Factors contributing to university dropout: a review

- Faculty of Education and Sports Sciences, University of Granada, Melilla, Spain

Introduction: Dropout is one of the problems that the university education system has to face every year. The educational community is involved in the reasons for its trajectory as a social problem, which does not exempt any student in the world. Its study and improvement of the education system is a key element in changing the course of university dropout and alleviating its rapid growth in society.

Methodology: Using a quantitative and qualitative methodology, an attempt is made to provide answers to the objectives pursued by the research.

Objectives: To analyze student satisfaction, to specify the causes of dropout, and to determine the most appropriate authors on dropout by means of literature and different databases.

Conclusions: It is concluded that, are five main major components would be behind university dropout: student adaptation, personality, socio-economic level, teacher–student relationship, and quality in university education. With them come certain sub-causes that must be taken into account for a better understanding of the reasons for university dropout, such as demotivation, low self-esteem, frustration, pregnancy, among others, reasons why their study is essential for their future eradication.

1. Introduction

University dropout is a phenomenon, as distinguished as it is problematic, worldwide due to its high dropout rates. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2019) reports that 20% of students who start tertiary studies fail to complete them. According to the latest statistics published by Eurostat (2020), Malta is the country with the highest university dropout rate with 18.4%, followed by Spain with 18.3%, and, in third place, Romania with 18.1%. If we examine the percentage of students who drop out of a Bachelor's degree, we can see that this percentage is increasing significantly, which is a problem. In the latest report published by the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (MEFP, 2019), 30% of students drop out of Spanish universities, mainly during the first year of studies. The dropout rate in the first year of a Bachelor's degree, of the new 2014–2015 cohort, stands at 21.5%.

In this regard, in Spain, specifically in Andalusia, recent reports such as the one published by the Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF, 2020) show that the university dropout rate in Andalusia is considerably higher than the average for the Spanish university system as a whole. The above data, which are worrying if we bear in mind that European institutions set themselves the target of reducing university dropout rates to 10% by 2020, lead to multiple consequences at an academic and structural level in higher education, as well as socio-economic effects, which can be seen in the student body, the university institution, and the State as a whole (Agudo, 2017).

When a student drops out of a degree program, he or she suffers a situation of failure, which causes damage and psychological suffering; a problem that extends to the family environment. Similarly, the university institution is also affected, as the failure of its student's casts doubt on the effectiveness of the teaching staff, the organization of the curriculum, the resources available, etc. On the other hand, for the state, it means instability in the higher education system that affects society as a whole, due to the large economic costs it invests without achieving the expected educational objectives for the population (González et al., 2007).

In times of economic hardship, capital plays a very important role. Therefore, in terms of profitability, investment in education ceases to be profitable if there are high levels of university dropouts (Corominas, 2001).

Martínez (1999) and Carrera and Mazzarella (2001), in their studies, make it possible to go to the heart of the phenomenon and study it in its development. In order to understand and interpret them, special attention must be paid to those agents (teachers, peer groups, and family) who intervene as mediators in the students' decision-making process, in order to know the effectiveness of their actions in solving the problem of university dropout, among other factors that will be presented later in the following sections.

Continuing along these lines, it is worth highlighting the educational scenarios in which university dropout occurs, starting with the types of dropout and the factors that influence them.

Beginning with the fate of students who drop out temporarily, this gives rise to a new classification: internal or external dropout (Elias, 2008).

Internal drop-out occurs when a student who has left a degree program starts other studies at the same institution. In most cases it happens during the first semesters as a consequence of choosing a degree program based on incorrect motivations or not having received adequate guidance before entering university (Torres, 2018; Hernández-Jiménez et al., 2020). However, if the student starts studies at another institution, this generates what is known as external dropout. According to Corominas (2001), the student may continue to remain in the same degree program, although for reasons of internal or external dissatisfaction, or due to life circumstances, he or she moves to another university. It may also happen that the student continues his or her academic training in other types of studies at a lower level than university (training cycles, non-regulated education, etc.).

On the other hand, there may be different situations for the students themselves, especially for new students: It should be emphasized that the student who is taking a degree may have previously abandoned another degree or simply have passed a specific test such as the EBAU. In this sense, a student starting a university program may be in the situation of having to take the whole academic load to obtain the degree or have a part of it validated and, consequently, be able to access a higher course.

At a scientific level, it is necessary to consider both characteristics, although special attention is paid to the most numerous groups, as it is the one that enters the university system without having previously left another degree and, therefore, does not have any validated subjects. Project Alpha Guide, DCI-ALA/2010/94 (2013) corroborates that, given the difficulty of accurately selecting the group of students who have previously abandoned a university degree, work is done on the students of a new entry cohort, defined as: “The group of students who enroll for the first time in the first year (semester) of the degree course (degree) T at the University U in the academic period X” (p. 13). However, with the intention of showing the positive side of the phenomenon to future newcomers to the system, studies on university dropouts could take into consideration this group of students who, after abandoning their studies and redirecting them, manage to redirect their academic trajectory thanks to the option of leaving the Higher Education system internally or externally. In this sense, it can be seen that university dropout is a dynamic phenomenon that is in continuous evolution. As can be observed in the literature, university students can follow multiple trajectories when leaving a higher education degree.

In order to achieve a better understanding of the phenomenon, it is necessary to investigate the theoretical models that have been developed throughout history, as well as their theories. For a better understanding, we will point out the different theories and models that provide the bases and factors that produce this phenomenon in higher education classrooms.

2. Background and theoretical framework

There are several attempts to build theoretical models to explain the phenomenon of university dropout, which is a problem that the current university system has to deal with.

These phenomena not only concern students, but also the teaching staff, the institution, and family members, and in general involve the entire university community. Some authors, such as De Vries et al. (2011), Merlino et al. (2011), and more recent authors such as Álvarez (2021), allude to both voluntary and involuntary factors, causes that may or may not be related to the university community itself, thereby implying a loss of capital for family members, the school/university environment, and the country itself, in addition to the feeling of frustration. Therefore, they relate it to personal causes, such as the motivation of the students themselves and their own academic performance, due to pregnancy or poor integration of the student, lack of motivation and loss of interest in studies, low self-esteem, among others (Merlino et al., 2011; Álvarez, 2021; Lorenzo, 2021).

In this sense, frustration plays a very important role in cases of university dropout, as studies show that 45% of students who have dropped out are due to fear, stress, and difficulties encountered in the content; on the other hand, 51% have been due to physical and mental exhaustion (Vera and Álvarez, 2022). These causes are common among university students, due to the various obligations that the degrees demand, as well as other types of work or social commitments. These causes were raised by authors such as Estrada et al. (2017), which he called academic burnout, where this academic, personal, and mental exhaustion endangers the quality of life and wellbeing of university students.

Although university burnout is more prone to occur at school age, it also occurs in the university environment and its study should be considered, which is not only perceived on a mental level, but also on physical levels such as muscle pain, headaches, or sleep disorders (Vera and Álvarez, 2022). The multiple emotional, mental, and physical causes are present in the university community and their risk is not exempt to any of the students, taking care of motivation, self-esteem, student satisfaction, and satisfaction in their work and themselves are key to personal and emotional development, making it an essential premise in order to keep students in university institutions.

With an emphasis on motivation and academic performance, combating the emotional disturbance produced by the burnout effect is fundamental. There are direct links between the motivation of the student body and the academic performance of students. On the one hand, they have to meet the demands of university courses, which leads to situations of stress, anxiety, etc. (Vera and Álvarez, 2022), directly affecting students' academic performance, demotivating them, and causing them to feel negative and insecure, which ends up leading them to drop out of their studies.

Motivation in students is essential for the achievement of their educational goals and their future attainment of their corresponding degree. This makes it necessary to highlight Maslow's Pyramid (Figure 1), which supports the needs of human beings for their own motivation (Turienzo, 2016).

Firstly, there are the students' basic or physiological needs, food, maintaining their own health, and rest. Next, the need for security, feeling safe and protected, having a job, among others. Social needs, where affective development, association, acceptance, and affection are involved. On the other hand, the need for self-esteem, where we find the recognition of the person, confidence, respect, and success and the one at the top, the need for self-realization, referring to the development of the potential of students, refers to confidence, respect, and self-recognition, this last step has had several problems for its own verification, as indicated by the author Turienzo (2016), this is so because happiness is something that is relative and variable.

