Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- 1Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Erasmus MC Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 2Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry/Psychology, Erasmus MC Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 3Dutch Alopecia Association, ’s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands

- 4IPSO Institutes for Psychosocial Oncology, Almere, Netherlands

- 5Department of Dermatology, Center of Pediatric Dermatology, Erasmus MC Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Introduction: Alopecia areata (AA) is a non-scarring hair loss condition, subclassified into AA, alopecia universalis, and alopecia totalis. There are indications that people with AA experience adverse psychosocial outcomes, but previous studies have not included a thorough meta-analysis and did not compare people with AA to people with other dermatological diagnoses. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to update and expand previous systematic reviews, as well as describing and quantifying levels of anxiety, depression, and quality of life (QoL) in children and adults with AA.

Methods: A search was conducted, yielding 1,249 unique records of which 93 were included.

Results: Review results showed that people with AA have higher chances of being diagnosed with anxiety and/or depression and experience impaired QoL. Their psychosocial outcomes are often similar to other people with a dermatological condition. Meta-analytic results showed significantly more symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults with AA compared to healthy controls. Results also showed a moderate impact on QoL. These results further highlight that AA, despite causing little physical impairments, can have a significant amount on patients’ well-being.

Discussion: Future studies should examine the influence of disease severity, disease duration, remission and relapse, and medication use to shed light on at-risk groups in need of referral to psychological care.

Systematic review registration: [https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/], identifier [CRD42022323174].

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a hair loss condition with a lifetime prevalence of 2.1% (1). AA has a peak onset between 25 and 29 years old, with a median age at diagnosis of 31 for males and 34 for females. It occurs more frequently in people with a non-white ethnicity (2). Males and females appear to be affected equally often (2), however research has also reported females to be slightly more likely to experience AA (2). AA is typically divided into AA (patchy hair loss), alopecia universalis (AU; total loss of scalp hair), alopecia totalis (AT; total loss of body hair) and alopecia ophiasis (band-like hair loss on the temporal and occipital scalp) (3).

Alopecia areata has an unpredictable disease course characterized by relapse and remission (4). Full hair regrowth may be observed in 50–80% of patients (5, 6), but relapse rates of 30–52% have been reported (5) with around 30% of patients with AA eventually progressing to complete hair loss (6). Relapse is more likely in patients with an earlier onset of AA, but is not related to gender, clinical severity and treatment given (5). Furthermore, medication often fails to provide sustained hair regrowth (3).

There are indications that people with AA experience adverse psychosocial outcomes. Qualitative studies, for instance, have shown that patients reported considerable distress (7). Feelings of sadness, insecurity, inadequacy, and self-consciousness (8), as well as feelings of depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts (7) were prevalent. The majority of qualitative research highlights that people struggle with everyday activities, such as participating in sports or social events, due to a fear of their appearance being noticed (7–9). The unpredictable nature of AA was also highlighted as a source of distress in particular (7, 8) and women seem to report more stress and distress than men (10, 11).

Most quantitative research has focused on anxiety, depression or quality of life (QoL). For anxiety, a meta-analysis including eight studies by Okhovat et al. (12) showed that people with AA are 2.50 times more likely to experience anxiety. However, it is unclear how the papers were selected and what type of control group was included in the meta-analysis. Other studies have shown that people with AA have a higher chance of being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder than healthy controls (13). When the amount of anxiety symptoms of people with AA is compared to people with other dermatological diagnoses mixed results have been found (14).

When looking at depression, the aforementioned meta-analysis found that people with AA are 2.71 times more likely to experience depression (12). This result is corroborated by other studies reporting people with AA to be more likely to be diagnosed with depression (13, 15). As for anxiety, it is unclear how people with AA compare to people with other dermatological diagnoses (16, 17).

A systematic review conducted in 2018 has shown that AA has a considerable impact on QoL (18). However, it remained unclear how QoL was related to disease severity (18). Furthermore, people with AA were not compared to people with different dermatological diagnoses in this review. More recent research has reported a moderate effect on QoL (19), as well as no effect (20). Comparisons to people with a different dermatological diagnosis have yielded mixed results. For instance, one study comparing people with AA to people with alopecia androgenetica reported people with AA to have better QoL (21), while another study found the opposite result (22).

Although previous systematic reviews on psychosocial consequences of AA have been conducted (e.g., 18, 23), it remains unclear how people with AA compare to people without AA or people with a different dermatological diagnosis. In addition, these reviews have not highlighted the psychosocial impact of AA on different age groups (i.e., children or adults). Therefore, the purpose of the current systematic review and meta-analysis was to update and expand previous systematic reviews, as well as describing and quantifying levels of anxiety, depression, and QoL in patients with AA, AU, or AT. We also aimed to explore whether gender or age would influence the amount of anxiety, depression, and QoL experienced by people with AA. We specifically sought to answer the following research question: What is the impact of living with alopecia areata, alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis on levels of anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults? We also wanted to know how levels of anxiety, depression, and QoL of people with AA compared to people with a different dermatological condition and to healthy controls.

Materials and methods

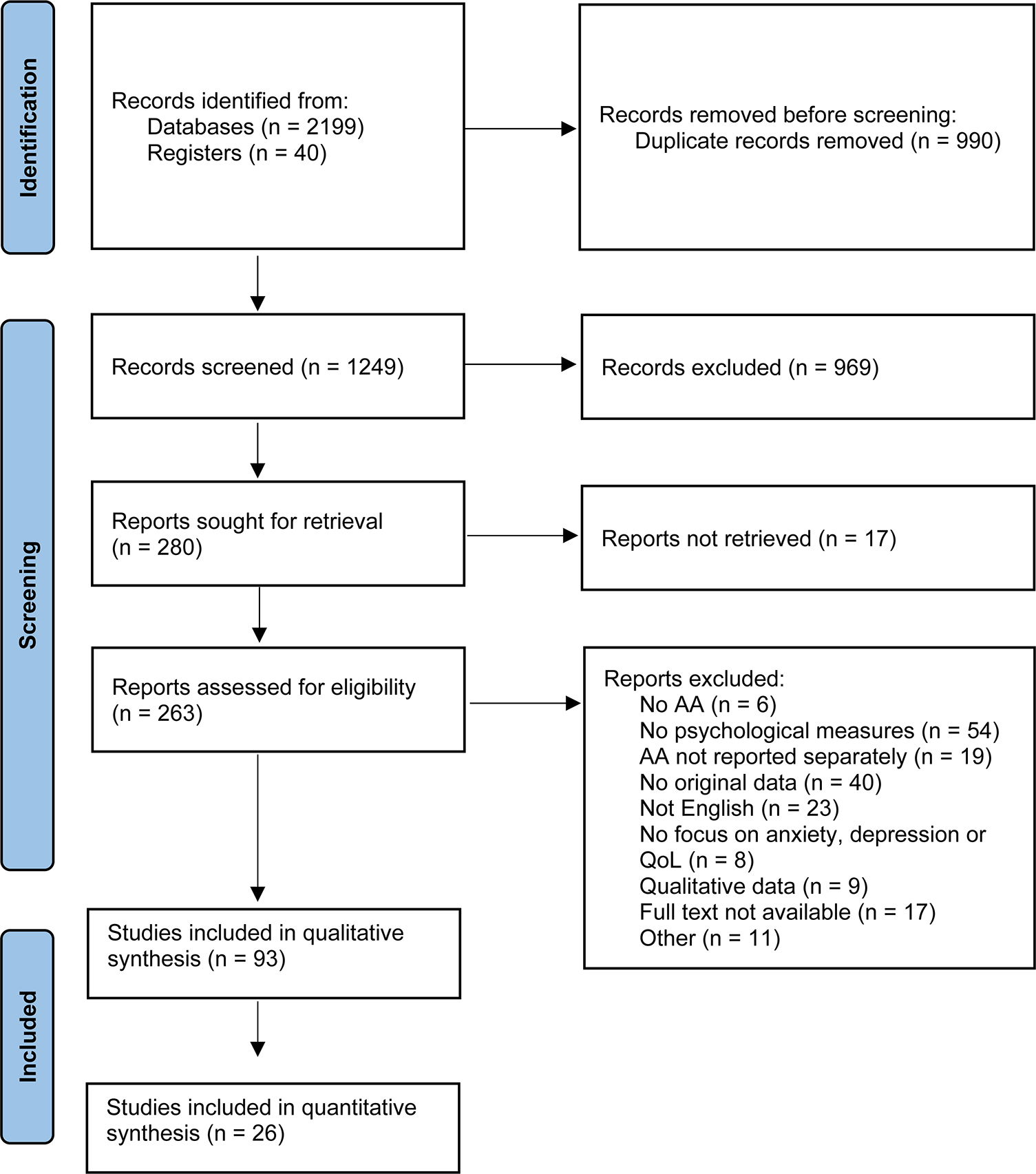

This article was written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (24) and was registered prospectively in the international prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO, registration number CRD42022323174. The protocol was registered with a broad focus on psychological impact of AA, as it was unclear how many papers the search would yield. After selection of relevant papers, a decision was made to focus only on anxiety, depression and QoL and a further nine papers were excluded (see Figure 1).

