Environmental Awareness Gained During a Citizen Science Project in Touristic Resorts Is Maintained After 3 Years Since Participation

- 1Marine Science Group, Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 2Fano Marine Center, The Inter-Institute Center for Research on Marine Biodiversity, Resources and Biotechnologies, Fano, Italy

- 3Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 4Centre for Biological Diversity, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom

Tourism is one of the largest economic sectors in the world. It has a positive effect on the economy of many countries, but it can also lead to negative impacts on local ecosystems. Informal environmental education through Citizen Science (CS) projects can be effective in increasing citizen environmental knowledge and awareness in the short-term. A change of awareness could bring to a behavioral change in the long-term, making tourism more sustainable. However, the long-term effects of participating in CS projects are still unknown. This is the first follow-up study concerning the effects of participating in a CS project on cognitive and psychological aspects at the basis of pro-environmental behavior. An environmental education program was developed, between 2012 and 2013, in a resort in Marsa Alam, Egypt. The study directly evaluated, through paper questionnaires, the short-term (after 1 week or 10 days) retention of knowledge and awareness of volunteers that had participated in the activities proposed by the program. After three years, participants were re-contacted via email to fill in the same questionnaire as in the short-term study, plus a new section with psychological variables. 40.5% of the re-contacted participants completed the follow-up questionnaires with a final sample size of fifty-five people for this study. Notwithstanding the limited sample size, positive trends in volunteer awareness, personal satisfaction regarding the CS project, and motivation to engage in pro-environmental behavior in the long-term were observed.

Introduction

Human ecological footprint is continuously increasing and human activities play a great role in environmental change, from climate change to pollution and biodiversity loss (Vitousek, 1997; Templado, 2014; Goudie, 2018). Among human activities, tourism is one of the largest economic sectors in the world with a remarkable long-term growth rate in the scale and value of international tourism (UNWTO, 2017; Sharpley, 2018). The year 2016 had the highest growth in worldwide international arrivals, with a total of 1,235 million tourists, 3.9% more than in 2015, and a revenue of US$ 1,220 billion (UNWTO, 2017). Overall, tourism is a multidimensional industry that impacts economy, society and the environment (Cooper, 2008; Carrillo and Jorge, 2017). The constant increase of tourism has determined positive impacts on the economic growth and expansion of many nations, specifically in developing countries (Durbarry, 2004; Lee and Chang, 2008; Dritsakis, 2012). However, it has also led to negative direct and indirect impacts on local ecosystems, such as habitat fragmentation, land, water and air pollution, and biodiversity loss (Saenz-de-Miera and Rosselló, 2014; Tang, 2015). For example, tourism is one of the causes of severe damages and stress of coral reefs, the most biodiverse marine ecosystems on Earth (Roberts et al., 2002; Shaalan, 2005; Davenport and Davenport, 2006; Taizeng et al., 2019). The construction and operation of touristic structures are often the cause of local degradation of coral reefs as a function of sedimentation, changes in shorelines, oil spills and increased production of waste (Shaalan, 2005; Sadeghian, 2019). Tourist activities also lead to direct reef damage due to inappropriate and careless behavior during snorkeling and scuba diving excursions (Hawkins et al., 1999; Betti et al., 2019).

Egypt, and in particular the Red Sea region, has undergone massive tourist development since the early 1990s. Between 2012 and 2016, more than 45 million international tourists entered the country, making tourism one of Egypt’s leading source of income, crucial to its economy. To help preserve the natural and cultural heritage, such a growing tourism sector should be managed and well-designed (UNWTO, 2017).

Sustainable tourism aims to respond to the negative effects of mass tourism on the environment by making optimal use of resources, maintaining essential ecological processes, and helping to conserve natural heritage and biodiversity (McKercher and Du Cros, 2003; Weaver, 2020). Sustainable tourism is not a particular kind of tourism but “an overriding approach to tourism development and management applicable to all the segments of the tourism industry” (Weaver, 2006). Sustainable tourism must guarantee responsible travel experiences to tourists and socio-cultural protection of the host country (Lansing and De Vries, 2007; Fennell and Cooper, 2020; Weaver, 2020). Within the concept of sustainable tourism, ecotourism is a trend in nature conservation and gives tourists the opportunity of learning about the environment while on vacation (Valentine, 1993; Fennell and Weaver, 2005; Wearing and Neil, 2009; Fennell, 2014). Ecotourism is a complex and synergistic collection of social, ecological and economic dimensions that reflect an ethics-based approach to tourism (Weaver, 2005), where the satisfaction of both conservation and tourism development is critical (Bjork, 2000; Blamey, 2000; Weaver, 2005; Donohoe and Needham, 2006; Fennell, 2014). A specific focus is on environmental education to emphasize the learning content of ecotourism (Kimmel, 1999; Bowers, 2003; Karol and Gale, 2005). There is growing support for an educational approach in ecotourism, which considers an immediate environmental improvement, but also addresses education for sustainability in the long-term (Tilbury, 1995; Steg and Vlek, 2009; Aikens et al., 2016). The Tbilisi Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education defined the main objectives of environmental education (Hungerford and Volk, 1990) as: (i) Awareness (to help groups and individuals acquire awareness and sensitivity to the environment and its allied problems); (ii) Knowledge (to help social groups and individuals gain a variety of experience in, and acquire a basic understanding of, the environment and its associated problems); (iii) Attitude (to help groups and individuals acquire a set of values and feelings of concern for the environment and motivation for actively participating in environmental improvement and protection); (iv) Skills (to help social groups and individuals acquire the skills for identifying and solving environmental problems); and (v) Participation (to provide social groups and individuals with an opportunity to be actively involved at all levels in working toward resolution of environmental problems). Environmental education promotes responsible citizenship behavior and increases awareness toward the environment and its related issues to minimize the negative impacts of human actions on the natural world (Hungerford and Volk, 1990; Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002; Steg and Vlek, 2009; Wals et al., 2014). Knowledge, particularly in the case of environmental issues, is a precursor to environmentally friendly behavior (Geiger et al., 2019). A study conducted among German and Argentinian college students showed that even though cultural background may have some influence, environmental knowledge is key to promoting pro-environmental behavior (Geiger et al., 2018). However, to achieve this behavior as the norm, the mere knowledge of the environment is not enough. Outdoor activities and educational programs have a stronger long-term effect and lead to a positive attitude toward the environment (Drissner et al., 2014).

