Hybrid World War and the United States–China rivalry

- 1Department of Geography, National University of La Plata, La Plata, Argentina

- 2Instituto de Investigación en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (IdIHCS), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Buenos Aires, Argentina

The proposal of the article is to advance on the concept of Hybrid World War and to relate it to the conflict between the United States and China in the present historical-spatial transition of the world system. The concept of Hybrid World War is developed in contrast to that of the New Cold War, and in relation to the characteristics acquired by the world capitalist system from 1970 to 1980 as a transnational system of production, trade, and finance, the dynamics of strategic competition in the crisis of the unipolar globalist order, and the characteristics of the rise of China and its significance, different from that of the USSR. From this conceptual framework, the United States-China rivalry is observed, analyzing: the systemic tension between unipolarism and multipolarism, the central dispute in Asia Pacific, and the development of a war on all fronts or unrestricted.

Introduction

Toward 2013 and 2014, from the conflicts in Syria and Ukraine or the growing tensions in Asia Pacific due to the increasing influence of China, the idea of a New Cold War began to appear in the press and among different “Western” analysts (Legvold, 2014; Roskin, 2014; Schoen and Kaylan, 2014). This idea appears, albeit in a diffuse form, in a context of increasing tensions between, on the one hand, the United States, and what we call the Anglo-American pole of power and its allies in the Global North—sometimes referred to as the West—and, on the other hand, the so-called emerging powers with the prominence of China and Russia and some states in the Global South. The idea of a “New Cold War” refers to four fundamental issues:

A- The emergence or re-emergence of new powers and the return of political-strategic competition between poles of power;

B- The crisis of the unipolar “liberal” world order challenged by the emerging powers;

C- The hinge in the map of world power (both material and symbolic) brought about by the 2008-2009 crisis to the detriment of the Global North;

D- The rise of a set of multilateral associations that propose an alternative world order (with a focus on Eurasia) and a leading role for emerging powers, especially China1.

Moreover, the “New Cold War” or Cold War II shares with its original reference–Cold War I–the assumption that mutually assured destruction inhibits the development of a conventional world war between powers such as those that occurred in the first half of the twentieth century, the period of “systemic chaos” (Arrighi and Silver, 1999) from 1914 to 1945.

One of the first significant publications that brought back to global analyses the concept New Cold War was the book written by Schoen and Kaylan (2014), entitled The Russia-China Axis: The New Cold War and America's Crisis of Leadership. There the authors, linked to The Wall Street Journal and with a neoconservative perspective, state:

Unless the US rebuilds a robust defense, clearly asserts its interests and values, assures its allies, and offers unapologetic leadership, we will fail. And our failure will carry with it a huge price: the collapse of post-World War II international architecture. To avoid such scenario, the United States —still the world's only “indispensable nation”— must reassume its rightful role as the world's only superpower (Schoen and Kaylan, 2014: 15).

Also, from Russia, some prominent authors begin to use this concept, at least rhetorically. Based on the new scenario that emerged with the conflict in Ukraine in 2014, Dmitri Trenin stated in an article entitled “Welcome to Cold War II” that the post-Cold War may now be seen, in retrospect, as the inter-Cold War period (Trenin, 2014). Secondly, the influential intellectual, Sergey Karaganov, analyzes that we are in a “New Cold War”, the Cold War II, which is, structurally, “a manifestation of the confrontation between the West and the non-West that is taking shape within the framework of Greater Eurasia, the ‘Belt and Road' initiative, and BRICS.” (Karaganov, 2018: 91).

For his part, Chinese President Xi Jinping has repeatedly called on the leaders of Western powers to discard the Cold War mentality (AP News, 2022). Although in this case, rather than using the concept of the New Cold War to analyze a global geopolitical situation, it is used to criticize the mentality and the discourses that legitimize American foreign policy against China. A critical look at the American mentality and/or practices of the Cold War also appears in Chinese intellectuals and academics (Suisheng and Guo, 2019; Zhao, 2019).

In Merino (2016a,b) it is observed that from 2013 to 2014 a geopolitical hinge takes place, giving way to a new moment of the crisis of the unipolar globalist world order under United States' hegemony. However, the sharpening of the political-strategic contradictions between poles of power -especially between the emerging powers and the dominant pole of power- does not produce a situation that can be interpreted under the concept of “New Cold War”, but of Hybrid World War or Hybrid and Fragmented World War (Merino, 2020)2. This new conceptualization is developed about the characteristics acquired by the world capitalist system from 1970 to1980 as a transnational system of production, trade, and finance, the dynamics of strategic competition in the crisis of the unipolar globalist order, and the characteristics of the rise of China and its significance, different from that of the USSR.

The proposal of the article is, precisely, to advance on the concept of Hybrid World War and to relate it to the conflict between the United States and China in the present historical-spatial transition of the world system, in which we are already in what Arrighi and Silver (1999) call the “systemic chaos” stage (which in other transitions was characterized by the 30-year wars). This transition has a set of fundamental tendencies that frame the conflict, among which are these two: (a) the relative decline of the Anglo-American pole of power and the West, in contrast with the rise of China, other emerging powers and Asia in general; (b) growing political-strategic contradictions, where a pattern of conflict predominates between the dominant forces and powers of the previous unipolar order against the emerging forces and powers that aim at a multipolar order, pressing for the redistribution of world power and wealth.

Hybrid World War

Hybrid Warfare emerged a few years ago as a concept that synthesizes a new way of making war. That is, as “warfare”, but not as “war”, a situation of struggle between two entities. In one of the first texts in which the subject appears, Hoffman links it to a new and complex world reality that the United States must face due to the extension of “globalization, the proliferation of advanced technology, violent transnational extremist, and resurgent powers” (Hoffman, 2009, p. 34). For Hoffman, “the most distinctive change in the character of modern warfare is the blurred or mixed nature of combat. We are not facing an increasing number of different challenges, but their convergence in hybrid wars” (Hoffman, 2009, p. 37). In a critical review of the literature on the subject, Johnson states that Hybrid Warfare is the “synchronized application of political, economic, informational, CEMA [Cyber and Electromagnetic Activity] and military effort, for strategic objectives, that minimizes the risks that accompany conventional war. It follows that countering these techniques must also either embrace a full-spectrum set of responses, or be so effective and overwhelming in one particular sphere that hybrid methods are abandoned by an enemy as ineffective or inefficient” (Johnson, 2018, p. 158). In addition, Hybrid Warfare is a form of warfare in which there is a particular combination of conventional/unconventional, regular/irregular and information and cyber warfare.

Another who has addressed the issue is Nye (2015), who observes that today's wars are hybrid and unlimited. In them the fronts blur and target the enemy's society to penetrate deep into its territory and destroy its political will (fourth generation warfare), blurring the military front from the civilian rearguard. To this end, technologies such as drones and offensive cyber-tactics allow soldiers to remain at a continent's distance from civilian targets (fifth-generation warfare). In the new wars, the line between the military front and the civilian rear is increasingly blurred. In addition, the shift from classical interstate warfare to armed conflict with non-state parties, such as rebel groups, terrorist networks, militias and criminal organizations, is accelerating. Nye notes that conventional and unconventional forces, combatants and civilians, physical destruction and information manipulation are completely intertwined. In this sense, the ultimate objective of wars is the “hearts and minds” of the people, as stated by the British Gerard Templer, who commanded the war against the Malayan anti-colonial forces, which exalts the importance of the struggle in the journalistic-media field, the information and “psychological” warfare.

