A long and winding road of referrals: investigating the relationship between healthcare and integration for Nairobi's urban displaced

- 1Human Settlements Group, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2Independent Researcher, Berlin, Germany

- 3Independent Researcher, Nairobi, Kenya

This article discusses what integration means in the context of forced displacement, focusing in particular on healthcare access of urban displaced people in Nairobi, Kenya. To do so, it uses a mixed dataset of survey data investigating health and healthcare access for displaced and host respondents in Nairobi's informal settlements Mathare and Kiambiu or Eastleigh South; key informant interviews with healthcare service providers working with displaced people; and finally a case study of a medical pathway taken by a displaced man living in a suburb to Nairobi. His journey demonstrates that documentation, information and language remain challenges specific to the displaced populations, and the importance of utilizing personal support networks, which will not be available to all patients. Notably, this patient's path to treatment brought him to clinics within Nairobi's informal settlements, where healthcare access is often inadequate for its own residents, including both locals and displaced. As such, it shows that where an integrated healthcare system falls short, it can be more beneficial for patients to navigate between the national system and support systems provided for urban refugees.

Displacement and healthcare in Nairobi's informal settlements

Kenya is home to over 500,000 refugees, out of which 92,778 officially live in the capital Nairobi (UNHCR, 2023). The majority are hosted in one of the two camp complexes: Dadaab and Kakuma. Despite recent legal changes through the Refugee Government of Kenya (2021) and a general policy direction toward “integrated settlements” where resources and services are intended to be shared between refugees and members of host communities, encampment remains the default for refugees in Kenya and under the recently enacted Refugee Act refugees will still be legally required to live in “designated areas1” with limited mobility (Owiso, 2022). Some refugees avoid the camps altogether and go straight to Nairobi, where they can apply for a mandate document from UNHCR instead of registering as a refugee in one of the camps. If they do register in a camp, they can only leave by applying for a “movement pass” from the authorities. Refugees can also apply for official permission to remain in the city as an urban refugee, which will allow them to bring their refugee ID and documentation to the city. This type of relocation is only granted for specific reasons, which can include health concerns that cannot be addressed within the camp (NRC and IHRC, 2018; Muindi and Mberu, 2019). Those who travel to Nairobi on a temporary movement pass and remain in the city without urban refugee status live without valid documentation, which makes them vulnerable to arrests and harassment (ibid).

This article focuses on refugees and asylum seekers living in Nairobi, with a particular focus on informal settlements like Mathare and Kiambiu, where many displaced people either live or go to access services. The UN defines informal settlements as “a group of individuals living in a dwelling that lacks one or more of the following conditions—the so-called five deprivations: (1) access to improved water, (2) access to improved sanitation facilities, (3) sufficient living area – not overcrowded, (4) structural quality/durability of dwellings, and (5) security of tenure” (UN-Habitat, 2016, p. 1). In Kenya, some estimates as much as 70 per cent of the population in Nairobi living in informal settlements (Mutisya and Yarime, 2011) and Mathare is home to just over 200,000 people according to the 2019 population census (City Population, n.d.).

During the British colonization of Kenya, Africans were restricted from living in the built-up part of Nairobi, but workers who came from rural areas needed some form of temporary residence in the city, which led to the construction of makeshift shelters on unoccupied land. After independence, many more moved from rural areas into the city to work as restrictions were lifted, which caused the informal settlements to expand rapidly (Wanjiru and Matsubara, 2017). In this sense these settlements were always home to migrants, initially Kenyan rural-urban migrants and today increasingly to cross-border migrants including refugees, who turn to informal settlements because of low-cost housing as well as social connections (IOM, 2013; Muindi and Mberu, 2019). Mathare in particular is home to refugees and migrants from a number of countries, but a significant population of migrants from Uganda has given one of the villages within the settlement where many of them work the nickname Kampala (Wanjiru and Matsubara, 2017). Eastleigh is predominantly home to Somali refugees (Carrier, 2017).

There are a number of health risks associated with living in informal settlements, as well as barriers to accessing healthcare (Arnold et al., 2014; Satterthwaite et al., 2018). A report from 2022 (De Falco, 2022) shows that private health facilities are more common than public ones within Mathare, while the public clinics suffer from understaffing and short opening hours, long waiting times and a lack of medical resources which often means patients have to buy medication from elsewhere. Quality-wise, however, the public clinics were well-regarded by informal settlement residents, but seeking care from inferior and more expensive private clinics was sometimes a necessity because of the much-reduced waiting time. Additionally, lack of public transportation (or inability to afford it) and poor road infrastructure can also limit the healthcare choices available to those living in informal settlement, depending on what is available within walking distance (ibid).

In theory, all refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya should be entitled to public healthcare through the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) which grants access to public healthcare facilities, but coverage is known to be patchy (Jemutai et al., 2021). For vulnerable displaced households in both refugee camps and cities UNHCR pays the regular insurance fee on behalf of refugees, but the majority need to cover this cost for themselves. The standard contribution for informal workers is 500 Kenyan shillings (around 5 USD) per month (UNHCR, 2022). In addition to public and private healthcare services, there are non-profit clinics run by NGOs or faith-based organizations, where services are usually provided for free (De Falco, 2022). In refugee camps, such clinics are funded by humanitarian aid and run by large NGOs including for example International Rescue Committee (IRC) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) (Betts et al., 2019). However, resources are often limited within these clinics too, and refugees can be referred to hospitals outside of the camps if they need care that is not available in the camp (NRC and IHRC, 2018).

In Mathare, unaffordability and lack of medication in public clinics are issues that affect migrants and hosts alike, but there are also issues that are specific to migrants and refugees, such as language barriers and documentation requirements (Arnold et al., 2014; Muindi and Mberu, 2019). In this article we present an overview of quantitative data comparing displaced people and hosts living in Mathare and Kiambiu or Eastleigh South, which includes general health and healthcare access. We then present a case study of the process for a displaced patient accessing healthcare through clinics in the informal settlement Mathare, despite living elsewhere in Nairobi, and discuss this in relation to integration.

