Perceptions and Evaluations of Incivility in Public Online Discussions—Insights From Focus Groups With Different Online Actors

- Department of Social Sciences, University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany

Incivility in public online discussions has received much scholarly attention in recent years. Still, there is controversy regarding what exactly constitutes incivility and hardly any study has examined in depth what different participants of online discussions perceive as uncivil. Building on a new theoretical approach to incivility as a violation of communication norms, this study aims to close this research gap: In five heterogenous focus groups, different types of actors in online discussions, namely community managers, users, and members of online activist groups, discussed what they perceive as norm-violating and how these violations differ in terms of severity. Results suggest that incivility is a multidimensional construct and that the severity of different norm violations varies significantly. Although the actors share a relatively large common ground as to what they perceive as uncivil, several role-specific perceptions and individual evaluation criteria become apparent. Based on the results, a differentiated typology of perceived incivility in public online discussions is developed.

Introduction

The emergence of online discussions on social media and on the websites of news media has raised democratic hopes for participatory journalism and deliberation between users (e.g., Ruiz et al., 2011; Quandt, 2018). However, the gap between expectations and reality seems to be quite wide: “Can we please stop yelling at each other just because it's the internet?” asked one participant in this study. In fact, journalists, researchers, and politicians have raised concerns regarding the quality of online discussions and expressed anxiety about an increase of uncivil behavior, such as vulgarity, insults, and lies (Coe et al., 2014; Santana, 2014; Rowe, 2015; Boatright, 2019).

Media outlets and civil actors have taken various actions against uncivil behavior online. Media outlets have employed community managers to monitor comment sections, delete user comments they evaluate as severely uncivil, or publicly respond to comments to sanction users, foster communication norms, and improve the discussion atmosphere (e.g., Stroud et al., 2015; Ziegele et al., 2018; Friess et al., 2021). In addition to community managers, civil actors engage in online discussions. Individual users participate in online discussions, where they are exposed to and intervene against incivility (e.g., Kalch and Naab, 2017; Watson et al., 2019). Moreover, activist groups have emerged who collectively engage in comment sections to counter perceived incivility and to establish their norms of communication (Porten-Cheé et al., 2020; Ziegele et al., 2020).

While in practice various actors combat incivility online, in academia there is still debate regarding what incivility exactly is. Most scholars have agreed that incivility is a violation of norms, but they have disagreed about which norms constitute incivility (e.g., Muddiman, 2017; Chen et al., 2019). Moreover, various scholars have suggested that incivility is in the eye of the beholder (e.g., Herbst, 2010; Stryker et al., 2016; Kenski et al., 2017), yet most existing concepts of incivility ignore the subjective nature of the phenomenon. In our own research, we recently developed an integrative concept, approaching incivility as a perceptual construct and as a violation of several communication norms (Bormann et al., 2021). However, our proposed concept of incivility is based on theoretical assumptions, and it has not yet been applied empirically.

So far, few empirical studies have focused on what different participants in online discussions perceive as uncivil and how they evaluate types of norm violations in terms of severity. Moreover, previous studies in this field have typically focused on one type of incivility, such as sexism (Chen et al., 2020), or on one group of actors, such as community managers (e.g., Frischlich et al., 2019) or activists (Ziegele et al., 2020). Furthermore, most previous studies defined a priori types of incivility and applied quantitative methods (Stryker et al., 2016; Kenski et al., 2017; Muddiman, 2017) rather than exploring what the participants perceived as uncivil. Such an in-depth qualitative exploration is important in obtaining both a comprehensive and nuanced picture of perceived incivility in public online discussions and in formulating hypotheses regarding differences in perceptions of incivility.

Building on the theoretical approach of Bormann et al. (2021), this study aims to close this research gap by bringing together three types of actors in online discussions, namely community managers, activists, and users. In five heterogeneous focus groups, these actors discussed what they perceive as norm-violating in public online discussions and how these norm violations differed in terms of severity. Thus, the study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What do different actors in online discussions perceive as norm-violating, and where do they agree and differ in their perceptions of norm violations?

RQ2: How are norm violations evaluated in terms of their severity, and which evaluation criteria are apparent?

This paper begins by providing a review of conceptualizations of incivility in the literature and of previous empirical findings on perceptions of incivility. According to Bormann et al. (2021), incivility is conceptualized as a disapproved violation of one or several communication norms: information norm, modality norm, process norm, relation norm, and context norm. Based on these norms, the findings of the focus groups are presented, namely which violations the different actors perceive in online discussions, how these violations differ in terms of severity, and which evaluation criteria become evident. Based on the results, a perception-based typology of incivility in public online discussions is developed.

The contributions of this paper are two-fold: By bringing together three different types of actors in online discussions for the first time and inquiring their perceptions and evaluations of incivility, the study contributes to a better understanding and a more comprehensive picture of incivility. The study provides a detailed typology of incivility from the perspective of the actors involved in online discussions, which could be used in future research. For example, the typology could serve as the basis of a differentiated codebook for use in content analyses or in constructing standardized indicators of incivility that could be employed in future surveys. Moreover, hypotheses regarding what different actors of online discussions perceive as (mildly and severely) uncivil could be derived from the findings. Second, defining incivility from the perspective of the actors involved is not only relevant for research but also has practical relevance. This study can inform media outlets on what their users and online activist groups evaluate as inappropriate comments and when community managers are expected to intervene in discussions.

Concepts of Incivility

The definitions and operationalizations of incivility vary widely in the literature (for a detailed overview, see Bormann et al., 2021). One reason for such disparity, according to several authors, is that the definition of what is civil and uncivil behavior is highly subjective and thus elusive (e.g., Herbst, 2010; Coe et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019). It is, therefore, not surprising that scholars have offered different approaches to the phenomenon. Despite their differences, a common denominator in previous studies is that incivility has usually been conceptualized as a violation of norms (e.g., Muddiman, 2017; Jamieson et al., 2018; Hopp, 2019).

Numerous scholars have considered incivility as a violation of (deliberative) respect norms (e.g., Sobieraj and Berry, 2011; Anderson et al., 2014; Coe et al., 2014; Gervais, 2015). These studies have usually referred to theories of deliberative democracy, which, in essence, posit that political decisions should be the product of fair, rational, reciprocal, and respectful debate among citizens (Habermas, 1996; Gastil, 2008). Hence, incivility has been defined as disrespectful behavior that undermines deliberation. However, the operationalization of such disrespectful behavior has varied considerably across studies, ranging from insults to emotional displays (Sobieraj and Berry, 2011) and lying accusations (Coe et al., 2014).

A second line of research has conceptualized incivility as a violation of interpersonal politeness norms (e.g., Mutz, 2007; Chen and Lu, 2017; Rossini, 2020). These studies have referred to theories that focus on politeness norms in interpersonal interactions (Brown and Levinson, 1987; Fraser, 1990). Scholars who have applied this approach have equated incivility with impoliteness, and they have typically operationalized the construct as explicit violations of politeness norms, such as name-calling, yelling, or vulgarity (e.g., Mutz, 2007; Ben-Porath, 2010; Chen and Lu, 2017).

Third, scholars have argued that uncivil behavior moves beyond impoliteness and rather violates collective democratic norms (e.g., Papacharissi, 2004; Santana, 2014; Rowe, 2015; Kalch and Naab, 2017). According to Papacharissi (2004, p. 260), “[a]dherence to civility… ensures that the conversation is guided by democratic principles, not just proper manners.” Incivility is then understood as a violation of democratic norms and includes, for example, hate speech directed at marginalized groups, as well as threats to democracy and individual rights.

Finally, an increasing number of studies have considered the perceptual aspect of incivility and suggested approaching incivility as a perceived violation of several norms (e.g., Stryker et al., 2016; Muddiman, 2017; Chen et al., 2019). The current study follows these extended approaches. Specifically, it draws on the concept of incivility provided by Bormann et al. (2021), which will be outlined in the following section.

