- 1Law School of Artificial Intelligence, Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China

- 2International Law School, Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China

The evolving maritime security landscape and rapid advancements in intelligent technologies have increased the importance of unmanned vehicle systems (UVSs) in maintaining maritime security and order. This article employs comparative research methods to evaluate the respective capabilities of common UVSs, including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned surface vehicles (USVs), and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs). It assesses their suitability for different maritime law enforcement missions and examines the potential risks posed by their application. The findings reveal that UVSs are highly versatile in conducting various maritime law enforcement missions. However, their use introduces complex legal challenges under existing international law, resulting in legal uncertainties that may hinder the responsible development and deployment of UVSs in this domain. In addition, UVSs face emerging cybersecurity threats related to networks, data, and artificial intelligence. In response, the article proposes establishing an evaluation framework that aligns law enforcement objectives, system capabilities, and associated risks to guide maritime agencies in determining strategic UVS deployment priorities. It also emphasizes the need to rely on subsequent state practice as a means of addressing the challenges posed by current international legal frameworks. Furthermore, enhancing security risk management through lifecycle strategies offers an effective way to support the broader adoption of UVSs in maritime law enforcement.

1 Introduction

In recent years, regional disputes over national maritime rights have intensified. Tensions over law enforcement in the South China Sea, anti-piracy operations in West Africa and Southeast Asia (IMO, 2025b), maritime counter-narcotics efforts (McLaughlin and Klein, 2021), and global enforcement against illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing (Welch et al., 2022) highlight the complex and multifaceted nature of maritime law enforcement. These challenges underscore the pressing need for more effective maritime law enforcement strategies. The advent of new technologies, particularly unmanned maritime systems including UAVs, USVs, and UUVs, is transforming maritime law enforcement in the era of artificial intelligence (AI). This technological evolution marks the future trajectory of unmanned maritime systems. It holds significant promise for enhancing the effectiveness of law enforcement, particularly in areas such as maritime situational awareness, patrol alerts, and strategic maneuvers (Bae and Hong, 2023; Lv et al., 2025).

Marine UVSs encompass autonomous systems and associated equipment capable of navigating independently in the ocean under remote human control or predetermined programs. Their autonomy is demonstrated through the integration of AI for functions such as navigation and target identification (Grand-Clément and Bajon, 2022). Early UVSs were entirely controlled remotely by human operators. With advances in AI, UAVs and USVs now possess sophisticated autonomous decision-making capabilities, including route planning, collision avoidance, target recognition, and tracking (Ayala et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025). Equipped with onboard cameras, acoustic sensors, surface radars, satellite communication systems, and integrated power units, these vehicles enable continuous, and cost-effective intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations in remote maritime areas, thereby reducing reliance on manned patrols (United States Coast Guard, 2023). Moreover, the deployment of this new technological equipment can reduce human error and the risk to human life, particularly during hazardous maritime law enforcement operations. Their unmanned nature enhances mission precision and efficiency, enabling coverage of larger areas and execution of tasks beyond human capabilities. In the maritime domain, UVSs support relevant authorities in delivering rapid and effective enforcement responses by supplying data, such as video and imagery—captured by their onboard suites of sensors, radars, cameras, and identification systems (Durmuş, 2023; Patterson et al., 2022).

The advent of UVSs not only provides nations with more persistent and wide-ranging maritime enforcement coverage but also allows traditional maritime vessels and aircraft to be reassigned to more complex missions. In regions such as the Mediterranean, which serves as a strategic crossroads between continents, various maritime crimes exhibit transnational characteristics, including terrorism, arms smuggling, drug trafficking, and illegal migration. UAVs and USVs play a critical role in enhancing maritime surveillance in the Mediterranean, by enabling continuous patrols and facilitating effective early detection. These autonomous systems offer a more efficient, cost-effective, and sustainable solution for monitoring illegal maritime activities compared to conventional maritime and aerial assets typically used in routine surveillance and interdiction operations (Fantinato, 2021; Argüello, 2023) As a result, an increasing number of countries are adopting these technologies for maritime security and law enforcement purposes (Coito, 2021; Cheng, 2025).

As marine UVSs become more widely adopted, these technological assets have the potential not only to transform the maritime domain into a more efficient and reliable system, but also to pose threats to navigational safety in waters under other nations’ jurisdiction. A notable example is the 2016 Bowditch UUV incident in the South China Sea (Liu and Feng, 2025). At present, international conventions concerning unmanned maritime systems remain underdeveloped. Even the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides no direct normative framework and fails to offer effective legal mechanisms for regulating UVS navigation from the perspective of international law (Chang et al., 2020). Consequently, relevant regulations are generally applied through analogical interpretation or by analogy. UVSs have been extensively discussed in both academic and operational contexts, with particular attention to their legal status, technological development challenges, and deployment readiness (Yan et al., 2010; Barrera et al., 2021; Bolbot et al., 2023; Shao et al., 2024).

To assess the current state of research on UVS in maritime law enforcement, a comprehensive literature review was conducted in databases including Web of Science, CNKI, and Science Direct using keywords such as “Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,” “Unmanned Surface Vehicle,” “Maritime Autonomous Vehicle,” and “Unmanned Underwater Vehicle.” In addition to academic literature, this article also investigates practical applications and policies drawn from the official websites of maritime law enforcement agencies across multiple countries. Building upon existing research findings in UVS, this article aims to examine the impact of a shift toward the integration of multiple types of UVSs on the future of national maritime law enforcement—an area that existing literature, which has primarily focused on single-type systems, has largely overlooked. Due to the diversity of UVSs, it is essential to investigate the disparities among them to enable more accurate task assignment by maritime law enforcement agencies. Therefore, this article employs an integrated portfolio of research methodology to examine the application of UVSs into maritime law enforcement. Its core activities include two specific and synergetic strands. First, throughout this article stands a crucial method of comparative studies. This method is invoked to identify the discrepancies among various categories of UVSs and to explore their mission applicability for the deployment in maritime law enforcement. This comparison is structured around the core observation that different types of UVSs exhibit varying technical capabilities and functional strengths, making integrated deployment particularly valuable for enhancing the effectiveness and adaptability of maritime law enforcement operations. Second, the legal doctrinal method is applied in the doctrinal analytical dimension of this article to investigate the compatibility of UVS operations with existing international maritime legal instruments and policy documents such as UNCLOS in deploying UVSs. This combined approach allows for a holistic assessment of both the opportunities and the challenges presented by UVSs, forming a solid foundation for the subsequent recommendations aimed at optimizing their deployment in maritime law enforcement.

Following the introduction, Section 2 analyzes the characteristics and capabilities of the main categories of maritime UVSs. Section 3 explores the compatibility of UVSs with current maritime law enforcement scenarios and practices. Section 4 identifies the key challenges associated with applying these systems in law enforcement contexts. Section 5 provides recommendations for improving the use of UVSs in maritime law enforcement, and Section 6 concludes the discussion.

2 The types of marine UVSs and their functional niches in maritime law enforcement

To meet the multifaceted demands of maritime security, defense and management, national maritime law enforcement agencies are typically equipped with a diverse array of ships, aircraft and specialized vessels (e.g., survey ships). In recent years, countries have placed increasing emphasis on safeguarding maritime rights and have further advanced the development of various high-tech equipment. Notably, the coast guards of the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore have integrated advanced unmanned systems into their routine operations (Klein, 2019; United States Coast Guard, 2023). The adoption of UVSs enhances coast guard capabilities in sustained surveillance and responses to complex scenarios, while also offering new avenues to augment maritime law enforcement beyond the limitations of traditional manned assets. At present, four distinct types of maritime UVSs are employed in maritime supervision and law enforcement.

2.1 Unmanned surface vehicles

USVs are autonomous maritime systems capable of self-navigation and mission execution,1 whose technological development has progressed from early remotely controlled vessels to highly autonomous platforms (Liu et al., 2016). Modern USVs leverage AI algorithms, advanced sensors, and communication technologies to perform complex operations with minimal human input (Heo et al., 2017a). According to US Navy standards, USVs are categorized into semisubmersible types, conventional planning hull types, hydrofoil craft types, and other specialized types. The first three are designed to operate in a range of sea conditions, from mild to severe, while the latter are suited for special missions in environments unsuitable for human operation. USVs are also classified by size into four categories: X-class (small, ~3m), Harbor class (7m), Snorkeler class (7m SS), and Fleet class (11m). Each is capable of handling maritime tasks of varying complexity, depending on factors such as manufacturing cost and onboard equipment (US Navy, 2007).With respect to autonomy—a critical dimension the International Maritime Organization (IMO) classifies Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) into four operational levels: Level 1 involves automated processes with decision support; Level, 2 includes remotely controlled ships with onboard seafarers; Level 3 includes remotely controlled ships without onboard seafarers; and Level 4 features fully autonomous ships (IMO, 2018). Although substantial progress has been made, most commercially available USVs still rely on conventional control modes such as waypoint navigation, station keeping, and collision avoidance, with remote control remaining a standard feature (de Andrade et al., 2025). Fully autonomous USVs equipped with comprehensive AI capabilities remain under development (Heo et al., 2017a), posing challenges to their widespread application in maritime operations. Nonetheless, some USVs are already capable of operating in swarm configurations2.

