Status of Neutrino Properties and Future Prospects—Cosmological and Astrophysical Constraints

- 1The Oskar Klein Centre for Cosmoparticle Physics, Department of Physics, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

- 2Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy

Cosmological observations are a powerful probe of neutrino properties, and in particular of their mass. In this review, we first discuss the role of neutrinos in shaping the cosmological evolution at both the background and perturbation level, and describe their effects on cosmological observables such as the cosmic microwave background and the distribution of matter at large scale. We then present the state of the art concerning the constraints on neutrino masses from those observables, and also review the prospects for future experiments. We also briefly discuss the prospects for determining the neutrino hierarchy from cosmology, the complementarity with laboratory experiments, and the constraints on neutrino properties beyond their mass.

1. Introduction

Flavor oscillation experiments have by now firmly established that neutrinos have a mass. Current experiments measure with great accuracy the three mixing angles, as well as the two mass-squared splittings between the three active neutrinos. In the framework of the standard model (SM) of particle physics neutrinos are massless, and consequently do not mix, since it is not possible to build a mass term for them using the particle content of the SM. Therefore, flavor oscillations represent the only laboratory evidence for physics beyond the SM. Several unknowns in the neutrino sector still remain, confirming these particles as being the most elusive within the SM. In particular, the absolute scale of neutrino masses has yet to be determined. Moreover, the sign of the largest mass squared splitting, the one governing atmospheric transitions, is still unknown. This leaves open two possibilities for the neutrino mass ordering, corresponding to the two signs of the atmospheric splitting: the normal hierarchy, in which the atmospheric splitting is positive, and the inverted hierarchy, in which it is negative. Other unknowns are the value of a possible CP-violating phase in the neutrino mixing matrix, and the Dirac or Majorana nature of neutrinos.

There are different ways of measuring the absolute neutrino mass scale. One is to use kinematic effects, for example by measuring the energy spectrum of electrons produced in the β-decay of nuclei, looking for the distortions due to the finite neutrino mass. This approach has the advantage of being very robust and providing model-independent results, as it basically relies only on energy conservation. Present constraints on the effective mass of the electron neutrino mβ (an incoherent sum of the mass eigenvalues, weighted with the elements of the mixing matrix) are mβ < 2.05 eV from the Troitsk [1] experiment, and mβ < 2.3 eV from the Mainz [2] experiment, at the 95% CL. The KATRIN spectrometer [3], that will start its science run in 2018, is expected to improve the sensitivity by an order of magnitude. Another way to measure neutrino masses in the laboratory is to look for neutrinoless double β decay (0ν2β in short) of nuclei, a rare process that is allowed only if neutrinos are Majorana particles [4]. The prospects for detection of neutrino mass with 0ν2β searches are very promising: current constraints for the effective Majorana mass of the electron neutrino mββ, a coherent sum of the mass eigenvalues, weighted with the elements of the mixing matrix, are in the mββ < 0.1 ÷ 0.4 eV ballpark (see section 9 for more details). There are a few shortcomings, however. First of all, there is some amount of model dependence: one has to assume that neutrinos are Majorana particles to start, and even if this is, in some sense, a natural and very appealing scenario from the theoretical point of view—as it could explain the smallness of neutrino masses [5–9]—we have at the moment no indication that this is really the case. Moreover, inferring the neutrino mass from a (non-)observation of 0ν2β requires the implicit assumption that the mass mechanism is the only contribution to the amplitude of the process, i.e., that no other physics beyond the SM that violates lepton number is at play. Another issue is that the amplitude of the process also depends on nuclear matrix elements, that are known only with limited accuracy, introducing an additional layer of uncertainty in the interpretation of experimental results. Finally, given that mββ is a coherent superposition of the mass eigenvalues, it could be that the values of the Majorana phases arrange to make mββ vanishingly small.

The third avenue to measure neutrino masses, and in fact the topic of this review, is to use cosmological observations. As we shall discuss in more detail in the following, the presence of a cosmic background of relic neutrinos (CνB) is a robust prediction of the standard cosmological model [10]. Even though a direct detection is extremely difficult and still lacking, (but experiments aiming at this are currently under development, like the PTOLEMY experiment [11]), nevertheless cosmological observations are in agreement with this prediction. The relic neutrinos affect the cosmological evolution, both at the background and perturbation level, so that cosmological observables can be used to constrain the neutrino properties, and in particular their mass (see e.g., [10, 12, 13] for excellent reviews on this topic). In fact, cosmology currently represents the most sensitive probe of neutrino masses. The observations of cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies from the Planck satellite, without the addition of any external data, constrain the sum of neutrino masses already at the 0.6 eV level [14], which is basically the same as the KATRIN sensitivity. Combinations of different datasets yield even stronger limits, at the same level or better than the ones from 0ν2β searches, although a direct comparison is not immediate, due to the fact that different quantities are probed, and also due to the theoretical assumptions involved in the interpretation of both kinds of data. Future-generation experiments will likely have the capability to detect neutrino masses, and to disentangle the hierarchy, provided that systematics effects can be kept under control—and that our theoretical understanding of the Universe is correct, of course! Concerning this last point, the drawback of cosmological measurements of neutrino mass and other properties, is that they are somehow model dependent. Inferences from cosmological observations are made in the framework of a model—the so-called ΛCDM model—, and of its simple extensions, that currently represents our best and simple description of the Universe that is compatible with observations. This model is based on General Relativity (with the assumption of a homogeneous and isotropic Universe at large scales) and on the SM of particle physics, with the addition of massive neutrinos, complemented with a mechanism for the generation of primordial perturbations, i.e., the inflationary paradigm. When cosmological data are interpreted in this framework, they point to the following picture: our Universe is spatially flat and is presently composed by baryons (~5% of the total density), dark matter (~25%), and an even more elusive component called dark energy (~70%), that behaves like a cosmological constant, and is responsible for the present accelerated expansion, plus photons (a few parts in 105) and light neutrinos. The constraints from Planck cited above imply that, in the framework of the ΛCDM model, neutrinos can contribute 1% to the present energy density at most. The structures that we observe today have evolved from adiabatic, nearly scale-invariant initial conditions. Even though this model is very successful, barring some intriguing but for the moment still mild (at the ~2σ level) discrepancies between observational probes, this dependence should be borne in mind. On the other hand, such a healthy approach should not, in our opinion, be substituted with its contrary, i.e., a complete distrust toward cosmological constraints. A pragmatic approach to this problem is to test the robustness of our inferences concerning neutrino properties against different assumptions, by exploring extensions of the ΛCDM model. This has been in fact done quite extensively in the literature, and we will take care, toward the end of the review, to report results obtained in extended models.

Another advantage of cosmological observations is that they are able to probe neutrino properties beyond their mass. A well-known example is the effective number of neutrinos, basically a measure of the energy density in relativistic species in the early Universe, that is a powerful probe of a wide range of beyond the SM model physics (in fact, not necessarily related to neutrinos). For example, it could probe the existence of an additional, light sterile mass eigenstate, as well as the physics of neutrino decoupling, or the presence of lepton asymmetries generated in the early Universe. Cosmology can also be used to constrain the existence of non-standard neutrino interactions, possibly related to the mechanism of mass generation. Even though they are not the focus of this review, we will briefly touch some of these aspects in the final sections of the review.

Cosmological data have reached a very good level of maturity over the last decades. Measurements of the CMB anisotropies from the Planck satellite have put the tightest constraints ever on cosmological parameters from a single experiment [14], dramatically improving the constraints from the predecessor satellite WMAP [15]. From the ground, the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) polarization-sensitive receiver and the South Pole Telescope (SPT) have been measuring with incredible accuracy CMB anisotropies at the smallest scales in temperature and polarization [16, 17]. At degree and sub-degree scales, the BICEP/Keck collaboration [18, 19] and the POLARBEAR telescope [20] are looking at the faint CMB “B-mode” signal, containing information about both the early stages of the Universe (primordial B-modes) and the late time evolution (lensing B-modes). The Cosmology Large Angular Scale Surveyor (CLASS) [21] is working at mapping the CMB polarization field over 70% of the sky. The SPIDER balloon [22] successfully completed its first flight and is in preparation for the second launch likely at the end of 2018. In addition to CMB data, complementary information can be obtained by looking at the large-scale structure of the Universe. The SDSS III-BOSS galaxy survey has recently released its last season of data [23]. Extended catalogs of galaxy clusters have been completed from several surveys (see e.g., [24] and references therein). In addition, weak lensing surveys (Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Lensing Survey [25], Kilo-Degree Survey [26], Dark Energy Survey [27]) are mature enough to provide constraints on cosmological parameters that are competitive with those from other observables. They also allow to test the validity of the standard cosmological paradigm by comparing results obtained from high-redshift observables to those coming from measurements of the low-redshift universe.