Taking this pyramid into account, it is clear how essential it is to motivate students, to consider their needs and not to ignore those signs that can give us clues about their situation, promoting quality education, understanding different scenarios, and avoiding, as far as possible, that students drop out of their careers.

All these factors that affect students on a personal and social level are not only exempt in Spain, it is a worrying issue at a global level, as Lydner (2022) explains in his research, where the problem is reflected throughout the American territory, which ensures that it has been a severe problem for two decades and that it should not be kept as an isolated case. In this case, emotional factors have been one of the main causes, together with feelings of failure and guilt.

In another study by Weinstock (2017), he reiterates some of the statements made above, emphasizing that one of the main causes is depression. The data obtained from 10 US universities and 1,100 first-year students, where depression was one of their first choices for university dropout, caused by the pressure to perform well both academically and in their extracurricular activities. Of all students entering universities in the United States, research shows that twenty-five percent (25%) have achieved the minimum American College Test (ACT) threshold in all four subjects. On average, very few students are able to meet the threshold for all of their high school classes (Polumbo, 2017).

With all these statements, it is important to study the importance of the study, in order to continue to deepen the fundamental role of the education system and the way it combats university dropout, improving and achieving its future eradication.

Looking at the literature, we find that several authors throughout this century have tried to find answers to the causes that lead university students to abandon their academic education.

2.1. Models of university dropout

These models presented by the authors can be distinguished into five main approaches: adaptive models, psycho-pedagogical model, organizational model, economist model, and interactionist model.

- Adaptation or sociological model: family background and personal attributes of the pre-university experience are involved. These characteristics combine to influence commitment to the institution, as well as achieving the ultimate goal of graduation or graduation (Himmel, 2018). This model is underpinned by Durkheim's theories of suicide. Which implies that students break directly with the social system due to their lack of integration in the university community (Viale, 2014). Therefore, this model covers those students who have not adapted and have therefore dropped out of the degree program.

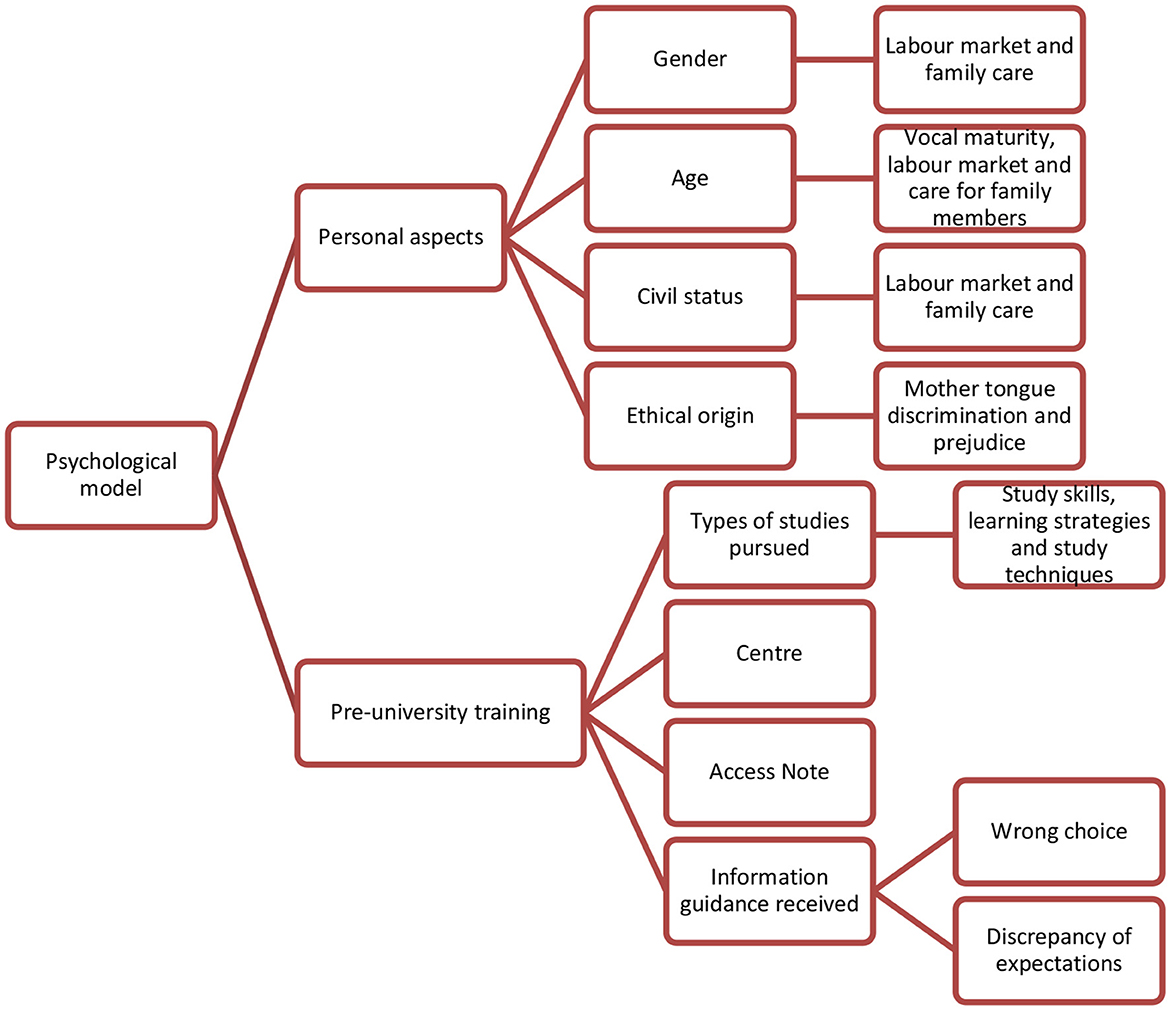

- Psychopedagogical model: the main characteristic of this model refers to the personality traits of university students, distinguishing between those who complete their degree and those who do not. Student failure is determined in this case by the psychological characteristics of the student him/herself.

- Economist model: this model is based on the application of the cost-benefit approach. It argues that the investment of time and money does not always generate social and economic benefits for university students.

- Organizational model: this model argues that dropout depends on the qualities of the organization in social integration, and more particularly on the dropout of the students who enter it. It emphasizes the quality of the teaching and the active learning process in the classroom (Himmel, 2018).

- Interactionalist model: where it is understood that the main reason for university students dropping out lies in the way they interact with their teachers and classmates. Tinto (1987) already started from the idea of interaction between classmates and between teacher and student, since the greater the interaction between these groups, the greater the possibility of students finishing their studies.

Knowing some of the factors associated with dropout and patterns, it is worth highlighting how all these factors could be classified.

On the one hand, there are those related to the students themselves, stressing the importance of age, gender, ethnicity and even the marital status of the students. Al Ghanboosi and Alqahtani (2013), in their studies to discover the dropout variables, look at the data from the explorations published annually in two universities in the United Arab Emirates and the information from the data obtained to determine that university dropout mainly affects younger students, given their low vocational maturity. Notably, 82% of students entering university are under 25 years old (OECD, 2017). Authors such as García de Fanelli (2014), after carrying out a literature review of different sources published between 2002 and 2012, highlight that non-traditional students above the age of 25 also drop out of university. However, the causes of these dropouts are different because they are mainly attributed to the need to allocate time to work and family. In the work of Severiens and Dam (2012), the causes of female dropouts are often attributed to caring for family or children. Men, however, drop out of school in order to enter the world of work. Thus, drop-out can be attributed to the gender of the students. In general terms, research shows that male dropouts prevail over female dropouts, even though the percentage of men enrolled in university is lower (Rodriguez, 2013).

Numerous studies show that certain populations made up of ethnic minorities or specific groups, such as people with difficulties and highly competitive athletes, have a higher risk of dropping out of university (Gairín et al., 2013; Fonseca and García, 2016). It should also be taken into account that belonging to an ethnic group implies having a different mother tongue from the official language in which classes are taught; in other cases, it entails suffering experiences of discrimination and prejudice that have negative consequences not only on learning outcomes, but also on students' social adaptation (Abbate, 2008; Cabrera et al., 2014). Based on this deduction, Planas et al. (2011) point out the importance of promoting tutorial action that contributes to the personalization of education, attending to the integrity of the individual, predicting learning difficulties in studies, and avoiding phenomena such as university dropout as a result of adjusting the educational response to the specific needs of students.

