Examining gender issues in education: exploring confounding experiences on three female educators’ professional knowledge landscapes

- 1Department of Art and Design, Mount St. Joseph University, Cincinnati, OH, United States

- 2Teaching, Learning and Culture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 3Asian American Studies Center, University of Houston, Houston, TX, United States

Business sources report that it will take 124 years for females to achieve parity in the workforce. Parity relates to compensation but also includes working conditions. The latter topic is taken up in this article using narrative inquiry as our method of investigation. Narrative inquiry—inquiring into narratives—employs three research tools: broadening, burrowing and storying/re-storying. To these tools, fictionalization, a fourth tool, is added. This is because the interwoven cases involve easily identifiable others and precautions need to be taken. This article discusses gender matters lived and told, and re-lived and re-told, over the career continuum of three women who have worked in public school and university settings. As females, they periodically encountered situations where they were perceived, interpreted, and responded to differently than males. The article looks at early, mid, and recent career challenges experienced in the female educators’ places of work. This research using narrative methods looks backward, forward, inside, and out through processes of individual and group reflection. It begins with bio-sketches, which were prepared individually. After that, the aforementioned research tools are used to unpack early, middle, and current career happenings. Reflective unpacking of the three females’ experiences within a community of critical friendship allowed for greater understanding and meaning-making to occur. The underlying intent of this work is to understand the shaping forces of gender on women’s professional lives—not to name and shame those who got away with acting the ways in which they did. The significance of the work lies in its use of narrative exemplars that are transparent, have a ring of authenticity to them, and promote trustworthiness and relatability when shared with others.

Introduction

When part of Carol Gilligan’s (1977) In a different voice was listed as a required reading in a research methods course a few years back, one female student immediately divulged that she had never experienced gender issues in the workplace or felt that males made sense of their experiences differently than females. A hush fell over the classroom. Some females looked like they might literally jump out of their skin; other males and females lowered their gazes so as not to affirm the existence of the phenomenon. The female student continued: “Perhaps we are discussing a past generation of women?”

As women representing different age groups of female scholars (with first author, Michaelann Kelley, being younger than Cheryl Craig and Gayle Curtis), we wondered whether this was the case. While we, as authors, agree in principle that successive generations of women have paved the way to paper statements of gender equality, which we currently enjoy, we are also acutely aware that some gender matters—such as microaggressions—remain unresolved. This is not unusual, given that a popular conception is that the field of education is a last stronghold of male privilege (Belenky et al., 1986; Asadi and Ali, 2021; Monroy et al., 2021).

In this article, each of us as members of our three author team takes up an early career experience when we first became aware that different privileges were afforded men. We then follow our early experience with a middle career experience and ending with a recent lived experience in our current places of work. We follow these narratives of experience (Connelly and Clandinin, 1988) with our interim reflective analysis and unpacking. We close with overarching themes that traverse our narrative exemplars and implications for the future. After that, we discuss our conclusions. For now, we launch this article with our literature review and research method.

Literature review

Six bodies of literature are germane to the inquiry at hand: (1) status of women in education; (2) education, experience, and life; (3) professional knowledge landscapes; (4) identity; (5) gendered self; and (6) context.

Status of women in education

The Harvard Business Review calculated that it will take 124 years for females to achieve parity in the workforce (Gallop and Chomorro-Premuzic, 2022). Parity has to do with compensation but it also includes working conditions. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) (2018) reported that women make up the majority of non-tenure-track lecturers and instructors across all American institutions of higher learning, but only 44% of tenure-track faculty and 36% of full professors. Women of color are especially underrepresented in college faculty and staff, which escalates diversity, equity and inclusion issues in teaching practices and curriculum as well as the availability of role models and support systems for females (Hopkins et al., 2019). About 30% of college presidents are women, with more than 50% of department head positions being filled by women (Bichsel and McChesney, 2017). Females only make up approximately 30% of college boards of directors (American Council of Education, 2017). AAUP stated that women are still paid less than men at every faculty rank and in most positions within institutional leadership (Hopkins et al., 2019; Colby and Fowler, 2020), with higher education administrators experiencing around a 20% gender pay gap and college presidents having a pay gap under 10% [American Association of University Women, (n.d.)]. Where science and innovation awards are concerned, females are catching up, but the awards they achieve are neither equivalent to their share of tenure-track positions (Watson, 2021) nor at the level of prestige of males, which may contribute to their dropping out of the STEM disciplines (Uzi, 2019). Overall, women, while achieving similar article and citation counts, need to increase their awards by 50% in order “to achieve parity” with men (Meho, 2021). Most recently, females in academia have been negatively impacted by COVID-19, with their research and funding falling behind presumably due to their added caregiving responsibilities. Also, more women are not accepting leadership positions and some have chosen to leave academia altogether (Newman, 2022) becoming part of what is now being called the “great resignation” (Lodewick, 2022). At the very least, OECD has concluded that there is an urgent, ongoing need to review equity policies to ensure that society is not accommodating itself to the detriment of women (Vincent-Lancrin, 2008).

Education, experience and life

Dewey (1938) connected education, experience and life in profound ways. For him, human experience—and most especially memories of said experiences (Ben-Peretz, 1995)—is what sets human beings apart from animals. For Connelly (1995), “memory [works to] connect meaning to experience for events, chronicles, stories, and narratives” (Connelly, 1995, p. vxi). Two kinds of experience exist: (1) educative—experiences that enhance one’s education—and (2) miseducative—experiences that detract from the quality of one’s education. Cumulatively, educational experiences constitute formal and informal education. Taken together, education, fueled by ongoing experiences and memories of past experiences, become interwoven to form human life as we know it. It follows that lives are not fixed. Lives are always in motion because experience unceasingly unfolds and education, particularly informal education, continues to take place. And, as Conle (2001) points out,

This seems appropriate if one considers good teaching not primarily as an accomplishment in appropriate planning, excellent techniques, and thoughtful pedagogical moves, but as a lived accomplishment that is intimately linked to the way one lives one’s life and relates to people and deals with patterns of teaching and learning that were acquired earlier in life (p. 22).

Professional knowledge landscapes

Educators’ lives unfold on a professional knowledge landscape. This landscape consists of both in-classroom and out-of-classroom places (Clandinin and Connelly, 1995). In-classroom places are the places where teachers may live out secret stories of teaching with students as these places are relatively unmonitored. However, in the out-of-classroom place, that is where all the prescriptions and mandates come to teachers via a metaphorical conduit (Clandinin and Connelly, 1995; Craig and Olson, 2002), which tells them what they can and cannot do. These places on the professional knowledge landscape are not impermeable. Teachers may share stories from their in-classroom places in out-of-classroom places. Alternatively, people from out-of-classroom places may be welcomed into in-classroom places at a teacher’s discretion.

