- China Institute of Boundary and Ocean Studies, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

Currently, the issue of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) has made a lot of significant progress in both international legislative process and national practices. As a State Party to UNCLOS, China has actively participated in the negotiations of the BBNJ agreement, in which the marine protected areas (MPAs) as one of the area-based management tools have been an issue of great concern. It is considered to be a feasible and direct conservation tool. In order to evaluate the possibility of China’s participation in the establishment of MPAs in the future, this paper analyzes the drivers for and limits on China’s involvement in the construction of MPAs in the context of the current Chinese situation. And it also puts forward possible countermeasures on how to deal with the challenges brought by the MPAs in ABNJ to China. It is concluded that there is a great possibility that China will eventually choose to participate in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ as China advocates the concept of a maritime community with a shared future.

1 Introduction

The ocean, which accounts for about 72 percent of the Earth’s surface, is of absolute importance to the future survival and development of human beings. The first multilateral international legal instrument related to the protection of the sea from human activities came in 1954, namely the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil, which marks the first decisive step taken by the international community in preventing global marine pollution. Since then, there have been some new multilateral conventions came out for the protection of the sea, such as the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter of 1972 (known as the London Convention), the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships of 1973 and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Under the regime of the UNCLOS, the ocean around the world could be divided into two categories, namely (1) areas within national jurisdiction (including internal waters, territorial sea, economic zone (EEZ), continental shelves and archipelagic waters of an archipelagic State), which constitutes 39% of the world oceans, and (2) areas beyond national jurisdiction (including the high seas and the Area) (UN, 1982). The UNCLOS attaches great importance to the protection of marine environment. It provides not only for the protection and preservation of the marine environment in its part XII comprehensively, but also for the conservation and management of the living resources in almost all maritime zones, such as Article 61 under part V of the EEZ, Article 119 under the part VII of the high seas and Article 145 under part XI of the Areas. However, these provisions are not sufficient to achieve the effective protection and management of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), a new and urgent issue arising from the rapid expansion of the breadth and depth of human exploration of the ocean. It is surprisingly found that only 1.18% of ABNJ have been protected in comparison with 17.86% protected waters within national jurisdiction (Protected Planet, 2022). Many experts and scholars have recognized that the status quo is inadequate (Verity et al., 2002; Rogers and Laffoley, 2013) and the international community needs to take further actions to protect the BBNJ (Brondízio et al., 2019).

In response to the need of a new legal instrument to fill in gaps in the international legal framework of protecting BBNJ, one of the most important international legislative processes in the field of the law of the sea is the negotiations held by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) of a legally binding international agreement on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in ABNJ (BBNJ Agreement), within the framework of the UNCLOS. There are four focused issues debated during the BBNJ Agreement negotiations, namely (1) marine genetic resources (MGR); (2) marine protected areas (MPA); (3) environmental impact assessment (EIA); and (4) capacity building and technology transfer (CBTT). Although the representatives of the parties involved in the negotiations have not yet agreed on the criteria for the establishment of marine protected areas, the discussions and discourses (Cárcamo et al., 2014) on the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) indicate that the implementation of MPAs can contribute to a better governance of BBNJ.

After reviewing the approaches of international community to the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ in Section 2, it points out that China has actively participate in the ongoing BBNJ Agreement under the guidance of the idea of a maritime community with a shared future for mankind. Since the establishment of MPAs is in line with the concept of a maritime community with a shared future, it is only a matter of time before China takes part in the practice. For this reason, the drivers and limits for China’s decision on participation in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ are analyzed in Section 3. Then Section 4 has proposed some possible solutions to deal with the challenges China may face when establishing MPAs in ABNJ. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 International community’s approaches to the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are effective tools for implementing ecosystem management, which can not only completely preserve the original appearance of marine resources and natural environment, but also protect, restore, develop, introduce and reproduce species communities, preserve the diversity of biological species, and eliminate and reduce adverse human effects (Gjerde et al., 2008). By the end of September 2022, there were 17786 marine protected areas in the world, accounting for about 8.15 per cent of the world’s total marine area. Among them, marine protected areas within national jurisdiction account for 17.86%, while protected areas on the high seas account for only 1.18% (Protected Planet, 2022). Notwithstanding, the low level of protection in ABNJ and the scarcity in quantity of MPAs therein cannot be a natural justification or rationality for the establishment. Let alone lots of controversies and criticisms concerning biological, physical, design, governance, legal and political issues are proposed when talking about MPAs as a conservation measure in relation to BBNJ (Wang, 2020). For instance, one of the design issues is the lack of data on the complexities of ecosystems in ABNJ (Game et al., 2009). Another controversial issue that is often discussed is the legal basis for MPAs beyond national jurisdiction (De Santo, 2018). However, with the development and progress in science and technology, some criticisms have been addressed and supporting evidences of MPAs as workable management tools for marine biodiversity conservation (Davies et al., 2017). Moreover, relevant experience generated in practices could also make contributions to solving these problems (Toonen et al., 2013). Furthermore, some international organizations, notably the UNGA, have been actively promoting the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in ABNJ by the establishment of MPAs (Rochette et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2016).

