“Ocean Optimism” and Resilience: Learning From Women’s Responses to Disruptions Caused by COVID-19 to Small-Scale Fisheries in the Gulf of Guinea

- 1School of Geography and Sustainable Development, University of St Andrews, St. Andrews, United Kingdom

- 2National Defence College (NDC), Abuja, Nigeria

- 3School of International Relations, University of St Andrews, St. Andrews, United Kingdom

- 4School of Humanities and Social Science, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

This study examines the response of women to disruptions caused by COVID-19 in small-scale fisheries (SSF) in the Gulf of Guinea (GOG). It interrogates the concept of resilience and its potential for mitigating women’s vulnerability in times of adversity. We define resilience as the ability to thrive amidst shocks, stresses, and unforeseen disruptions. Drawing on a focus group discussion, in-depth interviews with key informants from Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria, and a literature review, we highlight how COVID-19 disruptions on seafood demand, distribution, labour and production acutely affected women and heightened their pre-existing vulnerabilities. Women responded by deploying both negative and positive coping strategies. We argue that the concept of resilience often romanticises women navigating adversity as having ‘supernatural’ abilities to endure disruptions and takes attention away from the sources of their adversity and from the governments’ concomitant failures to address them. Our analysis shows reasons for “ocean optimism” while also cautioning against simplistic resilience assessments when discussing the hidden dangers of select coping strategies, including the adoption of digital solutions and livelihood diversification, which are often constructed along highly gendered lines with unevenly distributed benefits.

Introduction

Throughout Africa, fish is vital to food and economic security. In the Gulf of Guinea (GOG), on sub-Saharan Africa’s west coast, the fisheries industry serves as a particularly important source of food, animal protein, income, and employment. It promotes rural development and boosts government revenue through fisheries agreements, licenses and taxes (Asiedu and Nunoo, 2015). The vast majority of fish consumed on the continent, along with employment opportunities in the fishing industry, is provided by small-scale fishers (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2022). However, the small-scale fisheries industry (SSF) is highly vulnerable to external shocks. These include seasonal shifts in fish catch; disruptions due to epidemics like Ebola; the multiple, overlapping effects of climate change; shifting demands for coastal development (Khan and Sesay, 2015; Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2021); and depleting fish stocks from the overexploitation and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing carried out by industrial fishing, which is carried out and dominated by foreign, distant water fleets.

These vulnerabilities are becoming only more urgent. Over the last decade, the income accrued by small-scale fishers West Africa plummeted by roughly 40% due to depleting catch (The World Bank, 2016). Measures introduced by coastal states in the region with the intention of addressing depleting fish stocks, such as closed seasons, marine protected areas and anti-IUU fishing patrols, disproportionately affect small-scale fishers, undermining their rights and pushing them further into poverty (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2022). Those along the value chain, such as processors and sellers, many of whom are women, are disproportionately affected by these measures (Okafor-Yarwood et al., 2022).

SSF is mired by gender inequalities through which contributions made by women are systematically undervalued and “invisibilised” (Thorpe et al., 2014; Harper et al., 2017; Reva and Kumalo, 2020). Although men dominate fishing activities, women also often engage in the activity. More notably, however, women play a significant role in sustaining the sector by financing fishing activities (Harper et al., 2013; Torell et al., 2019), dominating the value chain (Okafor-Yarwood and van den Berg, 2021) and almost exclusively managing post-harvest activities (Du Preez, 2018). Operating within an already highly vulnerable sector, women in SSF are, therefore, further disadvantaged by the adverse effects of gender inequality (Kleiber et al., 2015).

The COVID-19 pandemic further amplified the challenges being faced by fisherfolk across the globe with the pandemic’s uneven effects felt most acutely by those populations and sectors whose long-standing marginalization makes them ill-equipped to adapt positively to adversity (WEF, 2021). Early research on the impacts of COVID-19 on SSF highlighted these adverse effects (see, for example, Love et al., 2021). While research on COVID-19 impacts and resilience in the SSF sector, in general, is nascent (see: FAO, 2020a; Avtar et al., 2021; Love et al., 2021), existing studies recognised the uneven distribution of COVID-19’s adverse impacts and highlighted the sectors and populations whose pre-existing vulnerabilities have been amplified by the pandemic’s disruptions. Yet, women’s responses to COVID-19 within SSF remain understudied. Where these studies do exist, they feature a heavy regional bias, with much of the literature dedicated to assessments of SSF in Southeast Asian contexts (see: Campbell et al., 2021; Ferrer et al., 2021; Manlosa et al., 2021).

Our paper addresses this lacuna by empirically and conceptually advancing understandings of the impacts of, and responses to, adversities in the Gulf of Guinea’s fisheries sector among women, emphasizing the COVID-19 pandemic, as a source of adversity for this sector. First, we examine the gendered impacts of COVID-19 disruptions on the SSF sector in the GOG, focusing especially on women and the nature of their responses. Secondly, we assess coping strategies employed by women and highlight examples of “ocean optimism” within SSF while also cautioning against simplistic assessments that equate all coping strategies as evidence of resilience in the sector in times of adversity. Finally, in view of our findings, we recommend strategies for transformational resilience/transformational change, recognizing that women and men respond differently to adversities in SSF and may benefit from targeted support in times of adversity. Our findings are significant for advancing the global discourse on SSF and its gendered realities by empirically grounding understandings of the impacts of, and responses to, COVID-19 disruptions. They also contribute to the global discourse on resilience and its varied contextual meanings.

Following our review of the concept of resilience, we describe the study area and qualitative methodology of the paper. This is followed by the results, which integrate primary findings with evidence from existing literature and details the gendered impacts of COVID-19 disruptions and their amplification of pre-existing gendered vulnerabilities for women in SSF. In subsequent sections, we examine women’s negative coping strategies to COVID-19 disruptions before turning to observations of what we term “ocean optimism” by illuminating evidence of positive coping strategies among women in the GOG’s SSF. We then critically reflect on digital solutions for SSF and diversification as coping/adapting strategies. Finally, we conclude with recommendations for cultivating gendered pathways to building transformational resilience in times of adversity. Our applied objective (post data-analysis) is to show that men and women’s vulnerabilities in SSF should be equitably but differentially addressed, and that there is a need for government intervention that addresses the root causes of these challenges.

Conceptualising Resilience

Resilience is a central concept within development discourses. It refers to the capacity to absorb shocks or disruption (USAID, 2012; UN, 2015; Love et al., 2021). It is intimately tied to vulnerability, understood as susceptibility to shocks or disruption (Adger, 2006; Cinner et al., 2012). Prominent definitions of resilience emphasize its reference to the ability to ‘resist’, ‘absorb’ (UN, 2015: 9), ‘adapt to’ (USAID, 2012: 5), and ‘recover from’ (USAID, 2012; UN, 2015, 5) shocks. Smyth and Sweetman (2015) underscore this by arguing that at the heart of resilience ‘is the idea of strength in the face of adversity’ (406).

Within prominent conceptualizations of resilience, the focus on the abilities of vulnerable ‘people, households, communities, countries and systems’ (USAID, 2012, 5) to survive shocks has been challenged by critics, who question the term’s tendency to avoid addressing the actual sources of external threats and shocks. Shwaikh (2021), for instance, argues that this deployment of the concept is both dehumanising and dangerous in its romanticisation of populations navigating adversity as having ‘supernatural’ abilities to endure, while simultaneously distracting attention and accountability away from the sources of adversity. For Shwaikh (2021), while resilience is widely considered a ‘valued and cherished trait’, the discourse masks issues like ‘vulnerability, structural violence, and trauma’ and frames resilience as ‘acts of heroism’. Resilience is also seen, in this vein, as absolving the larger structural factors, forces, and the actors behind them from their roles in producing the conditions of adversity (and the inequalities). MacKinnon and Derickson (2013) echo these risks by asserting that state agencies and experts’ knowledge often drive the definition of resilience. This top-down approach to resilience places the burden on populations affected by disruptions and reproduces wider social and spatial relations, exacerbating vulnerabilities and inequalities. Resilience thus places the onus of survival on the vulnerable and frees systemic forces and actors from accountability or responsibility to address the root drivers of inequality and vulnerability.

However, these criticisms do not invalidate the utility of term. Transformational approaches to resilience suppose that resilience is not merely an ability to ‘survive one shock after another’ (Smyth and Sweetman, 2015: 411), but to positively cope with disruption and build new development pathways amidst adversity (Folke, 2016). Our analysis aligns with Folke’s (2016) conceptualisation of resilience as coping strategies that are transformational, transcending coping/adapting or recovery, and forging new pathways that allow fisherfolk to thrive and continue to meet the needs of their households. In our context, however, government actors must support fisherfolk and work to address the causes of their adversities if resilience is to be sustainable.