Identity

Identity, in narrative terms, is “stories to live by” Clandinin and Connelly (1998) and Connelly and Clandinin (1999). “Stories to live by” are narratives that are not fixed. They shift with ongoing experience as people re-story their pasts and lean into their futures. Three kinds of identity shifting stories have been identified: (1) “stories of staying” (Craig, 2014), (2) “stories of leaving” (Craig, 2014) and (3) “stories to start over again” (Craig, 2017). Humans can have more than one narrative unfolding at one time in their lives—for example, stories of staying and stories of leaving—followed by stories to begin again by. However, when a tipping point is reached, the favored narrative becomes assumed in one’s “stories to live by.”

Gendered selves

Gender Studies and Women’s Studies are fields all their own in addition to being broadly a part of psychology. Where education is concerned, gender became a hot topic when psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg posited six stages of moral development based on universal principles, using only male subjects in his investigation. His student, Gilligan (1977, 1993), challenged his theory, building on her work with women, which suggested that morality was contextual and relational. Belenky et al. (1986) went on to advance William Perry’s work in cognitive development and Gilligan’s research on the moral/personal development of women. Belenky et al. examined epistemology—that is, “ways of knowing”—of a diverse group of women through focusing on their identities and their intellectual development in a range of contexts that included, but was not limited to, their formal education settings. Gilligan et al. (1990) also studied the relationships between and among adolescent girls at Emma Willard School in New York State. We especially include this latter work because Nona Lyons, Carol Gilligan’s student, is best known to those of us in teaching and teacher education for her work on portfolio development (we are members of the Portfolio Group) (Lyons, 1998), reflective inquiry (we published chapters in her edited handbook) (Craig, 2010; Kelley et al., 2010; Lyons, 2010) and narrative inquiry (Lyons and LaBoskey, 2002) [Craig (2002) wrote a chapter in this volume and also had Nona Lyons as her external examiner for her final Ph.D. defense (Craig, 1992)].

Context

Context, otherwise known as milieu, is one of education’s commonplaces. Schwab (1973, p. 72) established that all educational situations have four commonplaces, that is—“bodies of experience”—to which attention must be paid: teacher, learner, subject matter and milieu. Commonplaces such as milieu (context) are near irrefutable (Goodson, 2009). Milieu can be as small as the backdrop of a conversation that has taken place or as large as geopolitics and differing ramifications on different nations. For Schwab, “knowledge of a context of discourses [Note: multiple discourses; not one discourse] gives us…a fuller knowledge of the scope and meaning of the conclusions.” This led Schwab to declare that “To the question, how big a context? There is no clear answer. There is yet more to know or more to know about” (Schwab, 1956/1978, p. 153). The phrases, to know and to know about, imply that, for Schwab, there would be infinitely more to do and think about doing. This disciplined approach to knowing and doing eventually led to Schwab declaring that “the problems of education arise from exceedingly complex actions, reactions, and transactions...these doings constitute a skein of myriad threads which know no boundaries” (Schwab, 1971, p. 329).

These six bodies of literature are the foundation to our perspective in our work as educators and researchers. We are bound by who we are and live our lives in accordance with our beliefs and values. The literature review gives you a window into our work and the narratives will give you a path to walk alongside us on our journey.

Research methods

Overview of narrative inquiry

Narrative inquiry focuses on human lives through the concept of experience (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000; Caine et al., 2021) and spans the disciplines. Because narrative inquiry attends to lives, it necessarily makes sense of a plethora of human experiences, including those involving gender. This works particularly well for females who are highly adept at communicating their sense of knowing through story (Belenky et al., 1986).

Research tools

Narrative inquiry–or inquiring into narratives–has three original research tools: broadening, burrowing and storying-restorying (Clandinin and Connelly, 1990, 2000). Broadening captures the context within which a three-dimensional experience (time, place, and interaction) (Dewey, 1938) takes place. Burrowing digs deeply into the fine-grained details of the experience, including one’s memories of it, and foregrounds specific interactions for analysis purposes. Meanwhile, storying-restorying is what happens as a narrative is told and re-told, lived and re-lived over time. Memory distinguishes empirical texts from fictional ones (Connelly, 1995). Storying and restorying of experience animates subtle shifts that take place over time.To these three tools, a fourth tool—fictionalization—is added. Fictionalization masks the identities of others in the shared stories of experience but not their words or emotions. This article reveals subtle and not-so-subtle experiences of three females over their career continua—experiences that would unlikely happen to males in the same positions and at similar levels of achievement.

Sources of evidence

As authors, we use our personal journals as our main sources as evidence as well as conversations we have had with one another as knowledge community members, our critical friends, and Portfolio Group members. Knowledge communities (Craig, 1995a,b) are those individuals to whom we take our stories of experience for feedback and further interpretation. It follows that different knowledge communities provide different instruction. As foreshadowed, the Portfolio Group is a group of teacher researchers that have worked in relationship with one another since 1998.

Truth claims

The experiential narratives shared in this chapter resonate with each of us as authors and with one another as knowledge community members who also have shared memories of Portfolio Group conversations. Ultimately, the verisimilitude of the accounts we share will extend to readers who we imagine will lay their stories across time and in place alongside our own.

Interim summary

This article looks backward, forward, inside and out through processes of individual and group reflection. Drawing on our research topic supported by our review of the literature, our data presentation begins with our three introductory bio-sketches. Narrative inquiry’s analytical tools, along with fictionalization, are then utilized to unpack an early, middle, and more recent scenario in each of their careers that show shifts and changes in the “multiple worlds [we] inhabit” (Caine et al., 2021, p. 37).

Stories of experience

Bio-sketch

Michaelann Kelley, Ed.D. is Assistant Professor and Chair of the Department of Art & Design at Mount St. Joseph University founded by the Sisters of Charity, and has had seven presidents, the last few of which have been male. Before joining academia, Kelley worked as an art teacher for 23 years and then served as the district’s Director of Visual Arts for almost 6 years in Northwest ISD. The district situated in the 4th largest city in the US was also the 10th largest school district (almost 80,000 students) in the state. The district, closing in its 87th year anniversary, since 1958 has had six superintendents of which the last three, since 2001, have been women. Kelley has received numerous awards including being named Eagle High School’s Teacher of the Year, 1999, the 2013 Stanford University Outstanding Teaching Award, 2020 National Art Education Association Western Region Supervision & Administration Art Educator, and 2021 Texas Art Education Association Distinguished Fellows honor.

