- 1Department of Economics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Agricultural University of Athens, Athens, Greece

This paper aims to assess the impact of cultural heritage on Greek economic development. An input-output model approach is used to estimate a set of multipliers that measure the direct, indirect and induced (broader) macroeconomic impact of income, output, value added and employment of cultural heritage on economic growth. The multipliers of product, gross value added, income and employment are calculated, based on which the importance of the cultural heritage sector for the Greek economy is identified. Three different impact scenarios were applied to this analysis. The main finding of the study is the importance of the cultural heritage sector in conjunction with its interconnection with the tourism sector. The study provides a policy analysis framework for targeted structural economic interventions that can be implemented to improve the operational efficiency of the cultural sector in Greece.

1 Introduction

Economic growth has been associated with culture. Recent literature focuses on studying the factors that link culture to economic growth and development (Petrakis et al., 2023; Kostis, 2021; Bakas et al., 2020; Kafka et al., 2020; Petrakis et al., 2015). GraŽulevičiute (2006) analyzed the role of cultural heritage toward cultural, environmental, social, and economic development, while UCLG (2010) recognized culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. As noted by Koumoutsea et al. (2023), “culture is related to development in two ways: first, through the economic perspective of culture (such as cultural heritage assets, cultural tourism, etc.); and second, through the inter-connection of culture to education, public policy, local economy, social cohesion, etc.” (UCLG ECOSOC, 2013; Nurse, 2006). Cultural heritage acts as an anchor for social norms and identity formation shaping consumer choices, social behavior and enhancing community resilience (Akerlof and Kranton, 2000). Further, behavioral economics are often employed in recent studies on various cultural heritage issues (Mei et al., 2025; Costanzo and Alderuccio, 2025).

EU set the New European Agenda for Culture, featuring culture's importance for sustainability at European level. As pointed out by Boix Domenech et al. (2021) “the impact of Cultural and Creative Industry (CCI) on the GDP per capita of countries is economically significant on all territorial scales”.

The recent Greek economic crisis brought to light major structural weaknesses in the Greek economy. The industrial and manufacturing sector has shrunk to alarming levels and tourism, a sector of major importance for the Greek economy, suffered as well (Belegri-Roboli et al., 2010). As the relationship between culture and tourism is the most visible aspect of the contribution of culture to development and growth, cultural heritage constitutes one of the main, relatively unexploited development challenges for Greece that could turn into a key driver for its economic growth (Koumoutsea et al., 2023).

This study focuses on measuring the interactions of culture to the rest of the sectors of the Greek economy during the recent financial crisis and hence on providing analytical knowledge on crucial linkages, essential for setting and stimulating public policies.

The Input–Output (I–O) method, a widely accepted scientific method of economic planning and decision-making as noted by Baumol (2000), is used to portray the inter-sectoral transactions of the cultural heritage sector with the rest of the sectors of the Greek economy. The estimates are based on the published Input–Output table for Greece for year 2015. Accordingly, the multiplier method is applied to measure the direct, indirect and induced effects of culture on the country's economy. The study aims to analyze the economy of Greece during the economic crisis that began in 2009 until 2019 to explore the possibility of development through investments in cultural heritage. The period of COVID-19 pandemic was a very different condition that does not reflect economic normality. The study aims to estimate the multipliers of production, income, added value and employment for the cultural heritage sector at a high level of analysis, and to address inter-sectoral interconnections to clearly measure the effects of an increase in the cultural heritage sector demand into the Greek economy.

This type of analytical knowledge is essential for policy makers for designing the relative framework and setting the proper policies toward sustainable and inclusive growth at national level (Dorpalen and Gallou, 2023). Further, the findings of the present study are crucial for Greece, as this is the first attempt to measure the multiplier effect of the cultural heritage sector on the economy.

Beyond these macro-level connections, recent studies highlight how behavioral economics complement cultural economics explaining the decision making of consumers for cultural goods. Coate and Hoffmann (2022) argue that cultural participation and valuation of heritage assets are shaped by social norms and motivations.

Considering other countries such as England, which is a pioneer in the management of cultural heritage, according to the product multiplier results Greece enhances the same development potential. With the proper intervention cultural heritage could play a significance role in the economic development in Greece.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: First, a literature overview of the major studies that analyzed the macroeconomic impact of the cultural sector using the Leontief Multipliers method is presented. Then a brief description of the methodology applied, and the data used follows. Subsequently, the main findings are presented assessed against those of previous studies, accompanied by the results of the estimation of three scenarios to guide policymaking decisions. Finally, the main conclusions and their potential implications are discussed, along with thoughts for further research.

2 Theoretical background literature review of the Leontief input–output impact analysis on cultural sector

Recent literature uses widely the Leontief Input–Output methodology to estimate the necessary multipliers portraying the interactions between economic sectors and their impact on the overall Greek economy to assist policy makers in designing and implementing macroeconomic policies at national and regional level (i.e., Sarris and Zografakis, 2015; Panethimitakis et al., 2000; Sarris and Zografakis, 1999; Sarris, 1990). Various economic impact studies have been carried out using the multiplier method, with a view to interdisciplinary analysis of the cultural industry, both for national and regional purposes. An important advantage of the Input–Output method is the ability to calculate the impact of an increase in demand for the cultural product on our overall national economy.

As UK is a pioneer in cultural economics, many CCI impact studies have been carried out there. CEBR (2013) offered a macroeconomic analysis of the CCI and the impact of cultural industry on the wider economy. This study has excluded the museum industry, which is analyzed in a separate study. The GVA (Gross Value Added) multiplier type II is estimated at 2.43, the product multiplier type II at 2.28 and the employment multiplier type II at 3.01. Furthermore, the study highlighted the additional impact on the economy, brought about by the cultural sector through tourism and the role of art and culture in developing innovative skills and improving national productivity. Further, CEBR (2020) study's main objective was to calculate the economic impact of cultural heritage on the wider UK economy. The GVA multiplier type II of cultural heritage in England was calculated at 2.21, while the employment multiplier type II was calculated at 2.34. Finally, the study pointed out the additional effects on tourism, volunteering and regional development. In Scotland, Dunlop et al. (2004) assessed the multiplier effect of employment type I at 1.83 of Scottish Art Council and the employment multiplier of the museums and galleries at 1.64.

