- 1Department of Disability and Psychoeducational Studies, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 2Department of Advanced Studies in Education and Counseling, California State University, Long Beach, CA, United States

- 3Department of Educational Services and Leadership, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ, United States

- 4Department of Counseling and Human Development, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, United States

The American School Counseling Association calls for professional school counselors to support the holistic development and success of all students. However, the field of school counseling is riddled with practices that have harmed and dehumanized Black students. For example, school counselors engage in practices (e.g., social–emotional learning and vocational guidance), which work to reinforce white supremacy and dehumanize Black students. Further, school counselors may also contribute to the ways that the basic and unique needs of Black students are overlooked, leading to the continued systemic adultification of Black students. What is needed is a radical imagination of school counseling, which centers on homeplace as the foundation in order to engage in freedom dreaming. In this article, the authors engage this radical imagination to detail an antiracist view of school counseling practice that embraces freedom dreaming and homeplace through healing and Indigenous educational practices, youth-led school counseling, and critical hip-hop practices to promote joy, creativity, power, love, resistance, and liberation.

Introduction

The American School Counseling Association's [ASCA] ethical standards (ASCA, 2022) state that school counselors are advocates for systemic change who promote students being treated with dignity and provide access to services that support a safe school environment. School counseling, in its current form, is a program tailored to the academic, social–emotional, and career needs of students through continuous collaboration with students, families, and educators (ASCA, 2019). In this paper, we imagine the ways that school counseling programs can truly uplift the voices of Black and brown youth, support their healing as they traverse new pathways to learning, and protect them from systemic harm. We imagine school counseling programs that love and protect youth (Mayes and Byrd, 2022) by building on homeplace in an effort to promote freedom dreaming (hooks, 1990; Kelley, 2003). Considering about acts of love, we imagine a school counseling world that incorporates historically valued practices, especially those still practiced within Indigenous communities, to ground the healing practices used to respond to youth's mental health needs. We also look at how school counseling can be shaped by youth, partnering with them to develop systems, and practices that are safe and welcoming for all students. We believe hip-hop culture can be the vehicle to engage youth in a continued interrogation of the world around them while also providing space where students are encouraged to have fun, be themselves, and experience joy.

The purpose of this paper is to freedom dream school counseling. We define this as a process of collectively envisioning school counseling as an act of love, dreaming of the school building as a place that protects and uplifts the various identities that students encompass; a process of radically imagining school counseling without focusing on the barriers that have historically plagued reform (Kelley, 2003; Love, 2019). Rather than focusing on the obstacles that Black youth have to overcome in education, freedom dreaming focuses on the school counseling we would like to see—one that imagines mutual respect, joy, and love at the center of all programming (Kelley, 2003). Although we recognize that our realities may be constrained by current and historical challenges present in K-12 education, we frame the work needed to actualize our dreaming in antiracism and antiracist practices.

We utilize Mayes and Byrd's (2022) framework to ground our understanding of antiracist school counseling. That is, we define antiracism as an action-oriented process that begins with the development of critical consciousness, focused on the continuous reflection of the school counselors' and their students' power, privilege, and oppression, and how it impacts their experiences within the school setting. School counselors reflect on how their programming centers love and protection of Black and brown youth. As school counselors focus on loving and protecting all students, especially Black youth, they advocate to dismantle systems and practices that are oppressive. Finally, school counselors work with various communities and educational stakeholders to build new programs that love and protect students.

Additionally, we assert that a goal within antiracist school counseling is to create and sustain a homeplace. We define homeplace as a space where students are seen as whole human beings, allowed to grow and heal. Homeplaces exist to center the joy and excellence of youth as they resist the dominant narratives that perpetuate negative stereotypes of Black youth (hooks, 1990; Carey, 2019; Love, 2019).

Although the paper will radically imagine a school counseling space that welcomes Black youth, important to note are the historical challenges Black youth have faced because of the United States (U.S.) education system, specifically in school counseling. Historically, in the U.S., Black Americans have been the only population criminalized for learning to read and write (Hannah-Jones et al., 2019). The remnants of keeping Black youth from learning continue through zero-tolerance policies, standardized testing, and curriculum development that centers on whiteness and white societal norms. As such, school counseling practices, while attempting to provide more equitable services, have focused on interventions that change students to comply with the industrial model of education with little to no emphasis on changing the system to be more inclusive to students who identify as Black, Indigenous, and/or People of Color (BIPOC; McMahon et al., 2014).

In response to the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in the summer of 2020, scholars in education and school counseling (re)viewed their practices in K-12 schools to focus on antiracism. Antiracism, while not a new concept in education, has recently made appearances in school counseling literature (Edirmanasinghe et al., 2022; Holcomb-McCoy, 2022b; Mayes and Byrd, 2022). Antiracist school counseling calls for school counselors to reflect on the ways racism intersects with other oppressions and how it impacts structures within K-12 school systems. Additionally, antiracist school counselors actively work to dismantle the policies and practices within these structures to center the needs of minoritized students (Holcomb-McCoy, 2022a; Mayes and Byrd, 2022). While communities of school counselors are developing more resources to implement antiracist school counseling practices, politicians are fighting against inclusion through legislation that criminalizes antiracist work. In the U.S., 17 states have signed into law or taken states to restrict teachers from teaching anything related to critical race theory (Schwartz, 2021). Additionally, states have proposed anti-Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and/or Queer (LGBTQ) legislation (e.g., Florida HB 1557, of the “Don't Say Gay Bill”), anti-Social Emotional Learning (SEL) legislation (e.g., Oklahoma SB 1442), and even anti-school counseling legislation (e.g., Alabama HB 457). Although this legislation sheds a light on the obstacles educators are facing in providing practices that uplift youth from various historically oppressed identities, in this paper, we focus on envisioning school counseling practices that support and celebrate Black youth despite the frequent challenges.