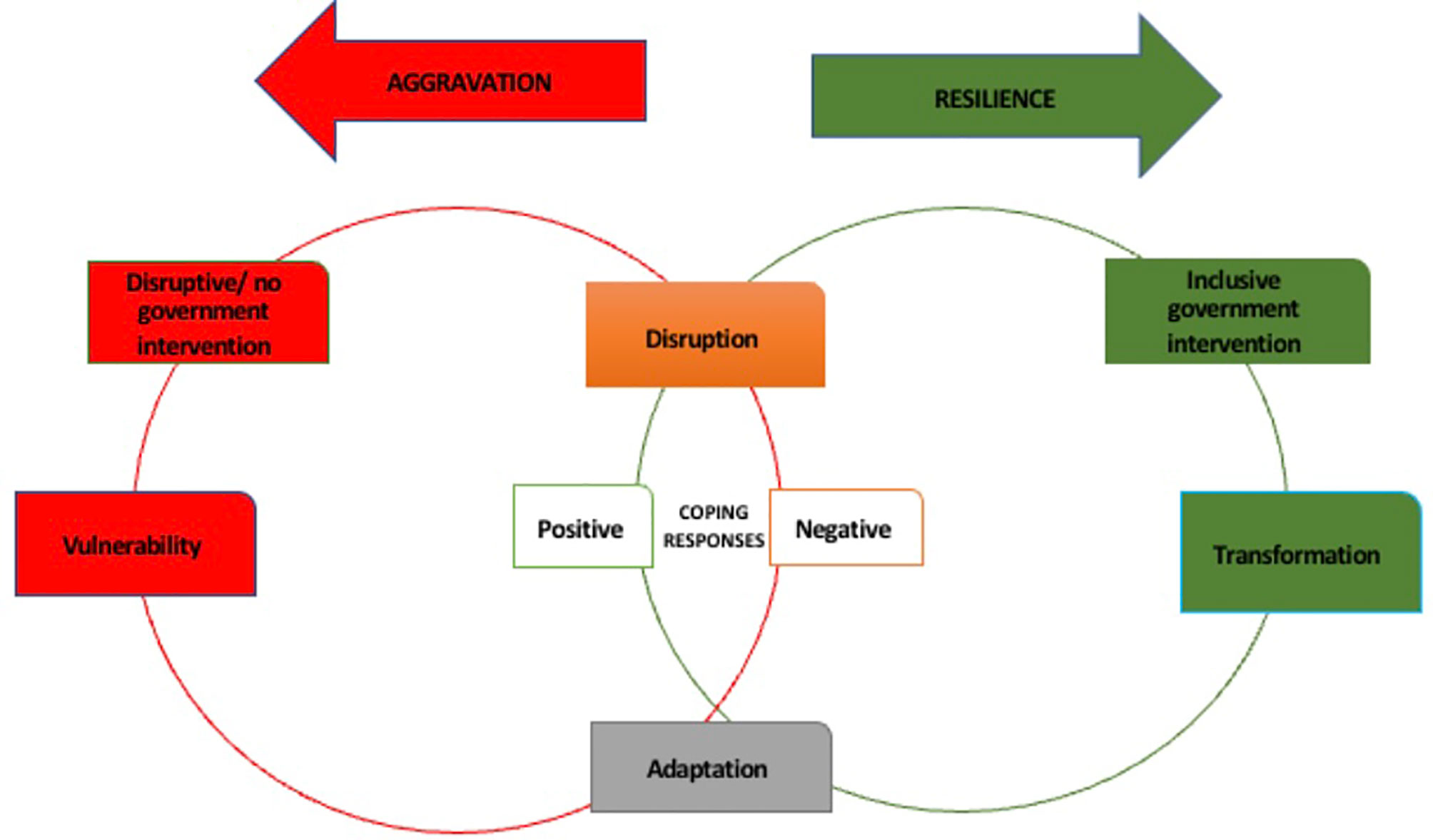

We operationalise this transformational approach to resilience by categorising fisherfolk responses to COVID-19 disruptions according to coping mechanisms and adaptations. Coping strategies refer to what fisherfolk do in the short term to ensure their well-being in times of adversity. Once such behaviour becomes permanent, we see them as having adapted to the situation. We then distinguish between positive and negative fisherfolk responses to disruptions. We assert that coping mechanisms and adaptations in the face of adversity can take the form of negative responses – behaviours that mitigate the risks of a particular shock while simultaneously introducing new vulnerabilities and/or heightening existing vulnerabilities. In other words, when a coping mechanism or adaptation to a specific disruption creates or exacerbates other vulnerabilities, such responses are negative and insufficient to meet resilience needs within a transformational approach. Conversely, positive coping strategies and adaptations mitigate the effects of disruption while also reducing the vulnerability to further and/or future shocks. The key distinction is whether responses address or perpetuate the root vulnerabilities that dictate susceptibility to shocks and the extent to which governments provide support and seek to address the sources of adversities.

Within this framework, responses to disruption can thus only be considered indicative of resilience if they reduce the root vulnerabilities that determine the severity of disruptions in the first instance – see Figure 1.

In this paper, we focus on gender as a risk multiplier. Specifically, we focus on how women in the SSF sector have responded to the disruptions caused by COVID-19 and assess the resilience-potential of these responses based on how these responses interact with their pre-existing SSF vulnerabilities. This line of inquiry has critical importance, given the high degree of vulnerability that existing research within SSF has recognised among women within this sector (see, for instance, Thorpe et al., 2014; Harper et al., 2017; Galappaththi et al., 2022; Oloko et al., 2022). This also aligns with gendered resilience studies, which argue that a gendered view of resilience is critical to advancing an inclusive and sustainable understanding of resilience approaches (see, for example, Smyth and Sweetman, 2015).

We ground this social construction of vulnerability along highly gendered lines and its implications for experiences of, and responses to, disruption in Luft’s (2016) model of disaster patriarchy. Disaster patriarchy argues that resilience is conditioned on socially embedded gendered and racialised inequalities produced before a disaster occurs, and reproduced during and after the event (see Luft, 2016, V. 2021). Luft’s (2016) model provides a lens through which the profoundly gendered and racialised dimensions of disaster can be understood, along with the ‘political, institutional, organisational and cultural’ (Luft, 2016:1) systems in which people attempt to survive, resist, explain, and recover from crisis. These studies and other studies that adopted this approach (V, 2021) highlight the need to understand the social construction of women’s vulnerability, which ‘is not a natural attribute of women but rooted in gender inequality’ (Smyth and Sweetman, 2015, 410) that conspires to reduce women’s ‘adaptive capacity’ (Cinner et al., 2012: 13) in the face of disruption. By acknowledging the role that gender plays in shaping vulnerability, it becomes ‘essential to adopt approaches to resilience which challenge gender inequality and promote women’s rights’ (Smyth and Sweetman, 2015: 406).

Despite women’s crucial and significant role in SSF in Africa, women often find themselves marginalised and their contributions largely un(der)valued compared to those of men. These dynamics produce gendered vulnerabilities that further disadvantage them (see: Isaacs et al., 2022). Gendered definitions of fishing (Harper et al., 2017; Galappaththi et al., 2022), earnings gaps (Thorpe et al., 2014; Du Preez, 2018) and social expectations (Oloko et al., 2022) conspire to render women invisible in SSF, as their participation in SSF continues to be concentrated in the informal economy where they are excluded from institutional consideration or social protections (Okafor-Yarwood and van den Berg, 2021). Specifically, women’s fisheries work is often perceived merely as an extension of their gendered everyday lives (Harper et al., 2017), limiting their livelihood security and making them particularly vulnerable to disruptions that threaten their already precarious livelihoods. These vulnerabilities are not natural attributes, i.e., the result of being women, however defined. Rather, these vulnerabilities emerge because of the social construction of womanhood and the roles and limitations that accompany this gender category (Smyth and Sweetman, 2015). The evidence is overwhelming – throughout the GOG and in other parts of the world, SSF is bifurcated along gendered lines wherein men carry out the fishing and women, the processing (Harper et al., 2017).

Centring a gendered approach to understanding the construction of, experiences of, and responses to disruptions acknowledges the constitutive role of gender in disruption in two important ways. First, it recognizes that the gendered construction of vulnerability does not prohibit resilience strategies among women and avoids reducing women entirely to their vulnerabilities. Second, a gendered approach to resilience concurrently recognizes that resilience, like vulnerability, is socially constructed and conditioned. Our approach to understanding resilience acknowledges that local fisherfolk’s coping and adaptive potential is contingent on their access to the necessary logistics or resources. As such, fisherfolk’s ability to cope or adapt in times of adversity should not absolve the collective and structural forces of states, governments and NGOs that have within their power the ability to mitigate adversity and the need for resilience in the first place. Therefore, the gendered approach to resilience we adopt in this paper empirically and theoretically advances the need for gender sensitivity in resilience research and resilience-building, in line with a multi-level, inclusive and transformational understanding of the concept of resilience. We define gender as the roles, norms and expectations attached to SSF engagement for men and women in the GOG that are anchored in the sector’s identity politics of male and female differences.

