study from the United States, most parents (64%) were concerned that their children had fallen behind academically due to school closure during the pandemic (Horowitz, 2020). Another United States study indicated that students may have fallen substantially behind academically, especially in mathematics, and that students were likely to enter school with greater variability in academic skills than during normal circumstances (Kuhfeld et al., 2020). In the Netherlands, where schools were closed for only 8 weeks, school closure was associated with academic learning losses (Engzell et al., 2020).

School Return

According to most researchers, early identification and interventions for SAPs are of great importance (e.g., Kearney and Graczyk, 2014; Keppens et al., 2019). Research indicates that every day of attendance counts and contributes to students’ learning and that academic outcomes are enhanced by maximizing attendance in school without a “safe” threshold (e.g., Hancock et al., 2013). Moreover, Simon et al. (2020) found that individual students tend to stabilize their rates of absence after third grade and noted the importance of early interventions in a student’s school career.

When students have been absent from school, a gradual return as quickly as reasonably possible is often recommended because it increases the likelihood of successful outcomes (e.g., Elliott and Place, 2012; Kearney and Graczyk, 2014). A gradual return and introduction to school for anxiety-based school refusal is included in most cognitive behavior therapy-based manuals (Blagg and Yule, 1984; King et al., 2000; Heyne et al., 2015). In a study from Japan, a rapid return approach was effective for adolescents with school refusal who were unwilling to attend individual therapy (Maeda and Heyne, 2019).

However, after the pandemic, all students need to be reintegrated and reengaged in school, and gradual school return is important for SAP students. Reengagement is one important aspect of the Alternative Educational Program in the Netherlands (Link) for school refusers (Brouwer-Borghuis et al., 2019). Teachers in Link help students prepare for reintegration to school, which includes gradually facing school-related fears and working together on steps in a fear hierarchy. Some of these activities might be helpful for some SAP students when gradually reengaging and returning to school after the pandemic. Examples are “to participate in a game, ask question in class, take a test, observe cooking lessons, and sit in on group discussions, and then gradually increase the amount and type of participation in such activities” (Brouwer-Borghuis et al., 2019, p. 81).

Cooperation

Cooperation within a team with students, staff in school, parents, peers, and health personnel is strongly encouraged for SAPs (Brand and O’Conner, 2004; Nuttall and Woods, 2013; Kearney and Graczyk, 2014; Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Brouwer-Borghuis et al., 2019). Findings from an in-depth interview study examining the current systems of collaboration between schools, children, and mental health services indicated deep-seated barriers to good collaboration (Rothi and Leavey, 2006). These teachers experienced frustration because they were excluded from mental health care management even though they were affected professionally by the decisions that were made there; moreover, they experienced delays in intervention and poor communication (Rothi and Leavey, 2006). Nuttall and Woods (2013) interviewed youths, parents, school staff, and other professionals and noted the importance of close collaboration with the professionals involved. In a qualitative study with parents of children with school refusal, the parents emphasized a need for a coordinated team approach (Havik et al., 2014). Moreover, parental support and involvement, positive school–parent relationships, and good communication are essential for good interventions for attendance problems (Havik et al., 2014; Kearney and Graczyk, 2014; Finning et al., 2018). From teachers’ perspectives cooperation between school and home is more important during remote education than regular schooling because structure and help at home vary greatly and is important for how students handle to do schoolwork at home (Havik and Ingul, 2021a).

Tailored Interventions and a Safe Learning Environment

In an ideal world, schools should be a place where all students feel safe, are engaged, and connected, and interact positively with teachers and peers. SAPs are a diverse issue for individual reasons, meaning that “one size doesn’t fit all” (e.g., Kearney and Graczyk, 2014, 2020; Finning et al., 2018; Heyne, 2019). The similarity is that students do not attend school, but their reasons for not attending school are diverse. Therefore, interventions must be adapted and tailored for each student based on an assessment of the student’s parent/family, peers, school, and community regarding the difficulties and strengths (Kearney, 2008; Ingul et al., 2019).

Students need a safe learning environment with good relations and support from teachers and peers as well as structure, routines, and quiet surroundings during the school day to help them feel that the school day is predictable, which is important for SAP students (Nuttall and Woods, 2013; Havik et al., 2014). They also need support in their learning process, to be connected to learning and schoolwork and to be engaged. Nuttall and Woods (2013) claim that these students need an individualized approach, and that schoolwork should be linked to personal interests for them to be able to achieve their educational goals.

The Present Study

The main aim of this study was to investigate teachers’ experiences of remote education during the pandemic for SAP students and how these experiences could be used when schools reopen. We also wanted to investigate whether teachers believe that school return will be harder or easier following remote education at home. The research questions were as follows. RQ1: How can experiences from remote education be used and integrated when schools reopen? RQ2: Do teachers think that school return will be harder or easier for SAP students following remote education during the pandemic?

Materials and Methods

Participants

The final sample for this study consisted of 248 teachers from all municipalities in Norway; 75% of the sample were female teachers, reflecting gender in primary and lower secondary schools in Norway (SBSS, 2019). The sample consisted of teachers from all 11 counties of Norway, varying between 8 and 45 teachers in each county. We had no other information about the teachers than gender, county they work, and whether they were the main or subject teacher for the SAP student. Thus, we cannot claim that the sample is random, or generalize and draw conclusions for all teachers in Norway. For more information about the sample, see Havik and Ingul (2021a).

Design

Because this was an explorative study, most of the questions were open-ended, and teachers were asked to write their answers briefly and concisely in their own words. When answering the survey, we asked the teachers to choose and think about one student with SAPs in their class based on adapted criteria from Kearney (2008): (1) absent from school more than 2 days in the last 2 weeks before schools closed with no documented absence and/or (2) more than 15% undocumented absences since Christmas (10 weeks).

Procedure

All schools in Norway received an e-mail about the study on 24th April 2020. They were asked to distribute the e-mail to the teachers in their school who had students with SAPs in grade levels 5–10 because these grade levels still had remote education. We asked the teachers to answer a web-based questionnaire within 2 weeks.