Early career experience

Michaelann’s career could have been so different if not for her childhood experiences and her first principal. She was raised, as was her mother, to get an university education which during the 1950s was not the norm. Her mother went to university and received her bachelors in chemistry. Michaelann’s parents valued a ‘good’ education as did her grandparents. Michaelann attributed that to her grandmother’s father dying in 1918 when she was 15, leaving his wife and five girls to provide for the family during the depression. Michaelann’s parents, just like her maternal grandparents, chose to send their girls to a private all-girl Catholic high school. In fact, she went to the same high school as her mother, even had some of the same teachers. As she reflected back, this decision and the experiences of her family greatly influenced her thinking and beliefs on the roles and responsibilities of a woman. Michaelann described the experience as, “When you attend an all-girl school, the class officers are girls, the president and the secretary are women, the sports activities are centered on girls’ sports, and the theater plays are female-oriented.” This was her world for some very formative years in her life. This foundational time in high school, supported by family expectations and their lived stories provided her with what Michaelann recognizes now as a non-traditional perspective on stereotypical gender roles for women. After graduating with her masters and teaching degree, she could not find a teaching position in the state where she grew up. “The world was changing in the early 90s and women no longer quit working when they got married and started having children,” was how Michaelann talked about that time in her life. Therefore, the turnover in the female-dominated field of education was not happening. Luckily, through the networks that she had forged, Michaelann received a call from a school district in Texas.

Michaelann took a position in a large diverse city with little knowledge of the school, district, or even the city. As it turned out, she was very fortunate that Henry Richards was her principal. He was an innovator and a wonderful mentor. He could see the potential in his teachers and knew how to bring out the best in everyone. Michaaelann stated,

Henry saw in me more than I even saw in myself; he was the one that gave me the responsibility for the large school reform grant. He saw my straight forward direct attitude as an asset, rather than what some people might see as bossy and pushy in a woman.

Michaelann thought he understood her attitude more as a trait of a leader. He encouraged her to take advantage of all the opportunities afforded during the large school reform grant, but his most endearing quality was that he listened. She described it as, “He was masterful at asking the “right” questions to open a space for you to reflect and learn for yourself.” He never tried to “fix” the problem for you. He knew how to support his teachers and their future as leaders.

Middle career experience

As a new district administrator (Director of Visual Arts) in the 4th largest city in the US, Michaelann was surprised to learn that her ‘true’ peers in the surrounding school districts’ hierarchy and in terms of responsibility were not those who initially reached out to her. The first to welcome Michaelann were the Visual Arts Coordinators, a predominantly female group representing over 10 area districts. As she began attending cross-district education meetings and engaging in committee work, Michaelann discovered that she was the only district director participating in the group. She learned that the directors for the other districts were men and that the women that Michaelann had been working with reported to these male supervisors who were mostly former band directors. Upon further investigation, she learned that the women she was working with were not given access to budgets and strategic planning for their content area. In addition, their duties and daily agendas were assigned by their male supervisors. Michaelann’s job description, on the other hand, included budgeting, strategic planning, and curriculum and instruction development, as it seemed she was the only woman in the area with those responsibilities.

When Michaelann worked as the district arts administrator in the 10th largest public school district in Texas, it was under the leadership of its third female superintendent. In the context of her work, the majority of visual arts district coordinators were women, yet the positions of power in the budgeting, strategic planning, and curriculum and instruction were held mostly by men. Consequently, the voices of leadership and future direction for the visual arts were still male dominant.

Recent career experience

After 28 years in public education as a visual arts teacher then a district administrator, Michaelann moved into higher education. She returned to the university from which she had graduated, a once all-women Catholic college established in 1920 which was designed and founded to counter the inequities in society for women at the time and which continues to enable women to crack the professional glass ceiling today. Now a coeducational university, Michaelann finds it interesting, thought provoking, and at times challenging to work in a context that in some ways is still in transition after making the shift to co-ed 20 years ago. Founded by the Sisters of Charity, the university had a 100-year history of strong female leadership and well-prepared female graduates. While university enrollment in 2020 showed a close balance of females to males to (57 and 43% respectively), active recruitment of male students is a strategic priority of the university. Whereas women have held a long history of leadership in the university, females must now compete with males for those same leadership roles on campus. University-wide, faculty positions are 62% female and 38% male, and the leadership positions (president, provost, dean) 62% female and 38% male. In her department (Art and Design), however, female students greatly outnumber males. The constant push in recruiting efforts for more male students is there, but as she is the chair of the department and responsible for recruiting efforts, it seems that interested high school seniors are still mostly female. Michaelann stated, “I am glad that our department has strong female role models to guide and mentor our art and design students.” While the university is committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion in promoting a sense of belonging for all students, Michaelann is constantly aware of the need to continue chipping away at the professional, social, and economic barriers that women face in the fields of art, design, and education.

Bio-sketch

Cheryl Craig, Ph.D. is a Professor and Endowed Chair in the Department of Teaching, Learning and Culture in the School of Education and Human Development at Texas A&M University. She was employed in the public school system in Alberta, Canada for 15 years as well as taught courses at Canadian universities for 14 of those years. For two of those years, she was also employed by an American university to teach graduate courses on Canada’s west coast. Since immigrating to the US, Cheryl has worked at three research-intensive universities–for a grand total of six universities in all. She is an AERA Fellow and a recipient of the Division B (Curriculum) and Division K (Teacher Education) lifetime achievement/legacy awards. She has also received AERA’s Michael Huberman Award for her outstanding contributions to understanding the lives of teachers.

Early career experience

Cheryl often shares the story of being told earlier in her career that she was too young for this position and too young for that one. She never seemed to be the right age either in the school district or at the universities where she worked. Either she appeared more youthful or her employers were seeking candidates older than her whose turns had not yet come up. Cheryl even wore dark suits and matte makeup to make herself appear older. Nothing she tried interrupted the “too young” plotline. It seemed like the “too young” story was one with which she was saddled. That narrative appeared to be fixed and unchanging, regardless of the university or school positions for which she applied. However, as she reflects back on these early career scenarios connected to age (with decisions based on age currently being against the law), Cheryl now sees—with the benefit of hindsight—that the search committees who interviewed her could easily attribute her lack of selection to her youth and her having a long and successful career ahead of her where she could assume advanced positions. However, in retrospect, she now thinks this was most likely a cover story (Clandinin and Connelly, 1995; Olson and Craig, 2005). In reality, Canada was transitioning to becoming a bilingual, multicultural country. This meant fewer White candidates would be hired into leadership positions so that diverse others could be given equal opportunities and representation. So, during the early period of her career, Cheryl repeatedly ‘lost’ job competitions in school districts and universities to strong women of color: women who could satisfy two diversity boxes (female, non-White) as gender equality was simultaneously being sought. Then, when White males applied for similar positions, they were more likely to be appointed because White females like Cheryl and other women like her had made bilingualism, multiculturalism, and other forms of diversity possible. It can be said that society made huge strides forward where diversity and multiculturalism were concerned, arguably thanks to women (among others). Had Cheryl not run into this brick wall time-and-time again in Canada, she probably would not have immigrated to the U.S. for employment reasons. As an interesting aside, she never encountered this barrier when she moved to the American South where universities and school districts were already highly diverse with visible minoritized populations. Also, she was older by that time and had earned her Ph.D. from a research-intensive university and had been named a Postdoctoral Fellow at a world university, which, along with her other school and university experiences, substituted for her ever being a tenure-track Assistant Professor, a position that she “skipped” due to the longer periods of time she spent in other positions when she was younger.

