Social Connectedness, Excessive Screen Time During COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Review of Current Evidence

- 1Indian Institute of Public Health Gandhinagar (IIPHG), Gandhinagar, India

- 2Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai, India

With an advancement of digital technology, excessive screen time has become a grave concern. This has pushed researchers and practitioners to focus on digital well-being. Screen time during COVID-19 has further increased as a result of public health measures enforced by governments to curb the pandemic. With the global societies under lockdown, the only medium to stay socio- emotionally connected was the digital one. A lack of comprehensive empirical overviews on screen time in COVID-19 era in the present literature prompted us to conduct this review. The present review attempts to understand the virtual social connectedness, excessive use of digital technology, its consequences and suggest strategies to maintain healthy use of digital technology. Results reveal that screen time has increased drastically during COVID-19. Though there are mixed consequences of prolonged screen time use and blurred understanding between healthy and unhealthy social connectedness over digital media, the suggestions for negative implications on (physical and) mental health warrant a strict need for inculcating healthy digital habits, especially knowing that digital technology is here to stay and grow with time.

Introduction

The last two decades have seen an explosion in the use of digital technology. It has accelerated human’s exposure to prolonged screen time which is becoming a growing concern. Digital technology is essentially the use of electronic devices to store, generate or process data; facilitates communication and virtual interactions on social media platforms using the internet (Vizcaino et al., 2020). Electronic devices include computer, laptop, palmtop, smartphone, tablet or any other similar devices with a screen. They are a medium of communication, virtual interactions and connectedness between people. Social connection is fundamental to humans. In addition, social connectedness also enhances mental well-being. COVID-19 pandemic has imposed digital platforms as the only means for people to maintain socio-emotional connection (Kanekar and Sharma, 2020). The digital technology is influencing how people use digital devices to maintain, or avoid social relations or how much time to spend for virtual social connectedness (Antonucci et al., 2017).

Screen time refers to the amount of time spent and the diverse activities performed online using digital devices (DataReportal, 2020). For instance, screen time encompasses both, using digital devices for work purposes (regulated hours of work or educational purpose) as well as for leisure and entertainment (unregulated hours of gaming, viewing pornography or social media use).

The COVID-19 pandemic came with restrictions, regulations and stay-at-home orders. This meant that people stayed indoors, offices remained shut, playgrounds were empty and streets remained barren of human interaction. Many individuals could not return to their homes, many stuck in foreign lands and many in solitude. As a result, the usage of digital devices has increased manifold across the globe. Irrespective of age, people are pushed to rely on digital platforms. Education, shopping, working, meeting, entertaining and socializing suddenly leaped from offline to online. Here, digital technology came as a blessing in disguise, enabling individuals to remain emotionally connected despite the social distancing. At the same time, prolonged screen time has caused concerns related to its impact on physical and mental health. While mindful (and regulated) use of digital devices is linked with well-being, excessive screen time is reported to be associated with a range of negative mental health outcomes such as psychological problems, low emotional stability, and greater risk for depression or anxiety (Allen et al., 2019; Aziz Rahman et al., 2020; Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2020). Negative consequences often result when digital use is impulsive, compulsive, unregulated or addictive (Kuss and Lopez-Fernandez, 2016).

Restricted social interactions imposed by the pandemic aggravated the over-use of digital devices for socializing which included virtual dates, virtual tourism, virtual parties, and family conferences (Pandey and Pal, 2020). Notably, in times of social distancing; there is a possibility that screen time may not negatively interfere with well-being as it is the only way to remain socially connected. However, mindful use of the digital screen time needs to be under the check. The unprecedented digital life during the pandemic also gave rise to increased levels of anxiety, sad mood, uncertainty and negative emotions like irritability and aggression, a normative response to pandemic (Rajkumar, 2020). However, anxiety and aggression also meant an increase in cybercrimes and cyber-attacks (Lallie et al., 2021). This has raised concerns about the impact of screen time on mental health. A survey recorded about 50–70 percent increase in internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic and of that 50 percent of the time was spent engaging on social media in 2020 (Beech, 2020). Reiterating, it is difficult to discrepantly state healthy versus unhealthy extents of social connectedness over digital media; however, negative effects of digital technology are undeniable. Interesting to note is the fact that though digital health technology boomed, digital health and well-being demanded a lot more attention with prolonged hours being spent on the screen. Numerous studies have highlighted the increased screen time propelled by COVID-19; however, they are scattered. The present review synthesises the evidence on the use of digital technology in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, its impact on health and summarizes recommendations reported in the literature to foster positive health. It also identifies recommended digital habits to optimize screen time and warrant protection from its ill effects. Lastly, it introduces a multipronged approach to prevent adverse effects of prolonged screen time and promote healthy digital habits.