The current scenario is just a taste of the constraining power of cosmological observables that will be available with the next generation of experiments, that will be taking measurements in the next decade. Future CMB missions—including Advanced ACTPol [28], SPT-3G [29], CMB Stage-IV [30], Simons Observatory1, Simons Array [31], CORE [32], LiteBIRD [33], PIXIE [34]—will test the Universe over a wide range of scales with unprecedented accuracy. The same accuracy will enable the reconstruction of the weak lensing signal from the CMB maps down to the smallest scales and with high sensitivity, providing an additional probe of the distribution and evolution of structures in the universe. On the other hand, the new generation of large-scale-structure surveys—including the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument [35], the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope [36], Euclid [37], and the Wide Frequency InfraRed Spectroscopic Telescope [38]—will also probe the late-time universe with the ultimate goal of shedding light on the biggest unknown of our times, namely the nature of dark energy and dark matter.

The aim of this review is to provide the state of the art of the current knowledge of neutrino masses from cosmological probes and give an overview of future prospects. The review is organized as follows: in section 2, we outline the framework of this review, introducing some useful notation and briefly reviewing the basics of neutrino cosmology. Section 3 is devoted to discussing, from a broad perspective, cosmological effects induced by massive neutrinos. In section 4, we will describe in detail how the effects introduced in section 3 affect cosmological observables, such as the CMB anisotropies, large-scale structures and cosmological distances. Sections 5 and 6 present a detailed collection of the current and future limits on Σmν from the measurements of the cosmological observables discussed in section 4, mostly derived in the context of the ΛCDM cosmological model. Constraints derived in more extended scenarios are summarized in section 7. Section 8 briefly deals with the issue of whether cosmological probes are able to provide information not only on Σmν, but also on its distribution among the mass eigenstates, i.e., about the neutrino hierarchy. In section 9, we will briefly go through the complementarity between cosmology and laboratory searches in the quest for constraining neutrino properties. Finally, section 10 offers a summary of the additional information about neutrino properties beyond their mass scale that we can extract from cosmological observables. We derive our conclusions in section 11. The impatient reader can access the summary of current and future limits from Tables 1–4.

2. Notation and Preliminaries

2.1. Basic Equations

Inferences from cosmological observations are made under the assumption that the Universe is homogeneous and isotropic, and as such it is well-described, in the context of general relativity, by a Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric. Small deviations from homogeneity and isotropy are modeled as perturbations over of a FLRW background.

In a FLRW Universe, expansion is described by the Friedmann equation2 for the Hubble parameter H:

where G is the gravitational constant, K parameterizes the spatial curvature3, a is the cosmic scale factor and the ρ is the total energy density. This is given by the sum of the energy densities of the various components of the cosmic fluid.

Considering cold dark matter (c), baryons (b), photons (γ), dark energy (DE), and massive neutrinos (ν), and introducing the redshift 1 + z = a−1, the Friedmann equation can be recast as:

where we have introduced the present value of the critical density required for flat spatial geometry (in general, we use a subscript 0 to denote quantities evaluated today), and the present-day density parameters Ωi = ρi,0/ρcrit,0 (since we will be always referring to the density parameters today, we omit the subscript 0 in this case). The scalings with (1 + z) come from the fact that the energy densities of non-relativistic matter and radiation scale with a−3 and a−4, respectively. For DE, in writing Equation (2) we have left open the possibility for an arbitrary (albeit constant) equation-of-state parameter w. In the case of neutrinos, since the parameter of their equation of state is not constant, we could not write a simple scaling with redshift, although this is possible in limiting regimes (see section 2.5). We use ρν,tot to denote the total neutrino density, i.e., summed over all mass eigenstates. Finally, we have defined a “curvature density parameter” . From Equation (2) evaluated at z = 0 it is clear that the density parameters, including curvature, satisfy the constrain .

Let us also introduce some extra notation and jargon that will be useful in the following. We will use Ωm to refer to the total density of non-relativistic matter today. Thus, this in general includes dark matter, baryons, and those neutrinos species that are heavy enough to be non-relativistic today. In such a way we have that Ωm + ΩDE = 1 in a flat Universe (or Ωm + ΩDE = 1 − Ωk in general), since the present density of photons and other relativistic species is negligible. Since many times we will have to consider the density of matter that is non-relativistic at all the redshifts that are probed by cosmological observables, i.e., dark matter and baryons but not neutrinos, we also introduce Ωc+b, with obvious meaning. When we consider dark energy in the form of a cosmological constant (w = −1) we use ΩΛ in place of ΩDE to make this fact clear. Finally, we also use the physical density parameters , with h being the present value of the Hubble parameter in units of 100 km s−1 Mpc−1.

As we shall discuss in more detail in the following, cosmological observables often carry the imprint of particular length scales, related to specific physical effects. For this reason we recall some definitions that will be useful in the following. The causal horizon rh at time t is defined as the distance traveled by a photon from the Big Bang (t = 0) until time t. This is given by:

Note that this is actually the comoving causal horizon; in the following, unless otherwise noted, we will always use comoving distances. We also note that the comoving horizon is equal to the conformal time η(t) (defined through dt = adη and η(t = 0) = 0). In a Friedmann Universe (i.e., one composed only by matter and radiation), the physical causal horizon is proportional, by a factor of order unity, to the Hubble length . For this reason, we shall sometimes indulge in the habit of calling the latter the Hubble horizon, even though this is, technically, a misnomer.

A related quantity is the sound horizon rs(t), i.e., the distance traveled in a certain time by an acoustic wave in the baryon-photon plasma. The expression for rs is very similar to the one for the causal horizon, just with the speed of light (equal to 1 in our units) replaced by the speed of sound cs in the plasma:

The speed of sound is given by , with R = (pb + ρb)/(pγ + ργ) being the baryon-to-photon momentum density ratio. When the baryon density is negligible relative to the photons, and .

Imprints on the cosmological observables of several physical processes usually depend on the value of those scales at some particular time. For example, the spacing of acoustic peaks in the CMB spectrum is reminiscent of the sound horizon at the time of hydrogen recombination; the suppression of small-scale matter fluctuations due to neutrino free-streaming is set by the causal horizon at the time neutrinos become non-relativistic; and so on. Moreover, since today we see those scales through their projection on the sky, what we observe is actually a combination of the scale itself and the distance to the object that we are observing. We find then useful also to recall some notions related to cosmological distances. The comoving distance χ between us and an object at redshift z is

and this is also equal to η0 − η(z). The comoving angular diameter distance dA(z) is given by

so that

The angular size θ of an object is related to its comoving linear size λ through θ = λ/dA(z). This justifies the definition of an object of known linear size as a standard ruler for cosmology. In fact, knowing λ, we can use a measure of θ to get dA and make inferences on the cosmological parameters that determine its value through the integral in Equation (6).

Another measure of distance is given by the luminosity distance dL(z), that relates the observed flux F to the intrinsic luminosity L of an object at redshift z:

Similarly to what happened for the angular diameter distance, this allows to use standard candles—objects of known intrinsic luminosity—as a mean to infer the values of cosmological parameters, after their flux has been measured.

2.2. Neutrino Mass Parameters

According to the standard theory of neutrino oscillations, the observed neutrino flavors να (α = e, μ, τ) are quantum superpositions of three mass eigenstates νi (i = 1, 2, 3):

where U is the Pontecorvo-Maki-Nakagawa-Sasaka (PMNS) mixing matrix. The PMNS matrix is parameterized by three mixing angles θ12, θ13, θ23, and three CP-violating phases: one Dirac, δ, and two Majorana phases, α21 and α31. The Majorana phases are non-zero only if neutrinos are Majorana particles. They do not affect oscillation phenomena, but enter lepton number-violating processes like 0ν2β decay. The actual form of the PMNS matrix is:

where cij ≡ cos θij and sij ≡ sin θij.

