Gender roles and political ideology in the pandemic: experimental evidence from Western Europe

- 1Institute of Political Science, Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Education, and Social Sciences, University of Luxembourg, Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

- 2Department of Behavioural and Cognitive Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Education, and Social Sciences, University of Luxembourg, Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

The economic shutdown and national lockdown following the outbreak of COVID-19 forced families to take on tasks themselves that were previously outsourced, like child care and housecleaning. These tasks were, and to a degree still are, traditionally performed by women. The concern is that the pandemic placed these burdens again primarily on their shoulders. In this study, we examine how the lockdown-imposed difficulties to the outsourcing of essential household tasks affected views on who in the family should sacrifice their career to cope with new challenges, and how these views interacted with ideological commitments. Analyzing data collected from an experiment embedded in a representative survey of nearly 4,000 residents from five West European countries, we find that the pandemic reduced the ideological polarization between the political left and right with regards to gender roles and household tasks. However, this reduced polarization is primarily found among female respondents.

Introduction

Over the last century, and especially after World War II, gender roles in Western economies have been characterized by two major trends. The first is the increasing labor force participation of women. This has coincided with changing perspectives regarding the role of each partner in the household, and a desire to maintain a minimum threshold standard of living (Blossfeld and Kiernan, 1995; Donnelly et al., 2016). Due to an increase in living and housing costs, maintaining such a minimum living standard made the rise in dual-earner households almost inevitable (Leonce, 2020). The introduction of women into the workforce was one of the drivers behind the second trend: rise of the service sector (Rendall, 2018). This sector is what often enabled couples to outsource tasks such as child care and housecleaning – traditional prerogatives of women – and has made it more possible for both partners to pursue their respective careers. While the pre COVID-19 Western societies were a far cry from gender equal utopias, in certain areas including politics and the labor market, progress was made. These efforts were made to strive toward an equilibrium, permitting couples to raise a family without having to sacrifice their jobs. In short, families could “have their cake and eat it” too.

The COVID-19 pandemic has unquestionably upset this delicate balance. In the wake of the virus's spread, many economies, and especially their service sectors, ground to a halt. This had a substantial and negative impact on the employment rate of women (Steiber et al., 2021), leading some to dub the pandemic-induced economic crisis a “Shecession” (Moehring et al., 2021). There are two possible explanations for this gendered effect. One the one hand, women are likely to be employed in the most heavily hit sectors (ibid.). On the other hand it is possible that the inability of families to outsource essential tasks might have placed these burdens again primarily on the shoulders of women (Zamarro and Prados, 2021). The most recent recession's employment penalty in the U.S., for example, primarily hit women with at least one child under twelve (Tavares et al., 2021). Simply put, the heterogeneous economic impact of the economic crisis on men and women can be the result of macroeconomic forces, as well as enduring (or returning) gender roles, roles in which women are largely confined to the domestic sphere and to household and childcare tasks (Alesina et al., 2013).

Our study focuses specifically on these gender roles. We examine how the pandemic and the difficulties it posed to the outsourcing of essential household tasks affected views on who in the family should sacrifice their career to cope with new challenges, and how these views interacted with ideological commitments. Do people prefer for women to once again take up the responsibilities traditionally assigned to them in times of crisis, or have more egalitarian/ progressive views taken root? Are these preferences widely shared, or are they subject to people's overall political world views, with those on the left opposing women sacrificing their careers, while those on the right oppose men giving up theirs? And finally, how do these views differ between men and women? Women are often considered as the empathetic gender (Mestre et al., 2009). But do they actually show more understanding than men when someone becomes a stay-at-home spouse due to the pandemic, regardless of how it fits within their ideological value system?

While we are not the first study to raise these questions (Mize et al., 2021; Reichelt et al., 2021; Rosenfeld and Tomiyama, 2021), and the work so far has suggested that the pandemic has had an impact on gender role perceptions, the use of observational data in other studies inevitably limits the ability to draw causal claims. In this work, we build on and go beyond these studies by tackling the above-mentioned research questions using experimental methods, aiming to uncover a causal link between the pandemic and gender attitudes. Specifically, we analyze data collected from an experiment embedded in a representative survey of nearly 4,000 residents of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. Western Europe was one of the most severely hit regions by the pandemic both in terms of economic consequences and lives lost, making it a highly relevant case in COVID-19 research. Moreover, these countries vary in terms of the participation rate of women in the workforce, allowing us to test the robustness of our findings in a variety of contexts.

The results of our analysis show that the pandemic on the whole reduces the difference between the political left and right in their views on whether the man or the woman should take care of household tasks. We do however, also find evidence that the pandemic-induced reduction in ideological polarization is primarily found among women, who are less likely to judge by their ideological views someone's decision to quit their job if that decision was forced upon them by the pandemic. This provides further evidence that women are indeed the more empathetic gender, and it shows that, somewhat paradoxically, those with arguably the largest stake in the gender-role debate are able to show the greatest willingness to alter their positions in the face of changing circumstances and new information.

Political ideology and gender roles in the household

Attitudes toward the role of family provider have featured for decades in public opinion research. In most Western societies and established democracies, those attitudes have gradually shifted toward more egalitarian views, with people becoming more acceptant of women as the principal breadwinner (Wilkie, 1993; Zuo and Tang, 2000). Even among those identifying with the political right, which was the primary defender of traditional roles of women, stances have evolved toward more liberal attitudes (de Lange and Mügge, 2015). This has resulted in a decline in the so-called radical right gender gap, in which women were less likely to vote for (radical) right political parties (Mayer, 2015). Politicians like Marine Le Pen, for example, have frequently emphasized their support for women's economic independence and women's right to a career (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2015). This is also spurred on by the discourse of those parties against immigration, a topic that has become a dominant issue in public debates in Western democracies. The right and far-right often argue that newcomers from predominantly Muslim countries pose a threat to Western societies, precisely because of their views on gender (in-)equality (Bilge, 2012).

Nevertheless, it would be too soon to argue that the relation between ideology and gender roles no longer exists. Some have argued that the gender equality rhetoric espoused by rightwing commentators should primarily be viewed as strategic, i.e., as something instrumental in supporting their anti-Islam views aimed to cement their position as “defenders of Western civilization,” rather than a change of heart on gender relations (Don, 2021). There seems to be a contradiction within rightwing conservatism, in that it opposes Muslim immigration because of the supposed threat to women's rights, but at the same time aspires to a return toward a “natural” patriarchal order (Norocel, 2011; Akkerman, 2015; Celis and Childs, 2018). Social conservatism at its core views men and women as complementary rather than as equals. In this complementary relation, women are predominately associated with the communion stereotype, which focuses on others and their wellbeing. Among men, by contrast, the agency stereotype prevails, emphasizing independence, self-confidence, dominance, and self-assertion (Riggs, 1997; Eagly et al., 2020). People who hold socially conservative views can be expected to prefer role patterns for men and women that reflect these stereotypes.

In sum, in spite of a general increase in egalitarian gender views, we predict there to be a relation in public opinion between ideology and attitudes toward the family provider role and family responsibilities. Specifically, we believe that the more socially conservative people are, the more they will favor the female partner staying home and taking care of family responsibilities, and the male partner providing the family income. This is our first, baseline, hypothesis.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been without a doubt one of the most disruptive events in modern history. Cities that were bustling with life were suddenly marked by eerie silence. News headlines became dominated by updates over new infections, hospitalizations, and COVID-related deaths. Especially the early stages of the pandemic were marked by uncertainty over how infectious the virus was, how it could be transmitted, and how lethal it could be. The pandemic caused uncertainty and even a sense of existential threat. Previous studies have suggested that such feelings are not without political ramifications.

