A mirror of political ideology: undergraduates’ attitudinal drivers on implemented campus carry

- 1John Morton Center for North American Studies, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

- 2Faculty of Management and Business, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

- 3Department of Social Research, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

Campus carry, which allows individuals possessing a license (or, more recently, a right) to carry concealed firearms to legally bring them onto public university campuses, was implemented in Texas in 2016, but it has remained a contested issue at The University of Texas at Austin. Based on a survey of undergraduates (N = 1,204) conducted in spring 2019, this paper examines predictors of support and opposition for the policy, including gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, political affiliation and ideology, length of time lived in Texas, and pro-gun legal attitudes. The study found that attitudes were profoundly driven by the political views of the students. Their gender and pro-gun legal attitudes also had significance, whereas many other variables identified by previous research did not. The study contributes to an understanding of campus carry attitudes in situations where it is not only planned or a distant hypothetical but already in effect and impacting students’ lives.

1 Introduction

Reforms of U.S. gun laws have expanded the scope of how and where private citizens have an option for armed self-defense (Winkler, 2011; Spitzer, 2015; Yamane, 2017). In ten states, so-called campus carry laws have also forced public higher education institutions to accept that faculty, staff, and students legally permitted to carry a firearm can do so in a concealed manner on university premises. However reluctantly the universities (e.g., Harnisch, 2008) and campus populations (see Hassett et al., 2020) have welcomed these changes, public universities have had no choice to oblige. Nonetheless, attitudes on campus have drawn great scholarly interest. Existing studies have mostly addressed students or faculty but sometimes also staff (e.g., Patten R. et al., 2013; Patten R. P. et al., 2013), university presidents (Price et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2018), and law enforcement (De Angelis et al., 2017). A particular group of interest has been students, invited to answer dozens of surveys. Most studies on students’ attitudes have investigated the prospect of the law being implemented at universities (Cavanaugh et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013a,b; Jang et al., 2014). Many have found value in targeting universities where such a law might be passed in the future, including Georgia, where it was later legalized in 2017 (Bennett et al., 2012); the University of Florida, which it is still projected but has not yet passed (Shepperd et al., 2018); and a university in Missouri (Jang et al., 2014) or one in Pennsylvania (Hassett and Kim, 2021), both being places where campus carry law has not passed yet. Others have polled multiple universities, even in different states (Cavanaugh et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013a,b; Dahl et al., 2016; Watson et al., 2018).

Recently, analyses have also started to be published on attitudes at universities where the policy has already been implemented. Therefore, it is important to differentiate between pre-implementation expectations and the opinions formed after actual implementation, which provide results on the basis of lived experience. In addition to replicating classic attitude surveys (e.g., Nodeland and Saber, 2019), some have expanded on the analytical spectrum, thus deepening understandings on attitudinal differences and how university members are adapting to the potential presence of guns around them. Such studies include Hayes et al. (2021) on the attitudinal differences between those who support the law and those who actually carry on campus, McMahon-Howard et al. (2020) on factors differentiating campus groups, Scherer et al. (2021) on how pro-gun attitudes may obscure the perception of negative impacts of campus carry, and Ruoppila and Butters (2021) on how the views of supporters or opponents are not necessarily black-and-white, indicating nuanced understandings and preferences around a complex issue (see also Kyle et al., 2017).

Our empirical study here is on attitudes at The University of Texas at Austin. In 2016, Texas became the eighth state in the United States to allow students, faculty, and staff with a license to carry to enter public university premises with a concealed handgun. In Texas, concealed carry law permits individuals of at least 21 years of age with the required training to keep a handgun on their person, provided that it is not visible to others (since September 2021, constitutional carry applies in Texas, which means that a license is no longer required; the age limit still stands, as does the requirement to carry concealed on campus). Campus carry law removed previous restrictions on movement, extending guns to open spaces, libraries, study halls, and classrooms of public universities. While academic communities in Texas reacted differently to this change, nowhere was opposition more strongly pronounced than at UT Austin, located in the state’s capital. Opponents of the law expressed strong concerns about increased violence on campus and the inability of guns to prevent a mass shooting, echoing views supported by research (Webster et al., 2016). Yet, despite the fact that universities are comparatively safe in comparison to other areas (Boss, 2018), more than half of directed attacks on U.S. college campuses have involved firearms (Drysdale et al., 2010). This fact is all too poignant at UT Austin, where the first mass university shooting in the nation in 1966 left more than a dozen people dead, and where homicides of students in recent years have raised alarm among the campus community (Fausset and Santa Cruz, 2010; Watkins, 2017).

In this paper, the research question concerns undergraduates’ attitudinal drivers on campus carry implemented at The University of Texas at Austin. We seek to advance the discussion on attitudes surrounding campus carry by providing increased granularity on the relative significance of the most commonly recognized attitudinal drivers, as well as those suggested by recent work, such as acculturation and pro-gun legal attitudes. The paper adds to the empirical body of work studying the post-implementation phase, that is, when the law is in effect and potentially impacting students’ lives.

2 Previous research and current study

Previous research has identified a number of factors as potential predictors for support of campus carry, including political ideology, gun socialization, gender, race, perceptions of safety, fear of crime, and previous victimization. Recent studies have suggested some additional factors, including regional socialization as well as personal gun attitudes instead of growing up exposed to firearms.

An ample number of studies have linked sentiments around handguns on campus to political ideology or party affiliation, with those identifying as conservative or Republican being much more likely to support campus carry (Bennett et al., 2012; Bouffard et al., 2012; Cavanaugh et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013b; Jang et al., 2014; De Angelis et al., 2017; Schildkraut et al., 2018). This is hardly surprising, taking into account studies on the US population overall. Wozniak (2017) has argued that the strongest, most consistent predictors of people’s opinions about gun control are political, with conservatives and moderates being significantly more likely than liberals to oppose any gun control laws. Similarly, Republicans and Independents are much more likely than Democrats to say that gun control laws should be kept as they are rather than made stricter (Wozniak, 2017). Furthermore, gun ownership in the United States follows party lines, with Republicans being twice as likely as Democrats to own a firearm (Parker et al., 2017).

