Interventions to improve the quality of maternal care in Ethiopia: a scoping review

- 1College of Health Sciences, Debre Tabor University, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia

- 2School of Public Health, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3School of Public Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 4Menzies School of Health Research, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT, Australia

- 5College of Health Sciences, Wolaita Sodo University, Wolaita, Ethiopia

- 6College of Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Introduction: Quality improvement interventions have been part of the national agenda aimed at reducing maternal and neonatal morbidities and mortality. Despite different interventions, neonatal mortality and morbidity rates remain steady. This review aimed to map and synthesize the evidence of maternal and newborn quality improvement interventions in Ethiopia.

Methods: A scoping review was reported based on the reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis extensions for the scoping review checklist. Data extraction, collation, and organization were based on the Joanna Briggs Institute manual of the evidence synthesis framework for a scoping review. The maternal and neonatal care standards from the World Health Organization and the Donabedian quality of health framework were used to summarize the findings.

Results: Nineteen articles were included in this scoping review. The review found that the studies were conducted across various regions of Ethiopia, with the majority published after 2013. The reviewed studies mainly focused on three maternal care quality interventions: mobile and electronic health (eHealth), quality improvement standards, and human resource mobilization. Moreover, the reviewed studies explored various approaches to quality improvement, such as providing training to healthcare workers, health extension workers, traditional birth attendants, the community health development army, and mothers and supplying resources needed for maternal and newborn care.

Conclusion: In conclusion, quality improvement strategies encompass community involvement, health education, mHealth, data-driven approaches, and health system strengthening. Future research should focus on the impact of physical environment, culture, sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and long-term effects of interventions. Healthcare providers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, satisfaction, and adherence to guidelines should also be considered.

Introduction

Every day, pregnancy- and childbirth-related complications lead to the deaths of almost 800 women and 6,700 neonates globally. Moreover, approximately 5,400 stillbirths occur daily, with 40% of these fatalities occur during labor and delivery (1). Sub-Saharan African countries have recorded 546 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, whereas developed regions have recorded only 12 deaths per 100,000 live births. Almost 94% of maternal deaths are associated with inadequate maternal care (2, 3). Ethiopia is a sub-Saharan African country that experiences a significant burden of neonatal mortality, with 30 deaths per 1,000 live births (4). It is crucial to prioritize quality maternal care to enhance the survival rates of both mothers and newborns (5).

Quality maternal and newborn care has been prioritized to catalyze action and support of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG-3) global target of a maternal mortality ratio of less than 70 (5, 6). Almost half of the maternal population and more than 60% of neonatal deaths arise from poor quality care (7). Increasing access to healthcare services is needed to improve maternal and neonatal health (8); however, the paramount importance lies in quality of care.

The quality of care in the healthcare system is described from the perspective of healthcare providers, managers, and patients using elements such as safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, equity, and the provision of care (9). Improving the utilization of evidence-based guidelines through quality improvement initiatives proves effective, but implementing and maintaining them can be challenging (10).

Ensuring high-quality care is essential to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) established a quality of care (QoC) strategy for improving care for pregnant women and newborns. The strategy focuses on three areas of intervention to improve the quality of clinical care: enhancing the care experience and creating an enabling environment and system for quality care (11, 12), aligned with the strategies of ending preventable death and the Every Newborn Action Plan (13, 14). The quality of care could be affected by different factors, including a shortage of human resources (15); social, political, economic, and health system factors (16, 17); the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of healthcare providers; physical infrastructure; supply; leadership; provider's client relationship (18); mistreatment; and lack of support (19). Interventions were categorized based on the three systems of Donabedian's model of healthcare quality (input, process, and output) and the eight domains outlined in the WHO standard of care framework (20). The WHO recommends a comprehensive intervention strategy to make pregnancy safer: capacity development, increasing awareness, strengthening linkage, and improving the quality of services (21). In addition, interventions aimed at promoting health, such as enhancing the health of mothers and newborns, improving care provided at home, increasing community support for maternal health, increasing access to and use of skilled professionals, and empowering women, all work together to improve the quality of maternity care (22).

Evidence suggests that culturally appropriate maternity care interventions, such as home visits, formation of community-based health support groups, financial and community-based intervention packages, promoting awareness of women's rights, and educational training, improve the quality of maternal and newborn care (23–26). Moreover, improving the quality of midwifery education to meet international standards positively impacts the quality of maternity care (7). Interventions can be categorized as setting standards; implementing quality improvement programs; establishing performance-based initiatives (financial and non-financial); engaging and empowering clients; changing the clinical practices of healthcare workers; providing information and education to healthcare workers, managers, and policymakers; and implementing legislation and regulations for healthcare delivery (27).

In Ethiopia, the quality of maternity care became one of the areas of focus in 2014 and one of the four pillars of the Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP) II (2020–2025), which aimed at reducing maternal mortality to 279 per 100,000 live births, neonatal mortality to 21 per 1,000 live births, increasing skill delivery to 76%, and achieving antenatal care (ANC) coverage of 81% (28), which could be addressed through quality care interventions. Overall, quality improvement is observed throughout the continuum of care and improved emergency services (29, 30). Despite different maternal care quality improvement interventions in Ethiopia, maternal morbidity, adverse birth outcomes, and neonatal mortality rates remain steady. To the best of our knowledge, a scoping review targeting quality improvement interventions has not been conducted. As such, this review aims to identify, map, summarize, and inform priority research questions related to quality care interventions aimed at improving maternal and neonatal health in Ethiopia.