Specifically, it can be argued that events that create uncertainty and a sense of existential threat make people more socially conservative (Drouhot et al., 2021; Rosenfeld and Tomiyama, 2021). Pathogen prevalence has been found to positively correlate with a heightened sense of collectivism (Fincher et al., 2008; Reeskens et al., 2021) While collectivism is a key component in leftwing economic ideology (see for instance Margalit, 2013), it is also unmistakably associated with a greater emphasis on conformity and tradition, as it views individuals subordinate to a social collectivity. In other words, the increased social conservatism, resulting from the heightened collective sense of social solidarity, encourages adherence to social conventions and norms as a means to promote in-group cohesion (Altemeyer, 1988). Indeed, especially the early stages of the pandemic saw an increased intolerance to rule breaking (Doyle and McElroy, 2020). According to the behavioral immune system theory (Schaller, 2006; Terrizzi et al., 2013), humans have evolved in such a way that they have developed instinctive affective and behavioral responses to diseases, as a means to avoid them and reduce their spread. This primarily affects feelings toward outgroup individuals, stimulating in that way conservative attitudes and aversion against anyone who looks and acts differently (Schaller and Park, 2011). In some ways, this makes sense because new pathogens are usually introduced by outgroup members. However, evidence is emerging that this conservative or conformist reflex spills over into other attitudes and behaviors that by themselves do not have any disease-buffering properties (Helzer and Pizarro, 2011; Murray and Schaller, 2012).

The adherence to established, traditional social roles may also be a coping mechanism to counter the feeling of threat and the uncertainty that events like the COVID-19 pandemic introduce (Jost et al., 2003; Wilson, 2014). The blurring of lines and established role patterns between men and women creates ambiguity that can be viewed as undesirable in times of general turmoil (Budner, 1962). This too then should result in the favoring of compliance with classic gender roles (Makwana et al., 2018). These gender roles, while certainly having evolved over the past decades, are anything but gone from contemporary society. For instance, a recent American study found that men devote substantially more time to leisure activities in their non-work time and less to household tasks than women do (Kamp Dush et al., 2018). Traditional gender role patterns are still the default, and it is possible that the tolerance threshold for gender role ambiguity can be lowered by disruptive events such as a pandemic.

To summarize, the threat of a pathogen, e.g., virus, can be expected to result in disease-preventing attitudes and behavior that spill over into a generally more conservative outlook. In addition, social conservatism offers the stability that is in such short supply in uncertain times. As a result, we expect that preferences toward who should take care of household responsibilities and who should be the breadwinner become more conservative when that decision is placed within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is our second hypothesis.

In addition to a general conservative turn due to the pandemic, we expect that the pandemic will alter the relation between ideology and gender role preferences (Gadarian et al., 2021). Specifically, when asked to judge the decision of one of the parents in a family to quit their job and become a stay-at-home spouse without being externally pressured to do so, those evaluations are predicted to be very much in line with ideological views. That is to say, social conservatives will prefer the female partner to stay at home and the male partner to provide the income, while the opposite will be true among progressives.

If, however, that decision was pressured by external events, beyond anyone's control, then the ideological underpinnings of the people's evaluations are expected to be weaker. This is because the pandemic severely reduces people's agency, rendering the choices they make more a function of other factors than their own free will. In that sense, the pandemic serves as an additional consideration that people take into account, besides their ideological worldviews, when developing attitudes toward household tasks and the breadwinner role. In other words, compared to a non-pandemic context, the disagreements between those on the left and right on the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities are expected to be smaller, or less ideologically polarized, when viewed in context of the health crisis.

Our argumentation here can in some ways be compared to the argumentation in the literature on the clarity of responsibility and economic voting (e.g., Tavits, 2007; Hobolt et al., 2013; Karyotis and Rüdig, 2015). A large body of literature has found that the severity of people's evaluations of incumbents and governments are conditional on the ability to clearly attribute blame and guilt to them. If that is not the case, elected officials regularly avoid negative evaluations at the polls despite poor economic performance or even corruption.

We expect something similar to happen in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. People's ideology-induced attitudes toward the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities are expected to be moderated if that division is induced by the pandemic rather than people's independent decisions. We argue that the pandemic as the instigating factor obfuscates whether the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities is a reflection of gender role views of those involved, or a function of circumstance. The possibility that it could be the latter invokes empathy and a sense that the division needs to be viewed on its own terms (Malhotra and Kuo, 2008; Korsunova and Sokolov, 2023). As a result, people are expected to become less certain of the appropriateness of using their own ideological views as a frame of reference with which to evaluate the role distribution within a family. Indeed, simulation studies have suggested that external shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic can reduce ideological polarization, the severity of the situation making people more accepting of solutions they would normally oppose on ideological grounds (Axelrod et al., 2021). Attitudes toward the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities are thus expected to be more moderated, regardless of whether it is in line with one's ideological views. This is our third hypothesis.

The logical corollary of hypothesis three is that the extent to which COVID-19 as context moderates the relation between ideology and the attitudes toward the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities depends on one's ability to show understanding of the situation of others; in other words, to be able to perceive the internal frame of reference of another (Zahn-Waxler and Radke-Yarrow, 1990; Gold and Rogers, 1995). It is this empathetic ability that makes one look more favorably upon a situation because it was pandemic-induced, despite it being something that they are, by virtue of their ideological views, fiercely opposed to or in favor of. Though empathy can aggravate polarization when conditional on in-group membership (Simas et al., 2020), it has been seen as a crucial component in reducing intergroup conflict and prejudice (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008). We therefore maintain that the degree to which the pandemic, as an instigator of the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities, results in ideological moderation can thus be expected to be dependent on one's capacity for empathy.

Previous research has suggested that women might display a greater degree of empathy than men (Batson et al., 1996; Kobach and Weaver, 2012). We do not aim to settle the nature or nurture origins of this difference, nor do we believe it can ever be settled. This difference is arguably inextricably rooted in biology and culture, in which certain physiological pressures stemming from humans being an altricial species reinforce and are in turn reinforced by distinct socialization experiences in which girls and women internalize caring and prosocial traits (Preston and De Waal, 2002; Van der Graaff et al., 2018). For the purposes of this study, it is of lesser importance to know exactly how women came to display a greater aptitude for empathy. More important is that they do. In this regard, the empathic difference between men and women has already been found to explain gender differences regarding interventionist policies. In the U.S., gender differences with regards to government involvement in combating poverty, inequality, and improving social welfare all disappear when empathy is accounted for (Toussaint and Webb, 2005; Cavalcanti and Tavares, 2011; Kamas and Preston, 2019).

This is not to say that the relation between gender and empathy is uncontested. There are many issues including methodological ones still to be worked out before the debate can be settled (Derntl et al., 2010; Baez et al., 2017). However, we believe the current evidence favors expecting women to display more empathy than man. When we then apply these insights to the subject of this inquiry, women can be expected to be more willing to discard their ideological views when developing attitudes toward a division of household and breadwinner responsibilities. By contrast, men, being less empathetic toward the circumstances and external pressures that led to a certain decision, are anticipated to show fewer reservations to keep evaluating a distribution of tasks within a family on the basis of their world views. In short, the pandemic-induced ideological moderation predicted in the third hypothesis is expected to be stronger among women than it is among men. This is our fourth and final hypothesis.

Data and method

To test our expectations, we rely on data collected in a panel survey conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. In all five countries, the difference between female and male inactive populations of working age is positive, i.e., the level of female economic inactivity is greater. This difference, however, varies and ranges from about 4% in Sweden to close to 20% in Italy. While this difference has been decreasing over time, the pandemic saw the labor market participation gap initially increase (indicating a stronger negative impact on the labor market participation of women), before correcting in the subsequent months. This makes the sample of countries studied here good cases to examine how gender roles and moments of crisis affect the employment opportunity structure of women.

