Precarious positions: glass ceilings, glass escalators, and glass cliffs in the superintendency

- 1Department of Education Leadership, Management, and Policy, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ, United States

- 2Department of Educational Leadership and Policy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

Introduction: The “glass cliff” phenomenon has been observed in many fields; in these situations, women are hired into prestigious, but precarious, leadership positions. In education, little is known about the preexisting district contextual trends into which women leaders are hired, and thus whether a glass cliff might exist in the superintendency. This study explores descriptively whether evidence suggests superintendents in New Jersey might be differentially sorted into “precarious” districts across gender.

Methods: Our study utilizes a newly created statewide longitudinal data set to examine descriptive trends in superintendent placement, including multiple measures of precarity. We investigate the presence of the glass ceiling by examining representation in the superintendency, the glass escalator as evidenced by leader qualifications, and the glass cliff as indicated by district characteristics.

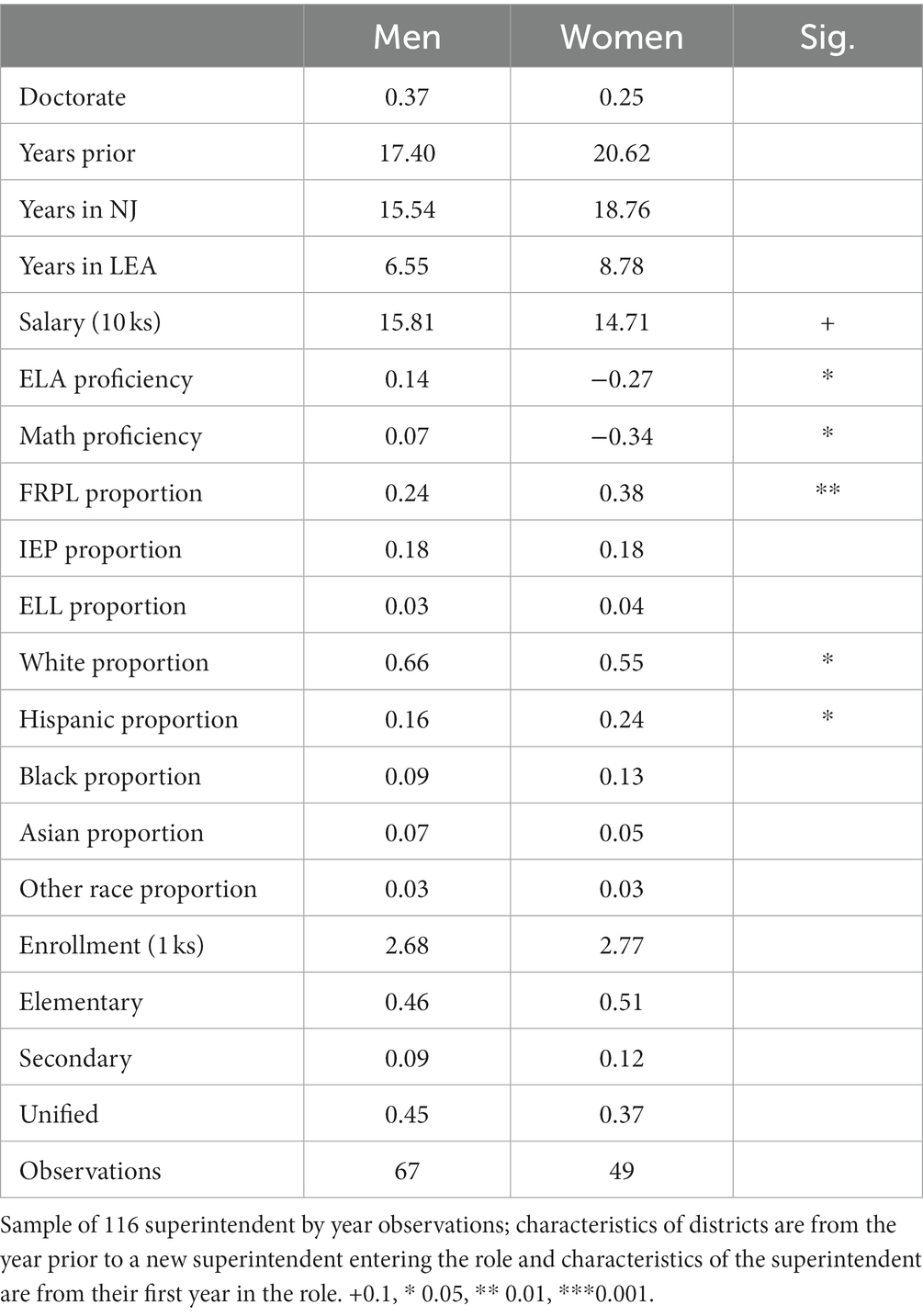

Results: New Jersey employs a higher proportion of women superintendents than the national average. Men and women superintendents are equivalently qualified, on average, though women tend to be paid less. We find that male and female superintendents in the state work in somewhat similar districts, though women are more likely to lead districts serving students from low-income communities and larger proportions of minoritized students.

Discussion: These findings suggest women superintendents in New Jersey are excelling despite serving communities that are often under-resourced. Thus, there is some suggestion of a glass cliff phenomenon in education leadership, as women who obtain the highest positions are also in more precarious settings.

Introduction

The “glass cliff” phenomenon has been observed in many fields (Ryan and Haslam, 2005; Cook and Glass, 2013; Ryan et al., 2016; White, 2023); in these situations, women are hired into ostensibly prestigious, but precarious, leadership positions. The concept was first introduced by Ryan and Haslam (2005) to describe the possible relationship between the appointment of women board members in business leadership positions and firm performance; while narratives between performance and women holding these prestigious positions sometimes appeared to paint women leaders in a negative light, Ryan and Haslam (2005) found no measurable differences in performance after a man or woman was added to the board given pre-hiring trends. Instead, their research suggested disparities in the circumstances into which men and women are hired into board leadership, and how performance is attributed to men and women given those disparities in pre-existing firm performance (Ryan and Haslam, 2005, 2007). Specifically, women were more likely to be hired to firms that were already experiencing downward performance trends, and negative performance is often attributed to the personal characteristics of leaders rather than the circumstances in which they took the role (Kulich et al., 2007).

The metaphor of the glass cliff builds on the earlier metaphors of a glass ceiling and a glass escalator used to describe gender disparities in leadership positions across industries. The glass ceiling (Morrison et al., 1987) is the most widely observed and well-known phenomenon, where women find top positions elusive (e.g., company CEO, president of the United States, district superintendent). The glass escalator describes the seemingly smooth path men may experience in moving through leadership hierarchies in fields dominated by women, such as education (Williams, 1992). In addition to the glass ceiling and glass escalator, women who reach the highest levels of leadership may also be confronting a glass cliff (Ryan et al., 2016). When women do gain access to leadership positions, those positions may be more precarious than those their male colleagues hold. Women being more likely to be hired to boards of firms already on a downward trajectory, and then often blamed for the continuation of that negative performance (Ryan and Haslam, 2005), suggests evidence of a glass cliff phenomenon of women reaching ostensibly prestigious positions that are in reality more precarious than those held by men.

Little research has explored the idea of precarious positions in education. Smith (2015) defines a school district to be more precarious if it serves students and communities with a greater diversity of needs and fewer resources. Additionally, federal and state policies that require districts to report student demographic and achievement information to the public may also shape perceptions regarding the prestige and precarity of various leadership positions (McGhee and Nelson, 2005). Women leaders may be more likely to be hired to more precarious positions, and if women leaders “fail,” they may also be subject to more harsh criticism and individual blame than men. In education, little is known about the preexisting district contextual trends into which women leaders are hired, and thus whether a glass cliff might exist in the superintendency.

We model this paper after the foundational research of Ryan and Haslam (2005) in the corporate world to examine the possibility of the glass cliff phenomenon in K12 education leadership. As in business, historically we see a lack of women in leadership roles in education, particularly at the district level. While approximately 80% of teachers in United States public schools are women (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022), about half of principals in the United States are women, and only around a quarter of superintendents are women (Finnan and McCord, 2017; Robinson et al., 2017; Tienken, 2021; White, 2021, 2023). The superintendency, the highest position in district leadership, was originally conceived of as a managerial position and considered “men’s work” for decades, with women holding only 1% of all superintendencies even into the early 1980s (Robinson et al., 2017). In fact, some research has suggested that the position structurally disadvantages women from attaining and succeeding within the position (Mahitivanichcha and Rorrer, 2006). While the proportion of women holding the position has risen notably, these gains have plateaued in the past few decades (Björk et al., 2005; Glass and Franceschini, 2007).