Incivility as a Violation of Communication Norms

Conceptualizations of incivility often build on norms, but scholars have focused in part on different norms when defining incivility. In addition, more and more studies have suggested that incivility is a perceptual construct and violates multiple norms (e.g., Stryker et al., 2016; Muddiman, 2017; Chen et al., 2019). Taking this into account, we recently developed a multidimensional concept of incivility that is based on the perceptions of participants involved in a political (online) discussion and on five communication norms (Bormann et al., 2021). The incivility concept is grounded in a theoretical framework on “cooperative communication” (Bormann et al., 2021, p. 6).

Cooperative communication is approached as a communication that enables cooperation between humans, and cooperation is seen as the foundation and elementary condition of all kinds of social and political relations, from partnerships to organizations, and democratic societies (Tomasello, 2008, 2009, 2019; Bormann et al., 2021). Understanding cooperation as one of the key elements in societies and cooperative communication as the means to enable it, Bormann et al. (2021) argue that the orientation toward cooperative communication is the fundamental principle in communication between humans, also in the context of public online discussions (see also Grice, 1975; Jeffries and McIntyre, 2010). However, drawing on different analytical approaches toward cooperation, communication, and norms (e.g., Grice, 1975; Tomasello, 2008, 2009, 2019; Lindenberg, 2015), Bormann et al. (2021) assume that cooperative communication is pre-suppositional and faces several challenges. To meet the requirements of cooperative communication and thus minimize the risks of failure, five basic communication norms have emerged. These communication norms are not prescribed but approached as the normative expectations of the participants involved in a respective communication toward the communication of other participants (e.g., Homans, 1974; Opp, 2015). The more participants adhere to these norms in their communications, the more likely it is that cooperative communication succeeds. For cooperative communication to succeed, communication participants should (1) provide adequate information (information norm), (2) mutually comprehend each other (modality norm), (3) reciprocally connect to each other's contributions (process norm), (4) treat each other respectfully to ensure mutual trust (relation norm), and (5) consider the specific communication context (context norm) (Bormann et al., 2021). The norms build on the central structural aspects of communication (Lasswell, 1948; Schaff, 1962).

The information norm is linked to the substantial aspect of communication and asks participants to provide the information that are necessary for cooperation. Put differently, communication participants presumably expect each other to only communicate what is informative in the communication situation (Bormann et al., 2021). This refers to the epistemic quality of information (i.e., honesty, telling the truth), to the relevance of information, and to the quantity of information (i.e., appropriate amount of information), and intersects with the conversation maxims quality, quantity and relation provided by Grice (1975). The information norm can be violated by, for example, conspiracy theories, lies and misleading exaggerations, which are types of incivility that previous incivility research has identified (e.g., Gervais, 2015; Muddiman, 2017).

The modality norm refers to the formal aspect of communication and expresses the normative expectation of participants to communicate comprehensibly in a discussion. Comprehensibility can be guaranteed, above all, by clarity, conciseness, and orderliness (Bormann et al., 2021). The modality norm thus intersects with the maxim of manner proposed by Grice (1975). Violations of the modality norm include, for example, sarcasm and ambiguity (e.g., Rowe, 2015; Hopp, 2019; Ziegele and Jost, 2020).

The process norm relates to the temporal aspect of communication and subsumes normative expectations regarding the connectivity of participants' contributions. Bormann et al. (2021) assume that participants expect each other to align their contributions within the thematic framework, to respond to each other in their contributions, and to be consistent in their contributions. The process norm can be violated by, for example, topic deviation and interruptions; types of violations that have been classified as uncivil in some previous studies (e.g., Stryker et al., 2016; Sydnor, 2018).

The relation norm builds on the social aspect of communication and expresses the normative expectation of communicating respectfully with other participants. This includes the expectation of being polite in accordance with the etiquette required in the communication, as well as of appreciating and showing deference to other communication participants (Bormann et al., 2021). The relation norm thus intersects with politeness approaches (e.g., Brown and Levinson, 1987; Fraser, 1990). Several previous incivility concepts and studies refer to types of incivility that can be classified as violations of the relation norm, such as insults and belittling directed at other participants, or vulgarity and obscenity (e.g., Mutz, 2007; Sobieraj and Berry, 2011; Anderson et al., 2014; Coe et al., 2014; Chen and Lu, 2017; Rossini, 2020).

Finally, the context norm refers to the spatial aspect of communication and asks participants to consider the specific context. In terms of incivility, the context in the present study is defined as public political online discussions in liberal democracies. Bormann et al. (2021) assume that the participants in such discussions expect each other to consider liberal-democratic principles in their contributions, such as the freedom of speech and the protection of minorities (e.g., Coppedge et al., 2011). Violations of the context norm include types of incivility that particularly Papacharissi (2004) has operationalized, such as stereotyping and discriminating social groups, and threats to individual rights and democratic values (see also Rowe, 2015; Stryker et al., 2016; Kalch and Naab, 2017; Hopp, 2019).

Basing the concept of incivility on these five communication norms combines various concepts from the literature into an integrative framework (e.g., Papacharissi, 2004; Coe et al., 2014; Stryker et al., 2016; Chen and Lu, 2017; Muddiman, 2017; Hopp, 2019; Rossini, 2020). Based on the five norms and in line with previous research, incivility is defined as communicative acts in public online discussion that participants disapprove of as violating one or several of the five communication norms. Because norm violations can also be tolerated under specific circumstances, the participants' disapproval presupposes that a violation of the communication norms is recognized and classified as worthy of sanction (Bormann et al., 2021, pp. 16-17).

As this theoretical approach has not yet been applied empirically, the question is whether the different participants of online discussions actually perceive violations of these five norms as uncivil and how the violations differ in severity. Before answering this question, however, we take a look at what incivility research knows so far about perceptions of incivility and its levels of severity in general and by different online actors in particular.

Perceptions and Evaluations of Incivility

Overall, few previous studies have examined perceptions of incivility. Muddiman (2017), for example, developed a two-dimensional model of perceived incivility consisting of “personal-level incivility” (p. 3183) and “public-level incivility” (p. 3183). Personal-level incivility includes, among others, insults, obscene language, and emotional displays, which can be classified as violations of the relation norm in terms of our concept of incivility. Public-level incivility pertains to, for example, non-public acts, such as secretly taking foreign donations, ideological extremity, and a lack of comity, which can be categorized as violations of the political context norm in Bormann et al.'s (2021) concept. In two experiments, Muddiman (2017) investigated individuals' perceptions of these a priori defined norm violations in scenarios of interactions between politicians. Her findings suggest that personal- and public-level incivility are distinct concepts, and both are perceived as uncivil. Moreover, personal-level incivility was evaluated as more uncivil than public-level incivility.

Similarly, Stryker et al. (2016) examined perceptions of various types of norm violations. They provided 23 items that each described a potential type of incivility and asked respondents to rate how uncivil these behaviors were in a political discussion among political elites and citizens. Most of their study participants perceived all these types as at least somewhat uncivil, and threatening or encouraging harm, as well as slurs, were predominantly evaluated as very uncivil. Furthermore, the researchers found three analytically distinct dimensions of incivility: “utterance incivility” (Stryker et al., 2016, p. 547) referred to insults, vulgarity, and slurs, among others, which can be classified as violations of the relation norm according to the Bormann et al.'s (2021) concept. “Discursive incivility” (Stryker et al., 2016, p. 547) consisted of detraction from inclusive and reasoned debate, which can be categorized as violations of the political context norm. Finally, “deception” (Stryker et al., 2016, p. 547) includes lying, misleading, and exaggerating, which can be defined as violations of the information norm (Bormann et al., 2021). In addition to a multidimensional model of incivility, the results indicated a broad consensus concerning types of speech that are considered uncivil. It is worth noting, however, that Stryker et al.'s (2016) sample was a quite homogeneous sub-group of students.

Muddiman (2017) and Stryker et al. (2016) did not explicitly focus on incivility in online discussions among ordinary citizens, whereas Kenski et al. (2017) examined perceptions of five potential types of incivility in users' comments. Their findings were in line with the other studies, suggesting that all types were perceived as at least somewhat uncivil and that distinct types of norm violations were evaluated differently: Name-calling and vulgarity were rated as more uncivil than lying accusations, aspersions, and pejorative language. However, unlike a widespread consensus (Stryker et al., 2016), the results of Kenski et al. (2017), who surveyed a larger population, demonstrated that perceptions of incivility were not uniform. Different individual characteristics, such as gender, personality traits, and ideology, were found to affect perceptions of incivility. In particular, being female was consistently associated with higher ratings of incivility (Kenski et al., 2017).