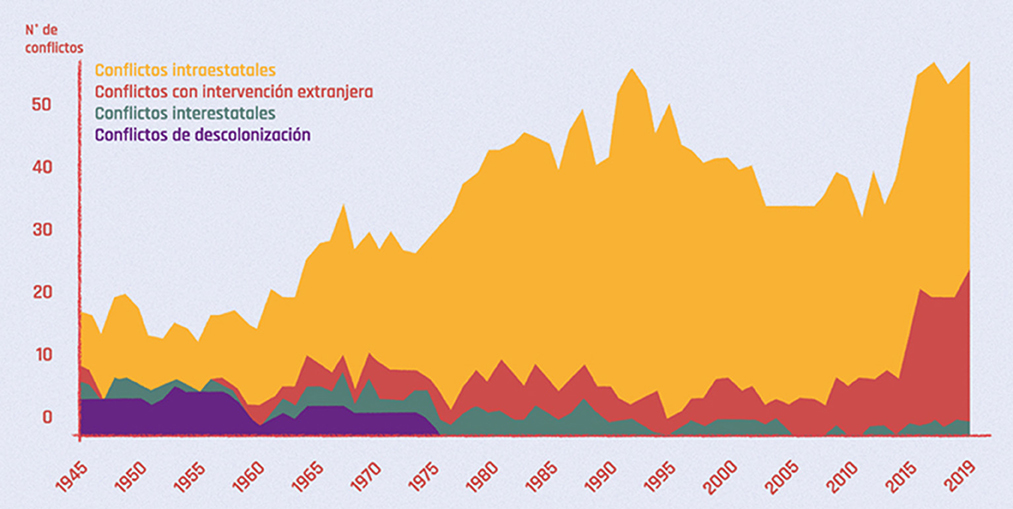

Another element is the growing “privatization” of war. After the United States' defeat in Vietnam, a process of loss of legitimacy of its war offensives began throughout the world and within its own population, especially because of the costs in human lives. As a result, the use of mercenaries or outsourced forces (in line with the productive paradigm of “post-Fordist” outsourcing on the rise), such as the paradigmatic example of Blackwater, the American military company created in 1997 that operated in Iraq and Afghanistan, among several other foreign interventions, began to be increasingly resorted to. Its growth was such that the number of contracted workers exceeded the number of American soldiers in both territories (Scahill, 2008). The modalities of conflict have also changed in recent decades, with fewer conflicts between states, and a proliferation of conflicts within states or at the level of regions or zones. As can be seen in Figure 1, since 1945 there has been a decline in interstate conflicts (in green), while by 1975 wars of decolonization (in light blue) were in decline and intrastate conflicts (in yellow) were on the rise. Conflicts with foreign intervention (in red) are the most lethal.

Figure 1. War in the twenty-first century: of robots and men, the upside down of maps (Arte, 2021).

While for the American authors the term “Hybrid Warfare” is generally used to describe the sophisticated means that both state and non-state actors would employ to mitigate a conventional disadvantage against the United States—closely linked to the concept of asymmetric warfare, for the Russian researcher (Korybko, 2015), Hybrid Warfare is a new method of indirect warfare conducted by the United States (the only power with the capacity to do so) with a view to producing regime change. In order to achieve this objective, this type of indirect warfare combines the tactics of “color revolutions” with non-conventional wars, in a multipolar scenario and where the costs of conventional warfare between powers are very high. For this author, Hybrid Warfare is the new horizon of the United States' strategy to produce changes in regimes contrary to its interests. Although it is played out in secondary scenarios, it is aimed especially at three states that constitute the core targets of the United States: China, Russia and Iran.

From China, one of the first and resounding works on a new mode of warfare is the famous book Unrestricted Warfare, published by the officers of the People's Liberation Army (Liang and Xiangsui, 1999). There they note that the central principle of the new wars is that there are no rules, as they comprise all possible modes of action, the use of all means, with deployments on all fronts, the multiplication and diversification of “non-lethal” means and where the attack on the adversary is subtle, slow but systematic. This new type of warfare is closely related to the economic, political and technological transformations related to “globalization”, as a comprehensive, deep, structural and structuring process, in which a set of meta-national, transnational and non-national organizations emerge.

At the time of the emergence of the early nation states, the births of most of them were assisted by blood-and-iron warfare. In the same way, during the transition of nation states to globalization, there is no way to avoid collisions between enormous interest blocs. What is different is that the means that we have today to untie the “Gordian Knot” [3] are not merely swords, and because of this we no longer have to be like our ancestors who invariably saw resolution by armed force as the last court of appeals. Any of the political, economic, or diplomatic means now has sufficient strength to supplant military means. However, mankind has no reason at all to be gratified by this, because what we have done is nothing more than substitute bloodless warfare for bloody warfare as much as possible. As a result, while constricting the battlespace in the narrow sense, at the same time we have turned the entire world into a battlefield in the broad sense (Liang and Xiangsui, 1999, p. 241).

The Chinese People's Liberation Army, in its official document or white paper entitled “China's National Defense in the New Era” published in 2019, refers to key concepts of hybrid warfare, although it does not elaborate on them: War is evolving in form toward informationized warfare, and intelligent warfare is on the horizon. The concept of “intelligent warfare” would be quite similar to the “hybrid warfare”, but cognitive terrain stands out with the use of intelligent weapons and equipment and their associated operating methods, backed by the Internet of Things information system. In 2020, this new concept of war was incorporated into the 14th Five-Year Plan that governs the destinies of the country.

In Latin America, Fiori (2018) is one of the prominent authors dealing with this concept. He defines this new form of warfare as follows:

A succession of interventions that transformed this type of war, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, into an almost permanent, diffuse, discontinuous, surprising and global phenomenon. It is a type of war that does not necessarily involve bombings, nor the explicit use of force, because its main objective is to destroy the political will of the adversary through the physical and moral collapse of its State, its society and any human group that you want to destroy. A type of war in which information is used more than force, siege and sanctions more than direct attack, demobilization more than weapons, demoralization more than torture. By its very nature and its instruments of 'combat', it is an 'unlimited war', in its scope, in its preparation time and in its duration. A kind of infinitely elastic war that lasts until the enemy's total collapse, or else it turns into a continuous and paralyzing belligerence of the 'adversary' forces (Fiori, 2018, p. 402–403).

From this perspective, Salgado (2020) applies this concept to the analysis of the South American region and observes the Hybrid Warfare actions deployed by the United States in the twenty-first century to regain strategic political control of the region. On the other hand, Romano and Tirado (2018) emphasize lawfare as part of Hybrid Warfare in the region.