Methods

Identifying the research questions

The protocol was drafted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and has been registered on Figshare (31). A scoping review was used because of the broader nature (32) of quality maternal and neonatal care interventions. The review was based on Arksey and O’Malley's scoping review framework (33) and expanded to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework for methodology consideration (34). We followed five essential steps of the Arksey and O'Malley methods in the review process. First, we identified the research questions. Second, we identified relevant studies. Third, we chose which studies to include. Fourth, we organized and recorded the data. Finally, the results were summarized and reported (35). The preferred reporting item checklist and explanation used for reporting are given in Supplementary File S1 (36).

BB and YA developed the research questions. The population, concept, and context frameworks were used to establish the eligibility of the research questions. The population included women/healthcare facilities, and the concept focused an intervention related to quality care within the Ethiopian context.

Inclusion criteria

We included publications focusing on quality interventions (QI) to improve maternal and neonatal health in Ethiopia. All maternal and neonatal QI studies published in English were included. Papers with a study design, interrupted time series studies, before-and-after studies, program evaluations, randomized control trials (RCT), quasi-experimental designs, comparative cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, qualitative studies, and reports were included. Articles without full text or data that were challenging to extract were excluded.

Search strategy

We thoroughly searched various bibliographic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library, and performed manual search for unpublished sources to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature. Medical subject headings, keywords, and free-text search terms were used. An extensive and comprehensive search was performed from the PubMed database using alternatives (all field options) (Supplementary File S2). A literature search was conducted between March 20 and June 4, 2022.

Evidence screening and selection

First, a systematic search was conducted in all identified/accessed databases, search engines, and unpublished articles. Second, all retrieved studies were exported to Endnote version 7 (Thomson Reuters, London) reference manager, and duplicated studies were removed. Third, unrelated articles were excluded from the title review. Two investigators (BB and DB) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts to determine the eligibility of each study. During the review process, articles lacking full text were identified through discussions with the reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third party (YT).

Data extraction

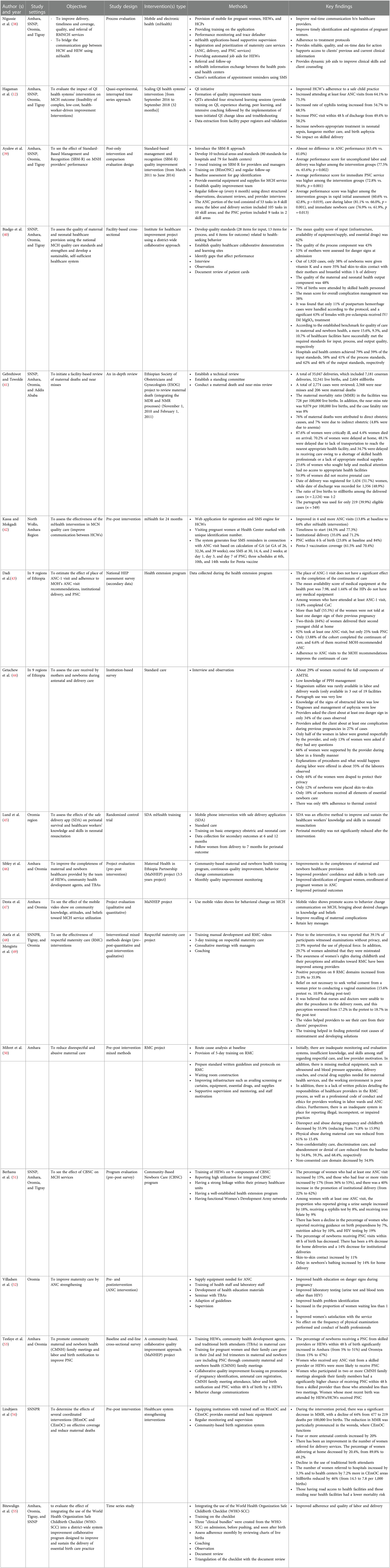

The data extraction tool was developed using the JBI manual of the evidence synthesis framework for scoping reviews (37). The extracted data were based on several tools, including author(s)/year of publication, study setting, aim/purpose, methods employed, type of intervention/comparator (duration of intervention), and key findings (Table 1).

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The scoping review findings were reported following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Data were presented using text, figures, and tables to describe the concept, population, and context. The interventions were classified into three systems based on Donabedian's model of healthcare quality (input, process, and output) and eight domains of the WHO's standard of care (56).