Study Area and Methodological Considerations

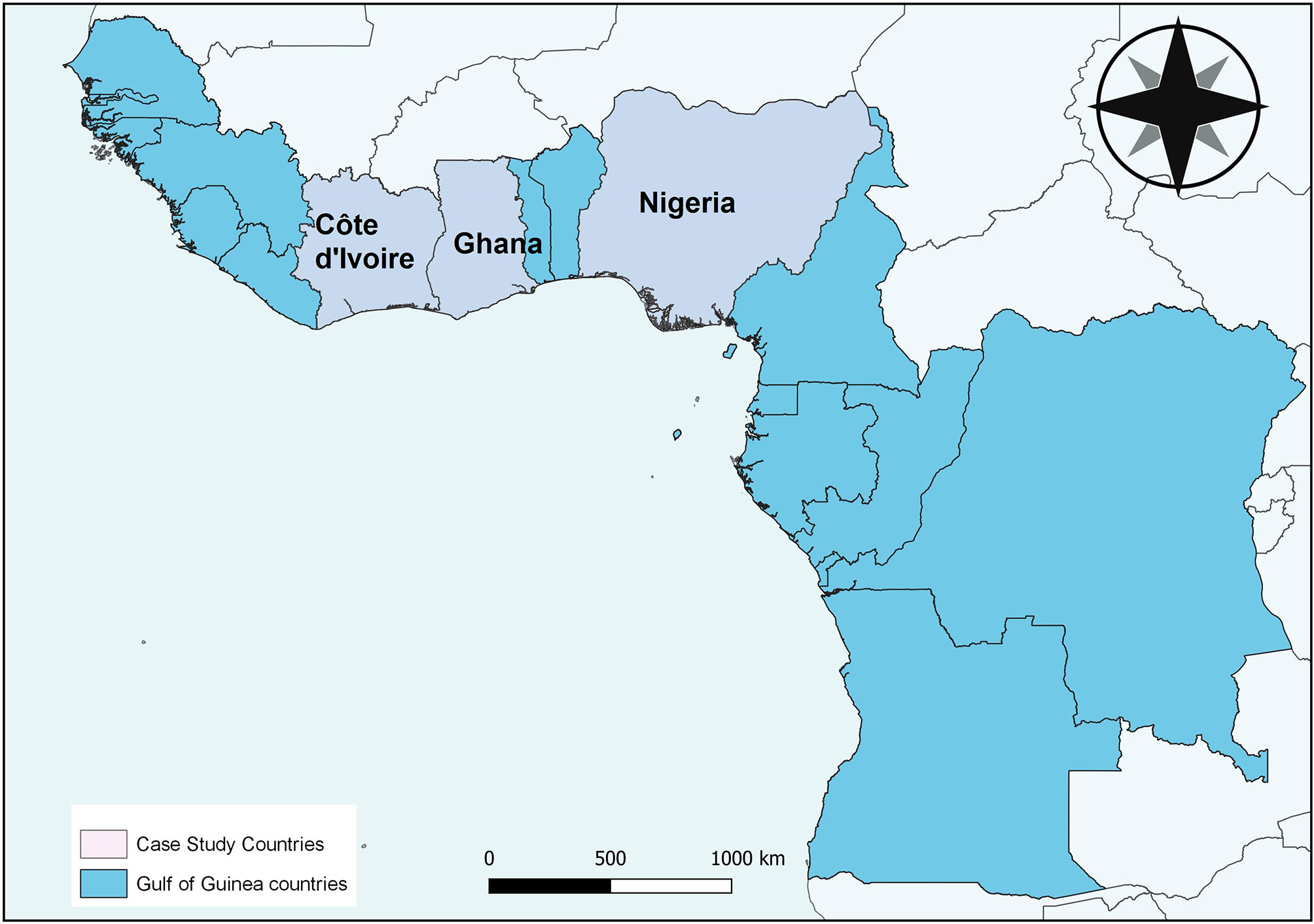

The GOG covers 6,000 kms of coastline, extending from Senegal to Angola and includes the island nations of São Tomé and Príncipe and Cabo Verde – see Figure 2 below. The region is of critical global significance due to its vast marine and mineral resources.

The case study selection and stakeholder interview sampling strategy for this research were fourfold. First, the cases of Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria were selected due to the significant contribution of the SSF therein – accounting for over 75% of total fish production in the region and often providing the main source of protein nutritional for communities in these countries (FCWC, 2020). Secondly, the adversity and gendered inequalities of the SSF sector in these countries are well recognised in literature, making them suitable cases for deepening understandings of women’s resilience in SSF. Thirdly, the positionality of interview respondents as representatives of larger and critical SSF stakeholder groups, including women’s fisheries cooperatives and SSF non-governmental organisations (NGO) personnel, provided a unique opportunity to broaden the scope of analysis stemming from mixed-gender Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) responses by integrating additional levels of stakeholder responses. Finally, primary data collection possibilities for this research have also been impacted by COVID-19 travel disruptions, placing limitations on the number of countries, interviews and FGDs that were possible at the time of this research.

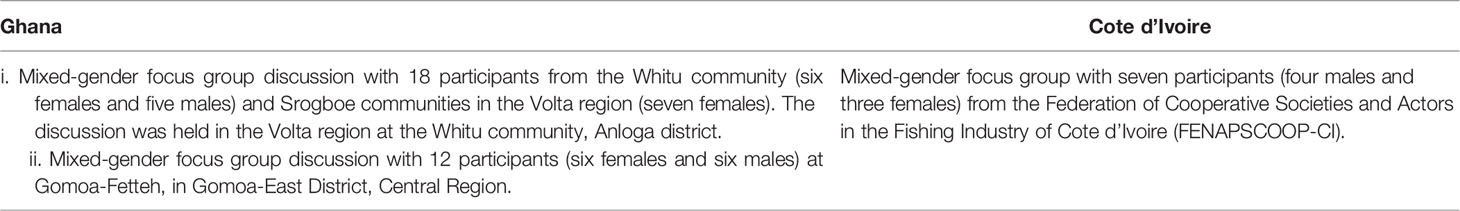

We employed the triangulation method for data gathering, which involved combining five (5) qualitative in-depth key informant interviews, three mixed-gender FGDs with fisheries experts, representatives from Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), fishing cooperatives and fisherfolk in Cote d’ Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria. This primary data was then combined with a review of published literature, and secondary source material including grey literature from governmental, intergovernmental, and non-governmental organisations.

We conducted an online interview with the president of The Union of Cooperative Societies of Women in Fisheries and Assimilated of Côte d’Ivoire (USCOFEP-CI), a union of several women’s cooperatives in Côte d’Ivoire.1 In Ghana, we conducted two interviews – one online with a female representative of a CSO and an in-person interview with a male fisheries livelihoods expert and a CSO employee. In Nigeria, we conducted two telephone interviews with the male and female representatives of the Bonny Indigenous Fishermen Cooperative Union – despite the name, women who are fishers, fish processors, traders, and marketers indigenous to Bonny Island are part of this Union.

Mixed-gender groups instead of single-gender FGDs were utilised because it allowed us to understand how men and women were affected differently by the COVID-19 disruptions. We deemed the dialogue between men and women, when confronted with each other’s opinions, to be necessary for ascertaining the varying degree to which they have been affected by and responded to COVID-19 disruptions. It allowed men and women affected by the same issue (COVID-19 disruptions) to benefit simultaneously from exploring different perspectives within a group (see: Strandbu and Kvalem, 2014)– see Table 1 for a description of FGD participants. Importantly, this approach was convenient for our participants. They belonged to the same cooperative groups and were keen to learn how others were affected by and responded to the impact of COVID-19 disruptions.

Qualitative methods were used in supporting this project because they allowed us to gain an in-depth understanding of the perspectives and experiences of our participants. Triangulating our data sources enabled us to validate the findings derived from these sources (see: Carter et al., 2014) and deploy a constant comparison method in our analysis. This method entails interpreting and comparing interview findings and FGDs as they emerge from the data analysis with results from similar research elsewhere (Timonen et al., 2018). Specific to the study, we extended the seafood disruption framework provided by (Love 2021), which includes attention paid to demand, distribution, labour, and production, disruptions, to highlight the impact of COVID-19 disruptions on SSF with an emphasis on women.

The data was collected between June 2021 and August 2021. We employed purposeful sampling for our interviews and FGDs, which entailed identifying and selecting participants based on their knowledge and experiences as fisherfolk or as CSO personnel. The availability and willingness to participate and the ability to share experiences and opinions on the impact of COVID-19 disruptions and how they responded to their adversity reflectively were also considered (see: Palinkas et al., 2015). The data collection was done remotely for some interviews and in-person for others, and four languages were used: English (Ghana and Bonny Island – Nigeria), Ewe and Fante (Volta and Central region of Ghana), and French (Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire).2 A translator was required for the non-English languages during the interviews, and FGDs and field notes were taken. The interactions with the participants were not recorded: this was to allow them to speak freely about their experiences. However, notes were taken to deepen the understanding of participants’ meaning, which enhanced the data and provided a rich context for analysis (see: Phillippi and Lauderdale, 2018).