Regarding demographic factors as significant predictors, gender has been found to consistently correlate to opinions on campus carry (Bennett et al., 2012; Cavanaugh et al., 2012; Jang et al., 2014). More specifically, women have been less likely to support guns on campus than men (Bennett et al., 2012; Patten R. et al., 2013; Patten R. P. et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013b; Price et al., 2014; Dahl et al., 2016; De Angelis et al., 2017; Kyle et al., 2017; Schafer et al., 2018). In some cases, race has also been identified as a predictor for campus carry, with white people being more likely to support guns on campus (see Kyle et al., 2017 on a Midwestern university; Miller et al., 2002). Watson et al. (2018) found, however, that in a range of states (California, New Mexico, Massachusetts, Colorado, Illinois, and Michigan), non-white people were more than twice as likely to support trained staff and faculty carrying firearms. In studies at fifteen universities (Thompson et al., 2013b) or at a university in Missouri (Jang et al., 2014), race was not revealed to be a significant predictor of support for campus carry. Finally, socio-economic status has seldomly been brought out as a potential factor (Jang et al., 2014).

Many studies have also focused on safety, albeit addressing many different aspects. For some, guns on campus are perceived as a threat to personal safety. For others, they are regarded as the means to increase security. Connecting fear of crime and campus carry support, one view is that guns are symptoms, with fear of crime driving gun ownership (Kleck et al., 2011; Hauser and Kleck, 2013); alternatively, the palliative perspective argues that gun ownership leads people to feel less afraid (amongst others, see Hauser and Kleck, 2013). Dowd-Arrow et al. (2019) differentiate between these two but show that they are not mutually exclusive. The question of safety is a complex issue, involving actual victimization, perceived risk of victimization, and confidence in campus police’s capacity to prevent harmful events, for example (see McMahon-Howard et al., 2020, p. 141).

Socialization has been discussed from two angles. On one hand, socialization in a gun culture in one’s family when growing up, usually measured as whether the family owned a gun or if guns were present, has been claimed to contribute to support of campus carry (e.g., Thompson et al., 2013b; Jang et al., 2014). Many studies have also found that those who own guns were more supportive of the policy (Bennett et al., 2012; Patten R. et al., 2013; Patten R. P. et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013a,b; Schildkraut et al., 2018; Shepperd et al., 2018). While gun ownership in the United States is relatively common, protection of oneself and protection of one’s family have become increasingly important reasons for ownership, compared to traditional activities such as hunting or sports (Parker et al., 2017). Accordingly, Shepperd et al. (2018) suggest that owning a gun for self-protection leads to a greater attitudinal difference than gun ownership per se. In a post-implementation study by Hayes et al. (2021), students who believed that ensuring their personal safety was their own responsibility were more likely to support campus carry.

On the other hand, two recent papers point to what might be called regional socialization. This effect was particularly noted by Schildkraut et al. (2018), comparing the attitudes of university students in Georgia versus New York, with the former being much more gun-positive and the latter being more critical and restrictive. In another study, Luo and Shi (2022) studied attitudes at a research institute on the U.S.-Mexico border. While those with origins on the Mexican side were considered to have been socialized into a culture that tends to be more critical of guns, Mexican-born respondents who had adapted to U.S. culture were more likely to support campus carry.

While many early studies on students’ campus carry attitudes merely identify which factors shape attitudes (e.g., Thompson et al., 2013b), other studies have also applied various types of multivariate analysis to explain the relationships between specific—and somewhat disparate—variables, yielding different results except for the shared significance of political beliefs. For instance, Jang et al. (2014) found that political orientation and gun socialization (growing up in a family with guns) have the most significant role in perceived risk of criminal victimization. For Schildkraut et al. (2018), the most powerful aspects were political orientation and regional socialization. In a post-implementation study, Nodeland and Saber (2019) found that owning a firearm and political orientation were the two most important factors. Hassett and Kim (2021) highlighted the importance of political beliefs but also gender and race, as white people and males were more likely to hold more favorable attitudes. For Schafer et al. (2018), gender was the most important factor; females were less likely to support the policy.

The first post-implementation analyses have offered results on attitudes based on lived experience but also broadened and refined the analytical spectrum in the search for an increased understanding of attitudinal differences, their formation, and their significance for perceived safety and campus life. Hayes et al. (2021) compared the attitudinal drivers of those students who supported campus carry versus those who had actually carried a concealed firearm on campus premises. The study took place at a university in the Southeast, where more than half (58%) of the sampled students supported campus carry and 7 percent reported that they had carried a concealed weapon on campus since the legislation came into force. Regarding the drivers identified in previous research, voting behavior and gender were the only variables that predicted both attitudinal support for campus carry and actual concealed carry behavior. When campus carry support was controlled for, students who were confident in the campus police’s ability to prevent crime were less likely to engage in concealed carry. Furthermore, when attitudinal support for concealed carry was controlled for, voting behavior no longer predicted concealed carry. All this points to the importance of effective campus safety protocols.

McMahon-Howard et al. (2020) draw attention to the significance of legal attitudes in their study on the difference of attitudinal factors between faculty, administrators, staff, and students. This study was conducted at a large public university in Georgia, where a majority (57%) of students again supported campus carry. Even when controlling for other factors, especially political ideology, pro-gun legal attitudes increased the likelihood of support for campus carry among all groups. As expected, family socialization to guns and having a concealed carry permit also increased the students’ likelihood to support campus carry.