Data and methodology

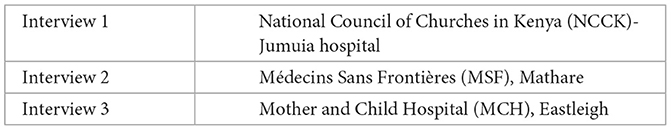

This article uses a quantitative dataset with a random sample of 273 displaced people (including refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants) and 131 Kenyan host respondents living in the informal settlements Mathare and Kiambiu or Eastleigh South. This data was collected in 2021. In addition to covering demographic information, the survey focused on livelihoods and wellbeing, the latter component importantly including both social connections and political representation alongside the usual indicators on physical health and basic needs. This data was collected from informal settlements as a complement to a broader camp-urban comparison2 between Somali refugees in the camp Dadaab and in Eastleigh North and East, which are built-up urban neighborhoods in Nairobi. In addition to survey data, qualitative key informant interviews relevant to healthcare access have also been included here. These interviews were conducted in 2021 and included the following stakeholders:

The two informal settlements where this data was collected are located on either side of the built-up part of Eastleigh. Mathare is located to the north and runs all the way along Mathare River. To the south is a smaller informal settlement built on what maps term “desert ground” next to Nairobi River, which is known as Kiambiu or Eastleigh South.

Finally, this article includes a case study of a medical pathway taken by a displaced man living in a suburb to Nairobi, which occurred in 2023. This was not a planned case study, but a situation researchers chose to document as and when it occurred, as an example of how an urban displaced person can utilize their networks and connections to access care that others in the same position would not be able to access. Importantly, as an urban displaced person accessing care through NGOs meant that the starting point was a clinic serving Eastleigh and the informal settlement Mathare, which was not where this patient lived. As such, it serves as a showcase of both barriers to healthcare and conditions within informal settlements, and further raises questions around how integration works in practice within such environments.

Understanding integration

The data presented in this article illustrates the health and integration context of Nairobi's informal settlements, complemented by a case study of a displaced person navigating an unusual healthcare journey, as a result of the lack of access through the regular integrated healthcare system. In order to place this into the context of integration, this section introduces relevant literature on the concept. This starts by looking at integration in high-income country contexts, as much refugee integration literature is focused on resettlement, to then turn to the East African context and how integration has been applied and studied there. Finally, it discusses the concept of local integration as a durable solution in refugee hosting states, which includes the role of humanitarian organizations in service provision which is also relevant to the case study we present below.

Europe and resettlement contexts

In high-income countries receiving resettled refugees and asylum seekers, integration is often high on the political agenda even though the concept itself is not necessarily clearly defined (Rytter, 2018). Ager and Strang (2008) have presented a conceptual framework for integration that has gained traction with policymakers (Strang and Quinn, 2019). Among their domains of integration are what they term markers and means, which covers access to employment, housing, education and healthcare. Achievements in this area are often cited as key indicators—or markers—of successful integration, for example within the UK Government's Indicators of Integration Framework (2019). However, it is not necessarily clear what the integration endpoint is. Official measures of integration are commonly done by comparing migrant populations against locals or hosts in key areas of markers and means, including education, employment, health and housing. By making local populations the benchmark, the assumption that follows is that migrant populations are integrated when they behave similarly or achieve similar outcomes to their non-migrant neighbors, which can be problematic. Using Rytter (2018), should increasing divorce rates among immigrants in Denmark be seen as positive for integration since they more closely match those of the local community? And are high grades among immigrant children reflective of cultural pressure, or of positive integration? Another question is when the comparison becomes arbitrary, and how many decades later migration can or should be treated as the main explanatory factor for any possible differences in statistics.

The focus on means in addition to markers or outcomes is intended to emphasize the interconnection between these areas, since an outcome in one area can enable further achievement in another (Home Office, 2019). These are well-known and self-explanatory connections, for example that access to housing can lead to better health, that education opportunities can lead to employment, and so on. An important part of acknowledging these as means, however, is that it highlights the role of governments and policymakers in enabling integration outcomes. It is not just up to migrant populations to adapt to their new environments and do what they can to achieve the best outcomes; they also need to be granted access and support to do so. This aligns with common understandings of integration as a two-way process between migrant newcomers and the receiving society, where both adapt to one another (Rytter, 2018). However, while receiving governments are expected to enable migrant populations to integrate, the two-way part of the concept does not appear to include changing on the part of local society as the focus remains on the actions of the migrant population. In this sense, it is worth questioning whether integration is just a government-supported form of its predecessor concept assimilation, which expected migrants to virtually blend in with their environments (Rumbaut, 1997).

In addition to the markers and means of integration, Ager and Strang (2008) focus on facilitators of integration, including language skills and cultural knowledge that can “remove barriers” (ibid: 177) to enable integration. Further, they consider citizenship and rights the foundation of integration. While full citizenship is not always an option for migrants, the rights granted to different migrant groups and to what extent they differ from those granted to citizens will of course have a huge influence on what migrants can achieve. Baldi and Goodman (2015) note that migrant rights are often conditioned on certain behaviors, through what they call membership conditionality structures. This can include for example compulsory language or culture training. In this way, states take an active role in “turning outsiders into insiders” (Baldi and Goodman, 2015, p. 1152). This can also vary for different migrant groups. In the UK for example, asylum seekers are actively excluded from integration processes and measures while their claims are processed, which often takes many years (Ager and Strang, 2008).

Finally, Ager and Strang's framework considers social connection, which they view as the “connective tissue” between the foundation of rights on the one hand and the integration outcomes on the other (Ager and Strang, 2008, p. 177). While policy makers and politicians often focus on outcomes (and, to some extent, rights and requirements), the social connections are perhaps the most important domain for migrants themselves. Social connections are important in determining to what extent migrants feel integrated and have a sense of belonging in the communities where they live. Building on Putnam's social capital theory, this domain covers social bonds, which connect individuals with a social group that they identify with; social bridges, which connect different social groups with each other; and social links, which connect individuals with state functions or services (Strang and Quinn, 2019). While the divide between bonds and bridges has been criticized as arbitrary and potentially restrictive in their definition social groups based on nationality and ethnicity, the third category of social links is an important arena for the two-way direction of integration, as individual refugees and migrants often struggle to build links to public services without support and outreach form the host society (Baillot et al., 2023).

This theoretical framework provides important insights into the integration concept and how it is commonly understood and applied. Firstly, it clarifies that from the migrants' own point of view, appearing integrated through behaviors and outcomes that are understood to be markers of integration does not necessarily equate to feeling integrated in the community. The latter is attributed to social connections that can also enable integration outcomes, and it is important to acknowledge that there is a separation between the two. Secondly, this framework highlights the role of governments and policymakers in enabling and supporting integration, both by ensuring the rights of migrant populations and providing services to them. While there may not always be political will to do so, it clearly paints a picture of the importance of removing barriers and helping newly arrived populations settle, which is an important contrast to the context of local integration to be discussed below. Finally, and most importantly, this literature underscores that integration is always measured and understood using the host population's attributes and behaviors as a baseline. This makes citizenship the only real endpoint for integration, as it is unclear when regular variations within a population would otherwise cease to be attributed to migration.