Respondents in the panel survey were contacted by Qualtrics, which runs specialized recruitment campaigns via its partner network. This allows them to reach even those groups that have been traditionally hard to survey via the internet. In addition, Qualtrics performs several data quality controls that account for rushing through the survey and multiple participations by the same person (through IP address checks and digital-fingerprinting technology). The survey featured eight waves with more planned in the future. The first five waves were conducted from 27 April 2020 to 1 March 2021. The sixth wave, which includes the survey experiment that is the focus of this article, took place in June 2021. The initial group of respondents (wave 1) were selected through stratified sampling, and were nationally-representative in terms of age, gender, and region of residence. Over 8,000 people took part in the first wave of the survey, and of that, a usable sample 4,190 participated in the sixth wave. This excludes 27 people who took part in the sixth wave, but who did not answer all necessary questions. Inevitably, however, the drop-out in each subsequent wave has resulted in differences between the sample used here and the population. Specifically, younger respondents were more likely to drop out. In addition, there is a general overrepresentation of the higher educated in the sample.

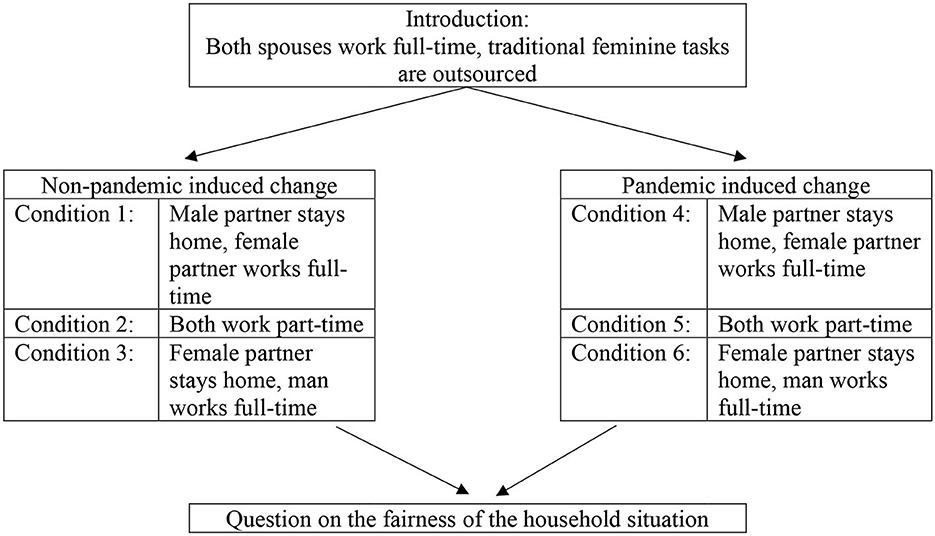

To study attitudes toward gender roles in the household, we ran a survey experiment. In this experiment, each respondent was presented with a scenario describing a household situation. In the base version of the scenario, both male and female partner initially worked full-time and pursued their own careers. This was made possible by the outsourcing of childcare through school and daycare and the reliance on a house cleaner to take on tasks otherwise disproportionately performed by women under traditionally gendered household arrangements. However, in our scenario this situation changes, and instead of outsourcing childcare and household tasks, the couple have to take on these tasks themselves. The experiment had a 3 × 2 factorial design. The first factor deals with the three ways in which the couple could take on these tasks themselves: one where both spouses take on a portion of household responsibilities and start working part-time, and two more where either the female or the male partner becomes a stay-at-home spouse. The second factor revolves around what drove the couple to take on the tasks themselves rather than outsource them. In one version of the experiment, no reason was given why the couple decided to take on the household responsibilities themselves, and in another, it was explained that this decision was induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The outcome variable is the perceived fairness of the new household situation, i.e., how fair respondents believe the new distribution of household tasks and its impact on the employment situation of both spouses to be. This perceived fairness is measured on an 11-point scale, which ranges from very unfair (0) to very fair (Mestre et al., 2009). The two factors are referred to as Change in employment situation, and Pandemic induced change, respectively, in the analyses. The experimental design is summarized in Figure 1, and the description of the various scenario elements is given in Table A1.

A possible caveat of this experimental design is the fact that it took place during the pandemic. If a crisis like the pandemic indeed shapes gender attitudes, the responses given in this experiment might be more conservative, and the effect of the experimental treatment reduced. However, it is unlikely that this experiment would have worked outside the pandemic context, as it arguably made the predicament in which many households found themselves very tangible. Furthermore, other experimental designs also rely on priming the pandemic for respondents in order to gauge its causal effect (Karwowski et al., 2020).

Respondents were assigned at random to one of the six conditions. This makes it possible to assess the vignette factors' causal effect on the outcome variable (Atzmüller and Steiner, 2010). In other words, while there is some bias in the composition of the sample, the effect estimates presented below are free of any bias. The third main independent variable in our analysis is Social conservatism. This is captured by averaging people's responses to five policy statements on issues such as immigration, LGTBQ+ rights, and obedience to authority, separating progressives from conservatives (see Table A2). The fourth and final main explanatory variable is the respondent's Gender.

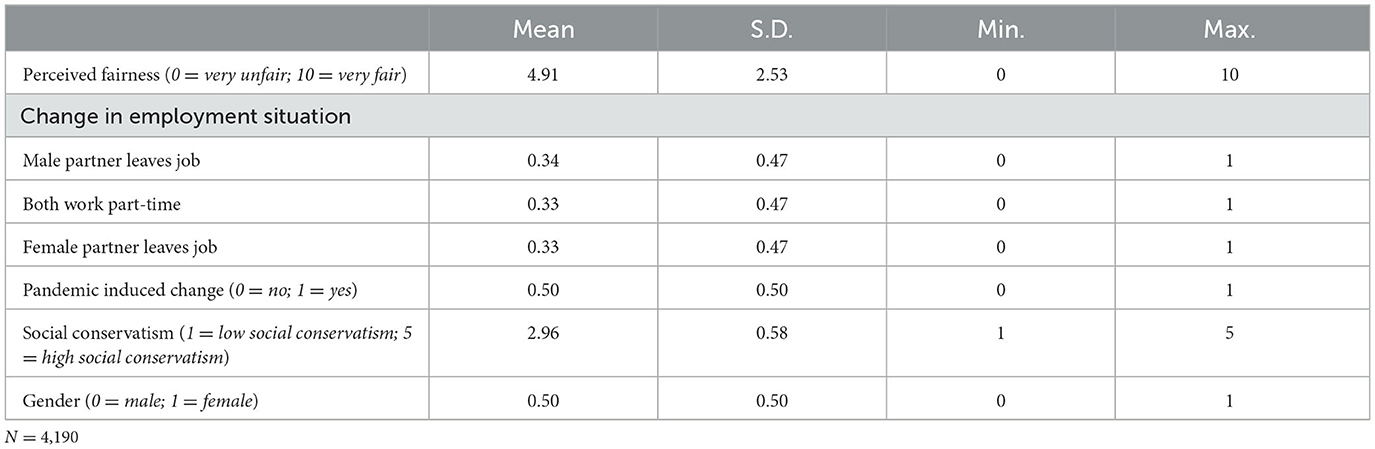

In our analyses, we control for age, level of education, disposable household income, current employment status, whether the respondent or their spouse has been unemployed at any point during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their country of residence. Regarding education, we distinguish among three groups: lower educated voters only have an elementary school degree, middle educated voters are those who have finished their secondary education, and higher educated voters are those who have a graduate or university degree. Income was measured using the following seven categories (in Euros): “0 to 1250,” “1250 to 2000,” “2000 to 4000,” “4000 to 6000,” “6000 to 8000,” “8000 to 12,500” and “Over 12,500.” In our analyses, we pool the data from the three countries and account for country-level differences by including country dummies. In addition, we verified that the results presented below are not driven by one single country by performing jackknife bootstrap procedure. Results of all robustness tests can be provided upon request. Table 1 gives an overview of all principal variables. Table A3 gives an overview of all covariates.