Search strategy

As this article was part of a bigger project for the Dutch Alopecia Association, a broad search focusing on the psychosocial impact of living with AA was conducted by a research librarian on 28 March 2022. The following databases were searched from inception: Embase, Medline, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar. The search included terms, both Mesh and free text, related to alopecia and the psychosocial impact, without restrictions on language or publication date. Only published, peer-reviewed papers were used. The full search is displayed in Supplementary material.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following eligibility criteria: (a) studied a sample with AA, AU, and/or AT, (b) reported quantitative data on anxiety, depression or QoL, and (c) the paper was an original research paper. Studies were excluded if they (a) reported no original data (e.g., case-reports, conference abstracts, and systematic reviews), (b) were not written in English, or (c) did not separate AA from other medical diagnoses. No criteria were set for the amount of timepoints in an article (i.e., the article being cross-sectional or longitudinal). In case of a longitudinal intervention study, only the baseline data were included.

Study selection

Studies were selected if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two reviewers (MD and KM) independently assessed the title and abstract. The interrater agreement was 81.55%. Discrepancies were resolved using consensus. Afterward, the two reviewers independently assessed the full text for eligibility. Interrater agreement for this step was 87.46%. Discrepancies were again resolved using consensus. One of the reviewers (MD) checked the reference list of included articles for additional relevant references. Any references deemed relevant were first screened based on title and abstract. If still relevant, the full-text was read. When the article met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, it was included in the review. Endnote 20 was used to manage references.

Data extraction

Data collection was done by one researcher (MD) and checked by another researcher (KM) using a data extraction form. The following data were extracted: type of alopecia, sample size, percentage male, mean age (SD), age range, method involved (questionnaire or interview), main conclusions, mean score (when method is questionnaire), mean prevalence of symptoms/diagnosis, any relevant comparisons between groups (e.g., anxiety symptoms in AA vs. unaffected controls). Authors of papers were contacted when relevant data for meta-analyses was missing.

Quality and risk of bias

Quality and risk of bias were assessed using the relevant NIH quality assessment tool for controlled intervention studies, observational cohort and cross-sectional studies, case-control studies or before-after studies with no control group [National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH), 2018] (25) or the QAVALS (26). Questions can be answered with “yes, no or cannot determine/not reported/not applicable responses.” We rated >80% points as good, 60–80% points as fair and <60% as poor quality. Quality assessment was performed independently by two reviewers (MD and KM). Half of the articles were discussed in a consensus meeting, after which the remaining half of the papers was checked by one reviewer (MD).

Data synthesis and statistical analyses

All studies were included in the qualitative synthesis. Meta-analyses were conducted for five or more similar studies. As a high level of between-study heterogeneity was expected, a random-effects model was used to pool effect sizes. The Restricted Maximum Likelihood Estimator (REML) was used to calculate heterogeneity variance (27). Means and standard deviations (SDs) of samples were used to compute effect sizes, the standardized mean differences (SMDs), quantified in the form of Hedges’ g (28). When means and SDs were not available, medians were transformed to means and SDs as described by Shi et al. (29). Publication bias was tested by visual inspection of a contour-enhanced funnel plot (30) and Egger’s test in case of ≥10 studies. Exploratory meta-regressions were conducted. For each meta-analysis, one model was created with mean age, percentage male, and quality rating as independent variables. The significance level was set to α = 0.05. Analyses were done using the meta package (31) in RStudio.

Results

Study selection

After removing duplicate records, a total of 1,249 records were retrieved for screening. After title and abstract screening, 280 records were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 93 articles were included for the qualitative synthesis of which 26 articles were also included in the quantitative synthesis. The full selection process is displayed in Figure 1. Overall, 74 papers were of poor quality, 16 papers were of fair quality and 4 papers were of good quality.

A total of 52 papers studied anxiety in children and/or adults with AA. Seven papers (32–38) had a combined research group with children and adults (n = 11,007, Mage = 41.78, 43.63% male), eight papers (39–46) studied children with AA (n = 398, Mage = 11.85, 47.00% male) and 37 papers (13, 14, 17, 19, 22, 37, 38, 47–77) studied adults with AA (n = 88,858, Mage = 40.03, 41.25% male).

For depression, 65 papers were included. Fourteen papers (32–36, 38, 78–84) looked at children and adults (n = 18.638, mean age = 36.26, 43.44% male), nine papers (39–46, 85) studied children (n = 3908, Mage = 11.85, 44.82% male) and 42 papers (13–17, 19, 22, 47–53, 55–66, 68–77, 86–90) studied adults with AA (n = 93,047, Mage = 41.69, 40.39% male).