The questionnaire did not link the teachers’ answers to their computers’ IP addresses, in line with requirements for anonymity from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. This research project was not subject to notification since no sensitive personal data were collected. The participants gave their consent to participate by answering the questionnaire. They were given instructions in the e-mail, which also contained information about the aim of the study and stated that participation was voluntary. Those who chose to participate completed a questionnaire with three topics: the first part included general questions concerning all students and remote education a, the second part was related to one student with SAPs in the teacher’s class, and the third part was about other students with SAPs in the teacher’s class. The current study used qualitative data from the second part and included the following questions: (1) How can you use experiences with remote education when schools reopen? (2) Describe whether the situation with remote education will make it easier or more difficult for SAP students to return to school. Because the questions were open-ended, the teachers wrote their own answers. Some wrote in-depth answers (up to 130 words), while others wrote only short answers.

Analyzing Qualitative Data

In this study a deductive approach was used, reading relevant theory related to the research questions, and testing its implications with the collected data. Deductive thematic analysis was chosen because it facilitates the interpretation of identifiable themes and patterns of teachers’ perspectives and experiences. A “theoretical” or deductive thematic analysis is more driven by the researcher’s theoretical interest and a detailed analysis of some aspect of the data, which affects how we coded the data, where we coded for specific research questions (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019). The data were analyzed using deductive thematic analysis, which is flexible, offers an accessible way to analyze qualitative data (Aronson, 1995; Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019; Lambert and O’Halloran, 2008) and is well suited when generating (initial) themes or patterns of shared meaning in the data. The analysis is more descriptive than interpretive, inspired by Moustakas’ (1994) transcendental or psychological phenomenology. Six steps are suggested to be followed (Braun and Clarke, 2006): (1) familiarizing with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report/article. The data, which comprised the teachers’ in-depth answers, were carefully discussed, analyzed, and categorized by both researchers.

The process of analyzes involved several stages based on guidelines from different sources (Aronson, 1995; Braun and Clarke, 2006). First the data was read several times and organized in two documents, one for each research questions. The initial thoughts were noted in a separate column in each document, related to the concepts we considered interesting or significant for the research questions. Then the data set was re-read several times and the initial notes were transformed into specific subthemes, representing the meaning within the data set. Third, main themes were identified consisting of a varying number of identified subthemes. The frequency of occurrence of each theme and subtheme was recorded to establish the strength of each theme (mentioned in the tables). Some of the illustrations from the raw data were extracted to provide evidence of each theme and subtheme. Then the final analysis was related back to the research questions and the previous literature, before writing out the results.

Results

The main aim of the current study was to explore teachers’ perspectives based on an approximately 2-month period of remote education for SAP students. The results are presented based on the research questions: RQ1: How can experiences from remote education be used and integrated when schools reopen? and RQ2: Did the teachers think school return would be harder or easier for SAP students following remote education during the pandemic?

Use of the Experiences From Remote Education When Schools Reopen

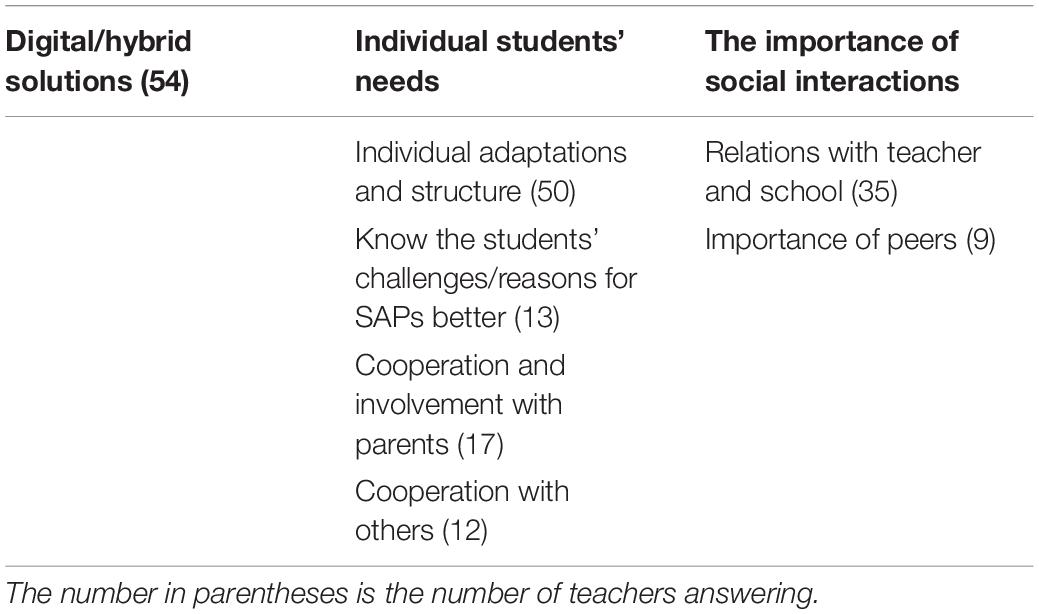

Most of the teachers in this study were concerned with the importance of SAP students attending or partly attending school immediately when schools reopened to motivate and plan for re-entry in close cooperation with the student and home/other services. This topic was incorporated into many of the other themes that emerged from the analyses. Other main themes that emerged from the data were as follows (Table 1 gives an overview of the themes).

Digital/Hybrid Solutions

Digital/hybrid solutions were mentioned by many of the teachers. These comments were about the importance of continuing to use digital solutions/lessons in addition to partial school attendance. Moreover, the teachers and students had learned more about digital solutions and had increased their digital skills to do schoolwork at home. Many of the teachers believed that these experiences could be used when schools reopened, such as using digital lessons when students did not attend school for lessons/days or as part of the adapted plan for the students. Some teachers expressed a need for a more flexible school and the integration of school at home as part of the SAP students’ plans and gradual reintegration. They believed this might reduce stress and engage the SAP student more, which would encourage the student to participate more. The quotations below illustrate this.