A new way of warfare is always in relation to transformations occurring at the structural level in the world system and secular processes. Mackinder (1904) observed that the “post-Columbian” era—which began at the beginning of the twentieth century when the expansion of the modern capitalist and Western world system covered practically the entire planet—had as its central characteristic the development of a closed political system with a global scope. This meant that strategic competition shifted from territorial expansion to the struggle for relative efficiency. In the same sense that modern capitalism implies, once consolidated, a permanent struggle in which the key is relative surplus value, in the pursuit of which know-how and technologies, as well as the organization of society, are continually revolutionized, and in the pursuit of which the capitalist system is constantly changing.

While elements of Hybrid Warfare can be recognized throughout history, it has become the dominant form of confrontation in a deeply interconnected and interdependent world, where the transnationalization of capital commanded by the financial networks of the Global North, the formation of a transnational productive system and the development of companies and other actors operating on a global scale have modified the structure of power. Space was drastically dwarfed—and in some cases eliminated—in temporal terms. This was matched at the political and strategic level. The nature of the United States' hegemony, with its global multilateral institutions, constituted a qualitative change in the world system, pushing the depth of overall interdependence to new levels. This was accentuated by globalism in the 1990s (under the dominance of Anglo-American global finance capital), as a transnational political force and project emerging from the Anglo-American core, but which goes beyond that core. The world system has practically no exteriority—which does not imply the elimination of the control of the flows of information, money and goods that traverse it and mediate the interstate system. There is a “closed” political system, in which the interstate system develops, which has deepened even more since the fall of the USSR. As Flint and Taylor (2018) note, the economy of the USSR and the countries of its sphere of influence were not outside the world economy and the world system. However, their integration was from the place of semi-periphery, with a low relative interdependence with the capitalist world and, clearly, there were defined blocs that configured a dominantly bipolar order (which does not imply ignoring the Third World, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Third Positions). The current dynamic is completely different. China is not the USSR, its integration in the world economy is completely different quantitatively and qualitatively—it is not only the great manufacturing workshop of the world economy, but is also increasingly involved in global command activities, and the current geopolitical dynamics is multipolar.

For this reason, in the current deep network of interdependence, it is not possible in the short and medium term for national economies to decouple beyond certain disconnections in strategic sectors that define the central nodes and where a certain “decoupling” has always existed, although it is now increasing-, war develops at the same time as there is cooperation in the production of value.

The Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA), in its official document or white paper entitled “China's National Defense in the New Era” published in 2019, reinforces this diagnosis of the contemporary historical and spatial situation by stating that: “Today, with their interests and security intertwined, people across the world are becoming members of a community with a shared future” (PLA, 2019, p. 1). The shared future is not just a wish or an expected horizon, but a historical condition that is imposed almost inexorably in a deeply interdependent world in which the interests and security of humanity are intertwined. Besides, the document states that, in an increasingly multipolar world, “international security system and order are undermined by growing hegemonism, power politics, unilateralism and constant regional conflicts and wars.” (2019, p. 2). It is observed than international strategic competition is on the rise. The United States has adjusted its national security and defense strategies, and adopted unilateral policies. This process may continue to escalate, deepening the confrontations at all levels, and we cannot rule out other more tragic scenarios.

This brings us to another level: in addition to analyzing the new way of waging war, it is necessary to note that there is in fact an ongoing war—a historical event, which assumes as its dominant form a hybrid character, in which the confrontational component is exacerbated in relation to the cooperative component (which continues to exist as a relationship of necessity, interdependence). As Zhao (2019) observes, in the particular but structural case of the United States–China relationship, it has always been defined by a mix of cooperative and competitive interests since normalization in the 1970s. The difference is that now the latter term takes precedence and the former is subordinated. In this sense, one of the central theses of this paper is that since 2014 a Hybrid World War has begun, whose intensity is increasing in the heat of the acceleration of a set of trends of the current historical-spatial transition of the world system, which emerges from the crisis of American (or Anglo-American) hegemony, in a historical-spatial transition of the world system that evolves from that crisis toward systemic chaos.

The triggering event is the war in Eastern Ukraine, which articulates an intrastate but also interstate conflict, with a regional conflict in Europe between NATO expansion and Russia's red lines, and a global conflict between the old dominant core and the emerging powers of the semi-periphery and the periphery of the world-system (Merino, 2022). From then on, the economic war against Russia is unleashed with more than 2,500 sanctions by the United States and the Global North represented in the G7, but also warlike confrontations multiply and reach at least a dozen in the so-called “area of instability” of the Middle East, Central Asia and the surrounding areas. In addition, disputes between powers are intensifying in Syria, Afghanistan and the China Sea, among other places, and, as we shall see, competition is emerging between different global and regional political and economic initiatives, most notably the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Since 2014, the confrontations between the main poles of world power have become direct (although not directly and conventionally warlike) and in central territories. At the same time, in a set of secondary scenarios, military escalations are multiplying, as well as clashes on other fronts, involving and confronting the main powers.

In an interview for La Vanguardia during the month of June 2014, Pope Francis stated that the Third World War was developing in pieces. It is interesting to rescue his vision because it shows us how the new world geopolitical scenario is beginning to be perceived and analyzed by key actors and institutions:

We discard a whole generation to maintain an economic system that is no longer sustainable, a system that in order to survive must wage war, as the great empires have always done. But since World War III cannot be waged, then zonal wars are waged. And what does this mean? That weapons are manufactured and sold, and with this the balance sheets of the idolatrous economies, the great world economies that sacrifice man at the feet of the idol of money, obviously become healthy3.

This paragraph contains many central ideas on the current world conflict. The first is that, given the impossibility of carrying out a conventional world war (the principle of mutually assured destruction prevails), the confrontation is carried out in specific zones or territories, manifesting itself in fragments of a world structural conflict. The second central idea of this paragraph is that the crisis of the prevailing world system (“which is no longer sustainable” and discards “a whole generation”), which is related to the breakdown of the Anglo-American hegemony, is what provokes and leads to war: “A system that in order to survive must wage war, as the great empires have always done”. The third idea is the connection between the economic system with its structural problems, imperial needs and the interests of the arms industry. In this sense, the military industrial complex (MIC) of the powers and, in particular, of the United States, constitutes the core of their system of production and technological innovation. With a military budget of more than 778 billion dollars in 2021 (practically 40% of the world total), the great power of the Global North has the MIC as a central element of its economy, from which it feeds private corporations and finances technological development. To this are added the specific budgets for wars and special operations.

In short, the Hybrid World War (HWW) or Hybrid and Fragmented World War expressed a new generation warfare, where elements of conventional warfare (between states with regular armies—as we see today between Ukraine and Russia on the territory of the former) and non-conventional and/or irregular warfare are combined. A war that involves the main poles of world power, is centrally driven by the United States in the face of a situation of relative decline, and has as its main contradiction the forces of the old unipolar globalist order in crisis vs. the emerging forces tending toward the conformation of a multipolar order. This GMH is developing on all fronts: economic, technological, financial and commercial; informational, psychological and virtual. Thus, we speak of commercial warfare, economic warfare, information warfare, psychological warfare, cyber warfare, currency warfare, financial warfare, biological warfare4, judicial warfare (known as lawfare) and cognitive warfare. A central characteristic is that Hybrid War is completely blurred: the boundary between military and civilian, between the beginning and the end, between public and private is blurred.