2.1 The currently existing practices of MPAs in ABNJ

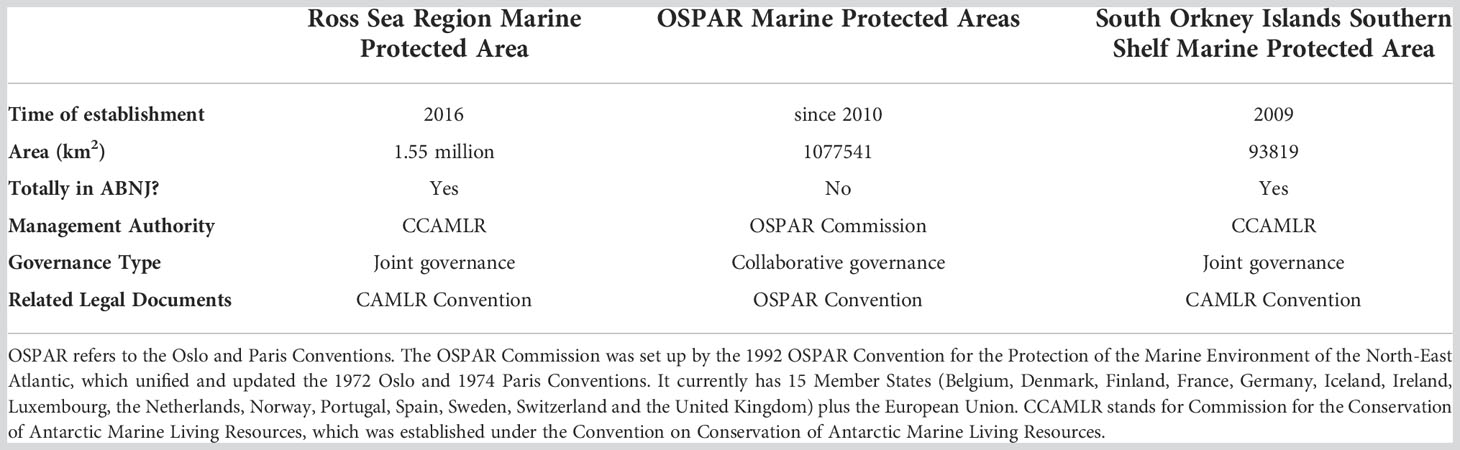

In recent years, the protection of the marine environment and biodiversity in ABNJ has attracted great attention at the global level, in particular in the context of the UNGA, the legal framework established by the UNCLOS and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). In this context, the practices of MPAs in ABNJ have been advanced. The first high seas MPA practice was the establishment of the Pelagos Sanctuary in the Mediterranean Sea in 1999. At the beginning of its establishment, it was once regarded as a MPA on the high seas because it includes some areas beyond national jurisdiction of France, Italy and Monaco. But with France’s declaration of the establishment of an EEZ in the Mediterranean Sea in 2012 (UN, 2014), there are no high seas in the Pelagos Sanctuary anymore. There are currently three existing MPAs in ABNJ around the world, namely, the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf MPA, the Network of North-East Atlantic MPAs and the Ross Sea Region MPA. The information of them is shown in Table 1 below. The Network of North-East Atlantic MPAs is expanding with more and more MPAs established. By the end of 2021 the OSPAR Network of MPAs comprised 11 MPAs situated in ABNJ (Hennicke et al., 2022). Experience we can learn from OSPAR MPAs practices is the collaborative approach applied by OSPAR Commission. OSPAR has cooperated with the other pertinent international competent authorities governing specific human activities in ABNJ, including the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), the International Seabed Authority (ISA), and the International Maritime Organization (IMO). For example, OSPAR and NEAFC adopted a collective arrangement regarding selected areas in ABNJ in the North-East Atlantic in 2014 (OSPAR, 2014). The advantage of this cooperation model is fruitful of solving the coordinating problems with other organizations by bringing all competent entities addressing the management of human activities in ABNJ together.

The Antarctic MPAs have developed rapidly in the past decade and still in progress. According to the planning of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine living Resources, more high seas protected areas will be established in Antarctica in the next 10 years. On the homepage of the CCAMLR MPA Information Repository (CMIR), three new MPAs were proposed on the list, namely the East Antarctic Representative System of MPAs (EARSMPA), the Weddell Sea Marine Protected Area (WSMPA) and Domain 1 Marine Protected Area (D1MPA) (CCAMLR, 2021). The discussions regarding the proposals to establish the MPAs are on-going. Some disagreement and controversy remain among the members of the CCAMLR in terms of legal regime, political issues, scientific basis, management, and monitoring, which are the major challenges in the development of Antarctic MPAs (Fu, 2019). Members and observers (including non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the fishing industry) as stakeholders are allowed to make comments on the proposals during the meetings. Once established, the coverage of Antarctic MPAs will increase significantly.

2.2 The ongoing negotiations on BBNJ Agreement

For ABNJ such as the high seas and the Area, states have no jurisdiction over these areas themselves. From the current practices of MPAs in ABNJ, the most direct legal bases for MPAs beyond national jurisdiction is regional treaties, such as the OSPAR Convention. However, unless the regional treaties are customary international law, the non-parties cannot be bound due to the principle of relative validity of treaties. The relevant provisions of existing international treaties such as the UNCLOS cannot provide direct and adequate norms of international law regarding the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ. In order to avoid the tragedy of the commons on the issue of protecting BBNJ, the international community needs to work together to develop a common legal framework.

In order to deal with the fragmentation of the protection and management of BBNJ, driven by European countries and some NGOs, the UNGA adopted resolution 59/24 in 2004 to establish an open-ended informal ad hoc working group devoted to the conservation and sustainable use of BBNJ (UNGA, 2004). This is of milestone significance to the construction of international regulation of BBNJ and starts the process of international legislation. The negotiation process can be roughly divided into three stages: (1) ad hoc working group (2004-2015), (2) preparatory committee (2016-2017) (UNGA, 2017) and (3) intergovernmental conference (2018-now).

