Anti-corruption Action: A Project-Based Anti-corruption Education Model During COVID-19

- 1Pancasila and Citizenship Education Study Program, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 2Master of Islamic Education, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 3Department of Islamic Education, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 4Faculty of Law, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Education can be used as a preventive measure to decrease corruption cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, anti-corruption education is not enough with cognitive knowledge since more emphasis should be laid on affective and psychomotor actions. A project-based learning model was used to package these actions based on factual learning resources. Therefore, this study aims to develop a project-based learning model in online anti-corruption during the pandemic. Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan (PPKn) is the Pancasila and Citizenship Education in Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia was used as research setting. Furthermore, this participatory thematic study uses 28 PPKn students for the anti-corruption education course in the odd semester 2020/2021. Google forms, online focus group discussions, and documentation (task reports) methods were adopted for data collection, and the analysis was conducted through reduction, classification, and interpretation. The results showed the development of fourteen anti-corruption actions in online media, and each one has a different target group according to its content. Therefore, anti-corruption learning does not stop at the realm of cognition but also affection which has an impact on the transformation of social media. The actions to prevent corruption are still needed even though the pandemic is over considering the new confirmed cases.

Introduction

Anti-corruption education (ACE) policies in higher education prevent corruption during COVID-19 (Suyadi et al., 2019) by equipping, training, and familiarizing students with behavior and action for themselves, their families, and the surrounding community. This goal has a major impact on the realization of a corruption-free Indonesia (Sumaryati and Hastuti, 2019). Therefore, anti-corruption education is presented in a creative, interesting, fun, and achievable way by valuing different learning resources from the real life of a person, a society, a nation, and a State (Suyadi et al., 2020). Furthermore, series of problems will be experienced when learning is conducted online since it is more likely to transfer knowledge and communication skills. Therefore, it is very important to choose learning methods and strategies that can train and develop aspects of action skills (Suyadi and Suyadi, 2019). ACE should be accompanied by strategies that allow students to learn about anti-corruption in online learning. When online anti-corruption education learning is conducted through material explanation, discussion, and debate, the outcomes achieved are only in the cognitive and affective aspects (Suyadi et al., 2020). This is because students have not been trained to conduct genuine anti-corruption activities in social life.

So far, a lot of research on anti-corruption education has been carried out (Devayanti, 2015; Kristiono et al., 2020; Sumaryati, 2021) but these studies are limited to the realm of cognition which do not affect the action plan (Ma’ruf et al., 2019; Yusmaliana et al., 2020). Even the insertion of anti-corruption education in Civics subjects tends to be text book oriented and too cognitive but less affective (Sumaryati, 2014; Suyadi et al., 2021). As a result, students only know the concept of corruption but do not dare to fight corruption and they look for legal loopholes for corruption instead (Wibowo, 2013). In this case, S. R. Maulina Azmi recommends a new approach in anti-corruption education that is more transformative and affective, namely an action plan (Azmi, 2020).

This study aims to examine the implementation of anti-corruption actions as an online project-based ACE learning model to develop students’ anti-corruption knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Anti-corruption education supports the National Movement for Mental Revolution (GNRM) to improve and build the character of the Indonesian nation. This movement is referred to as the values of integrity, work ethic, and cooperation toward a dignified, modern, advanced, and prosperous nation (Tim Penulis Buku Pendidikan Antikorupsi, 2018). The ACE learning is directed at moral action to reach the level of having the will and the habit of implementing anti-corruption values in everyday life (Sumaryati and Hastuti, 2019). Efforts are made to reach the aspects of reason, feeling, and intention of the students. The targets should be supported by learning methods, media, strategies, and evaluations that are consistent with the materials, competencies, and objectives.

The offline ACE learning process was relatively carried out with several models before the pandemic (discussion, role-playing, case analysis, and anti-corruption action). However, the government’s policy in preventing the spread has changed the system and pattern of learning from offline to online. In this case, lecturers should prepare to implement ACE learning in a more creative, fun, and meaningful way. Therefore, some positive impacts of online learning, such as facilitating activities anywhere and anytime, making students more sensitive to learning technology, learning styles can be self-regulated, time efficiency, and they can study more calmly and focused (Ningsih, 2020), Increased cost-effective boarding and meals, as well as familiarity with technology (Fitria and Saputra, 2020), can be maximized. Meanwhile, the negative impact such as limited interaction between lecturers and students as well as a less optimal explanation of material can be anticipated (Megawanti et al., 2020; Ningsih, 2020). Other negative effects include students getting tired more easily resulting in hampered socialization with friends (Fitria and Saputra, 2020). Many of them are not being used to learning on their own effectively (Owusu-Fordjour and Hanson, 2020) due to limited internet access, loads of assignments, unattractive delivery of material by lecturers, and poor selection of learning methods, and media (Matdio, 2019). The implementation of online learning at Universitas Ahmad Dahlan is regulated in Circular No. R/389/D/VIII/2020 on Office and Lecture Activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature Review

Anti-corruption education learning in the Pancasila and Citizenship Education Study Program is also carried out online according to the policies of the university. The problems encountered include the limitations of learning methods and direct communication forums due to the lack of smooth internet networks, as well as difficulties in assessing attitudes and skills to act (Subkhan, 2020). Some of these problems cause anti-corruption education learning to be less meaningful. Furthermore, Edi Subkhan stated that ACE learning is dull and absurd (Subkhan, 2020) since the learning only discusses abstract values, norms, and morality. However, this is absurd as the learning is out of context and therefore students find it pointless to study and try to fight corruption unless the potential for corrupt practices is addressed in their school or other immediate settings.

Some online ACE learning’s provide continuous experiences in the form of action projects as contextualization of anti-corruption behavior. Assignments are still in the form of problem analysis and the creation of educational tools in the form of concrete anti-corruption actions. Meanwhile, Kamil (Kamil et al., 2018) and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania (Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania, 2006) stated that formal education against corruption runs the risk of becoming a purely cognitive discourse dealing only with corrupt behavior. This aims to complete the subject matter without considering the impact of learning for students and without proper contextualization (Suyadi, 2019). Furthermore, respondents from Hong Kong and Indonesia expressed concern over the gap between the anti-corruption educational values of students in formal education and the realities in society. The concern is also in terms of the way ACE learning attracts students. Also, Moh. Najih and Fifik Wiryani stated that the introduction of anti-corruption awareness to students is not enough (Najih and Wiryani, 2021). Moreover, the curriculum should not be limited to teaching and practice but should also be like a campaign for students. Lukman Hakim stated that the anti-corruption education included in the PPKn Class II subject for Odd Semester Junior High School has a basic competency domain, which is focused on cognitive aspects. Therefore, teacher creativity is needed to be developed into effective and psychomotor aspects (Hakim, 2012). The same thing was stated by Baharudin and Ita Sarmita Samad (Baharuddin, 2019).