Middle career experience

Some years later, when Cheryl met with her university department chair to discuss her promotion from associate professor to full professor, he said Cheryl had probably amassed sufficient scholarship to be advanced in her position. However, he added that ‘the men’ in administration would not like her research. His mention of ‘the men’ hit Cheryl the wrong way. In all fairness, this was not the first time she had bristled when the authority of males drove a wedge between her desires and her. As a child, her mother, in performing her gender-based role in the family, always made certain that everything was done for ‘the men’—Cheryl’s father and older brother—before anything involving her and/or Cheryl could be entertained. Cheryl had learned early about white male superiority/entitlement. But the women’s movement had happened in the interim and Cheryl, as a female going up for full professor, expected—at least on paper—non gender-biased, workplace treatment. So why were ‘the men,’ albeit different ones, decades later, in a different country nonetheless, still playing powerful determining roles in her career? ‘The men’ comment created a tension between Cheryl’s chair and her that would last his entire tenure and beyond that because Cheryl ironically was in charge of the program area to which he returned in his post-chair years. When Cheryl asserted that it was ‘not about “the men” but about the scholarly community,’ a near-holy war broke out between them. To begin, he did not give her the opportunity to contribute names for the evaluation of her promotion file, despite that courtesy being stated in policy. On his own, he chose all the possible reviewers. Also, whenever Cheryl passed through the department office, he would inform (bully?) her that her file was not progressing. But, on one such occasion, he could not resist. “Dr. Craig,” he bellowed, “you should be very happy today.” Cheryl shrugged, not wanting to trigger new issues. After he repeated himself, Cheryl admitted to not knowing anything about the promotion procedures and turned to exit the office. He could no longer remain silent. He divulged that he had received a letter from the editor of a top journal in Cheryl’s area of expertise. He then added, “And he has written you a letter better than your mother could have written.” Cheryl smiled sweetly (as females are inclined to do) and truthfully, but pointedly, replied, “That’s excellent because my mother does not like to write letters.” In the end, Cheryl learned that four scholars evaluated her promotion materials: (1) the SSCI journal editor (already mentioned), (2) a famous Stanford University professor, (3) a renowned national teacher educator, and (4) a well-known quantitative researcher who was a dean. The journal editor knew of her through her advisors’ work and her own published articles; the Stanford professor had attended presentations and interacted with her at national and international conferences; the teacher educator had used one of her chapters as a reading in his/her teacher education classes; and the quantitative researcher/dean was her chair’s friend who neither knew about her research, nor about her. Cheryl suspected her chair entered him into the mix, possibly thinking (hoping?) the senior male would write a scathing review. However, her chair’s friend did nothing of the sort. He, like the others, said that Cheryl’s research record was impeccable and that any research-intensive university would employ her. Since Cheryl’s promotion to full professor, she has marveled at the letter that the quantitative researcher/dean submitted (Craig, 2020). It helped her, as a female scholar, to become a full professor in 10 years, despite the systemic issues of gender that perpetually swirled around her as she moved through the academic ranks in two countries.

Recent career experience

Currently, a full professor, an Endowed Chair, a teacher education program lead, and an AERA Fellow in a different American university, Cheryl experiences new iterations of gender issues. Recently, it was implied that she was “greedy” where awards and grants were concerned. Cheryl’s response was that awards and grants are honors conferred on her through a rigorous selection process, not something she excessively demands (Craig and Ratnam, 2021; Ratnam and Craig, 2021). When this exchange unfurled, it stopped Cheryl dead in her tracks. She immediately thought that a distinguished male professor would not be told the story that had just been given back to her. She thought that straw dog man would be congratulated for how strong a scholar he is, the abundance of honors and fame he has brought to the institution, and how he will be nominated for many more such awards in the future. Cheryl knew on the spot that what she had been told slighted her achievements and shamed her for being accomplished. The comment suggested that she was demanding awards and grants rather than earning them competitively through merit and ongoing excellence. However, because this has been such a fresh experience, it is notably shorter because it has not had the benefit of being reflected on over time. It is an experience that remains in the midst of unfurling and in the throws of unknotting.

Bio-sketch

Gayle Curtis, Ed.D. is Program Director with Asian American Studies at University of Houston and Postdoctoral Research Associate at Texas A&M University. Looking to give more back to the community after an extensive career in the oil and gas industry and service to the Latino community, Curtis returned to university to obtain her certification in bilingual education and supervision. After 15 years in public education as a bilingual teacher and school administrator, she followed her passion for learning to university where she received her doctorate in curriculum and instruction. She received the 2014 AERA Narrative Research SIG Outstanding Dissertation Award for her dissertation, Harmonic Convergence: Parallel Stories of a Novice Teacher and a Novice Researcher and the 2019 American Education Research Association (AERA) Narrative SIG Outstanding Publication Award for the co-authored article “The Embodied Nature of Narrative Knowledge: A Cross-Study Analysis of Embodied Knowledge in Teaching, Learning, and Life.”

Early career experience

After working in industry where all the mentors supporting her professional growth and development were male, it was quite a transition for Gayle to move into the female-dominated field of education. Before she even began her career as a bilingual, white female in education, two situations seemed to indicate from whence would come her support in her new career pathway. Both occurred in her search for a bilingual teaching position as she familiarized herself with area schools by substitute teaching part-time during her last semester for a bachelor’s degree in bilingual education.

The first situation happened after substituting for several days at Baker Elementary in what teachers described as a “hard to handle class.” The team level teachers shared their appreciation for how Gayle worked with students, then encouraged her to apply for an open position in their level and even arranged for an interview with the school principal. Having not previously met the school’s male Latino principal, she was eager to discuss the possibility of joining the team. At the interview, however, Gayle had barely sat down when the principal began challenging her decision to be a bilingual educator. “What makes you think that you can teach Hispanic children? You are not Hispanic and have no business teaching Hispanic children.” Taken aback, she assured him of her qualifications, thanked him for his time, and informed him that she would look elsewhere for a position. At the time, it bothered her that the principal made no inquiries into her background (she was a longtime member of the local Latino community) nor made any effort to determine her abilities (he had not observed her teaching). She turned to her university advisor, Dr. D.—also a white female bilingual educator fluent in Spanish—for advice and reassurance. Dr. D. encouraged Gayle to not take the principal’s comments personally and to hold to her convictions where bilingual education, teaching, and the needs of Latino students were concerned. According to Gayle, “Dr. D.’s words were an affirmation that I had chosen the right path for me personally and professionally. She also reinforced my confidence in finding a teaching position.”