If integration in practice means displaced populations need to adapt to their surroundings, the environment itself will make a crucial difference. In the context of an informal settlement, where local populations already struggle with adequate service provision from the state, this raises the question whether being equal to the locals' state of deprivation is the best displaced people can hope for, or if there is a scenario of “reverse integration” where any additional support (discussed below) provided for displaced people can also benefit locals and offer improvements for everyone.

Local integration as a durable solution

In the context of resettled refugees, governments within the receiving countries are usually invested in providing support for social links as well as achieving integration outcomes and removing barriers. However, only 1 per cent of the world's refugees are resettled to high-income countries every year, and the majority live in low and middle-income countries within the same region (UNHCR, 2023). For these refugees, integration is not encouraged but actively prevented by authorities who want to avoid a situation where displaced populations remain permanently (Long, 2014). Many host countries opt to keep refugees confined in camps, separated from local populations and supported predominantly by humanitarian organizations and international funds (Slaughter and Crisp, 2009). Camps have well-known negative impacts on both individuals and their ability to support themselves (Crisp, 2003), and most refugees3 today choose to live in cities. However, relocating to an urban area often equates to relinquishing access to humanitarian support provided in the camps, such as food and shelter. When it comes to covering basic needs and finding work, urban refugees are then forced to de-facto integrate with host communities in the cities where they live (Hovil, 2007).

When it comes to service provision, most countries (including Kenya) recognize the rights of displaced people to healthcare and (primary) education, but the way in which these are provided vary between states, depending on the extent to which host governments allow displaced populations to make use of national systems. If displaced people are not systemically integrated into existing systems providing education and healthcare (Bellino and Dryden-Peterson, 2018), international organizations can, to varying degrees, take on state functions that are not provided, which then creates a parallel system or “surrogate state” (Miller, 2017). While this form of state surrogacy is more common within refugee camps, it can happen in urban areas too where NGOs are present and have identified gaps in state-supported service provision. With a growing recognition of displaced populations living in urban areas from UNHCR, there has also been an expansion of non-governmental support for them (UNHCR, 2009, 2014).

Refugee support in protracted situations and urban contexts is often underpinned by a theory of changed that researchers at the Humanitarian Policy Group have termed “partial integration” (Crawford et al., 2015). This type of support recognizes that displacement will likely continue beyond the initial emergency support phase, but still works on the assumption that displaced populations will eventually return home. As such, it aims to include refugees within local systems and economies as far as possible, rather than duplicating services (Crawford et al., 2015, p. 20–22). Within Miller's model of state surrogacy, a partial integration support model could fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum from abdication, where states resign all responsibility for the displaced population to international organizations, to partnerships where the organizations instead work together with states to provide services (Miller, 2017, p. 30-31). In the case of healthcare provisions for urban refugees in Nairobi, as outlined above, UNHCR supporting refugees by paying their contributions to the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) would be an example of partnerships, while an NGO setting up and running a community health clinic would be an example of abdication.

Importantly, the partial integration model can still be temporary and dependent on external funding, while the support model termed de-facto integration accepts local integration (or onward or circular migration) as a durable solution. This type of support falls very clearly in the space of partnerships, as it builds on long-term inclusion of displaced populations in for example urban planning and local development strategies (Crawford et al., 2015, p. 22–24). In Kenya, the recent legal changes (see above) and accompanying county development plans that now do include refugees are a step in this direction, but in the case of Garissa and Turkana this is still limited to designated areas or camps (UNHCR Kenya, 2022).

Measuring de-facto and supported integration

Where integration in resettlement contexts is often to some extent supported by government actors, and formal local integration in countries of first asylum often resisted, there is another form of integration falling somewhere in between. As urban displaced populations are increasingly recognized by humanitarian and development actors, as well as by local authorities, attempts have been made to understand de-facto integration. In previous decades, when encampment was the preferred option for refugee support in countries of first asylum, refugees who chose to live in cities would in most contexts have to resign themselves from humanitarian support access, thereby creating their own integration under the radar (Harrell-Bond, 1986). Since 2009 UNHCR has an urban refugee policy and a model for supported integration. While not going as far as local integration, which to be considered a durable solution would include citizenship or permanent residency, de-facto integration may still be enabled by local authorities or certain forms of support for urban displaced populations.

Crisp (2004) describes local integration as “a process with three interrelated dimensions”: the legal dimension, the economic dimension, and the social dimension (Crisp, 2004, p. 1). Attempts have been made to quantify, measure, and understand de-facto integration, where the legal dimension is reduced or altogether missing. Building on the theoretical framework from Ager and Strang (2008) presented above, Beversluis et al. (2017) have presented a tool called the Refugee Integration Scale (RIS) which was developed and tested in Nairobi. It was created from six integration- related themes (Beversluis et al., 2017, p. 112–117) gathered from qualitative interviews and focus group data: challenges of urban poverty; documentation and legal status; culture and community trust; livelihoods and education; personal and community security; and, finally, hope and control. The resulting scale measuring integration is made up of 25 statements, positive or negative, which are then calibrated into an integration score.

The most relevant of these statements is RIS 22: “I am permitted to access healthcare services for me and my family just as easily as our Kenyan neighbors” (Beversluis et al., 2017, p. 122). The corresponding thematic area (challenges of urban poverty) highlights issues with healthcare access, alongside other basic needs and services, are often shared between urban refugees and locals. Refugees may, however, be affected by additional barriers, caused by restrictions or even misconceptions that they as urban refugees have access to the same level of humanitarian support that is available in refugee camps.

This captures an issue also touched upon by Jacobsen and Nichols (2011) in their report on profiling urban displaced populations to support their needs:

In low-income areas, where most refugees tend to live, it is important to determine whether and in what ways refugees are worse off than their neighbors, the local host population. In countries of first asylum, the urban poor face significant health, crime and poverty problems. Humanitarian programs can be seen as discriminatory when they target refugees whose neighbors may be equally badly off. Agencies need to justify—to host governments, to local people, and to donors—why they use resources to support one group and not others. If agencies can demonstrate that the target group is more vulnerable, or has special needs not faced by the larger population, targeting of resources can be more easily justified (Jacobsen and Nichols, 2011, p. 8).