Scherer et al. (2021) discuss the relationship of attitudinal differences and lived experience of campus carry. Conducted with a relatively large sample at a large public university in Georgia, their study found that faculty and students inclined toward fear of victimization and perceptions that campus was unsafe also reported more negative impacts of campus carry. In other words, Black and Hispanic students, females, and students with disabilities—the groups with proportionally greater feelings of vulnerability—were disproportionately impacted by the law, further increasing their safety concerns. Meanwhile, faculty and students who reported greater pro-gun attitudes reported less impacts of campus carry, if not increased security. Moreover, the study maintained that previous gun socialization also mattered in how campus carry impacts were identified in the first place.

In an earlier paper, Ruoppila and Butters (2021) have shown that two and half years after implementation, campus carry continued to be a hotly contested issue among the undergraduates at The University of Texas at Austin: 71 percent opposed the law, 24 percent supported it, and only 5 percent did not have an opinion. Most undergraduates (72%) also thought that it is an important matter. In many students’ minds, campus carry was negatively associated with well-known concerns regarding public health (see also Webster et al., 2016) and the “chilling” of the learning environment (see LaPoint, 2010; Butters, 2021), mirroring findings similar to those in Kansas (Wolcott, 2017). However, we also discovered that not all the views of the supporters or the opponents were so clear-cut. The results suggested that a large share of the opponents specifically resisted carrying on campus, rather than concealed carry in general. On the other hand, some supporters preferred stricter limitations on the policy than what currently exists at UT Austin (see Ruoppila, 2021).

The current study examines campus carry attitudes among undergraduates at The University of Texas at Austin. The two research questions are: (1) what are the drivers of campus carry attitudes among undergraduate students (with the law being in effect), and (2) what is the respective magnitude of their impact? Our study contributes to the discussion by being among the first analyses to examine attitudes as “lived experience.” Another contribution is that we were able to test not only the attitudinal drivers identified in previous research but also some that have been pointed to only more recently, such as regional socialization and pro-gun legal attitudes. A third contribution is our use of a multivariate method that not only differentiates statistical significance but is also able to control for several factors simultaneously.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Sample and fielding methodology

The data is drawn from a survey collected originally by the research team in February–March 2019 among UT Austin undergraduate students. The sample (N = 1,204) is generally representative of the university’s undergraduate student body in terms of areas of study, gender, ethnicity, and age. More women (61.2%) completed the survey than men (36.3%); in addition, 1.6% self-identified as non-binary or other. This prevalence is comparable to other surveys on campus carry (e.g., Bennett et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013b; Jang et al., 2014). It should be noted, however, that more women (54%) attend UT Austin than men (46%) (IES > NCES 2018). In terms of ethnic representation, there was very close correlation between the survey sample and the student body at UT Austin: 45.3% identified as White (compared to 40% of the student body), 20.1% as Asian (22%), 19.7% as Latinx (23%), 5.7% as Black (4%), and 7.3% as mixed (4%). Students at all years of study were included in the survey: freshmen (38%), sophomores (22.1%), juniors (20.3%), and seniors (19.7%). The mean age of the sample matches UT Austin’s young undergraduate student body; two-thirds (67%) of UT Austin’s undergraduates are aged 18 to 21, with a mean age of 20. The questions on age and Texas residency used exact year of birth and years lived in the state rather than answer options with predefined ranges. After incomplete and incidental non-qualified answers (e.g., graduate students) were filtered out of the total data set (1,248 respondents), the sample reflects approximately 2.9% of the undergraduate student body of UT Austin (41,306) (IES > NCES 2018). Using a 98% confidence level on this sample size yields a 3.3% margin of error.

The students were polled in the classroom. Several months before, professors were emailed with a request to visit their class. Selection of professors was made from UT Austin’s online Course Catalog (Spring 2019) and various departments’ websites. Specific focus was first paid to recruiting so-called flag courses, large survey classes with cross-registration across disciplines, and core courses that fulfill the statewide curriculum of Texas. After this, in order to achieve better representativeness, we solicited professors with small classes containing upper-class students. Over a four-week period (February 7–March 4, 2019), the survey was administered in 23 courses, ranging from small seminars to large lecture classes. Professors allowed the researchers to introduce themselves, the goals of the project, and the anonymous nature of the data collection. The students had 15 minutes to complete the survey under the supervision of the researchers, who ensured that students did not engage in conversation or discuss the survey. In addition, students were instructed not to participate if they had already done so in a previous class. Students were able to fill out the survey online by using their smartphone, tablet, or laptop; those without such a device were provided with a paper copy, whose results were later input by the researchers into the electronic database. Because this study sought to gauge the knowledge of the students on campus carry, no explanatory or background information was provided on the topic before the survey was conducted. The survey instrument consisted of 65 questions.

There are potential limitations with the survey. As is always a risk in self-reporting of opinions, especially on sensitive topics such as past history of violence and guns, it is possible that some students answered “no opinion” due to fear of being connected with their responses, even though the survey was introduced as anonymous and had no means of tracing. The larger sample size was intended to reduce potential response bias, and control questions were also asked to validate answers. To ensure representativeness of the UT Austin student body and achieve a statistically significant sample, rather than using nonprobability convenience sampling (e.g., polling random students on campus, email lists), the researchers conducted purposive heterogeneity sampling of undergraduates at all levels of study, from freshmen to seniors, and ethnicity across a range of fields, from the arts to the sciences.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Outcome: support for or opposition to campus carry

Level of support for campus carry was used as a dependent variable for this study. The question “Do you currently support or oppose guaranteeing the right of faculty, staff, and students to carry concealed handguns on college campuses?” was measured on a Likert scale; the answer categories included: (1) Strongly support, (2) Somewhat support, (3) Somewhat oppose, (4) Strongly oppose, and (5) No opinion. These results were then recoded to a binary of support or opposition for the law.