The Citizen Science (CS) methodology integrates public outreach and scientific data collection (Brossard et al., 2005; Dickinson et al., 2012; Bonney et al., 2014). By directly involving volunteers in collecting data, CS can provide informal learning experiences and can be used as a tool for conservation in various ecosystems (Porter, 2004; Cooper, 2008; Bonney et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2014). For centuries citizens have recorded their observations of the natural world, including weather information, plant and animal distribution, astronomical phenomena and many others (Miller-Rushing et al., 2012; Bonney et al., 2014). Nowadays, millions of individuals, often not trained as professional scientists, participate in many authentic scientific research projects through data collection, categorization, transcription and analysis (Dickinson et al., 2012; Bonney et al., 2016; Hecker et al., 2018a, b). Today, most citizen scientists work with professional scientists on projects that have been specifically developed to let amateurs be part of the scientific process, while benefiting from an educational point of view (McKinley et al., 2017). Modern CS clearly differentiates from the historical form because now it is an activity potentially available for everyone, not just a privileged few (Silvertown, 2009). The huge explosion of CS projects is due to different factors such as: (1) the development of easily available tools for dissemination, information and engagement of the public (such as internet, smart phones, etc.); and (2) the increasing realization among scientists that the public represent a free source of work, skills and even finance (Silvertown, 2009). One of the first examples of modern CS projects is the Christmas Bird Count, developed in 1900 by the National Audubon Society in the United States and still ongoing every year (Meehan et al., 2019). Citizens now take part in projects on climate change, entomology, ecological restoration, conservation biology, invasive species, water quality monitoring, population ecology, public health etc. (Cooper, 2016; Grimm, 2017). Almost any project that seeks to collect large spatial and temporal data over a wide geographical area can only succeed with the help of citizen scientists (McKinley et al., 2017). There are different ranges of citizen participation in CS projects, from assisting with data collection and observations, to asking professional researchers to develop a specific research and participate in data analysis (Dickinson et al., 2012; Cooper, 2016; Grimm, 2017). CS combines research with public education, also addressing wider societal impacts by engaging citizens in authentic research experiences and in the scientific process (Bonney et al., 2009; Dickinson et al., 2012; Kobori et al., 2016).

A previous short-term study conducted within the CS biodiversity monitoring project “Scuba Tourism for the Environment” (STE), shows that right after participating in the Environmental Education (EnvEd) program, volunteers increased knowledge of reef biology and ecology, awareness of human impact on the environment, and intention to act in a more environmental-friendly manner (Branchini et al., 2015a). Previously published data for the short-term study were compared to those of the follow-up study presented here. In this research we analyzed, for the first time, the long-term effects of participation in the same CS EnvEd program, in terms of volunteer Knowledge and Awareness retention and effect of psychological variables (Satisfaction, Identification with the CS project, and Motivation to engage in pro-environmental behavior) on the learning process. In particular, we: (1) examined whether short-term scores of Knowledge and Awareness could predict their follow-up values; and (2) assessed the role of widely used psychological variables (José Sanzo et al., 2003; Farmer et al., 2007; Drissner et al., 2014) in maintaining higher scores of Knowledge and Awareness. We hypothesized that volunteers who strongly identified with the CS project, were very satisfied of the EnvEd program and had higher Motivation to engage in pro-environmental behavior would have higher Knowledge and Awareness scores in the follow-up.

Materials and Methods

This study was developed within the “Scuba Tourism for the Environment” (STE) project. STE was a CS project in which volunteers were invited to collect data on the status of the Red Sea coral reef biodiversity (Branchini et al., 2015b). The CS project was based in different marine coastal mass touristic resorts that are at the top of the hotel services of the Sharm El-Sheikh and Marsa Alam coasts (Egypt). The contact point for volunteers was a resident biologist involved in the project. Within the STE project, an environmental education (EnvEd, object of this manuscript) program was developed in 2012, in one resort at Marsa Alam (Figure 1). Upon arrival, tourists were informed about the possibility to participate in different activities with the biologist during their stay. Tourists interested in the EnvEd program took part in all the following activities, at least once for each:

Figure 1. Map of the Red Sea showing with a black star the location of the resort in Marsa Alam that hosted the EnvEd program.

• A weekly one-hour biology lesson focusing on the Red Sea, covering knowledge in basic reef biology and ecology of the coral reef, awareness of both natural and anthropogenic environmental pressures, and tips on how to minimize direct impact on the reef during marine recreational activities (scuba diving and snorkeling);

• Daily snorkeling excursions and scuba diving excursions with the biologist and the diving center of the resort;

• Daily contact with the biologist at the workstation at the beach for questions and discussions.

To verify the effects of participating in EnvEd program on volunteer reef knowledge and awareness, a questionnaire was created and provided to participants between 2012 and 2013 (see Branchini et al., 2015a). The intention was to continue the study for several years, but the Egyptian political situation led to a coup d’état in July 2013 and the closure of all tourist facilities in Marsa Alam. The short-term questionnaire contained three parts: (1) a section to collect personal and demographic volunteer data; (2) a section to evaluate the level of environmental education; and (3) a section with questions on knowledge of basic coral reef ecology and awareness about the human impact on the environment. Volunteers filled the aforementioned questionnaire twice: once at the beginning of their holiday, before participation in EnvEd program activities (T0), and again at the end of their stay (usually after 7–10 days), after having participated in the EnvEd program related activities (T1) (Branchini et al., 2015a). Biologists of the EnvEd program working in the resort provided the questionnaires directly to volunteers. To detect follow-up effects of the EnvEd program, another questionnaire (follow-up, T2) was created to evaluate the same questions observed in the short-term questionnaire (Figure 2), plus psychological questions about Satisfaction, Identification with the CS project, and Motivation to engage in pro-environmental behavior (Table 1). We relied on social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) and expectancy-value attitude model (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1980) to propose two psychological factors that can influence the learning process and acquisition of pro-environmental behavior related to the CS project, such as Identification and Satisfaction. The follow-up questionnaire was prepared with Qualtrics (Qualtrics, LLC, www.qualtrics.com) and sent out via email, between 2015 and 2016, to a subset of 212 volunteers who had previously compiled both short-term questionnaires (T0 and T1) and who had voluntarily agreed to give their email addresses to be re-contacted for future studies. EnvEd program, within the STE project, and its consent acquisition procedure have received the approval of the Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna (prot. 2.6). For this study, participants (or parents/guardians in case of minors) gave their consent by signing a declaration inserted in the questionnaires, and their personal data (name and surname) were collected in order to guarantee the comparison between the initial environmental education assessment and those after participation in project activities (short-term and follow-up). We have treated the data confidentially, exclusively for institutional purposes (art. 4 of Italian legislation D.R. 271/2009 – single text on privacy and the use of IT systems). Data treatment and reporting took place in aggregate form.