Somewhat of a counter story occurred during Gayle’s long-term substitute assignment at Fairmont Elementary, a highly sought after school with no teacher openings. One afternoon, she sat with a group of teachers eager to give her advice on which schools to look at for potential employment. When Gayle shared her upcoming interview at Panther Elementary, several teachers suggested that it might be a difficult school for a first-year teacher because of its location in one of the city’s lowest-economic and high crime areas. Gayle explained, “I was unaware that Fairmont’s principal (a Latina) had entered the room behind me and had been listening to our conversation. She stepped up to the group, turned to me, and said, ‘Those students need good teachers, too.’ Her words really resonated with me. I interpreted them to mean that more important than the school’s location were the needs of the students.” As it turned out, Gayle had three offers of employment but chose Panther as the school in which to begin her career in education…never regretting her decision. According to Gayle, these two female educators—her advisor and Fairmont’s principal—were the first of many women to support her journey in education.

Middle career experience

In Gayle’s middle career as a school administrator—long before the “Me Too” movement—she had a number of interactions with females who shared past experiences of inappropriate behavior on the part of male supervisors but were reluctant to say anything at the time for fear of retribution in the workplace. Consequently, most of the incidents had occurred several years before they were shared with Gayle. One female colleague shared that one of the male administrators would sometimes come up behind her while she was typing at her computer and put his hands on her shoulders. She explained that felt she could not express her discomfort because he was her supervisor. When the same thing happened to Gayle, she immediately responded by telling her colleague to remove his hands and to not touch her in that way again. She explained, “Because I felt this person did not understand personal boundaries, I thought it necessary to then explain why what some might consider casual or friendly touching might also be interpreted as overly familiar and unwanted.” Another situation shared with Gayle, this time by a group of female teachers, occurred at a hotel during a conference. As the group readied themselves to go to bed, their male supervisor—on the pretext of needing to relay information—demanded entry into their hotel room, going so far as to state emphatically that they “had to” let him in because he was their supervisor. As in the previous story, this group of women explained to Gayle that they were afraid not to comply with “the request,” for fear that it would be reflected negatively on their evaluations. Gayle explained, “Even though these incidents occurred prior to my becoming a lead administrator, I was compelled and felt obligated to have what were some very, very difficult conversations with my male colleagues.”

Recent career experience

After many years in public education—first as a bilingual teacher, then program coordinator, then school administrator, a deteriorating work environment, politically-charged system, and the accumulation of a series of “spoken/unspoken broken promises” (Craig et al., 2020; Kelley et al., 2021) became Gayle’s “story of leaving” (Craig, 2014). While transitioning into “retirement,” her passion for teaching and learning led her to fulfill a long-term dream of obtaining her doctorate in education. During her doctoral studies, Gayle worked in higher education as both a research assistant and as a clinical instructor, giving her a “taste” of academia. Upon graduation, however, she decided to continue her career along a non-tenure pathway. She explained,

After years of climbing the professional ladder and navigating the choppy waters of public education, I was fortunate to be in a financial position that enabled me to choose a career pathway that enabled me to focus on research and teaching minus the entanglements that often accompany tenure-track positions.

For Gayle, the decision has allowed her to live her best-loved self as an education researcher and teacher educator.

Since moving to higher education, however, she has frequently been asked, “Why are you not a professor?” Interestingly, this question has come most often from men who are either doctoral students she taught or junior faculty working alongside her. In somewhat of a counter narrative, female doctoral students and faculty most often inquire into how Gayle acquired her knowledge and expertise in research and teaching. For Gayle, this dichotomy has raised questions about perspectives on personal goals in that one group of individuals (males) have seemed more focused on end-results of career attainment and the other group (females) more focused on the process of developing into an educator/researcher.

Unpacking our experiential narratives

As heterosexual females, we recognize that our interpretation and analysis of gendered experiences are often shaped by our binary lenses leading us to consider such situations in terms of female and male. We understand that others who have an LGBTQ+ lens bring different perspectives, experiences, and interpretations to similar situations. Despite these varied lenses, at the core of gendered experiences—such as those shared here—is the role that power plays in the education landscape.

Unpacking Michaelann’s stories of experience

Michaelann’s early career story reflects a counter narrative (Clandinin and Connelly, 2004) to the ‘traditional’ story of women and their expected roles in society. Even though her upbringing was sheltered from some of the harsh realities of society’s limiting view of women, she chose a career that is a very traditionally woman-dominated venue—education. Michaelann found a home and a place to flourish as a teacher leader through the guidance of a male principal, Henry Richards. He encouraged all teachers, both male and female, to take on leadership roles and supported their development as teacher leaders. While Henry’s innovative shared leadership approach stood in stark contrast to the micro-management approach to school administration that was common at the time, it created a generative space in which female teachers like Michaelann could flourish.

The middle career story of Michaelann illustrates how one must not rely solely on titles as a gauge of gender parity, showing the need to look closely at job descriptions and assigned responsibilities to determine if parity is indeed accomplished. The discrepancies in titles and responsibilities that Michaelann observed brought to reality the glass ceiling that is still present in many careers, including a female-dominated profession like education.

