No child left behind, literacy challenges ahead: a focus on the Philippines

- 1School of Foreign Languages and Literature, Hunan Institute of Science and Technology, Yueyang, China

- 2Junior School, Sekolah Pelita Harapan - Kemang Village, Jakarta, Indonesia

- 3College of Education, Mindanao State University – Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography, Bongao, Philippines

The Sustainable Development Goal 4 has commenced a global mandate to provide equitable access to quality education for everyone. In the Philippines, SDG 4 inaugurates the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Policy. This brief argues that while the NCLB has ensured equal access to quality literacy education, it poses socioeconomic-based challenges, declining rate of parental involvement in their children’s schooling, overemphasis on standardized tests, and the lack of community involvement towards literacy programs. The Holistic Literacy Enhancement Program (HLEP) is proposed in this paper to help address these challenges to NCLB. HLEP presents policy implications that could assist the NCLB in more efficient and effective implementation: equitable resource allocation, parental and community engagement, and culturally and linguistically relevant assessment tools.

Introduction

In the changing face of global education, inclusiveness and equity have become fundamental in addressing key progress aspects (UNESCO, 2017). This paradigm shift sets the stage for the birth of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Policy in the Philippines. The policy, which mirrors the spirit of its international counterparts, seeks to give all children irrespective of their background and circumstances an equitable access to high-quality education. In addition, the concept of leaving no child behind crosses borders to connect with international programs promoting equitable learning opportunities (Cerna et al., 2021). Similar efforts have been born throughout the countries, and they all unite to a more inclusive and fair education. Beyond its immediate effects on Filipino youth, the NCLB extends its influence to a wide array of stakeholders, encompassing teachers, parents, and the broader community. Each of these stakeholders encounters distinct challenges and opportunities within the gamut of NCLB, with their roles and contributions being pivotal to the policy’s grand vision of fostering an inclusive and equitable educational environment (Noddings, 2017; VanGrongen and Meyers, 2019).

The NCLB Policy is based on experience in international contexts where education systems embark on similar journeys. In the United States, the NCLB Act was introduced in 2002 to ensure that all its citizens, including those with disabilities, received an education. In addition, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) “Quality Education” is a global commitment to inclusive and equity education for all (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2023; Stoneberg, 2019). This policy objective mirrors the aspirations of other countries highlighting the means through which access to quality education can be made equitable across all society members. The NCLB Policy in the Philippines is positioned in line with these international endeavors where the policy looks for an educational arena that promotes inclusivity, equity and right to education for all.

This policy brief engages in a thorough examination of the NCLB Policy in the Philippines, scrutinizing its efficacy in the complex tapestry of the nation’s diverse linguistic and cultural landscape. While a number of research have documented prevailing challenges of literacy education in the Philippines (McNamara, 2010; Bautista and Gatcho, 2022; David et al., 2022), there remains a paucity of evidence that can shed light on how the challenges could inform the implementation of a more holistic and inclusive literacy education program in the country. This paper critically examines how this policy navigates the intricate challenges of literacy education across varied socio-economic and cultural groups. By identifying the shortcomings and disparities in the current policy, the authors highlight the urgent need for a more holistic and inclusive approach to literacy development. This brief lays the groundwork for future strategies, aimed at harmonizing global educational standards with the unique needs of the Filipino educational context. The primary goal of this analysis is to set the stage for a transformative approach in literacy education in the Philippines, one that embraces cultural diversity and ensures equitable learning opportunities for every student, thereby truly leaving no child behind in the quest for comprehensive literacy.

This policy analysis is built on an ecological perspective of education to provide a more holistic view into the challenges of literacy education within the NCLB policy. The ecological theory examines the children’s system and context (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), emphasizing the need to explore how social resources underpin children’s development, which in this brief refers to literacy development. Following this theoretical perspective, literacy education is understood in this paper as inherently influenced by multiple systems, including the family, school, community and broader environments that impact children’s literacy development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006). This theoretical framework establishes the need for an analysis of the NCLB policy to uncover widespread challenges affecting various stakeholders who are key social actors in the children’s literacy development. By exploring literacy challenges of the NCLB policy from the ecological perspective, a more holistic and inclusive approach to literacy education deeply rooted in the multifaceted contextual challenges may be proposed, thereby championing quality literacy education in the Philippines.

This study explores the NCLB policy and critically analyzes its design and implementation. It aims to examine the challenges facing its system and suggest an initiative that the NCLB can adopt as a countermeasure towards the threats that its challenges pose. The initiative shall serve the NCLB policy towards a better design and implementation, leading to policy implications.