“Continue to teach digitally and incorporate and organize this in line with measures to achieve the goal to return to school.”

“These experiences show the possibility to set up assignments for the student to work from home if the student does not manage to attend school.”

“The expertise in the use of digital tools is useful for us teachers because we use the students’ preferred learning channel. They are used to gaining knowledge and orienting themselves on YouTube. When we share subjects in the same arena, the students’ motivation increases.”

“We may need to consider greater flexibility in everyday school life. It is perhaps enough for many students who struggle in different arenas, academically or socially, and that they can sometimes choose homeschooling. We do not have to push everyone into the same shape. The school must be more flexible.”

Individual Adaptations and Structure

Many teachers expressed a need for individual adaptation and better follow-up for these adaptations. Some of the examples expressed by the teachers were working with tasks in which the students’ experienced mastery and for which they were motivated and interested, lowering and setting more realistic requirements, and providing sufficient time and help. Another example was the importance of structuring their school day, lessons, and tasks with concrete working plans and the need for a safe and quiet learning environment. Some of the quotations illustrating these examples of tailored adaptations and structure are as follows:

“Use the feeling of mastery and joy she has felt during this period to motivate her to continue. Make the student aware that this is only for a shorter period until the schools reopen. Set specific goals with the student and do not skip routines.”

“Adapt as much as possible related to the student’s interests. Offer help and support at the same time as helping the student to stay motivated (.)… I also think it is important to lower the requirements, as it is more important that something is done, and there is a need for close guidance.”

“It is extremely important to maintain a solid structure in all areas where it is possible….”

In relation to individual adaptations/plans, a few teachers wrote that during remote education they learned more about the student, including the student’s challenges, reasons, and strengths and who was involved in the student’s schoolwork at home.

“We now see more clearly what the reason is for school refusal.”

“We know more about what the student likes academically, and which lessons the student is most engaged in.”

Some teachers commented on the importance and need for closer cooperation with others for examination and assessment of the student and treatment/help.

“It is clearer that the student is struggling with self-confidence and partial anxiety about something, so when we return to school, I will contact the health nurse (the parents have given permission for this).”

“We need to collaborate even more with other services to get the student to school.”

The need for close home–school cooperation and parental involvement was expressed by some teachers. Some of them experienced closer cooperation with the parents, and parents were more involved during remote education than before, while others experienced the opposite, including difficulties in cooperation and lack of involvement by parents. Moreover, some commented that they now knew more about how much or how little parents followed up and cared for their child’s schooling.

“The home is now more included in the schoolwork and has better conditions to follow up….”

“We need a much closer dialog with the home.”

“We had good dialog with the home, both before and during the COVID-19 situation, and we expect this will continue afterward as well. However, it did not help because absenteeism is increasing for this student.”

Relations With Teacher, School, and Peers

Many teachers experienced the importance of working more closely with the student, who needed to be seen more and required more help during the period of remote education. They also expressed the importance of a close relationship between the teacher and the student, such as having good dialog, smiling at the student, and being patient and caring. Moreover, a few teachers expressed the importance of meeting peers and friends for social interactions in school. Some quotations illustrating the importance of relations are as follows:

“…We have achieved a good relationship during this period, and therefore it might be easier for her to attend school.”

“The experiences with this student have shown us that it is necessary to have close follow-up/monitoring during regular school and homeschooling.”

“It is good for her to come back to school where she gets closer follow-up/monitoring by the teacher when the going gets tough.”

“The importance of relations via physical attendance is more obvious for me.”

“The student might get more motivation to attend school when meeting friends.”

“During the first days at school, it becomes important to work with the social part in the class again. This is probably what the students need most when they return, especially for this girl.”

Finally, some teachers did not answer the question about the use of their experiences, a few teachers wrote that there would be no change or that they would keep working as they did before, and two of the teachers commented that school at home did not work or was not useful for the SAP student. Moreover, many teachers did not know or were insecure about how to use their experiences when schools reopened. A few of them wrote that they did not yet know how to do this:

“Feels totally helpless for me as the subject teacher, but I trust that the system around does what is needed to be done, and I know they do.”

Returning to School–Easier or More Difficult

We also investigated whether teachers believed that the situation with remote education would make it easier or more difficult for SAP students to return when schools reopened. Some of the teachers described their experiences and meanings in detail, while others gave shorter descriptions. Some teachers did not answer, a few teachers believed there would be no difference, and many teachers wrote that they were uncertain or did not know without explaining why. Moreover, many teachers commented that school return could be both more difficult and easier depending on individual students’ reasons for SAPs:

“For students who worry about attending school, it will be harder to return to school. At the same time, all students have experienced the same (homeschooling), and they can meet with a ‘clean slate’ and academically they get a new start, in a way.”

“I think this will vary. Some students with high absenteeism and who have worked well at home may fall into the same pattern as before since physical attendance is a challenge, not an academic challenge. When you have been at home and this is safe, the threshold for returning can be even greater, especially with school refusers. If the student is absent due to lack of motivation, it may be easier to return to school, especially if they miss their peers.”

“This will probably vary based on the reasons for SAPs. I think for many students, it is good to return to more normality. However, they can also feel this transition is hard because they have to meet physically at school.”

“Both. The student probably misses the social part of school; at the same time, the students’ well-being is better at home.”

