Processing, microstructure, properties, and applications of MoSi2-containing composites: a review

- 1Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN Unidad Saltillo, Ramos Arizpe, Mexico

- 2Corporación Mexicana de Investigación en Materiales S.A. de C.V, Saltillo, Mexico

Intermetallic molybdenum disilicide (MoSi2) possesses unique physical, chemical, thermal, and mechanical properties that make it compatible with some ceramics (SiC, Al2O3) and metals (Cu, Al) to manufacture composite materials. Its current applications, chiefly limited to heating elements, can be expanded if its properties are judiciously combined with those of other materials like SiC or Al to produce ceramic- and metal-matrix composites with improved mechanical, thermal, functional, or even multifunctional properties. This review presents a perspective on the feasibility of manufacturing ceramic- and metallic-based MoSi2 composite materials. A comprehensive discussion of the pros and cons of current liquid-state and solid-state processing routes for MoSi2 metal-matrix composites and the resulting typical microstructures is presented. Although MoSi2 has been studied for more than five decades, it was not until recently that industrial applications demanding high temperature and corrosion resistance started utilizing MoSi2 as a bulk material and a coating. Furthermore, beyond its traditional use due to its thermal properties, the most recent applications include it as a contact material in microelectronic components or circuits and optoelectronics. The short-term global growth predicted for the MoSi2 heating elements market is expected to significantly impact possible new applications, considering its potential for reuse and recyclability. A prospective assessment of the application of recycled MoSi2 to composite materials is presented.

1 Introduction

Intermetallic MoSi2 is a moderate-density (6.23 g/cm3) material that has been widely used to manufacture high-temperature heating elements due to its thermal properties. It is a material, that is, chemically stable, which makes it ideal to be applied in the development of composite materials with a ceramic or metallic matrix, either as a reinforcement/thermal/functional phase or as a matrix phase. In addition, MoSi2-based composites can be manufactured through different processing routes, either by solid-state or liquid-state methods (Pech-Canul and Makhlouf, 2000; Bhattacharya et al., 2002; Houan et al., 2004; Köbel et al., 2004; Cemal et al., 2012; Khanra et al., 2012; Venkateswaran et al., 2015; Gousia et al., 2016; Contreras-Cuevas et al., 2018). The utilized processing methods include powder metallurgy, spontaneous infiltration, mechanicalalloying, thermal spray, and pressure infiltration, amongst others.

Around the 1980s, the properties of intermetallic MoSi2 were studied, and it proved to be an excellent material to be applied in metal matrix composites (MMC) (Schlichting, 1978; Fitzer and Remmele, 1985). However, it was not until the mid-1990s that research on MoSi2-based composites began, emphasizing the mechanical, physical, and thermal properties of the material. But, the subject of the potential applications of a MoSi2-based composite has not been dealt with in-depth, whether in components for electronic packaging, heat sinks, components for aircraft engines, etc. High-temperature heating elements are the most requested application to date. Another issue that has not received the corresponding attention has to do with the recycling and reuse of components that are manufactured with MoSi2 to be used as raw material in the development of composite materials.

It is expected that the market for molybdenum disilicide (MoSi2) heating elements will grow significantly by 2025 with marketplace segmentation by players (Kanthal, I Squared R, Zircar, and MHI, amongst others), by types (1700°C, 1800°C, and 1900°C grades), and by end-users (Laboratory and Industrial furnaces). The confluence of these factors, together with the pinpoint spotting of the consumption market by regions (North America, Europe, Asia Pacific, Latin America, Middle East, and Africa), suggests the economic influence of this crucial intermetallic material (Global Molybdenum Disilicide, 2021).

This review provides constructive criticism of the state of the art of intermetallic MoSi2 to produce composite materials, comparing its properties with those of other materials that can be combined, the different production methods, and applications.

2 Intermetallic MoSi2: crystal structure, properties, and applications

Molybdenum disilicide (MoSi2) is an intermetallic material of moderate density (6.23 g/cm3) that has generated interest in various industrial fields due to its physical, mechanical, and thermal properties (Yao et al., 1999). Due to its high melting point (2030°C), its main use is for high-temperature applications such as resistors or heating elements, and as it is resistant to corrosion, it is an ideal material for corrosive environments. When subjected to high temperatures, it forms a passive layer of silicon dioxide (SiO2), which protects it from oxidation (Cook et al., 1992). In the electrical industry, the use of MoSi2-based composite materials has generated special interest, since this intermetallic alone has a low thermal expansion coefficient in the range of 20°C–1400°C (CTE = 7–10 × 10−6 K−1) (Petrovic, 1992), a good thermal conductivity at 25°C (κ = 66.2 W/m K) (Kulczyk-Malecka et al., 2016), and a good Young’s modulus (E = 440 GPa) (Nakamura et al., 1990).

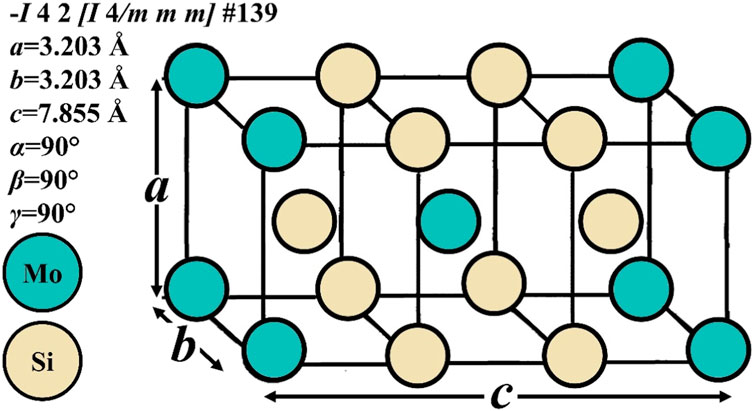

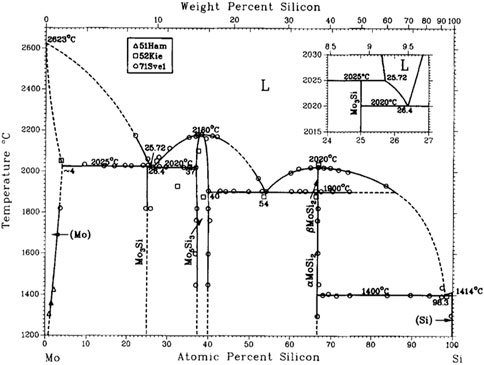

Intermetallic MoSi2 has two polymorphic phases: the alpha and the beta modifications. The alpha phase, the most stable polymorph up to 1900°C, has a body-centered tetragonal structure (C11b-type) (Figure 1) and belongs to the space group No. 139, I 4/m2/m2/m (I4/mmm, Patterson symmetry) (Hahn, 2005), tI6 in Pearson notation. Its lattice parameters are a = b = 3.203 Å and c = 7.855 Å (Lide, 2005; Cardarelli, 2008; Villars and Cenzual, 2012). According to Waghmare et al. (1998), the characteristics of MoSi2 in its alpha form may favor an improvement in mechanical properties. According to Gokhale and Abbaschian (1991), MoSi2 undergoes a polymorphic transformation from a low-temperature tetragonal form (α-MoSi2) to a high-temperature hexagonal form (β-MoSi2) at 1900°C, which corresponds to the Mo-Si equilibrium phase diagram (Figure 2) (Gokhale and Abbaschian, 1991). The beta phase has a hexagonal structure (C40-type) and belongs to the space group No. 180, P6222 (P6/mmm, Patterson symmetry) (Hahn, 2005); its lattice parameters are a = 4.60 Å and c = 6.55 Å (Zamani et al., 2012).

FIGURE 1. Tetragonal crystal structure and lattice parameters of MoSi2 (Petrovic, 1992; Yao et al., 1999).

FIGURE 2. Mo-Si phase diagram (Gokhale and Abbaschian, 1991).

It is a material soluble only in nitric acid (HNO3) and hydrofluoric acid (HF) (Cardarelli, 2008). The most common ways of preparing MoSi2 and MoSi2-based composites are by sintering and plasma spraying (Yao et al., 1999), the latter being used to form dense pieces. The densification of materials aims to produce a material that can be easily handled and to increase its mechanical and physical properties.

According to Yao et al. (1999), with the plasma spray process, it is possible to achieve near-net shape composites and consolidate the material in a single operation, and under a rapid solidification process, fine-grained and chemically homogeneous microstructures are achieved. According to Koch (1998), solid-state processing routes, such as mechanical alloying and powder metallurgy, offer benefits such as relatively simple processes and the flexibility they offer when manufacturing MMCs. Due to the chemical reaction with silicon to form silicides, MoSi2 has limited applicability for hardening ductile phases with metallic phases, and using ceramic phases such as SiC or ZrO2 as reinforcing phases has a modest effect on improving and increasing plastic flow and toughness (Ito et al., 1996).

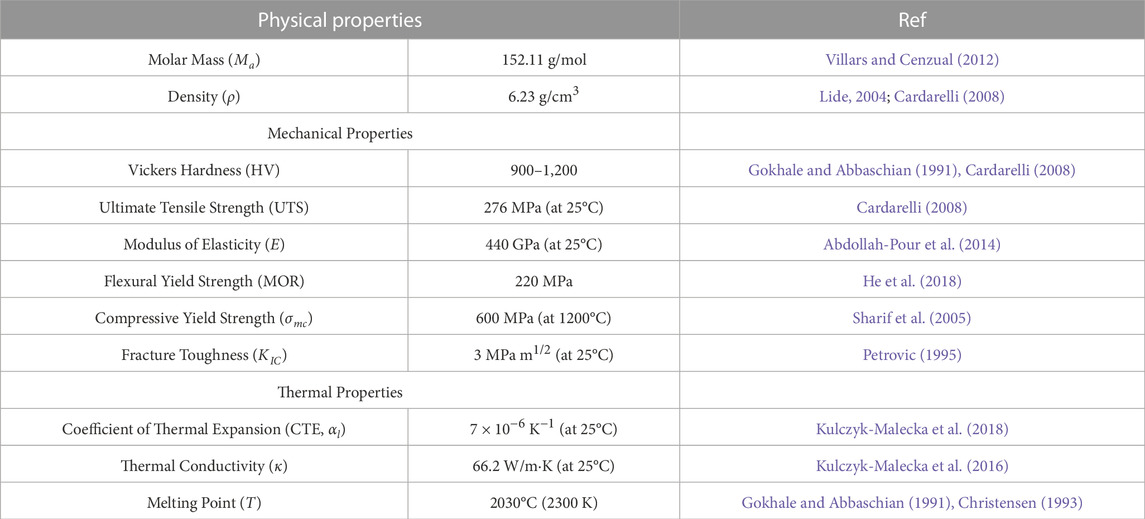

The properties of MoSi2 were described for the first time in 1949 by Maxwell (1945), who argued that this material had desirable high-temperature properties such as oxidation resistance, good high-temperature fracture strength, and good thermal conductivity and ductility at high temperatures (1315°C). However, MoSi2 has some drawbacks, such as susceptibility to harmful oxidation at low temperatures (400°C–600°C) (Chou and Nieh, 1993a), high creep rate above 1200°C (Yao et al., 1999), and oxygen diffusion at the grain boundaries at high temperatures (T > 900°C) (Chou and Nieh, 1993b). At 1600°C, its yield strength at 0.2% displacement is approximately 20 MPa (Sharif et al., 2001). Since it is brittle below 900°C, with low fracture toughness (2–4 MPa m1/2) (Yao et al., 1999), its high-temperature structural applications are limited. Consequently, it is more attractive for the design of composites for low- and moderate-temperature applications. Table 1 shows the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of MoSi2.