Two primary arguments for having greater representation of women in leadership positions emphasize normative and efficiency goals. The normative (or moral) argument is that women and men should have equal representation in seats of authority and power because men and women are equally represented in the population; there is an ethical obligation on the part of society to ensure equitable access to power. In fields that are overrepresented by women, such as education, leadership inequities are particularly glaring because the most qualified for advancement are likely those with experience in the field (Schein, 2001; Mahitivanichcha and Rorrer, 2006). The efficiency argument suggests that disparities between men and women in the position indicate possible bias in hiring, with selection into leadership being at least partially based on gender rather than solely upon applicant qualifications for the position (Tallerico, 2000; White, 2023). Thus, instead of hiring the best candidate for the leadership position, bias in hiring leads to an inefficiency, as the organization potentially hires a less qualified candidate. While research suggests women leaders provide unique value to students and teachers (Grogan, 1996; Grogan and Shakeshaft, 2013; Robinson et al., 2017; Zenger and Folkman, 2019), and these contributions are certainly worthy of study, we here highlight the fundamental arguments regarding representation as a part of the systemic structures emphasizing the gender disparities in education leadership.

When women do take on leadership positions, evidence suggests women tend to be more likely to work in districts serving students with more diverse needs (e.g., students with disabilities, English learners, students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch; White, 2023). These student and district demographic characteristics are also typically associated with lower academic achievement as measured by traditional metrics (e.g., standardized assessments, graduation rates), reflecting inequitable access to resources, and these districts may be considered more challenging, and therefore more precarious (McGhee and Nelson, 2005). We extend prior work on glass ceilings, escalators, and cliffs phenomena to education, examining whether we can find evidence of these structures among New Jersey’s education leaders and their career trajectories.

Women may not hold superintendent positions for many reasons, and we do not attempt to account for all of the many complicated factors affecting those decisions in this study (e.g., professional interest, personal commitments, bias in hiring). Still, we have limited evidence exploring whether there are systematic barriers to women holding executive leadership positions or women only getting access to leadership in the most challenging and struggling districts, and further research is needed to understand whether and under what conditions we find evidence for structural phenomena that are associated with inequalities in leadership across gender. Importantly, “a company’s poor performance could be a trigger for the appointment of women to the board” (Ryan and Haslam, 2005), and it is possible that a similar phenomenon is found in education. Women may be more likely to be hired into more precarious district leadership positions. These differential hiring decisions could impact representation in the superintendency and tenure within the superintendency. As women pursue leadership positions within schools and districts, their aspirations are impacted not only by the important questions facing all educators considering leaving the classroom for administration; in addition, women leaders must meet the gendered expectations associated with leadership, and they may be working in more precarious settings, in part because of those gendered expectations.

In this study, we consider the representation of women within executive school district leadership positions (the glass ceiling), the extent to which men hold these positions with comparable qualifications to women (the glass escalator), and the differences in the observable characteristics of the districts they serve (the glass cliff). Our study utilizes a newly created statewide longitudinal data set to examine descriptive trends in superintendent placement, student demographic features, and academic achievement as measures of precarity. Specifically, we investigate the following research questions:

1. To what extent are women represented in the superintendency?

2. To what extent do women and men in the superintendency have differing qualifications?

3. Do the demographic characteristics of districts differ by superintendent gender?

We examine the types of districts women and men superintendents serve as well as their qualifications for the position. We then compare these districts on multiple possible indicators of position precarity, including student achievement and demographic characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, eligibility for free or reduced-price meals, and classification as an English Learner or student with an individualized education plan), as well as leader compensation.

Importantly, we acknowledge that this binary approach to examining gendered trends is not inclusive of gender nonconforming and nonbinary leaders. While not in the scope of this study, we recognize that transgender and nonbinary educators have been largely erased from the research literature, and we hope the questions we raise about women in the superintendency provide an opportunity for broader questions to be raised regarding conceptions of gender and educational leadership.

Literature review

Glass ceilings, escalators, and cliffs

Among the many metaphors used to describe women in leadership, the idea of a glass ceiling has been particularly powerful (Morrison et al., 1987). The notion of a glass ceiling succinctly captures how invisible forces ostensibly prevent women from rising to top positions of leadership. Well into the early 2000s, evidence suggested the glass ceiling was an immovable reality, but slowly, gender diversity started to expand in top leadership positions in public and private organizations (United States Government Accountability Office, 2010). Women occupy more leadership positions today than ever before, prompting many to suggest that the glass ceiling has been shattered (Muther, 2022; Salamy, 2022; Wattles, 2023). However, despite the increased representation of women in leadership, women still lag woefully behind men in executive positions (Warner et al., 2018). Though women comprise almost half of the overall workforce in the United States, only about 42% of managers are women, a number that has not changed much in the last decade (Government Accountability Office, 2022). In many fields, the lack of representation at the highest levels of management is even more striking. For example, about 45% of law associates are women, but only 19% of partners, women hold fewer than a quarter of the seats in the United States House and Senate, and only 5% of Fortune 500 CEOs are women (Warner et al., 2018). The glass ceiling phenomenon appears to persist in many fields.

Relatedly, the glass escalator is a metaphor used to describe the phenomenon of men receiving preferential treatment in fields in which women make up the majority of the labor force, such as nursing, social work, and education (Williams, 1992). Advancing to leadership in education has been a prime example of this phenomenon. Women make up approximately 80 % of all teachers, but they make up only 50 % of all principals and just a quarter of all superintendents (Finnan and McCord, 2017; Robinson et al., 2017; Tienken, 2021; White, 2021, 2023). The glass escalator phenomenon suggests men are encouraged to pursue higher positions in these fields regardless of personal interest and motivation. Additionally, the tendency for men to hold more supervisory positions within these fields may contribute to other men’s promotion, which can lead to increased mentoring opportunities and the tapping of future leaders who are then provided additional advantages (Grissom and Keiser, 2011; Myung et al., 2011; Bowers and White, 2014).

Building on these metaphors used to describe the gendered labor market forces that create these disparities, Ryan and Haslam (2005) introduced the notion of a glass cliff, which describes the experience of some women being more likely to be hired into more precarious leadership positions upon the opportunity to rise to leadership. Specifically, women may be more likely to be brought into seemingly prestigious leadership positions in organizations that are actually facing particularly challenging circumstances. Building on the research of Schein (2001), Ryan and Haslam (2007) suggested that the old bias of “think manager-think male” had developed a complimentary bias of “think crisis-think female” where an organization experiencing turmoil might look to women to provide leadership that is different from men. Ryan et al. (2011) suggest women leaders are preferred in these situations because they are seen as being better at managing people and because they are then positioned to take the blame for the organizational failure. The consequence of these biases is men being hired to more stable leadership positions while women are hired to organizations already experiencing lower performance. Thus, women leaders may be more likely to lead organizations while they are in crisis, putting them in more challenging leadership positions. In education, these challenges may be related to increased scrutiny and/or resource constraints, which has been heightened in the school accountability era that has placed increased emphasis on standardized achievement scores, and resulted in school leaders working with students of marginalized identities to be villainized and even more likely to turn over (McGhee and Nelson, 2005; Mitani, 2018).

Ryan and Haslam (2005) were responding to a newspaper article that suggested women in leadership may be a hindrance to the performance of firms; that article (Judge, 2003) suggested that a recent uptick in women being hired to the boards of firms was related to lower performance of those firms. To the contrary, Ryan and Haslam (2005) argued that the article failed to account for the pre-existing trends of those firms prior to the women being hired to the boards. They found that women were more likely to be hired into boards of firms that already had a trend of lower performance in the 3 months prior to the hire. Since Ryan and Haslam’s (2005) initial study, several other researchers have found additional evidence of the glass cliffs phenomenon in the corporate field (Brady et al., 2011), as well as in other fields and with other minoritized identities (Cook and Glass, 2013; Smith, 2015; Bornat et al., 2018). For example, Cook and Glass (2013) found that people identifying as a minoritized race or ethnicity were more likely to be hired into precarious positions. Bornat et al. (2018) found evidence of a glass cliff for women in United Kingdom politics, with women being more likely to be raised to local or national party leadership when the party is performing poorly. As women consider pursuing leadership positions, they may face gendered expectations in the recruitment and hiring process that affect their promotion; additionally, when selected, women may actually be even more likely to be serving organizations in more precarious settings than their male colleagues.

Glass cliffs in education

The notion of glass cliffs has been underexplored in public organizations, and only two peer-reviewed studies we know of have explored the concept of glass cliffs in education (Smith, 2015; White, 2023). Smith (2015) uses a sample of public school principals surveyed through the National Education Panel Survey (NEPS) administered in both 2002 and 2004 to estimate the relationship between the percent of women in the principalship within a district in 2004 and multiple school district demographic characteristics. They found higher percentages of students with limited English proficiency, out of school suspensions, and gifted and talented supports in a district were associated with larger percentages of women in the principalship. They argue diversity of student need may result in a more challenging work environment and a potentially precarious position for women leading in those districts (Smith, 2015).

While Smith’s (2015) study provides important evidence regarding the glass cliff and gendered sorting of women in leadership into districts, the study raises additional questions for exploration. First, district conditions may be connected to differences in the proportion of women in the principalship, and district-level characteristics (e.g., district percentages of students with limited English proficiency) may be more directly related to the precarity of the role of superintendents rather than principals, since schools may differ substantially within districts. Second, the NEPS does not include any measures of academic performance nor other measures of diversity such as economic or racial/ethnic diversity that may also be associated with more challenging positions. Our study aims to build on Smith (2015), addressing these limitations by exploring descriptively if and how evidence exists suggesting the presence of the glass cliffs phenomenon in the superintendency.