3.2.2 Predictors

This study included three thematic areas used for independent variables: political attitudes (party identification), perceptions of safety (feelings of safety on campus in general, effect of campus carry on perceptions of safety, and trust in the capability of law enforcement to react in time to a crime situation), and socialization with gun culture (whether the respondent had firearms in their childhood home, whether they currently owned a gun, opinion on Second Amendment rights, and regional socialization, including length of Texas residency and if they attended high school in Texas). Also measured were political ideology, perceptions of safety, and the question if people should be able to exercise their Second Amendment rights.

Regional socialization (Schildkraut et al., 2018; Luo and Shi, 2022) could be significant in a state like Texas, which is stereotypically associated with having a strong gun culture. While the admittedly high numbers of gun ownership in Texas are by no means outstanding (Parker et al., 2017), for granularity on the potential difference of opinions on guns held by those born and/or raised in Texas, respondents were asked about how many years they had lived there, calculated against birth year, to also determine if they were residents during high school; this also made it possible to differentiate between those UT Austin undergraduates who were from out of state.

3.2.3 Sociodemographic control variables

In addition, a number of variables captured demographic data. These included age, gender, ethnic identity, and socioeconomic background. In terms of the latter, respondents were asked to self-identify as one of the following: (1) Working class, (2) Lower middle class, (3) Middle class, (4) Upper middle class, (5) Upper class, or (6) Not applicable. Surprisingly, socioeconomic background has rarely been asked in previous surveys, and neither has it been regarded as a significant factor in multivariate analysis (e.g., Jang et al., 2014).

3.2.4 Political ideology and party identification

We measured the political leaning of a respondent with several question items. First, the respondents defined their political ideology on a 7-point Likert scale: (1) Extremely liberal, (2) Somewhat liberal, (3) Leaning liberal, (4) Moderate, (5) Leaning conservative, (6) Somewhat conservative, and (7) Extremely conservative, with an additional answer option of “No opinion.” Second, we asked the party identification of the respondents. As expected, the vast majority of Democrats (87%) considered themselves to be liberal; conversely, Republicans (75%) were conservative. Independents were more split (52% self-identified as liberal, 34% as moderate, and 11% as conservative), as were Libertarians (48% were liberal, 23% were moderate, and 27% were conservative). Thus, to avoid multicollinearity problems, the measures of political ideology and party identification were added in the separate models. Third, to further nuance the ideological stances of the students, the survey asked a set of “barometer” questions on various ideological hot-button issues (e.g., the death penalty, abortion, and the border wall proposed by President Trump).

3.2.5 Data analysis: logistic regression

We explore the impact of our predictors on our outcome variable—that is, support for campus carry—through three binary logistic regression models. In the first model (Model 1), the predictors describe the sociodemographic data of the respondent (age, gender, ethnic identity, socioeconomic background, and whether they went to high school in Texas). In the second model (Model 2), we add predictors related to political attitudes (party identification), relationship to firearms (whether the respondent owned firearms or had them in their childhood home), feeling of safety on campus (in general and after campus carry law, as well as trust in the capability of law enforcement to react to a crime on time), and attitude toward Second Amendment rights. The third model (Model 3) is similar to the second except that party identification is replaced by political ideology.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics and comparisons

Sociodemographically speaking, the data is predominantly comprised of younger respondents, in accord with the undergraduate sample. The ethnic identity of almost half of the respondents is White, also resembling the student body at UT Austin. Over 60 percent of the respondents identify as Democrats, and over half define themselves as somewhat liberal or extremely liberal. Despite the fact that the undergraduate student body of UT Austin comes from diverse parts of the red state of Texas, it leans liberal, matching the dominant ideology found in the capital region of Travis County (Jones, 2019).

Regarding firearms, 40 percent of the respondents had them in their childhood home, while 60 percent did not. However, only 10 percent reported currently owning one firearm or more. Of course, the relatively young age of the respondents must be taken into account here. In Texas, one has to be 21 years old to obtain a permit to concealed carry on campus. Furthermore, even though underage students (and even minors) may legally own a handgun, they cannot keep it in their dormitory; this also applies to those with a concealed carry permit. Although a quarter of students polled supported campus carry, only 1.2 percent of undergraduates had a license to carry and less than 1 percent had actually carried on campus; however, a substantially larger group had plans to get a license to carry, reflecting that many undergraduates had yet to come of required age (see Ruoppila and Butters, 2021).

Among those students who own one gun or more, the majority (61%) favor the law. This level of support may not appear as strong as one might expect, however. An explanation for this is that not all gun owners own for defensive purposes or feel the need to carry outside of their home. Given the necessity to differentiate between those who own a gun for protection and others (Shepperd et al., 2018), our survey asked those respondents who owned a gun (11%) why they do. They reported a range of motives. Hunting was the most pronounced reason to own a gun (56%), while a gun hobby was also quite common (50%). On the other hand, owning a gun was also explained by a perceived need for protection, either for oneself (54%), one’s family (54%), or the community (20%). For many, there was also an ideological aspect to their decision: while the majority of UT Austin undergraduates (66%) agreed that people should be able to exercise their Second Amendment rights, nearly a half (43%) of gun owners expressed that this was an actual reason for them to have a firearm. Finally, a small segment of gun owners (11%) had a firearm for some other reason (e.g., it was a gift or inherited).

In terms of security, the great majority of students (84%) felt very or rather safe on campus, but almost 60 percent said that campus carry law has strongly decreased or decreased their feeling of safety. Moreover, over half of the respondents agreed with the statement that it takes too long for law enforcement or security personnel to respond to a crime situation.