Much like it is in resettlement and asylum contexts of the global north, integration in this context is measured in relation to the local population, which places a clear limitation on the extent to which de-facto integration can be supported, particularly by humanitarian and development actors focusing specifically on the displaced. Unless conditions are improved for locals too, there will always be a ceiling. Indeed, a displaced person who can access healthcare “as easily as their Kenyan neighbors” will not be particularly helped by that integration if the Kenyan neighbor also suffers from a lack of healthcare access and quality.

In this article, we focus on Nairobi's informal settlements as an example of a location where such a ceiling will exist. First, we examine demographic data of urban displaced people alongside hosts, in relation to their healthcare access, demonstrating small but noticeable disadvantages for the displaced. We then present a case study of a healthcare pathway taken by a displaced person in Nairobi, which took the route through the healthcare system in the informal settlement Mathare even though the person in question was not residing there. Together, this shows what healthcare integration in Nairobi's informal settlements can look like in practice, and how urban displaced people can use their personal networks to navigate the limitations of de-facto integration.

Empirical findings from Nairobi's informal settlements

This section uses the quantitative survey data collected in 2021 as a part of the research project Protracted Displacement in an Urban World. It aims to expand our understandings of healthcare access and issues within the informal settlements Mathare and Kiambiu or Eastleigh South, particularly for displaced populations. The data introduces indicators on healthcare access and explores the relationship between health and integration for displaced people.

Demographics

Our sub-sample4 consists of 273 displaced (136 women and 137 men) and 132 hosts (72 women and 60 men). Displaced respondents came from five countries—Uganda, Tanzania, Somalia, DRC, and Rwanda—with the majority (68%) being displaced from Uganda. Only around 52% of displaced respondents identified as refugees, while the rest described themselves as economic migrants or asylum seekers.

Aside from nationality and migration status, displaced respondents shared many characteristics with host respondents. Displaced respondents were 34 years old on average, had a household size of 3.4 and 28% of these households were headed by women. These characteristics were very similar for hosts, who had an average age of 36 years, a household size of 3.8 and 28% of households headed by women. Marital status was similar between hosts and displaced. Just over half of the respondents were married, and around 30% were single.

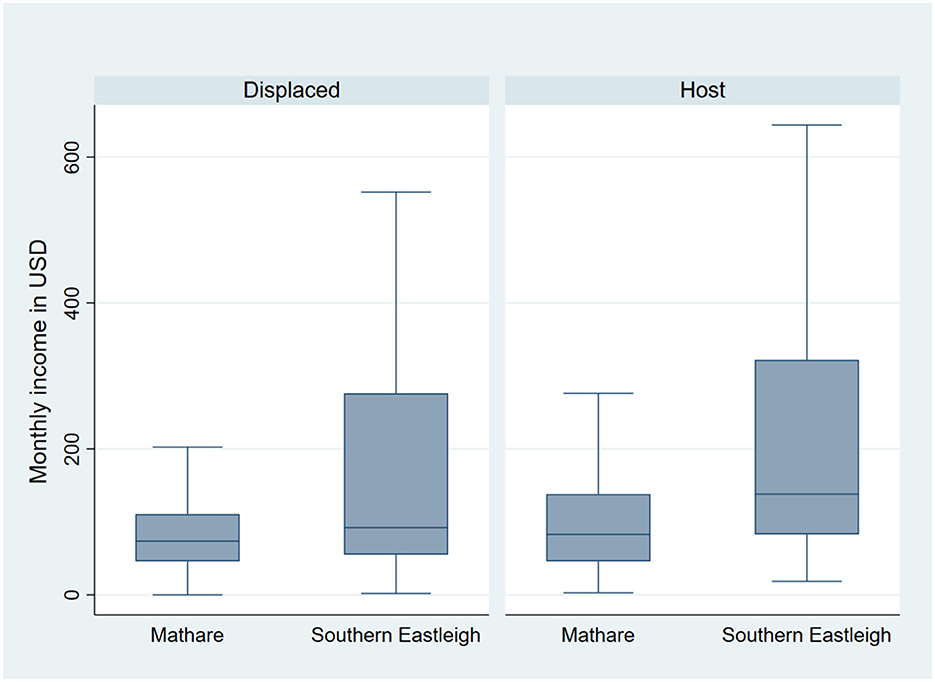

There were more apparent differences between displaced and host respondents in income (see Figure 1). Both displaced and host respondents earned higher incomes in southern Eastleigh with 215 USD and 279 USD respectively. In Mathare the average monthly income was much lower, at 92 USD for displaced and 107 for host respondents.

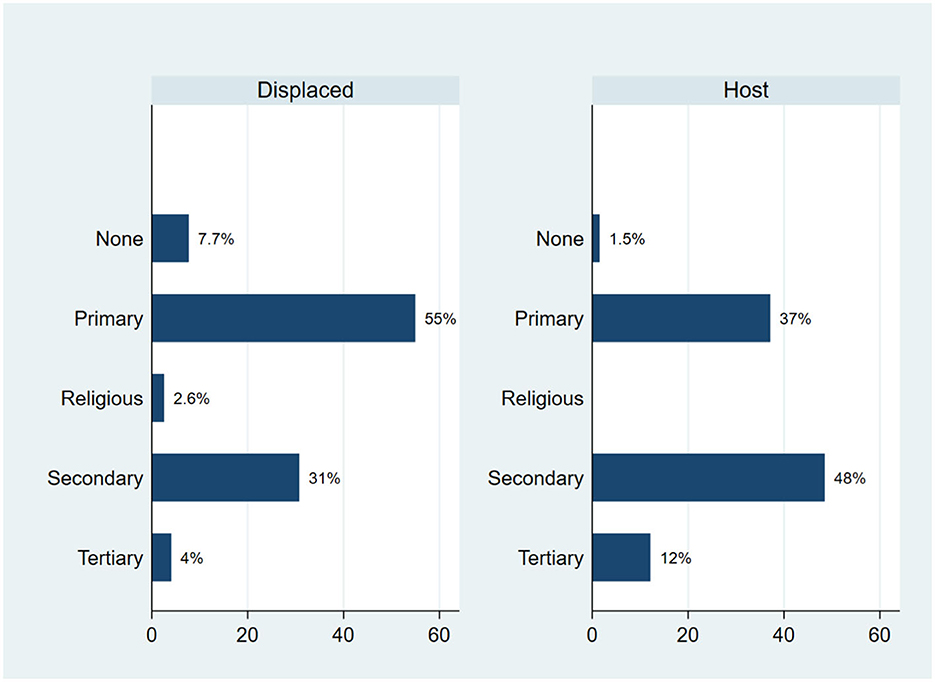

Education levels were higher among hosts, 98% of whom can read and write compared to 82% of refugee respondents. Figure 2 below shows the differences in education levels between hosts and displaced samples. Overall, the populations were similar, but the host population had slightly higher proportion of people who had completed secondary or tertiary education. Within the displaced population the majority (55%) had primary education only, 31% had secondary education and 4% tertiary education.