Furthermore, recent studies have focused on the perceptions of online actors. For example, Ziegele et al. (2020) surveyed members of the German activist group #Iamhere (English translation of #ichbinhier) and asked them to rate five types of comments that included either name-calling, lies, threats, antagonistic stereotypes, or rejections of democracy in terms of severity, specifically, “harmfulness” (p. 740). While name-calling and threats against other participants can be classified as violations of the relation norm, lies pertain to violations of the information norm, and antagonistic stereotypes as well as rejections of democracy can be considered violations of the context norm, according to Bormann et al.'s (2021) concept. The activists of #Iamhere consistently evaluated all five types as highly harmful, or in other words, as severely uncivil.

In addition, some in-depth interview studies explored perceptions and evaluations of incivility by journalists and community managers. Frischlich et al. (2019) examined community managers' perceptions of (strategic) “dark participation” (p. 2014), which refers to intentional violations of the information or relation norm, according to Bormann et al. (2021). This included, for example, trolling, spreading false information, and attacks against communication participants. Frischlich et al. (2019) found that different forms of dark participation were perceived as uncivil, while evaluations of their severity differed. Specifically, they identified four types of community managers who differed in their evaluations of dark participation from relatively unproblematic and mild to highly harmful. Chen et al. (2020) conducted in-depth interviews with female journalists regarding their experiences with online sexism, which can be defined as a violation of the context norm. Contrary to Frischlich et al. (2019), the results indicated similar evaluations and experiences among the journalists. They consistently evaluated sexism as highly harmful, and the majority reported having experienced it frequently, including sexist criticism of their work, misogynistic attacks, and sexual violence (Chen et al., 2020).

In summary, the results of various studies suggest that violations of multiple norms constitute perceived incivility and that different types of incivility are evaluated as not equally harmful. The results were ambiguous regarding consensus or dissent in perceptions and evaluations of incivility. Moreover, since the studies reported predominantly operationalized incivility a priori and since their operationalizations of incivility differed considerably, the results are comparable only to a limited extent. Furthermore, most of the studies used quantitative methods and qualitative in-depth explorations are scarce. Finally, only a few studies focused on user comments and the perceptions of different online actors.

It can be assumed, however, that perceptions of different online actors vary to some extent. Due to their different roles, the actors involved in online discussions might have varying expectations of the communication of other participants, and thus different norms might be salient and violations might be perceived and evaluated differently. I distinguish three types of actors in public online discussions based on their professional or lay role (for a similar approach, see Porten-Cheé et al., 2020; Friess et al., 2021). (1) Community managers are hired and paid by a certain news medium and thus act in a professional, journalistic role in online discussions. They represent the media company, which sets certain norms and rules for discussions on their websites and social media sites, and which has to protect itself legally (Stroud et al., 2015; Ziegele et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2019; Friess et al., 2021). Accordingly, they follow specific instructions on how to monitor comment sections, how to evaluate norm violations, and how to respond to norm violations. (2) Activists, on the other hand, do not act on behalf of a medium and thus do not perform a professional role. Nevertheless, online activist groups who combat incivility in public online discussions, such as #Iamhere or No Hate Speech Movement, can be described as semi-professional actors because they organize themselves into a collective, share common collective goals, and act strategically and concerted (Ley, 2018; Ziegele et al., 2020; Friess et al., 2021). Consequently, activists represent the collective's norms in online discussions and act on behalf of their group and thus follow specific group norms and instructions on how to monitor comment sections, evaluate norm violations, and react to them (Ziegele et al., 2020; Friess et al., 2021). (3) Finally, ordinary users engage in online discussions as lay persons. Ordinary users here refer to members of the audience or community of a news medium's comment section on its website or social networking sites who read and/or write comments (Ziegele, 2019; Friess et al., 2021). Contrary to community managers and activists, ordinary users do not act as a representative of a medium or as a member of an activist group and are thus independent of the norms set by an institution or organization (e.g., Porten-Cheé et al., 2020; Friess et al., 2021). However, previous studies suggested that users do not enter online discussions just like that, but pursue certain motives and have specific expectations toward the behavior of other participants (Diakopoulos and Naaman, 2011; Springer et al., 2015; Engelke, 2020), which in turn could have an impact on the perceptions and evaluations of norm violations. Overall, therefore, the different roles of the participants in online discussions could lead to varying perceptions and evaluations of norm violations. Whether and which differences result from these roles have not yet been determined.

Method

To answer the research questions, a qualitative semi-structured focus group methodology was employed. Compared to other methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups are particularly suitable to elicit a wide range of views on specific study issues, uncover group norms, and get insights into processes (Hennink et al., 2020). Moreover, in focus groups, the contributions of other participants, confrontations with other views, and group dynamics can stimulate reflection, and deep-seated perceptions and evaluations become salient. Focus groups also represent a more social, natural setting compared to other research designs (e.g., Krueger and Casey, 2015; Hennink et al., 2020). Hence, focus groups offered important benefits for investigating incivility in online discussions. They allowed us to bring together different groups of actors, identify a wide variety of perceived norm violations in public online discussions, derive shared and diverging perceptions and evaluations of norm violations, and learn about the evaluation process of norm violations.

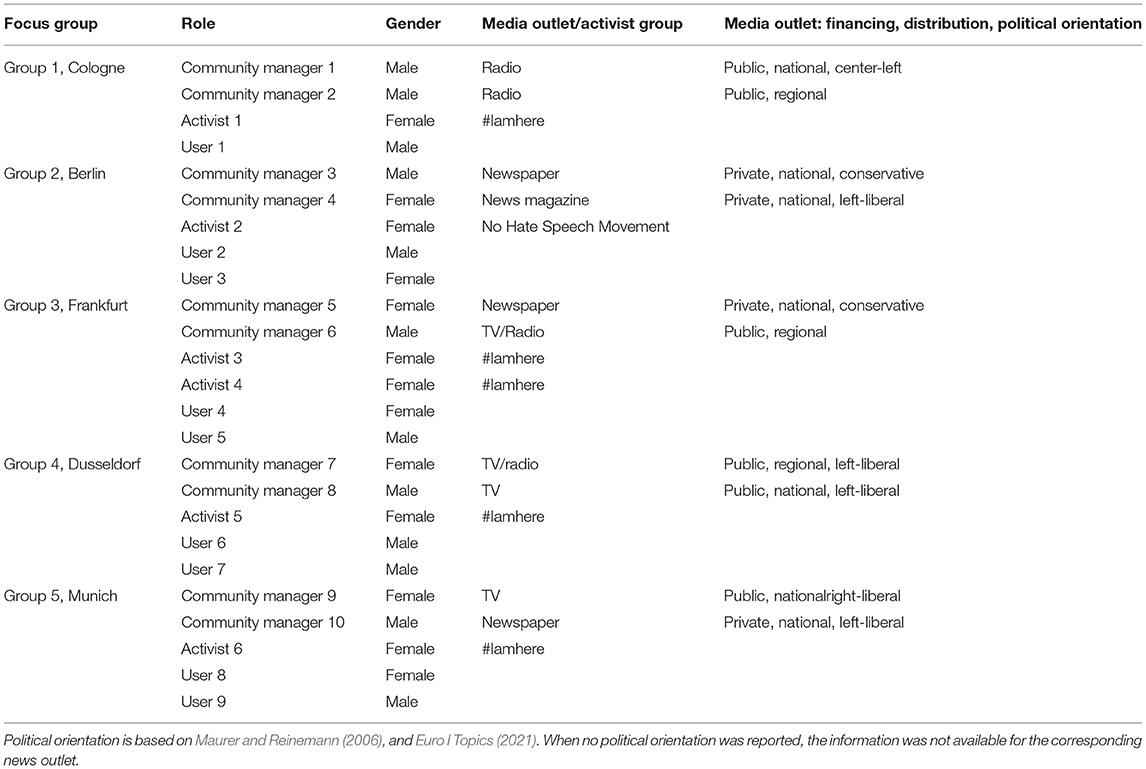

Five heterogeneous groups with representatives of three types of actors in online discussions were conducted: (1) community managers of public, private, regional, and national news media, including broadcasting and print (n = 10); (2) ordinary users (n = 9); and (3) members of the activist groups #Iamhere and No Hate Speech Movement (n = 6). The sample comprised 25 participants, and each group included four to six participants. In each focus group, at least one representative of each type of actor was represented (see Table 1). We sought a cross-section of participants that were diverse in gender, age, and educational background in order to obtain a wide range of perceptions and evaluations of norm violations online. Of the 25 participants, the majority identified as female (n = 13), and they ranged in age from 24 to 58 years. Unfortunately, diversity in educational background was not achieved because most participants were well-educated with a high school diploma or a university degree; only two participants had a lower educational level.

