Factors Contributing to English as a Foreign Language Learners’ Academic Burnout: An Investigation Through the Lens of Cultural Historical Activity Theory

- 1Faculty of Foreign Languages, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- 2HQT Education Co. Ltd., Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

During the shift from face-to-face to online emergency classes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) were under constant pressure to familiarize themselves with the once-in-many-generations learning context. Based on the cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), this qualitative study investigated factors contributing to EFL learners’ academic burnout at Open University, Vietnam. The interviewees were seven students, two teachers, and two administrators recruited using a theoretical-based sampling technique. The data consisted of iterative rounds of interviews which lasted approximately 60 min each until the data saturation point was reached. The content analysis revealed six factors that impacted EFL learners’ physical and psychological exhaustion, including prolonged online learning time, privacy concerns and cyber-bullying, teachers’ role, institution’s role, and support community outside the classroom. Also, teachers’ insufficient preparation for online teaching and students’ academic misconduct during exams were factors that created EFL learners’ academic cynicism. Finally, participation in social networking sites’ extracurricular activities, participation checking, and cheating in exams affected the last dimension of academic burnout, the sense of academic achievement. Based on this study, the authority, administrators, and teachers can take a more proactive role in supporting students in curbing their academic burnout during this unprecedented pandemic. The authors also hope that this study can lay the foundation for further humanistic research into the EFL learner’s psychological world in online classes, particularly when each student’s social and cultural background is considered.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, North America, and South America have announced or implemented school closures, influencing over 90% of the student population in the world (UNESCO, 2020). In response to this pandemic, many schools and institutions have decided to switch to online teaching and learning to continue their operations. While online learning is by no means new in the digital age and has been opted for by an increasing number of learners, emergency online learning is only an immediate solution for unexpected situations that schools and institutions resort to maintain their operation and the students learning. As a result of the sudden transition, both teachers and students have to try to familiarize themselves with the new learning environment. So far, although research has been conducted on what teachers have done to cope with the challenges of COVID-19 (MacIntyre et al., 2020) and their burnout (Bottiani et al., 2019; Sokal L. et al., 2020), a minimal body of research focus on the burnout syndrome experienced the students, particularly English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners. Because stress and academic burnout can adversely affect students’ academic performance (May et al., 2015), it is crucial to investigate what factors affect learners’ academic burnout in emergency EFL classrooms amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors seek to investigate what factors affect EFL learners’ academic burnout from an ecological perspective within this qualitative study.

The first part of this article aims to contextualize and specify this research’s theoretical and practical contribution to the current EFL education in this once-in-many-generations pandemic. The following part reviews fundamental concepts related to academic burnout, factors contributing to academic burnout investigated by other previous studies, cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), and the CHAT model. Next, the article elaborates on research methodology, data analysis, and research findings before discussing how the research findings support or reject other studies, dominantly quantitative, about academic findings among EFL learners. Within the discussion, the authors also discuss what the authority, administrators, and teachers can do to help curb academic burnout among university EFL students. Finally, the research concludes with a summary of the main points, admits research limitations, and proposes a research direction for further investigation into how to help learners overcome their burnout state.

Literature Review

Burnout

Burnout is originally related to a psychological syndrome associated with workplace settings (Maslach et al., 2001). Besides burnout among professionals, students’ academic burnout has been found in education. Many college students experience the syndrome to a certain degree during their learning process (Balogun et al., 1996; Jacobs and Dodd, 2003). The Maslach Burnout Inventory adopts a three-dimensional model predicting the perceivable symptoms among college students (Schaufeli et al., 2009; Portoghese et al., 2018), which includes exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. Exhaustion is severe fatigue that students experience regardless of the causes (Salanova et al., 2005). Cynicism is students’ indifference toward their academic work. Finally, professional efficacy demonstrates students’ satisfaction toward their accomplishment and their expectations of future development at schools. However, as this study only focuses on EFL rather than subjects related to students’ future profession, the authors would use the term sense of academic achievement instead of professional efficacy.

Factors Contributing to Academic Burnout in Online Emergency English as a Foreign Language Class

Whether e-learning, particularly in emergency classrooms, leads to more burnout among students is still open to question and controversy. In the cross-sectional survey-based research with 619 medical students in the first phase and 798 students in the second phase, Bolatov et al. (2021) reported that students’ mental health improved when transferring from traditionally learning to online learning. However, Bolatov et al.’s (2021) study did not deny the negative changes in learning performance due to depression, anxiety, and dissatisfaction. Indeed, many opposing studies claim that students succumb to new factors of burnout during the pandemic. Mental health stressors such as quarantine time, isolation, and the lack of face-to-face interaction are linked to emotional depression and burnout in the classroom. Additionally, physical issues related to extended exposure to the computer screen, namely eye strain, neck pain, headache, and back pain, are also sources of students’ fatigue and burnout (Mheidly et al., 2020). Researchers even started using the term Zoom fatigue to signify that the abrupt deviation from traditional and fine-tuned face-to-face communication creates physical and mental tensions for learners (Fauville et al., 2021; Peper et al., 2021; Samara and Monzon, 2021). Fauville et al.’s (2021) survey concluded that the respondents were socially, emotionally, visually, and motivationally fatigued due to the inappropriate frequency, duration, and business during Zoom meetings or synchronous digital meetings in general. There are also studies claiming that because teachers and students are not always competent technology users, inadequate digital affordances and technical support should be provided for online learning (Misirli and Ergulec, 2021), otherwise, they will have problems accessing the learning platforms due to Internet connection issues (Khlaif et al., 2021). Also, students’ problems with etiquette and behaviors in online learning settings require attention (Conrad, 2002; Kao, 2020). Although digital issues create academic inhibition, insecurity, and uncertainty among learners (Arroyo et al., 2015; van Rensburg, 2018; Kao, 2020), limited research has been conducted to link these problems with students’ academic burnout, nor have learners been given sufficient opportunities to have their issues listened in official studies.

Undeniably, previous research has contributed to the knowledge of some fundamental causes and repercussions of burnout, but these research articles still have several inherent limitations related to research perspective and methodology. First, studies usually investigate learners in general terms and disconnect them from their social-cultural background. Studies related to human psychology should not separate the participants from their living conditions; otherwise, we can only understand their problem at face value. Some valuable information related to burnout sometimes cannot be obtained through statistics. For example, it is likely that supportive and digitally knowledgeable parents help reduce academic burnout compared to their less supportive counterparts, but how students grade how supportive their parents are on a Likert scale is questionable. Second, other studies have not addressed the role of educators in supporting or exacerbating students’ mental health. Pedagogical approaches, classroom contents, time allocation for teacher talking time, student talking/working time, and the like cannot be overlooked. Third, some research projects only look at students as passive recipients, without agency, proactive adaptation, and adjustment, when they use phrases like “coping” or “academic coping” (Noh et al., 2016; Kim, Kim and Lee, 2017; Mheidly et al., 2020), with which we disagree from an ecological and humanistic perspective.

Regarding the three limitations mentioned, the authors propose that academic burnout should look at students in an ecology that connects them to their academic and non-academic communities, learning tools, and regulations. Each student’s social context should be carefully considered, and students should be active participants who also have the decisive power in their own learning process, no matter whether they engage consciously in burnout prevention or not. What and why students develop their burnout syndrome should be investigated in a social, cultural, physiological, and pedagogical spider web rather than as discrete dimensions. These are justifications to call for the application of the CHAT in academic burnout studies.