Demographically, our sample populations of displaced and hosts in Nairobi's informal settlements share many attributes. There are, however, notable differences in literacy, education and income.

Health and healthcare access

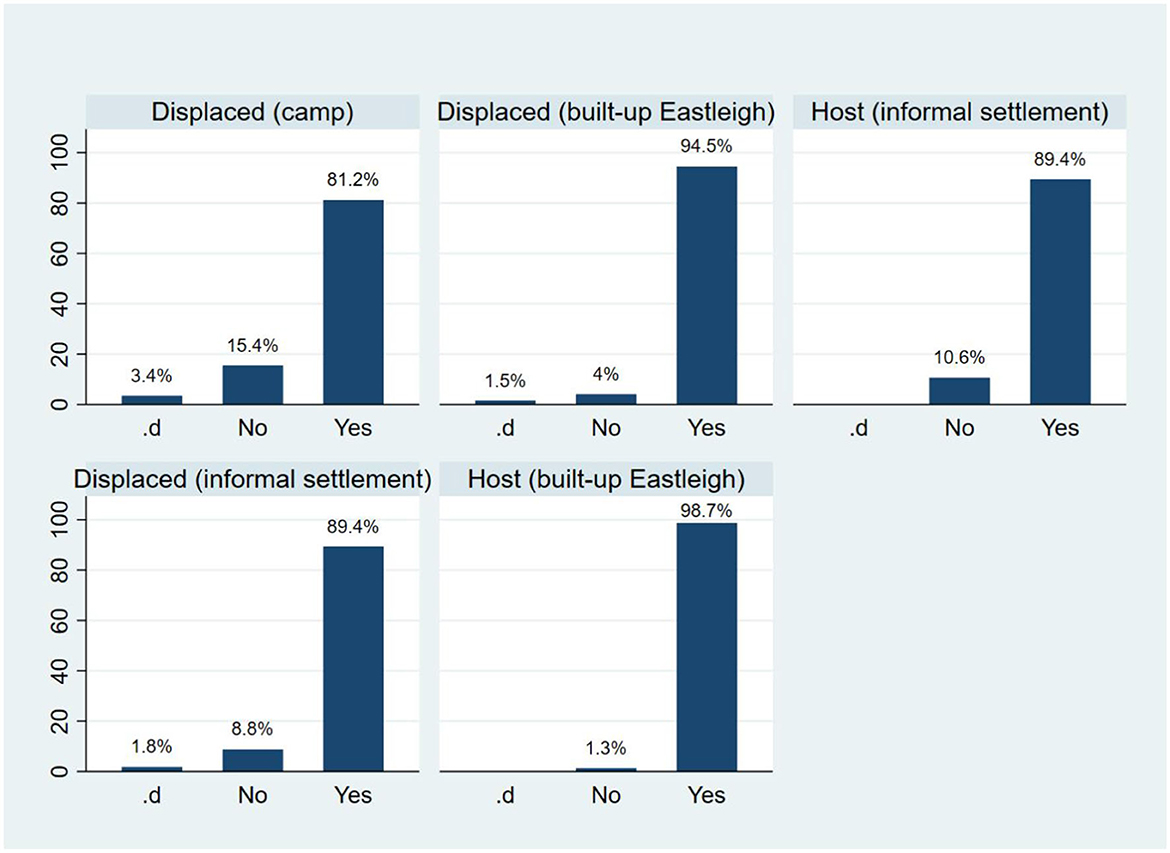

Examining the perceived quality of healthcare in Mathare and southern Eastleigh, we find that hosts generally rated their own health slightly better than displaced respondents. However, both displaced and host respondents reported similar results regarding healthcare quality and availability. Around 89% of both samples indicated that healthcare services were available to them.

To put these findings into a wider context, we compared the responses of displaced and host respondents in the informal settlements with our displaced respondents in Dadaab camp and displaced and host respondents in the built-up part of Eastleigh in Nairobi. Optimal health outcomes (categorized as good and very good) were most frequently reported among the hosts (83%) in built-up Eastleigh, followed by urban displaced respondents in built-up Eastleigh (80%), displaced in the camp (77%), hosts residing in informal settlements (70%) and, finally, displaced respondents in informal settlement (66%). These results are indicative of the additional challenges displaced and host residents face in informal settlements.

When asked about healthcare access (see Figure 3 above) hosts in built-up Eastleigh had a near perfect score with 98.7% stating they did have access to healthcare, while the rate in the informal settlement was 89.4%. Contrary to the built-up urban area where hosts were slightly ahead, healthcare access in the informal settlement was the same for host and displaced respondents, with a slightly higher number of hosts (10.6%) stating they did not have access to healthcare, compared to 8.8% of displaced respondents. 1.8% of displaced respondents stated that they did not know, which was a response shared by displaced populations across all locations but not expressed by any hosts.

As public healthcare access is connected to the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) we have investigated access to social protection an additional factor. Disparities between hosts and displaced respondents emerge here, where 29% of hosts in informal settlements stated that they had access to social protection, compared to only 7% of displaced respondents. This could indicate that people rely on non-profit clinics more than the public healthcare system.

This section examined different health indicators, such as the general state of health and access to health care, highlighting better outcomes for both hosts and displaced respondents living in the built-up parts of Eastleigh. This underscores additional challenges faced by both displaced and hosts in informal settlements. Disparities between hosts and displaced is particularly evident within social protection access, which could indicate further differences in access to public health insurance that are not reflected in the healthcare access findings, likely because of non-profit clinics.

Integrated vs external healthcare in Nairobi

In addition to the quantitative data on the population in informal settlements Mathare and Kiambiu or Eastleigh South presented above, this section provides qualitative key informant interview data on healthcare access for the displaced population in Nairobi, and a case study of a displaced person navigating care access.