White (2023) directly examines the possibility of the glass cliff phenomenon in the superintendency, focusing on turnover rates by gender using a new national, longitudinal data set of superintendents. White’s (2023) work emphasizes the persistent glass ceiling effect across the United States, with a very slight narrowing of the gender gap in the superintendency from about 74% in the 2019–2020 school year to 72% in 2022–2023. While turnover is slightly more common among men, they find the newly open positions are not particularly likely to be filled by women. Importantly, White (2023) notes that improvements in closing the gap are likely driven by a small number of states with particularly high representation of women in the position, such as New Jersey. Building off this work, in this study we focus on this particular state as a possible exemplar. Additionally, while White (2023) considers student demographics as predictors for turnover, we are also able to consider superintendent qualifications, as well as look across district types, when considering possible gender disparities. We also examine first-year superintendents for a closer look at the conditions into which leaders are hired.

Gender bias and precarity of leadership in education

Although the research on glass cliffs in education is limited, research on gender bias in educational leadership has been relatively robust. Several studies exploring the pipeline to school leadership have found evidence to suggest that women are proportionally less likely to advance to leadership (Ringel et al., 2004; Fuller et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2017; Grissom et al., 2020) and tend to take longer to reach the principalship (Bailes and Guthery, 2020). Moreover, when women reach the principalship they are often placed in elementary schools, but secondary school leadership is seen as a gatekeeper on the path to the superintendency (Bailes and Guthery, 2020). Recent reports suggest the proportion of women in the superintendency has increased in the past few decades, but it lags far behind the proportion of women in education and women in the population (Finnan and McCord, 2017; Robinson et al., 2017; Taie and Goldring, 2020; Thomas et al., 2023). Additionally, women are more likely to enter the superintendency later in their careers, and women leaders are typically paid less, on average, than men (Grissom et al., 2021). Research suggests the structure of the role and gendered perceptions of leadership may be key contributors to women being disadvantaged in applying for and being hired to the superintendency (Mahitivanichcha and Rorrer, 2006).

Defining the “precarity” of educational positions is a fraught endeavor in education research. Although scholars generally agree that schools with a larger share of students needing more intensive educational supports tend to be more challenging to lead, many scholars have challenged the deficit framing of having more students of color and students in poverty as being necessarily more difficult for schools (Ladson-Billings, 2006). Importantly, structural issues create conditions that make it more difficult for students in poverty, students of color, and other minoritized students to succeed academically (Darling-Hammond, 2004; Dee, 2005; Ladson-Billings, 2006). This research has highlighted how the era of accountability has been particularly negative for schools and districts serving large proportions of marginalized students, as accountability metrics tend to confirm existing biases about the quality of schools (Darling-Hammond, 2007; Noguera, 2008).

While this scholarship regarding the rhetoric used to describe schools is important, the literature also suggests that there are material consequences to leading schools and districts that tend to have lower levels of academic achievement and higher proportions of marginalized students. For example, Grissom and Bartanen (2019) find that principals are more likely to turnover and specifically exit public education or be demoted when they lead schools that have lower levels of achievement. Smith (2015) argues having more diverse student needs in a school district should be more challenging to lead than school districts with more homogenous student populations.

Given this evidence, we define precarious school districts primarily as those with higher proportions of students of color and students in poverty and lower academic achievement as compared to the state average. We do so not because of the students but because of the structures that maintain the lower academic achievement of marginalized students. Though this is a rhetorical difference, we believe it is important to make this distinction because we do not want to perpetuate a deficit framing of districts serving predominantly marginalized students. It is precisely because the students in these school districts are marginalized that leading these school districts may be more challenging than leading school districts with structural advantages due to the wealth and whiteness of the students. Moreover, empirical research and anecdotal experiences of school leaders suggest that accountability pressures often result in the loss of prestige of positions, additional job stress, and greater likelihoods of turnover (McGhee and Nelson, 2005; Mitani, 2018).

In addition to achievement, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, we consider the proportion of English Learners (ELs) and students with individualized education plans (IEPs) as possible contributors to position precarity given their inclusion in federal and state policy mandates. Additionally, New Jersey, like some other states, has many districts serving only students in some configuration of grades pk-8. We capitalize on this district structure and also examine representation in elementary school district leadership as a possible indicator of position precarity, as leading elementary school districts is associated with lower salaries and lower likelihoods of advancement to more prestigious and higher positions (Bailes and Guthery, 2020; Grissom et al., 2021), and women may face an additional burden of making visible this often overlooked role (Garn and Brown, 2008). Finally, we consider compensation as a possible indicator of precarity, as it may be representative of a larger trend of limited resources in the district.

Materials and methods

Data

New Jersey offers a unique research setting as a diverse state consisting of around 600 districts, employing a larger proportion of women superintendents than average across the United States, about 34% in the state compared to around 25% nationally (Tienken, 2021; White, 2023). The New Jersey state department of education (NJDOE) provides publicly available data regarding the academic performance of its school districts as well as student demographic information and personnel data. The data for this study come from the NJDOE public files for the 2016/2017 to 2018/2019 school years. These include personnel data on staff (described below), demographics of students, and the academic achievement of students. We include all traditional public and charter districts. Regional school districts, vocational districts, and special education jointure districts are excluded from all analyses, as these non-traditional districts had substantial missing and/or inconsistent data on variables of interest.

The staff data are particularly important to this study in examining possible glass ceilings, escalators, and cliffs. These data include the names of staff, the schools and districts to which they are assigned, their job codes, their highest degree earned, and their years of experience as educators, within the state of New Jersey, and within the LEA (i.e., district). Notably, the gender of staff is not included in the public data. Therefore, we assigned gender to superintendents using three sources of data. The first was the Social Security Administration’s lists of popular names by decade1 for boys and girls to determine common names by gender, as suggested by White (2023). We used the lists for the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. This timespan covers the most likely birth years for current superintendents. Second, we used the public directory2 of school districts in New Jersey that included the names of superintendents. The public directories often include a title (e.g., Mr., Ms., Mrs., Dr.) for the superintendents of those districts, and we used the gendered titles provided in those directories to assign the gender of superintendents. Lastly, we conducted a web search to find documentation from district websites, social media (e.g., LinkedIn, Facebook), or district board meeting minutes that may identify the gender of superintendents when necessary. Using these three sources we were able to identify the gender of all superintendents in our sample (N = 1,644 superintendent by year observations). We exclude superintendents from non-traditional districts as described above and those districts with incomplete data yielding a final sample size of 1,509 superintendent by year observations.

Like gender, the state considers educator race/ethnicity to be private employee information, and thus does not provide that data. While an intersectional approach considering how race/ethnicity and gender are related in shaping prospective leaders’ experiences would be relevant and important, we are unable to examine those trends in this study.

Although the majority of districts included only one superintendent per district-year, there were cases where a district may have more than one superintendent listed in the personnel data. When this was the case, we identified a primary superintendent for that district-year by examining the fulltime equivalency and salary for each, as well as the superintendent that was in the role the prior year. Additionally, some superintendents in New Jersey lead more than one district. In these situations, we checked to make sure that a superintendent could reasonably drive to the other district office within one hour. If this was the case, we considered the same name to be connected to the same person. If the name was relatively common, we used a web search to confirm the identity of the superintendent. Therefore, the 1,509 district-year observations are superintendents across the state; a single leader may appear up to three times across years. Across all years of the data set, there are 636 unique superintendents.

Again, the NJDOE staff data includes personnel information regarding superintendent educational attainment and experience, which we use to establish any differences in educator qualification to examine the possibility of a glass escalator phenomenon. We dichotomize educational attainment as either having obtained a doctoral degree or not, as a master’s degree is required for superintendent certification in the state and very few superintendents hold only a bachelor’s degree. Years of professional experience are provided at the state and district level as well as overall years as an educator. Educator salary has been adjusted for cost of living according to the CPI Inflation Calculator3 provided by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics; all salary statistics are presented in constant 2019 dollars. We exclude superintendents whose reported salary is lower than $50,000 as implausible and likely misreported.

NJDOE school report card data contain district characteristics including student enrollment for all groups mandated by federal reporting requirements; we focus specifically on student race/ethnicity, students with disabilities, English learners, and students who qualify for free or reduced-price school meal programs. New Jersey is a diverse state; given the variability of diversity across districts, we examine enrollment of students identified and categorized as white, Latinx/Hispanic, Black, Asian, and those in multiple and/or other categories. Average district achievement in both English/Language Arts (ELA) and mathematics are also reported. We also categorize the districts by the grades they serve. About half of districts serve students in some combination of grades pre-kindergarten through eight, about 12% serve students in grades nine through 12, and almost 40% of districts are unified, serving all grade levels or some other grade span across the two.