Project-based learning is one model that makes students active and independent, and it is used to apply the knowledge already possessed as well as train various thinking, attitudes, and concrete skills (Yuliana, 2020). The several advantages of project-based learning include increasing motivation as well as improving problem-solving, collaborative, and resource management skills (Suciani et al., 2018). Three common categories of project inquiries for students are skill development, problem investigation, and solution development (Lestari et al., 2016). While online anti-corruption training did not implement project-based learning, it hampers the goal of empowering students to be critical and competent in implementing the measures. The ability to think and be critical is one of the skills of the 21st century, and students are trained to solve problems with critical thinking (Tinenti, 2018; Azizah and Widjajanti, 2019). Project-based learning promotes students to think critically, solve problems, collaborate, and try various forms of communication. Meanwhile, students are triggered to learn through inquiry, working collaboratively to study and create projects that reflect their knowledge. They are also trained to utilize technology to become communicators and problem solvers, thereby getting benefits from the learning (Suyadi et al., 2022). Project-based learning provides opportunities for students to learn in-depth knowledge or content and 21st-century skills (Zubaidah, 2019).

Referring to the strengths and weaknesses of project-based learning, the “Anti-Corruption Action” project is very interesting to be implemented in the Anti-Corruption Education course. The indicator of the success of the PAK model based on “anti-corruption action” lies in students’s success in preparing anti-corruption action plans, anti-corruption action media, and carrying out anti-corruption actions in their respective communities. The limitations of the anti-corruption action-based PAK model during the COVID-19 pandemic are in terms of selecting material/action themes that are in accordance with the situation and community needs. Moreover, the understanding of anti-corruption education by students is not comprehensive. In an effort to overcome these limitations, researchers conducted supervision. Supervision prior to the implementation of anti-corruption actions is carried out with students presenting the anti-corruption action plan in front of lecturers and other students (material, media, infrastructure, target community, and implementation time). Meanwhile, during anti-corruption actions, supervision is carried out with lecturers joining virtual anti-corruption actions (Google meet and or WA Group). The results are intended to convey a true picture of the fact that project-based online learning from ACE can still convey knowledge about corruption and anti-corruption, and train professional skills and counter-literacy.