The participants, which included community managers, users, and activists, were selected using a multi-step procedure.

Community Managers: Because we sought community managers working at different media outlets, we first identified all German news outlets that had their own websites and comment sections and/or a presence on social media. In the second step, we included only media outlets that visibly moderated online discussions. We then contacted these media outlets, and based on an online survey, we selected only community managers who indicated that they regularly moderated online comments.

Users: We sought users who regularly participated in public online discussions. To identify and recruit them, we contacted Facebook's “top fans” of different media outlets. “Top fans” are active users of a news media site on Facebook. Additionally, we initiated a call for participation on various social media channels. Based on an online survey, we selected only users who indicated that they regularly read or wrote comments in online discussions.

Activists: The first step was to identify Germany's largest activist groups that engaged against online incivility. The largest was #Iamhere, which had around 45,000 members (Ley, 2018). Another was the No Hate Speech Movement, which is an international social movement that seeks to combat incivility online. In the second step, we contacted these groups and selected only members that regularly engaged in online discussions.

The focus groups were conducted face-to-face in November 2019 in five different German cities (see Table 1). Two researchers moderated the focus groups, the duration of which was ~2 h. A semi-structured discussion guide was developed based on common guidelines (e.g., Kuckartz, 2014; Krueger and Casey, 2015; Hennink et al., 2020). It included open questions and stimuli material on perceptions and evaluations of norm violations in online discussions. Regarding RQ1, according to the definition of incivility in this study, a communicative act is uncivil only if a norm violation is recognized and considered sanction worthy (see p. 7). We considered this two-stage presupposition in our operationalization. However, because questions in discussion guides should be clear, simple, avoid specialist/professional terminology, and phrased in an informal conversational style using colloquial language that participants can easily relate to (Hennink et al., 2020, p. 147), we decided to not pose explicit questions about “sanction worthy norm violations” or “uncivil comments” because these terms are not used colloquially in German. Instead, we followed the required question design (Hennink et al., 2020) and asked, for example, about “negative experiences in online discussions,” “inappropriate comments,” and “harmful comments.” Regarding RQ2, an innovative method was applied to explore and compare the severity of different types of norm violations. We provided various stimuli consisting of real comments which included different types of norm violations that were drawn from different platforms and covered a variety of topics. The participants were asked to discuss these comments and other examples of their individual online experiences, collectively rank them from mild to harmful, and justify their choices. Based on these discussions, it was possible to determine both the severity and the evaluation criteria applied by the different actors in our study. The discussion guide and moderation techniques were pretested using an additional focus group.

In the main study, the five focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed without paraphrasing, following the rules of a detailed transcription guide (e.g., Kuckartz, 2014). In the interest of privacy, the participants' names, ages, and news outlets were withheld. Following the transcription, the data were analyzed using thematic qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz, 2014). The overarching categories were developed deductively based on the theory and the research questions. After initial text work, the entire material was coded with the overarching categories. Based on the coded transcripts, subcategories of each overarching category were developed inductively. Finally, all transcripts were recoded using the differentiated category system, which entailed three main topics of interest: (1) perceived norm violations; (2) severity of norm violations; and (3) evaluation criteria.

Results

RQ1: What Do Different Actors in Online Discussions Perceive as Norm-Violating, and Where Do They Agree and Differ in Their Perceptions of Norm Violations?

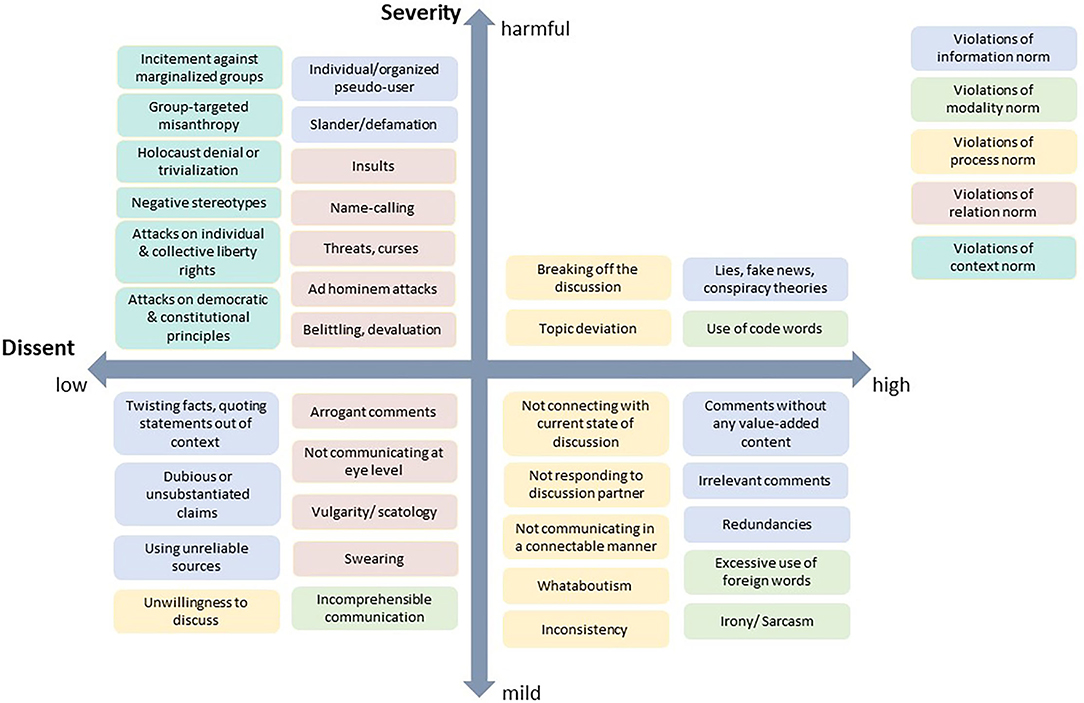

The actors perceived and reported various violations of all five communication norms, which supports a multidimensional model of incivility. Overall, the findings indicate a large common ground among the actors regarding their perceptions of incivility. However, some differences emerged. While violations of the context and relation norm were consistently perceived as uncivil by all actors, their perceptions of the information, modality, and process norms varied. In the following, I will briefly describe what was perceived as a violation of each norm and by whom. Based on the results, I developed a typology of perceived incivility in public online discussions (see Figure 1). The typology illustrates and summarizes the results from the qualitative content analysis reported in detail in the following. For this purpose, in a first step, the different types of violations perceived by the actors were assigned to the corresponding communication norm (RQ1). Afterwards, the individual types of norm violations were classified along the dimensions (1) dissent between the actors, that is low or high (RQ1), and (2) evaluated severity of the norm violation, which is mild or severe (RQ2). Because some aspects were abstracted in the typology, Supplementary Table 1 provides a detailed overview of all reported norm violations and severity evaluations, as well as the actors who reported the norm violations.