We created contact summary forms, also known as memos, for each interview and FGDs to be familiarised with the data, capture key concepts, themes, or issues that arose during the data collection, and reflect on the data collection process. These notes were later analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2012) because they allowed us to identify, analyse, and report themes from the qualitative data. The contact forms or memos helped us plan for the next interview and FGD, revise existing codes, literature review, and further analyse data (see, for example, Chikowore and Kerr, 2020). We then divided the data analysis into two; one focused on the gendered impact of COVID-19 on SSF, and the second focused on women’s responses to the impact of the pandemic and the general adversity they face in the SSF sector.

The interviewees’ roles as leaders of either cooperative societies or representatives of fishing CSOs, and fisherfolk’s participation in the focus groups provided depth, richness and validity to the data. Such an approach also provided ample opportunity to make a wider assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 disruptions and responses to it alongside the evidence from the extant literature. Our participants provided an opportunity for us to gain new insights and an in-depth understanding of their lived experiences around the impacts of COVID-19 and how they responded to their adversities. Whilst this research represents examples from select countries in the GOG, the findings are not generalisable. We do not aim to over-generalise these responses as a “one-size-fits-all” narrative, even though countries in the region share similar characteristics concerning challenges to sustainable fisheries and livelihoods in coastal communities. Our findings highlight the need for further study on the subject, and we believe our research method to be transferable to countries outside the case study areas.

Results: Impacts of COVID-19 Disruptions in the Gulf of Guinea

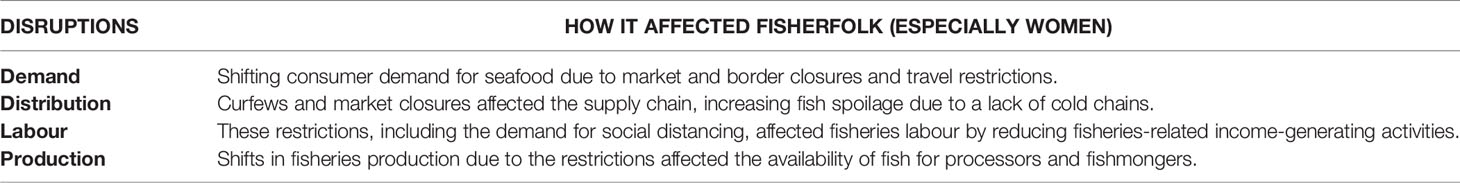

The adversities faced by the SSF sector have been amplified by COVID-19 disruptions (FAO, 2020a; FAO, 2020c). COVID-19 measures, particularly lockdown and social distancing measures implemented throughout the GOG to curb the spread of the virus, caused four types of disruptions to SSF in the GOG: demand; distribution; labour; and production disruptions (see: Love et al., 2021). For their part, the FAO (2020a) has acknowledged the impacts of COVID-19 disruptions across the globe by noting that fisheries were ‘disrupted, causing negative impacts on supply [i.e., production], demand and logistics [i.e., distribution] and adverse social and business [i.e., labour] consequences’ (FAO, 2020b:1). To show briefly how men and women in fisheries in the GOG were affected by COVID-19 restrictions, we extend Love et al.’s (2021) argument to show how these disruptions affected women’s activities within the fisheries value chain in the GOG – see Table 2.

Table 2 Covid-19 Disruptions to seafood systems and their effects on women in SSF (adapted from Love et al., 2021).

Each of these four categories of disruption amplified the pre-existing challenges for those affected. The emphasis is on women due to their position in the value chain and the extent to which they are affected by the disruptions. Men dominate the at sea activities. Therefore, they are not affected in the same way.

Demand disruptions to SSF in the GOG due to market and border closures and travel restrictions reduced seafood demand by severing access to consumers in the GOG. The threats posed by these disruptions are bidirectional: women cannot access consumers and are thus unable to sell seafood products. Similarly, consumers cannot access seafood, which is a vital source of protein and nutrition for a vast majority of the GOG population. Demand disruptions also decrease the market value of seafood products (FAO, 2020a), forcing fisherfolk to sell their products at a loss. Throughout Guinea, Ghana, and Senegal, fisherfolk lost their products due to growing operational costs and reduced demand (CFFA, 2020c; Darko, 2020; Diallo, 2020). Respondents from Nigeria described how fishmongers ‘sold fish at a loss to avoid spoilage due to the locked down (sic) and reduced demand’ that followed.3 Respondents from Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire underscored this point, noting that market closures and curfews affected demand for fish which forced them to sell at a loss while others went to waste because they could not sell them.

Distribution was disrupted by lockdown measures which caused the entire SSF value chain to shrivel. In Cote d’ Ivoire, efforts to reduce congestion at ports, which crucially link landed fish to processors and marketers, resulted in rotating access to the San Pedro Port – the country’s second-largest port and one of the most important ports on the West African seaboard.

This system initially restricted access to the port to once every 15 days but was later extended to 19 days. This system effectively prevented women from being able to purchase fish to sell for almost three weeks.4

Transportation was also interrupted by the restrictions, which affected women’s ability to sell their fish. In Ghana, social distancing requirements saw public transport reducing the number of passengers and increasing the fees per passenger (Okyere et al., 2020). Distribution costs of transporting fish to consumers increased, while women fishmongers’ revenue potential significantly decreased. In Guinea, increasing transportation costs meant that women had to decide whether the costs of transportation to landing, processing and consumer sites were worth the little money they could earn in reduced demand (Diallo, 2020). At the height of the pandemic, women fish processors and marketers sold at a loss, as the distribution costs tied to transporting fish outweighed their revenue potential.

Labour disruptions induced by the restrictions affected both men and women. However, the extent to which women were affected was much greater due to the highly gendered division of labour in SSF, which concentrates on women in landing and processing sites and client-facing markets. As a result, while the lockdown measures affected men’s ability to go to sea, women in the value chain who work in the landing and processing sies, were out of jobs. In Ghana, fish processing businesses reduced the number of processors to implement the social distancing measures.

In places where ten processors used to work, this was reduced to three or four to observe the social distancing. Working in shifts means that multiple families are affected.5

Respondents from Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire disclosed similar experiences, which align with the findings of an FAO (2020b:3) report that noted that implementing of social distancing requirements in fishery processing sites ‘reduced capacity’ which further reduces women’s economic welfare in SSF.

Finally, production disruptions caused by lockdown or social distancing measures affected fishermen’s ability to go to sea, reducing access to fish among women fish processors and sellers throughout the GOG; it also increased competition for fish (Harris, 2020). Production disruptions also affected the predominantly female population of fish processors in the GOG, as the demand for preserved fish (through smoking or freezing) increased (FAO, 2020b). Yet, the capacities to meet these shifts in demand remained limited due to a lack of access to fish. Even when some fish may have been available, processing capacities were also disrupted with restricted access to processing sites due to social distancing, curfews, and low processing capacities that typify SSF.6

These disruptions have cascading effects. In Cote d’Ivoire, fisherfolk welfare worsened due to COVID-19 restrictions that reduced the number of fishing crew and processors working at any given time, disrupted fishing supply chains, limited the movement of people, and caused market and border closures.7 In Cameroon, reduced catch resulted in decreased sales, as the fishers could not catch enough to sell to fishmongers. The impact on the value chain is that both the processors and the sellers did not have enough fish or sometimes did not have any fish to process or sell (Nyiawung et al., 2021).

Women in SSF in the GOG have experienced an acute growth of the pre-existing challenges that their gendered SSF roles ascribe to them due to COVID-19 disruptions. For instance, in describing the impact of COVID-19 on women in the fisheries value chain in Cote d’Ivoire, the president of USCOFEP-CI noted that ‘COVID-19 has unravelled [much] of the progress made by the cooperative to ensure fair treatment and secure livelihoods for women’.8 These disruptions thus provide a timely opportunity to explore women’s responses to adversities within the highly vulnerable SSF sector in the GOG.

Women’s Responses to COVID-19 Disruptions: Coping Strategies Deployed in Times of Adversities

This section explores how the responses of women to COVID-19 disruptions interacted with other vulnerabilities.

Negative Coping Mechanism: Access to Fish at a Cost! Sex for Fish or Finance

COVID-19 disruptions for the SSF sector throughout the GOG reduced fish access for most of the women population of fishmongers and processors. This reduced access, (Okyere et al., 2020) increased competition for fish among women in SSF, with dangerous consequences. Transactional sex in the fishing industry is commonplace, whereby women exchange sex for fish to ensure continued access to fish, and sometimes credit, from fishers (Béné and Merten, 2008; Okafor-Yarwood, 2020). The sex economy of fisheries reveals the murky depths of gender inequity within the sector, as hierarchical and patriarchal power relations push women to commodify their bodies to meet their livelihood needs and household responsibilities. HIV/AIDS infection rates in fishing communities across Africa, Asia and Latin America are between 4 and 14 times higher than national averages (Kissling et al., 2005), with transactional sex in the fisheries sector contributing to this high prevalence (FAO, 2015). In Ghana, during the pandemic, the “sex for fish” phenomenon has been exacerbated, as vulnerable women exchange sexual favours with male fishers for a regular supply of fish on credit, with payment to be made after the sale of the fish. Sharing an excerpt from their field research, one respondent declared:

…[The] “sex for fish” phenomenon is real in [Keta area of the Volta region]. Some women give themselves to migrant fishermen (especially those from Accra and Ada area) to buy fish on credit from them. It is a sad thing, but some desperate women indulge in it for survival … Many women in the community are in sexual relationships with fishermen, so they get fish supplies on credit. This is common, and some of these men have several female partners. It is an unfortunate situation, but since they are all adults and must satisfy their personal needs and their kids, a blind eye is turned to these things. It is affecting the health of many women [due to exposure to Sexually Transmitted Infections - STIs.9

A study by Fiorella et al. (2015) highlights that transactional sex in fisheries is strongly linked to access to fish, with fish catch reductions leading to increases in transactional sexual relationships. COVID-19 induced reductions in access to fish might have exacerbated this trend, with women pushed further towards transactional ‘sex for fish’ practices, exposing them to serious health risks. In Nigeria, some female fishmongers engage in the practice (sale of sex) to support their families. COVID19 worsened these women’s vulnerability: as fishmongers who are single mothers, and with no male income in the household, they sold sex to feed their children, having lost access to the market and no protection from the state.