Results

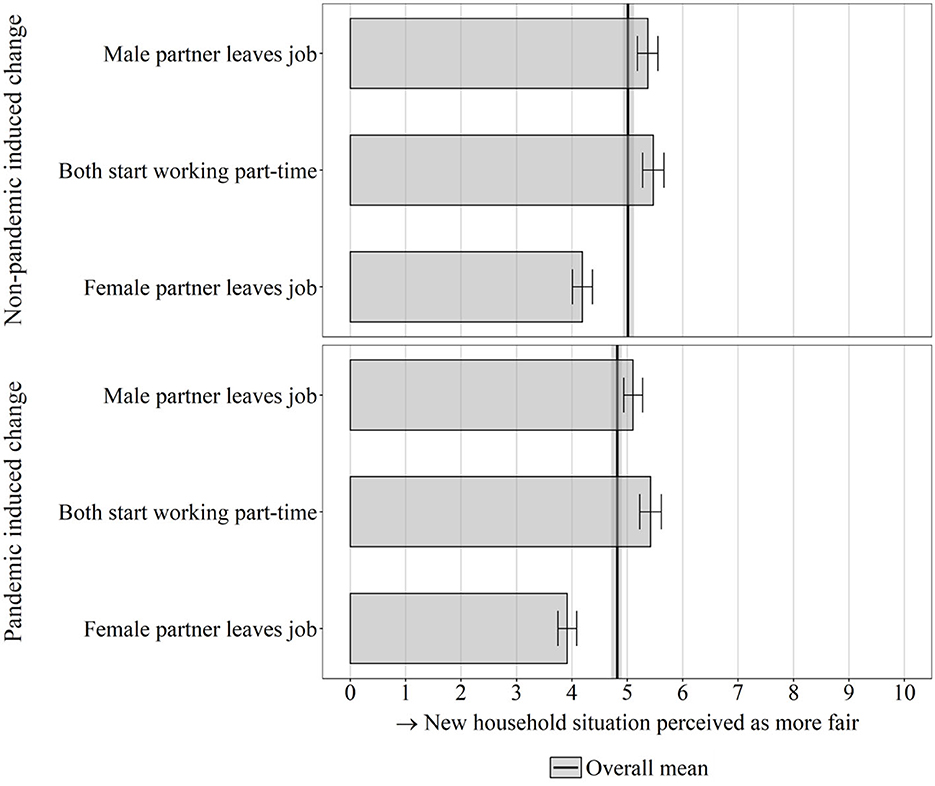

Before testing the effects of various explanatory variables in a multivariate model, we examine the average perceived fairness for each of the six conditions. In the baseline, non-pandemic induced versions of the conditions (top panel in Figure 2), both the scenarios in which the male partner becomes a stay-at-home spouse and in which both spouses start working part-time are clearly considered fairer than the scenario where the female partner quits her job. When the change in the household situation is pandemic-induced (bottom panel in Figure 2), we see that the conditions where one of the spouses leaves their job are viewed as slightly less fair. At face value, this finding contradicts most other accounts of people's views on the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities. We believe it to be likely driven by the overrepresentation of higher educated respondents in the sample. What is also notable is that the overall perceived fairness scores are slightly lower when the change is pandemic-induced, presumably due to the lack of agency this scenario implies.

Figure 2. The experimental conditions and the perceived fairness of the new household situation. The error bars/gray area represents the 95% confidence interval.

