Colombian university journalism as a virtual stage for transitions toward acts of memory and peace

- 1Programa de Comunicación Social-Periodismo de la Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Sociales y de la Educación de la Universidad Católica de Pereira, Pereira, Colombia

- 2Carrera del Programa de Marketing y Negocios Digitales de la Escuela de Administración de la Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia

This article is concerned with narrating the research-creation experience that emerged from the CAPAZ project (Analytical Center for University Productions in the Framework of Conflict). It aims to account for the emergence of the transmedia web platform “RUTAS: University Peace Stories in Colombia,” based on the analysis of the media representations produced by the national opinion sector of university journalism that are concerned with peace narratives from 2000 to 2021. A mixed methodological approach and an experimental scheme with Big Data techniques derived from an automated lexicometric analysis led to the implementation of a strategy for creating pedagogical narratives that categorized the results obtained. Thus, RUTAS was born as an exercise involving the deployment of knowledge and creative skills around the notions of design as a possibility and hypermediality as a scenario of digital and interactive stories, housed in virtual, cultural, and open platforms that would give rise to multiple representations and media appropriations in the field of communication and education.

Introduction

This article is presented as the result of a research-creation project carried out within the fields of Educational Communication, design, and art to account for the creation of a digital transmedia platform entitled “RUTAS: University stories of peace in Colombia,” which collects the analysis of the stories produced in 24 university media sources (belonging to 20 universities) by journalism students that are part of the Colombian Network of University Journalism.

This analysis was made in relation to the following recent Colombian historical events: The Armed Conflict, the Memory of the Victims, and the Peace Process. Through these themes, it was possible to analyze how the university media have addressed these events, which made this project an opportunity to think about how the country is being built around the peace process. For this reason, the project “Centro analítico de producciones culturales universitarias en el marco del conflicto” Code: 1349-872-76354 and this publication was financed with resources from Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento para la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación Francisco José de Caldas, Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e innovación (MinCiencias), and co-financed by Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (CNMH), la Universidad Católica de Pereira, y la Universidad del Quindío.

Universities have always been vital institutions in the process of cultural transformation. They get involved through projects where resources and efforts are aimed at the transition toward scenarios of non-violent, active, and dialogic conflicts, as proposed in “The praise of conflict” by Benasayag and del Rey (2018). This matter directly involves academic communities which think and build formative processes around these phenomena to foster the emergence of a culture of peace. Similarly, these institutions are consolidated as mediators in the educational and formative processes concerning the armed conflict, the memory of the victims, and the peace agreements, which in turn become potential scenarios where they transcend curricular matters, creating a real commitment to the “Peace Chair” course linking reflections from the academic field and research.

From a university educational standpoint, the CAPAZ project (Analytical Center for University Productions in the Framework of the Conflict) is not only presented as a project narrated from university journalism, the issues related to the armed conflict, the memory of the victims, and the peace agreements but also as a pedagogical approach for Educational Communication since it actively links the Díaz and Freire (2012) proposal for an expanded education that goes beyond the classical notion of vertical knowledge transfer. Furthermore, it proposes a horizontal knowledge construction among teachers, students, researchers, and the communities themselves.

As part of the CAPAZ project, “RUTAS: University Narratives of Peace in Colombia” is created, which analyzes the media representations of a particular sector of the country’s public opinion related to the narratives of peace in the period 2000–2021, considering some of the most dramatic events in the history of Colombia, including the signing of the Peace Agreement between the Government and the FARC-EP.

This project introduces innovative techniques for constructing and arranging large textual corpora with various tools allowing the automated extraction, format conversion, and text definition of documents containing the systematization of the stories of university students about peace. It is also a pioneering exercise dealing with the analysis of media productions that take communication research methodologies to the limit by introducing the creative intentions for co-design, the exploration of expressive and narrative forms, and using creativity in the digital-pedagogical stories within this scenario.

The project uses the narratives of university journalism as a formative scenario. It scrutinizes a possible university vision capable of mediating different cultural processes around peace in these works; enunciating from research and the subsequent creation of digital and analog narratives; involving the recognition of others in the articulation of a digital experience; and using new media and media environments, through a digital, interactive, open cultural platform. It also involves the development of strategies of social appropriation of knowledge, with audiovisual, sound, and graphic products that give rise to interpretation through a research model using big data.

Ultimately, as Arturo Escobar puts it, autonomous design is resorted to in an attempt “to make society more sensitive and receptive to the newly articulated concerns of the collective” (2017, p. 320). When trying to understand the scenario of the transition toward peace, there is nothing left but the impulse for innovation and creation “of new forms of life arising from struggles, forms of counter-power, and life projects of politically-activated relational and communal ontologies” (2017, p. 324), expressed in the co-design of platforms and content concerning users and other agendas.

Following the ideas of Manovich (2006) in his book “Language of the new media,” the new media environments in which human existence plays a role today are systems where simultaneously the stories, technologies, esthetic and artistic expressions, levels of interactivity, and forms of participation allow us to think about the utopian realization that for many years occupied the center of the critical theories of communication. This utopia, through a dialectical movement between technological development and the new media environments, makes it vital to return to the question: Is it possible to think about the existence of interactive audiences?

There are inevitably linked issues tied to this question that has been debated for many years but that today are updated in the light of Pierre Levy’s (2006) proposal on “Collective Intelligence: for an anthropology of cyberspace,” which has gained importance insofar as it produces a context for thinking about its possible answers. At least, this is how Jenkins (2009) understood it in his work on fans, bloggers, and videogames, describing that these new narrative environments mediated by technologies allow the emergence of a participatory culture that, in addition, configures major trends and changes in the narratives with the use of media.

Although the new media environment where peace narratives are debated today is not a finished territory, it should be assumed as a proposal to understand the evolution and impact that new technologies offer to today’s society, as a sort of achievable utopia. From this perspective, projects and experiences such as “RUTAS,” which try to understand the themes, media, support, and language used by young university students in the construction of journalistic products around the narratives of the conflict, the memory of the victims, and the Peace Agreement, generate the unveiling of other ways of telling, in the words of Omar Rincón “we narrate as we seek to know-ourselves. Perhaps that is why we educate ourselves through stories, we love by seducing with stories, we live to have experiences that can become stories” (2006, p. 90).

Therefore, expansions of digital storytelling, such as experiences through hypermedia stories and the widespread use of multimedia, are today the new narratological devices that determine within a media environment of community participation, the updated ways of thinking, understanding, and explaining through dramatic structures, that is to say, the designs oriented to the conception and materialization of future in this arduous task of thinking and making peace.

Stories told with Aristotelian narrative structures of beginning, knot, and denouement, as well as storytelling with more complex structures such as those proposed by Campbell (2014) based on the Hero’s Journey, are fundamental in the current understanding of the construction of a narrative culture around peace. As Siciliani (2014, p. 44) puts it based on the ideas of Jerome Bruner, stories are fundamental insofar as they are the natural strategy of human beings to account for their own daily experience that materializes through stories.

Understanding narratives allow us to understand that every story is inscribed in a tradition, and “we narrate as a collective, or better yet, to contact others and create communities of meaning” (Rincón, 2006, p. 90). In this same line, there is no narrative without culture or, in other words, insisting on peace narratives in the midst of a violent context implies defining narrative, whatever its format, medium, and language, as a cognitive device capable of configuring memory, anticipating the future, and providing others with an identity.