USA leads the use of multiplier analysis as presented in BEA (2013). In USA the most representative study that measures the impact of the CCIs is Americans for the Arts (2024) that highlighted the importance of volunteerism as a vital component that can contribute to the support and funding of the arts and focused on adding value through equity and inclusion. Further, the study of American Alliance of Museums (2017) aimed at capturing the economic value of museums in the national economy through GDP growth, job creation and contributing to government revenues through taxes. The study measured the GVA multiplier type II at 3.2, the employment multiplier at 2 and the income multiplier at 2.2.

In Ireland, Indecon. (2009) calculated the economic impact of organizations supported by the Arts Council as well as the impact of the Arts on the wider Irish economy. The analysis of this study focused on the calculation of the impact on the GVA, government expenditure, government revenue and employment. The study's key findings include the calculation of the (a) public expenditure multiplier type II at 1.28 and (b) employment multiplier type II at 1.6.

In Canada, Conference Board of Canada (2008) calculated the economic footprint of the arts and culture industry using the multiplier method. The product multiplier type II was calculated at 1.84 and the study highlighted seven key factors for the creative industry: consumption, innovation, technology, talent, diversity, social capital, collaboration, capital investment. Another finding of the study was that the cultural sector works as a catalyst for the overall economic prosperity of a country and at the same time a magnet for talent and social cohesion. At regional level, the impact study of Roslyn Kunin and Associates Inc (2013) measured for the city of Nainamo of Canada the output, employment, income and GDP multipliers of the culture industry.

In Japan, using the I–O Analysis (Zuhdi et al., 2013) estimated the output multiplier for Japan's culture industry while Zuhdi (2014) estimated it for the decade 1995–2005.

In Chech Republic, Šlehoferova (2014) using the I–O analysis estimated the output multiplier for the culture industry, signifying the sector's importance to the national economy.

In Greece, the study of Regional Development Institute- Panteion Univ (2017) was the first official mapping of the sector in Greece and its main purpose was to analyze the key economic indicators of the CCI in Greece. The study revealed the existence of regional disparities of the CCI, championed by the region of Attica with an overwhelming share of 75.5% of the GVA, 57.3% of cultural enterprises and 60.8 of the total cultural workers. The remaining 11 regions have a total of 14.3% of the GDP, 27% of employees and 29.1% of enterprises. The Deloitte (2014) study's main objective was to capture the overall impact of investments in the cultural sector within the 4th framework of the Partnership Agreement for the Development Framework programming period in all regions of the country. The product multiplier type II for that 5-year period was calculated at 3.44. Most of the investments concerned infrastructure projects in existing operators, while most of the expenditure related to payroll payments (60%). The study also highlighted that events seem to play an important role in creating economic impacts with a high degree of mobility and Cultural projects seeming to affect tourism and businesses that serve it. Further, the Deloitte (2023) study contributed to the measurement and knowledge acquisition regarding the footprint of cultural and creative activities on the country's economy by analyzing the specific parameters of cultural projects, identifying the affected economic activities, quantifying the impact on a sample of cultural projects and projecting the results for the total National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF), comparing the findings to those of the previous study of 2014. The study using I–O analysis demonstrated that the cultural projects during the programming period of 2014–2020 had a significant impact on the Greek economy, generating an output of €1.56B and resulting in sustaining a significant number of employees. The study showed that compared to the study of Deloitte (2014) there is a significant increase in Output and Employment multipliers for the projects (from 3.16 and 43.42, respectively, to 3.44 and 48.78, respectively) and a slight decrease in Payroll multipliers (from 0.81 to 0.57). The study underlined the increased impact of the projects on tourism, emphasizing the augmented contribution of Culture to the “touristic product” of Greece (in output from 18% to 30%, in employment from 12% to 38% and in payrolls from 12% to 33%) and revealed that Greece's tourism segment alone gains 94 million euros a year from culture activities.

The economic crisis of recent years and the difficulty of finding sources of funding make it necessary to have studies that determine the value of the CCIs. Investments in culture and creativity aim, among other things, to create a region or country as a destination for tourists, permanent work and residence and investment of course. This philosophy helps to completely regenerate an area as a cultural heritage hub and attracts highly innovative companies and high-level human resources (e.g., Dublin).

3 Methods and materials

This study implemented the basic Leontief demand driven model, as presented by Miller and Blair (2009). The basic I–O model is based on the following theoretical assumptions according to Leontief (1966): stable economies of scale, stability of technological factors, product homogeneity, and lack of supply constraints. The basic model I–O is also based on the table of transactions. This table is a dual-entry accounting system that shows how a sector's production on the market of certain other industries is analyzed over a given period. In the Input–Output system, the production function is of fixed dimensions. This assumption essentially implies that input substitution elasticity equals zero.

Using the I–O tables is the most reliable and accurate method for analyzing the impact of various interventions on the national economy. These tables are based on published data, which enhances the transparency and reliability of the method. The most important advantage of the method is that these tables consider the inter-branch relations of the economy in detail.

A multiplier enables an estimate of the impact, which would have a slight exogenous change in the demand for an industry product throughout the economy. Each sector has its own multiplier, reflecting the overall change in income and product of the economy resulting from the change in final demand by one unit. The types of multipliers most used are those that estimate the impact of external changes on (a) the output of the sectors in the economy, (b) the income earned by the household sector in relation to new returns, (c) employment, (d) the added value that each sector creates in the economy due to new costs (Miller and Blair, 2009). The concept of multipliers is based on the difference between the initial effect of an exogenous change and the overall effects of that change. For example, if the multiplier of the cultural sector is 2, it would show that if we increased the industry's production by EUR 100 million, then total production would increase by EUR 200 million.

The first step to calculate the multipliers is the calculation of the technical coefficient (aij) which is the amount of input i needed per unit of output of sector j, and could be derived from where Xjis the value of the total production of industry j and zij is the matrix of sectoral transactions.

