Wall-building policy: nationalist space management and borderphobia as right-wing populists' tools for doing authoritarian politics

- 1Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

- 2Department of Sociology and Social Policy, Wrocław University of Economics, Wrocław, Poland

The article analyses the situation that arose after the crisis on the Poland-Belarus border in the second half of 2021. The authors use the term “borderphobia” to describe social, political and propaganda mechanisms that became a form of border space management used to legitimize and gain support for the actions taken by the right-wing populist government in Poland. The phenomenon of borderphobia can be a symbol of the symbiosis between political authoritarianism, nationalism and economic neoliberalism: the combination of these three forces affects the development of the “border industry” in Europe and in the world. The policy based on borderphobia facilitates the suspension of civil rights in the border area: this is what happened in Poland, where a state of emergency was introduced in the border area under the pretext of “border protection.” The case of building the wall on the Polish-Belarusian border can also show how the nationalist right in Poland can use the borderphobic discourse for political mobilization and in an election campaign to maintain their influence and political power in the country. The article indicates that although the leaders of right-wing populist parties believe that the slogans of defending the “security border” and building border walls can bring them political benefits, the example of the Law and Justice (PiS) party in Poland has shown that this is not always the case.

1 Introduction: from social insecurity to “vicarious security” and border control

When social tensions related to social insecurity, a threat to jobs and rising energy bills undermine the position of the ruling elites, they must find a substitute source of unrest and promise the public that they will deal with it effectively. After the 2015 migration crisis, in the third decade of the twenty first century, the populist right is continuing to build prejudices against “aliens” and introduce another element to the political mainstream, which helps to perpetuate the authoritarian order and also legitimizes the right-wing nationalist vision of social order. They use the slogan of building walls and barbed wire fences to strengthen the borders of nation-states. After spreading Islamophobia and xenophobia, nationalists disseminate borderphobia (Burke, 2002) and encourage societies to allocate public funds to a new sector of the neoliberal economy, which is the rapidly growing industry of building walls, barbed wire fences and watchtowers at the borders. The atmosphere of borderphobia built after 11 September 2001 has now returned in another, improved version designed for the needs of right-wing populists:

A time, a world where states assert their own law, criminalize, deter and detain, and in so doing infringe international law and universal human rights. A world where capital flows across borders with rapidity and impunity but the flow of people is the subject of increasing anxiety and control (Burke, 2002).

The social phenomenon of borderphobia is manifested by the fear of open borders, the alleged threat posed to the country's territory by a wave of migrants and culturally, ethnically, racially and religiously different “strangers” who cross borders in an uncontrolled way. It is becoming another powerful tool used by the populist right to legitimize its political demands and also a convenient social mechanism used by the state to control its citizens. In this sense, the concept of borderphobia also appeared in the debate on migration policy in Australia, where the tension between defenders of national sovereignty and human rights resulted in a heightened political salience of “borderphobias” (Every and Augoustinos, 2008) In disputes between human rights defenders and the nationalist right, the latter used borderphobia to create an atmosphere in which “transgressions of national borders (both real and “imagined,” i.e., social, cultural, moral, racial) attract heightened fear and opprobrium, resulting in increasingly vicious, yet conversely socially acceptable, exclusionary actions” (Every and Augoustinos, 2008, p. 566). Such actions have always led to the marginalization of human rights and the domination of nationalist prejudices in public space.

In the literature, the term “phobia” is used instead of “borderphobia” in the context of fear of migrants and a manifestation of erroneous stereotypes, philistine phobias, and conspiracy theories (Goffe and Grishin, 2021). These sentiments were particularly evident during the first period of the COVID-19 pandemic, when rising fear and hate for migrants combined epidemics and xenophobia making it possible to focus on epidemics and phobia (Onoma, 2021). The concept of phobia usually appears in psychiatric analyses in the context of social anxiety disorder (Kuckertz et al., 2017). The condition of social phobia is marked by extreme fear and/or avoidance of situations that involve possible scrutiny by others (Stein et al., 2000). According to psychiatrists, phobias involve both fear and avoidance. For people who have specific phobias, avoidance can reduce the constancy and severity of distress and impairment. However, these phobias are important because of their early onset and strong persistence over time (Eaton et al., 2018). In our article, however, the concept of borderphobia refers not to individual reactions, but to the entire set of border policies occurring at the macro-social level and including many elements: panic caused by tabloid media, manipulations by populist politicians who thus distract public opinion from real social-economic problems, fear management in the context of “border threats,” the limitation of civil rights, the legitimization of the repressive actions of uniformed services, as well as attempts to legalize public expenditure on building walls and strengthening borders.

Although borderphobia stresses the securitisation of borders, it is also associated with nationalism and racism. Brubaker's statement about the relationship between populism and nationalism (Brubaker, 2020) fits the phenomenon of borderphobia and reflects its nature well. On the one hand, it makes it possible to direct reluctance and hatred toward “those outside” the borders and, on the other, it forces acceptance of limited civil rights and greater state control of “those at the bottom.” From Brubaker's perspective, the combination of nationalism and populism means simultaneous hostility toward “those outside” and “those at the top.” Borderphobia allows populist authorities to manage attitudes and control both “those outside” and “those at the bottom.” In this sense, borderphobia can combine the forces and activities of all agencies interested in “national security” (police, army, secret services, border guards, sensational and tabloid media, politicians – particularly right-wing nationalists) and, at the same time, use this to legitimize control and authoritarian measures in national politics. As Didier Bigo has written in the context of security and immigration control:

The professionals in charge of the management of risk and fear especially transfer the legitimacy they gain from struggles against terrorists, criminals, spies, and counterfeiters toward other targets, most notably transnational political activists, people crossing borders, or people born in the country but with foreign parents (Bigo, 2002, p. 63).

Borderphobia extends this list of “targets” against which the state's repressive apparatus can be used to include activists of social movements, non-governmental organizations, civil rights defenders, residents of border regions, media unfavorable to the government, politicians associated with the left, and so on. For this reason, borderphobia is a useful tool for managing fear and risk. At the same time, it is a concept that requires broad analysis from a social science perspective.

From the perspective of social practice, the political control related to borderphobia functions in the following dimensions of the public sphere:

– in the dimension of social psychology, borderphobia is used to evoke anxiety and a sense of threat, which may – as promised by the authorities – be reduced thanks to the actions of state security bodies and additional powers granted to uniformed services;

– in the dimension of discourse and social communication, borderphobia is an effective soft power tool (which involves controlling rhetoric and the dominant discourse, as well as exerting influence through the diffusion of norms) (Rothman, 2011), which shapes the dominant forms of communication, and a means of spreading social disinformation;

– in the domestic policy dimension, borderphobia is used to distract public attention from actual social problems and cover class and economic conflicts with the created threats to “national security.” It focuses the attention of the public and national political actors on ethnic issues and the issue of “border protection.” It also makes part of the society passively accept the restriction of civil rights caused by the “state of emergency” and the threat to “territorial integrity”;

– in the dimension of international politics, borderphobia is used as a tool for creating tensions and a means of promoting nationalist visions of geopolitics, emphasizing the importance of conflicts in shaping the world order in the twenty first century at the cost of international cooperation;

– in the dimension of the state economic policy, borderphobia legitimizes the transfer of public funds to the “security sector” and the development of the “border industry.”

Using the example of activities initiated and undertaken by right-wing nationalist populists in Poland, the article outlines the framework of contemporary borderphobia. It discusses the actual social and political functions of borderphobia using the example of the Law and Justice (PiS) government's policy in Poland. It also shows how borderphobia has become a useful tool of social control in the modern world and a means of facilitating the exercise of power in a state. This phenomenon is present in various parts of the world. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, however, it has been particularly visible in Europe and has become one of the main tools for building an atmosphere of “national danger,” which always politically boosts authoritarian and nationalist tendencies. It was not only right-wing populists in Poland who tried to divert attention from socio-economic challenges and stir up emotions over border protection. The external borders of the EU are less and less associated with bridges to new spaces, and more and more with high walls, barbed wire and police and border infrastructure packed with electronics. This scenography brings back the memories of the Cold War and solutions implemented in the era of the Berlin Wall. Referring to materials and reports published by non-governmental organizations which help immigrants, the results of surveys showing the attitudes to strengthening borders, as well as nationalists' statements appearing in the public space, the article defends the thesis that borderphobia in Poland has become an element of control over public opinion and a convenient means of justifying restrictions on civil rights and increasing the powers of state police and military institutions.

Mechanisms of borderphobia are particularly visible in countries where the populist right is in power. The example of Poland can illustrate how, despite the existing differences in political sympathies, the slogan of strengthening borders becomes a universal way of legitimizing the undemocratic and authoritarian power. It can also show how the borderphobic discourse can be used for political mobilization and in an election campaign. Since the beginning of the crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border in 2021, the government has been using this event as a useful propaganda tool to evoke a whole set of interconnected emotions and social attitudes: develop a sense of security threat, strengthen the nationalistic atmosphere and support for state power, distract public opinion from other challenges (especially economic ones) and legitimize additional powers for the state repressive apparatus (police, army, secret services). The culmination of this propaganda campaign was a few months before the parliamentary elections in Poland, which took place in the autumn of 2023. Then the PiS government decided to combine the parliamentary elections with a referendum that was to focus on two issues: accepting migrants from the Middle East and Africa to Poland and determining the future of the fence on the Polish-Belarusian border.

Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the PiS government has tried to differentiate Ukrainian refugees from those coming from Africa and the Middle East. At the time when Poland was accepting war refugees from Ukraine (the largest number of war refugees have stayed in the neighboring country: in the first 2 months of the war, nearly 3.5 million refugees from Ukraine crossed into Poland (Duszczyk and Kaczmarczyk, 2022) and the populist authorities in Poland tried to improve their image and gain an additional argument in tense relations with the European Union (EU), a wall was being built along Poland's frontier with Belarus. Just like Trump had the ambition to make the wall on the border with Mexico a monument of national security (Kolås and Oztig, 2022), the Polish government wanted the new wall to be a testimony of its determination and dedication to defend the country's order and security. While refugees from Ukraine were hitting the headlines, refugees from the Middle East and Africa were dying anonymously on the Polish-Belarusian border. The construction of the wall was to be an additional pretext to hide these events from public opinion. It was a typical display of racialisation of mobility and hierarchisation of life (Minca et al., 2022) – refugees from Ukraine with a similar culture and skin color were allowed to run away from bombs, but those who were bombed in Syria and had a different skin color did not receive such a chance at the border from the Polish state.

Section 2 shows the main differences between the traditions of a social and nationalist Europe. Section 3 examines the relationship between contemporary nationalism and neoliberalism, which is referred to as nationalist neoliberalism. It combines public subsidies with private companies linked to the ruling regime with the nationalist legitimacy of the policy pursued. Section 4 emphasizes that the method of space management favored by authoritarian governments and the right wing comes down to not only controlling anti-migrant discourse, but also to using migrants and refugees literally as political weapons. Section 5 shows, using the example of Poland, that the use of bordering as a political tool may lead to the suspension of all international and national laws by introducing a state of emergency in border zones or throughout a country. In the case of Poland, this means the legalization of push-back practices and the expulsion of journalists, social activists and doctors who want to help refugees outside the border area. Section 6 presents the results of a survey illustrating how borderphobia can be an effective tool for social control and political conflict management, used by the government. This section also discusses the results of the referendum, which was intended to strengthen the nationalist discourse about the border just before the autumn 2023 parliamentary elections. The conclusions outline the main consequences of disseminating borderphobia and possible areas for further research.

2 Social or nationalist Europe? The tradition of defending a territory vs. the tradition of civil rights

A wall is a symbol of the political, cultural and technological dimensions of a certain social order. As Vallet and David have written:

[T]hose walls consist of much more than a barrier built on masonry foundations. They are flanked by boundary roads, topped by barbed wire, laden with sensors, dotted with guard posts, infrared cameras and spotlights, and accompanied by an arsenal of laws and regulations (right of asylum, right of residence, visas) (Vallet and David, 2012, p. 112).

In the modern sense, a wall is not only an engineering structure full of technical gadgets in the hands of the repressive state apparatus, separating two different territories. A contemporary wall is something more – it needs to be understood “as a political divider that comprises complex technologies, control methods, legislative provisions and “securing the border” discourse” (Vallet and David, 2012, p. 112).

The very process of building walls and borders may be an element of a wider phenomenon: creating the identity and political legitimacy of state power. This is clearly seen in Israel, where separation is also linked to Israeli identity, an identity that functions as a basic cohesion of Israeli society (Falke, 2012). The slogan of defending borders plays a similar role in Eastern Europe. The project of building a wall on the Polish-Belarusian border strengthened the populist right-wing discourse in politics and was a continuation of the nationalist upheaval that arose primarily in the post-2015 period.

During the so-called 2015 migration crisis, governments of Eastern European countries rejected the idea of accepting quotas of refugees under the pretext of defending national sovereignty and security. The 2015 crisis revealed cultural and normative differences between the countries of the old EU and former post-communist Eastern European countries in their attitudes toward refugees and supranational solidarity (Kazharski, 2018). This was most pronounced in Poland and Hungary, where right-wing populists politicized the issue of migration. They evoked the fear of migrants who, as Kaczyński, the leader of the nationalist-populist Law and Justice (PiS) party, claimed, spread disease (Żuk and Żuk, 2018a). As a result, PiS in Poland and the Fidesz party led by Orbán in Hungary gained and consolidated their power in 2015. While in 2015 the slogans of reluctance to accept migrants were voiced primarily by the extreme Right and nationalists who wanted to expand their political influence, in 2021 the vision of a Europe surrounded by walls and barbed wire, closed to visitors from other parts of the world, gained the support of almost half of the governments of EU states. All this took place in a special atmosphere of a crisis of the nation-state's ability to ensure the social security of its citizens and, on the other hand, a crisis of identity and trust in the hitherto existing structures ensuring order. Due to the financial crisis, the post-pandemic crisis (Żuk and Żuk, 2022b), economic uncertainty and another wave of crisis caused by the war in Ukraine, guarding the borders which takes the form of nationalistic territorial atavism (Dillon and Lobo-Guerrero, 2008), have become an attempt to symbolically save the remnants of the stable nation-states' policy. Namely, the capacity of nation-states to combine economic growth with social cohesion has declined and domestic social compromises have been undermined (della Porta et al., 2021).

In a letter to the European Commission in October 2021, interior ministers from 12 EU countries (these were mainly countries from Eastern Europe: Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, plus Austria, Denmark, Cyprus and Greece) demanded that the construction of walls be financed from EU funds:

Physical barrier appears to be an effective border protection measure that serves the interest of whole EU, not just Member States of first arrival. This legitimate measure should be additionally and adequately funded from the EU budget as a matter of priority (Letter to the EC, 2021).

This initiative was not only a manifestation of cheap political and right-wing populism, but also a symbol of Europe abandoning its tradition of “solidarity of strangers” that asked to assist in the substitution of a fully inclusive, universal human community for a collection of territorially entrenched entities engaged in a zero-sum game of survival (Bauman, 2004, p. 142). The war in Ukraine, which broke out in February 2022, was additionally conducive to the growth of nationalist sentiments throughout Europe (Fekete, 2023). Consequently, right-wing nationalist populists grew stronger in various countries (Żuk, 2023) and the idea of building new walls and barbed-wire fences became even more popular. In 2023, the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, approved the financing of border walls with EU funds. With this decision, EU policy followed the standards of Trump's border policy (Rankin, 2023). In this sense, one should agree with the statements in the context of EU policy that, despite official assurances that civil rights are protected, state service violence, reminiscent of that from before the liberal times, is becoming a standard at the borders: “border violence is routinely displaced, concealed or denied where possible” (Isakjee et al., 2020, p. 1768). Depending on local conditions, border violence may be more or less overt:

In France on the north-western edge of the Schengen Area, the obscuring of violence takes on more subtle forms; those seeking asylum have restricted rights to even the basics of food, shelter and security through the pernicious violence of inaction. Yet border policy on the south-eastern edge of the Schengen Area features much more direct violence: systematic beatings of racialised migrants that seem more akin to the torture and corporal punishment of a pre-liberal age of governance (Isakjee et al., 2020, p. 1768).

The brutal reactions of states to asylum seekers and the ideological burden of the nationalist discourse about “defending the national order” and “border security” (Hodge and Hodge, 2021) resemble the nationalist mood of the late nineteenth and early twenteeth centuries. In this way, the nationalist tradition has entered mainstream European politics at the expense of social and democratic traditions. While the principle of the latter is disgust toward violence committed in the name of states and nations and openness to new ideas and newcomers from different parts of the world, the nationalist tradition is based (particularly from the nineteenth century) on a state controlling a specific territory and monitoring all actions of the population and resources in the area (Tilly, 1994). Nationalist exhortations block the construction of bridges to various social groups: instead, they call for high walls to be erected to give an apparent sense of security. For this reason, borders between nations were always – and particularly during modernity and the formation of nation states (Conversi, 2014) – associated with political violence and ethnic conflicts, which were usually caused by states and their populist policies (Conversi, 1999). Nationalism and populism cannot be separated: both are present in the populist discourse (Brubaker, 2020).

This phenomenon is booming in Eastern Europe, where right-wing populism has a strong influence and creates new walls more than 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall: Slovenia has fenced itself off from Croatia, Hungary has erected walls on its borders with Croatia and Serbia, and Bulgaria on the border with Turkey. In 2021, the government in Poland decided to build a wall of ~180 km on the Polish-Belarusian border. Since then, the slogan of the wall and border protection has become a permanent element of the ruling populists' political campaign in Poland. Even after the wall was built in 2022, it continued to be an element of the anti-immigrant discourse – the structure that was supposed to ensure the ultimate “border security,” using the language of those in power, was still used for political purposes. In June 2023, the nationalist government passed a referendum on the admission of migrants to Poland, which was scheduled for the same day as the parliamentary elections. It was supposed to be a response to the plans of the European Council, according to which EU countries that refuse to host refugees would be required to pay a sum of EUR 20,000 per person. In practice, however, the referendum was supposed to be a way to politically mobilize the nationalist electorate. As the PiS leader claimed, “The EU decision undermines Polish sovereignty and, at the same time, the sovereignty of other European countries” (Czuchnowski et al., 2023). The media and ideologues of the ruling nationalists warned, “If anyone thought that the EU institutions are only interested in Polish legislation, sovereignty in the field of migration and climate issues, they are wrong. EU institutions have a craving for Polish territory” (Janecki, 2023). In this atmosphere, migrants once again became a topic that was to decide the future of the populist government and allow the continuation of the “border hysteria.” Two of the four questions directly concerned migration, and one of them was about the future of the fences on the Polish-Belarusian border. Question 3 was: “Do you support the elimination of the barrier on the border between the Republic of Poland and the Republic of Belarus?” and Question 4 was: “Do you support accepting thousands of illegal immigrants from the Middle East and Africa under the forced relocation mechanism imposed by the European bureaucracy?” (Nationwide Referendum, 2023a).

