Identifying patients with psychosocial problems in general practice: A scoping review

- 1Center for Health Sciences, Institute of General Practice, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany

- 2Department of General Practice, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Objective: We conducted a scoping review with the aim of comprehensively investigating what tools or methods have been examined in general practice research that capture a wide range of psychosocial problems (PSPs) and serve to identify patients and highlight their characteristics.

Methods: We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews and the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual on scoping reviews. A systematic search was conducted in four electronic databases (Medline [Ovid], Web of Science Core Collection, PsycInfo, Cochrane Library) for quantitative and qualitative studies in English, Spanish, French, and German with no time limit. The protocol was registered with Open Science Framework and published in BMJ Open.

Results: Of the 839 articles identified, 66 met the criteria for study eligibility, from which 61 instruments were identified. The publications were from 18 different countries, with most studies employing an observational design and including mostly adult patients. Among all instruments, 22 were reported as validated, which we present in this paper. Overall, quality criteria were reported differently, with studies generally providing little detail. Most of the instruments were used as paper and pencil questionnaires. We found considerable heterogeneity in the theoretical conceptualisation, definition, and measurement of PSPs, ranging from psychiatric case findings to specific social problems.

Discussion and conclusion: This review presents a number of tools and methods that have been studied and used in general practice research. Adapted and tailored to local circumstances, practice populations, and needs, they could be useful for identifying patients with PSPs in daily GP practice; however, this requires further research. Given the heterogeneity of studies and instruments, future research efforts should include both a more structured evaluation of instruments and the incorporation of consensus methods to move forward from instrument research to actual use in daily practice.

1. Introduction

Since general practitioners (GPs) are usually the first point of contact for people with any health-related concern, patients visit their GP not only for medical reasons but also for psychosocial problems (PSPs) (1–4). Here we take problems to be “a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation”, while we take PSPs to refer to problems related to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age (5). These conditions in which people lead their lives have a profound impact on health.

The relationship between these conditions and health has been investigated in numerous studies and addressed in many health reports (6–9). In a general sense, people with PSPs are vulnerable to negative health outcomes, comorbidities, and have a generally poorer health status (10), while PSPs are also related to several more specific conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, infectious diseases, and psychiatric disorders (11–17). This is because PSPs affect immunological and inflammatory processes (18–20) and are associated with an increased risk of illness, delayed recovery, chronic disease progression, and compromised quality of life and mortality rates (10, 21–23). As one example, individuals who are socially isolated are at risk of premature mortality, comparable to well-documented risk factors, such as smoking and obesity (11, 24–27). Furthermore, psychosocial factors at work have been shown to be associated with a range of health outcomes, such as job strain and increased risk for heart disease or diabetes (28–31). Similarly, job insecurity and unemployment have been found to be associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular and coronary heart disease (32).

The issue of PSPs in general practice began to draw greater attention in the 1990s (33–35) and a vast body of research has investigated their significance since then. For instance, studies show that at least one third of patients under general practice report experiencing PSPs and that GPs are consulted by patients with PSPs at least three times per week (3, 33, 36). Studies most frequently identified family problems, caregiving tasks, violence-related issues, isolation, financial problems, employment problems, problems with physical functioning, and legal problems (3, 35, 37–46). The most frequently occurring social problems encountered in the primary care context are captured in the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2) (47). However, studies also show that GPs only correctly identify a fifth to a half of patients with relevant PSPs and that social factors are not considered to have much importance (37, 48). Possible consequences, such as inadequate diagnoses, non-specific or no intervention or treatment at all, and ineffective use of time have also been extensively described (2, 34, 35, 37, 40, 41, 43, 44, 49–55).

The complexity and heterogeneity around PSPs leads to difficulties in providing or referring to a universally valid concept. This is compounded by the fact that several disciplines, organisations outside the academic context, and policy makers use different concepts, which in turn leads to difficulties in developing or using a practical approach in the form of a systematic and structured instrument to identify patients with PSPs. This is reflected in the official guidelines of medical organisations or societies and official health organisations, where the integration of the psychosocial perspective into medicine is widely demanded, but concrete steps for practice are still lacking (3, 10, 55–58).

GPs are in a unique position to take preventive action to promote health and to identify and treat emerging health problems early in routine care. The use of tools to identify patients with PSPs could be useful in this regard. With this in mind, the aim of our study is to provide an overview of the published research in which we present what tools or methods have been studied so far in general practice research that capture a wide range of PSPs and could be used to identify patients presenting with PSPs.

2. Methods

We conducted a scoping review by following the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual (59) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (60). A protocol has been registered with Open Science Framework (OSF) (61) and published in BMJ Open (62). Since the entire review process with its individual phases is iterative and fundamentally a process of developing understanding, hermeneutic principles were applied consisting of two mutually influencing cycles; searching and accessing the literature, and analysis and interpretation (63).

The review process was conducted in an intersubjective manner as part of the collaborative research process. Collaboration provides a check and balance through which an analytical consensus can be reached that allows for a more comprehensive interpretation and for the group analysis to move beyond individually preconceived perspectives. Through the process of multiple researchers articulating, clarifying, and challenging their initial interpretations, consensus was reached on which studies should be included, which represented the relevant information for extraction, and how they should be summarised and classified (64).