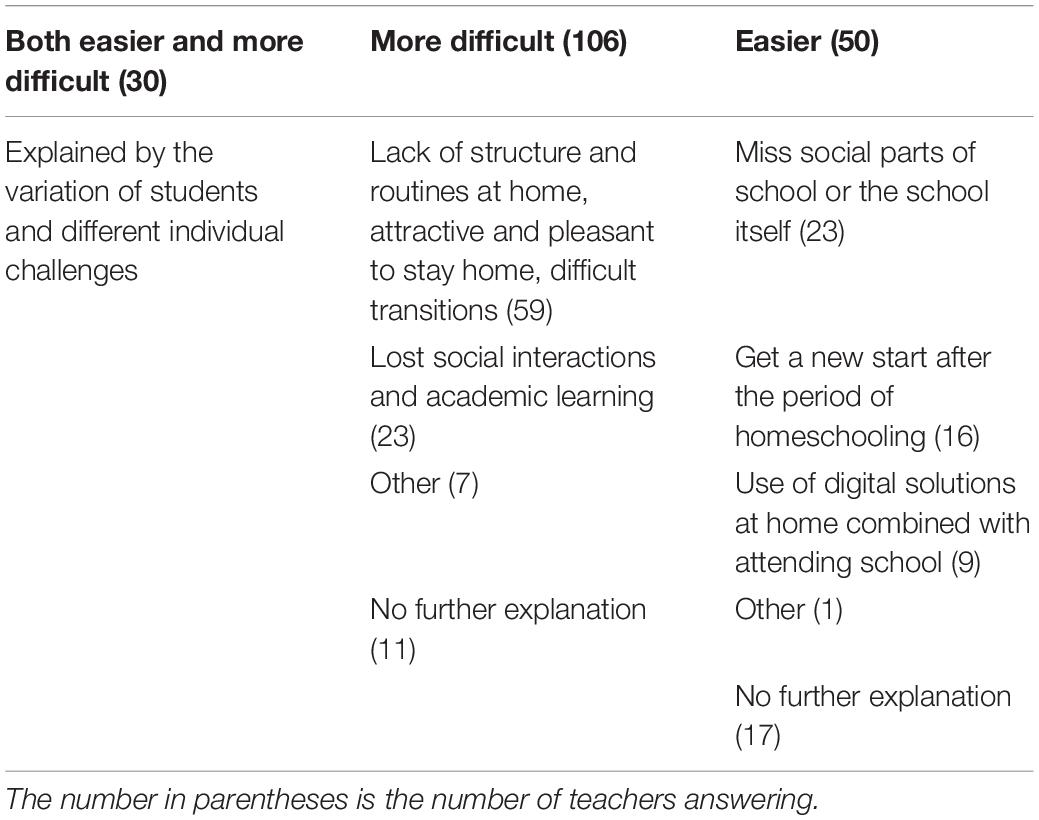

Most of the teachers wrote that school return could be either easier or more difficult for the student: half as many teachers stated that return would be easier, than those who thought it would be more difficult (Table 2 gives an overview of the themes).

Easier to Return

Three main themes emerged from the data: (a) missing the social part of school (like to be with peers at school); (b) getting a new start and more structure for their school day; and (c) the use of digital platforms (based on positive experiences during homeschooling, digital solutions could be used in addition to attending school). Some quotations are as follows:

“For the student I described, it will be easier to attend school. She expresses that she misses school, schoolwork, and her peers.”

“What might make it easier is that peers do not know what she has been involved in and not and thus have a more ‘clean slate’ when school opens.”

“I think during homeschooling we realize that it is possible to maintain a certain contact with the student via digital channels, also academically when schools reopen. During almost the entire school year, the school has not been able to maintain an academic education for the student because she has not attended school.”

Some teachers did not comment more than “it will be easier for the student,” and one teacher commented about less physical discomfort that might make return easier.

More Difficult to Return

Most of the teachers believed that school return would be more difficult when schools reopened. Some teachers did not state why, but most of them explained this in their own words, and two main themes emerged from the data. The first theme was routines and transition (lack of routines and structure at home, students finding it pleasant and attractive to stay at home, difficult to transition after school breaks, and a wish to still have homeschooling).

“It will probably be harder. The student is on a negative track. To get back to their normal routines might be challenging.”

“I think it will be harder. The student has slipped into a life where night has become day. Social media and playing games control most of the hours she is awake.”

The second theme was social and/or academic barriers; the students lost academic learning and/or social interactions during the period of remote education.

“Acclimatization socially and academically. It is negative to start with many academic holes, negative self-image.”

“I think it might be more difficult for this group of students to rebuild social relationships.”

In addition, a few teachers’ comments were more general and related to difficulties of school return. For example, there may be greater difficulty for students with anxiety and school refusal, a gradual return when schools reopened, and two school “breaks” (caused by the pandemic and the summer vacation) that made a gradual return harder. One of the teachers said:

“Worse for the students with school refusal. Now we know they can have school at home as well; thus, the student might think; why it is necessary to be at school?”

Summary of the Results

Most of the teachers reported experiences they wanted to use when schools reopened for SAP students. The most frequently mentioned experiences were as follows:

1. Use more digital/hybrid solutions (partly attending school and partly attending digitally), especially on days the student is not attending school. This is related to the teachers’ and students’ increased confidence in using digital tools in schoolwork, which provide a better opportunity for more flexible solutions.

2. Increasing individual tailored adaptations based on the students’ challenges, strengths, and interests. The need for structure and routines was indicated as important. Moreover, parents should be involved, and good cooperation should be established between the home and school and with other services. This topic is related to teachers who learned more about their students during the remote education period and were now more aware of the specifics of the students’ problems.

3. Focusing on relations between teachers and students and between students, for instance, following up or monitoring the student more closely, providing extra time/attention, and including them in the school community, which the teachers were in a better position to do when the SAP students returned to school.

Most of the teachers believed that school return would be harder for SAP students, mainly because return is difficult after a “break,” there is a lack of structure/routines during the period of remote education, and students fell behind socially and academically in this period. However, other teachers (half as many as those who believed that return would be harder) believed that school return might be easier because the students missed their peers and school, there was a possibility for a new start, and they knew how to use digital/hybrid solutions when the schools reopened.

Discussion

Teachers were asked how to use their experiences from remote education for SAP students during the pandemic when the schools reopened and whether they believed that school return would be harder or easier for the students. The answers indicated variety in the teachers’ experiences.