At this point, the aspects inherent to students' pre-university academic training should be pointed out, as they have repercussions on their university careers. In general, not much attention has been paid to the process developed by students prior to dropping out of their studies and the analysis of the factors that influence the intention to drop out has been neglected in order to carry out preventive programs. Reducing university dropout requires a thorough understanding of the phenomenon as a whole, which implies the analysis of academic factors prior to entering university, such as the information received to choose a degree, the university entrance grade, the type of studies taken, and the center of origin. Duque et al. (2013) conducted a quantitative study in three Catalan universities in order to identify the factors that influence the trajectory of students and their relationship with the intention to drop out. The study shows that 51% of students had considered dropping out of their studies at some point, with the most common reasons for dropping out being the wrong choice of degree program and a discrepancy in expectations.

Generally speaking, students have difficulty in making a career choice at 17 or 18 years of age (Nieman, 2013; García, 2014) or do not obtain adequate information to make this important decision (Castejón et al., 2015; García and Adrogué, 2015). In this regard, Silver Wolf et al. (2017) argue that more information and guidance prior to entry could reduce the rate of early dropout. Students who are more likely to drop out in the first year should receive more detailed information about the content of the course to be taught so that high levels of stress and frustration are not generated, which have an unfavorable impact on the decision to stay in their chosen degree program (Meyer and Thomsen, 2018). The choice of a degree program, on the other hand, is influenced by the entrance qualification required by each institution. The entrance qualification is also presented as a variable that influences dropout, as there is a close relationship between prior academic performance and university performance. In fact, there are many studies that confirm that prior academic performance is significantly correlated with performance in university studies, with the highest correlation being found in technical and experimental degrees. According to Puertas Cañaveral and De Oliveira Sá (2017), having higher grades in Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate significantly reduces the risk of dropping out of university.

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the variables that make up the psychological model of university dropout. On closer examination, it can be seen that this model includes each of the personal and inherent aspects of pre-university academic training mentioned above.

Figure 2. Personal and pre-university variables that make up the psychological model of university dropout. Based on Pedraza (2021).

From the sociological model we focus specifically on family aspects. According to Spady (1970), the student's pathway not only depends on the psychological characteristics mentioned above, but is also influenced by external factors such as the family environment, which sometimes hinders the student's integration into the Higher Education system. After reviewing the literature, we observed that the size of the family, the type of housing, the educational and economic level of the parents, the cultural capital, and the presence of difficulties, constitute the family aspects with the greatest influence on university dropout.

Another factor to take into account in university dropout is the educational level of the parents. Stephens et al. (2012), after conducting a principal components study, found that the probability of dropping out of a degree decreases the higher the educational level of the family. The literature reflects the importance of the parents' educational level, particularly the mother's educational level. Marchesi (2000) considers that mothers attach greater importance to academic duties and are more concerned about their children's performance, orienting them toward continuing their studies. Therefore, when mothers' academic level is higher, children perceive greater support for their studies and seek to achieve the goal of graduating.

Previously, Castejón and Pérez (1998) stated that this effect is due to the decision made by fathers to delegate their children's education to their mothers. Closely linked to the parents' educational level is the family's cultural capital. This refers to the set of social positions or assets that it possesses thanks to the right to education, such as the availability of economic resources, access to the internet or family relationships marked by discussions that promote knowledge. All this accumulation of cultural knowledge has a significant influence on students' academic results, favoring adaptation. In this sense, it is worth noting that, in recent decades, access to the Internet has become a powerful cause of inequality (Garbanzo, 2007). People who have economic resources of this type are more prepared to adapt to the knowledge society, as they have a very important added value, which is the possibility of broadening their culture.

Sometimes, students' careers are interrupted by the presence of family difficulties that generate discouragement. Despite their low frequency, there are situations, such as the appearance of an illness or the death of a family member, which lead students to make the decision to abandon their university studies (Rodríguez-Pineda and Zamora-Araya, 2020). In line with Severiens and Dam (2012), students who are more affected by situations of this type are women, as they feel the need to take care of the family. Other family variables associated with female dropouts are pregnancy, childbirth, and marriage.

Finally, through the economistic model, the influence of socio-economic aspects that hinder students' academic development is accentuated. The scientific literature emphasizes the student's purchasing power, their employment situation, the way they finance their studies, the lack of economic resources to cover transport costs, tuition, materials, among others, and family responsibilities in the presence of economic difficulties. In a qualitative analysis of 25 semi-structured interviews, Lehmann (2007) observes that middle-class students experience academic difficulties during their university studies. These difficulties may be the result of a lack of social integration, which causes students to have doubts about their ability to achieve a university degree (Aries and Seider, 2005); or the result of not having sufficient financial resources to pay for the costs of university (Ariño and Llopis, 2011). Fortunately, students who come from affluent families are more likely to pass higher education (MDSyF, 2003), and thus obtain a better employment situation (Lehmann, 2007).

It is worth noting that the opportunities offered by the labor market are not equal for men and women. According to an OECD (2010) statistical report, women with university degrees earn only 71% of what men earn. This results in students' decision-making. Severiens and Dam (2012) state that, in the presence of family difficulties, men enter the labor market earlier than women in order to be able to obtain greater economic benefits. Even without higher education, the economic benefits for men are higher than for women without a university degree (Jacob, 2002; Evers and Mancuso, 2006).

It is true that combining studies with work is a complicated task, as it requires a lot of time. Therefore, the risk of dropout in students who work is higher (Sevilla et al., 2010; Íñiguez et al., 2016). Through an analysis, Castaño et al. (2008) reveal that being financially dependent on oneself as a student increases the risk of dropping out of university. However, working in the last year of the degree does not affect this, and it is possible to combine academic and work responsibilities.

On the other hand, Gury (2011) pays special attention to the number of hours students spend working. After conducting a statistical analysis of historical dropout events in Bolivian Higher Education, the author states that working part-time during the first years of university increases the probability of dropping out, after which it remains insignificant. Those students who support their studies thanks to financial aid from parents or a financial institution are less likely to drop out (Jones-White et al., 2014; Ononye and Bong, 2018). However, if we analyze the scholarship system in Spain, we observe that there is an imbalance between the cost of enrolment and the aid provided by the state. In 2009, the average cost per ECTS credit in Spanish public universities was €13.85, which increased to €18.51 in 2015. This difference of almost €5 meant an increase in tuition fees, from €800 to more than €1,100. Despite this, the amount of study grants remained at the same levels as in the academic year 2006/2007 and only 27% of students received grants (CRUE, 2016).

Moreover, on certain occasions, students who receive a grant do not achieve the average mark required by the administration and are excluded from the criteria to obtain the grant for the next academic year. This fact causes substantial changes in the students, who consider the decision to drop out due to the increase that a new enrolment implies (Sacristán, 2018). The difference becomes greater as the student fails and has to enroll repeatedly in the same subject. But it should be borne in mind that changes in personal and family conditions are strongly associated with socio-economic aspects that influence university dropout. Long et al. (2006) emphasize that unexpected situations such as the loss of the breadwinner's job, the death of the father or the need to enter the world of work are factors that prevent students from continuing their university studies, as they are obliged to support their families. The socio-economic variables referred to above show the vulnerability of various groups of students who do not have a solid family structure to help them alleviate the effects of these variables on their university careers. This situation should be taken into account by educational institutions and government policies on Higher Education, which tend to allocate subsidies to university access and not so much to permanence (Pedraza, 2021).