In its resolution 72/249 of 24 December 2017, the UNGA decided to convene an Intergovernmental Conference to consider the recommendations of the Preparatory Committee established by resolution 69/292 of 19 June 2015 (UNGA, 2015) on the elements and to elaborate the text of an international legally binding instrument under the UNCLOS on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of ABNJ, with a view to developing the instrument as soon as possible (UNGA, 2018). In accordance with resolution 72/249, measures such as area-based management tools, including MPAs, belong to one of the four topics identified in the package agreed in 2011, which will be addressed in the intergovernmental conference. The intergovernmental conference had held five sessions until now. The fifth session was convened from 15 to 26 August 2022 and issued “Further revised draft text of the BBNJ Agreement” (hereinafter the “fifth draft text”) (UNGA, 2022).

The negotiation process has made important progress, resulting in a relatively complete draft text of the BBNJ agreement with annexes, countries have made substantial progress on the issue of area-based management tools, including MPAs. The negotiation goal of discussing area-based managements tools, including MPAs, under BBNJ is not to establish a corresponding protected area regime immediately, but to provide a framework between principles and measures for the future selection of MPAs in ABNJ. The discussion of area-based management tools, including MPAs, mainly focuses on five aspects: (1) the objectives of the measures including MPAs; (2) whether disputed areas should be included in MPAs; (3) the indicative criteria for the identification of areas requiring protection; (4) rights of adjacent states (Scott, 2019); and (5) management models (Berry, 2021). The “environmentalists” represented by the European Union, Australia and New Zealand called for the negotiation of the BBNJ international agreement to be completed as soon as possible to build up the construction of MPAs.

What’s more, other international instruments like FAO and CBD also play an indispensable role in the implementation of the relevant resolutions of the UNGA regarding BBNJ. For example, the FAO adopted Deep-sea Fisheries Guidelines in 2008 (FAO, 2009). The Guidelines provide not only the criteria for identifying vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs), but also the detailed suggestions for actions to take for VMEs, which could be useful references for the identification of MPAs. And the CBD has always been active in promoting the protection of marine biodiversity. Early in 2010, the Conference of the Parties (CoP) of the CBD adopted 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Among them, Target 6 and Target 11 are of particular relevance to the conservation of marine life (Dunn et al., 2014). At the same time, describing and identifying special places in the ocean has been the core focus of the work under the CBD on ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs) (CBD). In an effort spanning more than a decade, the CBD has basically completed the description of EBSAs in global sea areas, including more than 70 ABNJ, providing scientific and technological reserves for the selection of MPAs on the high seas (CBD, 2021).

The establishment of MPAs is strongly supported at the institutional and awareness levels. Large high sea MPAs, for instance, are thought to be a crucial instrument for achieving the aforementioned Aichi Targets (CBD, 2020). Notably, there has been consent in the ongoing BBNJ negotiations that “measures such as area-based management tools, including marine protected areas” shall be one of the draft text’s essential components (UNGA, 2017). Countries are ready to engage in substantive negotiations on the subject matters as the negotiations for the binding instrument of ABNJ arrive at a crucial stage. Based on the draft texts, the discussion of MPAs is becoming more concentrated and in-depth. Additionally, MPAs in ABNJ will be practiced more and more in the future.

China, which promotes the concept of a maritime community with a shared future, aspires to engage constructively to both lawmaking process and state practice. China has long supported the preservation and sustainable usage of BBNJ as a responsible maritime power, despite the fact that it has not yet taken part in the procedures of creating MPAs in ABNJ. China has so far continued to contribute positively to the negotiating process of the intergovernmental conferences with the goal of advancing the pragmatic formulation of the BBNJ agreement.

3 Drivers and limits for China to establish MPAs in ABNJ

The establishment of MPAs in ABNJ has resulted in significant advances in both practice and legislation. According to the fifth draft agreement’s currently published text, some of the provisions on MPAs are forward-looking. In order to provide useful information for Chinese policy makers and make China’s viewpoints better understood by others, this section analyzes the drivers for and limits on China’s potential involvement in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ in the context of the current Chinese situation.

3.1 The drivers

Three factors, including ensuring interests to marine resources, fostering marine scientific research, and strengthening participation and contribution to global governance, comprise the positive motivations for China’s engagement in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ.

3.1.1. Ensuring interests to marine resources

There are numerous important resources in the nearly two-thirds of the ocean that lie beyond national jurisdiction. For instance, ABNJ are home to a substantial amount of biodiversity, including rare species that have adapted to endure harsh temperatures, low humidity, high salinity, high pressure, and darkness (IUCN, 2022). These resources play a crucial strategic role in the long-term growth of human society and the economy. From the provisions of part III of the fifth version of the draft agreement on “measures such as area-based management tools, including marine protected areas”, the objectives of establishing MPAs include not only the promotion of BBNJ conservation, but also their sustainable use. According to Article 17, parties making proposals for the establishment of MPAs shall include “a description of the specific conservation and sustainable use objectives that are to be applied to the area” in the submissions. It is not only an obligation but also a right of the State party that made the proposals, because it will directly affect the way of utilization of marine resources in the MPAs. The State parties can convey in the proposal the needs their nation has for pertinent marine resources and strike a balance between conservation and utilization in the process of managing the MPAs.