School counseling history

In the early 1900s, the profession of school counseling began with a focus on vocational guidance. More specifically, the “United States was in the throes of protest and reform stemming from “negative social conditions” related to the industrial revolution” and school counseling was seen as a way to help students prepare for new opportunities in an industrialized nation (Stephens and Lindsey, 2011, p. 15). As school counselors embarked on this vocational guidance endeavor, it is important to understand the social context in which it is rooted. Vocational guidance was shaped in predominantly white schools to meet the needs of white, often working class, students who were being served by white school counselors (Atkins and Oglesby, 2019). Governmental legislation, such as the National Defense Education Act, shaped vocational guidance and situated the needs of predominantly white students and their families in the 1950s. As such, vocational guidance purposefully overlooked and excluded the vocational needs of BIPOC students. To further exacerbate inequities in vocational guidance, the onset of desegregation after the Brown V. Board decision may have allowed for Black students to attend white schools, but it did not necessarily mean that school counseling service delivery included Black students. In fact, even after the formation of the national professional school counseling organization, American School Counselor Association (ASCA), in 1958, there was only a desire to formalize school counseling but there was no guidance or training related to multiculturalism and racial equity (Stephens and Lindsey, 2011; Atkins and Oglesby, 2019).

Under the guidance of ASCA, school counseling has grown and shifted over the years to be more holistic and comprehensive, often through the advocacy of other organizations and leaders. ASCA expanded the school counseling profession to focus on vocational guidance (career development), socioemotional development, and academic counseling (Atkins and Oglesby, 2019). However, this focus was still short-sided as it did not account for the ways in which systemic barriers can interrupt and stifle healthy development, especially for BIPOC children. Thus, school counselors were more focused on “fixing kids” rather than the broken systems that render them vulnerable. However, with advocacy from the National Center for Transforming School Counseling (n.d.) housed within the Education Trust, there was a greater call for school counseling to be more impactful. In particular, the NCTSC called for school counselors to center the relationships between students and their school environment as a way to identify and reduce the effects of institutional barriers that harm students. More specifically, this is called for a proactive and intentional vision of school counseling that incorporated leadership, advocacy, teaming and collaboration, counseling and coordination, and assessment and use of data (National Center for Transforming School Counseling, n.d.). The advocacy of the NCTSC and Education Trust both propelled the field of school counseling forward as ASCA adapted these components to form a national comprehensive school counseling model to support the holistic success of all students through the use of data and systemic supports (ASCA, 2019; Hines et al., 2020).

Despite this growth in the school counseling profession, what is clear is that even at its best, it is imperfect. From the inception of school counseling, which is situated in American schooling, it remains inherently anti-Black. For example, despite their being school counseling roles in segregated schools, desegregation meant that Black students were pushed into white schools under the assumption that white schools were superior (Smith, 1971). While Black school counselors did exist in Black schools, they were often the first to be pushed out of desegregated schools. As such, Black students became subjected to white school counselors who, more often than not, were “absent from the struggle of Black pupils to obtain their civil rights…simply because the results of their practices have been indistinguishable from the racist practices of the total society” (Smith, 1971, p. 348). While desegregation began nearly 70 years ago, school counseling practices continue to be indistinguishable from racism as counselors continue to overlook, exclude, and render Black youth as nonhuman bodies unworthy of support while perpetuating opportunity gaps and institutional racism (Drake and Oglesby, 2020; Gilmore and Bettis, 2021; Mayes et al., 2021; Washington et al., 2022). Anti-Blackness is particularly evident in the current literature that details the ways in which Black youth indicate the ways school counselors overlook their needs, refuse to work with them, and hold low expectations for their success rather than addressing the institutional policies and systems that trouble the waters (Gilmore and Bettis, 2021; Mayes et al., 2021). Anti-Blackness and the dehumanization of BIPOC students are a part of the troubled history of K-12 schooling which terrorized students through physical and psychological violence including forced assimilation [(Miller, 2017; Gone et al., 2019; Peters, 2019; Austen and Bilefsky, 2021); e.g., residential schools for Indigenous youth, mass graves of Indigenous youth who were murdered in residential schools, inadequate resources and dilapidated structures for schools that serve high minority schools, and the model minority myth and anti-Asian violence]. Further, school counselors often contribute to the policing of Black students through the implementation of comprehensive school counseling programs that center on compliance and whiteness rather than civic engagement and liberation from oppressive systems and policies (Atkins and Oglesby, 2019; Love, 2019; Drake and Oglesby, 2020).

We ought not to be surprised, then, that a field with beginnings steeped in white supremacy, racism, and sexism still operates in the same fashion to disenfranchise and excludes minoritized students, especially Black and brown children and adolescents (Atkins and Oglesby, 2019; Drake and Oglesby, 2020; Gilmore and Bettis, 2021; Mayes et al., 2021; Washington et al., 2022, etc.). Rather than being limited by the current system and its shortcomings, it is important to engage a radical imagination of what could be. Said differently, how might we invite the limitless possibilities of freedom dreaming to the center of the school counseling profession? Freedom dreaming is an opportunity to envision what could be without the constraints of what is, a way forward that centers intersectional Black joy, excellence, community, restoration, and resistance (Kelley, 2003; Love, 2019; Carey, 2020).

Antiracism and freedom dreaming in school counseling

As previously mentioned, school counseling history is riddled with exclusionary and discriminatory practices despite shifts in the profession. However, school counseling need not be limited by its own history but rather liberate that history through the radical imagination of freedom dreaming to envision limitless possibilities. What is needed, then, is an understanding of both antiracism and freedom dreaming to guide this process to not only envision possibilities but also to work toward such.

Antiracism in school counseling

While antiracism is not a new concept, it was more formally introduced into the field of professional school counseling following the gruesome murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in April 2020. While this murder was not the first of state-sanctioned violence against BIPOC individuals, in particular, Black individuals, it sparked a racial reckoning that made real the often ignored racist realities that BIPOC face. With racist realities front and center, many individuals, including educators and school counselors, turned a critical eye toward their own practices and commitments to equity and social justice in their respective spaces. According to the EdWeek Research Center (2020), after the spring/summer of 2020, Black lives matter protests, more educators, especially white educators, were better able to see how schools were ineffective in bridging equity gaps. Further, while most educators identified themselves as antiracist/abolitionist and also were at least somewhat willing to teach/support the implementation of an antiracist curriculum, they also lacked training and resources to support such (EdWeek Research Center, 2020).