Empowerment of Philippine literacy education through no child left behind policy

The NCLB Policy in the Philippines was developed based on the country’s Department of Education’s (DepEd) commitment towards inclusive and equitable literacy education (Saro et al., 2023). The policy is supported by the “Education for All Act of 2000” (Republic Act No. 9155), and its progressive realization shows that the nation is making an effort to provide accessible quality education across all Filipino children. The policy is a response to longstanding problems that have characterized the nation. For instance, many students in marginalized communities and even remote areas have traditionally been left without appropriate access to quality education (Rad et al., 2022). The NCLB Policy emphasizes the need to provide equitable opportunities for learning, growth, and development of every child without consideration of their backgrounds. It underscores that the unique one-size-fits-all approach of traditional education could be excluding a critical demographic from ideal educational opportunities (Rebusa et al., 2022). It is this commitment to inclusivity and equity, supported by legislation that provides the basis for the policy.

In the sphere of literacy education, NCLB Policy has been instrumental in addressing longstanding challenges that the Philippines faces in achieving high literacy rate across its rich linguistic and cultural spectrum. The policy is directly concerned in ensuring that all Filipino children receive the same opportunities to learn and become literate (Maligalig et al., 2010). Hence, this policy states that literacy education that is open for all is pivotal in transforming the citizens to become functionally literate (Rebusa et al., 2022). Moreover, NCLB Policy acknowledges the importance of sustainable development. Since the policy has its eyes around the world, it acknowledges that quality literacy education is among the targets of the United Nations’ SDGs. The SDG 4 “Quality Education” highlights the concept of inclusive and equitable quality education for all. The effort offers a platform for the Philippines to contribute towards the fight against educational inequities and propagation of inclusiveness and equity in other parts of the world (Mirasol et al., 2021). Through this, the Philippines aligns itself with the international community in reaching all people for equitable quality literacy education and a sustainable world.

Literacy challenges of no child left behind policy

A close examination reveals that while NCLB has championed access to education, it also places considerable demands on teachers, mandates deeper involvement from parents, and reshapes the role of community in supporting literacy and learning (Noddings, 2017; VanGrongen and Meyers, 2019). Teachers find themselves at the frontline, balancing between standardized testing and providing holistic education, whereas parents are redefining their involvement in their children’s literacy journeys. Communities, historically a bedrock of support for literacy, are now reevaluating their role in fostering educational equity.

The conception and implementation of the NCLB Policy in the Philippines have yielded seemingly perennial problems within the aspects of literacy education, each hampering the efficiency of the policy to afford quality and non-discriminating education to its young population.

One of the disconcerting problems in the Philippine education sector is the obvious social disparity between what exists under the roofs of schools and what should be there (David et al., 2022). This divergence is more apparent in urban-wealthy schools and rural-poor localities (Bušljeta, 2013). For example, urban schools have new books and modernized infrastructure in addition to enough learning materials while the rural schools are still replete with obsolete books, old fashioned buildings, and scanty learning aids. This inequity then hinders the development of reading and writing in learners, thus worsening already existing inequalities in education (McGuinn, 2016). For instance, consider two schools in the Philippines: one located in downtown Manila and another located in a hinterland village of Mindanao. There is a very good library in the Manila school equipped with books and some modern, interactive tablets. However, there are few books in the Mindanao school’s library with antiquated facilities. While such a situation benefits some groups of students, it puts the other groups in sheer disadvantage, emphasizing the need to share the resources equally and eliminate inequalities.

There is also the concern on the declining rate of parental involvement in their children’s literacy development. The NCLB Policy’s test-centric accountability approach has inadvertently weakened the longstanding partnership between parents and schools (David et al., 2022). Research shows that parents are key players in fostering their children’s reading and writing skills, home reading orientation, and literacy-based activities leading to parental involvement (Sapungan and Sapungan, 2014). However, parents have sometimes given more importance to performance metrics than to holistic literacy development because of the policy’s focus on test outcomes. For example, instead of encouraging a well-rounded literacy education, parents might invest heavily in test preparation courses and private tutoring focused solely in improving their children’s test scores. This could lead to parents rewarding or punishing children based on their test scores rather than cultivating a love for learning. Some of the factors leading to this problem are elongated working hours, inadequate access to learning resources, and a mentality that education should be provided only by schools (Bautista and Gatcho, 2022). Lack of active parental involvement has a detrimental effect on the children’s emerging literacy development as they are deprived from essential support.