2.1. Inclusion criteria

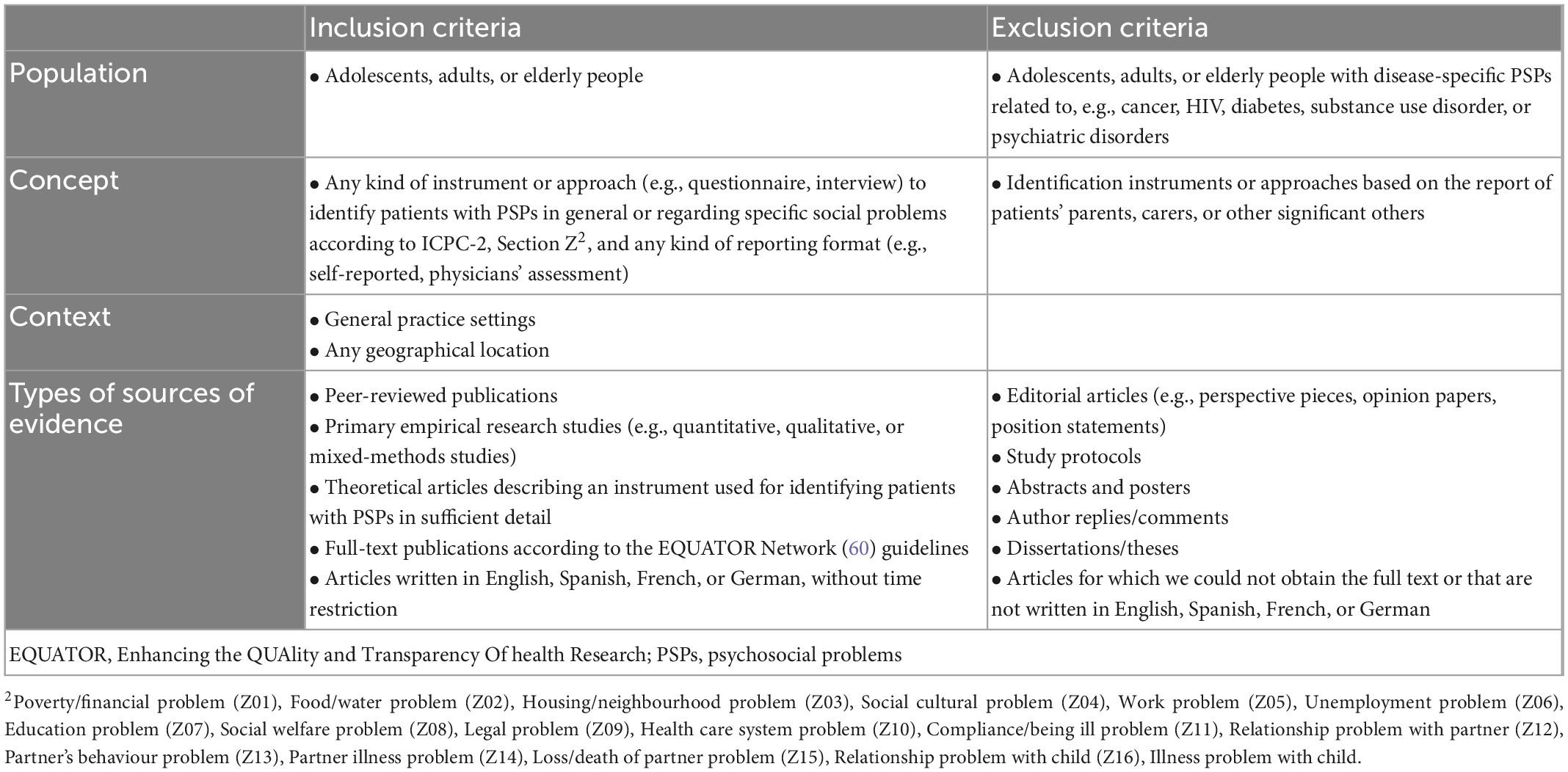

Evidence sources were considered for inclusion if they met the criteria specified by the JBI based on the population, concept, and context framework (59) (Table 1). Included evidence sources were required

Table 1. Eligibility criteria based on study population, context, concept, and types of sources of evidence.

(1) to refer to the adolescent, adult, or elderly population in general practice settings and

(2) to describe any kind of tool or approach to identify patients with PSPs.

We took into consideration articles that included PSPs in general, as well as articles that focused on specific social problems according to the ICPC-2. As the term “psychosocial problems” is used very differently and inconsistently in different publications and even within the same publication, no strict definition was set as an inclusion criterion and therefore we also included publications that refer to PSPs but were labelled as, for example, “mental health problems,” “psychological distress,” or “emotional stress.” This approach was taken to ensure that the descriptions in the articles identified in the search could use any definition of PSPs and still be included. However, we wanted the “social” aspect to be present and were particularly interested in tools that focus on assessing patients’ problems rather than making a formal diagnosis. This process was carried out through an independent review of the full texts by two reviewers and consensus building when conflicts arose.

In line with the characteristics of a scoping review, all types of empirical research studies were included (59). Not all articles reported studies. In those cases where no study was reported, but an instrument or approach for identifying patients with PSPs was described in sufficient detail, the articles were included. The search was limited to references published in English, Spanish, French, and German, without time restriction, and from any geographical location. We excluded articles in which the population described consisted of patients with PSPs related to specific chronic diseases or conditions (e.g., cancer, HIV, diabetes, substance use, or psychiatric disorders) as there are specific research areas for these and their inclusion would have been beyond the scope of our study and inconsistent with our focus on the general population. We also excluded studies where the identification tools or approaches were based on reports from third parties, (e.g., parents), rather than from the participants themselves or a healthcare professional.

2.2. Search strategy

A preliminary search was conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid) database to gain familiarity and an overview and to identify key terms. We developed a search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) (see Supplementary Table 1) and adapted this strategy to the databases PsycInfo, the Cochrane Library, and the Web of Science Core Collection. The search took place from March to April 2021. We hand-searched and screened the reference lists of the included evidence sources to identify other potential references. We screened the reference lists of systematic reviews and scoping reviews which examined studies potentially fitting our inclusion criteria for further relevant articles. Search results were exported into EndNote 20. After elimination of duplicates, the remaining references were uploaded to Covidence for screening and data extraction. An updated search was performed in June 2022.

2.3. Source of evidence screening and selection

Two reviewers (RS, TD) independently screened the references by title and abstract. The full texts of selected articles were then retrieved and fully read by the same two reviewers. In both steps, discrepancies between reviewers’ assessments were discussed and solved by consensus. A list of included studies is presented in Supplementary Table 2.

2.4. Data extraction

A data extraction template was devised by the primary author (RS) to capture information relevant to the research question (see Supplementary Table 3). Two reviewers (RS, TD) independently performed a pilot data extraction on a random sample of five articles and subsequently refined the form. Data extraction was conducted independently by RS and a study assistant who met frequently with TD to discuss the process and refine the data extraction form to ensure that all information relevant to answering the research question was extracted from the publications. Reviewers extracted findings as reported, in the form of numerical or narrative summary statements. Disagreements were resolved through consensus building and, if necessary, by involving a third reviewer.

2.5. Data synthesis and analysis

Following data extraction, each study was categorised according to year of publication, country, setting, research design, population, and the tool(s) or method(s) described (see Supplementary Table 4). A narrative of the data was then developed.

2.6. Deviations from the protocol

As there are not only studies but also publications that describe schemes, frameworks, or instruments to theoretically identify patients with PSPs, we decided to refine our inclusion criteria accordingly. For articles reporting Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), we decided to include not only identification tools, which were mostly used to recruit study participants, but also outcome assessment tools if they met our inclusion criteria. The original data extraction form proposed in the protocol was modified during the pilot data extraction phase in order to capture the most relevant aspects of the included articles.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