Violations of the Information Norm: Informational Incivility

According to Bormann et al. (2021), the information norm asks participants to communicate only what is informative in the respective discussion (see Section Incivility as a Violation of Communication Norms). The actors in the focus groups perceived many violations of the information norm, particularly regarding misinformation and disinformation. All actors had frequently encountered fake news, lies, and conspiracy theories in online discussions, and they perceived that such content was mostly spread by so-called “Reich citizens,” “tinfoil hat wearers,” anti-vaxxers, and climate change deniers. The actors complained that they were increasingly confronted with “alternative realities” (User 1) and a “post-factual age” (Community manager 2), in which facts were not recognized and science and high-quality media were declared untrustworthy by some users. In particular, the users and activists complained that it was often impossible to find shared knowledge. As a result, there was no shared basis for discussion, and the discussion failed. Activist 4 described the following:

This means we have a completely different truth or…public and that is a huge problem. If I say, “the book has a yellow cover,” then for us it's just a book with a yellow cover. But we come across people who say, “but the cover is blue.” And then you actually can't discuss.

Beyond this, the participants perceived that the information norm was violated when comments contained dubious, unsubstantiated claims or unreliable sources, or when information was taken out of context to support certain opinions. Community manager 9 provided examples of users' misuse of likes to violate the information norm, which is why the community management rarely likes comments anymore:

So first they [users] write something in our comment section, we like it, and then they edit their comment so that it says something totally different. And then that crops up as a screenshot in a different discussion. And underneath it, it says that “[medium] likes it.”

In addition to the quality of communicated information, especially the users and activists perceived norm violations regarding quantity and relevance, such as comments without any value-added content in a discussion, or “phrases, hollow words, and clichés” (User 9). Moreover, the users complained about insufficient information regarding moderation actions by community managers, particularly regarding which comments were deleted and why they were deleted. The community managers agreed but emphasized that they did not have the resources to justify each moderation action.

Violations of the Modality Norm: Formal Incivility

According to Bormann et al. (2021), the modality norm asks participants to communicate comprehensibly in the respective discussion (see Section Incivility as a Violation of Communication Norms). The actors in the focus groups perceived only a few violations of the modality norm in online discussion. Moreover, violations of the modality norm were perceived quite differently. For example, while some participants condemned irony and sarcasm as uncivil in almost all situations, others found that ironic comments were entertaining. All activists perceived irony and sarcasm as inappropriate in public discussions online, while some users and community managers considered it appropriate as long as it was at eye level and clearly communicated that it was ironic or sarcastic. However, when community managers were ironic or sarcastic, users always perceived it as inappropriate, which indicates role-specific expectations.

Similarly, the excessive use of foreign and specialist words that impeded the understanding of comments, is controversial among the actors. User 9 said that he deployed such “overblown explanations” as a form of counter speech. Other actors perceived this as uncivil. The community managers in particular emphasized that simple language should be used to avoid excluding certain educational groups from the discussion. Another user countered that he did not feel that he was taken seriously when community managers posted comments that were too simplistic.

Incomprehensible communication, in general, was categorized as a norm violation by all actors. However, differences emerged regarding what the participants perceived as incomprehensible. One user, for example, complained about youth slang and the use of emoticons, while several others, especially the younger participants, found them perfectly understandable:

And then you get these laughing, rolling Smileys. Where I think, “Why's he laughing now? What does he mean?” (User 2)

Furthermore, the community managers reported that some commenters used dog whistle tactics to violate the modality norm. These tactics refer to communication in which code words and ambiguous statements are purposely employed to circumvent algorithms, make subtle insults, or spread an ideology that is primarily recognized by its supporters.

Violations of the Process Norm: Processual Incivility

According to Bormann et al. (2021), the process norm asks participants to connect their contributions in the respective discussion (see Section Incivility as a Violation of Communication Norms). Violations of the process norm were discussed less controversial than violations of the modality norm among the different actors in the focus groups; however, role-specific perceptions again emerged. In particular, the users and activists perceived various violations of the process norm. The most frequently mentioned violation was topic deviation in online discussions. Activist 4 described the following:

It already starts with the theme being completely passed by…. [T]oday, it was about the new wave of refugees which is now coming to us via the new Balkan route, but it once again turned into a discussion only about homeless persons. For me, things like that are just not conducive to the discussion. You don't get anywhere like that.

Furthermore, the actors often mentioned that they experienced more monologs than dialogues in online discussions and that users often showed no interest in exchange. This includes not responding to the discussion partner and not communicating in a connectable manner. The users also pointed out that they perceived a norm violation when community managers did not respond to their comments and questions individually, but wrote either no answer or posted a prefabricated answer. Breaking off a discussion was also perceived as uncivil behavior, especially by the users. User 5 expressed the following:

The worst thing for me is when the other user just goes away. Because if someone is sitting opposite me face-to-face, it is discussed through to the end. Then it doesn't happen that the person goes away…. [O]ne enters into an argument at the moment, and this is also an obligation.

Violations of the Relation Norm: Personal Incivility

According to Bormann et al. (2021), the relation norm asks participants to communicate respectfully with each other (see Section Incivility as a Violation of Communication Norms). Regarding violations of the relation norm, the results showed a large common ground among the different actors. In general, the actors complained about a lack of empathy, humanity, and politeness in online discussions, which they suspected was due to missing social cues. Specifically, the participants perceived the relation norm to be violated when contributions no longer targeted the issue but individual participants and violated their dignity. Activist 2 demanded that the limits of what could be said should not be exploited:

The term “limits of what can be said” really bothers me, because the concern isn't with what can still be said, but rather simply that we have a basic consensus of “we will treat each other with respect.”

All actors said that insults were the most frequent norm violation and emphasized that it was irrelevant whether the insults were targeted at themselves or at other participants; any insult was perceived as harmful. However, there was a heated discussion among the participants in the focus groups about what constituted an insult. The actors concluded that this decision was very much in the eye of the beholder. Community managers, for example, explained that in the case of subtle, implicit insults directed at a user, they often had difficulties determining whether the user felt insulted or not and whether they should intervene by imposing mild or strong sanctions.

Explicit insults often took the form of name-calling and swearing. The participants gave diverse examples of such insults in online discussion: “idiot” (Activist 1); “asshole” (User 9); “jerk” (Community manager 1); and “motherfucker, swine” (Community manager 5). Such insults were accompanied by vulgar remarks and scatology, which were perceived as inappropriate regardless of the target.

Moreover, the actors reported frequent vilification, devaluation, accusations of incompetence, arrogant comments, and that communication did not occur on an equal footing. The users and activists experienced this mainly in discussions where they did not agree with other discussion participants. Degradation was then employed to bolster an argument, such as claiming that the discussion partner lacked credibility, such as “You've got no idea anyway and you're just too stupid” (Activist 3). Community managers also experienced condescending remarks, such as “the whole social media editorial team should be fired, you're complete morons, you're doing a bad job!” (Community manager 1) as well as degrading remarks, such as the community managers were “interns” (Community managers 2 and 4). In particular, the community managers of public service media reported having experienced many condescending remarks and insults, which they had to endure and usually did not sanction in order to avoid censorship accusations, whereas attacks against users were always strictly sanctioned.

All actors in the focus groups perceived that death threats, threats of violence, curses, and wishing death or a similar fate on other participants constituted the most serious violation. In all media, explicit threats led to strict sanctions, however, these sanctions were not always accepted by the perpetrators. Community manager 9 described the following:

[We blocked a user] because he wanted to bury people on our page alive and wished them a quick death at the next traffic light…. He sued us for this and then said in court, “If you dug people up within 30 minutes, they'd still be alive anyway, so it wasn't a death threat.” And the court agreed with us for blocking him.

Violations of the Context Norm: Anti-democratic Incivility

According to Bormann et al. (2021), the context norm asks participants to consider the respective context of the discussion, and in public political communication, the participants presumably expect each other to consider liberal-democratic principles in their contributions (see Section Incivility as a Violation of Communication Norms). In the focus groups, violations of the political context norm were the most frequently mentioned by all actors. Moreover, a large common ground was revealed regarding what were perceived as violations of the context norm. Generally, the actors expect one another to consider the context of communication. They perceived a norm violation when, for example, users ignored the fact that discussions on social media were public discussions and that the internet was not a legal vacuum. The actors reported that the tone was frequently reminiscent of private conversations with friends in the pub, and the communication was uninhibited. Additionally, community managers in particular perceived norm violations when discussion participants were not concerned about the norms of the respective forum, the netiquette, and when users did not accept that the medium set the rules for its comment section. Moreover, the actors reported concrete violations of liberal-democratic principles, which are discussed in the following subsection.