Another significant problem is concerning teachers. The NCLB policy’s relentless performance pressure on educators, typically focused on standardized achievement test scores, has led teachers to prioritize test-preparation activities over the delivery of holistic literacy instruction (McNamara, 2010). This myopic view on metrics may lead to the decreasing quality of literacy instruction and increasing teacher burnout (Jensen, 2022). In addition, it has resulted in “mass promotion” - where students are promoted to higher grade level without ensuring that they have acquired key literacy foundation skills (Orale and Uy, 2018; Bongco and David, 2020). Such a practice could negatively influence the education of students, perpetuating literacy disparity among pupils (Okurut, 2015). This situation then adversely affects the educational system in the Philippines by delimiting success in higher education and in the workplace. In the Philippines, mass promotion seems to be becoming a common practice, with many teachers joining the bandwagon and perceiving it as normal because DepEd campaigns for zero dropouts (David et al., 2019). This phenomenon is further aggravated by a formal incentive system that pressurizes schools to pass students, even if children have not acquired the necessary literacy skills to propel to the next grade level.

Finally, the implementation of the NCLB Policy challenges community’s involvement in literacy programs considering the apparent misunderstanding of the policy from the stakeholders’ end (Saniel et al., 2022). Historically, local communities have been central to education in the Philippines. For example, book clubs and literacy events in the community have influenced the development of students’ literacy (Levitt, 2017; Reister, 2020). The policy’s apparent emphasis on testing has, nevertheless, curtailed communities’ input into literacy-driven ventures (Ladd, 2017; Darling-Hammond, 2018). One can similarly notice a decline in community-led reading events and initiatives in many areas, as the latter tends to focus on the preparation for tests. Such reduced dilution of community involvement can leave students devoid of important support networks essential in the process of creating a reading and writing zeal.

These multifaceted literacy challenges reveal the profound negative impacts of the NCLB on teachers, who face increased pressure and potential burnout; parents, who struggle with decreased engagement in their children’s education; and communities, whose pivotal role in literacy support has been undermined. These consequences underscore the urgent need for tailored recommendations aimed at mitigating these effects and enhancing the policy’s effectiveness in fostering an inclusive and equitable literacy education in the Philippines.