Collectively, USVs are characterized by their compact size and cost-effectiveness, making them particularly well-suited for sustained patrol missions across extended maritime zones and in hazardous environments (Bae and Hong, 2023). These operational advantages have accelerated their deployment in a growing range of applications, including marine environmental monitoring, offshore industrial activities, and maritime security operations (Piazzolla et al., 2025; Miętkiewicz, 2018). However, their operation without a crew on board also challenges the foundation of traditional maritime legal concepts, such as the definition of a “vessel” and the application of collision regulations.

2.2 Unmanned aerial vehicles

UAVs are commonly defined as an aircraft operated without an onboard pilot or controlled remotely (Bloise et al., 2019). There are two primary types of UAVs: fixed-wing and rotary-wing, each with its own advantages and limitations. Fixed-wing UAVs are widely used in military and defense contexts due to their high speed, large payload capacity, long-range capabilities, and broad coverage. However, they consume energy only to maintain forward motion and are incapable of stationary hovering, making them unsuitable for maritime operations that require position-holding. In contrast, rotary-wing UAVs are specifically designed for aerial surveillance of surface-level conditions, including maritime status monitoring, military equipment tracking, and related applications. Although they offer lower speeds and payload capacities compared to fixed-wing UAVs, they are capable of stationary flight. As a result, rotary-wing UAVs are well-suited not only for long-range maritime surveillance but also for nearshore inspection tasks (Laghari et al., 2023).

UAVs exhibit superior maneuverability, robust surveillance capabilities, and extensive coverage, often outperforming patrol vessels through their broader tracking range, reduced error rates, and faster task completion (Khairi et al., 2020). These attributes make them particularly suitable for operations aimed at safeguarding maritime sovereignty, significantly enhancing maritime law enforcement operations by enabling rapid response, extending the “right of hot pursuit,” and providing high-resolution evidence for prosecution. In specific maritime contexts, UAV applications have evolved significantly—from initial roles in maritime patrol and search and rescue (SAR) missions to rapid expansion into a wide array of domains, including marine safety and surveillance, environmental monitoring, communication and navigation, military and naval operations, anti-piracy efforts, augmented reality, and even maritime cargo handling (Wang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2019).

2.3 Unmanned underwater vehicles

UUVs are a type of submarine designed to perform underwater missions. Due to their unmanned nature, UUVs can be built smaller and at a lower cost than traditional submarines (Heo et al., 2017b). A key advantage of UUVs for maritime law enforcement is their ability to operate covertly and persistently in hazardous underwater environments without endangering human lives, while simultaneously delivering real-time data to maritime law enforcement officers and decision-makers. Compared to traditional submarines, UUVs are more stealthy and harder to detect, making them well-suited for reconnaissance and surveillance missions, during which they can collect intelligence undetected (Kraska and Pedrozo, 2022). This capability, however, raises legal issues regarding innocence of passage, territorial sovereignty, and the admissibility of evidence obtained by uncrewed platforms.

Similar to unmanned surface vessels, the level of autonomy in UUVs varies depending on mission demands and technological capabilities. At the lowest level of autonomy, UUVs are remotely controlled by operators via a tether or wireless connection. At an intermediate level, UUVs possess limited self-navigation capabilities, enabling them to follow predefined paths or execute specific tasks based on established parameters. UUVs operating at the highest level of autonomy incorporate sophisticated AI and machine learning algorithms that facilitate extended independent operation in complex missions without human intervention. These autonomous UUVs can carry out complex missions over extended durations, make decisions based on sensor-acquired data, and adapt to dynamic marine conditions (Ruhal, 2024).

UUVs offer versatile operational capabilities across both littoral and abyssal zones while accommodating diverse payload configurations (Usmanov and Chernychka, 2022). Equipped with advanced sensors and communication systems, UUVs can efficiently gather and process large volumes of data. This data not only supports decision-making and situational awareness but also enables the integration of manned and unmanned surface vessels. As a result, UUV deployment can significantly enhance law enforcement capabilities in marine and underwater environments allowing access to hazardous or hard-to-reach areas, gathering high-quality evidence, and providing detailed on-site reports (Zhantureyev et al., 2024).

2.4 Autonomous robots

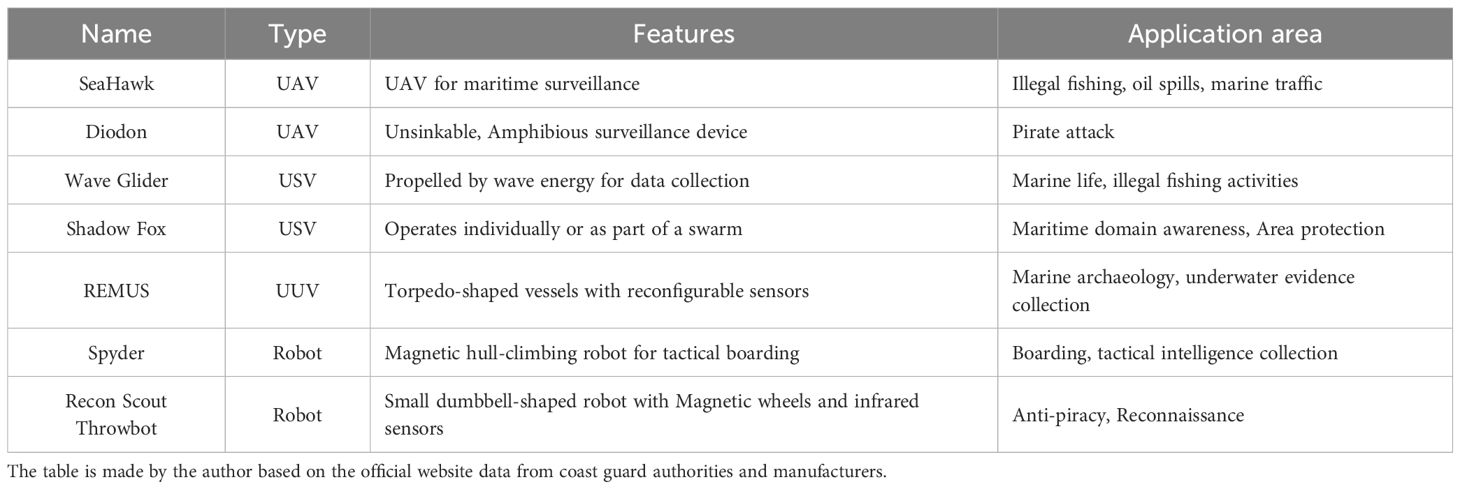

In addition to the unmanned systems developed based on traditional vehicles mentioned above, the applications of autonomous robots are expanding across diverse domains. These robots are typically used to perform dangerous, repetitive, or tedious tasks that were previously carried out by humans and have now evolved into powerful tools in numerous fields such as regional exploration and maritime monitoring (Martorell-Torres et al., 2024). In the maritime domain, autonomous robots are used in two primary configurations: the deployment of a single autonomous robot and the deployment of a robotic swarm. Single autonomous robots are employed for specialized tasks such as ship cleaning and maintenance, firefighting, anti-piracy operations, and ship inspections in scenarios too risky for human personnel. For example, the Spyder hull-climbing robot developed by HTX Raus CoE assists with tactical boarding and covert insertion, while throwable robots like the Recon Scout provide critical situational awareness in confined spaces during law enforcement operations (see Table 1).