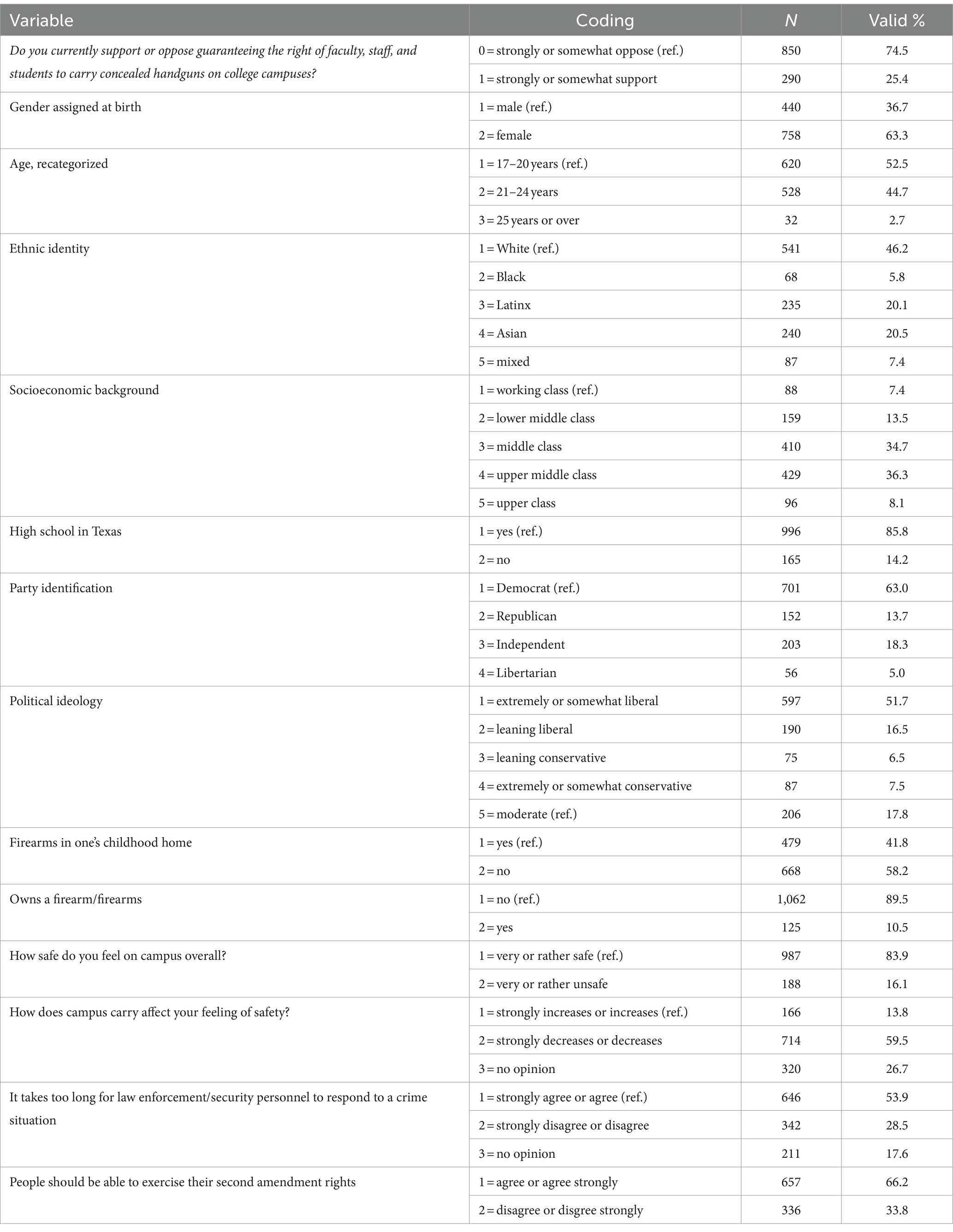

Table 1 shows the frequencies of the variables included in the analysis.