However, using ceramic and refractory reinforcements in MoSi2 composites has improved the mechanical properties and conferred better resistance to high temperatures. Some studies used MoSi2 as a reinforcing phase in ceramic-matrix composites for high-temperature applications, as in the work of Grohsmeyer et al. (2019). They investigated the densification behavior and resulting microstructures of hot-pressed ZrB2-MoSi2 composites using different ZrB2 particle sizes (3–12 um) and MoSi2 contents (5–70 vol%). It has been found that MoSi2 is a beneficial phase for the densification of ZrB2 at 1750°C due to the formation of a transient liquid phase (Silvestroni et al., 2018). According to Sciti et al. (2006a) in UHTC (ultra-high temperature ceramics) ZrB2-MoSi2 composites, the microstructural analysis indicates that at least 20% vol. MoSi2 is needed to obtain a dense material. In addition, at temperatures above 1200°C, the oxidation of MoSi2 forms a silica layer that seals the composite’s surface, thus preventing ZrB2 degradation (Sciti et al., 2005; Sciti et al., 2006b).

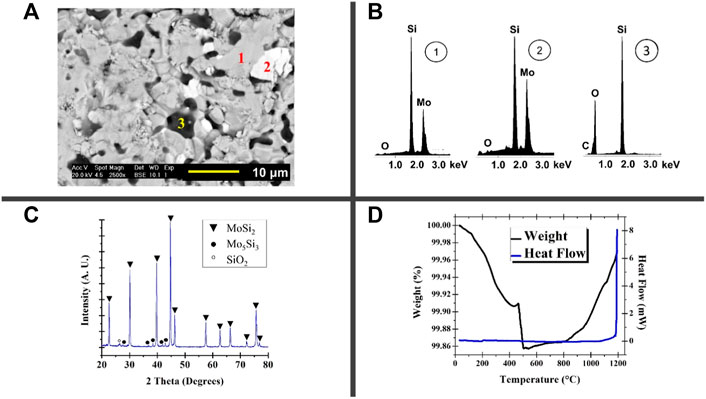

As illustrated in the micrograph of Figure 3A, the typical microstructure of a MoSi2 monolith features a grey color phase corresponding to the MoSi2 matrix. The dark phases are SiO2 and the white areas belong to the Mo5Si3 phase due to a silicon deficiency or a reaction with oxygen (Shan et al., 2002). EDS analysis (Figure 3B) shows the elements present in the microstructure phases. The diffractogram made by XRD analysis (Figure 3C) shows the phases present, with the MoSi2 phase with the highest intensity peaks, compared to the Mo5Si3 and SiO2 phases with the low-intensity peaks. The DSC-TG diagram (Figure 3D) shows that MoSi2 is stable at temperatures of 1200°C and with weight losses down to 0.14%.

FIGURE 3. (A) SEM image by backscattered electrons, (B) diffractograms of point EDS analysis of the phases present, (C) XRD diffractogram, and (D) DSC-TG analysis diagram of a recycled MoSi2 heating element section (Kanthal® Super 1800).

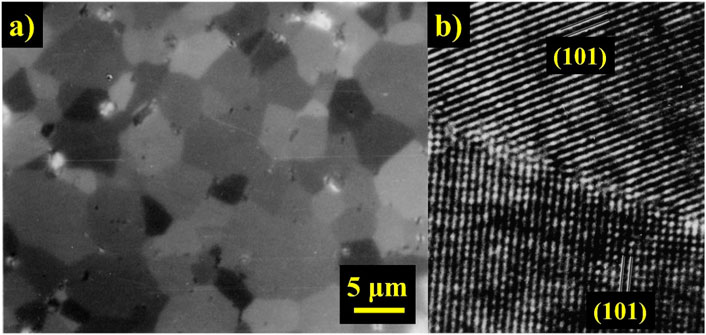

Mitra et al. (2003) studied the behavior of MoSi2 at elevated temperatures (1000°C–1350°C). One of the samples fabricated for the study was made by the reaction-hot-pressed (RHP) process. For this purpose, Mo (3 μm) and Si (20 μm) powders were mixed and degassed under vacuum at 800°C for 4 h. Subsequently, the samples were hot pressed (1500°C) under vacuum conditions (1024 Pa), using 26 MPa pressure. Figure 4A shows the microstructure of the RHP MoSi2 sample, and according to the authors, the average grain size obtained using the linear intercept method was 5 μm. The HRTEM image (Figure 4B) shows a grain boundary of RHP MoSi2, which deformed at 1,200°C, with a strain rate of 10–3 s–1.

FIGURE 4. (A) Polarized-light optical micrographs of reaction-hot-pressed (RHP) MoSi2 and (B) HRTEM image of a typical grain boundary in RHP MoSi2 after testing at 1200°C with a strain rate of 10–3 s–1 (Mitra et al., 2003).

Intermetallic MoSi2 has been used as a reinforcing material and in the matrix phase in composites. In aluminum matrix composites (AMC), as a reinforcement, MoSi2 has improved the material’s wear and corrosion resistance compared to a monolithic matrix material (Gousia et al., 2016). Recently, MoSi2 has been considered a strong candidate as a contact material in microelectronic components or circuits where it is necessary to increase the conductivity and signal speed (Wetzig and Schneider, 2006). Also, due to its thermal properties, it is an ideal material for applications in components subjected to high temperatures, such as heating elements in electric furnaces or combustion chamber components.

Since the early 1990s, studies have been conducted on developing and processing (Maloney and Hecht, 1992) and determining the physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of MoSi2-containing composites (Xiao et al., 1991; Xiao and Abbaschian, 1992; Pill Lee et al., 2012). More recently, intense research has been done exploring different applications, such as vehicle components for satellite launches, of MoSi2 and MoSi2-based composites rather than their thermal uses (Khanra et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2022a). Remarkably, in 2022, researchers from Bangladesh (Liton et al., 2022) reported a breakthrough in the optoelectronic properties of α-MoSi2 and concluded with an analysis of optical parameters (parts of dielectric constants, absorption coefficient, reflectivity, etc.) that α-MoSi2 may be suitable for applications in QLED (Quantum Light Emitting Diode) and OLED (Organic Light Emitting Diode) devices, as well as potential absorbers to hinder solar heating by UV radiation.

2.1 Oxidation of MoSi2

Because intermetallic MoSi2 has excellent resistance to oxidation in dry or humid air, and in oxygen or strongly oxidizing environments when reaching temperatures higher than 600°C (Ito et al., 1996), its oxidation resistance becomes of particular interest in studies of MoSi2-based composites. However, heavy oxidation of MoSi2 has been observed because of the slow growth of the protective layer of amorphous SiO2, in addition to the fracture of an initial protective layer of Mo9O26-SiO2 (Meschter, 1990). Due to this oxidation resistance, MoSi2 is an ideal candidate as a protective coating on materials that do not support highly oxidizing environments. The presence of oxygen impurities that exceed 2 at % in the MoSi2-silicon interface causes the formation of metal-rich silicide phases; the coexistence of these phases is predictable using a Mo-Si-O ternary phase diagram (Wakita et al., 1984). It is worth noting that at 1300°C, SiO2 undergoes a phase transformation from tridymite to cristobalite. This modification in the oxide causes a greater formation of SiO2 and evaporation of MoO3 (Melsheimer et al., 1997).

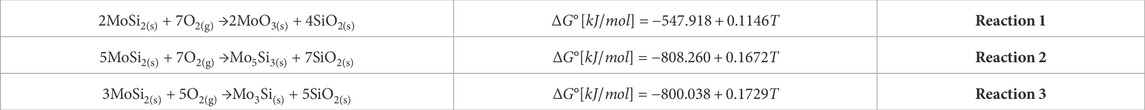

SiO2 is formed when MoSi2 encounters oxygen (Reaction 1) (Wakita et al., 1984; Meschter, 1990; Melsheimer et al., 1997). There are two possible oxidation reactions (Reactions 2 and 3) and both are thermodynamically feasible (Gamutan and Miki, 2022).

However, the reaction where MoO3 is present is favored since it results from oxygen saturation between 400°C and 600°C (Yao et al., 1999). At high temperatures (1,050°C–1,470°C), SiO2 undergoes a crystal structure transformation from tridymite (orthorhombic) to cristobalite (tetragonal) and these silica polymorphs have lower densities (Nakae et al., 1998). The formation of the SiO2 layer is crucial since it is the reason for oxidation resistance in corrosive environments, and the faster its formation, the greater the oxidation resistance, which is an advantage for those materials (metals, ceramics, MMC or CMC) protected with MoSi2 layers or MoSi2 composite layers (Pech-Canul et al., 2000a; Mortensen, 2000; Zumdick et al., 2001; Rodríguez-Reyes et al., 2003). However, in the manufacture of composites by liquid state routes, forming this silica layer can make it challenging to incorporate the liquid metal into the porous body to be infiltrated since ceramics have poor wettability on their surface (Nakae et al., 1998; Pech-Canul et al., 2000a; Mortensen, 2000; Rodríguez-Reyes et al., 2003; Tapia-López, 2018).

In investigations of the last two decades, MoSi2 and MoSi2 composites have been used as protective layers to protect ceramic matrix composite (CMC) materials that will be exposed to high temperatures (Ibano et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2022b; Ren et al., 2022) and corrosive environments, especially in highly oxidizing environments that can embrittle the material (Xu et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2006; Fu et al., 2009; Sooby Wood et al., 2016; Bezzi et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2020). Most researchers seek for the materials to be protected to not only not rust easily but also have high thermal shock resistance and that a dense protective SiO2 layer forms at high temperatures to prevent oxidation for as long as possible (Yan et al., 2009; Zhao, 2010; Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2022).

3 MoSi2-based composites

MoSi2-based composites have used different types of reinforcement, ranging from fine particles (Khanra et al., 2012), continuous fibers (Bhatti and Shatwell, 1997), and whiskers (Gac and Petrovic, 1985; Sun and Pan, 2001). Continuous fiber reinforcements have been used, such as ceramic fibers (SiC, Al2O3) and high-resistance ductile fibers (tungsten and molybdenum alloys), achieving composite creep strength values of 70–100 MPa at 1100°C, high-temperature resistance (T > 1400 C), and a fracture toughness value of 37.5 kJ/m2 (Maloney and Hecht, 1992). However, SiC whiskers used as reinforcement have shown better properties at high temperatures and oxidation resistance due to the formation of a silica layer (Carter et al., 1989).

In 1978, MoSi2 became a matrix material for composites and ceramics or refractories as reinforcement material (Schlichting, 1978). Since the mid-1980s, other types of materials have been used to reinforce MoSi2 composites, improving their properties even at room temperature (Yao et al., 1999). Such is the case of the niobium wire reinforcements with which the mechanical properties were improved at room temperature (Fitzer and Remmele, 1985). Niobium is a ductile material, making it suitable for MoSi2 matrix composites due to its high melting temperature and a CTE close to that of the matrix. This makes fewer cracks in the matrix under a thermal cycle (Alman et al., 1992; Gibala et al., 1992; Xiao and Abbaschian, 1992; Shaw and Abbaschian, 1993). Silicon carbide whiskers (SiCw) improved fracture toughness and strength at room temperature (Gac and Petrovic, 1985). Using 0.1 μm diameter SiCw as a reinforcing material within the composite showed that the levels of mechanical properties were within the range of high-temperature engineering applications (Carter et al., 1988). The carbon present in the SiC helps to reduce the appearance of oxides in the MoSi2, in addition to avoiding the formation of the siliceous phase at the grain boundaries, especially in samples processed by hot pressing (Yao et al., 1999). Furthermore, according to Carter et al. (1989) the MoSi2 matrix should not react with SiC from the thermodynamics viewpoint. However, as it has a ceramic reinforcement, such as SiC, the composite can show fragile behavior at room temperature due to the lack of independent, active sliding systems.