Foundationally critical on the path to antiracist school counseling is the work of Holcomb-McCoy (2007, 2022a), who called for professional school counselors to center social justice as a part of their work. As such, Holcomb-McCoy (2007, 2022a) provided a framework for social justice school counseling that highlighted the ways that students are impacted by systemic oppression and provided a pathway for school counselors to address such through culturally responsive practices. This framework included six components: counseling and intervention planning; consultation; school, community, and family partnership; collecting and using data; confronting and challenging bias; and coordinating student services and supports (Holcomb-McCoy, 2007, 2022a). These components provided a lens to which school counselors could not only understand systemic issues both inside and outside of school but also a framework to which school counselors could engage said system to work more comprehensively to remove barriers in order to support the success of all students.

While social justice and antiracism are not the same, antiracism builds on the work of social justice (Holcomb-McCoy, 2022b). In particular, antiracism in school counseling intentionally focuses not only on understanding the intersectional nature of racism (i.e., racism and ableism, racism and sexism) and its impact on policies and practices in K-12 schools but also calls for school counselors to proactively dismantle such while building new policies and practices that center the humanity of minoritized students (Holcomb-McCoy, 2022a,b; Mayes and Byrd, 2022). At its very core, antiracism involves an ongoing engagement with the following practices: (a) we must acknowledge that racism is real and present in all systems of society, (b) we must unlearn colonized ways of being and knowing, (c) we must learn about the roots of racism and understand the intersectional nature of oppression, (d) we must actively address our own internalized oppression and racist behaviors, (e) we must challenge ways of knowing and doing that has been normalized, (f) we must center critical theories as a way to develop our understanding and skills in identifying oppression, and (g) we must actively engage in dismantling oppressive beliefs, policies, and practices wherever we may encounter them (Bell, 1992; Kishimoto, 2018; Williams et al., 2021). As this is an ongoing engagement, antiracism calls for individuals to perpetually engage in these practices as a lifetime commitment rather than a one-time event in one's life.

In relation to school counseling, Mayes and Byrd (2022) describe how the aforementioned practices are foundational to antiracist comprehensive school counseling practice. In particular, Mayes and Byrd (2022) discuss the need for critical consciousness informed by Critical Race Theory (Ladson-Billings and Tate, 1995) and Ecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1992) to understand the ways in which intersectional racism is pervasive across multiple systems and subsystems and how such can impact the development of children, adolescents, and their families. In response to this understanding, Mayes and Byrd (2022) suggest that school counselors work to “love and protect” students through practices that create and build a homeplace (hooks, 1990), which supports the humanity, healing, and growth of students while also centering their joy, excellence, empowerment, and resistance to the dehumanizing sociopolitical context that exists outside of that space. It is important to note that homeplace guides not only the school counseling environment including relationships but also informs the curriculum. Using homeplace as a guide, Mayes and Byrd (2022) also charge school counselors to dismantle harmful policies and practices (i.e., discipline practices, dress code policies, and enrollment policies for rigorous courses) that perpetuate oppression and are a threat to homeplace. In the process of dismantling these policies and practices, school counselors should work collaboratively with educational stakeholders, including students and families, to build new policies and practices that create and sustain homeplace (hooks, 1990).

Freedom dreaming

Closely related to antiracist school counseling practice is the concept of freedom dreaming. Freedom dreaming, as a practice, calls for children, especially Black children to matter, not only just to themselves, but also to their families, the community, and the larger society in a way that demands “the impossible by refusing injustice and … disposability” (Love, 2019, p. 7). Essentially, freedom dreaming engages a radical imagination that recognizes and catalyzes by the struggle for change while working toward a new future where humanity is restored and freedom, liberation, and joy are centered. This new future is not bound by the current sociopolitical and historical context of systems of oppression but rather embraces the creative capacities needed to focus on the possibilities rather than rationality (Kelley, 2003).

Beyond tapping into creative capacities, it is important to understand the collective nature of freedom dreaming. It is not about one person's vision, but rather, how we as a people engage our collective radical imagination to create and work toward a new vision, a new future together (Kelley, 2003). For example, in educational settings, administrators, educators, school counselors, students, and families should work together to not only dismantle inequitable policies and practices but to also collectively reimagine and rebuild a school that “truly loves all children and sees schools as children's homeplaces, where students are encouraged to give this world hell” (Love, 2019, p. 102).

The connection between antiracist school counseling practice and freedom dreaming cannot be overlooked. If a radical imagination is needed for freedom dream that radical imagination cannot be cultivated without homeplaces, without spaces of respite that center humanity, resistance, and joy. Homeplaces allow for protection from a harsh world and remind everyone, especially Black youth, of their human irreducibility, wholeness, and creativity (hooks, 1990). Said differently, homeplaces recognize the pain of oppression while also understanding that students are always more than their pain (hooks, 1990; Love, 2019). In fact, homeplaces intentionally recognize creativity, power, radical love, and joy can and do exist for students in spite of living a world set on their destruction. This creativity, power, love, and joy are critical as students engage their capacity for freedom dream as they create their blueprint for resistance while they work toward a new future (hooks, 1990; Love, 2019).