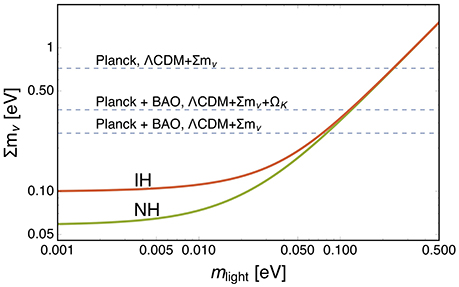

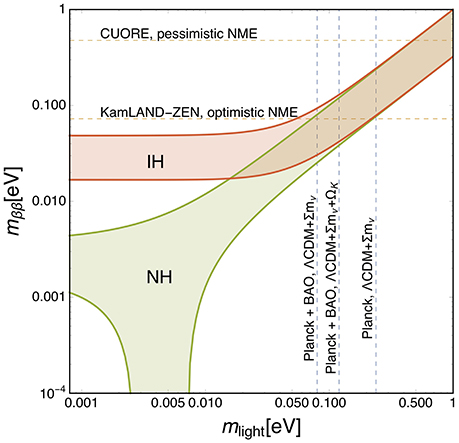

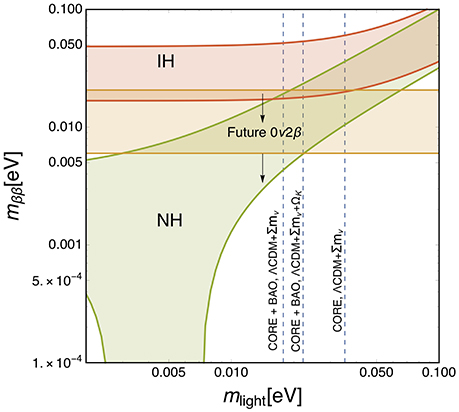

In addition to the elements of the mixing matrix, the other parameters of the neutrino sector are the mass eigenvalues mi (i = 1, 2, 3). Oscillation experiments have measured with unprecedented accuracy the three mixing angles and the two mass squared differences relevant for the solar and atmospheric transitions, namely the solar splitting , and the atmospheric splitting (see e.g., [39–41] for a global fit of the neutrino mixing parameters and mass splittings). We know, because of matter effects in the Sun, that, of the two eigenstates involved, the one with the smaller mass has the largest electron fraction. By convention, we identify this with eigenstate “1,” so that the solar splitting is positive. On the other hand, we do not know the sign of the atmospheric mass splitting, so this leaves open two possibilities: the normal hierarchy (NH), where and m1 < m2 < m3, or the inverted hierarchy, where and m3 < m1 < m2.

Oscillation experiments are unfortunately insensitive to the absolute scale of neutrino masses. In this review, we will mainly focus on cosmological observations as a probe of the absolute neutrino mass scale. To a very good approximation, cosmological observables are mainly sensitive to the sum of neutrino masses Σmν, defined simply as

Absolute neutrino masses can also be probed by laboratory experiments. These will be reviewed in more detail in section 9, where their complementarity with cosmology will be also discussed. For the moment, we just recall the definition of the mass parameters probed by laboratory experiments. The effective (electron) neutrino mass mβ

can be constrained by kinematic measurements like those exploiting the β decay of nuclei. The effective Majorana mass of the electron neutrino mββ:

can instead be probed by searching for 0ν2β decay.

2.3. The Standard Cosmological Model

Our best description of the Universe is currently provided by the spatially flat ΛCDM model with adiabatic, nearly scale-invariant initial conditions for scalar perturbations. With the exception of some mild (at the ~2σ level) discrepancies that will be discussed in the part devoted to observational limits, all the available data can be fit in this model, that in its simplest (“base”) version is described by just six parameters. In the base ΛCDM model, the Universe is spatially flat (Ωk = 0), and the matter and radiation content is provided by cold dark matter, baryons, photons, and neutrinos, while dark energy is in the form of a cosmological constant (w = −1). The energy density of photons is fixed by measurements of the CMB temperature, while neutrinos are assumed to be very light, usually fixing the sum of the masses to Σmν = 0.06 eV, the minimum value allowed by oscillation experiments. In this way, the energy density of neutrinos is also fixed at all stages of the cosmological evolution (see section 2.5). From Equation (2), and taking into account the flatness constraint, it is clear then that the background evolution in such a model is described by three parameters, for example4 h, ωc, and ωb, with ΩΛ given by 1 − Ωm. The initial scalar fluctuations are adiabatic and have a power-law, nearly scale invariant, spectrum, that is thus parameterized by two parameters, an amplitude As and a logarithimc slope ns − 1 (with ns = 1 thus corresponding to scale invariance). Finally, the optical depth to reionization τ parameterizes the ionization history of the Universe.

This simple, yet very successful, model can be extended in several ways. The extension that we will be most interested in, given the topic of this review, is a one-parameter extension in which the sum of neutrino masses is considered as a free parameter. We call this seven-parameter model ΛCDM + Σmν. This is also in some sense the best-motivated extension of ΛCDM, as we actually know from oscillation experiments that neutrinos have a mass, and from β-decay experiments that this can be as large as 2 eV. In addition to this minimal extension, we will also discuss how relaxing some of the assumptions of the ΛCDM model affects estimates of the neutrino mass. Among the possibilities that we will consider, there are those of varying the curvature (Ωk), the equation-of-state parameter of dark energy (w), or the density of radiation in the early Universe (Neff, defined in section 2.5).

There are many relevant extensions to the ΛCDM model that however we will not consider here (or just mention briefly). The most important one concerns the possibility of non-vanishing tensor perturbations, i.e., primordial gravitational waves, that, if detected, would provide a smoking gun for inflation. This scenario is parameterized through an additional parameter, the tensor-to-scalar ratio r. In the following, we will always assume r = 0. In any case, this assumption will not affect the estimates reported here, as the effect of finite neutrino mass and of tensor modes on the cosmological observables are quite distinct. Similarly, we will not consider the possibility of non-adiabatic initial perturbations, nor of more complicated initial spectra for the scalar perturbations, including those with a possible running of the scalar spectral index, although we report a compilation of relevant references in section 7 for the reader's convenience.

2.4. Short Thermal History

Given that cosmological observables carry the imprint of different epochs in the history of the Universe, we find it useful to shortly recall some relevant events taking place during the expansion history, and their relation to the cosmological parameters. For our purposes, it is enough to start when the temperature of the Universe was T ~ 1 MeV, i.e., around the time of Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) and neutrino decoupling. At these early times (z ~ 1010), since matter and radiation densities scale as (1 + z)3 and (1 + z)4, respectively, the Universe is radiation-dominated.

• At T ~ 1 MeV (z ~ 1010), the active neutrinos decouple from the rest of the cosmological plasma. Before this time, neutrinos were kept in equilibrium by weak interactions with electrons and positrons, that were in turn coupled electromagnetically to the photon bath. After this time, the neutrino mean free path becomes much larger the the Hubble length, so they essentially move along geodesics, i.e., they free-stream. Shortly after neutrino decouple, electrons and positrons in the Universe annihilate, heating the photon-electron-baryon plasma, and, to a much lesser extent, the neutrino themselves (in section 2.5 we shall discuss in more detail the neutrino thermal history). After this time, the Universe can essentially be thought as composed of photons, electrons, protons and neutrons (either free, or, after BBN, bound together into the light nuclei), neutrinos, dark matter, and dark energy.

• Soon after, at T ~ 0.1 MeV, primordial nucleosynthesis starts, and nuclear reactions bind nucleons into light nuclei. After this time, nearly all of the baryons in the Universe are in the form of 1H and 4He nuclei, with small traces of 2H and 7Li. The yields of light elements strongly depend on the density of baryons, on the density and energy spectrum of electron neutrinos and antineutrinos (as those set the equilibrium of the nuclear reactions) and on the total radiation density (as this sets the expansion rate at the time of nucleosynthesis).

• As said above, at early times (high z) the Universe is radiation-dominated, given that the radiation-to-matter density ratio like (1 + z). However, the radiation density decreases faster than that of matter, and, at some redshift zeq, the matter and radiation contents of the Universe will be equal: ρm(zeq) = ρr(zeq). This is called the epoch of matter-radiation equality, that marks the beginning of the matter-dominated era in the history of the Universe. From the scaling of the two densities, it is easy to see that 1 + zeq = Ωm/(Ωγ + Ων) in a Universe with massless neutrinos (so that their density always scale as (1 + z)4; see section 2.5 for further discussion on this point). Given the current estimates of cosmological parameters, zeq ≃ 3, 400 [14].

• At T ≃ 0.3 eV, electrons and nuclei combine to form neutral hydrogen and helium, that are transparent to radiation. This recombination epoch thus roughly corresponds to the time of decoupling of radiation from matter. This is the time at which the CMB radiation is emitted. After decoupling, the CMB photons undergo last interactions with residual free electrons. Finally, the CMB photons emerge from this last scattering surface and free-stream until the present time (with some caveats, see below). Most of the features that we observe in the CMB anisotropy pattern are created at this time. Given the current estimates of cosmological parameters, zrec ≃ 1, 090 [14]. Note that in fact the temperature at recombination is basically fixed by thermodynamics, so once the present CMB temperature is determined through observations, zrec = T(z = zrec)/T(z = 0) depends very weakly on the other cosmological parameters.