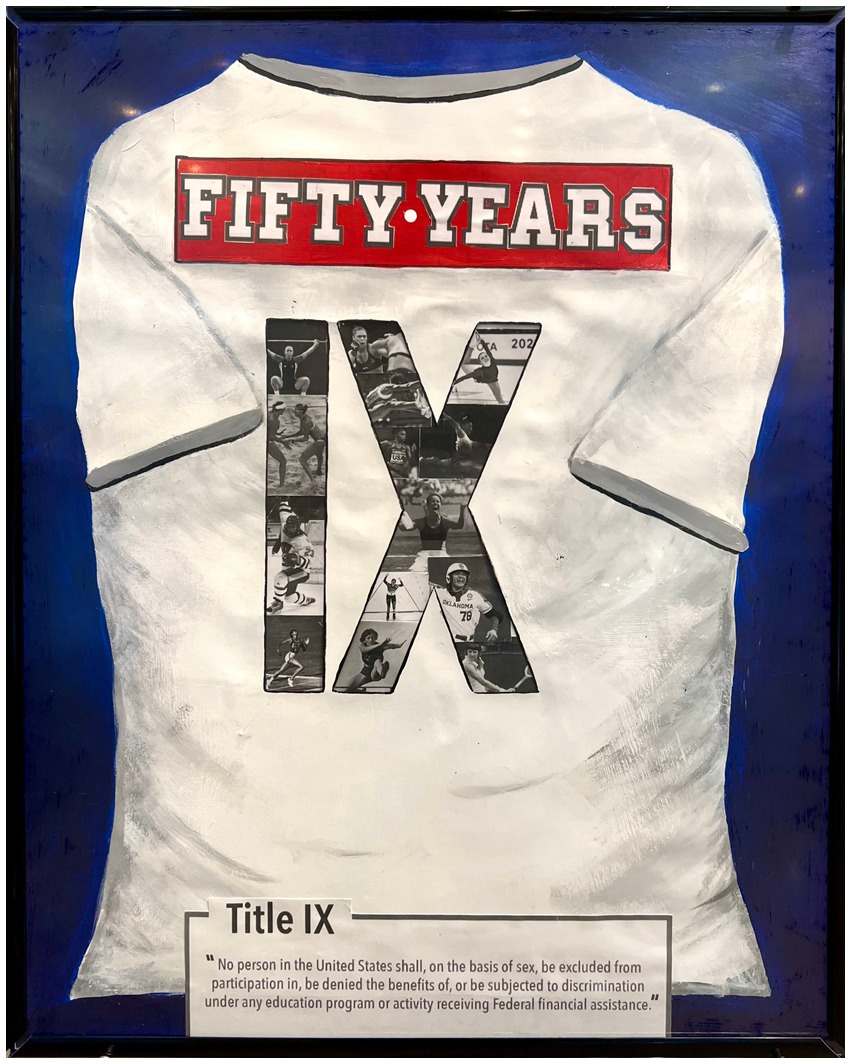

In Michaelann’s last narrative of experience, she poses questions that she has been contemplating on how changes, shifts, and transitions at her new institution are reflective of what is occurring throughout academia. In light of the recent uproar around Title IX, she wonders how the change from a college established for women to a university that is striving for diversity will affect the institution? While some groups celebrate the 50th anniversary of Title IX in 2022; as in the artwork (Figure 1) created by one of Michaelann’s students fulfilling a social justice studio assignment; it is under fire from other factions. The students were given a choice on the social justice topic that they were passionate about. Kerigan chose Title IX as she has found that being a female soccer player the opportunities are much different than her male counterparts, especially at the collegiate level. Elsesser (2022) reported that, “Women’s scholarships, leadership programs, awards, and even gym hours are being eliminated or canceled by universities because they discriminate against men. Complaints are being filed with the Department of Education (DOE) about programs and funding for women at universities across the country, and the DOE is taking action (para. 1). Furthermore,

Last year, Biden signed an executive order stating, ‘It is the policy of my Administration that all students should be guaranteed an educational environment free from discrimination on the basis of sex.’ It’s unlikely he was referring to eliminating scholarships and awards for women, but that seems to be an unintended effect of enforcing these codes (Elsesser, 2022, para. 11).

This is a very new and beginning story with the ending yet to unfold.

Unpacking Cheryl’s stories of experience

Cheryl’s early career story naturally brings to the fore the idea of society accommodating itself on the backs of those most present to be taken advantage of–with one of many of these groups being women. It furthermore shows how simultaneously advancing women and those who are minoritized advantaged some females to the disadvantage of other females–with all females ultimately being trumped by males who fell in only one category. This realization reminded Cheryl of her early research in Alberta schools. The principal with whom she worked spoke of principals like himself as “kingmakers” (Craig, 1999), which meant they prepared (male) assistant principals to be principals of other campuses. Cheryl never heard a parallel story of female principals being “queenmakers.” Cheryl’s first principal was male but the other five leaders she had were females. Perhaps it is safe to say that males’ kingmaking on their campuses had more effect in decision making processes than strong female principals and principal candidates who were not into a queenmaking secret story (Clandinin and Connelly, 1995), although they probably intuited male’s kingmaking efforts? Furthermore, cover stories were also at work as well. Cheryl’s age was used as a ruse for a systemic change happening in every sector of Canada. Only in retrospect could she locate what was happening personally to her to larger societal phenomena (gender equality, multiculturalism, bilingualism) unfurling throughout the educational system and around that nation.

Cheryl’s middle career narrative specifically relates to gender and how Cheryl’s award-winning research program could be judged by males in power in such a way that she could be denied entry into the scholarly community despite her strong eligibility (She had held the only fully funded Canadian post-doctoral fellowship in the country). At first, Cheryl bristled and resisted but then she fell silent, not wanting to fan the flames of gender inequity and controversy. She eventually learned that her chair had sent her file to some of the most influential figures in the field and that each of them—even her chair’s dean friend who conducted quantitative research—wrote eloquently in her favor. However, Cheryl remains awake to the fact that others whom her chair knew likely would not have been as generous in their evaluations.

In Cheryl’s recent story, she is a leading professor in the field of education nationally and internationally. Yet, she still faces challenges. When she shows initiative and applies for grants and/or is nominated by other women for awards, her achievements are likened to a display of excessive entitlement on her part. Rather than Cheryl receiving the same kind of respect as males leading the fields of education or the sciences would receive, she is accused of gaming the system through demanding awards and grants be given to her. Her hard work and cumulative academic record–in short, her merit–does not hold the same weight as males and those in the sciences.

Unpacking Gayle’s stories of experience

Gayle’s initial take on her early career experience with the male Latino principal who stated she had “no business teaching Hispanic children” was that the principal perhaps held a bias against white’s in the field, perhaps thinking that whites in bilingual education would look down on or be condescending toward Hispanic youth. Reflecting back and restorying the incident from a gender lens, however, yields a different perspective. The idea that the principal immediately challenged Gayle rather than engage her in conversation about the position and her experience seems to indicate that the principal had already determined that he would not hire Gayle, even before granting an interview. Whether the principal’s response was culturally, racially, and/or gender motivated is unclear. What is clear, however, is that he took what some would consider a stereotypical position of power and dominance, expressing himself in ways that he more than likely would not have done with a male teacher candidate, regardless of that male’s cultural or ethnic background.

The stories shared in Gayle’s middle career experiences illustrate the interplay between gendered experiences and perceived power of males over females in the workplace preceding the “Me, Too” Movement. Although these incidents might be viewed as microaggressions by some, the women’s reactions suggest situations that lead to poor and potentially intolerable workplace environments. The fact that none of the women in these incidents stepped forward at the time to make a formal complaint gives us insights into their fear of retaliation, both visible (loss of job, non-voluntary transfer to another school, poor evaluation) and invisible (being ignored, passed over for recognitions, supply requests delayed). In consulting with her male colleagues about concerning behaviors, it seemed to indicate the importance of women speaking up for themselves and for other women.