The Cultural Historical Activity Theory

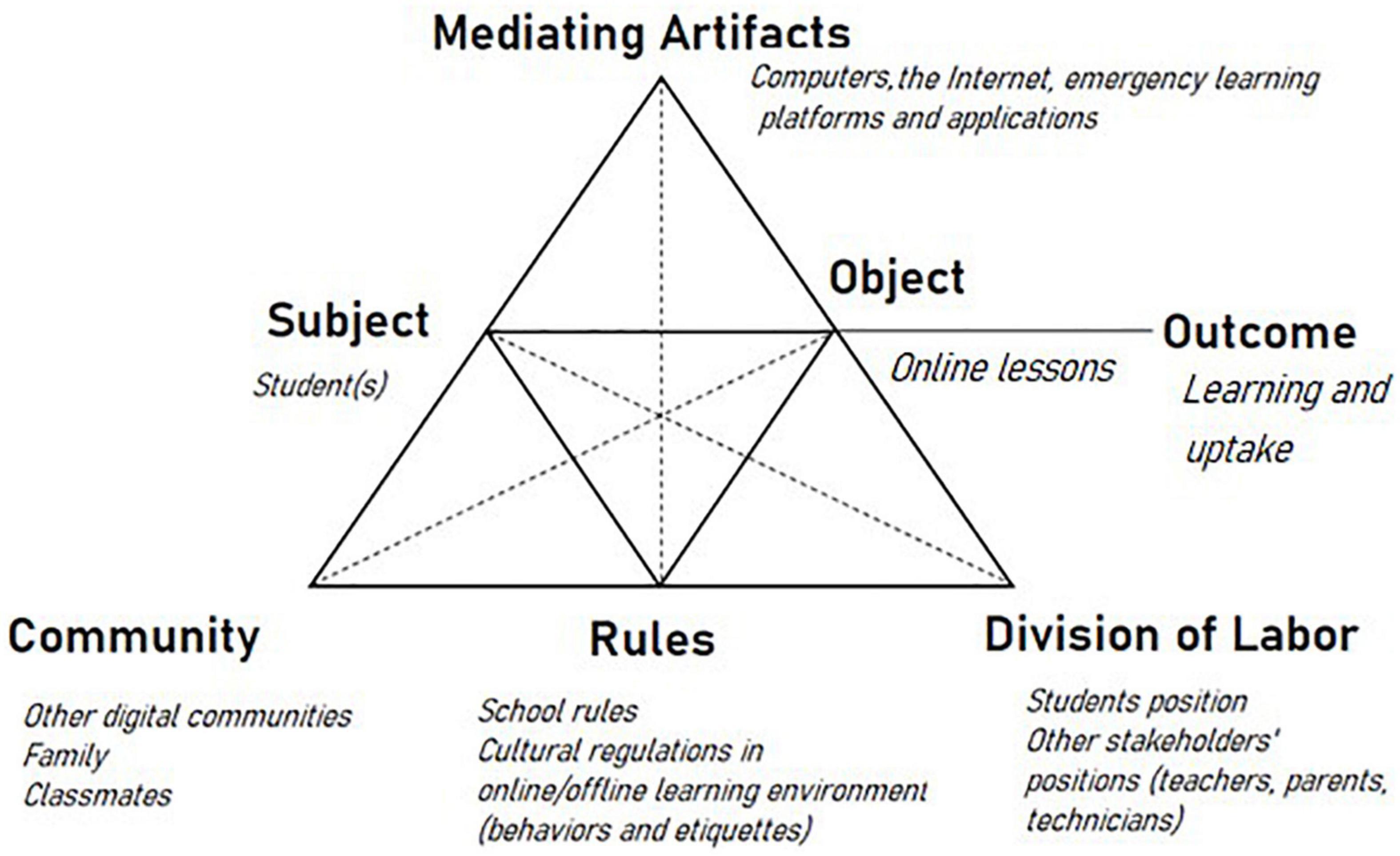

Human activities should not be investigated from the sociocultural perspective as a simple relationship between actors and objects because humans are dependent on society (Stetsenko and Arievitch, 2004). According to the sociocultural theory of cognitive development, human activity is mediated by historical and social artifacts such as signs, tools, and instruments. Leontiev (1978) further added that an objectless activity is devoid of any meaning, which in turn contributes to formulating the CHAT, also known as Activity Theory (AT), as an object-related theory (Engeström and Sannino, 2010). The goal of CHAT is to explore the constantly changing and increasingly complicated exchange that constitutes the existence of all organisms (Stetsenko and Arievitch, 2004). Acknowledging the interim between human activities and society to avoid reductionist ontology, this article adopts the CHAT framework by Engeström (1987), which allows insights into how societal components can mediate teaching and learning through both tangible and intangible factors. Within this framework, Engeström (1987) suggested six components contributing to human activity: subject, object, mediating artifacts, community, rules, divisions of labor, and outcome (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of students’ activities in the online emergency classroom [adapted from Engeström (1987)].

A subject is an individual or group of people whose burnout state is the focus of this analysis. On the other hand, in an online emergency classroom, the objects are online lessons conducted synchronously and asynchronously to facilitate the learning and uptake of knowledge. The student’s learning activity is enabled and mediated by external artifacts and internal tools. The devices and tools applied in an online emergency classroom are computers, the Internet, learning platforms (both synchronous and asynchronous), and learning applications, which, in semiotic cooperation budget, the learner can acquire their knowledge. Besides, rules regulate the learning process as learners interact with their academic communities, families, and other non-academic digital and real-life social networks. Initially, the community shares the same object with the students, such as instructors and classmates. However, communities also extend to the cultures and experiences with others throughout learners’ developmental processes. When interacting with the students’ learning activities, different stakeholders, such as teachers or administrators, also share the division of power and status called the division of labor. The understanding of the division of labor necessitates the investigation of social roles and identities. In a classroom, the division of labor can also be considered the division of symbolic labor, where the identities of different stakeholders are embedded in different discourses (Thorne, 2000).

It is worth notetaking that there are reciprocal impacts among the constituents of the whole activity model. In the middle of perennial shutdowns and lockouts, learners, staying with their family, are tied to a significantly wide diversity of learning contexts, responsibilities, communications, and interactions. This large and unpredictable social-cultural spectrum makes any attempts to generalize learners ineffective and futile. With a humanistic and ecological viewpoint, we hoped to investigate each learner as a unique individual that was subject to different adversities, listen to their stories of how they were struggling every day, and share with the readers their constant efforts to sustain their education despite their limited resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on this framework, this article aims to investigate:

What factors influenced the EFL learners’ academic burnout while learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic?

To fully answer this question, the research group will examine three sub-questions about factors influencing different dimensions of academic burnout, as follows:

What factors influenced EFL learners’ exhaustions while learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What factors influenced EFL learners’ academic cynicism while learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What factors influenced EFL learners’ sense of academic achievement while learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods and Research Designs

Research Design

This study employed the qualitative research method from the pragmatic ontology and ecological epistemology. The pragmatic ontology prioritizes mixed exploratory methods that the researchers deem the most effective rather than relying solely and rigidly on a method or a philosophy that tries to capture absolute truth (Frey, 2018). In terms of epistemology, the authors hold an ecological worldview that focuses on a situated and contextualized ecocentric understanding of knowledge to minimize context, data, and complexity reduction of complicated and sophisticated social activities (van Lier, 2004).

The authors believed it was optimal to utilize the qualitative research design of this study with a multiple case study approach within the cultural historical activity framework. The multiple case study allowed researchers to comprehend better and theorize the prominent phenomenon (Brantlinger et al., 2005). Also, the multiple case study with the cultural historical activity theoretical framework focused on the non-idiosyncratic voices of different participants suffering from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sampling Techniques and Participant Recruitment

The researchers chose to apply theoretical-based sampling because this sampling technique involves selecting essential manifestations of the phenomenon of interest or the real-world cases of the research constructs (Suri, 2011). In the first round of participant recruitment, the researchers chose students of different social backgrounds so that the participants with different social backgrounds could voice their issues. As learning should be humanistic and differentiated, different learners with different backgrounds may have different reasons for their burnout state. Thus, it is of paramount importance for humanistic researchers to unbiasedly empower those of different social statuses and backgrounds rather than biasedly prioritizing or generalizing the learners’ contexts. The interviews were conducted in the participants’ mother tongue which is also the native language of the researchers who are Vietnamese teachers of English. However, as the finalized manuscript was written in English, two authors and a professional translator independently translated the transcript to avoid back-translation’s drawbacks (Behr, 2017). The translated transcript then was compared and the translation group would discuss with each other to address any discrepancies. The translation was finally reviewed by the corresponding and lead author to make sure that misinterpretation is minimal. After the first recruitment round, constant comparisons were made between the students’ responses as the researchers continued to hypothesize the stakeholders representing each chain of the CHAT framework and identified significant theoretical constructs that emerged. In the second recruitment round, the researchers could choose more participants such as teachers and technical administrators to represent the new theoretical constructs and provide more multilateral information about the students’ burnout state. The language of communication was the local language shared by the participants and the researchers. To reach data saturation and sufficiency, at which point all additional data emerged had been explored and exhausted, the researchers prioritized the sample adequacy over sample size (Bowen, 2008).