In some cases, MoSi2 is used as a reinforcing material in metal matrix composites (MMC). Such is the case of aluminum matrix composites (AMC), which are materials with good mechanical properties and that have structural, functional, or high-tech applications, as is in the aerospace, automotive, defense, and electronic packaging industries, to name a few (Gousia et al., 2016). The most common reinforcements in an AMC are those with ceramic phases such as Al2O3, SiC, and AlN. However, intermetallic reinforcements have become relevant and offer properties with functional applications (Surappa and Rohatgi, 1981; Mortensen and Jin, 1992; Surappa, 2003; Kainer, 2006a).

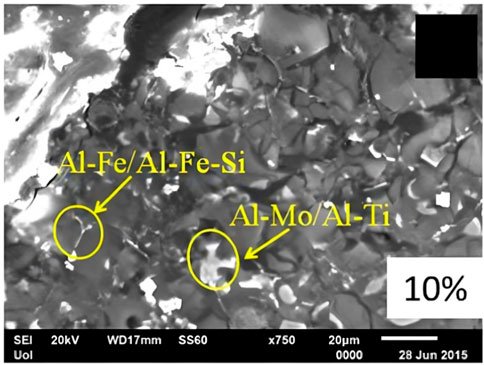

In the work by Gousia et al. (2016), an AMC was prepared with an Al 1050 matrix and the addition of MoSi2 powder with a particle size of 100–300 nm at approximately 1–10 μm. The reaction between the Al 1050 alloy and 10% of the intermetallic MoSi2 led to intermetallic phases such as Al12Mo, Al5Mo, Al4Mo, and Al3Ti. It was also observed in the micrographs (Figure 5), the Al-Fe-Si phase, which increased the hardness of the material, and the Al-Mo-Ti intermetallic phase, showing a benefit in sliding wear and erosion behavior.

FIGURE 5. SEM micrograph of the produced composite of Al/10%MoSi2 (Gousia et al., 2016).

Some challenges faced during the heat treatment of MoSi2-containing composites are the formation of undesirable phases or excessive oxidation of MoSi2 that may deteriorate the composites’ integrity and properties. Accordingly, some authors have focused on process temperature, residence time, and atmosphere as critical heat treatment parameters (Zeng et al., 2002; Zamani et al., 2012; Niu et al., 2013; Abdollah-Pour et al., 2014).

3.1 Processing routes for MoSi2-based composites

The production of metal matrix composites (MMC) can be done using different processing techniques (Figure 6), ranging from the solid-state technique, the liquid-state technique, the metallurgical powder (PD) technique, the physical vapor processing (PVD) technique, and direct processing/spray deposition technique, (Adeosun et al., 2014; Contreras-Cuevas et al., 2018). Instead, in recent years, only the simplest and most specialized techniques, such as mechanical alloying and the infiltration process, have been used because they are viable, low-cost processes and have the possibility of making irregular shapes. These pieces, in the end, can have a net shape or a near-net shape (Zweben, 1992; Contreras-Cuevas et al., 2018).

According to work by Lee et al. (2019), the conventional manufacturing processes used to prepare aluminum matrix composites (AMCs) can become complex and highly specialized processes that require specific skills and unique equipment, becoming expensive and limited in their application. Therefore, the authors outline a more straightforward route to AMC manufacturing, which involves mixing Al powder and ceramic reinforcement.

However, the most straightforward methodologies to produce MMC and AMC have had better results in terms of mechanical and thermal properties, especially for hybrid composites that require these properties for their final application (Adams and Miller, 1975; Premkumar et al., 1992; Surappa, 2003; Adeosun et al., 2014). In this review, the authors discuss the methodologies that have presented favorable results in producing composites with MoSi2, either as a reinforcement material or as a matrix phase.

3.1.1 Solid state processing methods

The solid-state process is suitable for reactive systems, in addition to having some advantages over liquid-state processes such as minimal segregation and reaction between the reinforcement and the matrix (Contreras-Cuevas et al., 2018). The goal of using these solid-state processes is to achieve higher mechanical properties in MMCs, but this makes them relatively expensive processes.

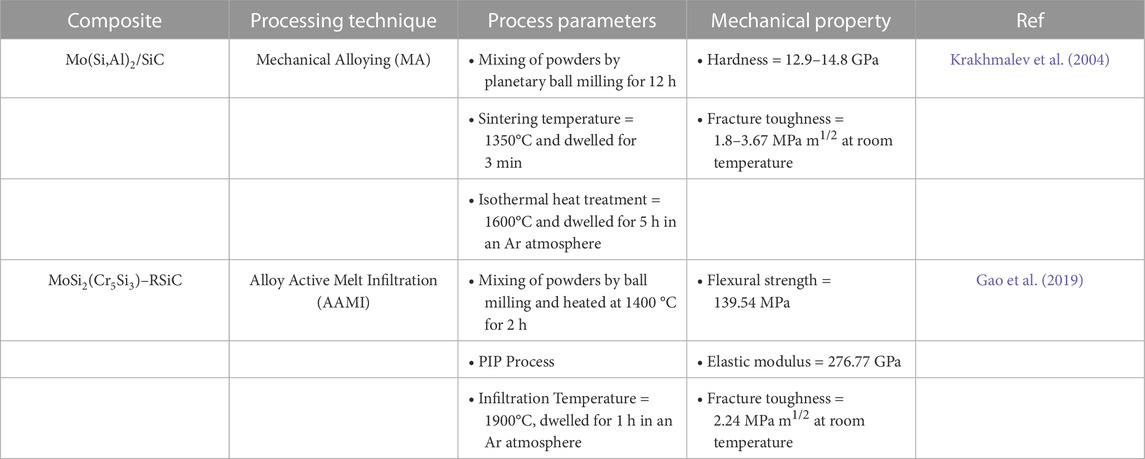

Krakhmalev et al. (2004) developed a composite consisting of MoSi2 as the matrix and an aluminum alloy, using three different reinforcements: Al2O3, SiC, and ZrO2. The composites were prepared using the spark plasma sintering method (SPS) of powders produced by mechanical alloying (MA), annealing the specimens at 1600°C for 5 h. It was explained that MA allows for achieving a fine-grained intermetallic alloyed powder and that, together with SPS, the MoSi2-based composites can be effectively sintered with fine microstructure. The SPS of MA powders method proved effective for forming an ultra-fine structure of microns or submicrons of Mo(Si,Al)2, containing retained phases of Mo and/or Mo5Si3.

The powders for the MoSi2 composite were prepared by mixing elemental powders with a ceramic phase in a planetary ball mill in an argon atmosphere for 12 h. The elemental powders (99.99% purity) were mixed with a second phase (average particle size ≤1 μm) in a high-energy ball mill. For the SPS of the MA powders, the samples were compacted and then sintered at 1350°C for 3 min. Subsequently, the samples were isothermally treated in an argon atmosphere at 1600 C for 5 h.

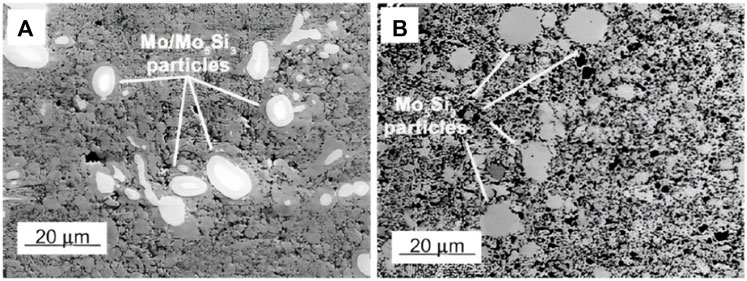

The results showed that in the sample of Mo0.63Si0.27Al0.10 (wt%)/20 vol% SiC, an ultrafine structure of Mo(Si,Al)2 and retained phases of Mo and/or Mo5Si3 were observed after sintering of the composite. In the sample heat-treated by annealing (T = 1600 C for 5 h), a coarsening of the C40 Mo(Si0.75Al0.25)2 matrix and the ceramic phase (SiC) was observed as well as the transformation of the solid solution of retained Mo (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. The microstructures (backscattering electrons images) of the Mo(Si0.75Al0.25)2/20 vol% SiC matrix composites in the as-sintered (A) and annealed (B) states. The white phases in bright inclusions in (A) are Mo solid solution cores and the bright inclusions in (B) are Mo5Si3 (Krakhmalev et al., 2004) (With permission).

Krakhmalev et al. (2004) conclude that the composites show higher thermal stability with certain annealing conditions and that the fracture toughness depends on the quantity and nature of the second phase. Furthermore, it was found that microstructure refinement combined with a composite structure improves fracture toughness by 20%–30%. However, this would be an insufficient improvement for industrial applications with C40 Mo(Si0.75Al0.25)2 matrix, as the negative effect of matrix coarsening on hardness and fracture toughness due to the annealing treatment of the samples has been demonstrated.

In the work by X. Yi, W. Xiong, and J. Li (Yi et al., 2007), a Cu-MoSi2 composite was manufactured using the powder metallurgy process to develop an advanced thermal material with high thermal conductivity and a low coefficient of thermal expansion. According to the authors, this material can be applied in heat sinks, electrical packaging of semiconductors, or high-power electronic devices. The choice of intermetallic MoSi2 over other more common reinforcing materials, such as SiC or Al2O3, is because MoSi2 has excellent oxidation resistance and good thermal and electrical conductivity, which makes it an ideal candidate to be used as a thermal or functional phase in the composite.

Electrolytically precipitated pure Cu powders (>99.5%, 40 μm) and high purity MoSi2 ultrafine powders (1.8–2.3 μm) were used as raw materials. Each composite material was processed through a high-energy ball mill for 10 h and a rotation speed of 300 rpm. The MoSi2 and Cu powders were placed into a marble container and mixed in a planetary ball mill. Subsequently, the bar shape samples (40 mm × 80 mm × 10 mm) were cold pressed at a compaction pressure of 200 MPa. To increase the green strength, they were compacted at room temperature under cold isostatic pressure (CIP) at 60 MPa. Once the compaction process was completed, the samples were sintered at 950°C in an atmosphere of H2. Finally, each sample was subjected to three passes of hot rolling, having a maximum deformation of 55%, and then annealed in an atmosphere of H2 gas at 950°C for 2 h.