Materials and Methods

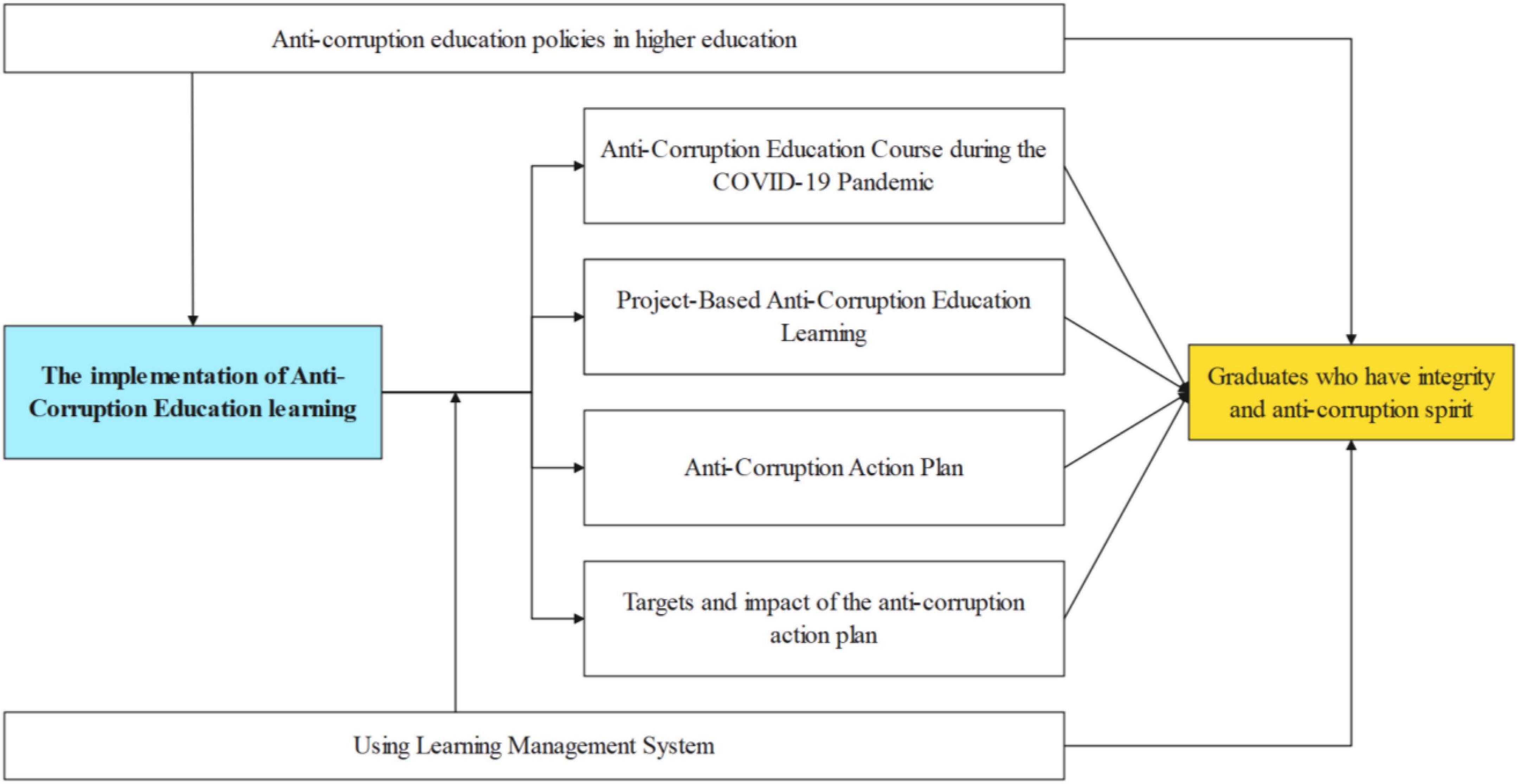

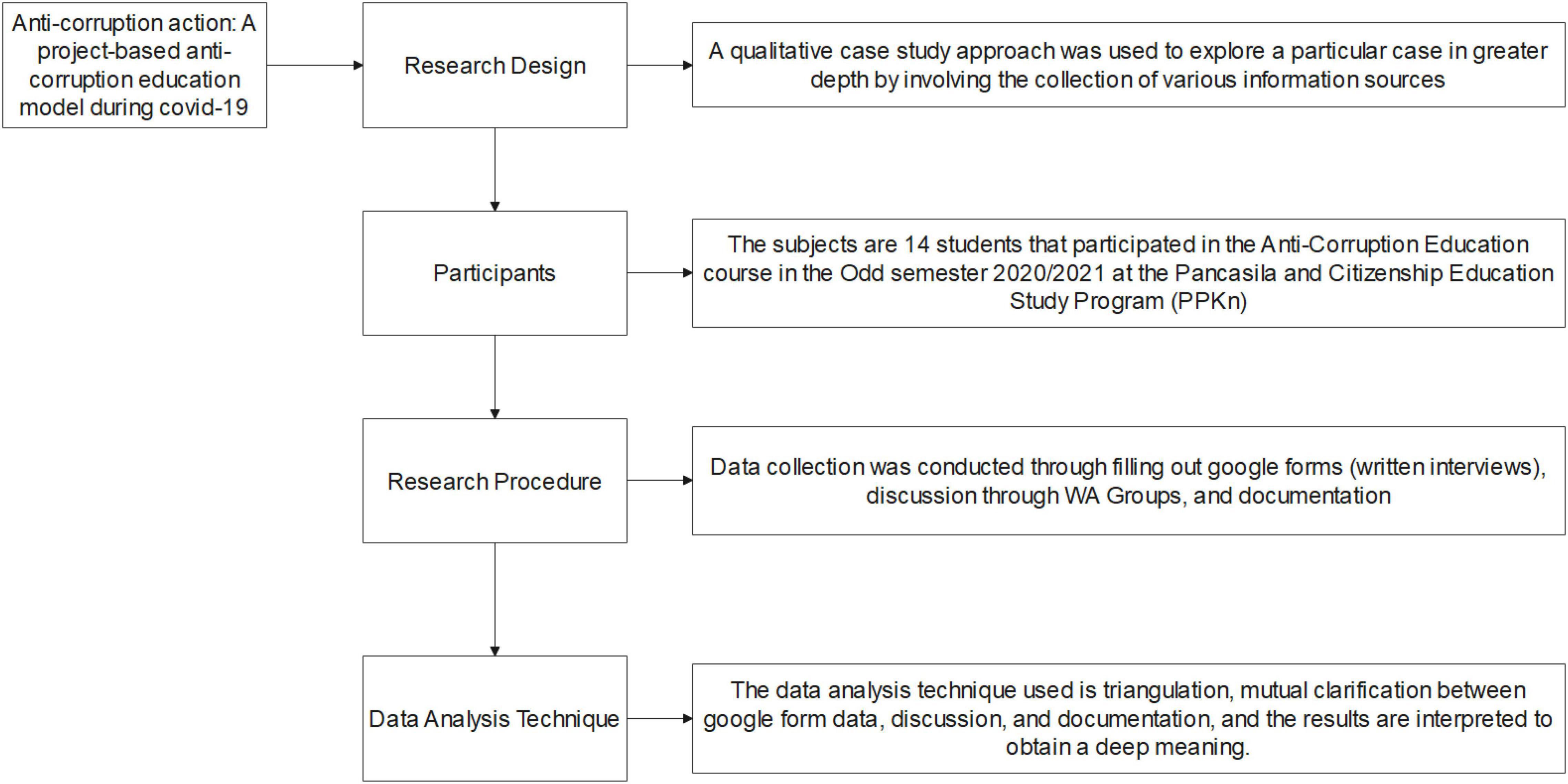

A qualitative case study approach was used to explore a particular case in greater depth by involving the collection of various information sources (Denzin, 2008). It is chosen because the object specifically examines online project-based ACE learning. Furthermore, it was also proved that learning can develop students’ higher-order thinking skills and creativity in packaging anti-corruption education for the community. Figure 1 explains the research flow in this article.

Figure 1. Flow research anti-corruption action: A project-based anti-corruption education model during COVID-19.

Research Design

This study was thematically conducted and was focused on project-based ACE learning on student anti-corruption actions in their respective communities. Furthermore, the lecture supervised the students during the semester to study and discuss ACE materials, plan and implement anti-corruption actions, as well as assist in preparing reports. This research is a case study. Not many other universities have done it during the Covid 19 pandemic. Thus, a case study is the right choice. In addition, the choice of case studies is widely used in specific cases that are unique.

Participants

The subjects of this study were 14 students from 16 participants (87.5%) in the Anti-Corruption Education course who are in odd semester 2020/2021 at the civic education Study Program (PPKn). The subjects are 14 students that participated in the Anti-Corruption Education course in the odd semester 2020/2021 at the Pancasila and Citizenship Education Study Program (PPKn), Faculty of Teacher Training and Education. The ACE learning in the PPKn Study Program is an elective course and was first implemented online with project-based learning in this odd semester 2020-2021. Furthermore, the PPKn course is the only study program at Universitas Ahmad Dahlan that formally includes Anti-Corruption Education in the learning curriculum structure1. The researchers gained ethical approval for the study from Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Research Ethics Approval Committee.

Research Procedure

Data collection was conducted through filling out Google forms (written interviews), discussion through WA Groups, and documentation. Furthermore, the Google forms focus on the reasons for taking the ACE course, the learning process (platforms, methods, media, evaluations, outcomes), students’ feelings about attending lectures, responses about the anti-corruption movement, and things that need to be improved. The discussion through WA groups and Google focuses on planning anti-corruption actions in the community. Meanwhile, the documentation method of data collection is in the form of reports on student anti-corruption actions in the community.

Data Analysis Technique

The data analysis technique used is triangulation, mutual clarification between Google form data, discussion, and documentation, and the results are interpreted to obtain a deep meaning. Interpretation in research is to discuss and find the meaning of anti-corruption action project-based learning in training students’ abilities to process and translate knowledge, and anti-corruption attitudes into anti-corruption action behavior. In addition, the interpretation is also directed to find and discuss the impact of learning accompaniments based on anti-corruption action projects.

Findings and Discussion

For ease of reading and comprehension, findings are presented first followed by discussion. The Findings sub-title and Discussion sub-title are presented separately. This section should occupy the most part, minimum of 60%, of the whole body of the article. Figure 2 explain anti-corruption action: a project-based anti-corruption education model.

Findings

The implementation of Anti-Corruption Education learning at the Pancasila and Citizenship Education Study Program, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan is consistent with the applicable lecture operational guidelines. During the pandemic, lectures were held online in a balanced combination of synchronous and asynchronous. These lectures provided opportunities for students to be creative and innovative in using and developing learning resources. Meanwhile, UAD implements the “Anti-Corruption Action” project-based learning model for the ACE in the PPKn study program. The aim is for the students to actively, creatively, and innovatively develop and implement educational materials in their respective communities. This project-based learning is in the form of anti-corruption actions for the community. The results contain the reasons students partake in anti-corruption education courses, the ACE learning process responses/attitudes toward the learning, and the outcomes.

Anti-corruption Education Course During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The Anti-Corruption Education in the PPKn Study Program is an elective course, and the number of participants in the odd semester 2020/2021 was 22 students. Meanwhile, 6 have not been active in lectures since the beginning, 1 did not take the midterm exam, and 1 did not take the final exam. Therefore, the actual number of active students that participated in learning and took the exam was 14 people2. Students study anti-corruption courses because of their perception of the importance, the many problems of corruption in Indonesia, desire to learn and know more about anti-corruption and are able to apply it in their families, communities, and countries. They are also eager to know the preventive measures in curbing corruption, and they use this knowledge to prevent crime (corruption) in themselves and those around them. Some students take the ACE course due to the unavailability of others, and their interest level is usually increased after attending lectures.