On the other hand, the variables that depend on the subject and institution itself pay special attention to the characteristics of the curricula, the human, and material resources that institutions possess, the quality of teaching, and the interpersonal relationships that occur in the classroom between students and teachers (Pedraza, 2021). It should be noted that the multiplicity of curricula in different institutions makes it difficult to analyses the organizational variables that interfere with students' university careers (Fonseca and García, 2016). Even so, several authors such as Tejedor and García-Valcárcel (2007) analyses which organizational variables interfere in the academic performance of students belonging to different types of institutions: sciences, biomedical, social sciences, economics-legal, and arts. After carrying out linear combinations between the different variables, the authors observe that the excessive number of subjects that students must take and the 4-month nature of these subjects have an impact on their low performance. Moreover, given the intrinsic difficulty of the subjects and the demands of the teachers, students suffer from stress and anxiety, which generates doubts about their intellectual capacity to successfully complete their chosen degree. Unfortunately, when the number of failures prevails over the number of passes, students decide to drop out rather than extend their study plan over time (Esteban et al., 2017).

On the other hand, the excessive number of assignments and exams throughout the degree increases the level of frustration of students, as it generates too much academic workload that they must combine with their family and work life (Castillo, 2010). Other organizational variables that affect students' academic performance are the lecturer/student ratio, the class schedule and the number of practical classes (Tejedor and García-Valcárcel, 2007). Higher education institutions should create spaces where teachers can meet with students, give them feedback on the academic activities developed and produce new activities that allow them to apply knowledge to concrete situations in order to favor the creation of academic and social networks that help to improve the educational climate. Actions of this kind are essential during the first year of studies. Students entering university for the first time tend to suffer from “academic shock” due to the change between high school and university. Along these lines, university classes are dedicated to instruction, students have to organize their studies on their own, manage their time and academic resources, as well as combine their academic life with outside activities or work (Lorenzo and Zaragoza, 2010).

Tejedor and García-Valcárcel (2007) point out that the lack of individualized treatment, pedagogical deficiencies, the development of inadequate activities, the lack of clarity of exposition, the lack of information on assessment criteria and the poor use of didactic resources are factors inherent to teachers, which determine the poor university performance of students. It is therefore advisable for teachers to provide information about the assignments and exams to be developed, to comply with the assessment criteria and to leave aside subjectivity in marking. Tutoring and educational guidance sessions throughout the university stage allow students to develop intellectual skills that favor their academic performance (Doerschuk et al., 2016). This support should be provided by teaching staff who are able to interact with students (Lázaro, 2003) and/or upper-level university students who are able to create supportive relationships (Mori, 2012). It should be noted that peer support is a process of accompaniment that helps to overcome fears, frustrations, anxieties, or other barriers that prevent the correct development of university life.

Therefore, many studies have tried to analyze the individual, social, economic, and institutional variables that influence the final decision to drop out (García and Adrogué, 2015). Most impact scientific research has focused on variables such as students' academic and professional expectations (Díaz et al., 2019), integration into their new educational environment (Bernardo et al., 2016), socioeconomic circumstances of the students and their families (Sosu and Pheunpha, 2019), and finally the academic performance. This is one of the most prominent variables in the scientific literature (Gutierrez et al., 2015).

2.2. Dropout prevention and strategies from school to higher education

Given the high dropout rates at universities, many schools and faculties have adopted and implemented various dropout prevention strategies and programs. This topic has been studied for the last two decades and numerous plans and programs have been proposed, in addition to other types of avenues being explored to curb the problem.

Many of these programs have been developed to anticipate the key to student dropout and poor or non-attendance. However, in the literature, the authors are those who priorities addressing these issues before arrival in the classroom or at the beginning of higher education, where such tests are very effective and give results that show a reduction in dropout rates in students. On the other hand, more personalized tests have been proven to be more successful in the long term (Cerda-Navarro et al., 2017).

Other ways suggested by the authors Huntington and Gill (2020), are to reduce drop-out rates among students by tutoring them in those subjects that best suit their potential. Thus, offering them greater counseling for those who want it.

On the other hand, several authors argue that such monitoring should be considered before students reach higher education, creating, and attempting to remedy dropout by early identification of any factors associated with the potential for dropout.

“Through personalization of education, teachers and the academic body as a whole must work together to increase the chances of success in students' academic pursuits while creating a supportive and caring learning environment” (Cholewa and Ramaswami, 2015, p. 206).

This would not only involve the student, but also implies that teachers help in the resolution of personal problems they may face. These solutions also lie with the family (Terry, 2008), where good family support and family involvement are key determinants of the choices students make. Poor support from teachers or parents often encourages students' disdain and increases their willingness to drop out of school.

3. Objectives

In view of the above, the following objectives are proposed:

3.1 To identify the different factors that cause university drop-outs by using new technologies and by looking at the literature and scientific databases.

3.2 Determine the most appropriate authors on the topic of university dropout using scientific literature and different databases.

4. Materials and methods

In line with the aim of the project and the objectives pursued, this study attempts to respond to both basic research parameters (identifying, analyzing, and explaining teachers' training itineraries, their projection toward reducing dropout, and connection with digital competence and ICT use), and applied research (creation of digital tools and contents and elaboration of recommendations and proposals for training with a transnational perspective and ICT use).

The following questions have been used as a starting point to determine the goals of the review:

What are the causes of university dropout?

What instruments are needed to collect this information?

A period of the last 5 years, from 2018 to 2022, inclusive, has been considered in order to observe the different tools used.

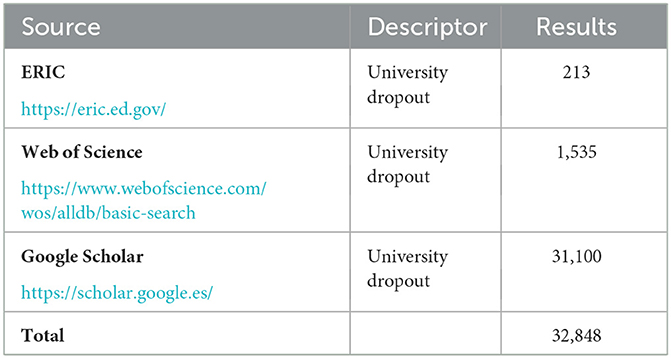

The research was carried out using the Web of Science digital platform; ERIC, as the database specializing in education; and following Wu and Sarker (2022) the database Google Scholar was also used. The key words that guided the review were those associated with university dropout (Table 1).

The search was carried out with the aim of narrowing down, the following inclusion criteria were taken into account:

1. Papers published between 2018 and 2022.

2. Quantitative, qualitative, or mixed studies.

3. Articles in English or Spanish.

4. Full text available.

5. Directly related to the research objective, i.e., including one or more search terms related to the questions posed in the planning phase.