We now turn to Gayle’s recent career experiences in which she shares reactions of students and colleagues to her decision not to follow a tenure track position in higher education. Her personal choice indicates that she does not hold a “need” for power, perhaps because she has held positions of authority in the past. She has “been there,” and “done that.” At the same time, her current career pathway has removed or at least minimized perceived competition from male counterparts.

Implications for breaking the “glass ceiling”

Our stories of experience have deeper implications in the way women face inequities in the educational workplace and in academia as a whole. As published on May 9, 2023, “In a recording by a Galveston County Daily News reporter, [Galveston Independent School District] Superintendent Gibson allegedly called women ‘worker bees,’ who take care of the details of the project, but, ‘we need a man to push this through’ (Rose, 2023). This statement is a clear indication that gender stereotypes still exist in the education landscape. Although the author narratives presented here reflect progress in how women are perceived in the workplace, under the surface are long held perceptions of women and their place in society that remain to be grappled with.

The prospect of all women having the opportunity to break the glass ceiling in the near future is grim, yet every now and then a crack can be found and a colleague, friend, and/or acquaintance pushes through. We as an affinity group must celebrate these successes. And if we are lucky enough to be the one to break through, we must reach out to others and help them meet their challenges and dismantle barriers. Mentoring could be the key to crashing down the barriers that hold us hostage. Through a collaborative known as the Portfolio Group, Michaelann, Cheryl, and Gayle have been colleagues and friends for over 25 years, working together as critical friends. As each has communicated gendered experiences, their trusting relationships have allowed them to not only talk openly and transparently about their experiences but, importantly, to also mentor one another in the midst of challenging situations such as those shared here.

Conclusion

Arguably, society advances on the backs of those with the least power/those who are most available to be taken advantage of. Where education is concerned, females (among others) have frequently paid the price of progress. As the statistics in this article illustrate, women have been inequitably represented and treated over time. While there is strong evidence that this trend is still continuing, there also is evidence that the tide is starting to turn in academia. We catch glimpses of this in Cheryl’s middle career experience and Michaelann’s recent career experience. Cheryl reported how one male reviewer of her full professor tenure file acted in a way contrary to her department chair who expected his dean friend to act on the same prejudices as he did. Michaelann told of how structures put in place at universities around the country to help women achieve parity are being challenged. Currently teaching at a former women’s college which is now working to become a more diverse university, she seems to have more questions than answers now about gender and achieving equity than before. And Gayle was not able to intervene in her former male supervisor’s shenanigans. However, she was positioned strongly enough to take him to task for his actions. She also informed the female teachers that such behaviors were unacceptable and that they need not comply.

Another strong theme is that all three authors dealt with more easily identifiable gender issues as their careers advanced than they did in their early years when the issues were harder to pinpoint. One might surmise from this that as females rise in the ranks, they pose more of a threat to males who may see female advancements and rewards in school districts and universities as affronts to their dominance and superiority. As we contemplate this theme, we also consider the effects of societal changes on our profession, in some cases leading individuals to be more mindful of gender and age issues and in other cases leading individuals to be extremely subtle in their microaggressions–which are more easily identified due to our broader and deeper career experiences in the field of education.

While certain males in education are excessively entitled, it may very well be that many females and some males need to act more entitled. In short, they do not claim what should be part of their reputations (their entitlements) because they avoid issues with excessively entitled males (and females modeling those males) and ignore the amount of space they take up in their work milieus. Also, women like us, appear to be more invested in doing our work well than about how our accomplishments are storied. Furthermore, because males fill more leadership positions, female news and breakthroughs may not be made public in their places of work because others (certain males/females) may get jealous, which is how the failure to mention female accomplishments was explained by a male leader in a face-to-face discussion with one of us. In sum, progress has been made over the span of our careers. Still, finer-tune points remain in dire need of attention as our cumulative experiences successively show.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because narratives were developed from personal journals and not intended for public dissemination. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to gayle.curtis@att.net.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MK, CC, and GC contributed to conception and design of the study, as well as data analysis and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Association of University Professors (AAUP). (2018). The annual report of the economic status of the profession 2017–2018, Academe. Available at: https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/ARES_2017-18.pdf

American Association of University Women (n.d.) Fast facts: Women working in academia. Available at: https://www.aauw.org/resources/article/fast-facts-academia/

American Council of Education. (2017). Pipelines, pathways, and institutional leadership: Update on the status of women. Available at: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/HES-Pipelines-Pathways-and-Institutional-Leadership-2017.pdf

Asadi, L., and Ali, S. (2021). “A literature review of the concept of excessive entitlement and the theoretical informants of excessive teacher entitlement” in Understanding excessive teacher and faculty entitlement: Digging at the roots. Vol. 38. eds. T. Ratnam and C. J. Craig (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited), 17–34.

Belenky, M. F., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R., and Tarule, J. M. (1986). Women's ways of knowing: the development of self, voice, and mind. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Ben-Peretz, M. (1995). Learning from experience: memory and the teacher’s account of teaching. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Bichsel, J., and McChesney, J. (2017). The gender pay gap and the representation of women in higher education administrative positions: The century so far. A CUPA-HR research brief. Available at: https://www.cupahr.org/wp-content/uploads/cupahr_research_brief_1.pdf

Caine, V., Clandinin, D. J., and Lessard, S. (2021). Narrative inquiry: Philosophical roots. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (1990). Narrative, experience and the study of curriculum. Camb. J. Educ. 20, 241–253. doi: 10.1080/0305764900200304

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (1995). Teachers' professional knowledge landscapes. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (1998). Stories to live by: narrative understandings of school reform. Curric. Inq. 28, 149–164. doi: 10.1111/0362-6784.00082

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (2004). Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Colby, G., and Fowler, C. (2020). Data snapshot looks at full-time women faculty and faculty of color. Washington, DC: Academe Blog.

Conle, C. (2001). The rationality of narrative inquiry in research and professional development. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 24, 21–33. doi: 10.1080/02619760120055862

Connelly, F. M. (1995). “Foreword” in Learning from experience: Memory and the teacher’s account of teaching. ed. M. Ben-Peretz (Albany, NY: SUNY Press), 13–18.

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (1988). Teachers as curriculum planners: narratives of experience. New York, NY: Teachers’ College Press.

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (1999). Shaping a professional identity: stories of educational practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Craig, C. J. (1992). Coming to know in the professional knowledge context, beginning teachers' experiences. Calgary, Canada: University of Alberta.

Craig, C. (1995a). “A story of Tim’s coming to know sacred stories in school” in Teachers' professional knowledge landscapes. eds. D. J. Clandinin and F. M. Connelly (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 88–101.