As an emerging application in maritime law enforcement, the operational deployment of such robotic systems, while demonstrated by advanced coast guards like Singapore’s, remains less common than other UVSs. Their deployment is often constrained by challenges in endurance, communication reliability in complex metallic environments, and the development of robust autonomous behaviors for dynamic, unstructured settings. Consequently, their value is currently maximized in specific, high-risk scenarios requiring proximity or access to confined spaces. Furthermore, the deployment of autonomous robots for high-risk tasks such as ship inspections and tactical boarding introduces a new layer of complexity to international and domestic rules governing the use of force, due process during enforcement actions, and the admissibility of evidence collected by non-human agents in legal proceedings. To overcome the limitations of single platforms, a new robotic approach known as Multi-Robot Systems (MRS), has emerged, in which multiple autonomous robots work collaboratively (Zhou et al., 2022).3 Compared to single autonomous robots, MRS offer several advantages, including greater efficiency, reliability, flexibility, and scalability. These capabilities provide a more comprehensive set of tools for maritime law enforcement. For instance, within the MRS framework, existing research has explored collaboration among multiple homogeneous UUVs to address task allocation challenges and avoid underwater obstacles in unknown environments (Wu et al., 2022). Nevertheless, MRS still face practical limitations in communication, task allocation, and operational coordination, which require further optimization (Martorell-Torres et al., 2024).

Building upon the detailed examination of individual UVSs, including USVs, UAVs, UUVs, and Autonomous Robots, this section concludes with a comparative synthesis of their core operational attributes. To summarize and contrast the fundamental characteristics that dictate their operational utility, Table 2 provides a comprehensive analysis of key performance parameters, inherent capabilities, and limitations. This comparative framework serves to clarify the functional distinctions between UVS types and establishes a foundational reference for evaluating their respective suitability across the diverse scenarios encountered in maritime law enforcement operations.

3 Compatibility analysis of UVSs for maritime law enforcement

To consider the use of UVSs in maritime law enforcement is to examine the compatibility between the two. Maritime law enforcement is a broad term with somewhat undefined boundaries, but it is generally understood that nations share commonalities in certain enforcement missions and practices. These shared elements serve as a basis for exploring the compatibility between UVSs and maritime law enforcement.

3.1 Operational missions dimensions in maritime law enforcement

The statutory missions of maritime law enforcement agencies in different countries serve as a crucial basis for defining the scope of maritime law enforcement operations. An examination of the statutory missions4 of agencies such as the United States Coast Guard (USCG), the Chinese Coast Guard, and the Japan Coast Guard reveals that their primary responsibilities include but are not limited to the following: preserving national maritime sovereignty; suppressing crimes such as drug trafficking, smuggling, and illegal immigration; combating terrorism; ensuring marine safety; protecting the marine environment and resources; and countering piracy (Uyan et al., 2024).

3.1.1 Maritime sovereignty preservation

Maritime law enforcement agencies are key forces in safeguarding a country’s maritime territorial sovereignty. Their enforcement responsibilities span three dimensions: airspace, sea surface, and underwater. With intensifying global maritime competition, traditional maritime equipment faces increasing challenges in performing sovereignty protection tasks (Islam, 2024; Niazi, 2024). In particular, achieving comprehensive, blind-spot-free surveillance across vast national maritime jurisdictions remains a significant challenge. UVSs offer unique capabilities for conducting continuous maritime law enforcement operations under harsh sea conditions and adverse weather. Integrated systems comprising UAVs, USVs, and UUVs—leveraging their complementary strengths and cross-domain communication networks—form adaptable, responsive, and highly efficient mission architectures (Wibisono et al., 2023). This approach significantly reduces the human resource demands for maritime rights protection while enhancing surveillance capabilities through multi-sensor arrays. Deploying such systems in designated zones enables 24-hour patrol and monitoring of target waters, demonstrating a sovereign state’s “effective control” through persistent presence, and thereby reinforcing sovereignty or jurisdiction over the patrolled maritime areas.

3.1.2 Combat criminal activities

This is a typical mission of maritime law enforcement, involving activities such as drug trafficking, smuggling, and illegal immigration. Maritime law enforcement agencies typically intercept and seize smuggling vessels near coastlines to prevent the illegal entry of goods and individuals. Specific operations include deploying patrol vessels and aircraft to conduct continuous surveillance and investigation on the high seas, as well as dispatching special forces to board and intercept suspect vessels. In this context, UAVs, USVs, and autonomous robots serve as effective supplements—or even alternatives to traditional maritime law enforcement forces. For example, in 2010, the U.S. Navy reported that a Fire Scout UAV operating from the USS McInerney (FFG 8) achieved the first-ever drug bust conducted by an unmanned system (Kraska, 2010).

3.1.3 Anti-terrorism and anti-piracy

Such missions generally aim to prevent and deter terrorist acts against shipping, maritime facilities, and other maritime interests (Klein et al., 2020). Related operations include enhancing security at waterfront facilities, conducting maritime patrols and law enforcement boardings, ensuring maritime security, detecting weapons of mass destruction, and escorting vessels carrying hazardous goods or large numbers of passengers. These missions require robust intelligence support to identify high-risk vessels and potential threats and are inherently characterized by high-risk operational profiles. In anti-terrorism and anti-piracy missions, the deployment of UVSs can enhance intelligence-gathering capabilities and improve the success rate of detecting and intercepting potential terrorist activities and pirate attacks in their early stages. Additionally, the use of autonomous platforms for vessel boarding inspections significantly reduces the risks faced by human personnel during enforcement operations.

3.1.4 Marine environment and resource protection

Preventing and responding to unauthorized ocean dumping, oil and hazardous substance spills in the marine environment, and illegal fishing constitute critical components of maritime law enforcement for coastal states. To carry out these environmental stewardship missions, maritime law enforcement agencies typically employ aerial platforms for wide-area behavioral surveillance, complemented by vessel boardings, harbor patrols, fluid-transfer monitoring, and facility inspections (Thiesen, 2022). However, illicit actors increasingly adopt covert tactics to evade detection, such as concealed pollutant discharges, unauthorized seabed mining, and the destruction of islands and wetlands. These violations now often take the form of fragmented, small-scale operations rather than large-scale activities, which hinders authorities’ ability to obtain timely and accurate field intelligence (Jiang and Sun, 2024). In response, UUVs enable real-time photographic documentation of vessels suspected of engaging in illegal aquaculture or fishing, with imagery instantly relayed to command centers (Uyan et al., 2024). UUVs can also be integrated with satellite data and AI technologies to enhance the monitoring and suppression of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing (Zuzanna et al., 2022). By analyzing vessel trajectories and identifying suspicious behaviors, these systems facilitate the deployment of USVs for further inspection, thereby strengthening the enforcement of marine environmental protection laws and safeguarding marine ecosystems.