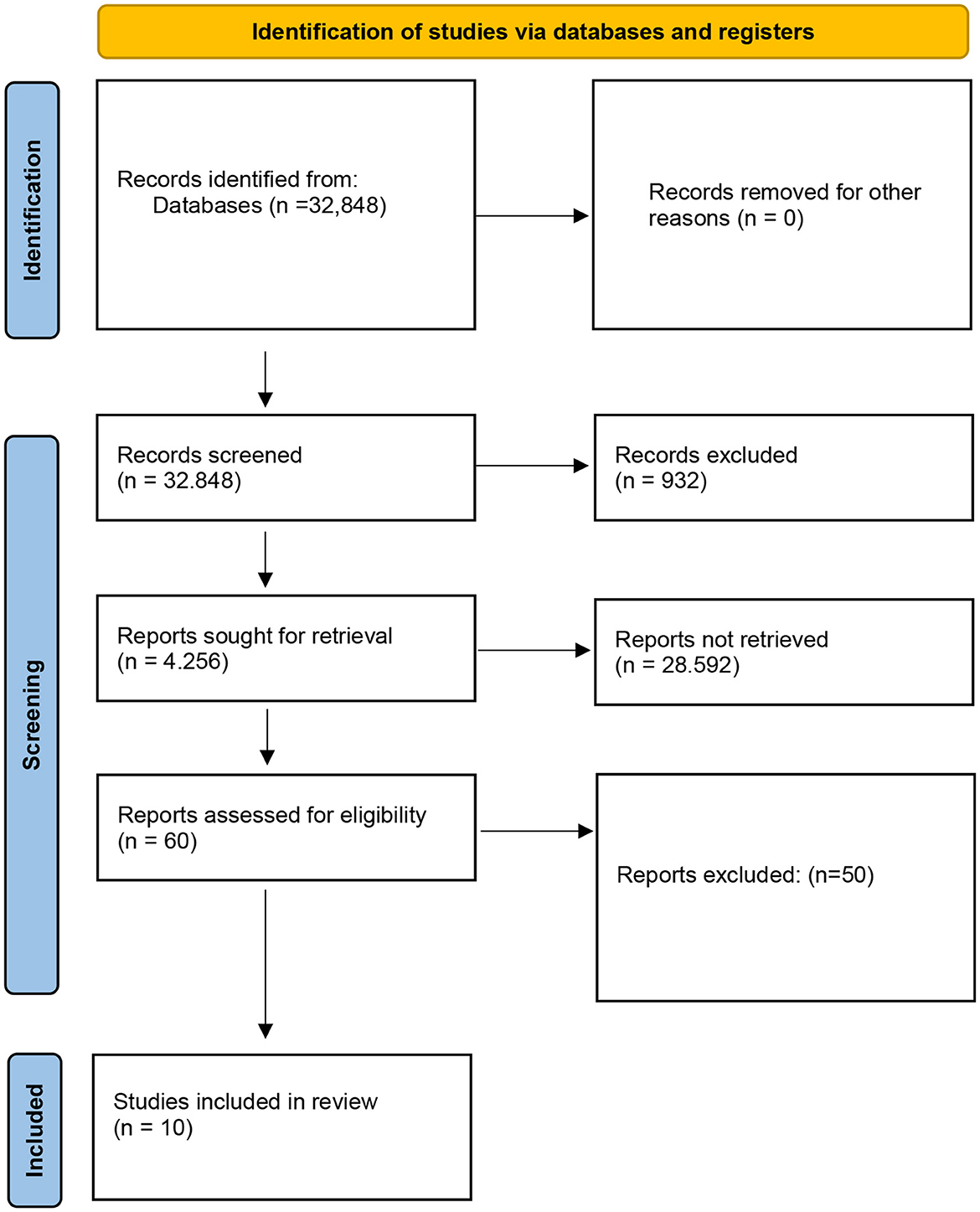

6. Open access.

With these criteria, the information was filtered, discarding articles that did not contain information related to the object of study. Figure 3 shows the flow chart of the search and selection process following the PRISMA guidelines, the purpose of which was to ensure transparency and clarity.

5. Results

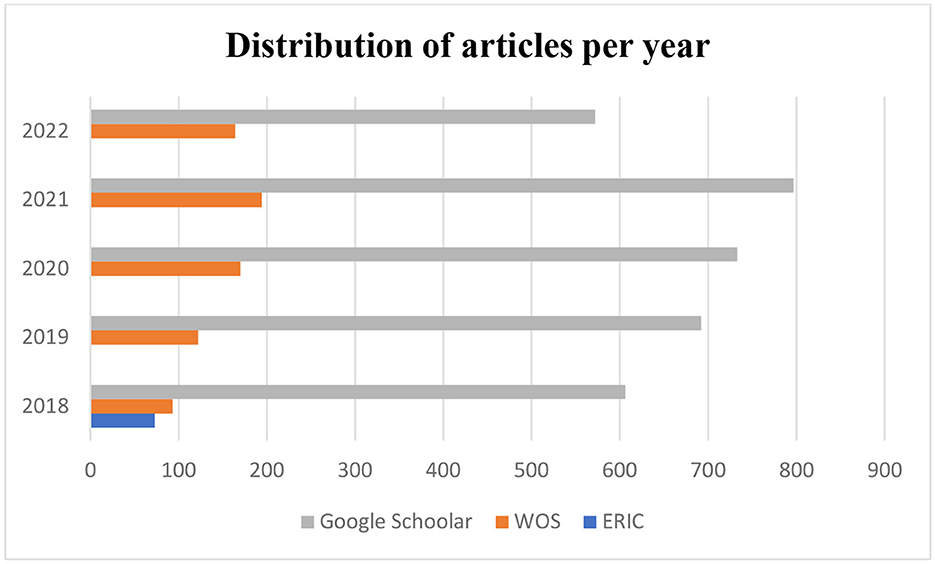

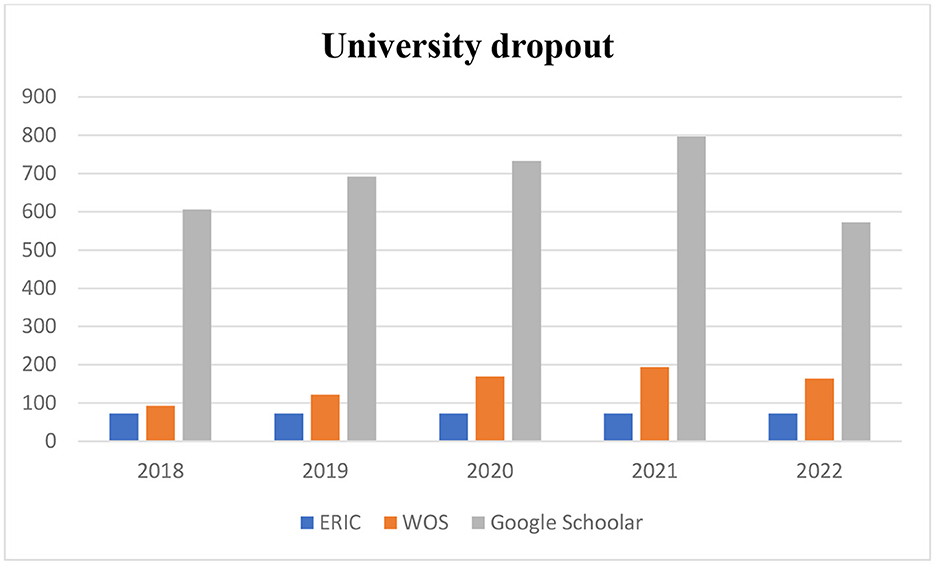

The results of the research are presented below, firstly quantitative and then qualitative, based on the answers to the questions posed above. Following the proposed methodology, the most recent articles were selected, classified, and organized in a matrix where the most relevant information was included. The following figure shows the annual distribution of the selected articles.

As can be seen in Figure 4, the importance that this construct has been gaining over the years is notorious, especially in 2021, with a quite noticeable increase, so it can be seen how in the different databases its research has been growing and therefore, the consideration given to this topic.

On the other hand, the information extraction procedure involved a reading of the articles to determine their contribution to the resolution of the research questions in order to compare them qualitatively (Okoli and Schabram, 2010).

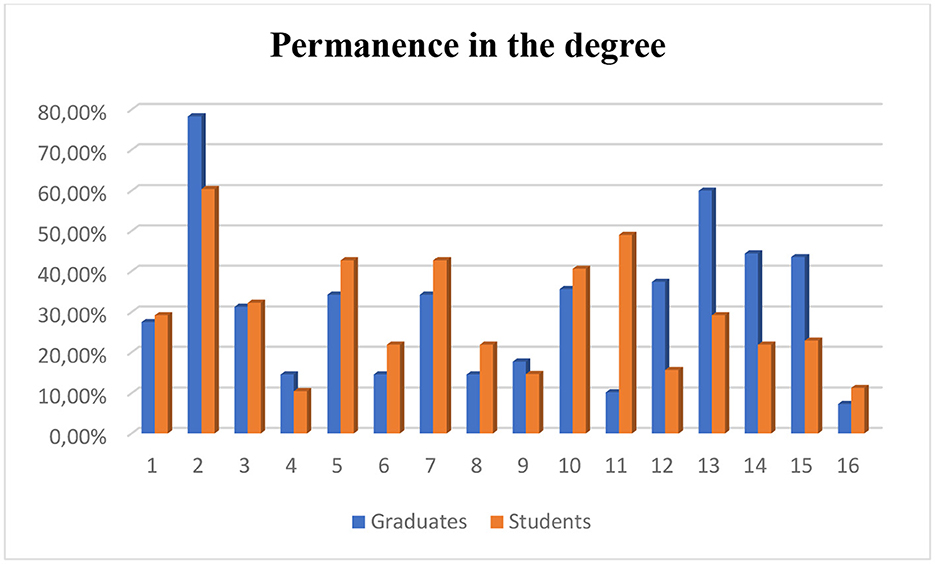

The data that can be visualized in Figure 5 explain some of the reasons that led students who were studying for a degree in Primary Education and students who had completed their studies to consider abandoning their studies at some point during their studies. This is worrying data that allows us to foresee and investigate further into the main reasons for dropping out. In this review, they all agreed on three main reasons: lack of interest, lack of motivation of the students themselves. On the other hand, there are reasons such as the university career itself or lack of time.