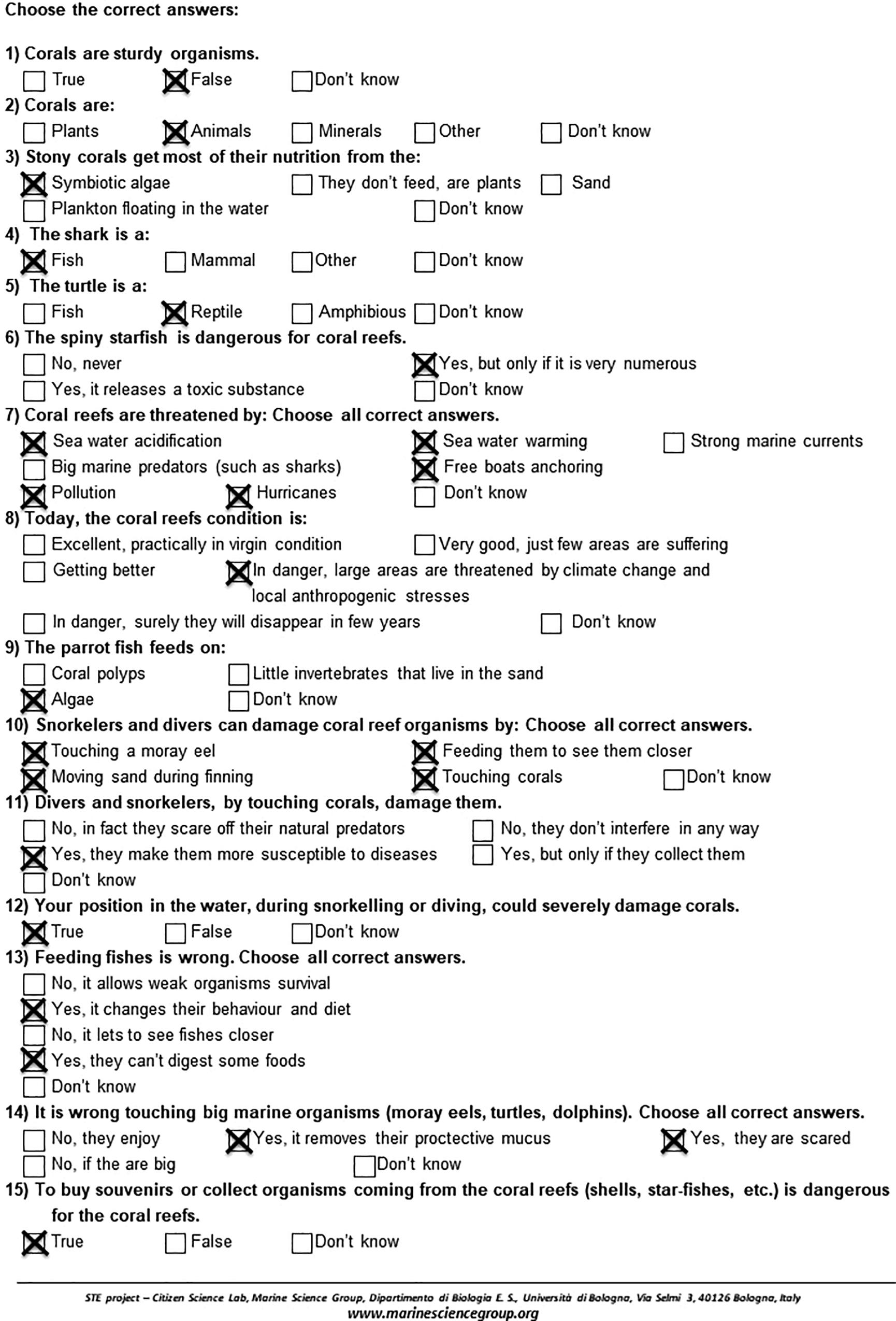

Figure 2. Environmental education evaluation questionnaire with highlighted answers. Figure modified from Branchini et al. (2015a).

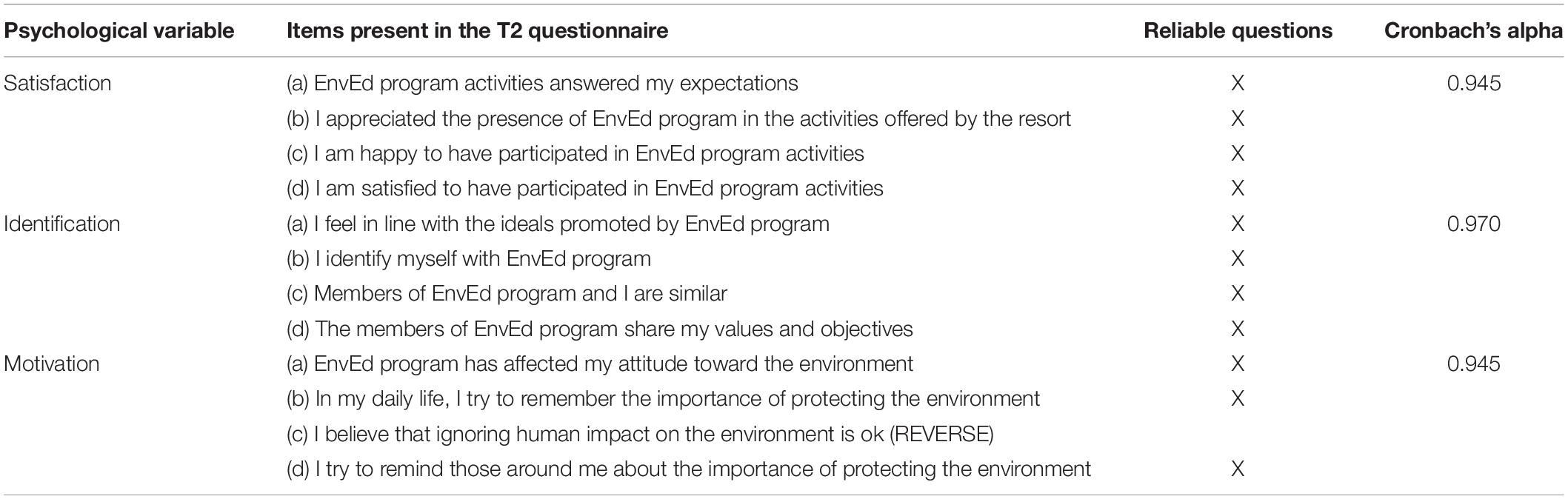

Table 1. List of psychological questions in the T2 questionnaire and those found to be reliable following the calculation of Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient.

