Effectiveness of educational interventions in minimizing reactance in traffic accident prevention

- Department of Didactics of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Institute for Physics Didactics, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

Introduction: Classical mechanics concepts are vital for understanding traffic safety, encompassing speed, acceleration, stopping distance, impact speed, deformation, kinetic energy, and their effects on vehicle occupants. Statistical physics principles are also employed to study multiple vehicles as a many-particle system. This study examines the effectiveness of using a damaged car and structured instruction in road safety initiatives.

Methods: Participants engaged with a damaged car and discussed deformation caused by excessive speed. They participated in role simulations, envisioning and solving risky traffic scenarios, while considering the potential boomerang effect resulting from excessive fear appeals within the campaign.

Results: Combining emotional appeals with solution-focused, action-oriented, and self-esteem-enhancing interventions is essential to mitigate the boomerang effect and encourage safety-compliant behavior. Educational institutions must implement tailored follow-ups to emotionally charged prevention campaigns. Using Design-Based Research, we developed effective methods for knowledge acquisition and transfer, drawing from cognitive behavioral therapy and established traffic safety programs.

Discussion: This publication explores non-standardized social training within focus groups, focusing on negative emotional states following an emotionalizing campaign similar to “Crash Kurs NRW,” targeting upper-level courses in North Rhine-Westphalian schools. Methods from cognitive behavioral therapy and social learning initiated, observed, and documented changes in participants’ norms, values, and attitudes, discussed herein. Additionally, we investigated whether the presence of police officers in prevention campaigns influences reactive behavior. Comparing pre- and post-surveys confirmed reactance after emotionalizing campaigns, and our structured post-survey effectively influenced stage-event-induced behavior. Surprisingly, police officers’ presence did not significantly impact reactive behavior. Furthermore, our follow-up tool extends its applicability to similar emotionalizing prevention campaigns, broadening its potential reach. Our future research will delve into students’ physics literacy during traffic space analysis of accident hotspots, advancing traffic safety initiatives.

1 Introduction

The question of the greatest possible potential for learning, the imparting of knowledge, and a concomitant change in behavior is an omnipresent phenomenon in our educational society (Petermann and Petermann, 2018, p. 12). The aim is to achieve a high level of fit between the parental home, educational and upbringing institutions, and leisure peer group. In this context, the level of school-based traffic and mobility education plays a prominent role because of the high accessibility of the target group as a result of compulsory schooling (Klimmt et al., 2015, p. 16). Therefore, we use an interdisciplinary approach in our constant search of implementable practices in teaching, which can impart knowledge more efficiently and sustainably and use human comprehension to its full extent. In particular, the implementation of behavioral change, as an observable criterion of learning success, is of special importance in educational and preventive work. This also applies to the area of traffic accident prevention, which, according to the decree, includes traffic safety work in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) as a necessary component in addition to repressive and public relations work (Road safety work of the police,1 March 17, 2023). In Germany, traffic education and traffic information are located at different levels of society and are characterized by interdisciplinary cooperation and diversity.

The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of the Interior have set a joint course for safety in this area by making traffic accident education and prevention the focus of curricular provisions, for which teachers can enlist the support of police departments or traffic guards.

According to the “Adjusted Official Collection of School Regulations” (BASS) in North Rhine-Westphalia, traffic education and mobility education in schools as part of their teaching and educational mission is appropriate for all grades and types of school (BASS, Road safety education and mobility education at school,2 March 17, 2023). In this context, traffic education and mobility education, if not anchored in the curricula, is understood as a cross-sectional task of all subject areas, and may be implemented in different forms, including projects.

This provision provides a variety of options for teaching traffic safety aspects and safety-conscious behavior in addition to curricular instruction.

Since mobility experiences are made in all areas of life and at all age levels, it should be adopted at all age levels in an age-appropriate and adequate manner while ensuring that beneficial messages are strongly reinforced.

The curriculum for physics instruction at the upper secondary level declares the competency expectations and content priorities for students until the end of the introductory phase (School development and curricula,3 March 17, 2023).

Road safety training programs are also a common means of raising awareness of risky attitudes and behaviors. While road safety courses for children are regularly evaluated, there is generally a lack of comparable evaluation for young people and adults. A recent systematic review aimed to identify studies that evaluate the effectiveness of road safety training programs in this age group. This review followed the PRISMA methodology to identify relevant articles using predefined research criteria. A total of 1,336 indexed articles were searched, and finally 22 articles directly addressing the topic were selected (Faus et al., 2023).

The search strategies spanned various databases such as WOS, Scopus, NCBI, Google Scholar and APA. The selected articles suggest that the effects of traffic safety training programs in adults are generally classified as mild to moderate. However, the effectiveness of these programs is significantly enhanced when they aim to improve risk perception and decision making rather than focusing solely on driving skills. In any case, the review highlights the need for further evaluation of such courses to identify which tools are actually effective and which should be replaced by new behavior change methods in the design of future driver education programs.

This research study presents an innovative pilot campaign for a little-researched target group of young adults, in which an accident car was used as a visual element to illustrate the reality and potential consequences of risky driving behavior. This campaign is part of the Crash Kurs NRW campaign, which has been continuously implemented in schools for the defined target group since 2010. The evaluation of the effectiveness of the original intervention by Hackenfort et al. (2015) showed a resulting reactance with insufficient follow-up, as described in Section 2.2.

An accident car can also serve as an illustrative example in science lessons to explain physical principles in the context of road accidents, such as kinematic variables in a collision. By analyzing the traces of the accident and damage, pupils can gain an insight into the forces and energies at work in a traffic accident. This enables a practical application of scientific concepts in the context of road safety.

Road traffic processes can therefore be used to achieve a higher level of education by analyzing, evaluating and interpreting the results, both in terms of acquiring technical skills and in the context of gaining knowledge.

When implementing a scientific link with a preventive traffic accident campaign, not only are the contents of core curricula fulfilled, but the behavior-oriented goals of traffic accident prevention campaigns are also achieved.

This paper will present such a concept.

2 Theory

2.1 General framework

Mobility, and by association participation in the social environment, is an increasingly complex and demanding process, which in many areas requires a deeper awareness of the processes involved and a sensitization to one’s own possibilities of exerting a positive influence.

Road safety consulting is intended to provide early and long-term work based on the principle of lifelong learning. These measures are coordinated with each other in the age groups and their content is tailored to the target group. Road users are to discover cooperative behavior as positive and be strengthened in their personal and joint responsibility. Road safety advice is intended to inform road users and their multipliers, e.g., parents, educators, associations and other bodies for their road safety work, about developments and findings relevant to road safety as well as roadworthy behavior (Polizeidienstvorschrift PDV 100, Polizeifachhandbuch NRW, 2021).

An improvement in traffic safety can only be achieved if

• the traffic awareness of the individual road user

• their inner attitude to the whole traffic process

• their attitude towards other road users and

• their attitude to the traffic rules is undergoes positive change.

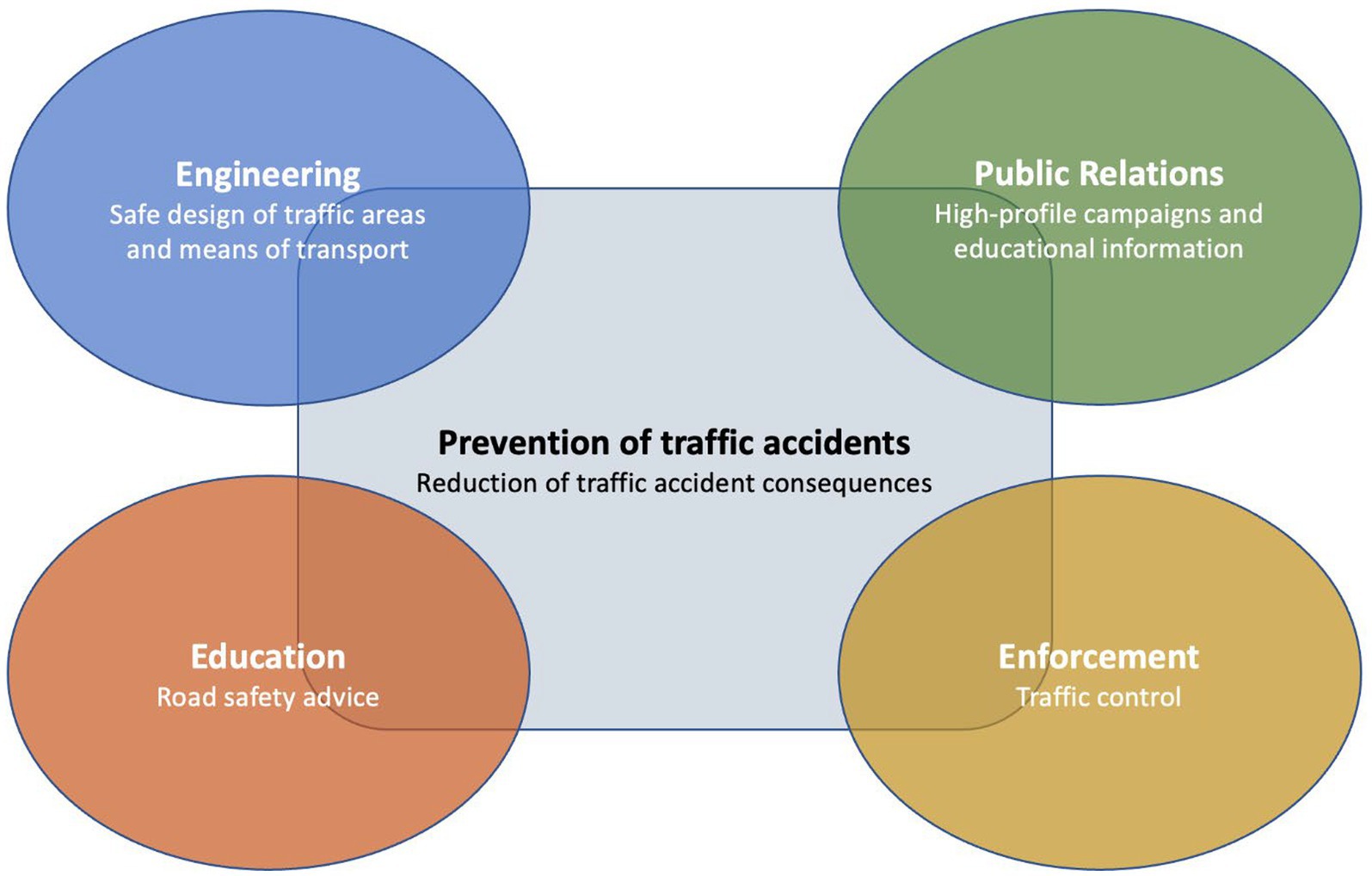

Traffic accident prevention takes place at the following levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the impact levels of traffic accident prevention (source: own representation).

Teaching and education in particular are intended to address and raise awareness among the target group of young drivers, who occupy a special position due to their developmental specificity. According to a study by the Allianz Center for Technology, globally, more young people between the ages of 15 and 29 die in traffic accidents than from illness, drugs, suicide, violence or war events. Overall, that amounts to about 400,000 per year (March 17, 2023).4 Three main constructs may be cited as reasons:

• teen drivers overestimate themselves and their abilities

• young people consider themselves invulnerable (Linneweber, 2003, p. 291)

• the phenomenon of conscious risk-connotative behavior (Raithel, 2013, p. 31)

While the general risk of being young is a normative behavior inherent in the life phase, the beginner’s risk is independent of age and relates to the basic skills of driving technique. These include, for example, mastery of vehicle technology or the ability to adequately assess constantly changing traffic situations (Bastian, 2010, p. 87).

Deliberately risk-connotative behavior includes actions such as subway surfing, risky dares, or influencing traffic in a dangerous manner. In this instance, the risk may relate either to one’s own integrity (illegal street racing) or to that of others, e.g., opening sewers or throwing stones or manhole covers at moving vehicles (Raithel, 2013, p. 31).

In all activities, a high degree of criminal energy may be assumed as well as the conscious acceptance that damages may occur [BGH judgment in the stone-throwing case of January 14, 2010 (4 StR 450/09)].

Against the background of these findings, it is necessary to detect and reach particularly those young road users who are prone to be involved in traffic accidents due to their deliberately risky behavior by means of multiple measures of intervention in the sector of traffic accident prevention.

For road safety work, this emphasizes the necessity to approach young drivers directly: in schools and educational institutions, in the context of work and family, in the peer group.

The success of interventions depends on the following parameters:

• age- and development-appropriate communication of traffic-related messages

• visiting the target group in their living environment (settings)

• targeted thematic addressing, as it is more effective compared to generalized campaigns

• continuity of interventions depending on the developmental transition phases (from child to adolescent, from adolescent to adult)

Particularly in the transitional phases of development, people are highly receptive to information that explains the necessity of reflecting one’s own behavior and that yields an increase in coping skills (Schneider, 2017, p. 31).

These aspects must be considered and implemented in the teaching of traffic accident prevention in order to generate a reliable indicator for the highest possible success.

2.2 Reactance behavior

A traffic accident prevention concept called Crash Kurs NRW was developed and launched by the NRW police with precisely this objective in mind.

The state campaign Crash Kurs NRW is a preventative initiative in North Rhine-Westphalia that aims to raise awareness of road safety. Through the targeted use of experience-oriented methods, such as the staging of accident situations, young people in particular are to be made aware of the consequences of risky driving behavior. The campaign integrates various stakeholders, including schools, police stations and traffic wardens, in order to achieve a broad and sustainable impact in the area of road accident prevention.

Showing accident images in the context of reactance has a double-edged effect. On the one hand, drastic images can trigger an emotional response and raise awareness of the dangers of road traffic. On the other hand, there is a risk that people will react to such images with defense mechanisms, especially if they feel patronized or restricted in their freedom. Therefore, a balanced approach is needed when using accident images that promotes awareness without provoking reactance.

A recent study by Dr. Elizabeth Box, which analyzed “shock and tell” approaches to road safety education, suggested that such tactics, which rely on evoking emotional responses through dramatic images, have limited effectiveness and can provoke defensive or even hostile reactions, particularly among young men. The research emphasized the need for an interactive approach in which facts about road safety are shared and young participants are encouraged to draw their own conclusions about safe driving behavior. These findings indicated that a traditional ‘shock and tell’ methodology may not be sufficient to achieve long-term impact (Box, 2023).