Furthermore, humans will be more and more reliant on marine resources as land resources are depleted. The protection of BBNJ benefits the protection of marine interests like biological resources within national jurisdiction because of the ocean’s openness and connectivity. A healthy ocean is vital to human beings, which could regulate the climate, provide food and health resources, and drive economic growth (NOAA, 2021). China’s national interests are closely related to the sea. China’s marine gross domestic product (MGDP) surpassed 9 trillion yuan for the first time in 2021, contributing 8% to national economic growth, and the percentage of MGDP in GDP has remained at around 9% over the past 20 years, according to the “China Marine Economic Statistics Bulletin 2021” published by the Ministry of Natural Resources of People’s Republic of China (MNRPRC) (MNRPRC, 2022). In particular, as the three main pillars of the marine economy, coastal tourism, maritime transportation, and marine fisheries, respectively, account for 44.9%, 21.9%, and 15.6% of the added value of the core marine industries (MNRPRC, 2022). The sustainable development of these industries is inseparable from a healthy and resilient marine ecological environment. The construction of MPAs in ABNJ is thought to be an effective instrument to ensure the health and sustainability of the ocean. Therefore, it is of great significance to safeguard China’s marine resource interests in order to realize the efficient conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity through the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ.

3.1.2. Promoting marine scientific research

From the current discussion on BBNJ and MPAs, the establishment and management of protected areas on the high seas are closely related to marine science. First of all, before the MPA is established, the selection of location of the MPAs should be based on scientific data. Article 17 bis in the fifth revised draft text of BBNJ agreement provides that “areas ... should be identified: (a) on the basis of the best available science and scientific information ...; (b) By reference to one or more of the indicative criteria specified in annex I.” (UNGA, 2022) It is worth noting that the content of the annex I is highly similar to that of annexes II and III adopted in resolution IX/20 of the CoP to the CBD in 2008 (CBD, 2008). These indicative measures need to be based on marine scientific research. This implies that States parties proposing the establishment of protected areas need to conduct scientific research on selected areas and collect data to support their proposals. Secondly, further advancing ocean science and technology, and ensuring a robust science-policy interface are critical to achieving sustainable ocean management (UN, 2021). The management and monitoring after the completion of the establishment of MPAs also needs the corresponding investment in science research and technology innovation. According to the Article 12 about monitoring and review in the fifth revised draft text of BBNJ agreement, decisions on the amendment, extension or revocation of MPAs and any related measures should be based on “the best available science and scientific information” (UNGA, 2022). This clear legal demand for scientific research will stimulate the expansion of domestic marine research to marine areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Finally, two of the objectives of part II (marine genetic resources, including questions on the sharing of benefits) of the BBNJ agreement are to “build and develop the capacity of developing State Parties to utilize marine genetic resources of ABNJ” and to “promote technological innovations by promoting and facilitating the development and conduct of marine scientific research in ABNJ” (UNGA, 2022). Article 10 of this section also specifically refers to opportunities for scientists from developing countries to be involved in or associated with the project. Besides, the objectives of part V (capacity-building and transfer of marine technology) also include the support for developing State Parties through capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology, which would help them develop, implement, monitor, manage and enforce area-based management tools, including marine protected areas. Therefore, as a developing country, China currently lags behind developed countries in marine scientific knowledge and core technologies relating to deep-ocean and other areas for decades. China’s active participation in the construction of high seas protected areas will provide a rare opportunity for the accelerated development of domestic marine scientific and technological innovation by stimulating the potential of innovation and strengthening cooperation with developed countries in BBNJ. Then China’s enhanced marine scientific and technological capabilities will contribute to the upgrading of China’s domestic marine industry and promote the conservation and sustainable development of the ocean, which forms a virtuous circle.

3.1.3. Making China’s contributions to global ocean governance

Global ocean governance needs international cooperation and coordination. China is a big marine country, and global marine governance needs China’s participation. Due to the interconnection of the ocean, China would be affected by the global marine condition in terms of marine ecosystems, ocean development, and ocean management activities. China needs to safeguard its national interests by participating in global ocean governance. China is a permanent member of the UN and a State Party to the UNCLOS. China firmly supports the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and China actively implements its obligation to protect the marine environment under the UNCLOS.

China has always advocated the concept of a community with a shared future for mankind. A community with a shared future for the ocean refers to a collective formed by people under certain common conditions, or a unified organization or similar organization formed in the marine field by a number of national and non-state actors based on common marine interests or values. Its goal is to achieve the harmonious co-existence of ocean and people, to build a peaceful, cooperative and harmonious ocean and marine order, so that the ocean will become the common wealth of peace, development, cooperation and win-win results for all mankind. This concept can inspire the subjects of global ocean governance to pay more attention to the overall interests of mankind and the healthy development of the ocean while paying attention to their own interests (Jin, 2021). It is argued that the concept on maritime community with a shared future, as a specific reflection of the concept “a community of shared future for mankind” in maritime domain, could guide the BBNJ negotiations and assist in addressing the challenges arisen from BBNJ negotiations (Shi, 2022). The concept of a maritime community with a shared future is consistent with the goals contained in the upcoming BBNJ agreement, both of which “desire to promote sustainable development and aspire to achieve universal participation” (UNGA, 2022). The concept of a maritime community with a shared future is also the guiding ideology to promote China’s participation in global marine governance (Duan and Yu, 2021), including the approaching establishment of MPAs in ABNJ (Xue, 2021).

Participation in global ocean governance includes not only the construction of a global ocean governance framework, but also the participation in the national practice of global ocean governance. At present, the negotiations on the BBNJ agreement are coming to an end, and China has actively made suggestions and played a positive role in promoting the negotiations. When the time is ripe in the future, China should continue to enhance its participation in global ocean governance by participating in the construction of relevant marine protected areas. That’s a feasible way for China to make its own contributions to the global ocean governance as a responsible large nation.

3.2 The limits

Notwithstanding these motivations for China the actively participate, there are still some restrictive factors that China has to consider before it chooses to take practical actions.