Question 4 contained the essence of the nationalist-populist propaganda. Firstly, it made the false assumption that immigrants from the Middle East and Africa were “illegal.” Secondly, it lied and claimed that Poland had to implement a “forced relocation mechanism.” Thirdly, it contrasted Poland's security with mechanisms imposed by the “European bureaucracy.” This question included the main features of right-wing populists” narratives: nationalism, dislike for immigrants, hostility to the EU and manipulation of facts.

3 Nationalist neoliberalism: the fear of outsiders and the business of building walls for people in power

Some researchers have linked the return to the era of building walls and barriers with the failure of the neoliberal globalization project and the growing inequality between core and periphery countries in global economy (Rosière and Jones, 2012). While this thesis is generally correct, in the case of the semi-periphery, building walls does not so much separate the poor from the rich, but is rather a form of political legitimacy for populist rule and the physical expression and reinforcement of nationalist phobias. The nationalist shift in Eastern Europe resulted from the disillusionment of society, particularly of the people's classes, with the effects of the neoliberal transformation after 1989 (Żuk and Żuk, 2018b). On the other hand, the slogan of defending national sovereignty became an element of the nationalist agenda and was associated with the postulate of controlling “one's own territory.” As has been argued, the concept of sovereignty invoked:

… by populist right-wing nationalists in ways that reflect the notion of a state's right and ability to control affairs within its territorial domain (…). That invocation inevitably makes borders relevant – even central – to the right-wing populist agenda (Paasi et al., 2022, p. 4).

Under the conditions of neoliberal economic policy, borderphobia can be useful at the international level as well as at the level of national policy. In the first case, while the flow of goods, products and capital is to be unlimited, the flow of people is to be subject to special selections. It is not only about the division and mechanisms described by Zygmunt Bauman, which divide people into “tourists” (wealthy middle-class consumers) and “vagabonds” (refugees and economic migrants moving around the world in search of stability, security and prosperity). In this way, a system of “globalization for some, localization for some others” is created (Bauman, 1998, p. 46, 47). It is also about various complicated procedures that the state creates to boost its economy: determining limits and requirements needed by the economy, professional specializations particularly desired by the neoliberal state and scoring systems for assessing the suitability of a migrant for plans created jointly by business and state bureaucrats. At the domestic level, borderphobia in neoliberal economics has another function: it can be a lightning rod that safely discharges all social tensions and frustrations resulting from unequal economic policies. In this sense, borderphobia can create substitute topics and distract attention from everyday annoyances and point to those responsible for life failures. In other words, problems resulting from the system of social inequality are not solved by changing the socio-economic rules of the game, but are attributed to “foreign threats” and “scapegoats.”

The ideology of securitisation and border defense did not emerge in a vacuum. It can be said that in the case of Poland, it was a substitute for fulfilling the promise of social security. Although the PiS government emphasized in its post-2015 propaganda that it broke with neoliberal orthodoxy, in practice nothing of that sort happened. The so-called social programmes implemented by the PiS government only confirmed that “neoliberal programmes dismantle existing social arrangements to involve more people in market rationality” (Shields, 2021, p. 10). A model example of this policy was the “Family 500+” programme, which was one of the reasons why the PiS party won the 2015 elections and which, according to the propaganda of the right-wing populists, was supposed to prove that they implemented social policy. In practice, however, this programme did not challenge neoliberal logic but rather made its beneficiaries dependent on the mercy of the ruling authorities and did not solve the causes of social inequality (Shields, 2019). This programme did not strengthen public services and did not eliminate the causes of social problems. In line with market logic, it reduced women to the role of clients who were supposed to solve their problems using the small amount of money that the state provided under the “Family 500+” programme. It was rather a policy of weakening social ties, breaking up society and setting some groups against others. All minority groups fit the role of “external” enemies and a threat to the national order and tradition flowing from outside the state borders: LGBT communities (Żuk and Żuk, 2020), migrants identified by propaganda with “foreign threats” (Krzyżanowska and Krzyżanowski, 2018), and also hostile “ideologies” from the West, such as “gender.” While maintaining neoliberal logic and growing social inequalities, nationalist ideology was intended to cover class divisions and emphasize the importance of “national community” and “common national history and tradition.”

The imaginary “national identity,” defined according to the nationalist tradition, became more important in the process of organizing a political conflict than the real economic interests and class position of individual social groups. In the case of the losers of the neoliberal transformation, nationalism has turned out to be an ideology expressing class anger – this was the case among Hungarian workers (Scheiring, 2020) and most Polish workers, who voted for the nationalist PiS party (Ost, 2018). However, the emergence of anti-migrant sentiments and nationalist slogans has not undermined the neoliberal rules of the game in the economy – a new hybrid has emerged, which can be described as authoritarian neoliberalism (Stubbs and Lendvai-Bainton, 2020).

Under these conditions, the ideology of “securitisation” could flourish on an ideological level. However, this term did not refer to the “social security” of citizens, but to the “national security of the state.” The political aim was to increase the role and powers of the state repression apparatus; various types of uniformed services and secret police, which could be used at any time against their own citizens. At the cultural and ideological levels, on the other hand, the banner of “securitisation” was waved to increase the legitimacy of the power elite, which promised to solve the problem of social anxiety. However, it was not about social stability or the guarantee of good jobs, but about “physical security” against terrorists, bandits and illegal migrants (Bauman, 2016). It was also about some of the symbolic and ideological functions of the walls being erected. As Wendy Brown has rightly claimed, “contemporary border walls function as symbolic and semiotic responses to crises produced by eroded sovereign state capacities to secure territory, citizens and economies” (Jones et al., 2017). As far as the thesis that” all contemporary populist movements share the goal of reestablishing national sovereignty in a globalizing world” (Casaglia et al., 2020) goes, the slogan of defending sovereignty in the countries of Eastern Europe refers primarily to the former division into the East and the West from the Cold War period. Back then, official communist propaganda accused the West of being “capitalist, imperialist, and a threat to world peace.” Today, “the West is bad” in the opinion of Eastern European populists because it is liberal, cosmopolitan, threatening the traditional family and “traditional values,” demoralized, full of “homopropaganda,” anti-religious and attacks “national identity.” While the Cold War conflict could be described on an ideological level as a clash between “capitalism” and “socialism,” there is now a sustained ideological conflict between cultural liberalism and populist nationalism. However, this cultural tension translates into political conflicts, which can – as in the past – be described in geographical space and marked on the political map (“the West” and “the East” of Europe). The annual Independence March, taking place since 2010 and gathering the extreme and populist right in Warsaw, was a symbol of Eastern European opposition to Western modernization. The paradox was that the real opposition to the effects of economic neo-liberalization was expressed using the language of protest against cultural liberalization (Żuk and Żuk, 2022a).

The implementation of social engineering to address the slogan of “national security under threat” made it easier for the authorities in Eastern European countries to additionally pacify any potential social protests on the domestic scenes, and also reduced civic supervision over the policies implemented by the state authorities. This mechanism was particularly effective in countries such as Hungary and Poland, where politics was heading toward “clan state” (Sallai and Schnyder, 2018) and “mafia state” models (Magyar and Vásárhelyi, 2017).

In this way, in place of the autonomous civic sphere, in which a bottom-up, spontaneous and state-independent debate can take place, “necrocitizenship” is created – a zone of belonging “in relation to a wider context of militarization, exclusion, and willingness to die for the nation” (Díaz-Barriga and Dorsey, 2020, p. 51).

Events belonging to the cultural “soft power” contribute to the creation of the patriotic atmosphere. In the case of the Mexican-American border, this role was played by the “El Veterano” Conjunto Festival (Dorsey and Díaz-Barriga, 2011). In Poland, in order to strengthen the morale of the uniformed services guarding the Polish-Belarusian border, a propaganda concert entitled “In Support of the Polish Uniformed Services” (Szubrycht, 2021) was organized at the Polish Army air base in Mińsk Mazowiecki in December 2021. The concert was broadcast by public television, fully subordinated to the authorities and acting as a propaganda mouthpiece of the nationalist government (Żuk, 2020). It was to strengthen the solidarity of society with the army, border guards and the police catching illegal migrants.

The project of building a wall on the border of Poland with Belarus can be a symbol of the logic of nationalist neoliberalism: use the wall policy for political propaganda and social manipulation and at the same time turn it into a business that will allow public funds to be transferred from the state budget to companies and circles associated with the ruling party. In the case of Poland, the construction of the wall, which was planned to be 180 km long and over 5 m high, is to cost ~PLN 1.6 billion (~USD 400 million). The Ombudsman, one of the last institutions that in 2021 was still beyond the control of the authorities in Poland, pointed out that this investment would not be subject to laws protecting such issues as the right to safe working conditions, protection of life and health, environmental protection and the right to information about it (Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich, 2021). In accordance with the provisions of the Act on the construction of state border protection published in November 2021, the following will not be required: a building permit; a decision to determine the location of a public purpose investment; preparation of a construction project; and obtaining other decisions, permits, opinions and arrangements (Act on the Construction, 2021). In practice, this means that the principles of environmental protection and the conditions for using its resources do not have to be observed during the construction of the wall. This also means that throughout the construction process, information on the environment and its protection as well as environmental impact assessments will not be made available. It is also not necessary to ensure safety and health protection conditions for people on the construction site.

The entire investment and construction of the wall was to be supervised by the Central Anticorruption Bureau (CBA), an institution that in practice is a political police controlled by PiS, protecting the interests of the ruling party and digging up dirt on people associated with the opposition. To eliminate any social control over the construction of the wall, the act also includes a provision to forbid staying within the area up to 200 m from the border.