Project-Based Anti-corruption Education Learning

The weight of the Anti-Corruption Education course at the Pancasila and Citizenship Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan is 2 credits. Furthermore, face-to-face meetings are held 14 times according to applicable regulations. During the pandemic, the ACE learning process was conducted using the UAD E-Learning Management System (LMS) platform, WA Group, and Google meet. Meanwhile, LMS was used to provide lecture material, collect assignments and their assessments, and conduct mid-semester exams. The WA Group provided material explanations with voice notes as well as accommodate aspirations and opinions directly from students. Meanwhile, Google meet provided explanations of lecture materials, discussion of materials and plans as well as the implementation of student anti-corruption actions in their respective communities.

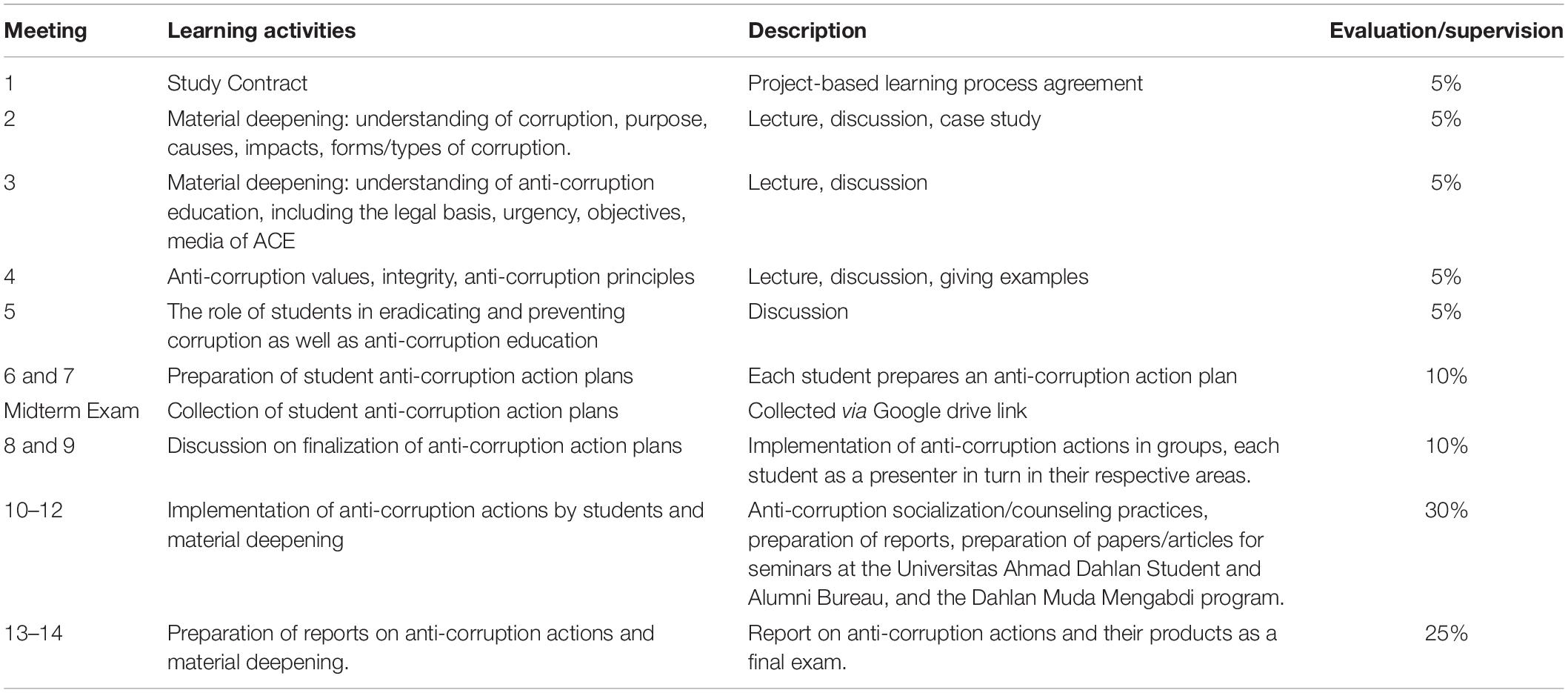

The learning process was conducted by agreeing on a contract, providing materials, discussions, and assignments (preparing anti-corruption action plans, implementing anti-corruption actions, and preparing reports). The final evaluation implemented an anti-corruption action plan and preparing a report. Meanwhile, the lecture procedures in the learning contract were agreed upon during the first meeting. The second to fifth meetings was the deepening of teaching materials while the sixth to seventh was the preparation of anti-corruption action plans. A midterm exam in the form of collecting an anti-corruption action plan was held after the seventh meeting. The eighth and ninth meetings were discussions on the finalization of the anti-corruption action plan. Furthermore, the tenth to twelfth meetings were the implementation of anti-corruption actions in their respective target communities while continuing to conduct material exploration. During this period, those that have conducted anti-corruption actions were allowed to continue with the preparation of reports. A paper that was presented at a seminar held by the Student and Alumni Bureau in December was also compiled. Subsequently, the thirteenth and fourteenth meetings were the preparation of reports as material for the final semester examination. The deepening of the material was conducted in each class schedule even though students took anti-corruption actions in the community as well as compiling reports and articles. In addition, the deepening was adjusted to the material chosen by the students in the anti-corruption action, and Table 1 showed the lecture process.

Students stated that online ACE learning continues to run according to the specified schedule and is fun. Furthermore, the lecture materials were accepted because they were presented on the https://elearning.uad.ac.id page, and explanations were given with voice notes or discussions through WA Group and Google meet. They were supported by providing examples that are consistent with the material and the realities of student life. This is in accordance with the following student statements:

“The ACE course is not an obstacle during the pandemic since many learning media can reach students effectively using WAG, YouTube, and Zoom.” Furthermore, they are always involved in discussion classes with the lecturers “This course is very enjoyable because the lecturer always provides strong support and is always active and open in conducting activities, both learning and participating in anti-corruption actions.” Furthermore, another statement stated “This course is fun, and even though it is conducted online, the teaching and learning process is very interesting. The study of anti-corruption course is very interesting because it contains a lot of knowledge that I have never received or experienced before.”

The opinions of the respondents show that online learning can still fill in the most important elements, namely a discussion space between students and lecturers and among themselves. Furthermore, lecturers can adjust to the actual environment of students to increase their experience and reflect on the experiences gained from the learning process. This is consistent with the study conducted by Laurillard, where the four essential component processes of learning were stated. They include (1) discursive, which enables discussion between students and teachers, each expressing their point of view on certain aspects of the description of the other; (2) adaptive, where the teacher adjusts students’ interactions with the environment; (3) interactive, allowing students to interact in a way that enhances their experience; (4) reflective, where students reflect on the experience and adapt to their conceptions and descriptions (Laurillard, 1993).