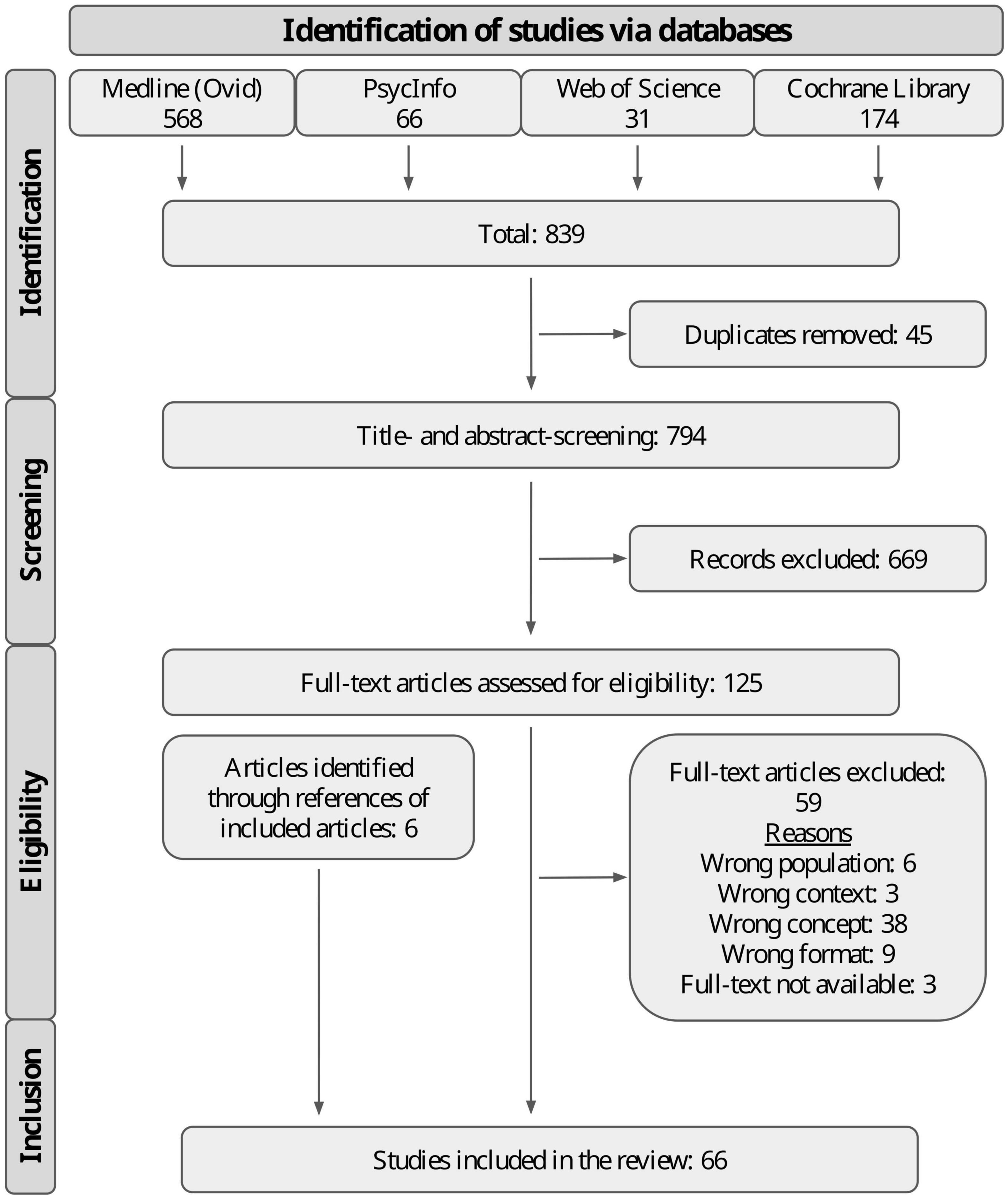

The searches of electronic databases resulted in 839 records. After removing duplicates, a total of 794 titles and abstracts were screened, from which 669 articles were removed, with 125 articles then subjected to a full-text review. In this step, a further 6 additional records were identified through references from identified articles. Of the full-text articles reviewed, 59 were excluded. This left 66 studies that were considered eligible for inclusion and from which relevant information was extracted. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram. Reasons for exclusion are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

3.2. Study characteristics

Supplementary Table 4 presents the general study characteristics of the 66 studies included in this review. The articles included were published between 1978 and 2020. We identified a total of 61 instruments. In this paper, we present only validated instruments (22). Results for the remaining instruments without validation will be published separately.

3.2.1. Context (country and setting)

We identified publications from 18 countries, with the most deriving from the United Kingdom (13), the Netherlands (9), the United States (7), Australia (7), and New Zealand (5). There is a clear concentration of studies conducted in Europe (39), followed by Australasia (12), and North America (9). Of the 66 included studies, 64 come from high-income countries, with 1 article each from an upper-middle income country (Brazil) and a lower-middle income country (Pakistan).

All publications referred to a general practice setting. However, our study allowed for different regional uses of terms. This means that the studied context is not only referred to as general practice (41), but also as primary care (15) and family medicine (8), while the terms general internal medicine (1) and health care centre (1) were also used.

3.2.2. Research design

Most of the studies included were analytical (62). Among these, observational studies were the most common (42), such as cross-sectional studies and prospective studies, followed by experimental studies (12), such as (cluster) randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Descriptive studies were also included, such as narrative/literature reviews (4). No qualitative studies were identified.

3.2.3. Population

Publications included in this review focused mostly on adults (49), with others focused on elderly people (10) and on adolescents and/or young people (7). Specific characteristics among the adult population refer to pregnant women (1), veterans (1), caregivers of patients with a chronic condition (1), and people classified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (1). Almost half of the studies included patients (31), with others focused on caregivers (1) and citizens (2), while the other half worked with patients and physicians and/or practice nurses/staff, and/or community mental health nurses (31). One article focused only on physicians. Study samples show a higher proportion of those identified as of biologically female sex.