Undoubtedly, RUTAS opens the way to an old debate between the media and democracy since the way the emergence of some forms of citizenship is understood requires thinking in terms of dialogue and non-violent conflict resolution and goes beyond the traditional concept of citizenship in the abstraction of rights and duties. CAPAZ highlights a civic experience linked to the territory where it interacts with a series of tensions and powers. Likewise, a civic quality is expressed, assumed as living and transforming a historical story from the experience of life itself.

In the specific case of autonomous design with the communities, focused on the recognition of the social movements fighting for the defense of their territory and place, Escobar points out: “the objective of the design process should be the strengthening of the autonomy of the community and its continuous realization” (2017, p. 324). Hence, the importance of ancestry in the communities, their relationships and orientations toward the future, their life projects, and their struggles.

Methodology

“CAPAZ” is the framework project to which the methodological proposal described below belongs. Being conceived as an “analytical center of media productions,” it proposes an experimental and self-developed scheme replicable to various exercises that require building bridges between the processing of large volume corpora and qualitative analysis to interpret data. Thus, this project was consolidated as a binding model of big data techniques, automated lexicometric analysis, and the creation of pedagogical narratives for the ordering of results. All these are stages of a research-creation methodology, which allows for evidence of diverse representations and media appropriations in the field of Educational Communication.

In the case of “RUTAS,” the first CAPAZ project, the analysis focused on the media representations of a sector of national opinion: university journalism around a key issue for the history of the country, such as the narratives of peace in the period 2000–2021, in which events, such as the signing of the Peace Agreement between the National Government and the FARC-EP took place.

The RUTAS transmedia web platform followed a methodology valuing the relevance of mixed, automated studies with a focus on social appropriation developed in three stages:

Stage 1: Construction of the corpus from big data techniques: In this stage of the research and under a “Data Mining” approach, mathematical and quantitative methods were used to expose patterns of large amounts of information stored in different formats, which facilitated the prediction of trends and behaviors from the researcher’s control, something essential for decision-making.

For this reason, the extraction, grouping, and cleaning of the corpus were done by applying field techniques, such as Web Scraping and OCR. These took the compiled data to txt formats (461 in total), which made textual processing possible, and thus the printed, audio, and even audiovisual news were converted into formats that could be analyzed using automated lexicometric techniques.

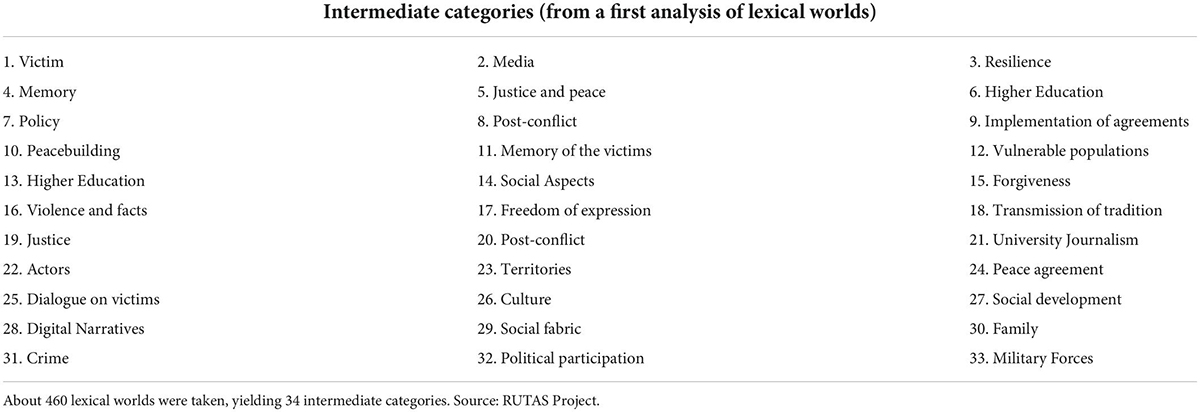

Stage 2: Automated lexicometric analysis and data visualization: It is important to detail automated lexicometric analyses to establish how they work since they take textual corpora. In this case, 3,049 narratives produced by university students about peace were analyzed, disaggregating each word and associating it to a larger context unit in statistical relation according to its semantic meaning as can be seen in Table 1, in relation to the categories of lexical worlds (for RUTAS, around 460 lexical worlds and 34 intermediate categories).

In this descriptive and inferential stage, the textual corpus extracted from 24 media sources belonging to the Colombian Network of University Journalism was studied based on the hierarchical classification method by Reinert (2003). This method establishes that textual discourses can evidence social representation systems. Thus, the analysis of evocation and co-occurrence of lexical worlds, constituted by the set of words present in a sentence, allowed the researcher to understand and give coherence to what is expressed in a txt-type document, which is exceptionally functional when analyzing and finding the meaning of large corpora, as was the case of RUTAS.