Digital/Hybrid Solutions When Schools Reopen

One of the most frequently mentioned themes was teachers’ greater possibility of using digital/hybrid solutions (i.e., having students partly attend school in person and partly attend digitally), particularly on days the SAP student could not attend school or was not attending for planned reasons. Because digital lessons had to be given from the first day that the schools closed with no national guidelines, variation in teachers’ and students’ digital skills, practices, and digital learning was expected, which led to a “trial and error” approach (Fjørtoft, 2020). A study of Norwegian teachers found that they mastered digital teaching without any major challenges, but the quality, content, and length of the lessons were unknown (Fjørtoft, 2020). This finding is in line with the current study, which found that the teachers wanted to use more digital or hybrid solutions for SAP students when schools reopened, which might be related to teachers gaining competence and being more confident in digital teaching. Moreover, the findings indicated that digital lessons are a good intervention for SAP students’ academic learning, especially on days the students do not attend school. Some teachers recognized the need for more flexible solutions for SAP students, which might be easier to accommodate after the experiences during the pandemic.

Tailored Interventions When Schools Reopen

The teachers also frequently mentioned the need for individual tailored adaptations based on the students’ challenges, strengths, and interests. This is related to previous research; one intervention does not fit all SAP students (e.g., Kearney and Graczyk, 2014; Finning et al., 2018). Some of the teachers stated that they learned more about their SAP students’ challenges and reasons for SAPs during this period. This indicates that teachers need to have enough individual time with SAP students to know them better. This might also influence the relations between teachers and students, which is important for the prospect of school return. It is important to support students’ learning processes and to connect them to learning, peers, and school, which might be related to school alienation theory (Morinaj et al., 2020; Havik and Ingul, 2021b). According to this theory, students might be alienated from school in general or from specific aspects of school, leading to a process of increased distancing from different aspects of school (Morinaj et al., 2020) and increased attendance problems. Giving teachers more individual time with SAP students, either face to face or online, might counteract this process. Teachers might use an individualized approach and link schoolwork to their students’ personal interests (Nuttall and Woods, 2013), which might influence the students’ motivation for schoolwork. Some of the teachers in the current study stated that they knew more about the students’ challenges and interests after the period of remote education, which might make it easier to adapt and motivate the students when schools reopened.

Some teachers found that SAP students needed more structure, routines, and close monitoring than was possible during the period of remote education. Teachers might be better positioned to influence this when students attend school. The findings from a study of parents of children with school refusal indicate that students need structures and routines during a school day for them to feel that the environment is safe and predictable (Havik et al., 2014). Teachers found that some parents were not able to structure their child’s schooldays at home; teachers might have a greater possibility to do this at school (Havik and Ingul, 2021a). However, this requires the teachers to have time to do so. This is related to the fact that many teachers were concerned about difficulties in school return because some of the SAP students had developed bad habits during this period, such as staying awake during the night and in bed during the day and not getting up in the morning (Havik and Ingul, 2021a).

Some teachers wanted to involve the home and parents more and to promote close home–school cooperation when the schools reopened. In addition, a few teachers mentioned the need for coordination and cooperation with other services (e.g., for assessment and/or treatment). Some experienced closer cooperation with parents and found that some parents were more involved during the period with remote education, while others experienced difficulties in cooperation and a lack of parental involvement. Therefore, the teachers knew more about how these parents followed up and monitored their child’s schooling and which parents would be more involved in their child’s schooling when the schools reopened. At the same time, previous research indicates that teachers tend to blame the parent/student for problems, and parents tend to blame the school (e.g., Gregory and Purcell, 2014; Havik et al., 2014; Baker and Bishop, 2015; Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Havik and Ingul, 2021a).

Previous research on intervention for SAPs indicates the importance of parental involvement and cooperation within a team, including school–parent cooperation (e.g., Kearney and Graczyk, 2014; Gren-Landell et al., 2015; Finning et al., 2018), and parents emphasize the need for a coordinated team approach (Havik et al., 2014). Moreover, homeschooling is often not recommended as a regular intervention for students with SAPs because some might expect this as a regular intervention and fall into a negative cycle (Thambirajah et al., 2008; Wijetunge and Lakmini, 2011). Therefore, involving and cooperating with parents about the pros and cons of homeschooling is important.

Social Interactions When Schools Reopen

Some teachers stated that social interactions were important upon school return. Some of them believed that school return might be easier because the students missed their peers and school and that interacting with others might be easier upon school return than during the period of remote education. Moreover, the teachers noted the importance of closer monitoring of the students and giving them extra time and attention upon school return. The findings from a study of Norwegian teachers indicated that students mainly performed individual tasks with limited support from teachers during the pandemic (Blikstad-Balas et al., 2022). The study examined students in general but might also be applicable to SAP students. Some of the teachers in the current study learned more about their students’ challenges and interests during this period, but some students required more support for schoolwork, which was less available during school at home than regular school when they met the students physically. This might indicate the need for more teacher support for schoolwork.

Teachers in the current study commented on the importance of good relations between teachers and students and between students and for SAP students to be part of the school community. Teacher support is of great importance for SAP students (Wilkins, 2008; Nuttall and Woods, 2013; Havik et al., 2014, 2015; Hendron and Kearney, 2016), and monitoring and supporting all students might be more difficult during digital lessons, particularly for those who do not participate at all (Havik and Ingul, 2021a). Moreover, social isolation might be a consequence of the pandemic for many students and may be even more difficult for SAP students, who are more vulnerable to social isolation and who had fewer friends at school or conflictual relations before the pandemic (e.g., Heyne et al., 2011; Ingul and Nordahl, 2013; Blöte et al., 2015). Therefore, SAP students might struggle even more upon school return.