3.3. Instrument characteristics

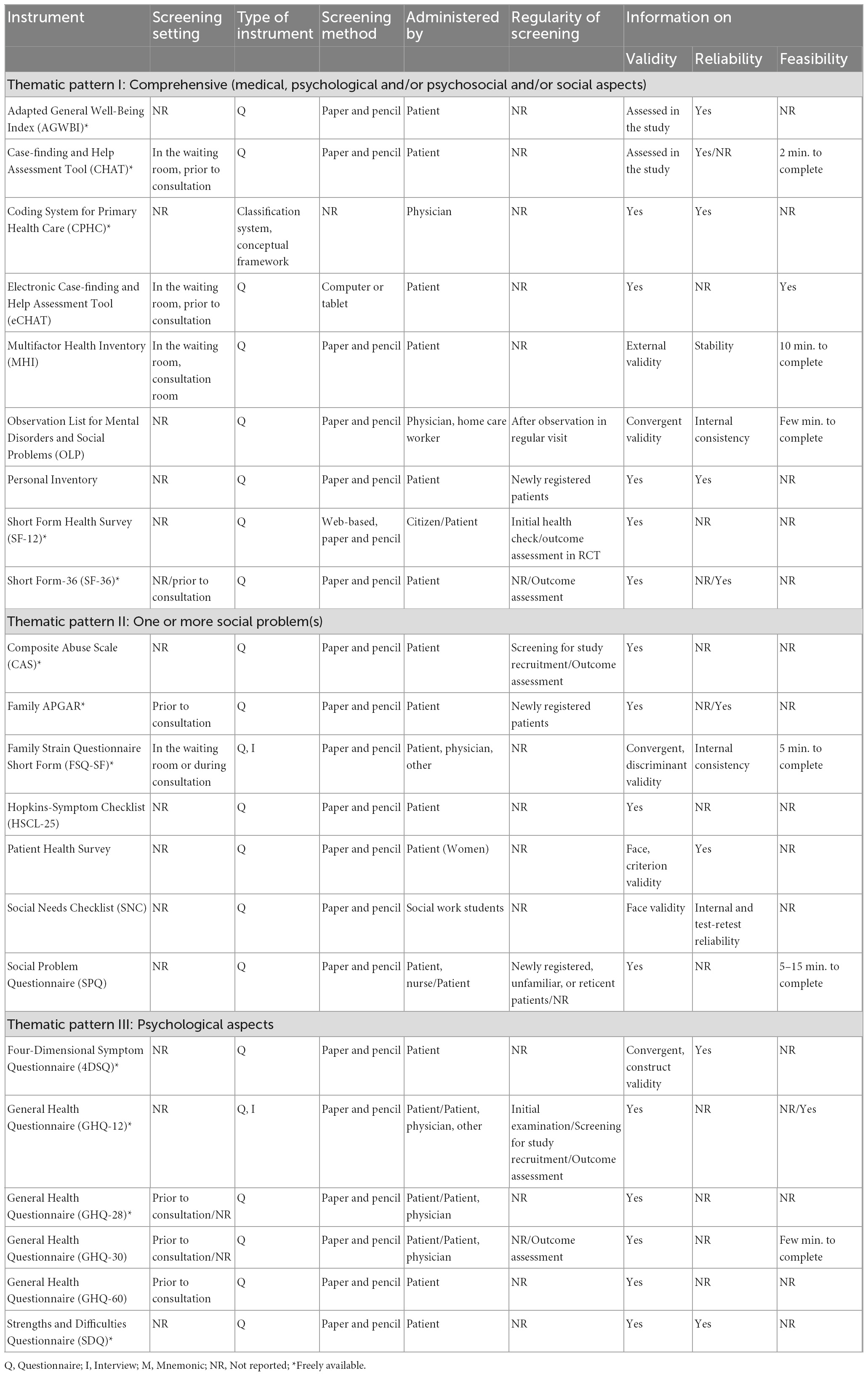

Of the 66 articles, 48 used 1 instrument, 8 publications used 2 instruments, and 10 articles used 3 or more instruments that met our inclusion criteria. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the instruments in terms of instrument name, study, stated focus, and age group. Table 3 contains further aspects, such as screening setting, type of instrument, screening method, mode of administration, regularity of screening, and whether and what information on quality criteria were assessed. In total, 61 instruments or methods were identified. Of these, 22 were reported as validated and are presented below.

The instruments used mostly targeted adults (21), among which two targeted elderly people. One instrument targeted adolescents. For all but one instrument, which contained information reported by the physician, participants themselves were the informants. Few instruments included additional information reported by health professionals (7).

The instruments found were deployed in different formats, mostly as questionnaires (19). Two instruments were used in mixed formats; e.g., as a questionnaire combined with an interview. One instrument was described as a classification system and conceptual framework. The instruments were mostly completed with paper and pencil (19) but also on a tablet or computer (2). For one instrument, the method was not reported.

Information on quality criteria, such as validity, reliability, feasibility, and/or other aspects assessed in relation to the use of the tool were reported differently. When reported, validity was reported in different ways, including internal validity, face, criterion, construct, and external validity. Among these, a validity test was conducted in the study we included for two instruments. For 14 instruments, no detailed information was reported.

Reliability was stated for 10 instruments, of which only four had more detailed information described. Reliability referred to internal consistency, stability, and test-retest reliability. For nine instruments, no information on reliability was provided. For three instruments, different information was available depending on the study description: “yes” and “not reported”.

Feasibility was also reported in different ways, generally not systematically. For the majority of instruments (18), no information was provided. For two instruments, it was stated that feasibility was given, but neither had further details provided. For two instruments, different information was available depending on the study: “yes” and “not reported.”

Other aspects were mentioned for the evaluation of the instruments, such as acceptance, accuracy, applicability, comprehensibility, effectiveness, efficiency, and usefulness, but the information provided was neither detailed nor structured. For two instruments, no information was provided at all. Our research revealed that 12 of the 22 instruments are currently freely available, while 10 are not.

For most instruments (13), no information was provided on the screening setting (e.g., at home, in the waiting room). When reported, the instruments were mostly completed in the waiting room before, during, or after the medical consultation (9). Instruments were completed within five to ten or fifteen minutes (6), but for most instruments, completion time was not reported (16).

For most instruments (13), no information was provided on the regularity of screening. When reported, instruments were used with newly registered and/or unknown patients (4). In three cases, the tool was used to recruit participants for the study and/or to assess outcomes. Two instruments were used for both purposes.

Table 2 provides information on the focus of each instrument. In general, various aspects around PSPs are covered, varying to some extent depending on the study’s objective, target population, and setting. We found considerable heterogeneity in the theoretical conceptualisation, definition, and measurement of PSPs, ranging from psychiatric case findings to specific social problems. To ensure accuracy, we reported the focus of the identified instruments individually.

Finally, because we sought to offer insights into the instruments’ reported focus, it is worth mentioning three thematic patterns to which the instruments can be assigned. The majority of instruments (9) have a comprehensive focus that includes medical, psychological and/or psychosocial, and/or social aspects (e.g., geriatric assessment). In addition, we found seven instruments measuring one or more social problems (e.g., related to family, partner violence, finances). When specific social problems were addressed, they were related to intimate partner violence (IPV) in female participants (2). Finally, we also found instruments (6) measuring psychological aspects (e.g., stress, anxiety, depression) to identify probable “cases.”

Not all studies included a conclusion or a conclusion relevant to our research question. Furthermore, there were often no specific conclusions on individual instruments, as these were mostly described in the context of the general study content and objectives as well as other instruments. Where indicated, conclusions related to validity, appropriate classification, identification/detection rates, benefits and improvement in case finding, feasibility, administration, awareness, acceptability, usefulness, a starting point for further discussion and/or subsequent interventions, implementation in daily practice, and also limitations.

In most cases, the authors used a narrative approach to draw conclusions about the instruments studied. These contained statements such as “insight [provided by the questionnaire] made it easier for GPs to offer patient-centred counselling and ask questions that offer a holistic picture” (SF-12) (65), “acceptable addition to the consultation to facilitate emotionally distressed patients” (GHQ-30) (66), “helpful and effective to get an overview of the problem” (CAS) (67), and “simple, efficient, and well-suited to the resource- and time-strapped primary care environment” (CHAT) (68). The benefits of the tools for patients were seen to be stimulating conversations, drawing attention to patients, and giving them the opportunity to voice their concerns. The benefits for physicians were seen to be improving recognition skills, initiating conversations, modelling/structuring the conversation, and gaining new information, especially with new and/or reluctant patients. Concerns/limitations were expressed that PSPs-recognition does not necessarily lead to subsequent intervention.

4. Discussion

Our research yielded 66 articles that met our inclusion criteria and revealed 61 instruments that were developed or used in general practice research in the general population over a five-decade period. In this paper, we presented 22 instruments that were reported as validated.

We identified a wide range of instruments, including validated instruments (e.g., General Health Questionnaire, GHQ; Short Form Health Survey, SF-12), mnemonics (e.g., HEEADSSS [Home environment, Education and employment, Eating, peer-related Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/depression, Safety from injury and violence] and SHADESS [Strengths, school, Home, Activities, Drugs, Emotions/eating, Sexuality, Safety]), and instruments specifically designed for trial recruitment. Although we only present the validated instruments in this article, our findings show that non-validated instruments account for almost two thirds of all identified instruments. This could be understood to mean that non-validated instruments are considered as useful as validated instruments.

Notably, overall we found a relatively high number of instruments compared to the number of publications, which is understandable due to the broad use of terms related to PSPs, which varied both between and within publications. Our results show that the large number of instruments found cover a broad area, with most having a comprehensive focus that includes medical, psychological, and/or psychosocial, and/or social aspects. We found social and psychosocial aspects included in several instruments, albeit conceived and reported very differently.

In the research literature, we also found that the consideration of social contexts and problems is described using different terms; for example, psychosocial and social problems, health-related social needs or risks, or social determinants of health. The same applies to the content and focus of the instruments. While we focused our search and study selection on problems and risks, there is also essential work that assesses underlying structural aspects that lead to problems. For example, Bourgois and colleagues present a structural vulnerability assessment tool to help physicians go beyond risk behaviours to consider the negative health consequences of poverty, inequality, and discrimination, and identify patients who may benefit from additional health and social services (69).

The influence of social circumstances on health is known and recognised, as is the importance of holistic care concepts that take social factors and needs into account (70, 71). Practical implementation by using tools to identify problems and needs has also gained attention in recent years (72, 73). In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the complex interplay between health, social circumstances, and PSPs has become even more apparent, and concerns are being raised about the psychosocial consequences and long-term negative effects of the pandemic that clinical practice must be prepared to address in order to provide appropriate care and support (74–76).