Results

Search results

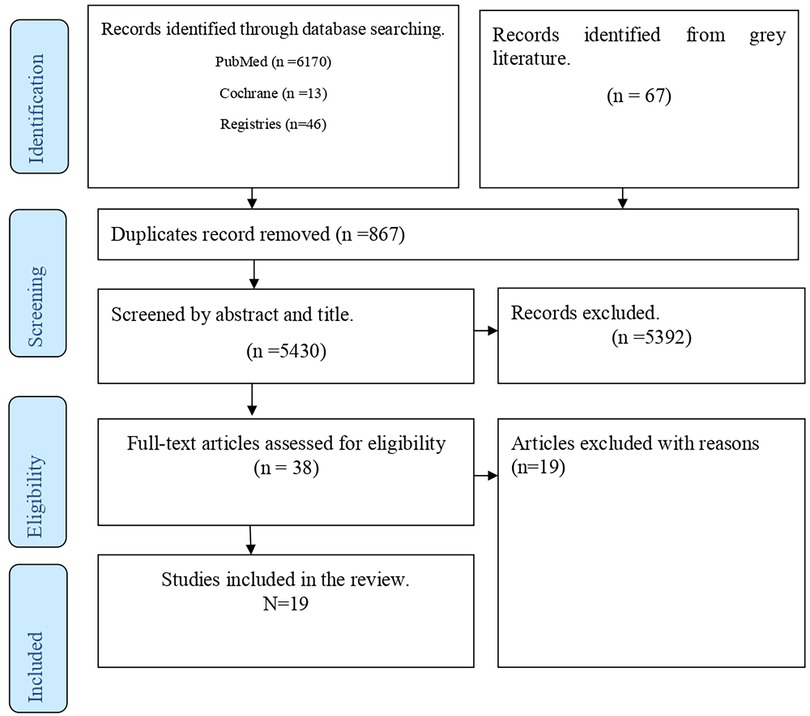

Articles were searched from PubMed (n = 6,170), Cochrane Library (n = 13), Registries (n = 46), and gray literature (n = 67), yielding a total of 6,296 articles, of which 5,430 remained after duplication removal. Following title and abstract screening, 38 articles were reviewed for full text. Finally, 19 articles were selected for inclusion in the scoping review (Figure 1).

Characteristics of included studies

Nineteen studies were included in the review. As per the review, n = 2 studies were conducted in all regions of Ethiopia; n = 6 studies were conducted in four regions of Amhara, Oromia, SNNP, and Tigray; n = 1 study was conducted in three regions of Amhara, Oromia, and SNNP; n = 2 studies were conducted in three regions of SNNP, Tigray, and Oromia; n = 3 studies were conducted in two regions of Amhara and Oromia; n = 2 studies were conducted in Oromia; n = 2 studies were conducted in Amhara; and n = 1 study was conducted in SNNPR. Almost all articles were published after 2013, and only one study was conducted in 2011. As per the current review, nine studies (12, 38–42, 46, 47) focused on maternal and child health (MCH) [ANC, intrapartum, postnatal care (PNC)] intervention, two studies (43, 49) focused on ANC intervention, three studies (41, 44, 45) focused on intrapartum, two studies (51, 52) focused on PNC, and three studies (48–50) focused on respectful maternity care.

Most studies (n = 10) were pre–post intervention (project evaluation) studies (42, 46–54), n = 1 study was a RCT (45), n = 4 studies were facility-based cross-sectional studies (40, 41, 43, 44), and n = 1 study was a (55) quasi-experimental time series.

Reports have targeted different types of interventions to improve the quality of MCH care. Based on the type of intervention, four studies focused on mobile and electronic health (eHealth) (38, 42, 45, 47), n = 5 studies focused on quality improvement standards (12, 38–40, 44), and n = 10 studies focused on human resource mobilization (training for healthcare providers, health extension workers, traditional birth attendants, and the community health development army, pregnant mothers, and supply material resources needed for MCH services) (43, 46, 48–55) (Table 1).