Methods

The review was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005).

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

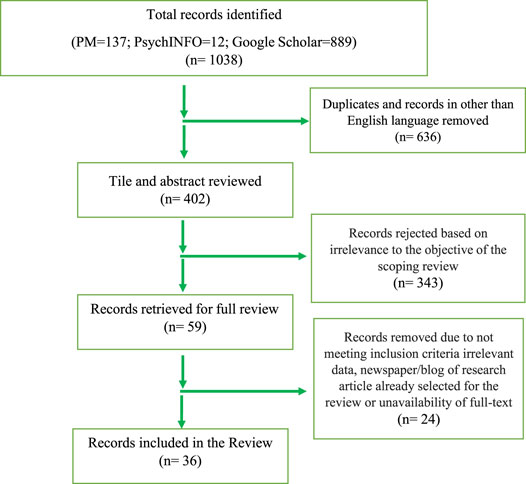

References for this review were identified through searches of PubMed, PsychINFO, and Google Scholar with the search terms “screen time,” “social connectedness,” “digital habits,” “health” and “COVID-19” from January 2020 until June 2021. These keywords were combined with Boolean operators to narrow down the search results. Manual searches were executed to identify additional articles based on the references mentioned in the articles selected for full- text review. Records published in English language were considered for the review. The initial search yielded 1,038 records (PubMed-137; PsychINFO-12; Google Scholar-889) of which 636 were excluded based on title review and duplications. Later 343 records were rejected based on the abstract review and 59 records were selected for full text reviews. Out of which, a total of 36 records (29 peer-reviewed articles & seven newspaper articles & blogs) met the inclusion criteria and were finally selected for the scoping review. The PRISMA chart is presented in Figure 1. The final reference list was generated on the basis of originality and relevance to the broad scope of this Review.

Inclusion criteria

• Records published between January 2020 until June 2021.

• Reviews or studies exploring social connectedness using digital platforms, screen time, and its consequences.

• Studies conducted in the context of COVID-19.

Exclusion criteria

• Studies published before January 2020.

• Studies published in other than English language.

Data Extraction

The literature search was done separately by two researchers (AP and PL). Initially selected records were coded in the domains such as author’s name, year of publication, type of publication, country of study conducted, screen time in the COVID-19, impact of increased screen time, and strategies for optimizing use of digital devices. The results were matched by repeating search exercises using keywords and removed duplicating and unqualified records based on the exclusion criteria. Full text of selected records was critically appraised. Overall data synthesis was reviewed by all authors.

Results

Of the 36 selected records, 29 articles were peer-reviewed (15 original research, two meta-analyses, five systematic reviews; four editorials/commentaries and three guidelines) and the rest seven were news articles and blogs. Studies were heterogeneous in terms of methodology and types of research. Most original studies were cross-sectional research and one study adapted a mixed method research approach. Records selected were published from 10 countries (Table 1), the majority of them were published in the United States (8) followed by that in India (6).

Key Findings From Meta-Analysis

Recent meta-analyses (Hancock et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019) have indicated mixed results from no significant impact to moderate impact of digital screen time on health and psychological well-being. Authors reported that discrepant positive and negative effects of screen time is contingent on what kind of the digital activity engaged in.

Synthesis of Reviewed Literature (Other Than Meta-Analysis)

There isn’t a singular aspect of social, economic or political development that has escaped the rapid and deep trenched transformation of the digital revolution. The lockdown induced by COVID-19 pandemic has been a unique social experiment that has impacted our social relationships and how we connect interpersonally. Some relations strengthened while others came under severe strain.

During the pandemic induced lockdown, people turned to social media, messaging applications and video conferencing platforms. These platforms provided people with an opportunity to stay connected (Kietzmann et al., 2011). Social connection and interaction is one of the strongest predictors of well-being, thus potentially impacting the mental health of a person. Research conducted to understand the impact of digital social interactions on well-being has shown both positive and negative effects (Gurvich et al., 2020; Pandey and Pal, 2020). Overall, people who spend some time using digital and social media are happier than those who do not use internet at all, but those who spend the most time online tend to be the least happy (Qin et al., 2020). For working people, checking email and being interrupted by digital messages was found to be linked with experiencing greater stress. Given that digital communications have increased manifold during the pandemic, these negative aspects of digital interactions may only be magnified while social distancing. Indispensable to note is that this is not a simplistic correlational understanding, there are several factors like personality traits, existing social support, thriving environment and balance with in-person communication bound to affect the screen time impact. Many people rely on technology to build and sustain relationships but at times over dependence on digital technology leaves people feeling qualitatively empty and alone. There is a need to regulate the digital social connectedness which can be established by mindful and healthy digital habits that can promote a balance between plugging in and unplugging, consequently impacting well-being and mental health.