Then, the construction of the technical coefficient matrix (A) is possible as well as the inverse Leontief matrix L = (−)−1 and the solution to the (open) Leontief model =(−)− 1Υ.

The Type I multiplier estimates the direct and indirect increase in production in all sectors of the economy, based on an increase in the final demand of an industry by one unit. The multiplier is calculated as the ratio of the total economic result for the whole economy to the initial change. It is calculated as the fraction (direct + indirect)/direct result.

The Type II multiplier estimates the direct, indirect and induced increase in production in all sectors of the economy, in the event of an increase in final demand in the output of the sector concerned by one unit. In this case, the final household consumption sector moves away from final demand and is placed together with the technologically interdependent sectors of Table I–O (closed Input–Output model). In more detail, the income generated by the production process of an additional unit for final demand will cause further changes in consumption, production, employment, income and other primary inputs and for several successive cycles.

The Type I and Type II multipliers show by how much the initial effects are blown up when direct, indirect, and induced effects (due to household spending because of increased household income) are considered. Type I multipliers might underestimate economic impacts and Type II multipliers probably give an overestimate. These two multipliers [Type II and Type I] may be considered as upper and lower bounds on the true indirect effect of an increase in final demand. A more realistic estimate generally lies between the Type I and Type II multipliers.

The most widely used multipliers for analyzing an industry's economic impact on the economy are (Wang and Charles, 2010; D'Hernoncourt et al., 2011):

1. Product multiplier (Omulti):showing the overall change in economic output required to meet the change in final demand by one unit of the sector/product concerned, where the final demand of the remaining products in the economy remains stable. Derived from Omulti=ΣiLij (where Lij is the inverted Leontief matrix of input i needed per unit of output of sector j).

2. Income multiplier (Imulti): which estimates the overall change in household income resulting from a unit change in final demand for the product of an industry, where “v” refers to the household income ratio/total output of each sector Derived from .

3. Employment multiplier ⟦(Emultj): which assesses the relationship between the change in the final demand of a particular sector and the employment required to meet it. It is expressed in physical units (number of employees or equivalent unit of employment per million €, and not in values, i.e., labor costs per unit of product) and shows the immediate change in the number of employees in an industry from the one-unit change in the outflow of that sector, where “w” equals the full-time equivalent employment per € of total production in the industry. Derived from Emultj=ΣiwiLij/wj.

This study used the 2015 Input–Output (I–O) Table published by Greece's National Statistical Office (ELSTAT) in basic prices and product by product, in accordance with the revised ESA 95 national accounts system of 2015, according to which the Greek economy is divided into 65 sectors following the European standards. The symmetrical Input–Output Tables are matrices of the “product-product” that combine both supply and uses. These tables present the structure of production costs and the added value created during the production process; the flows of goods and services produced within the national economy and the flows of goods and services in relation to abroad.

After special processing and analyzing the cultural heritage sector, the table was analyzed in 67 sectors. In the final stage, the Type I and II multipliers of Table 67*67 of the Greek economy were calculated, and the results were processed, and are presented below in the form of tables and diagrams to facilitate the analysis.

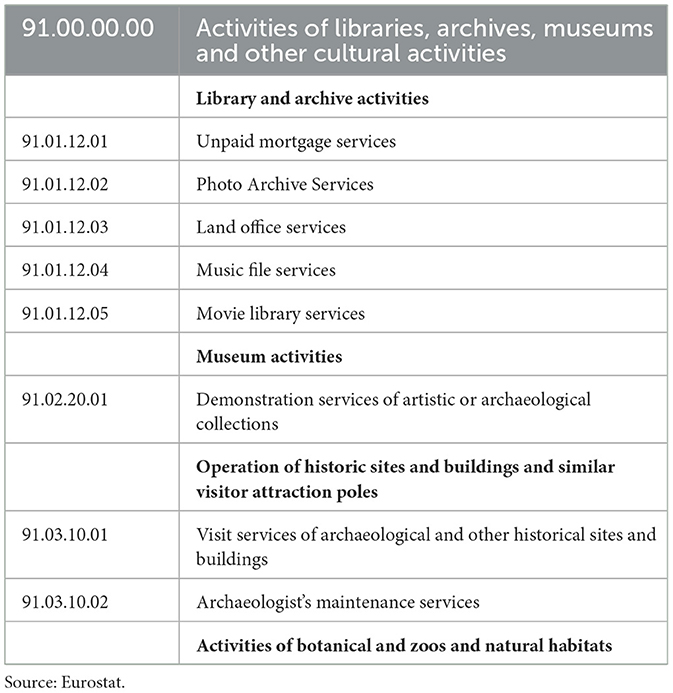

Table 1 below presents in detail the activities of the cultural heritage sector following Eurostat.

4 The contribution of the cultural heritage sector to the Greek economy

This study analyzed the economic impact of the cultural heritage sector on the entire Greek economy. The results below show the impact of an increase in the demand for cultural heritage products on groups created in terms of employment, product and income.