A Description of the Participants

In the first interview round, student A was a female sophomore from another province. As a former COVID-19 patient, she spent about 40 days in hospital in Ho Chi Minh City (HCM City, hereafter). She had difficulty studying in bed in the slow Wi-Fi that she shared with many other patients during the treatment. Upon being released from the hospital, she returned to her rented place in HCM City. She studied in the room, which was also the workplace of her uncle.

Student B was a male sophomore who was well-supported by his family. He had a private room, a high-speed Internet connection, and his own laptop. He reported that he felt comfortable but not as disciplined as in school while learning offline at home. Sometimes, he was interrupted by some emergent chores while his family was not around.

Student C was a female freshman student. At the time of the interview, as regulated by the government, she stayed in a quarantine zone in her hometown after leaving HCM City. Since she did not bring her laptop with her, she had to study with her mobile phone the whole time. Student C had to suffer such inconveniences as low Wi-Fi signal, no necessary furniture, or no private space while in quarantine.

Student D was a male freshman who has just returned from the hospital after 3 weeks of COVID-19 treatment. As a student from another province, he shared one room with another friend while in HCM City. The student did not have financial difficulty or health problems.

Student E was a female freshman. She insisted that it was the students’ responsibility to make an effort in their studies. When the pandemic started the second time, she returned home to the mountainous region. She had her laptop and a study room with a Wi-Fi signal. The Internet connection in her hometown was not always stable, and sometimes her laptop did not work properly.

Student F, a female freshman from a province far from school, studied with mobile phones and laptops. For the first few weeks of the semester, she stayed in HCM City, sharing a room with another friend. Her first problem was that she could not sign into the MS Team. Student F had reported the problem to the school, but it could not be fixed. Therefore, she could not attend the classes. She had no choice but to review the lessons, use the recorded videos and slides the lecturer posted on the Learning Management System (LMS) after each session, and submit the given assignments to the system.

Student G, a female sophomore, lived with her family in HCM City. She had to study in the living room where she sometimes was inevitably unintentionally distracted by the family members or her pet. She said her language teacher had created a Zalo group to increase interaction with her class members, check and remind students to work.

In the second interview round, the authors invited two teachers A and B, who were teaching in the EFL courses and two administrators who were running the emergency online EFL program. However, upon the participants’ request, detailed descriptions of the teachers and the administrators are kept confidential.

Interview

The first set of interview questions for the students included 15 questions revolved around the ideas about how other parts of the CHAT framework, for example, the school regulation or the teachers, affected their burnout state. The first five questions inquired about the students’ background, while question four investigated students’ academic anxiety resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. From questions five to seven, the students were asked about their experience with their university, including technical, administrative, and psychological aspects, and the following five questions asked students to talk about their teachers and friends. The last three questions investigated how family and personal factors might affect their burnout. The second question set for teachers and school administrators consisted of six questions about their observation regarding students’ burnout and psychological factors, school support, and students’ supervision. As King and Horrocks (2010) suggest, the interviews started with fundamental and less complicated research questions before progressing to more advanced research questions. Additionally, several questions included a probe and prompt feature to assess interviewees’ understanding and prompt the interviewees to clarify themselves (Jacob and Furgerson, 2015). As the interview was semi-structured, the author conducted progressive refinement of questions after synthesizing and analyzing each interview recorded to accelerate the data saturation and sufficiency (Suri, 2011).

Procedures

After getting the university’s consent, the researchers sent out the participant recruitment document and asked for references from the university lecturers about who could be the potential participants for the study. After identifying the participants, the researchers informed them about the research aims, purposes, procedures, benefits, and risks, and asked for their consent to participate anonymously in the research. The interviewers set up one-hour interviews using online conference software (Zoom and Google Meets) when the participants agreed to join due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the interview, the interviewers had discussed the meaning of burnout and academic with participants to reach a mutual understanding of the term used in the interview. Each interview was recorded, transcribed, and closely examined. The data collection and data analysis were iterative, as the data analysis with students oriented how to choose more interviewees and how questions should be refined and adjusted for the following interview. The authors discussed and finalized the main themes in several meetings to ensure no critical theme was left out and sent them to the participant for their reconfirmation. This stage was repeated until all the participants agreed that no critical idea was missing from the research.

Data Analysis

The researchers used content analysis techniques with word frequencies and auto-coding tools provided by Nvivo 24. The submerging constructs gathered from the students’ interviews were then used to identify more potential stakeholders such as the teachers and administrators. The data collected from the teachers and the management about their perceptions of how burnout the students were then analyzed to find more emerging themes and triangulate the students’ answers. The code analysis was a combination of inductive and deductive coding based on the overarching areas of investigation in the CHAT model.