• Even if photons decoupled from matter shortly after recombination, the large photon-to-baryon ratio keeps baryons coupled to the photon bath for some time after that. The drag epoch zdrag is the time at which baryons stop feeling the photon drag. A good fit to numerical results in a CDM cosmology is given by Eisenstein and Hu [42]

Given the current estimates of cosmological parameters, zdrag ≃ 1,060 [14].

• For a long time after recombination, the Universe stays transparent to radiation. These are the so-called “dark ages.” However, in the late history of the Universe, the neutral hydrogen gets ionized again due to UV emission of the first stars, that puts an end to the dark ages. This is called the reionization epoch. After reionization, the CMB photons are scattered again by the free electrons. Given the current estimates of cosmological parameters, zre ≃ 8 [43].

• At some point during the recent history of the Universe, that we denote with zΛ, the energy content of the Universe starts to be dominated by the dark energy component. The end of matter domination, and the beginning of this DE domination is set by ρDE(zΛ) = ρm(zΛ). For a cosmological constant (w = −1), . Given the current estimates of cosmological parameters, zΛ ≃ 0.3 [14]. Around this time, the cosmological expansion becomes accelerated.

2.5. Evolution of Cosmic Neutrinos

In this section, we discuss the thermal history of cosmic neutrinos.

As anticipated above, in the early Universe neutrinos are kept in equilibrium with the cosmological plasma by weak interactions. The two competing factors that determine if equilibrium holds are the expansion rate, given by the Hubble parameter H(z), and the interaction rate Γ(z) = n〈σv〉, where n is the number density of particles, σ is the interaction cross section, and v is the velocity of particles (brackets indicate a thermal average). In fact, neutrino interactions become too weak to keep them in equilibrium once Γ < H. The left-hand side of this inequality is set by the standard model of particle physics, as the interaction rate at a given temperature only depends on the cross-section for weak interactions, and thus, ultimately, on the value of the Fermi constant (). The right-hand side is instead set through Equation (2) by the total radiation density (the only relevant component at such early times): . In the framework of the minimal ΛCDM model, once the present CMB temperature is measured, the radiation density at any given temperature is fixed. Thus the temperature of neutrino decoupling, defined through Γ(Tν,dec) = H(Tν,dec) does not depend on any free parameter in the theory. A quite straightforward calculation shows that Tν,dec ≃ 1 MeV [44].

While they are in equilibrium, the phase-space distribution f(p) of neutrinos is a Fermi-Dirac distribution5:

where it has been taken into account that at T ≳ 1 MeV, the active neutrinos are certainly ultrarelativistic (i.e., Tν ≫ mν) and thus E(p) ≃ p. The distribution does not depend on the spatial coordinate , nor on the direction of momentum , due to the homogeneity and isotropy of the Universe. Before decoupling, the neutrino temperature Tν is the common temperature of all the species in the cosmological plasma, that we denote generically with T, so that Tν = T. We recall that the temperature of the plasma evolves according to , where g∗s counts the effective number of relativistic degrees of freedom that are relevant for entropy [44].

Since decoupling happens while neutrinos are ultrarelativistic, it can be shown that, as a consequence of the Liouville theorem, the shape of the distribution function is preserved by the expansion. In other words, the distribution function still has the form Equation (15), with an effective temperature Tν(z) (that for the sake of simplicity we will continue to refer to as the neutrino temperature) that scales like a−1 (i.e., aT = const). We stress that this means that, when computing integrals over the distribution function, one still neglects the mass term in the exponential of the Fermi-Dirac function, even at times when neutrinos are actually non-relativistic.

Shortly after neutrino decouple, electrons and positrons annihilate and transfer their entropy to the rest of the plasma, but not to neutrinos. In other words, while the neutrino temperature scales like a−1, the photon temperature scales like , and thus decreases slightly more slowly during e+e− annihilation, when g∗s is decreasing. In fact, applying entropy conservation one finds that the ratio between the neutrino and photon temperatures after electron-positron annihilation is . The photon temperature has been precisely determined by measuring the frequency spectrum of the CMB radiation: T0 = (2.725 ± 0.002) K [45, 46], so that the present temperature of relic neutrinos should be Tν,0 ≃ 1.95 K ≃ 1.68 × 10−4 eV.

The number density nν of a single neutrino species (including both neutrinos and their antiparticles) is thus given by:

where ζ(3) is the Riemann zeta function of 3, and in the last equality we have taken into account that g = 2 for neutrinos. This corresponds to a present-day density of roughly 113 particles/cm3.

The energy density of a single neutrino species is instead

This is the quantity that appears, among other things, in the right-hand side of the Friedmann equation (summed over all mass eigenstates). In the ultrarelativistic (Tν ≫ m) and non-relativistic (Tν ≪ m) limits, the energy density takes simple analytic forms:

These scalings are consistent with the fact that one expects neutrinos to behave as pressureless matter, , in the non-relativistic regime, and as radiation, , in the ultrarelativistic regime.

Given that the present-day neutrino temperature is fixed by measurements of the CMB temperature and by considerations of entropy conservation, it is clear from the above formulas how the present energy density of neutrinos depends only on one free parameter, namely the sum of neutrino masses Σmν defined in Equation (11). Introducing the total density parameter of massive neutrinos , one easily finds from Equation (16):

where we have already included the effects of non-instantaneous neutrino decoupling, see below. In the instantaneous decoupling approximation, the quantity at denominator would be 94.2 eV.

On the other hand, the neutrino energy density in the early Universe only depends on the neutrino temperature, and thus it is completely fixed in the framework of the ΛCDM model. Using the fact that for photons , together with the relationship between the photon and neutrino temperatures, one can write for the total density in relativistic species in the early Universe, after e+e− annihilation:

where Nν is the number of neutrino families. In the framework of the standard model of particle physics, considering the active neutrinos, one has Nν = 3. However, the above formula slightly underestimates the total density at early times; the main reason is that neutrinos are still weakly coupled to the plasma when e+e− annihilation occurs, so that they share a small part of the entropy transfer. Moreover, finite temperature QED radiative corrections and flavor oscillations also play a role. This introduces non-thermal distortions at the subpercent level in the neutrino energy spectrum; the integrated effect is that at early times the combined energy densities of the three neutrino species are not exactly equal to 3ρν, with ρν given by the upper row of Equation (18), but instead are given by (3.046ρν) [12, 47]. A recent improved calculation, including the full collision integrals for both the diagonal and off-diagonal elements of the neutrino density matrix, has refined this value to (3.045ρν) [48]. It is then customary to introduce an effective number of neutrino families Neff and rewrite the energy density at early times as:

In this review, we will consider Neff = 3.046 as the “standard” value of this parameter in the ΛCDM model, and not the more precise value found in de Salas and Pastor [48], since most of the literature still makes use of the former value. This does not make any difference, however, from the practical point of view, given the sensitivity of present and next-generation instruments.

It is also customary to consider extensions of the minimal ΛCDM model in which one allows for the presence of additional light species in the early Universe (“dark radiation”). In this kind of extension, the total radiation density of the Universe is still given by the right-hand side of Equation (21), where now however Neff has become a free parameter. In other words, Equation (21) becomes a definition for Neff, that is, just a way to express the total energy density in radiation. The effect on the expansion history of this additional radiation component can be taken into account by the substitution

in the rhs of the Hubble equation (2), with ΔNeff ≡ Neff − 3.046. Note that this substitution fully captures the effect of the additional species only if this is exactly massless, and not just very light (as in the case of a light massive sterile neutrino, for example—see section 10).

It is often useful, to understand some of the effects that we will discuss in the following, to have a feeling for the time at which neutrinos of a given mass become non-relativistic, or, thinking the other way around, for the mass of a neutrino that becomes non-relativistic at a given redshift. The average momentum of neutrinos at a temperature Tν is 〈p〉 = 3.15Tν. We take as the moment of transition from the relativistic to the non-relativistic regime the time when 〈p〉 = mν. Then, using the fact that , one has

This relation can be used to show e.g., that neutrinos with mass mν ≲ 0.6 eV turn non-relativistic around or after recombination. In the following, when discussing the effect of neutrino masses on the CMB anisotropies, we will assume that this is the case. Note however that the actual statistical analyses from which bounds on neutrino masses are derived do not make such an assumption. We also note that, given the current measurements of the neutrino mass differences, only the lightest mass eigenstate can still be relativistic today. Thus at least two out of the three active neutrinos become non-relativistic before the present time.