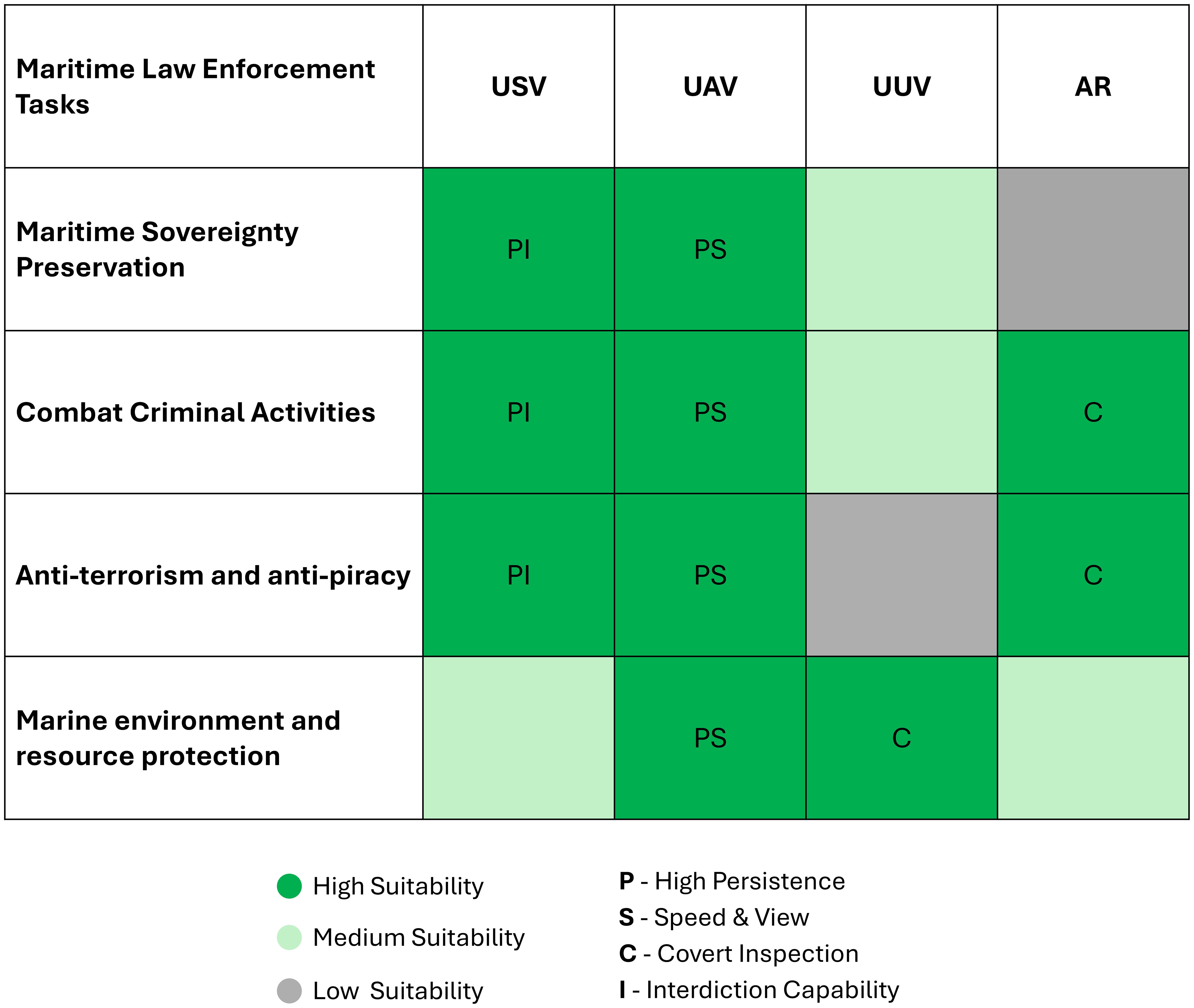

The comparative analysis of the four principal maritime law enforcement missions reveals the critical relationship between mission requirements and UVS capabilities. Figure 1 synthesizes these findings in a compatibility heatmap. The color gradient provides an immediate visual assessment of compatibility: dark green for high suitability (primary asset), medium orange for medium suitability (supportive or conditional roles), and light red for low suitability (ineffective or niche deployment). This matrix graphically illustrates how specific functional attributes, codenamed P (High Persistence), S (Speed and View), C (Covert Inspection), and I (Interdiction Capability), determine operational fit. This visual guide highlights the most relevant systems for each mission type, while also confirming that effective maritime law enforcement requires a portfolio-based approach which uses complementary system strengths rather than relying on any single asset, thereby framing the detailed discussion in the subsequent sections.

3.2 Measures dimensions in maritime law enforcement

The selection of maritime law enforcement measures directly impacts mission effectiveness across all the aforementioned domains. An analysis of enforcement practices in China and the United States reveals a range of regular operational measures, including patrols, escort surveillance, boarding inspections, monitoring, warnings, cessation orders (including departure mandates), tracking, interdiction, regulatory supervision, patrol-based surveillance, forensic imaging (video/photo), hailing, compliance checks, protective patrols, convoy security, interception, asset protection, and investigative actions (NAS, 2020; China Coast Guard, 2021). These measures can be categorized into discovery, evidence collection, and disposition measures based on mission objectives (Mao, 2020). UVSs not only align with these enforcement measures but also enhance their execution efficiency through technological integration and automation.

3.2.1 Reconnaissance measures

Reconnaissance measures typically involve either patrols by warships and military aircraft within national jurisdictional waters or the monitoring, tracking, and boarding inspections of maritime navigation and operations to detect illegal activities and infringements upon maritime rights. As inherently preventive actions, these measures aim to identify and intervene in unlawful acts at an early stage. Moreover, because patrols often target non-specific subjects, they also serve the important function of demonstrating sovereign rights. Compared to traditional surveillance methods, UVSs offer superior efficiency due to their multi-sensor arrays, which exceed human detection capabilities, and their real-time data communication systems. They are particularly well-suited for continuous maritime surveillance over vast sea areas.5 Characterized by lightweight structures, extended endurance, and stealth-enhanced propulsion systems, UVSs can covertly observe and identify illicit activities in nearby waters.

3.2.2 Evidence collection measures

These procedures involve photographic and audiovisual documentation of maritime violations and infringements during enforcement operations, serving as evidentiary material for legal proceedings or diplomatic claims. UAVs utilize their high-resolution cameras and sensors to collect on-site evidence of explicit illegal acts in the form of static photographs or dynamic videos. REMUS UUVs can operate continuously underwater, transmitting real-time evidentiary data to operators. These capabilities make them powerful tools for securing prosecutorial evidence and deterring underwater criminal activities. UASs equipped with sensors verify oil spills initially detected by coastal monitoring services and collect water and pollution samples for analysis and prosecution (EMSA, 2022). In some domestic cases, high-definition video provided by UVSs has eliminated the need for boarding, as violators are intercepted when fishing boats return to dock, with the videos serving as evidence (NAS, 2020).

3.2.3 Disposition measures

Disposition measures refer to the actions taken by maritime law enforcement agencies to safeguard national maritime rights. Upon detecting unlawful entry into jurisdictional waters, agencies assert jurisdiction through warnings and verbal commands. When illegal activities are confirmed or suspected, agencies implement mandated procedures, including cease-and-desist orders (with expulsion directives), on-site investigations, vessel interceptions, and compelled expulsions. To address the increasing demands of maritime enforcement missions amid limited personnel,6 UVSs now undertake high-intensity operations, enhancing human efficiency in target geolocation, pursuit and interception, and boarding assistance. For example, the USCG’s modified 7-meter interceptor boats from MetalCraft Marine have been converted into USVs using Spatial Integrated Systems’ platform, enabling fisheries enforcement and narcotics interdiction under extreme conditions (Biesecker, 2021). Successful deployment of these systems is expected to improve routine maritime law enforcement operations.

3.2.4 Protective measures

Protective measures primarily involve safeguarding maritime assets through patrols, escorts, and surveillance, providing security assurance for legitimate maritime activities. These measures aim to prevent maritime accidents, personnel casualties, and property losses. UVSs equipped with DRS RADA Technologies radar systems can track threats (including enemy unmanned systems) on the ocean’s surface or coordinate with friendly units. Furthermore, by leveraging an optimized consensus auction algorithm, when a USV formation is invaded by mobile intruders during an escort mission, the system can autonomously assign defenders to prevent attackers from approaching the vulnerable target (Du et al., 2021).

In conclusion, UVSs can adapt to diverse maritime law enforcement missions due to their unmanned nature and AI capabilities. The widespread application of UVSs will help improve the sustainability and accessibility of maritime law enforcement, thereby augmenting the force projection capabilities of national coast guard forces.

4 Challenges in deploying UVSs for maritime law enforcement

Despite their significant potential in maritime law enforcement, UVSs face multidimensional challenges. These include legal uncertainties within existing regulatory frameworks and inherent security vulnerabilities, particularly the risk of exploitation by non-state actors, which could further destabilize the overall maritime security architecture.

4.1 Risks of legal uncertainty

As mentioned above, UVSs have demonstrated established technological viability for maritime law enforcement applications. In principle, UVSs should be permitted for all statutorily authorized maritime law enforcement tasks that can be performed by manned assets. However, the legal regimes governing some unmanned operations are still emerging and unsettled, which can create legal uncertainties (NAS, 2020). The core challenge stems from a fundamental mismatch between the novel operational paradigms of UVSs and the traditional, human-centric framework of international maritime law. Although maritime law enforcement agencies possess extensive statutory authority to execute their missions, and more countries are incorporating UVSs within their enforcement powers, continued technological advancements and expanding applications may outpace existing legal frameworks. For example, the emergence of USVs and UUVs has raised fundamental legal questions regarding current vessel regulations. Their autonomous operation without human crews challenges the conventional notion of a ship governed by human authority. A primary legal quandary is whether USVs and UUVs qualify as vessels under maritime law and whether they are eligible for applicable navigation rights and immunities. This ambiguity was notably illustrated by the 2016 Bowditch UUV incident in the South China Sea, which highlighted the potential for international disputes arising from unclear legal status. Key maritime conventions, including the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (COLREGS), UNCLOS, and various domestic inland navigation rules, were drafted decades before unmanned navigation became feasible. Thus, provisions concerning watchkeeping, lookout duties, crew requirements, and boarding inspections all presuppose the presence of humans onboard, leaving ambiguity regarding the legal status of remote operators and programmers of USVs. For instance, COLREGS Rule 5 explicitly requires every vessel to maintain a proper lookout by sight and hearing, a requirement that is difficult to interpret and directly apply to sensor systems and algorithms operating without human intervention. Moreover, UNCLOS does not explicitly address the complex issues surrounding the legal status and sovereign immunity of marine UVSs, leaving numerous unresolved questions (Ruhal, 2024).