United States–China rivalry and unipolarism–multipolarism tension

One of the structural tendencies of the historical-spatial transition of the world system is the sharpening of a set of systemic political-strategic contradictions that are becoming antagonistic. This process is developing, among other causes, from the relative decline of the Anglo-American pole of power and the Global North, which contrasts with the rise of China, other emerging powers from the semi-peripheral regions and Asia as the great continent of the twenty-first century. The quest by dominant forces in the United States and the Global North to halt this rise and the shift in the new map of power is key to understanding the Hybrid World War. In this sense, with the beginning of the geopolitical transition in 1999–2001 and with its different administrations (Bush, Obama, Trump and Biden), the United States at the beginning of George W. Bush's administration (2001–2009) changed the framing of relations with China from “Strategic Partnership for the twenty-first Century” to “Strategic Competition”. The neoconservative perspective synthesized in the Project for a New American Century was imposed in geo-strategy to try to ensure United States' unipolarism, preventing the emergence of any competitor in Asia Pacific, Europe or the center of Eurasia. This was expressed in the so-called Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to advance in the control of Central Asia and the Persian Gulf.

These wars were the reaction of the United States and its allies to some signs of movements against the unipolar world order: the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001 in the heart of Eurasia by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan; the Chinese initiative known as “Go Out Policy” launched in 1999 to promote outward investment by state-owned enterprises, along with a new five-year plan (Tenth Plan 2001–2005) that has as its priority its own technological development; Putin's triumph in Russia and the development of Russian Eurasian nationalism against unipolar globalism; a possible greater European strategic autonomy following the establishment of the Euro; and the emergence in Latin America of progressive or national-popular governments critical of neoliberalism, the Washington Consensus and United States' Hegemony. This occurs in a context in which the “Punto Com” crisis (due to the bursting of the technology bubble) hit the Global North and shows the unstable nature of neoliberal financialization. The next outbreak occurred in 2008 and its impact is even deeper. In that scenario, in 2009 the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) was launched, articulating in a bloc the industrial and regional powers of the semi-periphery in search of democratizing wealth and world power. It is not by chance that from 2008 to 2021 China's GDP has nominally quadrupled, since economic accumulation and political strength go hand in hand, both manifesting in the ability to break the mechanisms of geopolitical dependence and subordination.

The arrival of Barack Obama to power marked the return of globalism perspective, that meant a change in the American geostrategy. Faced with the emerging powers —expressed in the BRICS, Obama administration sought to deploy a containment strategy, reinforcing control of the Eurasian peripheries and promoting the turn toward the Asia Pacific. In the Western periphery, the NATO continued its expansion to the Russian borders (especially with Ukraine), and supported the expansion of the European Union and the proposal to establish the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP). In the Asia Pacific region, the globalist geostrategy sought to try to lay the foundation of a kind of Indo-Pacific NATO led by India, Japan, and Australia (trying to incorporate the ASEAN countries), and along with it, advance with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)5. In addition, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton promoted in 2011, the development of a New Silk Road with a center in Afghanistan6, which was accompanied by a stronger intervention in military terms with an increase of 100,000 more American soldiers. This was part of the Pivot to Asia announced by Obama in 2012: moving the bulk of the United States' air-naval military force to the Pacific, to tighten the military siege around China. Hillary Clinton, as Secretary of State, laid out the main arguments for this shift in American foreign policy in an article published the year before. She affirms that the future of world politics will be decided in Asia and the Pacific, not in Afghanistan or Iraq, and the United States should be right in the center of the action (Clinton, 2011). It was aimed at encircling and containing China and Russia, ensuring the dominance of Eurasia, and imposing the rules of the game of twenty-first century capitalism. The geostrategy of the TPP can be summed up in the following words from the President of the United States, Barack Obama: “When more than 95 percent of our potential customers live outside our borders, we can't let countries like China write the rules of the global economy. We should write those rules, opening new markets to American products while setting high standards for protecting workers and preserving our environment7.” For his part, the then Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter, declared that for the security interests of the United States in Asia, the TPP can be considered as important as the addition of another aircraft carrier in the region, and is essential for the re-balance of power in Asia in favor of the United States8.

The TPP was conceived in a close relationship between the economic and geostrategic dimensions (as administration of geopolitical and economic-political interests). According to Green and Goodman (2015), the agreement reinforced the rules of the twenty-first century game in Asia-Pacific according to the liberal American perspective. This is the most dynamic region in the world, where trade has always defined order and power. Green and Goodman (2015) point out that as the region's economy has shifted from the United States or Japan to China, the Sino-centric model has become irresistible for Beijing. The TPP, then, would have an important geopolitical impact in terms of the distribution of power in Asia, to contain China, reinforcing the strategic political fence. For this reason, it is essential to “protect” states, such as the Philippines, Vietnam or Taiwan from the “great dependence” of the Chinese economy so that they do not lose their independent diplomacy and political influence. They consider that it is fundamental for the strategic interests of the United States that Taiwan joins the TPP, and that Japan and Australia help in this process. At the same time, however, from 2008 to 2021 there has been a sharp increase in trade in goods and services between the United States and China; particularly imports of goods from the Asian giant, the main supplier of goods to the United States, which grew by almost 50% in that period. Interdependence is increasing while strategic competition is accelerating and attempts by dominant forces in the United States and the Global North to contain/stop China's rise—or subsume it—are growing.

In this scenario, in 2012 Beijing formally promoted negotiations to form the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and, in 2013, launched the revolutionary Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the face of containment strategies promoted by Washington and its allies. Along with this, a new global financial architecture is being promoted. This was expressed with the creation of new international financial instruments like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the launch of the BRICS New Development Bank and a reserve fund (Contingent Reserve Agreement), at the summit in Fortaleza, Brazil, in 2014. This financial architecture is developing in parallel with the Global North's, which is centered on the IMF and WB. Besides, in 2014 Moscow advanced in “annexation” or “recovery” of Crimea as a Republic within the Russian Federation and formed the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) together with the former Soviet republics of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan who were later joined by Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. It did so in agreement with China, articulating the EAEU with the BRI and strengthening the SCO. Today, the SCO is seen in the geopolitical West as a political association that opposes NATO in Eurasia—or “rogue” NATO (Aydintaşbaş et al., 2022), and even compares the relative military presence in key regions of the great continent (Sun and Elmahly, 2019). Since 2015, India, Pakistan and Iran joined the SCO, giving the entity another geopolitical volume. In addition, it has Belarus, Afghanistan and Mongolia as observer members, and Turkey, Sri Lanka, Armenia, Cambodia and Nepal as dialogue partners. Most of these countries share China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), that for western perspectives, such as Kissinger's (2017), by seeking to connect China to Central Asia and eventually to Europe, the new “Silk Road” will in effect shift the world's center of gravity from the Atlantic to the Eurasian landmass. Together with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and other institutions, such as Chinese State Banks, they express instruments of geopolitical weight that bring together a large number of countries and regions of the world in a new emerging regional and global institutionality -proper of a multipolar multilateralism. The alliance between China and Russia is deepening at all levels to consolidate a power structure on the Eurasian continent of a great Eurasian association, counteracting the superiority of the “Empire of the Sea”, as they are called the western maritime powers, today led by the United States (Li, 2018; Zhao, 2018; Zheng, 2020).