We conclude this section with a clarification on the role of neutrinos in determining the redshift of matter-radiation equality. Given the present bounds on neutrino masses, we know that equality likely takes place when neutrino are relativistic. In fact, observations of the CMB anisotropies constrain zeq ≃ 3,400, so that neutrinos with mass mν ≃ 1.8 eV, just below the current bound from tritium beta-decay, turn non-relativistic at equality. Thus, for masses sufficiently below the tritium bound, the total density of matter at those times is proportional to Ωc+b. The radiation density is instead provided by photons and by the relativistic neutrinos (and as such does not depend on the neutrino mass), plus any other light species present in the early Universe. So the redshift of equivalence is given by

where the last equality makes it clear that, in the framework of the minimal ΛCDM model, the redshift of equivalence only depends on the quantity ωc+ωb, since Neff is fixed and ωγ is determined through observations (it is basically the CMB energy density).

3. Cosmological Effects of Neutrino Masses

The impact of neutrino masses—and in general of neutrino properties—on the cosmological evolution can be divided in two broad categories: background effects, and perturbation effects. The former class refers to modifications in the expansion history, i.e., in changes to the evolution of the FLRW background. The latter class refers instead to modifications in the evolution of perturbations in the gravitational potentials and in the different components of the cosmological fluid. We shall now briefly review both classes; we refer the reader who is interested in a more detailed analysis to the excellent review by Lesgourgues and Pastor [13].

To start, we shall consider a spatially flat Universe, i.e., Ωk = 0, in which dark energy is in the form of a cosmological constant (w = −1) and there are no extra radiation components (Neff = 3.046). Let us also consider a particular realization of this scenario, that we refer to as our reference model, in which the sum of neutrino masses is very small; for definiteness, we can think that Σmν is equal to the minimum value allowed by oscillation measurements, Σmν = 0.06 eV (see section 8 for further details). When needed, we will take the other parameters as fixed to their ΛCDM best-fit values from Planck 2015 [14]. Our aim is to understand what happens when we change the value of Σmν. Increasing the sum of neutrino masses Σmν will increase according to Equation (19). Remember that the sum of the density parameters ; this constraint can be recast in the form:

Since ωγ is constrained by observations, and ωk is zero by assumption, we have four degrees of freedom that we can use to compensate for the change in ων, namely: increase h, or decrease any of ωc, ωb, or ωΛ. For the moment, for simplicity, we will not distinguish between baryons and cold dark matter, pretending that as non-relativistic components they have the same effect on cosmological observables. This is of course not the case, but we will come back to this later. Then we are left with three independent degrees of freedom that we can use to compensate for the change in ων: h, ωb+c, and ωΛ. We prefer to use ΩΛ in place of ωΛ, so that in the end our parameter basis for this discussion will be {h, ωc+b, ΩΛ}.

The first option, increasing the present value of the Hubble constant while keeping ΩΛ and ωb+c constant has the effect of making the Hubble parameter at any given redshift after neutrinos become non-relativistic larger with respect to the reference model. This can be understood by looking at Equation (2), that we rewrite here in this particular case

With respect to the reference model, the first two terms in the RHS are unchanged, while the third increases because ΩΛ is fixed but h is larger. The last term does not depend on h (because the factor in front of the square brackets cancel the one in the critical density) but yet increases because ρν = Σmνnν is larger as long as neutrinos are in the non-relativistic regime. On the other hand, before neutrino become non-relativistic, ρν is the same in the two models, and the change in the term is irrelevant, because the DE density is only important at very low redshifts. So we can conclude that at z ≫ znr, the two models share the same expansion history, while for z ≲ znr the model with “large” neutrino mass is always expanding faster (larger H), or equivalently, is always younger, at those redshifts. In terms of the length scales and of the distance measures introduced in section 2.1, it is easily seen that the causal and sound horizons at both equality and recombination (as well as at the drag epoch) are unchanged, because the expansion history between z = ∞ and z ≃ znr is unchanged. On the other hand, distances between us and objects at any redshift—for example, the angular diameter distance to recombination—are always smaller than in the reference model, because H is always larger between z ≃ znr and z = 0. H increases with the extra neutrino density, so this effect increases with larger neutrino masses (and moreover, znr also gets larger for larger masses). Given this, we expect for example the angle subtended by the sound horizon at recombination, θs = rs(zrec)/dA(zrec) to become larger when we increase Σmν. We conclude this part of the discussion that in this case the redshift of equality zeq does not change, since ωb+c is being kept constant, and neutrinos contribute to the radiation density at early times (see discussion at the end of the previous section).

If we instead choose to pursue the second option, i.e., we keep h and ΩΛ constant while lowering ωc+b, we are again changing the expansion history, but this time on a different range of redshifts. In fact, when neutrinos are non-relativistic, the RHS of Equation (26) is unchanged, because the changes in the present-day densities of neutrinos and non-relativistic matter perfectly compensate; this continues to hold as long as both densities scale as (1 + z)3, i.e., roughly for z < znr. On the other hand, at z > znr the neutrino density is the same as in the reference model, while the matter density is smaller, so H(z) is smaller as well. Finally, when the Universe is radiation dominated, the two models share again the same expansion history. Then in this scenario we change the expansion history, decreasing H, for znr ≲ z ≲ zeq. The sound horizon at recombination increases, and so does the angular diameter distance, so one cannot immediately guess how their ratio varies. However, a direct numerical calculation shows that, starting from the Planck best-fit model, the net effect is to increase θs, meaning that the sound horizon will subtend a larger angular scale on the sky when Σmν increases. For what concerns instead the redshift of matter-radiation equality, it is immediate to see that it decreases proportionally to ωc+b, i.e., equality happens later in the model with larger Σmν.

Finally, when ΩΛ is decreased, the main effect is to delay the onset of acceleration and make the matter-dominated era last longer. This has some effect on the evolution of perturbations, as we shall see in the following. For what concerns the expansion history, since the model under consideration and the reference model only differ in the neutrino mass and in the DE density, they are identical when neutrinos are relativistic and DE is negligible, i.e., at z > znr. For z < znr, instead, starting as usual from Equation (26) one finds, with some little algebra, that H(z) is always larger in the model with smaller ΩΛ and larger Σmν. As in the previous case, both rs and dA at recombination vary in the same direction (decreasing in this case); the net effect is again that θs becomes larger with Σmν. Also, since the matter density at early times is not changing in this case, the redshift of equivalence is the same in the two models.

We now comment briefly about ωb. One could choose to modify ωb in place of ωc in order to compensate for the change in ων. From the point of view of the background expansion, both choices are equivalent, since the baryon and cold dark matter density only enter through their sum ωb+c in the RHS of Equation (26). However, changing the baryon density also produces some peculiar effects, mainly related to the fact that (i) it determines the BBN yields, and (ii) it affects the evolution of photon perturbations prior to recombination. Thus, the density of baryons is quite well constrained by the observed abundances of light elements and by the relative ratio between the heights of odd and even peaks in the CMB, (see section 4.1) and there is little room for changing it without spoiling the agreement with observations.

Let us now turn to discuss the effects on the evolution of perturbations. Given that we have observational access to the fluctuations in the radiation and matter fields, it is useful to discuss separately these two components. The photon perturbations are sensitive to time variations in the gravitational potentials along the line of sight from us up to the last-scattering surface; this is the so-called integrated Sachs-Wolfe (ISW) effect. The gravitational potentials are constant in a purely matter-dominated Universe, so that the observed ISW gets an early contribution right after recombination, when the radiation component is not yet negligible, and a late contribution, when the dark energy density begins to be important. Coming back to our previous discussion, it is clear to see how delaying the time of equality will increase the amount of early ISW, while anticipating dark energy domination will increase the late ISW, and viceversa. For what concerns matter inhomogeneities, a first effect is again related to the time of matter-radiation equality. Changing zeq affects the growth of perturbations, since most of the growth happens during the matter dominated era. Apart from that, a very peculiar effect is related to the clustering properties of neutrinos. In fact, while neutrinos are relativistic, they tend to free stream out of overdense regions, damping out all perturbations below the horizon scale. The net effect is that neutrino clustering is suppressed below a certain critical scale, the free-streaming scale, that corresponds to the size of the horizon at the time of the nonrelativistic transition. If the transition happens during matter domination, this is given by:

On the contrary, above the free-streaming scale neutrinos cluster as dark matter and baryons do. Thus, increasing the neutrino mass and consequently the neutrino energy density will suppress small-scale matter fluctuations relative to the large scales. It will also make small-scale perturbations in the other components grow slower, since neutrino do not source the gravitational potentials at those scales. It should also be noted that the free-streaming scale depends itself on the neutrino mass—specifically, heavier neutrinos will become non-relativistic earlier and the free-streaming scale will be correspondingly smaller. Moreover, there is actually a free-streaming scale for each neutrino species, each depending on the individual neutrino mass. In principle one could think to go beyond observing just the small-scale suppression and try to access instead the scales around the non-relativistic transition(s), in order to get more leverage on the mass and perhaps also on the mass splitting. We shall see however in the following that this is not the case.