Online learning has become popular because it provides more flexible access and content (Zulherman et al., 2021). Some of the advantages include a. increasing the availability of flexible learning experiences following their learning styles, b. efficiency in compiling and disseminating instructional content, c. providing and supporting complex learning facilities, d. supporting “participatory” learning, e. providing individualized and differentiated instructions through various feedback mechanisms, f. allowing students to learn similar content at different speeds or achieve different learning goals (Schwen and Hara, 2004; Fidaldo and Thormann, 2017). The respondents’ opinions are also in accordance with Jamwal and Kobayashi (Jamwal, 2012; Kobayashi, 2017) which stated that 71 out of 128 students chose interactive learning and 80% stated that email, assignments, audio presentations, collaboration, and online video were the most useful media.

Anti-corruption Action Plan

The project-based education learning model in the form of anti-corruption actions by students for the surrounding community provides comprehensive competencies to students. The following are responses to the anti-corruption actions as the implementation of project-based ACE learning. Generally, students participating in the ACE course in the UAD PPKn study program respond positively to this anti-corruption action program. Furthermore, they can conduct theories and practicals by directly implementing and developing ACE materials in their respective communities. The following is a student statement:

“I think that anti-corruption education lecture during the current pandemic is quite conducive. The material that has been delivered is also balanced with direct involvement in making programs for the surrounding community even though it is conducted online”

Students also agree with the existing anti-corruption learning strategy since it helps them understand the ACE material more actively. They can develop their creativity and imagination using anti-corruption action strategies. The following are student responses:

“I agreed because the preparation of an anti-corruption action plan makes students active and directly involved in life, both in the community, family, and country. Furthermore, the action plan has a large positive impact and is very beneficial for the public to resolve corrupt behavior.” This was reinforced by another student stating that “This learning model makes students more active in understanding the materials delivered, and the learning model can develop creativity and imagination.”

Student opinion on anti-corruption measures that can induce them to be involved in the community and implement the material is consistent with the study conducted by Neo et al. (2015) in Malaysia. The results showed that 86.4% of Malaysian students stated the ease and flexibility of access, 81.8% understood the content, and 78.8% found the material useful and informative. This integration will work very well since Education 4.0 is an era in which the implementation of technology has to be implemented (Neo et al., 2015). An important aspect of this integration is access to the actual environment as a learning resource that forms a great learning experience. This is due to the interaction between the characteristics and environment of students. Furthermore, the interaction forms interactive learning, the use of technology to explore, and the right mix of teacher and technology.

Targets and Impact of the Anti-corruption Action Plan

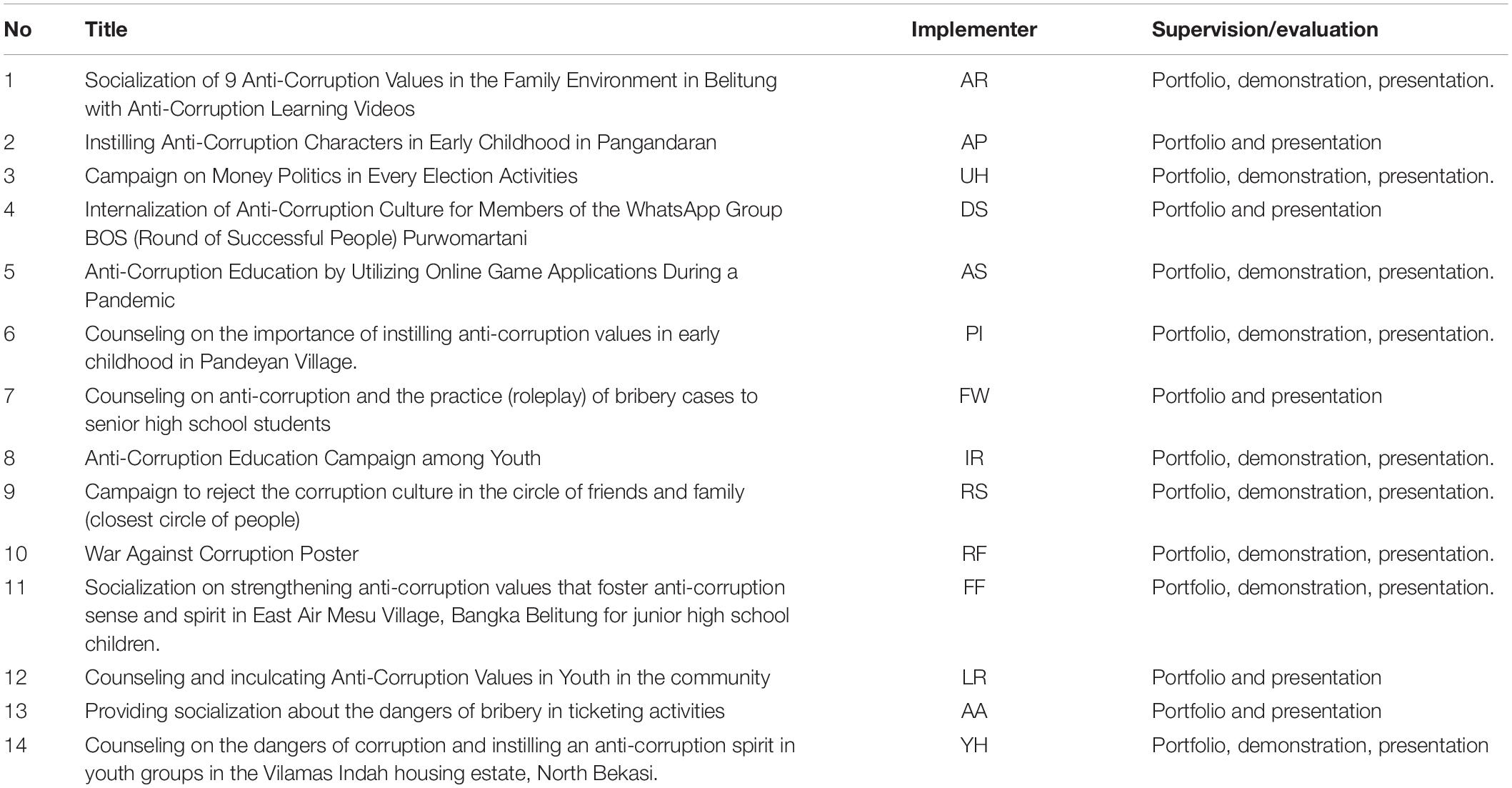

Fourteen titles of anti-corruption action plans were obtained from the discussion activities held at the fourth to seventh meetings. These action plans were collected during the midterm exams, and after it was finalized after the eighth and ninth meetings with the guidance of the lecturer. Furthermore, the students conducted anti-corruption actions on their respective targets after it was perfected. Table 2 showed the fourteen titles of the anti-corruption action plans.