It has already been shown that global capital benefits from current political responses to transnational migration which are characterized by outsourcing and privatization of border control (Uhde, 2021). Political and business practices, which were implemented during migrations from Africa, are now also carried out in Eastern Europe. The process of militarisation and securitisation of migration management can bring large gains to those in power in authoritarian countries such as Poland or Hungary. Akkerman's (2019) report shows that the global market for border security (has been) estimated to be worth ~ e17.5 billion in 2018. Since then, in an atmosphere of nationalism, the “border security” production market could only grow, increasing the profits of companies specializing in servicing the construction of walls. In this way, neoliberal capitalism fuelled by nationalism has created a new global business sector.

It should be added that the mixture of authoritarianism, nationalism and neoliberalism has become a permanent element of the contemporary version of capitalism in various parts of the world [Philippines (Ramos, 2021), Brazil (de Souza, 2020), Turkey (Tansel, 2018; Akçay, 2021), Hungary (Fabry, 2019), countries of the Visegrád Group in Eastern Europe (Scheiring, 2021)] in the 2020s. This ensures “neoliberal development” (Arsel et al., 2021) thanks to the political tools used by authoritarian states, on the one hand, and to the ideological superstructure in the form of nationalism and xenophobia, on the other.

4 Weaponization of migrants and militarisation of bordering: political weapons in the hands of the state

Segregation policy and protection of “ethnic purity” are the right-wing populists' methods of managing public space and discourse. Regardless of whether the situation related to the United States under Trump (who wanted to build a wall on the border with Mexico) (Demata, 2017), Israel (where the nationalist Right want to separate themselves with walls and fences from the Palestinians) (Pallister-Wilkins, 2011) or Eastern Europe under Kaczyński and Orbán (who have used the “migrant threat” from the beginning of their reign), controlling territories and building walls are permanent elements of the populist power.

The defense of territorial (Casaglia et al., 2020), political, economic and cultural sovereignty is the basis for specific actions and campaigns by right-wing populists. In Poland, this translated into the creation of “LGBT-free zones,” free from western influence, by local PiS authorities in 2019 and 2020. These zones, created at local and regional levels, were meant to be areas defending the traditional family against the “flood of homopropaganda” from the West (Żuk et al., 2021). In turn, in 2018, the defense of “historical truth” was supposed to ensure full “national sovereignty” over the presentation of history and the elimination of concepts such as “Polish concentration camps” from the public space. During this campaign, PiS circles called for only Polish guides at the former concentration camps in order to limit the influence of “foreign narratives” in these places (Żuk, 2021).

These campaigns, like anti-refugee and anti-migrant rhetoric (Krzyżanowski, 2018), were instrumentally exploited and politicized in Poland after the nationalist-populist PiS party took over power in 2015. However, prior to that, state policy had not directly contributed to the death of refugees in Poland. This changed in 2021. From August 2021 to the first half of 2023, 49 bodies of migrants were found on the Belarusian-Polish border. It can be assumed, however, that the real numbers of borderphobia victims in Poland are much higher (Chołodowski, 2023). Between August 2021 and January 2023, activists helping migrants on the Polish-Belarusian border received 226 reports of 317 missing persons. We managed to find 92 of them, of which 12 were fatalities (Grupa Granica, 2023, 6). At the same time, even though the wall has already been built on the border, the so-called deportations continue to take place: border guards illegally transport migrants to the forest and push them back to the Belarusian side. In December 2022 and January 2023 alone, 298 people declared that they had experienced a total of 544 deportations. Many people are subject to multiple deportations (up to several dozen times). As activists from the Border Group (Grupa Granica) report:

Migrants also reported that they had experienced violence during deportations. They said that the Polish services had beaten and threatened them, sprayed pepper spray on their faces, taken their clothes and food, as well as destroyed and stolen their smartphones. Destroying shoes and clothing is a particularly sophisticated form of cruelty and humiliation, especially during winter months (Grupa Granica, 2023, 10).

Migrants on the Polish-Belarusian border have been reduced to the role of “political weapons.” On the one hand, the Lukashenko regime in Belarus treated refugees as blackmail and a weapon against the EU and pushed them to the Polish side. This action involved the Belarusian police and services, which organized the air transport of migrants from the Middle East (primarily from Iraq, Kurdistan and Syria) to Minsk, and then transported them to the Polish-Belarusian border. There, the Belarusian services pushed migrants toward Poland. In the border zone, the Polish uniformed services did the same – they pushed migrants back to the Belarusian side, using the slogan of “defense against the flood of migrants.” As Marianna Wartecka from Rescue Foundation (Fundacja Ocalenie) says, “people die from cold, hunger and thirst, and the Polish services – border guards and the army – at night, in the dark and in the cold, take people to the forest, to the swamp and to the barbed wire fence that has been hastily erected” (Wartecka, 2021).

The conflict on the Polish-Belarusian border could be perceived as Lukashenko's action – approved and supported by Putin – played on the geopolitical level against the EU (by dividing EU countries over the issue of migration and showing the inhumane face of the union). However, it had a direct national political influence. In Belarus, it was supposed to strengthen Lukashenko's power. In Poland, it perpetuated the nationalist mood strengthening the rule of PiS populists. Both of these national goals in fact strengthened Putin's position in the region: they accelerated Belarus's dependence on Russia and consolidated the position of the PiS government in Poland as a force weakening the EU from the inside.

5 “Where are the children from Michałów?” A state of emergency, policing of space in Poland and the social engineering of the bordering policy

The climax that aroused the empathy of at least part of the public was the action of the border guards who transported over 20 migrants staying in Michałów to the Polish-Belarusian border on 28 September 2021, although the day before the migrants had begged not to send them back. There were eight children in the group who hugged each other and cried. These children were transported to an unknown place in the forest and became a symbol of the cruelty of the Polish state services. After this incident, social protests and criticism of the authorities' actions against migrants intensified.

To curb social empathy and solidarity with refugees, a spectacle of right-wing and racist propaganda was unleashed. At a press conference on 27 September 2021, Mariusz Błaszczak, the minister of national defense and Mariusz Kamiński, the head of Secret Services, showed materials that were said to have been found on the phones of some refugees who had crossed the border with Belarus. The government propaganda was supposed to dehumanize migrants and create an atmosphere of hostility toward them. The refugees were accused by the PiS government ministers of zoophilia, terrorism and pedophilia. At the conference, they showed, among other things, a video of sexual intercourse between a man and an animal, allegedly found on a refugee's phone. Later it turned out that it was a frame from an old pornographic film that was circulating on the internet.

To prevent the media and social activists from seeing the deaths of refugees and the practices applied by uniformed services on them, the PiS government decided to take radical measures. Andrzej Duda, the president of Poland, who supports the PiS party, and prime minister Morawiecki introduced a state of emergency in the border zone in September 2021, which included eight districts in two provinces in eastern Poland (Figure 1) (President of the Republic of Poland, 2021). These provisions made it possible to check how a state of emergency works in practice and introduce a number of restrictions on civil rights, such as “suspension of the right to organize and conduct assemblies in the area covered by the state of emergency” or “limitation of access to public information regarding activities carried out in the area covered by the state of emergency in connection with protecting the state border and preventing and counteracting illegal migration” (President of the Republic of Poland, 2021). It was the first time a state of emergency was introduced in Poland since the fall of the Eastern bloc after 1989. Among the primary goals that the populist nationalists in power wanted to achieve were: to introduce an information blockade, to not allow journalists to enter the border zone and manipulate public opinion; to suspend the application of international laws in the area covered by the state of emergency; and to legalize the use of violence and force against anyone who could be arbitrarily considered a threat to “national security.” In addition, the state of emergency prevented social activists and doctors from reaching migrants who needed help. In this way, full power was given over to the police, military and Secret Services in the territory of the state of emergency.

Figure 1. Map of Poland with eight districts in Podlasie and Lublin provinces, where a state of emergency was introduced. Source: President of the Republic of Poland (2021).

Blocking doctors' access to people wandering in the woods and dying of exhaustion met all definitions of crimes against humanity. Doctors from the “Medics on the Border” group operating just beyond the belt covered by the state of emergency usually diagnosed refugees with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting (often lasting for several days, caused by drinking contaminated water from nearby reservoirs), as well as weakness, dehydration, cold, infections and the accompanying low-grade fever and foot injuries (abrasions, inflammatory-purulent changes) (Medycy na Granicy, 2021).

As the media did not have access to suffering migrants, the victims became anonymous and faceless. Unnamed children whose photographs did not reach the media died in silence. They could not arouse remorse. The Polish authorities put the suspension of all civil rights in the border zone down to geopolitical challenges and the need to defend the borders. This nationalist rhetoric did not withstand the clash with the reality in which refugees were dying. As one of the activists of the Border Group [Grupa Granica] supporting refugees on the border has written:

A cold man in a forest is not geopolitics. Neither the one who drank a few days ago, nor the one in wet shoes, nor the one with a child in his arms. A clear-eyed 21-year-old student and her boyfriend sleeping on the ground another night are not geopolitics. No child is geopolitics (Dabrowska, 2021).

In order not to expose the uniformed services to the allegation of violating national and international law, in October 2021, the PiS authorities legalized the push-back practices – taking people to the border without the possibility of applying for international protection, although these practices were contrary to national law, the Geneva Convention and the Constitution of Poland. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) (prepared thanks to contributions made by Liam Thornton, PhD) says the following about the so-called “push-back act” legalizing pushing people back to Belarus:

Provisions will unjustifiably restrict the right to an effective remedy for persons seeking international protection and asylum in Poland en route or on the territory of Poland by limiting the possibility of claims for international protection to be made and not providing effective right of redress and appeal (Thornton, 2021, p. 2).

