Development of inclusive practice – the art of balancing emotional support and constructive feedback

- 1Department for Pedagogy, NLA University College, Bergen, Norway

- 2Department for Education, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

- 3Faculty of Education, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Elverum, Norway

Inclusive education in the context of challenging behavior is one of the most demanding challenges for teachers. Good support systems help teachers become more positive about inclusion and gain greater confidence in realizing that they can succeed. Such support can be provided in the form of emotional support, internal or external guidance, courses, discussions or further education. As an alternative to a traditional individual-oriented approach to inclusion, this article argues that development of inclusive practice requires collaborative learning in the professional community, which again means that teachers have to make their own practice more transparent so that it can be explained, explored and challenged. This article is based on a qualitatively driven mixed-method case design, and the data come from interviews with and observations of 10 teachers, as well as a survey conducted at 16 schools in Western Norway. The findings show that many teachers struggle to find a balance between emotional support and asking exploratory questions about their schools' and their colleagues' practices. At the same time, it seems that schools that systematically ask each other critical questions have cultures that are more strongly characterized by a high degree of psychological safety and high professional standards.

Introduction

Inclusive education in the context of challenging behavior is one of the most demanding challenges for teachers (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002; de Boer et al., 2011; Buttner et al., 2015; Øen and Krumsvik, 2022; Lindner et al., 2023). When inclusive practice is understood as a ‘multi-faceted concept’ (Mitchell, 2015; Haug, 2017), teachers are often confronted with dilemmas, requiring them to balance what can be perceived as conflicting expectations and values (Ainscow et al., 2006). Typical dilemmas are academic development versus social development and consideration of the individual student versus the class community (Gidlund, 2018). When teachers encounter challenging behavior, these dilemmas are expressed even more clearly. Teachers are under cross-pressure, and their stress levels may increase when they fear for their own safety or that of their pupils (Øen et al., 2023). Griffin and Shevlin (2007) emphasize the importance of awareness that teachers are as vulnerable as students regarding the loss of self-confidence if they experience a persistent feeling of lack of mastery, and teachers’ self-efficacy has a great influence on their attitudes toward inclusion (Hosford and O'Sullivan, 2016; Hind et al., 2019). The risk of burnout also seems to increase in the face of challenging behavior (Scanlon and Barnes-Holmes, 2013; Øen et al., 2023).

Good support for teachers helps them gain confidence in the fact that they can succeed in developing an inclusive practice (Hind et al., 2019; Desombre et al., 2021; Lindner et al., 2023). Such support can come in the form of emotional support, internal or external guidance, courses or discussions. Krischler and Pit-ten Cate (2019) warn against professional development based on a ‘traditional’ approach to inclusion. Mhairi et al. (2021) claim that a traditional difficulty-oriented approach to inclusion can result in the development of a belief that realizing an inclusive practice requires specialist competence. This can cause teachers to outsource their responsibility toward individual students to experts (Orsati and Causton-Theoharis, 2013; Razer and Friedman, 2013; Scanlon and Barnes-Holmes, 2013; Barker and Mills, 2018). As an alternative, Krischler and Pit-ten Cate (2019) therefore suggest providing professional support in which teachers take part in critical discussions that challenge traditional educational thinking and practice. Mhairi et al. (2021) highlight collaborative learning in the professional community as a key to the development of an inclusive practice, as it requires teachers to make their own practice more transparent so that it can be explained, explored and challenged. Ainscow (2020, p.10) argues that such processes and discussions can ‘create space for rethinking by interrupting existing discourses’. This idea is supported by Razer and Friedman (2013), who note that teachers must develop an approach to students with challenging behavior that goes beyond the boundaries of traditional pedagogy. However, a professional community in which teachers constructively explore and challenge each other’s practices appears to be demanding (Razer and Friedman, 2013). It is therefore crucial to develop a culture in the professional community where teachers’ negative feelings, frustrations and dilemmas can be openly expressed and discussed. The objective of this study is to gain a deeper understanding of the extent to which the professional community in schools fosters a culture of exploring and challenging existing practices. The research question of this article is, therefore, the following:

‘How can the professional community contribute to the development of a more inclusive practice related to challenging behavior?’

In referring to the professional community, the research question relies on Lave and Wenger’s (1991) concept of communities of practice (CoP). CoP can be defined as ‘groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly’ (Wenger, 2011, p. 1). The professional community in this article comprises the entire staff of a school, as well as the school’s external support network, including organizations that engage in regular and systematic collaboration with the school, such as the Educational and Psychological Counseling Service (EPS).

Learning in the professional community

In situations where people experience anxiety or fear, they usually react with automated action patterns (Hogarth and Makridakis, 1981; Wickens, 2002; Phillips-Wren and Adya, 2020). The learning potential is great in such situations (Lewin, 1951), but it often remains untapped. In critical situations, people tend to hold back with regard to our established patterns of interpretation, preventing people from taking new perspectives (Kaempf et al., 1996). New perspectives can be threatening, and people often end up looking for interpretations of the situations that coincide with the mental models they have always relied on. This does not mean that learning does not occur, but rather that it is limited to what Senge et al. (2005) call ‘reactive learning,’ where people improve on established practice. Reactive learning, therefore, has clear parallels with ‘single-loop learning’ (Argyris and Schön, 1974, 1978). This means that one learns new actions, but such actions are based on the same assessment of the situation and the same perception of reality as before. Such learning forms an important part of teachers’ professional development and is important for the development of successful practice. However, when one repeatedly finds that practice does not work, reactive learning will fall short, and new approaches will be necessary. To be able to construct new interpretations of the situation, it is necessary to challenge the existing perception of reality and reflect on which personal theories lie behind one’s choices of action. Such processes can contribute to what Argyris and Schön (1974) call ‘double-loop learning,’ which involves ‘deeper learning’ (Senge et al., 2005).