Findings

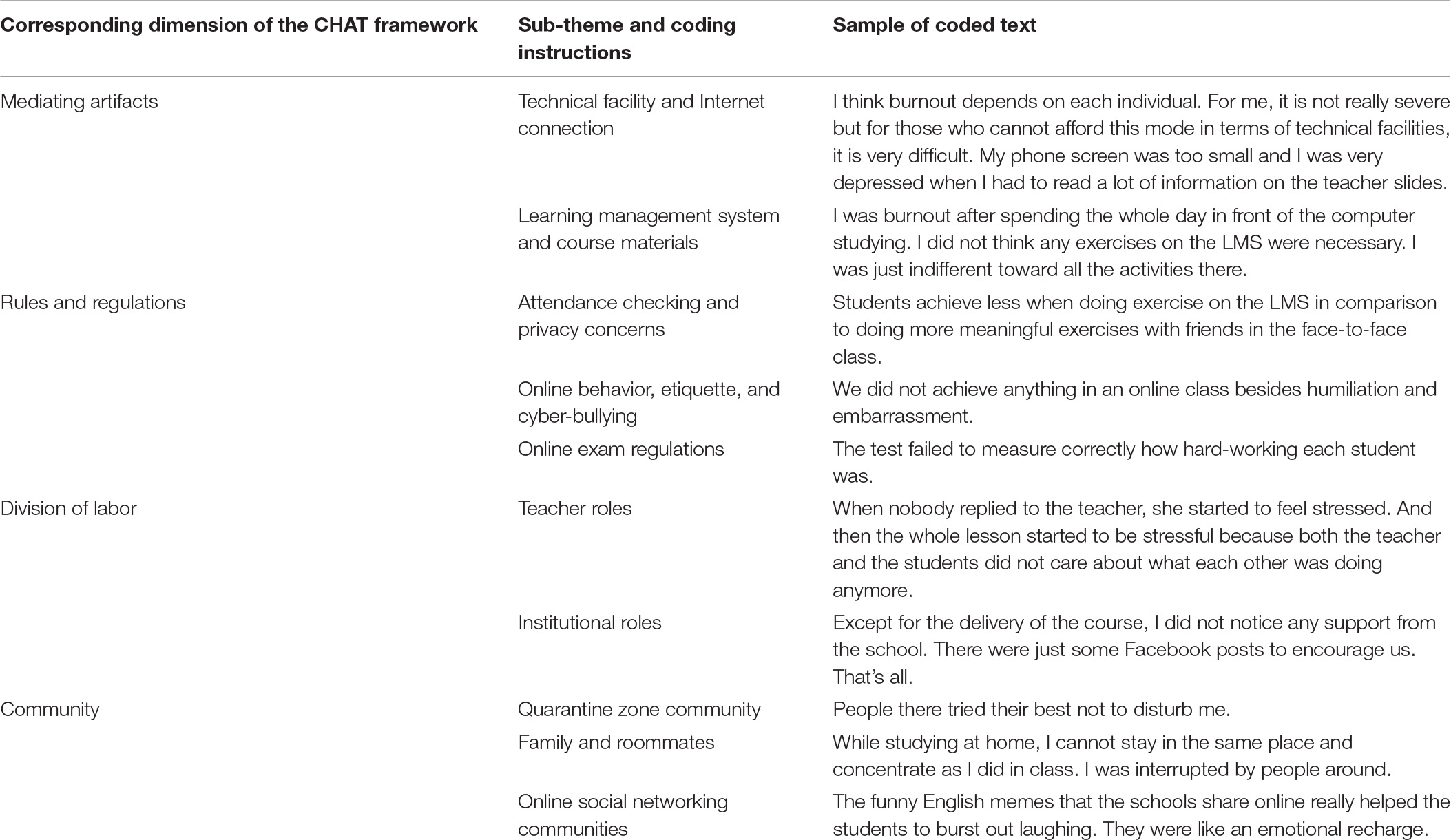

Based on the CHAT framework, the interviews revealed four main areas that directly affected EFL students’ academic burnout, including only 4 areas (see Appendix Table 1).

Mediating Artifacts

Technical Facility and Internet Connection

The first factor of mediating artifacts is technology facilities such as Internet connections, computers, laptops, and smartphones. While students who lived at home or their rented rooms in Ho Chi Minh City did not have too much difficulty connecting to the synchronous classes, the instability in Internet connection was one factor that distressed the students who were staying in their hometown in the countryside or the quarantine area. The students who lived in the cities also had technical problems at peak hours when other members were also using the Internet: “I sometimes felt annoyed when my brother turned on his phone and played video games, because my Zoom account started to log out again and again” (student G). The students also reported that they are highly anxious when looking at other people having technical problems during the listening exam time: “It was not my case, but it was my friend. She lost her Internet connection during the listening test. She cannot hear anything at all, and she failed the test” (student F). Thus, although the students who lived at home or at their rental apartment in the city did not directly admit that technology was one contributor to academic burnout, they still reported feeling “distressed,” “annoyed,” or “anxious” at times due to factors related to the Internet connection.

On the other hand, students who were in the quarantine zones or live in the countryside reported severe burnout due to the low-quality technical facility and Internet connection. Student A shared that “The Internet is not stable and the signal is weak, so this is the most stressful time in my life!… I studied on my bed with only my phone and it always got overheated. It was not until I took the test that I had a laptop sent in my friend.” Likewise, student C said that “My quarantine zone had low-quality facilities. I had to use 4G to study six to seven hours continuously. My phone screen was too small and I was very depressed when I had to read a lot of information in the teacher slides. I could not do the reading practice as well because the text was illegible.” Similarly, student E who was living in the highland, said that “I feel much more emotionally drained and physically exhausted dealing with the faulty phone and unstable Internet connection. There is no technician to support me here.” “Sometimes, I just wanted to give up. I don’t care whether I can enter the session or not. It is just like it does not matter anymore.” All the participants agreed that the limitations of technical families exhausted them both physically and mentally, which in turn led to their academic burnout.

The teachers and school administrators were also aware of and sympathetic toward the students’ insufficient technical conditions for online learning, leading to their academic burnout. Teacher A shared that “More than 20% of the students in my class did not have favorable conditions regarding facilities, the Internet, and the environment. I think this made them physically and psychologically exhausted. They seem burned out all time.” Likewise, teacher B also agreed that “My students told me that sometimes they did not want to study the Internet in their areas was in bad quality.” The administrators agreed that facilities were of utmost importance for online learning. According to administrator B, not all students in Vietnam had a laptop, and it was inconvenient to study by phone. Manager A added that “It is up to each student’s conditions in terms of facilities. Online learning can only succeed with the optimal technical facility of the institution, teachers, and students.”

Learning Management System and Online Conference Applications

Regarding the school’s system, the students reported that classrooms were built on a Learning Management System (LMS) where the teachers posted the link to their virtual classes and the link to the recorded video of each lesson. The materials, the presentation slides, and assignments were also uploaded there. However, the students sometimes found the system unnecessary. Student D questioned the practicality of the content of the activities on the LMS, saying that “the activities on the LMS system just harshly copy all the activities in the course book that we learn in our face-to-face class. Although our school is very reputable, the LMS system cannot meet my expectations at all.” The case was also true for student B when she said that “I was burnout after spending the whole day in front of the computer studying. I was just indifferent toward all the activities there [on the LMS]. I wouldn’t have done them if the teacher had not forced us to.” Students even felt more burnout when there were technical problems with the LMS. Student A said that she was afraid of “achieving nothing and losing her scores” when the LMS was like to “crash whenever it likes” when student D felt that she could “achieve less in comparison to doing more meaningful exercises with friends in the face-to-face class.” Both teachers A and B agreed that one factor of “great concern” was the frequent crash of the LMS system. According to teacher B, “The school LMS has gone down often. They seem very stressed having to seek technical support regularly.”

In addition to the LMS system, the online conference platforms also contributed to the students’ burnout in the EFL online classes. Student F said that at the beginning of the course, she spent hours in vain trying to log into the synchronous sessions with Microsoft Team, and at the end, she just felt like “quitting,” thinking that “I should have taken a nap instead.” Students A and B thought that online learning during the pandemic was more “demonstrative than really effective” because after the students had to spend an extended period trying only to log into the system “just to find that the class has ended before we are in,” they tended to “skip other courses because they are all the same. It [the MS Teams application] is slow and often gets lagged. It is time-consuming and fruitless.”

Rules and Regulations

Prolonged Online Learning Schedule

The fact that the university transferred the entire face-to-face class schedule into an online class schedule dramatically enhanced the students’ exposure to the computer screen, high burnout level, and particular mental, physical, and psychological fatigue. Student B complained that staring at the phone screen continuously caused eyestrains because the learning schedule assigned by the university was not “sensible,” and thus, there were some days that he had to work on the phone “for at least 12 hours continuously.” Likewise, all six students reported having migraine or headaches at least once a week due to the prolonged exposure to the blue light emitted by the monitor screen or their phone screen. Also, student G reported that she had a light backache every day after class while student G said that he “felt like an old woman who cannot concentrate on anything after spending ten hours studying in front of the computer,” or even become forgetful when she has to study for the online exams.

Attendance Checking and Privacy Concerns

In addition to the regulations about study time, students also showed negative attitudes toward the in-class requirement established by the teacher per se. While some teachers allowed students to turn on webcam and microphone when necessary only, other teachers forced the students to keep their webcams and microphones on “24/24” (student B), which heightened their “embarrassment,” “discomfort,” “annoyance,” or even “depression” among the students as complained by five out of seven students. Student A revealed her situation during the time as a communal quarantine zone, stating that “I did not dare to use [my] webcam and mic because I felt embarrassed speaking English with many people around.” More noticeably, student D believed that teachers “have no right to intrude [his] privacy, as I am over 18 years old and no one should force me to reveal my personal space.” In the same vein, student G believed that turning on the webcam during the whole session “disturbs the whole family” because without a study room, she had to study in the living room where everyone usually had quality time together and now “they have to give up on doing things with each other and retreat into their rooms.”

The regulations also caused misunderstandings or even conflicts. Student A reported that “I can’t understand why my teachers keep doing the roll call twice or even three times in one learning session. It made me exhausted, I always felt tensed because I didn’t know when he would call on me.” When student D lost the Internet connection and turned off webcam, the lecturer reduced his attendance score without listening to his explanation. Student D lost all of his study interest right after that incident, saying that “He was not listening. I do not think studying should be such a torture.” Likewise, student F confirmed that “I could not attend the lessons [due to the account problem], so I lost the chance to gain bonuses for participation. I was worried that my score would be low this semester.”