Hate Speech, Discrimination, Incitement

The most frequently mentioned norm violations, compared with the other four norms, fall into this category. The actors reported hate speech that occurred in diverse themes, such as immigration, religion, climate, vaccination, and veganism. Hate speech was reported as being directed at LGBTQIs, refugees, persons with (mental) illnesses, and other marginalized groups. The most frequently perceived by all actors were racism, xenophobia, and islamophobia. Such hostility was often reported to be combined with false claims, such as in the following examples from online discussions provided by User 4 and User 9:

The Arabs just want to put up minarets here (User 4); Islam destroys everything! Germans are being replaced! N-word only come over here to rape our women. (User 9)

In all focus groups, sexism was the most frequently reported by the female participants. The female community managers said that their competence was often called into question in online discussions. Users and activists reported sexist attacks and even threats of rape. Above all, they had experienced sexism in discussions about polarizing issues and when their opinion was contrary to that of male discussion participants:

Especially when it's about this refugee issue. And if, as a woman, you comment, then very often it's countered with, “you're just a fuck-starved old woman who can't get any in the normal way so you're glad if a few young ravenous… migrants “fresh meat” get here, so that you sex-starved old woman get the chance to be fucked. (Activist 3)

Furthermore, all actors perceived incitement and threats of violence toward marginalized groups in public online discussion. One female community manager also described incitement to cyberviolence, such as shitstorms or cyberbullying:

[Name] has a very successful Twitter account, with which he regularly hounds women with little Twitter accounts. And then they just sink, they're in the middle of a shitstorm and can't tell up from down…. [T]he more closely knit such a community is, the more evil their attack can be. (Community manager 4).

Holocaust denial and trivialization, as well as sympathizing with Holocaust deniers, were also perceived as grave norm violations.

Attacks on Individual and Collective Liberty Rights

The actors perceived it as norm-violating in online discussions when participants' individual liberty rights were restricted, such as when freedom of speech was restricted and when freedom of religion was called into question or participants were denied the right to practice their religion, which often had an anti-Semitic or Islamophobic background. With regard to the restriction of freedom of speech, users and activists reported experiences in which the participants were silenced by pressure, marginalization, or blocking:

Nothing is worse than when participants are muzzled… because this damages our democracy and leads to a dictatorship. (Activist 1).

At the same time, the actors said that the boundaries of freedom of speech were often disregarded, and illegal statements were made under the guise of freedom of speech:

The perpetrators always say, “But it's freedom of speech.” And then vocab is flying around that has nothing to do with it. (Community manager 3).

Attacks on collective liberty rights were also described. For example, according to the community managers, the freedom of the press was often doubted. Public service media were labeled as “system media,” “state broadcasting,” or “GEZ [TV license fee] mafia” (Community managers 1, 2, 9). Private media were also accused of being “left-green filthy eco propaganda” and were labeled as “lying press” or “gaps press” (Community manager 5).

Attacks on Democratic and Constitutional Principles

The actors perceived it as inappropriate when the participants in a public online discussion questioned democracy, the rule of law, and promoted or glorified fascism. Furthermore, the actors in all focus groups reported frequent violations of pluralism and democratic deliberation, the public and fair exchange of arguments. Users and activists perceived a lack of fairness and tolerance between different political camps. Contrary but legitimate political opinions were often not tolerated, and a specific political agenda was pursued, such as in the case of “troll armies.”

Attacks on constitutional principles were also mentioned, although more rarely than other violations of the context norm. For example, the actors described threats against the government or institutions in Germany (e.g., users communicating a desire to overthrow the government by force) and comments in which the sovereignty of the state or the constitution of Germany was called into question:

This is someone who doesn‘t recognize the German constitution…. And even if I would say that this is not as harmful as a personal threat, I actually also find it very bad. (Community manager 4)

In summary, the different actors perceived various violations of all five communication norms, which supports a multidimensional construct of incivility. Moreover, although the online actors in the present study shared a relatively large ground regarding what they perceived as uncivil, some discrepancies emerged, especially regarding perceived violations of information, modality, and process norms. In the following section, I focus on how and with which criteria the norm violations were evaluated in terms of their severity.

RQ2: How Are Norm Violations Evaluated in Terms of Their Severity, and Which Evaluation Criteria Are Apparent?

Severity

With regard to the severity of norm violations, the results were similar to those of RQ1 (see Figure 1 for an overview). The actors shared a certain common ground regarding which norm violations were mild and which were more severe. As Figure 1 illustrates, in all focus groups, the actors tended to evaluate violations of the relation and context norms as worse than violations of the information, modality, and process norms.

However, the findings also showed some role-specific differences. In particular, users and activists evaluated specific types of informational incivility as being very harmful, similar to personal and anti-democratic incivility. Specifically, fake news, lies, and conspiracy theories were evaluated differently. Users and activists considered them very harmful, and they did not want to see them in public discussions. Thus, they expected community managers to perform strict sanctions, for example by deleting such comments or blocking the perpetrators. On the contrary, community managers, particularly those of public media, argued that many lies are covered by freedom of speech and that they cannot justify severe sanctions. Moreover, because of limited resources, the community managers cannot perform fact checks on each comment, which they would have to do in order to remain neutral. Community manager 8 gave further reasons:

We then usually answer, “According to the current state of science, you are wrong.” But it's because, on the one hand, we think that if we delete it, we'll just make the situation worse. Because they already believe that we are censoring and everything. And on the other hand, there is the tiny, tiny possibility that maybe 99% of the climate scientists are wrong and all the models are wrong. And that's why we're a bit more open about things like that,…which are not value-based, but maybe more factual and scientific.

Regarding processual incivility, leaving the discussion as a specific type was also evaluated differently by the actors: Several users rated it as a very harmful violation when their communication partners broke off the discussion, while activists and community managers evaluated it more mildly. Similarly, users and activists evaluated topic deviation as a severe norm violation, and they expected community managers to intervene when it occurred in online discussions. The community managers also deemed it inappropriate but not as severe to always engage against it (see Figure 1).

In addition to differences among the actors, minor differences were expressed within the groups of actors. For example, community managers of public service media showed a higher tolerance level in some cases than community managers of private media. However, they emphasized that these tolerance limits were professionally applied in their function as representatives of a certain medium. Particularly in the case of public service media, community managers stressed that they have to provide a discussion platform for everyone where even extremely borderline/marginal opinions and contributions must be tolerated, and the law is the benchmark. Moreover, slight differences emerged with regard to gender and other individual characteristics within the groups of actors; for example, the female participants tended to rate norm violations more severely than the male participants did. This was particularly evident in the case of norm violations directed at (groups of) people.

Differences in severity were also apparent in different types of violations of a particular norm. For instance, all actors considered spreading disinformation worse than using unreliable sources. Insults were evaluated as more harmful than swearing or vulgarity. Violations of the context norm were consistently evaluated as severe and often as a threat to democracy, particularly in the case of hate speech and discrimination against minorities. Users and activists even suggested that they rated attacks against groups to be worse than insults direct at themselves (i.e., personal incivility). Furthermore, the types also showed differing levels of severity: In some cases, a mild insult was evaluated as less severe than an extreme deviation from a theme or breaking off a discussion.