Methods

We provide rich descriptive statistics regarding superintendents in New Jersey and the districts they serve. First, we consider the possibility of a glass ceiling effect by examining the representation of women in the position. Second, we describe leader qualifications for superintendents to examine the possibility of a glass escalator. Third, we describe multiple district characteristics that may be associated with precarity, including student achievement and district demographic characteristics, to investigate a possible glass cliff. We describe each variable of interest for the state overall as well as by gender, and we use t-tests of means to measure whether men and women differ meaningfully on each. For comparisons of all districts across men and women in the superintendency, we provide repeated cross-sectional analyses for each year of available data. We also perform a subset of analyses on new superintendents in their first year in a particular superintendency to examine qualifications and district characteristics at the time of hire. These new hires may or may not have served as superintendents previously; in these supplemental analyses, we consider conditions at time of hire separate from the conditions in which superintendents work throughout their tenure. We present pooled results because we have to drop 1 year of data to identify superintendents that are new to the position.

Results

We have organized the presentation of our findings according to our three research questions. We first describe the representation of women in the superintendency and superintendent qualifications by gender to examine possible evidence of glass ceiling and glass escalator phenomena. We then explore differences in the school districts men and women superintendents serve to consider the possibility a glass cliff phenomenon may also be present. We include multiple district characteristics, highlighting student achievement and the representation of specific student groups identified by federal policy as historically underserved, and therefore potentially indicative of demographic characteristics community members and others might perceive as associated with more precarious positions. We describe mean differences between men and women superintendents overall as well as for new superintendent hires. Our findings suggest the presence of all three phenomena, with women underrepresented in the superintendency overall, despite being equivalently qualified, and being overrepresented in more precarious district settings.

RQ1: evidence of a glass ceiling

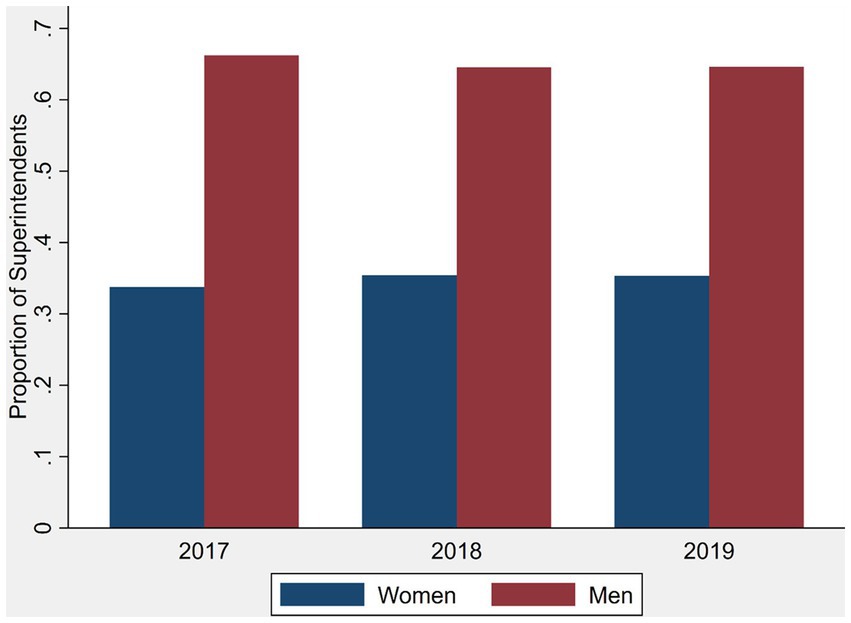

Women superintendents are well-represented across New Jersey public school districts in comparison to the nation as a whole. Women held over a third of all superintendent positions over the 3 years in the sample, holding almost 34% of positions in 2017, and just over 35% in the latter 2 years (Figure 1); women therefore hold a higher proportion of superintendent seats than most estimates of gender representation in the role across United States public school districts by about 10% (Finnan and McCord, 2017; Robinson et al., 2017; Tienken, 2021; White, 2021, 2023). Still, while these statistics are promising in suggesting women may face fewer barriers in achieving the highest level of district education leadership in New Jersey, women still hold fewer executive leadership positions than their representation in the teaching or principal workforce might suggest, and men tend to work in districts regarded as more prestigious (e.g., upper grades or unified).