Technology has had a profound impact on what it means to be social, challenging its overhauling essence. Furthermore, the coronavirus has atrophied the social skills of many individuals in the absence of peers. With most of us too used to interacting on digital platforms, we have missed the subtler nuances of what it means to exercise our social skills and etiquettes around people; which is only likely to surge especially when social distancing will fade. In COVID-19 times, it is important to question if over-engagement in being socially connected through digital technology (and social media platforms) is compulsive, negative use or a healthy coping mechanism? Another question that surfaces is also that social connectedness was promoted by digital platforms earlier that were organically blended by fact-to-face communication, but with physical distancing, how much does digital media facilitate social connectedness.

Increased Screen-Time During Lock-Down and COVID-19

Several research studies during the pandemic period (in countries like India, China, United States, Canada and Australia) have delineated the problem with increasing screen time. As aforementioned, COVID-19 aggravated use of digital devices and consequently its impact on health colossally (Bahkir and Grandee, 2020; Gupta, 2020; Ko and Yen, 2020; Moore et al., 2020; Small et al., 2020; Ting et al., 2020). Overall digital device usage increased by 5 h, giving a plunge to screen time up to 17.5 h per day for heavy users and an average of 30 h per week for non-heavy users (Balhara et al., 2020; Dienlin and Johannes, 2020; Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2020; Vanderloo et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2020). A recent study, (Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2020) reported 8.8 h of screen time among younger adults and 5.2 h among elderly (>65 years old), presenting concerns among these populations too. A recent narrative review discusses that screen time increased for children and adults (men and women) during the pandemic (as compared to pre-pandemic times) globally. The jump in screen time among children and adolescents was noted to be higher than what is the prescribed screen time by American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (from the recommended hours to more than 6 h). For adults, screen time has been between more than 60–80% from before the pandemic. However, there aren't any comparative studies to state exact differences for the same (Sultana et al., 2021). Another report prepared by the UNICEF had pointed out the several gaps and methodological limitations in evidence-based literature supporting the validity and utility of having arbitrary screen-time cutoffs in today's digital world (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017).

Impact of Increased Screen Time on Physical and Mental Health

Research has delineated negative impacts of increased screen time on physical and mental health. Problematic screen time is characterized by obsessive, excessive, compulsive, impulsive and hasty use of digital devices (Lodha, 2018).

Children and Adolescents

Children and youth showed lowered physical activity levels, less outdoor time, higher sedentary behaviour that included leisure screen time and more sleep during the coronavirus outbreak (Bahkir and Grandee, 2020). Sudden increase in complaints of irritability without internet connectivity and smartphone; gambling, inability to concentrate; absenteeism in online educational classes or work due to disturbed sleep cycle, and unavoidable excessive use of smart-phones have been reported in the media (Smith et al., 2020).

The two crucial negative impacts of screen time on the physical health of children & adolescents is that of sleep problems and increased risk of myopia (Singh and Balhara, 2021). A large number of original studies indicate excessive screen time has adverse health effects in long run such as physical health symptoms like eye strain, sleep disturbance, carpal tunnel syndrome, neck pain as well as mental health problems ranging from difficulties in concentration, obsession to diagnosable mental illness such as anxiety, depression and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Király et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2020; Oberle et al., 2020; Stavridou et al., 2021). In a study (George et al., 2018) with older adolescents aged between 18 and 20, researchers found that smartphone dependency can predict higher reports of depressive symptoms and loneliness. Another study (Twenge et al., 2018) revealed that the generation of teens, known as “iGen”–born after 1995–are more likely to experience mental health issues than counterparts–their millennial predecessors.

The mental health impacts of excessive digital use include attention-deficit symptoms, impaired emotional and social intelligence, social isolation, phantom vibration syndrome, and diagnosable mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and technology addiction like gaming disorder (Amin et al., 2020; Dienlin and Johannes, 2020; King et al., 2020; Lanca and Saw, 2020; Lodha and De Sousa, 2020; Oswald et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020; Xiang et al., 2020; Hudimova, 2021; Wong et al., 2021). Though digital devices kept many socially and emotionally connected, screen time also resulted in experiences of irritability, corona-anxiety, sleep problems, emotional exhaustion, isolation, social media fatigue and screen fatigue and phantom vibration syndrome (Gurvich et al., 2020; Lodha and De Sousa, 2020; Hudimova, 2021). Although few studies highlight the psychiatric disorders (Stiglic and Viner, 2019) among children and adolescents with excessive screen time use, the correlation between psychological well being and screen time among these populations remains inconsistent. The qualitative versus quantitative engagement with screen time is a prime factor to study its consequential effects.