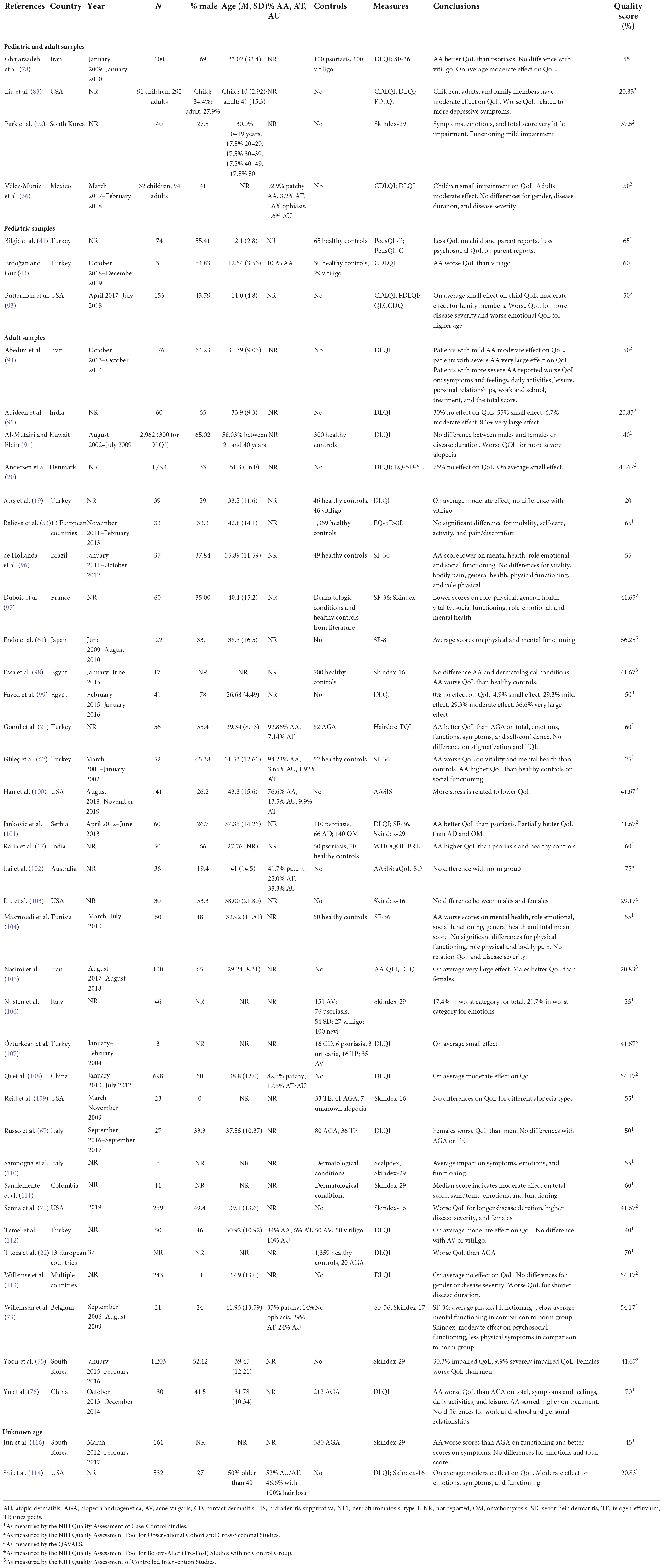

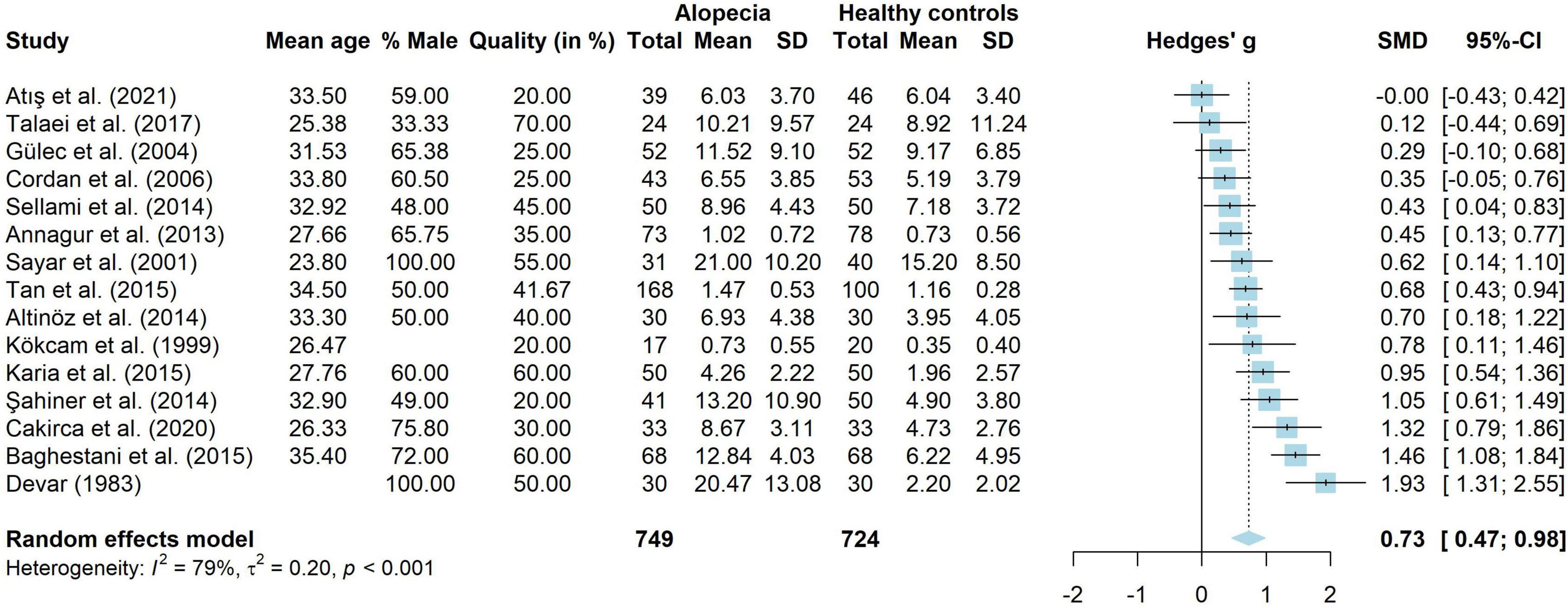

A total of 40 studies investigated QoL in people with AA. Five studies (36, 78, 83, 91, 92), combined children and adults into one sample (n = 3611, Mage = 31.43, 60.09% male), three studies (41, 43, 93) investigated children (n = 258, Mage = 11.50, 47.45% male) and 32 studies (17, 19–22, 53, 61, 62, 67, 73, 75, 76, 94–113) investigated adults with AA (n = 5,373, Mage = 41.38, 42.83% male).

Anxiety

The results for anxiety are shown in Table 1.

Children and adults

Three studies with a total of 5,665 patients with AA, reported that people with AA experienced more symptoms of anxiety and were diagnosed with anxiety more often than healthy controls (32–34). One smaller study (n = 24) (35) did not find a difference in the amount of symptoms of anxiety between people with AA and healthy controls.

When people with alopecia were compared to people with another (dermatological) condition, studies found that people with AA were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder more often than other hospitalized patients in general (34), but no differences were found for people with vitiligo (33).

One study without a control group (36) found that 19.1% of the adults with alopecia reported heightened symptoms of anxiety or depression. The same study also reported that 34.1% did not experience any symptoms of anxiety or depression. In the other study without a control group 89.0% of people with alopecia reported little to no symptoms of anxiety (38). Around 8% of people with AA reported moderate symptoms of anxiety.

Children

Of the papers investigating anxiety disorders, one study (46) reported that over half of the children had an anxiety disorder. However, this study included only 12 children and used the DSM-III-R, which was published in 1987. Two other studies reported that 7.1–16% had a generalized anxiety disorder, 7.1–8% had a separation anxiety disorder and 28.6% had a specific phobia (40, 44). However, none of the studies specified the number of patients with more than one anxiety disorder. It remains unclear from this data how many children with AA are diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. In a study by Altunisik et al. (39), 51.8% of the children was diagnosed with at least one anxiety disorder. This did not differ significantly from children with another dermatological condition.

When looking at symptoms of anxiety, studies comparing children with AA to healthy controls found mixed results. On the one hand, Bilgiç et al. (41) reported more state and trait anxiety in children aged 8–12 with AA. They did not find any differences for adolescents aged 12–18. On the other hand, Díaz-Atienza et al. (42) did not find significant differences when comparing children with AA to their siblings. Erdoğan et al. (43) found no difference on the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), but found more child-reported separation anxiety and total anxiety and parent-reported panic disorder and total anxiety than healthy controls on the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scales (RCADS).

Studies comparing children with AA to children with other (dermatological) conditions found no differences in symptoms of anxiety when comparing to other dermatological conditions (39), epilepsy (42) and vitiligo (43). Liakopoulou et al. (45) found that children scored higher on worry, oversensitivity, and concentration than other patients.

Adults

Eight papers studied the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adults with AA (n = 86,014). These studies reported point prevalence rates of 3.24% (64), 4% (17), 8.4% (71), and 13.70% (58). Several papers also reported that people with AA have a higher chance of being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder in comparison to healthy controls (13, 15, 17, 64). Prevalence rates of specific anxiety disorders in people with AA range from 7.4% for specific phobias and 22.2–39% for generalized anxiety disorders (57, 66). The lifetime prevalence of specific phobia and panic disorder was estimated at 23 and 13%, respectively (57).