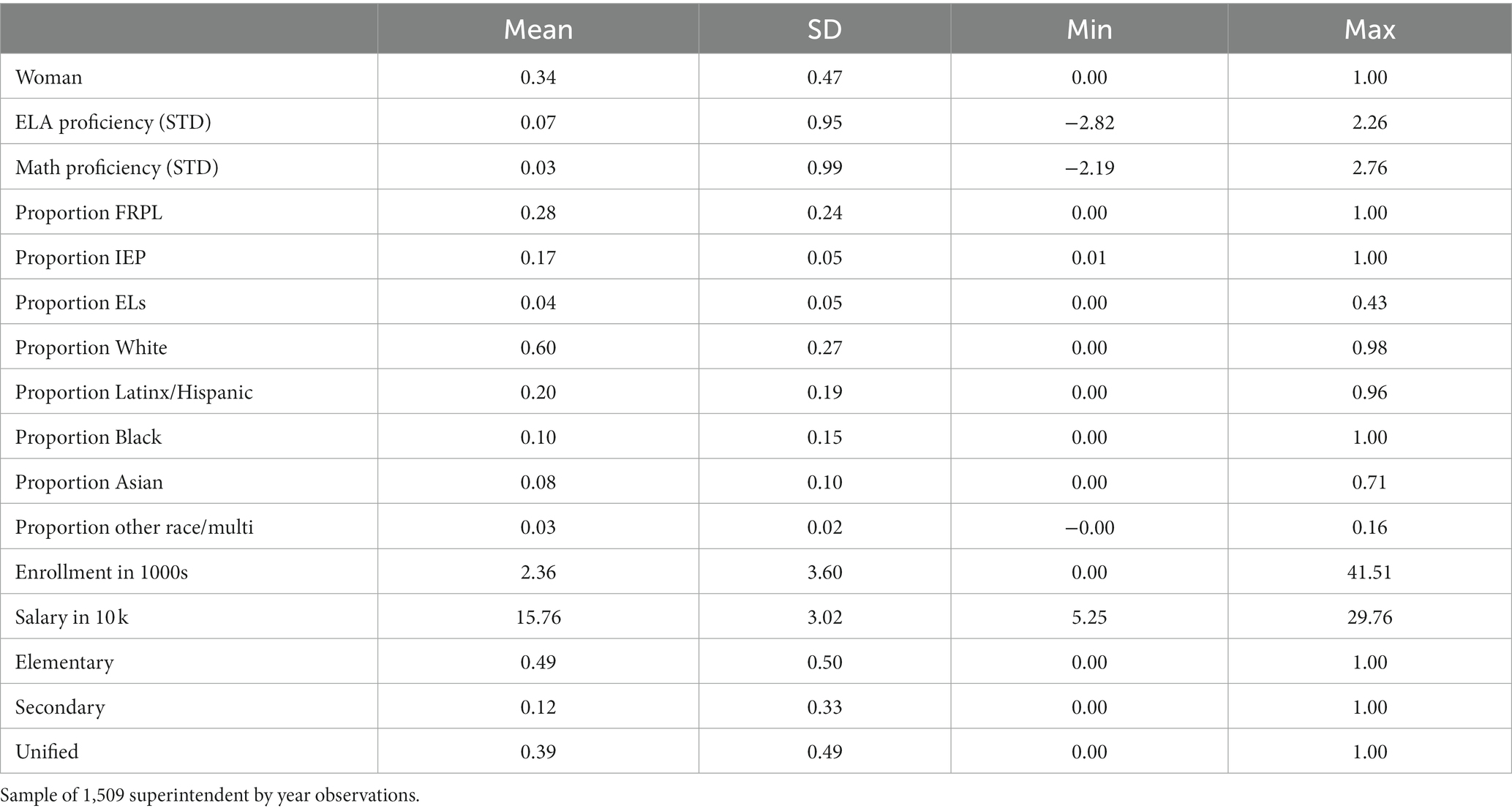

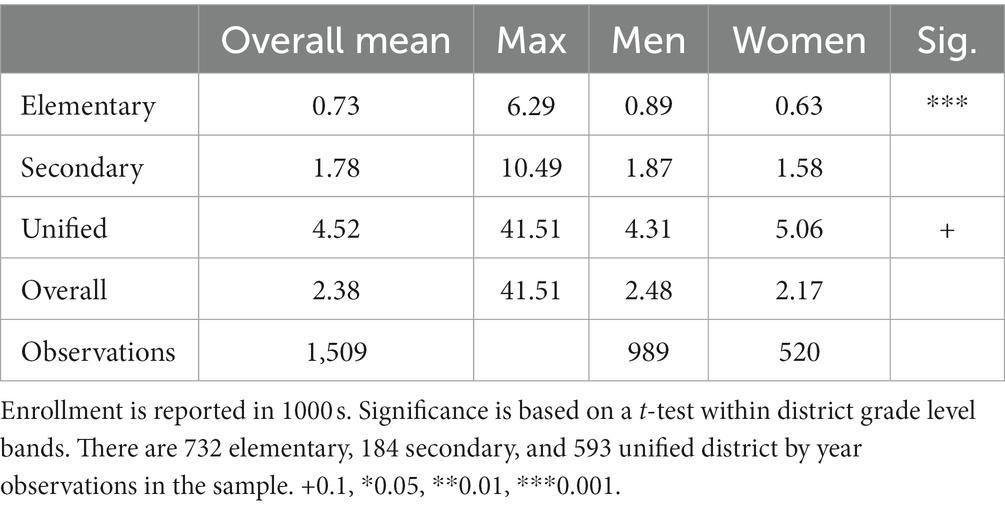

Women’s representation across district types varies greatly, mirroring that of the principalship. Only about 40% of New Jersey school districts serve students in kindergarten (or pre-k) through high school. About half of all districts only serve students in grades 8 and below (with many configurations, such as k-8, k-6, 4–8, etc.), and about 12% of districts serve only high school grades (see Table 1). Women are much more likely to serve in lower grade districts than in high school or unified districts, with about 56% of women superintendents leading elementary districts (not shown). Still, men are more likely to lead all district types; they hold about 60% of elementary positions, and around 70% of secondary and unified superintendencies (see Table 2). Elementary positions are typically seen as less prestigious than those serving older grades or unified districts (Bailes and Guthery, 2020); thus, women’s comparative overrepresentation in those positions may actually be additional evidence of a glass ceiling effect, where women can get close to the highest positions, but still often find themselves in a position just a rung lower.

Within district type, women and men superintendents serve districts of similar enrollment, on average. As of 2019, districts serving only the lower K8 grades tend to be smallest, though there is much variability in district size; while the average lower grade district serves around 730 students, the largest district serves over 6,000 (see Table 3). High school grade-level districts are slightly more than twice as large as elementary, on average, with over 1,700 students enrolled; again, much variability is observed, with the largest high school districts serving over 10,000 students. Unified districts, on average, enroll more than twice the average number in high school districts, over 4,000 students across grades pre-k through grade 12. While men lead slightly larger districts, on average, the difference is not statistically significant. Examining enrollment differences across district type, we find that men tend to hold lower-grade superintendencies enrolling statistically significantly higher numbers of students than women (890 vs. 627), and higher numbers in upper-grade schools, though not statistically significant. Women leading unified districts tend to enroll about 700 more students than men, about 15% of enrollment. While only statistically significant at the p < 0.1 threshold, this difference may indicate these district settings are substantively different to lead.

Given the representation of women in the superintendency throughout the state overall as well as when examining the different district types, New Jersey compares positively with much of the country, as over a third of superintendents are women. However, there still seems to be some sorting by gender into district grade types, and this higher proportion of district leaders is still of course not comparable to the larger educator workforce. Thus, this level of representation nonetheless suggests evidence of a glass ceiling in the superintendency in the state.

RQ2: evidence of a glass escalator

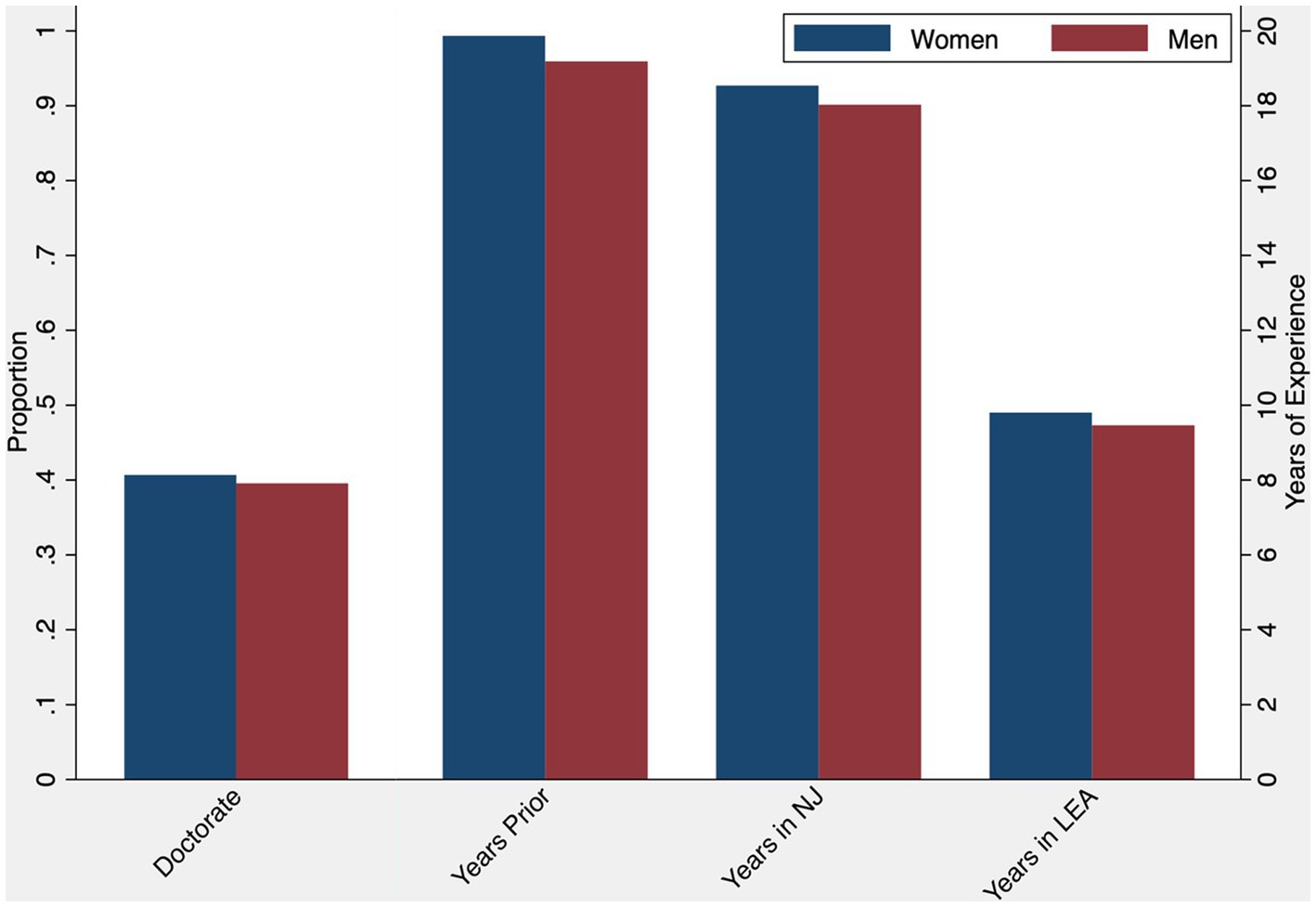

Men and women superintendents are similarly qualified, on average. About 40% of superintendents across the state hold a doctorate (see Figure 2). Women superintendents hold doctoral degrees at slightly higher rates than men, with 40.67% of women having earned the degree compared to 39.56% of men across all years. This difference is not statistically significant, however, suggesting superintendents have similar levels of education preparation.

Women and men superintendents are also similar regarding their professional experience as educators (see Figure 2; Table 2). The state provides total years of experience as an educator, years of experience within the state, and years of experience within the leader’s current district. Women tend to have slightly more experience in each category, though none are statistically significantly different. Superintendents in New Jersey, on average, have just under 20 years of experience as educators, and the vast majority of that experience comes from working within the state. These leaders hold, on average, about 10 years of experience within their current district. We cannot speak to possible differences in the specific roles prospective superintendents in New Jersey may have held (e.g., teacher, principal, curriculum director); however, these patterns in experience point to similar patterns found regarding differences in career pathways to the principalship (Fuller et al., 2016; Bailes and Guthery, 2020). These studies suggest women are less likely to advance to the principalship given completion of a preparation program (Fuller et al., 2016) and women in the assistant principalship often take longer to reach to the principalship as compared to their male counterparts (Bailes and Guthery, 2020).

These two characterizations of superintendent qualifications suggest women are equivalently qualified with men, and perhaps even slightly more qualified in terms of doctoral degree attainment and years of experience. We consider these findings to be a suggestion of a moderate glass escalator; given a potentially large pool of qualified women educators as suggested by their representation in teaching and the principalship, men dominate the superintendency.

RQ3: evidence of a glass cliff

Men and women superintendents serve similar districts in many ways; however, where district demographics differ, women tend to serve communities including larger numbers of economically disadvantaged and minoritized students. Additionally, women tend to have lower compensation, which is particularly true for new hires. We begin by describing district achievement in math and ELA, and we then examine differences between the proportions of several student subgroups that have been identified by federal and state policy for additional targeted supports; we here consider the proportions of these student groups enrolled in districts to be indicative of diverse student needs which should suggest a level of precarity. We examine student race/ethnicity and the enrollment of racially minoritized students, as well as economically disadvantaged students as identified by eligibility for free or reduced-price school meals. We then examine other student groups eligible for supplemental support services, English learners (ELs) and students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). We also describe the contexts in which newly hired superintendents tend to work and consider how leader compensation may indicate position precarity.