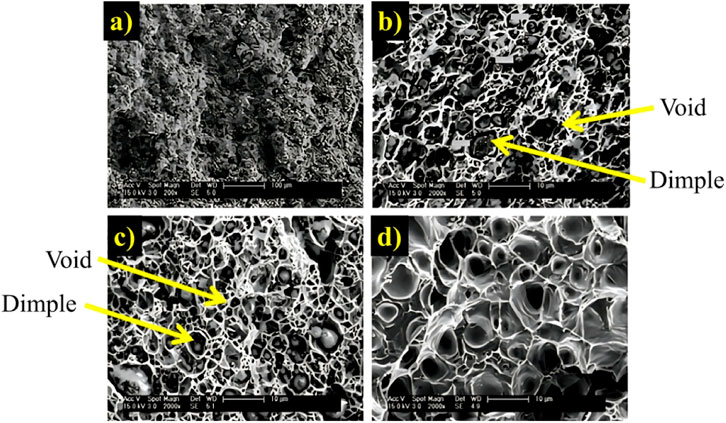

Scanning electron microscopy results showed the uniform distribution of MoSi2 particles. In the micrographs of the fracture surface (Figure 8), the voids present at the interfaces during plastic deformation are observed, where the bond strength between MoSi2 and the matrix is weak. As the deformation continues, the voids agglomerate into larger holes, resulting in the final fracture. These agglomerated voids dimple the surface of the fracture.

FIGURE 8. SEM images of the tensile fracture surface of the composites: (A) Overall morphology (Cu-2%MoSi2); (B), (C) dimples and voids in Cu-2% and −8%MoSi2 samples respectively; (D) high magnification of the pure Cu sample (control sample) (Yi et al., 2007) (With permission).

Regarding the composite’s thermal properties, the results showed that the samples with the highest thermal conductivity were the pure copper control sample and the Cu-2% MoSi2 composite. As the MoSi2 content increased, the thermal conductivity decreased considerably, attributed to the constant increase in the electron scattering in the crystal structure. According to Yi et al. (2007), the CTE value of pure copper at 100°C is 9.7 × 10−6/°C. However, in Cu/MoSi2 composites, the composites tested at 100°C showed good thermal conductivity, lower thermal expansion coefficient, and better tensile stress, ascribed to the Orowan reinforcement mechanism. The sample with the lowest CTE value was Cu-2% MoSi2 (3.4 × 10−6/°C), while the Cu-6% MoSi2 and pure Cu samples had the highest CTE values with 9 × 10−6/°C and 9.7 × 10−6/°C, respectively. This result is ascribed to an uneven distribution of secondary phases and 10% porosity on average in the samples. On a macroscopic scale, the existence of pores prevents the composites from expanding. It was concluded that the Cu-MoSi2 composites show good thermal conductivity and a low CTE (Yi et al., 2007) and it was proposed to improve the purity and density of the materials used so that they can be applied as heat sinks in electronic packaging systems. Although Cu/MoSi2 composites are promising prospects for the aerospace, electrical, and electronic industries, research works are very limited or scarce, particularly regarding microstructure characterization, such as identifying secondary phases formed during synthesis (Yi et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2008).

3.1.2 Liquid state processing methods

The liquid-state processes are one of the most used fabrication routes to produce composites at an industrial level because they are low-cost and allow cost-effective final products. These products have good properties compared to those fabricated in solid-state, so they are strong candidates to be applied in different industrial sectors (Bezzi et al., 2019). The advantage of using the liquid-state processes is that there is a strong bond between the matrix and the reinforcement. However, the molten state route may produce undesirable reaction products that embrittle the metal/reinforcement interface and lower the material´s strength. Various pieces of research have been conducted to fabricate Metal/MoSi2 composites.

In the work by Ramasesha and Shobu (1998), aluminum was infiltrated into a MoSi2 preform using the reactive melt infiltrating process. MoSi2 powder with an average particle size of 2.93 μm and Al-12.24%Si alloy powder with an average particle size of 17.33 μm were used. For the preforms, compacts of 12 mm diameter pellets with different densities were fabricated: compacts with 40% density were made by cold pressing, and compacts with 85% density were prepared by hot pressing at 1300°C using a graphite die. Each compact was brought to a pressure of 20 MPa. The aluminum alloy powders were also compacted into pellets. The pellets were placed in a graphite crucible, first accommodating the aluminum pellets and the MoSi2 pellets on top of them. The test was performed under a vacuum or with an argon atmosphere for infiltration. The temperature range ranged from 1050°C to 1500 C and the permanence times ranged from 5 to 30 min. The obtained composite was cut in half and prepared metallographically to be analyzed in a scanning electron microscope. The results showed that the MoSi2 compacts with 60% porosity and using a temperature of 1050°C for 15 min, the infiltration was superficial, that is, only around the circumference of the pellet, so it did not penetrate the preform. A similar case occurred with the compact subjected to a temperature of 1100°C and 20 min of permanence, but the infiltrated layer was thick (approximately 6 mm thick). In the sample treated at 1150°C, the infiltration was completed in 20 min, and in another sample subjected to a temperature of 1200°C, it took only 5 min to reach complete infiltration.

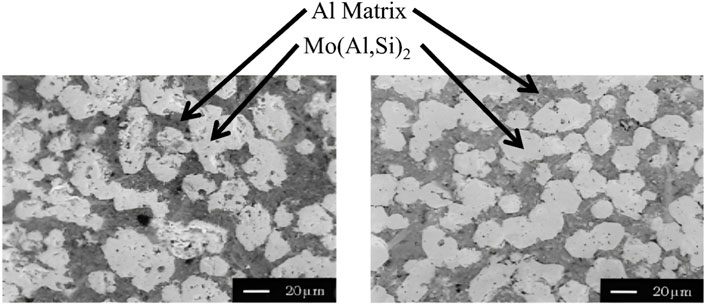

For the cold-pressed samples with excess molybdenum (8 at%), the infiltration was carried out both under vacuum conditions and under an inert atmosphere of argon. A temperature of 1200°C was reached for 20 min and subsequently annealed at 1500°C for 10 min. The images taken by SEM (Figure 9) show that if an inert atmosphere is used, this does not affect the degree of infiltration compared to the sample under vacuum conditions and whose infiltration is completed in 5 min. Regarding the microstructure, it was observed that the Mo(Al,Si)2 phases have a hexagonal morphology in any of the conditions for infiltration. As for the hot-pressed samples, as they have a high density (85%), the infiltration is completed in 20 min. The SEM images show a remarkable similarity when compared to the cold-pressed samples. If the sample was cooled from 1200°C, the morphology of the phases was random, but upon annealing at 1500°C, the morphology changed to a hexagonal-shaped grain. It was concluded that it is possible to infiltrate aluminum into MoSi2 preforms satisfactorily, regardless of the density percentage of the compacts. The factor determining the wettability of MoSi2 by liquid aluminum is the reaction at 1050°C between the SiO2 film on the raw MoSi2 powder and aluminum, causing the disintegration of the thin silica film. However, the degree of infiltration is low. Only at 1100°C does the degree of infiltration increase drastically. Also, the hexagonal morphology of Mo(Al,Si)2 is achieved by performing a heat treatment at 1500°C for 10 min (Ramasesha and Shobu, 1998).

FIGURE 9. MoSi2 preforms containing excess molybdenum. SEM images of cold-pressed samples infiltrated at 1200°C for 20 min and annealed at 1500°C for 10 min: (A) Ar atmosphere, (B) under vacuum (Ramasesha and Shobu, 1998). Aluminum matrix (dark grey region) and Mo(Al,Si)2 phase (clear grey region) (With permission).

Gao et al. (2019) prepared MoSi2(Cr5Si3)–RSiC composites using a combination of precursor impregnation pyrolysis (PIP) and an active melt infiltration process (AAIM) of MoSi2−Si−Cr alloy. Before the infiltration process, a mixture of MoSi2 (15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 wt%), Si (55, 60, 65, and 70 wt%), and Cr (15, 10 wt%) powders with different concentrations of each constituent was made. For the PIP process, RSiC (re-crystallized silicon carbide) preforms were placed in an autoclave and heated to 30°C. Still inside, later, the sample was placed under vacuum conditions (0.01 MPa), and then the PF (phenol-formaldehyde) solution diluted in ethanol at 30°C was injected. This operation was carried out until the preform was immersed in the solution and left for 2 h. Afterward, the preform was centrifuged at 80°C and cured for 2 h. Finally, the preform was carbonized up to 1000°C for 2 h, using an argon atmosphere.

A graphite crucible was used to infiltrate the preforms at a temperature of 1900°C in a furnace under an argon atmosphere. The MoSi2(Cr5Si3) blocks and the RSiC preform were placed inside the crucible and left for 1 h until the alloy infiltrated by capillary action. The resulting samples were prepared and analyzed by various characterization techniques to measure physical properties (bulk density and apparent porosity) and mechanical properties, such as the modulus of rupture by three-point bending tests and fracture stress. Oxidation resistance was also analyzed, and the samples were prepared metallographically to be analyzed by SEM.

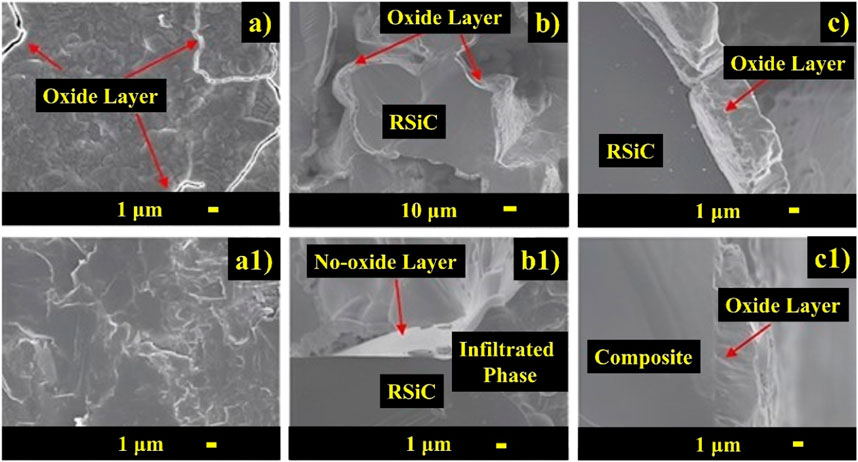

The SEM images (Figure 10) showed that after the infiltration process at 1900°C, the almost dense MoSi2(Cr5Si3)-RSiC composites exhibited an interpenetrating three-dimensional network structure. By increasing oxidation times at 1500°C, the mechanical properties fluctuate due to the synergistic effect of the reduction of surface defects and the relaxation of thermal stress, in addition to the growth of the crystals and thickness increase of the oxidized film (up to 4 μm). The fracture toughness of the MoSi2(Cr5Si3) phase reaches a value of 2.24 MPa m1/2 when reaching a temperature of 1400°C, showing an improvement of 31.70% compared to the values obtained at room temperature. The three-point flexural strength of the MoSi2(Cr5Si3) phase exhibited an improvement of 16.7% from 139.54 MPa at room temperature to 162.90 MPa at 1400°C. The conclusions indicate that: 1) the MoSi2(Cr5Si3) phase exhibited the highest mechanical properties compared to the RSiC phase, and 2) as temperature increased, both the flexural strength and the fracture toughness increased compared to the results obtained at room temperature. Table 2 compares the mechanical properties of MoSi2-based composites manufactured by the liquid-state and the solid-state processing methods, with MoSi2 as the matrix phase.

FIGURE 10. SEM images of the microstructure of surface and fracture of RSiC and MoSi2(Cr5Si3)–RSiC composites oxidized at 1773 K for 100 h: (A) RSiC (surface), (B) RSiC (fracture interior), (C) RSiC (fracture exterior), (A1) MoSi2(Cr5Si3) (surface), (B1) MoSi2(Cr5Si3) (fracture interior), and (C1) MoSi2(Cr5Si3) (fracture exterior) (Gao et al., 2019) (With permission).