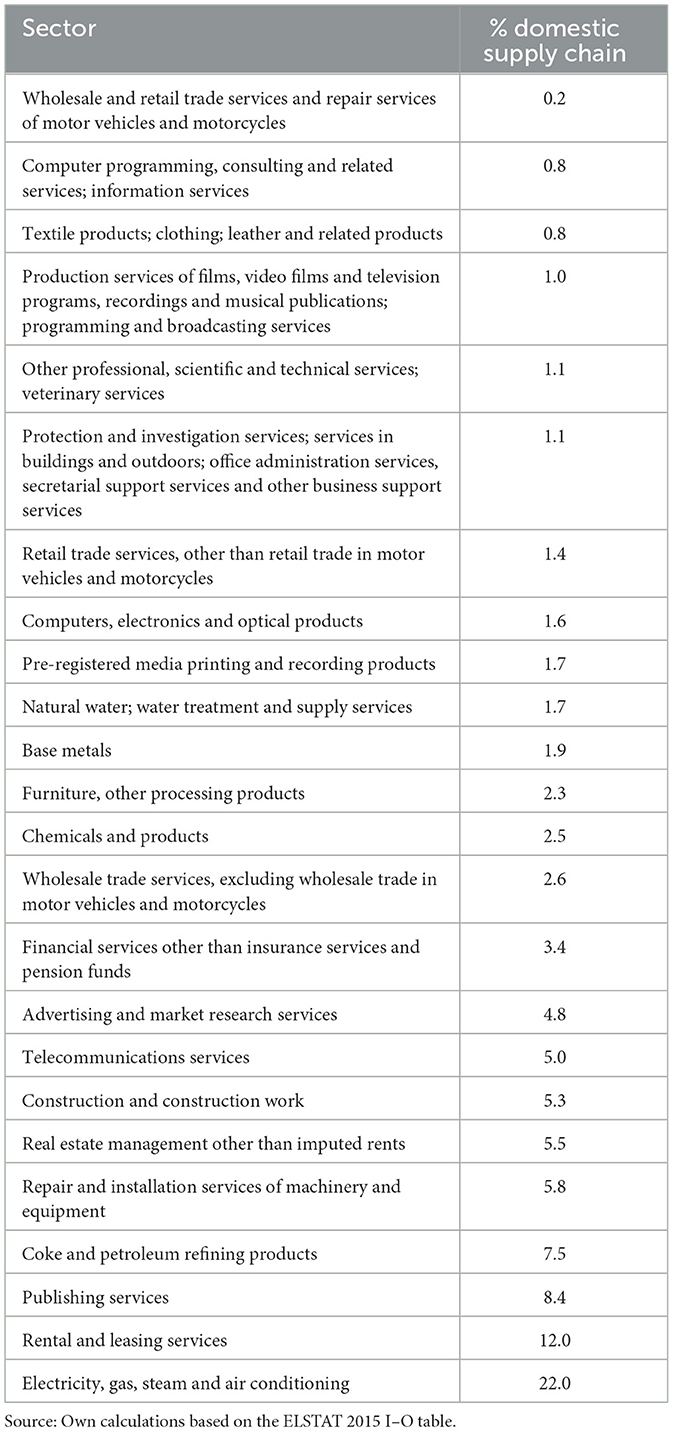

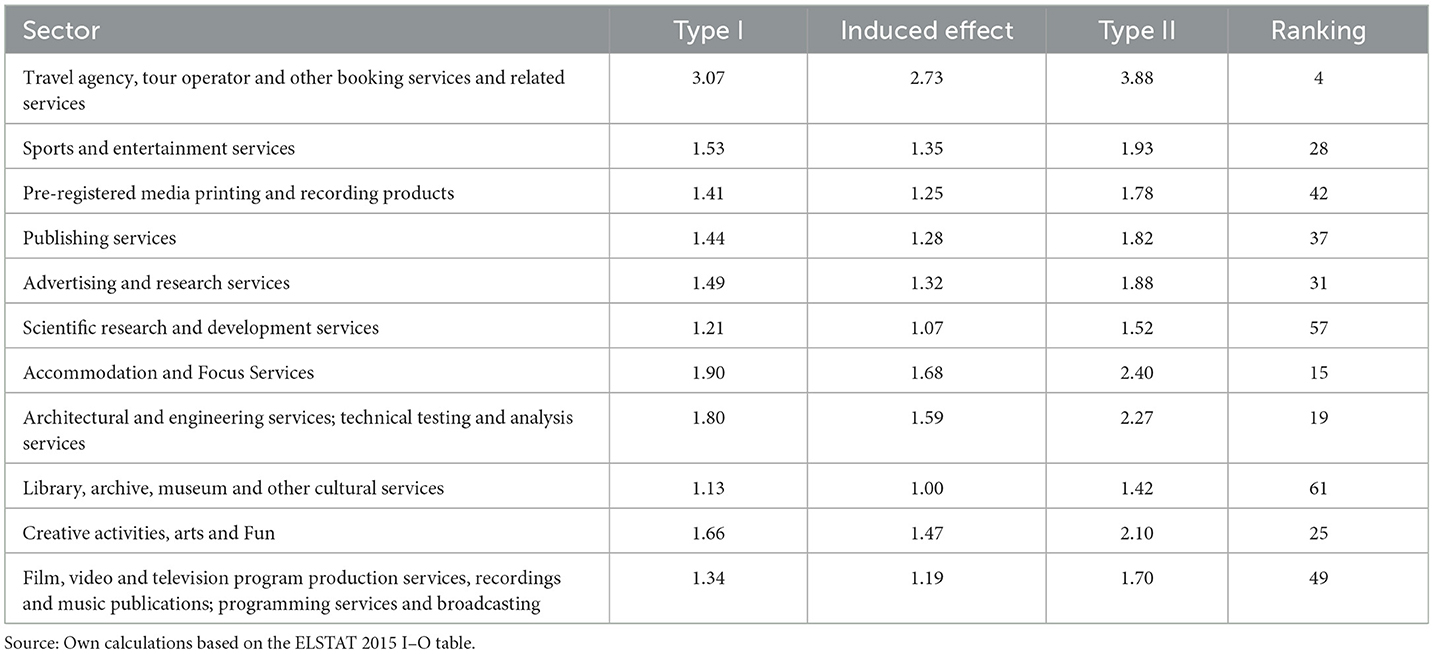

Table 2 below shows that in Greece the effects of the cultural heritage sector are spread across all sectors of the economy. As shown in Table 3, the dominant effect is in the energy sector, followed by rental and publishing services. The corresponding UK results show that the dominant cultural heritage sector effect is in the construction and manufacturing sector with 29.4 and 19.1% respectively (CEBR, 2020).