Questionnaire Variables

The follow-up questionnaire consisted of three sections, the first two were the same of the short-term questionnaire.

The first section aimed to collect volunteer personal and demographic data to pair questionnaires compiled by the same participant over time.

The second section evaluated the level of environmental education. It contained 15 multiple-choice questions covering two kinds of issues. The first set of questions (nine questions, from number 1 to number 9) covered the Knowledge on basic coral reef biology and ecology. The second set of questions (six questions, from number 10 to number 15) dealt with the Awareness on the impact of human behavior on the environment. There was only one correct answer, except when explicitly stated. The second section was analyzed giving a score for each answer. To allow comparison with the previous short-term study, the score was calculated in the same rationale: negative if the answer was wrong, positive if it was correct and zero if it was “I don’t know.” The value of the score of each question was calculated so that the sum of all correct answers would be +1 and the sum of all the wrong answers −1 and then normalized in a scale from 1 to 10 (Branchini et al., 2015a).

The third section was unique to the follow-up questionnaire and evaluated three psychological variables (Table 1): level of Satisfaction in participating in EnvEd program, level of Identification with the CS project and Motivation to engage in pro-environmental behavior. Each variable value was assessed using sets of four sentences (items). Tourists were asked to score how much they agreed with each item ranging from one (not at all) to seven (very much) (Joshi et al., 2015). For the reverse sentence (item c for Motivation), we inverted score ranking. Scores were then normalized in a scale from 1 to 10.

Statistical Analysis

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normality and Levene’s test for the equality of variances were performed to check for normality and homogeneity of the variable variances. Cronbach’s Alpha was performed to check whether an average value for each psychological variable (Satisfaction, Identification and Motivation) could be used and be representative of all items. Standard bivariate Spearman’s correlations between all variable (T0, T1, and T2 Knowledge and Awareness, T2 Satisfaction, T2 Identification, and T2 Motivation) combinations were performed to detect the possible association between each variable. One-way Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to test the differences of Knowledge and Awareness among T0, T1, and T2. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 software.

Results

Between 2012 and 2013, 212 volunteers completed the short-term evaluation questionnaire twice: before (T0) and after (T1) participating in EnvEd program activities (Branchini et al., 2015a). Of those 212 volunteers, 148 left their email address and agreed to be re-contacted in the future: these volunteers were invited to complete the follow-up questionnaire (T2) online, 3 years after participation to the EnvEd program. Sixty volunteers [40.5%; 43 men (71.6%), 17 women (28.3%)] out of the 148, that had been re-contacted, completed the follow-up questionnaire online. Five volunteers were discarded because their follow-up questionnaire was erroneously filled. The most represented age group included 31–45-year-olds (n = 22, 40%), followed by 46 to 60-year-olds (n = 19, 34.5%), and 16–30-year-olds (n = 7, 12.7%). The groups under 15 years-olds (n = 3, 5.5%) and over 60 years-olds (n = 4, 7.3%) were the least represented. The level of education of the majority of volunteers was high school (n = 33, 60%). Nine volunteers (16.4%) had a bachelor’s degree and 13 (23.6%) had a master’s degree. Thirty-two (58.2%) volunteers were snorkelers, 16 (29.1%) were recreational divers and 7 (12.7%) were professional divers.

Reliability Analysis

Cronbach’s Alpha showed that an average value among items of two psychological variables (Satisfaction and Identification) was representative of each item. For the Motivation psychological variable, item c did not achieve the threshold of = 0.5 score and we decided to delete it because it was not reliable (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011) and use an average value as done for the other psychological variables (Table 1).