Aside from platforms with low autonomy that are still operated by humans, USVs have encountered challenges in adapting to existing ship management regulations during operations (Allen, 2018). In the realm of commercial unmanned ships, the IMO is working on defining the regulatory framework for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships MASS. The Comité Maritime International (CMI) has also conducted a legal status survey of MASS across maritime law associations in over 20 countries. These efforts aim to assess the applicability of MASS under various conventions and national laws, guiding the development of the future MASS Code (IMO, 2025b).

Overall, the challenges presented by UVSs in maritime law enforcement under international law primarily concern their legal status, sovereign immunity, right of approach, right of hot pursuit, and right of visit. The lack of clarity surrounding these issues creates tangible operational risks, potentially leading to hesitancy in deployment or dangerous encounters at sea, and may deter the development of consistent state practice. Hence, maritime enforcement agencies need to determine whether existing laws, regulations, and policies allow for the safe and efficient application of UVSs in all law enforcement missions. If not, they must establish supplementary authorities and procedures to address regulatory gaps and, where appropriate, develop new legal and policy frameworks for USVs, UAVs, and UUVs to eliminate risks arising from legal ambiguities.

4.2 Emerging security risks

Although advancements in digital and intelligent technologies have increased operational efficiency in maritime law enforcement, they may also expose UVSs to security vulnerabilities from cyber and other peripheral attacks, including risks of hacker intrusions and data leakage, which in turn endanger the safety of navigation systems and maritime missions (Islam, 2024). These vulnerabilities originate from the deeply intertwined nature of the Operational Technology (OT) and Information Technology (IT) systems of UVSs are more intertwined, resulting in a larger attack surface compared to traditional vehicles (Yousaf et al., 2024). Specifically, the operating architecture of UVSs involves gathering real-time data from sensors such as the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), Automatic Identification System (AIS), and cameras, then transmitting analyzed judgments to navigation or control systems for vehicle operation. In this process, if anomalies occur in any data segment, cascading failures may ensue, while sophisticated cyberattacks particularly target these vulnerabilities in vessel systems and AI technologies (Yoo and Jo, 2023). For example, GNSS spoofing or jamming attacks can deceive a USV about its location, potentially leading it into restricted waters or causing collisions, while data interception can compromise sensitive law enforcement intelligence. To this end, the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) has listed nine high-level threat categories for autonomous ships. These include attacks to disrupt RF signals, attacks to deceive or degrade sensors, attacks to intercept or modify communications, attacks on Operational Technology systems, attacks on Information Technology systems, attacks on AI used for autonomous operations, attacks through supply chains, attacks through physical access and attacks on the shore control center (Cho et al., 2022).

Since maritime law enforcement agencies undertake numerous sensitive missions—such as enforcing the laws of coastal states and safeguarding national marine safety—they must remain vigilant against evolving security threats. In this context, the primary challenge for maritime law enforcement agencies is striking a balance between the benefits of utilizing UVSs and the imperative of maintaining robust cybersecurity measures. A uniquely modern threat stems from the artificial intelligence governing autonomous functions, where adversaries could employ data poisoning attacks during the training phase of AI models, corrupting their decision-making algorithms and creating novel security risks (Walter et al., 2025). Maritime law enforcement missions exhibit significant disparities in information requirements and cybersecurity demands, with mission types directly dictating the requisite cybersecurity levels. The cybersecurity requirements for missions such as routine patrols and marine environment and resource protection are generally lower than those for missions related to national defense, security, and sovereignty. Hence, delivering cost-effective cybersecurity tailored to UVS mission profiles is a pressing concern for maritime law enforcement agencies. Despite efforts by defense departments of some countries and the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) to protect information systems against cyberattacks,7 maritime law enforcement agencies still need to assess the consequences of cyberattacks and identify viable remedies, encompassing operational guidelines and relevant personnel training.

5 Recommendations

5.1 Establishing maritime law enforcement capabilities and risk evaluation framework for UVSs

UVSs, with their agile and versatile capabilities, offer significant potential across various maritime law enforcement domains. However, maritime law enforcement agencies should holistically evaluate multiple integrated factors in their decision-making process when utilizing UVSs. These factors include platform capabilities, mission alignment, statutory authorization boundaries, application risks, data management, regulatory compliance requirements, cost-benefit efficiency metrics, and policy developments. Such considerations are essential when determining deployment timing, locations, and scope—including system quantities and operational coverage. In the face of increasingly complex maritime environments and diverse enforcement requirements, establishing a multidimensional evaluation framework for UVS deployment is essential. This framework clarifies the relationship between the evolving capabilities of UVSs and specific enforcement missions, while also identifying potential safety and legal risks associated with their use. It enables maritime law enforcement agencies to judiciously balance the deployment of manned and unmanned systems, thereby guiding strategic priorities for UVS application in maritime law enforcement.

The evaluation framework is architecturally structured as a mission-centric, three-dimensional matrix that integrates UVS capability attributes and application risk parameters (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dimensions of maritime law enforcement capabilities and risk assessment for UVSs. The figure is made by the author based on the domestic coast guard regulations of China, the United States, and Japan.

(1) Mission Dimension – Grounded in the statutory mandates of national maritime law enforcement agencies, this dimension allows for content calibration based on practitioners’ operational experience.

(2) Capability Dimension – This dimension assesses all UVS types based on both general capabilities and specialized functions, which are critical determinants of operational viability in maritime law enforcement. General capabilities include tracking/surveillance, search, and patrol (ensuring persistent presence), which are broadly applicable. Specialized capabilities encompass sampling, non-kinetic disabling functions, directional electromagnetic pulses, and submersible tracking, factors that directly influence deployment suitability.

(3) Risk Dimension – This includes potential legal and security risks inherent in deploying UVSs for maritime law enforcement. Legal risks primarily involve compliance assessments of unmanned platforms such as USVs and UAVs, evaluating their adherence to relevant international conventions, domestic laws, and sovereign immunity provisions. Security risks mainly pertain to cybersecurity vulnerabilities and threats to data integrity originating from external actors.

The proposed evaluation framework provides maritime law enforcement agencies with a multidimensional tool to assess the operational viability of various UVSs across different mission types. Given the variation in national maritime law enforcement requirements, this framework helps align UVS applications with practical operations, supporting the development of compliant and effective deployment strategies. Notably, several countries have already initiated evaluations of UVS applications across diverse mission scenarios, reporting measurable efficiency gains in existing case studies (Khairi et al., 2020; Chelvan, 2025).

5.2 Addressing the regulatory lacunae through domestic legislation

As substantiated earlier, existing international law fails to directly address the core legal quandaries surrounding UVSs. In particular, it remains unclear whether USVs and UUVs qualify as vessels under maritime law and whether they are eligible for applicable navigation rights and immunities. Confronted with the systemic challenges posed by UVSs to conventions such as UNCLOS, the prevailing scholarly consensus advocates resolving future disputes primarily through treaty interpretation, convention revision, or the development of state practice within the current international legal framework (Boviatsis and Vlachos, 2022; Liu, 2024; Xing and Zhu, 2021). Given that UVSs are still relatively new in the maritime domain, their legal status should be determined by international law, the laws of the flag state or registration state, and customary international law of the sea, as reflected in instruments issued by relevant international organizations (e.g., IMO) (Kraska and Pedrozo, 2022). However, there are currently no signs that the United Nations is taking steps to address the challenges posed by UVSs to UNCLOS, and the IMO’s international legislation on MASS remains in development. In this context, domestic legislation emerges as a primary and pragmatic avenue for initiating regulatory development and generating state practice. At present, addressing these legal challenges through domestic law proves more efficient, and such state practice may also contribute to the evolution of international maritime law. According to Articles 90 and 91 of UNCLOS, each State has the authority to establish the criteria for granting nationality to ships, including rules for their registration and flagging. In other words, UNCLOS entrusts individual states with the responsibility of determining whether a structure can be recognized as a ship, provided it complies with the standards outlined in Article 94 (Ruhal, 2024).

In refining the enforcement rules for UVSs through domestic legislation, updating maritime laws should be the primary legislative avenue. First, comprehensive national marine governance statutes should explicitly define the legal status, operational authority, and liability framework of UVSs. For example, Article 78–2 of the China Coast Guard Law innovatively included submersibles within the definition of “vessels,” without requiring them to be crewed operations (China Coast Guard, 2021), thereby establishing a legal basis for classifying UUVs as vessels.