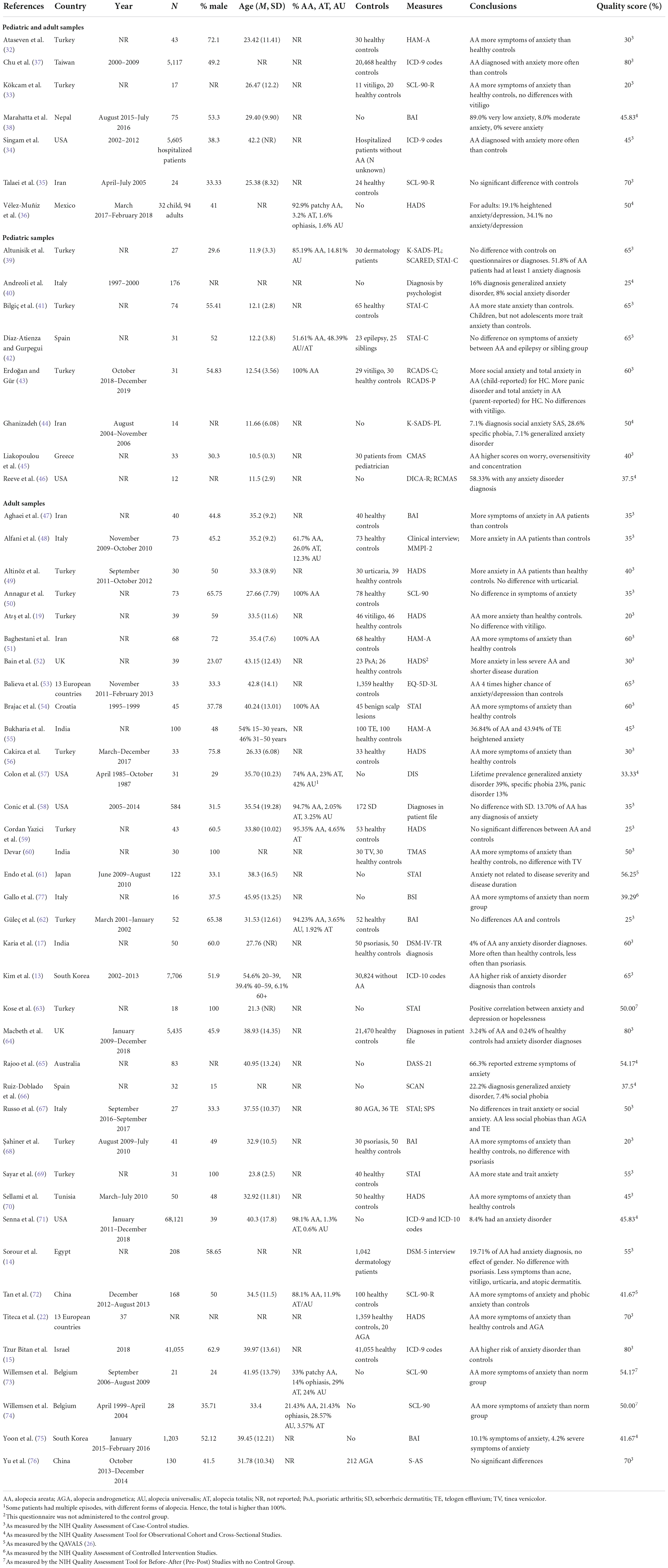

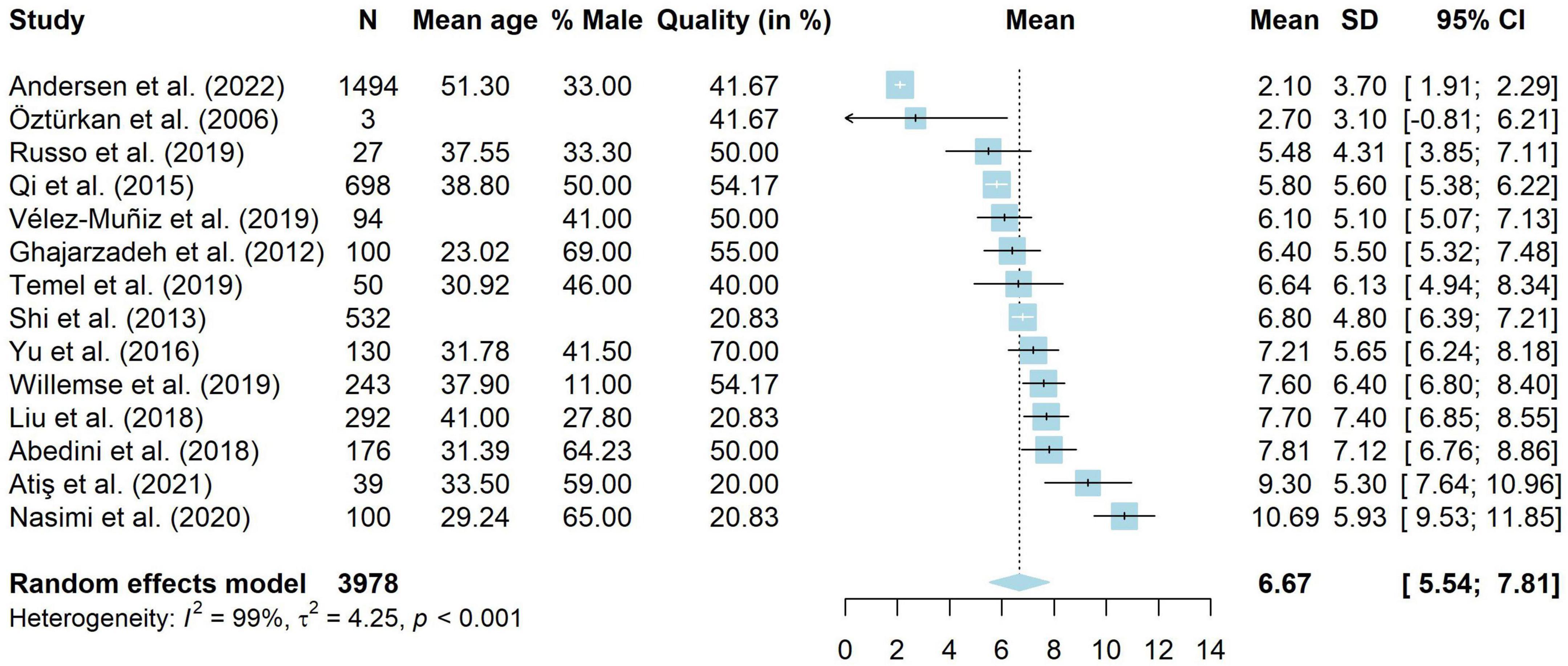

When looking at symptoms of anxiety, 15 studies compared people with AA (n = 749) to healthy controls (n = 733). These results were combined in a meta-analysis, shown in Figure 2. The results showed that adults with AA reported significantly more symptoms of anxiety than people without AA (g = 0.61, 95% CI [0.48, 0.75], p < 0.001), with a medium to large effect. There was little heterogeneity (I2 = 33.1%, 95% CI [<0.01, 64.0], τ2 = 0.02, 95% CI [<0.01, 0.12]) and visual inspection of the funnel plot showed no indication for publication bias. Egger’s test also did not show indications for a publication bias [t(13) = 0.94, p = 0.363]. Thirteen studies without missing data were included in a meta-regression. The model did not explain any variance in the effect sizes (R2 = <0.01%), with a residual heterogeneity of I2 = 46.59%. Mean age (g = 0.01, p = 0.802, 95% CI [−0.04 to 0.05]), percentage male (g = <−0.01, p = 0.858, 95% CI [−0.01 to 0.01]) and quality score (g = <0.01, p = 0.583, 95% CI [<−0.01 to 0.01]) did not influence study effect sizes.

Studies comparing people with AA to people with other (dermatological) conditions showed mixed results. For the majority of studies, no significant differences were found. For instance, no differences were found when comparing to people with chronic urticaria (49), vitiligo (19, 17), seborrheic dermatitis (58), tinea versicolor (60), alopecia androgenetica and telogen effluvium (67), and psoriasis (68, 14). A smaller number of studies reported that adults with AA experienced more symptoms of anxiety than patients with benign skin lesions (54) and alopecia androgenetica (22, 76), but less than people with psoriasis (17), acne, vitiligo, chronic urticaria, and atopic dermatitis (14).

Three studies compared adults with AA (n = 61) to a norm group. These studies all reported more symptoms of anxiety in adults with AA (73, 74, 77).

Depression

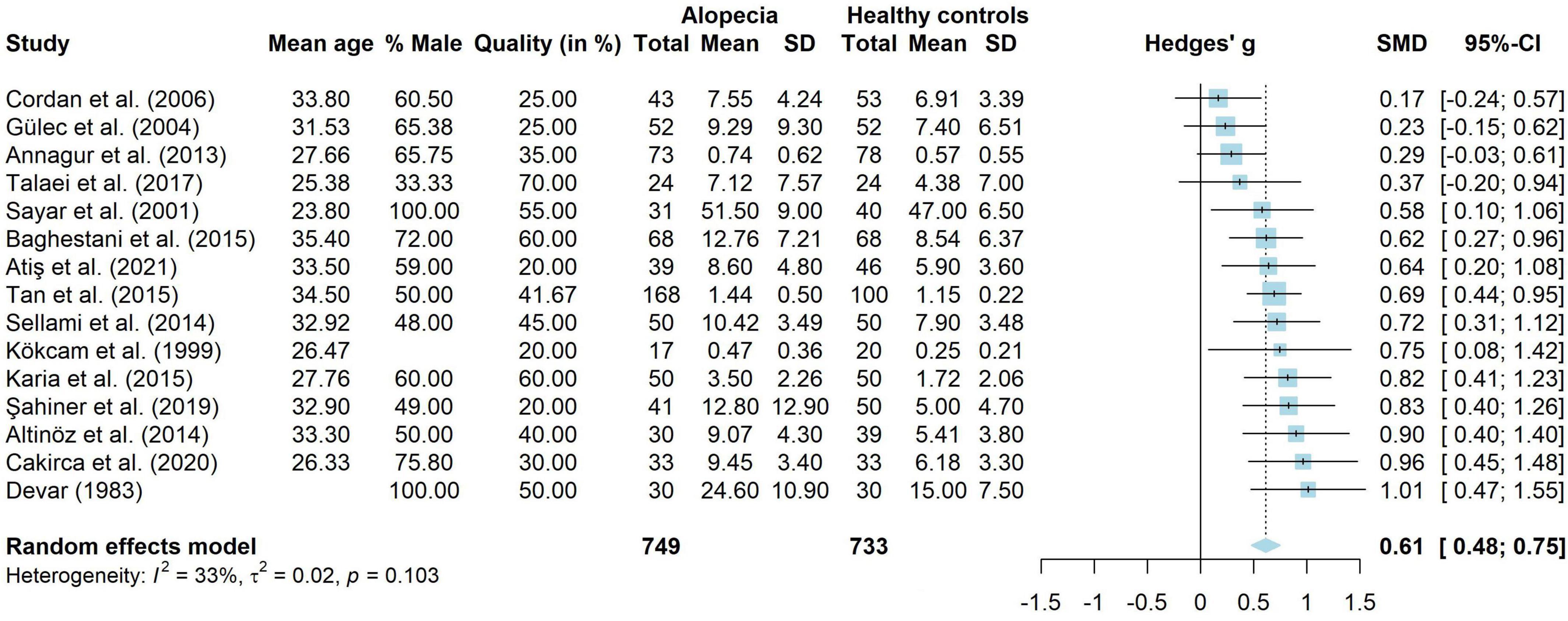

The results for depression are shown in Table 2.

Children and adults

In terms of diagnoses of depression, 4.3% of the visits to a psychologist by people with AA were related to depression (79). The point prevalence varied from 2.9% (37) to 3.98% (81). Different studies reported that people with AA were diagnosed with depressive disorders (37, 84) and mood disorders in general (34) significantly more often than healthy controls.

When looking at depressive symptoms, results concerning comparisons to healthy controls are mixed. Two studies, with a combined sample size of 60, reported more depressive symptoms in people with AA (32, 33), while one study did not find any significant differences (n = 24) (35).

Two studies compared people with AA to people with another (dermatological) condition. They did not find significant differences concerning the amount of depressive symptoms when comparing to people with psoriasis or vitiligo (78) or people with acne vulgaris, psoriasis or vitiligo (80).

Four studies (n = 657) did not use a control group. They found little to no depressive symptoms in 31.5% (82), 33.3% (38), and 34.1% (36) of people with AA. According to these studies around 60–65% of people with AA experience at least moderate depressive symptoms.

Children

Three studies (n = 3,700) investigated depressive disorders. A small study of 14 children found 50% of the children to be eligible for a diagnosis of depressive disorder (44). Bigger studies reported that 10% of the children were diagnosed with dysthymia (40) and that children with AA were diagnosed with a depressive disorder more often than other patients (85).

Three studies (n = 136) investigated symptoms of depression in comparison to healthy controls. Two studies found more depressive symptoms in children with AA (41, 43), while one study did not find a significant difference when comparing to unaffected siblings (42).

Four studies compared children with AA to children with a different (dermatological) condition. They did not find a difference in depressive symptoms when comparing children with AA to children with other dermatological conditions (39), epilepsy (42), vitiligo (43), and pediatric patients in general (45).

One study with 14 children with AA did not use a control group. This study did not find a heightened group average for depressive symptoms (46).

Adults

Several studies investigated the prevalence of depressive disorders in adults with AA. One study, conducted in the late 1990s, found a lifetime prevalence of 39% for depression and 16% for dysthymia (57). Estimates for point prevalence range from 7.4% (66), 9.5% (71), 18% (17), 21.74% (87) to 55.29% (14). The largest and most recent study found a point prevalence of 9.5% (71). Furthermore, adults with AA have a higher chance of being diagnosed with a depressive disorder than healthy controls (13, 15, 17, 64). One study did not find any difference in the number of diagnoses (58). There were no differences in the number of diagnoses when comparing to adults with psoriasis or vitiligo (17) or seborrheic dermatitis (58).