…[the] single mothers were hit hard. With no fish to sell or support from anyone, they turned to begging. The people they are begging from are also struggling to survive. In extreme cases, some of them turned to ‘selling sex’ to make money to feed their children … Women are still suffering. Nobody cares about the women.10

While the sex economy in fisheries typically highlights the vulnerability of women in SSF who sell ‘sex for fish’ to ensure access to fish from fishermen, women are not the only ones who commodify their bodies to protect their fisheries livelihoods. A corollary phenomenon of ‘sex for finance’ whereby fishermen trade sex to secure financing from female fish financiers has been suggested in West African fisheries.11 The existence of a ‘sex for finance’ dimension of the fisheries sex economy mirrors a broader practice of the participation of men as providers of sex in transactional sexual relationships, as evidenced by Mojola (2014). The participation of men as providers of sex in the fisheries sex economy highlights once again that vulnerability is neither a natural nor exclusive attribute of women. The ‘sex for finance’ phenomenon among men in fisheries evidence that men, too, respond to their fisheries vulnerabilities, distinct from those of women, by deploying harmful coping mechanisms. Furthermore, the easy association between women and vulnerability renders this particular vulnerability among men largely invisible (Javanbakht and Ragsdale, 2019). Further research is needed to understand how commonplace the ‘sex for finance’ phenomenon is and how much it might have been heightened by COVID-19.

The sex economy of SSF aggravates the vulnerability of women within the sector and introduces a space for vulnerability among men that is largely invisible. Engagement in transactional sex for fish and financing thus forms a harmful coping strategy that both women and men employ to ensure their fisheries’ livelihoods and meet their household needs. In response to increasing competition for fish, and the lack of finance, which COVID-19 disruptions have exacerbated, women in SSF turn to the harmful coping strategy of transactional sex and confront increased health risks. Fisheries’ livelihood disruptions are also experienced by men, whose livelihoods are more secure but still precarious, and who are also turning to ‘sex for finance’ in response to SSF disruptions. Yet, a gendered examination of resilience that solely criticises responses to adversity also risks perpetuating the ‘tendency to use a language of victimhood and vulnerability when discussing women’ (Smyth and Sweetman, 2015:409). Persistent inequalities along gendered lines in SSF in the GOG have constructed distinct vulnerabilities for women within the sector. The preceding discussion has demonstrated how COVID-19 responses have reproduced and amplified these gendered vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, it is necessary to recognise that while the socially constructed vulnerabilities of women impact (and limit) their capacities and opportunities for resilience, it does not prohibit their resilience.

The negative examples of resilience in the fisheries sector sometimes mask the positive strategies that women in the SSF in the GOG have deployed to build resilience to their vulnerability amidst COVID-19 disruptions. These positive resilience strategies are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Positive Coping Mechanism: Examplar of Ocean Optimism in the Gulf of Guinea

Self-Mobilising to Implement Measures

As highlighted in previous sections, women’s fisheries contributions are largely informal and un(der)valued, resulting in their institutional invisibility within fisheries policymaking and governance. These long-standing invisibilities marginalise women in fisheries response measures to mitigate the disruptions caused by COVID-19 (Okafor-Yarwood and van den Berg, 2021). Their institutional marginalisation has led women in SSF in the GOG to self-mobilise in creative and independent ways to cushion the shocks of COVID-19 disruptions.

In the Volta Region of Ghana, reduced access to markets due to lockdown and the closure of international borders resulted in innovative ways of marketing fish. An interviewee noted:

During the COVID-19 lockdown, [the income generated by fish sellers was significantly reduced]. They found a more innovative way of selling their fish as a result. [They] dispatched large parcels of fish to customers using the local inter-city private sector taxi cabs or minibuses. [They] used mobile money transactions to receive the payments before sending the fish. Though the profit was not as much as [they] could have gotten if [they] sold in person at the various market centres, the expenses was reduced as [they] did not have to travel all the time therefore reducing risks of contracting [COVID-19] or spreading it.12

This innovative way of selling their produce leverages transportation options and digital solutions to ensure access to consumers while minimising risks of exposure to COVID-19 among female fishmongers. Women processors additionally installed and enforced sanitation and social distancing measures at processing sites and markets. In Côte d’Ivoire, the women’s fisheries cooperative USCOFEP-CI raised awareness of social distancing requirements among women fish processors. Limited support from the government meant that these women had to initially finance their own sanitary kits, including purchasing face masks and hand washing stations at the height of COVID-19 restriction measures in 2020. Although these kits were later funded by external actors, the additional operating costs depleted women’s already meagre financial resources and heightened overall feelings of institutional neglect among them.

Further, poor health and sanitary conditions of fish landing and processing sites have perennially plagued SSF throughout the GOG and cause highly gendered health risks for women in the sector. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, low processing capacities and hazardous fish processing practices typify the landing and processing sites where women’s SSF work largely occurs. More than merely shining a light on these poor working conditions, COVID-19 has also offered an opportunity to address these long-standing problems and build back better (UN, 2020). Reports from CFFA in Côte d’Ivoire evidence optimism among women fish processors who view the ‘pandemic as an opportunity to address these issues’ (Philippe, 2020a). The need for such a transformative approach to addressing the challenges of COVID-19 is underscored by the FAO (2020b) which emphasises that ‘current challenges should be taken as opportunities for governments to create better sustainability systems for fisheries’ that align with a ‘human rights approach’ (FAO, 2020a:13). Such a human rights approach must centralise the challenges of ‘the most affected and vulnerable groups along fisheries’ value chains, which crucially includes women FAO, 2020a:12).

Union of Cooperative Societies of Women in Fisheries and Assimilated of Côte D’Ivoire (USCOFEP-CI)

In the GOG, women’s cooperatives provide important ‘safety nets’ for women in fisheries and work to empower women in the face of persistent SSF marginalisation and neglect (Okafor-Yarwood and van den Berg, 2021).

In July 2020, USCOFEP-CI acquired a forty-foot refrigerated container in the Ivorian San Pedro port with external support from the European Union (EU) to combat fish spoilage in fish processing. Women fish processors highly celebrated the container’s arrival as a step towards achieving their economic independence (Philippe, 2020b). However, with reduced demand due to COVID-19, this container is yet to operate at its full potential. Notwithstanding the limitations that COVID-19 has placed on the container’s operating potential, it remains a positive achievement for women in Côte d’Ivoire’s SSF, who would suffer higher fish losses without it. According to USCOFEP-CI Chairwoman Micheline Dion:

Although the container is currently half-empty due to COVID-19 disruptions, it mitigates fish loss through spoilage by providing women processors and sellers with the ability to preserve and store their fish for longer periods. This is vital given reductions in consumer access and demand induced by COVID-19 restrictions.13

According to the FAO (2020a), fisheries cooperatives have ‘played a vital role during the COVID-19 pandemic’ (4) to ensure labour continuity, overcome challenges and coordinate fisherfolk. For women in SSF, the FAO stresses the role of cooperatives in providing women with access to information and resources during the pandemic (FAO, 2020a). In Vietnam, Ferrer et al. (2021) found that women’s cooperatives significantly enhanced awareness of COVID-19 and how to prevent it. In Cote d’Ivoire, USCOFEP-PI has been actively responding to the impacts of COVID-19 through sensitisation campaigns at landing sites about social distancing requirements and through lobbying and advocacy on behalf of women in SSF by calling upon the government and the EU to implement adequate and inclusive response strategies in SSF (Philippe, 2020a). The narrative is similar in Ghana, Togo, and Benin, where fishing cooperatives have worked collectively to support their members and sensitise them on the health advisory measures for preventing COVID-19.14 COVID-19 has made much of the work done by cooperatives impossible, as they are no longer able to conduct the fundraising activities upon which they rely, and external funding is ad-hoc and inadequate.15 As Ferrer et al. observe, fisher’s cooperatives ‘need to be strengthened’ (2021:104) to better support their respective communities to build back better in a post-COVID-19 world.