These movements exacerbate the reactions of the United States and the geopolitical West and have fueled the development of a hybrid world war since 2014 (especially since the conflict in Donbas, Ukraine, started in April 2014). This war expresses the antagonistic evolution of the contradictions between the global-unipolar multilateralism and the institutions of the old world order built under United States' hegemony, and the multipolar multilateralism and the new institutions that express a new map of world power. Besides, we can observe the breaking of the strategic supremacy of the United States and NATO in the face of the growing capacity of China, Russia, and other actors. In addition, the strategic fissures within the old allies are key. Lastly, there is a crisis of neoliberal globalization commanded by the Global North and the emergence of a globalization driven by China and other emerging forces, in a relatively multipolar world.

The dispute in Asia Pacific

In the geopolitical design of United States' hegemony since the end of World War II, there has been a red line in the Asia Pacific that marks the strategic limit that a coalition led by the United States and Japan must maintain to prevent China (or an anti-hegemonic coalition) becoming a global power, which would imply the loss of world primacy for the United States (Brzezinski, 1997, p. 173–188). At present, that limit has already been crossed and strategic overlap is ongoing. This is observed both economically as well as in a set of multilateral institutions and initiatives of the new multipolar world that has Beijing as a protagonist.

One of the keys for Washington in the region is to secure the two chains of military bases and positions that contain/surround China, under American political-strategic command. The geopolitical role of this forward defense perimeter was simple for MacArthur; “From this island chain we can... prevent any hostile movement into the Pacific” (Scott, 2012, p. 617). Taiwan is a centerpiece of the first chain and a central American strategic outpost against China. Beijing, in its ascent, overlaps and surpasses these two chains. Hence the dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, located in the East China Sea, northeast of Taiwan. Such control would allow China to partially break the first chain, weaken Taiwan's strategic position in the East China Sea and Taiwan Strait. The construction of military infrastructure on atolls by building artificial islands is part of this move toward South China Sea, as is the strong advancement of its missile (including hypersonic technology) and naval capabilities. In the case of the South China Sea, several islands are being disputed among Asian countries: the Paracelsus Islands (also known as the Xisha Islands and the Hoang Sa Archipelago), claimed by China, Vietnam and Taiwan; and the Spratly Archipelago (called Nansha in China), claimed by China, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia and the Philippines. A fact of great importance is that the South China Sea is not an open sea. On the contrary, it has numerous straits of strategic importance, the most important being the Strait of Malacca, where Singapore and an American naval base are located. Another very important American Navy base for its presence in the region is in the Philippines.

Both seas are fundamental to the global economy. They are at the heart of the world's most dynamic region, which accounts for a third of global output and trade, and where China has a clear leadership position—consolidated with the effective implementation of the RCEP in January 2022. But China's military capabilities have also advanced to the point of challenging the primacy of the United States in the Asia-Pacific. According to a report issued this year by the American Congressional Research Service, United States' naval primacy is in crisis in the Western Pacific (Congressional Research Service, 2020). On the military side, the current situation is no longer what it was a few years ago, when the United States was the preponderant world power by far. In terms of military budget, there is a large gap between the more than 778 billion dollars of the United States and the almost 252 billion of China (although such nominal budgets should be translated into real purchasing power). China has steadily increased its military budget and capabilities over the last two decades, multiplying its defense spending by 12 times since 2000, in line with the evolution of its GDP. It is recognized as a leader in cyberwarfare, use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and industry 4.0 for defense, and has also developed hypersonic missiles. Since 2020, the People's Liberation Army has funded multiple AI projects with multiple applications, including machine learning for strategic and tactical recommendations, war gaming for training, and social network analysis. According to an American Department of Defense report (2021), China's bet is to use AI to directly influence enemy cognition, while leading key technologies with significant military potential, such as AI itself, autonomous systems, quantum computing, data science, biotechnology and advanced manufacturing materials. Thus, it is deploying plans to modernize its defense system, integrating “computerized and intelligent” development.

In addition, to strengthen its military presence in Asia Pacific, the Chinese government unveiled in June 2020 the establishment of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea, which is added to the ADIZ established in 2013 in the East China Sea. And in mid-April 2020, Chinese media published the government's decision to create two new districts as part of the city of Sansha on the southern island of Hainan.

In response to this, the United States deployed two aircraft carriers there in July 2020. It also abandoned its “neutrality” in territorial disputes, aligning itself with Vietnam and the Philippines. The then Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo (a member of the ultra-conservative Tea Party and who now stars in a fierce escalation of discourse against China, proposing a New Cold War) stated: “We are making clear: Beijing's claims to offshore resources across most of the South China Sea are completely unlawful, as is its campaign of bullying to control them (…) The world will not allow Beijing to treat the South China Sea as its maritime empire9.” This alignment also implies a breakdown in the role of the United States as an arbiter in the region, a further indicator of the breakdown of hegemony.

Along with claims for sovereignty and maritime rights, since 2010 there has been an increase in confrontations in which the United States has become increasingly involved as an extraterritorial actor. Along with this, and in what constituted a historic turn in its foreign policy, Japan, a strategic ally of the United States in the region, modified a few years ago the interpretation of its “Peace Constitution” to be able to fight abroad and defend its partners, even if it is not attacked. Tokyo, in turn, recently strengthened its ties with the West, seeking to strengthen the Global North, starting with the establishment of free trade agreements with the EU and the UK, which came into force in 2019 and 2021, respectively.

Another strategic initiative to contain China is the QUAD—Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—promoted by the United States together with Japan, India and Australia. Initiated by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007 in response to growing Chinese economic and military power, QUAD was reinstated in November 2017 under the United States' administration of Donald Trump as part of his “New Cold War” against China, and is seen by Beijing as an Asian NATO. In reality, it would be a kind of basis for creating a NATO-like alliance in the Indo-Pacific region. In a joint statement in March 2021 entitled “The Spirit of the Quad,” the Quad members claimed to have “a shared vision for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” and a “rules-based maritime order in the East and South China seas”.

However, the Quad's actions to serve Western interests have recently been weakened by India's stance. Under its doctrine of “strategic autonomy” and “strategic balance”, it distanced itself from the West in the face of the war in Ukraine and strengthened its trade relations with Russia in the face of the deepening economic war against Moscow through sanctions. Indeed, New Delhi had already been having a balancing act, joining the SCO in 2016, although rejecting the BRI or joining the RCEP. In turn, it already has Beijing as its main trading partner. However, India and China have major border disputes.