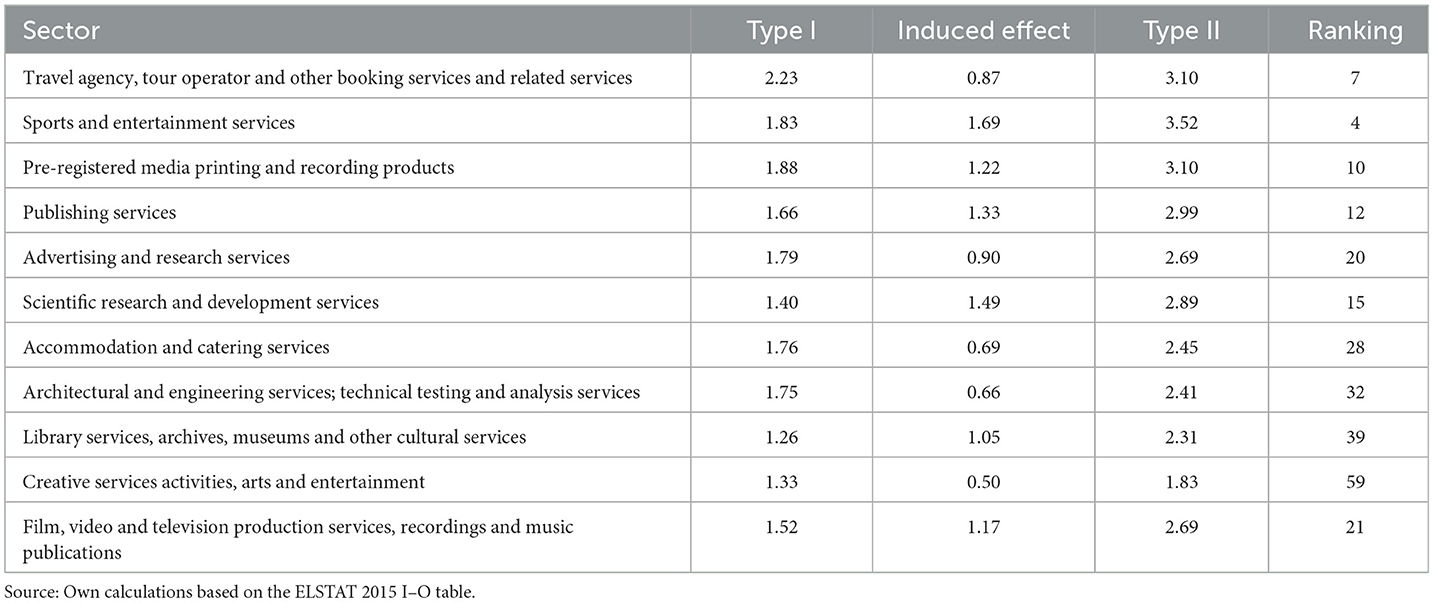

The estimated product multiplier of cultural heritage of Greece was 2.31. This number summarizes the total economic impact (direct, indirect, and induced), expected from the change in economic activity by 1 €. Table 3 below summarizes the results of the Type I & II of product multiplier for selected sectors of the Greek economy, and the following should be noted:

- There is an upward pressure of multiplier effects on all groups of the economy.

- The additional induced effects significantly change the classification of sectors.

- The groups that had the greatest impact are the travel agencies, sports services and printing industries with 3.52 and 3.10, respectively.

- The cultural sector has a total multiplier of 2.31.

- Type II multiplier, as mentioned above, estimates the direct, indirect and induced (induced) increase in production in all sectors of the economy. This means that every 1 € of increase in the production of cultural sector products will result in products worth 2.31 €.

- The impact of the cultural heritage industry is concerned, was estimated €1.05. This means that cultural heritage products supply goods and services to households when direct and indirect workers in the cultural heritage sector spend their profits on the wider economy. So, if the demand for products increases to the cultural heritage sector by 1 €, this will increase the total production of the economy by 2.31 €.

To calculate the employment multiplier, the number of workers/employees was used. In 2015, the number of cultural heritage sector workers/employees was 5,400, while the product produced was 387 million. The full-time equivalent (FTE) for the cultural heritage sector therefore corresponds to 14 (FTE) full-time employment jobs per million euro. Table 4 below, shows the Type I and II multiplier effects of employment on selected sectors of the Greek economy. The Type II employment multiplier was estimated at 1.641. The additional impact was calculated at 0.513 and represents the employment of industries supplying goods and services to households when direct and indirect workers/employees in the cultural heritage sector spend their profits on the wider economy. This means that for each new cultural heritage sector job there will be 1.641 jobs in the economy, due to the combination of direct, indirect and induced impacts.

Table 5 below presents the induced impact of selected sectors of the economy as well as the results of Type I- and II-income multipliers. Income Multipliers type II of the Cultural heritage sector was calculated 1,422, which means that every 1 € increase in the income of cultural heritage sector workers/employees generated 0.422 € on the wider economy. These new worker/employee payments relate to industries from which the Cultural Heritage industry buys goods and services as inputs into its own production processes. The Type II multiplier was estimated at 1,422. The additional impact was estimated at 0.297 and represents the remuneration of workers in industries supplying goods and services to households when direct and indirect workers in the inheritance sector spend their profits on the wider economy.