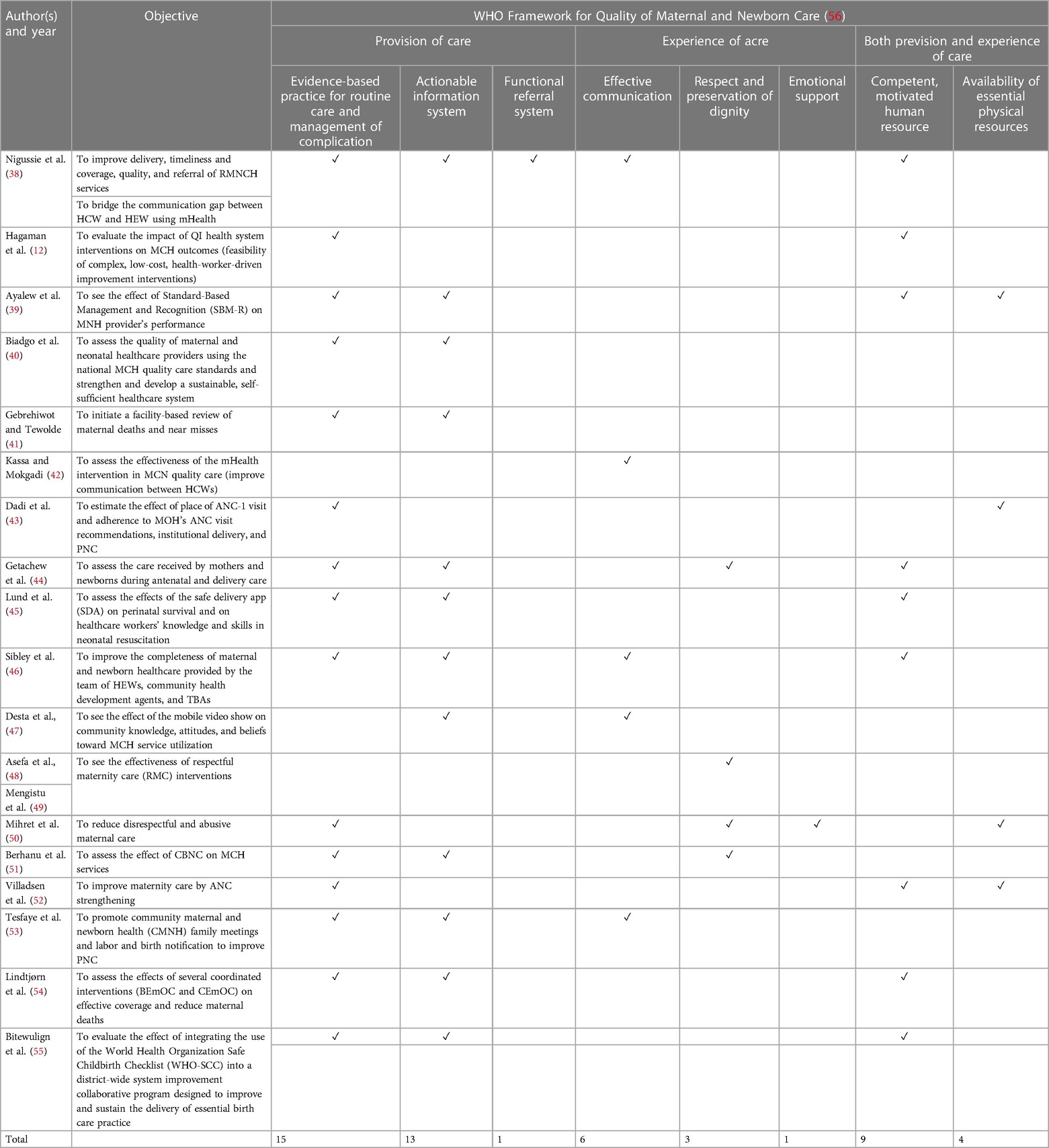

Data extraction and synthesis intervention based on WHO's eight domains of quality care

Quality improvement interventions were summarized based on the WHO eight domains of quality care for mothers and newborns: most (15) interventions focused on domain 1 (evidence-based routine care and management of complications) (12, 38–41, 43–46, 50–55), 13 reports focused on domain 2 (the health information system enables the use of data to ensure early, appropriate action to improve the care of every woman and newborn) (38–41, 44–47, 51, 53–55), 9 studies focused on domain 7 (the availability of competent and motivated staff) (12, 38, 39, 45, 46, 52–54), 4 studies focused on domain 4 (effective communication) (38, 42, 46, 47), and 4 studies addressed the medicine and equipment required for maternal and newborn care (39, 43, 50, 52). Very few studies focusing on domains 3 (38), 5 (44, 48, 50), and 6 (50) were related to the functional referral system, promotion of respectful and dignified care, and emotional support, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Alignment of quality improvement intervention with WHO’s quality of maternal and newborn care standards.

Discussion

Quality improvement of maternal and newborn care has been one of the national agenda in averting maternal and neonatal mortality. The current scoping review revealed that improving the quality of maternal and newborn care in Ethiopia is a complex and challenging task. Various sources have been identified, such as quality improvement strategies, ranging from community engagement to health system strengthening, including mHealth, community involvement, health education, standard-based practice, health workforce empowerment, and the supply of resources for MCH services. The key themes that emerged from the literature were the impact of mHealth interventions (safe delivery applications, SMS messages, and video shows), using MCH standards (WHO safe delivery checklist, quality standards, and reports), community involvement, and empowerment of healthcare providers for improving MCH care. However, a notable research gap exists regarding the impact of material resources, physical environment, and accessibility on the quality of maternal and newborn care, which needs further investigation.

The review studies suggested that the place of ANC-1 visit does not have a significant effect on the completion of the continuum of care; only 13.9% completed the continuum of care, with 6.6% of them receiving the Ministry of Health recommended ANC and only 25% attending PNC visits (7). This finding was supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia (43). Completion of the continuum of care may be influenced by factors other than the first ANC visit, such as socioeconomic status, mass media exposure, accessibility of the healthcare institution, and quality of care received during the first ANC visit (57, 58). Moreover, the flexibility of the healthcare system may influence women to seek their first ANC visit in alternative settings. Seeking care at a formal healthcare facility for an initial ANC visit can improve the likelihood of receiving timely and appropriate care throughout the continuum. Factors such as accurate risk assessment, early detection of complications, and effective referral systems are more likely to be present in formal healthcare settings (59). As such, it is essential to consider the holistic perspective encompassing multiple factors influencing the continuum of care.