In line with the survey findings showing little difference in healthcare access between displaced and host respondents in informal settlements, interview data shows that the displaced urban population in Nairobi appears to be able to access healthcare in an integrated manner regardless of any perceived temporality of their displacement to Nairobi or Kenya, which includes healthcare facilities located in informal settlements. For example, the Maternal Health Clinic in Eastleigh supports expecting families even if they are “transiting” from having prior antenatal care carried out at a different hospital and potentially also expected to also give birth somewhere else. A key informant (Interview 3) emphasized the importance of offering mothers a complete immunization profile regardless of whether the patient is expected to stay or not. In this respect, local service providers can in practice opt for supporting de-facto over partial integration despite the perception of displacement—and integration in Kenya—as temporary (Crawford et al., 2015).

However, this type of integration is dependent on resources, which are supplied by the government but not always sufficient for all urban residents, including both hosts and displaced. In such cases, international organizations can step in, but there are examples of where humanitarian systems—or, in this case, funding—that aim to work in partnership to support integration end up causing friction between displaced and local populations in Mathare and southern Eastleigh. The key informant (Interview 3) described a situation where drugs were provided to both displaced and host populations, but when the medication ran out for the host population first, there was a perception that the displaced population was receiving preferential treatment. There were also examples of the displaced population being provided with different types of medication subsidized by funding from UNHCR, which was worth more than what the government-funded medication host population was given. This resulted in disharmony between hosts and refugees and a resolution within this clinic to have the same medication accessible to all regardless of the funding agency. The key informant said: “imagine someone is a refugee in your own country and he or she is living a better life than you” (Interview 3).

This sentiment expressed by a service provider within an integrated healthcare system demonstrates that this type of integration can in practice offer limitations for displaced populations in terms of direct service access. In the context of local or de-facto integration, this means that integration outcomes and enablers (or markers and means) (Ager and Strang, 2008) are not necessarily always enabled by an integrated healthcare system. In this case, support from the external system would likely have provided a better health outcome (i.e., higher quality medication) for the displaced individuals, but the primary consideration should be enabling access to all populations without preferential treatment of one population over another.

The case study below continues to provide a nuanced example of what the interactions between these two systems can look like for a displaced person in need of healthcare in Nairobi.

Case study: navigating referral pathways

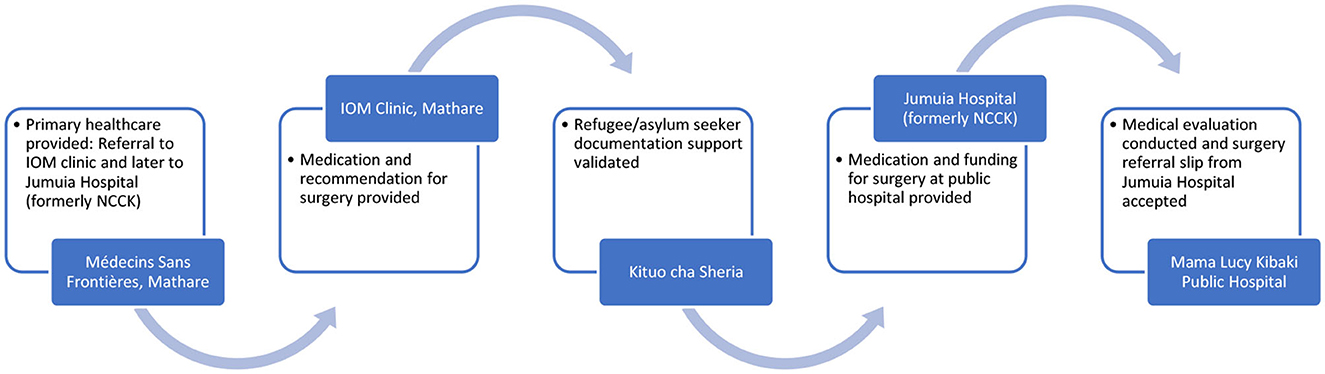

This case study describes the complicated patient journey for a displaced man living in the outskirts of Nairobi. He was registered with a private clinic in his area of residence but needed advanced treatment for a condition that had gone untreated for a long time during his displacement, caused him a lot of pain and prevented him from working. He did not have information about how to access treatments offered outside of his home clinic, and they were not offering support with the referrals he needed. Left with no information about where to access care, he turned to his network for support and reached NGOs providing healthcare for displaced people in Nairobi. Thus the long referral journey (see Figure 4) ensued.

In the first step of the process Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which serves both Eastleigh and the informal settlement Mathare offered an assessment of the patient's medical condition and provided free primary healthcare, which is within its organizational mandate for support for the urban population. MSF is focused on emergency care and does not require refugee or asylum seeker documentation in order to provide healthcare, since efficiency is a prime consideration. However, since this patient had been living with the condition for some time, it could not be categorized as an emergency case and MSF could therefore not support him any further. As a result, the patient needed a referral to a suitable medical facility. MSF referred him to an International Organization for Migration (IOM) clinic in Eastleigh, for further treatment.

At the IOM clinic, the patient was further assisted with medication for pain relief and recommended advanced treatment in the form of surgery, given the severity of his medical condition. No documentation was required at this stage either, but the IOM clinic was not equipped to provide the surgery and the patient was referred to Jumuia hospital (at the NCCK clinic) in Huruma. At this stage he required refugee or asylum seeker documentation, as one of Jumuia hospital's mandates is to provide services to registered urban refugees. The hospital is partially funded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to implement its urban refugee assistance programme. At this stage, MSF got involved again to obtain a contact at Jumuia hospital for medical referral.

Simultaneously involved, was Kituo cha Sheria, a legal advice center. A paralegal officer and refugee community leader residing in the same locality and in similar refugee networks as the patient assisted in drafting a letter of support for the patient, which ensured that he had the required urban refugee status and documentation. Once the patient acquired the necessary documentary proof with the help of the organization, he was able to seek free medical drugs and assistance at Jumuia hospital and a full funding commitment for his surgery, which was not covered by NHIF. To this end, his final referral by Jumuia was to Mama Lucy Kibaki public hospital in Nairobi for surgery.

As demonstrated by this journey, medical access in Nairobi and is based on referrals depending on the severity of illness. Healthcare facilities are at six levels in Kenya, with the first five managed at a county level and the sixth level managed by the national government. The system entails moving patients from one level to the next using referral letters. Public hospitals are usually the main referral option for other service providers within the referral pathway. This was highlighted by the key informant from MSF who said: “[W]e usually transfer these patients to government facilities, because one, we are looking at quality services and also affordability” (Interview 2). Similarly, the key informant from NCCK stated: “We have partnered with various hospitals, for example Kenyatta National Hospital, Mama Lucy, Mbagathi, German Medical Center, Kijabe, Kikuyu. So what do we do, we just refer our clients there, because we have an MOU with them” (Interview 1). These statements have also been supported by interviews conducted within other projects the authors work on in Nairobi, where refugees have shared experiences of being referred from NGOs to public service providers.