Adults

The WHO highlighted that increased screen time replaces healthy behaviours and habits like physical activity and sleep routine, and leads to potentially harmful effects such as reduced sleep or day-night reversal, headaches, neck pain, myopia, digital eye syndrome and cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, high blood pressure, and insulin resistance due to increase in sedentary time among adults (World Health Organization, 2020). Evidently, increased screen time has alarmingly caused collateral damage to optical health, eating habits and sleep routine (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2020; Lanca and Saw, 2020; Wong et al., 2021). Studies have found association between excess screen time and poor mental health among adults (Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2020).

Quintessentially, the perception of the individual users and their kind of engagements (how they use and what they do), rather than mere longer duration, make screen time negative or positive (Twenge and Campbell, 2018). This has been ascertained by a large study done by Google as well (Google, 2019).

Key Recommendations Reported in the Reviewed Studies

Despite the potential adverse effects of screen time on health, it is impossible to abstain from screen time in modern times. Oftentimes, the most successful tactics to minimize technology harm are not technical at all, but behavioural such as self-imposed limitations on use of digital platforms, using non-digital means when possible and using digital platforms for better health and well-being.

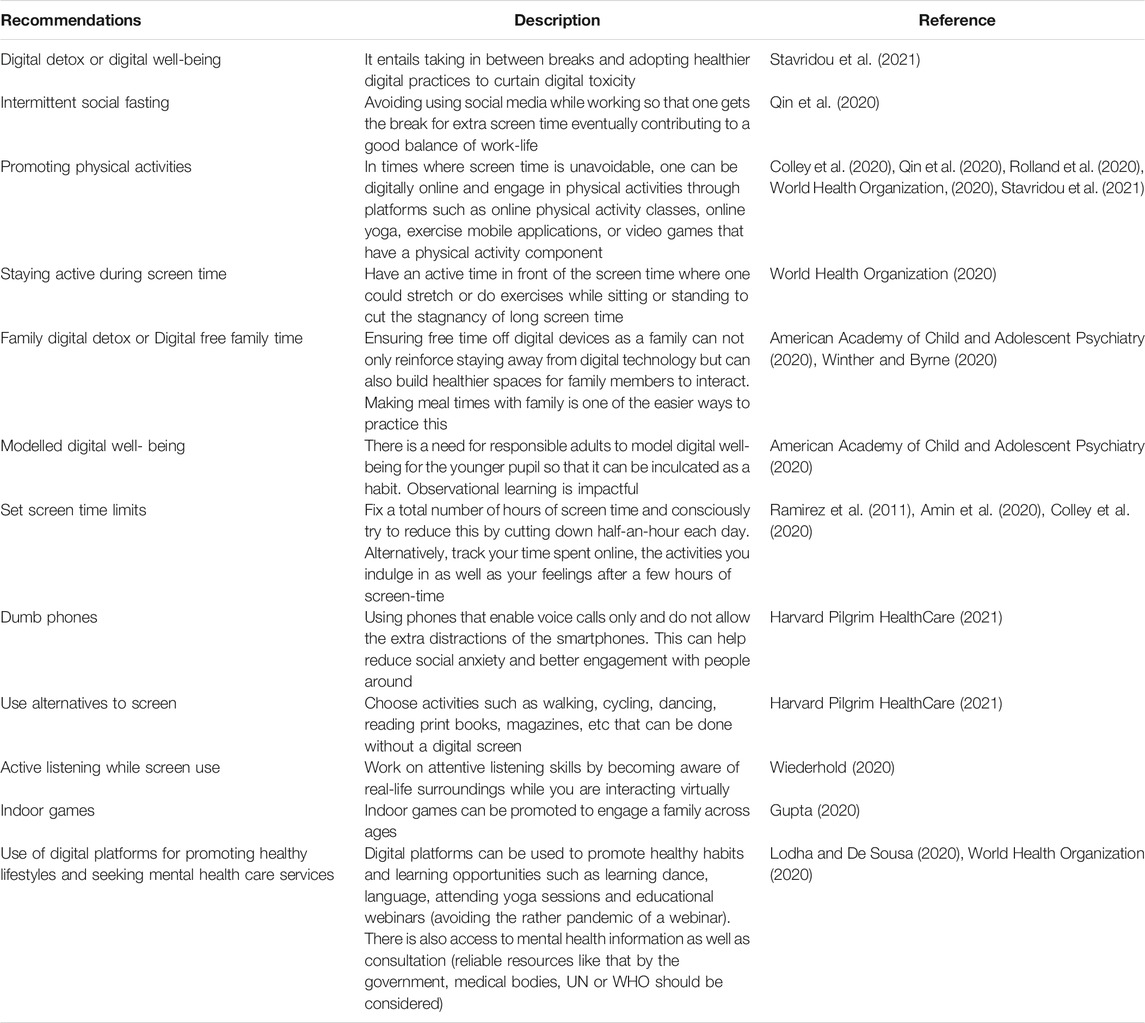

Unregulated amounts of screen time may lead to adverse effects on health. Studies clearly indicate differences in the effects of regulated, rational use and actively engaging with the digital devices than passively absorbing what is on the screen (Bahkir and Grandee, 2020; Dienlin and Johannes, 2020; Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2020; Pandey and Pal, 2020; Winther and Byrne, 2020). Digital devices can be adapted for numerous positive activities such as online exercise classes, mindfulness training, webinars on healthy lifestyles, and so on (Harvard Pilgrim HealthCare, 2021). Table 2 presents a synthesis of strategies recommended in reviewed studies that promote healthy digital habits among adults.

The above recommendations are conducive to socio-emotional connectedness among adults whilst keeping in mind that they practice healthy digital habits that promote better health and well-being. In addition, the following may be kept in mind:

1. Resort to audio calls to beat screen fatigue as a result of multiple video calls;

2. Use the voice note option on various social media platforms to reduce the screen stare time while typing a message;

3. Actively giving up phone phubbing (the act of snubbing someone you're talking with in person in favour of your phone) and connecting with people around.

4. Proactively be in touch with friends and relatives.

5. Making small talks, checking on people around about their days and ditching the digital devices once in a while can make for a good break and enhance social connections;

6. Use of mobile applications for promoting digital wellbeing. Mobile health apps are becoming increasingly popular to stay socially connected as well as aid mental wellbeing.

7. Healthy and discrete boundaries between the personal and professional temporal spaces is helpful.

Discussion