In a previous study that applied Kim Witte’s Extended Parallel Processing Model (EPPM) to analyze road safety commercials in Russia, it was found that threat messages outweighed efficacy messages in the commercials. This suggested that an overemphasis on danger without sufficient emphasis on coping messages can lead to increased reactance (Ngondo and Klyueva, 2019). The EPPM, as a theoretical framework in communication and health psychology, distinguishes appropriate fear from defensive reactions to threats and has been used to evaluate the effectiveness of road safety messages.

Combining these findings, it is emphasized that balanced road safety education should communicate both dangers and concrete coping strategies to minimize the development of reactance. This underscores the importance of evidence-based interventions and an interactive approach based on research and behavioral psychology to achieve sustainable impact in road safety education.

The impact of Crash Kurs NRW was investigated by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (by Hackenfort et al., 2015). The following criteria were collected for the impact study:

• subjective judgment of dangerousness

• self-competence assessment

• attitude to road safety

• safety-relevant knowledge and

• acceptance of the intervention (Gansewig and Walsh, 2020, p. 67)

The results demonstrated that a high level of acceptance of the event was still present months later. Hackenfort et al. again studied the Crash Kurs NRW campaign as part of the evaluation of a prevention measure for young novice drivers in Lower Saxony. The results showed that participation in the campaign had a positive effect on the driving behavior of participants and increased their willingness to avoid risky driving maneuvers (Hackenfort et al., 2018).

Additionally, it has been established that campaigns with so-called fear appeals, while initially generating widespread attention, also more easily lead to reactance and rejection of the desired change in behavior by the at-risk group. Reactance behavior refers to the tendency of individuals to react negatively to actions or restrictions that are perceived as limiting their freedom or autonomy. To minimize reactance behavior, it is important that traffic prevention measures be transparent, fair, and meaningful. Thus, police should communicate the measures well and explain why they are necessary. Evidence from research studies suggests that communication campaigns, related to traffic safety messages, may be rendered significantly more effective when accompanied by traffic education measures (Faus et al., 2021).

There are some studies that focus on the role of police officers in prevention campaigns and the associated reactance behavior of the public. Different studies show that the role of police officers in prevention campaigns is complex and depends on many factors. It is important that officers display a positive attitude during the campaign and that police presence is carefully balanced to minimize public reactance behavior and have a positive impact on behavior (Jeong and Lee, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.06.010).

For this reason, an instructional follow-up concept has already been developed in the context of the NRW state prevention campaign Crash Kurs NRW. The research results and derived requirements of Hackenfort et al. were taken up and developed in a research desideratum. This has subsequently been published at https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046403 (von Beesten and Bresges, 2022).

The core methods of the follow-up concept are methods from cognitive behavioral therapy and social training in focus groups, which are designed to teach skills and launch behavioral changes in sequential, multi-step procedures. The first steps are:

• dysfunctional assumptions are detected and re-evaluated (theory-based recognition)

• through self-awareness, existing misconceptions about risky traffic behavior are exposed as such (practical experience, evaluation, assessment)

• development of functional action strategies from the previously acquired knowledge through active practice in a role simulation and rehearse them for an emergency situation (practical transfer to everyday life, implement)

• the achievement of the goal should then be made measurable via evaluation

In this instance, the perception and recognition of risks and their evaluation are of central importance. The ability to recognize and avoid dangers from the environment is useful for all living beings to improve their chances of survival. The ability to preserve experiences with the environment and to learn from them increases these chances. Humans still have the chance to change their environment and can act actively and purposefully. Thus, they are able to not only create but also reduce risks (Jungermann and Slovic, 1993, p. 167).

Risk perception is divided into two main factors: perceived threat and perceived control. Perceived threat refers to the person’s assessment of the severity of the potential harm or loss associated with a particular risk. Perceived control, on the other hand, refers to the person’s feeling that he or she can control or influence the risk. Depending on the perceived controllability, the decision-making process takes place, which in turn dictates behavior (Raupp, 2012, p. 27).

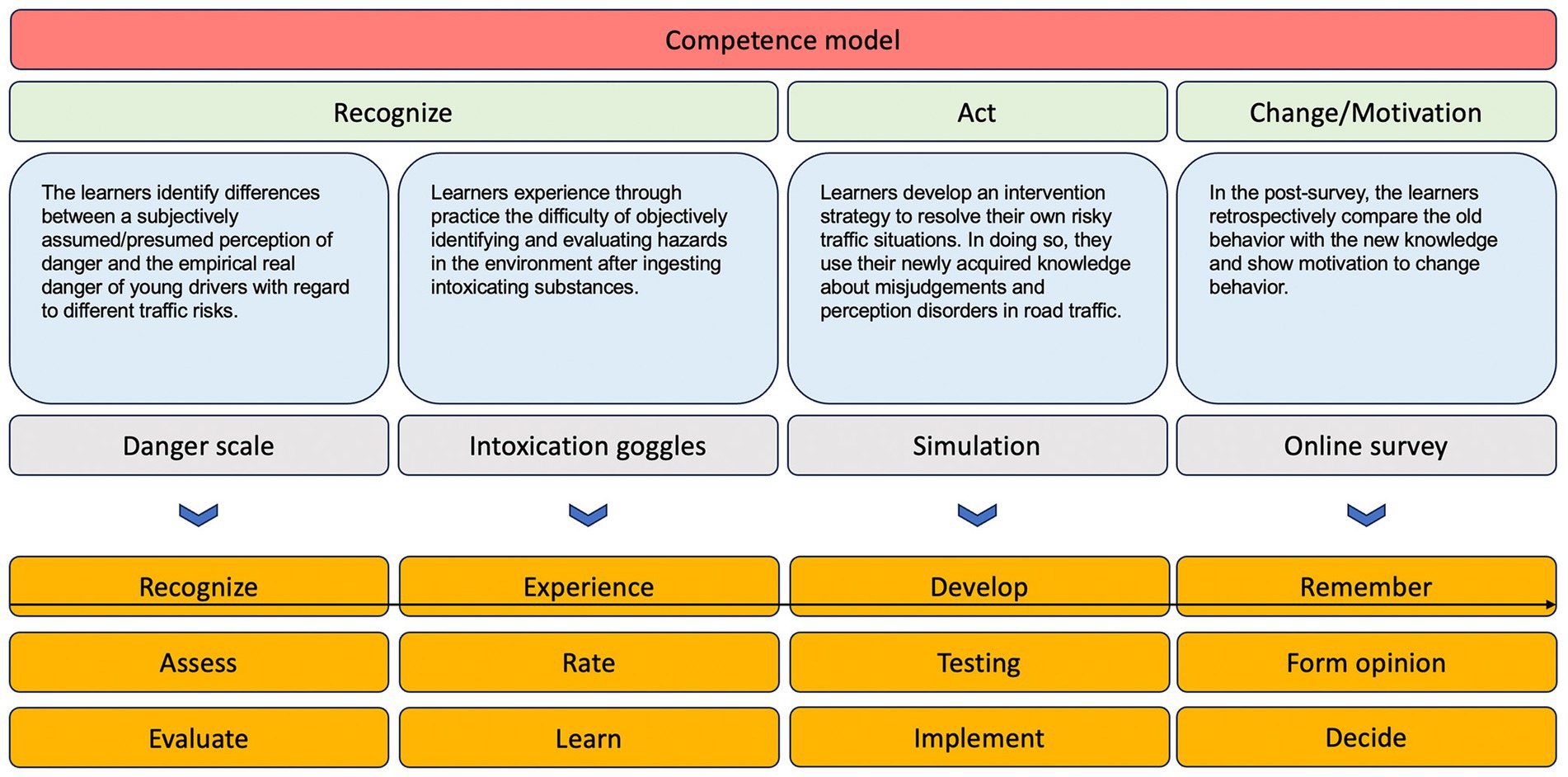

The following diagram illustrates the processes of recognizing, assessing and evaluating, of learning, transferring into action and thus into the behavior shown, as well as of its evaluation as empirical evidence of any sustainable internalization. In addition, the methods used will be assigned to the respective sections (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Competency model for content, recording and balancing individual learning outcomes via the applied follow-up tools (source: own representation).

At the vertical competence level, the various processes of follow-up aim at the following skills:

• recognition in the broader sense (related to hazards in general)

• action and

• change (motivation).

In the horizontal competence level, the processes of follow-up aim at

• recognition in the narrower sense (related to dangers in concrete situations)

• experience (sensorimotor experience)

• developing

• recall

In the overall cognitive performance, human behavior should be positively influenced by the interaction of the prevention campaign and follow-up concept in favor of own health and traffic safety and public health and traffic safety.

2.3 Use of an exhibit

In 2022, a police department of the NRW police developed another project, which is intended to have an emotionalizing effect comparable to the Crash Kurs NRW stage campaign. By exhibiting a car that was damaged in an accident, participants are given the opportunity to come into real contact with a traffic accident. Since the participants are able to touch or rather “grasp” the damaged car, a real object is used to create a deeper understanding of the physical impact forces and to emphasize how powerless people are in the “traffic accident” process. Looking at a damaged car may have different effects on the observer, which may be beneficial in the context of road safety. Some possible effects are listed below:

• Road safety awareness: Looking at a damaged car may remind people how dangerous it can be to be to be driving or riding in a vehicle. Including information about road safety and accident prevention in the display may increase people’s awareness of the risks on the road and help them drive more carefully and responsibly.

• Raising awareness of the consequences of accidents: Looking at a damaged car may also help people understand the impact of traffic accidents on those involved and their families. Thus, it may remind them of the importance of being careful on the road and obeying traffic rules.

• Interest in vehicle technology: A damaged car may furthermore arouse technical interest and encourage people to learn more about the safety features and technologies of modern vehicles. This can help get them interested in new technologies and developments in the automotive industry. This may subsequently lead them to be more likely to choose to purchase a vehicle with more supportive safety features.

• Emotional reactions: Looking at a damaged car might even evoke strong emotional reactions, especially if the occupants have been injured or killed. In some cases, this can also have negative effects (reactance), especially if visitors have had traumatic experiences with accidents.

Overall, the study indicates that accident exhibitions can be a useful tool for improving road safety if they are professionally designed and used in a targeted manner. In addition, it is shown that accident exhibitions can also play an important role in the cooperation between traffic authorities and other stakeholders, such as schools or road safety organizations. As a result, exhibitions about accidents may be designed to influence certain target groups more effectively (Tews and Krajewski, 2011).

The last two minutes before the crash are simulated with fictitious conversations of the vehicle occupants by playing audio files from the interior of the vehicle. Thus, participants are able to mentally put themselves in the same situation. Nevertheless, they are standing unharmed next to the exhibit and are still able to decide on looking after and maintaining their health. This crucial difference ought to be emphasized.

In addition, this study will investigate whether an emotionalizing concept comparable to Crash Kurs NRW elicits less reactance.

2.4 Theory-practice transfer of physics related topics on the basis of a damaged car

Theory-practice transfer in physics education refers to the ability of students to apply the theoretical concepts they have learned in class to practical applications and situations. This is an important part of the learning process as it allows students to deepen their understanding of the concepts and improve their skills in applying them (Habig et al., 2018, pp. 101–114).

There are several ways to promote theory-to-practice transfer in physics classes. One way is to have students perform hands-on experiments that illustrate the concepts covered in class.

Another way is to involve students in solving real-world physics problems. This can be accomplished through projects or activities that require students to apply their theoretical knowledge to solve real-world problems. This can help students apply concepts in a real-world context and improve their ability to transfer theoretical concepts to practical applications (Demuth, 2012).

An important aspect of road safety research is crash testing, during which vehicles collide under controlled conditions to study the effects of crashes on occupants and vehicles. These tests serve to understand the effects of collisions on the bodies and protection of occupants, as well as evaluate the structural integrity of vehicles.

Furthermore, the results of crash tests can be used to derive physical rules and laws. For example, the results of vehicle-barrier collision tests may advance our understanding of the laws of motion and the law of conservation of momentum. Analyzing the kinetic energy and forces acting on an occupant or vehicle in a collision enables us to recognize how energy is transferred in such a situation and how we can improve occupant protection.

However, it is important to note that crash tests are only part of the broader spectrum of methods that can be used to derive physical rules and laws. Similarly, other methods, such as observations, measurements, simulations, and theoretical considerations, may be used to improve our knowledge of physics and enhance safety on the roads (Automotive test facility,5 April 02, 2023).

In the present research work, the following research questions are pursued in accordance with the modified conceptualization of the Original Crash Kurs NRW:

Q1: Does the modified concept of exhibiting a damaged car generate less reactance than Crash Kurs NRW?

Q2: Does the presence of the police lead to a change in reactance?

Q3: Can the instructional follow-up concept be successful in terms of a targeted change in behavior?

Q4: Is exhibiting a damaged car suitable for teaching physics topics?

3 Methodology

3.1 General framework

The sample group was taken from a vocational college.

A detailed overview of the composition of the research group and the comparison group in terms of age, gender distribution and educational qualification can be found in Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

The participants were grouped as follows:

All participants were pursuing the goal of practical training in combination with a higher education qualification. In this particular case, it was an apprenticeship in the field of automotive mechanics. The vocational college is located in a large industrial city in a rural environment. Car accidents are a constant issue, as most young people have access to cars and use them for travel and meetings in the weekends.

At this vocational college, the state-wide traffic accident prevention campaign Crash Kurs NRW has been carried out regularly by the local police for several years. Thanks to the close cooperation between the school’s educational staff, the school management and the police’s road safety advisory service, it was possible to initiate the implementation of the modified educational concept with an accident car in an initial pilot event with a zero group there. The close thematic connection between the college’s subject area and road accident prevention means that the school has a constant need for prevention work.

The class was selected by the school management and the local police for a morning event at the school depending on the schedule. It had to be possible to access the nearby sports field without an audience and with privacy so that the trailer with the car involved in the accident could be set up there for the participants.

In answering the research questions, the differentiation from the original Crash Kurs NRW as well as a connection to science lessons should be clarified.

The student group was randomly split into two halves. The test group interacted with the police instructor, while the control group did not interact with the police instructor. This separation allowed the difference in reactance behavior between the group without police and the group with police to be empirically studied.

3.2 Exploration of knowledge acquisition with the help of the exhibit

3.2.1 The control group

The first half of the group was scheduled early in the morning. At that time, the police traffic safety advisory was not yet on site. Careful attention was paid in advance as part of the preparations to ensure that there were no clues to the exhibit or in the educational facility that would indicate that the police were associated with the campaign.