Evaluation Criteria

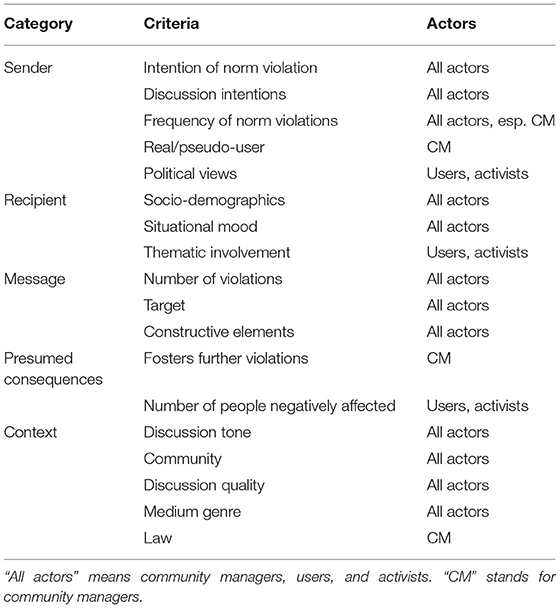

To evaluate the severity of norm violations, various criteria play a role that can be assigned to the categories of sender, recipient, message, presumed consequences, and context (Lasswell, 1948) (see Table 2).

The first is the sender of a comment. The actors attributed various characteristics to the sender, which seemed to affect their evaluations of the norm violation. The evaluation of the norm violation was worse when the actors perceived it to be intentional. If it was foreseeable that the sender was pursuing a particular agenda (e.g., troll armies), norm violations were evaluated as being very serious. Moreover, comments were evaluated as particularly severe if the sender's apparent aim was merely to violate norms. As long as the actors attributed to the sender the intention to discuss, or in other words, a willingness for discussion was discernible, norm violations tended to be evaluated less severely. The frequency of the sender's norm-violating behavior also played a role in the evaluation process. Community managers, for example, reacted to repeat offenders by imposing stronger sanctions because they presented a danger to the community. Users and activists also usually evaluated “one-time slip-ups” (User 9) as less severe. Moreover, in terms of sanctions, community managers distinguished between real users and fake accounts, and the latter was more strongly sanctioned. Users, by contrast, emphasized that the “hurtful comments are just as seriously hurtful whether it is a fake person or not” (User 5). Lastly, particularly for users and activists, the political views attributed to the sender played a role. If a comment contradicted an actor's political view and contained a norm violation, it was more likely to be evaluated severely. By contrast, in their professional role, community managers have to remain politically neutral and try to judge the norm violation independently of political disagreement.

Furthermore, the individual characteristics of the recipient were apparent in the evaluation of severity. The findings showed that different socio-demographic characteristics, such as age and gender, affected the evaluation process: Older and female participants in the focus groups tended to rate different types of norm violations more severely than younger participants and males did, regardless of the type of actor. In addition, the actors reported that their evaluations depended on their situational mood. If they were in a good mood, they tended to rate norm violations less severely. Community manager 10 said that he sanctioned less when he was “fresh back from vacation.” Moreover, the findings showed that thematic involvement played a role, especially for users and activists. When they discussed a topic that was important to them and in which they were involved, they tended to rate norm violations more seriously. The community managers emphasized their professional neutrality and that they tried to evaluate norm violations independently of their personal involvement. However, generally in the case of critical or polarizing issues, the tolerance seemed to be lower among all the actors, and norm violations were more likely to be classified as serious than in the case of innocuous themes.

The characteristics of the message also played a role in the evaluation of severity. A combination of violations against more than one norm or several violations against one norm within one comment tended to be rated worse compared with single violations. For instance, political manipulation by troll armies, which violated both the information and the context norm, was evaluated as very severe. Irony and sarcasm were generally evaluated as mild norm violations unless they were also disparaging. Two insults were generally evaluated as more harmful than one insult. Additionally, the target of the norm violation was particularly relevant. When people were targeted, the norm violation tended to be rated as more severe than when objects or institutions were attacked. However, some users and activists found norm violations acceptable when they believed that the target of the violation had “earned” it; that is, they classified a norm violation as acceptable if, for example, Islamists, Nazis, or pedophiles were insulted. Finally, comments that contained constructive elements, not only norm violations, were usually considered less severe.

Furthermore, the presumed consequences of the norm violation were considered. While the community managers primarily evaluated whether the norm violation could potentially foster further norm violations in the discussion, the activists and users evaluated the norm violation according to the number of people it might negatively influence. Activists and users seemed to find it particularly harmful and threatening to democracy if an entire group, rather than a single user, was attacked.

Furthermore, context factors contributed to the evaluation of the severity of norm violations. First, the evaluation depended on the general tone of the discussion and the community on the platform. For instance, norm violations on platforms that had a casual conversational tone and a younger community were rated as less serious. Irony, for instance, was evaluated as a mild violation, and “a bit of beef is fun, after all,” and might even bring the discussion forward (Community manager 8). Furthermore, the quality of the discussion so far was considered, although quite differently among the actors. While users and activists lowered their demands in the case of a high number of norm violations potentially because they had become desensitized, community managers reported that in such cases, they sanctioned significantly more strongly to prevent the discussion from escalating. Further, the medium itself and its genre played roles in evaluating norm violations in discussions. Norm violations in discussions on boulevard medium platforms were less severely evaluated than those on quality medium platforms. Lastly, community managers rated the severity of norm violations based on the national law. If norm violations were illegal, they were classified as very serious and community managers reported that in such cases strict sanctions followed, such as a criminal charge, as well as exclusion from the debate and the platform.

Discussion

The emergence of online discussions on social media and the websites of news media was met with positive expectations regarding their contribution to democracy (e.g., Ruiz et al., 2011). These expectations were quickly replaced by concerns about increasing incivility in comment sections (e.g., Santana, 2014; Rowe, 2015). However, what constitutes incivility is unclear, and only a few studies have addressed what different actors in online discussions perceive as uncivil and evaluate as mildly and severely uncivil. The current study sought to close this research gap. In five heterogeneous focus groups, different online actors discussed what they perceived as uncivil and how they evaluated different types of incivility in terms of their severity. Based on Bormann et al.'s (2021) incivility model, five categories of incivility were identified: informational incivility, formal incivility, processual incivility, personal incivility, and anti-democratic incivility.

The findings of the study thus support a multidimensional model of incivility, or in other words, perceived incivility encompasses violations of several norms, which is in line with previous studies on perceptions of incivility (e.g., Stryker et al., 2016; Kenski et al., 2017; Muddiman, 2017; Ziegele et al., 2020). Previous research, however, has focused on types of incivility that can be classified as violations of the relation norm or the context norm. Few studies have also considered violations of the information norm (Stryker et al., 2016; Frischlich et al., 2019). The analysis of the data collected in the focus groups revealed that additional norms exist, the violations of which were perceived as uncivil in public online discussions, namely violations of the modality and process norm, such as incomprehensible communication or topic deviation. Nonetheless, the results suggest that differences exist among the five communication norms, first in terms of the severity of their violations and second in terms of dissent among the actors (see Figure 1). With regard to Bormann et al.'s incivility concept, it can be concluded that the five norms are not to be considered equal. The results rather suggest that there is a common core of incivility and a somewhat more contested edge. Violations of the relation and context norms were consistently perceived as uncivil and, for the most part, evaluated as quite harmful by all actors, and thus can be classified as the core of incivility. Moreover, violations of the quality dimension of the information norm (i.e., mis- and disinformation) were perceived as uncivil by all actors, and although severity evaluations differed among the actors, these types of violations can also be classified as the core of incivility. Similarly, specific types of violations of the process norm, such as topic deviation and not responding to each other, can be classified as core incivility. Other types of violations of the information and process norms were more controversial, as were violations of the modality norm. These violations can be classified more on the edge of incivility.

In terms of severity, particularly violations of the context norm and the relation norm were evaluated as highly harmful by different actors. Contrary to previous studies that found personal incivility was considered worse than anti-democratic incivility (Stryker et al., 2016; Kalch and Naab, 2017; Kenski et al., 2017; Muddiman, 2017), the latter was evaluated as particularly severe in this study. Users and activists even emphasized, for example, that they found attacks against marginalized groups much worse than insults or threats against themselves. One explanation for these divergent findings could be the operationalization of incivility: In most previous studies, only individual types of norm violations were examined (e.g., insult vs. stereotype), and the study settings varied. Moreover, only a few studies have examined specific perceptions of various participants in online discussions, which may differ from those of bystanders and from perceptions and evaluations of incivility in offline interactions and elite interactions (Stryker et al., 2016; Kenski et al., 2017; Muddiman, 2017). Since existing concepts of incivility and perceptual studies primarily focused on the US context, it might also be concluded that norms, and thus perceptions of norm violations, are “deeply contextual, interwoven with the political and media system” (Otto et al., 2019, p. 2), and thus vary by country and culture. Finally, the numerous severity evaluation criteria identified in this study revealed a multi-layered process of evaluating norm violations. Future studies should therefore conduct a differentiated examination of the construct of incivility and consider the perspectives of communication participants, their numerous evaluation criteria, and their cultural contexts.