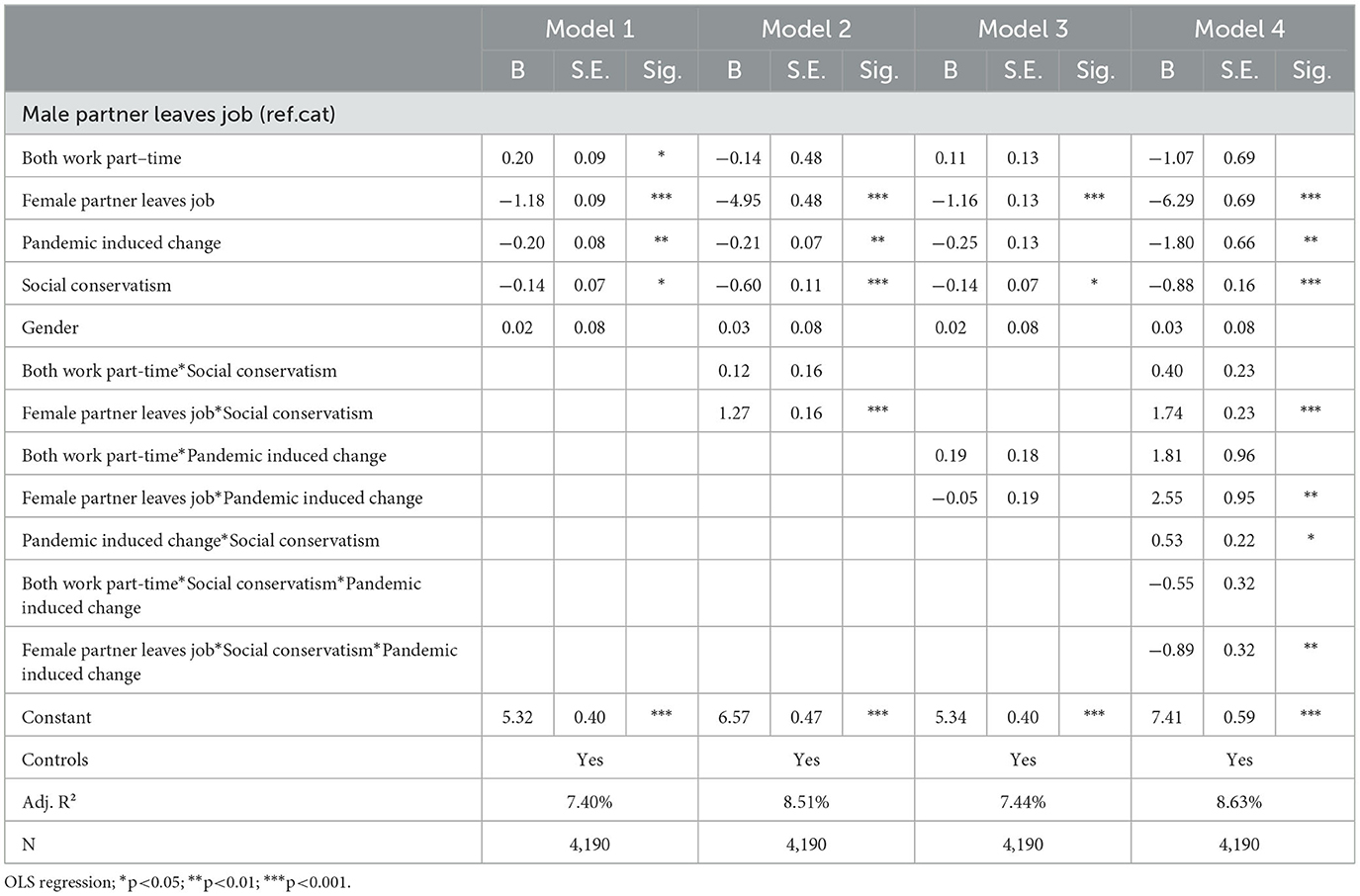

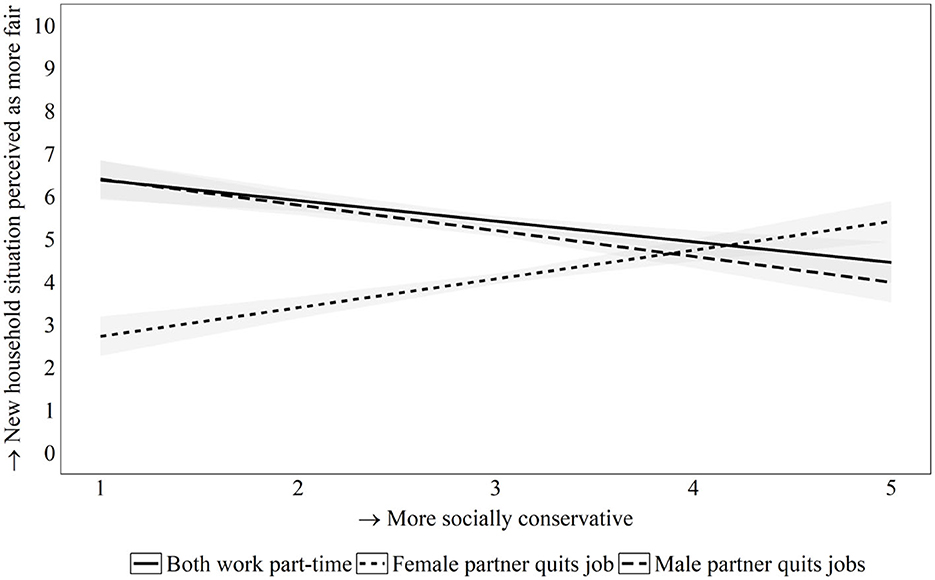

The coefficients of the multivariate analyses are reported in Table 2. Model 1 shows the direct effects of all variables. It confirms the differences between the six conditions of Figure 2: the female partner leaving her job is deemed least just, and if the change in household situation is made in the context of the pandemic, then all changes seem to be perceived as less fair, regardless of the outcome. Model 2 tests whether the attitudes toward the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities are related to ideological views, specifically social conservatism. The first hypothesis predicted that socially conservative people will prefer women to take on a more traditional role. The highly significant and positive coefficient for the interaction term Femalepartnerleavesjob*Social conservatism in Model 2 indicates that the more conservative a person is, the more they deem it fairer when the female partner quits her employment and becomes a full-time stay-at-home spouse. The interaction is plotted in Figure 3. There is a clear negative relation with social conservatism when the male partner quits his job, but this relation turns highly positive (as indicated by the positive interaction term) when it is the female partner that quits hers. Social progressives are fiercely opposed to the female partner quitting her job, but consider it more just when the male partner does. Presumably, this is because this creates more gender equality on a societal level. We see a similar relation for the scenario where both spouses start working part-time. The gap between the solid and the dotted line narrow as we go up the social conservatism scale. While there is a preference for the scenario where the female partner quits her job over the one where the male partner quits his, the gap between the two is far smaller than the reverse gap is among progressives. One could view this as a sign that, at least on the level of the public, conservatives have begun to reconsider their stance on gender equality and become more ambivalent about it. Regardless, the data provides strong support for our first hypothesis.

Figure 3. Social conservatism and the perceived fairness of the new household situation. Predicted probabilities are based on the results of Model 2, Table 2; all other variables are kept at their mean value; the gray area represents the 95% confidence interval.

The second hypothesis suggests that the pandemic would stimulate a more socially conservative view on gender roles in the division of household responsibilities. This assertion is tested in Model 3 in Table 2. However, both terms covering the interaction between Change in employment situation and Pandemic induced change are not significant at the p < 0.05 level. We hypothesized that the threat of a pathogen would result in disease-preventing attitudes and behavior that spill over into a generally more conservative outlook. We also suggested that social conservatism may offer stability in uncertain times. However, this line of argumentation – detailed in our second hypothesis – finds no support in the data. As mentioned before, it is possible that this is due to the pandemic context, which might have rendered the analyses in Model 3 a conservative test of the hypothesis. However, considering the small size of the coefficients, we believe that this is unlikely the reason behind the lack of support.

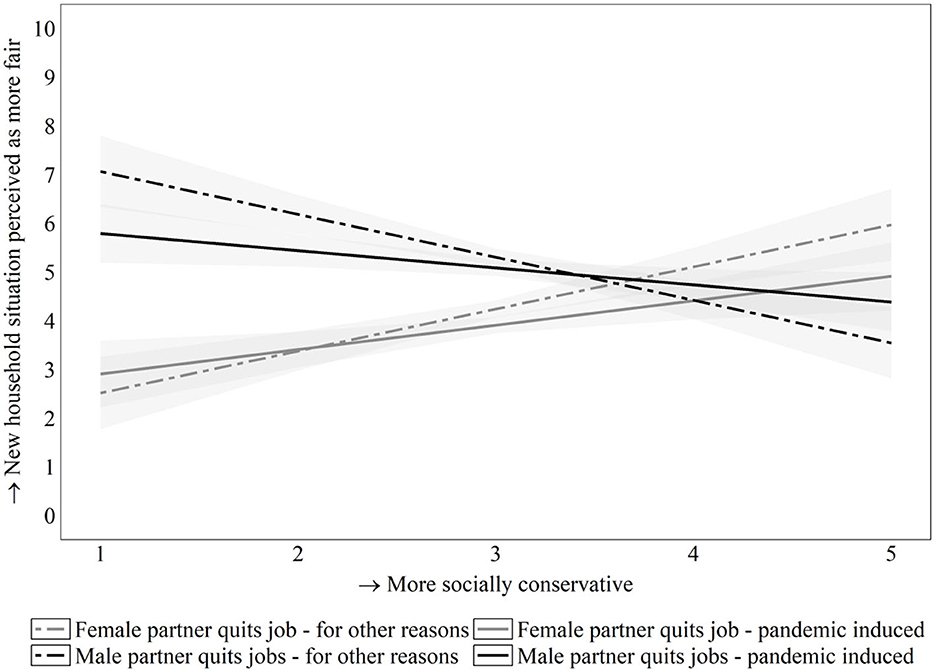

Our third hypothesis argued that the pandemic may have a moderating effect on the role of ideology, as it encourages respondents to relinquish using their own ideological views to evaluate the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities. We proposed this may be true because the pandemic as the instigating factor would obfuscate whether the division of household and breadwinner responsibilities was a reflection of gender role views of those involved, or a function of circumstance. This means that, if true, the effect of the interactions tested in Model 2 between Social conservatism and Change in employment situation would be dependent on whether the change was pandemic induced or not. We tested this in Model 4 in Table 2 by adding two second-order interactions. The negative interaction term for Female partner leaves job*Social conservatism*Pandemic induced change indicates that the positive interaction effect reported in Model 2 and Figure 3 becomes a lot smaller when the change in the household situation is forced upon the couple by the pandemic. The result is plotted in Figure 4, which shows that the relations between social conservatism and the female or male partner quitting their jobs in the context of COVID-19 (solid lines) are significantly flatter than when these decisions were made prior to the pandemic (dashed lines). The confidence intervals in the graphs overlap but it is a common misconception to interpret this as meaning that the effect is not significant. The problem is that such an interpretation looks at the wrong interval. The figures show the confidence interval of each coefficient, while the test of significance relies on the mean difference between the coefficients. While non-overlapping confidence intervals always imply a statistically significant difference, the reverse is not necessarily true (Austin and Hux, 2002). These findings thus support the third hypothesis.

Figure 4. Social conservatism, the pandemic and the perceived fairness of the new household situation. Predicted probabilities are based on the results of Model 4, Table 2; all other variables are kept at their mean value; the gray area represents the 95% confidence interval.