There are also works where the mechanical properties of MoSi2-containing composites have been reported (Carter et al., 1988; Gibala et al., 1992; Petrovic, 1995; Ramasesha and Shobu, 1998; Shan et al., 2002; Zeng et al., 2002; Sciti et al., 2006b; Yi et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2019), however, often only two or three properties are reported and no further information is provided in terms of a comparison between the materials composing the composite, so a satisfactory comparison table of the physical, mechanical, or thermal properties is difficult to make, as much of the data is scattered.

3.2 MoSi2 as matrix phase

Vasudévan and Petrovic (1992) state that silicide matrix composites are an alternative to structural ceramic materials, especially composites designed with MoSi2 as a matrix phase. The use of high-temperature materials can enhance cooling and minimize the weight of the component to be designed. For example, in the case of air turbines, this would lead to reduced design and production costs and efficient fuel combustion, which has a beneficial impact on the environment.

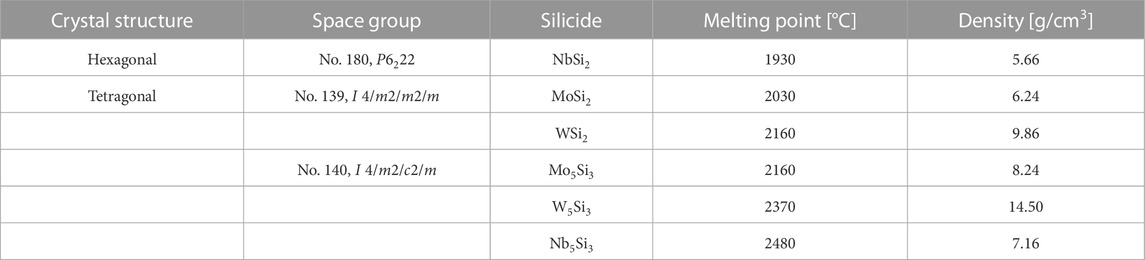

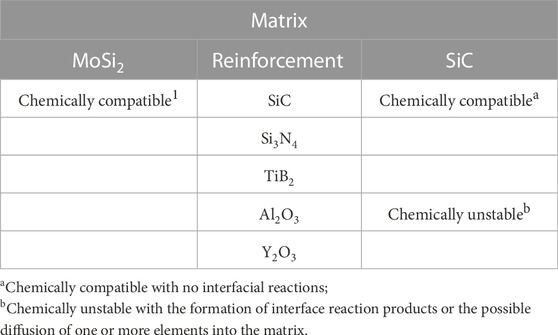

MoSi2 can be combined with other silicides like those listed in Table 3, though some of them are unsuitable, such as W5Si3, because it has a higher density. Other ceramic materials (Table 4), such as some oxides, carbides, and nitrides are chemically compatible with MoSi2, making them attractive for the design and manufacture of MoSi2-containing composites in comparison with SiC, which is chemically unstable with Al2O3 and Y2O3 as reaction products may form at the interface or undesirable elements may diffuse into the matrix, making them unsuitable for use as reinforcements in a SiC matrix composite.

TABLE 3. Crystal structure and properties of high-temperature silicides. Partially from (Petrovic, 1992; Vasudévan and Petrovic, 1992), substantially modified.

TABLE 4. Compatibility of reinforcements with MoSi2 and SiC matrices. Partially from (Vasudévan and Petrovic, 1992), substantially modified.

However, MoSi2-based composites that use the intermetallic as the matrix phase make it a desirable material to be applied in aggressive and corrosive environments, in addition to withstanding high temperatures in a range of 1100°C–1800 °C compared to other silicides that have similar melting points to MoSi2 (Vasudévan and Petrovic, 1992; Lee, 2011).

According to Xiao et al. (1990), significant hardening in MoSi2 can be achieved by strengthening the ductile phase with niobium and W-Re. It was observed that having a 10 vol% Nb, the toughness of MoSi2 is doubled up to an approximate value of 5 MPa m1/2. In a similar case, Nekkanti et al. (1990) observed that using a Nb5Si3-50 vol% Nb can increase the toughness value of 6–12 MPa m1/2. However, these ductile reinforcement phases benefit the silicides’ ductility at room temperature. However, in high-temperature applications, the composites can suffer considerable degradation by creep and oxidation.

According to Petrovic (1995), MoSi2 composites’ creep mechanisms combine dislocation sliding/scaling processes and grain boundary sliding. As stated by Zamani et al. (2012), possible mechanisms for improving the creep resistance with nanoscale second phases (e.g., Ta, Nb, HfO2, ZrO2, SiC, and Mo5Si3) are: 1) that the melting temperature of the second phase is higher than that of MoSi2, 2) that the second phase has a higher creep resistance than MoSi2, and 3) that the unit cell of the second phase is more complex than that of MoSi2. Another possible factor is the second phase volume fraction in the composite.

Gac and Petrovic (1985) demonstrated that the addition of 20 vol% SiC whiskers (grown by the vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) technique) as a reinforcing medium improves the fracture toughness at room temperature (8.20 MPa m1/2) when the MoSi2 matrix is brittle and in addition to increasing the flexural strength at elevated temperatures (310 MPa at 1600°C) when the matrix is ductile.

Carter et al. (1989) showed that SiC whiskers (SiCw) fabricated by the VLS and vapor-solid (VS) techniques are good structural materials for the reinforcement of MoSi2-matrix composites for high-temperature applications. They prepared composites to increase the matrix phase’s mechanical properties by mixing MoSi2 powders with 20 vol% SiC VS and VLS whiskers. Test results at 1200°C showed that composites with SiCw grown by the VS technique outperform the yield strength value (400 MPa) of those produced by the VLS technique (250 MPa) and those of monolithic MoSi2 samples (150 MPa). Nonetheless, above 1200°C, the yield strength of the composites with the VLS whiskers decreases. The latter is ascribed to the dislocations generated during solidification by the long size SiCw (200 µm) at a temperature equal to or below 1000°C, making the mean free path larger than the grain size of the MoSi2 matrix (Carter et al., 1988).

3.3 MoSi2 and other reinforcement materials

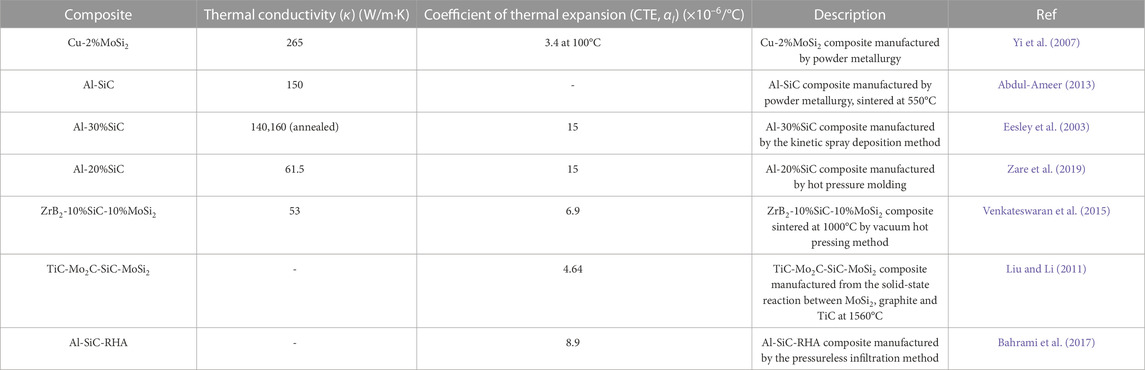

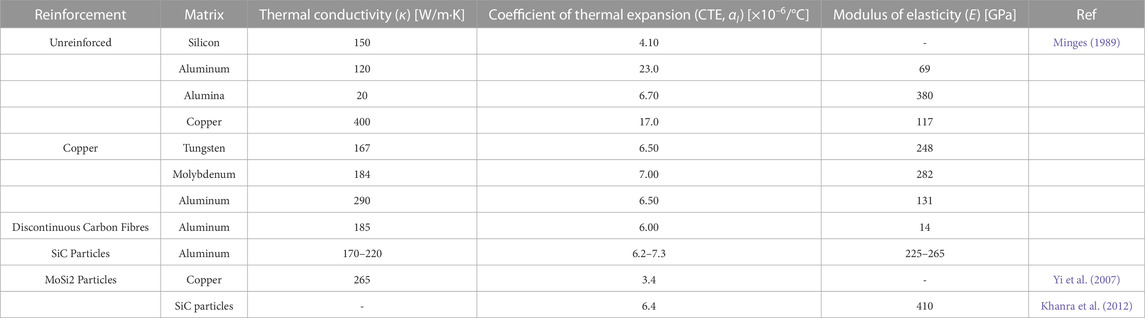

Due to its physical, mechanical, and thermal properties, intermetallic MoSi2 is compatible with metallic or ceramic materials such as aluminum, silicon carbide, and others (Minges, 1989). Composites that contain MoSi2 as a reinforcing/thermal/functional or matrix phase have the advantage of withstanding high temperatures and exhibit good thermal conductivity and a low thermal expansion coefficient, making them ideal materials for electronic packaging applications (Yi et al., 2007; Khanra et al., 2012) (Table 5).

TABLE 5. Thermal and mechanical properties of composite materials with reinforcement and unreinforced for electronic packaging. Reproduced and updated from (Minges, 1989).

When dealing with composites where MoSi2 is used as a reinforcing material, the thermal and mechanical properties become relevant, particularly the thermal conductivity and the thermal expansion coefficient. Table 6 compares the thermal properties of different metal- and ceramic-matrix composites. Due to the ceramic´s chemical composition and crystalline structure, ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) have lower thermal conductivity compared to metal matrix composites (MMCs) (Kingery and McQuarrie, 1954). When comparing the reinforcement materials in the MMCs, using MoSi2 increases the thermal conductivity compared to the composites that use SiC. However, MoSi2 does not improve the thermal conductivity of the Cu matrix (385 W/mK) (Davis, 2001), but it does improve the CTE (CTECu = 1.7 × 10−5/°C) (Davis, 2001). On the other hand, the coefficient of thermal expansion is lower in CMCs compared to MMCs, which can be detrimental for thermal dissipation applications in electronic components; so, amongst MMCs, Al/SiC composites have better thermal properties compared to those that are reinforced with MoSi2.

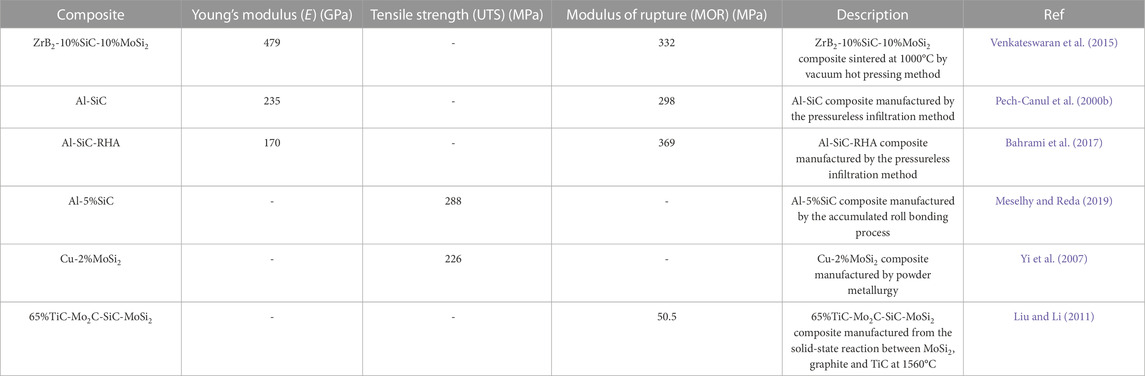

Within the mechanical properties of MMC reinforced with MoSi2, the most reported in scientific articles are Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and modulus of rupture. Properties such as hardness, elongation, and compressive strength are also mentioned, but to a lesser extent. When making a comparison of the mechanical properties between composites (Table 7), CMCs are the ones with the highest Young’s modulus (E = 479 GPa) and modulus of rupture (MOR = 332 MPa) compared to MMC (E = 235 GPa and MOR = 298 MPa), however, when comparing the reinforcement materials used in the MMC, the SiC particles have the highest values of Young’s modulus (E = 235 GPa), tensile strength (UTS = 288 MPa) and modulus of rupture (MOR = 369 MPa) compared to the intermetallic MoSi2 (UTS = 226 MPa and MOR = 50.5 MPa).