It is inevitable to realize the need to be socially connected with one another which has also led to momentous increase in screen time during the COVID-19 induced lockdown. Literature on screen time is reflective of both positive and negative consequences of screen time on (mental) health. Perhaps, digital technology offered a platform to deal with psychological reactions fuelled by COVID-19 if it were for a shorter period. However, the prolonged period of the pandemic has led the use of digital technology to culminate into threat for people’s physical as well as mental health. Literacy about digital habits and parental supervision on children's digital habits command attention. Increased use of games among youth is concerning. Indispensable to note is that digital habits must be balanced with the non-connected activities. It is important to be cognizant of what are the absolutes where one can depend on digital devices for convenience and betterment versus where one needs to pause and disconnect.

Three-Pronged Approach During COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

A concerted and evidence informed effort with a three-pronged approach is imperative to promote social connectedness while ensuring to prevent the ill effects of prolonged screen time. We propose immediate, intermediate and long-term strategies to promote healthy digital habits among communities during COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. They are described in the following sections and summarized in Table 3.

Immediate Strategy

Some immediate strategies encompass- generating evidence, synthesizing evidence on screen time across ages in the local context- that may assist in reducing excessive screen time and its negative consequences. Once evidence is established on screen-time, measures need to be rapidly implemented.

Promoting healthy digital habits is imperative. Although potentially challenging, public campaigns and establishing a reliable platform for sharing information regarding healthy digital habits are imperative. Using a behaviour change communication approach, people can be educated on signs of excessive screen time or gaming, healthy digital habits and available screening and treatment services. Partnership with digital media giants (such as IT companies, social media companies) to promote healthy digital habits, positive use of digital media can be scrutinized.

Intermediate Strategy

One of the intermediate measures can be developing digital health guidelines and standardized screening tools, remedial and treatment protocols (for treating internet addiction, gaming disorder, or online gambling) in localized contexts. Educational institutions, corporates and (mental) health agencies can comfortably ensure implementation of such guidelines. Further, establishing a strong referral for management of severe consequences of screen-time is indispensable.

Another measure is to embed digital health education into school and university curriculums. This may range from incorporating signs and symptoms of excessive screen time and risky digital habits in schools and universities, to setting the foundations of digital health modules in health and medical education.

Long-Term Strategy

In the evolving pandemic, restrained resources, economic and political pressure create a challenging atmosphere to promote evidence informed policy making and legislation. Despite these challenges, evidence-informed policy and legislations for protecting rights of people for monitoring digital use patterns and privacy of patients’ using telehealth services should take the forefront. Thus, incorporating screen-time and its consequences in the national health surveys can be an important policy decision to generate population level data as a long-term strategic plan.

Machine learning and big data analytics can be potential in understanding digital screen usage. The screenome project (Reeves et al., 2021) is an initiative that studies duration of screen time, specific content observed, created and/or shared, exposures to apps, social media, games etc. Such data catalyses to inform policy, maximizing the potential of digital devices and interventions to remedy its most pernicious effects.