Actionable recommendations

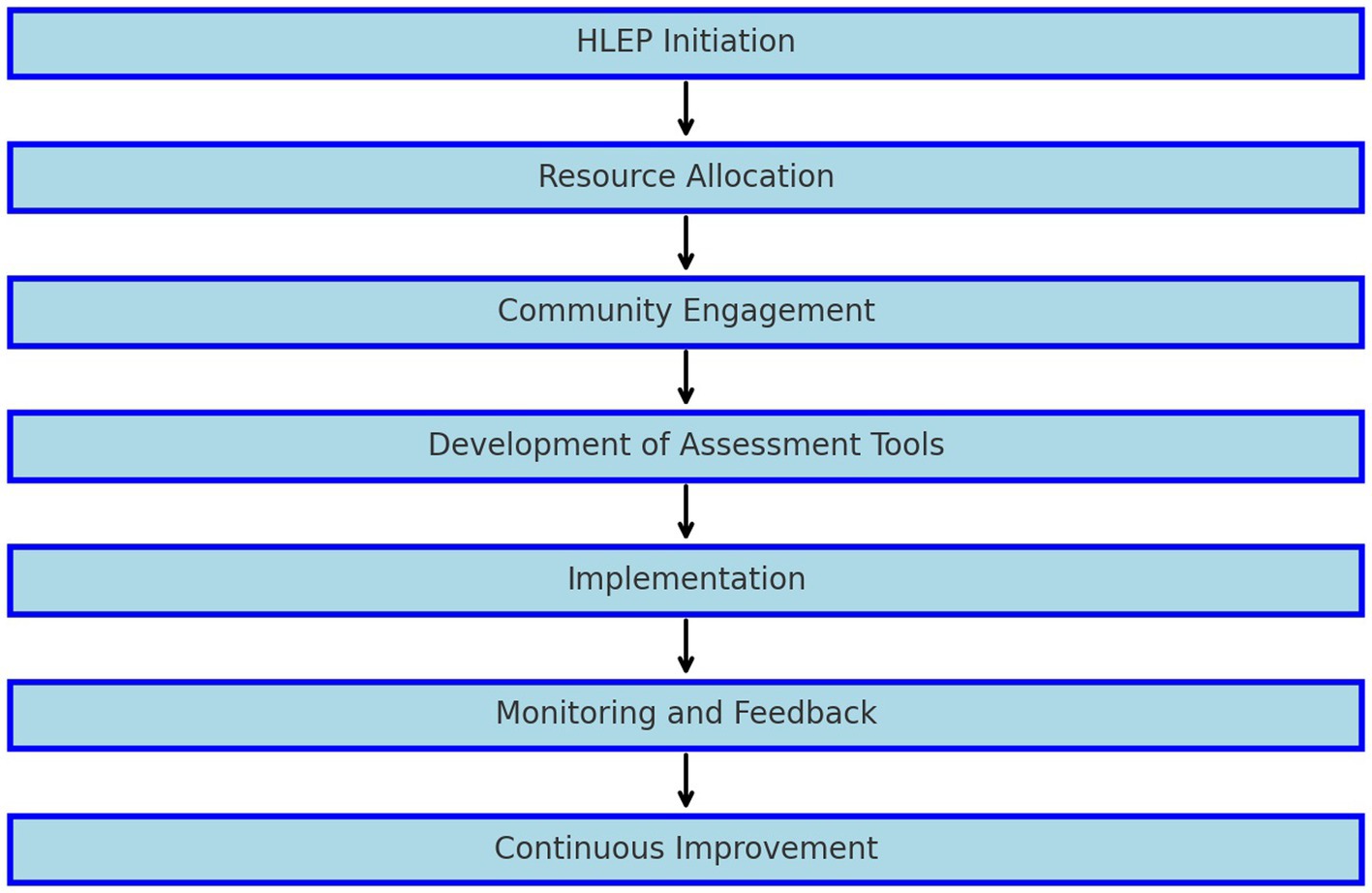

In light of the identified ecological literacy challenges brought about by NCLB Policy, the proposed countermeasure is the implementation of the Holistic Literacy Enhancement Program (HLEP). This comprehensive program is underpinned by a triad of focal points, addressing the multifaceted contextual literacy challenges that have surfaced in this brief. Firstly, it advocates for equitable allocation of educational resources, a fundamental step towards parity in learning environments (Bušljeta, 2013). Secondly, it seeks to amplify parental and community engagement in the educational discourse, recognizing their pivotal role (David et al., 2022). Lastly, HLEP embraces the necessity of culturally attuned assessments (McNamara, 2010), an essential element in honoring and addressing the diverse fabric of the student body (refer to Figure 1 for the HELP flowchart).

HLEP’s primary strategy focuses on a comprehensive plan for equitable resource distribution, especially targeting underserved schools. This initiative involves supplying current textbooks, advanced digital tools, and key infrastructure upgrades, overseen by DepEd to foster an inclusive learning environment. Concurrently, the effective local-level execution of this plan is entrusted to school administrators, who play a pivotal role in its practical implementation. The formulation of this plan is projected to span a period of 3–6 months, followed by a subsequent 6-month phase dedicated to its deployment. To rigorously evaluate the impact and efficacy of this resource allocation, a systematic assessment regimen will be instituted, involving the analysis of resource utilization reports and a thorough examination of the resultant shifts in literacy rates and academic performance among the beneficiary schools.

Furthermore, HLEP aims to actively involve parents and the community in improving literacy. Local Educational Boards and Parent-Teacher Associations (PTA) will collaborate to provide educational seminars and workshops. These endeavors aim not only to inform but also to actively involve parents in their pivotal role in supporting their children’s journey towards literacy. Additionally, the community could enjoy literacy-focused events like reading clubs and book festivals, which may start 2–4 months after initial preparations. These events will be regularly implemented in schools during the school year with continuous monitoring and evaluation. Success will be measured by looking at how many people participate and what surveys reveal.

Finally, the program emphasizes the use of culturally and linguistically relevant assessment tools in teaching literacy. For example, reading tasks for multilingual learners will be designed in a manner that addresses their linguistic and cultural needs, thus ensuring inclusivity in the materials. Working with literacy specialists, DepEd will develop and roll out these tools. At the same time, Local Educational Boards will provide teacher training focused on cultural awareness and inclusiveness in literacy and practical understanding of the operative training manual that can serve as a user guide for school administrators, teachers, stakeholders, and students relative to the use of HLEP materials. Developing and testing these tools may take 6–12 months, with teacher training expected to finish in 18–24 months. The effectiveness of these tools may be tested through trial runs, teacher input, and by observing how they affect student engagement and success, especially in underserved communities.