Similarly, the studies included in our review show the importance of using tools to raise awareness and provide a basis for discussions about PSPs and the associated health risks. In fact, Webb et al., for example, found that a key benefit of using a tool for young people was that it increased confidence in discussing sensitive issues with their GP (77). In Blom et al.’s study, GPs reported that the tools provided them with additional new information and made them more aware of the functions and needs of older people. However, they reported finding it cumbersome to organise multidisciplinary consultations (78). According to Freund and Lous, the use of the questionnaire (SF-12) can provide insight into the relationship between social life, health, lifestyle, and one’s response to stressors and resources. This insight makes it easier for GPs to provide patient-centered counseling and ask questions that provide a holistic picture of the participant (65). Geyti et al. addressed another aspect in their study, noting that the identification of PSPs does not necessarily lead to the initiation of treatment, where they see a need for further research (79).

Recent studies show that the responsibility for the subsequent resolution of PSPs does not have to lie solely with GPs. Studies from Germany show that GPs both feel responsible for dealing with social problems and are able to manage them themselves. However, the need for external support was also expressed, as was the view that interprofessional cooperation is helpful and necessary (3, 80–82). Collaboration between social work and primary care, for example, is considered beneficial and studies show that subjective health, functioning, and self-management can be improved and psychosocial morbidity and barriers to treatment and health maintenance reduced (83, 84). Therefore, identifying patients with PSPs is a crucial step to ensure that patients receive appropriate care in a timely manner, according to their needs and preferences.

The quality criteria and other aspects described for the evaluation of the instruments identified were different, which makes a comparison difficult and does not allow us to formulate a statement on which instrument(s) can be recommended for use in practice. At the same time, the structural and contextual heterogeneity of the instruments makes prioritisation according to purely diagnostic quality criteria impossible. In the absence of this kind of evidence, an approach that combines available data with the experience and insights of clinical experts from multidisciplinary backgrounds is valuable because it provides guidance where none otherwise exists. Consensus procedures, such as the RAND Corporation/University of California Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) Appropriateness Method can be helpful in this regard, as they can be used to define appropriate indications and develop criteria for use, care, and management (85).

From our findings and discussion points, we derive the potential for subsequent research and the link to practice. For example, investigations could be undertaken into whether and which instruments are actually used by general practice professionals in daily practice or why not. Since we did not examine the quality criteria and other criteria used to evaluate the instruments in more detail, as this would have been beyond the scope of our work, future studies could address this aspect by carrying out methodological studies to examine validity, reliability, and feasibility in more depth. If this work is continued, we believe that mixed methods should be used; these are considered particularly important in complex fields such as health and social sciences, as they allow researchers to gain a deeper understanding and answer research questions that cannot be answered by quantitative or qualitative methods alone, thus addressing the complexity of real-life challenges (86). In order for the step from research to practice to succeed, a consensus procedure like the one just described would be an important contribution to develop a selection of instruments that could or should be used in practice from the perspective of practising healthcare professionals. The development of a corresponding guideline would also be worth considering.

When trying to synthesise such a complex topic there are certain limitations and potential biases. First, we did not assess the quality of the included articles, as this is not the aim of a scoping review. Referring to the WHO and ICPC-2 definition/framework in our understanding of PSPs may have led us to exclude articles that other definitions would have encompassed. Because our results refer to information extracted from the included articles, where information on validation was not always provided, instruments may have been excluded even though validation might have been available. Since we did not set time limits, we included articles from 1978 to the present. Both the way research is conducted and reported and the way PSPs are addressed have changed over that time, limiting the summary and comparability of studies. We note that our findings are predominantly based on literature from high-income countries. PSPs vary in areas with different social and cultural norms and belief contexts, so the results cannot simply be extrapolated to other countries or communities on other continents.

We believe these limitations, however, are offset by numerous strengths. A clear strength of this scoping review is the integration of a wide variety of studies using tailored search strings providing a comprehensive summary of the field. Additionally, strengths include the use of rigorous scoping review methods and compliance with standards for conducting and reporting reviews. All articles were reviewed and extracted by two independent authors to reduce the risk of selection bias. Regular meetings and discussions within our multidisciplinary team, consisting of a sociologist, psychologist, GP, and a mathematician ensured the integration of interdisciplinary perspectives. We have included all types of study designs, reflecting the fact that RCTs are not always appropriate for reporting on a complex topic, which PSPs undoubtedly are.

The integration of psychosocial and social aspects into clinical practice is receiving increasing attention in medicine. The use of identification instruments could be helpful in daily practice to identify patients with PSPs who may benefit from greater support in one or more areas, thus promoting whole-person care for the entire population. This review identified 66 articles reporting on 22 validated instruments that have been studied and used in general practice research. Although the diversity of terms and instruments makes compiling, discussing, and summarising the literature a challenge, the diversity of instruments also demonstrates the great potential and the many ways and variations in which instruments can be used in clinical practice to achieve a deeper understanding and more appropriate care. Adapted and tailored to local circumstances, practice populations, and needs, they could be useful in daily GP practice; however, this requires further research. Given the heterogeneity of studies and instruments, future research efforts should include both a more structured evaluation of instruments and the incorporation of consensus methods to move forward from instrument research to actual use of instruments in daily practice.

Author contributions

RS, SU, and TF conceptualised and designed the study. TD made contributions. RS and SU developed the search strategy. RS conducted the literature search, developed the data extraction template, performed data analysis and synthesis, wrote the original draft, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. RS and TD independently performed title and abstract screening and full-text review, independently performed a pilot data extraction on a random sample, and subsequently refined the form. RS and a study assistant conducted data extraction independently and met frequently with TD to discuss the process and refine the data extraction form. TD, SU, and TF critically read and commented on the original draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, which was completed in December 2022.

Acknowledgments

We thank our study assistant Pauline Eisenschmidt for her assistance with data cleaning and processing as well as research activities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.1010001/full#supplementary-material

References

1. DEGAM. DEGAM-Zukunftspositionen. (2013). Available online at: https://www.degam.de/files/Inhalte/Degam-Inhalte/Ueber_uns/Positionspapiere/DEGAM_Zukunftspositionen.pdf (accessed July 6, 2021).

2. Hartmann M, Finkenzeller C, Boehlen F, Wagenlechner P, Peters-Klimm F, Herzog W. Psychosomatische Sprechstunde in der Hausarztpraxis – ein neues Kooperationsmodell von Psychosomatik und Allgemeinmedizin. Balint J. (2018) 19:116–20. doi: 10.1055/a-0795-2048

3. Zimmermann T, Mews C, Kloppe T, Tetzlaff B, Hadwiger M, von dem Knesebeck O, et al. Soziale Probleme in der hausärztlichen Versorgung – Häufigkeit, Reaktionen, Handlungsoptionen und erwünschter Unterstützungsbedarf aus der Sicht von Hausärztinnen und Hausärzten. [Social problems in primary health care: prevalence, responses, course of action, and the need for support from a general practitioners’ point of view]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. (2018) 131–32:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2018.01.008

4. Santo E, Vo M, Uratsu C, Grant R. Patient-defined visit priorities in primary care: psychosocial versus medically-related concerns. J Am Board Fam Med. (2019) 32:513–20. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180380

5. World Health Organization [WHO]. Social determinants of health. (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health (accessed March 4, 2022).