Fifteen studies compared adults with AA to healthy controls on the amount of depressive symptoms. These studies were analyzed in a meta-analysis. The results are shown in Figure 3. A total of 749 adults with AA and 724 healthy controls were analyzed. Adults with AA reported significantly more depressive symptoms than the control group (g = 0.73, 95% CI [0.47, 0.98], p < 0.001), with a medium to large effect. There was considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 78.5%, 95% CI [65.2, 86.8], τ2 = 0.20, 95% CI [0.08, 0.62]). Visual inspection of the funnel plot showed no signs of publication bias and Egger’s test was not significant [t(13) = 0.80, p = 0.438]. Thirteen studies without missing data were included in a meta-regression. The model explained very little variance in the effect sizes (R2 = 1.21%) and residual heterogeneity was high (I2 = 77.27%). Mean age (g = 0.04, p = 0.289, 95% CI [−0.03 to 0.12]), percentage male (g = 0.01, p = 0.168, 95% CI [−0.01 to 0.03]) and quality score (g = 0.01, p = 0.265, 95% CI [−0.01 to 0.03]) did not influence study effect sizes.

Figure 3. Forest plot for symptoms of depression in adults with alopecia compared to healthy controls.

Nine studies used a control group of adults with a different (dermatological) condition to assess the amount of depressive symptoms. The vast majority of the studies did not find any significant differences. For instance, no differences were found when comparing to chronic urticaria (49), vitiligo (19), telogen effluvium (55), tinea versicolor (60), atopic dermatitis (16), psoriasis (68), and alopecia androgenetica (22, 76). One study found that adults with AA reported less depressive symptoms than adults with acne vulgaris or psoriasis (16).

Studies without a control group found that people with AA (n = 183) reported more symptoms of depression than a norm group (61, 73, 74, 77). On average, they reported subclinical symptoms (63, 88). Estimates of the prevalence rates of people with depressive symptoms were 47.0% (65) and 40.9% (75).

Quality of life

The results for QoL are shown in Table 3.

Children and adults

People with AA reported worse QoL than people with psoriasis, but there was no difference with vitiligo (78). On average, people reported a small (36, 92) or moderate (36, 78, 83) impact on their QoL.

Children

Children with AA reported more impaired QoL than healthy controls (41, 43). In a study without a control group children with AA reported a small effect on their QoL (93).

Adults

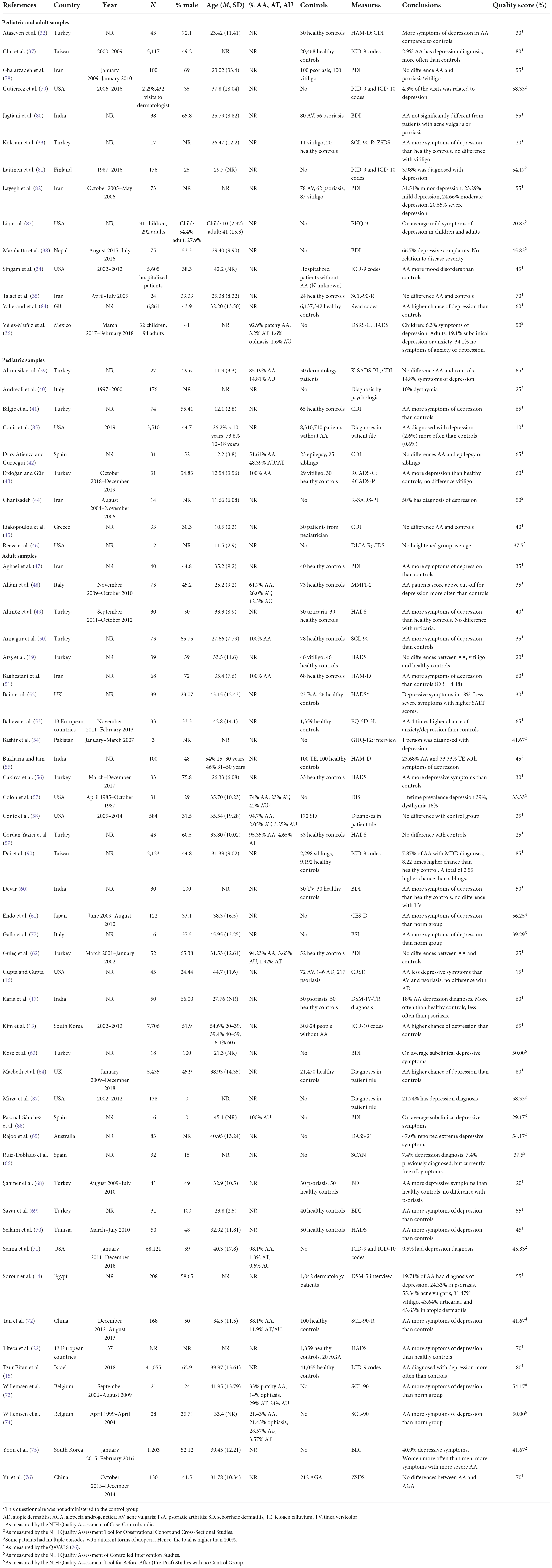

Fourteen studies used the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) to assess disease-specific QoL in 3,978 adults with AA (19, 20, 36, 67, 76, 78, 83, 94, 105, 107, 108, 112–114). These studies were included in a meta-analysis, shown in Figure 4. The total scores of the DLQI can be interpreted as follows: 0–1 = no effect on patient’s life, 2–5 = small effect, 6–10 = moderate effect, 11–20 = very large effect, 21–30 extremely large effect (115). Results from the meta-analysis showed that people with AA reported a weighted average of 6.67 (95% CI [5.54, 7.81]), which is a moderate effect. However, there was very high heterogeneity amongst studies (I2 = 98.9%, 95% CI [98.5, 99.0], τ2 = 4.25, 95% CI [2.07, 12.29], p < 0.001). Results should thus be interpreted with extreme caution. Meta-regressions were run on 11 studies without missing data. The model explained 62.89% of the variance in the data, but still included a substantial amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 89.56%). Mean age was negatively related to DLQI scores (g = −0.28, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.44 to −0.12]). Studies with a higher mean age had lower DLQI scores and thus less impaired QoL. The same was true for the quality ratings of studies (g = −0.08, p = 0.009, 95% CI [−0.13 to −0.02]), where studies with a lower quality rating reported higher DLQI levels. The percentage male (g = −0.04, p = 0.200, 95% CI [−0.11 to 0.02]) was not significantly related to DLQI scores.

As two studies did not provide clear data on their sample and may have included children (78, 114), we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess whether this influenced the results. Twelve studies (19, 20, 36, 67, 76, 83, 94, 105, 107, 108, 112, 113) with 3,346 people were included. The mean DLQI was unchanged (M = 6.68, 95% CI [5.33, 8.02]) and heterogeneity remained high (I2 = 98.8%, 95% [98.4, 99.0], τ2 = 5.14, 95% [2.38, 16.35]).

Five studies compared 188 adults with AA to healthy controls (53, 62, 96, 98, 104). There seemed to be no difference on physical functioning (53, 96, 104). However, adults with AA had more impaired mental (62, 96, 104) and overall (98) functioning.

Thirteen studies compared adults with AA to adults with another (dermatological) diagnosis (17, 20–22, 67, 76, 97, 101, 106, 109–112) and found very mixed results. On the one hand, no differences were found when comparing to adults with vitiligo (20, 112), alopecia androgenetica and telogen effluvium (67) and acne vulgaris (112). On the other hand, people with AA reported better QoL than people with psoriasis (101) or alopecia androgenetica (21). In yet other studies, people with AA reported worse QoL than people with alopecia androgenetica (22, 76).

Unknown samples

Two studies did not report whether they studied children or adults (114, 116). They found a moderate impact on QoL (114). When comparing to alopecia androgenetica, people with AA scored higher on subscales functioning and lower on symptoms (116). No differences were found for emotions and total score.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis we aimed to provide an overview of the current literature on anxiety, depression and QoL in people with AA. Results showed that people with AA experienced adverse psychosocial consequences in all three domains. Results also point to more diagnoses of anxiety and depression, as well as more symptoms of anxiety and depression, compared to healthy controls.

Meta-analytic results showed that people with AA experience more symptoms of anxiety and depression than healthy controls. With a medium to large effect for both meta-analyses, we can conclude that this constitutes a clinically relevant effect. Our results were unable to shed light on which patients are at risk for experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression as average age, percentage male and quality of the studies did not explain variance in the effect sizes. While the same studies were included in both meta-analyses, we found high heterogeneity for depression but not for anxiety. The range for effect sizes is much larger in depression than anxiety, however it is unclear where this originates from.

Meta-analytic results also showed that people with AA experience a moderate impact on their QoL. We were able to include around 3,800 patients in this meta-analysis, which makes it likely that our results generalize to other adults with AA. However, as we found very high heterogeneity, the moderate impact of AA on QoL is unlikely to be true for everyone with AA. Subgroups may exist based on variables that were not studied in the current meta-analysis, such as severity of disease, medication use, duration of disease or other variables.

Results concerning people with AA compared to people with other dermatological diagnoses were mixed for anxiety, depression, and QoL. However, the majority of the studies seems to point to people with AA experiencing the same amount of anxiety, depression, and impairment of QoL as people with other diagnoses. So, even though patients with AA do not experience physical symptoms that people with other dermatological diagnoses may experience, such as pain or itching (117), their QoL is comparable.