4.2 Multivariate analyses on attitudes toward campus carry

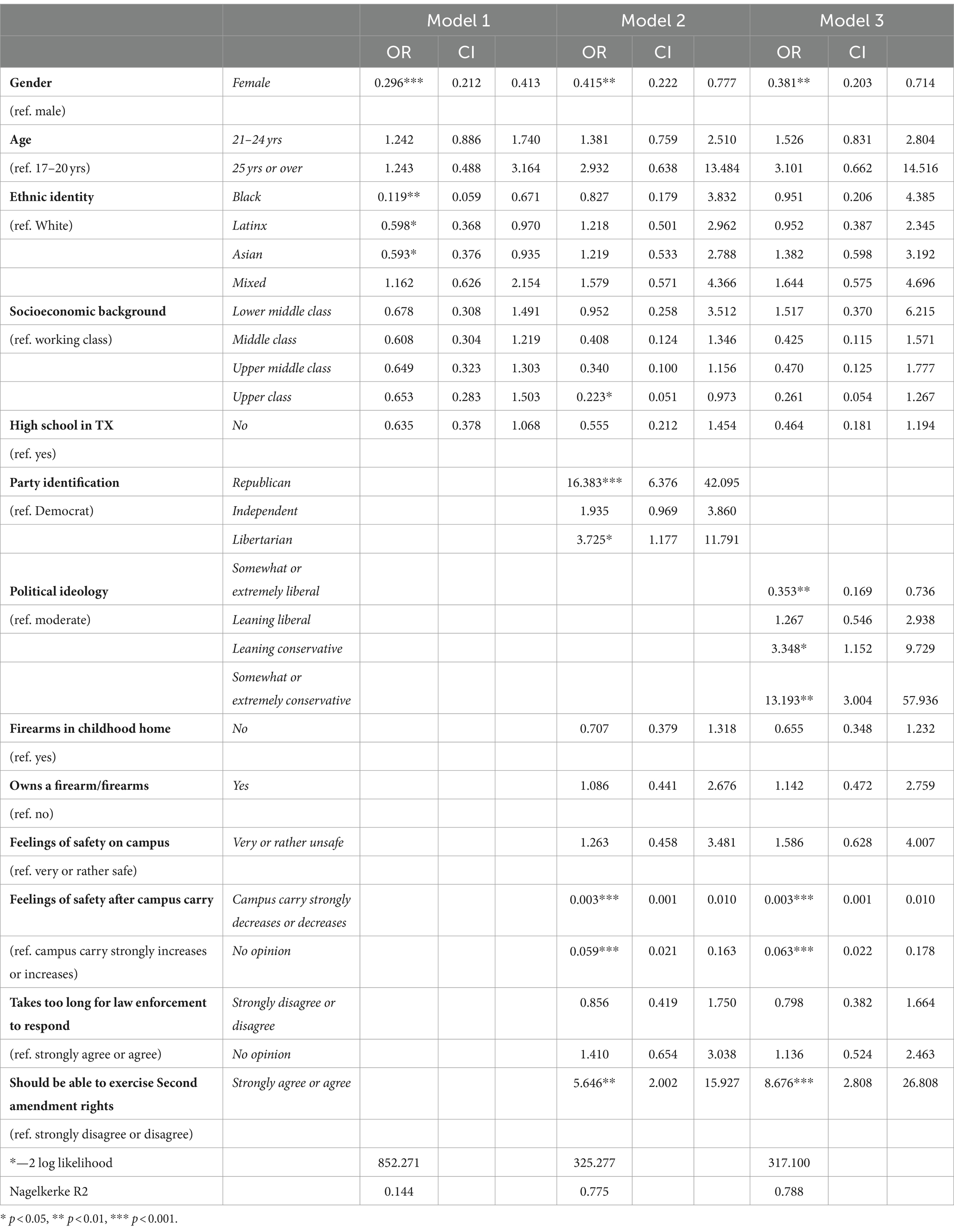

In Table 2, Model 1 shows that female students are significantly less likely to support campus carry than their male peers. This difference persists also in Models 2 and 3, even after controlling for the other predictors. As for age, no significant attitudinal differences appear, which is hardly surprising considering the youth and minor overall age differences of the respondents. In a similar vein, socioeconomic background does not seem to have an impact on the campus carry attitudes among students. The only exception is that in Model 2, students with an upper-class background are more likely to oppose campus carry than those with a working class background. This relationship disappears in Model 3 and is likely related to the small number of upper-class background respondents (N = 96). Nor does growing up in Texas (and going to high school there) have an impact.

Table 2. Predictors explaining support for campus carry law: binary logistic regression (odds ratios/confidence intervals).

Interestingly, ethnic identity has a clear role in attitudes toward campus carry, but only in Model 1. Those who self-identify as White are significantly more likely to support campus carry than those who self-identify as Black, Latinx, Asian, or mixed. However, this difference disappears when we control for the other predictors in Models 2 and 3.

The small role of other factors is explained by the significant explanatory power of party identification and political ideology. Republican affiliation dramatically increases support of the law: this group is 16.4 times more likely to support campus carry than those who identify as Democrats. Furthermore, Libertarians are almost four times more likely to support campus carry than Democrats. A similar pattern can be found in terms of political ideology. Compared to moderates, those students who are extremely or somewhat liberal are significantly more likely to oppose campus carry. No difference exists between moderates and those leaning liberal. On the other hand, compared to moderates, conservatives express support for the law: those leaning conservative are three times more likely to support campus carry, and those who are somewhat or extremely conservative are over thirteen times more likely.

Ownership of a firearm or former experience of firearms in one’s childhood home does not appear to have an impact on the attitude on campus carry, nor does the general feeling of safety on campus or evaluations of the capability of law enforcement to react in a crime situation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, those who feel that campus carry decreases the feeling of safety on campus tend to oppose the law; this is seen in both Models 2 and 3. Importantly, the attitude toward Second Amendment rights is a significant predictor of campus carry attitude. Those students who agree or strongly agree that people should be able to exercise their Second Amendment rights are over eight times more likely to support campus carry.

5 Discussion

While most previous studies agree that there is a statistically significant link between students’ political stance and attitudes toward campus carry (Bouffard et al., 2012; Bennett et al., 2012; Cavanaugh et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013b; Jang et al., 2014; De Angelis et al., 2017; Schildkraut et al., 2018), our study contributes to the field by underlining the powerfulness of the influence. It is very much the case that attitudes on campus carry mirror students’ political ideology. Students identifying as Republicans were sixteen times more likely to support campus carry than those identifying as Democrats. The situation on campus reflects that of the broader society; in the United States, the most consistent predictors of people’s gun control preferences are their political beliefs and affiliations (Wozniak, 2017). Given that the situation at UT Austin is about the students’ own immediate surroundings and place to study, and a location that has been a focal point of recent political controversy, the stances may appear even more pronounced. After all, the whole campus carry phenomenon is thoroughly political, being an invention of gun control deregulation proponents (Arrigo and Acheson, 2016), and in many states it has come as a result of prolonged political contention (see Short, 2019). It is not driven by the safety concerns of particular campuses; nor is it an initiative put forward by higher educational institutions themselves, instead being the opposite (e.g., Harnisch, 2008; Hassett et al., 2020).

Regarding gun politics in the United States, the main divisive question between the two political camps has not been whether civilians should be allowed to carry a gun in the first place, but involving details of regulation, such as whether semiautomatic weapons should be banned from civilians or whether background checks should be required of potential gun buyers (Wozniak, 2017). Whether the right to carry should be extended to campuses can be considered one such regulation (Birnbaum, 2013). Within the sphere of political ideas, our results support the findings of McMahon-Howard et al. (2020) on the significance of pro-gun legal attitudes above and beyond political views when it comes to campus carry. Even when controlling for other factors, especially political affiliation or ideology, the support for people to be able to exercise their Second Amendment right had a statistically significant role in opinions of support for campus carry, notwithstanding a number of respondents who supported the Second Amendment but would have preferred that campus remain off-limits from firearms.