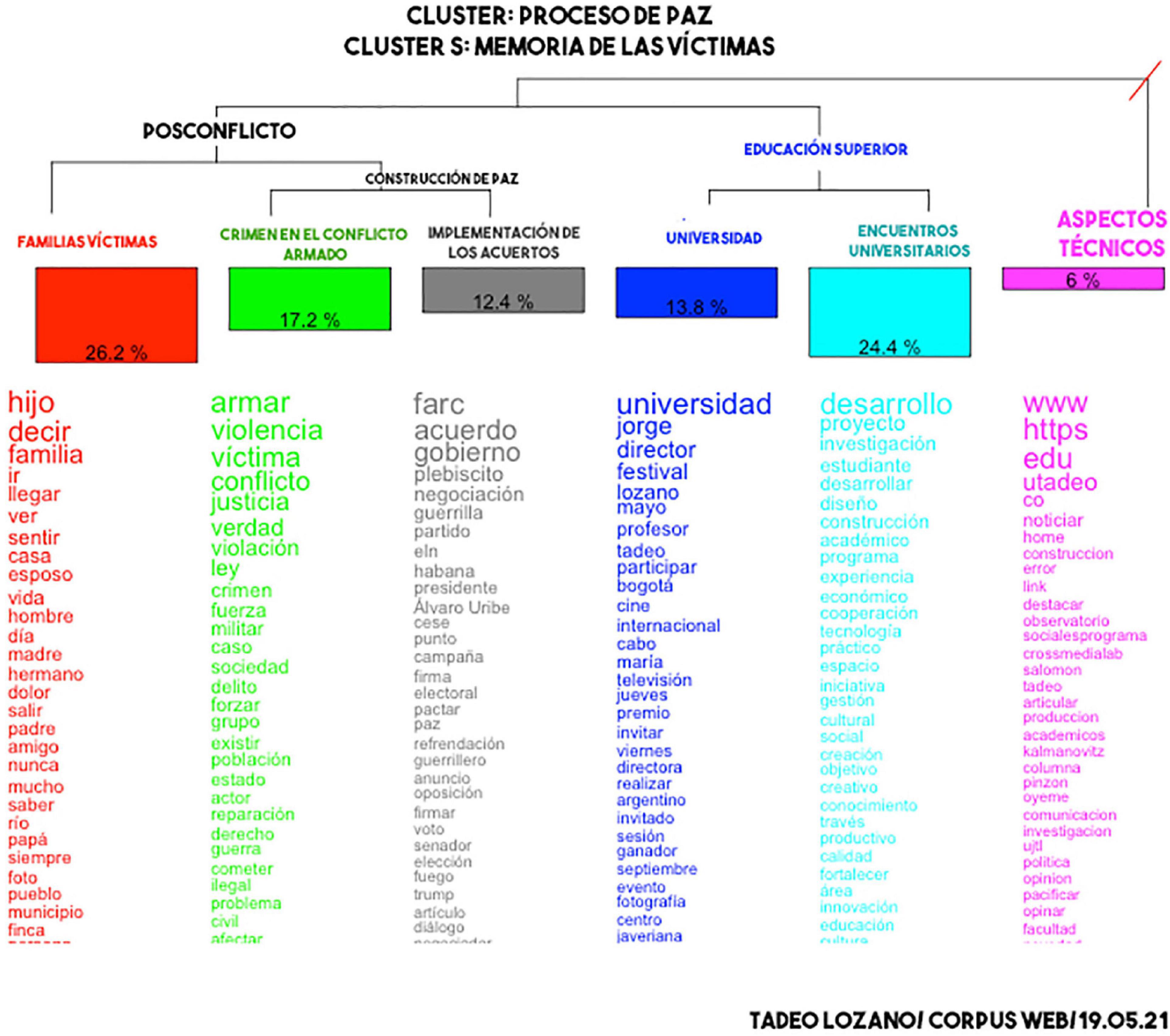

Here, through data engineering automation techniques under an Extraction, Transformation, and Loading (ETL) scheme, the corpus of files (.txt) received a classification treatment by tags in the Iramuteq program. As can be seen in Figure 1, the use of the software allowed the classification of lexical worlds, enabling a multidimensional analysis of the information. Iramuteq, developed to meet the needs of social research where it is required to handle large-volume linguistic materials (Molina-Neira, 2017), was fundamental in the classification of the information obtained and analyzed from three clusters: “Peace Process,” “Victims’ Memory,” and “Armed Conflict.”

Figure 1. Cluster linkage by dendrograms. Processing of lexical worlds from Iramuteq. The cluster “Peace Process” is exemplified, a similar process was followed for “Memory of Victims” and “Armed Conflict.” Source: RUTAS Project.

The clusters were determined at the time of organizing the information in RUTAS by employing lexical cartographies that identified the first communities of discussion and dendrogram grouping policies. This strategy made it possible to relate the communities through the clusters and the correspondence factorial analysis, which generated a statistical cross-check that evidenced the relationship and importance of each community. Inputs were obtained for the final cross-checking of the information using qualitative interpretation sheets, which gave meaning to the data from the researcher’s perspective.

Stage 3: Narrative reinterpretation and design of a multimedia platform: To give visibility to the media agendas created by students during a 20-year peace-process period, it became necessary to recognize the various types of production logic, support, and esthetics of university journalists.

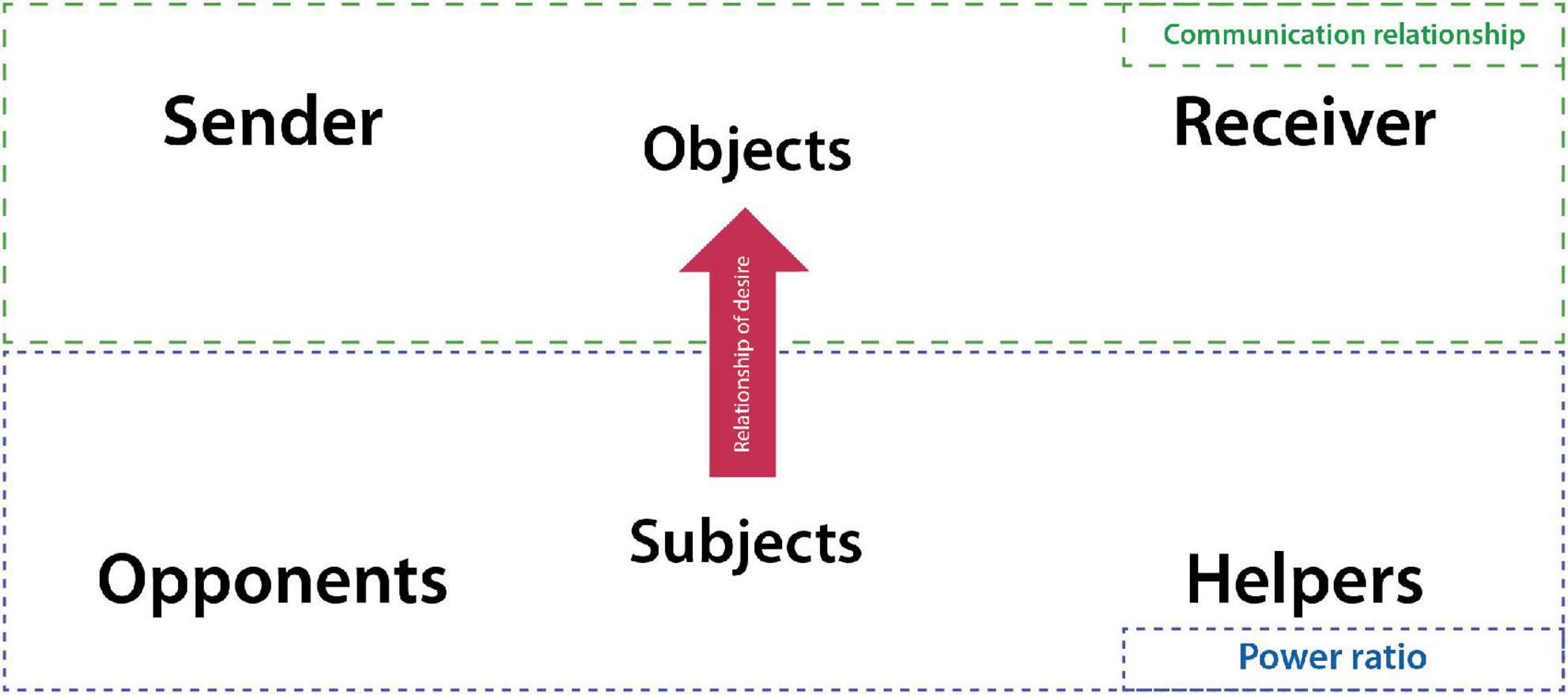

This is why in RUTAS, the quantitative analyses are reinterpreted on the basis of a proposal that attempts to coherently present the data in the clusters and the researchers’ findings. This process is preceded by an entire interpretive approach based on the recognition of narrativity (Greimas, 1987) as a way of observing the meaning of the narratives, since Greimasian semiotics (Hébert and Tabler, 2019) develops a canonical narrative scheme, which, as seen in Figure 2, describes the action from a relational logic of actants, understood as Greimas’ Actantial Model.

Figure 2. Based on Greimas (1987) Actantial Model, the Project developed an analysis of journalistic accounts from the understanding and actantial location vis-à-vis peace narratives. Source: CAPAZ Project.

Understanding the importance of narrative semiotics, A.J. Greimas put forward an Actantial Model (Hébert and Tabler, 2019) that can be used to divide an action into six facets or actants that help to identify common factors in narratives. These allow us to understand the meaning of any narrative act. Following the information in Figure 2, the matrix locates six actors who from their role embody a certain narrative function, triggering bids, barriers, inspiration, and mediation.

The subjects and the objects trigger the initial narrative. The subjects mobilize all their efforts to achieve their desired “object.” They are all located in the plane of desire and are recipients of various actions on the part of other actors.

Opponents and helpers generate relations of barrier or incentive and, in a complementary manner, make the subject go through stages of difficulty or support at the moment of reaching his desired object. Both inhabit the plane that Greimas called “Power,” fulfilling a function of challenge or luck.