Robinson (2018) talks about the importance of engaging teachers’ theories of actions, since these are the underlying personal theories that drive their actions at both the individual and organizational levels. Fish and Coles (1998) illustrate this using the iceberg metaphor, where practice is the part of the iceberg that is visible and lies above the surface. Beneath the surface are the drivers of practice, which include a teacher’s theoretical knowledge, experiences, values, and perception of reality. In addition, the more collective values and perceptions of reality that make up a school’s organizational culture will also be strong drivers of practice. Innovative work requires ‘deeper learning’ (Senge et al., 2005), which specifically explores the drivers that lie hidden beneath the surface of the water. Challenging and exploring one’s own, colleagues’, and the organization’s theories of action can be frightening (Schein, 1993), as organizational learning ‘involves the detection and correction of errors’ (Argyris and Schön, 1978, p. 2). A prerequisite for an innovative professional community is therefore a high degree of psychological safety (Edmondson and Lei, 2014), which means being able to say what you think, provide input and suggestions, share your expertise, and be yourself without fear of reprisals or other social sanctions (Edmondson, 1999). When the relationships in a group are characterized by trust and respect, the participants also become more confident that they will be given the benefit of the doubt (Kahn, 1990). Psychological safety also means that input, comments, and suggestions are valued as prerequisites for professionalism and that feedback is given in the best sense. Psychological safety is therefore not exclusively about trust and security, but also about being development-oriented (Edmondson, 2019). Psychological safety is not only a prerequisite for the innovative work required to develop inclusive practice, but also a characteristic of such practice. In the ‘Framework for Participation’ (Florian and Black-Hawkins, 2011), the concept of participation is first linked to access and the idea that learning should be accessible to everyone. This applies to all students and staff. Furthermore, participation is linked to collaboration and learning together. Here, the focus is not only on the children, but also on cooperative learning in the professional community. Third, participation is linked to achievement and the expectation that all children can make progress, learn, and develop. However, employees must also learn and develop. Lifelong learning is therefore a relevant concept for teachers (Øen and Krumsvik, 2022). Finally, participation is linked to diversity, which spotlights the acceptance and recognition of all. It is about children accepting and recognizing each other and adults accepting and recognizing all children, and, in this context, the professional community is characterized by the fact that all employees are valued regardless of their position, function, or level of education.

Methodology

Fetters et al. (2013) places case studies within an advanced framework mixed method design. In a mixed-method case design, intensive and cumulative data collection is often required over a period of time, where the qualitative and quantitative elements have equal or different degrees of dominance. In this study, the qualitative method is dominant (Hesse-Biber and Johnson, 2015). The project received approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) in October 2020, signifying its adherence to ethical guidelines.

Selection and data collection

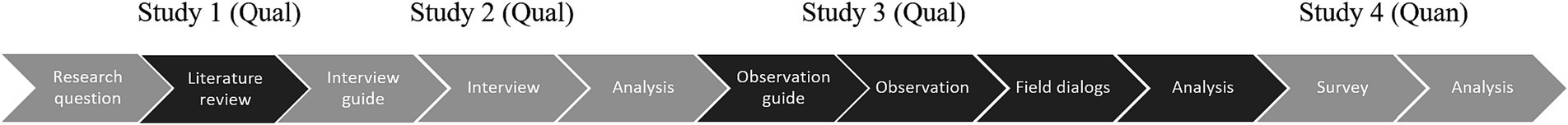

An important criterion when choosing cases is to choose the ones from which you can learn the most (Stake, 1995). In this study, two schools constitute two different cases. Both schools have pronounced visions related to inclusion and claim that they work systematically toward inclusive practice. Ten teachers make up what can be understood as the subunits of analysis. The design can therefore be described as an embedded case design (Yin, 2014). The cumulative data collection, as well as the analysis related to the cases, was carried out from May 2020 to June 2022. The relatively long time period can be seen as a strength, during which one has opportunities to test interpretations along the way and discover conflicting evidence. The data collection was based on an exploratory sequential design (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017), where a literature review (Øen and Krumsvik, 2022) and the cases’ visions formed the basis for the first phase related to the development of the interview guide. The interview guide was predominantly characterized by open-ended inquiries, facilitating a comprehensive exploration of the teachers’ experiences related to how the professional community supports the development of an inclusive practice. A few illustrations of such questions are delineated hereafter:

• Have you ever received guidance from outside supporters because of challenging behavior in the classroom?

• Who in the professional community do you experience the most relevant support from?

• What characterizes relevant support for you?

• Can you describe one or more concrete examples where you really felt that you received good support for the development of a more inclusive practice?

Following an analysis of the conducted interviews, an observation guide, influenced by Merriam and Tisdell (2016), was formulated, aiming to capture detailed and elaborate descriptions. Consequently, the observation guide primarily comprised of concise bullet points intended to guide observers in refining their observations. Illustrations of such bullet points are Confirmation, Debriefing, Exhaustion, Balancing between support and challenge, Tips, Reflective conversations and Focus on problems versus focus on solutions.