However, this journey also exemplifies a referral pathway that involves various stakeholders outside of the public healthcare system that urban displaced people are supposed to be integrated into. For a displaced patient, required paperwork is one example of a potential roadblock, as well as lack of information around access and rights among healthcare providers, as was the case at the patient's home clinic. In this case, the journey through referrals toward the required surgery was long and winding, involving public and private (non-profit) parts of the healthcare system, as well as non-medical practitioners. Importantly in relation to integration, it required the patient to utilize his own networks, which are not available to all displaced patients. Secondly, going through non-profit providers aimed at urban refugees took this patient to clinics in the informal settlements, despite living in a much wealthier part of the city and having access to private care.

While the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) is available to Nairobi's urban displaced, refugees and asylum seekers without documentation are unable to access medical services through these facilities and are instead required to pay for any care provided with cash. This undermines effective and efficient access as the challenge with insurance policies is the claim procedure normally after service provision. Without patient documentation therefore, medical institutions are unable to later on claim from the respective health fund. Refugee or asylum seeker documentation is therefore a key challenge.

A key informant (Interview 3) stated that there is a lack of clear guidelines from the government around how to serve refugees and asylum seekers, both with and without documentation. The way it is, they struggle to provide care efficiently, simply “because this is not a Kenyan” and it is difficult for them to know for example whether they can file patients within their systems, and how to effectively follow up with them. Even in institutions like MSF that do not require documentation from displaced patients to serve them still face challenges in cases that require referrals, which limits their ability to fully support patients.

Medical practitioners within clinics based in Mathare and Eastleigh also highlighted the need for full-time language interpreters and or translators to assist them in service delivery to displaced persons, for example in form of recruiting community health promoters with diverse language skills to aid the referral process between various medical institutions. Currently, the system is dependent on community volunteers and individual service providers with the right knowledge, which means displaced patients can be left hanging in case of staff turnover or even temporary holidays. The key informant described how colleagues might “give up along the way due to the lengthy process involved” (Interview 3) in for example referring a patient for immunization to MCH, which would require a referral from NCCK. At the moment, there is no service provider that offers help for displaced people to navigate the entire system and overcome barriers caused by language and documentation needs.

Conclusions

This article has discussed what integration means in the context of forced displacement. De-facto and partial integration models in particular, which are in reality the only options available in many countries (Jacobsen, 2001; Long, 2014), present problems with rights and documentation in order to access services. Further, in any context integration appears limited to reaching the same level of service access as local neighbors, which in the context of an informal settlement is extremely problematic.

Our case study has demonstrated that even with integrated care on paper, when push comes to shove and care is urgently needed, access for urban displaced people is not easy. In this case it required a range of actors to invest their time and engagement on behalf of a single case, which in the long run is not a sustainable system. Further, it is interesting to note that our patient was referred to care providers in Eastleigh and Mathare, the latter being an informal settlement where locals struggle the most with healthcare access. While documentation, information and language remain challenges specific to the displaced populations, it is worth asking whether a local living in the informal settlements, without networks of international organizations working on their behalf, would have been able to access the same care through the same clinics.

Medical sociology literature defines patient work as “patients' participation in their own care” (Strauss et al., 1982, p. 978). It seems, in this case, that the patient could work his way between the national healthcare system and the non-profit healthcare system provided for the urban displaced. While an extremely complicated referral process, it is entirely possible that these two systems together grant patients better outcomes than the public healthcare system alone.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: at the end of the project datasets will be made available to researchers via the UK's Reshare Data Archive. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Lucy Earle (Principal Investigator) lucy.earle@iied.org.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee within the Research Strategy Team, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

BM: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing, Methodology. SAH: Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft. JW: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper uses data collected within the UKRI GCRF funded (grant number ES/T004525/1) research project Out of Camp or Out of Sight? Realigning Responses to Protracted Displacement in an Urban World (PDUW). The project has received additional funds from the IKEA Foundation, the Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation (SDC), and the Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all research participants and interviewees who made this possible, and Lucy Earle for her thoughtful review of our early drafts.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^See Designated Areas within the Refugee Act (Government of Kenya, 2021).

2. ^See project website for more information: www.protracteddisplacement.org.

3. ^While numbers are difficult to confirm, see UNHCR's Global Trend Reports for estimates.

4. ^The original sample in Kenya consists of interviews with 382 displaced individuals in the Dadaab camp, 399 displaced in Nairobi and 156 hosts.

References

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J. Refugee Stud. 21, 166–191. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen016

Arnold, C., Theede, J., and Gagnon, A. (2014). A qualitative exploration of access to urban migrant healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya. Soc. Sci. Med. 110, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.019

Baillot, H., Kerlaff, L., Dakessian, A., and Strang, A. (2023). ‘Step by step': the role of social connections in reunited refugee families' navigation of statutory systems. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 49, 4313–4332. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2023.2168633

Baldi, G., and Goodman, S. W. (2015). Migrants into members: Social rights, civic requirements, and citizenship in Western Europe. West Eur. Polit. 38, 1152–1173. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1041237

Bellino, M. J., and Dryden-Peterson, S. (2018). Inclusion and exclusion within a policy of national integration: Refugee education in Kenya's Kakuma Refugee Camp. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 40, 222–238. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2018.1523707

Betts, A., Omata, N., Rodgers, C., Sterck, O., and Stierna, M. (2019). The Kalobeyei Model: Towards Self-Reliance for Refugees? Available online at: https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/the-kalobeyei-model-towards-self-reliance-for-refugees (accessed December 06, 2023).

Beversluis, D., Schoeller-Diaz, D., Anderson, M., Anderson, N., Slaughter, A., and Patel, R. B. (2017). Developing and validating the refugee integration scale in Nairobi, Kenya. J. Refug. Stud. 30, 106–132. doi: 10.1093/jrs/few018

Carrier, N. C. (2017). Little Mogadishu: Eastleigh, Nairobi's Global Somali Hub. Oxford University Press, New York.

City Population (n.d.). Mathare. Sub-county in Kenya. Available online at: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/kenya/sub/admin/nairobi/4708__mathare/ (accessed December 06, 2023).