Correlational Analysis Between Knowledge, Awareness and Psychological Variables

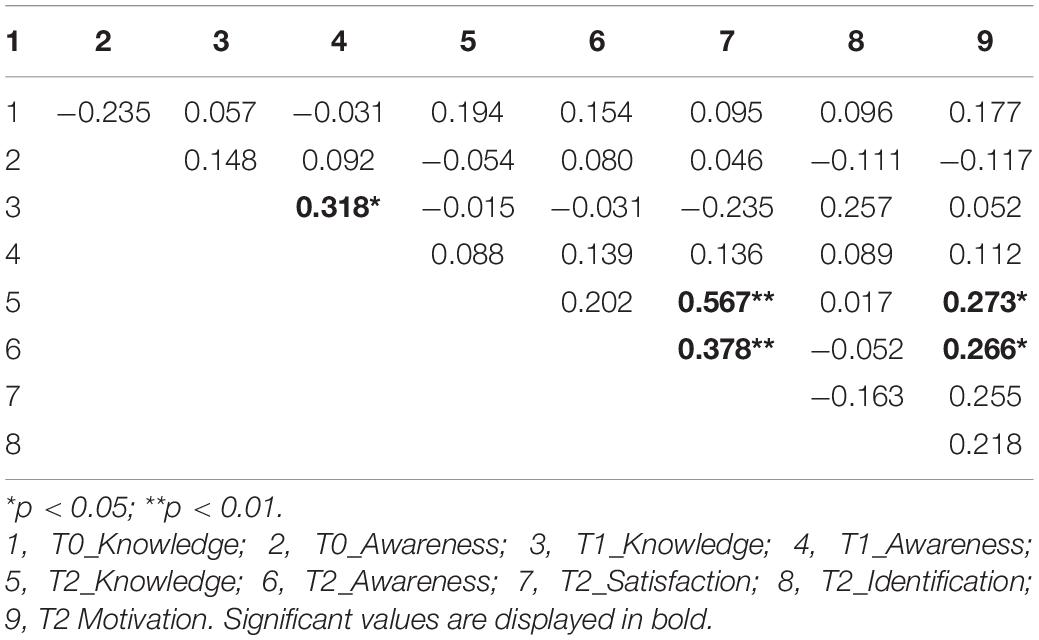

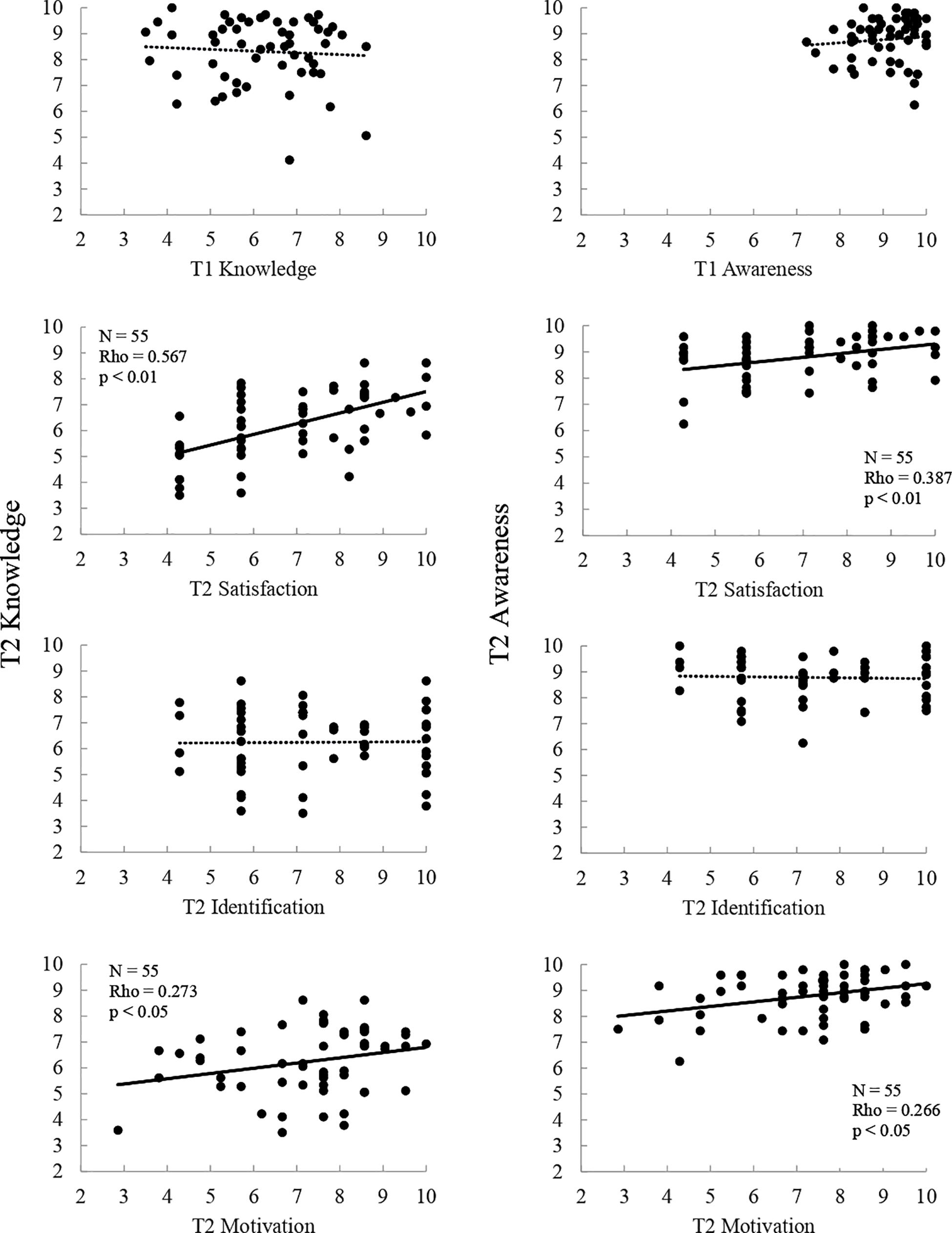

Table 2 and Figure 3 shows bivariate Spearman’s correlation coefficients for Knowledge, Awareness and psychological variables. Knowledge at T1 (right after participating to the EnvEd program) was positively correlated with Awareness on the impact of human behavior on the environment at T1 (rho = 0.318; p < 0.05). Both Knowledge and Awareness at T2 (after 3 years of participation in EnvEd program) correlated positively with Satisfaction toward participating in the project (Knowledge T2 rho = 0.567; p < 0.001; Awareness T2 rho = 0.378; p < 0.001) and Motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviors at T2 (Knowledge T2 rho = 0.273; p < 0.05; Awareness T2 rho = 0.266; p < 0.05).

Table 2. Bivariate Spearman’s correlation coefficients to evaluate significant correlations among variables (Knowledge, Awareness, Satisfaction, Identification, and Motivation).

Figure 3. Variation in long-term (T2) Knowledge and Awareness with short-term (T1) Knowledge and Awareness and psychological variables. Continuous black lines represent significant trends (see Table 2). Dotted black lines represent non-significant trends (see Table 2).

One-Way Analysis of Variance

Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance was conducted to test differences in volunteer scores of Knowledge and Awareness among T0 (before participation), T1 (right after the participation) and T2 (after 3 years). A significant difference was observed among times for Knowledge [χ2(2) = 65.754, p < 0.001], with lower volunteer Knowledge scores at T0 (Mean = 5.97, 95% CI 5.6–6.3) than at T1 (Mean = 8.31, 95% CI 8.0–8.6). Knowledge scores at T2 (Mean = 6.24, 95% CI 5.9–6.6) were significantly lower than those at T1. No significant differences were found between T0 and T2 Knowledge scores. Awareness scores showed a significant difference among times [χ2(2) = 16.501, p < 0.001], with lower Awareness scores at T0 (Mean = 8.42, 95% CI 8.2–8.7) than at T1 (Mean = 9.09, 95% CI 8.9–9.3) and T2 (Mean = 8.78, 95% CI 8.6–9.0). No significant differences were found between T1 and T2.

Discussion

This study is the first descriptive analysis of the long-term effects (after 3 years) of participating in a CS project on volunteer Knowledge about reef biology and Awareness about human impact on the environment.

Three years after participating in the EnvEd program, volunteers forgot their acquired Knowledge notions (Table 2). This suggests that volunteers can remember acquired information in the short-term (Branchini et al., 2015a), but not after several years. This result is not so astonishing because some notions may be forgotten after such a long period. As shown by previous studies, information processed in a “shallow” level and for a short period of time tends to be less remembered than the “deeper” ones (Craik and Lockhart, 1972; Cherney, 2008). However, several factors impact retention of knowledge, such as teaching technique, age of the subject, delay between study and the test (Willingham, 2012). Also, AOL (assurance of learning) theories suggest possible future improvement of the study trough a more engaging and targeted approach (Bechtold et al., 2018).

The environmental Awareness scores were significantly higher in the follow-up T2 compared to the short-term T0 that volunteers filled out before taking part in the project. The homogeneity between T1 and T2 Awareness scores result is crucial from an educational point of view because it means that the CS approach can improve volunteer awareness about pro-environmental attitude that could become an entrenched behavior (Chawla and Cushing, 2007). CS has the potential to bring change to volunteer cognition, defined as thoughts, beliefs, skills, and the like (Schunk, 2012).