The suppression of matter fluctuations due to neutrino free-streaming also affects the path of photons coming from distant sources, since those photons will be deflected by the gravitational potentials along the line of sight, resulting in a gravitational lensing effect. This is relevant for the CMB, as it modifies the anisotropy pattern by mixing photons that come from different directions. Another application of this effect, of particular importance for estimates of neutrino masses, is to use the distortions of the shape of distant galaxies due to lensing, to reconstruct the intervening matter distribution.

4. Cosmological Observables

In this section we review the various cosmological observables, and explain how the effects described in the previous section propagate to the observables.

4.1. CMB Anisotropies

The CMB consists of polarized photons that, for the most part, have been free-streaming from the time of recombination to the present time. The pattern of anisotropies in both temperature (i.e., intensity) and polarization thus encodes a wealth of information about the early Universe, down to z = zrec ≃ 1, 100. Moreover, given that the propagation of photons from decoupling to the present time is also affected by the cosmic environment, the CMB also has some sensitivity to physics at z < zrec. Two relevant examples for the topic under consideration are the CMB sensitivity to the redshift of reionization (because the CMB photons are re-scattered by the new population of free electrons) and to the integrated matter distribution along the line of sight (because clustering at low redshifts modifies the geodesics with respect to an unperturbed FLRW Universe, resulting in a gravitational lensing of the CMB, see next section). However, the CMB sensitivity to these processes is limited due to the fact that these are integrated effects.

The information in the CMB anisotropies is encoded in the power spectrum coefficients , i.e., the coefficients of the expansion in Legendre polynomials of the two-point correlation function. In the case of the temperature angular fluctuations :

For Gaussian fluctuations, all the information contained in the anisotropies can be compressed without loss in the two-point function, or equivalently in its harmonic counterpart, the power spectrum. A similar expression holds for the polarization field and for its cross-correlation with temperature. In detail, the polarization field can be decomposed into two independent components, known as E− (parity-even and curl-free) and B− (parity-odd and divergence-free) modes. Given that, it is clear that we can build a total of six spectra with X, Y = T, E, B; however, if parity is not violated in the early Universe, the TB and EB correlations are bound to vanish. Let us also recall that, in linear perturbation theory, B modes are not sourced by scalar fluctuations. Thus, in the framework of the standard inflationary paradigm, primordial B modes can only be sourced in the presence of tensor modes, i.e., gravitational waves.

The shape of the observed power spectra is the result of the processes taking place in the primordial plasma around the time of recombination. In brief, in the early Universe, standing, temporally coherent acoustic waves set in the coupled baryon-photon fluid, as a result of the opposite action of gravity and radiation pressure [49]. Once the photons decouple after hydrogen recombination, the waves are “frozen” and thus we observe a series of peaks and throughs in the temperature power spectrum, corresponding to oscillation modes that were caught at an extreme of compression or rarefaction (the peaks), or exactly in phase with the background (the throughs). The typical scale of the oscillations is set by the sound horizon at recombination rs(zrec), i.e., the distance traveled by an acoustic wave from some very early time until recombination, see Equation (4). The position of the first peak in the CMB spectrum is set by the value of this quantity and corresponds to a perturbation wavenumber that had exactly the time to fully compress once. The second peak corresponds to the mode with half the wavelength, that had exactly the time to go through one full cycle of compression and rarefaction, and so on. Thus, smaller scales (larger multipoles) than the first peak correspond to scales that could go beyond one full compression, while larger scales (smaller multipoles) did not have the time to do so. In fact, scales much above the sound horizon are effectively frozen to their initial conditions, provided by inflation. This picture is complicated a little bit by the presence of baryons, that shift the zero of the oscillations, introducing an asymmetry between even and odd peaks. Finally, the peak structure is further modulated by an exponential suppression, due to the Silk damping of photon perturbations (further related to the fact that the tight coupling approximation breaks down at very small scales). This description also holds for polarization pertubations, with some differences, like the fact that the polarization perturbations have opposite phase with respect to temperature perturbations.

As noted above, the large-scale temperature fluctuations, that have entered the horizon very late and did not have time to evolve, trace the power spectrum of primordial fluctuations, supposedly generated during inflation. On the contrary, since there are no primordial polarization fluctuations, but those are instead generated at the time of recombination and then again at the time of reionization, the polarization spectra at large scales are expected to vanish, with the exception of the so-called reionization peak.

We can now understand how the CMB power spectra are shaped by the cosmological parameters, in a minimal model with fixed neutrino mass. The overall amplitude and slope of the spectra are determined by As and ns, since these set the initial conditions for the evolution of perturbations. The height of the first peak strongly depends on the redshift of equivalence zeq (that sets the enhancement in power due to the early ISW), while its position is determined by the angle θs subtended by the sound horizon at recombination. As we have discussed before, zeq and θs are in turn set by the values of the background densities and of the Hubble constant. The baryon density further affects the relative heights of odd and even peaks, and also the amount of damping at small scales, through its effect on the Silk scale. The ratio of the densities of matter and dark energy fixes the redshift of dark energy domination and the amount of enhancement of large-scale power due to the late ISW. Finally, the optical depth at reionization τ induces an overall power suppression, proportional to e−2τ, in all spectra, at all but the largest scales. This can be easily understood as the effect of the new scatterings effectively destroying the information about the fluctuation pattern at recombination, at the scales that are inside the horizon at reionization. Reionization also generates the large-scale peak in the polarization spectra, described above. Measuring the power spectra gives a precise determination of all these parameters: simplifying a little bit, the overall amplitude and slope give and ns (the latter especially if we can measure a large range of scales), the ratio of the peak heights and the amount of small-scale damping fix ωb, while the position and height of the first peak fix θs and zeq, and thus h and ωb+c. The polarization spectra further help in that they are sensitive to τ directly, allowing to break the As − τ degeneracy, and that the peaks in polarization are sharper and thus allow, in principle, for a better determination of their position [50]. It is clear that adding one more degree of freedom to this picture, for example considering curvature, the equation of state parameter of dark energy, or the neutrino mass as a free parameter, will introduce parameter degeneracies and degrade the constraints.

Coming to massive neutrinos, as we have discussed in section 3, there is a combination of the following effects when Σmν, and consequently ων, is increased, depending on how we are changing the other parameters to keep : (i) an increase in θs; (ii) a smaller zeq and thus a longer radiation-dominated era; (iii) a delay of the time of dark energy domination. These changes will in turn result in: (i) a shift towards the left of the position of the peaks; (ii) an increased height of the first peak, that is set by the amount of early ISW; (iii) less power at the largest scales, due to the smaller amount of late ISW. A more quantitative assessment of these effects can be obtained using a Boltzmann code, like CAMB [51] or CLASS [52], to get a theoretical prediction for the CMB power spectra in presence of massive neutrinos. These are shown in Figure 1. In the left panel we plot the unlensed CMB temperature power spectra for a reference model with Σmν = 0.06 eV () (the other parameters are fixed to their best-fit values from Planck 2015) and for three models with Σmν = 1.8 eV (), where either h, ωc, or ΩΛ are changed to keep . We consider three degenerate neutrinos with mν = 0.6 eV each, so that they become non-relativistic around recombination. We also show the ratio between these spectra and the reference spectrum in the right panel of the same figure.

Figure 1. (Top) CMB TT power spectra for different values of Σmν. The quantity on the vertical axis is . The red curve is a cosmological model with Σmν = 0.06 eV and all other parameters fixed to the Planck best-fit. The other curves are for models with Σmν = 1.8 eV, in which the curvature is kept vanishing by changing h (green), ΩΛ (yellow, always below the green apart from the lowest ℓ's), or ωc (blue). The model in blue has a smaller zeq with respect to the reference; the models in yellow and green have a larger θs; in addition, the yellow model also has a smaller zΛ. (Bottom) Ratio between the models with Σmν = 1.8 eV and the reference model.