The collected interviews and observations served as the fundamental basis for conducting a qualitative analysis, which subsequently informed the construction of the survey items. Incorporating a quantitative component in the study serves to enhance the validity of qualitative findings for a broader population and to systematically examine the theoretical ideas generated from the qualitative investigation (Hesse-Biber and Johnson, 2015, p. 8). Additionally, it presents an opportunity to delve further into the outcomes obtained through the qualitative analysis. The survey items, or questions, were primarily derived from the qualitative analysis. In this process, input from relevant theory and previous research was also considered. To illustrate, the survey drew inspiration from a comparable study conducted by Mjøs and Øen (2022), which similarly examined teachers’ perceptions of reality and their comprehension of the concept of inclusion. Once the survey was developed, it underwent initial quality assurance within the research environment, with input from colleagues. Subsequently, it was piloted in three schools, a crucial step akin to a “dress rehearsal” that helps identify and address potential issues and instill confidence (Wright, 2003, p. 21). The aim of piloting is to identify weaknesses, reduce the burden on respondents, ensure the questions are comprehensible, and assess if the question order influences responses (Ruel et al., 2016). Through piloting, weaknesses in the survey were identified and addressed before its final implementation.

A ‘mixed-method’ design requires at least one ‘integration point,’ where the qualitative and quantitative components are brought together (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017). Although Figure 1 may give the impression of a sequential linear process, it is important to emphasize that the design is based on a hermeneutic approach, where later sequences shed light on the earlier analysis. The point of integration therefore already starts with the research question (Fetters et al., 2013).

Data collection and analysis strategy

The Mixed Method data analysis refers to the point of integration where the researcher combines qualitative and quantitative analysis techniques within a single study (Johnson and Christensen, 2017). This approach is supported in this article; however, there is still a need for clarification. Morse and Niehaus (2009) refer “the results point of integration,” which involves separate analyses of the qualitative and quantitative data, while incorporating both analyses in the results. This is also the most common form of integration (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017), and it is the approach followed in this article. Thus, the results section of this article is built upon the themes derived from the qualitative analysis, which is further deepened and complemented by results from the quantitative analysis.