September 2021 also saw the establishment of AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom and United States), a strategic alliance aimed at defending the interests of the three Anglo-Saxon nations in the Indo-Pacific. In fact, it consists of equipping Australia (a country whose constitutional sovereign is the British monarchy) with greater military capabilities to make it a key strategic asset of the Anglo-American pole of power in the Asia-Pacific. China has seen it as a threat, asserting that it “seriously undermines peace and stability” in that region and “intensifies the arms race”. In turn, the agreement would allow Australia to build its first nuclear-powered submarines (joining a select group that includes the United States, UK, France, China, India, and Russia), with American technology. Washington had only transferred its technology to the UK more than 50 years ago. In turn, in April 2022 the AUKUS announced that it will accelerate the development of advanced hypersonic and anti-hypersonic capabilities, as well as defense cooperation on issues, such as electronic warfare, cyberwarfare and AI. In this way, it seeks to counter the capabilities developed by Russia and China in recent times. The recent agreement between Beijing and the Solomon Islands is a major blow to this strategy, as the island nation was considered Australia's “backyard” in the Asia–Pacific.

War on all fronts or unrestricted

In December 2017, under the new administration of Donald Trump, the White House published a new National Security Strategy (National Security Strategy, 2017) document where with total clarity China and Russia were defined as main adversaries, displacing from that place the diffuse entity called international terrorism: “China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity” (National Security Strategy, 2017, p. 2). In the new strategic framework defined as Great Power Competition (GPC) instead of GWoT, Trump administration relaunched “Star Wars”, created the “Space Force” and breached nuclear disarmament treaties to launch a process of modernizing its arsenals. In turn, Donald Trump's administration, which expressed a strengthening of the “nationalist-Americanist” forces in the United States, declared a trade war on the world. With this, a protectionist turn and a practice of trade bilateralism was set in motion, which serves to protect and encourage the set of American capitals that are not competitive in global terms, to recover the national industrial base, to try to control the trade deficit while deepening the fiscal stimulus and, in addition, to establish strategic political negotiations, both in technological and geopolitical matters, which ensure United States' primacy. This was summed up in the slogan “America first”. In this way, the economic war—previously localized in countries, such as Cuba, Venezuela, Iran and, since 2014, Russia—whose main target state is China, became global. With this, it is decided to deepen the struggle against the emerging poles of power at world level that mediates, through the State, the global struggle between capitals or inter-corporate, which is becoming more acute with the slowdown of economic growth and the challenging advance of large Chinese companies.

The trade war highlights the limitations of the United States and the Global North to sustain their predominant position and, as the other side of the same coin, their internal fracture. This war reflects the loss of United States' productive primacy and the breakdown of the technological monopolies of the Global North. This is reflected in the huge trade deficit of the United States (and in particular the one it has with China) and in the narrowing of the technological gap with the Asian giant, as a result of the plans developed in this regard since 1999, and especially the Made in China 2025 plan launched in 2015. Since 2019, China has led the world in technological patent applications and Huawei is the world's leading company in this field. This process implies the breakdown of the post-Fordist center-semi-periphery relationship between the Global North and China, completely transforming the world economy: its division of labor, its hierarchies. In turn, as part of the protectionist “turn” to satisfy the interests of his increasingly less competitive industrial sector, Trump decided as soon as he took office to leave the TPP and the TTIP, breaking two key initiatives of the globalist geo-strategy to contain China, Russia and the new axis of emerging powers centered in Eurasia. This decision necessarily had important costs with allies and countries close to the United States, especially in Asia Pacific, as it reflects the difficulty to lead the world economy in relation to the dynamics of its corporate and national security interests.

China's own weight and its place in the world economy as the world's major industrial workshop (its industrial GDP is equal to the sum of the United States, Germany and Japan combined) and a major engine of world growth, hindered the American strategy of a “trade war” and attempts to subordinate China in various ways (Poch, 2022). The case of Huawei is paradigmatic since as one of the central targets of the Trade War, it still remained the world's largest supplier of telecommunications equipment, a leader in 5G and the top company in global applications for technology patents. However, the “Made in China 2025” technological development plan could not be stopped either. Beijing is already leading in key technologies of the ongoing industrial revolution, such as Artificial Intelligence, 5G and the Internet of Things, and the post-fossil energy transition. The Chinese BATX (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Xiao-mi) is emerging from the American GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple), narrowing the gap year by year and is even superior in some specific areas.

Under Biden's administration, the technology war with China has deepened, especially in the semiconductor sector, so that some analysts are already talking about a chip war (Miller, 2022). In this sense, in an extreme measure on October 7, 2022, the American government announced a ban on the export of semiconductors to China for supercomputers and artificial intelligence, as well as the equipment to manufacture them. This move goes hand in hand with a program unveiled to stimulate the domestic semiconductor industry of $52 billion approximately, as part of the Science and CHIPS Act passed in July 2022 involving $280 billion in funding. For its part, Beijing has decided to allocate a $150 billion fund for the development of a local semiconductor industry, in addition to the funds it has been investing in the sector for years. More broadly, Washington's objective is to prevent Beijing from developing its own capabilities at the highest levels of this key technology, to slow down Chinese growth in highly complex industries and to “decouple” strategic areas of the economy of both economies. For its part, Beijing seeks to reduce dependence on the Global North, and especially on its technology. According to the West's perspective, China would seek to achieve economic independence at several levels: in technology, the aim is to stimulate domestic innovation and localize strategic aspects of the supply chain. In energy, the goal is to boost the deployment of renewable energy and reduce dependence on oil and gas. In food, the goal is to revitalize the local seed industry. In finance, the imperative is to counteract the potential weaponization of the American dollar10. From China, it is observed that the war to stop its rise driven by the United States, far from abating, is going to deepen, therefore it is vital to build these capacities, although without ceasing to promote another globalization with Chinese characteristics (Jabbour et al., 2021) that reinforces interdependence with the Global South.

Since 2017, under a strategic framework of great power rivalry (Merino, 2021), the United States and allies have advanced in the use of the so-called “New Cold War” as a friend-foe geostrategic device, in order to pressure different countries to align with the United States, whether they are traditional allies and vassals or enemies. This includes political pressure, intelligence operations, military threats, economic and financial sanctions, and blockades of Chinese technology companies, such as Huawei, in third countries11. In the case of technology companies, the central argument is the security threats they pose. The West's monopolistic leadership in telecommunications and ICTs gave it global control of information and intelligence. This monopoly has been broken with the advance of Chinese companies.

Another front of the conflict is the promotion of internal conflicts, which are articulated with global propaganda tasks and intelligence operations. In the case of China, conflicts that threaten its territorial integrity are promoted from the West and, at the same time, are used in the increasingly intense global propaganda war under the hackneyed banner of human rights. We are referring in particular to Hong Kong12, Tibet, Xinjiang. Indeed, during the first months of 2022, Beijing had to face demands in Hong Kong, Tibet and Xinjiang for greater autonomy. It also saw rising tensions with an increasingly defiant Taiwan autonomous government, strongly supported by the United States. The visit to the island by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in August involved a major escalation of the conflict.