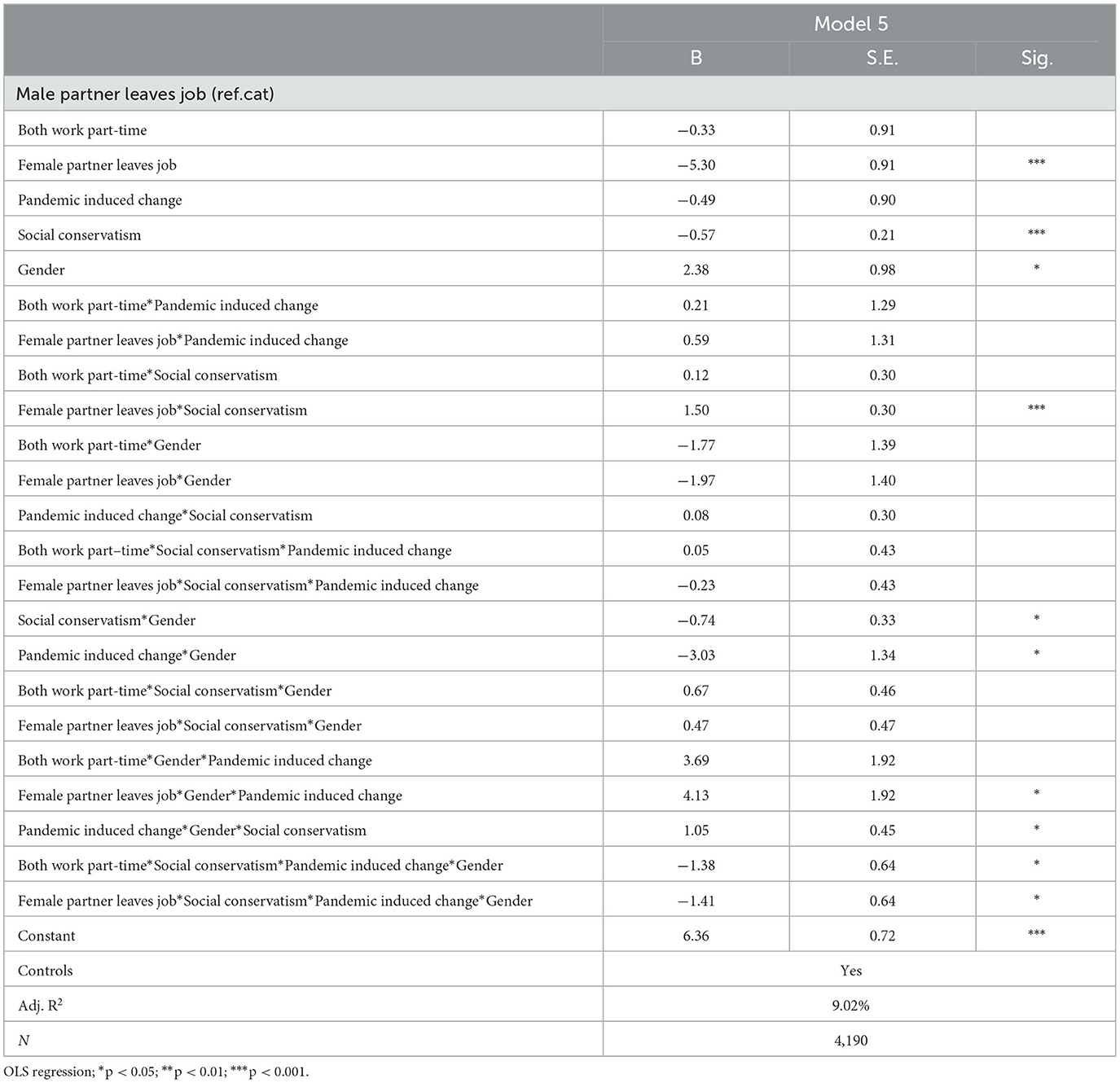

The fourth and final hypothesis stipulated that the ideological moderation engendered by the pandemic was in turn dependent on gender, with women having a greater capacity for empathy than men (Kirkland et al., 2013; Kamas and Preston, 2021). Unfortunately, the data lacks a direct measurement of empathy. This then needed to be tested by examining whether the relation predicted in the second-order interaction of the third hypothesis was more applicable for women than it was for men. If women are more empathetic, then primarily or only for female respondents should we see that the relation between Social conservatism and Change in employment situation diminished when the change was pandemic induced. To that end, we ran a model with a third-order interaction, presented here in Table 3. We acknowledge that a third-order interaction entails a complicated model, the coefficients of which are difficult to interpret by themselves. Given the design of the experiment, such complicated models are almost inevitable. This is because the direct effects of most independent variables are almost all non-sensical, as they indicate the relation with the dependent variable across all conditions. In order to make sense of factors such as ideology and gender, interactions are simply inescapable.

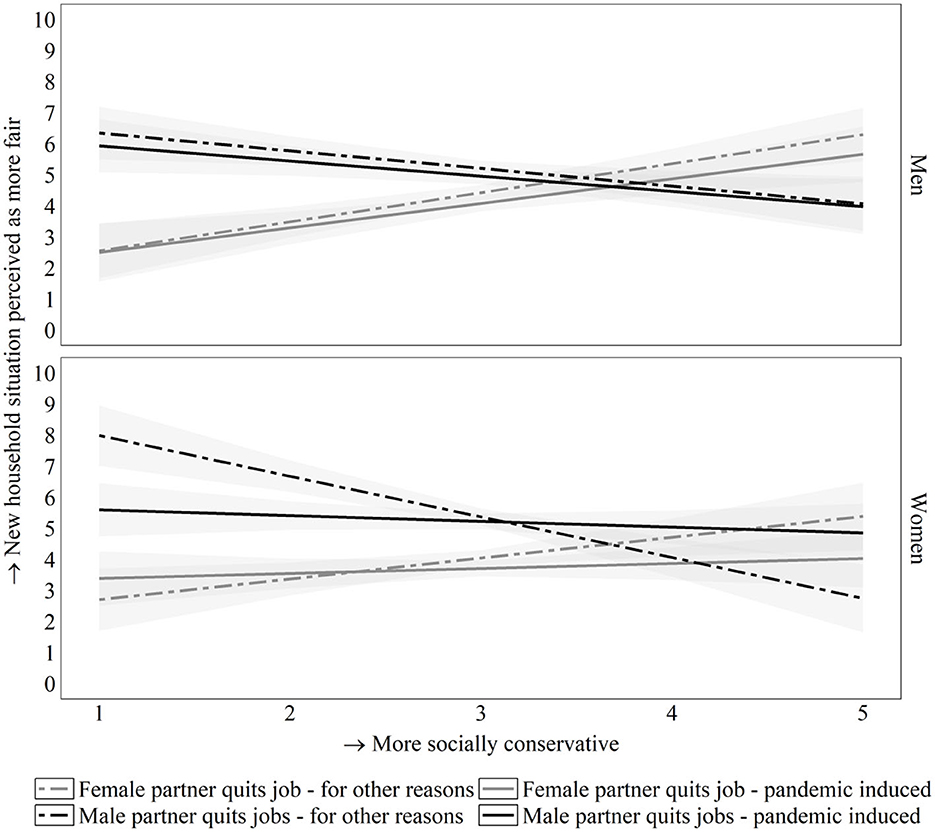

As the results of our analysis show, one of the two third-order interaction terms is significant. To make more sense of this model, we plot the predicted probabilities in Figure 5. In the top graph, the dashed and solid lines hardly differ, meaning that men do not alter their ideology-driven views of the new household situation, regardless of whether the change was done in the context of the pandemic or not. In the bottom graph, things are different, primarily for the scenarios in which the male partner quits his job. Starting on the left side of the x-axis, progressive women just like and even more so than progressive men, believe it to be very fair when the male partner becomes a stay-at-home spouse when this decision was made in normal circumstances (black dashed line). However, when the decision that he leave his work was made during the pandemic (black solid line), the line is almost flat, indicating a sharply reduced difference in attitudes between progressives and conservatives. Arguably, the lack of agency in the pandemic condition generated a sense of empathy for the male partner among progressive women. For conservative women in turn, becoming a stay-at-home spouse as a man was fairer in the context of the pandemic. While keeping the data limitations in mind, we nevertheless believe the most prudent interpretation to be that this indicates a reduced disapproval and increased understanding of it not being the female partner that quits her job in favor of her male partner's career. If nothing else, we are convinced that this is the most plausible interpretation. In short, we believe the data are highly suggestive of women being the empathetic gender, and supportive of our fourth hypothesis.