Qualitative data

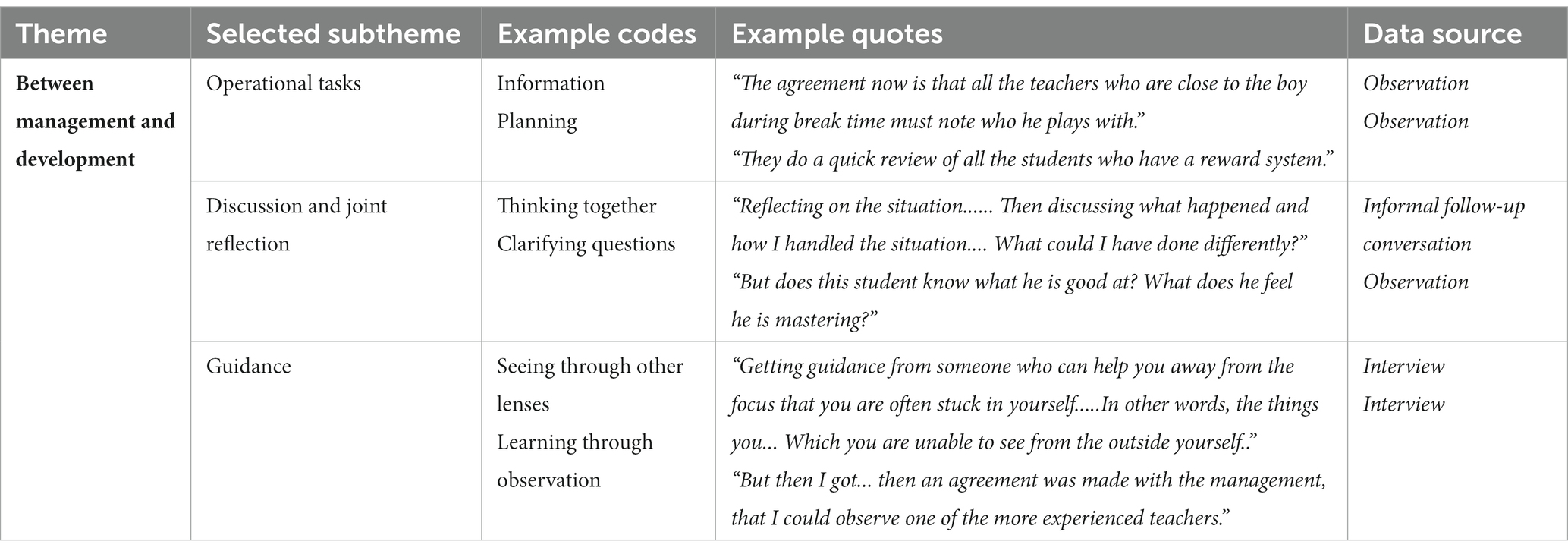

The qualitative data are based on interviews with, as well as observations of, 10 teachers (5 at each school). Of the 10 teachers who participated in the qualitative part of the study, 8 were women. To protect the anonymity of the participants, we therefore write ‘she’ when referring to the teachers. The teachers were observed in classroom situations as well as in collaborative situations in the professional community outside the classroom. Recruitment was carried out by the researcher informing the entire staff at the two schools about the study, and the criterion for participation was that the teachers themselves had subjectively experienced challenging behavior in their classrooms. The first five teachers who signed up at each school were selected to take part. The interviews were conducted on an individual basis, were carried out in autumn 2020 and winter 2022, and lasted 55 min on average. After conducting the interviews, the NVivo analysis tool was used for open coding. As mentioned, the analysis formed the basis for an observation guide, which also provided a template for field notes that provided ‘rich descriptions’ (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). After the classroom observations, we tried to carry out ‘field dialogs’ (Fossåskaret et al., 2006) with the teachers. As the teachers sometimes had to run off to other lessons or deal with ongoing conflicts, the field dialogs were sometimes difficult to carry out. The dialogs were important as the teachers had the opportunity to share both their reflections and experiences related to the choices they made concerning their teaching. In total, 73 teaching sessions of varying length (70.5 h) were observed, as well as 13 h of observation of the teachers working in collaboration with colleagues, management, and the schools’ external supporters. The researcher played the role of participant observer (Gold, 1958), and immediately withdrew after each observation to finish writing up the observation notes. In this way, all the previous observation notes were printed before the researcher took part in new observations. The idea behind this strategy is that the different observations are kept separate (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). The exploratory sequential design invited to the carry out an inductive thematic analysis of the qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006), which results in a freer and richer description of the data material. The coding was then grouped, and the themes were developed through an interactive process, which is illustrated in Table 1.

Through the analysis process, four themes were developed, which will be elaborated in the results section below. These are between management and development, trust and closeness to practice, the team around teachers, and the art of balancing.

Quantitative data

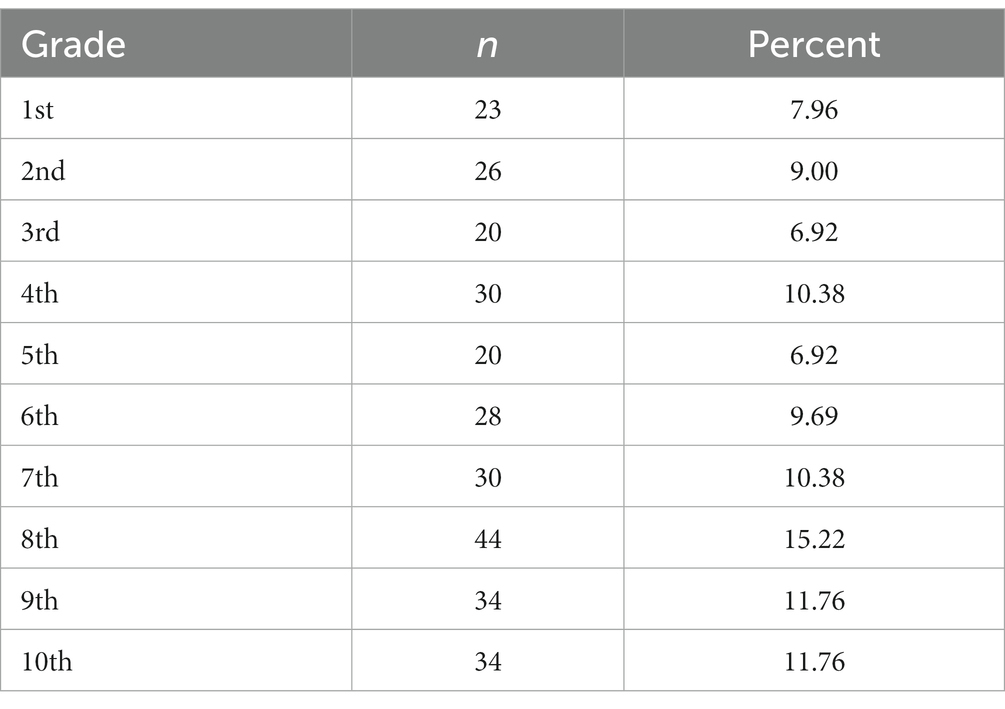

The survey was conducted in the spring of 2022 in which a total of 293 teachers participated (N = 293). The survey was carried out at 16 schools in Western Norway, spread over a total of 8 different municipalities, and had a response rate of 67%. The response rate must also be seen in light of the fact that many schools had an abnormally high level of sickness absence among teachers at this time due to COVID-19. The teachers in the qualitative part taught from the 2nd to the 10th grades. In the survey, 75.86% of the participants were women, while 24.14% were men. Concerning teaching, the survey participants are distributed relatively evenly between the 10 grade levels in Norwegian primary and lower secondary schools (Table 2).

The main variables of interest for the present study were several Likert-type scale statements, measured on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), where 3 indicated a neutral response. First, we examined the relationship between teachers’ experiences of the EPS’s understanding of and insights into their everyday lives as teachers, as well as the perceived level of guidance given by the EPS. Second, we examined the relationship between teachers’ experiences of management’s understanding of and insights into their everyday lives as teachers, as well as the perceived level of guidance and emotional support received from management. Finally, we examined the relationship between systematic peer guidance at the school level and teachers’ perceived maneuvering space concerning receiving and asking challenging questions regarding practice. The data were screened and analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2022).

Results

The subsequent section presents the results based on the identified themes, between management and development, trust and closeness to practice, the team around teachers, and the art of balancing.

Between management and development

When the teachers are asked to describe what characterizes good support for the development of inclusive practice, it seems that experienced teachers value reflective conversations to a greater extent, while newly trained teachers emphasize concrete tips and advice, as well as the opportunity to observe more experienced teachers. Most emphasize that it is the combination of tips, advice, and reflective conversations that is decisive. Through observation, it emerges that cooperation in the professional community takes many different forms. Much of the collaboration is characterized by information sharing, where one teacher informs others about conversations she has had with a child or parents or about results from screenings or tests. The information can also be linked to ‘special agreements,’ such as ‘the agreement now is that all the teachers who are close to the boy during break time must note who he plays with. This must be written in a log.’