Online Behavior, Etiquette, and Cyber-Bullying

Also, there was a severe lack of codes of conduct and online learning etiquettes because the students were unprepared for the sudden transformation to online learning. Thus, students at times did not know how to behave in the classroom appropriately. Student E said that she “burst out into tears” when she heard one male student in the class comment about her appearance in a highly hostile and insulting manner as he forgot to turn off his microphone. Student G also shared that cyberbullying sometimes existed in the online classroom as two male students kept on laughing at her teammate’s pronunciation when they were presenting. Student G said that her friend “turned off the Google Meets right after the presentation” because that student felt she “cannot achieve anything in an online class besides humiliation and embarrassment.” Student A also shared that she wanted to withdraw in the middle of the course because she “could not study well,” and the online class was “different from speaking up in offline classes because everyone was very attentive to my voice. People will hear and recognize our mistakes. Other students even recorded our voice and mimicked us to poke fun at our accent.”

Online Exam Regulations

One of the factors causing students burnout with online learning in the ELT classes was the regulations related to testing and examinations. As the exams took place online, the students believed that the regulations were not strict enough to prevent cheating, which was unfair for the students who worked hard. Student B said that he lost his sense of personal achievement, a dimension of academic burnout because he knew that many students cheated in the test. According to student B, the school could not monitor the students in the online exam, and many students “secretly contact each other on Telegram or Zalo to share the answer key.” Student B believed that the test “failed to measure correctly how hard-working each student was” and it was not “worth our efforts.” Also, students D and E believed that as students in the different classes had different exam content, it was unfair for them because “some test packages were easier than others,” which made them think that “learning doesn’t matter much; it is your good luck that matter.” Also, as most of the tests were in the form of multiple choice quizzes, student D wondered if they could test their language competence. He added that “I don’t think the multiple-choice questions are necessary for our future work. What we need is how to use English in real life, not only ticking the correct grammar point and lexical items.”

Division of Labor

Teacher Roles

Interviews with the students revealed that teachers played an essential role in helping students overcome their burnout state. Students A, B, and C believed that teachers were very “caring,” “thoughtful,” and “considerate” during the online EFL courses. “The teachers always reminded the students about the links to the synchronous sessions before each lesson” said student A. According to student B, the teachers also usually spent time asking about the students’ family and health and encouraged them to “think positively” and overcome the COVID-19 together, particularly for those infected with the Coronavirus. Also, student B believed that she could communicate with teachers more easily when studying online because she could “text what we think” while she would feel shy when talking to the teacher face-to-face. Thanks to the teachers’ efforts, students were “more excited” and “less alone” during shutdowns and lockdowns (student C). Teachers were also very understanding toward the student objective issues, for example, when they were called out for a community-based Coronavirus test and had to quit zoom sessions (student F). This aligns with what teachers B and C shared as they thought their instruction was very “clear, detailed, and supportive.” Teacher C even reminded the students to go to the correct link before every lesson and “posted the materials students requested… Students who did not attend any classes might go [to the LMS] to download materials.”

However, sometimes students reported a change in the division of labor from the teachers’ side that heightened the students’ academic burnout. “It seemed like the teacher did not run their lesson as smoothly as they usually did in the offline class, and thus, we felt a little disheartened to come to class,” student D and student C stated. Most teachers were not well prepared enough to teach online EFL classes in such an emergency as the COVID-19 pandemic. Teacher A confirmed that they “tried best” to transfer the “leftovers” of the face-to-face program to the online EFL class. However, both teachers A and B said that all university teachers had only taught the offline class before the pandemic broke out. “Without adequate training of how to teach with technology tools and applications, we realized that some students lost their interest in coming to class.”

Students B, E, F, and G agreed that teacher talking time in a lesson increased tremendously in the online classroom as “sometimes the teacher asked but no one replied.” Also, as some teachers might feel ignored by the students, they were inclined to feel disrespected and become emotionalist with their teaching. Consequently, the class becomes a “cold war” (student D). Student C said that “when nobody replied to the teacher, she started to feel stressed. And then the whole lesson started to be stressful because both the teacher and the students did not care about what each other was doing anymore.” One teacher complained that “some students just copied and pasted when I raised the questions. They did not realize they had to communicate to improve their English.” Another teacher added that “some students went online searching for the answers. They did not even bother to think and speak. I couldn’t force them to speak in the online class which is opposite in the offline sessions.”

Institutional Roles

While all students in the interview believed that the university provided students with fundamental administrative support ranging from the learning regulations, coursebooks, and examination guidelines, the school administrative process was slower than students expected. “It is hard for me to contact the school administrative in case of emergencies since it takes one to two weeks for them to reply to our email.” (student A). Some students became more mentally exhausted when they had to when through bureaucratic procedures to fix their online account problem, but after all, the problem was still not fixed (student F).

Furthermore, students think that the school did not take a proactive role in helping students in solving emotional problems, especially when they feel burned out. Student A reported that “Except for the delivery of the course, I did not notice any support from the school. There were just some Facebook posts to encourage us. That is all.” Student D said that “It is different in our country than in other countries. Psychologists and consultants are not popular in university. I wish we had this form of support here as they do in Western countries.” In contrast, administrator B insisted that “the school had psychological consulting service,” although few students knew of this service. She added that “I think the school should require the teachers to inform the students and remind them to turn to the school consultant frequently to reduce their burnout rather than keep the tension to themselves.” She also suggested that “online consultant can be incorporated to the LMS system, so that students may quickly access the service in times of crisis.”

Community

Family and Roommates

Similarly, although all three students who studied from home reported some level of distractions, such as, presence of other family members, unavoidable household chores, and their pets (student G), the students did not feel that these factors heightened their academic burnout. Student B reported: “While studying at home, I cannot stay at the same place and concentrate as I did in class. I was interrupted by people around.” However, when she explicitly expressed her annoyance, her family became more attentive to her study time and did not disturb her anymore. In fact, all students who had to study online while living with family highly appreciated the family’s role in alleviating burnout and stress through encouragement and caring actions (student G and student B). As regards students who were living in a rental room with the friends, they also received words encouragement and established mutual understanding. Because they were all “students,” they “sympathize[d] with each other” and were “supportive of each other.” Likewise, in the quarantine zone, although other roommates and medical staff “got in and out frequently,” they understand that she was studying and “tried their best not to disturb me” (student A). The students did not think that the community at the quarantine zone increased her academic burnout. In contrast, the roommates were understanding and respected their study time.

Online Social Networking Communities

As all the extracurricular activities were not allowed to take place offline, all students’ social calendar was changed into online activities with the online groups on Facebook, Twitter, and Zalo. The online social networking groups both positively and negatively impacted learners’ burnout levels. First of all, there were many online competitions and social campaigns conducted by the youth association of the university, which helped the student to “de-isolate and improve English” (student D). Student D thought that “the funny English memes that the schools share online really helped the students to burst out laughing. They were like an emotional recharge.” After attending the online mini-games and competitions hosted by the schools, student G felt an improvement of English, and thus “a burst of adrenaline” and “a heightened sense of self achievement.” She believed that “What the teachers taught me was not useless at all.” These online social networking sites were indeed an aspect of life with which the students could release their stress, feel more connected, treasure their self-achievement, and minimize their burnout level.

However, social networking sites also had adverse effects on students learning and increased their burnout state. First, spending too much time on social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter, or TikTok also contributed to the physical exhaustion of the students. Student B said that “I didn’t need to be punctual, so I can stay up until 2 a.m. chatting and playing online games with my friends. I could just sign in, and after that I could have my breakfast. Without the teacher’s observation, sometimes I slept during the lesson because I was too tired.” Although student B “didn’t feel burnout at first,” as the course passed by he felt “a little physically exhausted” and became more “absorbed in surfing Facebook and Instagram” and “learning English didn’t matter much because the teacher couldn’t know what we were doing.” Student C was also burned out due to some conflicts with his friends on social networking sites which influenced his learning performance. Administrator A added that “If a course was appropriately organized and the students were self-disciplined, there would be no problems. However, without the students’ self-discipline, the learning process cannot take place regardless of how well-prepared the teachers and the university are.”