Antiracist school counseling practices to promote freedom dreaming

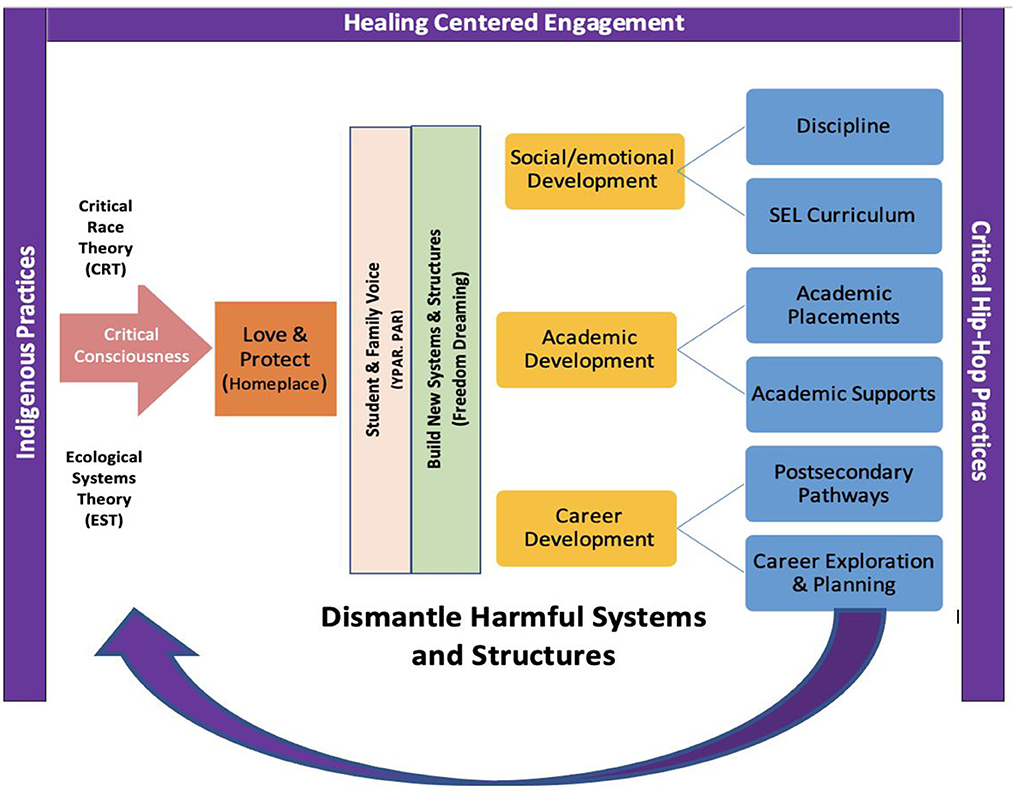

At the intersection of antiracist schooling and freedom dreaming is the shift to holistic healing in schools that not only takes into account the current collective knowledge but also honors ancestral knowledge as a pathway forward (see Figure 1). Practices outlined below center this collective and ancestral knowledge as a means to not only create homeplaces for students but also cultivate the radical imagination and action necessary for freedom dreaming (hooks, 1990; Kelley, 2003). As such, these practices move away from the typical white supremacist status quo of school counseling to embrace Healing Centered Engagement. Healing Centered Engagement (Ginwright, 2018) is an asset-based and political framework that allows school counselors to rethink approaches for creating communities of healing, resilience, joy, and growth. Ginwright poses questions that align healing-centered engagement to freedom dreaming in school counseling: (1) How do we think about the environment where youth live, play, and work?; (2) How might the environment impact on our own well-being and well-being of others?”; and (3) “What's right with students? In reflection on those questions, it poses another question influenced by Mayes and Byrd (2022), how does the profession unlearn colonized systematic ways of school counseling to promote freedom dreaming?.

Figure 1. Freedom dreaming in school counseling. Adapted from: Mayes and Byrd (2022) antiracist school counseling framework.

Revisiting indigenous education and healing practices

Below we describe educational and healing practices guided by Indigenous nations in the United States (e.g., Lenape-Leni, Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas). However, it is important to note that while the discussion below describes educational and healing practices collectively, each nation possesses its own unique culture and practices. The United States government and educational system are still attempting to reconcile with the massive intergenerational damage that many Native American children and families endured when forced to assimilate into Western Culture, specifically at boarding schools (Gone et al., 2019), another indication of the educational foundation created to promote white supremacy. In naming and examining the cruelty of colonization to Indigenous populations, there are many Indigenous healing and educational practices that school counseling can learn from as antiracist practices in order to promote freedom dreaming. Similarly, to the essence of antiracist school counseling, Indigenous populations center holistic traditions on healing, connecting, and regenerating trust, rather than punishing, disconnecting, and furthering distrust (Ross, 2014). Antiracist school counseling promotes, celebrates, and centers students' culture, voice, identities, and ancestral knowledge in the development process. For the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (called by the colonizers as the League of five nations), law, society, and nature are equal partners, and each plays an important role when blending the law (e.g., policies) and values. In the spirit of a systemic lens and approach in school counseling, creating and sustaining homeplace (hooks, 1990) (also referred to as commonplace in some Indigenous cultures) should be the essential value that shapes all comprehensive programming and policymaking with a focus on BIPOC students, especially Black youth.

In working toward decolonizing and freedom dreaming, school counseling must build upon the notion of homeplace (hooks, 1990) with an inclusive focus that engages the school-family-community partnership in sustaining a community of collective learning and collective healing. One way to view this is through the Indigenous concept of preparing for “seventh generation.” Indigenous cultures believe that we borrow the earth from our children's children, and it is our duty to protect it and the culture for future generations. Essentially, all decisions are made with the future generations, who will inherit the earth, in mind. Building a homeplace (hooks, 1990) with this central focus allows the community to engage in a way that fosters learning, growth, empowerment, and development by creating a physical and metaphoric space of care and regard for others, central to celebrating love and joy. Given today's rapidly changing global climate shift and the increasing need for collective healing, protecting the environment for future generations becomes a unifying way for the community to continually reflect on the consequences of collective and individual relations and actions. It models for students the idea that in taking care of both the earth and our own healing, we are creating a better and just world for the future, while simultaneously respecting and incorporating ancestral homage.