Figure 5. Social conservatism and the perceived fairness of the new household situation. Predicted probabilities are based on the results of Model 5, Table 3; all other variables are kept at their mean value; the gray area represents the 95% confidence interval.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only exposed health, economic, social, and political vulnerabilities of contemporary societies. It has also arguably changed how we perceive and interact with a number of previously held social roles and beliefs. In the initial stages of the pandemic, our economies went through a rapid adjustment that seemed to restructure whole economic sectors, as well as family balances, and gender roles. Women were disproportionately forced to adapt to the changed situation by retreating to the family sphere to perform duties traditionally assigned to them. With this study, we wanted to shed light on the question of whether this gendered effect of the pandemic was caused by a different appreciation of in gender roles as opposed to the already noted impact of macroeconomic forces on the service sector. We wanted to know whether the pandemic and the challenges it presented for contemporary families affected people's views on gender roles in the provision of household and parenting tasks and how those views were related to people's ideological commitments.

The main thrust of our findings is that the pandemic seems to have had an effect on the difference between the political left and right in their views of gender roles in the family. As our analysis shows, that difference between the two ends of the political spectrum is reduced when gender roles in the family are affected by the pandemic. That said, however, our findings do point to the likelihood that it is primarily among women that this pandemic induced decreased ideological polarization is found. The results of our analysis suggest that women are less likely to judge by their ideological views someone's decision to quit their job if that decision was forced upon them by the pandemic. We believe this finding is further evidence that women are indeed the empathetic gender. It is also evidence that, perhaps paradoxically, those arguably most directly affected by the debate on gender roles in the family and the economy are able to show the greatest acceptance of change in their position in the face of shifting circumstances and new information.

Obviously, our study is not without limitations. There are, first of all, limitations inherent to all experimental research. It is entirely possible that our design does not capture the true nature of people's possible shift in views of gender roles. Our survey respondents could very well have been engaged in virtue signaling that could be masking their true beliefs. Moreover, our study was focused on Western Europe – region where progressive views of gender roles have arguably become far more firmly embedded than is the case elsewhere in the world. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic may not have disrupted women's progress in the division of labor in the workplace and the family in Western Europe, but that may not be the case in societies where these progressive gender roles have not taken firm root. Finally, while we do believe that differences in empathy are what is driving the differences between men and women, future research should endeavor to confirm this assertion more robustly. Regardless of this, however, we believe our analysis offers important insights into the interaction among gender, family, economy, and political ideology in contemporary societies recovering from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. It particularly highlights the difference in the response of men and women to the gendered challenges the pandemic has posed to the organization of their family lives.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Luxembourg Ethics Review Panel. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. CD'A: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. CV: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. André Losch Fondation, Art2Cure, Cargolux, CINVEN Fondation, and the COVID-19 Foundation, under the aegis of the Fondation de Luxembourg, and the Fonds National de la Recherche Luxembourg (Grant 14840950 - COME-HERE) are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1325138/full#supplementary-material

References

Akkerman, T. (2015). Gender and the radical right in Western Europe: a comparative analysis of policy agendas. Pattern. Prej. 49, 37–60. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023655

Alesina, A., Giuliano, P., and Nunn, N. (2013). On the origins of gender roles: women and the plough*. The Q. J. Econ. 128, 469–530. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjt005

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of Freedom: Understanding Right-Wing Authoritarianism, 1st Edn. San Francisco, NJ: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 378.

Atzmüller, C., and Steiner, P. M. (2010). Experimental vignette studies in survey research. Methodology 6, 128–138. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000014

Austin, P. C., and Hux, J. E. (2002). A brief note on overlapping confidence intervals. J. Vasc. Surg. 36, 194–195. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.125015

Axelrod, R., Daymude, J. J., and Forrest, S. (2021). Preventing extreme polarization of political attitudes. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 118, e2102139118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2102139118

Baez, S., Flichtentrei, D., Prats, M., Mastandueno, R., García, A. M., Cetkovich, M., et al. (2017). Men, women…who cares? A population-based study on sex differences and gender roles in empathy and moral cognition. PLoS ONE 12, e0179336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179336

Batson, C. D., Sympson, S. C., Hindman, J. L., Decruz, P., Todd, R. M., Weeks, J. L., et al. (1996). “I've been there, too”: effect on empathy of prior experience with a need. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 22, 474–482. doi: 10.1177/0146167296225005

Bilge, S. (2012). Mapping Québécois sexual nationalism in times of ‘crisis of reasonable accommodations.' J. Interc. Studies. 33, 303–318. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2012.673473

Blossfeld, H. P., and Kiernan, K. (1995). The New Role of Women Family Formation in Modern Societies. Routledge.

Budner, S. (1962). Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. J. Pers. 30, 29–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1962.tb02303.x

Cavalcanti, T. V. D. V., and Tavares, J. (2011). Women prefer larger governments: growth, structural transformation, and government size. Econ. Inq. 49, 155–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2010.00315.x

Celis, K., and Childs, S. (2018). Introduction to special issue on gender and conservatism. Politics Gender 14, 1–4. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X17000654

de Lange, S. L., and Mügge, L. M. (2015). Gender and right-wing populism in the low countries: ideological variations across parties and time. Patterns Prejudice 49, 61–80. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014199

Derntl, B., Finkelmeyer, A., Eickhoff, S., Kellermann, T., Falkenberg, D. I., Schneider, F., et al. (2010). Multidimensional assessment of empathic abilities: neural correlates and gender differences. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.006

Don,à, A. (2021). Radical right populism and the backlash against gender equality: the case of the Lega (Nord). Contemp. Italian Politics. 13, 296–313. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2021.1947629

Donnelly, K., Twenge, J. M., Clark, M. A., Shaikh, S. K., Beiler-May, A., Carter, N. T., et al. (2016). Attitudes toward women's work and family roles in the United States, 1976–2013. Psychol. Women Q.. 40, 41–54. doi: 10.1177/0361684315590774

Doyle, M., and McElroy, N. (2020). Why People Get Angry at Coronavirus Rule-Breakers and Want to Call the Police. ABC News. (2023) Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-14/why-people-are-angered-by-covid-breakers-want-to-phone-police/12656920 (accessed October 11, 2023).

Drouhot, L. G., Petermann, S., Schönwälder, K., and Vertovec, S. (2021). Has the COVID-19 pandemic undermined public support for a diverse society? Evidence from a natural experiment in Germany. Ethnic Rac. Stu. 44, 877–892. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1832698

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., and Sczesny, S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of u.s. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am. Psychol. 75, 301–15. doi: 10.1037/amp0000494

Fincher, C. L., Thornhill, R., Murray, D. R., and Schaller, M. (2008). Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proc. Royal Soc. Biol. Sci. 275, 1279–1285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0094

Gadarian, S. K., Goodman, S. W., and Pepinsky, T. B. (2021). Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 16, e0249596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249596

Gold, J. M., and Rogers, J. D. (1995). Intimacy and isolation: a validation study of Erikson's theory. J. Hum. Psychol. 35, 78–86. doi: 10.1177/00221678950351008

Helzer, E. G., and Pizarro, D. A. (2011). Dirty liberals! Reminders of physical cleanliness influence moral and political attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 22, 517–522. doi: 10.1177/0956797611402514

Hobolt, S., Tilley, J., and Banducci, S. (2013). Clarity of responsibility: How government cohesion conditions performance voting: how government cohesion conditions performance voting. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 52, 164–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02072.x