As can be seen in Figure 6, the results obtained from the thematic content were based on a keyword, “university dropout,” which has been filtered using the guidelines mentioned above, in order to have a better selection of articles and studies. In the figure, we can see how by introducing the keyword, several studies appear, highlighting the increase in the year 2021, in all the databases collated. Three databases, ERIC, Web of Science (WOS), and Google Scholar, have been considered for the search.

6. Discussion

Several authors have attempted to link psychological and social factors. Fall and Roberts (2012) unified these factors through a model for developing higher student motivation called “Self-System Mode of Motivational Development” (SSMMD). This theory integrates social factors, such as the support students have from their parents and teachers, which are determining factors in students' decisions to drop out of school.

Likewise, it has been observed in several studies that support from family, teachers, and the institution itself is often one of the reasons why students regain their motivation, even when they have academic difficulties, reducing dropout levels in institutions (Martínez and Álvarez, 2005; Fall and Roberts, 2012).

It is interesting to note that factors such as self-esteem and self- concept that led to school failure (frustration) or absenteeism are important for the aforementioned psychological variables, which according to several studies are directly related to student dropout (Martínez and Álvarez, 2005; Barbero, 2016).

On the other hand, it is necessary to highlight those factors that depend on the institution, factors related to all those supports that accompany the student in the course of their education. To curb university dropout, institutions have addressed several strategies, one of which is the systematic monitoring of the characteristics and performance of students (Munizaga, 2018), accompanying them in their process with devices for higher education. Such initiatives are intended to reduce dropout rates and increase retention rates.

In a study carried out at the University of Valencia (Chiva et al., 2016), they suggest that students' satisfaction with their Bachelor's Degrees in Education is due to the changes that the institutions have made to improve their degree, those related to the provision of information and knowledge of the professional opportunities available to them.

7. Conclusions

The main conclusions of this research are, firstly, that the main causes are due to the most personal aspects of the students themselves. These causes involve psychological and social factors, such as stress, anxiety, frustration and demotivation, socio-economic level, socio-family context, and personal factors, including institutional factors. These are the reasons why thousands of students around the world often drop out of their studies.

In this sense, it is understood that psychological factors prevail in the causes of dropout, whether due to a poor adaptation to university or to the difficulty involved in the degree studied by the student. Another of the reasons why students are discouraged and frustrated is due to their own perception of themselves, their sociability with the university community, where some, even though they have had a period of adaptation, have not managed to integrate into university life, which leads them to decide to abandon their studies.

Finally, it should be noted that most students, despite these types of characteristics associated with dropping out, have good impressions of the degrees they have studied. These reasons are encouraged by the students' own expectations, interests, needs, and demands, as they understand that the institutions meet the expectations and educational quality that they themselves demand and need for their adequate training.

In this way, by reiterating the motivation of the students, they are able to continue their studies and are more able to continue to hold on to the positive premises that their careers bring, both in terms of education and socio-economic future, and are motivated and motivated to continue their studies.

Supported by the institution itself and its environment, which encourages the retention of students for the completion of their degrees and decreasing the negative feelings that lead them to drop out of their studies.

Higher education is the engine of developed societies; therefore, the greatest contribution of this study is to provide an in-depth analysis of the variables involved in higher education dropout. This will help the agents involved in processes such as the creation and execution of strategies and policies to make the appropriate decisions to improve the situation regarding higher education.

8. Limitations and future perspectives

One of the limitations found in this study is the use of only one variable for the study. In future studies, it is intended to consider other types of variables in order to broaden the spectrum of the study of this topic and make it more complete.

The second limitation refers to the fact that this study refers to the linguistic immersion in the Web of Science and Scopus databases, although it is true that these two databases are extensive and cover many similar studies already related to the subject of the study, it would be advisable to explore other databases in order to make up for this limitation, in this sense and linking with future proposals, the exploration of other databases will be included in other similar research, in this way investigating more about university dropout at a national level and in foreign universities.

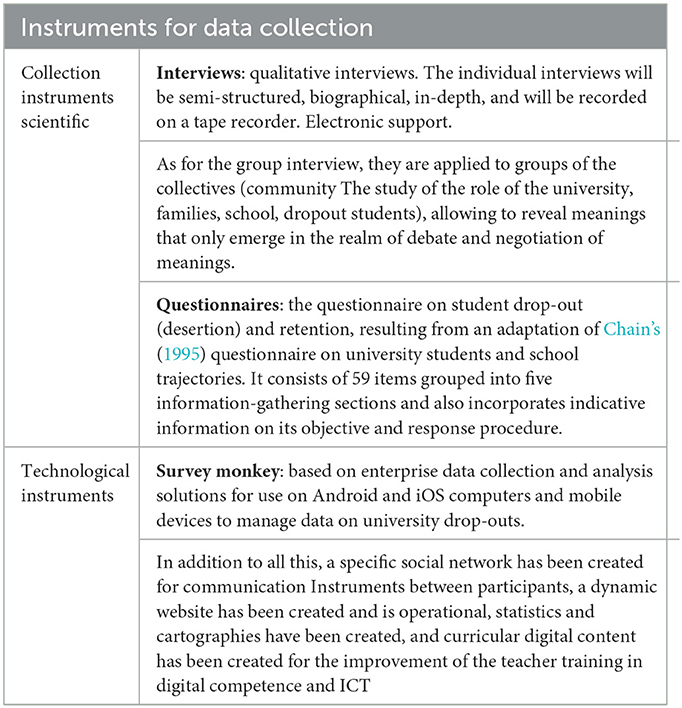

In addition, for future research, it is intended to collect empirical data that will provide an objective view of all these variables involved in university dropout. As can be seen in Table 2, there are different instruments that will be used for data collection. Therefore, one of the main limitations is that the meta-analysis has not been carried out. However, it will correspond to the future of this research, since at this moment it is in the theoretical conceptualization.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

OL-Q have searched the different databases to choose the articles that were most suitable for the research interest. AL-T made a selection of the best articles, already filtered, which were passed on to OL-Q and SG-L, who were in charge of their analysis. SG-L was in charge of producing the different figures and tables. AL-T worked on the discussions and conclusions. SG-L worked on the limitations and future perspectives, and finally OL-Q finished with a final revision of the manuscript and its translation into English. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study has been carried out within the framework of the project ICT Innovation for the analysis of the training and satisfaction of students and graduates of early childhood and primary education and the assessment of their employers. A transnational perspective (INNOTEDUC). Reference B-SEJ-554-UGR20 (2021-2023), financed by the Operational Programme Andalusia FEDER 2014-2020 (Proyects I+D+I). Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación de la Junta de Andalucía (Spain).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbate, J. (2008). Admission, support and retention of non-traditional students in university careers. Rev. Electr. Iberoam. Calid. Efic. Camb. Educ. 6, 7–35.

Agudo, J. C. (2017). Can MOOCs favour learning by decreasing university dropout rates? Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Dist. 20, 125–142.

AIReF (2020). Study of the Andalusian Public University System. Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility.

Al Ghanboosi, S., and Alqahtani, A. (2013). Student drop-out trends at Sultan Qaboos University and Kuwait University: 2000–2011. Coll. Stud. J. 47, 499–506.

Álvarez, D. (2021). Analysis of university dropout in Spain: a bibliometric study. Publicaciones 51, 241–261. doi: 10.30827/publicaciones.v51i2.23843

Aries, E., and Seider, M. (2005). The interactive relationship between class identity and the college experiencie: the case of lower income students. Qual. Sociol. 28, 419–443. doi: 10.1007/s11133-005-8366-1

Ariño, A., and Llopis, R. (2011). University Without Classes? Living Conditions of University Students in Spain (Eurostudent IV). Available online at: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/d/14909/19/0 (accessed January 18, 2023).