Educational practices

Freedom dreaming in school counseling asks “what happens when you center and celebrate a person's language, cultural traditions, familial and ancestral connections, and cultural pride in academic learning?” Indigenous educational processes reflect a sophisticated ecology of education in alignment with developmental counseling. More specifically, education is the understanding of knowing and being through ongoing ways of learning both formally inside and outside the classroom (Pratt et al., 2018). One of the most important elements of Indigenous teaching and learning revolves around “learning how to learn,” a key element in every approach to education. In each phase of learning along with the ecological continuum, learning how to learn is an internalized process. School counselors are tasked with promoting healthy identities, specifically academic identity, however, the internalization of students in today's schools can be harmful to Black youth students, especially with internalized oppression. To empower positive internalization, there are strategies to consider from tribal societies that school counselors can utilize for academic identity development. First, emphasizing “willingness to learn” (as opposed to readiness; Cajete, 1994) is a part of the process. “Readiness to learn” and “career and college readiness,” language often used in educational spaces, uphold internalized deficit thinking. Celebrating and normalizing students' unique individual learning preferences by exposing youth early on to specific academic, emotional, and spiritual tools (e.g., foot swing, visuals, text to speech, and emotional support stuffed animal) that could aid in their learning regardless of subject. Early exposure encourages the development of self-reliance and self-determination also present in indigenous educational practices (Cajete, 1994). By learning how one best learns and what one needs to operate in a homeplace (hooks, 1990), allows students the freedom to advocate for tools, while dismantling a system that waits for their failure to engage in an interventional process that might present them with similar tools.

Healing practices

As schools are working toward collective healing, there is a shift in responsibility for teaching and empowering students' social–emotional development. Historically, school counselors and early childhood educators were responsible, and since the onset of the pandemic, all teachers and staff are expected to teach social–emotional learning. Freedom dreaming for school counseling questions, “what are innovative ways to help students heal?” One of the first shifts is to revisit the term wellness. Indigenous cultures (origins from the Ojibwe nation) describe wellness as a holistic concept that includes physical, social, emotional, cultural, and spiritual well-being, for both the individual and the community (Gee et al., 2014). Wellness emphasizes the connectedness between these factors and recognizes the impact that social and cultural determinants have on health including the impact of colonization that perpetuates racism, sexism, and homophobia. Further described as the alignment of the four aspects of being: the mind (thoughts, concepts, ideas, habits, and discipline), body (air, water, food, shelter, clothing, and exercise), emotions (recognition, acceptance, understanding, love, privacy, discipline, and limits), and spirit (a sense of connectedness, purpose). To be in a good state of overall health, individuals must have an awareness of how they interconnect and relate to one another to operate in harmony. Specifically speaking to spirituality, schools are colonized to reject all aspects of spiritual practices (e.g., yoga, religion, celebrations, and nature), although there are many Christian influences seen in school spaces during holidays and ongoing throughout the year. When schools talk about wanting to partner with BIPOC communities through churches and religious organizations, it is self-serving and performative to gain access and resources on behalf of students, rather than seeking to understand how the beliefs and values impact BIPOC students, families, and school communities in their overall wellness. Denying access to one's central core being, connectedness to others, and a greater purpose disables BIPOC students and families from utilizing the community's strengths to support all aspects of development and wellness.

Freedom dreaming in school counseling seeks to co-create with communities, inclusive homeplaces that center and value spiritual practices, often seen as healing practices, where students can be loved, celebrated, guided, and protected (hooks, 1990). This requires openness to allowing students to have input on creating multiple spaces that align with one's self where spirituality may be visible through creative arts, nature, songs, prayer, meditation, healing circles, music, movement, science creation, and dance. These school communal spaces are also inviting family and community to contribute to the healing energy. Equivalent to the allowance of “brain breaks” in schools, these spaces allow students to utilize culturally relevant coping skills through seeking, developing, and celebrating a sense of self. For example, a school counselor and BIPOC students, with support from the administration, co-created a recording studio to create a space that students can visit throughout the day to process emotions through song and/or hip-hop beats creation. The students reported feeling belonging, connectedness, and wanting to share with others how useful the space is to their overall wellness (Levy and Adjapong, 2020). In doing so, they saw themselves for what they created, continue to create, and how this practice helps fulfill their spiritual sense and increases motivation to continue to learn. While this may not be a practice helpful for all students, it allows other students to see that they have opportunities to co-create spaces that speak to who they are and what assists themselves in times of healing and provide that knowledge to other peers. Co-creating inclusive spiritual spaces and sharing practices may also be considered Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR).

Youth participatory action research in school counseling

In a similar vein to better understand how students' best learn, Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR), puts youth in the hands of developing their educational experience by co-collaborating on the development of solutions to problems that directly impact youth in schools. In the traditional classroom, students are constrained to learning state-sanctioned curriculum in the way that most suits the teachers and often centers on colonized ways of knowing. Unlike the traditional educational framework, YPAR is a framework where both teachers and students are actively learning from each other, working to co-construct knowledge in a learning environment that is intentionally created by members of the classroom. YPAR emphasizes the traditions of freedom dreaming, by encouraging youth and adults to collaborate as equals in changing schools to be homeplaces (hooks, 1990) for youth, developing spaces that value students' various identities. Students are experts in their experiences and how systems impact their worldviews. As a critical pedagogy, educators have used YPAR to liberate the traditional classroom structure. This liberation of the traditional classroom structure allows not only for an understanding and effort to address institutional racism both experienced and observed by students and teachers but also leaning into existence beyond the pain of racism and into radical possibilities.

YPAR projects help youth develop skills to critically reflect and to creatively apply their knowledge to produce change also thought of as critical consciousness (Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Cammarota and Romero, 2011). Students engage in an investigative process that promotes an egalitarian approach to building solutions within the education sector (Rodriguez and Brown, 2009). YPAR is an approach to research where youth co-collaborate as researchers to investigate and address, or even dismantle, issues directly impacting them which includes intersectional racism (Langhout and Thomas, 2010). Foundationally, YPAR methodologists assume that those impacted by an issue would hold expertise about their own community, and therefore, would be the best researchers to resolve the problem (Rodriguez and Brown, 2009). Projects focus on the social contexts that may limit opportunities for youth to be successful, especially in an educational environment (Cammarota and Romero, 2011). At the end of their research process, youth present their findings and actionable recommendations to eradicate the issue they have researched. The adults, or group of adults, serve as a support and guide to help youth lead the research project, namely by providing them with tools they may need to conduct research and using their power and influence to provide spaces for youth to share their findings with decision-makers who can create change (Ozer et al., 2013). YPAR participants have shared that the process has facilitated active engagement in their community and fostered their confidence in their voice being included in decisions (Foster-Fishman et al., 2005; Wang, 2006). Additionally, YPAR participants contribute culturally relevant considerations to inform systemic decisions made for their community. YPAR can help raise students' critical consciousness and belief that they can change circumstances that affect their ability to succeed in school and their social context (Cammarota and Romero, 2006). YPAR can also narrow the power differences between school counselors and their students. Students positively impact their school and students can see how their school counselors hold respect for their cultural identity by including them in discussions related to schoolwide policy shifts (Wang, 2006).