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., and Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bullet. 129, 339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

Kamas, L., and Preston, A. (2019). Can empathy explain gender differences in economic policy views in the United States? Femin. Econ. 25, 58–89. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2018.1493215

Kamas, L., and Preston, A. (2021). Empathy, gender, and prosocial behavior. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 92, 101654. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2020.101654

Kamp Dush, C. M., Yavorsky, J. E., and Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2018). What are men doing while women perform extra unpaid labor? Leisure and specialization at the transitions to parenthood. Sex Roles 78, 715–730. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0841-0

Karwowski, M., Kowal, M., Groyecka, A., Białek, M., Lebuda, I., Sorokowska, A., et al. (2020). When in Danger, turn right: Does COVID-19 threat promote social conservatism and right-wing presidential candidates? H. 35, 37–48. doi: 10.22330/he/35/037-048

Karyotis, G., and Rüdig, W. (2015). Blame and punishment? The electoral politics of extreme austerity in Greece. Polit Stu. 63, 2–24. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12076

Kirkland, R. A., Peterson, E., Baker, C. A., Miller, S., and Pulos, S. (2013). Meta-analysis reveals adult female superiority in “reading the mind in the eyes” test. North Am. J. Psychol. 15, 121–146.

Kobach, M. J., and Weaver, A. J. (2012). Gender and empathy differences in negative reactions to fictionalized and real violent images. Commun. Rep. 25, 51–61. doi: 10.1080/08934215.2012.721087

Korsunova, V., and Sokolov, B. (2023). Support for emancipative values in Russia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociol. J. 29, 8–24. doi: 10.19181/socjour.2023.29.2.1

Leonce, T. E. (2020). The inevitable rise in dual-income households and the intertemporal effects on labor markets. Comp. Benef. Rev. 52, 64–76. doi: 10.1177/0886368719900032

Makwana, A. P., Dhont, K., De keersmaecker, J., Akhlaghi-Ghaffarokh, P., Masure, M., and Roets, A. (2018). The motivated cognitive basis of transphobia: the roles of right-wing ideologies and gender role beliefs. Sex Roles 79, 206–217. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0860-x

Malhotra, N., and Kuo, A. G. (2008). Attributing blame: the public's response to Hurricane Katrina. The J. Poli. 70, 120–135. doi: 10.1017/S0022381607080097

Margalit, Y. (2013). Explaining social policy preferences: evidence from the great recession. Am. Poli. Sci. Rev. 107, 80–103. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000603

Mayer, N. (2015). The closing of the radical right gender gap in France? Fr Polit. 13, 391–414. doi: 10.1057/fp.2015.18

Mestre, M. V., Samper, P., Frías, M. D., and Tur, A. M. (2009). Are women more empathetic than men? A longitudinal study in adolescence. The Spanish J. Psychol. 12, 76–83. doi: 10.1017/S1138741600001499

Mize, T. D., Kaufman, G., and Petts, R. J. (2021). Visualizing shifts in gendered parenting attitudes during COVID-19. Socius 7, 23780231211013128. doi: 10.1177/23780231211013128

Moehring, K., Reifenscheid, M., and Weiland, A. (2021). Is the Recession a ‘Shecession'? Gender Inequality in the Employment Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Available online at: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/tzma5/ (accessed January 21, 2022).

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2015). Vox populi or vox masculini? Populism and gender in Northern Europe and South America. Pattern. Prej. 49, 16–36. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014197

Murray, D. R., and Schaller, M. (2012). Threat(s) and conformity deconstructed: perceived threat of infectious disease and its implications for conformist attitudes and behavior: Infectious disease and conformity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 42, 180–188. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.863

Norocel, O. C. (2011). Heteronormative constructions of romanianness: a genealogy of gendered metaphors in romanian radical-right populism 2000–2009. Debatte: J. Contemp. Central Eastern Europe 19, 453–470. doi: 10.1080/0965156X.2011.626121

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 922–934. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.504

Preston, S. D., and De Waal, F. B. M. (2002). Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav. Brain Sci. 25, 1–20. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X02000018

Reeskens, T., Muis, Q., Sieben, I., Vandecasteele, L., Luijkx, R., Halman, L., et al. (2021). Stability or change of public opinion and values during the coronavirus crisis? Exploring Dutch longitudinal panel data. Eur. Soc. 23, S153–S171. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1821075

Reichelt, M., Makovi, K., and Sargsyan, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes. Eur. Soc. 23, S228–S245. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1823010

Rendall, M. (2018). Female market work, tax regimes, and the rise of the service sector. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 28, 269–289. doi: 10.1016/j.red.2017.09.002

Riggs, J. M. (1997). Mandates for mothers and fathers: perceptions of breadwinners and care givers. Sex Roles 37, 565–580. doi: 10.1023/A:1025611119822

Rosenfeld, D. L., and Tomiyama, A. J. (2021). Can a pandemic make people more socially conservative? Political ideology, gender roles, and the case of COVID-19. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 51, 425–433. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12745

Schaller, M. (2006). Parasites, behavioral defenses, and the social psychological mechanisms through which cultures are evoked. Psychol. Inq. 17, 96–101. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1702_2

Schaller, M., and Park, J. H. (2011). The Behavioral Immune System (and Why It Matters). Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 99–103. doi: 10.1177/0963721411402596

Simas, E. N., Clifford, S., and Kirkland, J. H. (2020). How empathic concern fuels political polarization. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 258–269. doi: 10.1017/S0003055419000534

Steiber, N., Siegert, C., and Vogtenhuber, S. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Employment Situation and Financial Well-Being of Families With Children in Austria: Evidence From the First Ten Months of the Crisis. Available online at: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/r7ugz/ (accessed January 21, 2022).

Tavares, M. M. M., Gomes, D. B. P., and Fabrizio, M. S. (2021). COVID-19 She-Cession: The Employment Penalty of Taking Care of Young Children. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Tavits, M. (2007). Clarity of responsibility and corruption. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00246.x

Terrizzi, J. A., Shook, N. J., and McDaniel, M. A. (2013). The behavioral immune system and social conservatism: a meta-analysis. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.10.003

Toussaint, L., and Webb, J. R. (2005). Gender differences in the relationship between empathy and forgiveness. The J. Soc. Psychol. 145, 673–685. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.145.6.673-686

Van der Graaff, J., Carlo, G., Crocetti, E., Koot, H. M., and Branje, S. (2018). Prosocial behavior in adolescence: gender differences in development and links with empathy. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 1086–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0786-1

Wilkie, J. R. (1993). Changes in U.S. men's attitudes toward the family provider role, 1972-1989. Gender Soc. 7, 261–79. doi: 10.1177/089124393007002007

Zahn-Waxler, C., and Radke-Yarrow, M. (1990). The origins of empathic concern. Motiv. Emot. 14, 107–130. doi: 10.1007/BF00991639

Zamarro, G., and Prados, M. J. (2021). Gender differences in couples' division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Household 19, 11–40. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7

Keywords: COVID-19, gender roles, ideology, survey experiment, Western Europe

Citation: Lesschaeve C, Glaurdić J, D'Ambrosio C and Vögele C (2024) Gender roles and political ideology in the pandemic: experimental evidence from Western Europe. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1325138. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1325138

Received: 20 October 2023; Accepted: 19 December 2023;

Published: 09 January 2024.

Edited by:

Janina Onuki, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Ednaldo Ribeiro, State University of Maringá, BrazilSorina Soare, University of Florence, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Lesschaeve, Glaurdić, D'Ambrosio and Vögele. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christophe Lesschaeve, christophe.lesschaeve@uni.lu

Christophe Lesschaeve

Christophe Lesschaeve Josip Glaurdić

Josip Glaurdić Conchita D'Ambrosio2

Conchita D'Ambrosio2  Claus Vögele

Claus Vögele