3.2.1. The negative impact on domestic pelagic fishery

The freedom of fishing is one of the traditional freedoms on the high seas. In recent years, the freedom of fishing on the high seas has shown a trend of being restricted. A well-known example is that the 1995 Fish stocks Agreement restricted the fishing of straddling and highly migratory species on the high seas. The establishment of high seas protected areas is likely to make the freedom of fishing on the high seas a thing of the past. In high seas protected areas, the range of fishing species that are restricted or prohibited may be expanded, and “sea closure” measures may even be implemented in some marine areas. In view of the restrictive effect on the traditional high seas fishing rights, some countries regard the high seas protected areas as a threat to the fishing freedom. It is considered that the high seas protected areas will impose certain restrictions on the fishing carried out by the relevant countries on the high seas (Xu, 2015).

Fishery is an important industry of China’s national economy and an important part of China’s agricultural and rural economy. As an important part of China’s fishery, pelagic fishing is of great significance for China to safeguard the supply of agricultural products and national food security, as well as to increase fishermen’s income and promote employment. China’s pelagic fishing began much later than other big fishing countries. China has not utilized the high seas fisheries resources to seek benefits for its people until 1985 that China National Fisheries Corporation sent the first high sea fishing fleet, which was composed of 13 fishing vessels and 223 crew members (Liu, 2019). After more than 30 years of efforts, China’s pelagic fishery has formed an industrial scale. According to statistics in 2020, the total output and output value of pelagic fishery in China are about 2.32 million tons and 23.92 billion yuan respectively, and the number of operating offshore fishing vessels has reached more than 2700 (Wang and Wu, 2021). The overall size of the fleet and the output of pelagic fishing are among the highest in the world.

From the existing practice of the MPAs in ABNJ, the conservation measures adopted by the relevant regulatory agencies generally impose restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas. For example, there is a “no take” General Protection Zone (GPZ), where no commercial fishing is permitted in the Ross Sea region MPA (MFAT, 2022). The establishment of effective protected areas means that certain areas are designated as “no-catch zones”, which is bound to affect existing fishing activities on the high seas to some extent. From the perspective of short-term benefits, the fishery benefits available to the domestic pelagic fishing industry are bound to be adversely affected. But in the long run, studies have shown that, MPAs in ABNJ will in general not harm high seas fisheries and will benefit global fisheries, including high seas fisheries (Zhou, 2020). However, protected areas do bring about a redistribution of fishing production, from which the fleets of some countries may benefit and those of some countries may face losses. Thus, the exact impact on China’s pelagic fishing industry needs further research and data support.

3.2.2. The restrictions on activities in the Area

According to the Article 1(4) of the fifth draft text of the BBNJ agreement, “areas beyond national jurisdiction” means the high seas and the Area. While under Article 1(1) of the UNCLOS, “Area” means the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction; and “activities in the Area” means all activities of exploration for, and exploitation of, the resources of the Area, which includes all solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources in situ in the Area at or beneath the seabed, including polymetallic nodules. From the perspective of geographical location, there is a geographical combination between the high seas protected areas and the Area. The primary body of the waters adjacent to the Area belongs to the high seas, despite the fact that the resources therein as a whole are subject to the jurisdiction and control of the system of the Area under the UNCLOS. In order to prevent the emergence of a high seas biodiversity protection system that is in conflict with the “Area” current system, the ISA has made it clear that it would like to serve as the appropriate forum for enhancing international cooperation for protecting the high seas submarine biodiversity.From the practice of the current construction of protected areas, the protection measures adopted by the management organizations generally include navigation control, scientific research activities control and pollutant discharge control. If the exploration area where exploration activities carried out coincides with the high seas protected area, then the activities involving maritime navigation, resource exploration, waste discharge and other activities carried out in the Area may be restricted and managed by the regime of the MPAs. As a result, the creation of MPAs in ABNJ will impose some limitations on the development activities in the Area.

As the world’s population and productivity continues to grow, resources are more and more important to human society. After years of exploitation, land resources have been gradually exhausted inevitably, and marine resources have become the focus of exploitation. For China, the international seabed area is of vital importance as the source of strategic resources (Yang and Liu, 2019), because the domestic supplies of necessary mineral commodities have failed to meet the requirements of economic development. The development of the international deep sea-bed can not only enable China to obtain a large number of non-renewable mineral resources and achieve obvious economic benefits, but also enable China to make great progress in the field of marine science and technology. China has been conducting deep sea-bed activities since the 1980s. It signed an exploration contract with the ISA and has obtained a mining zone block of 75000 square kilometers in the Pacific sea-bed (Zou, 2003). China has carried out resource exploration and research on relevant blocks, invested in the research and development of deep-sea mining technology, applied to the ISA for the acquisition of deep-sea mining blocks and signed exploration contracts (Yang and Liu, 2019). Once the MPAs are formed, its conservation measures may have a restrictive effect on the activities in the relevant Area which may increase the technical difficulty and investment cost of deep-sea mining.