The use of the Safe Childbirth Checklist (SCC) is associated with improved essential birth practice and reduced pregnancy complications, reducing the rate of severe pre-eclampsia (60, 61). According to a randomized control trial, the use of the WHO checklist had an impact on the safety culture among healthcare providers. The trial showed that healthcare providers were more likely to call attention to problems with patient care and report errors during periods of excessive workload when using the checklist (62). Evidence showed that knowledge and skills related to neonatal resuscitation deteriorate after 6 months of training (63), indicating the knowledge and skills of healthcare professionals should be emphasized greatly.

Community engagement and empowerment are also of paramount importance in improving quality care. Community involvement in decision-making processes and utilization related to MCH care helps ensure that services are responsive to their needs and preferences (64). Implementing community-oriented strategies improves skilled birth attendants (65), enhances knowledge and healthy behaviors related to MCH care (66), and reduces neonatal mortality (67). Improving maternal and child healthcare can be achieved by creating a peer support network. This approach can increase access to vital information, reduce isolation, and encourage positive health-seeking behavior (68). Community based outreach activities played a key role in identifying barriers to accessing care and improving MCH services (69). Emphasizing the involvement of the community is crucial for need assessment, community-led planning, and establishing a healthy community. Future efforts should prioritize community perspectives and involve them in culturally sensitive approaches.

The review identified technologies to improve maternal and newborn care, such as mHealth (using phone-based communication, SMS messaging, and mobile applications) to deliver healthcare services and information (38, 42, 45, 47). Studies also showed that SMS-based intervention could improve antenatal attendance, immunization rates, and mother's knowledge of MCH (70). SMS messages to pregnant women and new mothers can serve as reminders for assessing MCH services. Using mobile phone-based health behavior interventions in pregnancy improves behaviors, positive beliefs, and health outcomes (71, 72). Mobile health applications have proven beneficial for providers in making informed decisions while delivering care, collecting data, and providing health education (73, 74). Moreover, using voice counseling, job aid applications, direct messaging, and interactive media as a means of behavioral change communication had a significant impact on improving MCH care (75). Insufficient attention is given to intervention across different geographical areas. In addition, digital literacy, Internet, and electric sources must be addressed to ensure equitable access to mHealth. As such, focus should be given to the usability, applicability, and sustainability of mHealth for MCH services.

In addition, evidence showed that the quality of maternal and newborn care depends on facility readiness (infrastructure, supplies, health workforce, service delivery approach), adherence to guidelines, and provision of skilled care (76). However, the challenge lies in the equitable distribution of resources to ensure that all women, regardless of their geographical area, religion, or ethnicity, have access to quality maternity care. In summary, quality maternal and newborn care could be achieved through different partners’ involvement, prioritizing quality MCH services, promoting equity through universal healthcare coverage, improving facility capability, and strengthening the healthcare system through resources (5). Collecting, monitoring, and evaluating data are important for quality improvement in healthcare. Standardized indicators and metrics can help identify gaps, measure outcomes, and inform decision-making.

Despite the overall positive findings, it is important to note that most of the included studies focused on providing care (pre- and postinterventions). Moreover, the review focused on strategies for improving maternity care rather than assessing the effectiveness of quality interventions. The strength of this scoping review is the inclusion of both published and gray literature. The PRISMA-ScR checklist was used, with no restriction on the publication date. However, it is essential to acknowledge that language restriction was applied, which may introduce a potential bias. Moreover, literature was not searched from EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINHAL, HINARI, and Maternity and Infant Care databases due to their.

Future research should focus on the impact of the physical environment (healthcare setup, medical equipment, drugs, and supplies), culture, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness of interventions on the quality of MCH care. Long-term impact of quality intervention should also be investigated. In addition, the impact of healthcare providers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, satisfaction, and adherence to MCH guidelines on quality maternal care should be considered. Projects focusing on capacity building, knowledge, and skill retention could significantly improve maternal and newborn care. Finally, mixed-method studies should be conducted to investigate the facilitation and barriers of quality improvement interventions for maternal and newborn care. Moreover, studies on emotional and functional referral systems to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care should be conducted.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this scoping review identifies and maps various maternal and newborn quality improvement interventions in Ethiopia, focusing on mobile and electronic health, quality improvement standards, and human resource mobilization. This review found that community involvement, health education, mHealth, data-driven approaches, and strengthening the health system are crucial strategies for improving maternal and newborn care in Ethiopia. Future research should consider the impact of the physical environment, culture, sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and long-term effects of interventions, as well as healthcare providers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, satisfaction, and adherence to guidelines.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DB: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. TM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TL: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KG: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgwh.2024.1289835/full#supplementary-material

References

1. WHO. Bringing Quality Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Care Closer to the Community (2022). Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/namibia/news/bringing-quality-reproductive-maternal-newborn-and-child-health-care-closer-community (Accessed June 9, 2022)..

2. Koblinsky M, Chowdhury ME, Moran A, Ronsmans C. Maternal morbidity and disability and their consequences: neglected agenda in maternal health. J Health Popul Nutr. (2012) 30(2):124. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i2.11294

3. Storeng KT, Baggaley RF, Ganaba R, Ouattara F, Akoum MS, Filippi V. Paying the price: the cost and consequences of emergency obstetric care in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. (2008) 66(3):545–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.001

4. ICF CA. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, MD: CSA and ICF (2016).

5. Koblinsky M, Moyer CA, Calvert C, Campbell J, Campbell OM, Feigl AB, et al. Quality maternity care for every woman, everywhere: a call to action. Lancet. (2016) 388(10057):2307–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31333-2

6. Desa U. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2016). Available online at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (Accessed July 13, 2022).