6. Kivimäki M, Batty G, Pentti J, Shipley M, Sipilä P, Nyberg S, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: a multi-cohort study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e140–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30248-8

7. Brunner E. Social factors and cardiovascular morbidity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2017) 74:260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.004

8. Marmot M. Review of social determinants and the health divide in the WHO European region: final report. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2014). p. 188.

9. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling T, Taylor S. Commission on social determinants of health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. (2008) 372:1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6

10. Institute of Medicine, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Committee on Health and Behavior: Research, Practice and Policy. Health and behavior: the interplay of biological, behavioral, and societal influences. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2001). p. 395.

11. Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L, Virtanen M, Jokela M, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. Heart. (2018) 104:1536–42. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312663

12. Kivimäki M, Steptoe A. Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2018) 15:215–29. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.189

13. Everson-Rose S, Lewis T. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. (2005) 26:469–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542

14. Hackett R, Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors in diabetes and cardiovascular risk. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2016) 18:95. doi: 10.1007/s11886-016-0771-4

15. Hamer M, Kivimaki M, Stamatakis E, Batty G. Psychological distress and infectious disease mortality in the general population. Brain Behav Immun. (2019) 76:280–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.12.011

16. Cohen S, Tyrrell D, Smith A. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N Engl J Med. (1991) 325:606–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108293250903

17. Cohen S. Psychosocial vulnerabilities to upper respiratory infectious illness: implications for susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Perspect Psychol Sci. (2021) 16:161–74. doi: 10.1177/1745691620942516

18. Segerstrom S, Miller G. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. (2004) 130:601–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601

19. Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. (2019) 25:1822–32. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0

20. Hänsel A, Hong S, Cámara R, von Känel R. Inflammation as a psychophysiological biomarker in chronic psychosocial stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2010) 35:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.12.012

21. Krantz D, McCeney M. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: a critical assessment of research on coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Psychol. (2002) 53:341–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135208

22. Kuper H, Marmot M, Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med. (2002) 2:267–314. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35401

23. Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. (1999) 318:1460–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7196.1460

24. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith T, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2015) 10:227–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352

25. Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme S, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:2056–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261

26. Beller J, Wagner A. Loneliness, social isolation, their synergistic interaction, and mortality. Health Psychol. (2018) 37:808–13. doi: 10.1037/hea0000605

27. Holt-Lunstad J. The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy Aging Rep. (2018) 27:127–30. doi: 10.1093/ppar/prx030

28. Amick B III, McDonough P, Chang H, Rogers W, Pieper C, Duncan G. Relationship between all-cause mortality and cumulative working life course psychosocial and physical exposures in the United States labor market from 1968 to 1992. Psychosom Med. (2002) 64:370–81. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00002

29. Shirom A, Toker S, Alkaly Y, Jacobson O, Balicer R. Work-based predictors of mortality: a 20-year follow-up of healthy employees. Health Psychol. (2011) 30:268–75. doi: 10.1037/a0023138

30. Niedhammer I, Milner A, Coutrot T, Geoffroy-Perez B, LaMontagne A, Chastang J. Psychosocial work factors of the job strain model and all-cause mortality: the STRESSJEM prospective cohort study. Psychosom Med. (2021) 83:62–70.

31. Kivimäki M, Nyberg S, Batty G, Fransson E, Heikkilä K, Alfredsson L, et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. (2012) 380:1491–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5

32. Virtanen M, Nyberg S, Batty G, Jokela M, Heikkilä K, Fransson E, et al. Perceived job insecurity as a risk factor for incident coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2013) 347:f4746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4746

33. Gulbrandsen P, Fugelli P, Sandvik L, Hjortdahl P. Influence of social problems on management in general practice: multipractice questionnaire survey. BMJ. (1998) 317:28–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.28

34. Huibers M, Beurskens A, Bleijenberg G, van Schayck C. Psychosocial interventions by general practitioners. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2007) 2007:CD003494. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003494.pub2

35. Zantinge E, Verhaak P, Bensing J. The workload of GPs: patients with psychological and somatic problems compared. Fam Pract. (2005) 22:293–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh732

36. Del Piccolo L, Saltini A, Zimmermann C. Which patients talk about stressful life events and social problems to the general practitioner? Psychol Med. (1998) 28:1289–99. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007478

37. Gulbrandsen P, Hjortdahl P, Fugelli P. General practitioners’ knowledge of their patients’ psychosocial problems: multipractice questionnaire survey. BMJ. (1997) 314:1014–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1014

38. Fritzsche K, Sandholzer H, Werner J, Brucks U, Cierpka M, Deter H, et al. Psychotherapeutische und psychosoziale Behandlungsmassnahmen in der Hausarztpraxis. Ergebnisse im Rahmen eines Demonstrationsprojektes zur Qualitätssicherung in der psychosomatischen Grundversorgung. [Psychotherapeutic and psychosocial therapy in general practice. Results of demonstration project on quality management in psychosocial primary care]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. (2000) 50:240–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-13252

39. Grayer J, Cape J, Orpwood L, Leibowitz J, Buszewicz M. Facilitating access to voluntary and community services for patients with psychosocial problems: a before-after evaluation. BMC Fam Pract. (2008) 9:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-27

40. Jobst D, Joos S. Soziale Patientenanliegen—eine Erhebung in Hausarztpraxen. Z Allg Med. (2014) 90:496–501.

41. Laux G, Kühnlein T, Gutscher A, Szecsenyi J. Versorgungsforschung der Hausarztpraxis: Ergebnisse aus dem CONTENT-Projekt 2006–2009. Munich: Urban und Vogel (2011). p. 112.

42. Popay J, Kowarzik U, Mallinson S, Mackian S, Barker J. Social problems, primary care and pathways to help and support: addressing health inequalities at the individual level. Part I: the GP perspective. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2007) 61:966–71. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.061937

43. Van Hook M. Psychosocial issues within primary health care settings: challenges and opportunities for social work practice. Soc Work Health Care. (2003) 38:63–80. doi: 10.1300/j010v38n01_04

44. Vannieuwenborg L, Buntinx F, De Lepeleire J. Presenting prevalence and management of psychosocial problems in primary care in Flanders. Arch Public Health. (2015) 73:10. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0061-4

45. Wilfer T, Braungardt T, Schneider W. Soziale Probleme in der hausärztlichen Praxis. [Social problems in primary care]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. (2018) 64:250–61. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2018.64.3.250

46. Bikson K, McGuire J, Blue-Howells J, Seldin-Sommer L. Psychosocial problems in primary care: patient and provider perceptions. Soc Work Health Care. (2009) 48:736–49. doi: 10.1080/00981380902929057

47. Wonca International Classification. ICPC-2 English. Available online at: https://ehelse.no/kodeverk/icpc-2e–english-version/_/attachment/download/56f8d2b7-803c-46dc-84cd-0b4838eba605:b1b6ccf719152365ab9668c45fb5d0aced197038/ICPC-2e-English.pdf (accessed July 6, 2021).