The actions of the Polish government confirmed previous analyses pointing to the intensification of re-bordering and Euroscepticism of post-communist countries (Krasteva, 2020), a special type of “opportunistic sub-regionalism” of the Visegrád Four (V4) (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia) (Bedea and Osei Kwadwo, 2021) and the politics of “radical conservative nation-building,” which uses the “securitisation of borders” policy (Scott, 2020). In addition, however, it should be recognized that the bordering policy is part of a broader concept within the foreign policy adopted by the populist Right in Poland, which is part of the agenda of European nationalists and an alternative, right-wing vision of the social order (Varga and Buzogány, 2021).

6 Space management and borderphobia as a means of legitimizing political authoritarianism and managing a political conflict

Just as the 2017 “Rosary to the Borders” campaign was intended to mobilize Catholic nationalists against Muslim migrants (Kotwas and Kubik, 2019), the campaign involving a state of emergency on the border and the slogan of building a wall (the construction of which will be used to revive nationalist propaganda) became a campaign against refugees, civic organizations which defended them (referred to as “traitors of Polish interests repeating foreign propaganda”) and support for the PiS government “which cares for national security.” A spectacle of this type, organized by the PiS populists, on the one hand, legitimized the politics of the government on the ideological level and, on the other, revived the far-right and fundamentalist base for the PiS rule.

After the government declared a state of emergency and the decision to build a wall, the extreme Right in eastern Poland revived. A call to create “National Patrols” appeared on the “Narodowy Białystok” (National Białystok) group's website in October 2021:

We will no longer be passively watching the next wave of migrants flooding our homeland due to defective law and liberal left-wing activists. Our ancestors sanctified our land and border with their own blood and the blood of the enemies, and today, we, Poles, nationalists, feel obligated to protect them. Called for help by the society of Podlasie, together with the National Białystok – Autonomic Nationalists (AN), we form National Patrols in the border areas not covered by the state of emergency (Narodowy Białystok, 2021).

The state of emergency introduced in the border zone was also a form of training exercise for all services of the state repression apparatus. These skills in the police force can be a means of managing a state of emergency throughout Poland in a situation where right-wing populists encounter strong public resistance. Thus, similar repressions as those used in other countries were implemented against people trying to help and provide support to save the lives of those trapped in desperate conditions at the border (Dijstelbloem and Walters, 2021). An information blockade, repressions against journalists and social activists, and giving full power to the police and Secret Services may be a way to extend PiS's power in a situation where public support will decline.

The third goal of the nationalist spectacle, the victims of which are refugees, is to build political support for PiS. According to commentators, the more brutally the PiS government deals with people on the Belarusian border, the more it consolidates its rule in the public space. The state of emergency, throwing children into the forest and a wall on the border – all of this is supposed to strengthen the belief that the PiS government is the one that most effectively cares for the interests of Poles without playing with sentiments and scruples (Siedlecka, 2021). Moreover, these brutal actions by the government were portrayed as a defense of the external, “eastern borders of the EU.” The PiS government assumed the role – as was the case in Italy (Vergnano, 2021) – of migration “gatekeepers” and thus won the favor of the European Commission.