7. WHO. Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education for Universal Health Coverage 2030 (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515849 (Accessed July 13, 2022).

8. WHO. Making Pregnancy Safer: The Critical Role of the Skilled Attendant: A Joint Statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

9. Raven JH, Tolhurst RJ, Tang S, Van Den Broek N. What is quality in maternal and neonatal health care? Midwifery. (2012) 28(5):e676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.09.003

10. Hespe C, Rychetnik L, Peiris D, Harris M. Informing implementation of quality improvement in Australian primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18.29661247

11. Tunçalp Ӧ, Were W, MacLennan C, Oladapo O, Gülmezoglu A, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG. (2015) 122(8):1045. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13451

12. Hagaman AK, Singh K, Abate M, Alemu H, Kefale AB, Bitewulign B, et al. The impacts of quality improvement on maternal and newborn health: preliminary findings from a health system integrated intervention in four Ethiopian regions. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05391-3

13. Jolivet R. Strategies Towards Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM) (2015). Available online at: https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/qoc/quality-of-care/strategies-toward-ending-preventable-maternal-mortality (Accessed July 13, 2022).

14. WHO. Every Newborn: An Action Plan to End Preventable Deaths (2014). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241507448 (Accessed July 13, 2022).

15. Kowalewski M, Jahn A. Health professionals for maternity services: experiences on covering the population with quality maternity care. Safe Motherhood Strateg. (2001) 17.

16. Jolivet RR, Moran AC, O’Connor M, Chou D, Bhardwaj N, Newby H, et al. Ending preventable maternal mortality: phase II of a multi-step process to develop a monitoring framework, 2016–2030. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18(1):258. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1763-8

17. Hodin S. Strategies Toward Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM) Under the Sustainable Development Goals Agenda Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (2016). Available online at: https://www.mhtf.org/2016…strategies-towardending-preventable-maternal-mortality.

18. Negero MG, Sibbritt D, Dawson A. How can human resources for health interventions contribute to sexual, reproductive, maternal, and newborn healthcare quality across the continuum in low-and lower-middle-income countries? A systematic review. Hum Resour Health. (2021) 19(1):1–28. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00601-3

19. Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Gülmezoglu AM. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low-and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. (2014) 11(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-71

20. WHO. Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities 2016 (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511216 (Accessed September 30, 2022).

21. WHO. Working with Individuals, Families and Communities to Improve Maternal and Newborn Health: A Toolkit for Implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017).

22. WHO. WHO Recommendations on Health Promotion Interventions for Maternal and Newborn Health (2015). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241508742 (Accessed March 4, 2022).

23. Lassi ZS, Das JK, Salam RA, Bhutta ZA. Evidence from community level inputs to improve quality of care for maternal and newborn health: interventions and findings. Reprod Health. (2014) 11(2):1–19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S1-S1

24. George AS, Branchini C, Portela A. Do interventions that promote awareness of rights increase use of maternity care services? A systematic review. PLoS One. (2015) 10(10):e0138116.26444291

25. Hemminki E, Long Q, Zhang W-H, Wu Z, Raven J, Tao F, et al. Impact of financial and educational interventions on maternity care: results of cluster randomized trials in rural China, CHIMACA. Matern Child Health J. (2013) 17(2):208–21. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0962-6

26. Lassi ZS, Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. J Dev Eff. (2012) 4(1):151–87. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2012.655911

27. World Health Organization. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative. Geneva: OECD Publishing (2018).

28. FMoH. Health Sector Transformation Plan II. 2020/2021-2024/2025 (2021). Available online at: https://fp2030.org/sites/default/files/HSTP-II.pdf (Accessed January 16, 2022).

29. WHO. Make Every Mother and Child Count the World health Report Geneva (2005). Available online at: whqlibdoc.who.int/whr/2005/9241562900pdf.

30. Graham WJ, Varghese B. Quality, Quality, Quality: Gaps in the Continuum of Care. United Kingdom: National Institutes of Health (2012).

31. Birhane BM, Alemu YA, Belay DM, Mihiretie GN, Aytenew TM, Tiruneh YM. Interventions to Improve the Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Ethiopia: A Scoping Review Protocol (2023). Available online at: https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Interventions_to_improve_the_quality_of_maternal_and_newborn_care_in_Ethiopia_a_scoping_review_protocol/24086895 (Accessed July 13, 2022).

32. Bragge P, Clavisi O, Turner T, Tavender E, Collie A, Gruen RL. The global evidence mapping initiative: scoping research in broad topic areas. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2011) 11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-92

33. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

34. Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. (2020) 18(10):2119–26. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

35. Ehrich K, Freeman GK, Richards SC, Robinson IC, Shepperd S. How to do a scoping exercise: continuity of care. Res Policy Plan. (2002) 20(1):25–9.

36. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

37. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews (2015). Available online at: https://repositorio.usp.br/directbitstream/5e8cac53-d709-4797-971f 263153570eb5/SOARES%2C+C+B+doc+150.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2023).

38. Nigussie ZY, Zemicheal NF, Tiruneh GT, Bayou YT, Teklu GA, Kibret ES, et al. Using mHealth to improve timeliness and quality of maternal and newborn health in the primary health care system in Ethiopia. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2021) 9(3):668–81. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00685

39. Ayalew F, Eyassu G, Seyoum N, van Roosmalen J, Bazant E, Kim YM, et al. Using a quality improvement model to enhance providers’ performance in maternal and newborn health care: a post-only intervention and comparison design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1303-y

40. Biadgo A, Legesse A, Estifanos AS, Singh K, Mulissa Z, Kiflie A, et al. Quality of maternal and newborn health care in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06680-1

41. Gebrehiwot Y, Tewolde BT. Improving maternity care in Ethiopia through facility based review of maternal deaths and near misses. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2014) 127:S29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.08.003

42. Kassa A, Mokgadi M. Effectiveness of mHEALTH application at primary health care to improve maternal and new-born health services in rural Ethiopia: comparative study. medRxiv. (2022).

43. Dadi TL, Medhin G, Kasaye HK, Kassie GM, Jebena MG, Gobezie WA, et al. Continuum of maternity care among rural women in Ethiopia: does place and frequency of antenatal care visit matter? Reprod Health. (2021) 18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-01058-8

44. Getachew A, Ricca J, Cantor D, Rawlins B, Rosen H, Tekleberhan A, et al. Quality of care for prevention and management of common maternal and newborn complications: a study of Ethiopia's hospitals. Baltimore Jhpiego. (2011) 6:1–9.

45. Lund S, Boas IM, Bedesa T, Fekede W, Nielsen HS, Sørensen BL. Association between the safe delivery app and quality of care and perinatal survival in Ethiopia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. (2016) 170(8):765–71. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0687

46. Sibley LM, Tesfaye S, Fekadu Desta B, Hailemichael Frew A, Kebede A, Mohammed H, et al. Improving maternal and newborn health care delivery in rural Amhara and Oromiya regions of Ethiopia through the maternal and newborn health in Ethiopia partnership. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2014) 59(s1):S6–20.24588917

47. Desta BF, Mohammed H, Barry D, Frew AH, Hepburn K, Claypoole C. Use of mobile video show for community behavior change on maternal and newborn health in rural Ethiopia. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2014) 59(s1):S65–72. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12111

48. Asefa A, Morgan A, Bohren MA, Kermode M. Lessons learned through respectful maternity care training and its implementation in Ethiopia: an interventional mixed methods study. Reprod Health. (2020) 17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-00953-4

49. Mengistu B, Alemu H, Kassa M, Zelalem M, Abate M, Bitewulign B, et al. An innovative intervention to improve respectful maternity care in three districts in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03934-y

50. Mihret H, Atnafu A, Gebremedhin T, Dellie E. Reducing disrespect and abuse of women during antenatal care and delivery services at Injibara General Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a pre–post interventional study. Int J Women’s Health. (2020) 12:835. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S273468

51. Berhanu D, Allen E, Beaumont E, Tomlin K, Taddesse N, Dinsa G, et al. Coverage of antenatal, intrapartum, and newborn care in 104 districts of Ethiopia: a before and after study four years after the launch of the national community-based newborn care programme. PLoS One. (2021) 16(8):e0251706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251706

52. Villadsen SF, Negussie D, GebreMariam A, Tilahun A, Friis H, Rasch V. Antenatal care strengthening for improved quality of care in Jimma, Ethiopia: an effectiveness study. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1708-3

53. Tesfaye S, Barry D, Gobezayehu AG, Frew AH, Stover KE, Tessema H, et al. Improving coverage of postnatal care in rural Ethiopia using a community-based, collaborative quality improvement approach. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2014) 59(1):12168.

54. Lindtjørn B, Mitiku D, Zidda Z, Yaya Y. Reducing maternal deaths in Ethiopia: results of an intervention programme in Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2017) 12(1):e0169304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169304

55. Bitewulign B, Abdissa D, Mulissa Z, Kiflie A, Abate M, Biadgo A, et al. Using the WHO safe childbirth checklist to improve essential care delivery as part of the district-wide maternal and newborn health quality improvement initiative, a time series study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06781-x

56. World Health Organization. Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities (2016). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511216 (Accessed September 15, 2023).