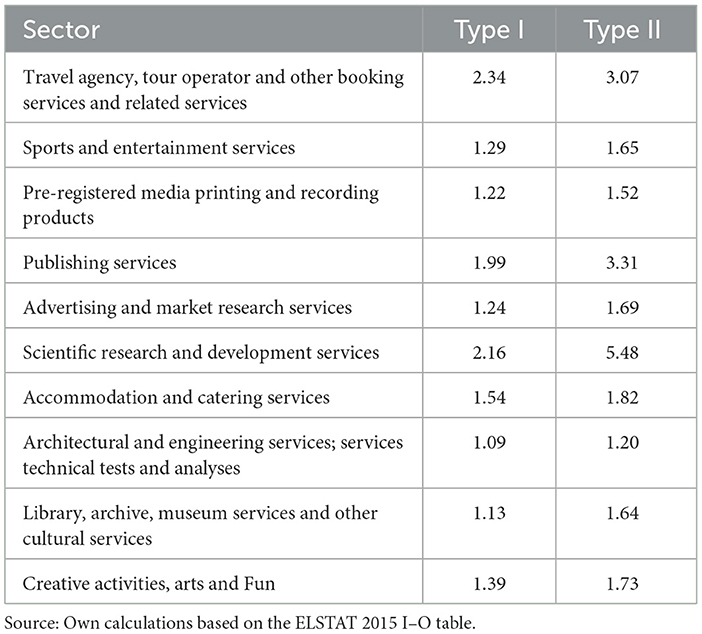

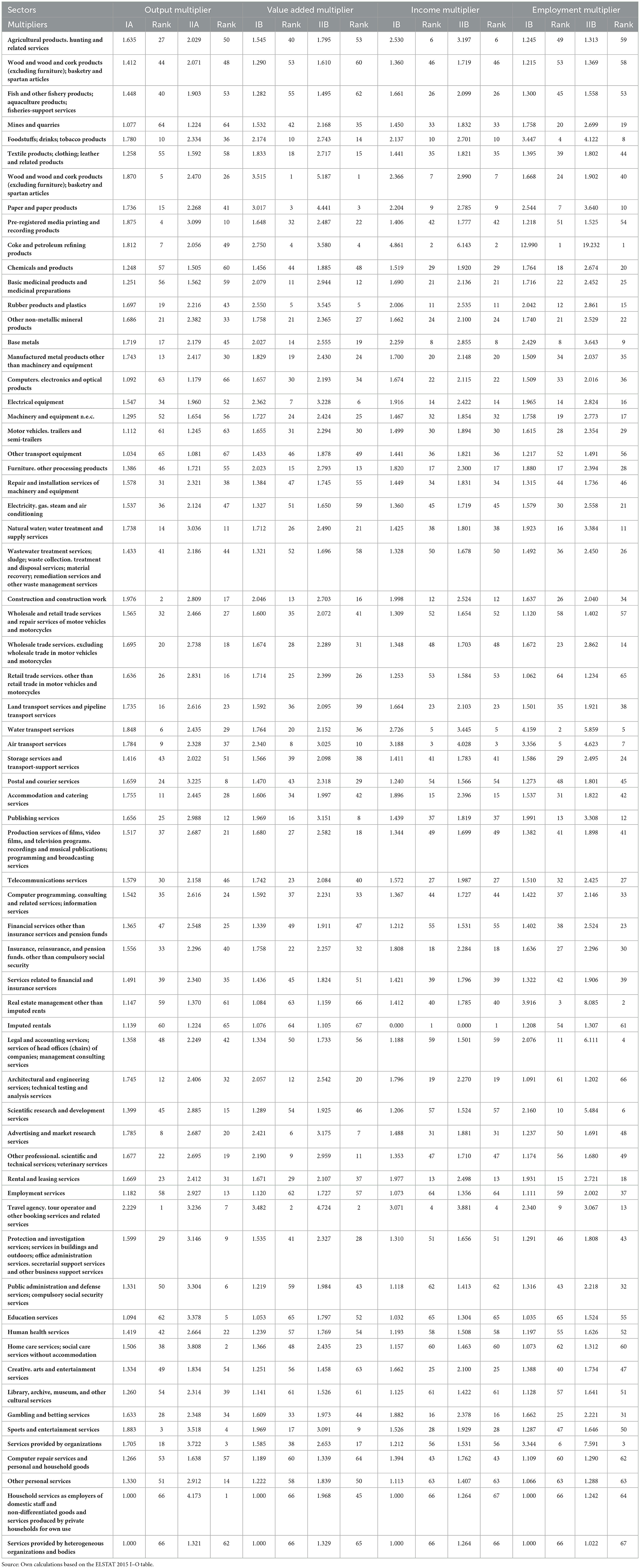

Using the multiplier model, we assessed the contribution of the Cultural Heritage sector to the Greek economy for 2015 and calculated the multipliers of the 67 sectors, as presented in Table 6 below.

5 Scenarios of exogenous effects of final demand

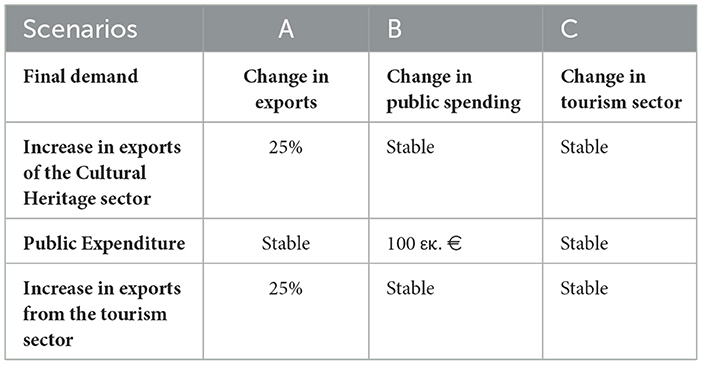

We conducted the analysis that follows, using the 2015 I–O Table of Greece as reference data. The ultimate purpose of the scenarios is to analyze the impact on the Greek economy in the field of cultural heritage sector and the relevant impact on the overall economy as far as income and employment are concerned. The analysis of the scenarios contributes to a better understanding of structural changes in the economy applying different economic policies.

This scenario analysis intents to investigate the best intervention to have the maximum impact in the overall economy considering the structure of the Greek economy and propose the best policy implementations through objective and measurable criteria. In these sections three policy interventions are measured to find the most efficient one. The three interventions are best practices worldwide. The three interventions are the increase of the government fiscal expenditure, export growth of the cultural heritage product and an increase of tourism sector exports. The scenarios of the final change in demand to be used in this study are described in Table 7 below.

The calculation and analysis is then carried out to determine the impact of the changes on the overall production of cultural heritage sector in Greece. Based on the results, policy proposals that must be followed in Greece to maximize the total production of cultural heritage can be documented. According to Nazara et al. (2004), with the following equation we can calculate the results of the scenarios.

In this study t indicates the period of Input–Output tables, i.e., 2015, while t + 1 indicates a future period if we implement the proposed policies of the scenario. Based on the results of the three scenarios assessed below, relative policy proposals on cultural heritage in Greece can be documented.