The addressers and the addressees move on the plane of communication. These actants precisely give narrative meaning to the story. The addressers are inspirational figures that move the subject on a transcendent plane, while the addressees are the final recipients of the benefit.

In addition to representing the author’s vision of the world, actants, as mobilizing forces of action, allow the reader to connect with the universe of meaning, which goes beyond narrative structures as models and transcends them, reaching the field of identification and memory. Every story told or to be told provides an account of a precise social-historical situation, which is taken to a process of infinite semiosis and starts with the author and updates each reader.

This transcendence of the narrative is installed in the process of reading media stories in RUTAS. It can be seen how the Actantial Model evidences the structure of media representations by identifying different actors as power figures and their relations of opposition-complementarity. In turn, they allowed locating roles in the axes of “communication, power and desire” and their “positive, negative or neutral” positions.

The analysis was derived from a human selection process the researchers carried out by being immersed in the lexicometric analysis and locating the functionality of the actants at the moment of approaching a cluster through the development of qualitative analysis cards. This process integrated their vision into the reinterpretative process, making sense of the stories with the approach of peace and its actants, as well as understanding the students as “Subjects” and the peace stories as “Objects,” in whose plane of desire the narrative of one of the clusters was located: Armed Conflict, Peace Process, and Memory of Victims in Colombia.

Planning of the pedagogical route: The narrative logic of RUTAS, initiated in the actantial analysis, was concretized after a planning exercise by condensing self-developed cards, namely: “qualitative interpretation” and “product planning.” These linked the visualization schemes of lexical worlds with the actantial matrices, clusters, and intermediate variables such as time, territory, medium, support, and even postures present in the base narratives, for more details see the Supplementary material.

As a result of this exercise, summary paragraphs, informational incises, and types of journalistic products created for the platform were obtained. These serve as inputs nourishing the visualization and navigation schemes contemplated in the final stage of the project, namely the design of an open interactive cultural platform.

Discussion and results

University media’s nature entails a particular type of editorial freedom in its genesis, countering the hegemonic narratives derived from a logic of power coming from the political, economic, and epistemic domain that coerces the sense of social interaction present in communication.

In light of journalistic veracity, university portals have become a relevant consultation base for the possibilities of other narratives, cultural diversities, other perspectives that may be alien to the logic manifestations of the Anthropocene, and the domains of economic power, all implicit in the imbricated capacity of social interactions. This realm of possibilities undoubtedly contributes to the limiting of the significance of the armed conflict to expand its borders to a framework of narrative integration that is of common interest and that we are interested in representing.

Currently, there are no web portals in the country created by public entities to disseminate a large number of cultural productions with the thematic interest of this research. Until a few years ago, there was Oropéndola arte y conflicto, a portal that classified artistic works with different levels of professionalism, supported by the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Verdad Abierta, and Fundación Ideas para la Paz (National Center of Historical Memory, Open Truth, and Ideas for Peace Foundation), which was part of the Museo Nacional de la Memoria (National Memory Museum) in Colombia.

RUTAS, supported by the National Center of Historical Memory itself, and unlike Oropéndola, focuses on journalistic student perspectives as a basis for its subsequent analysis of the narrative meaning by the internal research group; managing to present discursive linearity about the events of the Armed Conflict, the Memory of the Victims, and the Peace Process. Furthermore, it updates the thematic review from a “hyper-esthetic” conception of the stories, which for Genette (2014, p. 448) addresses the possibilities of the juxtaposition of layers of signification and thus vindicates the state of transit to the post-conflict in the light of the Peace Process, derived from the Peace Agreement signed with the FARC-EP in Colombia.

Validating the conceptions of other types of knowledge and other forms of rationality allows for an epistemic enrichment around them, inclusive of other discursive possibilities that are fed back in a dialogic exercise. It is valuable to point out that RUTAS https://www.rutas.com.co/es is the first public transmedia web platform to gather the university’s journalistic perspective from a mixed methodology that investigates the axes of power present in the stories of the institutional portals, managing to account for a panorama in the regions of the country.

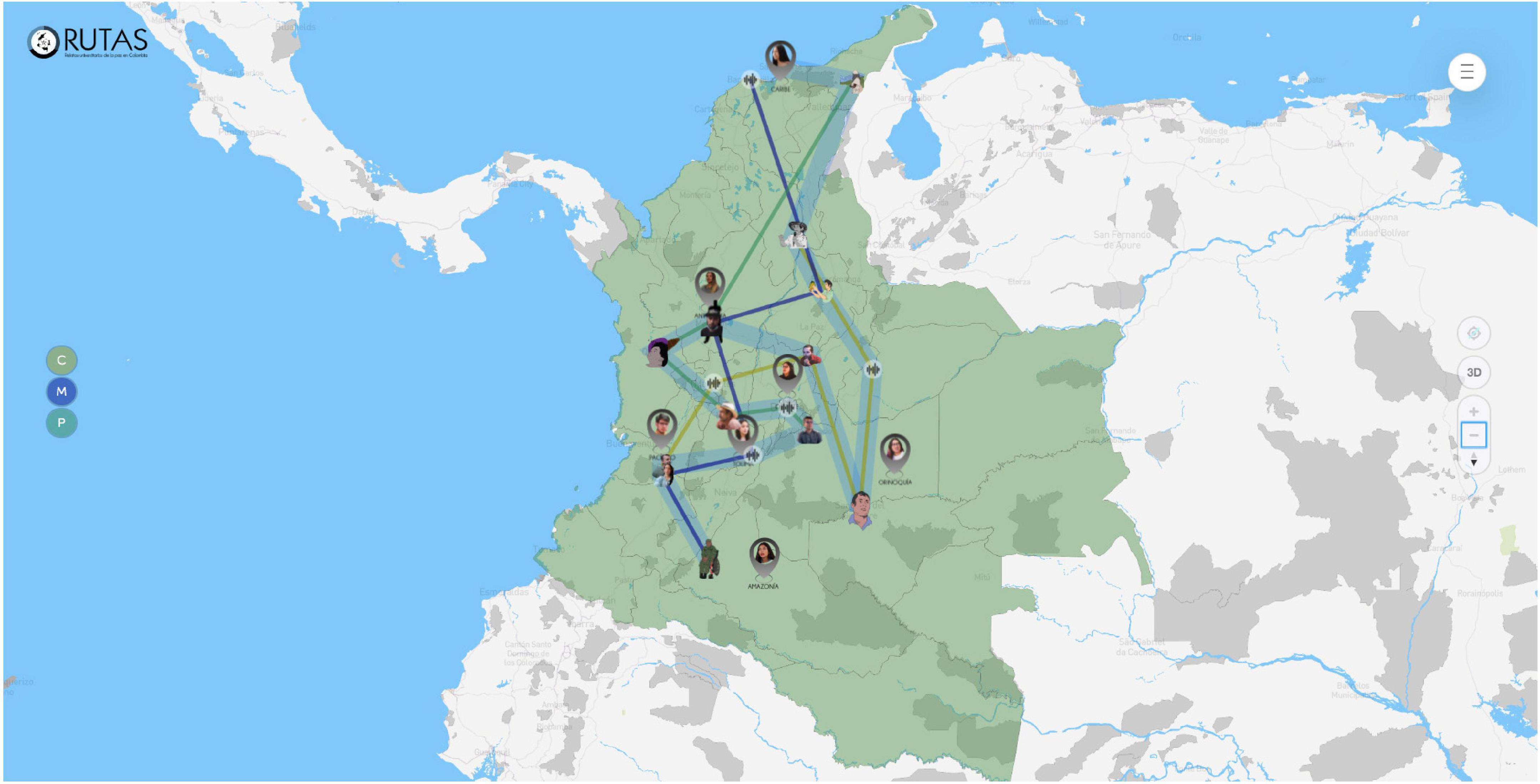

The development of the university narratives that make up the corpus analyzed is characterized by belonging to the following regions: Antioquia-Eje Cafetero (Coffee axis), Caribbean, Central-East, Amazon, Tolima Grande, Orinoco, and Pacific, which indicates at first how other areas of the country are narrated, such as the Amazon, of which not many current productions were identified, suggesting questions about the origin of the conflict, its topographical interactions, and social representations.