HLEP seeks to enhance existing policies by guiding Filipino students towards inclusive and equitable literacy education. It affects various stakeholders by redistributing resources equitably, thereby reducing teacher burdens and enabling quality education. Furthermore, it revitalizes parental and community engagement, reinforcing a collaborative educational spirit. This cohesive strategy not only aligns with the international norms but also bolsters national growth and inclusivity, making a tangible difference in the educational landscape. Nonetheless, for the sustainability of HLEP, there is a need for continuous monitoring and evaluation of its implementation to ensure its long-term desirable impacts on the stakeholders. By critically monitoring and evaluating its implementation, continuous improvement of the proposed initiative becomes attainable, thereby driving limitless success for its targeted stakeholders.

Policy implications

The challenges of and opportunities for the NCLB Policy in the Philippines have important policy implications beyond education. It is, therefore, vital to enlist efforts addressing these ecological challenges especially in increasing literacy education for an equitable and efficient education system in the country.

1. Equitable Resource Allocation: The proposal emphasizes fair distribution of educational resources – up-to-date textbooks, cutting-edge digital tools, and vital infrastructure improvements. This ties directly to the economic effects discussed in the policy’s implications. Addressing these resource gaps is essential, not only for policy compliance, but also for driving economic growth and ensuring fair opportunities for every student, a core economic goal of the policy.

2. Parental and Community Engagement: The emphasis is on strengthening the involvement of parents and the community in literacy development. This will take shape through dynamic workshops, seminars, and community events like book festivals and reading clubs. The approach extends beyond merely teaching reading and writing; it entails creating a sense of unity and connection among people. By ensuring equitable access to quality education and literacy, it is not just closing societal gaps; it is weaving a stronger social fabric, uniting people around a common national objective.

3. Culturally and Linguistically Relevant Assessment Tools: Emphasizing the use of these tools in teaching literacy, along with providing teacher training focused on cultural awareness and inclusiveness, supports the goal of global competitiveness. By equipping Filipino students with relevant skills and promoting an inclusive educational system, the policy aims to enhance the nation’s competitive stance in the global environment, as highlighted in the policy implications.

Conclusion

The journey explored in this brief, centering on the Philippines’ NCLB Policy, reveals a bold step towards reshaping literacy education. The policy, ambitious in its scope, may now face the critical test of effective implementation, especially with the introduction of the HLEP. Looking ahead, the evolving landscape of educational needs and ecological shifts will be the true yardstick of NCLB’s efficacy. Future research should keep a close eye on these developments, providing insights crucial for fine-tuning the policy. Educators, policymakers and the wider community, working together, are key social actors in propelling the success of this process. It is in their hands that the NCLB Policy will evolve from an idealistic vision into a tangible force for educational change, creating a learning environment where every Filipino child can not only learn but thrive.

Author contributions

AG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JM: Writing – review & editing. BH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bautista, J. C., and Gatcho, A. R. G. (2022). “Double dearth effect: disruptions to resources, access, and literacy practices” in Poverty impacts on literacy education. eds. J. Tussey and L. Haas (Hershey, PA: IGI Global).

Bongco, R. T., and David, A. P. (2020). Filipino teachers’ experiences as curriculum policy implementers in the evolving K to 12 landscape. Issues Educ. Res. 30, 19–34. doi: 10.3316/informit.085730319385430

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2006). “The bioecological model of human development” in Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. eds. R. M. Lerner and W. Damon (Ontario, Canada: John Wiley & Sons Inc.).

Bušljeta, R. (2013). Effective use of teaching and learning resources. Czech-polish Histor. Pedag. J. 5, 55–69. doi: 10.2478/cphpj-2013-0014

Cerna, L., Mezzanotte, C., Rutigliano, A., Brussino, O., Santiago, P., Borgonovi, F., et al. (2021). ‘Promoting inclusive education for diverse societies: a conceptual framework.’ OECD education working papers, no. 260, OECD publishing, Paris, no. 260.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2018) ‘From “separate but equal” to no child left behind’. Thinking about schools: a foundations of education reader (2018).

David, C. C., Albert, J. R. G., and Vizmanos, J. F. V. (2019). ‘Pressures on public school teachers and implications on quality.’ Policy Notes no. 2019-2001. Available at: https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidspn1901.pdf (Accessed September 29, 2023).