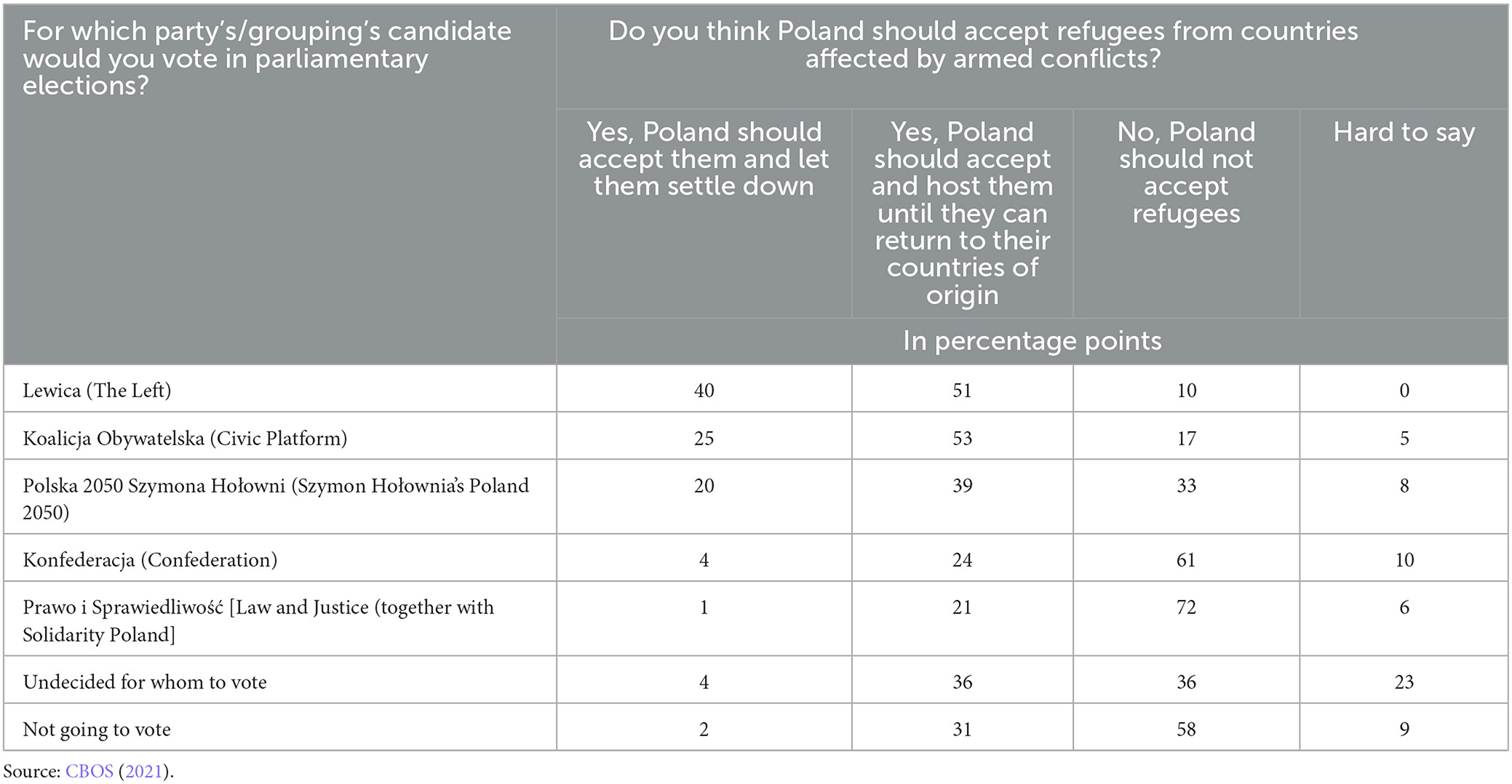

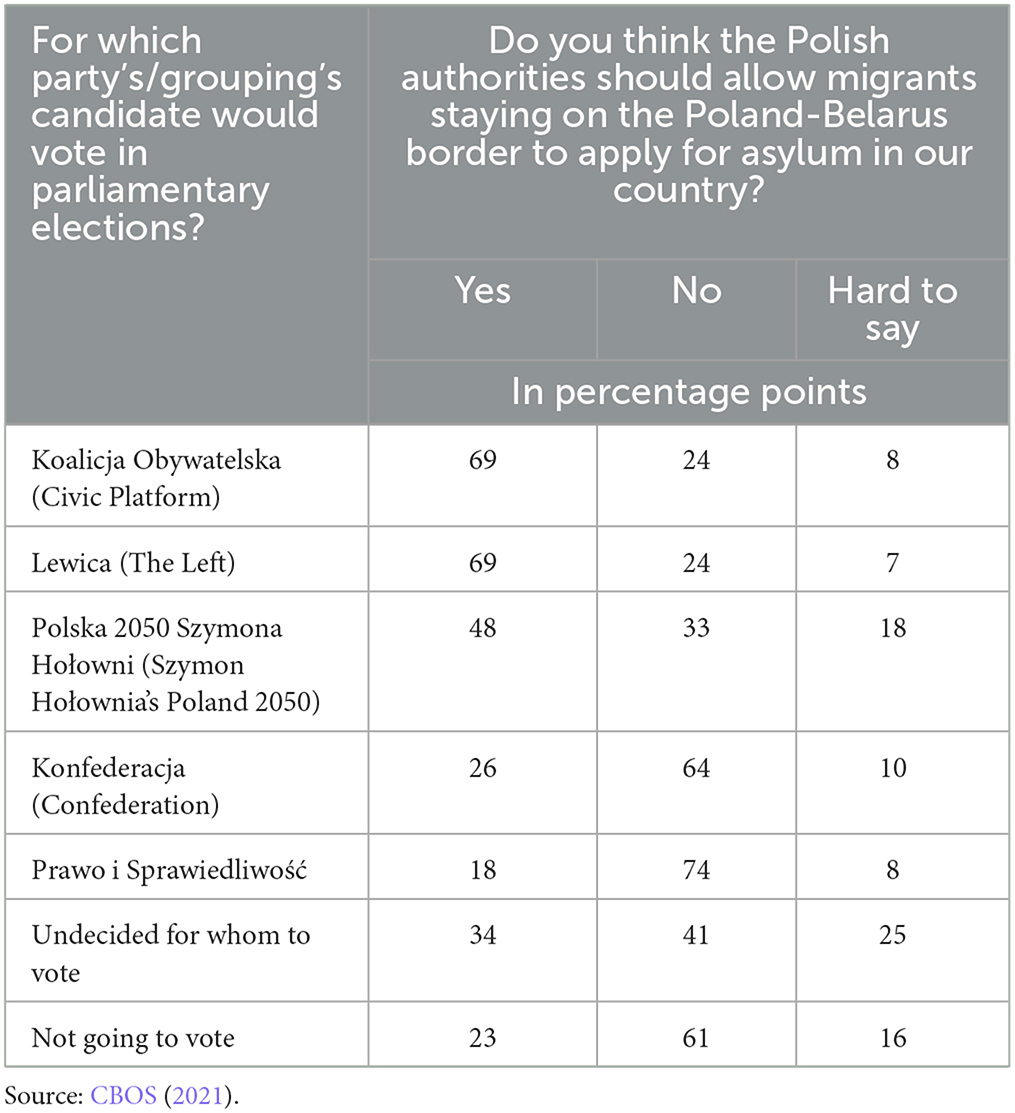

However, polls showed that PiS's border policy was primarily intended to consolidate and cement its own electorate and to treat the refugee issue as a way to manage a political conflict. In the poll carried out in September 2021, it was clearly visible that the refugee issue effectively divided society due to political sympathies (CBOS, 2021). The most chauvinistic positions were represented by the supporters of PiS and United Poland, the PiS coalition partner (72% of their supporters were against accepting refugees) and the supporters of the far-right Confederation (61% were against accepting refugees even though they were more liberal than PiS's supporters). The supporters of the Left and the liberal opposition were the most open-minded (Table 1). The distribution of votes was similar regarding the opinion on the possibility of migrants applying for asylum in Poland. According to nearly 70% of supporters of the Left and the liberal opposition, the authorities should allow migrants staying on the Polish-Belarusian border to apply for asylum. Supporters of the far-right Confederation (64%) and PiS (74%) expressed a different opinion (Table 2).

Table 2. Opinions of Poles about allowing migrants to apply for asylum in Poland by political sympathies.

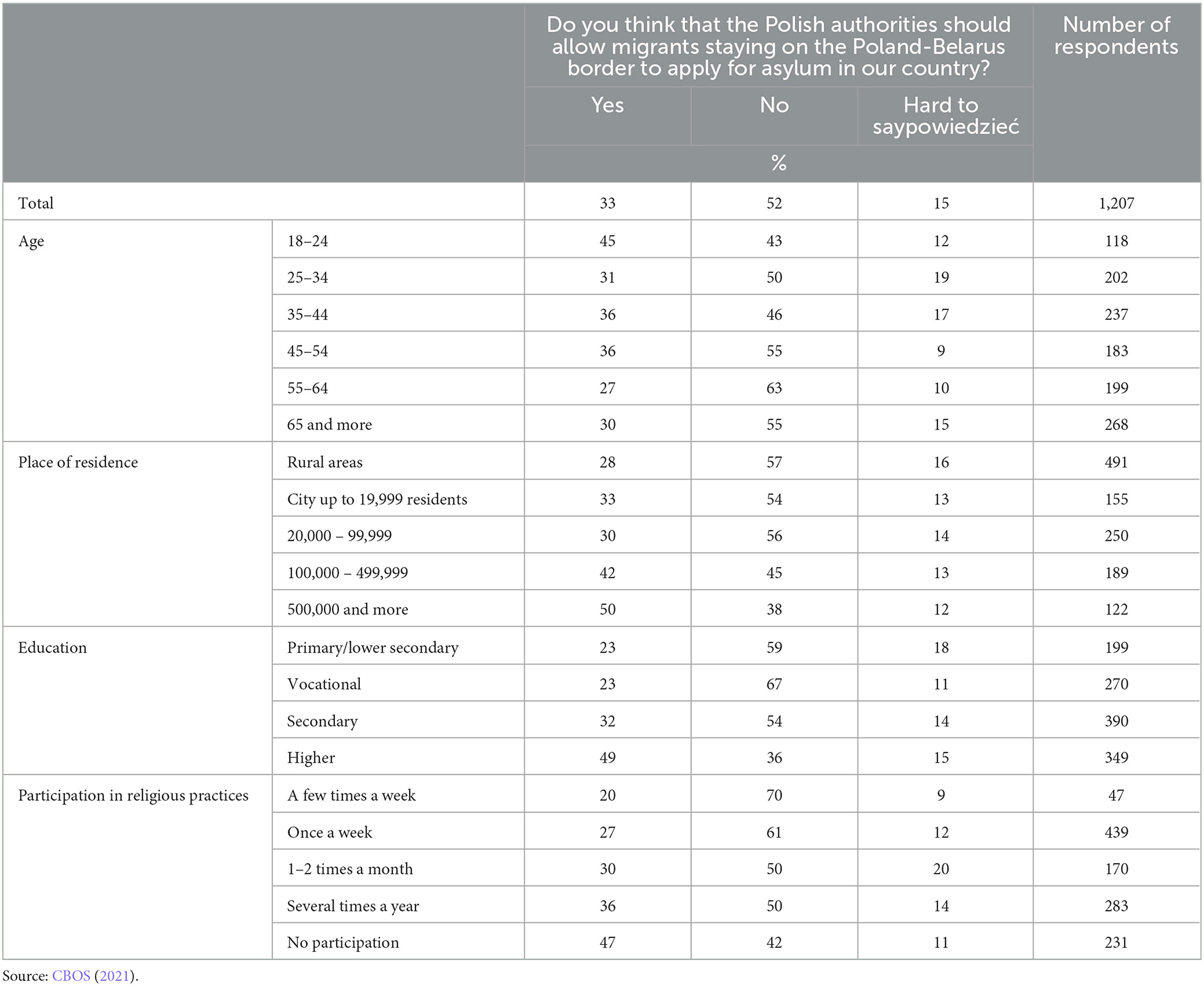

These political differences, however, did not affect the general trend created by the authorities: more than half of the entire population of Poland (52%) denied migrants staying on the Polish-Belarusian border the right to asylum and only one-third of the population recognized this right. The socio-demographic factors influencing the attitude toward migrants were interesting. The most liberal and open-minded attitudes toward migrants were expressed by residents of large cities (50%), people with higher education (49%), the youngest respondents aged 18–24 (45%) and people who did not participate in any religious practices (47 %). The greater the religiosity, the more repressive and nationalist the stance against migrants (Table 3). These data illustrate the political alliance between the conservative Catholic Church in Poland and the right-wing nationalist PiS government, and confirm that the religious factor in Poland is a transmission belt for strengthening the political influence of PiS (Żuk and Żuk, 2019).

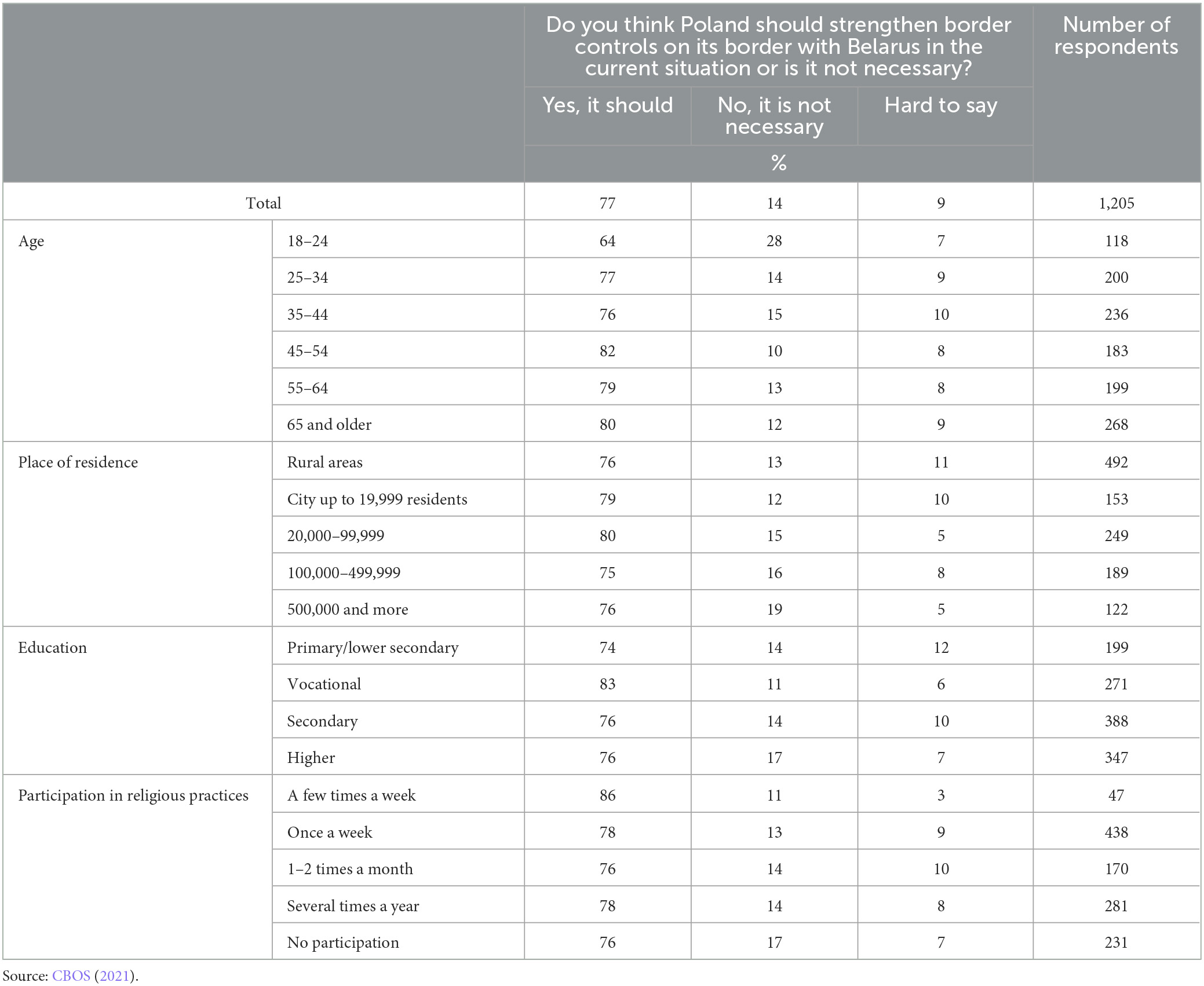

Regardless of the distribution of attitudes toward migrants in individual societies, the populist PiS government was able to in still another phobia: “borderphobia” and fear of invaders who threaten borders and national security. According to 74% of Polish society, “Poland should strengthen control on the border with Belarus” and only 14% had a different opinion than the ruling regime (Table 4).