While we did not directly compare age groups, some observations can be noted. Firstly, for all three domains more studies were included for adults than for children. Hence, conclusions for adults can be made with more certainty. Both for anxiety and depression results of children with AA compared to healthy controls were mixed, while results for adults showed that adults with AA experienced more symptoms of anxiety and depression than healthy controls. As the mean age of the studies with children was 11.85, it is possible that symptoms of anxiety do not develop before puberty or adulthood, when appearance and peer relations become more important. This is corroborated by other studies showing more appearance-related distress in puberty (118). For QoL only three studies were found for children, so direct comparisons are hard to make.

Overall, our results are in line with a previous meta-analysis finding positive associations between AA and experiencing (symptoms of) anxiety or depression (12). In addition, we have shown that adults with AA experience more symptoms of anxiety and depression than healthy controls. Our results concerning QoL are also in line with Toussi et al. (23), who found diminished QoL in children and adults with AA. More specifically, we found diminished QoL in mental wellbeing but not necessarily in physical wellbeing. This is slightly unsurprising, as AA is associated with little physical impairment. Despite this, qualitative studies have shown that losing one’s hair has a considerable impact on mental health (7, 8).

It is also noteworthy that many studies included patients that were referred to a dermatologist. This could introduce a selection bias, where those who experience less psychological complaints are less likely to visit a dermatologist. However, large studies on primary care databases also reiterate that patients with alopecia are diagnosed with anxiety and depression more often than patients without alopecia (64, 84), with a diagnosis of depression preceding the diagnosis of AA for some patients (84).

This systematic review also has some strengths and limitations. A particular strength is the thorough literature search conducted. A formal search was created by a librarian, yielding 1,249 unique records. With this thorough search it is highly likely that no relevant articles were missed in the search process.

Despite the thorough literature search, we could only include a limited amount of studies in a quantitative analysis. For instance, we did not have enough data to disentangle psychological wellbeing in separate forms of AA (i.e., areata, universalis, or totalis) or how psychological wellbeing was related to disease severity or disease duration. Another limitation is that the included studies did not look at the remitting and relapsing course of AA specifically. Most studies were cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were often designed to look at a medical or psychological intervention. Qualitative research has highlighted that the unpredictable nature of AA can lead to feelings of anger or stress (119), but this has not been studied quantitatively. Hence, it remains unclear how the remitting and relapsing course of AA influences psychological wellbeing. A third limitation is that the included studies did not provide data on medication use. Inclusion criteria were often unclear when it came to participants’ medication use and medication use was often omitted from reporting in the outcome data. We do know that medical treatments often fail to provide sustained hair regrowth and may lead to substantial side effects (3). Hence, it remains unclear whether the pros of medication use outweigh the cons.

Another limitation is that the goal of the included studies did not always line up with the goal of the current systematic review. For instance, this review also included questionnaire validation studies (107) and baseline data of randomized controlled trials (88). The data was therefore approached in a different manner than the original authors intended. This may impede the strength of the current conclusions. However, as the intention of this review was to provide a thorough overview of the current literature, minimal limitations were set for the inclusion of different types of papers.

Based on these limitations, future studies should aim to study AA longitudinally and investigate the influence of disease severity, disease duration, disease status (inactive, remission, or relapse) and medication use on psychological wellbeing. These results would provide useful insights on potential at-risk groups in need of referral to psychological care.

The results of the current study highlight the impact of AA on psychological wellbeing. Clinicians treating people with AA should therefore be aware of the impact and refer to psychological care if needed. This could be accomplished through regular screening, for instance as part of value-based healthcare (120), or through the physician checking in on people’s mental health during outpatient clinic appointments.

Conclusion

In summary, we have shown that living with AA has important consequences for psychological wellbeing. People with AA experienced worse psychological outcomes than healthy controls and comparable psychological outcomes compared to people with other dermatological diagnoses. Important challenges lay ahead on how to treat AA, both psychologically as well as medically.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed as well as analysis scripts for this study can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/fxt7p/.

Author contributions

MD: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, visualization, and project administration. KM: formal analysis and writing—review and editing. JK-O, JO, and SP: writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the Dutch Alopecia Association (grant number n/a) with unrestricted funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elise Krabbendam from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing the search strategies.

Conflict of interest

Author JK-O is a board member of the Dutch Alopecia Association (volunteer position).

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.1054898/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, Torgerson RR. Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1 percent by rochester epidemiology project, 1990–2009. J Invest Dermatol. (2014) 134:1141. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.464

2. Harries M, Macbeth AE, Holmes S, Chiu WS, Gallardo WR, Nijher M, et al. The epidemiology of alopecia areata: a population-based cohort study in Uk primary care. Br J Dermatol. (2022) 186:257–65. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20628

3. Darwin E, Hirt PA, Fertig R, Doliner B, Delcanto G, Jimenez JJ. Alopecia areata: review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichol. (2018) 10:51–60. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_17

4. Tosti A, Bellavista S, Iorizzo M. Alopecia areata: a long term follow-up study of 191 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2006) 55:438–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.008

5. Lyakhovitsky A, Aronovich A, Gilboa S, Baum S, Barzilai A. Alopecia areata: a long-term follow-up study of 104 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2019) 33:1602–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15582

6. Harries MJ, Sun J, Paus R, King LE. Management of alopecia areata. BMJ. (2010) 341:c3671. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3671

7. Davey L, Clarke V, Jenkinson E. Living with alopecia areata: an online qualitative survey study. Br J Dermatol. (2019) 180:1377–89. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17463

8. Aldhouse NVJ, Kitchen H, Knight S, Macey J, Nunes FP, Dutronc Y, et al. “’You lose your hair, what’s the big deal?’ I was so embarrassed, i was so self-conscious, i was so depressed:” a qualitative interview study to understand the psychosocial burden of alopecia areata. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2020) 4:76. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00240-7

9. Zucchelli F, Sharratt N, Montgomery K, Chambers J. Men’s experiences of alopecia areata: a qualitative study. Health Psychol Open. (2022) 9:20551029221121524. doi: 10.1177/20551029221121524

10. Matzer F, Egger JW, Kopera D. Psychosocial Stress and coping in alopecia areata: a questionnaire survey and qualitative study among 45 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. (2011) 91:318–27. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1031

11. Wolf JJ, Hudson Baker P. Alopecia areata: factors that impact children and adolescents. J Adolesc Res. (2019) 34:282–301. doi: 10.1177/0743558418768248

12. Okhovat J-P, Marks DH, Manatis-Lornell A, Hagigeorges D, Locascio JJ, Senna MM. Association between alopecia areata, anxiety, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2019) S0190-9622:30890–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.086

13. Kim JC, Lee ES, Choi JW. Impact of alopecia areata on psychiatric disorders: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 82:484–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1304

14. Sorour F, Abdelmoaty A, Bahary MH, El Birqdar B. Psychiatric disorders associated with some chronic dermatologic diseases among a group of egyptian dermatology outpatient clinic attendants. J Egypt Women Dermatol Soc. (2017) 14:31–6. doi: 10.1097/01.EWX.0000503397.22746.bd

15. Tzur Bitan D, Berzin D, Kridin K, Cohen A. The association between alopecia areata and anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol Res. (2021) 314:463–8. doi: 10.1007/s00403-021-02247-6

16. Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (1998) 139:846–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x

17. Karia SB, De Sousa A, Shah N, Sonavane S, Bharati A. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in skin diseases: a comparison of alopecia areata and psoriasis. Ind Psychiatry J. (2015) 24:125–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.181724

18. Mostaghimi A, Napatalung L, Sikirica V, Winnette R, Xenakis J, Zwillich SH, et al. Patient perspectives of the social, emotional and functional impact of alopecia areata: a systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther. (2021) 11:867–83. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00512-0

19. Atış G, Tekin A, Ferhatoğlu ZA, Göktay F, Yaşar Ş, Aytekin S. Type D personality and quality of life in alopecia areata and vitiligo patients: a cross-sectional study in a turkish population. Turkderm Turk Arch Derm Venereol. (2021) 55:87–91. doi: 10.4274/turkderm.galenos.2020.36776

20. Andersen YMF, Nymand L, Delozier AM, Burge R, Edson-Heredia E, Egeberg A. Patient characteristics and disease burden of alopecia areata in the danish skin cohort. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e053137. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053137

21. Gonul M, Cemil BC, Ayvaz HH, Cankurtaran E, Ergin C, Gurel MS. Comparison of quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. (2018) 93:651–8. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186131

22. Titeca G, Goudetsidis L, Francq B, Sampogna F, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. ‘The psychosocial burden of alopecia areata and androgenetica’: a cross-sectional multicentre study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2020) 34:406–11. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15927

23. Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, Agbai ON, Kiuru M. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2021) 85:162–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.047

24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

25. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute [NIH]. Study Quality Assessment Tools. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (2021). Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed November 16, 2022).