Interventions to reduce distress and lifestyle modification along with diurnal practices to regulate screen time can potentially promote positive mental health while rejoicing in the inescapable digital use. Moreover, longitudinal studies can help assess digital habits across all ages, its impact on physical and mental health and cost-effectiveness of healthy digital habits promotion interventions in low-and-middle-income countries.

Conclusion

Largely, evidence indicates negative effects of prolonged screen time on health including mental health. Although digital technology provides avenues to connect socially, over indulgence or over use of digital devices can be harmful in the long-term. Promoting healthy digital habits and positive use of digital technology is inexorable to avert ill effects of excessive screen time. While it is important to adopt critical measures to cease the spread of COVID-19, it is necessary to assess and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on screen-time and prevent potential negative consequences. Having visited the impact of screen time on health, it calls for individual as well as systemic level action. Adapting immediate, short-term and long-term strategic measures can help scrutinize digital use and screen time not only amidst the regulations of COVID-19 but also ahead, considering that digitalisation is the way forward. Empowering individuals to make scientific-information based decisions is the need of the hour to mitigate these ill-effects. Building and imbibing healthy digital habits is a promising preventive measure conducive to health in the light of globally growing digitalisation.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Allen, M. S., Walter, E. E., and Swann, C. (2019). Sedentary Behaviour and Risk of Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 242, 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.081

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2020). Media Habits During COVID-19: Children & Teens on Screens in Quarantine. Available at: https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_libraries/covid-19/Screen- Time-During-COVID.pdf.

Amin, K. P., Griffiths, M. D., and Dsouza, D. D. (2020). Online Gaming During the COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Strategies for Work-Life Balance. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 1–7. doi:10.1007/s11469-020-00358-1

Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J., and Manalel, J. A. (2017). Social Relations and Technology: Continuity, Context, and Change. Innov. Aging. 1, igx029. doi:10.1093/geroni/igx029

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8 (1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aziz Rahman, M., Hoque, N., Sheikh, M., Salehin, M., Beyene, G., Tadele, Z., et al. (2020). Factors Associated With Psychological Distress, Fear and Coping Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. Global. Health. 16, 1–15. doi:10.1186/s12992-020-00624-w

Bahkir, F., and Grandee, S. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Digital Device-Related Ocular Health. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 68 (11), 2378. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2306_20

Balhara, Y. S., Kattula, D., Singh, S., Chukkali, S., and Bhargava, R. (2020). Impact of Lockdown Following COVID-19 on the Gaming Behavior of College Students. Indian J. Public Health. 64 (Supplement), S172–S176. doi:10.4103/ijph.ijph_465_20

Beech, M. (2020). COVID-19 Pushes Up Internet Use 70% and Streaming More Than 12%, First Figures Reveal. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/markbeech/2020/03/25/covid-19-pushes-up-internet-use-70- streaming-more-than-12-first-figures-reveal/?sh=6ad814cb3104.

Colley, R. C., Bushnik, T., and Langlois., K. (2020). Exercise and Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Rep. 31 (6), 3–11. doi:10.25318/82-003-x202000600001-eng

DataReportal (2020). Digital: 2020 Global Digital Overview [Internet]. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital- overview.

Di Renzo, L., Gualtieri, P., Pivari, F., Soldati, L., Attinà, A., Cinelli, G., et al. (2020). Eating Habits and Lifestyle Changes During COVID-19 Lockdown: An Italian Survey. J. Transl. Med. 18, 229–315. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5

Dienlin, T., and Johannes, N. (2020). The Impact of Digital Technology Use on Adolescent Well-Being. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 22 (2), 135–142. doi:10.31887/dcns.2020.22.2/tdienlin

George, M. J., Russell, M. A., Piontak, J. R., and Odgers, C. L. (2018). Concurrent and Subsequent Associations Between Daily Digital Technology Use and High-Risk Adolescents’ Mental Health Symptoms. Child. Dev. 89 (1), 78–88. doi:10.1111/cdev.12819

Gupta, A. (2020). Reducing Screen Time During COVID-19: 5 Indoor Games Families can Play to Strengthen Their Bond [Internet]. Available at: https://www.timesnownews.com/health/article/ reducing-screen-time-during-covid-19-5-indoor-games-families- can-play-to-strengthen -their-bond/636159.