The present context of the regions in the map of the country, of which the Andean one has a greater presence in the number of pieces produced and from which the other regions are mostly told, is presented in RUTAS from a conventional map with its municipalities, departments, main natural parks, and water tributaries to strengthen “(.) languages and subjectivities that become an active -and questioning- part of a democratic culture of difference(s)” (Richard, 2017, p. 306) on the development of narratives, which for RUTAS is presented from its subsequent analysis of conflict, memory, and peace, as recurrent social phenomena in the recent history of the country.

This referentiality or self-citation, recalling the “hyper-esthetic” condition proposed by Genette, is then assumed as a continental identification of armed confrontation, social inequality, environmental crisis, and political tensions that are cross-sectional in the search for peace and social equality.

The graphical representation of the map of the country is then a way of approaching the relationship between the biotic and cultural environment. Although, in the student productions analyzed in RUTAS (except for a few from Guaviare and Caquetá), illicit crops and mining and extractivist interests in the Amazon region are not mentioned in quantity—probably due to security problems and displacements, to name a few events—social logics attributed to the tensions alluded to in the region are presented from their narrative sense. Here, the significance of narrative connections also has the Amazon region as a background, not by chance, but by trying to better understand its ecological relevance and the possibility to transit to other more benign ways of relating to our ecosystem, exemplified by Escobar (2017, p. 356) when referring to ancestral cultures as a possibility of environmental recovery, in this case, from shamanism.

Let us remember that the myth of the Ancestral Anaconda that crosses the countries present in the Amazon (Venezuela, Brazil, Peru, and Colombia) is still present in various Amazonian communities and is interpreted in many ways. It includes the presence of rivers and how they are integrated into the physical, spiritual, and cosmogonic realities through their shamanic cultures, which in part have survived since the 18th century to the first ethnobotanical expeditions, the religious evangelization in the 19th century, and the armed confrontation present today.

he existence of the ancestral anaconda as the bifurcation of rivers and these, in turn, as part and deployment of a “shamanic geography” (Cayón, 2017, p. 250) and of its symbolic potentialities as an expanding umbilical cord recalls the “rhizomatic” connection, connecting one point to another without apparent directionality, apropos of the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari (2020, p. 25), or in “radicant” displacement, rooting from one point to another with determination, as explained by Bourriaud (2009, p. 62). This view proposes possible western analogies coming from the growth of flora. The complex organic and living system that we present of the Amazon and its rivers is determinant for the design of the transmedia web platform RUTAS, its genesis, and conception of the interaction in the web agency of the represented territory itself.

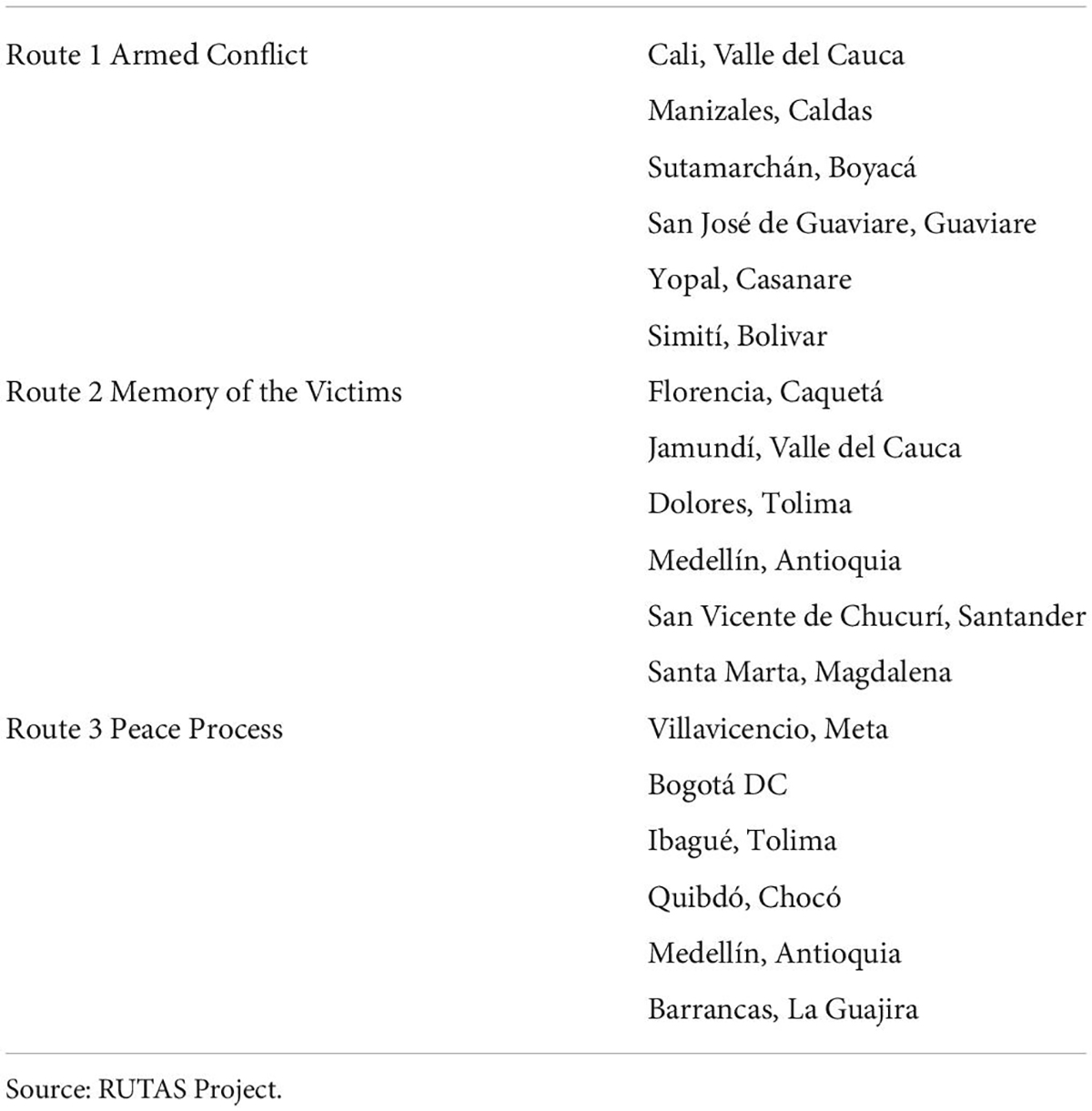

Given the relevance of the rivers in the Amazon region and their connections to other regions of the country, due to the arborescent connectivity of the tributaries, RUTAS proposes to value the fact of water navigability through the use of the image of a boat as a significant trope for web design. The metaphor of navigating on the web is linkd directly to the navigability of the rivers that connect three narrative routes: Armed Conflict, Memory of the Victims, and Peace Process, as can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Interaction routes and the municipalities making part of them: Armed Conflict, Memory of the Victims, and Peace Process.