The group was introduced to the exhibit

• without explanatory preparation

• without the possibility to ask questions during viewing

• without recognizable/visible associated specialist personnel

It was only after listening to the audio files that the research creator raised questions about the preventability of such traffic accidents.

Then, Group 1 was led to the class room and the online survey questionnaire (pretest) was administered.

Afterwards, Group 1 was informed that they had participated in a police traffic accident prevention campaign.

3.2.2 The comparison group

The second half of the group was received and welcomed by the police in front of the school. They were reminded of the Crash Kurs NRW stage event they had attended together and interactively asked about the road safety messages from the event. The group was introduced to the topic. Thereafter, the police prepared the group for the accident car they were about to inspect. Some participants seemed to have already recognized the accident and also the occupants and their fate. Consequently, the first clarifying questions could be answered.

Afterwards, the group was introduced to the exhibit

• after adequate preparation

• with the constant accompaniment of the police as specialized personnel

• with the constant possibility to inquire about the circumstances of the accident, causes of the accident, vehicle technology and accident prevention

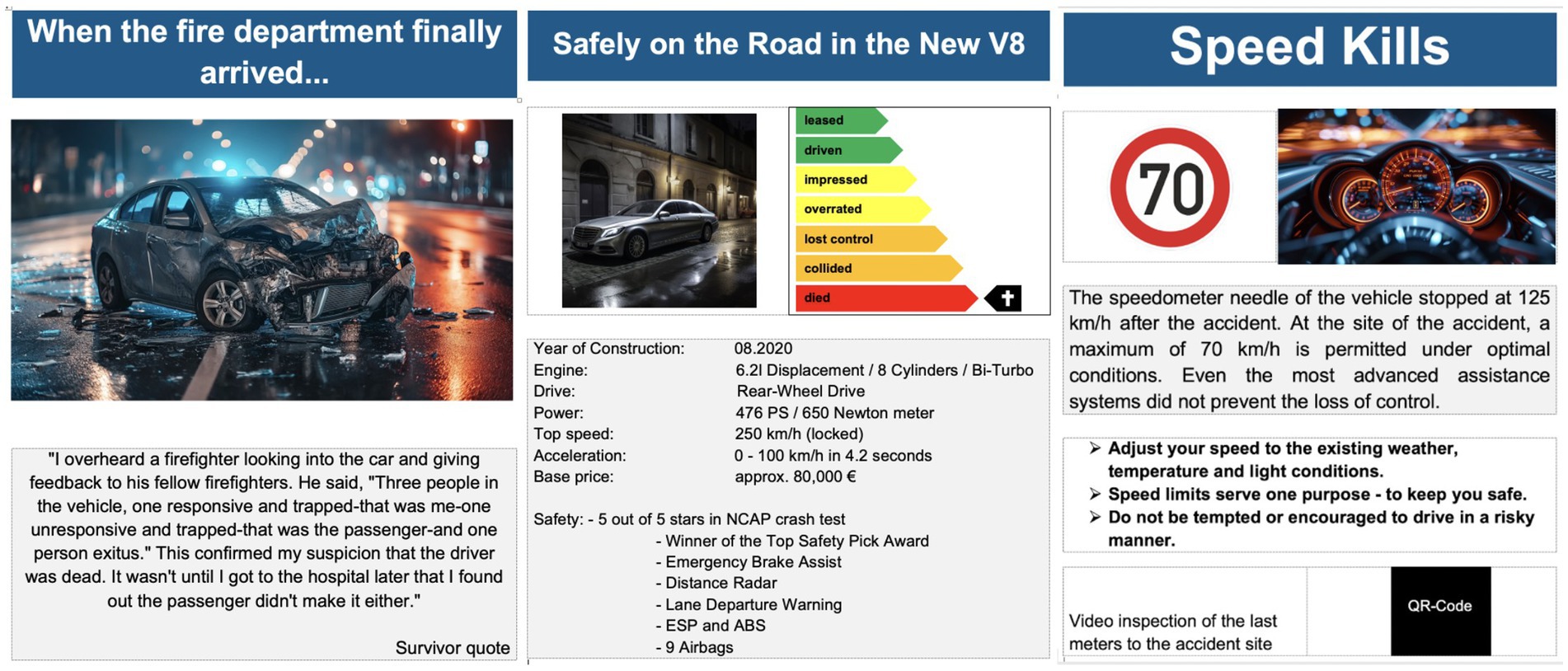

• with static information displays providing information

Three exemplary illustrations of the information displays are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Exemplary excerpts of the steel images (source: created by the authors with Midjourney AI).

The stele images show both targeted factual information, of physical and technical origin, aimed at avoiding traffic accidents as well as emotionalizing content that is intended to lead to a change in behavior at the relationship level. The additional possibility of addressing an auditory channel (audio files via QR codes) combined with the visual aspect ensures that the target group is more receptive to the information provided to them.

After playing the audio files, the question of the avoidability of such traffic accidents was raised again.

Following this, this group also conducted the online survey pretest in class.

The evaluation of the observations at the exhibit was carried out with the program MAXQDA®. The online survey of the pretest was conducted with the program LimeSurvey®.

The pretest was evaluated using the SPSS® program.

3.3 Exploring the acquisition of knowledge through classroom follow-up

The follow-up to the lessons was carried out in the entire class, again with the support of the police traffic safety advisors. This approach had the benefit of allowing for police-specific questions to be answered by the police themselves.

Since Group 1 did not have the opportunity to ask any questions about the accident at the exhibit the way Group 2 could, they were given the opportunity to do so.

After that, the instructional follow-up started with the following tools. The following Sections 3.3.1 to 3.3.3 have already been published as research desiderata in: Frontiers, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046403 (von Beesten and Bresges, 2022).