3.2.3. The deficiencies of relevant domestic legal resources

The construction of MPAs in ABNJ may bring challenges to China’s legal resources from three aspects: First of all, it may affect domestic legislation. On one hand, the current domestic legislation on biodiversity protection and nature reserves is not perfect. Laws and regulations such as the Marine Environmental Protection Law of the people’s Republic of China and the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves, both revised in 2017, which cannot be applied directly to MPAs in ABNJ, may need revision in consideration of the consistency with BBNJ agreement. Moreover, if there are some domestic legislations that conflict with the MPAs regime, then there will be more modifications work to do. On the other hand, after the conclusion of the BBNJ agreement, it is necessary to deal with the coordinated relationship between the BBNJ agreement and other international agreements ratified by China, which puts forward higher requirements for China to fulfill its international treaty obligations. Secondly, the challenge comes to China’s capacity of law enforcement. After the completion of the MPAs in ABNJ, it is necessary for participating countries to participate in the supervision and management of the protected areas. Because it is located outside the scope of national jurisdiction and it may also need coordination with other countries or international organizations, this scenario will probably put forward new and higher law enforcement requirements for the sea-related substantive departments of China. Finally, the pressure rests on China’s judicial capacity. When violation of relevant conservation and management measures happens in MPAs in ABNJ, disputes may arise. States participating in the construction of the protected areas may need to provide possible dispute resolution mechanisms, including judicial personnel (judges and arbitrators, etc.), as well as arbitration institutions.

At present, the relevant international legal system is not omnipotent, and the experience of other countries for reference is very limited, despite the fact that the system of MPAs prescribes additional standards and obstacles for the leading maritime powers. Before participating in the construction of MPAs in ABNJ, China needs to seriously consider various practical factors at home, and should neither blindly follow the trend nor be too timid.

4 Possible solutions for China

As a major marine country, China has to be prepared for the foreseeable challenges ahead when it choose to participated in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ.

4.1 Replace ocean fishing with deep-sea aquaculture (marine ranching)

Many domestic experts have recommended pertinent countermeasures from elements of operation mode, kind of operation, and building the capacity in accordance with relevant international standards in order to meet with the trend of the international community to restrict overfishing in ABNJ. China has implemented these measures in an effort to eventually comply with international standards and criteria. China has adopted these countermeasures to gradually meet the international requirements and further conform to international standards. But a better solution may be to use mariculture to gradually replace high sea fishing.

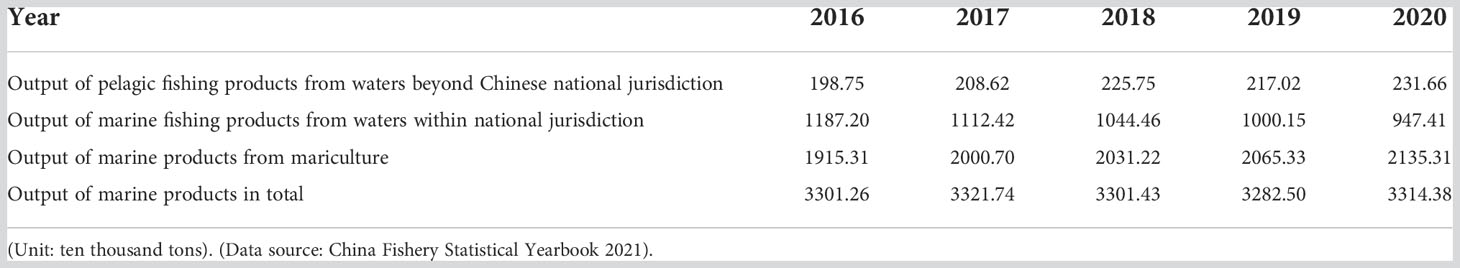

China is the world’s largest consumer as well as the largest producer of fish products. China is the largest aquaculture country in the world, accounting for more than 60% of the world’s total aquaculture (Kurzydlowski, 2021). It has initially developed a sound fishery industry structure and governance system. China is the only major fishery country in the world where the total amount of farmed aquatic products exceeds the total amount of captured aquatic products as shown in Table 2 below.

The report “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture” released by FAO in 2018 predicts that the global fish production is expected to reach 201 million tons in 2030, and nearly 2/3 of food fish will be provided by aquaculture (FAO, 2018), so there are great prospects for the development of cage culture in China. Since the 1970s, cage culture in China has experienced the development process from ordinary cage, deep-water cage to far-reaching sea cage. In 2020, there are about 38214000 cubic meters of deep-water cages in China, with a total production of 293120 tons, mainly distributed in Hainan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Shandong and Zhejiang Province. The development of marine aquaculture can largely reduce the production pressure of China’s high sea fishing industry.

4.2 Balance the relationship between conservation and utilization

It is necessary to balance the relationship between conservation and utilization and avoid emphasizing maintenance and neglecting utilization. What’s more, the balance between conservation and utilization is a key issue in the affairs of protected areas on the high seas. In the negotiation of the BBNJ agreement, the European Union blindly emphasizes the ecological elements of the high seas protected areas, while neglecting the social and economic factors, showing a tendency of “emphasizing conservation rather than utilization”.

For example, in the process of the establishment of Antarctic marine protected areas, the relationship between conservation and rational use involves the objectives and concepts of marine protected areas, which is one of the focuses of debate. Article 2 of the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine living Resources makes it clear that its purpose is “conservation of Antarctic marine living resources”, and the term “conservation” includes rational use. The purpose of this provision is to achieve a balance between conservation and utilization and the sustainable use of Antarctic living resources should not be excluded from the construction of Antarctic marine protected areas.

To balance the relationship between “conservation” and “rational use”, we need to rely on sufficient scientific data to quantitatively analyze how to achieve the balance between “conservation” and “rational utilization”. Therefore, China should increase investment in scientific research to collect the basic data extensively, which lays a scientific foundation for balancing the relationship between “conservation” and “rational utilization”. China must encourage fair and rational use of marine resources in harmony with sustained, effective protection of marine biodiversity, particularly in ABNJ, as a responsible power in international maritime affairs.