The Input–Output tables describe, as we have seen, the interdisciplinary production structure of the economy (intermediate consumption), but also the system of value-added creation, such as wages, taxes, imports, etc., recorded in the initial input segment. The traditional Input–Output model assumes that the most important activity is productive (endogenous) and other activities are based and linked to it (extrinsic). The inter-branch productive structure of the economy has been fully and thoroughly explored in the previous ones. Using the logic of investigating the effects on the product produced or distributed, it is possible in the context of the Input–Output model to determine the interdisciplinary effects on employment, imports and income.

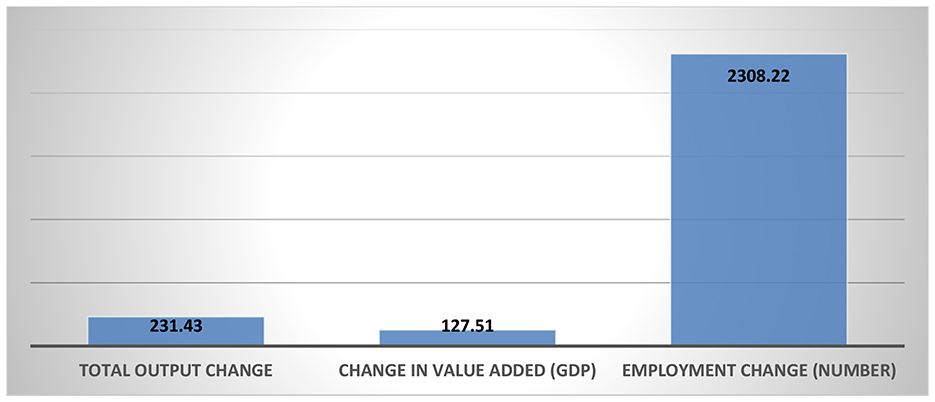

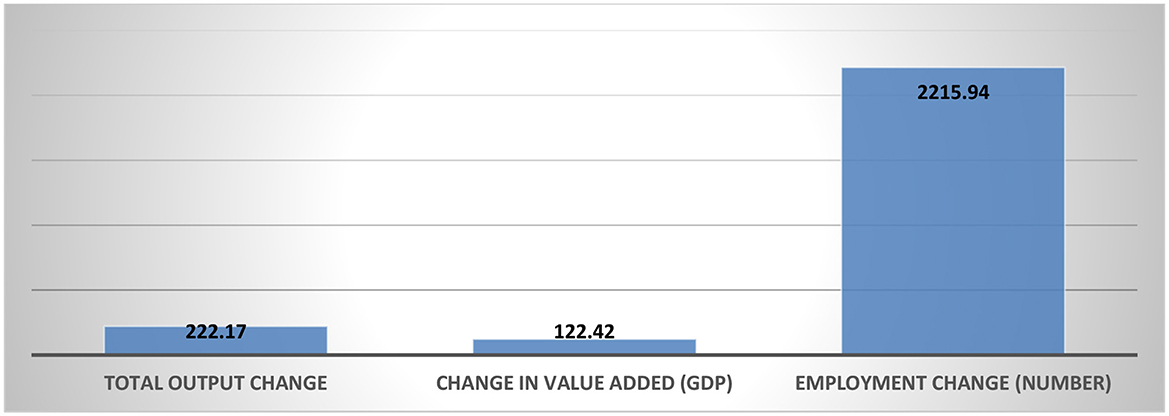

Scenario A applies to an increase in public expenditure on cultural heritage by EUR 100 million. €. The impact such an investment would have on the overall economy is summarized in Figure 1 below. It is evident that this investment would create 2,308 new jobs and add EUR 231.43 million to the Greek economy.

Figure 1. Scenario A: Effects on product, GVA and employment from the increase in public expenditure. Source: Own calculations.

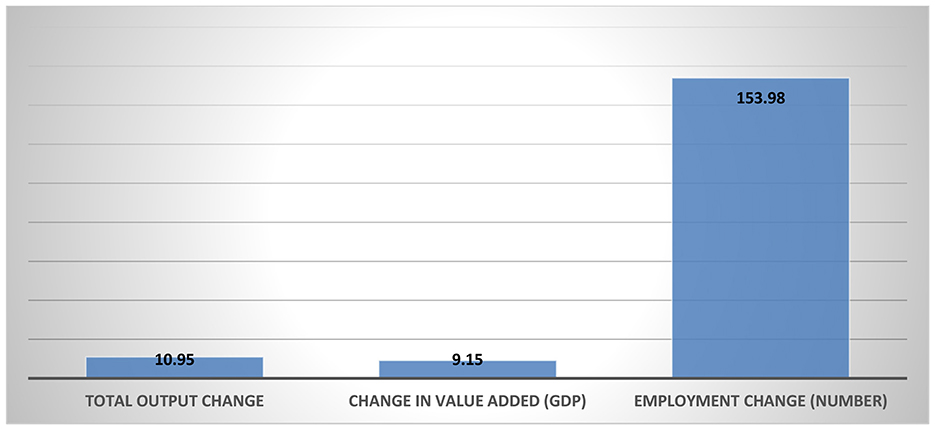

In Scenario B an increase in exports of cultural heritage products by 25% of the total product of the industry is examined. The impact of the €96 m increase in exports of cultural products on the overall economy is summarized in Figure 2 below. It is evident that this investment would create 2,216 new jobs and add EUR 222,417 million to the economy.

Figure 2. Scenario B: Impact on product, GVA and employment from the 25% increase in exports of cultural heritage products (€96 m). Source: Own calculations.