26. Gore S, Goldberg A, Huang MH, Shoemaker M, Blackwood J. Development and validation of a quality appraisal tool for validity studies (Qavals). Physiother Theory Pract. (2021) 37:646–54. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2019.1636435

27. Viechtbauer W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J Educ Behav Stat. (2005) 30:261–93. doi: 10.3102/10769986030003261

28. Hedges LV. Distribution theory for glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat. (1981) 6:107–28. doi: 10.3102/10769986006002107

29. Shi J, Luo D, Weng H, Zeng XT, Lin L, Chu H, et al. Optimally estimating the sample standard deviation from the five-number summary. Res Synth Methods. (2020) 11:641–54. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1429

30. Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Contour-Enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J Clin Epidemiol. (2008) 61:991–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010

31. Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. (2019) 22:153–60. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

32. Ataseven A, Saral Y, Godekmerdan A. Serum cytokine levels and anxiety and depression rates in patients with alopecia areata. Eurasian J Med. (2011) 43:99–102. doi: 10.5152/eajm.2011.22

33. Kökcam I, Akyar N, Saral Y. Psychosomatic symptoms in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. Turk J Med Sci. (1999) 29:471–3. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12553

34. Singam V, Patel KR, Lee HH, Rastogi S, Silverberg JI. Association of alopecia areata with hospitalization for mental health disorders in Us adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2019) 80:792–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.044

35. Talaei A, Nahidi Y, Kardan G, Jarahi L, Aminzadeh B, Jahed Taherani H, et al. Temperament-character profile and psychopathologies in patients with alopecia areata. J Gen Psychol. (2017) 144:206–17. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2017.1304889

36. Vélez-Muñiz RDC, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Jurado-Santa Cruz F, Morales-Sánchez MA. Psychological profile and quality of life of patients with alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disord. (2019) 5:293–8. doi: 10.1159/000497166

37. Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Hwang CY, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata in taiwan: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. (2012) 166:525–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10714.x

38. Marahatta S, Agrawal S, Adhikari BR. Psychological impact of alopecia areata. Dermatol Res Pract. (2020) 2020:8879343. doi: 10.1155/2020/8879343

39. Altunisik N, Ucuz I, Turkmen D. Psychiatric basics of alopecia areata in pediatric patients: evaluation of emotion dysregulation, somatization, depression, and anxiety levels. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2022) 21:770–5. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14122

40. Andreoli E, Mozzetta A, Palermi G, Paradisi M, Foglio Bonda PG. Psychological diagnosis in pediatric dermatology. Dermatol Psychosom. (2002) 3:139–43. doi: 10.1159/000066585

41. Bilgiç Ö, Bilgiç A, Bahalç K, Bahali AG, Gürkan A, Yılmaz S. Psychiatric symptomatology and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2014) 28:1463–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12315

42. Díaz-Atienza F, Gurpegui M. Environmental stress but not subjective distress in children or adolescents with alopecia areata. J Psychosom Res. (2011) 71:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.01.007

43. Erdoğan SS, Gür TF. Anxiety and depression in pediatric patients with vitiligo and alopecia areata and their parents: a cross-sectional controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2021) 20:2232–9. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13807

44. Ghanizadeh A. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with alopecia areata in a child and adolescent psychiatry clinical sample. Int J Dermatol. (2008) 47:1118–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03743.x

45. Liakopoulou M, Alifieraki T, Katideniou A, Kakourou T, Tselalidou E, Tsiantis J, et al. Children with alopecia areata: psychiatric symptomatology and life events. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1997) 36:678–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00019

46. Reeve EA, Savage TA, Bernstein GA. Psychiatric diagnoses in children with alopecia areata. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1996) 35:1518–22. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00021

47. Aghaei S, Saki N, Daneshmand E, Kardeh B. Prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with alopecia areata in comparison with normal subjects. ISRN Dermatol. (2014) 2014:304370. doi: 10.1155/2014/304370

48. Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, Di Pietro C, Mazzanti C, Stella P, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. (2012) 92:304–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1239

49. Altınöz AE, Taşkıntuna N, Altınöz ŞT, Ceran S. A cohort study of the relationship between anger and chronic spontaneous urticaria. Adv Ther. (2014) 31:1000–7. doi: 10.1007/s12325-014-0152-6

50. Annagur BB, Bilgic O, Simsek KK, Guler O. Temperament-character profiles in patients with alopecia areata. Klin Psikofarmakol Bul. (2013) 23:326–34. doi: 10.5455/bcp.20130227031949

51. Baghestani S, Zare S, Seddigh SH. Severity of depression and anxiety in patients with alopecia areata in bandar abbas. Iran. Dermatol Rep. (2015) 7:36–8. doi: 10.4081/dr.2015.6063

52. Bain KA, McDonald E, Moffat F, Tutino M, Castelino M, Barton A, et al. Alopecia areata is characterized by dysregulation in systemic type 17 and type 2 cytokines, which may contribute to disease-associated psychological morbidity. Br J Dermatol. (2020) 182:130–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18008

53. Balieva F, Kupfer J, Lien L, Gieler U, Finlay AY, Tomás-Aragonés L, et al. The burden of common skin diseases assessed with the Eq5d™: a European multicentre study in 13 countries. Br J Dermatol. (2017) 176:1170–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15280

54. Brajac I, Tkalčić M, Dragojević DM, Gruber F. Roles of stress, stress perception and trait-anxiety in the onset and course of alopecia areata. J Dermatol. (2003) 30:871–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00341.x

55. Bukharia A, Jain N. Assessment of depression and anxiety in trichodynia patients of telogen effluvium and alopecia areata. Int J Med Res Health Sci. (2016) 5:61–6.

56. Cakirca G, Manav V, Celik H, Saracoglu G, Yetkin EN. Effects of anxiety and depression symptoms on oxidative stress in patients with alopecia areata. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. (2020) 37:412–6. doi: 10.5114/ada.2019.83879

57. Colon EA, Popkin MK, Callies AL, Dessert NJ, Hordinsky MK. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alopecia areata. Compr Psychiatry. (1991) 32:245–51. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90045-e

58. Conic RZ, Miller R, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Comorbidities in patients with alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2017) 76:755–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.007

59. Cordan Yazici A, Basterzi A, Tot Acar S, Ustunsoy D, Ikizoglu G, Demirseren D, et al. Alopecia areata and alexithymia. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. (2006) 17:101–6.

61. Endo Y, Miyachi Y, Arakawa A. Development of a disease-specific instrument to measure quality of life in patients with alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. (2012) 22:531–6. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1752

62. Güleç AT, Tanriverdi N, Dürü Ç, Saray Y, Akçali C. The role of psychological factors in alopecia areata and the impact of the disease on the quality of life. Int J Dermatol. (2004) 43:352–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02028.x

63. Kose O, Sayar K, Ebrinc S. Psychometric assessment of alopecia areata patients before and after dermatological treatment. Klinik Psikofarmakol Bülteni. (2000) 10:21–5.

64. Macbeth AE, Holmes S, Harries M, Chiu WS, Tziotzios C, de Lusignan S, et al. The associated burden of mental health conditions in alopecia areata: a population-based study in Uk primary care. Br J Dermatol. (2022) 187:73–81. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21055

65. Rajoo Y, Wong J, Cooper G, Raj IS, Castle DJ, Chong AH, et al. The relationship between physical activity levels and symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress in individuals with alopecia areata. BMC Psychol. (2019) 7:48. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0324-x

66. Ruiz-Doblado S, Carrizosa A, García-Hernández MJ. Alopecia areata: psychiatric comorbidity and adjustment to illness. Int J Dermatol. (2003) 42:434–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01340.x

67. Russo PM, Fino E, Mancini C, Mazzetti M, Starace M, Piraccini BM. Hrqol in Hair loss-affected patients with alopecia areata, androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium: the role of personality traits and psychosocial anxiety. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2019) 33:608–11. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15327

68. Şahiner IV, Taskintuna N, Sevik AE, Kose OK, Atas H, Sahiner S, et al. The impact role of childhood traumas and life events in patients with alopecia aerate and psoriasis. Afr J Psychiatry. (2014) 17:1–6. doi: 10.4172/Psychiatry.1000162

69. Sayar K, Köse O, Ebrinç S, Çetin M. Hopelessness, depression and alexithymia in young turkish soldiers suffering from alopecia areata. Dermatol Psychosom. (2001) 2:12–5. doi: 10.1159/000049631

70. Sellami R, Masmoudi J, Ouali U, Mnif L, Amouri M, Turki H, et al. The relationship between alopecia areata and alexithymia, anxiety and depression: a case-control study. Indian J Dermatol. (2014) 59:421. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135525

71. Senna M, Ko J, Tosti A, Edson-Heredia E, Fenske DC, Ellinwood AK, et al. Alopecia areata treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and comorbidities in the Us population using insurance claims. Adv Ther. (2021) 38:4646–58. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01845-0

72. Tan H, Lan XM, Yu NL, Yang XC. Reliability and validity assessment of the revised symptom checklist 90 for alopecia areata patients in China. J Dermatol. (2015) 42:975–80. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12976

73. Willemsen R, Haentjens P, Roseeuw D, Vanderlinden J. Hypnosis and alopecia areata: long-term beneficial effects on psychological well-being. Acta Derm Venereol. (2011) 91:35–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1012

74. Willemsen R, Vanderlinden J, Deconinck A, Roseeuw D. Hypnotherapeutic management of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2006) 55:233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.025

75. Yoon HS, Bae JM, Yeom SD, Sim WY, Lee WS, Kang H, et al. Factors affecting the psychosocial distress of patients with alopecia areata: a nationwide study in Korea. J Invest Dermatol. (2019) 139:712–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.024

76. Yu NL, Tan H, Song ZQ, Yang XC. Illness perception in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata in China. J Psychosom Res. (2016) 86:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.005

77. Gallo R, Chiorri C, Gasparini G, Signori A, Burroni A, Parodi A. Can mindfulness-based interventions improve the quality of life of patients with moderate/severe alopecia areata? A prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2017) 76:757–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.012

78. Ghajarzadeh M, Ghiasi M, Kheirkhah S. Associations between skin diseases and quality of life: a comparison of psoriasis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata. Acta Med Iran. (2012) 50:511–5.