4.3 Improve the relevant national governance mechanisms

China should concentrate on the following three aspects to better response to the deficiencies of relevant domestic legal resources: First, China needs to reinforce and improve its overall planning, as well as create high-level mechanisms and coordination systems that are appropriate for the advancement of MPAs affairs. And China should strengthen the study of the draft text of BBNJ agreement and extensively solicit opinions and suggestions from scholars to prepare for the revision and updating of the related legislations in the future. Second, China should strengthen the building of law enforcement capacity and improve the joint marine law enforcement mechanisms in the field of BBNJ. Finally, China should improve the domestic maritime dispute settlement mechanisms and strengthen the training of relevant legal talents.

5 Conclusions

In the face of a bleak future, humanity’s capacity for alternate decision-making is preserved by nature’s diversity. Thus, we must decide what is best at the moment for the preservation of BBNJ. China must assume responsibility for preserving the planet’s home and strike a balance between preservation and sustainable use as a major nation in the world. In order to make it come true, China as well as other countries still has a long way to go. China should cooperate with the international community within the framework of the UNCLOS, given the complexity and sensitivity of protecting and using marine biodiversity in ABNJ as well as the information gaps. As a big proponent of creating a maritime community with a shared future, China has not only played a significant role in the formulation and compliance of the UNCLOS, but also actively participate in the follow-up legislative activities directly related to UNCLOS, especially in the negotiations of BBNJ agreement. It can be expected that, although there are both drivers and limits for China to participate in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ, China will choose to think from the point of view of safeguarding the interests of all mankind and is willing to make its own contributions in the establishment of MPAs in ABNJ.

Author contributions

YH conducted the analysis and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. MY supervised the project and acquired funding. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This paper is part of a research project funded by China’s National Social Sciences Foundation (18VHQ012).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Liu He (Shanghai University of Political Science and Law) for her consultation at the initial stage of the research work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Berry D. S. (2021). Unity or Fragmentation in the Deep Blue: Choices in Institutional Design for Marine Biological Diversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. Front Mar Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.761552

Brondízio E. S., Settele J., Diaz S., Ngo H. T. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services (Bonn, Germany: IPBES). doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3831673

Cárcamo P.F., Garay-Flühmann R., Squeo F. A., Gaymer C. F. (2014). Using stakeholders’ perspective of ecosystem services and biodiversity features to plan a marine protected area. Environ. Sci. Policy 40 (June), 116–131. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2014.03.003

CBD. (2021) Ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/ebsa/about (Accessed August 12, 2022).

CBD (2008). COP Decision IX/20. Marine and coastal biodiversity, COP 9 Decisions.. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=11663.

CBD (2020). Aichi biodiversity targets (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/.

CBD (2021). Report of the expert workshop to identify options for modifying the description of ecologically or biologically significant marine areas and describing new areas (CBD). Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/0898/480c/aa05b0f846b6a337046250f4/ebsa-ws-2020-01-02-en.pdf.

CCAMLR (2021). Marine Protected Areas, CCAMLR MPA Information Repository. Available at: https://cmir.ccamlr.org/.

Davies T. E, Maxwell S. M., Kaschner K, Garilao C, Ban N. C. (2017). Large marine protected areas represent biodiversity now and under climate change. Sci Reps. 7 (1), 9569. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08758-5

De Santo E. M. (2018). Implementation challenges of area-based management tools (ABMTs) for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). Marine Policy 97, 34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.08.034

Duan K., Yu J.. (2021). The Strategy Research for Promoting Global Ocean Governance Based on the Concept of “Maritime Community with a Shared Future. Journal of Ocean University of China (Social Sciences Edition) 6, 15–23. doi: 10.16497/j.cnki.1672-335X.202106002

Dunn D. C., Ardon J, Bax N, Bernal P, Cleary J, Creswell I, et al. (2014) The Convention on Biological Diversity’s Ecologically or Biologically Significant Areas: Origins, development, and current status. Marine Policy 49, 137–45. doi: /10.1016/j.marpol.2013.12.002

FAO (2009) International guidelines for the management of deep-Sea fisheries in the high seas. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i0816t/i0816t00.htm.

FAO (ed.) (2018) Meeting the sustainable development goals. Rome (The state of world fisheries and aquaculture, 2018). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i9540en/I9540EN.pdf.

Fu Y. (2019). Development and Challenges of Antarctic Marine Protected Areas. Chinese Journal of Engineering Science 21 (6), 9. doi: /10.15302/J-SSCAE-2019.06.002

Game E. T., Grantham H. S., Hobday A. J., Pressey R. L., Lombard A. T., Beckley L. E., et al. (2009). Pelagic protected areas: The missing dimension in ocean conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24 (7), 360–695. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.011

Gjerde K. M., Dotinga H., Hart S., Molenaar E. J., Rayfuse R., Warner R. (2008). Options for addressing regulatory and governance gaps in the international regime for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. IUCN marine law and policy paper 2 (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN). Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/EPLP-MS-2.pdf.

Hennicke J., Werner T., Hauswirth M., Vonk S., Schellekens T., Chaniotis P., et al. (2022) Report and assessment of the status of the OSPAR network of Marine Protected Areas in 2021. Available at: https://oap.ospar.org/en/ospar-assessments/committee-assessments/biodiversity-committee/status-ospar-network-marine-protected-areas/assessment-reports-mpa/mpa-2021/.

IUCN (2022). Governing areas beyond national jurisdiction, IUCN. Available at: https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/governing-areas-beyond-national-jurisdiction.

Jin Y. (2021). On the Theoretical Regime of the Maritime Community with a Shared Future. Journal of Ocean University of China (Social Sciences Edition). [Preprint], (1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.16497/j.cnki.1672-335X.202101001.

Kurzydlowski C, et al. (2021). Chinese Aquaculture Grows Alongside Global Appetite for Fish. The China Guys. Available at: https://thechinaguys.com/aquaculture-in-china/.