The anti-corruption action media made were videos, interactive PPT, and word wall games, and they were conducted in groups of four to five students. Meanwhile, each of the three groups chose one of the action plans to be implemented. The materials, media, and study to be used were also discussed, and the members agreed with the communities in their respective areas about the timing of anti-corruption actions and the platforms used. Furthermore, an anti-corruption action plan was selected and conducted online. The media used were video, interactive PPT, and word wall games. The first group, “Prevention of Anti-Corruption Outbreaks by Giving the SENASI (Nine Anti-Corruption Values) Vaccine in the Family,” was held on Tuesday, December 1, 2020. Meanwhile, the second was held on Saturday, January 1, 2021, with the title “Counseling on Corruption and Instilling the Anti-Corruption Spirit in Youth Groups at the Vilamas Indah Housing Estate, North Bekasi.” The third group was held on Saturday, January 2, 2021, with the title “Utilizing Wordwall Online Game Applications in Strengthening Anti-Corruption Characters during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The material in the learning media was packaged in the form of videos and interactive PPT. The learning media can be accessed at the following links https://youtu.be/FLchszdyXHM, https://youtu.be/F7ONKgl1B6M, https://youtu.be/FLchszdyXHM. In addition, the implementation of student anti-corruption actions was conducted online by empowering the WA group forum.

Referring to the description of the research results, the project-based PAK learning “Anti-corruption Action” has a novelty compared to PAK learning with other learning models (role playing, discussion, problem-based learning). The novelty found with this PAK learning model is that students can mix anti-corruption knowledge, attitudes, and skills in the form of planning and implementing anti-corruption actions around their respective residences. Students are able to cooperate with the surrounding community, and they can arrange anti-corruption action media (videos, animations, pictures). Some students present their experiences of anti-corruption actions in scientific pulpits (seminars). Thus, students are better able to combine aspects of their knowledge with aspects of action skills. Some of these student skills have not been formed in PAK learning with other models (case studies, role playing, investigations).

Discussion

Generally, internal, and external factors cause students to choose the ACE course. Based on some of the reasons presented, the internal factor is the student’s motivation to learn more about corruption and anti-corruption education, and as agents of change to achieve a society, which is more dominant than the external factor. In this case, the external factor is the unavailability of elective courses, which makes students pick interest in the ACE course. This provides an understanding of knowledge about corruption and anti-corruption, allows students to behave intelligently and boldly toward corruption and corrupt behavior. Furthermore, there is the implementation of anti-corruption values in all aspects of life (Lubis, 2019).

The learning process, which combines the e-learning system, WA group, Google Measure, and practice, helps students better understand the course material. This is because they have the opportunity to develop their ability to understand, analyze, develop, and implement the concepts learned. Meanwhile, in the preparations and implementation of anti-corruption actions, students have the opportunity to develop materials, create learning media, and practice socialization and counseling to their respective target communities. Generally, those participating in the Anti-Corruption Education course think that project-based ACE learning is fun and creates curiosity. Therefore, they are more interested in discussing anti-corruption values and corrupt behavior. This is because the material is easily understood, however, it is the most frequently violated by the community (Suyadi and Sutrisno, 2018). There are few things to consider in this project-based ACE learning, some students are still not punctual in attending lectures online due to the internet network or bad weather. However, in this project-based PAK learning, according to students, there are things that must be considered such as punctuality in attending lectures online. Some students are not on time due to the internet issue or bad weather.

Based on the description of the Anti-Corruption Education learning process at the UAD PPKn Study Program and the student’s responses or opinions, the online project-based ACE learning process transfers knowledge about corruption and anti-corruption values, train attitudes, and invite/influence others to take action against corruption. In line with the results of research by Kurniawan Arizona, Zainal Abidin, Rumansyah, project-based online learning provides opportunities for learners to explore concepts more deeply and fundamentally (Arizona et al., 2020). Meanwhile, Syaad Patmanthara believe that project-based learning can improve student learning activities, improve learning outcomes for aspects of student knowledge, improve learning outcomes for aspects of student attitudes in courses, and improve learning outcomes for aspects of student skills (Patmanthara, 2017). Some were very interested in the nine anti-corruption values, and they were able to explain and implement them in each of their activities. Meanwhile, students that did not take the course as their first choice became interested in ACE learning. Thus, the material for anti-corruption values (honest, caring, independent, responsible, hardworking, simple, brave, and fair) is very important to improve the development of materials, media, and time allocation. Considering that this material is very closely related to everyday life and is the most vulnerable to being violated.

Referring to the online project-based ACE learning experience in the PPKn Study Program, the support of lecturers/teachers, methods, strategies, learning media were strengths for the success of the learning process. This is in line with Ibrahim Bali Pamungkas and Wahyu Andri Wibowo and Angga Juanda (Fawaiti et al., 2020; Sopacua and Sugiharto, 2020; Pamungkas et al., 2021; Silvia Mona, 2021) which states that learning success is determined by internal and external factors. Internal factors are within each student, and they include intentions, enthusiasm, mindset, hard work, discipline, and responsibility. Meanwhile, external factors are not found within, and they include the parties involved (lecturers/teachers, employees, infrastructure, regulations).

The positive response in ACE learning gives a signal that students are ready to play a role in preventing corruption and corrupt behavior through the implementation of anti-corruption education in the community. This is in accordance with the statement of the Anti-Corruption Education Book Writing Team that students have a strategic position in the context of political movements and social perspectives (Tim Penulis Buku Pendidikan Antikorupsi, 2018). Some of the strategic positions provide a wider role in conducting anti-corruption action movements (Burhanudin, 2019). The strategic roles of students in anti-corruption education include as agents of change, creators of a campus environment with integrity, community educators, criticizing policies (Kemendikbud, 2013; Ma’ruf et al., 2019; Setiani, 2020; Dewantara et al., 2021).

Referring to the dynamics and outcomes of project-based ACE learning, it was stated that this learning model can train and develop students’ abilities in terms of understanding the material, compiling learning media, processing materials, responding to community realities, conveying material, and influencing/inviting others not to behave corruptly (Suyadi et al., 2020). This is consistent with Sucilestari and Arizona, where it was stated that project-based learning can make the learning process more effective in improving personal, social, academic, and vocational skills (Sucilestari and Arizona, 2018). Therefore, the personality, professional, social, and pedagogical competencies are addressed. Furthermore, students prove their ability to explain anti-corruption education materials, specifically the nine values coherently and clearly, the ability to create anti-corruption learning/socialization media, developing materials in the form of scientific articles presented in seminars, community service programs, and scientific publication media (scientific journal). This is consistent with the study conducted by Chasanah, where project-based learning in ACE improves learning outcomes in the form of student’s creative thinking and science process skills (Chasanah et al., 2016). The results also showed that ACE is a discussion of values, and it is contextual, fun, and not dull (Subkhan, 2020).