48. Rosendal M, Vedsted P, Christensen K, Moth G. Psychological and social problems in primary care patients - general practitioners’ assessment and classification. Scand J Prim Health Care. (2013) 31:43–9. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2012.751688

49. Larisch A, Fisch V, Fritzsche K. Kosten-Nutzen-Aspekte psychosozialer Interventionen bei somatisierenden Patienten in der Hausarztpraxis. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. (2005) 34:282–90. doi: 10.1026/1616-3443.34.4.282

50. Vázquez-Barquero J, García J, Simón J, Iglesias C, Montejo J, Herrán A, et al. Mental health in primary care. An epidemiological study of morbidity and use of health resources. Br J Psychiatry. (1997) 170:529–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.529

51. Zimmermann C, Tansella M. Psychosocial factors and physical illness in primary care: promoting the biopsychosocial model in medical practice. J Psychosom Res. (1996) 40:351–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00536-6

52. Frese T, Hein S, Sandholzer H. Feasibility, understandability, and usefulness of the STEP self-rating questionnaire: results of a cross-sectional study. Clin Interv Aging. (2013) 8:515–21. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S41826

53. DEGAM. DEGAM Fachdefinition. (2002). Available online at: https://www.degam.de/fachdefinition.html (accessed July 6, 2021).

54. Kendrick T, King F, Albertella L, Smith P. GP treatment decisions for patients with depression: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. (2005) 55:280–6.

55. Fritzsche K, Sandholzer H, Brucks U, Cierpka M, Deter H, Härter M, et al. Psychosocial care by general practitioners—where are the problems? Results of a demonstration project on quality management in psychosocial primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. (1999) 29:395–409. doi: 10.2190/mcgf-cld4-0fre-n2uk

56. Engert V, Grant J, Strauss B. Psychosocial factors in disease and treatment—A call for the biopsychosocial model. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:996–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0364

57. Mercer S, Gunn J, Bower P, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. BMJ. (2012) 345:e5559. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5559

58. World Health Organization [WHO]. The world health report 2008: primary health care: now more than ever. Geneva: World Health Organization (2008). p. 119.

59. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. ‘Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version)’. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute (2020).

60. Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

61. OSF Registries. Identifying patients with psychosocial problems in general practice: a scoping review protocol. (2021). Available online at: https://osf.io/c2m6z (accessed July 6, 2021).

62. Schwenker R, Kroeber E, Deutsch T, Frese T, Unverzagt S. Identifying patients with psychosocial problems in general practice: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e051383. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051383

63. Boell S, Cecez-Kecmanovic D. A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. (2014) 34:12. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.03412

64. Montague J, Phillips E, Holland F, Archer S. Expanding hermeneutic horizons: working as multiple researchers and with multiple participants. Res Methods Med Health Sci. (2020) 1:25–30. doi: 10.1177/2632084320947571

65. Freund K, Lous J. The effect of preventive consultations on young adults with psychosocial problems: a randomized trial. Health Educ Res. (2012) 27:927–45. doi: 10.1093/her/cys048

66. Smith P. The role of the general health questionnaire in general practice consultations. Br J Gen Pract. (1998) 48:1565–9.

67. MacMillan H, Wathen C, Jamieson E, Boyle M, Shannon H, Ford-Gilboe M, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA. (2009) 302:493–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1089

68. Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Coupe N. Asking for help is helpful: validation of a brief lifestyle and mood assessment tool in primary health care. Ann Fam Med. (2009) 7:239–44. doi: 10.1370/afm.962

69. Bourgois P, Holmes S, Sue K, Quesada J. Structural vulnerability: operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Acad Med. (2017) 92:299–307. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001294

70. Thomas H, Mitchell G, Rich J, Best M. Definition of whole person care in general practice in the English language literature: a systematic review. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e023758. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023758

71. Royal College of General Practitioners [RCGP]. Fit for the future report A vision for general practice. (2019). Available online at: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/getmedia/ff0f6ea4-bce1-4d4e-befc-d8337db06d0e/RCGP-fit-for-the-future-report-may-2019.pdf (accessed July 18, 2022).

72. O’Gurek D, Henke CA. Practical approach to screening for social determinants of health. Fam Pract Manag. (2018) 25:7–12.

73. Billioux A, Verlander K, Anthony S, Alley D. Centers for medicare and medicaid services. Standardized screening for health-related social needs in clinical settings: the accountable health communities screening tool. NAM Perspect. (2017) 7:1–9. doi: 10.31478/201705b

74. Fiorillo A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. (2020) 63:e32. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35

75. Brooks S, Webster R, Smith L, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

76. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, Jones N, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:813–24. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30307-2

77. Webb M, Sanci L, Kauer S, Wadley G. Designing a health screening tool to help young people communicate with their general practitioner. In: Proceedings of the annual meeting of the Australian special interest group for computer human interaction. Parkville (2015). p. 124–33. doi: 10.1145/2838739.2838756

78. Blom J, den Elzen W, van Houwelingen A, Heijmans M, Stijnen T, Van den Hout W, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a proactive, goal-oriented, integrated care model in general practice for older people. A cluster randomised controlled trial: integrated systematic care for older people—the ISCOPE study. Age Ageing. (2016) 45:30–41. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv174

79. Geyti C, Christensen K, Dalsgaard E, Bech B, Gunn J, Maindal H, et al. Factors associated with non-initiation of mental healthcare after detection of poor mental health at a scheduled health check: a cohort study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e037731. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037731

80. Kloppe T, Tetzlaff B, Mews C, Zimmermann T, Scherer M. Interprofessional collaboration to support patients with social problems in general practice—a qualitative focus group study. BMC Prim Care. (2022) 23:169. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01782-z

81. Löwe C, Mark P, Sommer S, Weltermann B. Collaboration between general practitioners and social workers: a scoping review. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e062144. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062144

82. Stumm J, Peter L, Sonntag U, Kümpel L, Heintze C, Döpfmer S. Nichtmedizinische Aspekte der Versorgung multimorbider Patient*innen in der Hausarztpraxis. Welche Unterstützung und Kooperationen werden gewünscht? Fokusgruppen mit Berliner Hausärzt*innen. [Non-medical aspects in the care for multimorbid patients in general practice. What kind of support and cooperation is desired? Focus groups with general practitioners in Berlin]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. (2020) 158–59:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2020.09.001

83. McGregor J, Mercer S, Harris F. Health benefits of primary care social work for adults with complex health and social needs: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. (2018) 26:1–13. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12337

84. Döbl S, Huggard P, Beddoe L. A hidden jewel: social work in primary health care practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. J Prim Health Care. (2015) 7:333–8. doi: 10.1071/hc15333

85. Fitch K, Bernstein S, Aguilar M, Burnand B, LaCalle J, Lázaro P, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND (2001).

86. McBride K, MacMillan F, George E, Steiner G. The use of mixed methods in research. In: P Liamputtong editor. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer (2019). p. 695–713. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_97

87. Hopton J, Hunt S, Shiels C, Smith C. Measuring psychological well-being. The adapted general well-being index in a primary care setting: a test of validity. Fam Pract. (1995) 12:452–60. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.4.452

88. Goodyear-Smith F, Coupe N, Arroll B, Elley C, Sullivan S, McGill A. Case finding of lifestyle and mental health disorders in primary care: validation of the ‘CHAT’ tool. Br J Gen Pract. (2008) 58:26–31. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263785

89. Deliège DA. A classification system of social problems: concepts and influence on GPs’ registration of problems. Soc Work Health Care. (2001) 34:195–238. doi: 10.1080/00981380109517026

90. Goodyear-Smith F, Warren J, Bojic M, Chong A. eCHAT for lifestyle and mental health screening in primary care. Ann Fam Med. (2013) 11:460–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1512

91. Hase H, Luger J. Screening for psychosocial problems in primary care. J Fam Pract. (1988) 26:297–302.

92. Tak E, van Hespen A, Verhaak P, Eekhof J, Hopman-Rock M. Development and preliminary validation of an observation list for detecting mental disorders and social problems in the elderly in primary and home care (OLP). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2016) 31:755–64. doi: 10.1002/gps.4388

93. Hilliard R, Gjerde C, Parker L. Validity of two psychological screening measures in family practice: personal inventory and family APGAR. J Fam Pract. (1986) 23:345–9.