Craig, C. (1995b). “Coming to know on the professional knowledge landscape: Benita’s first year of teaching” in Teachers’ professional knowledge landscapes. eds. D. J. Clandinin and F. M. Connelly (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 137–141.

Craig, C. J. (1999). Parallel stories: a way of contextualizing teacher knowledge. Teach. Teach. Educ. 15, 397–411. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00062-6

Craig, C. J. (2002). A meta-level analysis of the conduit in lives lived and stories told. Teach. Teach. 8, 197–221. doi: 10.1080/13540600220127377

Craig, C. J. (2010). “Reflective practice in the professions: teaching” in Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 189–214.

Craig, C. J. (2014). From stories of staying to stories of leaving: a US beginning teacher’s experience. J. Curric. Stud. 46, 81–115. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2013.797504

Craig, C. J. (2017). “Sustaining teachers: attending to the best-loved self in teacher education and beyond” in Quality of teacher education and learning. eds. X. Zhu, A. L. Goodwin, and H. Zhang (Singapore: Springer), 193–205.

Craig, C. J. (2020). Fish jumps over the dragon gate: an eastern image of a western scholar’s career trajectory. Res. Pap. Educ. 35, 722–745. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1633556

Craig, C. J., Curtis, G. A., Kelley, M., Martindell, P. T., and Perez, M. M. (2020). Knowledge communities in teacher education: Sustaining collaborative work. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave-MacMillan.

Craig, C. J., and Olson, M. R. (2002). “The development of teachers’ narrative authority in knowledge communities: a narrative approach to teacher learning” in Narrative inquiry in practice: advancing the knowledge of teaching. eds. N. Lyons and V. LaBoskey (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 115–132.

Craig, C. J., and Ratnam, T. (2021). “Excessive teacher/faculty entitlement in review: what we unearthed, where to from here” in Understanding excessive teacher and faculty entitlement (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing).

Elsesser, K. (2022). Women’s scholarships and awards eliminated to be fair to men. Jersey City, NJ:Forbes.

Gallop, C., and Chomorro-Premuzic, P. (2022). Stop criticizing women and start questioning men instead. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2022/04/stop-criticizing-women-and-start-questioning-men-instead&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1656769776071742&usg=AOvVaw0A7Boky4DW_8oeHb_l1XoB

Gilligan, C. (1977). In a different voice: Women's conceptions of self and of morality. Harv. Educ. Rev. 47, 481–517. doi: 10.17763/haer.47.4.g6167429416hg5l0

Gilligan, C. (1993). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C., Lyons, N., and Hanmer, T. (1990). Making connections: The relational worlds of adolescent girls at Emma Willard School. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goodson, I. (2009). “Listening to professional life stories: some cross-professional perspectives” in Teachers' career trajectories and work lives (Dordrecht: Springer), 203–210.

Hopkins, N., Reicher, S., Stevenson, C., Pandey, K., Shankar, S., and Tewari, S. (2019). Social relations in crowds: recognition, validation and solidarity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 1283–1297. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2586

Kelley, M., Craig, C. J., Martindell, P. T., and Curtis, G. A. (2021). Impact of career challenges and obstacles on educators’ lives: a collaborative narrative inquiry. American Educational Research Meeting.

Kelley, M., Gray, P. D., Reid, D. J., and Craig, C. J. (2010). “Within K-12 schools for school reform: what does it take?” in Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry. ed. N. Lyons (Springer), 273–298.

Lodewick, C. (2022). “The great resignation could last for years, says the expert who coined the term,” in Fortune. Available at: https://fortune.com/2022/04/04/great-resignation-could-last-years-expert-says/ (Accessed April 04, 2022).

Lyons, N. (1998). With portfolio in hand: Validating the new teacher professionalism. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lyons, N. (Ed.) (2010). Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry: Mapping a way of knowing for professional reflective inquiry. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Lyons, N., and LaBoskey, V. K. (Eds.) (2002). Narrative inquiry in practice: Advancing the knowledge of teaching. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Meho, L. I. (2021). The gender gap in highly prestigious international research awards 2001-2020. Qual. Sci. Stud. 2, 976–989. doi: 10.1162/qss_a_00148

Monroy, M. B., Ali, S., Asadi, L., Currens, K. A., Davoodi, A., Etchells, M. J., et al. (2021). “Entitlement in academia: multiperspectival graduate student narratives” in Understanding excessive teacher and faculty entitlement (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing).

Newman, K. (2022).Women in academia: have we really come a long way? Available at: https://thefulcrum.us/big-picture/Leveraging-big-ideas/women-professors

Olson, M. R., and Craig, C. J. (2005). Uncovering cover stories: tensions and entailments in the development of teacher knowledge. Curric. Inq. 35, 161–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2005.00323.x

Ratnam, T., and Craig, C. J. (2021). “Introduction: the idea of excessive teacher entitlement: breaking new ground” in Understanding excessive teacher and faculty entitlement (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing).

Rose, S. (2023). Galveston ISD superintendent resigns after controversial remarks made. Available at: https://www.fox26houston.com/news/galveston-isd-superintendent-resigns-after-controversial-comments-made

Schwab, J. (1956/1978). “Science and civil discourse: The uses of diversity,” in Science, curriculum and liberal education: Selected essays. eds. I. Westbury and N. Wikof (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 133–148.

Schwab, J. J. (1973). The practical 3: translation into curriculum. School Rev 81, 501–522. doi: 10.1086/443100

Uzi, B. (2019). “Research: women are winning more scientific prizes, but men still win the most prestigious ones,” in Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/02/research-women-are-winning-more-scientific-prizes-but-men-still-win-the-most-prestigious-ones#:~:text=Employee%20retention-,Research%3A%20Women%20Are%20Winning%20More%20Scientific%20Prizes%2C%20But%20Men%20Still,awards%20given%20over%20five%20decades

Vincent-Lancrin, S. (2008). The reversal of gender inequalities in higher education: an ongoing trend. Higher education to 2030. OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/41939699.pdf

Keywords: narrative inquiry, gender issues in education, identity, gendered selves, cover stories, experiential narrative

Citation: Kelley M, Craig CJ and Curtis GA (2023) Examining gender issues in education: exploring confounding experiences on three female educators’ professional knowledge landscapes. Front. Educ. 8:1162523. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1162523

Edited by:

Dolana Mogadime, Brock University, CanadaReviewed by:

Renee Moran, East Tennessee State University, United StatesMary Saudelli, University of the Fraser Valley, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Kelley, Craig and Curtis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gayle A. Curtis, gayle.curtis@att.net

Michaelann Kelley

Michaelann Kelley Cheryl J. Craig

Cheryl J. Craig Gayle A. Curtis

Gayle A. Curtis