The collaboration in the professional community was mostly characterized by professional discussion and reflection. Often the discussions were linked to concrete situations, while at other times, the discussions were on a meta level, such as when the focus was on whether the structured preparation of the students could almost have the opposite effect to what they wanted. They discussed whether certain activities, based on preparation, suddenly became a ‘big deal,’ resulting in the students becoming stressed. Everyone agreed that preparation is important, but they wondered if there could sometimes be too much of a good thing. Through such professional discussions and reflections, several clarifying, exploratory, and challenging questions were asked. Although there were several such examples, many of the questions still bore the mark of being ‘camouflaged advice,’ which often started with ‘I was just wondering if you have thought about...’ but were then followed up with direct advice, such as ‘... you should have a one-on-one conversation with the student where you explain clearly what is expected of him.’ Even though the professional communities seem to be characterized by a lot of collaboration, one can still question how systematic this is. According to the survey, a total of 76.71% of the teachers express neutrality or disagreement with regard to the claim that their schools make use of systematic peer guidance.

Trust and closeness to practice

Despite a lot of well-intentioned things being said in a professional community, a teacher may still not perceive it as being supportive. A prerequisite for being experienced constructively seems to be the teacher having confidence in the person they are discussing with or who is asking the questions. This trust is based on the ‘supporter’ having insight into the teacher’s everyday life. Such insight is about the teacher being confident that the supporter understands how demanding the teaching profession can be. Furthermore, the supportive colleague should also have knowledge of the specific students. One of the teachers said, ‘I prefer to work with those who know who the student is, who have seen the student on a bad day, and who have seen the student in a group setting.’ If their internal and external colleagues do not have these characteristics, the teachers are afraid of being misunderstood and, thereby, fear that they will be labeled as having attitudes toward students that they do not actually have. One of the teachers expressed the following in relation to one of the school’s external supporters:

I can sometimes sense that things are misunderstood or misheard... that it can be perceived that we (the teachers) do not want the best for the students or that we do not care about the students because we say things in a slightly different way. And then I think what's really the point of saying anything …

A supportive colleague must therefore make time to listen and show that they take what the teacher is saying seriously. If the teachers do not experience this, they do not dare to share the challenges they face with others. Nor do they share their understanding of the situations they are in, or the drivers behind their own practices. Without sufficient trust and closeness with regard to practice, there is a danger that well-intentioned feedback will be rejected because the supporter does not know what they are talking about, or that feedback will be perceived as criticism. This emphasizes the importance of psychological safety. In the survey, the concept of ‘psychological safety,’ based on Edmondson (1999), was defined as being able to say what you think, make suggestions, share your expertise and be yourself without fear of reprisals or other social sanctions. When the teachers in the survey were asked to what extent they experience psychological safety in their workplaces, 66.32% answered that they experience a large or very large degree of psychological safety, 28.52% claimed that there is a medium degree, while 5.16% answered that there is little or very little psychological safety in their workplaces. Having the opportunity to talk through things and ‘clear your mind’ of frustrations in the form of a ‘blowout’ are highlighted as being very important. Many of the teachers say that there is a high threshold for acceptance of this type of blowout in the team room, where they can unfetteredly say exactly what they think and feel. This seems to provide an important ‘valve.’ Still, the teachers stated that they tried to help each other onto a constructive track, where they are primarily problem solvers and not problem dwellers.

The team around the teacher

Psychological safety can be particularly challenging for school management and for external supporters when these are to have a supporting function in the professional community. With regard to whether the EPS understands and has any insight into their everyday lives, only 3.44% of the teachers completely agree with this, 19.59% somewhat agree, and the rest choose a neutral response or disagree. The same pattern is observed when the teachers are asked to assess whether they receive good guidance from the EPS when faced with challenging behavior. Here, 3.75% of the teachers completely agree, 20.14% somewhat agree, and the rest choose a neutral response or disagree with the statement. Spearman’s rho correlation analysis (rs = 0.66, p ≤ 0.001, N = 232) indicated a positive correlation between the teachers’ experiences of the EPS’s understanding of their everyday lives and the perceived guidance received from the EPS. Nevertheless, several emphasized the importance of external supporters who can contribute with an ‘outsider’ perspective that can ‘help you move away from the focus that you are often stuck on.’ One of the teachers said that she was forced into systematic collaboration with one of the external supporters. She was skeptical at the start but subsequently found it to be very helpful. She said, ‘I developed more as a teacher in those 2 years than in the 10 years before that.’

Although it can sometimes be a challenge for management to get close enough to actual practice to comprehend it, over 71% of the teachers responded that they agree that the management at their schools has an understanding of and insight into their everyday lives as teachers. Of the teachers, 70.89% also agree that they receive good emotional support from management when they are faced with challenging behavior. Also, when it comes to concrete guidance, approximately 60% of the teachers said that they receive good guidance from their managers. What is nevertheless interesting is the great variation between the teachers when they assess their internal and external support. Some see management as an important supporter, while others almost refer to management as being on the opposing team. These teachers talked about them (management) and us (the teachers). Spearman’s rho analyses indicated that the teachers’ experiences of management’s understanding and insight into their everyday lives as teachers when faced with challenging behaviors shared a strong positive correlation with perceived emotional support (rs = 0.68, p ≤ 0.001, N = 276) and guidance (rs = 0.59, p ≤ 0.001, N = 272). The same applies to the external supporters, who are highly valued by some, while other teachers considered such collaborations a waste of time. It seems that the teachers’ assessments are closely related to the experience of being heard.