4 Potential applications

At the end of the 1980s, the feasibility of manufacturing metallic or ceramic matrix composites reinforced with intermetallic particles or fibers was studied (Fitzer and Remmele, 1985; Gac and Petrovic, 1985). Intermetallic MoSi2 was of great interest due to its chemical, mechanical, and thermal properties, as well as being chemically stable with the matrix of the composite materials (Maxwell, 1945; Schlichting, 1978). The structural applications of MoSi2 as a single-phase material have not been relevant due to its relatively low thermal stability at temperatures higher than 1400°C (Petrovic, 1992; Zumdick et al., 2001). However, most studies published in the last three decades have only focused on the manufacturing and the properties or characteristics offered by composites reinforced with MoSi2, but with limited highlighting of their potential application. In comparison, metal matrix composites reinforced with ceramic particles or fibers such as Al2O3 (Rao and Jayaram, 2001; Zhang et al., 2014) or SiC (Cui, 2007; Leng et al., 2008; Yang and Xi, 2011; Patel et al., 2012; Prosviryakov, 2015) have been extensively studied and reported in different scientific publications, in addition to having a potential application for industries such as the automotive (Allison and Cole, 1993), aerospace (Kainer, 2006b), or electronic (Geffroy et al., 2008; Lu and Wong, 2009; Tong, 2011) industries. It was not until the early 2000s that some applications began to be found for MoSi2-based composites (Cemal et al., 2012), specifically for high-temperature heating elements that may be in corrosive or oxidizing environments. The following paragraphs describe some research works where MoSi2-reinforced composites have a potential application.

Various ceramics and some metallic materials have been used for decades to produce heating elements ranging from graphite (Taylor et al., 1991; Chung, 2002), silicon carbide (Pelissier et al., 1998), or stainless steel (Fang et al., 2020), to name a few. In recent years, MoSi2 has been widely used in producing high-temperature heating elements due to its superior thermal properties compared to the materials mentioned above (Zhang et al., 2019). Wick-Joliat et al. (2021) described the production of high-temperature heating elements using ceramic injection molding (CIM). The sintered product was obtained by embedding MoSi2 particles in a matrix of alumina and vitrified feldspar. The conductivity of the heating element was 1662–1985 S/m when using 17% by volume of MoSi2. According to Wick-Joliat et al. (2021) the conductivity of sintered products can be adjusted by varying the content of the conductive phase, in this case MoSi2.

Intermetallic MoSi2 has also been used as a reinforcement material to manufacture ultra-high-temperature ceramics (UHTC) that can resist temperatures greater than 1800°C since it can increase its oxidation resistance when reaching 1000°C (Zhang et al., 2019). Silvestroni and Sciti (2013) developed a reinforced composite with 15 vol% MoSi2 using different borides and carbides of Zr, Ha, and Ta as matrices. The hot-pressing process was used for manufacturing the composite. Carbide composites attained full density when reaching a temperature range of 1700°C–1900°C, in contrast to boride composites, which reached total density when reaching 1800°C–1900°C. As for the mechanical properties, there was no significant change; however, the composites exhibited excellent resistance in oxidizing environments.

Köbel et al. (2004) fabricated an Al2O3-MoSi2 electroconductive ceramic composite by cold isostatic pressing and vacuum sintering. The composites have potential applications in gas turbine engines. Two volume fractions of MoSi2 were used: 16% and 40%. It was concluded that the addition of MoSi2 slightly influences the densification of the composite material, being 98 and 94% when having 16 and 40 vol% intermetallics, respectively. Composites containing ≥20 vol% of MoSi2 were shown to be electroconductive due to the formation of a three-dimensional percolation network of the conductive phase of MoSi2.

Khanra et al. (2012) have developed a MoSi2-20vol.%SiC component with a potential application for a satellite launch vehicle. The composite was made through the mixture by mechanical milling of Mo, Si, and SiC powders and consolidated by vacuum hot pressing. Beneficial mechanical (E = 410 GPa, MOR = 338 MPa) and thermal (CTE = 6.4 × 10−6°C−1) properties were obtained, compared with unreinforced MoSi2 (E = 395 GPa, MOR = 257 MPa, CTE = 7.79 × 10−6°C−1), due to the good bonding amongst the constituent materials and the uniform distribution of the SiC particles within the matrix. As components designed for oxidation environments and high temperatures, the composites showed excellent oxidation resistance at a temperature of 1500°C.

Recently, intense efforts have been made to develop composite materials with a sustainable approach, where waste can be reused or recycled. In 2019, an attempt was made to use MoSi2 scrap from heating element rods, which, after a grinding process, were used as raw material in MoSi2-SiC coatings, which were applied as a protective coating on graphite substrates. The coated substrates through the spark plasma sintering (SPS) process were subjected to a heat treatment of 1400°C for 90 h. It was observed that a dense film of SiO2 formed on the surface, which prevented oxygen diffusion into the system (Chen et al., 2019).

Developing materials that can withstand extreme environments has been a priority within aerospace technologies. As in the case of existing combustion chambers that have exceeded the maximum working temperature in most superalloys (Zhu et al., 2022a), composite materials that use refractory metals have been excellent options for designing new components. Zhu et al. (2021a); Zhu et al. (2021b) recycled MoSi2-based materials to be used as raw material to manufacture a protective coating of MoSi2-Ta2O5 and MoSi2-HfO2, with which niobium substrates would be protected using the SPS process. Results showed the formation of a Ta-Si-O and HfSiO4 layer in addition to low oxygen permeability in the composite coating after heating at 1500°C for 20 h. It was also shown that the MoSi2-Ta2O5 and MoSi2-HfO2 composite coating exhibited a good metallurgical combination with the niobium substrate, which makes it a potential candidate to be applied in aerospace components due to its resistance to oxidation and high temperatures (T = 1500°C).

MoSi2-based composites have also been proposed to be applied in electronic packaging components, specifically in heat sinks that can be used in laptops, televisions, tablets, etc.; this is because of the frequent problems that these devices have derived from heat (Tapia-López et al., 2021). Therefore, an alternative to this problem is using MMC materials that are good thermal conductors, have a low coefficient of thermal expansion, and are lightweight materials. Aluminum matrix composites reinforced with MoSi2 particles are ideal candidates that meet these requirements (Chung, 1995; Lee, 1995; Blackwell, 2000).

In 1989 Kathryn A. Schmidt and Carl Zweben presented a book chapter in the Electronic Materials Handbook (Schmidt et al., 1989) on composite materials focused on electronic packaging. The chapter focuses on the aspects of thermal management in electronic packaging. It is explained that the materials used in electronic packaging must have similar CTEs; they should coincide with those of the materials to be bonded, especially ceramic and semiconductor substrates since they are very fragile. Composite materials are the solution to this problem as in addition to being low-density materials they can be applied in portable devices, the primary application trend (Zweben, 2001a; Zweben, 2001b; Miracle et al., 2001). Composites with low CTE and high thermal conductivity include silicon carbide particle-reinforced aluminum (Al/SiCp), carbon fiber-reinforced copper (Cu/Cf), carbon fiber-reinforced aluminum (Al/Cf), diamond particle-reinforced copper (Cu/Diamondp), and beryllia particle-reinforced beryllium (Be/BeOp) (Zweben, 1998).

Metal matrix composites (MMCs) offer better characteristics for the controlled elimination of heat, which is convenient because when joining different pieces by brazing or soldering, they can have high thermal impedances (Wang et al., 2019). Hence it is important for MMCs to be used as heat sinks incorporating thin cooling fins and/or fluid cooling ducts (Zweben, 1988; Zweben, 1998). MoSi2-based composites have come to be used in components for electronic packaging, where it is required to dissipate heat quickly (Fackler and Kutz, 2002; Lu and Wong, 2009; Frear et al., 2017). As can be seen, the reinforcement of composites has a role in better highlighting the metallic matrix properties (Shen et al., 1994; Mitra and Mahajan, 1995). In the case of an Al/SiCp composite, a volume fraction of the carbide particles in the range of 0.7 makes it feasible to achieve CTE values like that of silicon (Pech-Canul and Makhlouf, 2000). Currently, investigations on the CTE of Al/MoSi2 composites are very limited. However, based on the MoSi2 and Al volume fraction and their corresponding CTE values (CTE MoSi2 = 7 × 10−6/K; CTE Al = 23 × 10−6/K), the rule of mixtures allows for estimating the CTE. For a 0.7 vol% MoSi2 composite, the CTE value tends to equate with that of ductile iron and cobalt-based superalloys (Callister, 2007). It is generally accepted that MMCs are low-density materials that are relatively inexpensive and easy to produce.

Petrovic and Vasudévan (1992) have proposed a promising future for developing MoSi2-based composite materials specifically for applications that require high temperatures and good oxidation resistance. MoSi2-based composites will require both ceramic [extrusion (Thom et al., 2002)] and metal [powder metallurgy (Corrochano et al., 2009; Corrochano et al., 2010) and mechanical alloying (Koch, 1998)] processing techniques as they require significant volume fractions of ceramic reinforcement for their development. The future of these materials also lies in improving fracture toughness at low temperatures since industrial applications require these values, as in the case of turbines (Petrovic, 2000).

According to a report by Research Reports World (2028) published on the web portal “The Express Wire”, there is an optimistic perspective on the current and future scene of using MoSi2 heating elements. This conclusion is drawn from an analysis of the status of intermetallic materials (MoSi2, Mo5Si3, WSi2) in industrialized countries and companies engaged in producing such heating components. The report details that the global market size for MoSi2 heating elements was estimated to be USD 112.50 million in 2021 and is projected to reach USD 160.40 million by 2028, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.21% in the period covered. The leading distributors of heating elements are concentrated in China, South Korea, and the United States. So, it is expected that in addition to increasing the production of MoSi2 heating elements, there will also be an augmentation of the disposal of such components, which creates an excellent opportunity for the development of composite materials using recycled MoSi2 (Chen et al., 2019).

The present review shows that, albeit with some significant advances that have been made in the processing and characterization, the development of MoSi2-containing composites is an open-ended area with a broad scope for research. The first and foremost investigations were focused on their thermal and oxidation-resistance-related applications. In addition to the former, more recently, the investigations have turned the spotlight on their functional properties, oriented to semiconductor, micro-, and optoelectronic applications. Future systematic studies can be categorized into.