Second, based on these superior domestic laws, maritime law enforcement agencies can formulate specific enforcement rules and policy guidelines for each type of UVS. This ensures operational legality and compliance and determines whether exemptions or equivalent treatment may apply under mandatory regulations. The procedures for the formulation, revision, and implementation of such rules should also be considered. For instance, in 2024, the maritime safety administrations in Zhejiang and Tianjin (China) issued notices authorizing the use of UAVs for maritime law enforcement within their jurisdictions and outlined the scope and operational guidelines for drone-based enforcement (Tianjin, 2024; Zhejiang, 2024). These rules can serve as “subordinate laws” (e.g., executive regulations or administrative rules) to address evolving issues in the “public law” domain related to UVSs and national maritime security. This focus on a specific national case is not intended to be prescriptive but to provide a foundational model that other states can adapt, critique, and build upon based on their own legal traditions and operational contexts. Future research should systematically compare such emerging institutional approaches across states as more regulatory frameworks develop.

Third, the UVS industry plays a crucial role in advancing regulatory frameworks. The UVS industry, particularly classification societies and technology developers, is an active contributor to its development. World leading classification societies, such as the Det Norske Veritas (DNV), China Classification Society (CCS), ClassNK, Lloyd’s Register (LR), American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) and Bureau Veritas (BV), have recently adopted policies to promote the development of intelligent ships. For instance, the CCS introduced “the Rules for Intelligent Ships 2025” (China Classification Society, 2025b), while the DNV established the DNV Class Guideline (CG-0264) and AROS Class Notation (DNV, 2025). A significant aspect of classification societies’ involvement is their unique role as Recognized Organizations. When formally authorized by a national marine administration, these societies can act on behalf of the state to conduct statutory certifications (IMO, 2025a). This dual capacity allows them to seamlessly integrate cutting-edge technical standards (developed as class societies) with the enforcement of statutory legal requirements (fulfilled as Recognized Organizations). Consequently, the unmanned ships industry possesses an unparalleled capability to bridge the gap between technological innovation and regulatory compliance. Therefore, developing a comprehensive regulatory framework for maritime law enforcement involving unmanned ships should be a collaborative effort between classification societies and maritime law enforcement agencies. This includes standardizing guidelines for domestic unmanned vessel development and coordinating these with the administrative regulations governing law enforcement oversight issued by maritime authorities. Such an integrated approach ensures that the technical specifications for unmanned platforms are harmonized with the operational, legal, and accountability requirements inherent to maritime law enforcement operations. By engaging with the classification societies that have dual roles, regulators can facilitate the establishment of a cohesive and pragmatic regulatory system that effectively supports the deployment of unmanned platforms in complex maritime law enforcement operations.

5.3 Optimizing security risk mitigation strategies for UVSs in maritime law enforcement

Due to their characteristics of remoteness and autonomy, the security assurance of UVSs in maritime law enforcement primarily depends on cybersecurity resilience across the following critical domains: unmanned vehicles (including their sensors), data transmission networks, and AI components.

Under a whole lifecycle management approach, cybersecurity risk mitigation begins with assessment, namely, a security-by-design strategy. The findings from the risk evaluation presented in the initial section of this chapter inform the design phase of UVSs. This process involves forecasting potential cyberattack scenarios during various mission executions in order to predefine cybersecurity requirements and standards, ensuring compliance with safety protocols from the development stage onward. For this reason, organizations such as the IMO and IACS have progressively issued cybersecurity guidelines and standards for maritime systems, with multiple countries subsequently enacting complementary regulatory frameworks.8 In 2024, CCS released the “Guidelines for Ship Cyber Security 2024,” expanding upon its existing framework for ship network infrastructure (China Classification Society, 2025a). In early 2025, the USCG issued the final rule on maritime security and cybersecurity standards—titled the “Maritime Transportation System Cybersecurity Rule”—which establishes minimum cybersecurity requirements for vessels. This final rule includes mandates to develop and maintain a Cybersecurity Plan, designate a Cybersecurity Officer, and implement various strategies to ensure ongoing cybersecurity (United States Coast Guard, 2025). The regulatory frameworks mentioned above serve as a foundational cornerstone for securing unmanned surface vessels and other maritime assets against cyber threats.

During the development phase of UVSs for maritime law enforcement, two critical aspects require prioritization:

Firstly, ensuring cyberattack-resilient physical systems that can continue operating in a degraded but still acceptable mode.9 Currently, most UVSs used in maritime law enforcement are sourced from third-party vendors—either turnkey solution providers (e.g., Diodon in France, DJI in China) or specialized supply chain contributors (e.g., autonomy subsystem developers and patrol vessel integrators). To strengthen system integrity, it is essential not only to mandate compliance with cybersecurity certifications but also to implement diversified sourcing strategies for critical components. This approach ensures operational continuity if individual components are compromised or provide corrupted data, as illustrated by the U.S. ban on foreign-manufactured drones due to cybersecurity concerns (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2020). Therefore, when incorporating externally developed UVSs, maritime law enforcement agencies must rigorously evaluate the cybersecurity posture of the entire supply chain. This includes assessing the supply chain’s source based on mission-specific usage expectations, the availability of cybersecurity solutions, cost, and long-term operational stability. A comprehensive evaluation of mission profiles, security capabilities, cost structures, and supply reliability is key to ensuring cyber resilience from the outset.

Secondly, addressing cybersecurity risks arising from autonomy. AI is a core enabler of accurate decision-making and autonomous functionality in UVSs, but it also introduces novel vulnerabilities. To mitigate threats such as “data poisoning” and spoofing attacks that target AI models during training, it is essential to ensure the integrity of training data and use only trusted data sources and validated models—thereby minimizing the attack surface (Walter et al., 2025). Additionally, the development of explainable AI (XAI) models is critical for enabling developers to identify model weaknesses, detect and eliminate poisoned data, and implement targeted countermeasures to reduce cybersecurity risks.

During the operational phase, to address evolving cybersecurity threats and meet the demanding security requirements of maritime law enforcement missions, the following countermeasures can be adopted:

(1) Establish an external cyberattack detection and response mechanism tailored to marine UVSs. This mechanism should include conventional measures—such as port restriction policies, encrypted communications, and firewall deployment—as well as advanced autonomous system defense strategies. Innovative techniques like Defense Fusion Cyber Resilience (DFCR), which integrates multiple sensors, data fusion processes, and defensive modules, can be used to safeguard AI systems aboard autonomous vessels (Walter et al., 2025). Furthermore, considering the high-security demands of maritime enforcement operations, adopting a Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) is advisable. Operating under the principle of “never trust, always verify” (Leister, 2024), ZTA requires all entities—whether operators, onboard sensors, or external data sources—to undergo stringent identity verification and continuous authentication (Leister, 2024).

(2) Implement personnel training programs. Personnel training is a critical strategy for reducing cyber vulnerabilities (United States Coast Guard, 2025). Operators of UVSs must acquire new technical skills and cybersecurity awareness to manage systems effectively and defend against potential threats. Therefore, specialized training programs are essential, equipping personnel not only with operational competence but also with the ability to recognize both conventional and AI-specific cyberattacks. Immersive technologies such as Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) can be integrated into training programs to enhance the understanding of complex cybersecurity concepts and scenarios (Dewan et al., 2023).

6 Conclusion

Maritime law enforcement agencies have both compelling reasons and growing opportunities to advance the use of UVSs more aggressively. It is imperative for these agencies worldwide to adopt a comprehensive approach to evaluate and harness the capabilities of existing and emerging unmanned systems. The primary novelty of this article lies in the construction of an original evaluative framework that positions itself as a necessary tool for bridging the gap between technical compliance and operational legality in the law enforcement domain. As illustrated in Figure 3, the evaluative framework proposed in this article is positioned within the upper-right quadrant of the analytical spectrum, a position that reflects its dedicated focus on mission-effectiveness within sovereign law enforcement operations. This strategic positioning distinguishes it from key related frameworks in the following aspects: On the one hand, it is intensely mission-oriented and evaluates the deployment of UVSs based on operational performance across various maritime law enforcement scenarios. This stands in contrast to the standards such as the IMO MASS Code and classification society rules located in the lower-left quadrant, which prioritize general operation safety over task-specific applications within civil and commercial domains. On the other hand, this framework is fundamentally concerned with law enforcement and legal authority, ensuring compliance within complex international and domestic legal regimes. Unlike military application frameworks, which adhere to a decision-making logic purely aimed at maximizing mission effectiveness, one of the core objectives of this framework is “to accomplish law enforcement missions lawfully”—representing a pursuit of effectiveness under strict legal constraints. Furthermore, regional cooperation frameworks, which essentially constitute a set of policy and procedural coordination mechanisms, do not provide specific guidance on operational actions as this framework does, thus positioning them further toward the left side of the chart. Consequently, this framework does not seek to replace foundational technical standards and general rules, such as the IMO MASS Code, but is explicitly built upon them. The framework addresses a critical higher-order question: “Given a platform certified as compliant with all pertinent technical safety standards, how should maritime law enforcement agencies employ it to execute missions in a manner that is both effective and lawful?” By translating technical compliance into operational legitimacy and effectiveness, the framework fills an identified gap, providing a dedicated decision-support tool for the specialized domain of maritime law enforcement. Doing so will enable maritime law enforcement agencies to remain responsive and relevant across a wide range of maritime law enforcement missions. While the current rules of international law do not inherently preclude the use of various types of UVSs in such missions, there is a pressing need to accelerate the development of corresponding state practices to ensure legal stability and operational predictability within the maritime law enforcement domain. By establishing a clear domestic framework for UVS deployment, this article lays the necessary groundwork for their future integration into international cooperative efforts aimed at combating transboundary maritime threats.