Discussion

Factors Influencing English as a Foreign Language Learners’ Physical and Psychological Exhaustion

First, regulations about prolonged online learning time created physical and mental fatigue among the participants. While the school had to transfer from face-to-face class to online learning and teaching, there was no modification in the schools’ bell routine that required the students to be in class for an extended period. Although a previous study by Turchi et al. (2020) concludes that teachers may have problems maintaining consistency in time allotments when the school does not apply the bell schedule to the online class, our finding signifies that transferring an entire offline school schedule to online mode of learning and teaching exhausted students mentally and physically. The fact that students had to spend approximately 10–12 h studying in front of their smart devices is worrying as it can trigger numerous health issues, which is supported by Fauville et al. (2021). Common health-related problems like headaches, migraine, backache, or shortened attention span are symptoms of digital fatigue, contributing to heightened stress and burnout among adolescents. This finding is in line with other studies about the effects of smart devices on physical and mental wellbeing (Lemola et al., 2015; Mheidly et al., 2020). The administrators and educators need to acknowledge this inherent problem related to prolonged exposure to the computer screen and implement possible measures to help students prevent academic exhaustion. On a macro-scale, the authority should implement guidelines for the number of sessions and duration of online classes that are based on scientific research in education, psychology, and digital wellbeing. While many countries, for example, India (Department of School Education and Literacy, 2020) or Vietnam (Ministry of Education and Training, 2021), have issued guidelines and laws to regulate online learning time amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, most of these documents focused on primary school to high school students. The government and the tertiary educational institute need to join hands and examine the optimal learning times for the undergraduates. On an institutional scale, the university can allow students to choose their study time according to their own needs (Turchi et al., 2020; Tafazoli and Atefi Boroujeni, 2021) or introduce longer intervals between synchronous sessions where students can conduct healthy practices like a breathing exercise (Mheidly et al., 2020).

Also, privacy concerns and cyberbullying contributed to EFL learners’ psychological exhaustion. The fact that students had to turn on their webcam as proof of attendance puts them under constant threat of privacy intrusion and cyberbullying. The findings in this study testify of the adverse effects of the webcam and microphone on students’ psychological variables, notably resulting in their psychological exhaustion. Our findings partially align with Maimaiti et al. (2021), stating that turning on the camera creates peer pressure. However, while the research by Maimaiti et al. (2021) concludes that webcam is essential for students to concentrate, our findings show that without a well-established common code of conduct and mutual understanding of online learning cultures, webcam and microphone are detrimental to the EFL learners’ emotion and mental health. The fear of losing face and being ridiculed on the grounds of internal factors, such as accent, appearance, and linguistic competence, or external factors, such as the conversations between family members and family financial background, should not be neglected. The ethical question here lies in how to create an effective learning and teaching environment and a secure place so that no students are afraid of being harmed in cyber space, as insecurity, indeed, is perceived by the students as a fundamental factor causing high academic burnout levels. Therefore, schools and teachers must introduce a code of conduct in online learning and mechanical and technical measures from the university’s technicians to protect the student the students are learning online.

In addition, the division of labor by teachers and the university also affects learners’ exhaustion. During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers took a proactive role in supporting students by asking about their health or encouraging them to think positively. Also, when learning, the students found that they could communicate with the teacher without shyness thanks to texting applications, which also open up more opportunities for them to seek emotional support. These findings elucidate the mechanism of how affective support can inhibit burnout among EFL students. This study confirms the study with 306 EFL Italian learners by Karimi and Fallah (2021), which explains the negative correlation between affective support from teachers and ELF learners’ academic burnout through structural equation modeling. Unfortunately, not all teachers were perceived as supportive in our research. As teachers were also likely to feel burnout in the COVID-19 pandemic (Sokal L. J. et al., 2020; Pressley, 2021), they might redirect their distress toward the students. The fact that students were not communicative in online classes might also put more pressure on the teacher, which enhanced their professional burnout. Some teachers resorted to silent treatment instead of choosing different strategies to support the students. According to Yoon and Kerber (2003), the silent treatment is a form of bullying that is detrimental to the victims. The use of silent treatment in online classrooms can exacerbate both sides’ burnout state. The teachers should consider other approaches to enhance the learners’ communication. Also, as some EFL learners are not proficient enough to explain themselves and their English issues, code-switching should be allowed in the classroom.

The university’s delays in helping students solve their problems was also a factor that worsened the student burnout states. While there is still a limited body of studies connecting the lengthy administrative procedures from the school to the academic burnout, it is possible that as students could only contact the schools via phones or emails during the COVID-19 pandemic, the waiting time might create more anxiety as they could get into a class or might not be able to enter the test room timely. Also, while the school administrators insisted that psychology consulting services were available for students, most of the students did not know of this source of support. One student thought that this service was only available in developed countries or Western countries. The students’ unawareness of the school psychologists calls for a more proactive role from the school to inform students of the support network that they are entitled to so that the students can adopt a more holistic approach to coping with stress and academic burnout.

The content analysis also reveals that communities, including family and friends, quarantine zone, and social networking also affected EFL learners’ exhaustion. Understanding parents, roommates, or the community at the quarantine zones are the support network that EFL learners can depend on when they feel exhausted. Although there is limited research into the effect of support from friends, parents, and other communities on academic burnout, Kim et al. (2018) and Renk and Smith (2007) suggest that support by others can reduce students’ academic-related stress. In addition, social networking communities have a double-edged effect on students’ academic burnout. Students in our study perceived the moderate use of social networking sites as a place to deisolate and provide them with an emotional recharge as all extracurricular and social activities had been transferred to the online environment. Our findings are in line with Wang et al. (2014), in which 377 undergraduates from universities in Southwestern China participated in a survey to examine the relationship between social networking sites and their wellbeing. According to Wang et al. (2014), social networking sites’ communication function positively correlates with students’ subjective wellbeing. On the other hand, the participants in our study also reported that the excessive use of social networking platforms, especially overnight, created fatigue in class the next day, thus enhancing their burnout level. As many medical and psychology studies into the use of smart devices in bed also report that using smartphones before sleep decreases both happiness and wellbeing (Hughes and Burke, 2018; Alonzo et al., 2021), our study adds that the overuse of smartphones can create student exhaustion and increase their academic burnout.

Factors Influencing English as a Foreign Language Learners’ Academic Cynicism

Teachers’ insufficient preparation for online teaching was one factor that affected EFL learners’ academic cynicism. In fact, the under-preparedness of teachers to conduct online teaching has been recorded both before and during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Stockwell and Reinders, 2019; Rapanta et al., 2020; Pressley, 2021). However, previous studies have not examined how teacher unpreparedness can affect student burnout. Therefore, the findings in this study added that, from the student perspective, the fact that teachers were not well-prepared enough to teach online might create academic cynicism among students. Students did not perceive that teachers are well-qualified enough to teach online, so they were discouraged from joining the online class. Although teacher preparation is paramount for student academic achievement (Boyd et al., 2009), the outbreak of COVID-19 and the forced shift to online teaching are creating a false sense of unpreparedness which creates a feeling that we are strange to the use of technology in teaching and learning (Harouni, 2021). However, the question is whether teachers can only perform thanks to training, planning, and preparation effectively. Rather than always feeling unprepared and losing confidence in teaching, which can lead to cynicism of both teachers and students, teachers should remind themselves that teaching and learning have always contained uncertainties and unpreparedness. Admittedly, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, many teachers and students had been used to computers, smartphones, and social networking sites. Thus, what is making the teachers unprepared may not be the digital tools but rather their mindset. Therefore, besides providing teachers with training, institutions should help teachers recognize that they “have learned [how to teach] without feeling prepared” (Harouni, 2021, p. 4). By overcoming their unconfidence regarding the desire to be constantly prepared, teachers can reflect on what they know about pedagogy in general and improvise in the new learning and teaching context. This radical idea of pedagogy may help teachers feel ready to emerge in the digital world and thus reduce learners’ cynicism.