1. The role of MoSi2 as a matrix or reinforcement/thermal/functional phase,

2. Matrix type (metal-, ceramic-, intermetallic-matrix composites),

3. Scale or size of the involved phases (micro-, nano-composites), emphasizing the size role of MoSi2,

4. Processing or fabrication routes (solid, liquid, and vapor), and

5. Uses or applications.

When designing MoSi2-containing composites, one critical aspect is the chemical compatibility of MoSi2 with the other phase(s)Table 4 shows the compatibility-related behavior of some reinforcement phases with MoSi2. Some typical composites reported in the literature are those of ZrB2-10%SiC-10%MoSi2 (Venkateswaran et al., 2015), TiC-Mo2C-SiC-MoSi2 (Liu and Li, 2011), and Cu-2%MoSi2 (Yi et al., 2007) composites. Because they are promising, during about the last 15–20 years, special attention has been paid to UHTC (ultra-high temperature ceramic) matrix composites, particularly to ZrB2–MoSi2 composites, with significant findings (Sciti et al., 2005; Sciti et al., 2006a; Sciti et al., 2006b; Silvestroni and Sciti, 2013; Silvestroni et al., 2018; Grohsmeyer et al., 2019). Furthermore, although MoSi2 has some drawbacks related to its brittleness and harmful oxidation at low temperatures (limiting them for high-temperature structural applications), its global manufacture and use increment are forecast to increase for at least the next 5 years, suggesting that research efforts will steadily grow accordingly. Some detected research areas for future works include 1) mechanical property-related investigations of MoSi2-based composites, particularly those on elongation characteristics. Of course, this goes hand-in-hand with the matrix nature, as in the case of ceramic- and intermetallic-matrix MoSi2 composites, test type, configuration, and specimen size will play significant roles. 2) Another suggested research attention is the determination of the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of some materials, as in the case of Al/MoSi2 composites (Gousia et al., 2016). Inspired by an environmentally friendly materials research philosophy, one key aspect predicated in this review is the exploitation of recycled/reused MoSi2 through designing and manufacturing composites containing this intermetallic. On that score, some investigation results will be reported elsewhere.

5 Conclusion and perspectives

The properties of the intermetallic compound MoSi2 make it a strong candidate for applications where high temperatures and resistance in corrosive environments are paramount. Due to its chemical compatibility with aluminum, copper, SiC, and Al2O3, among other materials, it has been used for developing composite materials either as a matrix or reinforcing/thermal/functional phase. Different processing routes can be used to manufacture metal-matrix composites with MoSi2 as a constituent phase. However, the solid and liquid state methods are preferred for their simplicity and low cost. MoSi2 composites with good mechanical (E = 276.77 GPa) and thermal (κ = 265 W/mK) properties can be attained for applications in turbines, heat sinks, or as a coating for CMC, using the solid- and liquid-state processing routes. Intense research is being conducted to diminish its size to the nanometer scale and synthesize nanocomposites by introducing second phases (e.g., Ta, Nb, HfO2, ZrO2, SiC, and Mo5Si3) to overcome the low toughness and low creep resistance of conventional microcrystalline MoSi2. It is predicted that in the next 5 years, there will be an increase in the production of MoSi2 heating elements, in addition to an augmentation in the scope of the global market. So, it is expected that there will be an increase in the waste of MoSi2 heating elements, making it suitable to develop composites or hybrid composites with recycled MoSi2. Due to the continuous growth of the microelectronics and optoelectronics industries, it can be anticipated that the applications of MoSi2 in microelectronic components or circuits as a contact material will spread rapidly in the forthcoming years.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

Jorge Tapia López gratefully acknowledges Conacyt (National Council of Science and Technology, in Mexico) for granting a doctoral scholarship. The authors also thank the Centre for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (CINVESTAV-IPN) for providing the facilities for developing composite and multifunctional materials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdollah-Pour, H., Piyadeh, F., and Lieblich, M. (2014). Production of AA2124/MoSi2/25p composites and effect of heat treatment on their microstructure, hardness and compression properties. Rev. Metal.50 (4), e030. doi:10.3989/revmetalm.030

Abdul-Ameer, Z. N. (2013). Studying some of mechanical and thermal properties of Al-SiC composites. J. Al-Nahrain Univ.16 (2), 119–123. doi:10.22401/JNUS./16.2.18

Adams, D. F., and Miller, A. K. (1975). An analysis of the impact behavior of hybrid composite materials. Mater. Sci. Eng.19, 245–260. doi:10.1016/0025-5416(75)90112-3

Adeosun, S. O., Osoba, L. O., and Taiwo, O. O. (2014). Characteristics of aluminum hybrid composites. International journal of chemical, molecular. Nucl. Mater. Metallurgical Eng.8 (7). doi:10.5281/zenodo.1097415

Allison, J. E., and Cole, G. S. (1993). Metal·Matrix composites in the automotive industry: Opportunities and challenges. JOM45, 19–24. doi:10.1007/BF03223361

Alman, D. E., Shaw, K. G., Stoloff, N. S., and Rajan, K. (1992). Fabrication, structure and properties of mosi2-base composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A155 (1-2), 85–93. doi:10.1016/0921-5093(92)90315-R

Bahrami, A., Soltani, N., Soltani, S., Pech-Canul, M. I., Gonzalez, L. A., Gutierrez, C. A., et al. (2017). Mechanical, thermal and electrical properties of monolayer and bilayer graded Al/SiC/rice husk ash (RHA) composite. J. Alloys Compd.699, 308–322. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.12.339

Bezzi, F., Burgio, F., Fabbri, P., Grilli, S., Magnani, G., Salernitano, E., et al. (2019). SiC/MoSi2 based coatings for Cf/C composites by two step pack cementation. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc.39 (1), 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2018.01.024

Bhattacharya, A. K., Bhaskaran, T. A., and Ramasesha, S. K. (2002). Aluminum infiltration into molybdenum silicide preforms. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.85 (9), 2364–2366. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.2002.tb00461.x

Bhatti, A. R., and Shatwell, R. A. “Fabrication and characterisation of continuous fibre reinforced MoSi2-based composites,” in Proceedings of ICCM–11, Gold Coast, Australia, July 1997.

Blackwell, G. R. (2000). Electronic packaging Handbook. Boca Raton, Florida, United States: CRC Press.

Callister, W. D. (2007). Materials science and engineering: An introduction. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons.

Carter, D. H., Gibbs, W. S., and Petrovic, J. J. (1988). “Mechanical characterization of SiC whisker-reinforced MoSi2,” in Third int symp on ceramic materials and components for engines (Los Alamos, NM, USA: Los Alamos National Lab), 977.

Carter, D. H., Petrovic, J. J., Honneu, R. E., and Gibbs, W. S. (1989). SiC-MoSi2 composites. Ceram. Eng. Sci. Proc.10 (9-10), 1121–1129. doi:10.1002/9780470310588.ch10

Cemal, M., Uzunonat, Y., Cevik, S., and Diltemiz, F. (2012). Potential of MoSi2 and MoSi2-Si3N4 composites for aircraft gas turbine engines. Recent Adv Aircr Technol. doi:10.5772/38475

Chen, P., Zhu, L., Ren, X., Kang, X., Wang, X., and Feng, P. (2019). Preparation of oxidation protective MoSi2–SiC coating on graphite using recycled waste MoSi2 By one-step spark plasma sintering method. Ceram. Int.45 (17), 22040–22046. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.07.220

Chou, T. C., and Nieh, T. G. (1993b). Kinetics of MoSi2 pest during low-temperature oxidation. J. Mater. Res.8 (7), 1605–1610. doi:10.1557/jmr.1993.1605

Chou, T. C., and Nieh, T. G. (1993a). Mechanism of MoSi2 pest during low temperature oxidation. J. Mater. Res.8 (1), 214–226. doi:10.1557/jmr.1993.0214

Christensen, A. N. (1993). Crystal growth and characterization of the transition metal silicides MoSi2, and WSi2. Jouinal (ivstal (irowth129, 1–2. doi:10.1016/0022-0248(93)90456-7

Chung, D. (2002). Flexible graphite as A heating element. Carbon40, 2285–2289. doi:10.1016/s0008-6223(02)00141-0

Contreras-Cuevas, A., Bedolla-Becerril, E., Salazar-Martínez, M., and Lemus-Ruiz, J. (2018). Metal matrix composites: Wetting and infiltration. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Cook, J., Khan, A., Lee, E., and Mahapatra, R. (1992). Oxidation of mosi2-based composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A155 (1-2), 183–198. doi:10.1016/0921-5093(92)90325-U

Corrochano, J., Hidalgo, P., Lieblich, M., and Ibáñez, J. (2010). Matrix grain characterisation by electron backscattering diffraction of powder metallurgy aluminum matrix composites reinforced with MoSi2 intermetallic particles. Mater. Charact.61 (11), 1294–1298. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2010.08.010

Corrochano, J., Lieblich, M., and Ibáñez, J. (2009). On the role of matrix grain size and particulate reinforcement on the hardness of powder metallurgy Al–Mg–Si/MoSi2 composites. Compos. Sci. Technol.69, 1818–1824. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.03.017

Cui, Y. (2007). Microstructural characterization and properties of SiC/Al composites for electronic packaging fabricated by pressureless infiltration. Mater. Sci. Forum546-549, 1597–1602. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.546-549.1597

Eesley, G. L., Elmoursi, A., and Patel, N. (2003). Thermal properties of kinetic spray Al–SiC metal-matrix composite. J. of Mater. Res.18 (4), 855–860. doi:10.1557/JMR.2003.0117

Fackler, W. C. (2002). “Materials in electronic packaging,” in Handbook of materials selection. Editor M. Kutz (Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 1223–1251.

Fang, S., Wang, R., Ni, H., Liu, H., and Liu, L. (2020). A review of flexible electric heating element and electric heating garments. J. Industrial Text.51, 101S–136S. doi:10.1177/1528083720968278

Fitzer, E., and Remmele, W. “Possibilities and limits of metal reinforced refractory silicides especially molybdenum disilicide,” in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Composite Materials: ICCM-V, San Diego, CA, USA, August 1985.

Frear, D. (2017). “Packaging materials,” in Springer Handbook of electronic and photonic materials. Editors S. Kasap, and P. Capper (Berlin, Germany: Springer), 1312–1327.

Fu, Q.-G., Li, H.-J., Wang, Y.-J., Li, K.-Z., and Shi, X.-H. (2009). B2O3 modified SiC–MoSi2 oxidation resistant coating for carbon/carbon composites by A two-step pack cementation. Corros. Sci.51 (10), 2450–2454. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2009.06.033

Gac, F. D., and Petrovic, J. J. (1985). Feasibility of a composite of SiC whiskers in an MoSi2 matrix. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.68 (8), 200–201. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1985.tb10182.x

Gamutan, J., and Miki, T. (2022). Surface modification of a Mo-substrate to form an oxidation-resistant MoSi2 layer using a Si-saturated tin bath. Surf. Coatings Technol.448, 128938. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2022.128938

Gao, P.-Z., Cheng, L., Yuan, Z., Liu, X.-P., and Xiao, H.-N. (2019). High temperature mechanical retention characteristics and oxidation behaviors of the MoSi2(Cr5Si3)—RSiC composites prepared via A PIP—AAMI combined process. J. Adv. Ceram.8 (2), 196–208. doi:10.1007/s40145-018-0305-1

Geffroy, P. M., Mathias, J. D., and Silvain, J. F. (2008). Heat sink material selection in electronic devices by computational approach. Adv. Eng. Mater.10 (4), 400–405. doi:10.1002/adem.200700285

Gibala, R., Ghosh, A., Van Aken, D. C., Srolovitz, D. J., Basu, A., Chang, H., et al. (1992). Mechanical behavior and interface design of MoSi2-based alloys and composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A155 (1-2), 147–158. doi:10.1016/0921-5093(92)90322-R

Global Molybdenum Disilicide, (2021). MoSi2 Heat Elem Mark Prof Res Rep 2014-2026, Segmented by Play Types, End-Users Major 40 Ctries. or Regions U S A Glob Mark Monit. Available from https://www.globalmarketmonitor.com/reports/666473-molybdenum-disilicide–mosi2–heating-element-market-report.html.