Figure 3. Positioning of key frameworks for maritime UVSs in law enforcement and beyond. Source: Author’s compilation.

In maritime law enforcement operations involving UVSs, human oversight remains essential at the current stage, particularly given the limited capacity of machines for subjective reasoning in complex decision-making processes. However, the ongoing advancement of AI technologies raises the possibility of highly autonomous systems operating without human intervention in the future. This prospect necessitates further examination of safety risks and the development of accountability mechanisms for human-machine collaboration.

Author contributions

WW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. HY: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Science Research by the Ministry of Education (China), Grant No. 24YJC820049.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

UVSs, unmanned vehicle systems; UAVs, unmanned aerial vehicles; USVs, unmanned surface vehicles; UUVs, unmanned underwater vehicles; AI, artificial intelligence; UNCLOS, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea; MASS, Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships; MRS, Multi-Robot Systems; USCG, United States Coast Guard; COLREGS, Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea; IACS, International Association of Classification Societies; CCS, China Classification Society.

Footnotes

- ^ Currently, there is no universally accepted term for Unmanned Maritime Vehicles (UMVs). The IMO Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) employs the designation “Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship (MASS),” defining it as “a ship which, to varying degrees, can operate independently of human interaction.” Naval forces, conversely, tend to use “Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs)” to refer to military unmanned vessels.

- ^ For instance, the Shadow Fox, designed by L3Harris, is an USV capable of operating individually or as part of a swarm.

- ^ Such robot clusters, deployed in swarms and designed based on the principle of “division of labor and complementary advantages,” are also termed Heterogeneous Robotic Swarms.

- ^ Related information draws from the USCG website at https://www.gocoastguard.com/about-the-coast-guard/discover-our-roles-missions, the China Coast Guard website at https://www.ccg.gov.cn/zcfg/202405/t20240515_180.html, the Japan Coast Guard website at https://www.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/mission/.

- ^ For example, the United States Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) comprises approximately 3.40 million square nautical miles of maritime space, exceeding the combined land area of all fifty states. See Exclusive Economic Zone, at https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/exclusive-economic-zone-eez.

- ^ In 2024, the China Coast Guard (CCG) effectively handled 19.7 thousand public reports and investigated 5,668 cases. See China Coast Guard Holds Special Interview on Maritime Law Enforcement (in Chinese), at https://www.ccg.gov.cn/xwfbh/202501/t20250126_2605.html.

- ^ For example, the U.S. Department of Defense has been focusing on achieving cyberattack resilient physical systems. Concurrently, the IACS published two unified requirements (UR E26 and E27) on cyber resilience in 2022, marking the first integration of cybersecurity into global shipbuilding regulations. Furthermore, in 2017, the 98th session of the IMO Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) formally adopted the Guidelines on Maritime Cyber Risk Management (MSC-FAL.1/Circ.3) and the Resolution Maritime Cyber Risk Management in Safety Management Systems (MSC.428(98)).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cyberattack resilience is the ability to detect when an attack is occurring and reconfiguring the system to permit continued operation.

References

Allen C. H. (2018). Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: formalism vs functionalism. J. Mar. L. Com. 49, 477–514. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3244172

Argüello G. (2023). “Smart port state enforcement through UAVs: new horizons for the prevention of ship source marine pollution,” in Smart ports and robotic systems (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 207–226. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-25296-9_11

Ayala A., Portela L., Buarque F., Fernandes B. J. T., and Cruz F. (2024). UAV control in autonomous object-goal navigation: a systematic literature review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 125. doi: 10.1007/s10462-024-10758-7

Bae I. and Hong J. (2023). Survey on the developments of unmanned marine vehicles: Intelligence and cooperation. Sensors 23, 4643. doi: 10.3390/s23104643

Barrera C., Padron Armas I., Luis F., Llinas O., and Marichal N. (2021). Trends and challenges in unmanned surface vehicles (USV): from survey to shipping. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navigation Saf. Sea Transportation 15, 135–142. doi: 10.12716/1001.15.01.13

Biesecker C. (2021). Saildrone set to launch new USV it believes will meet maritime domain awareness needs. Available online at: https://www.defensedaily.com/saildrone-set-to-launch-new-usv-it-believes-will-meet-maritime-domain-awareness-needs/advanced-transformational-technology/ (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Bloise N., Primatesta S., Antonini R., Fici G. P., Gaspardone M., Guglieri G., et al. (2019). “A survey of unmanned aircraft system technologies to enable safe operations in urban areas,” in 2019 international conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS). 433–442 (Atlanta, GA, USA: IEEE). doi: 10.1109/ICUAS.2019.8797859

Bolbot V., Sandru A., Saarniniemi T., Puolakka O., Kujala P., and Valdez Banda O. A. (2023). Small unmanned surface vessels—a review and critical analysis of relations to safety and safety assurance of larger autonomous ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 2387. doi: 10.3390/jmse11122387

Boviatsis M. and Vlachos G. (2022). Sustainable operation of unmanned ships under current international maritime law. Sustainability 14, 7369. doi: 10.3390/su14127369

Chang Y.-C., Zhang C., and Wang N. (2020). The international legal status of the unmanned maritime vehicles. Mar. Policy 113, 103830. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103830

Chelvan V. P. (2025). Use of drones to detect, respond to chemical spills at sea to be trialed from Q2 2025. Available online at: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/transport/use-of-drones-to-detect-respond-to-chemical-spills-at-sea-to-be-trialled-in-q2-2025 (Accessed June 14, 2025).

Cheng A. (2025). Check out how PCG’s waterproof drone and hull-climbing robot keep Singapore’s territorial waters safe and secure. Available online at: https://www.police.gov.sg/Media-Room/Police-Life/2025/01/PCGs-Tech-Arsenal-Next-Gen-Maritime-Security (Accessed May 20, 2025).

China Classification Society (2025a). Guidelines for ship cyber security 2024. Available online at: https://www.ccs.org.cn/ccswzen/articleDetail?id=202409240925796916 (Accessed June 14, 2025).

China Classification Society (2025b). Rules for intelligent ships 2025. Available online at: https://www.ccs.org.cn/ccswzen/specialDetail?id=202503310327204112 (Accessed June 14, 2025).

China Coast Guard (2021). Coast guard law of the PRC. Available online at: https://www.ccg.gov.cn/zcfg/202405/t20240515_180.html (Accessed May 29, 2025).

Cho S., Orye E., Visky G., and Prates V. (2022). Cybersecurity considerations in autonomous ships. Available online at: https://ccdcoe.org/uploads/2022/09/Cybersecurity_Considerations_in_Autonomous_Ships.pdf (Accessed June 19, 2025).

Coito J. (2021). Maritime autonomous surface ships: New possibilities—and challenges—in ocean law and policy. Int. Law Stud. 97, 259.

de Andrade E. M., Sales J. S. Jr., and Fernandes A. C. (2025). Operative unmanned surface vessels (USVs): A review of market-ready solutions. Automation 6, 17. doi: 10.3390/automation6020017

Dewan M. H., Godina R., Chowdhury M. R. K., Noor C. W. M., Wan Nik W. M. N., and Man M. (2023). Immersive and non-immersive simulators for the education and training in maritime domain—A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 147. doi: 10.3390/jmse11010147

DNV (2025). Autonomous and remotely-operated ships. Available online at: https://www.dnv.com/maritime/autonomous-remotely-operated-ships/ (Accessed June 14, 2025).