In response to the limitations that COVID-19 disruptions have placed on cooperative support for women in SSF in Cote d’Ivoire, and confronted with mercurial support from institutional actors such as the government and the EU, USCOFEP-CI is carving a creative path to resilience through an unexpected ally. In 2021 the cooperative entered a partnership with Conservation des Espèces (CEM) – a marine conservation NGO whose mission is to protect marine and coastal ecosystems and promote local community participation and sustainable development for these purposes. CEM focuses on protecting marine turtles and their habitats, and partners with local coastal communities to achieve this. In exchange for cooperative and community members ‘leaving the turtles alone’, discouraging turtle poaching and encroachment on their habitats, and aiding CEM in monitoring turtle population numbers and movements through reporting turtle sightings, CEM will provide the cooperative with a cold room and ice factory for women in SSF. Like most conservation efforts, there is a risk of negative implications on fisherfolk and other members of communities who might feel excluded. However, the project’s collaborative nature would allow for the concerns of fisherfolk to be taken into account and addressed accordingly. CEM also works with hotels in Grand Bereby and San Pedro in Côte d’Ivoire to promote eco-tourism, which may provide additional livelihood benefits for women in SSF in the region, in the form of increased demand for fish from expanded tourism.16 Further research is needed to understand the implications of CEM’s project on coastal livelihood.

West Coast Women Ambassadors (WWA), GHANA

The West Coast Women Ambassadors (WWA) has worked with fishing communities in Ghana to set up a Community Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA) to provide financial services. The WWA is a civil society women’s organisation formed in 2010. Their objective is to socially and economically empower women, especially single-parent female-headed households in the coastal-fishing communities in the Western and Volta Regions of Ghana. The COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant lockdown depleted the business capital of many women in the fish trade value chain through fish spoilage inflicted by the difficulty in reaching markets or spending their trading capital in meeting the needs of their families. As the lockdown eased, WWA sought ways to support these women to organise and support each other since they do not have access to loans from financial institutions. To this end, in April 2021, they set up the VSLA to bring financial services closer to members and to act as a rallying point for initiating necessary legitimate community development activities such as sustainable fishing, farming, education, literacy/numeracy, business education and ecosystem management. As of September 2021, WWA’s VSLA operates in two communities, Whuti (Anloga District), and Vodza (Keta Municipal) both in the Volta Region of Ghana. There are currently 50 members each in two groups in Whuti community comprising fishmongers, farmers and petty traders, with each member contributing 20 Ghana Cedis per week (90% of whom are women). There is also one group of 80 members in the Vodza community (98% are women). Since the VSLA started in April 2021, other communities have shown enthusiasm to introduce similar initiatives. 17

The work of the VSLA illustrates how resilience is fostered when people are organised and presented as a group. In June 2021, the VSLA in the Whuti community secured a loan with the support of WWA. Up to 2000 Ghana Cedis each was made available for 40 members to borrow if they wanted it. WWA provided the institutional support to secure the loan from the Business Advisory Centre (BAC) in Sogakope, South-Tongu Municipality, Ghana, which transferred it through the local Anlo Rural Bank. BAC is a state public agency that provides business advisory and training services and marketing avenues to micro and medium scale business enterprises. BAC was convinced to give the loan because WWA made a strong case for the VSLA as an organised group, presenting evidence of their VSLA contributions. The total loan made available to the VSLA members was 45,000 Ghana Cedis, which they have invested in their businesses. WWA is overseeing the repayment of the loan, which is done in agreed-upon flexible weekly instalments.18

The Gendered Complexities of Coping Strategies

The previous two sections discussed COVID-19 responses among women in the GOG’s SSF as falling into the categories of either harmful (or negative) coping mechanisms, which seek to alleviate the disruptions caused by COVID-19 while simultaneously heightening other threats and vulnerabilities among women in the sector, or positive resilience strategies, which comprise responses that enable women to not only survive the adverse effects of COVID-19 disruptions but which also contribute to their longer-term abilities to thrive in the face of disruption. However, a binary understanding of responses oversimplifies the complexities contained within them. The third and final part of our discussion examines the gendered complexities of these strategies as response measures whose deployment are highly gendered in construction and in the distribution of their benefits.

The Gendered Distribution of Digital Solutions

Following market closures, reduced access to consumers gave rise to digital marketing solutions to directly connect fisherfolk to consumers (FAO, 2020a). The introduction and proliferation of these digital solutions are both global and emblematic of broader trends in COVID-19 responses across sectors, that have increasingly turned to digital spaces to replace physical interactions. As highlighted above, women in the GOG’s SSF have leveraged digital solutions to ensure consumer access and the continuation of their fisheries livelihoods through the use of mobile money. However, a critical gendered examination of digital solutions in SSF for the GOG also reveals significant dangers inherent in this widely celebrated coping mechanism and highlights its limitations and harmful implications.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic wherein restrictions resulted in the shutdown of the supply chain in South Africa, fisherfolk pivoted from delivering to restaurants to supplying fish to homes and have now also launched a product line that customers can use to order online (http://fishwithastory.org/). In South Africa, the Abalobi app exemplifies how technology has been leveraged to support the SSF sector (http://abalobi.org/about/). The South African example demonstrates how a short-term coping strategy can evolve into a long-term tool for adaptation and potentially add to fisherfolk resilience through this initiative.

Online fish selling as a coping mechanism and strategy for adaptation is also evidenced in the GOG. In Ghana, an online fish startup called Loojanor, created in 2018 to connect fishers with consumers, has offered an alternative to the traditional market (CFFA, 2020b). The success of this initiative has evolved into a thriving adaptation at the heights of the pandemic as the company has now expanded its partnerships with other stakeholders in the Ghanaian food sector.

The use of digital spaces as a coping strategy for COVID-19 disruptions has been both prolific and highly celebrated, showing how technology can be utilised as a long term adaptation tool in the SSF as fisherfolk sought to build back better in a post-COVID-19 world. However, despite the role that digital solutions played for some fisherfolk at the height of the pandemic, access limitations remained a significant challenge for the majority of fisherfolk and are discussed here in three areas; along geographic, socio-economic, and gendered lines, to highlight the fact that they are discriminatory digital spaces that may be reproducing food and income insecurities rather than alleviating them.

The first problem associated with digital solutions to COVID-19 disruptions in SSF in the GOG relates to internet access. Fundamentally, these digital solutions connecting fisherfolk to consumers require high internet penetration to present a viable alternative to physical marketplaces. A recent report by the Institute of Labour Economics (Rodríguez-castelán et al., 2021:3) describes West Africa as a ‘subregion with one of the lowest levels of mobile internet penetration in the world’. While Nigeria boasted an internet penetration of 73% in 2020 (the third highest in Africa) (Statista, 2020), most countries in the GOG are characterised by low access to the internet. As of 2020, internet penetration in Angola, Liberia and Sierra Leone stood at 26.5%, 14.7% and 12.8%, respectively (Statista, 2020). Therefore, the appropriateness of digital solutions for fisherfolk in response to COVID-19 disruptions is extremely limited for most countries and people in the GOG. These country-level statistics do not reflect variation in internet penetration at the sub-national level, which is inevitably higher in urban centres and much lower in rural coastal communities (see: Broadband Commission, 2021:35). The need for high internet penetration for digital solutions in SSF to be effective and its corresponding absence throughout much of the GOG reveals a deeply urban and rural divide in West African contexts.

Related to the divide in urban-rural digital access is the socio-economic nature of digital access. This implies that online fish marketing solutions are highly susceptible to elite capture, further marginalising fisherfolk and consumers who lack access to the requisite digital tools and literacy required to benefit from such initiatives. Digital solutions for SSF in the face of COVID-19 demand disruptions in the GOG may thus further reduce access to fish for the most impoverished fisherfolk in the SSF sector and the most food-insecure consumers. The potential for elite capture of SSF through digital solutions in response to market closures and reduced consumer access is evidence of disaster capitalism at work by conditioning access to consumers and fish – a crucial source of nutrition – on digital access.

A third access challenge is the gendered digital divide. Digital access is highly gendered due to systemic socio-economic advantages that give men higher access to education and income than women. The need to reduce the digital divide for women and men in fishing communities and the higher digital access challenges women face in Mexico were highlighted in a recent report by COBI (2020). Ferrer et al. (2021) also draw attention to the gendered digital divide in the SSF sector in Southeast Asia, highlighting that while e-commerce has become a common fish marketing response, ‘the skills in online marketing and fish handling techniques of small-scale fishers, especially women and young people, still need to be enhanced’ (Ferrer et al., 2021: 107).

A similar gendered digital divide exists in fishing communities in the GOG, where women exhibit lower levels of education, literacy and have lower incomes than men, all of which interact to limit their abilities to access digital spaces. In a case study on women in Nigeria’s SSF, Zanna and Musa (2020) found that 37.4% of sampled women were illiterate. They conclude that women’s overall educational status in the fisheries sector is inferior compared to men’s. This is further complicated by the fact that women barely receive training on the use of digital technology. Reinforcing this point, the fisherfolk (women and men) that contributed data to this research have noted that they too, hardly receive any technological training/education. Although fish processing and marketing can be labour intensive and time-consuming, technologies have not been simplified adequately enough to motivate women to adopt them. The gendered digital divide that prevents women from benefiting from digital solutions as a response to COVID-19 disruptions is evidence of disaster patriarchy that fails to integrate the particular and pre-existing disadvantages that women in SSF in the GOG face, thereby perpetuating both their invisibilities and inequalities in these response measures.