Liu S. (2019). Review and Future Prospect of China’s Pelagic Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Available at: http://www.yyj.moa.gov.cn/gzdt/201910/t20191023_6330464.htm.

MFAT (2022). Ross Sea region Marine Protected Area, New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Available at: https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/environment/antarctica-and-the-southern-ocean/ross-sea-region-marine-protected-area/.

MNRPRC (2022). China Marine Economic Statistics Bulletin 2021. Beijing: Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-06/07/5694511/files/2d4b62a1ea944c6490c0ae53ea6e54a6.pdf.

NOAA (2021). Why should we care about the ocean?, National Ocean Service website. Available at: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/why-care-about-ocean.html.

OSPAR (2014). Collective Arrangement, OSPAR Commission. Available at: https://www.ospar.org/about/international-cooperation/collective-arrangement.

Protected Planet (2022) “Marine protected areas.” explore the world’s protected areas2022. Available at: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/marine-protected-areas.

Rochette J., Wright G., Gjerde K. M., Greiber T., Unger S., Spadone Aurélie (2015). A New Chapter for the High Seas? IASS Working Paper, Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies Potsdam (IASS) Vol. 2. 12. doi: 10.2312/iass.2015.012

Rogers A. D., Laffoley D. (2013). Introduction to the special issue: The global state of the ocean; interactions between stresses, impacts and some potential solutions. synthesis papers from the international programme on the state of the ocean 2011 and 2012 workshops. Mar. pollut. Bull. 74 (2), 491–945. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.057

Scott K. N. (2019). Area-based Protection beyond National Jurisdiction: Opportunities and Obstacles. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ocean Law and Policy 4 (2), 158–180. doi: 10.1163/24519391-00402004

Shi Y. (2022). Challenges of Negotiations on Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction and China’s Approach - A Perspective of Maritime Community with a Shared Future. Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Affairs 1, 35–50. doi: 10.19780/j.cnki.ytaq.2022.1.3

Toonen R. J., Wilhelm T.‘Aulani, Maxwell S. M., Wagner D., Bowen B. W., Sheppard C. R. C., et al. (2013). One size does not fit all: The emerging frontier in Large-scale marine conservation. Mar. pollut. Bull. 77 (1–2), 7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.10.039

UN (1982) United nations convention on the law of the Sea of 10 December 1982. Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/UNCLOS-TOC.htm.

UN (2014). “Decree No.2012-1148 of 12 October Establishing an Economic Zone off the Coast of the Territory of the French Republic in the Mediterranean Sea,” in Law of the Sea Bulletin No.81. New York: United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/mzn_s/mzn94ef.pdf.

UN (2021). Ocean science and technology critical to restore deteriorating global marine environment, warns latest UN assessment, United Nations Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2021/04/ocean-science-and-technology-critical-to-restore-deteriorating-global-marine-environment-warns-latest-un-assessment/.

UNGA (2004) Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 17 November 2004. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_59_24.pdf.

UNGA (2015) 69/292. Development of an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. United Nations. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/187/55/PDF/N1518755.pdf?OpenElement.

UNGA (2017) Report of the preparatory committee established by general assembly resolution 69/292. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1306977.

UNGA (2018). 72/249. International legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. United Nations. doi: 10.18356/9789210021753c001

UNGA (2022). Further revised draft text of an agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/368/56/PDF/N2236856.pdf?OpenElement.

Verity P. G., Smetacek V., Smayda T. J. (2022). Status, trends and the future of the marine pelagic ecosystem. Environmental Conservation 29 (2), 207–237. doi: 10.1017/S0376892902000139

Wang J. (2020). On Practical Dilemmas and International Law-making of Marine Protected Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. Pacific Journal 28 (9), 52–63. doi: 10.14015/j.cnki.1004-8049.2020.09.005

Wright G., Rochette J., Greiber T. (2016). “Sustainable development of the oceans: Closing the gaps in the international legal framework,” in Legal aspects of sustainable development: Horizontal and sectorial policy issues. Ed. Mauerhofer V. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 549–564. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-26021-1_27

Xu W. (2015). Research on the relationship between high seas marine protected areas with the current system of law of the Sea. J. Zhejiang Ocean Univ. (Humanities Science) 32 (6), 8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8318.2015.06.002

Xue G. (2021). The Concept of Maritime Community with a Shared Future: The Transition from Consensus Discourse to Institutional Arrangement - from the Perspectives of BBNJ Instrumental Consultation. Law Science Magazine 42 (9), 53–66. doi: 10.16092/j.cnki.1001-618x.2021.09.005

Yang Z., Liu D. (2019). Current Situation, Characteristics, and Future Strategic Vision of China’s International Seabed Area Development. Northeast Asia Forum 28 (3), 114–126. doi: 10.13654/j.cnki.naf.2019.03.009

Zhou W. (2020). What is the influence of establishing “no-fishing” protected areas in high seas on global fisheries? World Environment 4, 27–31. doi: 10.13654/j.cnki.naf.2019.03.009

Keywords: marine protected areas (MPAs), areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), ocean governance, marine biodiversity, biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), China

Citation: Yu M and Huang Y (2023) China’s choice on the participation in establishing marine protected areas in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:1017895. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1017895

Received: 12 August 2022; Accepted: 29 November 2022;

Published: 06 January 2023.

Edited by:

Yen-Chiang Chang, Dalian Maritime University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Yu and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuwen Huang, aHVhbmd5dXdlbkB3aHUuZWR1LmNu

Minyou Yu

Minyou Yu Yuwen Huang

Yuwen Huang