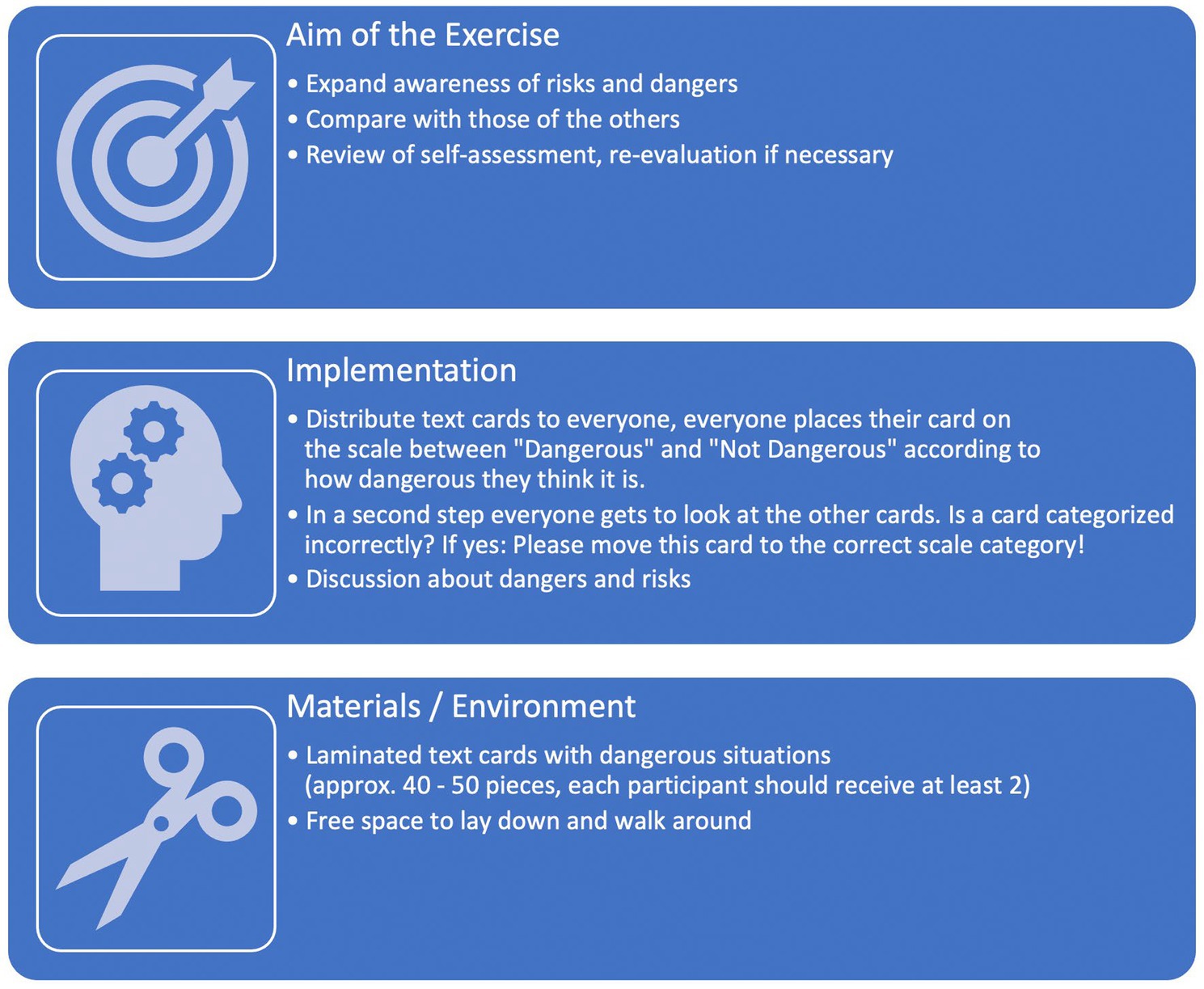

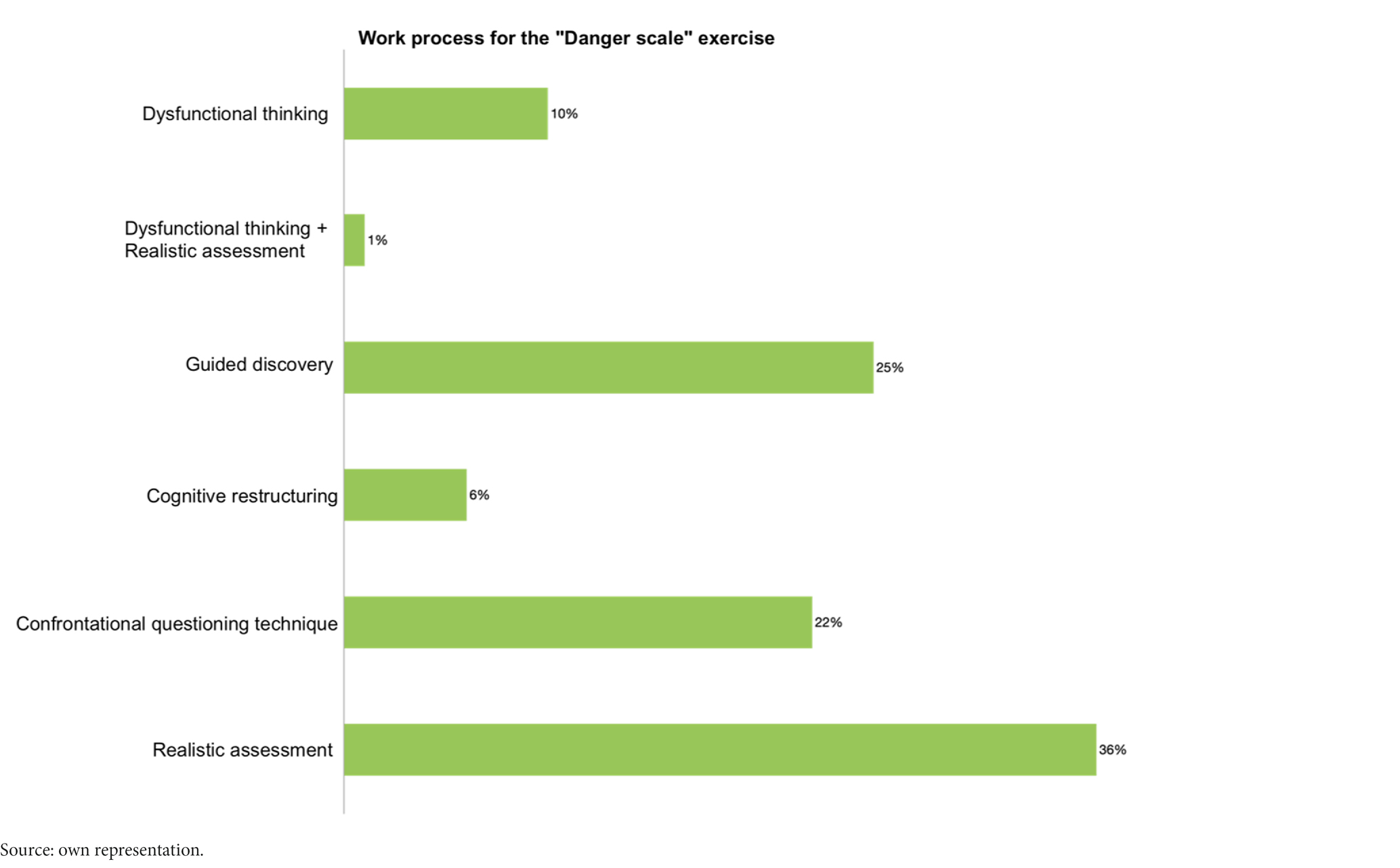

3.3.1 The “danger scale”

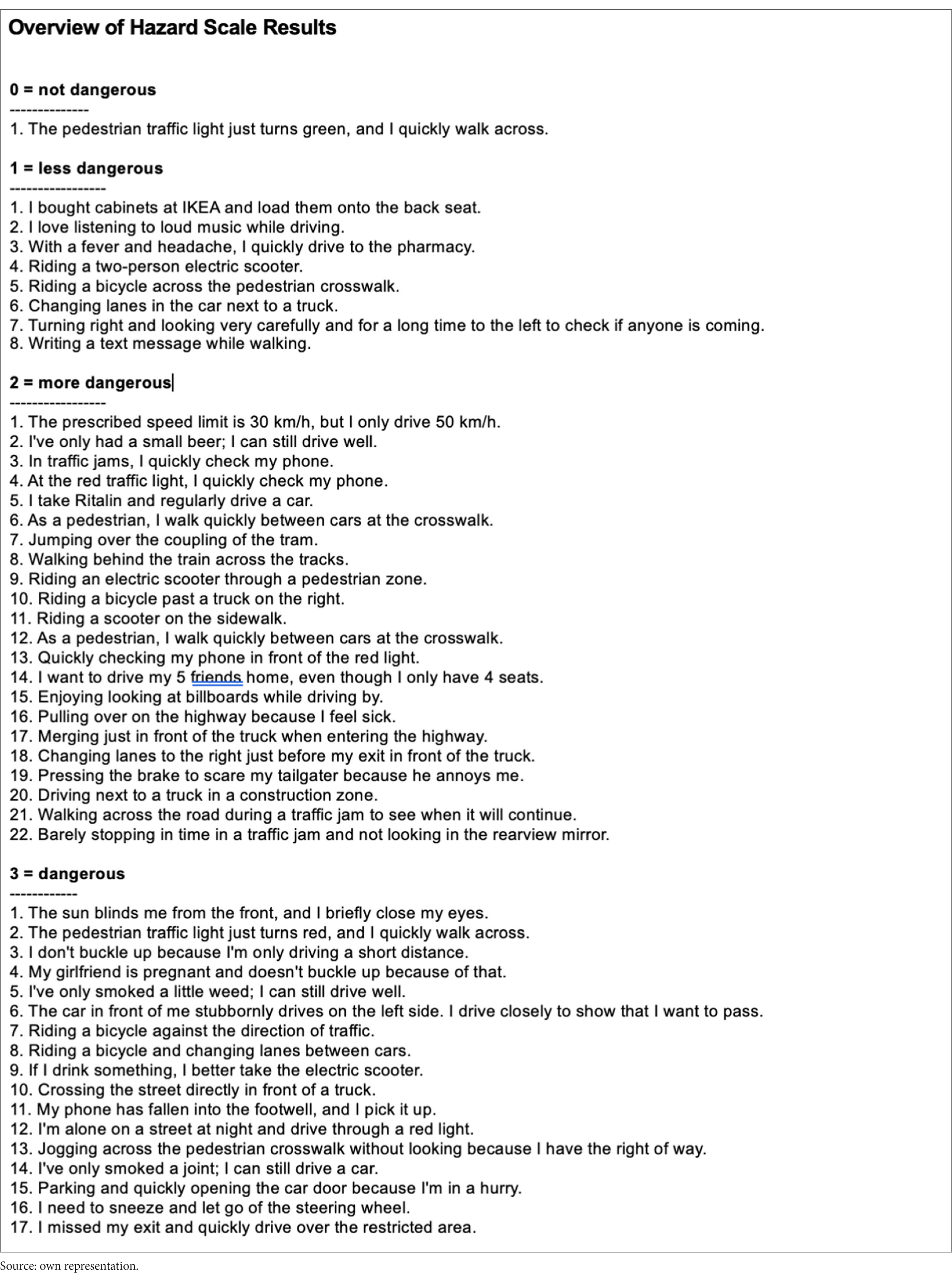

By developing a danger scale along a marked axis between the extremes of “dangerous” and “not dangerous,” the participants took responsibility for their own subjective perception of danger and their assessment of the dangerousness of various traffic situations. These individual assessments were then reviewed both within the class and in a moderated discussion, with a reassessment being carried out if necessary.

Repeatedly picking up and rearranging maps with depicted dangerous situations was a regular step. The accompanying moderation focused on weighing up the advantages and disadvantages of the hazard assessment of traffic situations and on presenting the current legal situation regarding these maps.

Guided discovery as a method from cognitive behavioral therapy was used to facilitate cognitive restructuring. The individual point of view and the perspective adopted were reconsidered as part of a Socratic dialog. By exposing and moderating contradictions, it was made clear that misconduct in road traffic is not beneficial and only appears logical on the surface. By creating confusion, distorted beliefs could be re-evaluated and dysfunctional distortions were restructured into realistic assessments (Revenstorf and Peter, 2015, p. 256).

The observation from the meta-level led to the realization that the previous way of thinking is only one of many possibilities and that alternative perspectives are just as realistic (Beck, 2013, p. 223 ff.).

The use of various disputation techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy, such as the logical, empirical and hedonistic style of disputation, made it possible to ask critical questions about thinking and behavior. These techniques encouraged deeper reflection on the motivations behind certain thought patterns, for example in relation to speed and road safety (Margraf and Schneider, 2018, p. 647).

Overall, these exercises initiated and anchored a process of cognitive restructuring. Joint discovery in the peer group played a decisive role in this process (von Beesten and Bresges, 2022) (see Figure 4).

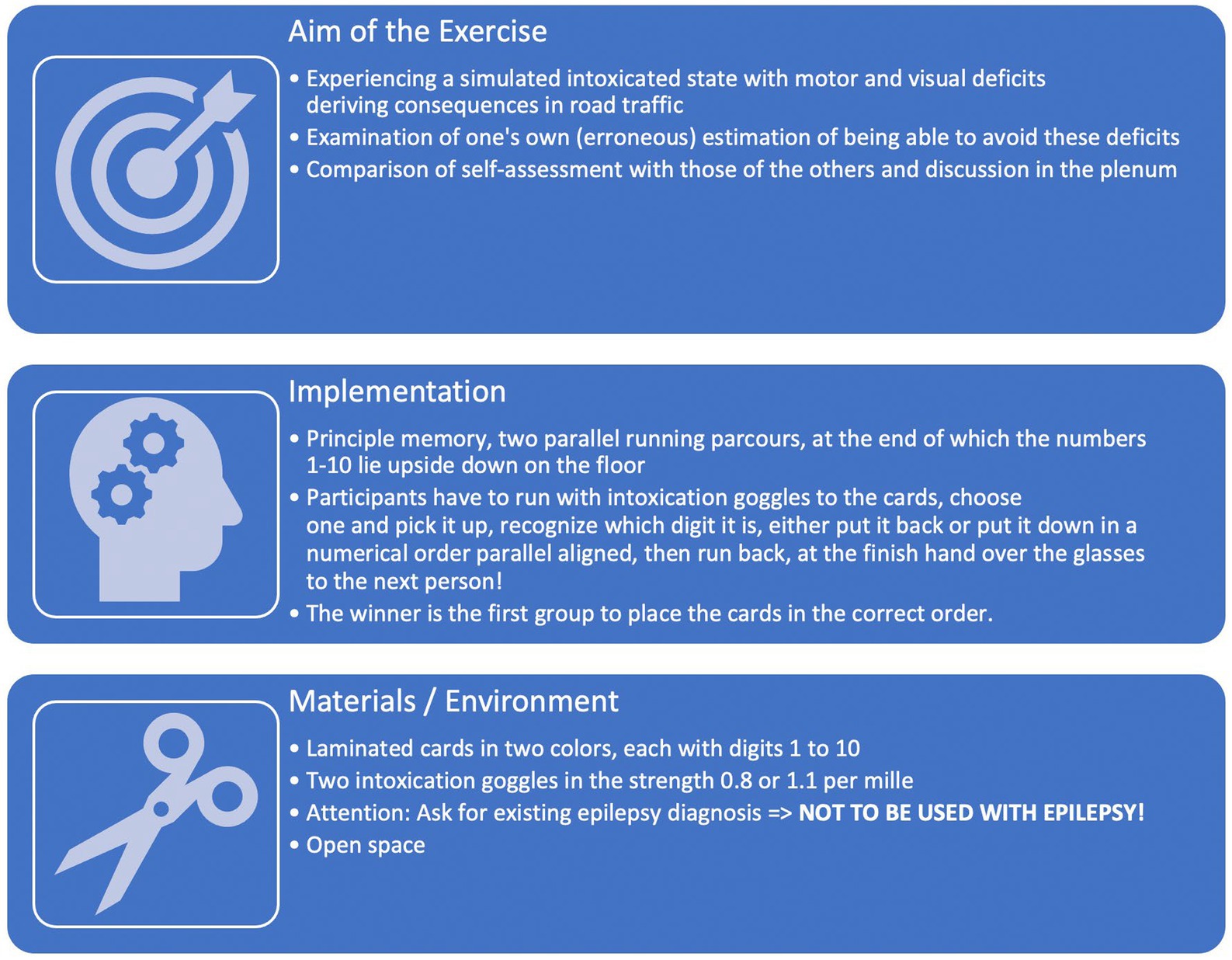

3.3.2 The “intoxication goggles memory”

Authorities and institutions dedicated to traffic accident prevention and education, such as the police, German Road Safety Association, ADAC and educational institutions, integrate intoxication goggles into campaign days and driver safety training courses to warn against the risks of alcohol consumption. These goggles have the ability to simulate different blood alcohol levels, creating visual impairments such as limited all-round vision, double vision, misjudgement of proximity and distance, confusion, tunnel vision, delayed reaction times and a feeling of insecurity. However, it should be noted that certain speech effects, such as “babbling,” cannot be authentically reproduced (source: manufacturer Alcovista®,6 November 23, 2023).

The simulation is limited to the visualization of selected intoxication effects, which are presented in a gradual representation of the blood alcohol concentration (BAC). The effects observed during the exercise were discussed with the group and served to examine dysfunctional assumptions with the help of the above-mentioned disputation style and Socratic dialog. As part of the exploration, an exchange of experiences on the effects of alcohol took place, whereby the legal basis and the associated consequences were also explained (von Beesten and Bresges, 2022) (see Figure 5).