Access challenges along geographic, socio-economic (elite) and gendered lines significantly reduce the reach and appropriateness of digital solutions as a path to resilience for fisherfolk in the GOG. The gendered limitations of these digital solutions may further marginalise women in fisheries (albeit unintentionally) by removing the need for physical markets, where women dominate the workforce. Specifically, in replacing traditional real-world markets, these digital solutions are intended to cut out the middleman by connecting fisherfolk directly to consumers. Given the concentration of women in the fisheries value chain in the GOG, these solutions, in reality, cut out the middle woman. Therefore, a gendered interrogation of digital solutions in SSF showcases that availability should not be conflated with accessibility. While growth in digital spaces for fisherfolk in SSF has increased the availability of these solutions, the accessibility of these solutions is highly gendered. So too is the distribution of digital solution benefits, which privilege men and marginalise women. Further research is needed to interrogate the gendered distribution of benefits associated with the implementation of such digital solutions.

The Burden of Diversification

Recommendations to improve fisher household resilience when confronted by disruptions include ‘diversifying livelihood(s) to reduce dependency on the fishery and provide for additional sources of income and food’ (Ferrer et al., 2021: 99). Diversification of income sources for small scale fisherfolk is a common practice by both men and women as a potential way out of poverty (de Steenhuijsen Piters et al., 2021; Roscher et al., 2022). However, we focus specifically on diversification by women in fisheries due to the extent to which they dominate diversification in fishing businesses (see: Gopal et al., 2020; Gustavsson, 2020).

Throughout West Africa, in addition to working in the fishing value chain, most women also separately engage in vegetable gardening or farming. In Ghana, women in the fishing value chain often engage in other economic activities such as retail trading in consumables – condiments for preparing meals and soap. Others are seamstresses, hairdressers, or bakers. All these go to supplement the family’s income, particularly during periods of low fish catches (Johnson and Boachie-Yiadom, 2011). In Nigeria, the extent to which women diversify is dictated by access to capital. As a result, many of the women are unable to diversify due to the lack of finance. However, those with access to capital work in the fishing value chain and operate ‘Petti-stalls’ where they sell provisions and food items. At the same time, others also sell ‘Okrika’ – second-hand clothing.19

The evidence of resilience among women in SSF in the GOG amidst COVID-19 and the general adversity they face in the fishing sector is cause for a degree of ocean optimism. Across the GOG, women in SSF have responded to the highly gendered disruptions brought on by COVID-19 and persistent institutional marginalisation not with inaction but with adaptation. Women have self-mobilised to ensure the continuation of their fisheries livelihood activities. Women-led fisheries cooperatives have provided critical support and responded to limitations caused by COVID-19 disruptions by galvanising creative solutions with unexpected allies, including through diversification.

However, this ocean optimism is not without qualification. As evidenced above, women’s diversification responses to disruptions within their fisheries livelihoods are widely regarded as evidence of their resilience. However, the appropriateness of such celebratory assessments merit interrogation. Luft’s (2016) model of disaster patriarchy and criticisms of resilience put forward by Shwaik (2021) and MacKinnon and Derickson (2013) remind us of the need to interrogate the gendered inequalities contained within and perpetuated by the discourse of diversification. The gendered burden of diversification is underpinned by patriarchal assumptions inherent to whose livelihood activities are recognised as important and therefore consequently protected. Women working in SSF have always needed to diversify their income sources, as gendered earning gaps and invisibilities limit their earnings potential within the sector. This is compounded by the fact that they carry a disproportionate responsibility to ensure the food security of their households (Thorpe et al., 2014).

The feminisation of poverty thesis holds that women experience a higher incidence of poverty as compared to men. Chant (2008:176) interrogates the analytical problems contained within this widely accepted proposition and argues that ‘perhaps more important’ than the feminisation of poverty is the ‘feminization of responsibility and obligation’ that places women’ increasingly at the frontline of dealing with poverty’. The primary responsibility placed on women to ensure ‘household survival’ (Chant, 2008: 182) pushes them to diversify and intensify their inputs towards household survival. Thorpe et al. (2014) highlight the feminisation of poverty for women in SSF in Sierra Leone and argue that variegated access to capital that disadvantages women based on their gender and the multiple roles that they must occupy as a result of gendered expectations pushes them to diversify by deploying coping strategies like labour substitution towards or away from fisheries (Thorpe et al., 2014). They further add that almost half of women in Sierra Leone’s SSF diversify their incomes through non-fishing activities, while men in SSF are conversely far less likely to have diverse income sources. This further perpetuates the feminisation of poverty by ensnaring women in the need to prioritise short-term consumption smoothing at the expense of being able to engage in longer-term profitable investments that requires specialisation.

It follows that women’s responses to COVID-19 fisheries disruptions by diversifying their livelihoods is nothing new. Rather, it is an extension of the resilience they have been forced to develop due to enduring gender inequalities and expectations in SSF. Positive assessments of women’s diversification strategies in response to COVID-19 disruptions without qualification of the contexts thus risks reinforcing gendered expectations that force women to balance and navigate multiple roles. At the same time, men are afforded the luxury to continue specialising, benefiting from response measures that protect their livelihoods. Ultimately, the gendered diversification trends in SSF due to COVID-19 disruptions thus illuminate a bitter truth: women are apt at diversifying because they have never been provided with the security that would enable them to specialise. Evidence from Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire reveals that fishermen loiter along the shores in the face of fishing disruptions, waiting for their turn to fish (CFFA, 2020a; Darko, 2020). In Sierra Leone, fishermen have even responded to restrictions with violence (Kamara, 2020). Meanwhile, women within the sector cannot risk inaction or violence, given their centrality to ensuring food security at the household level. Thus, whilst women continue to exhibit resilience in times of adversity through diversification, we must exercise caution in its advocacy.

Implications and Conclusion

SSF plays a vital role in millions of people’s food and economic security throughout the Gulf of Guinea (Okafor-Yarwood, 2019). Though both men and women are affected by vulnerabilities in the sector, the gender inequalities that pervade it renders women in fisheries particularly susceptible to the disruptions in SSF (Okafor-Yarwood and van den Berg, 2021). The adverse effects of COVID-19 caused by disrupted demand, distribution, labour, and production have worsened the vulnerabilities of SSF, particularly for women therein (FAO, 2020b; Love et al., 2021). To understand the responses deployed by fisherfolk in the face of COVID-19 disruptions, and their gendered dimensions, we critically analysed the concept of resilience. While resilience is often projected as something positive (Kolar, 2011; USAID, 2012; UN, 2015), we argue that some strategies intended to build resilience further exacerbate societal vulnerability writ large. This is demonstrated most clearly in how some coping mechanisms deployed by women in SSF in response to COVID-19 disruptions place them at further risk: to STIs and other harmful behaviours. These findings challenge an uncritically positive narrative of resilience. We also shared examples of ocean optimism in the GOG to show some of the positive examples of resilience, evidenced in the coping strategies adopted by women in the face of their adversities. Finally, we also revealed the grey zone of gendered complexities through assessing responses to disruption that cannot neatly be understood as simply either harmful coping mechanisms or positive resilience strategies, due to the patriarchal construction and gendered distribution of benefits that accompany the deployment of digital solutions and diversification in SSF.

For fisherfolk, especially women, to be truly resilient in the face of adversity, they need to get to the point of transformation, wherein they can not only return to the previous level of welfare before the COVID-19 disruptions but become empowered. Achieving this requires states, governments, NGOs and CSOs to actively address the root causes of the challenges fisherfolk face and invest in infrastructure that enables the sector to transcend beyond recovery to transformation. For instance, to close the gendered gap between digital solution availability and accessibility investment, an effort must be made in enhancing the digital infrastructure of the GOG; specifically, greater priority needs to be given to digital skills training for women (Afram et al., 2021).

We also caution against perpetuating the gendered discourse of diversification in SSF, which by applauding women’s capacities to diversify ensnares them within patriarchal poverty-spirals of short-term consumption smoothing. Instead, we call for the protection and promotion of women’s SSF livelihoods by granting them greater institutional visibility, recognition, voice, and opportunities for sustainable fisheries participation. This requires multi-level action and investment by governments, fisheries management bodies, NGOs and other actors. In Nigeria, Eja-Ice, a private company dedicated to creating environmentally friendly opportunities for women in Africa, provides solar-powered refrigeration for women fish traders, and was founded to address high fish spoilage in Nigeria and its particularly devastating impacts for women fish traders. According to the company’s annual impact report, in 2020 Eja-Ice refrigeration and cold-chain solutions for women in Nigeria’s SSF saved 133,760 fish from being wasted – accounting for 40% of total fish sales among their female fish-trader clients. This type of targeted support is thus significantly contributing to empowering the fisheries livelihoods of women in SSF in Nigeria, offering them technological security and allowing them to ensure and grow their fisheries livelihoods instead of pushing them to diversify to meet their livelihood needs (Eja-Ice, 2020:8).