94. King M, Nazareth I. The health of people classified as lesbian, gay and bisexual attending family practitioners in London: a controlled study. BMC Public Health. (2006) 6:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-127

95. Schreuders B, van Marwijk H, Smit J, Rijmen F, Stalman W, van Oppen P. Primary care patients with mental health problems: outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Gen Pract. (2007) 57:886–91. doi: 10.3399/096016407782317829

96. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, Chondros P, Brown S, Valpied J, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2013) 382:249–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

97. Geyti C, Dalsgaard E, Sandbæk A, Maindal H, Christensen K. Initiation and cessation of mental healthcare after mental health screening in primary care: a prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. (2018) 19:176. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0864-9

98. Raine R, Lewis L, Sensky T, Hutchings A, Hirsch S, Black N. Patient determinants of mental health interventions in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. (2000) 50:620–5.

99. Hassink-Franke L, van Weel-Baumgarten E, Wierda E, Engelen M, Beek ML, Bor H, et al. Effectiveness of problem-solving treatment by general practice registrars for patients with emotional symptoms. J Prim Health Care. (2011) 3:181–9. doi: 10.1071/hc11181

100. Sanci L, Chondros P, Sawyer S, Pirkis J, Ozer E, Hegarty K, et al. Responding to young people’s health risks in primary care: a cluster randomised trial of training clinicians in screening and motivational interviewing. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0137581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137581

101. De La Revilla L, Zurita R, De Los Ríos A, Castro J. Un método de detección de problemas psicosociales en la consulta del médico de familia. Aten Primaria. (1997) 19:133–7.

102. Vidotto G, Ferrario S, Bond T, Zotti A. Family strain questionnaire—short form for nurses and general practitioners. J Clin Nurs. (2010) 19:275–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02965.x

103. Stefansson C, Svensson C. Identified and unidentified mental illness in primary health care—social characteristics, medical measures and total care utilization during one year. Scand J Prim Health Care. (1994) 12:24–31. doi: 10.3109/02813439408997053

104. Wasson J, Jette A, Anderson J, Johnson D, Nelson E, Kilo C. Routine, single-item screening to identify abusive relationships in women. J Fam Pract. (2000) 49:1017–22.

105. Cook C, Freedman J, Freedman L, Arick R, Miller M. Screening for social and environmental problems in a VA primary care setting. Health Soc Work. (1996) 21:41–7. doi: 10.1093/hsw/21.1.41

106. Al-Shammari S. Screening for psychosocial problems among primary care patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Ment Health. (1994) 23:69–80. doi: 10.1080/00207411.1994.11449294

107. Saltini A, Mazzi M, Del Piccolo L, Zimmermann C. Decisional strategies for the attribution of emotional distress in primary care. Psychol Med. (2004) 34:729–39. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001260

108. Terluin B, van Marwijk H, Adèr H, de Vet H, Penninx B, Hermens M, et al. The four-dimensional symptom questionnaire (4DSQ): a validation study of a multidimensional self-report questionnaire to assess distress, depression, anxiety and somatization. BMC Psychiatry. (2006) 6:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-34

109. Van der Pasch M, Verhaak P. Communication in general practice: recognition and treatment of mental illness. Patient Educ Couns. (1998) 33:97–112. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00057-8

110. Kapur N, Hunt I, Lunt M, McBeth J, Creed F, Macfarlane G. Psychosocial and illness related predictors of consultation rates in primary care—a cohort study. Psychol Med. (2004) 34:719–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001223

111. Kendrick T, Simons L, Mynors-Wallis L, Gray A, Lathlean J, Pickering R, et al. A trial of problem-solving by community mental health nurses for anxiety, depression and life difficulties among general practice patients. The CPN-GP study. Health Technol Assess. (2005) 9:1–104. doi: 10.3310/hta9370

112. Mirza I, Hassan R, Chaudhary H, Jenkins R. Eliciting explanatory models of common mental disorders using the short explanatory model interview (SEMI) urdu adaptation—a pilot study. J Pak Med Assoc. (2006) 56:461–3.

113. Gonçalves D, Fortes S, Tófoli L, Campos M, Mari Jde J. Determinants of common mental disorders detection by general practitioners in primary health care in Brazil. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2011) 41:3–13. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.b

114. Shiber A, Maoz B, Antonovsky A, Antonovsky H. Detection of emotional problems in the primary care clinic. Fam Pract. (1990) 7:195–200. doi: 10.1093/fampra/7.3.195

115. Watts S, Bhutani G, Stout I, Ducker G, Cleator P, McGarry J, et al. Mental health in older adult recipients of primary care services: is depression the key issue? Identification, treatment and the general practitioner. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2002) 17:427–37. doi: 10.1002/gps.632

116. de la Revilla Ahumada L, de los Ríos Alvarez A, Luna del Castillo J. Use of the goldberg general health questionnaire (GHQ-28) to detect psychosocial problems in the family physician’s office. Aten Primaria. (2004) 33:417–22; discussion 423–5. doi: 10.1016/s0212-6567(04)79426-3

117. Rabinowitz J, Shayevitz D, Hornik T, Feldman D. Primary care physicians’ detection of psychological distress among elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2005) 13:773–80. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200509000-00005

118. Verhaak P, Wennink H, Tijhuis M. The importance of the GHQ in general practice. Fam Pract. (1990) 7:319–24. doi: 10.1093/fampra/7.4.319

119. Verhaak P, Tijhuis M. Psychosocial problems in primary care: some results from the dutch national study of morbidity and interventions in general practice. Soc Sci Med. (1992) 35:105–10. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90157-l

120. Odell S, Surtees P, Wainwright N, Commander M, Sashidharan S. Determinants of general practitioner recognition of psychological problems in a multi-ethnic inner-city health district. Br J Psychiatry. (1997) 171:537–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.537

121. Corser C, Philip A. Emotional disturbance in newly registered general practice patients. Br J Psychiatry. (1978) 132:172–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.132.2.172

Keywords: primary care, general practice, psychosocial problems, social problems, identification tools, scoping review

Citation: Schwenker R, Deutsch T, Unverzagt S and Frese T (2023) Identifying patients with psychosocial problems in general practice: A scoping review. Front. Med. 9:1010001. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1010001

Received: 02 August 2022; Accepted: 21 December 2022;

Published: 08 February 2023.

Edited by:

Ana Clavería, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Galicia Sur (IISGS), SpainReviewed by:

Leo Pas, Catholic University Leuven, BelgiumRosa Magallon, University of Zaragoza, Spain

Patrice Nabbe, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, France

Copyright © 2023 Schwenker, Deutsch, Unverzagt and Frese. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosemarie Schwenker,  rosemarie.schwenker@uk-halle.de

rosemarie.schwenker@uk-halle.de

Rosemarie Schwenker

Rosemarie Schwenker Tobias Deutsch

Tobias Deutsch Susanne Unverzagt

Susanne Unverzagt Thomas Frese1

Thomas Frese1