79. Gutierrez Y, Pourali SP, Jones ME, Rajkumar JR, Kohn AH, Compoginis GS, et al. Alopecia areata in the United States: a ten-year analysis of patient characteristics, comorbidities, and treatment patterns. Dermatol Online J. (2021) 27:1–4. doi: 10.5070/d3271055631

80. Jagtiani A, Nishal P, Jangid P, Sethi S, Dayal S. Depression and suicidal ideation in patients with acne, psoriasis, and alopecia areata. J Ment Health Hum Behav. (2017) 139:846–50. doi: 10.4103/0971-8990.210700

81. Laitinen I, Jokelainen J, Tasanen K, Huilaja L. Comorbidities of alopecia areata in finland between 1987 and 2016. Acta Derm Venereol. (2020) 100:1–2. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3412

82. Layegh P, Arshadi HR, Shahriari S, Nahidi Y. A comparative study on the prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients suffering from psoriasis, acne, alopecia areata and vitiligo. Iran J Dermatol. (2010) 13:106–11.

83. Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Alopecia areata is associated with impaired health-related quality of life: a survey of affected adults and children and their families. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2018) 79:556.e–8.e. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.048

84. Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Parsons LM, Hardin J, Haber RM, Lowerison MW, et al. Assessment of a bidirectional association between major depressive disorder and alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. (2019) 155:475–9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4398

85. Conic RZ, Tamashunas NL, Damiani G, Fabbrocini G, Cantelli M, Bergfeld WF. Comorbidities in pediatric alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2020) 34:2898–901. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16727

86. Bashir K, Dar NR, Rao SU. Depression in adult dermatology outpatients. J Coll Phys Surg Pak. (2010) 20:811–3.

87. Mirza MA, Jung SJ, Sun W, Qureshi AA, Cho E. Association of depression and alopecia areata in women: a prospective study. J Dermatol. (2021) 48:1296–8. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15931

88. Pascual-Sánchez A, Fernández-Martín P, Saceda-Corralo D, Vañó-Galván S. Impact of psychological intervention in women with alopecia areata universalis: a pilot study. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. (2020) 111:694–6. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2019.12.013

89. Tzur Bitan D, Berzin D, Kridin K, Sela Y, Cohen A. Alopecia areata as a proximal risk factor for the development of comorbid depression: a population-based study. Acta Derm Venereol. (2022) 102:adv00669. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.1622

90. Dai YX, Tai YH, Chen CC, Chang YT, Chen TJ, Chen MH. Bidirectional association between alopecia areata and major depressive disorder among probands and unaffected siblings: a nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 82:1131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.064

91. Al-Mutairi N, Eldin ON. Clinical profile and impact on quality of life: seven years experience with patients of alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. (2011) 77:489–93. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.82411

92. Park J, Kim DW, Park SK, Yun SK, Kim HU. Role of hair prostheses (Wigs) in patients with severe alopecia areata. Ann Dermatol. (2018) 30:505–7. doi: 10.5021/ad.2018.30.4.505

93. Putterman E, Patel DP, Andrade G, Harfmann KL, Hogeling M, Cheng CE, et al. Severity of disease and quality of life in parents of children with alopecia areata, totalis, and universalis: a prospective, cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2019) 80:1389–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.051

94. Abedini R, Hallaji Z, Lajevardi V, Nasimi M, Karimi Khaledi M, Tohidinik HR. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Women Derm. (2018) 4:91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.07.001

95. Abideen F, Valappil AT, Mathew P, Sreenivasan A, Sridharan R. Quality of life in patients with alopecia areata attending dermatology department in a tertiary care centre – a cross-sectional study. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. (2018) 28:175–80.

96. de Hollanda TR, Sodre CT, Brasil MA, Ramos ESM. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a case-control study. Int J Trichol. (2014) 6:8–12. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.136748

97. Dubois M, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Richard MA, Loundou A, Auquier P, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a study of 60 cases. J Invest Dermatol. (2010) 130:2830–3. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.232

98. Essa N, Awad S, Nashaat M. Validation of an Egyptian arabic version of skindex-16 and quality of life measurement in egyptian patients with skin disease. Int J Behav Med. (2018) 25:243–51. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9677-9

99. Fayed HA, Elsaied MA, Faraj MR. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma in treatment of alopecia areata: a placebo-controlled study. J Egypt Women Dermatol Soc. (2018) 15:100–5. doi: 10.1097/01.EWX.0000540042.97989.cf

100. Han JJ, Li SJ, Joyce CJ, Burns LJ, Yekrang K, Senna MM, et al. Association of resilience and perceived stress in patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2021) 87:151–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.879

101. Jankovic S, Peric J, Maksimovic N, Cirkovic A, Marinkovic J, Jankovic J, et al. Quality of life in patients with alopecia areata: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2016) 30:840–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13520

102. Lai VWY, Chen G, Sinclair R. Impact of cyclosporin treatment on health-related quality of life of patients with alopecia areata. J Dermatol Treat. (2021) 32:250–7. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1654068

103. Liu LY, Craiglow BG, King BA. Successful treatment of moderate-to-severe alopecia areata improves health-related quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2018) 78:597.e–9.e. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.046

104. Masmoudi J, Sellami R, Ouali U, Mnif L, Feki I, Amouri M, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a sample of tunisian patients. Dermatol Res Pract. (2013) 2013:983804. doi: 10.1155/2013/983804

105. Nasimi M, Ghandi N, Torabzade L, Shakoei S. Alopecia areata-quality of life index questionnaire (reliability and validity of the persian version) in comparison to dermatology life quality index. Int J Trichol. (2020) 12:227–33. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_112_20

106. Nijsten T, Sampogna F, Abeni D. Categorization of skindex-29 scores using mixture analysis. Dermatology. (2009) 218:151–4. doi: 10.1159/000182253

107. Öztürkcan S, Ermertcan AT, Eser E, Turhan Şahin M. Cross validation of the turkish version of dermatology life quality index. Int J Dermatol. (2006) 45:1300–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02881.x

108. Qi S, Xu F, Sheng Y, Yang Q. Assessing quality of life in alopecia areata patients in China. Psychol Health Med. (2015) 20:97–102. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.894641

109. Reid EE, Haley AC, Borovicka JH, Rademaker A, West DP, Colavincenzo M, et al. Clinical severity does not reliably predict quality of life in women with alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, or androgenic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2012) 66:e97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.042

110. Sampogna F, Linder D, Piaserico S, Altomare G, Bortune M, Calzavara-Pinton P, et al. Quality of life assessment of patients with scalp dermatitis using the italian version of the scalpdex. Acta Derm Venereol. (2014) 94:411–4. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1731

111. Sanclemente G, Burgos C, Nova J, Hernández F, González C, Reyes MI, et al. The impact of skin diseases on quality of life: a multicenter study. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. (2017) 108:244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2016.11.019

112. Temel AB, Bozkurt S, Senol Y, Alpsoy E. Internalized stigma in patients with acne vulgaris, vitiligo, and alopecia areata. Turk Dermatoloji Derg. (2019) 13:109–16. doi: 10.4103/tjd.Tjd_14_19

113. Willemse H, van der Doef M, van Middendorp H. Applying the common sense model to predicting quality of life in alopecia areata: the role of illness perceptions and coping strategies. J Health Psychol. (2019) 24:1461–72. doi: 10.1177/1359105317752826

114. Shi Q, Duvic M, Osei JS, Hordinsky MK, Norris DA, Price VH, et al. Health-related quality of life (Hrqol) in alopecia areata patients—a secondary analysis of the national alopecia areata registry data. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. (2013) 16:S49–50. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.18

116. Jun M, Keum DI, Lee S, Kim BJ, Lee WS. Quality of life with alopecia areata versus androgenetic alopecia assessed using hair specific skindex-29. Ann Dermatol. (2018) 30:388–91. doi: 10.5021/ad.2018.30.3.388

117. Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak Ł. Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. (2019) 99:175–80.

118. van Dalen M, Dierckx B, Pasmans SGMA, Aendekerk EWC, Mathijssen IMJ, Koudstaal MJ, et al. Anxiety and depression in adolescents with a visible difference: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image. (2020) 33:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.006

119. Welsh N, Guy A. The lived experience of alopecia areata: a qualitative study. Body Image. (2009) 6:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.03.004

Keywords: alopecia, alopecia areata, psychosocial functioning, anxiety, depression, quality of life, meta-analysis

Citation: van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, Okkerse JME and Pasmans SGMA (2022) Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 9:1054898. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1054898

Received: 27 September 2022; Accepted: 11 November 2022;

Published: 29 November 2022.

Edited by:

Andrew Robert Thompson, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, United KingdomReviewed by:

Alina Constantin, British Association of Dermatologists, United KingdomAndrew Messenger, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 van Dalen, Muller, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo, Okkerse and Pasmans. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marije van Dalen, m.vandalen.1@erasmusmc.nl

Marije van Dalen

Marije van Dalen Kirsten S. Muller1

Kirsten S. Muller1