School counselors are cultural liaisons between educators and families (Portman, 2009). As such, school counselors can partner with youth to develop policies, procedures, and practices through the use of YPAR that align with youths' perceptions of their needs. If youth led their school counseling experience, where the school counselor and Black students worked together to identify gaps in support for Black youth, school counselors could shape their programs to actively engage in dismantling oppressive beliefs, policies, and practices while supporting the systemic and personal needs of their youth. School counselors could also use their role as school leaders to include spaces in policy and procedure changes for youth to express their needs to those who have the formal power to create systemic change in schools.

YPAR as a healing practice

Students not only inform changes in the school through their research but also process their experiences with the problem being researched. Thus, YPAR can also help heal students who have been harmed by schools. Love (2019) described wellness as a choice that Black youth make, in spite of the injustices and harm caused by racism and discrimination they endure regularly. When the systems, in this case, educational systems, do not seem to care about or value Black youth, Black youth must find spaces where they can center Black joy and Black love on their own. Centering this idea of wellness marries with the facilitation of YPAR. YPAR requires youth and facilitators to imagine what they want their schools to look like while providing space to process the harm done because of racism (Cammarota and Fine, 2008). Traditionally, small group counseling led by school counselors naturally has space to process and heal. YPAR groups not only provide the space for catharsis but also allow Black youth to engage in systemic change through the dissemination of products that highlight the solutions they create to eradicate the social ills they see occurring in K-12 education.

School counselors are typically trained in microskills used to support youth as they heal and group facilitation, that is, ways to support small groups of students as they process their shared experiences to heal and grow. Because of this training, school counselors can support youth participants as they research issues directly related to them in both their ability to conduct research (academic and career development) and their processing of the harm endured from the problem being researched. As previously mentioned above, Black youth have endured racism, discrimination, and trauma from the white supremacy baked into educational systems. YPAR can provide school counselors with tools to help undo the policies that perpetuate white supremacy, bring a partnership between youth and adults to schools, and help students heal from the past traumas of discriminatory practices in education.

Critical hip-hop practices

Hip-hop culture, broadly defined, encompasses myriad distinct and overlapping belief systems (e.g., peace, love, and having fun), customs (e.g., rapping, djing, and education/enlightenment), and values developed, primarily, by people of African ancestry who were scattered and displaced across the African diaspora as a consequence of European colonization and the African Maafa otherwise known as the transatlantic slave trade. In this country, however, the Bronx, NY is widely considered the epicenter from which hip-hop emerged and burgeoned into a global phenomenon.

Hip-hop culture has become extremely relevant to the landscape of professional school counseling, especially within the past 20 years. The emergence of hip-hop culture in counseling, as an analytical framework with an array of potentially powerful clinical applications, was fostered by the proliferation of the multicultural counseling discourse and multicultural counseling frameworks. Hip-hop culture was considered a culturally appropriate resource that could be strategically integrated into counseling interactions with culturally, racially, and ethnically “different” clients to foster the therapeutic alliance (Day-Vines and Day-Hairston, 2005; Washington, 2018). At that juncture, hip-hop was viewed primarily as an overlooked and undervalued resource that would empower and enable clients from marginalized backgrounds to articulate truths, without compromise or in a way that felt culturally invalidating.

Recently, though, counselors and counselor educators who engage hip-hop in their work have adamantly championed the use of hip-hop culture to critically interrogate systems of power that perpetuate institutional racism and oppression. The nature of this work is not only to simply amplify students' voices but also to invite students to wield the indomitable nature of hip-hop culture to expose how systems that are already imbued with tremendous power (K-12 schooling) reinscribe preexisting narratives about students who are routinely racialized as “other” (Washington, 2021). This emphasis on critical interrogation and consciousness raising among students who suffer unrelenting racialization, inside and outside of school, is central to what has been described as critical hip-hop school counseling (Washington, 2021). Critical hip-hop school counseling aligns beautifully with the mission of antiracism and freedom dreaming (Kelley, 2003), the desire to both understand and abolish the legacies of slavery and racism that linger within K-12 education (Love, 2019), as well as the realization that Black children exist as fugitives within educational environments that are calibrated around surveillance and captivity [(Givens, 2019, 2021); e.g., police assigned to schools]. Critical hip-hop practices, then, do not only celebrate but also implore students to use languages that honor their cultures; critical hip-hop practices also encourage students to weaponize that language as a device to dissect predominant discourses about success and achievement, for instance, that attribute success and achievement to intrinsic characteristics (e.g., mindsets and behaviors) rather than predictable outcomes one would expect from a racially stratified society. In short, critical hip-hop practices are meant to reaffirm to racialized students that the social world is malleable and that they do not have to resign themselves to accepting their place in it (Freire, 1985).

Conclusion

While school counseling historically has been riddled with anti-Blackness and harm toward BIPOC students, the aforementioned practices offer a pathway toward liberation and freedom dreaming. This is particularly important as the current climate shows a continued hostility toward minoritized students, especially Black youth. Anti-LGBTQ legislation (i.e., Florida HB 1557 -“Don't Say Gay Bill”), Anti-SEL legislation (i.e. Oklahoma SB 1442), Anti-school counseling legislation (i.e. Alabama HB 457), and even Anti-CRT legislation (i.e., Texas HB 3979) make it increasingly difficult for K-12 school professionals including school counselors to both see and serve Black youth holistically. More specifically, Anti-CRT legislation makes it such that the racial histories and realities that students and their families face are essentially erased for fear of white discomfort. Taken all together, schools continue to center colonized ways of thinking and knowing at the expense of the humanity of BIPOC children, especially Black youth.