School Return

Because most of the teachers believed that school return would be harder for their SAP students, planning for a gradual return was important. Teachers commented on the lack of structure and routines at home and noted that all “breaks” from school make school return more difficult. In addition, some students’ social and academic learning decreased during the period of remote education. This might be related to a negative circle in which students fall into patterns of bad habits and become more isolated and fall behind in their schoolwork (Thambirajah et al., 2008; Wijetunge and Lakmini, 2011). A gradual return to school as quickly as possible is often recommended (e.g., Elliott and Place, 2012; Kearney and Graczyk, 2014). Therefore, when schools reopen, a gradual return for some SAP students might be necessary to reconnect and reengage them with school, peers, and teachers. This should be a main goal for all schools when reopening and is particularly important for SAP students. Some of the preparation activities from the Link program might be useful (Brouwer-Borghuis et al., 2019) to help and prepare the student to gradually face school-related fears and to reengage to the school setting (even the Link program is developed for school refusers). Some of the activities might be to encourage the student to participate in a game or to ask a question in class, moreover, to act as an observer in lessons and group discussions, and then gradually increase the amount and type of participation in school activities they experience as fearful. Such activities must be individually adopted to the student, based on what is fearful in school. In addition, the school should after a closure period start to plan a re-entry program for the whole school, which is carefully described by Capurso et al. (2020). They present some important activities: “facilitate classroom discussions about the event, be open to feelings and uncertainty, provide opportunities for students to reconnect socially and with the environment, shift attention from the stressful memory to an awareness of coping and present facts and provide information gradually increasing the amount of time spent there” (Capurso et al., 2020, pp. 66–68). One example is to reconnect the student to their teachers and peers, which is important after long-term absence (for any reasons). These activities might be helpful for all students, however, in particular for students who are fearful for different school activities. Moreover, Kearney and Childs (2021) recommend a framework serving as a roadmap. This is a multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) model addressing four main domains of functioning (adjustment, traumatic stress, academic status, health and safety) across three tiers of support (universal, targeted, and intensive intervention). For adjustment, they mention routines, social-emotional learning components and classroom management at universal interventions for all students (Kearney and Childs, 2021). This is potential an important model when reintegrating students with SAP after prolonged absence.

Most of the teachers believed that attending school was important for the students, and some even explained that they planned the transition to school in advance with additional tools that might be advantageous.

Some of the teachers who thought that school return might be easier stated that this might be because their student missed their peers and school; moreover, their students’ opportunity for a new start. Social interactions in school are important for all students; therefore, a concern about school at home is the lack of socialization for students who stay at home (e.g., Ray, 2013). However, students with positive social interactions before and during school closure might be inspired by this and want to return to school to be with their peers and teachers. It might also be easier to return if students experience a safe school climate, which is important for SAP students in general (Havik et al., 2014; Hendron and Kearney, 2016), including safe relations, being connected to school, and experiencing a safe learning environment. Some of the teachers noted the importance of closer relations with the SAP student and for students to meet their peers in school.

Conclusion

Homeschooling is controversial for all students, including students with SAPs. The findings from the current study show a variety in teachers’ experiences of remote education during the pandemic, however, most teachers believed that school return would be more difficult for SAP students. The teachers’ experiences might be helpful when planning school return after a prolonged period of absence for any reasons. Interventions for SAP students might be more varied and flexible by using digital solutions to a greater extent, either as part of the students’ plan for gradual return and/or when students do not attend school. The enhanced flexibility and the possibility of varying interventions for SAP students seem to be related to teachers’ increased experiences, skills, and confidence in using digital lessons and digital tools. Furthermore, the teachers were more aware of the importance of tailored adaptations based on the students’ challenges, strengths, and interests in addition to the need to structure and closely monitoring of the students. Some teachers mentioned the importance of involving the home and parents and promoting close home–school cooperation. Another main theme was close relations and social interactions between students and teachers and between peers when schools reopened because the students needed to receive more help than teachers could provide during the remote education period.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research

This study was conducted when all schools had been closed for only 2 months. Experiences might change after a longer period of closure because the pandemic is still a concern for society and schools. Therefore, a study after a longer school closure could provide information on other experiences. Teachers’ experiences after schools’ reopening should also be explored, such as how many of these ideas were used, what worked or did not work and why.

A limitation of this study is that these experiences are based only on teachers’ perspectives because of the lack of previous research on homeschooling. However, other perspectives, such as the perspectives of SAP students, should be investigated.

Remote education during the pandemic differs from regular home education for a few students with SAPs. During the pandemic, remote education at home was provided to all students and was not motivated by parents’ or students’ individual problems. Therefore, a comparison of the current results with traditional homeschooling might be inaccurate.

Another limitation is that this study focused on SAPs in general, even though several types of SAPs exist. It is possible that differentiating between types would have yielded different patterns and experiences, and there might be different effects for different types of SAPs. This might impact how teachers use their experiences for different students and whether school return is harder or easier.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

TH and JI wrote the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to the feedback and comments in the whole process. TH analyzed the data. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ann Kristin Kolstø-Johansen, who prepared the web based SurveyXact and Hege Cecilie Nygaard Barker and Solfrid Helen Naustvik who sent emails to all schools in Norway for teachers to participate. They all work at the University of Stavanger.

Footnotes

- ^ In this article we use “remote education” about the education given at home during school closure caused by the pandemic. It is important to note that the teachers themselves used “homeschooling” when they answered, as this is the term being used in Norway. Moreover, “homeschooling” was used in all the information about this study for the participating teachers. The use of “remote education” is in line with Bozkurt et al. (2020), who use “emergency remote education,” because the practice differs from planned practices (e.g., distance education, e-learning, online education, homeschooling). Moreover, homeschooling and home education as planned practice are being used as synonymous in the article for the readability.

References

Ansari, A., Hofkens, T. L., and Pianta, R. C. (2020). Absenteeism in the first decade of education forecasts civic engagement and educational and socioeconomic prospects in young adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1835–1848. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01272-4

Baker, M., and Bishop, F. L. (2015). Out of school: a phenomenological exploration of extended non-attendance. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31, 354–368.

Blagg, N. R., and Yule, W. (1984). The behavioural treatment of school refusal—a comparative study. Behav. Res. Ther. 22, 119–127. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(84)90100-1

Blikstad-Balas, M., Roe, A., Dalland, C. P., and Klette, K. (2022). “Homeschooling in Norway during the pandemic-digital learning with unequal access to qualified help at home and unequal learning opportunities provided by the school,” in During a Pandemic Primary and Secondary Education During COVID-19. Disruptions to Educational Opportunity, ed. F. M. Reimers (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 177–201.