Gokhale, A. B., and Abbaschian, O. J. (1991). The Mo-Si (Molybdenum-Silicon) system. J. Phase Equilibria12 (4), 493–498. doi:10.1007/BF02645979

Gousia, V., Tsioukis, A., Lekatou, A., and Karantzalis, A. E. (2016). Al-MoSi2 composite materials: Analysis of microstructure, sliding wear, solid particle erosion, and aqueous corrosion. J. Mater. Eng. Perform.25 (8), 3107–3120. doi:10.1007/s11665-016-1947-1

Grohsmeyer, R. J., Silvestroni, L., Hilmas, G. E., Monteverde, F., Fahrenholtz, W. G., D’Angió, A., et al. (2019). ZrB2-MoSi2 ceramics: A comprehensive overview of microstructure and properties relationships. Part I: Processing and microstructure. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc.39 (6), 1939–1947. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.01.022

He, R., Tong, Z., Zhang, K., and Fang, D. (2018). Mechanical and electrical properties of MoSi2-based ceramics with various ZrB2-20 vol% SiC as additives for ultra high temperature heating element. Ceram. Int.44 (1), 1041–1045. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.10.043

Houan, Z., Chen, P., Yan, J., and Tang, S. (2004). Fabrication and wear characteristics of MoSi2 matrix composite reinforced by WSi2 and La2O3. Int. J. Refract. Metals Hard Mater.22 (6), 271–275. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2004.09.002

Hu, Q., Luo, P., Qiao, D., and Yan, Y. (2008). Self-propagation high-temperature synthesis and casting of Cu–MoSi2 composite. J. Alloys Compd.464 (1-2), 157–161. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.10.004

Ibano, A., Yoshimi, K., Yamauchi, A., Tu, R., Maruyama, K., Kurokawa, K., et al. (2007). High temperature oxidation behavior of MoSi2 under low pressure atmosphere. Mater. Sci. Forum561-565, 427–430. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.561-565.427

Ito, K., Yano, T., Nakamoto, T., Inui, H., and Yamaguchi, M. (1996). Plastic deformation of MoSi2 and WSi2 single crystals and directionally solidified MoSi2-based alloys. Intermetallics4, S119–S131. doi:10.1016/0966-9795(96)00030-1

Kainer, K. U. (2006a). Basics of metal matrix composites. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: Wiley Online Library.

Kainer, K. U. (2006b). Metal matrix composites. Custom-Made materials for automotive and aerospace engineering. Weinheim, Germany: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

Khanra, G. P., Jha, A. K., GiriKumar, S., Mishra, D. K., Sarvanan, T. T., and Sharma, S. C. (2012). Development of MoSi2-SiC component for satellite launch vehicle. ISRN Metall.2012, 1–6. doi:10.5402/2012/670389

Kingery, W. D., and McQuarrie, M. C. (1954). Thermal conductivity: I, concepts of measurement and factors affecting thermal conductivity of ceramic materials. J. of Am. Ceram. Soc.37 (2), 67–72. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.1954.tb20100.x

Köbel, S., Plüschke, J., Vogt, U., and Graule, T. J. (2004). MoSi2–Al2O3 electroconductive ceramic composites. Ceram. Int.30 (8), 2105–2110. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2003.11.015

Koch, C. C. (1998). Intermetallic matrix composites prepared by mechanical alloying—a review. Mater. Sci. Eng. A244 (1), 39–48. doi:10.1016/S0921-5093(97)00824-1

Krakhmalev, P. V., Ström, E., and Li, C. (2004). Microstructure and properties stability of Al-alloyed MoSi2 matrix composites. Intermetallics12 (2), 225–233. doi:10.1016/j.intermet.2003.10.001

Kulczyk-Malecka, J., Zhang, X., Carr, J., Carabat, A. L., Sloof, W. G., van der Zwaag, S., et al. (2016). Influence of embedded MoSi2 particles on the high temperature thermal conductivity of SPS produced yttria-stabilised zirconia model thermal barrier coatings. Surf. Coatings Technol.308, 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2016.07.113

Kulczyk-Malecka, J., Zhang, X., Carr, J., Nozahic, F., Estournès, C., Monceau, D., et al. (2018). Thermo – mechanical properties of SPS produced self-healing thermal barrier coatings containing pure and alloyed MoSi2 particles. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc.38 (12), 4268–4275. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2018.04.053

Lee, H. (2011). Thermal design: Heat sinks, thermoelectrics, heat pipes, compact heat exchangers, and solar cells. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lee, K. B., Kim, S. H., Kim, D. Y., Cha, P. R., Kim, H. S., Choi, H. J., et al. (2019). Aluminum matrix composites manufactured using nitridation-induced self-forming process. Sci. Rep.9 (1), 20389. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56802-3

Lee, S. (1995). Optimum design and selection of heat sinks. IEEE Trans. Components, Packag. Manuf. Technology-Part A18 (4), 812–817. doi:10.1109/95.477468

Leng, J., Wu, G., Zhou, Q., Dou, Z., and Huang, X. (2008). Mechanical properties of SiC/gr/Al composites fabricated by squeeze casting Technology. Scr. Mater.59 (6), 619–622. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2008.05.018

Lide, D. R. (2004). Handbook of chemistry and physics. Boca Raton, Florida, United States: Taylor & Francis.

Lide, D. R. (2005). Handbook of chemistry and physics. Boca Raton, Florida, United States: CRC Press.

Liton, M. N. H., Helal, M. A., Khan, M. K. R., Kamruzzaman, M., and Farid Ul Islam, A. K. M. (2022). Mechanical and opto-electronic properties of a-MoSi2: A dft scheme with hydrostatic pressure. Indian J. Phys.96 (14), 4155–4172. doi:10.1007/s12648-022-02355-7

Liu, S., and Li, J. (2011). Preparation and characterisation of TiC–Mo2C–SiC–MoSi2 composite ceramic. Micro & Nano Lett.6 (1), 34. doi:10.1049/mnl.2010.0162

Maloney, M. J., and Hecht, R. J. (1992). Development of continuous-fiber-reinforced mosi2-base composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A155 (1-2), 19–31. doi:10.1016/0921-5093(92)90309-O

Maxwell, W. A. (1945). Properties of certain intermetallics as related to elevated-temperature applications I - molybdenum disilicide. Natl. Advis. Comm. Aeronautics.

Melsheimer, S., Fietzek, M., Kolarik, V., Rahmel, A., and Schiitze, M. (1997). Oxidation of the intermetallics MoSi2 and TiSi2 - a comparison. Oxid. Metals47, 139–203. doi:10.1007/bf01682375

Meschter, P. J. (1990). Oxidation kinetics of MoSi2 and MoSi2/reinforcement mixtures. MRS Online Proc. Libr. Opl.213, 1027. doi:10.1557/PROC-213-1027

Meselhy, A. F., and Reda, M. M. (2019). Investigation of mechanical properties of nanostructured Al-SiC composite manufactured by accumulative roll bonding. J. Compos. Mater.53 (28-30), 3951–3961. doi:10.1177/0021998319851831

Minges, M. L. (1989). Electronic materials Handbook: Packaging. Detroit, Michigan, United States: ASM International.

Miracle, D. B., Donaldson, S. L., Henry, S. D., Moosbrugger, C., Anton, G. J., Sanders, B. R., et al. (2001). ASM Handbook - composites. Materials Park, OH, USA: ASM International.

Mitra, R., and Mahajan, Y. R. (1995). Interfaces in discontinuously reinforced metal matrix composites: An overview. Bull. Mater. Sci.18 (4), 405–434. doi:10.1007/BF02749771

Mitra, R., Prasad, N. E., Kumari, S., and Rao, A. V. (2003). High-temperature deformation behavior of coarse-and fine-grained MoSi2 with different silica contents. Metallurgical and materials transactions A. Metall. Mat. Trans. A34, 1069–1088. doi:10.1007/s11661-003-0127-8

Mortensen, A. (2000). Melt infiltration of metal matrix composites. Compr. Compos. Mater., 521–554. doi:10.1016/b0-08-042993-9/00019-x

Mortensen, A., and Jin, I. (1992). Solidification processing of metal matrix composites. Int. Mater. Rev.37 (1), 101–128. doi:10.1179/imr.1992.37.1.101

Nakae, H., Inui, R., Hirata, Y., and Saito, H. (1998). Effects of surface roughness on wettability. Acta Mater.46 (7), 2313–2318. doi:10.1016/s1359-6454(98)80012-8

Nakamura, M., Matsumoto, S., and Hirano, T. (1990). Elastic constants of MoSi2 and WSi2 single crystals. J. of Mater. Sci.25, 3309–3313. doi:10.1007/BF00587691

Nekkanti, R. M., Dimiduk, D. M., Anton, D. L., Martin, P. L., Miracle, D. B., and McMeeking, R. (1990). Ductile-phase toughening in niobium-niobium silicide powder processed composites. Mater. Res. Soc. Symposium Proc.194, 175. doi:10.1557/proc-194-175

Niu, Y., Wang, H., Li, H., Zheng, X., and Ding, C. (2013). Dense ZrB2–MoSi2 composite coating fabricated by low pressure plasma spray (LPPS). Ceram. Int.39 (8), 9773–9777. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.05.038

Patel, M., Saurabh, K., Prasad, V. V. B., and Subrahmanyam, J. (2012). High temperature C/C–SiC composite by liquid silicon infiltration: A literature review. Bull. Mater. Sci.35 (1), 63–73. doi:10.1007/s12034-011-0247-5

Pech-Canul, M. I., Katz, R. N., and Makhlouf, M. M. (2000b). Optimum conditions for pressureless infiltration of SiCp preforms by aluminum alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol.108, 68–77. doi:10.1016/S0924-0136(00)00664-6

Pech-Canul, M. I., Katz, R. N., Makhlouf, M. M., and Pickard, S. (2000a). The role of silicon in wetting and pressureless infiltration of SiCp preforms by aluminum alloys. J. Mater. Sci.35, 2167–2173. doi:10.1023/a:1004758305801

Pech-Canul, M. I., and Makhlouf, M. M. (2000). Processing of Al–SiCp metal matrix composites by pressureless infiltration of SiCp preforms. J. Mater. Synthesis Process.8 (1), 35–53. doi:10.1023/A:1009421727757

Pelissier, K., Chartier, T., and Laurent, J. M. (1998). Silicon carbide heating elements. Ceram. Int.24, 371–377. doi:10.1016/s0272-8842(97)00024-2

Petrovic, J. J. (1995). Mechanical behavior of MoSi2 and MoSi2 composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A192/193, 31–37. doi:10.1016/0921-5093(94)03246-7

Petrovic, J. J. (1992). MoSi2-Based high-temperature structural silicides. MRS Bull.18 (7), 35–41. doi:10.1557/S0883769400037519

Petrovic, J. J. (2000). Toughening strategies for MoSi2-based high temperature structural silicides. Intermetallics8, 1175–1182. doi:10.1016/S0966-9795(00)00044-3