David, H. T., Mariano, M. A., Ramos, C. S., Taay, J. A. M. L., Valenzuela, M. L. Y., and Dangagan, C. G. (2022). Exemplifying the implementation of the “no child left behind policy” on the elementary schools. Int. J. Acad. Multidisc. Res.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2023).‘The 17 Goals | Sustainable Development.’ Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (Accessed September 29, 2023).

Jensen, M. T. (2022). Are test-based policies in the schools associated with burnout and bullying? A study of direct and indirect associations with pupil-teacher ratio as a moderator. Teach. Teach. Educ. 113:103670. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103670

Ladd, H. F. (2017). No child left behind: A deeply flawed federal policy. J. Policy Anal. Manage. 36, 461–469. doi: 10.1002/pam.21978

Levitt, R. (2017). Teachers left behind by common Core and no child left behind. In Forum on public policy online Oxford Round Table. West Florida Avenue, Urbana, IL.

Maligalig, D. S., Caoli-Rodriguez, R. B, Martinez, A., and Cuevas, S. (2010) ‘Education outcomes in the Philippines.’ Asian Development Bank economics working paper series no. 199.

McGuinn, P. (2016). From no child left behind to the every student succeds act: federalism and the education legacy of the Obama administration. Publius J. Federal. 46, 392–415. doi: 10.1093/publius/pjw014

McNamara, M. (2010). ‘Exploring the impact of standardised assessment in the primary school classroom.’ Master of Education Thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway. Available at: https://www.dcu.ie/sites/default/files/carpe/Mc%20Namara%20(2010).pdf (Accessed October 7, 2023).

Mirasol, J. M., Necosia, J. V. B., Bicar, B. B., and Garcia, H. P. (2021). Statutory policy analysis on access to Philippine quality basic education. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2:100093. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100093

Okurut, J. M. (2015). Examining the effect of automatic promotion on Students' learning achievements in Uganda's primary education. World J. Educ. 5, 85–100. doi: 10.5430/wje.v5n5p85

Orale, R. L., and Uy, M. E. A. (2018). When the spiral is broken: problem analysis in the implementation of spiral progression approach in teaching mathematics. J. Acad. Res. 3, 14–24.

Rad, D., Redes, A., Roman, A., Ignat, S., Lile, R., Demeter, E., et al. (2022). Pathways to inclusive and equitable quality early childhood education for achieving SDG4 goal—A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 13:955833. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.955833

Rebusa, A., Refogio, L., and San Jose, A. (2022). Looking at the no child left behind policy: the implementers’ perspectives. Sociol. Int. J. 6, 251–254. doi: 10.15406/sij.2022.06.00295

Reister, A. (2020). ‘Influence of book clubs on reading motivation for third through fifth grade students.’ Graduate Research Papers. University of Northern Iowa. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/1492 (Accessed October 5, 2023).

Saniel, D., Parcutilo, J., and Mariquit, T. (2022). Educational policy analysis: policy formulation and implementation of the five statutory policies in the Philippine basic education. Sci. Int. 34, 1–8.

Sapungan, G. M., and Sapungan, R. M. (2014). Parental involvement in child’s education: importance, barriers and benefits. Asian J. Manag. Sci. Educ. 3, 42–48.

Saro, J., Bello, J., Concon, L., Polache, M., Ayaton, M., Manlicayan, R., et al. (2023). Contextualized and localized science teaching and learning materials and its characteristics to improve Students' learning performance. Pscyhol. Educ. 7, 77–84. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7607686

Stoneberg, B. D. (2019). Using NAEP to confirm state test results in the no child left behind act. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 12:5.

Keywords: educational equity, educational reforms, inclusive education, literacy education, no child left behind (NCLB)

Citation: Gatcho ARG, Manuel JPG and Hajan BH (2024) No child left behind, literacy challenges ahead: a focus on the Philippines. Front. Educ. 9:1349307. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1349307

Edited by:

Raúl Ruiz Cecilia, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Tantri Yanuar Rahmat Syah, Universitas Esa Unggul, IndonesiaManuel J Cardoso-Pulido, University of Granada, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Gatcho, Manuel and Hajan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Al Ryanne Gabonada Gatcho, 42023001@hnist.edu.cn

Al Ryanne Gabonada Gatcho

Al Ryanne Gabonada Gatcho Jeremiah Paul Giron Manuel

Jeremiah Paul Giron Manuel Bonjovi Hassan Hajan

Bonjovi Hassan Hajan