These imprints are in principle detectable in the CMB, especially the first two, since the position and height of the first peak are very well measured; much less so the redshift of DE domination, due to the large cosmic variance at small ℓ's. However, following the above discussion, it is quite easy to convince oneself that these effects can be pretty much canceled due to parameter degeneracies. In fact, simplifying again a little bit, in standard ΛCDM we use the very precise determinations of the height and position of the first peak to determine θs and zeq, and from them ωc+b and h. In an extension with massive neutrinos, we still have the same determination of θs and zeq, but we have to use them to fix three parameters, namely ωc+b, h, and ων, so that the system is underdetermined. One could argue that the amount of late ISW, as measured by the large-scale power, could be used to break this degeneracy, as it would provide a further constraint on the matter density (given that the DE density is fixed by the flatness condition). Unfortunately, measurements of the large-scale CMB power are plagued by large uncertainties, due to cosmic variance, so they are of little help in solving this degeneracy. Given the experimental uncertainties, then, it is clear that, when trying to fit a theory to the data, there will be a strong degeneracy direction corresponding to models having the same θs and zeq, and thus with identical predictions for the first peak, and slightly different values of zΛ, with very low statistical weight due to the large uncertainties in the corresponding region of the spectrum. In other words, the effects of neutrino masses will be effectively “buried” in the small-ℓ plateau, where experimental uncertainties are large. The situation is even worse in extended models, for example if we allow the spatial curvature or the equation of state of dark energy to vary [13]. In any case, the degeneracy between h and ωc+b is not completely exact, so that the unlensed CMB still has some degree of sensitivity to neutrinos that were relativistic at recombination. For example, the Planck 2013 temperature data, in combination with high-resolution observations from ACT and SPT, were able to constrain Σmν < 1.1 eV after marginalizing over the effects of lensing [53].

4.1.1. Secondary Anisotropies and the CMB Lensing

As observed above, in addition to the features that are generated at recombination, the so-called primary anisotropies, the CMB spectra also carry the imprint of effects that are generated along the line of sight. We have already given an example of one of these secondary anisotropies when we have mentioned the re-scattering of photons over free electrons at low redshift, that creates the distinctive “reionization bump” in the low-ℓ region of the polarization spectra. Another important secondary anisotropy is the gravitational lensing of the CMB (see [54, 55]): photon paths are distorted by the presence of matter inhomogeneities along the line of sight. In the context of General Relativity, the deflection angle α for a CMB photon is

where χ* is the comoving distance to the last scattering surface, fK(χ) is the angular-diameter distance (Equation 6) thought as a function of the comoving distance, Ψ is the gravitational potential, η0 − χ is the conformal time at which the photon was along the direction n. If we then define the lensing potential as

it is straightforward to see that the deflection angle is the gradient of the lensing potential, α = ∇ϕ. From the harmonic expansion of the lensing potential, we can build an angular power spectrum6 as . The lensing power spectrum is therefore proportional to the integral along the line of sight of the power spectrum of the gravitational potential PΨ, which in turn can be expressed in terms of the power spectrum of matter fluctuations Pm (see the next section for its definition).

The net effect of lensing on the CMB is that photons coming from different directions are mixed, somehow “blurring” the anisotropy pattern. This effect is mainly sourced by inhomogeneities at z < 5 and has a typical angular scale of 2.5′. In the power spectra, this translates in a several percent level smoothing of the primary peak structure (ℓ ≳ 1,000), while the lensing effect becomes dominant at ℓ ≳ 3,000. We stress that lensing only alters the spatial distribution of CMB fluctuations, while leaving the total variance unchanged. Lensing, being a non-linear effect, creates some amount of non-gaussianity in the anisotropy pattern. Thus, other than through its indirect effect on the temperature and polarization power spectra (i.e., on the two-point correlation functions), lensing can be detected and measured by looking at higher-order correlations, in particular at the four-point correlation function. In fact, in such a way it has been possible to directly measure the power spectrum of the lensing potential ϕ. Another consequence of the non-linear nature of lensing is that it is able to source “spurious” B modes by converting some of the power in E polarization, thus effectively creating B polarization also in the absence of a primordial component of this kind. The latter effect represents an additional tool to enable the reconstruction of the lensing potential, especially for future CMB surveys. An alternative reconstruction technique is based on the possibility to cross-correlate the CMB signal with tracers of large-scale structures, such as Cosmic Infrared Background (CIB) maps, therefore leading to an “external” reconstruction [56] (opposite to the “internal” reconstruction performed with the use of CMB-based only estimators [57, 58]).

The lensing power spectrum basically carries information about the integrated distribution of matter along the line of sight. Given the peculiar effect of neutrino free-streaming on the evolution of matter fluctuations, CMB lensing offers an important handle for estimates of neutrino masses. Since a larger neutrino mass implies a larger neutrino density and less clustering on small scales, because of neutrino free-streaming, the overall effect of larger neutrino masses is to decrease lensing. In the temperature and polarization power spectra, the result is that the peaks and throughs at high ℓ's are sharper. Concerning the shape of the lensing power spectrum, for light massive neutrinos the net effect is a rescaling of power at intermediate and small scales (see e.g., [59]). Thus, the lensing power spectrum is a powerful tool for constraining Σmν and will probably drive even better constraints on Σmν in the future. In fact, it is almost free from systematics coming from poorly understood astrophysical effects, it directly probes the (integral over the line of sight of the) distribution of the total matter fluctuations (as opposed to what galaxy surveys do, as we will see in the next section) at scales that are still in the linear regime.

Given a cosmological model, it is quite straightforward, using again CAMB or CLASS, to get a theoretical prediction for the lensing power spectrum, as well as for the lensing BB power spectrum. Note that non-linear corrections (see next section for further details) to the lensing potential are important in this case to get accurate large-scale BB spectrum coefficients [54]. Additional corrections that take into account modifications to the CMB photon emission angle due to lensing can further modify the large-scale lensing BB spectrum [60].

4.2. Large Scale Structures

4.2.1. Clustering

The clustering of matter at large scales is another powerful probe of cosmology. The clustering can be described in terms of the two-point correlation function, or, equivalently, of the power spectrum of matter density fluctuations:

where is the Fourier transform of the matter density perturbation at redshift z. Note that, contrarily to the CMB, that we are bound to observe at a single redshift (that of recombination), the matter power spectrum can, in principle, be measured at different times in the cosmic history, thus allowing for a tomographic analysis.

As for the CMB, the large-scale (small k's) part of the power spectrum traces the primordial fluctuations generated during inflation, while smaller scales reflect the processing taking place after a given perturbation wavenumber enters the horizon. A relevant distinction in this regard is whether a given mode enters the horizon before or after matter-radiation equality. Since subhorizon perturbations grow faster during matter domination, the matter power spectrum shows a turning point at a characteristic scale, corresponding to the horizon at zeq. Given that perturbations grow less efficiently also during DE domination, increasing zΛ produces a suppression in the power spectrum. Also, increasing h will make the horizon at a given redshift smaller; so the mode k that is entering the horizon at that redshift will be larger.