Navigating through these three discursive and hydrological routes is the way the analyses were presented to understand how some university programs assumed variants of the conflict in the last decades.

As already noted, the sense of the boat in the design of the user interface of the RUTAS platform supports the narrative conception of connectivity of nodes for each thematic axis while, thanks to it, going through the map to reaffirm the condition of the experiential flow, as a didactic element of access to the contents. This strategy condenses the form of representation of the student productions so that its meaning is reiterated in an underlying way in its conceptual and formal postulates, as an integral understanding, a matter that José Luis Pardo points out about Gilles Deleuze’s Logic of meaning (as “event” of meaning and as “intensity” of sensation) (Pardo, 2014, p. 241). This reiterates the capacity of meaning, which for RUTAS is enabled by the metaphor of the boat that navigates the rivers and the modes of user design for each route.

The controls for such navigability, present on the right side of the interface (see Figure 3), allow changing from 2D to 3D appearance. Likewise, such interaction becomes more agile depending on the use of screens and devices, achieving expanded gestures when choosing the angle of travel. This angle varies depending on the chosen site since the place and perspective can be changed without altering the readability of the map. Its construction is not based on an image of it but on the real-time reading of algorithms present in the Mapbox database of free access maps using Google Maps as a base. This is in turn provided with layers of information such as terrain, departmental and municipal division, emblematic sectors, and other data arranged in different layers of representation with the use of a programming language. In the same place, zoom-in and zoom-out capabilities were developed to cover and detail of the map.

Figure 3. The initial view of the platform. Interactions routes: Armed Conflict, Memory of the Victims, Peace Process. Source: RUTAS platform.