Women’s cooperatives in SSF also play a pivotal and innovative role in lobbying for and advancing women’s recognition, empowerment, and participation within SSF. However, the absence of reliable support for these cooperatives makes them vulnerable to disruption and limits the consistency of their capacities to champion women in SSF. Financial support and institutional recognition of the vital role that women’s fisheries cooperatives play in supporting women in SSF needs to be ensured and institutionalised at national and regional levels to enable these cooperatives to effectively empower women in SSF. Further cultivation and expansion of these and other efforts to promote and protect women’s SSF livelihoods is critical to dismantling the gendered vulnerabilities that define SSF and to dismantle the patriarchal foundations of SSF resilience.

The full empowerment of women in SSF requires addressing the root causes of gender inequality that define their vulnerabilities in SSF and constrain their capacities for resilience, as well as acknowledging and addressing women’s participation in constructing vulnerability within the sector and in the sex economy of fisheries in particular. Evidence from our research of men’s participation in ‘sex for finance’ with female fish financiers in fisheries also indicates that easy assumptions that reduce women to vulnerable ‘victims’ in such exchanges prevents recognition of the role they may play in embedding the fisheries sex economy; we thus run the risk of marginalising the vulnerability of men in such transactions. Promoting and protecting legitimate and sustainable fisheries livelihoods among women may serve to deter the participation of female fish financers in this ‘sex for finance’ phenomenon, while greater agentive integration and recognition of women’s participation in fisheries can broaden understandings of vulnerability to grant greater visibility to the exploitation of men within transactional sex practices in the SSF sector.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, with the consent of the research participants.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the School of Geography and Sustainable Development, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

IO-Y conducted the field research and telephone interviews, SB participated in online interviews, IO-Y and SB wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; YAC provided extensive feedback and edited the initial version of the manuscript; CS-N edited and provided feedback on the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the corrections. All authors participated in the monthly meeting to discuss research progress. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The University of St Andrews Restarting Research Funding Scheme (SARRF) is funded through the SFC grant reference SFC/AN/08/020. The University of St Andrews Institutional Open Access Fund (IOAF) is acknowledged for open access support.

Conflict of Interest

Author IO-Y is an Advisory Board member at Eja-Ice'.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the useful insights from various stakeholders that contributed to our research. Their contributions motivated us to think critically about how fisherfolk, especially women, are disproportionately affected by adversities in the fisheries sector and how they are overcoming these challenges, despite limited support from the government. We are grateful to Mr Kwesi Randolph Johnson for facilitating the engagement with fisherfolk in Ghana and the Coalition for Fairer Fisheries Agreements for facilitating our initial engagements with Union des Sociétés Coopératives des Femmes de la Pêche et assimilées de (USCOFEPCI), in Cote d’ Ivoire.

Footnotes

- ^ Interview with USCOFEP-CI was supported by the Coalition for Fairer Fishing Agreement (CFFA); they also made their online Zoom translation software available to us.

- ^ Whuti and Sroegbe communities are in the Anloga District, one of the 18 districts in the Volta Region. The residents are predominantly fisherfolk, and the local language is Ewe. The Region (Volta) is one of Ghana's sixteen administrative regions. It stretches from the coast of the Gulf Guinea through all the vegetative zones found in Ghana (i.e. coastal-savanna, forest, transitional and savanna zones). The region is multi-ethnic and multilingual, with three main groups: Ewe, Guan, and Akan. Gomoa-Fetteh, in the Gomoa-East District, is one of the 16 District Assemblies in the Central Region. The residents are predominantly fisherfolk, and the local language is Fante. The Central Region is located in the South of Ghana and the centre of the country's 550-kilometre-long coastline. The region has the longest coastline in the country at 150km and is amongst four on Ghana's coast, bordering the GOG section of the Atlantic Ocean. The other regions on the coastline are (from east to west) Volta, Greater-Accra, Central and Western Regions. Abidjan is the economic capital of Cote d'Ivoire. It is located in the Ébrié Lagoon on the coast of the Gulf of Guinea. Bonny Island is situated in Bonny Local Government Area in Rivers State, in the Niger Delta area of Nigeria. The majority of the people on the island derive their livelihoods from fisheries. The island is also home to the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG) company.

- ^ Online interview with the woman leader, Bonny Indigenous Fishermen Cooperative Union, 29th June 2021. Despite the name, women who are fishers, fish processors, traders, and marketers indigenous to Bonny Island are part of this Union.

- ^ Interview with Micheline Dion, president of The Union of Cooperative Societies of Women in Fisheries and Assimilated of Côte d'Ivoire (USCOFEP-CI), 13/07/2021.

- ^ Focus group discussion with fisherfolk from Whitu and Srogboe Community, Anloga District, Volta Region, Ghana. 24th July 2021.

- ^ This analysis is surmised from the focus group discussion and interviews with fisherfolk and CSO representatives in from Ghana, Togo, Nigeria, and Côte d'Ivoire conducted between June and August 2021.

- ^ Focus group discussion with representatives of FENASCOOP-CI, 9th August 2021.

- ^ Interview with Micheline Dion, president of USCOFEP-CI, 13th July, 2021.

- ^ Interview with Mr Randolph Kwesi Johnson, a Sustainable Fisheries and Coastal Management Expert for the West Coast Women Ambassadors, Ghana, 25th June 2021. The excerpt he shared was from field research he did in April 2021.

- ^ Online interview with the woman leader, Bonny Indigenous Fishermen Cooperative Union, 29th June 2021. Despite the name, women who are fishers, fish processors, traders, and marketers indigenous to Bonny Island are part of this Union.

- ^ Insights from discussion with participants from Nigeria and Ghana.

- ^ Interview with Mr Randolph Kwesi Benyi Johnson, a Sustainable Fisheries and Coastal Management Expert, Ghana, 25th June 2021.

- ^ An excerpt from the interview with Micheline Dion, president of USCOFEP-CI. 13th July 2021 (online).

- ^ This analysis is based on the discussion with Micheline Dion, president of USCOFEP-CI online, on the 13th of July 2021 and in-person in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, on the 12th of August 2021.

- ^ Interview with Micheline Dion, president of USCOFEP-CI. 13th July 2021 (online).

- ^ Interview with Micheline Dion, president of USCOFEP-CI. 13th July 2021 (online).

- ^ Focus group discussion with Whittu Community in the Volta Region, Ghana, and interview with Mr Randolph Kwesi Benyi Johnson, a Sustainable Fisheries and Coastal Management Expert for West Coast Women Ambassadors Ghana. 24th July 2021.

- ^ Focus group discussion with Whittu Community in the Volta Region, Ghana and interview Mr Randolph Kwesi Benyi Johnson, a Sustainable Fisheries and Coastal Management Expert for Westcoast Women Ambassadors Ghana. 24th July 2021.

- ^ Online interview with the woman leader, Bonny Indigenous Fishermen Cooperative Union, 29th June 2021. Despite the name, women who are fishers, fish processors, traders, and marketers indigenous to Bonny Island are part of this Union.

References

Adger W. N. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environ. Change 16 (3), 268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006

Afram A., Afenyo-agbe E., Sefa-nyarko C. (2021). Digital Technologies Use Among Female-Led MSMES in Ghana: Access, Constraints and Options for Closing the Gaps. Available at: https://www.pdaghana.com/index.php/policy-briefs/item/download/142_38703551a15c3993e63ccfba40ed1a96.html.

Asiedu B., Nunoo F. K. E. (2015). “Declining Fish Stocks in the Gulf of Guinea: Socio-Economic Impacts,” in Assessment and Impact of Developmental Activities of the Marine Environment and the Fisheries Resources of the Gulf of Guinea. Accra: Department of Marine and Fisheries Sciences Reader. Ed. Ofori-Danson P. K., Nyarko E., Addo K. A., Atsu D. K., Botwe B. O., Asamoah E. K. Accra: Department of Marine and Fisheries Sciences Reader, 201–218.

Avtar R., Deepak S., Deha A. U., Ali P. Y., Prakhar M., Pranav N. D., et al. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on the Fisheries Sector : A Case Study From Three Harbors in Western India. Remote Sens. 13 (183), 1–20. doi: 10.3390/rs13020183

Béné C., Merten S. (2008). Women and Fish-For-Sex: Transactional Sex, HIV/AIDS and Gender in African Fisheries. World Dev. 36 (5), 875–899. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.05.010

Braun V., Clarke V. (2012). “Thematic Analysis” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Vol. 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, vol. 2 . Eds. Cooper H., Camic P. M., Long D. L., Panter A. T., Rindskopf D., Sher K. J. (Washington D.C: American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Broadband Commission (2021). Connecting Africa Through Broadband: A Strategy for Doubling Connectivity by 2021 and Reaching Universal Access by 2030. Available at: https://www.broadbandcommission.org/Documents/working-groups/DigitalMoonshotforAfrica_Report.pdf.