Closing remarks

Toward 2013 and 2014, from the conflicts in Syria and Ukraine or the growing tensions in Asia Pacific due to the increasing influence of China, the idea of a New Cold War began to appear in the press and among different “Western” analysts. However, the sharpening of the political-strategic contradictions between poles of power especially between the emerging powers and the dominant pole of power- does not produce a situation that can be interpreted under the concept of “New Cold War”, but of Hybrid World War or Hybrid and Fragmented World War. This new conceptualization is developed about the characteristics acquired by the world capitalist system from 1970 to1980 as a transnational system of production, trade, and finance, the dynamics of strategic competition in the crisis of the unipolar globalist order, and the characteristics of the rise of China and its significance, different from that of the USSR.

The Hybrid World War (HWW) or Hybrid and Fragmented World War expressed a new generation warfare, where elements of conventional warfare (between states with regular armies—as we see today between Ukraine and Russia on the territory of the former) and non-conventional and/or irregular warfare are combined. A war that involves the main poles of world power is centrally driven by the United States in the face of a situation of relative decline, and has as its main contradiction the forces of the old unipolar globalist order in crisis vs. the emerging forces tending toward the conformation of a multipolar order. This GMH is developing on all fronts: economic, technological, financial and commercial; informational, psychological and virtual. In spatial terms, Asia Pacific is a key region in this war and where the strategic competition between the United States and China is most clearly visible.

One of the structural tendencies of the historical-spatial transition of the world system is the sharpening of a set of systemic political-strategic contradictions that are becoming antagonistic. This process is developing, among other causes, from the relative decline of the Anglo-American pole of power and the Global North, which contrasts with the rise of China, other emerging powers from the semi-peripheral regions and Asia as the great continent of the twenty-first century. The quest by dominant forces in the United States and the Global North to halt this rise and the shift in the new map of power is key to understanding the HWW. This war expresses the antagonistic evolution of the contradictions between the global-unipolar forces and the institutions of the old world order built under United States' hegemony, and the multipolar forces and the new institutions that express a new map of world power. In their interstate form, these systemic contradictions between political and social forces that become antagonistic are expressed in the United States–China rivalry. The Pandemic has accelerated the trends of the current transition, shaping a new geopolitical moment in which HWW has jumped in intensity.

Author's note

Professor and Researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales (IdIHCS), Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Adjunct Researcher at the National Council of Science and Technology (CONICET) of Argentina. Coordinator of the Working Group “China and the Map of World Power” of the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO).

Author contributions

The author works about the contemporary transition in world power and its main tendencies: The crisis of US hegemony and the fractures in the Global North, the rise of China and the Eurasia continent, growing political-strategic contradictions around the redistribution or democratization of power and world wealth, the crisis and reconfiguration of the world economy, and disruptive processes in the Global South, with an especial focus in Latina America.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this context, when one of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summits led by China and Russia was taking place, the important British magazine The Economist published an article entitled “Pax Sinica”, which concluded with the following sentence: “China is not just challenging the existing world order. Slowly, messily and, apparently with no clear end in view, it is building a new one.” (The Economist, 2014).

2. ^In the aforementioned works that were published in 2016, the concept of “Fragmented World War” is used in an exploratory way. With the evolution of research, from 2018 to 2019, the concept of Hybrid World War is developed.

3. ^“Descartamos toda una generación por mantener un sistema económico que ya no se aguanta, un sistema que para sobrevivir debe hacer la guerra, como han hecho siempre los grandes imperios. Pero como no se puede hacer la Tercera Guerra Mundial, entonces se hacen guerras zonales. ¿Y esto qué significa? Que se fabrican y se venden armas, y con esto los balances de las economías idolátricas, las grandes economías mundiales que sacrifican al hombre a los pies del ídolo del dinero, obviamente se sanean”.

4. ^Zhao Lijian, spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, at the beginning of the Pandemic noted the possibility that it may have been the United States' military that brought the epidemic to Wuhan, making a direct connection to the Military Games in that city in October 2019, which included a delegation of 300 American military personnel. In the case of the conflict in Ukraine, Russia accused before the UN the United States of having financed a biological weapons program in Ukraine and claimed to have found evidence to that effect in Ukrainian laboratories. Moscow presented the documentation and demanded an international investigation.

5. ^The TPP was promoted by globalist forces starting in 2008 and was made up of 12 countries of Pacific Rim: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States.

6. ^Department of State (2011).

8. ^Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter (2015).

9. ^SCMP, July 14, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3093030/beijings-claims-south-china-sea-unlawful-says-us-secretary.

10. ^Kynge et al. (2022).

11. ^Barnes and Satariano (2019).

12. ^Beijing, for its part, consolidated its position in Hong Kong through a new national security law, passed in June 2020.

References

AP News (2022). China's Xi rejects “Cold War mentality,” pushes cooperation. Available online at: https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-health-lifestyle-business-world-economic-forum-78e063f62bfa1b36e91f6cbd5508d615 (accessed March 13, 2022).

Arrighi, G., and Silver, B. (1999). Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Arte (2021). 21st Century Warfare. Mapping the world (2021). Available online at: https://www.arte.tv/en/videos/103960-009-A/mapping-the-world/ (accessed March 10, 2022).

Aydintaşbaş, A., Dumoulin, M., Geranmayeh, E., and Oertel, J. (2022). Rogue NATO: The new face of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. 15th European Council on Foreign Relations. Available online at: https://ecfr.eu/article/rogue-nato-the-new-face-of-the-shanghai-cooperation-organisation/ (accessed on September 16, 2022).

Barnes, J. E., and Satariano, S. (2019). U.S. Campaign to Ban Huawei Overseas Stumbles as Allies Resist. The New York Times. Available online at:https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/17/us/politics/huawei-ban.html (accessed on Mach 17, 2019).

Clinton, H. (2011). Remarks at the New Silk Road Ministerial Meeting“, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Secretary of State, New York City, New York, Department of State. Available at: https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2011/09/173807.htm (accessed on September 22, 2011).

Congressional Research Service (2020). China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities. Background and Issues for Congress. Available online at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33153.pdf (accessed on August 24, 2020).

Department of Defense (2021). Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China. Available online at: https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF

Department of State (2011). Hillary Clinton: Remarks at the New Silk Road Ministerial Meeting. New York, NY. Available online at: https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2011/09/173807.htm (accessed September 22, 2011).

Fiori, J. L. (2018). “Epílogo - Ética cultural e guerra infinita,” in Sobre a Guerra, ed J. L. Fiori (Petrópolis: Vozes), 397–404.

Flint, C., and Taylor, P. J. (2018). Political geography: world-economy, nation-state, and locality. New York: Routledge, 2018. Seventh edition. London, United Kingdom: Routledge

Green, M., and Goodman, M. (2015). After TPP: the Geopolitics of Asia and the Pacific. Washington Q. 38:4, 19–34. doi: 10.1080/0163660X.2015.1125827

Hoffman, F. G. (2009). Hybrid Warfare and Challenges. Joint Force Quarterly, I. 52, 1st. Quarter. St.Louis, Missouri: National Defense University Press.