Barbero, N. (2016). Factores Psicológicos del Adolescente y su Incidencia en el Abandono Escolar. Master Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, (Spain), Facultad de Educación. Department of Theory of Education and Social Pedagogy. Available online at: http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/view/bibliuned:master-Educacion-~IntConSoc-Nbarbero (accessed January 18, 2023).

Bernardo, A., Cervero, A., Esteban, M., Fernández, E., and Núñez, J. C. (2016). Influencia de variables relacionales y de integración social en la decisión de abandonar los estudios en Educación Superior. Psicol. Educ. Cult. XX, 138–151.

Cabrera, A. F., Pérez, P., and López, L. (2014). “Evolution of perspectives on the study of university retention in the USA: conceptual bases and turning points,” in Persisting with Success at University: From Research to Action, Coord. P. Figuera (Laertes), 15–40.

Castaño, E., Gallón, S., Gómez, K., and Vásquez, J. (2008). Analysis of the factors associated with student dropout in Higher Education: a case study. Rev. Educ. 345, 255–280.

Castejón, A., Ruiz, M., and Arriaga, J. (2015). “Factors/profiles of the reasons for university dropout at the Polytechnic University of Madrid (paper). V CLABES,” in Fifth Latin American Conference on Dropout in Higher Education, University of Talca (Chile).

Castejón, C., and Pérez, S. (1998). A causal-explanatory model on the influence of psychosocial variables on academic performance. Bordón. J. Pedag. 2, 170–184.

Castillo, M. (2010). Desertion at university level. Ensay. Pedagóg. 5, 37–56. doi: 10.15359/rep.5-1.2

Cerda-Navarro, A., Sureda-Negre, J., and Comas-Forgas, R. (2017). Recommendations for confronting vocational education dropout: a literature review. Empirical Res. Voc. Ed. Train 9, 17. doi: 10.1186/s40461-017-0061-4

Chain, R. (1995). Estudiantes universitarios: Trayectorias escolares. México: Universidad Veracruzana-Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.

Chiva, I., Ramos, G., and Moral, A. M. (2016). Analysis of the satisfaction of the students of the degree of Pedagogy of the Universitat de València. Rev. Complut. Educ. 28, 755–772. doi: 10.5209/rev_RCED.2017.v28.n3.49831

Cholewa, B., and Ramaswami, S. (2015). The effects of counseling on the retention and academic performance of underprepared freshmen. J. Coll. Stud. Reten. Res. Theory Pract. 17, 204–225. doi: 10.1177/1521025115578233

Corominas, E. (2001). The transition to university studies. Dropout or change in the first year of university. Rev. Invest. Educ. 19, 127–151.

CRUE (2016). Spanish Universities in Figures 2014–2015. Available online at: http://www.crue.org/SitePages/La-Universidad-Espa%C3%B1ola-en-Cifras.aspx (accessed January 18, 2023).

De Vries, W., León, P., Romero, J., and Hernández, I. (2011). Dropouts or disappointed? Different causes for dropping out of university studies. J. High. Educ. 40, 29–49.

Díaz, A., Pérez, M. V., Gutiérrez, A. B. B., Fernández-Castañón, A. C., and González-Pienda, J. A. (2019). Affective and cognitive variables involved in structural prediction of university dropout. Psicothema 31, 429–436. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2019.124

Doerschuk, P., Bahrim, C., Daniel, J., Kruger, J., Mann, J., and Martin, C. (2016). Closing the gaps and filling the STEM pipeline: a multidisciplinary approach. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 25, 682–695. doi: 10.1007/s10956-016-9622-8

Duque, L. C., Duque, J. L., and Surinach, J. (2013). Learning outcomes and dropout intentions: an analytical model for Spanish universities. Educ. Stud. 39, 261–284. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2012.724353

Elias, M. (2008). University dropouts: challenges facing the European Higher Education Area. Estud. Sob. Educ. 15, 101–121.

Esteban, M., Bernardo, A., Tuero, E., Cervero, A., and Casanova, J. (2017). Influential variables in academic progress and permanence at university. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 10, 75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejeps.2017.07.003

Estrada, H., De la Cruz, S., Bahamón, M., Perez, J., and Caceres, A. (2017). Burnout acad?mico y su relaci?n con el bienestar psicol?gico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Espacios. 39, 1–17. Available online at: https://n9.cl/4engq

Eurostat (2020). Tertiary Education Statistics. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Tertiary_education_statistics (accessed January 18, 2023).

Evers, F., and Mancuso, M. (2006). Where are the boys? Gender imbalance in higher education. High. Educ. Manage. Policy 18, 71–84. doi: 10.1787/hemp-v18-art15-en

Fall, A. M., and Roberts, G. (2012). High school dropouts: interactions between social context, self-perceptions, school engagement, and student dropout. J. Adolesc. 35, 787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.11.004

Fonseca, G., and García, F. (2016). Permanence and dropout in university students: an analysis from organizational theory. Rev. Educ. Super. 45, 25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.resu.2016.06.004

Gairín, J., Muñoz, J. L., Galán, A., Sanahuja, J. M., and Fernández, M. (2013). Tutorial action plans for students with disabilities: a proposal to improve the quality of training in Spanish universities. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 63, 115–126. doi: 10.35362/rie630504

Garbanzo, G. M. (2007). Factors associated with academic performance in university students, a reflection from the quality of public higher education. Rev. Educ. 31, 43–63.

García de Fanelli, A. M. (2014). Academic performance and university dropout. Models, results and scopes of academic production in Argentina. Rev. Argent. Educ. Super. 8, 9–38.

García, A. (2014). Rendimiento académico y abandono universitario: Modelos, resultados y alcances de la producción académica en la Argentina. Revista Argentina de Educación Superior. 6, 9–38.

García, A., and Adrogué, C. (2015). Abandono de los estudios universitarios: dimensión, factores asociados y desafíos para la política pública. Rev. Fuent. 16, 85–106. doi: 10.12795/revistafuentes.2015.i16.04

González, M., Álvarez, P., Cabrera, L., and Bethencourt, J. (2007). Dropping out of university studies: determinants and preventive measures. Rev. Españ. Pedag. 236, 71–86.

Gury, N. (2011). Dropping out of higher education in France: a micro-economic approach using survival analysis. Educ. Econ. 19, 51–64. doi: 10.1080/09645290902796357

Gutierrez, B., Cerezo, R., Rodríguez, L., Nuñez, J., Tuero, E, and Esteban, M. (2015). Predicción del abandono universitario: variables explicativas y medidas de prevenci?n. Revista Fuentes. 16, 63–84. doi: 10.12795/revistafuentes.2015.i16.03

Hernández-Jiménez, M. T., Moreira, T. E., Solís, M., and Fernández, T. (2020). Descriptive study of socio-demographic and motivational variables associated with dropout: the perspective of first-time university students. Rev. Educ. 44, 1. doi: 10.15517/revedu.v44i1.37247

Huntington, N., and Gill, A. (2020). Semester course load and student performance. Res. High. Educ. 62, 623–650. doi: 10.1007/s11162-020-09614-8

Íñiguez, T., Elboj, C., and Valero, D. (2016). The University of the European Higher Education Area in the face of undergraduate dropout. Causes and strategic proposals for prevention. Educ. J. 52, 285–313. doi: 10.5565/rev/educar.674

Jacob, B. A. (2002). Where the boys aren't: non-cognitive skills, returns to school and the gender gap in higher education. Econ. Educ. Rev. 21, 589–598. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00051-6

Jones-White, D. R., Radcliffe, P. M., Lorenz, L. M., and Soria, K. M. (2014). Price out? The influence of financial aid on the educational trajectories of first-year students starting college at a large research university. Res. High. Educ. 55, 329–350. doi: 10.1007/s11162-013-9313-8

Lázaro, A. (2003). “Tutorial competences at the University,” in La Tutoría y los Nuevos Modos de Aprendizaje en la Universidad, eds F.F. Michavila Pitarch and J. García Delgado (Comunidad de Madrid: Consejería de Educación), 107–128.

Lehmann, W. (2007). “I just didn't feel like I fit in”: the role of habitus in university drop-out decisions. Canad. J. High. Educ. 37, 89–110. doi: 10.47678/cjhe.v37i2.542

Long, M., Ferrier, F., and Heagney, M. (2006). Stay, Play or Give It Away? Student Continuing, Changing or Leaving University Study in First Year. Australian Government Department of Education Science and Training.