Crawford, N., Cosgrave, J., Haysom, S., and Walicki, N. (2015). “Protracted displacement: uncertain paths to self-reliance in exile,” in Humanitarian Policy Group Report. London: ODI

Crisp, J. (2003). No solution in sight: the problem of protracted refugee situations in Africa. Refugee Surv. Quart. 22, 114–150 doi: 10.1093/rsq/22.4.114

Crisp, J. (2004). The Local Integration and Local Settlement of Refugees: a Conceptual and Historical Analysis. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR, 1–8.

De Falco, R. (2022). Patients or Customers? The Impact of Commercialised Healthcare on the Right to Health in Kenya during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Research report, The Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Available online at: https://gi-escr.org/en/resources/publications/the-impact-of-commercialised-healthcare-in-kenya doi: 10.53110/RPCN4627

Government of Kenya (2021). The Refugees Act, 2021. No. 10 of 2021. Available online at: http://kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/pdfdownloads/Acts/2021/TheRefugeesAct_No10of2021.pdf (accessed December 6, 2023).

Harrell-Bond, B. (1986). Imposing Aid: Emergency Assistance to Refugees. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 196

Home Office (2019). Home Office Indicators of Integration Framework 2019. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/627cc6d3d3bf7f052d33b06e/home-office-indicators-of-integration-framework-2019-horr109.pdf (accessed December 6, 2023).

Hovil, L. (2007). Self-settled refugees in Uganda: an alternative approach to displacement. J. Refug. Stud. 20, 599–620 doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem035

IOM (2013). A Study on Health Vulnerabilities of Urban Migrants in the Greater Nairobi. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM). Available online at: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/migrated_files/Country/docs/IOM-Urban-Migrants.pdf (accessed December 06, 2023).

Jacobsen, K. (2001). “The forgotten solution: local integration for refugees in developing countries,” in New Issues in Refugee Research. Available online at: http://www.unhcr.org/3b7d24059.pdf (accessed December 06, 2023).

Jacobsen, K., and Nichols, R. F. (2011). Developing a Profiling Methodology for Displaced People in Urban Areas: Final Report. Boston: Feinstein International Center.

Jemutai, J., Muraya, K., Chi, P. C., and Mulupi, S. (2021). “A situation analysis of access to refugee health services in Kenya: Gaps and recommendations-A literature review,” in CHE Research Paper. Heslington: Centre for Health Economics, University of York Working Papers, 178.

Long, K. (2014). “Rethinking durable solutions,” in The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Migration Studies, eds. E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, K. Long, and N. Sigona. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Muindi, K., and Mberu, B. (2019). Urban Refugees in Nairobi: Tackling Barriers to Accessing Housing, Services and Infrastructure. Available online at: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10882IIED.pdf (accessed December 06, 2023).

Mutisya, E., and Yarime, M. (2011). Understanding the grassroots dynamics of slums in Nairobi: the dilemma of Kibera informal settlements. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2, 197213.

NRC IHRC (2018). Supporting Kakuma's Refugee Traders: The Importance of Business Documentation in an Informal Economy. Available online at: https://hrp.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Business-Permit-Briefing-IHRC-NRC-1.pdf (accessed December 06, 2023).

Owiso, M. (2022). “Incoherent policies and contradictory priorities in Kenya,” in Forced Migration Review, 71–73. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/incoherent-policies-contradictory-priorities/docview/2724713831/se-2 (accessed December 06, 2023).

Rumbaut, R. G. (1997). Assimilation and its discontents: between rhetoric and reality. Int. Migrat. Rev. 31, 923–960. doi: 10.1177/019791839703100406

Rytter, M. (2018). Writing against integration: Danish imaginaries of culture, race and belonging. Ethnos 84, 678–697. doi: 10.1080/00141844.2018.1458745

Satterthwaite, D., Sverdlik, A., and Brown, D. (2018). Revealing and responding to multiple health risks in informal settlements in sub-Saharan African cities. J. Urban Health 96, 112–122. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0264-4

Slaughter, A., and Crisp, J. (2009). A Surrogate State?: The Role of UNHR in Protracted Refugee Situations. Geneva: UNHCR, Policy Development and Evaluation Service. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/media/surrogate-state-role-unhcr-protracted-refugee-situations-amy-slaughter-and-jeff-crisp (accessed December 06, 2023).

Strang, A. B., and Quinn, N. (2019). Integration or isolation? Refugees' social connections and wellbeing. J. Refugee Stud. 34, 328–353. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fez040

Strauss, A. L., Fagerhaugh, S., Suczek, B., and Wiener, C. (1982). The work of hospitalized patients. Soc. Sci. Med. 16, 977986.

UN-Habitat (2016). “UN-Habitat support to sustainable urban development in Kenya: addressing urban informality,” in Volume 4: Report on Capacity Building for Community Leaders. Available online at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/UN-Habitat%20SSUDK_%20Report_Vol%204_final.LowRes.pdf (accessed December 06, 2023).

UNHCR (2009). UNHCR Policy on Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban Areas. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/media/unhcr-policy-refugee-protection-and-solutions-urban-areas (accessed December 6, 2023).

UNHCR (2014). Policy on Alternatives to Camps. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/media/unhcr-policy-alternatives-camps (accessed December 06, 2023).

UNHCR (2022). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/global-trends-report-2022.pdf (accessed December 06, 2023).

UNHCR (2023). Projected Global Resettlement Needs 2023. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/media/2023-projected-global-resettlement-needs (accessed December 06, 2023).

UNHCR Kenya (2022). Multi-Year Strategy2023-2026 – Livelihoods and Economic Inclusion. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/unhcr-kenya-multi-year-strategy-2023-2026-livelihoods-and-economic-inclusion-june-2022 (accessed December 06, 2023).

Keywords: urban displacement, integration, healthcare, informal settlements, Nairobi

Citation: McAteer B, Alhaj Hasan S and Wanyonyi J (2023) A long and winding road of referrals: investigating the relationship between healthcare and integration for Nairobi's urban displaced. Front. Hum. Dyn. 5:1287458. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2023.1287458

Received: 01 September 2023; Accepted: 28 November 2023;

Published: 19 December 2023.

Edited by:

Clayton Boeyink, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomReviewed by:

Kumudika Boyagoda, University of Colombo, Sri LankaJeff Crisp, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 McAteer, Alhaj Hasan and Wanyonyi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Boel McAteer, boel.mcateer@iied.org

Boel McAteer

Boel McAteer Salam Alhaj Hasan2

Salam Alhaj Hasan2  Jackline Wanyonyi

Jackline Wanyonyi