This study analyzed, for the first time in a CS project, the follow-up relation between psychological variables (Satisfaction, Identification and Motivation) and cognitive variables (acquired Knowledge and Awareness). Obtaining high levels of volunteers Satisfaction and Motivation with the CS programs guarantees that the acquired personal Awareness is better maintained in the long-term (LaBarbera and Mazursky, 1983). This is a first example that participation in a CS project could be a valid tool to promote environmental education with effects that are maintained in the following years, as already demonstrated in other fields and with other methods (Hungerford and Volk, 1990; Tilbury, 1995; DiEnno and Hilton, 2005; Farmer et al., 2007; Drissner et al., 2014). Regarding psychological variables, recreational CS is likely to lead to higher levels of volunteers Satisfaction and Motivation, as project activities are engaging, simple and appealing to volunteers of all ages, gender, education level and diving experience (Meschini et al. submitted to Biological Conservation). To guarantee high levels of volunteer Satisfaction, and therefore lead to higher levels of Awareness and intention to behave eco-sustainably, activities should be accessible to many volunteers, entertaining and straightforward. In this study, we focused on three of the main objectives of environmental education as described in the Tbilisi Declaration (Awareness, Knowledge, and Attitude). These are the basis for achieving the other objectives: skill acquisition in environmental problem solving and increased environmental activism among individuals. Understanding the mechanisms behind successful environmental education is timely and much needed under the current climate circumstances.

Study Limitations

This study was supposed to last longer to increase sample size, but the Egyptian political situation led to a coup d’état in July 2013 and the closure of all tourist facilities in Marsa Alam made impossible to carry on the EnvEd program. Given that the involvement efficiency in a similar CS project (Goffredo et al., 2010) was between 10.1 and 8.5%, we estimate to have contacted between 2,099 and 2,494 volunteers in the site of the study during the 2 years of EnvEd program activities. Although it is quite low, the response rate of this study (40.5%) is in line with Baruch and Holtom (2008) and also with a review by Sheehan (2001), who found that throughout 31 studies over a period of 14 years, the average response rate was 36.83%. The limited sample size and the short period of time for this study prevents a broad generalization of the obtained results.

The recreational and voluntarily based nature of the project should also be considered, as participants might not be a reliable sample of the tourist population, because they were already interested and motivated to participate in such activities.

Another limitation of the present study is that psychological variables were only inserted in the follow-up questionnaire to further extend our understanding of the psychological processes that could be involved in the retaining of acquired knowledge and awareness, leading to a partial longitudinal study.

Moreover, given that the present study was pioneer regarding follow-up results of a citizen-science project, it was subject to design flaws. For example, due to the fact that the information required for re-contacting participants (e-mail address) was provided voluntarily, a smaller sample size than participants in T1 was expected (40.5% response rate in our study), since not all of the participants had an e-mail address or were willing to supply such information. Moreover, even those who provided their e-mail address might have not recognized the e-mail subject or sender address after 3 years, might have changed their address, or even make use of anti-spamming software that might prevent the questionnaire from arriving at the volunteer inbox (Saleh and Bista, 2017). To maximize the study response rate, the T2 questionnaire was sent by e-mail with two following reminder e-mails (that occurred after 1 and 2 months from the first e-mail) to the same subject but with the same object for the e-mail.

Nonetheless, the present approach is useful from a conservation point of view, and the aforementioned limitations could be addressed in future studies through different approaches, such as expanding the study over a longer period of time and preferably throughout multiple locations; increasing volunteer contacts, developing shorter questionnaires, sending personalized e-mail messages or even implementing deadlines to the completion of the questionnaires (Porter, 2004).

Conclusion

Tourism, with the range of activities it offers, can involve a lot of people and may be useful to address ecosystem conservation and protection issues. Our results suggest that by implementing a widespread use of CS and environmental education programs in resorts and in travel destinations that are popular because of their natural appeal, tourists could learn about the environment in an informal way, while developing awareness toward environmental issues and retaining it in the following years. Tourism could thus become more sustainable by creating lasting awareness changes, which could enhance a behavioral change. Furthermore, with a larger dataset, such outcomes can be of interest to tourism stakeholders which could increase their commitment and efforts towards environmental education programs. Sound environmental management practices can enhance competitiveness associated with travel destinations, and the destination commitment to the environment can influence the potential for sustained market competitiveness (Hassan, 2000). Future research should achieve a more robust sample size, focus on targeted approaches to analyze the follow-up retaining of Knowledge and also analyze whether such motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviors leads to environmentally responsible actions and behavioral modifications, with tangible positive effects on the environment.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna (prot. 2.6). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SG, SB, and VA developed the environmental education questionnaire within the “STE-project.” SG, SB, FrP, VA, VB, and CC collected data for the long term analysis. MM, EC, FiP, MMT, and CM analyzed the data. MM, FrP, EC, FiP, CM, VB, MMT, and GS wrote the manuscript. SG supervised the research. All authors have discussed the results and participated in the scientific discussion.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from Project AWARE Foundation, ASTOI Association, Milano, Ministry of Tourism of the Arab Republic of Egypt, Settemari S. p. A Tour Operator, Scuba Nitrox Safety International, Viaggio nel Blu Diving Center.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all our biologists who participated in the project. The research leading to these results has been conceived under the International Ph.D. Program Innovative Technologies and Sustainable Use of Mediterranean Sea Fishery and Biological Resources (www.FishMed-PhD.org). This study represents partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. thesis of MM.

References

Aikens, K., McKenzie, M., and Vaughter, P. (2016). Environmental and sustainability education policy research: a systematic review of methodological and thematic trends. Environ. Educ. Res. 22, 333–359. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1135418

Baruch, Y., and Holtom, B. C. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relations 61, 1139–1160. doi: 10.1177/0018726708094863

Bechtold, D., Hoffman, D. L., Brodersen, A., and Tung, K.-H. (2018). Assurance of learning and knowledge retention: do AOL practices measure long-term knowledge retention or short-term memory recall? J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 18, 10–21. doi: 10.33423/jhetp.v18i6.146

Betti, F., Bavestrello, G., Fravega, L., Bo, M., Coppari, M., Enrichetti, F., et al. (2019). On the effects of recreational SCUBA diving on fragile benthic species: the Portofino MPA (NW Mediterranean Sea) case study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 187:104926. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105105

Bjork, P. (2000). Ecotourism from a conceptual perspective, an extended definition of a unique tourism form. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2, 189–202. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-1970(200005/06)2:3<189::AID-JTR195>3.0.CO;2-T