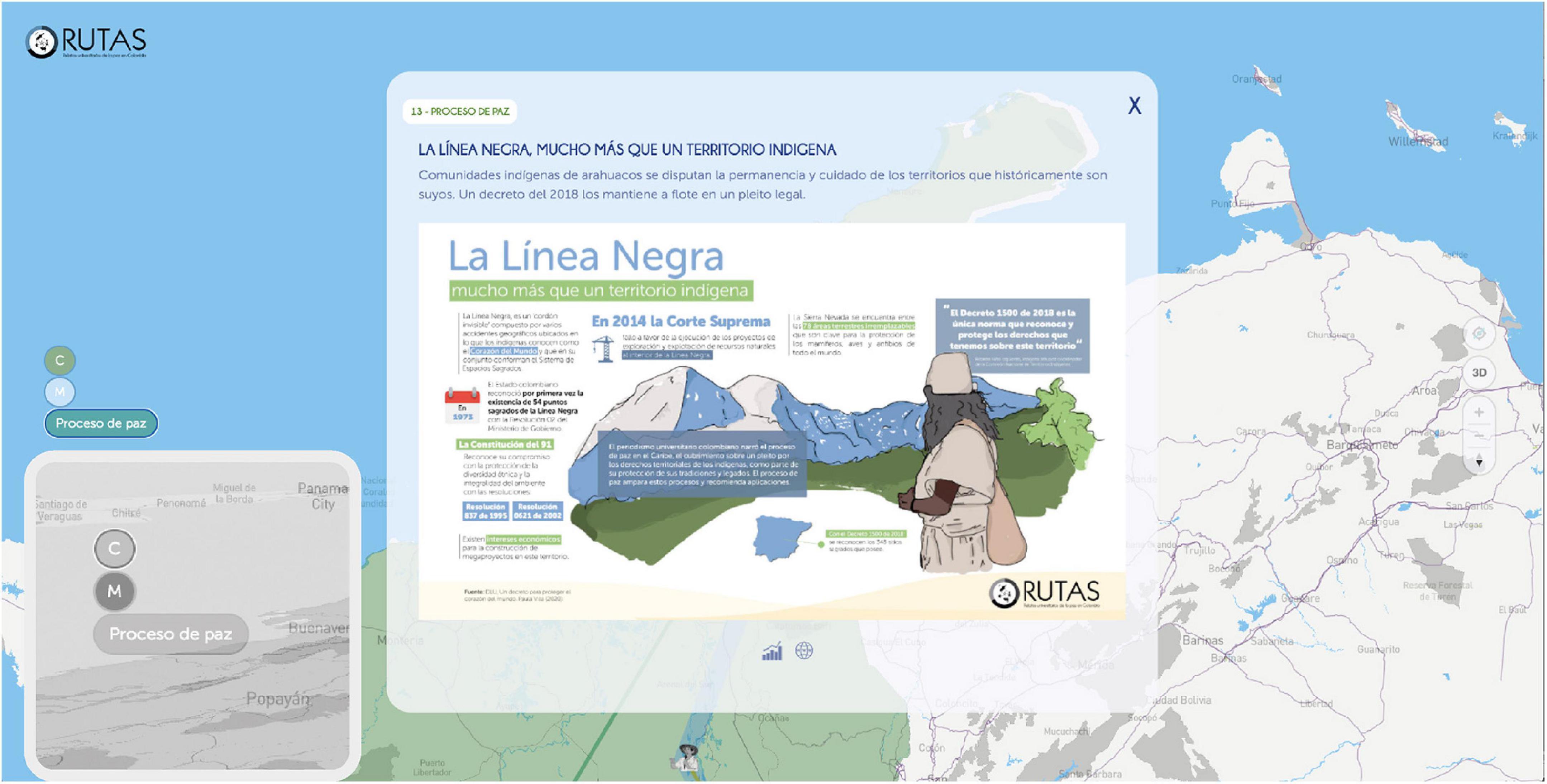

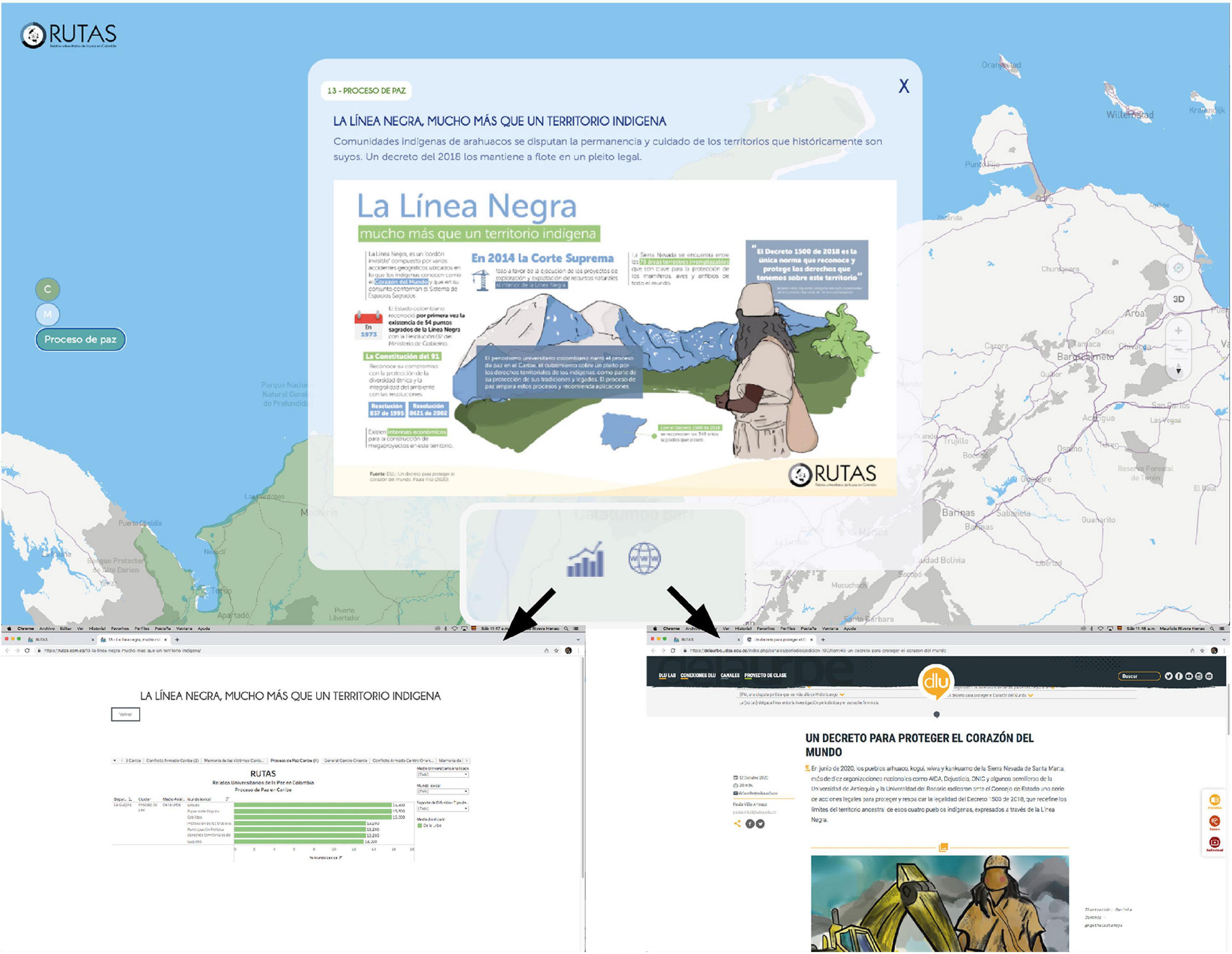

This interactive condition is delimited by each route activated on the left, which indicates the types of narrative paths (see Figure 4). An example of the result of the crossover between the university production, the analysis of the RUTAS research team, and the design bet on having entered one of the routes (Peace Process) is the selection of a place from a pointer that directs to the municipality, for example, Black Line in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. The Black Line is a cosmogonic place that elucidates the complexity by which the territory is in danger and tensions arising between the laws of ancestral origin and those of the State. Thanks to the Peace Process, some agreements have been reached to benefit communities at risk of losing their territories.

Figure 4. Navigation view of the cluster Peace Process on the platform. Infographic “La Linea Negra” (Black Line). Source: RUTAS platform.

The original thinking of the ancestral territories, in this case, the north of the country, warns of the relational fabric of the communities around it and their interdependence. Recalling the concept of “becoming-with” revisited by Haraway (2019, p. 36), which affirms the importance of the connection, and exchange with other matters: another reality, perspective, thing, and being, which leads to an “intra-action and interaction.” Unlike closed autonomous systems, it mutually responds to the possibility of the exchange not only between humans but also with the territories by assuming them as living entities through particular forms of culture in a context of advocating for environmental balance.

Therefore, it is of vital importance to notice how the development of the Peace Process resizes the regional needs of the communities and their ancestral territories for “Good Living,” as Escobar (2017, p. 185) comments on the applicability of other more beneficial ways of living so that everyday dimensions are recovered from traditional knowledge, allowing us to turn around the environmental crisis, not only dependent on the logics of economic, political, and cultural powers.

Each route then leads to a pointer, which opens a window in which the cluster (thematic axis) is enunciated and contextualized according to its particularity in a descriptive paragraph, and the result of the analysis, which may be composed of a sound, audiovisual, or infographic piece. Below it, two icons appear, allowing access to the news of journalism students published in various portals and another to the statistical information of the classification and big data analysis presented in Tableau; both inputs are problematized in the piece made by the internal team of RUTAS (see Figure 5). When closing each window, you can iterate through the other pointers or go back to the beginning, where you will find an introductory video of the project.

Figure 5. Cluster navigation views Peace Process, analysis result in tableau, and the student’s news. Source: RUTAS platform.

Conclusion

Academia has outlined paths questioning the transitions toward peace based on contextual questions of the communities affected by the conflict established in university spaces to allow for, as Mariluz Restrepo (2003) points out, possible meanings responding to the contingencies resulting from the conflict and the peace process, which implies continuously problematizing the discursive hegemonies in the light of dialogue.

Therefore, Colombian society is demanding an instituting university that replicates what happened after the signing of the peace agreements between the Government and the FARC in 2016. This is what the research-creation project RUTAS responds to as a platform that contributes to the inquiries about the transition to peace.

In this sense, as proposed by Charles S. Peirce, quoted by Restrepo (2003, p. 3), the university is invited to define itself as a place not only to instruct and facilitate the economic success of its students but also to learn to solve problems since there is no better institution today with the capacity and potential to become a mediating device in the construction of a “culture of peace” corresponding to its specific educational project, than universities. For Marc Augé (2012, p. 148), these thought scenarios should challenge human beings in the search for a shared future, using all available tools to think of a possible time ahead where we can all contribute from our particularities.

Thus, universities have become protagonists in the various issues concerning peace since the idea of building new narratives to produce ourselves, as subjects and as cultures, is within the framework of a mediating university, which cannot be detached from the urgent issues established as a country. It is necessary to assume citizen mediation capable of inaugurating and deploying the creative capacity of new stories in its communities to help us avoid surrendering as a society and install bonding narratives and stories to continue to exist as a society.

These considerations lead us to think of narrative facts as self-knowledge (Chul Han, 2015, p. 76). It is in this way that the essence of the project is consolidated, which is manifested from the university narrative supported by the correlation of the observed person, in other words, the expansion of the stories not only falls on those who lived or wrote them but also on those who dared to navigate through the transmedia web platform RUTAS.

It was there that the mixed methodology, which started with automated analysis, recognized the importance of narrative analysis in its later stages with human intervention from qualitative analysis cards and the creation of pieces of reinterpretation of the data. These pieces were designed by the team as ways to go through the media research—transcending the extremes of parameterized statistics and content production, toward mediation as a process, which gave rise to the value of the processed data, completing the exercise in an open-access multimedia product.

From the field of Educational Communication and journalism, The RUTAS experience proposes direct actions, generating products in the key of co-participation with all the actors, offering its linkage in expanding the stories from their forms of navigability and participation through strategies of social appropriation. This approach gives the methodology particular importance in creating diagnoses and the research-creation the opportunity to link to a historical understanding of the phenomenon of violence. In addition, it enables adhering to specific propositional lines that allow understanding esthetic and stylistic factors associated with the position of their creators in the stories of university journalism.

Colombian university students have reported multimedia content production techniques and platforms on the Peace Process, the Armed Conflict, and the Memory of the Victims from different formats. As expressed by Jenkins (2008, p. 238), communities today describe themselves through diverse expressive formats using media and putting their identity into play through co-creation processes. The transmedia web platform RUTAS proposes a participatory scenario where techniques give rise to localized narratives not appearing in the country’s large media systems.