Gupta, R., Grover, S., Basu, A., Krishnan, V., Tripathi, A., Subramanyam, A., et al. (2020). Changes in Sleep Pattern and Sleep Quality During COVID-19 Lockdown. Indian J. Psychiatry. 62 (4), 370–378. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20

Gurvich, C., Thomas, N., Thomas, E. H., Hudaib, A. R., Sood, L., Fabiatos, K., et al. (2020). Coping Styles and Mental Health in Response to Societal Changes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 20764020961790. doi:10.1177/0020764020961790

Hancock, J. T., Liu, X., French, M., Luo, M., and Mieczkowski, H. (2019). “Social media Use and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis,” in International Communication Association Conference, Washington, DC.

Harvard Pilgrim HealthCare (2021). How to Handle Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available at: https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/hapiguide/how-to-handle-screen-time-during-the-covid- 19-pandemic/.

Hudimova, A. (2021). Adolescents’ Involvement in Social Media: Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Soc. Sci. 1 (29). doi:10.31435/rsglobal_ijitss/30032021/7370

Kanekar, A., and Sharma, M. (2020). COVID-19 and Mental Well-Being: Guidance on the Application of Behavioral and Positive Well-Being Strategies. Healthcare 8 (3), 336. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030336

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2017). How Does the Time Children Spend Using Digital Technology Impact Their Mental Well-Being, Social Relationships and Physical Activity? an Evidence-Focused Literature Review. Florence: Innocenti Discussion Paper 2017-02. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research –Innocenti.

Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., and Silvestre, B. S. (2011). Social media? Get Serious! Understanding the Functional Building Blocks of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 54 (3), 241–251. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Billieux, J., and Potenza, M. N. (2020). Problematic Online Gaming and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Behav. Addict. 9 (2), 184–186. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00016

Király, O., Potenza, M. N., Stein, D. J., King, D. L., Hodgins, D. C., Saunders, J. B., et al. (2020). Preventing Problematic Internet Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consensus Guidance. Compr. Psychiatry. 100, 152180. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152180

Ko, C.-H., and Yen, J.-Y. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on Gaming Disorder: Monitoring and Prevention. J. Behav. Addict. 9, 187–189. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00040

Kuss, D. J., and Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016). Internet Addiction and Problematic Internet use: A Systematic Review of Clinical Research. World J Psychiatry. 6 (1), 143. doi:10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143

Lallie, H. S., Shepherd, L. A., Nurse, J. R. C., Erola, A., Epiphaniou, G., Maple, C., et al. (2021). Cyber Security in the age of COVID-19: A Timeline and Analysis of Cyber-Crime and Cyber-Attacks During the Pandemic. Comput. Security. 105, 102248. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102248

Lanca, C., and Saw, S. M. (2020). The Association Between Digital Screen Time and Myopia: A Systematic Review. Ophthalm. Physiol. Opt. 40 (2), 216–229. doi:10.1111/opo.12657

Liu, D., Baumeister, R. F., Yang, C.-C., and Hu, B. (2019). Digital Communication Media Use and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Comput. Mediat. Comm. 24 (5), 259–273. doi:10.1093/jcmc/zmz013

Lodha, P., and De Sousa, A. (2020). Mental Health Perspectives of COVID-19 and the Emerging Role of Digital Mental Health and Telepsychiatry. Arch. Med. Health Sci. 8 (1), 133. doi:10.4103/amhs.amhs_82_20

Lodha, P. (2018). Internet Addiction, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Among Indian Youth. Indian J. Ment. Health. 5 (4), 427. doi:10.30877/ijmh.5.4.2018.427-442

Meyer, J., McDowell, C., Lansing, J., Brower, C., Lee, S., Tully, M., et al. (2020). Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 18. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186469

Ministry of Human Resource Development (2020). The New Education Policy 2020. Available at: https://www.mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf.

Moore, S. A., Faulkner, G., Rhodes, R. E., Brussoni, M., Chulak-Bozzer, T., Ferguson, L. J., et al. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Virus Outbreak on Movement and Play Behaviours of Canadian Children and Youth: A National Survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17 (1), 85–11. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8

Oberle, E., Ji, X. R., Kerai, S., Guhn, M., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Gadermann, A. M., et al. (2020). Screen Time and Extracurricular Activities as Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Health in Adolescence: A Population-Level Study. Prev. Med. 141, 106291. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106291

Oswald, T. K., Rumbold, A. R., Kedzior, S. G. E., and Moore, V. M. (2020). Psychological Impacts of “Screen Time” and “Green Time” for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Scoping Review. PLoS One 15 (9), e0237725. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237725

Pandey, N., and Pal, A. (2020). Impact of Digital Surge during Covid-19 Pandemic: A Viewpoint on Research and Practice. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 55, 102171. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102196

Qin, F., Song, Y., Nassis, G. P., Zhao, L., Dong, Y., Zhao, C., et al. (2020). Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Emotional Well-Being During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (14), 5170. doi:10.3390/ijerph17145170

Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID and Mental Health: A Review of the Existing Literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 52, 102066. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

Ramirez, E. R., Norman, G. J., Rosenberg, D. E., Kerr, J., Saelens, B. E., Durant, N., et al. (2011). Adolescent Screen Time and Rules to Limit Screen Time in the Home. J. Adolesc. Health. 48 (4), 379–385. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.013

Reeves, B., Ram, N., Robinson, T. N., Cummings, J. J., Giles, C. L. Giles., Pan, J., et al. (2021). Screenomics: A Framework to Capture and Analyze Personal Life Experiences and the Ways that Technology Shapes Them. Hum. Comput. Interact. 36 (2), 150–201. doi:10.1080/07370024.2019.1578652

Rolland, B., Haesebaert, F., Zante, E., Benyamina, A., Haesebaert, J., and Franck, N. (2020). Global Changes and Factors of Increase in Caloric/salty Food Intake, Screen Use, and Substance Use During the Early COVID-19 Containment Phase in the General Population in France: Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6, e19630. doi:10.2196/19630

Singh, S., and Balhara, Y. P. S. (2021). “Screen-Time” for Children and Adolescents in COVID-19 Times: Need to Have the Contextually Informed Perspective. Indian J. Psychiatry. 63, 192–195. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_646_20

Small, G. W., Lee, J., Kaufman, A., Jalil, J., Siddarth, P., Gaddipati, H., et al. (2020). Brain Health Consequences of Digital Technology Use. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 22 (2), 179–187. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/gsmall

Smith, L., Jacob, L., Trott, M., Yakkundi, A., Butler, L., Barnett, Y., et al. (2020). The Association Between Screen Time and Mental Health During COVID-19: A Cross Sectional Study. Psychiatry Res. 292, 113333. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113333

Stavridou, A., Kapsali, E., Panagouli, E., Thirios, A., Polychronis, K., Bacopoulou, F., et al. (2021). Obesity in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 8 (2), 135. doi:10.3390/children8020135

Stiglic, N., and Viner, R. M. (2019). Effects of Screentime on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMJ Open. 9, e023191. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191

Sultana, A., Tasnim, S., Hossain, M. M., Bhattacharya, S., and Purohit, N. (2021). Digital Screen Time during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Public Health Concern. F1000Res. 10, 81. doi:10.12688/f1000research.50880.1

Ting, D. S. W., Carin, L., Dzau, V., and Wong, T. Y. (2020). Digital Technology and COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26 (4), 459–461. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0824-5

Twenge, J. M., and Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations Between Screen Time and Lower Psychological Well-Being Among Children and Adolescents: Evidence from a Population-Based Study. Prev. Med. Rep. 12, 271–283. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., and Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates Among U.S. Adolescents after 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 6 (1), 3–17. doi:10.1177/2167702617723376

Vanderloo, L. M., Carsley, S., Aglipay, M., Cost, K. T., Maguire, J., and Birken, C. S. (2020). Applying Harm Reduction Principles to Address Screen Time in Young Children amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 41 (5), 335–336. doi:10.1097/dbp.0000000000000825

Vizcaino, M., Buman, M., DesRoches, T., and Wharton, C. (2020). From TVs to Tablets: the Relation between Device-specific Screen Time and Health-Related Behaviors and Characteristics. BMC Public Health 20 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09410-0

Wiederhold, B. K. (2020). Children’s Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Boundaries and Etiquette. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 359–360. doi:10.1089/cyber.2020.29185.bkw

Winther, D. K., and Byrne, J. (2020). Rethinking Screen-Time in the Time of COVID-19. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/stories/rethinking-screen-time-time-covid-19.

Wong, C. W., Tsai, A., Jonas, J. B., Ohno-Matsui, K., Chen, J., Ang, M., et al. (2021). Digital Screen Time during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk for a Further Myopia Boom? Am. J. Ophthalmol. 223, 333–337. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.07.034

World Health Organization (2020). Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Excessive Screen Use and Gaming Considerations during COVID19. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333467.

Keywords: screen time, COVID-19, social connection, digital habits, positive mental health, digital health promotion

Citation: Pandya A and Lodha P (2021) Social Connectedness, Excessive Screen Time During COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Review of Current Evidence. Front. Hum. Dyn 3:684137. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.684137

Received: 22 March 2021; Accepted: 07 July 2021;

Published: 22 July 2021.

Edited by:

Kavita Pandey, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Pilar Rodriguez Martinez, University of Almeria, SpainShilpa Kumari, Banaras Hindu University, India

Copyright © 2021 Pandya and Lodha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pragya Lodha, pragya6lodha@gmail.com

Apurvakumar Pandya

Apurvakumar Pandya Pragya Lodha

Pragya Lodha