Blöte, A. W., Miers, A. C., Heyne, D. A., and Westenberg, P. M. (2015). “Social anxiety and the school environment of adolescents,” in Social Anxiety and Phobia in Adolescents. Development, Manifestation and Intervention Strategies, eds K. Ranta, A. L. Greca, L. J. Garcia-Lopez, and M. Marttunen (Cham: Springer), 151–181.

Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., et al. (2020). A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian J. Distance Educ. 15, 1–126. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3878572

Brand, C., and O’Conner, L. (2004). School refusal: it takes a team. Child. Sch. 26, 54–64. doi: 10.1093/cs/26.1.54

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Brouwer-Borghuis, M. L., Heyne, D., Sauter, F. M., and Scholte, R. H. J. (2019). The link: an alternative educational program in the Netherlands to reengage school-refusing adolescents with schooling. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.08.001

Capurso, M., Dennis, J. L., Salmi, L. P., Parrino, C., and Mazzeschi, C. (2020). Empowering Children Through School Re-Entry Activities After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Contin. Educat. 1, 64–82. doi: 10.5334/cie.17

Carroll, H. C. M. (1996). “The role of the educational psychologist in dealing with pupil absenteeism,” in Unwillingly to School, eds I. Berg and J. P. Nursten (London: Gaskell), 228–241.

Dalziel, D., and Henthorne, K. (2005). Parents’/Carers’ Attitudes Towards School Attendance. London: DfES Publications.

de Carvalho, E., and Skipper, Y. (2019). “We’re not just sat at home in our pyjamas!”: a thematic analysis of the social lives of home educated adolescents in the UK. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34, 501–516. doi: 10.1007/s10212-018-0398-5

Egger, H. L., Costello, J. E., and Angold, A. (2003). School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 42, 797–807. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000046865.56865.79

Ek, H., and Eriksson, R. (2013). Psychological factors behind truancy, school phobia, and school refusal: a literature study. Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 35, 228–248. doi: 10.1080/07317107.2013.818899

Elliott, J., and Place, M. (2012). Children in Difficulty: A Guide to Understanding and Helping. London: Routledge.

Engzell, P., Frey, A., and Verhagen, M. D. (2020). Learning inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic. SocArXiv ve4z7. Charlottesville: Center for Open Science, doi: 10.31219/osf.io/ve4z7

Fensham-Smith, A. J. (2021). Invisible pedagogies in home education: freedom, power and control. J. Pedagogy 12, 5–27. doi: 10.2478/jped-2021-0001

Finning, K., Harvey, K., Moore, D., Ford, T., Davis, B., and Waite, P. (2018). Secondary school educational practitioners’ experiences of school attendance problems and interventions to address them: a qualitative study. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 23, 213–225. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2017.1414442

Fjørtoft, S. O. (2020). “Teaching in the time of corona crisis: a study of Norwegian teachers’ transition into digital teaching,” in The Future of Education–10th International Conference (Virtual Edition). (Pixel), (Trondheim: SINTEF), 595–601.

Fortune-Wood, M. (2007). Can’t Go Won’t Go: An Alternative Approach to School Refusal. Gwynned: Cinnamon Press.

Gregory, I. R., and Purcell, A. (2014). Extended school non-attenders’ views: developing best practice. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 30, 37–50. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2013.869489

Gren-Landell, M., Ekerfelt Allvin, C., Bradley, M., Andersson, M., and Andersson, G. (2015). Teachers’ views on risk factors for problematic school absenteeism in Swedish primary school students. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31, 412–423. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2015.1086726

Hancock, K. J., Shepherd, C., Lawrence, D., and Zubrick, S. (2013). Student attendance and educational outcomes: every day counts. Perth: Telethon Institute for Child Health Research.

Havik, T., Bru, E., and Ertesvåg, S. K. (2014). Parental perspectives of the role of school factors in school refusal. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 19, 131–153. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2013.816199

Havik, T., Bru, E., and Ertesvåg, S. K. (2015). School factors associated with school refusal- and truancy-related reasons for school non-attendance. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 18, 221–240. doi: 10.1007/s11218-015-9293-y

Havik, T., and Ingul, J. M. (2021a). Does homeschooling fit students with school attendance problems? Exploring teachers’ experiences during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:720014. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.720014

Havik, T., and Ingul, J. M. (2021b). How to understand school refusal. Front. Educ. 6:715177. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.715177

Hendron, M., and Kearney, C. A. (2016). School climate and student absenteeism and internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems. Child. Sch. 38, 109–116. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdw009

Heyne, D. (2019). Developments in classification, identification, and intervention for school refusal and other attendance problems: introduction to the special series. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.12.003

Heyne, D., Gren-Landell, M., Melvin, G., and Gentle-Genitty, C. (2019). Differentiation between school attendance problems: why and how? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 8–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.006

Heyne, D., Sauter, F. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Vermeiren, R., and Westenberg, P. M. (2011). School refusal and anxiety in adolescence: non-randomized trial of a developmentally sensitive cognitive behavioral therapy. J. Anxiety Disord. 25, 870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.006

Heyne, D. A., and Sauter, F. M. (2013). “School refusal,” in The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety, eds C. Essau and T. H. Ollendick (Chichester: Wiley), 471–517.

Heyne, D. A., Sauter, F. M., and Maynard, B. R. (2015). “Moderators and mediators of treatments for youth with school refusal or truancy,” in Moderators and Mediators of Youth Treatment Outcomes, eds M. Maric, P. J. M. Prins, and T. H. Ollendick (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 230–266.