Borderphobia, of course, does not only concern Poland because, along with the populist trend of building walls in Europe and around the world, it is becoming another tool for manipulating public opinion and creating political support by authoritarian forces. From this perspective, open borders not only pose a threat to culture, economy and national tradition, but also endanger the physical security and existence of the nation. As a consequence, the authoritarian state and increasing expenses on the military, police and building walls are meant to reduce tension and stress related to borderphobia. The same forces that create a sense of threat can respond to fear and social tensions. Under the right conditions and with the dominance of right-wing populist discourse in public spaces, such phobias can persist and consolidate their presence for a long time.

This was also the case with the attitude toward migrants in Poland. Before PiS won power in the autumn of 2015 and imposed a nationalist discourse, Polish society was generally open to migrants. In May 2015, only 21% of Poles were against accepting refugees. During the right-wing populists' successful election campaign in October 2015, when the slogan of fear of the “flood of Islamic refugees” was exposed by PiS, opposition to refugees rose to 40%−43%. Over the following years of PiS's nationalist propaganda from the winter of 2015 to the autumn of 2021, opposition amounted to 53–60%. The recent events on the border with Belarus and the cruelty toward refugees that broke through to the media reduced the percentage of opponents to admitting migrants to 48% (CBOS, 2021).

However, the election campaign based on dislike for refugees and borderphobia made the PiS party lose power. Tired of 8 years of nationalist propaganda, Polish society rejected the threat of migrants and slogans about strengthening barriers at the borders. The results of the referendum in Poland have shown that even the authoritarian authorities that fully control the state media cannot control all social behavior and political processes. Combining the anti-migration referendum with the parliamentary elections ultimately, against the will of the PiS government, did not ensure its political victory, but became one of the pretexts for building social resistance. All opposition groups called for a boycott of the referendum and for refusing to collect referendum ballots during voting. The refusal to accept the referendum ballot was an act of public opposition to right-wing populism, racism and borderphobia. Instead of mobilizing supporters of the nationalist government, the referendum united the opponents of right-wing populism. While the turnout in the parliamentary elections was the highest since the 1989 systemic transformation in Poland (nearly 75% took part in it), only 40.91% of eligible voters cast their referendum ballots. For this reason, the referendum results were invalid (more than 50% is required for a referendum to be valid) (Nationwide Referendum, 2023c). It is worth noting, however, that the vast majority of referendum participants supported nationalist demands. Namely, 96.04% of voters answered “no” to the question “Do you support the elimination of the barrier on the border between the Republic of Poland and the Republic of Belarus?” Similarly, 96.79% gave a negative answer to the question “Do you support accepting thousands of illegal immigrants from the Middle East and Africa under the forced relocation mechanism imposed by European bureaucracy?” (Nationwide Referendum, 2023b).

Another voice in the campaign calling for the negation of the nationalist policy of the PiS government just before the 2023 elections was the premiere of the film entitled “The Green Border” directed by Agnieszka Holland. As the director of the film said, “I am making a film that is a scream.” In the context of the film, she referred to the referendum organized by PiS: “No one asks in the referendum whether you agree to pushbacks, shooting migrants, sinking their boats and refusing help at sea. The authorities try hard to protect our consciences, helping us protect ourselves behind the veil of ignorance. They give us a dose of horror by showing us fires near Paris and saying: ‘Don't interfere, we'll sort it out”' (Żakowski, 2023).

The film inspired by the events on the Polish-Belarusian border was met with an aggressive attack by representatives of the PiS government and the uniformed services. In their statement, the trade union organization of border guard officers have announced as follows:

The film “The Green Border” is a propaganda product, carefully tuned to the ideological tone presented by circles hostile to the Polish raison d'état. This film presents the Polish state as an inhumane dictatorship, and Polish Soldiers and Officers as soulless chain dogs of an oppressive regime. This is a despicable action … We have one thing to say to the initiators and producers of the film “The Green Border': ONLY PIGS SIT IN CINEMAS” (Do Rzeczy, 2023).

This slogan was repeated by Andrzej Duda, the president of Poland directly associated with the PiS party. The film, which premiered on 22 September, was watched in cinemas in Poland by nearly 700,000 people until the referendum on 15 October 2023 (Stowarzyszenie Filmowców Polskich, 2023). It was certainly an important cultural contribution to the debate on stopping nationalist borderphobia.

7 Conclusions

The concepts of borderphobia outlined in this article as ways of legitimizing political power, politicizing borders and the elements of the “border industry” that builds walls and barbed wire fences with public funds are not only present in Poland. This is an increasingly common measure of political social control being introduced by the populist right into mainstream politics in various parts of the world. The fear of “external threats” is used primarily as a means of pursuing authoritarian politics at a national level. It makes it possible to tighten the law, introduce a state of emergency in selected areas, suspend the application of international laws and conventions protecting civil rights, justify increasing expenditure on the army and the police, and transfer public funds to private companies serving the “border industry.” It can be said that current trends in European politics emphasizing the importance of border security are intended to ensure political success for those who are in the vanguard of the narrative promoting borderphobia. On the other hand, they are a return to classic nationalist ideas from the nineteenth century, which aimed to manage space and control a specific territory. In the case of Poland, the borderphobia caused by conflict on the Polish-Belarusian border was intended to perpetuate the political hegemony of right-wing populists. For this reason, the PiS government had no interest in solving the humanitarian and political problem of migrants on the border. Quite the contrary, it had an interest in prolonging this tension and building the main political conflict around it, creating a military atmosphere of an “endangered homeland,” which required the social support of the government. However, this political strategy proved to be completely ineffective in the case of elections in Poland. Although the PiS government used various tricks to maintain power and, as opposition activists expected, the election campaign was unfair (Żuk and Pacześniak, 2022), the propaganda based on borderphobia and hatred toward refugees turned out to be ineffective. As the article shows, the referendum (the main goal of which was to mobilize government supporters by using the mechanisms of borderphobia) was invalid as it was boycotted by the majority of society. The case of Poland has also confirmed the analyses of other researchers that the construction of walls and additional fences on the border has no impact on refugee flows. These walls can only serve as political tools for populist leaders, but their deterrent effect on subsequent waves of migrants is highly questionable (Avdan et al., 2023). Moreover, the example of PiS leaders has confirmed the results of the analyses that national party leaders at risk of losing office are usually incentivised to implement popular policies, such as border wall construction, hoping that doing so will prompt a domestic rally effect (Linebarger and Braithwaite, 2022). Fortunately, this mechanism is not always effective, as shown by the history of Poland ruled by the PiS party. In this case, a cynical political game that used the issue of the border wall and the fear of refugees mobilized society against the government and the propaganda of right-wing populists.

Further analyses of borderphobia and the “border industry” should include both comparative and political analyses of how much this type of practice is accepted by individual societies. Similar to border studies, the analysis of borderphobia should not be limited to geography, but include a number of interdisciplinary studies in the field of social sciences (political sociology, economics, discourse analysis, social psychology and cultural analyses) (Johnson et al., 2011).

They should also deal with economic and cultural conditions of these phenomena, of the discourse legitimizing borderphobia and also all forms of social protest and civic initiatives opposing the development of the “border industry.” In the longer term, it is important to assess the social, economic (including impact on local labor markets) (Pradella and Cillo, 2021) environmental and political effects of the wall-building policy. All analyses of trafficking in human beings related to the policy of restrictions and securitisation in border areas (Bhagat, 2022), as well as critical analyses of bureaucratisation and technologisation of crossing borders (Burrell and Schweyher, 2021) and the impact of these processes on the atmosphere of borderphobia are also important. It is also crucial to examine the impact of building a “corral apparatus” border infrastructure on the health and mortality of migrants (Boyce and Chambers, 2021). The victims of this nationalist phobia will be migrants, societies on whom bordephobia is imposed, local communities living in border areas, as well as animals whose natural migration routes are blocked.

Author contributions

PiŻ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—original draft. PaŻ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Act on the Construction (2021). Ustawa z dnia 29 Pazdziernika 2021 r. o Budowie Zabezpieczenia Granicy Państwowej. Dziennik Ustaw, no. 1992. Available online at: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20210001992/O/D20211992.pdf (accessed August 12, 2023).