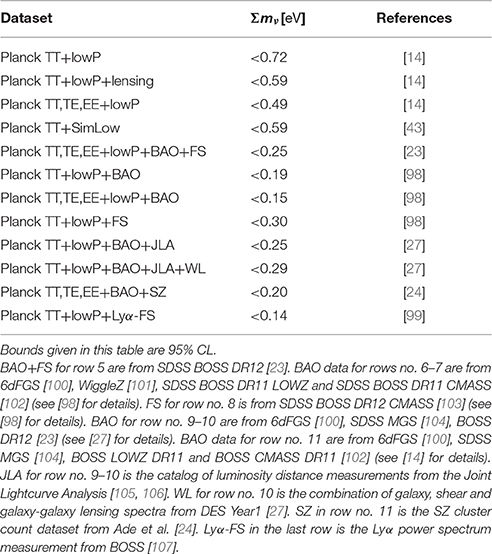

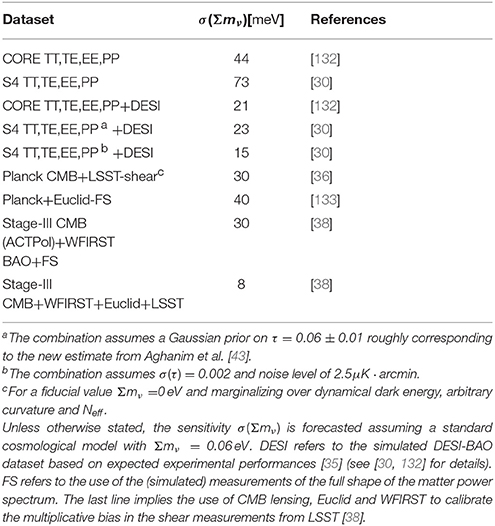

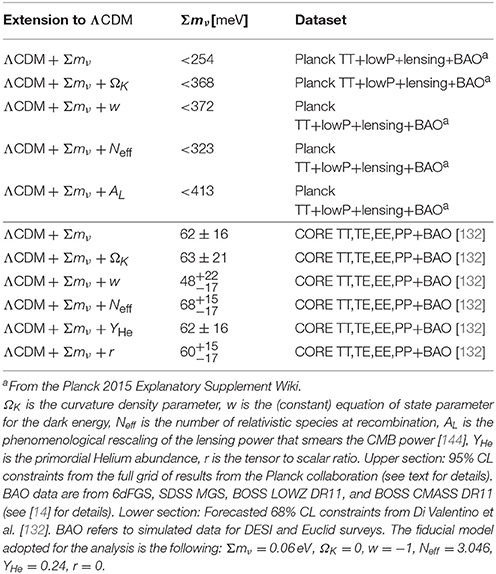

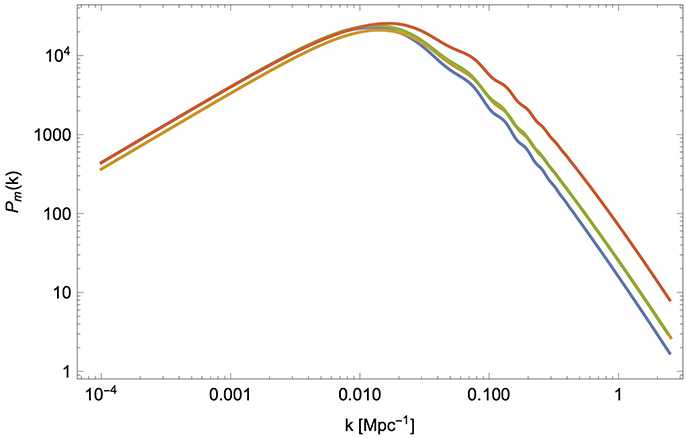

Varying the sum of neutrino masses has some indirect effects on the shape of matter power spectrum, related to induced changes in background quantities, similarly to what happens for the CMB. As explained in section 3, increasing Σmν while keeping the Universe flat has to be compensated by changing (a combination of) ωm, ΩΛ, or h. This will in turn result in a shift of the turning point and/or in a change in the global normalization of the spectrum. This can be seen in Figure 2, where we show the matter power spectra for the same models considered when discussing the background effects of neutrino masses on the CMB.

Figure 2. Total matter power spectrum Pm for the same models shown in Figure 1.

As it is for the CMB, these effects can be partly canceled due to parameter degeneracies. Neutrinos, however, have also a peculiar effect on the evolution of matter perturbations. This is due to the fact that neutrinos possess large thermal velocities for a considerable part of the cosmic history, so they can free-stream out of overdense regions, effectively canceling perturbations on small scales. In particular, one can define the free-streaming length at time t as the distance that neutrinos can travel from decoupling until t. The comoving free-streaming length reaches a maximum at the time of the non-relativistic transition. This corresponds to a critical wavenumber kfs, given in equation (27) for transitions happening during matter-domination, above which perturbations in the neutrino component are erased.

A first consequence of neutrino free-streaming is that, below the free-streaming scale, there is a smaller amount of matter that can cluster. This results in an overall suppression of the power spectrum at small scales, with respect to the neutrinoless case. Secondly, subhorizon perturbations in the non-relativistic (i.e., cold dark matter and baryons) components grow more slowly. In fact, while in a perfectly matter-dominated Universe, the gravitational potential is constant and the matter perturbation grows linearly with the scale factor, δm ∝ a, in a mixed matter-radiation Universe the gravitational potential decays slowly inside the horizon. Below the free-streaming scale, neutrinos effectively behave as radiation; then in the limit in which the neutrino fraction fν = Ων/Ωm is small, one has for k ≫ kfs

while δm ∝ a for k ≪ kfs. These two effects can be qualitatively understood as follows: if one considers a volume with linear size well below the free-streaming scale, this region will resemble a Universe with a smaller Ωm and a larger radiation-to-matter fraction than the “actual” (i.e., averaged over a very large volume) values. This yields a smaller overall normalization of the spectrum, as well as a larger radiation damping; the two effects combine to damp the matter perturbations inside the region. So, looking again at the full power spectrum, the net effect is that, in the presence of free-streaming neutrinos, power at small-scales is suppressed with respect to the case of no neutrinos. At z = 0, the effect saturates at k ≃ 1 h Mpc−1, where a useful approximation is Pm(k, fν)/Pm(k, fν = 0) ≃ 1−8fν [61].

It is useful to stress that since fν is linear in Σmν, we have the somehow counterintuitive result that the effects of free-streaming are more evident for heavier, and thus colder, neutrinos. The reason is simply that the asymptotic suppression of the spectrum depends only on the total energy density of neutrinos, as this determines the different amount of non-relativistic matter between small and large scales.

Until now, we have somehow ignored the role of baryons in shaping the matter power spectrum. In fact, on scales that enter the horizon after zdrag, the baryons are effectively collisionless and behave exactly like cold dark matter. On the other hand, baryon perturbations at smaller scales, entering the horizon before zdrag exhibit acoustic oscillations due to the coupling with photons. This causes the appearance of an oscillatory structure in the matter power spectrum. These wiggles in Pm(k), that go under the name of baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), have a characteristic frequency, related to the value of the sound horizon at zdrag. Thus they can serve as a standard ruler and can be used very effectively in order to constrain the expansion history.

In more detail, the acoustic oscillations that set up in the primordial Universe produce a sharp feature in the two-point correlation function of luminous matter at the scale of the sound horizon evaluated at the drag epoch, rs(zd) ≡ rd; this sharp feature translates in (damped) oscillations in the Fourier transform of the two-point correlation function, i.e., the power spectrum. Measuring the BAO feature at redshift z allows in principle to separately constrain the combination dA(z)/rd, for measurements in the transverse direction with respect to the line of sight, or rdH(z) for measurements along the line of sight. An isotropic analysis instead measures, approximately, the ratio between the combination

called the volume-averaged distance, and the sound horizon rd. Given that the value of the sound horizon is well constrained by CMB observations, measuring the BAO features, possibly at different redshifts, allows to directly constrain the expansion history, as probed by the evolution of the angular diameter distance dA(z) and of the Hubble function H(z), or of their average dV(z). In particular, it is straightforward to see that BAO measurements put tight constraints on the Ωm − H0rd plane, along a different degeneracy direction that it is instead probed by CMB [62, 63]. Therefore, when estimating neutrino masses, the addition of BAO constraints to CMB data helps breaking the parameter degeneracies discussed in the previous section, yielding in general tighter constraints on this quantity.

The linear matter power spectrum for a given cosmological model can be computed using a Boltzmann solver. However, comparison with observations is complicated by the non-linear evolution of cosmic structures. Note that both CAMB and CLASS are able to handle non-linearities in the evolution of cosmological perturbations with the inclusion of non-linear corrections from the Halofit model [64] calibrated over numerical simulations. In particular, for cosmological models with massive neutrinos, the preferred prescription is detailed in Bird et al. [65].

From the observational point of view, Pm(k, z) can be probed in different ways. In galaxy surveys, the 3-D spatial distribution of galaxies is measured, allowing to measure the two-point correlation function and to obtain an estimate of the power spectrum of galaxies Pg(k, z). Since in this case one is measuring the distribution of luminous matter only, and not of all matter (including dark matter), this does not necessarily coincide with the quantity for which we have a theoretical prediction, i.e., Pm; in other words, galaxies are a biased tracer of the matter distribution. To take this into account, one relates the two quantities through a bias b(k, z):

The bias is in general a function of both redshift and scale. If it is approximated as a scale-independent factor, then the presence of the bias only amounts to an overall rescaling of the matter power spectrum (at a given redshift). In this case, one marginalizes over the amplitude of the matter spectrum, effectively only using the information contained in its shape. A scale-independent bias is considered to be a safe approximation for the largest scales: as an example, for Luminous Red Galaxies sampled at an efficient redshift of 0.5 (roughly corresponding to the CMASS sample of the SDSS III-BOSS survey), a scale-independent bias is a good approximation up to k ≲ 0.2 h Mpc−1 [66]. On the other hand, scale-dependent features are expected to appear on smaller scales. In this case, the bias can still be described using a few “nuisance” parameters, that are then marginalized over. In any case the exact functional form of the bias function, the range of scales considered, as well as prior assumptions on the bias parameters, are delicate issues that should be treated carefully. An additional complication arises from the fact that massive neutrinos themselves induce a scale-dependent feature in the bias parameter, due to the scale-dependent growth of structures in cosmologies with massive neutrinos [67, 68].