Blamey, R. K. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism, ed. D. B. Weaver (Wallingford: CABI), doi: 10.1079/9780851993683.0000

Bonney, R., Cooper, C. B., Dickinson, J., Kelling, S., Phillips, T., Rosenberg, K. V., et al. (2009). Citizen science: a developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. Bioscience 59, 977–984. doi: 10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.9

Bonney, R., Phillips, T. B., Ballard, H. L., and Enck, J. W. (2016). Can citizen science enhance public understanding of science? Public Underst. Sci. 25, 2–16. doi: 10.1177/0963662515607406

Bonney, R., Shirk, J. L., Phillips, T. B., Wiggins, A., Ballard, H. L., Miller-Rushing, A. J., et al. (2014). Next steps for citizen science. Science 343, 1436–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1251554

Bowers, C. A. (2003). Mindful Conservatism: Rethinking the Ideological and Educational Basis of an Ecologically Sustainable Future. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Branchini, S., Meschini, M., Covi, C., Piccinetti, C., Zaccanti, F., and Goffredo, S. (2015a). Participating in a citizen science monitoring program: implications for environmental education. PLoS One 10:e0131812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131812

Branchini, S., Pensa, F., Neri, P., Tonucci, B. M., Mattielli, L., Collavo, A., et al. (2015b). Using a citizen science program to monitor coral reef biodiversity through space and time. Biodivers. Conserv. 24, 319–336. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0810-7

Brossard, D., Lewenstein, B., and Bonney, R. (2005). Scientific knowledge and attitude change: the impact of a citizen science project. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 27, 1099–1121. doi: 10.1080/09500690500069483

Carrillo, M., and Jorge, J. M. (2017). Multidimensional analysis of regional tourism sustainability in Spain. Ecol. Econ. 140, 89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.004

Chawla, L., and Cushing, D. F. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environ. Educ. Res. 13, 437–452. doi: 10.1080/13504620701581539

Cherney, I. D. (2008). The effects of active learning on students’ memories for course content. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 9, 152–171. doi: 10.1177/1469787408090841

Cooper, C. (2016). Citizen Science: How Ordinary People are Changing the Face of Discovery. New York, NY: The Overlook Press.

Craik, F. I. M., and Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verbal Learning Verbal Behav. 11, 671–684. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Davenport, J., and Davenport, J. L. (2006). The impact of tourism and personal leisure transport on coastal environments: a review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 67, 280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2005.11.026

Dickinson, J. L., Shirk, J., Bonter, D., Bonney, R., Crain, R. L., Martin, J., et al. (2012). The current state of citizen science as a tool for ecological research and public engagement. Front. Ecol. Environ. 10, 291–297. doi: 10.1890/110236

DiEnno, C. M., and Hilton, S. C. (2005). High school students’ knowledge, attitudes, and levels of enjoyment of an environmental education unit on nonnative plants. J. Environ. Educ. 37, 13–25. doi: 10.3200/JOEE.37.1.13-26

Donohoe, H. M., and Needham, R. D. (2006). Ecotourism: the evolving contemporary definition. J. Ecotourism 5, 192–210. doi: 10.2167/joe152.0

Drissner, J. R., Haase, H. M., Wittig, S., and Hille, K. (2014). Short-term environmental education: long-term effectiveness? J. Biol. Educ. 48, 9–15. doi: 10.1080/00219266.2013.799079

Dritsakis, N. (2012). Tourism development and economic growth in seven mediterranean countries: a panel data approach. Tour. Econ. 18, 801–816. doi: 10.5367/te.2012.0140

Durbarry, R. (2004). Tourism and economic growth: the case of Mauritius. Tour. Econ. 10, 389–401. doi: 10.5367/0000000042430962

Farmer, J., Knapp, D., and Benton, G. M. (2007). An elementary school environmental education field trip: long-term effects on ecological and environmental knowledge and attitude development. J. Environ. Educ. 38, 33–42. doi: 10.3200/JOEE.38.3.33-42

Fennell, D., and Cooper, C. (2020). Sustainable Tourism: Principles, Contexts and Practices. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Fennell, D., and Weaver, D. (2005). The ecotourium concept and tourism-conservation symbiosis. J. Sustain. Tour. 13, 373–390. doi: 10.1080/09669580508668563

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1980). Predicting and Understanding Consumer Behavior: Attitude-Behavior Correspondence. New York, NY: Prentice Hall Englewood Cliffs.

Geiger, S. M., Dombois, C., and Funke, J. (2018). The role of environmental knowledge and attitude: predictors for ecological behavior across cultures: an analysis of Argentinean and German students.Umweltpsychologie 22, 69–87.

Geiger, S. M., Geiger, M., and Wilhelm, O. (2019). Environment-specific vs. general knowledge and their role in pro-environmental behavior. Front. Psychol. 10:718. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00718

Goffredo, S., Pensa, F., Neri, P., Orlandi, A., Gagliardi, M. S., Velardi, A., et al. (2010). Unite research with what citizens do for fun: “recreational monitoring” of marine biodiversity. Ecol. Appl. 20, 2170–2187. doi: 10.1890/09-1546.1

Grimm, K. (2017). Importance of citizen science for science, individuals, communities, and the planet. Ecology 98, 3229–3230. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1987

Hassan, S. S. (2000). Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. J. Travel Res. 38, 239–245. doi: 10.1177/004728750003800305

Hawkins, J. P., Roberts, C. M., Van’t Hof, T., De Meyer, K., Tratalos, J., and Aldam, C. (1999). Effects of recreational scuba diving on Caribbean coral and fish communities. Conserv. Biol. 13, 888–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.97447.x

Hecker, S., Bonney, R., Haklay, M., Hölker, F., Hofer, H., Goebel, C., et al. (2018a). Innovation in citizen science – perspectives on science-policy advances. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 3:4. doi: 10.5334/cstp.114

Hecker, S., Garbe, L., and Bonn, A. (2018b). The European Citizen Science Landscape – a Snapshot. London: UCL Press, doi: 10.2307/j.ctv550cf2.20

Hungerford, H. R., and Volk, T. L. (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 21, 8–21. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1990.10753743

Johnson, M. F., Hannah, C., Acton, L., Popovici, R., Karanth, K. K., and Weinthal, E. (2014). Network environmentalism: citizen scientists as agents for environmental advocacy. Glob. Environ. Chang. 29, 235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.006

José Sanzo, M., Belén Del Río, A., Iglesias, V., and Vázquez, R. (2003). Attitude and satisfaction in a traditional food product. Br. Food J. 105, 771–790. doi: 10.1108/00070700310511807

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., and Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 7, 396–403. doi: 10.9734/bjast/2015/14975

Karol, J., and Gale, T. (2005). “Bourdieu’s social theory and sustainability: what is “environmental capital”? In doing the public good: positioning education research,” in Proceedings of International Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education 2004, Melbourne, Vic.