You can meet people who are very interested in how you work. But you can also meet those who hardly care. They enter the classroom and observe, write a report, and then leave. What I really meant and felt... that's not what they really care about.

Most of the teachers highlighted their ‘closest colleagues’ on their teams as being their most important supporters, as these workmates have been in the same challenging situations and have felt their own ‘pulses rise.’ They have also experienced powerlessness and uncertainty, and this means that the teachers do not have to spend time explaining in detail who, what, and why things happened. Such efficiency in communication is highlighted as important as much of the collaboration takes place in more informal situations, such as during break time or lunch. When one’s closest colleagues become the most important source of support, one is dependent on finding a team that works. Some of the teachers recognized that they are part of a well-functioning team, while others, only have one other person on their team they rely on. Others do not feel part of any team at all.

The art of balancing

An awareness that dealing with challenging behavior is very demanding can be a strength, but also a weakness. In respect of how demanding it can be, the teachers are very keen to provide emotional support. An imbalance can thus arise between emotional support and constructive critical discussions and questions, where emotional support seems to dominate. Several teachers point out: ‘It’s a bit difficult. Because you must be a little careful to avoid stepping on others’. When the teachers in the survey were asked to assess the statement, ‘I often ask my colleagues challenging or exploratory questions related to their practices,’ only 18.77% said they somewhat or completely agree with this. Only just under 40% were confident that these types of questions would be perceived constructively, despite the fact that 66.32% believe there is a large or very large degree of psychological safety in the workplace. However, Spearman’s rho analyses indicated that systematic peer guidance at the school level was positively correlated with both asking (rs = 0.26, p ≤ 0.001, N = 270) and receiving (rs = 0.30, p ≤ 0.001, N = 272) challenging or exploratory questions regarding practice.

The ‘lack of boldness’ in terms of questioning colleagues’ practices also occurs when teachers see colleagues interacting with a child in a way that provokes challenging behavior. Several teachers said they are afraid of appearing ‘pretentious,’ so they do not say anything. At the same time, teachers become irritated on behalf of students, and one teacher stated:

I think some find it very easy to place all the blame on the student. And then we forget that the student's learning and behavior occurs through interactions with us. And talking to teachers who are only concerned with the student and their characteristics, they are difficult to talk to. You know very well who holds such a view about students, and you just don't talk to them.

Irritation with colleagues in combination with a ‘lack of boldness’ creates conflicts in the professional community. During the observations, management had to step in and sort things out when communication between the teachers was absent, vague, and indirect. Following a meeting with management, one of the teachers, who was accused of interacting inappropriately with a student, said to her colleagues that she values guidance, tips, advice, and clear messages. She therefore hoped that in the future things would be taken up more directly with her. Another teacher mentioned: ‘I’m not really looking for someone to pat me on the back and say: ‘It’s probably going to be fine, you are really good.’ I want concrete feedback that I can do something about.’ When the teachers were asked to give their opinions on the statement, ‘I want my colleagues to give constructive feedback if they see that I encounter challenging behavior in an inappropriate way,’ 94.5% of the teachers responded that they agree and want to receive feedback to help them change and develop their own practices. It seems that many teachers struggle to find a good balance between emotional support and constructive feedback.

Discussion

This article sought to answer the research question, “How can the professional community contribute to the development of a more inclusive practice related to challenging behavior?” Based on both qualitative and quantitative data, much of the collaboration in the professional community can be characterized as what Argyris and Schön (1974) describe as ‘single-loop learning’. Although this learning is important for teachers’ development, dealing with challenging behavior within the framework of an inclusive school requires deeper learning processes in the professional community. In their recent study, Jones et al. (2021) present evidence indicating that the dichotomy between management and development may lack relevance in the context of a dynamic work environment. They argue that the distinction, given its lack of significance, becomes blurred throughout the course of a working day. Specifically, the authors assert that engaging with challenging cases can inadvertently lead to the enhancement of a school’s practices, despite not being initially categorized as “development work.”

To create the right conditions for deeper learning, management and the external support system in particular must take seriously the fact that teachers need recognition for the challenges they experience in practice. If they do not receive recognition, even the most well-intentioned professional input risks being rejected or perceived as criticism. The art of balancing emotional support and constructive feedback seems to have a central place in the innovative development of inclusive practice, which raises the question of which competences and cultures schools possess with regard to ‘involving theories of action’ (Robinson, 2018). In a literature review, Darling-Hammond (2017) highlights that an exploratory approach to one’s own practice is a crucial factor in well-functioning education systems. Similarly, Little’s (2011) research demonstrates that strong teacher communities are characterized by teachers’ willingness to openly discuss the dilemmas they encounter in their work. These dilemmas are thoroughly examined, and the professional community actively engages in finding solutions to overcome challenges. As Senge et al. (2005) notes, there is a great deal of untapped potential in the many demanding situations that arise on a daily basis in schools. This supports Schein’s (Edmondson and Lei, 2014) assertion that free-speaking conversations in the workplace are far less common than people think. With 66.32% of teachers experiencing a large or very large degree of psychological safety in the workplace, one may wonder what the teachers really mean by psychological safety. Edmondson (2019) emphasizes that psychological safety must not be confused with being ‘nice’ and links psychological safety to high professional standards. Based on the findings of this study, it is reasonable to ask whether teachers, management and schools’ external supporters have sufficient collaborative skills to enter into demanding dialogue in a professional manner. This applies in relation to both giving critical feedback to colleagues and receiving criticism. Respect for the fact that an encounter with challenging behavior can be demanding results in fear in the professional community of being perceived as unsupportive. Thus, a culture develops in which emotional support seems to dominate, with the result being that teachers become stuck in their comfort zones. The results also show that teachers may have such low expectations regarding their colleagues’ development that they give up on them. This is deeply ethically questionable with regard to colleagues’ students and is a poor starting point for the development of inclusive practice. In Norway, teachers are obligated to adhere to the principles outlined in the Professional ethics for the teaching profession (Utdanningsforbundet, 2012). These principles emphasize that the teachers must meet criticism with openness and well-founded professional arguments. They shall initiate ethical reflection and dialogue with all employees at the workplace, works in a culture of openness and facilitates transparency and respects the competence of other professions and acknowledges the limits of one’s own discipline. The findings of this study suggest that many professional communities may not fully embody these principles as described in the Professional ethics for the teaching profession.