Jabbour, E., Dantas, A., and Vadell, J. (2021). From new projectment economy to Chinese embedded globalization. Estudos Internacionais: Revista De relações Internacionais Da PUC Minas 9, 90–105. doi: 10.5752/P.2317-773X.2021v9n4p90-105

Johnson, R. (2018). Hybrid War and Its Countermeasures: A Critique of the Literature. Small Wars Insurgencies 29, 141–163. doi: 10.1080/09592318.2018.1404770

Karaganov, S. (2018). The New Cold War and the emerging Greater Eurasia. J. Eur. Stud. 9, 85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.euras.2018.07.002

Kissinger, H. (2017). Remarks to the Margaret Thatcher Conference on Security. Available online at: https://www.henryakissinger.com/speeches/remarks-to-the-margaret-thatcher-conference-on-security/ (accessed on June 27, 2017).

Korybko, A. (2015). Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change. Moscow: Peoples' Friendship University of Russia.

Kynge, J., Yu, S., and Lewis, L. (2022). Fortress China: Xi Jinping's plan for economic independence. Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/0496b125-7760-41ba-8895-8358a7f24685 (accessed on September 19, 2022).

Legvold, R. (2014). Managing the New Cold War. Foreign Affairs. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2014-06-16/managing-new-cold-war (accessed January 26, 2022).

Li, Y. (2018). The greater Eurasian partnership and the Belt and Road Initiative: Can the two be linked?. J. Eur. Stud. 9, 94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.euras.2018.07.004

Liang, Q., and Xiangsui, W. (1999). Unrestricted Warfare. Beijing: PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House.

Mackinder, H. (1904). The geographical pivot of history. Geogr. J. 23, 421–437. doi: 10.2307/1775498

Merino, G. E. (2016a). Global Tensions, Multipolarity and Power Blocs in a New Phase of the Crisis of World Order. Prospects for Latin America. Geopolítica(s) 7, 201–225. doi: 10.5209/GEOP.51951

Merino, G. E. (2016b). El mundo después de Ucrania: nueva fase de la crisis global. en Merino y Rang, (coords.) ¿Nueva Guerra Fría o Guerra Mundial Fragmentada? (The world after Ukraine: new phase of the global crisis, Merino y Rang, (coords.) New Cold War or Fragmented World War?) Córdoba: Editorial Universitaria UNAM y Editorial UNRC

Merino, G. E. (2020). La guerra mundial híbrida y el asesinato de Soleimani” (The hybrid world war and the assassination of Soleimani. en Cuadernos del Pensamiento Crítico Latinoamericano (Buenos Aires: CLACSO). Available online at: https://www.clacso.org.ar/libreria-latinoamericana/libro_por_programa_detalle.php?campo=programaandtexto=19andid_libro=1826

Merino, G. E. (2021). New world geopolitical moment: The Pandemic and the acceleration of the tendencies of the contemporary historical-spatial transition. Estudos Internacionais: Revista De relações Internacionais Da PUC Minas 9, 106–130. doi: 10.5752/P.2317-773X.2021v9n4p106-130

Merino, G. E. (2022). La guerra en Ucrania, un conflicto mundial” (The war in Ukraine, a world conflict), Revista Estado y Políticas Públicas 19, 113–140.

Miller, C. (2022). Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology. New York: Scribner.

National Security Strategy (2017). White House. Available online at: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf (accessed March 28, 2022).

Nye, J. (2015). The Future of Force. Project Syndicate. Available online at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/modern-warfare-defense-planning-by-joseph-s–nye-2015-02 (accessed March 15, 2022).

PLA. (2019). China's National Defense in the New Era. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. Available online at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/specials/whitepaperonnationaldefenseinnewera.pdf

Poch, R. (2022). Chinese success determines military tension. CTXT. Available online at: https://ctxt.es/es/20221101/Firmas/41256/ (accessed on November 9, 2022).

Romano, S., and Tirado, A. (2018). Lawfare y guerra híbrida: la disputa geopolítica en América Latina” (Lawfare and hybrid warfare: the geopolitical dispute in Latin America), CELAG. Available online at: https://www.celag.org/lawfare-guerra-hibrida-disputa-geopolitica-america-latina/ (accessed on June 17, 2018)

Salgado, B. (2020). Hybrid War in South America: a definition of veiled political actions. Sul Global 1, 139–168. Available online at: https://revistas.ufrj.br/index.php/sg/article/view/31949

Scahill, J. (2008). Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army. New York: Bold Type Books.

Schoen, D., and Kaylan, M. (2014). The Russia-China Axis: The New Cold War and America's Crisis of Leadership. New York: Encounter Books.

Scott, D. (2012). US Strategy in the Pacific – Geopolitical Positioning for the Twenty-First Century. Geopolitics, 17, 607–628. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2011.631200

Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter (2015). Remarks on the Next Phase of the U.S. Rebalance to the Asia-Pacific," speech, U.S. Department of Defense. Available online at: http://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech-View/Article/606660 (accessed on April 6, 2015).

Suisheng, Z., and Guo, D. (2019). A New Cold War? Causes and Future of the Emerging US—China Rivalry. Vestnik RUDN. Int. Relat. 19, 9–21. doi: 10.22363/2313-0660-2019-19-1-9-21

Sun, D., and Elmahly, H. (2019). NATO vs. SCO: A Comparative Study of Outside Powers' Military Presence in Central Asia and the Gulf. Asian J. Middle East. Islamic Stud. 12, 4. doi: 10.1080/25765949.2018.1562594

The Economist (2014). Pax Sinica. China is trying to build a new world order, starting in Asia. Available online at: https://www.economist.com/asia/2014/09/20/pax-sinica (accessed February 15, 2022).

The White House (2015). Statement by the President on the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Available online at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/10/05/statement-president-trans-pacific-partnership (accessed April 10, 2022).

Trenin, D. (2014). Welcome to Cold War II. Foreign Policy. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/03/04/welcome-to-cold-war-ii/ (accessed March 20, 2022).

Zhao, H. (2018). Greater Eurasian Partnership: China's Perspective. China International Studies. Available online at: https://www.pressreader.com/china/china-international-studies-english/20180120/281500751662681 (accessed December 7, 2021).

Zhao, M. (2019). Is a new cold war inevitable? chinese perspectives on US–china strategic competition. Chin. J. Int. Pol. 12, 371–394. doi: 10.1093/cjip/poz010

Keywords: Hybrid World War, United States–China rivalry, historical-spatial transition, Asia Pacific, unipolarism–multipolarism

Citation: Merino GE (2023) Hybrid World War and the United States–China rivalry. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:1111422. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.1111422

Received: 29 November 2022; Accepted: 29 December 2022;

Published: 25 January 2023.

Edited by:

Javier Vadell, Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, BrazilReviewed by:

Ernesto Vivares, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences, EcuadorPatrick James, University of Southern California, United States

Diego Pautasso, Colégio Militar de Porto Alegre, Brazil

Copyright © 2023 Merino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabriel E. Merino,  gmerino@fahce.unlp.edu.ar;

gmerino@fahce.unlp.edu.ar;  gabrielmerino23@gmail.com

gabrielmerino23@gmail.com

Gabriel E. Merino

Gabriel E. Merino