Average student achievement does not vary much by superintendent gender overall. However, the analyses focused on superintendents in their first year in the district showed that newly hired women superintendents are serving districts that tend to have much lower rates of both math and ELA proficiency, on average (see Tables 2, 4). These statistics suggest men and women are working in similar districts overall regarding achievement, but newly hired women may be sorted into districts exhibiting greater academic need.

New Jersey school districts serve a wide range of students from diverse economic backgrounds. In fact, districts range from serving no students qualifying for FRPL to all students qualifying (see Table 1). Women superintendents tend to lead districts serving higher proportions of students who qualify for the federal free or reduced-price lunch program, an indicator of family income and overall district socioeconomic status. Overall, in districts led by women, around 31% of students are eligible compared to about 27.5% of students in districts led by men. This difference in participation is driven by unified districts, where about 37% of students in women-led districts and 32% of students in men-led districts qualify for the nutrition assistance program. Women also tend to lead lower-grade districts with more students qualifying for FRPL, with over 28% compared to 24% in districts led by men.

On average, about 4% of New Jersey students are classified as English learners (ELs) across all grade levels. Unified districts serve the highest proportion of ELs (5.3%), and lower-grade districts serve higher numbers than upper-grade, in alignment with national trends, as students tend to be reclassified as they gain proficiency. Women tend to lead districts with higher proportions of ELs, which is driven by unified districts. However, these differences are not significant, and men and women superintendents appear to be serving similar proportions of ELs.

Almost one in five students in New Jersey is legally required to be provided with appropriate educational supports based on an individualized educational plan (IEP), and it is somewhat more common in unified districts compared to separate lower/upper grade districts. Men and women leaders are similarly likely to work with students with IEPs, though men leading K8 districts serve a slightly higher proportion of students with IEPs, on average.

New Jersey is a racially diverse state. Approximately 60% of students in the state are white, about 20% are Latinx, 10% are Black, 8% are Asian, and about 3% of students identify differently. Similar to the variability in FRPL eligibility, districts vary greatly in the racial makeup of their students. Demographic data for white, Latinx, and Black student enrollments show that districts again range from virtually 0 to 100% for each group. On average, men and women superintendents work in similar districts when comparing these racial demographics (see Table 2). However, first-year women superintendents tend to work with larger proportions of non-white students than first-year men (see Table 3). In particular, men work in districts with about 10% higher white enrollments, whereas women work in districts with about 8% higher proportions of Hispanic/Latinx students.

In addition to these district student demographic characteristics, we also consider compensation as a feature of possible precarity, as a lack of parity in compensation could be an indicator of a more challenging position. On average, men in our sample are paid more than women. The mean salary among all superintendents in the state is about $157,600. However, the mean salary for men is just over $160,000, whereas the mean salary for women is about $154,000. This difference of over $6,000 is both statistically and practically significant for district leaders. The salary gap is even more apparent for new superintendent hires; first-year men in the superintendency are paid, on average, over $11,000 more than first-year women superintendents.

Discussion

Women play an important and growing role in K12 district leadership, and New Jersey superintendents are an example of how women are breaking gender barriers. Still, women hold fewer leadership positions than their overall representation in the education workforce participation rates would suggest, and when they do achieve those highest positions, they may find themselves in more precarious settings than their male colleagues. The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which evidence suggests the presence of a glass ceiling, glass escalator, and glass cliff in the superintendency in New Jersey school districts.

While women hold more of these executive positions within New Jersey than is typical across the country, they are still underrepresented compared to their participation in the education labor force overall, suggesting a glass ceiling. This imbalance in promotion is seen despite women being just as qualified as men as defined by educational attainment and professional experience, suggesting a glass escalator. And finally, when women are hired into the superintendency, they tend to serve districts characterized as more challenging based on diversity of student need, suggesting a glass cliff.

Despite these findings suggesting these phenomena are at play in the career trajectories of educators in New Jersey, the greater representation of women in the superintendency in the state also suggests there might be lessons regarding professional leadership opportunities for women and hints at policies that could be enacted to help increase gender parity. We here present our discussion of important considerations for further research as well as policy and practical implications aligned with the research question themes of representation, promotion, and position precarity.

Representation: breaking the glass

Whether compared to the proportion of women in the United States, the proportion of women in the workforce, or the proportion of women educators more specifically, the representation of women in the superintendency is lacking, though less so in New Jersey. The evidence from our analyses suggests that though women are able to reach the superintendency, the rates of women in the superintendency lag behind their proportions in the general population and lag woefully behind their proportions among educators. This persistent underrepresentation of women in the superintendency points to potential concerns for equity in access to seats of power and potential biases in hiring to the superintendency that may mean school districts are not selecting the best possible leaders, as leaders are not chosen based solely on their qualifications for the position. A recent simulation study finds that relatively small gender biases in hiring may lead to relatively large levels of gender discrimination and productivity loss (Hardy et al., 2022). This may be especially the case in unified school districts where we see men leading districts at far higher rates to women.

Although women are underrepresented in the superintendency in the state, New Jersey does have more women in the superintendency as compared to many other states across the United States. One possible reason for a larger proportion of women leaders in New Jersey as compared to the country as a whole may be due to its relative geographic density and the larger number of school districts found within. With over 600 districts in such a small state in terms of square mileage, the state simply offers more leadership opportunities than most. States with fewer districts, by definition, have fewer executive leadership positions, as the vast majority of districts around the country have a single superintendent, and there are few districts consistently operating without a superintendent (though some superintendents lead multiple districts). Still, the structural existence of more positions does not necessarily lead to more women being hired.

The geographic density of school districts within the state may also play a role; because New Jersey is a school district dense state, districts are located in much closer proximity to each other than in many states, potentially presenting educators with more opportunities within a commutable distance as they consider job prospects. For comparison, neighboring states Pennsylvania and New York have about 10 and 40% more districts than New Jersey, respectively, while both are more than six times as large geographically; Texas, at over 35 times the square mileage of New Jersey, has close to twice as many districts (US Census Bureau, 2010; National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). Massachusetts, which is similar to New Jersey in square mileage, has about two thirds as many districts. In many states, open positions in other districts would typically necessitate a household move, whereas in New Jersey, educators likely live within a reasonable commute to multiple districts. These opportunities may afford more women the opportunity to apply to more leadership positions, which may at least partially explain why we see greater representation of women in the superintendency in the state. Further research comparing trends across states with consideration of district density could provide additional insight as to whether this factor affects women leaders’ career trajectories.

The various district configurations may also create more opportunities for women to assume superintendent positions. Again, more districts in general create more opportunities, and elementary districts create opportunities that might be more associated with women. The pattern of women leading elementary districts found in this study aligns with roles women hold in the principalship, with women more likely to be principals in elementary schools, and men more likely to be principals in high schools (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). Leadership positions in elementary schools and districts seem to be viewed as more suitable for women in both cases. Of course, this sorting is part of the problem – these districts are seen as gendered opportunities, so women are sorted into those positions, with men promoted to more prestigious positions. In a way, these elementary positions are thus a kind of precarious, because they are likely not to be taken as seriously and/or lead to promotion or higher compensation as high school or unified district positions. In this sense, the greater opportunity and possibility of this district structure to address the glass ceiling may also be leading to a type of glass cliff as well.

Still, educators’ ability to move between districts and apply to work in districts that align with their professional and student interests may directly impact the representation of women in the superintendency. Further research should examine these questions of mobility and district structure, though of course, not all states can adopt the New Jersey district structure, and states cannot easily change their geographic and population densities, nor do we suggest such. Nonetheless, an awareness of the importance of mobility and professional alignment in a position may be of use in structuring hiring processes and compensation packages, particularly given the evidence that women leaders are paid less than men.

Promotion: taking the stairs or riding the escalator?

Our findings align with existing research that suggests that women and men aspiring to leadership are equivalently qualified; therefore, those making hiring decisions must be intentional in creating an inclusive recruitment, hiring, and promotion process throughout the school and district leadership pipeline. School boards and hiring firms responsible for selecting new superintendents must be aware of their role in ensuring equal opportunities for all prospective leaders, and that the selection process is not only free from bias, but intentionally supportive of all candidates. For example, intentional consideration of work experiences that may be overlooked, such as elementary teaching and leadership roles, may bring more qualified women into consideration. Additionally, compensation packages could be structured to compensate for positions that might be considered more precarious.

Superintendents are typically hired via searches conducted by school boards, search firms, or some combination of the two (Tallerico, 2000; Kamler, 2009). While bringing in the outsider perspective of an external search firm may bolster efforts towards equitable hiring practices, these selections must happen intentionally, and school boards must be explicit about seeking a diverse pool of qualified applicants (Tallerico, 2000; Mahitivanichcha and Rorrer, 2006). Potential leaders with a range of different types of relevant experience should be sought out for inclusion in the applicant pool for review. Efforts should be made to ensure those making hiring decisions are appropriately trained to do so equitably, including anti-bias training. Awareness is important, and more research could help identify what approaches are most successful in ensuring all candidates are fully considered and are encouraged to apply.