Kimmel, J. R. (1999). Ecotourism as environmental learning. J. Environ. Educ. 30, 40–44. doi: 10.1080/00958969909601869

Kobori, H., Dickinson, J. L., Washitani, I., Sakurai, R., Amano, T., Komatsu, N., et al. (2016). Citizen science: a new approach to advance ecology, education, and conservation. Ecol. Res. 31, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11284-015-1314-y

Kollmuss, A., and Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 8, 239–260. doi: 10.1080/13504620220145401

LaBarbera, P. A., and Mazursky, D. (1983). A longitudinal assessment of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction: the dynamic aspect of the cognitive process. J. Mark. Res. 20, 393–404. doi: 10.1177/002224378302000406

Lansing, P., and De Vries, P. (2007). Sustainable tourism: ethical alternative or marketing ploy? J. Bus. Ethics 72, 77–85. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9157-7

Lee, C. C., and Chang, C. P. (2008). Tourism development and economic growth: a closer look at panels. Tour. Manag. 29, 180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.013

McKercher, B., and Du Cros, H. (2003). Testing a cultural tourism typology. Int. J. Tour. Res. 5, 45–58. doi: 10.1002/jtr.417

McKinley, D. C., Miller-Rushing, A. J., Ballard, H. L., Bonney, R., Brown, H., Cook-Patton, S. C., et al. (2017). Citizen science can improve conservation science, natural resource management, and environmental protection. Biol. Conserv. 208, 15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.015

Meehan, T. D., Michel, N. L., and Rue, H. (2019). Spatial modeling of Audubon Christmas Bird Counts reveals fine−scale patterns and drivers of relative abundance trends. Ecosphere 10:e02707. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2707

Miller-Rushing, A., Primack, R., and Bonney, R. (2012). The history of public participation in ecological research. Front. Ecol. Environ. 10:285–290. doi: 10.1890/110278

Porter, S. R. (2004). Raising response rates: what works? New Dir. Institutional Res. 2004, 5–21. doi: 10.1002/ir.97

Roberts, C. M., McClean, C. J., Veron, J. E. N., Hawkins, J. P., Allen, G. R., McAllister, D. E., et al. (2002). Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295, 1280–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1067728

Sadeghian, M. M. (2019). Negative environmental impacts of tourism, a brief review. J. Nov. Appl. Sci. 8, 71–76.

Saenz-de-Miera, O., and Rosselló, J. (2014). Modeling tourism impacts on air pollution: the case study of PM10 in Mallorca. Tour. Manag. 40, 273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.012

Saleh, A., and Bista, K. (2017). Examining factors impacting online survey response rates in educational research: perceptions of graduate students. J. Multidiscip. Eval. 13, 63–74.

Shaalan, I. M. (2005). Sustainable tourism development in the Red Sea of Egypt threats and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 13, 83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2003.12.012

Sharpley, R. (2018). Tourism, Tourists and Society, 5th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. “Fourth edition published by Elm 2008.”: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315210407

Sheehan, K. B. (2001). E-mail survey response rates: a review. J. Comput. Commun. 6:JCMC621. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00117.x

Silvertown, J. (2009). A new dawn for citizen science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.017

Steg, L., and Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: an integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 29, 309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

Taizeng, R., Can, M., Paramati, S. R., Fang, J., and Wu, W. (2019). The impact of tourism quality on economic development and environment: evidence from mediterranean countries. Sustainability 11:2296. doi: 10.3390/su11082296

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds S. Worchel and W. G. Austin (Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall), 7–24.

Tang, Z. (2015). An integrated approach to evaluating the coupling coordination between tourism and the environment. Tour. Manag. 46, 11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.06.001

Tavakol, M., and Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Templado, J. (2014). “Future trends of mediterranean biodiversity,” in The Mediterranean Sea: Its History and Present Challenges, eds S. Goffredo and Z. Dubinsky (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 479–498. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6704-1_28

Tilbury, D. (1995). Environmental education for sustainability: defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environ. Educ. Res. 1, 195–212. doi: 10.1080/1350462950010206

UNWTO (2017). UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2017 Edn. Available online at: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419029 (accessed January 18, 2021).

Valentine, P. S. (1993). Ecotourism and nature conservation. A definition with some recent developments in Micronesia. Tour. Manag. 14, 107–115. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(93)90043-K

Vitousek, P. M. (1997). Human domination of earth’s ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.494

Wals, A. E. J., Brody, M., Dillon, J., and Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence between science and environmental education. Science 344, 583–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1250515

Wearing, S., and Neil, J. (2009). Ecotourism: Impacts, Potentials and Possibilities? Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Weaver, D. (2020). Advanced Introduction to Sustainable Tourism. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Pliblising.

Weaver, D. B. (2005). Comprehensive and minimalist dimensions of ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 32, 439–455. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.08.003

Keywords: citizen science, ecotourism, sustainable tourism, informal education, environmental education

Citation: Meschini M, Prati F, Simoncini GA, Airi V, Caroselli E, Prada F, Marchini C, Machado Toffolo M, Branchini S, Brambilla V, Covi C and Goffredo S (2021) Environmental Awareness Gained During a Citizen Science Project in Touristic Resorts Is Maintained After 3 Years Since Participation. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:584644. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.584644

Received: 17 July 2020; Accepted: 25 January 2021;

Published: 19 February 2021.

Edited by:

Sebastian Villasante, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Christian T. K-H. Stadtlander, Independent Researcher, Minneapolis, United StatesRichard Butler, University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Meschini, Prati, Simoncini, Airi, Caroselli, Prada, Marchini, Machado Toffolo, Branchini, Brambilla, Covi and Goffredo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesca Prati, francesca.prati@psy.ox.ac.uk; Stefano Goffredo, s.goffredo@unibo.it

Marta Meschini

Marta Meschini Francesca Prati

Francesca Prati Ginevra A. Simoncini1

Ginevra A. Simoncini1  Erik Caroselli

Erik Caroselli Fiorella Prada

Fiorella Prada Chiara Marchini

Chiara Marchini Mariana Machado Toffolo

Mariana Machado Toffolo Viviana Brambilla

Viviana Brambilla Stefano Goffredo

Stefano Goffredo