Conclusion

Anti-corruption action is a new model in project-based anti-corruption education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The online “Anti-Corruption Action” is a PAK learning model that trains students to be able to develop and collaborate on aspects of knowledge, attitudes, and skills in a creative and fun way. This is evidenced by the ability of students to explain anti-corruption action materials in a coherent manner (knowledge aspect), students’ ability to create interesting and fun anti-corruption action media (skills aspect), students’ ability to respond to questions and public responses about corruption (attitude aspect), student abilities develop material in the form of scientific articles (collaborating aspects of knowledge and skills), and students’ ability to interact and communicate with the surrounding community (skills aspect). Thus, the implementation of the project-based learning model “Anti-corruption Action” can bring closer to achieving the educational goals of anti-corruption knowing, anti-corruption feeling, anti-corruption doing, and anti-corruption habituation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Universitas Ahmad Dahlan. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

Sumaryati, Suyadi, ZN, and AA: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the head of the Pancasila and Citizenship Education Study Program, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, for teaching and guiding students in the Anti-corruption Education course, as well as parents and the surrounding community for providing opportunities to learn ACE. Furthermore, we would also like to thank the Student Affairs (BIMAWA-UAD) for creating a policy that allows students to be creative and participate in the 2021 Anti-corruption Education course.

Footnotes

References

Arizona, K., Abidin, Z., and Rumansyah, R. (2020). Pembelajaran Online Berbasis Proyek Salah Satu Solusi Kegiatan Belajar Mengajar Di Tengah Pandemi Covid-19. Jurnal Ilmiah Profesi Pendidikan 5, 64–70. doi: 10.29303/jipp.v5i1.111

Azizah, I. N., and Widjajanti, D. B. (2019). Keefektifan pembelajaran berbasis proyek ditinjau dari prestasi belajar, kemampuan berpikir kritis, dan kepercayaan diri siswa. Jurnal Riset Pendidikan Matematika 6, 233–243. doi: 10.21831/jrpm.v6i2.15927

Azmi, S. R. M. (2020). Implementasi Pendidikan Antikorupsi Pada Mata Kuliah PKn Berbasis Project Citizen di STMIK Royal Kisaran. J. Sci. Soc. Res. 3, 54–67.

Baharuddin, I. S. S. (2019). Developing Students’ Character through Integrated Anti-Corruption Education. Edumaspul: Jurnal Pendidikan 3, 112–121. doi: 10.33487/edumaspul.v3i2.146

Burhanudin, A. A. (2019). Kontribusi Mahasiswa dalam Upaya Pencegahan Korupsi. Jurnal El-Faqih 5:1. doi: 10.29062/faqih.v5i1.40

Chasanah, A., Khoiri, N., and Nuroso, H. (2016). Efektivitas Model Project Based Learning terhadap Keterampilan Proses Sains dan Kemampuan Berpikir Kreatif Siswa pada Pokok Bahasan Kalor Kelas X SMAN 1 Wonosegoro Tahun Pelajaran 2014/2015. Jurnal Penelitian Pembelajaran Fisika 7, 19–24. doi: 10.26877/jp2f.v7i1.1149

Devayanti, D. G. S. (2015). Implementasi Pendidikan Anti Korupsi Dalam Mata Pelajaran Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan Di Smk Negeri 1 Singaraja. Jurnal Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan 3, 1–15.

Dewantara, J. A., Hermawan, Y., Yunus, D., Prasetiyo, W. H., Efriani, E., Arifiyanti, F., et al. (2021). Anti-corruption education as an effort to form students with character humanist and law-compliant. Jurnal Civics: Media Kajian Kewarganegaraan 18, 70–81. doi: 10.21831/jc.v18i1.38432

Fawaiti, A., Setyosari, P., and Sulthoni, S. U. (2020). Identification of Factors Affecting of Character Education Program on High School Students’ Self-Regulation Skills. J. Educ. Gifted Young Scient. 8, 435–450. doi: 10.17478/jegys.683165

Fidaldo, P., and Thormann, J. (2017). Reaching students in online courses using alternative formats. Internat. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 18, 139–161. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i2.2601

Fitria, P. A., and Saputra, D. Y. (2020). Dampak Pembelajaran Daring terhadap Kesehatan Mental Mahasiswa Semester Awal. J. Ris. Kesehat. Nas 4, 60–66. doi: 10.37294/jrkn.v4i2.250

Hakim, L. (2012). Model Integrasi Pendidikan Anti Korupsi dalam Kurikulum Pendidikan Islam. Jurnal Pendidikan Agama Islam: Taklim 10, 141–156.

Jamwal, G. (2012). Effective Use of Interactive Learning Modules in Classroom Study for Computer Science Education. Logan, UT: Utah State University.

Kamil, D., Mukminin, A., Ahmad, I. S., and Kassim, N. L. A. (2018). Fighting Corruption Through Education in Indonesia and Hong Kong: Comparisons of Policies, Strategies, and Practices. Al - Shajarah. IIUM 2018, 155–190.

Kemendikbud, R. I. (2013). Buku Pendidikan Anti-Korupsi Untuk Erguruan Tinggi. Jakarta: Kemendikbud.

Kobayashi, M. (2017). Students’ Media Preferences in Online Learning. Turkish Online J. Dist. Educ. 18, 4–15. doi: 10.17718/tojde.328925

Kristiono, N., Astuti, I., and Uddin, H. R. (2020). Implementasi Pendidikan Anti Korupsi di SMK Texmaco Pemalang. Integralistik 31, 13–21.

Laurillard, D. (1993). Balancing the Media: Learning, Media, and Technology. J. Educ. Televisi. 19, 81–93. doi: 10.1080/0260741930190204

Lestari, D. P., Fatchan, A., and Ruja, I. N. (2016). Teori, Penelitian, dan Pengembangan. Jurnal Pendidikan 1, 475–479.

Lubis, S. (2019). Tinjauan Normatif Kurikulum Pendidikan Agama Islam Dalam Penanaman Nilai-Nilai Anti-Korupsi. Jurnal Murabbi 2019:2.

Ma’ruf, M. A., Santoso, G. A., and Mufidah, A. M. (2019). Peran Mahasiswa dalam Gerakan Anti Korupsi. UNES Law Rev. 2, 205–215. doi: 10.31933/unesrev.v2i2.114

Matdio, S. (2019). Dampak Pandemi COVID-19 Terhadap Dunia Pendidikan. J. Kaji. Ilm 1, 1–3. doi: 10.31599/jki.v1i1.265

Megawanti, P., Megawati, E., and Nurkhafifah, S. (2020). Persepsi Peserta Didik Terhadap PJJ pada Masa Pandemi Covid-19. J. Ilm. Pendidik 7, 75–82.

Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania (2006). Anti Corruption Education at School. Kaunas: Garnelis Publishing.

Najih, M., and Wiryani, F. (2021). Perspectives On İntegrating Anti-Corruption Curriculum İn Indonesian Secondary School Education. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 21, 407–424. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2021.93.20

Neo, M., Park, H., Lee, M.-J., Soh, J.-Y., and Oh, J.-Y. (2015). Technology Acceptance of Healthcare E-Learning Modules: a Study of Korean and Malaysian Students’ Perceptions. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 14, 181–194.

Ningsih, S. (2020). Persepsi Mahasiswa Terhadap Pembelajaran daring pada Masa Pandemi Covid-19. INOTEP 7, 124–135. doi: 10.17977/um031v7i22020p124

Owusu-Fordjour, C. K., and Hanson, D. (2020). The Impact of Covid-19on Learning-The Perspective of The Ghanaian Student. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 7, 88–101.