While additional training and education may be of use, more research would also prove beneficial for understanding the decision-making processes of all stakeholders. Research examining the motivations of the various actors could help elucidate the factors affecting women’s promotion to the superintendency and the types of districts they serve.

Future research may explore how school boards and hiring firms evaluate and assess candidates for the superintendency and if their evaluations align to gendered expectations of school and district leadership. Additionally, research may examine what experiences and qualifications those making superintendent hiring decisions are likely to prioritize. This research could identify characteristics that are prioritized that may also be related to a candidate’s gender and point to potential areas and issues that, if resolved, could improve the likelihood of more women being hired into the superintendency. Lastly, future may want to explore the effects of instituting a “Rooney Rule” as is in place for National Football League (NFL) coaching positions. Despite NFL players being majority non-white, historically most coaches are white, particularly head coaches, a trend that continues. Therefore, the Rooney Rule was instituted, requiring teams to interview at least one prospective coach of color when hiring in an effort to diversify the profession (Coyne, 2020). Results of the requirement in the NFL have been limited, but it may be that policy changes that ensure women are among the finalists for a superintendency position could create greater access for women into those positions. While we do not anticipate any of these possible avenues for research to be a silver bullet, they may provide opportunities for further refinement of what is needed for greater gender parity in the superintendency.

Additionally, future research should also explore what factors potential superintendent candidates consider when applying for and accepting positions. Similar research on the principalship has found that factors like the stress associated with the job and the challenges associated with leading a school are important considerations when aspiring leaders are deciding between principal positions (Chen et al., 2000; Chan et al., 2003). Research on the principalship also finds that tapping by mentors may be an especially important contributor in educators aspiring to leadership, and this may be especially true for minoritized educators (Myung et al., 2011). It may be that women may also benefit from tapping for the superintendency.

Position precarity: standing on the edge of the cliff

Our results suggest, in alignment with previous research, that women leaders tend to work in more precarious positions (Smith, 2015; White, 2023). In New Jersey, women in the superintendency are more likely to lead in districts with higher proportions of students qualifying for free and reduced priced lunch, not attaining proficiency in Math and English, and identifying as Latinx. Though we do not believe these characteristics of a student population are a sign of precarity in and of themselves, these characteristics are often associated with higher levels of scrutiny and severe accountability consequences such as state takeover. While we do not think women should be discouraged from leading districts with higher proportions of students needing more intensive supports, our findings suggest women are more likely to lead more precarious districts, and districts and states should consider how to support and compensate leaders in these positions.

Specifically, states should consider whether more funding could be provided for precarious districts. The intensive supports that students who have been marginalized need to succeed academically may be too much to overcome given current funding equalization mechanisms like minimum funding programs based on local property taxes. Giving superintendents block grants above and beyond minimum funding equalization efforts could help school leaders meet the needs of districts that are prone to challenges and superintendent turnover. Districts might also consider compensating school leaders directly with additional funding and recognition. Some studies of superintendents suggest that district size and prestige are important considerations for retaining superintendents (Tallerico, 2000). Women may be more likely to be retained if they are given opportunities to lead some of the larger and more prestigious districts in a state.

In addition to these suggestions for policy, we recommend future research explore the factors that might contribute to the recruitment and retention of women in the superintendency. First, research should explore additional nuances regarding what makes a position precarious for educational leaders. In addition to demographics, other conceptualizations of precarity may be appropriate for analysis in New Jersey and in other settings. It may be that crises in a position or the frequency of crises in a district make a position more precarious. Moreover, informal reputations of school districts or local school boards, or perceptions of school quality, might also be considered in unpacking the complexities around what makes a school district precarious for (prospective) superintendents. In New Jersey, future research may consider how state takeover of districts and being an historical Abbott district might make a superintendency more precarious. The Abbott v. Burke (1985) lawsuit aimed at ensuring appropriate funding for low-income and minoritized children in New Jersey (Education Law Center, n.d.). Multiple legal proceedings over several decades led to very public labels of “Abbott” districts designated by low academic achievement and high enrollments of minoritized students, which community members may continue to associate with more precarious positions even 40 years later. Research might also explore what supports are more likely to contribute to the success and retention of women superintendents, and especially those working in precarious districts. Does additional funding or compensation make it more likely for women to succeed? Do training and mentoring help women to succeed in the superintendency? These are some of the questions future research should continue to explore.

Lastly, a logical next question is about the potential consequences women leaders in precarious positions may face. Women leaders may be more likely to leave the superintendency or be terminated given the precarity of their superintendencies. Future research should investigate whether the greater likelihood of women to lead in more challenging districts does result in higher likelihoods of turnover. Evidence from the principalship suggests leaders may be more likely to turnover when working in more precarious settings (McGhee and Nelson, 2005; Mitani, 2018; Grissom and Bartanen, 2019); however, less is known about the superintendency. It may be that women are extremely resilient and manage to keep long tenures in the superintendency despite the challenges posed by their district contexts, or it may be that women are more likely to burn out faster due to all the challenges of leading precarious districts. Ryan and Haslam’s (2005) study did not necessarily investigate whether turnover followed the appointment of women to the boards of firms, but this would be an important next question to explore.

Across all considerations for research, policy, and practice, a broader, more intersectional lens would be valuable. While we were unable to examine the intersectionality of gender and race/ethnicity in this study due to data limitations, the structures that privilege men in education leadership clearly also privilege whiteness. Prospective women of color leaders must be supported, and research must investigate and highlight the factors these leaders identify as contributing to their success to ensure both their continued success and also clear pathways and supports for our next leaders. Additionally, this dichotomized approach to gender can be expanded to be more inclusive of gender nonconforming and non-binary leaders.

In order to improve gender parity in K12 education leadership, we must consider not only whether women are able to obtain the highest executive positions, but also what those positions look like when they are hired. If, in fact, there is a tendency to “think female – think crisis,” women may be more often hired into more challenging, more precarious positions. Our findings suggest more attention should be paid to the demands placed on our women leaders.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://rc.doe.state.nj.us/ and https://www.state.nj.us/opra/.

Author contributions

JT engaged in all facets of the study, including study design and conceptualization, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing. DW also engaged in study design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was completed with the support of a grant from the University Research Council from Seton Hall University.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Adel Arghand for his contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Bailes, L. P., and Guthery, S. (2020). Held down and held back: systematically delayed principal promotions by race and gender. AERA Open 6. 1–17. doi: 10.1177/2332858420929298

Björk, L. G., Glass, T. E., and Brunner, C. C. (2005). “Characteristics of American school superintendents” in The Contemporary Superintendent: Preparation, Practice, and Development. eds. L. G. Björk and T. J. Kowalski (Corwin Press), 19–44.

Bornat, M., Littvay, L., and Chiru, M. (2018). Women to the Rescue: Is there a Glass Cliff in Politics? Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/f911f08251d28fab110eedd4f4ab8353f509b139 (Accessed June 7, 2022).

Bowers, A. J., and White, B. R. (2014). Do principal preparation and teacher qualifications influence different types of school growth trajectories in Illinois?: a growth mixture model analysis. J. Educ. Adm. 52, 705–736. doi: 10.1108/JEA-12-2012-0134

Brady, D., Isaacs, K., Reeves, M., Burroway, R., and Reynolds, M., (2011). Sector, size, stability, and scandal: explaining the presence of female executives in Fortune 500 firms. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 26, 84–105. doi: 10.1108/17542411111109327

Chan, T. C., Webb, L., and Bowen, C. (2003). Are Assistant Principals Prepared for Principalship? How Do Assistant Principals Perceive? Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED481543 (Accessed October 9, 2018).

Chen, K.-L., Blendinger, J., and McGrath, V. (2000). Job Satisfaction among High School Assistant Principals. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED452603 (Accessed October 9, 2018).

Cook, A., and Glass, C. (2013). Glass cliffs and organizational saviors: barriers to minority Leadership in work organizations? Soc. Probl. 60, 168–187. doi: 10.1525/sp.2013.60.2.168

Coyne, V. (2020). The Rooney rule: is the NFL doing enough to increase minority head coaches? Sports Law. J. 27, 205–224.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2004). The color line in American education: race, resources, and student achievement. Du Bois Rev. 1, 213–246. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X0404202X

Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). Race, inequality and educational accountability: the irony of ‘no child left behind.’. Race Ethn. Educ. 10, 245–260. doi: 10.1080/13613320701503207

Davis, B. W., Gooden, M. A., and Bowers, A. J. (2017). Pathways to the Principalship: An event history analysis of the careers of teachers with principal certification. Am. Educ. Res. J. 54, 207–240. doi: 10.3102/0002831216687530

Dee, T. S. (2005). A teacher like me: does race, ethnicity, or gender matter? Am. Econ. Rev. 95, 158–165.

Education Law Center. (n.d.) The History of Abbott v. Burke. Available at: https://edlawcenter.org/litigation/abbott-v-burke/abbott-history.html. (Accessed August 04, 2023).

Finnan, L., and McCord, R. (2017). 2016 AASA Superintendent Salary & Benefits Study: Non-Member Version. American Association of School Administrators.

Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., and An, B. P. (2016). The impact of personal and program characteristics on the placement of school Leadership preparation program graduates in school leader positions. Educ. Adm. Q. 52, 643–674. doi: 10.1177/0013161X16656039

Garn, G., and Brown, C. (2008). Women and the superintendency: perceptions of gender bias. Women and the superintendency: perceptions of gender bias. 62.

Glass, T. E., and Franceschini, L. A. (2007). “The state of the American school superintendency: a mid-decade study” in Rowman & Littlefield Education (Rowman & Littlefield Education).

Government Accountability Office. (2022). Women in Management: Women Remain Underrepresented in Management Positions and Continue to Earn Less Than Male Managers. (GAO Publication No. 22-105796). U.S. Government Printing Office. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105796.pdf. (Accessed May 31, 2023)

Grissom, J. A., and Bartanen, B. (2019). Principal effectiveness and principal turnover. Educ. Financ. Policy 14, 355–382. doi: 10.1162/edfp_a_00256

Grissom, J. A., and Keiser, L. R. (2011). A supervisor like me: race, representation, and the satisfaction and turnover decisions of public sector employees: race, representation, and the satisfaction and turnover decisions of public sector employees. J. Policy Anal. Manage. 30, 557–580. doi: 10.1002/pam.20579

Grissom, J. A., Timmer, J. D., Nelson, J. L., and Blissett, R. S. L. (2021). Unequal pay for equal work? Unpacking the gender gap in principal compensation. Econ. Educ. Rev. 82:102114. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102114

Grissom, J. A., Woo, D. S., and Bartanen, B. (2020). Ready to Lead on Day One: Predicting Novice Principal Effectiveness with Information Available at Time of Hire. In Annenberg Institute at Brown University. Available at: https://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai20-276 (Accessed February 23, 2023).

Grogan, M., and Shakeshaft, C. (2013). “A new way” in The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership. ed. M. Grogan. 3rd ed (John Wiley & Sons), 111–128.

Judge, B. E. (2003). Women on Board: Help or Hindrance? The Times. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/women-on-board-help-or-hindrance-2c6fnqf6fng

Hardy, J. H., Tey, K. S., Cyrus-Lai, W., Martell, R. F., Olstad, A., and Uhlmann, E. L., (2022). Bias in context: small biases in hiring evaluations have big consequences. J. Manag. 48, 657–69. doi: 10.1177/0149206320982654

Kamler, E. (2009). Decade of difference (1995—2005): An examination of the superintendent search consultants’ process on Long Island. Educ. Adm. Q. 45, 115–144. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08327547

Kulich, C., Ryan, M. K., and Haslam, S. A. (2007). Where is the romance for women leaders? The effects of gender on Leadership attributions and performance-based pay. Appl. Psychol. 56, 582–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00305.x

Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: understanding achievement in U.S. Schools. Educ. Res. 35, 3–12. doi: 10.3102/0013189X035007003

Mahitivanichcha, K., and Rorrer, A. K. (2006). Women’s choices within market constraints: re-visioning access to and participation in the Superintendency. Educ. Adm. Q. 42, 483–517. doi: 10.1177/0013161X06289962

McGhee, M. W., and Nelson, S. W. (2005). Sacrificing leaders, villainizing leadership: how educational accountability policies impair school leadership. Phi Delta Kappan 86, 367–372. doi: 10.1177/003172170508600507

Mitani, H. (2018). Principals’ working conditions, job stress, and turnover behaviors under NCLB accountability pressure. Educ. Adm. Q. 54, 822–862. doi: 10.1177/0013161X18785874

Morrison, A. M., White, R. P., White, R. P., Velsor, E. V., and Leadership, C. F. C. (1987). Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Can Women Reach The Top of America’s Largestcorporations? Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Muther, C. (2022). Meet the Gloucester native who shattered the cruise industry’s glass ceiling—The Boston Globe. BostonGlobe.Com. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/12/08/lifestyle/meet-gloucester-native-who-shattered-cruise-industrys-glass-ceiling/ (Accessed December 8, 2022).

Myung, J., Loeb, S., and Horng, E. (2011). Tapping the principal pipeline. Educ. Adm. Q. 33, 152–159. doi: 10.1177/0013161X11406112

National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Selected Statistics From the Public Elementary and Secondary Education Universe: School Year 2015-16. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018052/index.asp. (Accessed June 6, 2023)

National Center for Education Statistics (2022). Characteristics of Public School Principals (Condition of Education). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.

Noguera, P. A. (2008). Creating schools where race does not predict achievement: the role and significance of race in the racial achievement gap. J. Negro Educ. 77, 90–103.

Ringel, J., Gates, S., Chung, C., Brown, A., and Ghosh-Dastidar, B. (2004). Career Paths of School Administrators in Illinois: Insights From an Analysis of State Data. RAND Corporation.

Robinson, K., Shakeshaft, C., Grogan, M., and Newcomb, W. S. (2017). Necessary but not sufficient: the continuing inequality between men and women in educational leadership, findings from the American Association of School Administrators mid-Decade Survey. Front. Educ. 2:12. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00012

Ryan, M. K., and Haslam, S. A. (2005). The Glass cliff: evidence that women are over-represented in precarious Leadership positions. Br. J. Manag. 16, 81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00433.x

Ryan, M. K., and Haslam, S. A. (2007). The Glass cliff: exploring the dynamics surrounding the appointment of women to precarious Leadership positions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32, 549–572. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.24351856

Ryan, M. K., Haslam, S. A., Hersby, M. D., and Bongiorno, R., (2011). Think crisis–think female: the glass cliff and contextual variation in the think manager–think male stereotype. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 470–484. doi: 10.1037/a0022133

Ryan, M. K., Haslam, S. A., Morgenroth, T., Rink, F., Stoker, J., and Peters, K. (2016). Getting on top of the glass cliff: reviewing a decade of evidence, explanations, and impact. Leadersh. Q. 27, 446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.10.008

Salamy, E. (2022). Shattered glass sculpture of VP Harris at MLK library. FOX 5 DC. Available at: https://www.fox5dc.com/news/shattered-glass-sculpture-of-vp-harris-at-mlk-library (Accessed October 18, 2022).

Schein, V. E. (2001). A global look at psychological barriers to Women’s Progress in management. J. Soc. Issues 57, 675–688. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00235

Smith, A. E. (2015). On the edge of a glass cliff: women in leadership in public organizations. Public Adm. Q. 39, 484–517.

Taie, S., and Goldring, R. (2020). Characteristics of Public and Private Elementary and Secondary School Teachers in the United States: Results from the 2017–18 National Teacher and Principal Survey (NCES 2020–142) U.S. Department of Education.

Tallerico, M. (2000). Gaining access to the Superintendency: headhunting, gender, and color. Educ. Adm. Q. 36, 18–43. doi: 10.1177/00131610021968886

Thomas, T., Tienken, C. H., Kang, L., Bennett, N., Cronin, S., and Torrento, J. (2023). 2022–2023 AASA Superintendent Salary & Benefits Study. American Association of School Administrators.

Tienken, C. H. (Ed.) (2021). The American Superintendent 2020 Decennial Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Available at: https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781475858471/The-American-Superintendent-2020-Decennial-Study

United States Government Accountability Office. (2010). Women in Management: Female Managers’ Representation, Characteristics, and Pay, 111th Congress. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-10-1064t.pdf (Accessed May 31, 2023).

US Census Bureau (2010). State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/2010/geo/state-area.html. (Accessed June 06, 2023)

Warner, J., Ellmann, N., and Boesch, D. (2018). The Women’s Leadership Gap Center for American Progress. Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/womens-leadership-gap-2/ (Accessed November 20, 2018).

Wattles, J. (2023). Remembering Sally Ride—40 years after she shattered the glass ceiling on the way to space. CNN. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/18/world/sally-ride-nasa-anniversary-scn/index.html#:~:text=It%20has%20been%2040%20years,space%20shuttle%20Challenger%20in%201983 (Accessed June 18, 2023).

White, R. S. (2021). What’s in a first name?: America’s K-12 public school district superintendent gender gap. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 22, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2021.1965169

White, R. S. (2023). Ceilings made of glass and leaving En masse? Examining superintendent gender gaps and turnover over time across the United States. Educ. Res. 52, 272–285. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231163139

Williams, C. L. (1992). The Glass escalator: hidden advantages for men in the “female” professions*. Soc. Probl. 39, 253–267. doi: 10.2307/3096961

Keywords: superintendents, glass cliffs, women, gender, district leadership, K12 leadership, administration

Citation: Timmer JD and Woo DS (2023) Precarious positions: glass ceilings, glass escalators, and glass cliffs in the superintendency. Front. Educ. 8:1199756. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1199756

Edited by:

Emiola Oyefuga, Virginia Commonwealth University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lauren P. Bailes, University of Delaware, United StatesWendi Moss, Collegiate School, United States

Copyright © 2023 Timmer and Woo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer D. Timmer, jennifer.timmer@shu.edu

Jennifer D. Timmer

Jennifer D. Timmer David S. Woo

David S. Woo