Akçay, Ü. (2021). Authoritarian consolidation dynamics in Turkey. Contemp. Politics 27, 79–104. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2020.1845920

Arsel, M., Adaman, F., and Saad-Filho, A. (2021). Authoritarian developmentalism: The latest stage of neoliberalism? Geoforum 124, 261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.003

Avdan, N., Rosenberg, A. S., and Gelpi, C. F. (2023). Where there's a will, there's a way: border walls and refugees. J. Peace Res. 12, 918. doi: 10.1177/00223433231200918

Bauman, Z. (1998). On glocalization: or globalization for some, localization for some others. Thesis Eleven 54, 37–49. doi: 10.1177/0725513698054000004

Bedea, C. M., and Osei Kwadwo, V. (2021). Opportunistic sub-regionalism: the dialectics of EU–Central-Eastern European relations. J. Eur. Integr. 43, 385–402. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2020.1776271

Bigo, D. (2002). Security and immigration: toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives 27, 63–92. doi: 10.1177/03043754020270S105

Boyce, G. A., and Chambers, S. N. (2021). The corral apparatus: counterinsurgency and the architecture of death and deterrence along the Mexico/United States border. Geoforum 120, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.007

Brubaker, R. (2020). Populism and nationalism. Nations Nationalism. 26, 44–66. doi: 10.1111/nana.12522

Burke, A. (2002). Borderphobias: The Politics of Insecurity Post-9/11. Borderlands 1 (1). Available online at: https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20021021002449/http://www.borderlandsejournal.adelaide.edu.au/vol1no1_2002/burke_phobias.html (accessed August 12, 2023).

Burrell, K., and Schweyher, M. (2021). Borders and bureaucracies of EU mobile citizenship: Polish migrants and the personal identification number in Sweden. Polit. Geogr. 87, 102394. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102394

Casaglia, A., Coletti, R., Lizotte, C., Agnew, J., Mamadouh, V., Minca, C., et al. (2020). Interventions on European nationalist populism and bordering in time of emergencies. Polit. Geogr. 82, 102238. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102238

CBOS (2021). Opinia Publiczna Wobec Uchodzców i Sytuacji Migrantów na Granicy z Białorusia. Komunikat z badań.

Chołodowski, M. (2023). Kryzys na Granicy Polsko-Białoruskiej. Kolejne ofiary. Dwa Ciała Wyłowiono z rzeki Narewka. Wyborcza.pl, June 21. Available online at: https://bialystok.wyborcza.pl/bialystok/7,35241,29891580,kryzys-na-granicy-polsko-bialoruskiej-kolejne-ofiary-dwa.html (accessed August 12, 2023).

Conversi, D. (1999). Nationalism, boundaries, and violence. Millennium 28, 553–584. doi: 10.1177/03058298990280030901

Conversi, D. (2014). “Modernity, globalization and nationalism: The age of frenzied boundary-building,” in Nationalism, Ethnicity and Boundaries: Conceptualising and Understanding Identity through Boundary Approaches, ed. J. Jackson and L. Molokotos-Liederman (Abingdon: Routledge), 57–82.

Czuchnowski, W., Kondzińska, A., and Wroński, P. (2023). Referendum w Sprawie Imigrantów ma Pomóc PiS Wygrać Wybory. Ujawniamy Kulisy. wyborcza.pl. Available online at: https://wyborcza.pl/7,75398,29872813,referendum-w-sprawie-imigrantow-ma-pomoc-pis-wygrac-wybory.html#S.TD-K.C-B.2-L.1.duzy (accessed August 12, 2023).

Dabrowska, A. (2021). Człowiek z Dzieckiem na Reku nie jest Geopolityka. In: Klauziński, S. ‘Dwie i pół Godziny Drogi Stad Umieraja Ludzie.' Tysiace w Marszu Solidarności z Uchodzcami. Mazowieckie: OKO.press.

de Souza, M. L. (2020). The land of the past? Neo-populism, neo-fascism, and the failure of the left in Brazil. Polit. Geogr. 83, 102186. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102186

della Porta, D., Keating, M., and Pianta, M. (2021). Inequalities, territorial politics, nationalism. Territ. Politic Gov. 9, 325–330. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2021.1918575

Demata, M. (2017). ‘A great and beautiful wall': Donald Trump's populist discourse on immigration. J. Lang. Aggress. Confl. 5, 274–294. doi: 10.1075/jlac.5.2.06dem

Díaz-Barriga, M., and Dorsey, M. E. (2020). Fencing in Democracy: Border Walls, Necrocitizenship, and the Security State. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Dijstelbloem, H., and Walters, W. (2021). Atmospheric border politics: THE morphology of migration and solidarity practices in Europe. Geopolitics 26, 497–520. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2019.1577826

Dillon, M., and Lobo-Guerrero, L. (2008). Biopolitics of security in the 21st century: an introduction. Rev. Int. Stud. 34, 265–292. doi: 10.1017/S0260210508008024

Dorsey, M., and Díaz-Barriga, M. (2011). “Patriotic citizenship, the border wall and the El Veterano Conjunto [The Veteran Tex-Mex Music] Festival,” in Transnational Encounters: Music and Performance at the U.S.-Mexico Border, ed. A. L. Madrid (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 207–228.

Do Rzeczy (2023). Funkcjonariusze SG Protestuja Przeciw Filmowi Holland. ‘Tylko Swinie Siedza w Kinie,' Do Rzeczy. Available online at: https://dorzeczy.pl/opinie/480672/zwiazkowcy-sg-przeciw-zielonej-granicy-ostry-protest.html (accessed December 8, 2023).

Duszczyk, M., and Kaczmarczyk, P. (2022). The war in Ukraine and migration to Poland: outlook and challenges. Inter. Econ. 57, 164–170. doi: 10.1007/s10272-022-1053-6

Eaton, W. W., Bienvenu, O. J., and Miloyan, B. (2018). Specific phobias. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 678–686. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30169-X

Every, D., and Augoustinos, M. (2008). Constructions of Australia in pro- and anti-asylum seeker political discourse. Nations Natl. 14, 562–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8129.2008.00356.x

Fabry, A. (2019). Neoliberalism, crisis and authoritarian–ethnicist reaction: The ascendancy of the Orbán regime. Compet. Change 23, 165–191. doi: 10.1177/1024529418813834

Falke, S. (2012). Peace on the fence? Israel's security culture and the separation fence to the West Bank. J. Borderl. Stud. 27, 229–237. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2012.687504

Fekete, L. (2023). Civilisational racism, ethnonationalism and the clash of imperialisms in Ukraine. Race Cl. 64, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/03063968231152093

Goffe, N., and Grishin, I. (2021). Pandemic COVID-19 and population migration: cases of Italy and Sweden. World Econ. Int. Relat. 65, 118–127. doi: 10.20542/0131-2227-2021-65-12-118-127

Grupa Granica (2023). Cykliczny Raport Grupy Granica z Sytuacji na Pograniczu Polsko-Białoruskim. Grudzień 2022–Styczeń 2023. Available online at: https://hfhr.pl/upload/2023/02/raport-grupy-granica-grudzien-styczen.pdf (accessed August 12, 2023).

Hodge, P., and Hodge, S. (2021). Asylum seeking, border security, hope. Antipode 53, 1704–1724. doi: 10.1111/anti.12756

Isakjee, A., Davies, T., Obradović-Wochnik, J., and Augustová, K. (2020). Liberal violence and the racial borders of the European Union. Antipode 52, 1751–1773. doi: 10.1111/anti.12670

Janecki, S. (2023). Kolejny rozbiór? Sieci 29 (554). Available online at: https://www.sieciprawdy.pl/numer-29-pmagazine-2577.html?utm_source=wsieciandutm_medium=newsletterandutm_campaign=Newsletter%2029/2023 (accessed August 12, 2023).

Johnson, C., Jones, R., Paasi, A., Amoore, L., Mountz, A., Salter, M., et al. (2011). Interventions on rethinking ‘the border' in border studies. Polit. Geogr. 30, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.01.002

Jones, R., Johnson, C., Brown, W., Popescu, G., Pallister-Wilkins, P., Mountz, A., et al. (2017). Interventions on the state of sovereignty at the border. Polit. Geogr. 59, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.02.006

Kazharski, A. (2018). The end of ‘Central Europe'? The rise of the radical right and the contestation of identities in Slovakia and the Visegrad Four. Geopolitics 23, 754–780. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1389720

Kolås, Å., and Oztig, L. (2022). From towers to walls: Trump's border wall as entrepreneurial performance. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 40, 124–142. doi: 10.1177/23996544211003097

Kotwas, M., and Kubik, J. (2019). Symbolic thickening of public culture and the rise of right-wing populism in Poland. East Eur. Polit. Soc. 33, 435–471. doi: 10.1177/0888325419826691

Krasteva, A. (2020). If borders did not exist, Euroscepticism would have invented them or, on post-communist re/de/re/bordering in Bulgaria. Geopolitics 25, 678–705. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1398142

Krzyżanowska, N., and Krzyżanowski, M. (2018). ‘Crisis' and migration in Poland: discursive shifts, anti-pluralism and the politicisation of exclusion. Sociology 52, 612–618. doi: 10.1177/0038038518757952

Krzyżanowski, M. (2018). Discursive shifts in ethno-nationalist politics: On politicization and mediatization of the ‘refugee crisis' in Poland. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 16, 76–96. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1317897

Kuckertz, J. M., Strege, M. V., and Amir, N. (2017). Intolerance for approach of ambiguity in social anxiety disorder. Cogn. Emot. 31, 747–754. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1145105

Letter to the EC (2021). Available online at: https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/euobs-media/59f9f4116a089cec71bf81b76413503a.pdf (accessed August 12, 2023).

Linebarger, C., and Braithwaite, A. (2022). Why do leaders build walls? Domestic politics, leader survival, and the fortification of borders. J. Confl. Resolut. 66, 704–728. doi: 10.1177/00220027211066615

Magyar, B., and Vásárhelyi, J. (2017). Twenty-Five Sides of a Post-Communist Mafia State. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Medycy na Granicy (2021). Facebook Post, November 3. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/medycynagranicy/ (accessed August 12, 2023).

Minca, C., Rijke, A., Pallister-Wilkins, P., Tazzioli, M., Vigneswaran, D., van Houtum, H., et al. (2022). Rethinking the biopolitical: borders, refugees, mobilities. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 40, 3–30. doi: 10.1177/2399654420981389