Du B., Lu Y., Cheng X., Zhang W., and Zou X. (2021). The object-oriented dynamic task assignment for unmanned surface vessels. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 106, 104476. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2021.104476

Durmuş A. N. (2023). “The intersection between law and technology in maritime law,” in The regulation of automated and autonomous transport (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 107–166. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-32356-0_5

EMSA (2022). RPAS service portfolio: multipurpose maritime surveillance. Available online at: https://www.emsa.europa.eu/opr-documents/opr-manual-a-guidelines/item/3332-rpas-service-portfolio-multipurpose-maritime-surveillance.html (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Fantinato M. (2021). “Governance of international sea borders: regional approaches and sustainable solutions for maritime surveillance in the mediterranean sea,” in Sustainability in the maritime domain (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 169–195. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-69325-1_9

Grand-Clément S. and Bajon T. (2022). Uncrewed maritime systems: A primer (Geneva: UNIDIR). doi: 10.37559/caap/22/erc/13

Heo J., Kim J., and Kwon Y. (2017a). Analysis of design directions for unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). J. Comput. Commun. 5, 92–100. doi: 10.4236/jcc.2017.57010

Heo J., Kim J., and Kwon Y. (2017b). Technology development of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs). J. Comput. Commun. 5, 28. doi: 10.4236/jcc.2017.57003

IMO (2018). IMO takes first steps to address autonomous ships. Available online at: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/08-MSC-99-MASS-scoping.aspx (Accessed June 14, 2025).

IMO (2025a). Recognized organizations. Available online at: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/iiis/pages/recognized-organizations.aspx (Accessed August 25, 2025).

IMO (2025b). Reports on acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships Annual Report-2024. Available online at: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Security/Documents/MSC.4-Circ.269_Annual%202024.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2025).

Islam M. S. (2024). Maritime security in a technological era: addressing challenges in balancing technology and ethics. Mersin Univ. J. Maritime Faculty 6, 1–16. doi: 10.47512/meujmaf.1418239

Jiang X. and Sun X. (2024). The Dilemma and Countermeasures of Maritime Administrative Law Enforcement of China Coast Guard:Take the first public interest lawsuit on marine ecology of China Coast Guard as an example. Ocean Dev. Manage. 41, 71–79. doi: 10.20016/j.cnki.hykfygl.2024.02.004

Khairi A., Ismail S. B., and Suhaimi A. (2020). Effectiveness of autonomous landing system for unmanned aerial vehicles: A case study at Malaysian maritime enforcement agency. Mar. Frontier 11, 8–14.

Klein N. (2019). Maritime autonomous vehicles within the international law framework to enhance maritime security. Int. Law Stud. 95, 8.

Klein N., Guilfoyle D., Karim M. S., and McLaughlin R. (2020). Maritime autonomous vehicles: New frontiers in the law of the sea. Int. Comp. Law Q. 69, 719–734. doi: 10.1017/s0020589320000226

Kraska J. and Pedrozo R. (2022). Disruptive technology and the law of naval warfare (New York: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/oso/9780197630181.001.0001

Laghari A. A., Jumani A. K., Laghari R. A., and Nawaz H. (2023). Unmanned aerial vehicles: A review. Cogn. Robotics 3, 8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cogr.2022.12.004

Leister J. (2024). The U.S. Navy’s cybersecurity program office (PMW 130) leads the charge in implementing zero trust architecture in unmanned systems. Available online at: https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/display-news/Article/4001119/the-us-navys-cybersecurity-program-office-pmw-130-leads-the-charge-in-implement/ (Accessed June 22, 2025).

Liu D. (2024). On the international legal regulation of unmanned marine systems and China’s response (in chinese). Oriental Law, 69–80. doi: 10.19404/j.cnki.dffx.2024.01.004

Liu C. and Feng Y. (2025). Navigating uncharted waters: Legal challenges and the future of unmanned underwater vehicles in maritime military cyber operations. Mar. Policy 171, 106430. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106430

Liu Z., Zhang Q., Xiang X., Yang S., Huang Y., and Zhu Y. (2025). Intelligent decision and planning for unmanned surface vehicle: A review of machine learning techniques. Ocean Eng. 327, 120968. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.120968

Liu Z., Zhang Y., Yu X., and Yuan C. (2016). Unmanned surface vehicles: An overview of developments and challenges. Annu. Rev. Control 41, 71–93. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2016.04.018

Lv Z., Wang X., Wang G., Xing X., Lv C., and Yu F. (2025). Unmanned surface vessels in marine surveillance and management: advances in communication, navigation, control, and data-driven research. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 13, 969. doi: 10.3390/jmse13050969

Mao C. (2020). The definition and future prospect of maritime “rights protection and law enforcement” (in Chinese). J. Dalian Maritime Univ. 19, 72–80.

Martorell-Torres A., Guerrero-Sastre J., and Oliver-Codina G. (2024). Coordination of marine multi robot systems with communication constraints. Appl. Ocean Res. 142, 103848. doi: 10.1016/j.apor.2023.103848

McLaughlin R. and Klein N. (2021). Maritime autonomous vehicles and drug trafficking by sea: Some legal issues. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 36, 389–418. doi: 10.1163/15718085-bja10061

Miętkiewicz R. (2018). Unmanned surface vehicles in maritime critical infrastructure protection applications — LNG terminal in świnoujście. Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Marynarki Wojennej 213, 43–51. doi: 10.2478/sjpna-2018-0012

NAS (2020). Leveraging unmanned systems for coast guard missions (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press). doi: 10.17226/25987

Niazi Z. A. (2024). Future of maritime security: navigating complex waters in the indo-pacific. J. Indo-Pacific Affairs 7, 112–139.

Patterson R. G., Lawson E., Udyawer V., Brassington G. B., Groom R. A., and Campbell H. A. (2022). Uncrewed surface vessel technological diffusion depends on cross-sectoral investment in open-ocean archetypes: A systematic review of USV applications and drivers. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.736984

Piazzolla D., Bonamano S., Penna M., Resnati A., Scanu S., Madonia N., et al. (2025). Combining USV ROV and multimetric indices to assess benthic habitat quality in coastal areas. Sci. Rep. 15, 24282. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-09845-8

Ruhal S. (2024). The evolving seascape of naval warfare: unmanned underwater vehicles and the challenges for international law. J. Conflict Secur. Law 29, 349–374. doi: 10.1093/jcsl/krae011

Shao Y., Yu Y., and Ma Y. (2024). The challenge of safe and sustainable development of the unmanned ship: seeking for effective legal responses. Front. Mar. Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1385082

Thiesen W. H. (2022). The Long Blue Line: the Coast Guard’s environmental protection mission. Available online at: https://www.history.uscg.mil/Research/THE-LONG-BLUE-LINE/Article/2939085/the-long-blue-line-the-coast-guards-environmental-protection-mission/ (Accessed May 29, 2025).

Tianjin M. S. A. (2024). Notice on initiating the use of unmanned aerial vehicles for maritime law enforcement. Available online at: https://tj.msa.gov.cn/content/content.html?id=7190600322350321664 (Accessed June 14, 2025).

United States Coast Guard (2023). Research and development on unmanned surface vehicles. Available online at: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/23_0711_uscg_research_and_development_on_unmanned_surface_vehicles.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2025).

United States Coast Guard (2025). Cybersecurity in the marine transportation system. Available online at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/17/2025-00708/cybersecurity-in-the-marine-transportation-system (Accessed June 14, 2025).

U.S. Department of the Interior (2020). Temporary cessation of non-emergency unmanned aircraft systems fleet operations. Available online at: https://www.doi.gov/document-library/secretary-order/so-3379-temporary-cessation-non-emergency-unmanned-aircraft (Accessed June 14, 2025).

Usmanov I. and Chernychka M. (2022). Maritime autonomous weapon systems from the standpoint of international humanitarian law. Lex Portus 8, 33. doi: 10.26886/2524-101x.8.2.2022.2

US Navy (2007). The navy unmanned surface vehicle (USV) master plan. Available online at: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA504867 (Accessed June 22, 2025).

Uyan K., Yılmaz F., and Sönmez U. (2024). A research on the opportunities of autonomous unmanned marine vehicles to enhance maritime safety and security. J. Transportation Logistics 9, 234–244. doi: 10.26650/jtl.2024.1393580

Walter M., Vineetha Harish A., Christison L., and Tam K. (2025). Visualisation of cyber vulnerabilities in maritime human-autonomy teaming technology. WMU J. Maritime Affairs 24, 5–31. doi: 10.1007/s13437-025-00362-z

Wang J., Zhou K., Xing W., Li H., and Yang Z. (2023). Applications, evolutions, and challenges of drones in maritime transport. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 2056. doi: 10.3390/jmse11112056

Welch H., Clavelle T., White T. D., Cimino M. A., Van Osdel J., Hochberg T., et al. (2022). Hot spots of unseen fishing vessels. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq2109. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abq2109

Wibisono A., Piran M. J., Song H.-K., and Lee B. M. (2023). A survey on unmanned underwater vehicles: Challenges, enabling technologies, and future research directions. Sensors 23, 7321. doi: 10.3390/s23177321