The overwhelming impact of political attitudes was also shown in that most sociodemographic factors (e.g., race), which some previous studies have suggested to matter (e.g., Kyle et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2018; Hassett and Kim, 2021), lost their significance when political attitudes (party identification or political ideology) were taken into account. Nonetheless, one persisted: female students were significantly less likely to support campus carry than their male peers. This result echoes many earlier studies (e.g., De Angelis et al., 2017; Kyle et al., 2017; Schafer et al., 2018; Hassett and Kim, 2021). A major difference from other studies, however, was that gun socialization (e.g., Jang et al., 2014), regional socialization (Schildkraut et al., 2018; Luo and Shi, 2022), or currently owning a gun (Bennett et al., 2012; Patten R. et al., 2013; Patten R. P. et al., 2013; Schildkraut et al., 2018; Shepperd et al., 2018) did not have an impact among UT Austin students when political views were taken into account. The comprehensive nature of the survey conducted and the method that enabled controlling for several factors underline the significance of these results.

The profoundly political character of campus carry, as well as that of attitudes toward it, suggest difficulties ahead in searching for compromises, especially where implementation is obligatory (Arrigo and Acheson, 2016; Scherer et al., 2021). However, as attitudes regarding campus carry point to political principles rather than actual carrying behavior (Hayes et al., 2021; Ruoppila and Butters, 2021) or practical limitations on campus grounds (see Ruoppila and Butters, 2021), some compromises concerning exactly which campus spaces guns can be brought to may be negotiable to a certain extent.

6 Conclusion

This article has contributed to the literature on guns and campuses by showing that the correlation between students’ political stances and attitudes toward campus carry far exceeds the influence of other factors. It also confirmed the independent significance of pro-gun legal attitudes, measured by support for people to exercise their Second Amendment rights, when it comes to supporting campus carry. Regarding other factors, only gender was found to have statistical significance: female students are significantly less likely to support campus carry than males. On the contrary, when political views were controlled for, gun socialization, regional socialization, or currently owning a gun were not found to have an impact.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found online via the following link: https://services.fsd.tuni.fi/catalogue/FSD3690.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Sciences at the University of Turku. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. EK-K: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. SR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Academy of Finland, grant number 310568.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arrigo, B. A., and Acheson, A. (2016). Concealed carry ban and the American college campus: a law, social sciences, and policy perspective. Contemp. Justice Rev. 19, 120–141. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2015.1101688

Bennett, K., Kraft, J., and Grubb, D. (2012). University faculty attitudes toward guns on campus. J. Crim. Justice Educ. 23, 336–355. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2011.590515

Birnbaum, R. (2013). Ready, fire, aim: the college campus gun fight. Change Magaz. High. Learn. 45, 6–14. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2013.812462

Boss, S. K. (2018) Guns and college homicide: The case to prohibit firearms on campus. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Bouffard, J. A., Nobles, M. R., Wells, W., and Cavanaugh, M. R. (2012). How many guns? Estimating the effect of allowing licensed concealed handguns on a college campus. JIV 27, 316–343. doi: 10.1177/0886260511416478

Butters, A. M. (2021). Fear in the classroom: campus carry at the University of Texas at Austin. Texas Educ. Rev. 9, 50–63. doi: 10.26153/tsw/11418

Cavanaugh, M. R., Bouffard, J. A., Wells, W., and Nobles, M. R. (2012). Student attitudes toward concealed handguns on campus at 2 universities. Am. J. Public Health 102, 2245–2247. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300473

Dahl, P. P., Bonham, G. Jr., and Reddington, F. P. (2016). Community college faculty: attitudes toward guns on campus. Commun. Coll. J. Res. Pract. 40, 706–717. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2015.1124813

De Angelis, J., Benz, T. A., and Gillham, P. (2017). Collective security, fear of crime, and support for concealed firearms on a university campus in the Western United States. Crim. Justice Rev. 42, 77–94. doi: 10.1177/0734016816686660

Dowd-Arrow, B., Hill, T. D., and Burdette, A. M. (2019). Gun ownership and fear. SSM Popul. Health 8, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100463

Drysdale, D. A., Modzeleski, W., and Simon, A. B. (2010). Campus attacks: Targeted violence affecting institutions of higher education. U.S. secret service, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Safe and Drug-Free Schools, U.S. Department of Education, and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice (Washington, D.C.), Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/campus-attacks.pdf

Fausset, R., and Santa Cruz, N. (2010). Student opens fire at University of Texas, then kills himself. Los Angeles Times. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-sep-29-la-na-university-texas-shooting-20100929-story.html

Harnisch, T. L. (2008). Concealed weapons on state college campuses: In pursuit of individual liberty and collective security. American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU): A Higher Education Policy Brief. Available at: http://www.aascu.org/workarea/downloadasset.aspx?id=4545

Hassett, M. R., and Kim, B. (2021). Campus carry attitudes revisited: variations within the university campus community. J. Sch. Violence 20, 323–335. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2021.1907586

Hassett, M. R., Kim, B., and Seo, C. (2020). Attitudes toward concealed carry of firearms on campus: a systematic review of the literature. J. Sch. Violence 19, 48–61. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2019.1703717

Hauser, W., and Kleck, G. (2013). Guns and fear: a one-way street? Crime Delinq. 59, 271–291. doi: 10.1177/0011128712462307

Hayes, B. E., Powers, R. A., and O’Neal, E. N. (2021). What’s under the regalia? An examination of campus concealed weapon carrying behavior and attitudes toward policies. J. Sch. Violence 20, 101–113. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2020.1839475

Jang, H., Lee, C.-L., and Dierenfeldt, R. (2014). Who wants to allow concealed weapons on the college campus? Secur. J. 27, 304–319. doi: 10.1057/sj.2012.31

Jones, M. P. (2019). A more progressive Texas: From Travis County to Smith County. TribTalk: Perspectives on Texas. Available at: https://www.tribtalk.org/2019/08/12/a-more-progressive-texas-from-travis-county-to-smith-county/

Kleck, G., Kovandzic, T., Saber, M., and Hauser, W. (2011). The effect of perceived risk and victimization on plans to purchase a gun for self-protection. J. Crim. Just. 39, 312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.03.002

Kyle, M. J., Schafer, J. A., Burruss, G. W., and Giblin, M. J. (2017). Perceptions of campus safety policies: contrasting the views of students with faculty and staff. Am. J. Crim. Justice 42, 644–667. doi: 10.1007/s12103-016-9379-x

LaPoint, L. A. (2010). The up and down battle for concealed carry at public universities. J. Stud. Aff. 19, 16–21.