Pamungkas, I. B., Wibowo, W. A., and Juanda, A. (2021). Faktor-faktor yang Mempengaruhi Keaktifan Belajar Mahasiswa Tingkat 1 Program Studi Manajemen Universitas Pamulang. Jurnal Semarak 4, 41–50. doi: 10.32493/smk.v1i1.9347

Patmanthara, S. (2017). Implementasi model pembelajaran berbasis proyek untuk meningkatkan aktivitas dan hasil belajar mahasiswa. TEKNO 26:2.

Schwen, T. M., and Hara, N. (2004). Community of Practice: a Metaphor for Online Design. Inform. Soc. 19, 257–270. doi: 10.1080/01972240309462

Setiani, S. I. (2020). Menakar Peran Mahasiswa dalam Pengawalan dan Pemantauan Bantuan Sosial Guna Mencegah Praktik Korupsi Pada Masa Pandemi. Menelisik Berbagai Hubungan Kebijakan Di Tengah Pandemi Covid 19 Aturan Dan Praktik Dalam Masyarakat 2020:165.

Silvia Mona, P. Y. (2021). Faktor-faktor yang Berhubungan dengan Prestasi Belajar Mahasiswa. Jurnal Penelitian Dan Kajian Ilmiah Menara Ilmu Universitas Muhammadiyah Sumatra Barat XV:02.

Sopacua, F. J., and Sugiharto, M. (2020). Implementation of Character Education Based on Local Ceremony in Nusalaut State Middle School (SMP)2. Jurnal Educational Managemen EM 9, 172–181.

Subkhan, E. (2020). Pendidikan Antikorupsi Perspektif Pedagogi Kritis. INTEGRITAS: Jurnal Antikorupsi 6, 15–30.

Suciani, T., Lasmanawati, E., and Rahmawati, Y. (2018). Pemahaman Model pembelajaran sebagai Kesiapan Praktek Pengalaman Lapangan (PPL) Mahasiswa Program Studi Pendidikan Tata Boga. Media Pendidikan, Gizi Dan Kuliner 7:78.

Sucilestari, R., and Arizona, K. (2018). Pengaruh Project Based Learning pada Matakuliah Elektronika Dasar terhadap Kecakapan Hidup Mahasiswa Prodi Tadris Fisika UIN Mataram. Konstan Jurnal Fisika Dan Pendidikan Fisika 3, 26–35. doi: 10.20414/konstan.v3i1.4

Sumaryati (2014). Implementasi Nilai-nilai Pendidikan Antikorupsi Untuk Mewujudkan Karakter Jupe Mendi Tangse Kebedil (Survey Dalam Proses Pembelajaran Di SMA N 3 Bantul). Yogyakarta: UAD Press.

Sumaryati, S. (2021). Prosiding Seminar Nasional Hasil Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat Universitas Ahmad Dahlan. Pendampingan Penyusunan Perangkat Pembelajaran PPKn Bermuatan Pendidikan Antikorupsi Bagi Guru PPKn SMA Dan SMK Kabupaten Kulon Progo 3, 623–629.

Sumaryati, S., and Hastuti, D. (2019). Pendidikan Anti korupsi di Keluarga, Sekolah, dan Masyarakat. Yogyakarta: UAD Press.

Suyadi. (2019). Millennialization of Islamic Education Based on Neuroscience in the Third Generation University in Yogyakarta Indonesia. QIJIS: Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies 7, 173–202. doi: 10.21043/qijis.v7i1.4922

Suyadi, N., Nuryana, Z., and Sutrisno Baidi. (2022). Academic reform and sustainability of Islamic higher education in Indonesia. Internat. J. Educ. Dev. 89:102534. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102534

Suyadi, S., Hastuti, D., and Saputro, A. D. (2020). Early childhood education teachers’ perception of the integration of anti-corruption education into islamic religious education in Bawean Island Indonesia. Element. Educ. Online 19, 1703–1714. doi: 10.17051/ilkonline.2020.734838

Suyadi, S., Nuryana, Z., and Asmorojati, A. W. (2021). The insertion of anti-corruption education into Islamic education learning based on neuroscience. Internat. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 10, 1417–1425. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v10i4.21881

Suyadi Sutrisno (2018). A Genealogycal Study of Islamic Education Science at The Faculty of Ilmu Tarbiyah dan Keguruan UIN Sunan Kalijaga. J. Islamic Stud. 56, 29–58. doi: 10.14421/ajis.2018.561.29-58

Suyadi Suyadi (2019). Integration of Anti-Corruption Education (PAK) In Islamic Religious Education (PAI) With Neuroscience Approach (Multi-Case Study in Brain Friendly PAUD: I Sleman Kindergarten Yogyakarta). INFERENSI: Jurnal Penelitian Sosial Keagamaan 12, 307–330. doi: 10.18326/INFSL3.V12I2.307-330

Suyadi Suyadi, Sumaryati, S., Hastuti, D., Yusmaliana, D., and Rahmah, M. Z. (2019). Constitutional Piety: The Integration of Anti-Corruption Education into Islamic Religious Learning Based on Neuroscience. J-PAI: Jurnal Pendidikan Agama Islam 2019:8307. doi: 10.18860/jpai.v6i1.8307

Tim Penulis Buku Pendidikan Antikorupsi (2018). Pendidikan Antikorupsi untuk Perguruan Tinggi. Jakarta: Kemenristekdikti.

Tinenti, Y. R. (2018). Model Pembelajaran Berbasis Proyek (PBP) dan Penerapannya dalam Proses Pembelajaran di. Yogyakarta: Deepublish.

Yuliana, C. (2020). Project Based Learning, Model Pembelajaran Bermakna di Masa Pandemi Covid 19. Lampung: LPMP Lampung.

Yusmaliana, D., Widodo, H., and Suryadin, A. (2020). Creative Imagination Base on Neuroscience: a Development and Validation of Teacher ’ s Module in Covid-19 Affected Schools. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 8, 5849–5858. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.082218

Zubaidah, S. (2019). Memberdayakan Keterampilan Abad Ke-21 melalui Pembelajaran Berbasis Proyek. Seminar Nasional Nasional Pendidikan Biologi 2019, 1–19.

Keywords: anti-corruption education, project-based learning, anti-corruption action, COVID-19, citizenship education, PPKn

Citation: Sumaryati, Suyadi, Nuryana Z and Asmorojati AW (2022) Anti-corruption Action: A Project-Based Anti-corruption Education Model During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:907725. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.907725

Received: 30 March 2022; Accepted: 16 May 2022;

Published: 23 June 2022.

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Sumaryati, Suyadi, Nuryana and Asmorojati. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sumaryati, sumaryati@ppkn.uad.ac.id

Sumaryati

Sumaryati Suyadi

Suyadi Zalik Nuryana

Zalik Nuryana Anom Wahyu Asmorojati

Anom Wahyu Asmorojati