Studies have proven a relationship between burnout and cheating. Students with high academic burnout tend to cheat more in exams (Kusnoor and Falik, 2013). Specifically, academic cynicism, a factor of academic burnout, positively correlates with cheating in the academic environment (Ameen et al., 1996; Ugwu et al., 2013; Nasu and Afonso, 2020). However, within this study, not only was cheating a sign of academic burnout inside the cheater per se, it also affected other students. As it was too easy to cheat in an online exam, students would develop their academic cynicism, believing that putting efforts into authentic learning was not as conducting misdeeds to achieve high scores. It is important to implement both a high-tech cheating detector system and low-cost measures to prevent this malpractice to become a pandemic that spread the cynicism virus to all students in the online class. The school can make more investment in software, such as eye-tracking, screen monitoring, or other web-based anti-cheating systems. The school must disseminate the code of academic integrity among students that includes the online learning environment. Also, penalty for cheating should be high enough to prevent reoccurrence (D’Souza and Siegfeldt, 2017).

Factors Influencing English as a Foreign Language Learners’ Sense of Academic Achievement

The first factor that positively influenced EFL learners’ sense of achievement was their active participation in extra curricular activities on social networking sites. With online activities and competitions on Facebook or Twitter, students could use their English in real-life rather than outside the classroom. As students could use English in competitions with their friends on Facebook, they recognized that the English they learned from the class was not useless, which was proof of academic achievement. This evidence of language acquisition was well-perceived by the students, thus solidifying their sense of academic achievement. Also, as many games were competitive with different levels of difficulties, students would feel that they had achieved a higher level of language competence by winning the games. These findings are supported by Vandercruysse et al. (2013). In the article by Vandercruysse et al. (2013), students working in a more competitive environment like the game-based ones often reported higher perceived linguistic competence, more task value, and increased invested effort. It is worth noting here that the COVID-19 opens new opportunities for language teaching and learning as the researchers, administrators, and teachers can observe that through the design and incorporation of mini-games on social networking sites. This implementation of game-based language activities on official university Facebook or Twitter groups can be sustained as a supplementary even after the COVID-19 pandemic to support EFL learners’ language acquisition.

In contrast, two factors, including attendance checking and exam regulations, negatively impacted students’ sense of academic achievement. As the Internet connection of some learners was not stable, it would be unfair if the teacher reduced the learners’ score because he had to attend a compulsory communal COVID-19 test. The reduction of learners’ score due to their inability to answer during a roll call can be subjective and discouraging. Instead, teachers can use other methods of formative assessment such as portfolio or take-home project with negotiable deadlines so that students can obtain their improvement over time and feel an increased sense of self-achievement (Khan, 2006). Also, sitting an online synchronous exam full of multiple-choice questions is risky and unreflective of the EFL learners’ competence. First, if the students’ score is affected by technical issues, the student sense of achievement will be reduced. Also, as the students reported, they did not feel many relations between the test and their actual ability to communicate in English or apply English to their future work. Therefore, instead of synchronous grammar and vocabulary-based exams, the teachers should consider project-based or task-based assessments to assess the learner’s linguistic competence multilaterally.

Conclusion

The research revealed that the participants perceived four dimensions of the CHAT framework, including mediating artifacts, community, rules and regulations, and division of labor as the most dominant factors contributing to the EFL learners’ academic burnout in online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Within the four overarching dimensions, five areas that impacted EFL learners’ physical and psychological exhaustion were prolonged online learning time, privacy concerns and cyber-bullying, teachers’ role, institution’s role, and support community outside the classroom. Also, teachers’ insufficient preparation for online teaching and students’ academic misconduct during exams were aspects causing academic cynicism among the learners. Also, while participation in social networking sites’ extracurricular activities had both positive and negative effects on students’ sense of achievement, participation in checking and cheating in exams exacerbated this last dimension of academic burnout. Acknowledging the root causes of academic burnout, the government, school management, and educator can introduce policies and modify the teaching and learning program and other related aspects to online EFL teaching in an emergency. While the authors tried their best to report what the participant shared unbiasedly, we have to admit that we cannot fully account for the difficulties and losses that students have been through during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the future, other researchers can continue with factors affective teachers’ or administrators’ burnout or compare the matches and mismatches between different perspectives about what burnout could result from in a more general educational context.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HQT Education’s Research Ethics Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

QN was employed by HQT Education Co. Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alonzo, R., Hussain, J., Stranges, S., and Anderson, K. K. (2021). Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: a systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 56:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

Ameen, E. C., Guffey, D. M., and McMillan, J. J. (1996). Accounting students’ perceptions of questionable academic practices and factors affecting their propensity to cheat. Account. Educ. 5, 191–205. doi: 10.1080/09639289600000020

Arroyo, A. T., Kidd, A. R., Burns, S. M., Cruz, I. J., and Lawrence-Lamb, J. E. (2015). Increments of transformation from midnight to daylight: how a professor and four undergraduate students experienced an original philosophy of teaching and learning in two online courses. J. Transformat. Educ. 13, 341–365. doi: 10.1177/1541344615587112

Balogun, J. A., Hoeberlein-Miller, T. M., Schneider, E., and Katz, J. S. (1996). Academic performance is not a viable determinant of physical therapy students’ burnout. Percept. Mot. Skills 83, 21–22. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.83.1.21

Behr, D. (2017). Assessing the use of back translation: the shortcomings of back translation as a quality testing method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 20, 573–584. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2016.1252188

Bolatov, A. K., Seisembekov, T. Z., Askarova, A. Z., Baikanova, R. K., Smailova, D. S., and Fabbro, E. (2021). Online-learning due to covid-19 improved mental health among medical students. Med. Sci. Educ. 31, 183–192. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01165-y

Bottiani, J. H., Duran, C. A. K., Pas, E. T., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2019). Teacher stress and burnout in urban middle schools: associations with job demands, resources, and effective classroom practices. J. Sch. Psychol. 77, 36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.10.002

Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual. Res. 8, 137–152. doi: 10.1177/1468794107085301

Boyd, D. J., Grossman, P. L., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., and Wyckoff, J. (2009). Teacher preparation and student achievement. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 31, 416–440. doi: 10.3102/0162373709353129

Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., and Richardson, V. (2005). Inhibition, integrity and etiquette among online learners: the art of niceness. Except. Child. 71, 195–207. doi: 10.1177/001440290507100205

Conrad, D. (2002). Inhibition, integrity and etiquette among online learners: the art of niceness. Distance Educ. 23, 197–212. doi: 10.1080/0158791022000009204

Department of School Education and Literacy (2020). Guidelines for Digital Education. Available online at: https://diksha.gov.in/ncert/get (accessed December 2, 2021).

D’Souza, K. A., and Siegfeldt, D. V. (2017). A conceptual framework for detecting cheating in online and take-home exams. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 15, 370–391. doi: 10.1111/dsji.12140

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theorical Approach to Developmental Research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit Oy.

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

Fauville, G., Luo, M., Queiroz, A. C. M., Bailenson, J. N., and Hancock, J. (2021). Zoom exhaustion & fatigue scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 4:100119. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100119

Frey, B. B. (ed.) (2018). “Pragmatic paradigm,” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation, (New York, NY: SAGE Publications, Inc). doi: 10.4135/9781506326139.n534

Harouni, H. (2021). Unprepared humanities: a pedagogy (forced) online. J. Philos. Educ. 55, 633–648. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.12566

Hughes, N., and Burke, J. (2018). Sleeping with the frenemy: how restricting ‘bedroom use’ of smartphones impacts happiness and wellbeing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 85, 236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.047

Jacob, S., and Furgerson, S. (2015). Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 17, 1–10. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1718

Jacobs, S. R., and Dodd, D. (2003). Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 44, 291–303.