This is how the perceptions and experiences of young people through narratives create possible memory scenarios concerning the events told from different hybrid techniques of journalism, which in recent decades have been of considerable interest in the academic and university field. It is worth noting their marked freedom outside the coercion of the media, traditionally dependent on the logic of economic power and gathered in the Colombian Network of University Journalism. It is, therefore, relevant that student productions are accessed by communication and education researchers who investigate an inclusive and more real panorama of the events derived from the conflict.

RUTAS then became a transmedia web platform of great interest for researchers in communication, education, and other areas of knowledge interested in the narratives of peace in the country in the last two decades. Moreover, many communities in the Colombian territory are located in heritage sites declared by the State and international entities. These circumstances are present in the project; however, it is not possible to cover all the cultural expressions of the Colombian territory. Therefore, RUTAS found an essential approach in the academic field of Design, Educational Communication, and Art as support for connections and reflections in an interactive digital context that aims to feed the proactive discussions for the transitions toward an inclusive and strengthened peace.

However, it is necessary to reflect on the amount of data generated by a conflict that has transcended generations, and that makes the analysis a complex work. It could be affirmed that this is one of the issues that should be strengthened for future texts since the qualitative look camouflages the frames of reference of the researchers and university journalists who have recounted the diverse situations left by a highly complex process. Similarly, it should be noted that this allows us to affirm that the power of this type of research lies in the possibility of confronting the representations that have been woven around the war, the victims, and the hope of leaving behind such a dark chapter for a country that cannot yet be integrated into narratives of the future. In this order of ideas, it must be said that the university, governmental entities, and the various groups that represent the citizenry must have intervention projects to disseminate this type of work, which will allow us to consolidate a collective memory where we can think about not repeating the same mistakes. But this is an exercise that must be done jointly, with support, not only from a budget perspective but also from the political will to persevere in this enterprise. This is how the project in question is consolidated as a virtual scenario of interaction among people based on cultural productions. Thus, the process of transformation of a conglomerate of social circumstances in journalistic productions converted into an act of memory came about, giving life to other forms of citizenship expressed on the platform through interaction, making other stories visible that had been excluded from the large circuits of media information. These stories express the tensions of power lived in a territory, its actors, schemes of representation, and places from where to approach the transitions toward peace that university journalism in Colombia has made possible in the last two decades.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PR, MR, CB, and JP contributed to the conception and design of the study. CB made the introduction of the manuscript. PR and JP advanced in the quantitative statistical analysis and methodological construction. MR advanced in the theoretical discussions toward qualitative aspects, which resulted in explaining the transmedia web platform entitled RUTAS. CA was in charge of adapting the manuscript to the Harvard citation format, the reading, and subsequent review of style and the orthotypographical correction. All authors contributed to the conclusions, and also contributed to the reading and approval of the submitted version.

Funding

This project “Centro Analítico de Producciones Culturales Universitarias en el Marco del Conflicto” Code: 1349-872-76354 and this publication was financed with resources from Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento para la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Innovación Francisco José de Caldas, Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e innovación (MinCiencias), and co-financed by Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (CNMH), the Universidad Católica de Pereira, and the Universidad del Quindío.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.953144/full#supplementary-material

References

Benasayag, M., and del Rey, A. (2018). Elogio del conflicto (Praise for the conflict). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Desde Abajo.

Campbell, J. (2014). El héroe de las mil caras. Psicoanálisis del mito. (The hero of a thousand faces. Psychoanalysis of myth). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Cayón, L. (2017). Pienso, luego creo: La teoría makuna del mundo (I think, therefore I believe: The makuna theory of the world). Bogotá: Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History.

Chul Han, B. (2015). Psicopolítica, neoliberalismo y nuevas técnicas de poder (Psychopolitics, neoliberalism, and new techniques of power). Barcelona: Herder. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvt7x7vj

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. (2020). Mil mesetas: Capitalismo y esquizofrenia (A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia). Valencia: Pre-textos.

Escobar, A. (2017). Autonomía y diseño: La realización de lo comunal (Autonomy and design: The realization of the communal). Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón.

Genette, G. (2014). Palimpsestes: La littérature au second degré. Kindle edition. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Greimas, J. (1987). Semántica estructural. Investigación metodológica (Structural semantics. Investigación metodológica). Madrid: Editorial Gredos S.A.

Haraway, D. (2019). Seguir con el problema: Generar parentesco en el chthuluceno (Keeping up with the problem: Generating kinship in the chthulucene). Bilbao: Consonni.

Hébert, L., and Tabler, J. (2019). An introduction to applied semiotics, tools for text and image analysis. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Fans, blogueros y videojuegos (Fans, bloggers and video games). La cultura de la colaboración. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

Levy, P. (2006). Inteligencia colectiva: Por una antopología del ciberespacio (Collective intelligence: For an anthropology of cyberspace). Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization.

Manovich, L. (2006). El lenguaje de los nuevos medios de comunicación: La imagen en la era digital (The language of the new media: The image in the digital era). Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Molina-Neira, J. (2017). Tutorial para el análisis de textos con el software IRAMUTEQ. Didáctica de la historia, la geografía y otras ciencias sociales (Tutorial for text analysis with IRAMUTEQ software. Didactics of history, geography, and other social sciences). Barcelona: Universidad d e Barcelona.

Reinert, M. (2003). Le rôle de la répétition dans la représentationdu sens et son approche statistique par la méthode “ALCESTE”. Semiotica 147, 389–420. doi: 10.1515/semi.2003.100

Restrepo, M. (2003). Universidad mediadora de cultura (The university as a mediator of culture). Revista pensar iberoamericana. Available online at: https://red.pucp.edu.pe/ridei/files/2013/05/130502.pdf (accessed February 20, 2022).

Richard, N. (2017). “Escenario democrático y política de las diferencias,” in En representaciones, emergencias y resistencias de la crítica cultural: Mujeres intelectuales en América Latina y el caribe, eds N. Prigorian and C. D. Orozco (Buenos Aires: CLASCSO), 297–308. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv253f64v.14

Rincón, O. (2006). Narrativas mediáticas o cómo se cuenta la sociedad del entretenimiento (Media narratives or how the entertainment society is told). Barcelona: Gedisa.

Keywords: armed conflict, victims’ memory, peace process, big data, lexicometric analysis, pedagogical narratives, transmedia platform

Citation: Rendon Cardona PA, Rivera Henao M, Betancurth Becerra CM, Aristizábal CA and Páez Valdéz JE (2022) Colombian university journalism as a virtual stage for transitions toward acts of memory and peace. Front. Educ. 7:953144. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.953144

Received: 25 May 2022; Accepted: 06 September 2022;

Published: 26 September 2022.

Edited by:

Miguel Ángel Queiruga-Dios, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

Theodora A. Maniou, University of Cyprus, CyprusArnau Gifreu, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Rendon Cardona, Rivera Henao, Betancurth Becerra, Aristizábal and Páez Valdéz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paula Andrea Rendon Cardona, paula.rendon@ucp.edu.co

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Paula Andrea Rendon Cardona

Paula Andrea Rendon Cardona Mauricio Rivera Henao

Mauricio Rivera Henao Carlos Mario Betancurth Becerra

Carlos Mario Betancurth Becerra Cesar Alberto Aristizábal

Cesar Alberto Aristizábal Julián Enrique Páez Valdéz

Julián Enrique Páez Valdéz