To further complicate the impact of legislative harm, students are still reeling from the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only have there been substantial shifts in schooling and school-based service delivery, but also the impact of COVID-19 on Black youth and families exacerbates already existing structural and institutional racism. For example, Black youth and families are often mistreated in the U.S. healthcare system and are at an increased risk for economic instability due to racism not only in employment but also in housing (Hoffman et al., 2016; Do et al., 2019; Dorn et al., 2020). While the pandemic did not create such disparities, it exacerbates the effects of such and contributes to the already present mental health concerns of living in an anti-Black society (Do et al., 2019; Center for Disease Control, 2021).

It is clear that there is a great need for school professionals, including school counselors, to understand and address the needs of Black youth, especially in the current sociopolitical and historical context. As school counselors incorporate an antiracist lens to their work and practices that center the collective healing, knowledge, and action of students, they can offer respite from such legislation and related policies and practices that continue to harm students. This respite not only provides needed protection but also centers the voices and strengths of Black youth to engage in freedom dreaming. By engaging in healing-centered and critical hip-hop practices along with Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) in school counseling, school counselors center the power and creativity of students needed for freedom dreaming. This freedom dreaming can push beyond the limits of the current moment and provide vision and action toward the future that collectively should be created.

Author contributions

RM provided overall leadership of the manuscript and contributed specifically to the following sections: School counseling history, Antiracism and freedom dreaming in school counseling, Conclusion, and Provided editing for the complete document. NE contributed to the vision of the manuscript and also wrote the introduction and YPAR sections. KI contributed to the vision of the manuscript and also wrote the Revisiting indigenous education and healing practices section. AW contributed to the vision of the manuscript and wrote the section on Critical hip-hop practices. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ASCA (2019). The ASCA National Model: A Framework for School Counseling Programs (4th ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

ASCA (2022). ASCAEthical Standards for School Counselors. Available online at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/44f30280-ffe8-4b41-9ad8-f15909c3d164/EthicalStandards.pdf (accessed June 01, 2022).

Atkins, R., and Oglesby, A. (2019). Interrupting Racism: Equity and Social Justice in School Counseling. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351258920

Austen, I., and Bilefsky, D. (2021). Hundreds More Unmarked Graves Found at Former Residential School in Canada. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/24/world/canada/indigenous-children-graves-saskatchewan-canada.html (accessed June 01, 2022).

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education. Durango, CO: Kivaki Press. p. 585.

Cammarota, J., and Fine, M. (2008). “Youth participatory action research: a pedagogy for transformational resistance,” in Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion, Cammarota, J., and Fine, M.(Eds.). p. 1–12.

Cammarota, J., and Romero, A. (2006). A critically compassionate intellectualism for Latina/o students: raising voices above the silencing in our schools. Multicult. Educ. Stud. 16–24. Available online at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ759647.pdf

Cammarota, J., and Romero, A. (2011). Participatory action research for high school students: Transforming policy, practice, and the personal with social justice education. Educ. Policy. 25, 488–506. doi: 10.1177/0895904810361722

Carey, R. L. (2019). Imagining the comprehensive mattering of Black boys and young men in society and schools: toward a new approach. Harv. Educ. Rev. 89, 370–396. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-89.3.370

Carey, R. L. (2020). Making black boys and young men matter: radical relationships, future oriented imaginaries and other evolving insights for educational research and practice. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 33, 729–744. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2020.1753255

Center for Disease Control (2021). Anxiety and Depression: Household Pulse Survey. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm (accessed June 01, 2022).

Day-Vines, N. L., and Day-Hairston, B. (2005). Culturally congruent strategies for addressing the behavioral needs of urban African American adolescents. Prof. Sch. Couns. 8, 236–243. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42732464

Do, D. P., Locklar, L. R., and Florsheim, P. (2019). Triple jeopardy: the joint impact of racial segregation and neighborhood poverty on the mental health of Black Americans. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54, 533–541. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01654-5

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., and Viruleg, E. (2020). COVID-19 and Student Learning in the United States: The Hurt Could Last a Lifetime. Available online at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime# (accessed June 01, 2022).

Drake, R., and Oglesby, A. (2020). Humanity is not a thing: disrupting white supremacy in K-12 social emotional learning. J. Crit. Rev. 10, 5. doi: 10.31274/jctp.11549

Edirmanasinghe, N. A., Goodman-Scott, E. G., Smith-Durkin, S., and Tarver, S. Z. (2022). Supporting all students: multitiered systems of support from an antiracist and critical race theory lens. Prof. Sch. Couns. 26, 1. doi: 10.1177/2156759X221109154

EdWeek Research Center (2020). Anti-Racist Teaching: What Educators Think. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/anti-racist-teaching-what-educators-really-think/2020/09 (accessed June 01, 2022).

Foster-Fishman, P., Nowell, B., Deacon, Z., Nievar, M. A., and McCann, P. (2005). Using methods that matter: the impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. Am. J. Community Psychol. 36, 275–291. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8626-y

Freire, P. (1985). The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., and Kelly, K. (2014). “Social and emotional wellbeing and mental health: an Aboriginal perspective,” in Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., and Walker, R (eds). Canberra: Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. p. 55–68.

Gilmore, A., and Bettis, P. (2021). “Antiblackness and the adultification of Black children in a U.S. prison nation,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality in Education, Mayo, C. (ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1293

Ginwright, S. (2018). The Future of Healing: Shifting From Trauma Informed Care to Healing-Centered Engagement. Available online at: http://kinshipcarersvictoria.org/2018/08/OP-Ginwright-S-2018-Future-of-healing-care.pdf (accessed June 01, 2022).