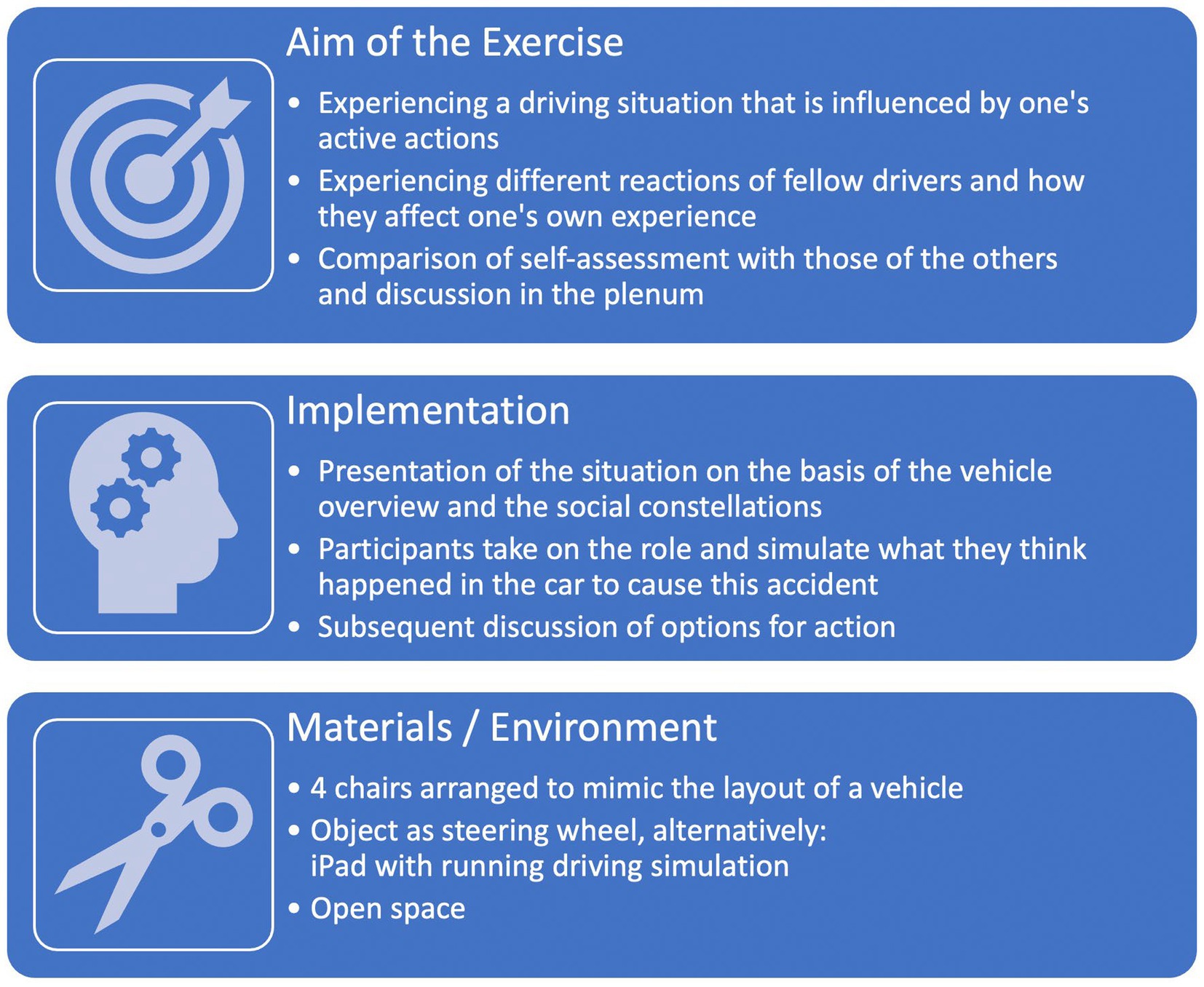

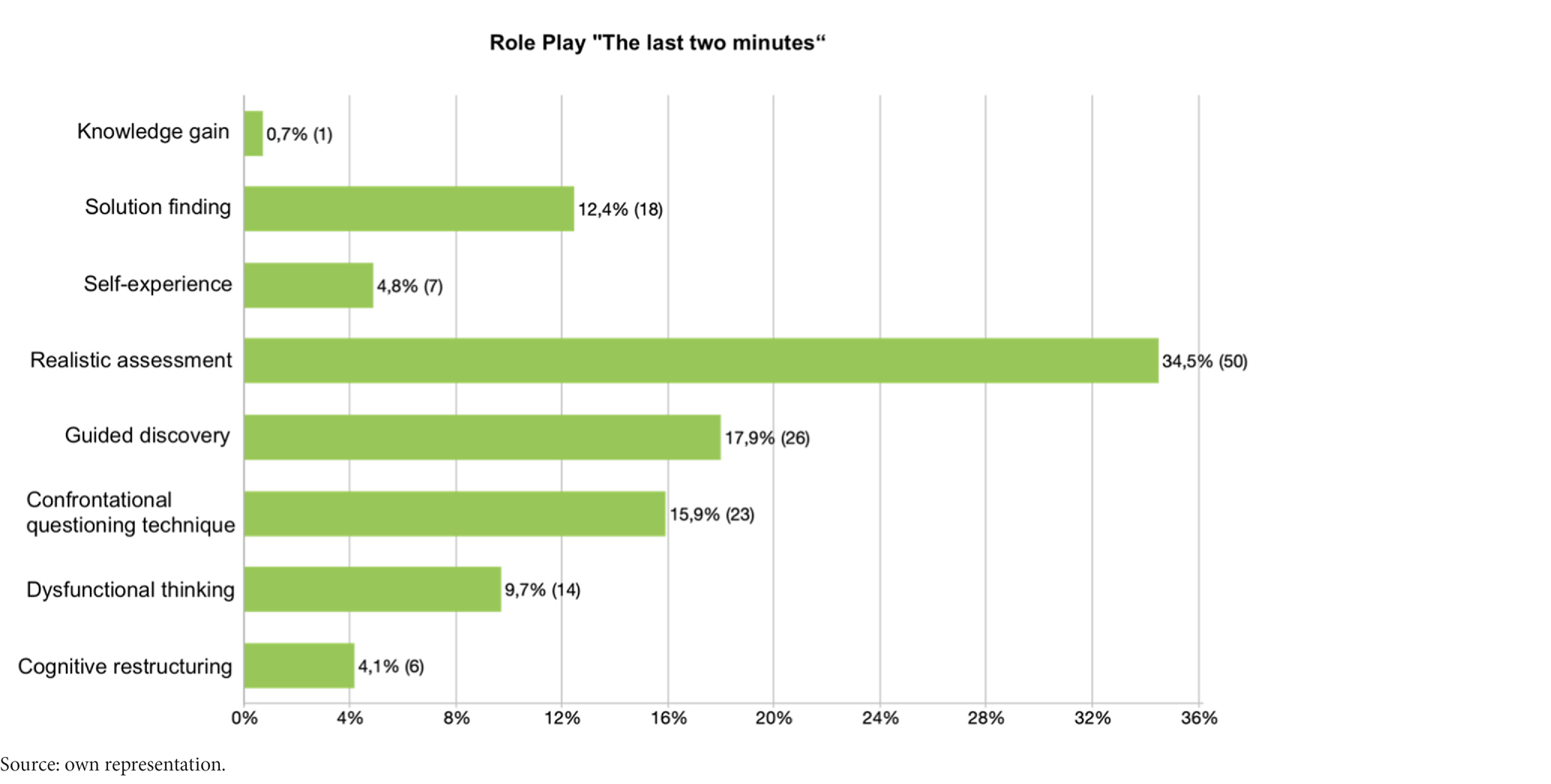

3.3.3 The role play “The last two minutes”

The participants simulate a driving situation in which they can actively influence and test what happens through their own actions.

The typical causes of serious injuries in road traffic had been taught to the participants in the previous exercises and were therefore familiar with them.

However, knowing something does not necessarily mean being able to protect yourself against it. Initiating a specific action requires more than just the desire to do it and knowing how to do it, according to the “Rubicon model” by Weinert et al. (1987, p. 3 ff.). It is also essential to be able to access behavior that has already been actively performed, which can then also be recalled during stress.

According to Margaret Wilson’s theory of “embodied cognition,” it may also be possible to recall a behavior that is already known, an action sequence that has already been thought through, during stress. According to this theory, the body, mind and environment influence each other in the way we think, feel and act. Our thoughts trigger embodied reactions and vice versa (Wilson, 2002, p. 625). This means that every perception, both positive and negative, is stored as a body memory with the corresponding physical attitude at the time experienced. In this role-playing game, the assumption would be that the experience at the time of the driving simulation, including the associated posture and behavior, could be fully remembered and reproduced as an automatism in a later re-experience (Wilson, 2002, p. 634).

In this role play, the pupils are therefore asked to put themselves in the situation of a vehicle two minutes before a fatal crash. The social situation in the vehicle is presented to all pupils, e.g., by reading out the following text or by presenting a corresponding role diagram:

Through a conversation with the parents of one of the people involved in the accident, we know that the couple in the front seats were arguing when they left their parents’ house. Jan and Marc are close friends, and Marc would never publicly criticize Jan, even if he made a driving mistake. Steffi is in a particularly socially awkward position: she has only been dating Marc for two weeks and this is the first time the group has taken her out in the evening. If she speaks out critically, she risks making a bad impression.

Exercise assumption: All the occupants of the car were killed in a night-time collision with an avenue tree at the weekend (source: University of Cologne, Crash Kurs NRW, November 23, 2023). Role-playing automates thoughts and behavioral sequences and reactions to them. By trying out new behaviors, assumptions and basic assumptions are changed, which in turn leads to new skills. Participants identify their own borderline situations and weak points and can develop solution scenarios (Beck, 2013, p. 257).

The role play initially offers a change of perspective from the outside role to the influential driver and passenger role, and gives participants the opportunity to actively lead a car journey to disaster.

Consciously bringing about a disaster with a subsequent analysis of the risk factors should, conversely, reveal protective factors that could have helped to prevent it (Beck, 2013, pp. 226–235).

Example: Loud music distracted the driver. Derived protective behaviors: Turn down music in the vehicle or turn it off completely.

We use participant observation to explore whether this type of educational role play is suifor recognizing risky actions in drivers. Furthermore, we test whether the passengers can recall and apply practiced actions to defend against risky behavior under simulated realistic conditions.

Intended goal: Educational role-playing should enable the recognition of dysfunctional actions and lead to more safety- and risk-conscious behavior by practicing modified functional actions (von Beesten and Bresges, 2022) (see Figure 6).

Following the in-class follow-up, the class completed the online posttest.

The analyses of the interviews, the observations and the discussions during the three tools were carried out with the program MAXQDA®.

The online survey of the posttest was conducted with the program LimeSurvey®. The posttest was analyzed using the SPSS® program.

3.4 Research of the reactance behavior

The pretest and posttest survey sets included reactance scales designed to measure the extent of reactance or resistance to a change or behavior. The two sets of pretests were divided into “with” and “without” police so that any differences could be measured. Reactance plays an important role in human behavior and decision-making processes. Understanding when and to what extent reactance occurs contributes significantly to counteracting it with appropriate measures and to improving the traffic accident prevention campaign to make it more effective. This can reduce the likelihood of rejection in the target group and increase the aspect of safety behavior.

In order to measure reactance, the present research work was based on excerpts of the questionnaire for the assessment of traffic-relevant personality traits (TVP) (Spicher and Hänsgen, 2003).

3.5 Theory-practice transfer of physical laws

The participants of the present research group were members of a technical vocational college. Hence, they already had a basic understanding of physics and technology and how they make sense of things. This could be confirmed by the statements made.

Accordingly, the probability that physical laws may be explained more effectively by practical observation and participation in an exhibition on the damaged car is very high. This is because practical experience and observation often make a stronger impression on our brain than merely theoretical explanations (Rösler, 2016, pp. 12–16).

By looking at and examining the car involved in the accident, it is possible to see, for example, how the forces affected the vehicle, how, where and with what force the impact occurred and what the consequences were. Due to the lack of a physics teacher, such an evaluation could not be done in this research round. There will be another research round that will address this question in particular.

4 Results

4.1 Results of the quantitative methods

4.1.1 Results of the reactance test related to the police presence

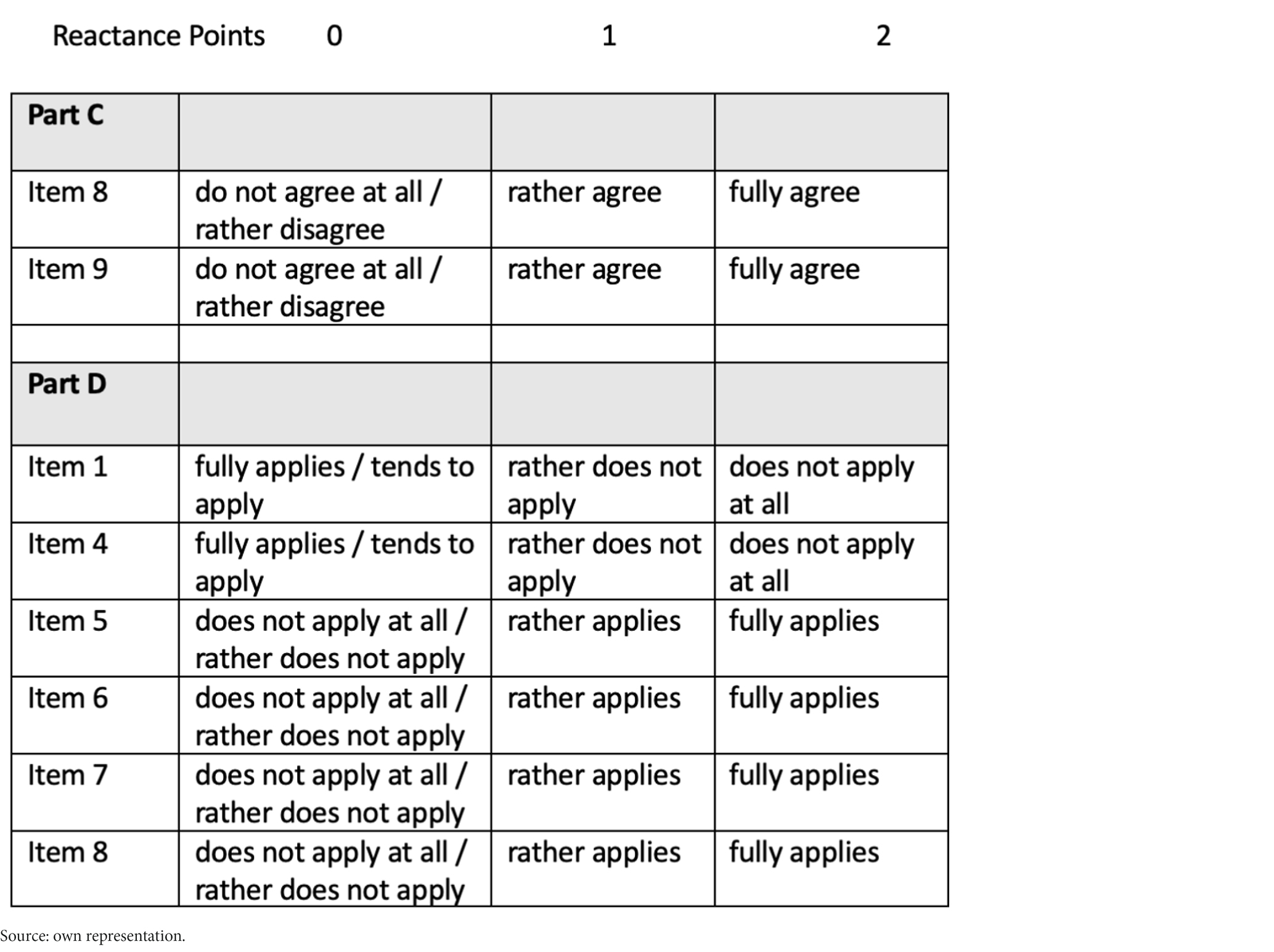

For this purpose, the reactance scores of both groups were first determined using the items from the pretest by assigning different points for the responses. The items chosen to measure reactance were as follows:

Part C/Item 8: I like to react to prohibitions with a “Now more than ever.”

Part C/Item 9: I’m not interested in all these topics, because I do what I want anyway.

Part D/Item 1: I want to prevent the same thing from happening to me.

Part D/Item 4: I think it is important to talk about traffic accidents.

Part D/Item 5: I was annoyed.

Part D/Item 6: I would have preferred to leave the event.

Part D/Item 7: The event was a waste of time.

Part D/Item 8: An accident like this will not happen to me anyway.

Table 1 shows the points assigned to determine the reactance values:

The sum of all reactance values of the different items then results in the individual reactance value of the respective participant.

This overview provides the frequency distribution of both variables and thus gives information on how often a certain reactance value was reached in the respective group.

To examine whether there is a dependence between police presence and reactance score, the chi-square test was applied. The chi-square test tests with a significance level of 5%. If there is no dependence, p-value > 0.05, the null hypothesis is retained, otherwise it must be rejected. In this case, the null hypothesis is that the presence of the police and the determined reactance value are independent of each other.

For a chi-square test to be applied, the following conditions must be fulfilled:

1. The variables are normally distributed

The variable of police presence is normally distributed. Also, the reactance value is to be regarded as normally distributed in this case, since only the achieved value of a person and not whether the person has a better or worse value is of interest.

1. Independence of measurements

This is given here, since both groups consist of different participants and every participant is only present in one of the groups.

1. Each cell has at least a frequency of 5

This information is provided by SPSS.

Since 75% of the cells have an expected frequency less than 5, the credibility of the chi-square test may be doubted, since this may have led to an inaccurate or rather false p-value. Thus, the last requirement for the application of the chi-square test is violated here.

For this reason, the Fisher exact test is used, as it provides reliable results even for a small sample.

Fisher’s test yields a two-tailed p-value of 0.447, which is greater than 0.05. Accordingly, the null hypothesis can be retained. This means that there is no significant relationship between the presence of the police and the reactance value.

4.1.2 Results of the reactance test related to the instructional follow-up concept

In the following, the research question “Can the instructional follow-up concept already developed for Crash Kurs NRW also be used to reduce reactance in this changed context?” will be answered. For this purpose, it will be investigated whether a difference exists between the determined reactance values of the participants before and after the follow-up and, if it does exist, how such a difference might arise. By means of the paired t-test, it is first checked whether a significant difference exists. For the paired t-test to be used, the following conditions must be met:

1. Dependence of the measurements

The individual measurements must be dependent on each other. This is the case here, since each participant completed a pretest and a posttest and these could be assigned to the participants by means of an anonymous identifier. This made it possible to create a table with the reactance value of a person before the posttest and the reactance value of the same person after the posttest.

2 The dependent variable is at least interval scaled

In this case, the dependent variable is the reactance value, so this condition is fulfilled.

3 The independent variable is normally distributed and has two expressions

The independent variable in this case is the respective time of the measurements. This corresponds to the pretest before follow-up and the posttest after follow-up.

4 Data should not have outliers.

5 The differences of the data from the different time points should be normally distributed.

The last two conditions could be checked by means of SPSS. For this purpose, the difference between the values from the pretest and posttest was calculated and then generated as a new variable. With the help of this variable, an explorative data analysis was carried out to check both conditions.

This yielded the result that there were no outliers in the data set. Thus, the fourth condition was also fulfilled. To check the differences of the pre- and posttest values for normal distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied. The result can be seen in the Supplementary Table S1.

The Shapiro–Wilk test yields a value of 0.115. Since this value is greater than the significance level (0.05) with which this test tests, it means that the differences are approximately normally distributed. Thus, all requirements are met to be allowed to use a paired t-test. The result of this paired t-test can be seen in the Supplementary Table S3. Since a significance level of 0.05 was used to test and t (23) = 0.551, p = 0.587 exceeds the critical value, it can be determined that there is no significant difference between the pretest and posttest reactance values.