Luo, F., and Shi, W. (2022). Frontline support for concealed carry on campus, a case study in a border town. Am. J. Crim. Justice 47, 98–116. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09565-x

McMahon-Howard, J., Scherer, H., and McCafferty, J. T. (2020). Concealed guns on college campuses: examining support for campus carry among faculty, staff, and students. J. Sch. Violence 19, 138–153. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2018.1553717

Miller, M., Hemenway, D., and Wechsler, H. (2002). Guns and gun threats at college. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 51, 57–65. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596331

Nodeland, B., and Saber, M. (2019). Student and faculty attitudes toward campus carry after the implementation of SB11. Appl. Psychol. Crim. Justice 15, 157–170.

Parker, K., Horowitz, J., Igielnik, R., Oliphant, B., and Brown, A. (2017). America’s complex relationship with guns. Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Patten, R. P., Thomas, M. O., and Viotti, P. (2013). Sweating bullets: female attitudes regarding concealed weapons and the perception of safety on college campuses. Race Gender Class 20, 269–290. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43496945

Patten, R., Thomas, M. O., and Wada, J. C. (2013). Packing heat: attitudes regarding concealed weapons on college campuses. Am. J. Crim. Justice 38, 551–569. doi: 10.1007/s12103-012-9191-1

Price, J. H., Thompson, A., Khubchandani, J., Dake, J., Payton, E., and Teeple, K. (2014). University presidents’ perceptions and practice regarding the carrying of concealed handguns on college campuses. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 62, 461–469. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.920336

Ruoppila, S. (2021). Hiding the unwanted: a university-level campus carry policy. High. Educ. 83, 1241–1258. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00740-5

Ruoppila, S., and Butters, A. M. (2021). Not a “nonissue”: perceptions and realities of campus carry at the University of Texas at Austin. J. Am. Stud. 55, 299–311. doi: 10.1017/S0021875820001425

Schafer, J. A., Lee, C., Burruss, G. W., and Giblin, M. J. (2018). College student perceptions of campus safety initiatives. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 29, 319–340. doi: 10.1177/0887403416631804

Scherer, H. L., McMahon-Howard, J., and McCafferty, J. T. (2021). Examining the extent and predictors of the negative impacts of a campus carry law among faculty and students. Sociol. Inq. 92, 127–152. doi: 10.1111/soin.12453

Schildkraut, J., Jennings, K., Carr, C. M., and Terranova, V. (2018). A tale of two universities: a comparison of college students’ attitudes about concealed carry on campus. Secur. J. 31, 591–617. doi: 10.1057/s41284-017-0119-9

Shepperd, J. A., Pogge, G., Losee, J. E., Lipsey, N. P., and Redford, L. (2018). Gun attitudes on campus: united and divided by safety needs. J. Soc. Psychol. 158, 616–625. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2017.1412932

Short, A. (2019). Sane gun policy from Texas: a blueprint for balanced state campus carry Laws. NEULR 11, 401–473. Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1325

Spitzer, R. J. (2015). Guns across America: Reconciling gun rules and rights. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, A., Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., and Teeple, K. (2013a). Faculty perceptions and practices regarding carrying concealed handguns on university campuses. J. Commun. Health 38, 366–373. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9626-0

Thompson, A., Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., Teeple, K., Bassler, S., Khubchandani, J., et al. (2013b). Student perceptions and practices regarding carrying concealed handguns on university campuses. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 61, 243–253. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.799478

Watkins, M. (2017). UT police search for motive in student's stabbing spree. The Texas Tribune. Available at: https://www.texastribune.org/2017/05/01/ut-police-search-motive-students-stabbing-spree/

Watson, R. A., Guzman, M., and Scheel, B. (2018). To arm or not to arm—the divergence of policy from opinion on arming faculty and staff on U.S. college campuses. Sociol. Anthropol. 6, 672–676. doi: 10.13189/sa.2018.060806

Webster, D. W., Donohue, J. J., Klarevas, L., Crifasi, C. K., Vernick, J. S., Jernigan, D., et al. (2016). Firearms on college campuses: Research evidence and policy implications. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins, Bloomberg School of Public Health & Center for Gun Policy and Research.

Winkler, A. (2011). Gunfight: the battle over the right to bear arms in America. New York: W.W. Norton.

Wolcott, C. M. (2017). The chilling effect of campus carry: how the Kansas campus carry statute impermissibly infringes upon the academic freedom of individual professors and faculty members. Kans. Law Rev. 65, 875–911. doi: 10.17161/1808.25573

Wozniak, K. H. (2017). Public opinion about gun control post–Sandy Hook. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 28, 255–278. doi: 10.1177/0887403415577192

Keywords: gun attitudes, campus carry, concealed carry, campus safety, Texas

Citation: Butters AM, Kestilä-Kekkonen E and Ruoppila S (2024) A mirror of political ideology: undergraduates’ attitudinal drivers on implemented campus carry. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1261072. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1261072

Edited by:

Emmanuel Mordi, Delta State University, Abraka, NigeriaReviewed by:

Joseph De Angelis, University of Idaho, United StatesZlatko Hadzidedic, International Center for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relations, Bulgaria

Copyright © 2024 Butters, Kestilä-Kekkonen and Ruoppila. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sampo Ruoppila, sampo.ruoppila@utu.fi

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Albion M. Butters1†

Albion M. Butters1†  Sampo Ruoppila

Sampo Ruoppila