Givens, J. R. (2019). “There would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom”: Carter G. Woodson and the occasion of Negro History Week, 1926–1950. Am. Educ. Res. J. 56, 1457–1494. doi: 10.3102/0002831218818454

Givens, J. R. (2021). “Fugitive pedagogy,” in Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, Carter G. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.4159/9780674259102

Gone, J. P., Hartmann, W. E., Pomerville, A., Wendt, D. C., Klem, S. H., and Burrage, R. L. (2019). The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: a systematic review. Am. Psychol. 74, 20. doi: 10.1037/amp0000338

Hannah-Jones, N., Elliot, M., Hughes, J., Silverstein, J., and New York Times Company, Smithsonian Institute. (2019). The 1619 project: New York Times magazine. Manhattan, NY: New York Times.

Hines, E. M., Moore, I. I. I., Mayes, R. D., Harris, P. C., Vega, D., Robinson, D. V., et al. (2020). Making student achievement a priority: the role of school counselors in turnaround schools. Urban Edu. 55, 216–237. doi: 10.1177/0042085916685761

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., and Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and Whites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 4296–4301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113

Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2007). School Counseling to Close the Achievement Gap: A Social Justice Framework for Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2022a). School Counseling to Close Opportunity Gaps: A Social Justice and Antiracist Framework for Success (2ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2022b). “The pathway to antiracism: Defining moments in counseling history,” in Antiracist Counseling in Schools and Communities, Holcomb-McCoy, C.(Ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. p. 1–16.

Kishimoto, K. (2018). Anti-racist pedagogy: from faculty's self-reflection to organizing within and beyond the classroom. Race Ethn. Educ. 21, 540–554. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2016.1248824

Ladson-Billings, G., and Tate, W. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 97, 47–68. doi: 10.1177/016146819509700104

Langhout, R. D., and Thomas, E. (2010). Imagining participatory action research in collaboration with children: an introduction. Am. J. Community Psychol. 46, 60–66. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9321-1

Levy, I. P., and Adjapong, E. S. (2020). Toward culturally competent school counseling environments: hip-hop studio construction. Prof. Counselor. 10, 266–284. doi: 10.15241/ipl.10.2.266

Love, B. L. (2019). We Want to do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Mayes, R. D., and Byrd, J. (2022). An antiracist framework for evidence informed school counseling practice. Prof. Sch. Couns. 26, 18–33. doi: 10.1177/2156759X221086740

Mayes, R. D., Lowery, K., Mims, L. C., and Rodman, J. (2021). “I stayed just above the cusp so I was left alone”: black girls experiences with school counselors. High School J. 104, 131–154. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2021.0003

McMahon, H. G., Mason, E. C. M., Daluga-Guenthner, N., and Ruiz, A. (2014). An ecological model of professional school counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 92, 459–471. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00172.x

Miller, J. R. (2017). “Reading photographs, reading voices: Documenting the history of Native residential schools,” in Reflections on Native-Newcomer Relations. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto. p. 82–104.

National Center for Transforming School Counseling. (n.d.). The New Vision for School Counselors: Scope of the Work. Available online at: https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/TSC-New-Vision-for-School-Counselors.pdf (accessed June 01 2022).

Ozer, E. J., Newlan, S., Douglas, L., and Hubbard, E. (2013). “Bounded” empowerment: Analyzing tensions in the practice of youth-led participatory research in urban public schools. Am. J. Community Psychol. 52, 13–26. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9573-7

Peters, A. L. (2019). “Desegregation and the (dis)integration of Black school leaders: reflections on the impact of Brown v. Board of Education on Black education. Peabody J. Educ. 94, 521–534. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2019.1668207

Portman, T. A. A. (2009). Faces of the future: school counselors as cultural mediators. J. Couns. Dev. 87, 21–27. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00545.x

Pratt, Y. P., Louie, D. W., Hanson, A. J., and Ottmann, J. (2018). “Indigenous education and decolonization,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.240

Rodriguez, L. F., and Brown, T. M. (2009). From voice to agency: guiding principles for participatory action research with youth. New Directions for Youth Dev. 123, 19–34. doi: 10.1002/yd.312

Schwartz, S. (2021). “Map: Where critical race theory is under attack,” in Education Week. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/map-where-critical-race-theory-is-under-attack/2021/06 (accessed June 01, 2022).

Smith, P. M. (1971). The role of the guidance counselor in the desegregation process. J. Negro. Educ. 40, 347–351. doi: 10.2307/2967046

Stephens, D. L., and Lindsey, R. B. (2011). Culturally Proficient Collaboration: Use and Misuse of School Counselors. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin SAGE. doi: 10.4135/9781483387406

Wang, C. (2006). Youth participation in Photovoice as a strategy for community change. J. Community Pract. 14, 147–161. doi: 10.1300/J125v14n01_09

Washington, A. R. (2018). Integrating hip-hop culture and rap music into social justice counseling with Black males. J. Couns. Dev. 96, 97–105. doi: 10.1002/jcad.12181

Washington, A. R. (2021). Using a critical hip-hop school counseling framework to promote Black consciousness among Black boys. Prof. Sch. Couns. 25, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/2156759X211040039

Washington, A. R., Byrd, J. A., and Williams, J. (2022). “Decolonizing the counselor canon,” in Antiracist Counseling in Schools and Communities, Holcomb-McCoy, C. (Ed.). p. 17–31. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Keywords: freedom dreaming, school counseling, antiracism, Black joy, liberation

Citation: Mayes RD, Edirmanasinghe N, Ieva K and Washington AR (2022) Liberatory school counseling practices to promote freedom dreaming for Black youth. Front. Educ. 7:964490. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.964490

Received: 08 June 2022; Accepted: 22 November 2022;

Published: 13 December 2022.

Edited by:

Misha Inniss-Thompson, Cornell University, United StatesReviewed by:

Roderick Carey, University of Delaware, United StatesAddison Duane, University of California, Berkeley, United States

Cierra Kaler-Jones, University of Maryland, United States

Copyright © 2022 Mayes, Edirmanasinghe, Ieva and Washington. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renae D. Mayes, cmRtYXllc0Bhcml6b25hLmVkdQ==

Renae D. Mayes

Renae D. Mayes Natalie Edirmanasinghe

Natalie Edirmanasinghe Kara Ieva

Kara Ieva Ahmad R. Washington

Ahmad R. Washington