Kao, Y. T. (2020). Understanding and addressing the challenges of teaching an online CLIL course: a teacher education study. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 25, 656–675. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2020.1713723

Karimi, M. N., and Fallah, N. (2021). Academic burnout, shame, intrinsic motivation and teacher affective support among Iranian EFL learners: a structural equation modeling approach. Curr. Psychol. 40, 2026–2037. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-0138-2

Khan, B. H. (ed.) (2006). “Flexible learning in an information society,” in Flexible Learning in an Information Society, (Hershey, PA: IGI Global). doi: 10.4018/978-1-59904-325-8

Khlaif, Z. N., Salha, S., and Kouraichi, B. (2021). Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: students’ engagement. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 7033–7055. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10566-4

Kim, B., Jee, S., Lee, J., An, S., and Lee, S. M. (2018). Relationships between social support and student burnout: a meta-analytic approach. Stress Health 34, 127–134. doi: 10.1002/smi.2771

Kim, B., Kim, E., and Lee, S. M. (2017). Examining longitudinal relationship among effort reward imbalance, coping strategies and academic burnout in Korean middle school students. Sch. Psychol. Int. 38, 628–646. doi: 10.1177/0143034317723685

Kusnoor, A. V., and Falik, R. (2013). Cheating in medical school: the unacknowledged ailment. South. Med. J. 106, 479–483. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182a14388

Lemola, S., Perkinson-Gloor, N., Brand, S., Dewald-Kaufmann, J. F., and Grob, A. (2015). Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J. Youth Adolesc. 44, 405–418. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0176-x

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 94:102352.

Maimaiti, G., Jia, C., and Hew, K. F. (2021). Student disengagement in web-based videoconferencing supported online learning: an activity theory perspective. Interact. Learn. Environ. 1–20.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

May, R. W., Bauer, K. N., and Fincham, F. D. (2015). School burnout: diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learn. Individ. Dif. 42, 126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.015

Mheidly, N., Fares, M. Y., and Fares, J. (2020). Coping with stress and burnout associated with telecommunication and online learning. Front. Public Health 8:574969. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574969

Ministry of Education and Training (2021). Quy định về quản lý và tổ chức dạy học trực tuyến trong cơ sở giáo dục phổ thông và giáo dục thường xuyên. Available online at: https://moet.gov.vn/content/tintuc/Lists/News/Attachments/7284/09 2021TT BGDDT THÔNG TƯ DẠY HỌC TRỰC TUYẾN.PDF

Misirli, O., and Ergulec, F. (2021). Emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: parents experiences and perspectives. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26:6699–6718. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10520-4

Nasu, V. H., and Afonso, L. E. (2020). Relationship between cynicism and expected cheating in academic and professional life: a study involving lato sensu graduate students in accounting. J. Educ. Res. Account. 14, 352–370.

Noh, H., Chang, E., Jang, Y., Lee, J. H., and Lee, S. M. (2016). Suppressor effects of positive and negative religious coping on academic burnout among korean middle school students. J. Relig. Health 55, 135–146. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0007-8

Peper, E., Wilson, V., Martin, M., Rosegard, E., and Harvey, R. (2021). Avoid zoom fatigue, be present and learn. Neuroregulation 8, 47–56. doi: 10.15540/NR.8.1.47

Portoghese, I., Leiter, M., Maslach, C., Galletta, M., Porru, F., D’Aloja, E., et al. (2018). Measuring burnout among university students: factorial validity, invariance, and latent profiles of the italian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Student Survey (MBI-SS). Front. Psychol. 9:2105. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02105

Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 50, 325–327. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211004138

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., and Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdig. Sci. Educ. 2, 923–945. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

Renk, K., and Smith, T. (2007). Predictors of academic-related stress in college students: an examination of coping, social support, parenting, and anxiety. NASPA J. 44, 405–431. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.1829

Salanova, M., Llorens, S., García-Renedo, M., Burriel, R., Bresó, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Toward a four-dimensional model of burnout: a multigroup factor-analytic study including depersonalization and cynicism. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 65, 901–913. doi: 10.1177/0013164405275662

Samara, O., and Monzon, A. (2021). Zoom burnout amidst a pandemic: perspective from a medical student and learner. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 8:204993612110267. doi: 10.1177/20499361211026717

Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M., and Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 Years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 14, 204–220. doi: 10.1108/13620430910966406

Sokal, L., Trudel, L. E., and Babb, J. (2020). Canadian teachers’ attitudes toward change, efficacy, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 1:100016.

Sokal, L. J., Trudel, L. G. E., and Babb, J. C. (2020). Supporting teachers in times of change: the job demands- resources model and teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Contemp. Educ. 3, 67–74. doi: 10.11114/ijce.v3i2.4931

Stetsenko, A., and Arievitch, I. M. (2004). The self in cultural-historical activity theory: reclaiming the unity of social and individual dimensions of human development. Theory Psychol. 14, 475–503. doi: 10.1177/0959354304044921

Stockwell, G., and Reinders, H. (2019). Technology, motivation and autonomy, and teacher psychology in language learning: exploring the myths and possibilities. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 39, 40–51. doi: 10.1017/S0267190519000084

Suri, H. (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 11, 63–75. doi: 10.3316/QRJ1102063

Tafazoli, D., and Atefi Boroujeni, S. (2021). Legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic for language education: focusing on institutes managers’ lived experiences. J. Multicult. Educ. 16, 30–42. doi: 10.1108/JME-08-2021-0161

Thorne, S. L. (2000). “Beyond bounded activity systems: heterogeneous cultures in instructional uses of persistent conversation,” in Proceedings of the 2000 Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, 1–11.

Turchi, L. B., Bondar, N. A., and Aguilar, L. L. (2020). What really changed? Environments, instruction, and 21st century tools in emergency online English language arts teaching in United States schools during the first pandemic response. Front. Educ. 5:583963. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.583963

Ugwu, F. O., Onyishi, I. E., and Tyoyima, W. A. (2013). Exploring the relationships between academic burnout, self- efficacy and academic engagement among Nigerian college students. Afr. Symp. 13, 37–45.

UNESCO (2020). COVID-19: How the UNESCO Global Education Coalition is Tackling the Biggest Learning Disruption in History. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-how-unesco-global-education-coalition-tackling-biggest-learning-disruption-history (accessed December 6, 2021).

van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: a sociocultural perspective. Educ. Linguist. 3, 169–170.

van Rensburg, J. E. S. (2018). Effective online teaching and learning practices for undergraduate health sciences students: an integrative review. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 9, 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2018.08.004

Vandercruysse, S., Vandewaetere, M., Cornillie, F., and Clarebout, G. (2013). Competition and students’ perceptions in a game-based language learning environment. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 61, 927–950. doi: 10.1007/s11423-013-9314-5

Wang, J.-L., Jackson, L. A., Gaskin, J., and Wang, H.-Z. (2014). The effects of Social Networking Site (SNS) use on college students’ friendship and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 37, 229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.051

Yoon, J. S., and Kerber, K. (2003). Bullying: elementary teachers’ attitudes and intervention strategies. Res. Educ. 69, 27–35.

Appendix

Keywords: academic burnout, cynicism, emergency language teaching, exhaustion, sense of academic achievement

Citation: Bui QTT, Bui TDC and Nguyen QN (2022) Factors Contributing to English as a Foreign Language Learners’ Academic Burnout: An Investigation Through the Lens of Cultural Historical Activity Theory. Front. Educ. 7:911910. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.911910

Received: 03 April 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2022;

Published: 09 June 2022.

Edited by:

Lucas Kohnke, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Marlon Sipe, Walailak University, ThailandStephenie Busbus, Saint Louis University, Philippines

Copyright © 2022 Bui, Bui and Nguyen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Quang Nhat Nguyen, nhatquang.ed@gmail.com

Quyen Thi Thuc Bui

Quyen Thi Thuc Bui Thanh Do Cong Bui1

Thanh Do Cong Bui1  Quang Nhat Nguyen

Quang Nhat Nguyen