57. Hailemariam T, Atnafu A, Gezie LD, Tilahun B. Why maternal continuum of care remains low in Northwest Ethiopia? A multilevel logistic regression analysis. PLoS One. (2022) 17(9):e0274729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274729

58. Graham WJ, Varghese B. Quality, quality, quality: gaps in the continuum of care. Lancet. (2012) 379(9811):e5–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62267-2

59. Chaka EE, Parsaeian M, Majdzadeh R. Factors associated with the completion of the continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health services in Ethiopia. Multilevel model analysis. Int J Prev Med. (2019) 10.31516677

60. Dohbit JS, Woks NIE, Koudjine CH, Tafen W, Foumane P, Bella AL, et al. The increasing use of the WHO safe childbirth checklist: lessons learned at the Yaoundé Gynaeco-Obstetric and Paediatric Hospital, Cameroon. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03966-4

61. Tuyishime E, Park PH, Rouleau D, Livingston P, Banguti PR, Wong R. Implementing the World Health Organization safe childbirth checklist in a district hospital in Rwanda: a pre- and post-intervention study. Maternal health. Neonatol Perinatol. (2018) 4(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s40748-018-0075-3

62. Kaplan L, Richert K, Hülsen V, Diba F, Marthoenis M, Muhsin M, et al. Impact of the WHO safe childbirth checklist on safety culture among health workers: a randomized controlled trial in Aceh, Indonesia. PLoS Global Public Health. (2023) 3(6):e0001801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001801

63. Chaulagain DR, Ashish KC, Wrammert J, Brunell O, Basnet O, Malqvist M. Effect of a scaled-up quality improvement intervention on health workers’ competence on neonatal resuscitation in simulated settings in public hospitals: a pre-post study in Nepal. PLoS One. (2021) 16(4):e0250762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250762

64. Alhassan RK, Nketiah-Amponsah E, Ayanore MA, Afaya A, Salia SM, Milipaak J, et al. Impact of a bottom-up community engagement intervention on maternal and child health services utilization in Ghana: a cluster randomised trial. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7180-8

65. Edward A, Krishnan A, Ettyang G, Jung Y, Perry HB, Ghee AE, et al. Can people-centered community-oriented interventions improve skilled birth attendance? Evidence from a quasi-experimental study in rural communities of Cambodia, Kenya, and Zambia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2020) 20:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03223-0

66. Maldonado LY, Bone J, Scanlon ML, Anusu G, Chelagat S, Jumah A, et al. Improving maternal, newborn and child health outcomes through a community-based women’s health education program: a cluster randomised controlled trial in western Kenya. BMJ Global Health. (2020) 5(12):e003370. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003370

67. Questa K, Das M, King R, Everitt M, Rassi C, Cartwright C, et al. Community engagement interventions for communicable disease control in low-and lower-middle-income countries: evidence from a review of systematic reviews. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01169-5

68. McLeish J, Redshaw M. Peer support during pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study of models and perceptions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2015) 15(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0685-y

69. Beck DC, Munro-Kramer ML, Lori JR. A scoping review on community mobilisation for maternal and child health in sub-Saharan Africa: impact on empowerment. Glob Public Health. (2019) 14(3):375–95. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1516228

70. Lund S, Rasch V, Hemed M, Boas IM, Said A, Said K, et al. Mobile phone intervention reduces perinatal mortality in Zanzibar: secondary outcomes of a cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2014) 2(1):e2941. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2941

71. Hussain T, Smith P, Yee LM. Mobile phone–based behavioral interventions in pregnancy to promote maternal and fetal health in high-income countries: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2020) 8(5):e15111. doi: 10.2196/15111

72. Feroz A, Perveen S, Aftab W. Role of mHealth applications for improving antenatal and postnatal care in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2664-7

73. Tamrat T, Kachnowski S. Special delivery: an analysis of mHealth in maternal and newborn health programs and their outcomes around the world. Matern Child Health J. (2012) 16(5):1092–101. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0836-3

74. Amoakoh-Coleman M, Borgstein AB-J, Sondaal SF, Grobbee DE, Miltenburg AS, Verwijs M, et al. Effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting health care workers to improve pregnancy outcomes in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2016) 18(8):e226. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5533

75. Mildon A, Sellen D. Use of mobile phones for behavior change communication to improve maternal, newborn and child health: a scoping review. J Glob Health. (2019) 9(2):020425. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020425

Keywords: Ethiopia, intervention, maternal, quality, scoping review

Citation: Birhane BM, Assefa Y, Belay DM, Nibret G, Munye Aytenew T, Liyeh TM, Gelaw KA and Tiruneh YM (2024) Interventions to improve the quality of maternal care in Ethiopia: a scoping review. Front. Glob. Womens Health 5:1289835. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1289835

Received: 19 September 2023; Accepted: 25 March 2024;

Published: 17 April 2024.

Edited by:

Tadese Melaku Abegaz, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, United StatesReviewed by:

Efrata Ashuro Shegena, Hawassa University, EthiopiaBerhan Yikna, Debre Berhan University, Ethiopia

© 2024 Birhane, Assefa, Belay, Nibret, Munye Aytenew, Liyeh, Gelaw and Tiruneh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Binyam Minuye Birhane biniamminuye@yahoo.com

Abbreviations ANC, antenatal care; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; MCH, maternal and child health; PNC, postnatal care; QI, quality intervention; PRISMA-ScR, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews; WHO, World Health Organization.

Binyam Minuye Birhane

Binyam Minuye Birhane Yibeltal Assefa3

Yibeltal Assefa3  Demeke Mesfin Belay

Demeke Mesfin Belay Gedefaye Nibret

Gedefaye Nibret Tigabu Munye Aytenew

Tigabu Munye Aytenew Tewachew Muche Liyeh

Tewachew Muche Liyeh Kelemu Abebe Gelaw

Kelemu Abebe Gelaw