4.1.3 Results of behavior change related to instructional follow-up

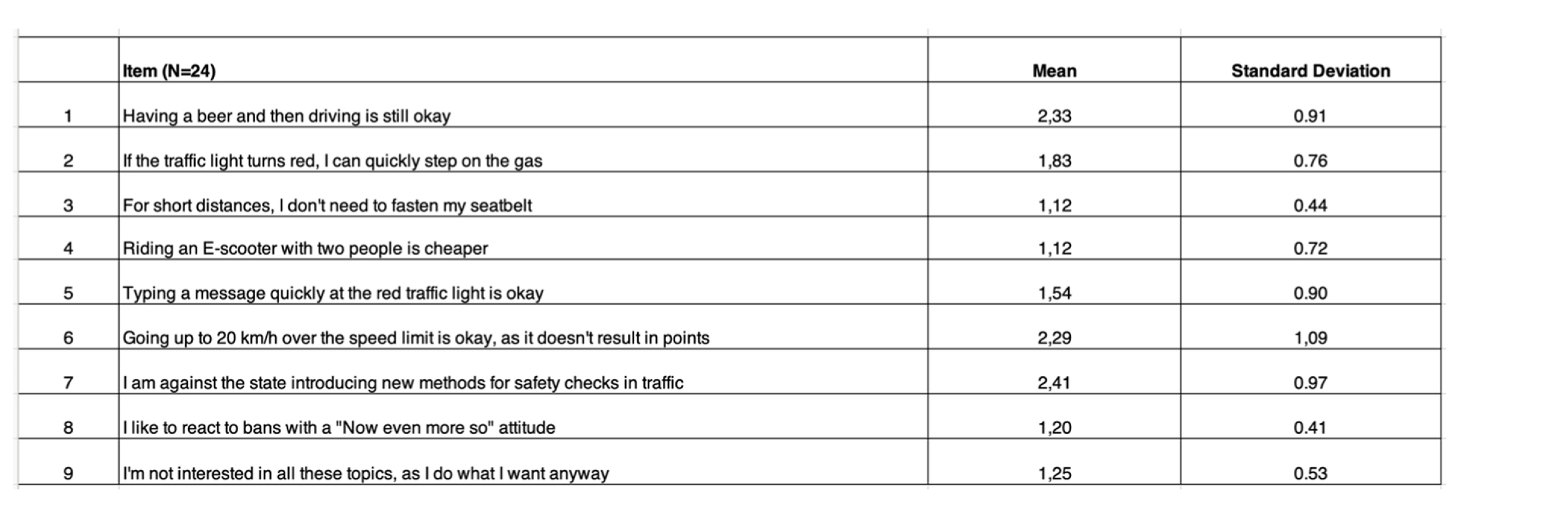

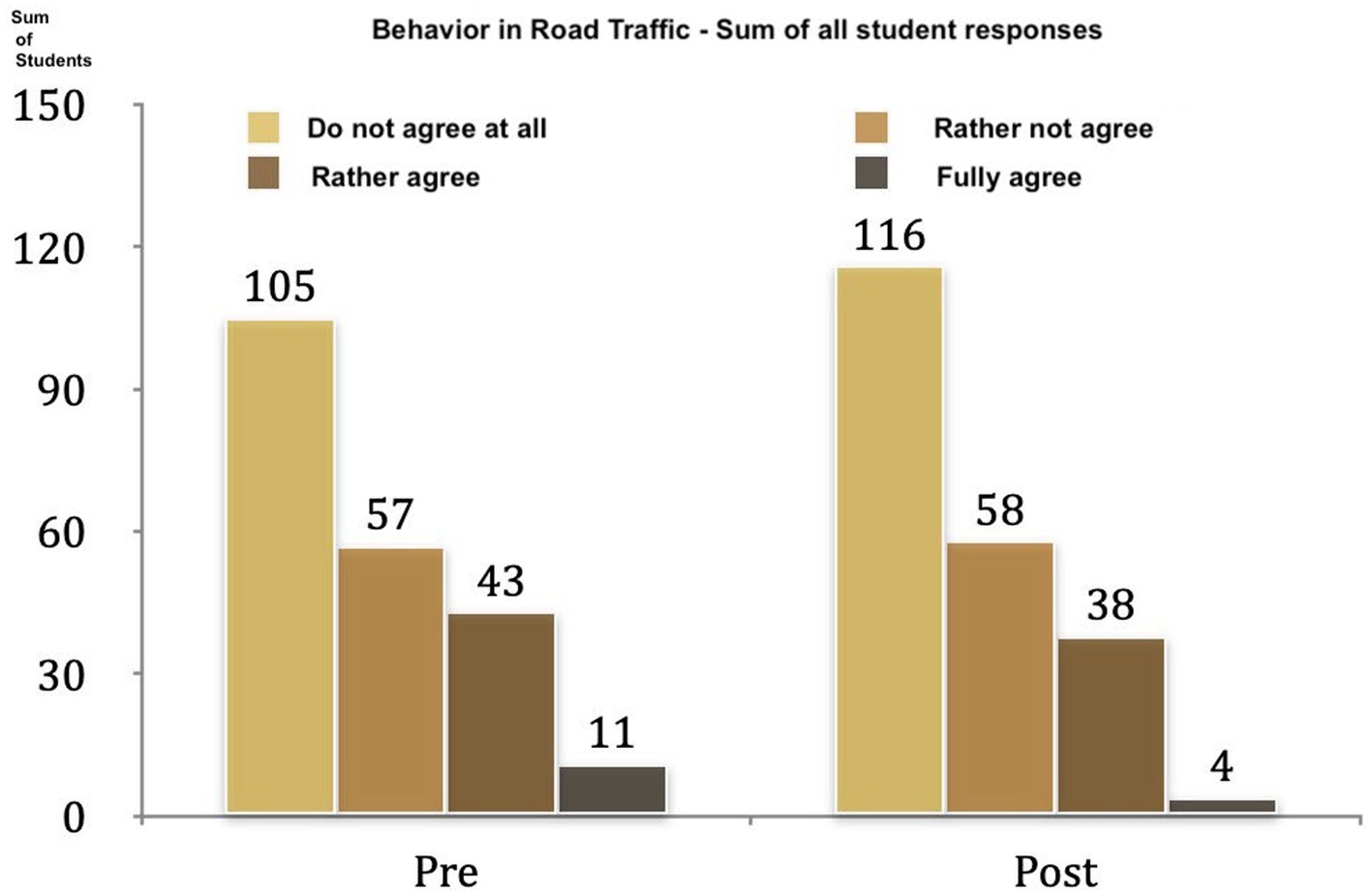

The first step was to compare the participants’ responses in the “Behavior in road traffic” section between the pretest and the posttest. The results shown in Figure 7 make it clear that the ideal answer for all items should be “strongly disagree,” in line with the message conveyed during the classroom follow-up. Figure 7 shows a summary of the results for all nine items. Accordingly, there was a successful change in behavior, as the participants no longer agreed with the statements of the items after the intervention.

Figure 7. Comparison of item responses pretest and posttest in the query section. “Behavioral changes” (source: own representation).

Now that the overall overview of the changes between the pretest and posttest has been presented, the individual items are examined in detail. This examination enables a more precise insight into the specific changes in behavior in road traffic and contributes to the comprehensive analysis of the intervention effects.

This will be analyzed in the further course by determining the transition of the responses from “Agree somewhat” and “Agree completely” in the desired direction. For this purpose, a table was created for both the pre-test and the post-test, documenting the responses of each individual person. The answer “Agree somewhat” was weighted with one point and the answer “Agree completely” with two points. It is also assumed that the answers “Strongly disagree” and “Strongly disagree” correspond to the desired behavior and therefore zero points are awarded for such answers. The difference between the sums of the individual values for each person in both tests can now be used to determine the change.

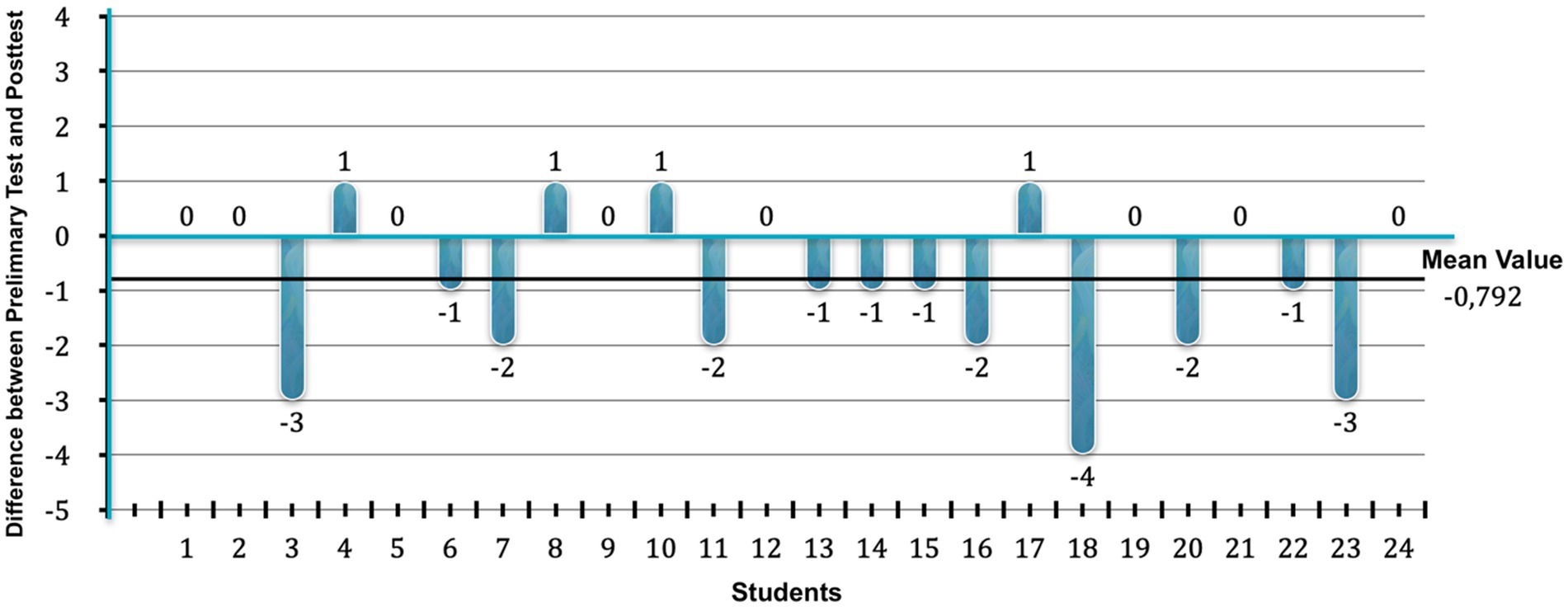

A positive value signifies that the respective participant “agreed” more often in the posttest than they did in the pretest, indicating an undesired outcome. By contrast, a negative value expresses that the desired effect was produced. A zero indicates, that the ticking behavior remained the same.

Figure 8 already shows that the follow-up led to an improvement in the attitude toward one’s own behavior in road traffic. This was checked in concrete statistical terms using the paired t-test.

Figure 8. Difference in points between pretest and posttest in the “Behavior in road traffic” section (source: own representation).

The aforementioned prerequisites four and five from Section 4.1.2 were again checked using SPSS. These showed that there were no outliers in the data set. The Shapiro–Wilk test returned a value of 0.043, which meant the difference in the pre- and postvalues were not normally distributed in this case. However, since the paired t-test is relatively robust to violations of the normal distribution assumption, this result could be neglected and the paired t-test could still be performed. The result of the paired t-test can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Thus, the scores for ticking consent responses were significantly lower after the posttest than before in the pretest, t (23) = −2.805, p = 0.010. Accordingly, the paired t-test confirmed the assumptions based on Figure 6.

Subsequently, the strength of this effect was determined using Cohen’s d in SPSS. The statistical measure of the strength of Cohen’s effect d is shown in Supplementary Table S6.

The result showed an effect size of 0.573. According to Cohen, this corresponds to a moderately strong effect. Therefore, it can be concluded that the conducted follow-up can contribute to a desired change in attitude or behavior. Although not all participants were reached to the same extent, this effect is still statistically significant.

In summary, it can be observed that due to varied reactions within a target group despite identical fear appeals, it can be assumed that not all female and male students were reached equally. This is influenced, among other factors, by gender-specific differences. In the analysis of behavior change, it was evident that a higher percentage of female students (60%) were reached compared to male students (~43%). This aligns with the expectation that women tend to react more sensitively to fear appeals and are more likely to comply. Surprisingly, male students exhibited a “stronger” change, despite literature suggesting that men usually resist fear appeals involving physical threats.

The dependence between gender and behavior change was further investigated using the Chi-square test. The null hypothesis, stating that gender and behavior change are independent, was retained as the Chi-square test yielded a value of 8.77. Due to expected frequencies smaller than 5 in all cells, the exact Fisher’s test was employed. The two-tailed p-value was 0.110, and as it is greater than 0.05, the null hypothesis remains. Therefore, no significant relationship between gender and behavior change could be established.

Overall, this suggests that a desired improvement was achieved in half of the female and male students. Consequently, such a program for traffic accident prevention in schools appears to be meaningful.

Following the analysis of the individual items, Cronbach’s alpha can be calculated to check the internal consistency of the data collected. The assessment of reliability ensures that the items in the survey represent a reliable measurement of the construct under investigation. This step deepens our understanding of the stability and accuracy of the information collected and enables a well-founded interpretation of the overall results.

The calculated Cronbach’s alpha values provide an assessment of the internal consistency of the items in a scale. In this case, the Cronbach’s alpha for the raw items is 0.675 and for the standardized items 0.708, whereby the scale consists of nine items in total.

In general, a Cronbach’s alpha value of over 0.7 is regarded as an indicator of acceptable to good internal consistency. In your case, both values are in this range, which indicates that the items in the scale correlate with each other and measure the underlying construct consistently. The slightly higher value for the standardized items could indicate that the consistency of the scale was slightly improved after standardization. Overall, however, the available values indicate that the scale has an acceptable internal consistency (see Table 2).

Having looked at the reliability of the items, we now take a look at the mean ratings for each item. This allows for a more detailed analysis of the specific aspects of road behavior under investigation and helps to paint a more comprehensive picture of the results (see Table 3).