Lorenzo, O. (2021). Professional Insertion and Graduate Follow-Up. A Multicultural Perspective. Madraid: Síntesis.

Lorenzo, O., and Zaragoza, J. E. (2010). Exploratory study on university student dropout in Mexico. Publicaciones 40, 109–123.

Lydner, K. (2022). Drop.Out Prevention and Strategies to Help Special Education Students. Higher Education in Caulfield School of Education. Doctoral Thesis, Saint Peter's University.

Marchesi, A. (2000). A system of indicators of educational inequality. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 23, 1–22. doi: 10.35362/rie2301009

Martínez, M. (1999). El enfoque sociocultural en el estudio del desarrollo y la educación. Rev. Electrón. Invest. Educ. 1, 1.

Martínez, R. A., and Álvarez, L. (2005). Fracaso y abandono escolar en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria: implicación de la familia y los centros escolares. Aula Abierta 85, 127–146.

MDSyF (2003). CASEN Survey. Available online at: http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/casen/casen_obj.php (accessed January 18, 2023).

Merlino, A., Ayllón, S., and Escanés, G. (2011). Variables that influence the dropout of first-year university students. Construction of dropout risk indexes. Actual. Invest. Educ. 11, 1–30. doi: 10.15517/aie.v11i2.10189

Meyer, T., and Thomsen, S. L. (2018). The role of high-school duration for university students' motivation, abilities and achievements. Educ. Econ. 26, 24–45. doi: 10.1080/09645292.2017.1351525

Mori, M. D. P. (2012). University dropout in students of a private university of Iquitos. Rev. Digit. Invest. Docen. Univ. 6, 60–83.

Munizaga, M. F. (2018). Retención y abandono estudiantil en la educación superior universitaria en América Latina (Doctoral thesis). Available online at: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/187777

Nieman, M. M. (2013). South African student's perceptions of the role of a gap year in preparing them for higher education. Afr. Educ. Rev. 10, 132–147. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2013.786880

OECD (2010). Education at a Glance 2010: OECD Indicators. Available online at: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/d/14340/19/1 (accessed January 18, 2023).

OECD (2017). Education at a glance 2017: OECD Indicators. Available online at: https://www.mecd.gob.es/dctm/inee/eag/2017/panorama-de-la-educacion-2017-def-12-09-2017red.pdf?documentId=0901e72b8263e12d (accessed January 18, 2023).

Okoli, C., and Schabram, K. (2010). A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research. Sprouts Work. Pap. Inform. Syst. 10, 26. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1954824

Ononye, L. C., and Bong, S. (2018). The study of the effectiveness of scholarship grant program on low-income engineering technology students. J. STEM Educ. Innov. Res. 18, 26–31.

Pedraza, I. (2021). Mediation Processes Associated with University Dropout: A Study from a Sociocultural Approach. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Seville, Spain.

Planas, J. A., Prieto, J., and Lizandra, R. (2011). The Tutorial Action Plan [Paper]. Master's Degree in Intervention and Psychopedagogical Counselling for Professionals, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

Polumbo, B. (2017). Up To 60 Percent of College Students Need Remedial Classes. This Needs To Change Now. Available online at: https://thefederalist.com/2018/09/18/60-percent-college-students-need-remedial-classes-needs-change-now/ (accessed March 3, 2023).

Project Alpha Guide DCI-ALA/2010/94. (2013). Collective Construction of the Concept of Dropout in Higher Education for its Measurement and Analysis. Available online at: http://www.alfaguia.org/www-alfa/index.php/es/invest-abando/marcoconceptual.html (accessed January 18, 2023).

Puertas Cañaveral, I. C., and De Oliveira Sá, T. A. (2017). REUNI: Expansão, segmentação e a determinação institucional do abandono. Estudo de caso na Unifal-M. EccoS . Revista Cient?fica. 44, 93–115. doi: 10.5585/EccoS.n44.7899

Rodriguez, L. F. (2013). El enfoque PUEDES: un paradigma para comprender y responder a la crisis de deserción escolar/expulsión de las latinas del siglo XXI en los EE. UU. J. Crit. Thought Praxis. 2.

Rodríguez-Pineda, M., and Zamora-Araya, J. A. (2020). Early dropout in university students: a cohort study on its possible causes. Uniciencia 35, 19–37. doi: 10.15359/ru.35-1.2

Sacristán, V. (2018). Fee hikes push students out of university. El Periódico. Available online at: https://www.esteve.org/en/publicaciones/la-subida-de-tasasexpulsa-a-los-estudiantes-de-la-universidad/ (accessed March 3, 2023).

Severiens, S., and Dam, G. (2012). Leaving college: a gender comparison in male and female-dominated programs. Res. High. Educ. 53, 453–457. doi: 10.1007/s11162-011-9237-0

Sevilla, D. D. S., Puerta, V. A., and Dávila, J. (2010). Influence of socioeconomic factors on student attrition in the social sciences. J. Intersci. Intercult. Dial. 6, 72–84. doi: 10.5377/rci.v6i1.282

Silver Wolf, D. A. P., Perkins, J., Butler-Barnes, S. T., and Walker, T. A. (2017). Social belonging and college retention: results from a quasi-experimental pilot study. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 777–782. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0060

Sosu, E., and Pheunpha, P. (2019). Trajectory of university dropout: investigating the cumulative effect of academic vulnerability and proximity to family support. Front. Educ. 4, 6. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00006

Spady, W. (1970). Dropout from Higher Education: an interdisciplinary review and synthesis. Interdiange 1, 64–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02214313

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., Fryberg, S. A., Johnson, C. S., and Covarrubias, R. (2012). Unseen disadvantage: how American universities' focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1178–1197. doi: 10.1037/a0027143

Tejedor, F., and García-Valcárcel, A. (2007). Causes of low university student performance (in the opinion of teachers and students). Proposals for improvement in the framework of the EHEA. Rev. Educ. 342, 443–473.

Terry, M. (2008). The effects that family members and peers have on students' decisions to drop out of school. Educ. Res. Quart. 31, 25–38.

Tinto, V. (1987). The Principles of Effective Retention. Paper presented at the Fall Conference of the Maryland College Personnel Association.

Torres, I. S. (2018). “Longitudinal study Permanence and dropout in university students (2015–2019) [paper],” in VIII CLABES. Eighth Latin American Conference on Dropout in Higher Education, Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá(Panama).

Vera, G. G., and Álvarez, M.I. (2022). Motivation and student desertion in technological institutes of higher education in Guayaquil. Polo Conocim. 7, 2078–2097. doi: 10.23857/pc.v7i6.4182

Viale, H. (2014). Una aproximación teórica a la deserción estudiantil universitaria. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria. p. 1. doi: 10.19083/ridu.8.366

Weinstock, C. P. (2017). Depression in Late Teens Linked to High School Dropout. Reuters Health. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-teens-depressiondropouts-idUSKBN1E22RA

Keywords: higher education, university dropout, retention, university community, students

Citation: Lorenzo-Quiles O, Galdón-López S and Lendínez-Turón A (2023) Factors contributing to university dropout: a review. Front. Educ. 8:1159864. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1159864

Received: 06 February 2023; Accepted: 22 February 2023;

Published: 15 March 2023.

Edited by:

Antonio Hernandez Fernandez, University of Jaén, SpainReviewed by:

José Manuel Ortiz Marcos, University of Granada, SpainRoberto Cremades-Andreu, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Eufrasio Pérez Navío, University of Jaén, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Lorenzo-Quiles, Galdón-López and Lendínez-Turón. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oswaldo Lorenzo-Quiles, oswaldo@ugr.es

†ORCID: Oswaldo Lorenzo-Quiles orcid.org/0000-0002-1087-8138

Samuel Galdón-López orcid.org/0000-0003-0804-6006

Ana Lendínez-Turón orcid.org/0000-0001-6780-4431

Oswaldo Lorenzo-Quiles

Oswaldo Lorenzo-Quiles Samuel Galdón-López†

Samuel Galdón-López†  Ana Lendínez-Turón

Ana Lendínez-Turón