Further, the differences and similarities among the actors were analyzed. Although the findings of this study indicate a relatively large common ground among the actors, which is in line with Stryker et al. (2016), some differences regarding what was perceived as uncivil and how distinct types of incivility were evaluated in terms of severity were identified (see Figure 1). These differences could be explained by the distinct roles and associated functions the actors perform in online discussions. Because of their specific roles, individual actors seem to have some diverging expectations toward the discussion behavior of other actors, different norms seem to be chronically salient, and thus norm violations are perceived and evaluated differently in some cases. The users are lay persons in online discussions and enter such discussions to, among others, gain additional knowledge, discuss a specific topic with other users and the medium, and exchange opinions in a reciprocal manner (e.g., Diakopoulos and Naaman, 2011; Springer et al., 2015; Engelke, 2020). This might explain why users evaluated informational and processual incivility as more severely than the other actors. The activists are semi-professional actors in online discussions. They have very high expectations of discussion behavior and discussion quality in general, which is certainly related to their strategic goals: They want to promote a culture of civil and deliberative discussion (e.g., Ley, 2018; Ziegele et al., 2020). Unsurprisingly, activists were often slightly more sensitive to norm violations and evaluated several norm violations more harmful compared to the other actors. The community managers perform a professional role, they represent the medium and its netiquette. This was especially apparent in their evaluations of the severity of norm violations. For example, the community managers often explained that they have to remain politically neutral when evaluating norm violations in political online discussion. Moreover, they often argued from a law perspective to differentiate between more mildly and more severely norm violations and to justify sanctions because the medium has to protect itself legally to avoid lawsuits by users. The users and activists, however, had a much lower tolerance threshold and expected community managers to impose strict sanctions, for example on fake news or topic deviation, even if these violations are not always illegal.

Furthermore, the users and activists showed role-specific expectations toward the communication of community managers that coincide with journalistic quality criteria (Neuberger, 2014; Urban and Schweiger, 2014). They expected community managers to always communicate objectively, clearly, comprehensibly, and transparently, especially about their moderation actions. These role-specific expectations can lead to diverging incivility perceptions as shown in the following example: although users often tolerated irony and sarcasm expressed by other users, they perceived it as uncivil when community managers communicated ironically or sarcastically (see also Ziegele and Jost, 2020).

The differences in the perceptions and evaluations of the participants in the present study could further be explained by factors identified as criteria shaping the evaluation of norm violations (see Table 2). These criteria were classified based on Lasswell's (1948) model of communication: Who (sender) says what (message) in which channel (here broadly defined as context) to whom (recipient) with what effect (presumed consequences)? Hence, incivility is not only a characteristic of the message but the actors also consider the sender, the potential consequences, and the context when they evaluate a message, and individual characteristics also play a role.

Regarding the sender, participants evaluated whether he/she intentionally violated norms, showed intentions to discuss, were a repeated offender, a real or pseudo-user, and whether the sender's political views coincided with their own views and were tolerable. Such social processing of uncivil messages can be explained by attribution theories which deal with peoples' interpretations of the behavior of others (e.g., Heider, 1958; Malle, 1999; Malle and Korman, 2013). Previous research has already indicated that attributions to the sender have an important effect on processing uncivil messages (e.g., Kluck and Krämer, 2021). Regarding the recipient, socio-demographic characteristics, such as age and gender, played a role. Compared with the male participants in this study, the female participants rated norm violations as more harmful, which is in line with the findings of previous studies (e.g., Kenski et al., 2017). However, internal factors, such as situational mood and thematic involvement, were also found to have an impact on evaluations of severity. Moreover, the participants considered message characteristics, the potential consequences of norm violation(s), and different contextual factors, such as platform characteristics, discussion tone, and discussion quality, which have been addressed in some studies (e.g., Coe et al., 2014; Sydnor, 2018) and should be systematically studied in more detail in future research.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings of this study have several theoretical and practical implications. First, the findings demonstrate that incivility should not be viewed as a “monolith” (Masullo, 2022), but as nuanced both in science and (moderation) practice. Future studies should consider violations of information, modality, and process norms in addition to violations of relation and context norms. Moreover, different levels of severity should be considered. Most previous studies measured perceptions of incivility on a single-item scale based on participants' ratings of the degree of incivility of certain communicative behaviors (e.g., Stryker et al., 2016; Muddiman, 2017; Ziegele et al., 2020). Because the insights gained from the present study suggest a wide variance in severity evaluations of distinct types of incivility, future studies should develop scales that provide nuanced measurements of (i) whether a communicative act that contains a norm violation is perceived as uncivil and (ii) how serious, harmful, and sanction worthy, etc. it is evaluated.

Furthermore, future studies should consider different roles and evaluation criteria. Taken together, the findings of the present study suggest that incivility is not a static feature of a message that can be categorized as always equally harmful. Scholars and practitioners cannot assume that all recipients will evaluate an uncivil message in the same way (Kenski et al., 2017). Indeed, the process of evaluating norm violations is multi-layered and seems to depend on the role of a participant in an online discussion and different individual evaluation criteria. This insight further supports to approach incivility from a perceptual perspective, considering that the phenomenon is “multifaceted, individual, and context specific” (Wang and Silva, 2018, p. 73) instead of prescribing what constitutes civility and incivility (for a similar approach see e.g., Chen et al., 2019; Bormann et al., 2021; Kluck and Krämer, 2021). Thus, it is worth pursuing the perceptual approach by examining in detail different online actors and their evaluation processes. Moreover, differences may not be limited to perceptions and evaluations, and they could extend to affective and behavioral reactions to incivility, which should also be addressed in future research.

The results of this study pose major challenges for computational methods that are applied to automatically detect incivility. Overall, the findings indicated that decisions about what is civil and uncivil are highly subjective, depending on the individual's role and other contextual and individual criteria, which can hardly be considered using computational methods. Moreover, previous studies have applied machine learning (e.g., Su et al., 2018) and dictionary-based methods (e.g., Muddiman and Stroud, 2017) to analyze incivility; however, these methods work best in examining explicit forms, such as name-calling (e.g., Davidson et al., 2017). The detection of subtle and context-specific norm violations is challenging and leads to high rates of misclassification (e.g., Stoll et al., 2020). In the present study, the findings from the focus groups showed that, in particular, “impeccable incivility” (Papacharissi, 2004, p. 279) was perceived as highly uncivil. This pertained to norm violations that seemed “polite” at first glance because they did not include name-calling or other explicit forms of incivility, but they attacked individual rights or contained lies, for example. Moreover, the findings revealed many more types of incivility, such as topic deviation and incomprehensible communication, both of which would be equally challenging to detect automatically. Because various media companies use software to detect incivility, the findings of this study are also relevant for the practice of moderation. In the focus groups, community managers reported that their software does not adequately detect norm violations. Until impeccable incivility can be detected, media companies should also monitor comment sections manually. Moreover, researchers and media companies that design and deploy interventions would be well-served to consider role-specific expectations and individual as well as contextual criteria of their users.

The findings of this study have even more implications for media companies. First, the typology of norm violations developed in this study could be beneficial for community management. The typology could be applied in moderation practice as a tool for identifying and evaluating norm violations and for tailoring interventions in different types of incivility. Users not only perceive insults or hate speech as uncivil and sanction worthy, but they also expect community managers to intervene against several other norm violations. Second, users and activists have high expectations of the norm-compliant communication of community managers. Therefore, violations by community managers are perceived quickly, which is relevant for moderation practice.

Limitations