The overall mean values confirm the indications of changes in the research results presented.

1. mean value of the pretest of the control group without police (N = 11): 1.93

• This value represents the average level before any intervention or treatment in the control group.

2 mean value of the pre-test of the comparison group with police (N = 13): 2.28

• This is also the average score before the intervention, but in the comparison group that experienced the police intervention.

3 mean value of the post-test (N = 24): 1.70

• This value shows the average level after the intervention in both groups, regardless of the type of intervention.

The findings indicate that the intervention had significant positive effects on the reactance values. This is supported by the statistically significantly lower mean score in the posttest compared to the pretests. Some items of the safety behavior scale (see Table 4) showed also positive effects, but this does not apply to the entire scale.

Table 4. Result of the “danger scale” exercise, sorted according to the filing categories of the Likert scale.

4.1.4 Results on the effectiveness of the individual exercise tools

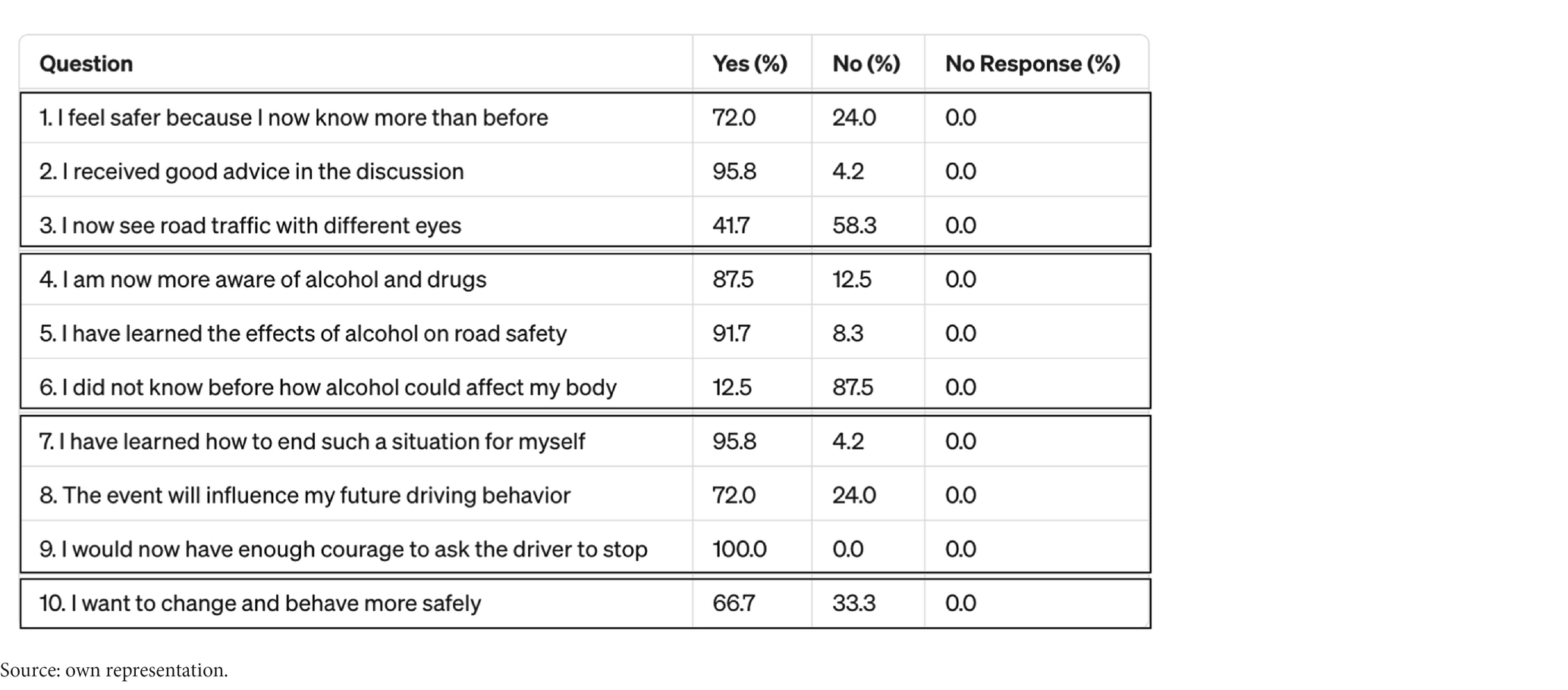

Table 5 shows the percentage responses to a series of questions that were asked at a road safety event. The questions can be assigned to specific areas of competence: Questions 1 to 3 cover the competence area of recognizing and assessing, while questions 4 to 6 cover the competence area of experiencing and evaluating. Questions 7 to 9 reflect the competence area of testing and implementation, while question 10 addresses the area of motivation to change.

The answers to these questions offer a differentiated insight into the various competence dimensions of the participants in relation to road safety. The evaluation enables an assessment of the effectiveness of the content presented on the various aspects of safety competence and clarifies the extent to which the event has had an influence on safety awareness, knowledge transfer and motivation to change behavior in road traffic.

The comparison between the pretest and posttest suggests that educational interventions and practical experience can have an influence on participants’ attitudes and opinions on various aspects of road safety. In particular, there was a positive change in the rejection of risky behaviors such as drinking and driving and speeding at red lights in the posttest. This suggests that the educational measures implemented may have been effective and led to an improved understanding of traffic risks.

The data also indicates an increased awareness of the effects of drinking and driving, particularly through experiential approaches such as wearing intoxicated goggles. In addition, positive responses to discussions and role-play show that interaction with other participants or hands-on experiences can promote learning effects.

However, it should be noted that changes in the willingness to take risks are also recognizable, such as the tendency to react to prohibitions with “now more than ever.” Further differentiated analysis is required here in order to understand whether these changes are beneficial or detrimental to road safety.

In summary, the data point to the diverse effects of educational measures on attitudes, perceptions and behaviors in the context of road safety.

These findings are consistent with the results of a previous study of school students, as documented in a previously published article at https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046403 (von Beesten and Bresges, 2022). This suggests that the implemented form of follow-up has brought about positive changes in terms of competence behavior in road traffic.

The additional qualitative evaluations of the audio description in this study further deepen and underpin this positive effect.

4.2 Results of the qualitative methods

4.2.1 Results of the observations on the exhibit

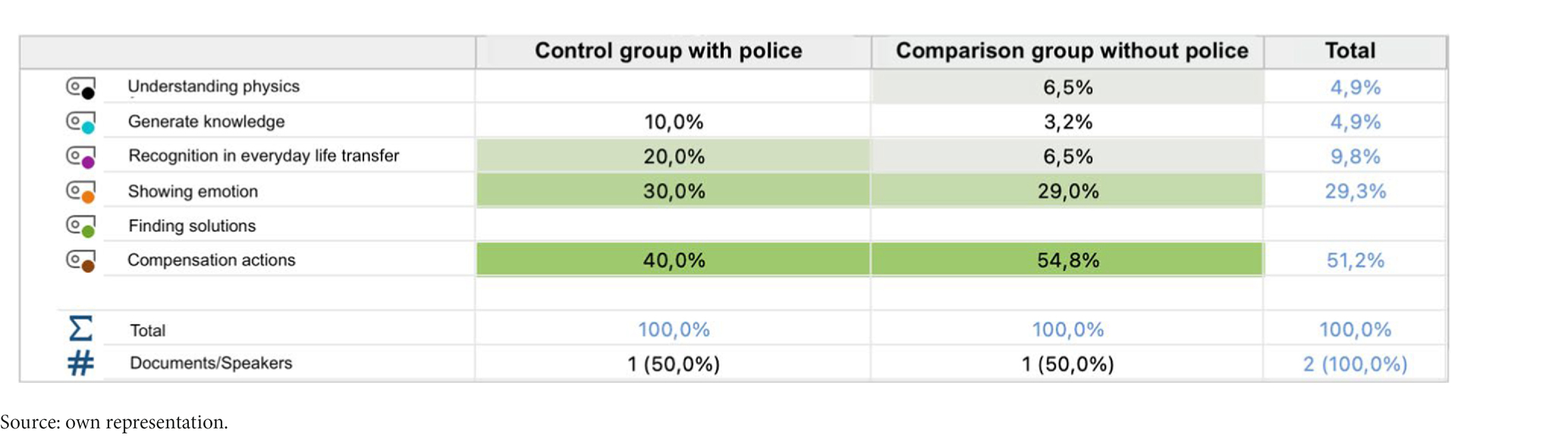

A comparison of the two research groups in terms of behavior at the exhibit could be presented in the evaluation with the help of a cross-table the following results (see Table 6).

Table 6. Comparison of the research groups at the exhibit, group 1 without police, group 2 with police.

The overview shows that through the briefing and the explanations from the police, the gain of knowledge in the topic of traffic safety was significantly higher. Already during the first explanations of the exhibit, the subject matter, the classification of the topic and also the traffic accident in the local events were more strongly recognized and could thus be better assigned to one’s own life context. Defense mechanisms due to emotional bias as a result of personal familiarity with the accident, which was equally present in both groups, did not require as many compensatory action strategies in the group moderated by the police as in the group without moderation. The reason for this could be a high level of acceptance of the police officer’s expertise and credibility in communicating the traffic-related issues. During the quiet conversations among themselves, participants in the unmoderated group focused more thematically on what was familiar to them in the context of the professional situation of their constellation. These included physical concepts. By contrast, these were not addressed in the police facilitated group. This implies that purposeful moderation on physics related topics opens up different solution paths than moderation by police officers, who tend to provoke normative and rule-conforming behavior in the group. Both approaches are promising. It would be worth considering alternating both approaches in a holistic course concept in order to reach a broader target group overall and to uncover and discuss a greater variety of possible solutions.

4.2.2 Results of the instructional follow-up

The analytical evaluations of the observations in the classroom follow-up are presented in Table 7.

This overview shows that the group of participants from a technical vocational college was already able to make realistic assessments of traffic situations in many cases. Concordantly, the proportion of dysfunctional thinking was low. The following overview demonstrates that due to prior knowledge, including their knowledge of physics, only little knowledge could be gained. This was discovered during the development of the danger scale, a filing system based on the principle of a Likert scale (see Table 4).

It can be seen that only a few cards were placed in the “Rather Not Dangerous” area and only one card in the “Not Dangerous at All” area. These cards, along with other topics, were part of the open discussion that followed. Dysfunctional thought processes were revealed via processes of confrontational questioning and guided discovery. Cognitive restructuring techniques led to new realistic assessments that supported existing realistic assessments. These findings are supported by previous research (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1046403, von Beesten and Bresges, 2022) in school, since the same cards were classified as supposedly harmless and only through discussion and exchange could the underlying danger be detected. Table 8 shows the statistical evaluation of this process:

The exercise with the intoxication goggles yielded the following results (see Table 9).

These results demonstrate that particular importance was attached to the visual perception disorders, the motor dysfunctions, and the associated misjudgments in the space-location structure. These are exactly those physical functions that are targeted by the intoxication goggles in the exploration.

The role play “The last two minutes” produced the following results (see Table 10).

Evidently, the group, which was equipped with a very realistic assessment, was able to come up with a good solution and was only able to achieve minor additional gains in knowledge.

4.3 Summary of the results

By considering all the statistical results of the online surveys and observations, calculated both qualitatively and quantitatively, as well as the questions raised on site in the focus groups, it was possible to reflect well on the research questions. The results make it possible to answer them.

The answers to the research questions are as follows:

Q1: Does the modified concept of exhibiting a damaged car generate less reactance than Crash Kurs NRW?

A1: Yes, the post-processing approach resulted in significantly lower reactance values.

Q2: Does the presence of police lead to increased reactance?

A2: No, the presence of the police does not change reactance.

Q3: Can the instructional follow-up concept be successful in terms of a targeted change in behavior?

A3: Yes, the instructional follow-up concept can successfully contribute to a change in behavior.

Q4: Is the exhibit of an accident car suitable for teaching physics topics?

A4: In the case of a targeted presentation on physical topics, the exhibit is suitable to explain and illustrate physical topics.

5 Discussion

5.1 Discussion of the scientific quality criteria

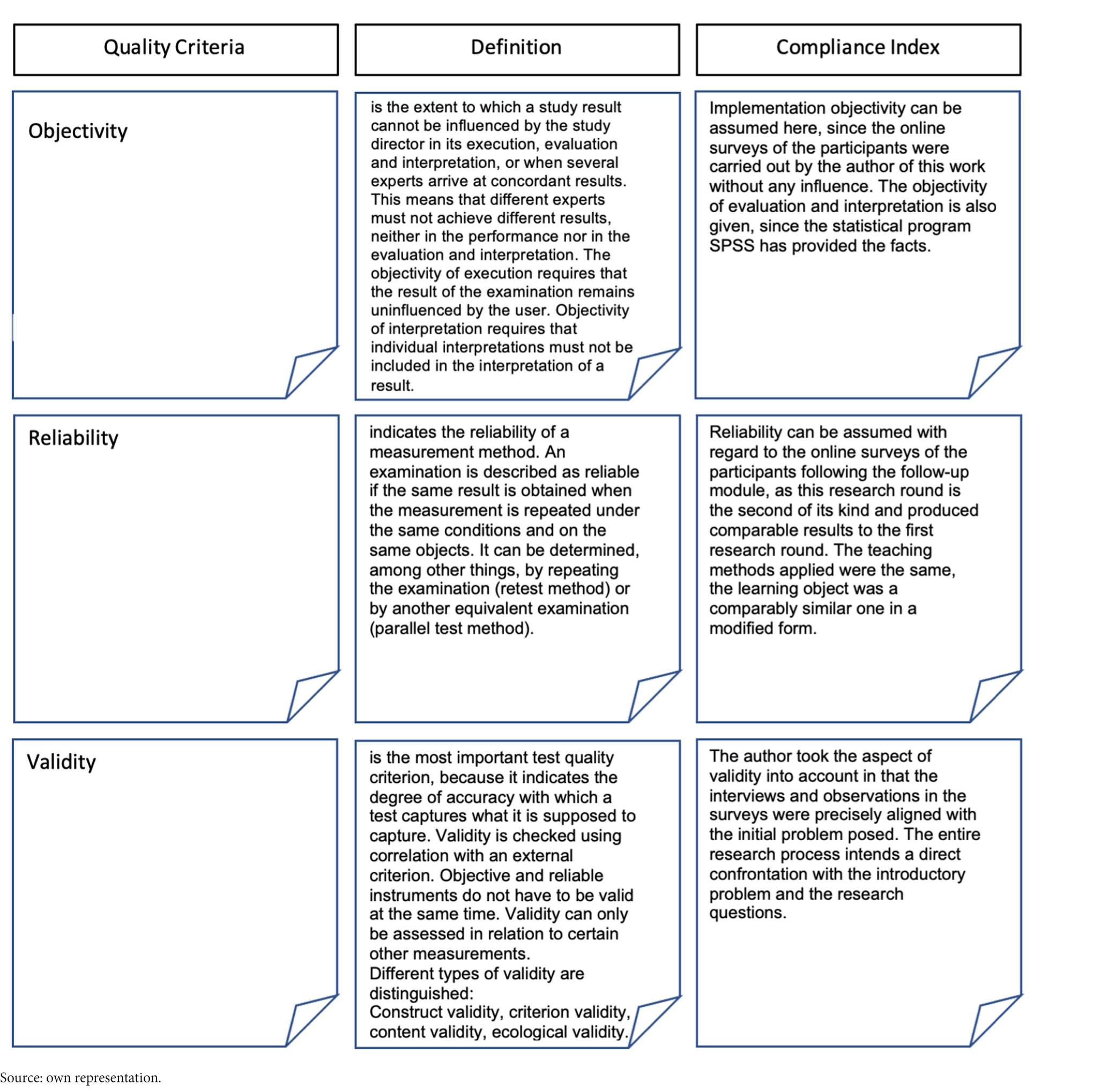

Compliance with scientific quality criteria plays a central role in the methodological reflection of scientific studies. These criteria serve to ensure the security, transparency, reliability and validity of scientific findings (Häder, 2010, p. 108). In the context of this research work, a differentiated consideration of quality criteria is necessary, focusing on two key aspects:

• Quality criteria of quantitative research: quantitative research methods are characterized by the systematic collection and evaluation of numerical data. The quality of such research approaches is assessed on the basis of various criteria such as validity, reliability and objectivity. Validity refers to the accuracy and appropriateness of the measured constructs, while reliability concerns the consistency and reliability of the measurements. Objectivity refers to the extent to which the results are independent of the individual assessments of the researchers (Häder, 2010, p. 108).

• Quality criteria for qualitative research: In qualitative research, the focus is on interpretation and understanding processes. Quality criteria for qualitative studies include criteria such as reproducibility (the possibility of retracing the research steps), transferability (the generalizability of the results to other contexts), consistency (the internal coherence of the results) and reflexivity (the researcher’s critical examination of his or her role and influence on the study) (Häder, 2010, p. 108).

Addressing these quality criteria helps to ensure the methodological quality of the research work and to make its results reliable and comprehensible. Care should be taken to ensure that the criteria are adapted to the specific requirements of quantitative or qualitative research.

5.1.1 Quality criteria of quantitative research

The aim of measurements in quantitative research is to collect the most accurate and error-free measured values possible. However, this goal is hardly ever fully achieved in research practice. The “classical test theory” allows very simple definitions of quality criteria for measurement. According to this, measurements should be as objective, reliable and valid as possible, and economical, comparable and useful for practical implementation. Objectivity and reliability are minimum requirements for a measurement instrument (Häder, 2010, p. 108), although the main goal is to construct instruments that are as valid as possible.

When evaluating a teaching module, this approach is impeded insofar as prevailing individual perspectives are reflected in subjective judgments, perceptions, attitudes, and views in the survey that affect validity (Schubarth, 2006, p. 282).

Since neither the follow-up Crash Kurs NRW nor the project of exhibiting a damaged car has any existing precedent, it was not possible to rely on already validated measurement instruments. The creation of the measuring instruments used were partly adapted to the context of the follow-up of this project and it was not possible to employ already validated existing questionnaires. Thus, despite having produced valid results, they did not fully meet the quality criteria in all areas, as scientifically required.

Furthermore, it must be acknowledged that the surveys were conducted at only one vocational college so far and the associated limited selection of participants could neither be randomized nor representative. Thus, these surveys provide information only as it relates to a product that has yet to be introduced on a greater scale. Therefore, the highest possible degree of fit exists only for previously studied needs. However, parallels are very clearly recognizable here.

The following overview explains the quality criteria and its fulfillment indices of the quantitative research part (see Table 11).

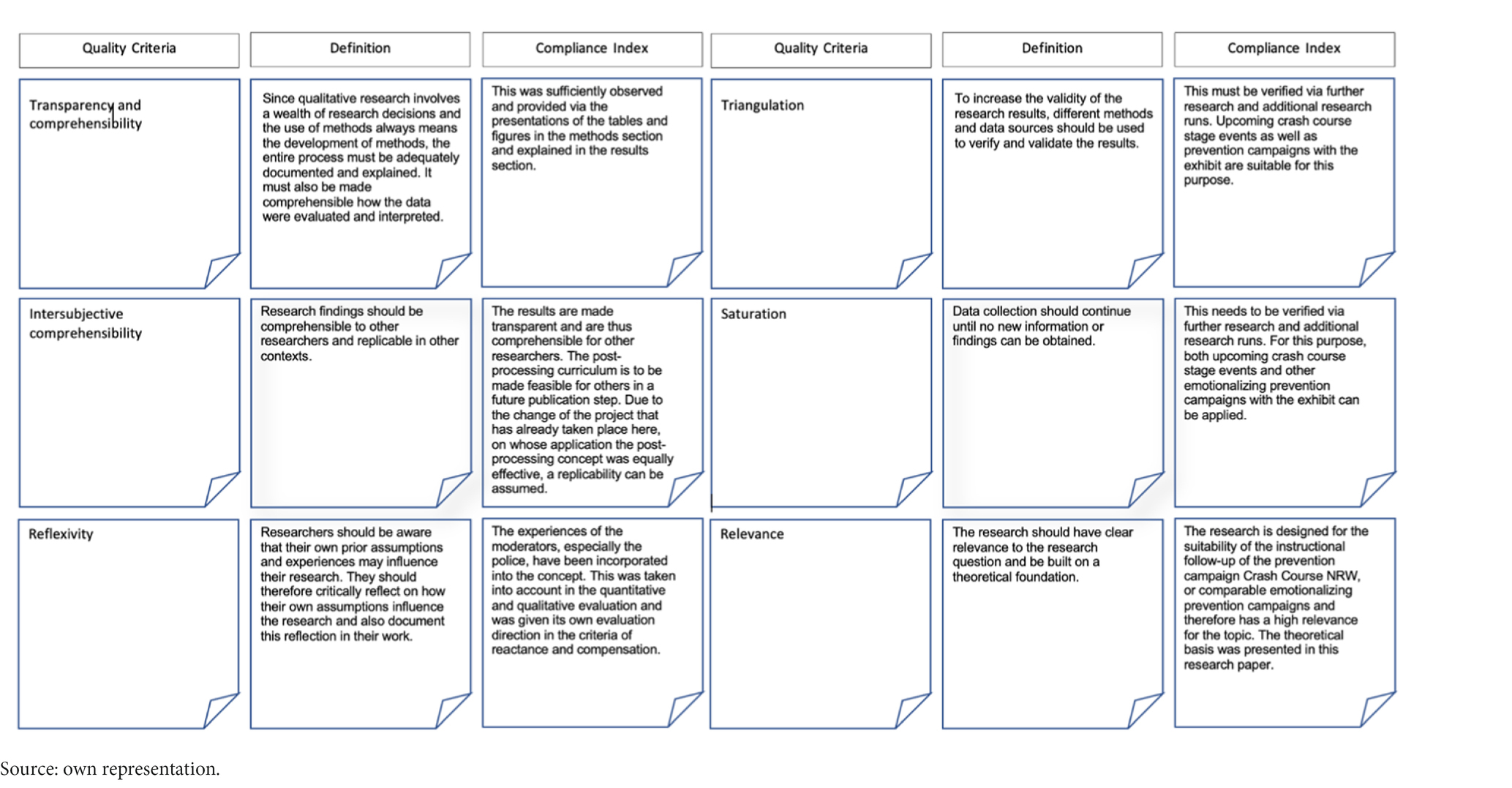

5.1.2 Quality criteria of qualitative research

In contrast to quantitative research, no generally accepted quality criteria have yet been established in qualitative research; rather, various differentiated proposals for the quality assessment of the qualitative methodological approach are available (Strübing et al., 2018, pp. 83–100).

The application of the classical quality criteria from quantitative research (objectivity, reliability, validity) to qualitative research is largely rejected. This is justified by the particularities of the qualitative methodological procedure, the epistemological positions on which they are based, as well as ethical and practical aspects of research. Among the multitude of proposed aspects for quality production and assessment, the overarching quality criteria of transparency, intersubjectivity, and scope appear to be particularly central (Strübing et al., 2018, pp. 83–100).

Kuckartz has developed various methods and techniques for qualitative research that focuses on the understandability of human behavior, the context in which it occurs, while keeping the perspectives of the subject open. The researcher is allowed to discover new aspects during the research and adapt the research question, developing theories and ideas in the process. Qualitative research can combine different methods in this process. The characteristics of qualitative research according to Kuckartz show that qualitative research aims to collect and interpret data that cannot be expressed in numbers, and that it focuses on a deep understanding of the phenomenon rather than focusing on statistical significance. The six research criteria according to Kuckartz were applied to present research and answered as follows in his fulfillment indices (Kuckartz, 2016, pp. 145–154) (see Table 12).

Table 12. Overview of the quality criteria of qualitative research and its fulfillment indices, according to Kuckartz.

5.2 Limits of the study

A pilot study can provide important insights and at the same time open doors for further research by highlighting certain limitations and potential areas for improvement (Gaus and Muche, 2017, p. 459). One limitation present here is the limited sample size of n = 24, which affects the generalizability of the results. Therefore, a next phase of research should involve increasing the sample size to allow for more representative conclusions.

Furthermore, pilot studies could capture short-term effects while long-term effects remain unconsidered (Gaus and Muche, 2017, p. 459). As a result, a further development of the present study should be to conduct a long-term study with several cohorts and interviews at several consecutive time points (post-survey 1, 2, 3 …) of the accident car in order to understand the longer-term developments in the participants more precisely.

In addition, pilot studies have the limitation that the effects may vary in different population groups (Gaus and Muche, 2017, p. 459). Therefore, an extension of the research should be to expand the study to different populations (age groups, school types) to identify possible differences.

Finally, new questions or hypotheses may arise from the pilot study that require further research to explore these aspects in more depth. Overall, these identified research limitations serve as a guide for the further development and refinement of the research.

The present study was able to prove that a campaign with an accident car as an exhibit generates less reactance than the stage campaign Crash Kurs NRW. It was also able to prove that the follow-up is suitable for minimizing reactance. However, it must be considered that the target group had little reactance beforehand. As a result, further research focusing on different target groups may be necessary: younger target groups with less prior knowledge about road safety and even more willingness to engage in risky behavior would be desirable for further test runs.

5.3 The research gap

The study did not conduct any surveys on participants with physical or psychiatric impairments that would have had a lasting effect on road safety, such as personality disorders or organic neurological disorders (e.g., malformations, epilepsy, schizophrenia). Thus, no findings could be obtained as to whether the concept also has an effect on psychological or psychiatric disorders, or whether it can make people more aware of any physical dysfunctions and thus help to clarify and stabilize misconduct.

5.4 Comparison with other research

In the previous research work, on the one hand, the instructional follow-up of the stage event Crash Kurs NRW was put under the aspect of minimizing reactance. On the other hand, an improvement of behavior with regard to road safety through the follow-up concept was put to the test. Both could be confirmed in the last research.

The main question posed by this research work was whether a comparably emotionalizing campaign could generate less reactance and then initiate the same successful behavioral change for traffic safety with the same follow-up concept. Both research questions could be positively confirmed.

6 Conclusion and outlook

The results of the various research questions provide a comprehensive conclusion on the effectiveness of the modified concept of an accident car exhibit and the instructional follow-up concept.

With regard to the research question of whether the modified concept of the accident car exhibit generates less reactance than the previous approach, the results clearly show that the follow-up concept leads to lower reactance values. This suggests that the modified approach to teaching accident prevention and safety measures is met with a positive response and generates less reactance than the previous approach.

The research question of whether the presence of the police leads to increased reactance is refuted by the results. It is shown that the presence of the police has no significant effect on reactance scores. Regardless of the presence of the police, participants show similar reactions and are not more or less resistant.

Regarding the research question of whether the instructional follow-up concept can successfully contribute to a desired change in behavior, the research results provide positive findings. It can be seen that the follow-up concept is effective in achieving behavioral change with regard to accident prevention and safety. Thus, the educational treatment of the topic after the accident event can contribute to the participants adapting their behavior and making safer decisions.

The research question as to whether the accident car exhibit is suitable for addressing physics topics in the classroom can also be answered in the affirmative. Under the condition of goal-oriented moderation, it is shown that the accident car exhibit can be used as a visual aid to vividly convey and explain physical aspects. It enables the students to better understand concepts of physics related to traffic accidents.

In summary, the results suggest that the modified concept of exhibiting a car that was damaged in an accident has a positive effect on participants’ reactance, while the presence of the police shows no significant effect on reactance. The instructional follow-up concept appears to successfully contribute to a change in behavior, and exhibiting the damaged car, under purposeful facilitation, is suitable for addressing physics related topics in the classroom. These results suggest that the new concept and the use of the exhibit can be effective methods to promote accident prevention and safety awareness.

Further research can support these findings and contribute to the advancement of the core curricula for physics education, as well as meaningfully integrate traffic accident prevention as a mandatory element in schools.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because research took place in accordance to state law. No personal data was recorded. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Data curation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We acknowledged support for the article processing charge from the DFG (German Research Foundation, 491454339).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1276380/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^ www.recht.de

4. ^ https://www.allianz.com/de/presse/news/engagement/gesellschaft/141029-allianz-zur-sicherheit-im-strassenverkehr.html

5. ^ www.bast.de

References

Bastian, T. (2010). Mobility-related attitudes in the transition from childhood to adolescence. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Wiesbaden.

Box, E. (2023). Mobility • safety • economy • environment. Empowering young drivers with road safety education. Practical guidance emerging from the Pre-Driver Theatre and Workshop. Education Research (PDTWER). RAC Foundations

Demuth, R. (2012). Theory-practice-transfer in physics education. In U. Kattmann/B. Schmid (Eds.), Experimenting in science education: Researching, discovering, inventing. Berlin: Springer.