The need to develop a professional community characterized by a high degree of psychological safety and by high professional standards must be highlighted in the work of inclusion. Teachers want to do more for their students (Øen and Krumsvik, 2022), but they experience frustration and powerlessness in the face of complexity (Mhairi et al., 2021). Without help to explore and reflect on their own practice, teachers become stuck in established explanatory models that can stand as obstacles in the process of developing a more inclusive practice. The development of inclusive practice requires changing people’s ways of thinking. It requires teachers to continuously develop new ways of working and to be willing to work creatively with and through others (Florian, 2014). It is important to emphasize that collaboration is a skill and therefore requires practice. The findings indicate that schools that practice some form of structured peer guidance seem to have a better framework for challenging and exploring practice safely and constructively.

One must therefore not become complacent and assume that collaboration is a natural part of being a teacher. Working together and practicing working together are two very different tasks. At one of the schools, several collaborative meetings in the professional community began with the statement, ‘remember that we love each other’. This might seem superficial, but it can nevertheless be perceived as a reminder that all critical and challenging questions are well-intentioned. This opening comment, therefore, primarily testifies to an awareness that training is necessary to develop a professional community that balances emotional support and the critical exploration of teachers’ own practice.

Conclusion

The study presented in this article aims to deepen our understanding of how the professional community within a school can foster the development of inclusive practices in the context of challenging behavior. The findings of this study highlight the significance of a supportive culture among teachers in their demanding daily routines, while also encouraging the exploration and questioning of existing practices. Striking a delicate balance, however, proves demanding, as many teachers hesitate to provide well-intentioned constructive feedback to their colleagues due to a fear of being perceived as critical. Thus, the professional community must exhibit qualities such as courage, ethical awareness, and professionalism, encouraging open dialogue and inviting exploratory and challenging discussions and reflections. Without such discussions, learners are deprived of valuable learning opportunities due to the uncertainties prevailing within the professional community. Therefore, fostering a high level of psychological safety within the professional community is pivotal for establishing a, innovative, and progressive environment that encourages exploration and challenges to improve practice.

Limitations and implications

The quantitative and qualitative data shows no clear unambiguous connections related to the fact that the quantitative data exclusively confirmed the picture that the qualitative findings had formed. The various data bring out important nuances and, thereby, are primarily complementary. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that the number of participants in the survey (N = 293) makes it difficult to draw generalized conclusions. Thus, this study is simply a single piece that can contribute to a larger jigsaw puzzle.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KØ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. RK: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. ØS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is part of the SUKIP project which is led by NLA university college. The SUKIP project is in turn funded by the Research Council of Norway (Project number 296636).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: lessons from international experiences. Nordic J. Stud. Educ. Policy 6, 7–16. doi: 10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., and Dyson, A. (2006). Improving schools, developing inclusion. London: Routledge.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Avramidis, E., and Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers' attitudes towards integration/inclusion: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 17, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/08856250210129056

Barker, B., and Mills, C. (2018). The psy-disciplines go to school: psychiatric, psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches to inclusion in one UK primary school. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 22, 638–654. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1395087

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buttner, S., Pijl, S. J., Bijlstra, J., and van den Bosch, E. (2015). Personality traits of expert teachers of students with behavioural problems: a review and classification of the literature. Aust. Educ. Res. 42, 461–481. doi: 10.1007/s13384-015-0176-1

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from international practice? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 291–309. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

de Boer, A., Pijl, S.-J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary school teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 15, 331–353. doi: 10.1080/13603110903030089

Desombre, C., Delaval, M., and Jury, M. (2021). Influence of social support on Teachers' attitudes toward inclusive education. Front. Psychol. 12:736535. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.736535

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44, 350–383. doi: 10.2307/2666999

Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. 1st Edn. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Edmondson, A. C., and Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 1, 23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., and Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 48, 2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117

Fish, D., and Coles, C. (1998). Developing professional judgement in health care: learning through the critical appreciation of practice. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Florian, L. (2014). What counts as evidence of inclusive education? European J. Special Needs Edu. 29, 286–294. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2014.933551

Florian, L., and Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. Br. Educ. Res. J. 37, 813–828. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2010.501096

Fossåskaret, E., Fuglestad, L., and Aase, T. (2006). Metodisk feltarbeid – produksjon og tolkning av kvalitative data. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Gidlund, U. (2018). Why teachers find it difficult to include students with EBD in mainstream classes. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 22, 441–455. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1370739

Gold, R. L. (1958). Roles in sociological field observations. Soc. Forces 36, 217–223. doi: 10.2307/2573808

Griffin, S., and Shevlin, M. (2007). Responding to special educational needs: an Irish perspective. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Haug, P. (2017). Understanding inclusive education: ideals and reality. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 19, 206–217. doi: 10.1080/15017419.2016.1224778