Horowitz, J. M. (2020). Lower-income parents most concerned about their children falling behind amid COVID-19 school closures. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Ingul, J. M., Havik, T., and Heyne, D. (2019). Emerging school refusal: a school-based framework for identifying early signs and risk factors. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 46–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.005

Ingul, J. M., and Nordahl, H. M. (2013). Anxiety as a risk factor for school absenteeism: what differentiates anxious school attenders from non-attenders? Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 12:25. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-25

Kearney, C. (2008). School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: a contemporary review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 451–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012

Kearney, C. A. (2016). Managing School Absenteeism at Multiple Tiers: An Evidence-Based and Practical Guide for Professionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kearney, C. A., and Childs, J. (2021). A multi-tiered systems of support blueprint for re-opening schools following COVID-19 shutdown. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 122:105919. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105919

Kearney, C. A., and Graczyk, P. (2014). A response to intervention model to promote school attendance and decrease school absenteeism. Child Youth Care Forum 43, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9222-1

Kearney, C. A., and Graczyk, P. (2020). A multidimensional, multi-tiered system of supports model to promote school attendance and address school absenteeism. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 23, 316–337. doi: 10.1007/s10567-020-00317-1

Keppens, G., Spruyt, B., and Dockx, J. (2019). Measuring school absenteeism: administrative attendance data collected by schools differ from self-reports in systematic ways. Front. Psychol. 10:2623. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02623

King, N., Tonge, B. J., Heyne, D., and Ollendick, T. H. (2000). Research on the cognitive-behavioral treatment of school refusal: a review and recommendations. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 20, 495–507. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00039-2

Knox, P. (1989). Home-based education: an alternative approach to ‘school phobia’. Educ. Rev. 41, 143–151. doi: 10.1080/0013191890410206

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., and Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Educ. Res. 49, 549–565. doi: 10.3102/0013189x20965918

Lambert, S., and O’Halloran, E. (2008). Deductive thematic analysis of a female paedophilia website. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 15, 284–300. doi: 10.1080/13218710802014469

Lubienski, C. (2000). Whither the common good? A critique of home schooling. Peabody J. Educ. 75, 207–232.

Maeda, N., and Heyne, D. (2019). Rapid return for school refusal: a school-based approach applied with japanese adolescents. Front. Psychol. 10:2862. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02862

Mayberry, M., Knowles, J. G., Ray, B., and Marlow, S. (1995). Home Schooling: Parents as Educators. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

McShane, G., Walter, G., and Rey, J. M. (2004). Functional outcome of adolescents with ‘school refusal’. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 9, 53–60. doi: 10.1177/1359104504039172

Melvin, G. A., and Tonge, B. J. (2012). “School refusal,” in Handbook of Evidence-Based Practice in Clinical Psychology: Child and Adolescent Disorders, eds P. Sturmey and M. Hersen (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 559–574.

Mitchell, E. (2021). Why English parents choose home education – a study. Educ. 3-13 49, 545–557. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2020.1742185

Monk, D. (2004). Problematising home education: challenging ‘parental rights’ and ‘socialisation’. Leg. Stud. 24, 568–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-121x.2004.tb00263.x

Morinaj, J., Hadjar, A., and Hascher, T. (2020). School alienation and academic achievement in Switzerland and Luxembourg: a longitudinal perspective. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 279–314. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09540-3

NCES (2009). 1.5 million homeschooled students in the United States in 2007. Issue Brief from Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education (NCES 2009–030). Washington, D.C: NCES.

Nelson, J. (2014). Home education: exploring the views of parents, children and young people. Ph.D. thesis. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

Neuman, A., and Guterman, O. (2017). What are we educating towards? Socialization, acculturization, and individualization as reflected in home education. Educ. Stud. 43, 265–281. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2016.1273763

Nuttall, C., and Woods, K. (2013). Effective intervention for school refusal behaviour. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 29, 347–366. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2013.846848

Ray, B. D. (2013). Homeschooling associated with beneficial learner and societal outcomes but educators do not promote it. Peabody J. Educ. 88, 324–341. doi: 10.1080/0161956x.2013.798508

Romanowski, M. H. (2006). Revisiting the common myths about homeschooling. Clear. House 79, 125–129. doi: 10.3200/tchs.79.3.125-129

Rothi, D., and Leavey, G. (2006). Child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and schools: inter-agency collaboration and communication. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 1, 32–40. doi: 10.1108/17556228200600022

Simon, O., Nylund-Gibson, K., Gottfried, M., and Mireles-Rios, R. (2020). Elementary absenteeism over time: a latent class growth analysis predicting fifth and eighth grade outcomes. Learn. Individ. Differ. 78:101822. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101822

Stroobant, E. (2008). Dancing to the music of your heart: home schooling the school resistant child. A constructivist account of school refusal. Ph.D. thesis. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

Stroobant, E., and Jones, A. (2006). School refuser child identities. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 27, 209–223. doi: 10.1080/01596300600676169

Thambirajah, M. S., Granduson, K. J., and De-Hayes, L. (2008). Understanding School Refusal. A Handbook for Professionals in Education, Health and Social Care. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Wijetunge, G. S., and Lakmini, W. D. (2011). School refusal in children and adolescents. Sri Lanka J. Child Health 40, 128–131. doi: 10.4038/sljch.v40i3.3511

Wilkins, J. (2008). School characteristics that influence student attendance: experiences of students in a school avoidance program. High Sch. J. 91, 12–24. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2008.0005

Keywords: school attendance problems, teachers’ experiences, remote education, homeschooling, COVID-19 pandemic, school return

Citation: Havik T and Ingul JM (2022) Remote Education/Homeschooling During the COVID-19 Pandemic, School Attendance Problems, and School Return–Teachers’ Experiences and Reflections. Front. Educ. 7:895983. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.895983

Received: 14 March 2022; Accepted: 16 May 2022;

Published: 09 June 2022.

Edited by:

Carolyn Gentle-Genitty, Indiana University Bloomington, United StatesReviewed by:

Marcela Pozas, Humboldt University of Berlin, GermanyCatarina Rodrigues Grande, University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2022 Havik and Ingul. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Trude Havik, trude.havik@uis.no

Trude Havik

Trude Havik Jo Magne Ingul

Jo Magne Ingul