Hesse-Biber, S. N., and Johnson, R. B. (2015). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry 1 ed.. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hind, K., Larkin, R., and Dunn, A. K. (2019). Assessing teacher opinion on the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties into mainstream school classes. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 66, 424–437. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2018.1460462

Hogarth, R. M., and Makridakis, S. (1981). The value of decision making in a complex environment: an experimental approach. Manag. Sci. 27, 93–107. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.27.1.93 (Management Science)

Hosford, S., and O'Sullivan, S. (2016). A climate for self-efficacy: the relationship between school climate and teacher efficacy for inclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 20, 604–621. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2015.1102339

Johnson, B., and Christensen, L. B. (2017). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. 6th Edn. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Jones, M.-A., Dehlin, E., Skoglund, K., and Dons, C. F. (2021). Crisis as opportunity: experiences of Norwegian school leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. North 28, 274–292. doi: 10.26203/pnqv-m135

Kaempf, G. L., Klein, G., Thordsen, M. L., and Wolf, S. (1996). Decision making in complex naval command-and-control environments. Hum. Factors 38, 220–231. doi: 10.1518/001872096779047986

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.2307/256287

Krischler, M., and Pit-ten Cate, I. M. (2019). Pre- and in-service teachers’ attitudes toward students with learning difficulties and challenging behavior [original research]. Front. Psychol. 10:327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00327

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: selected theoretical papers, vol. 1135. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Lindner, K.-T., Schwab, S., Emara, M., and Avramidis, E. (2023). Do teachers favor the inclusion of all students? A systematic review of primary schoolteachers' attitudes towards inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 38, 766–787. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2172894

Little, J. W. (2011). Professional community and professional development in the learning-centered school. In M. Kooy and K. Veenvan (Eds.), Teacher learning that matters: international perspectives 1st ed, 22–46). New York: Routledge

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. 4th Edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mhairi, C. B., Stephanie, T., Sarah, C., Rachel, L., Quinta, K., and Susanne, H. (2021). Conceptualising teacher education for inclusion: lessons for the professional learning of educators from transnational and cross-sector perspectives. Sustainability 13:2167. doi: 10.3390/su13042167

Mitchell, D. (2015). Inclusive education is a multi-faceted concept. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 5, 9–30. doi: 10.26529/cepsj.151

Mjøs, M., and Øen, K. (2022). En felles spørreundersøkelse skole-PPT som utgangspunkt for samarbeid om inkluderende praksis. Psykol. Kommunen 4

Morse, J. M., and Niehaus, L. (2009). Mixed method design: principles and procedures. 1st Edn. Walnut Creek, Calif: Routledge.

Øen, K., and Krumsvik, R. J. (2022). Teachers' attitudes to inclusion regarding challenging behaviour. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 417–431. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1885178

Øen, K., Krumsvik, R. J., and Skaar, Ø. O. (2023). Inclusion in the heat of the moment: balancing participation and mastery. Front. Educ. 8:967279. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.967279

Orsati, F. T., and Causton-Theoharis, J. (2013). Challenging control: inclusive teachers' and teaching assistants' discourse on students with challenging behaviour. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 17, 507–525. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.689016

Phillips-Wren, G., and Adya, M. (2020). Decision making under stress: the role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty. J. Decis. Syst. 29, 213–225. doi: 10.1080/12460125.2020.1768680

Razer, M., and Friedman, V. J. (2013). Non-abandonment as a foundation for inclusive school practice. Prospects 43, 361–375. doi: 10.1007/s11125-013-9278-6

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (4.2.0). Rome. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/

Ruel, E. E., Wagner, W. E., and Gillespie, B. J. (2016). The practice of survey research: theory and applications. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Scanlon, G., and Barnes-Holmes, Y. (2013). Changing attitudes: supporting teachers in effectively including students with emotional and behavioural difficulties in mainstream education. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 18, 374–395. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2013.769710

Schein, E. H. (1993). How can organizations learn faster? The challenge of entering the green room. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 34:85.

Schoonenboom, J., and Johnson, R. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 69, 107–131. doi: 10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1

Senge, P. M., Scharmer, O. C., Jaworski, J., and Flowers, B. S. (2005). Presence: Exploring profound change in people, organizations and society. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Utdanningsforbundet. (2012). Professional ethics for the teaching profession. Available at: www.utdanningsforbundet.no/globalassets/larerhverdagen/profesjonsetikk/larerprof_etiske_plattform_a4_engelsk_red-19.pdf

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of practice: a brief introduction. Available at: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/11736

Wickens, C. D. (2002). Situation awareness and workload in aviation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 11, 128–133. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00184

Wright, K. (2003). Research notes: a pilot study is invaluable as a dress rehearsal to iron out pitfalls and to develop confidence. Nurs. Stand. 17:21. doi: 10.7748/ns.17.24.21.s34

Keywords: inclusive education, psychological safety, professional community, case design, mixed method

Citation: Øen K, Krumsvik RJ and Skaar ØO (2024) Development of inclusive practice – the art of balancing emotional support and constructive feedback. Front. Educ. 9:1281334. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1281334

Edited by:

David Lansing Cameron, University of Agder, NorwayReviewed by:

Hege Knudsmoen, Oslo Metropolitan University, NorwayMuchamad Irvan, State University of Malang, Indonesia

Ediyanto, State University of Malang, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Øen, Krumsvik and Skaar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristian Øen, kristian.oen@nla.no

Kristian Øen

Kristian Øen Rune J. Krumsvik

Rune J. Krumsvik Øystein O. Skaar

Øystein O. Skaar