Quoting (OECD, 2009) “Culture and tourism are linked because of their obvious synergies and their development potential. Cultural tourism is one of the largest and fastest growing global tourist markets and cultural and creative industries are increasingly being used to promote destinations. The increasing use of culture and creativity in market destinations also adds to the pressure of differentiation of regional identities and images and increasing the variety of cultural elements used for the branding and marketing of a region”. Therefore, in Scenario C an increase in tourism revenues as an industry directly linked to the cultural heritage sector is examined. Tourists from Europe count for almost 80 % of incoming tourism in Greece. Cultural heritage is of major importance in the choice of destinations for European visitors. The tourism sector is most reflected in the accommodation and catering sector (36), travel agency services (53) as well as air transport (32). In Scenario C we examined a 25% increase in production in exports of the above sectors, and we found that this increase would create 173,397 new jobs and add 15,438 million euros to the economy. In Figure 3 below we distinguish the impact on the overall economy from the above increase.

Figure 3. Scenario C: Impact on product, GVA and employment from the 25% increase in exports from the tourism sector. Source: Own calculations.

Concluding, comparing the findings of the three Scenarios examined, it can be assessed that an increase in the public expenditure of cultural heritage has the greatest impact on the product, GVA and employment of the Greek economy.

6 Conclusions—further Study

In Greece, worldwide known for its cultural heritage due to its ancient history, philosophy and monuments, culture if combined properly to tourism, could become a catalyst for the national economy. This study offers an extensive analysis of the sectoral interconnections of the cultural heritage of the Greek economy, focusing on their impact on product formation, GVA, income and employment.

A comparative analysis of the direct, indirect and induced results in terms of income, production, added value and employment for the cultural sector was carried out in relation to other sectors of the economy.

The study highlighted four key aspects of the economic value of cultural heritage. Initially, the sectoral structure of cultural heritage in the Greek economy (domestic supply chain) is reflected and sectoral interconnections (multipliers) are calculated. In more detail, the multipliers of product, gross value added, income and employment are calculated, based on which the importance of the cultural heritage sector for the Greek economy is identified. Three different impact scenarios were applied to this analysis. The main finding of the study is the importance of the cultural heritage sector in conjunction with its interconnection with the tourism sector. As in Greece the use of the multiplier method for cultural heritage was very limited in the past, the findings of this study are of particular importance for policy makers.

As evidenced, the travel agency industry is one of the sectors with the highest multiplier effects on all economic indicators. At the same time, an important finding was that the contribution of the cultural and creative industries (such as printing, publishing, architects' services, etc.) is very important as their multiplier effect on the Greek economy is particularly high. The cultural heritage with a product multiplier of 2.31 and a ranking of 38 is somewhere in the middle of the 67 sectors of the Greek economy under study. Based on our analysis, the macroeconomic impact of cultural heritage in Greece for 2015 is summarized at EUR 884.73 million € direct, indirect and induced product. Furthermore, it directly and indirectly employs a total of 8,856 employees.

The contribution of the cultural and creative industries continues beyond the direct economic contribution of the sector. The immediate impact is an increase in employment and revenue. In addition to the direct effects, there is also the indirect contribution which refers mainly to the driving force of culture as a locomotive of local development through tourism, the creation of cultural clusters, the diffusion of innovation in the other sectors of the economy as well as to the promotion of territorial and social cohesion. Indirect effects include income generated by cultural tourism (such as the spending of tourists on hotels, restaurants, transport, etc.), enhancing the image of the city, attracting investment, but also improving the quality of life of residents.

Future research connecting behavioral and cultural economics in heritage sector could focus on how social identity and bounded rationality affect cultural participation and provide a better understanding of cultural policies' sustainability (Chuah and Hoffmann, 2022; Uskul, 2015). Hence, bridging micro level behavior and macro level cultural multiplier could allow for a deeper insight to the subject.

In summarizing the indirect and induced effects of the cultural heritage sector, all the results obtained from the above study are possible to capture a very clear picture of the inter-sectoral relations of the Cultural Heritage of Greece. It is also possible to determine how these relationships affected our country's economy with a reference year in 2015. As a result of the above analysis, it can be documented that the Cultural Heritage sector could act as a catalyst for the economic and social wellbeing of the citizens of a country such as Greece. Greece has a comparative advantage due to its cultural wealth and the development of cultural tourism beyond the seaside holiday could fuel the long-term economic growth of our country, by reducing seasonality, increasing investment and employment, as well as enhancing regional development.

The most efficient policy implementation according to analysis above is the increase of government fiscal expenditure. Specifically targeted investment in heritage through direct funding, tax incentives and grants and loans can significantly promote cultural heritage development. Furthermore, alongside policies that encourage cultural exports through promotional campaigns, encourage the export of cultural export, provide training and resources and initiate and built international collaboration could create jobs, boost tourism, and enhance national identity. To maximize synergy, these policies should be integrated with other sectors. The sectors with the most linkages to cultural heritage in the Greek economy are tourism, education, and technology. Some of the most efficient measures worldwide and best practices have shown that the combination of policy measures fostering a holistic approach to cultural heritage management and economic growth overcome the challenges that arise.

The link between tourism and the rich cultural heritage of our country should therefore become the primary objective of the strategy that will follow. Through the comparison of the three scenarios, the increase in public expenditure gives the greatest multiplier effects to the cultural heritage sector, but also to the overall economy. An increase in public expenditure by 100 million EUR would create 2,308 new jobs and add €231.43 million worth of product to the economy.

The findings of this survey showed a strong cross-sector relationship with tourism and that the overall economic value of cultural heritage is greater than the sum of all its financial elements. In this study, the contribution of Cultural Heritage was expressed mainly in economic terms, but cultural heritage still has great social, environmental and cultural value individually, for a society, but also for the whole country.

The findings of this study could be very important for policymakers if the analysis was repeated after a decade and the results were critically evaluated against those of the present study.

International experience is rich in examples where the successful application of this new approach to the economic value of cultural heritage reversed decline and led to economic and social reconstruction in many countries. These countries created strategic frameworks for Cultural Heritage based on in-depth scientific studies to distribute their budgets more productively and with a sense of fairness. The public targeted by the impact studies of cultural policies, and as we have seen several in the last 20 years, unfortunately they are not considered by the policymakers, often do not even know their existence (Kiss, 2016).

It is imperative that impact analyses on cultural heritage also consider the values that artists and/or cultural organizations themselves consider important such as social, political, recreational, freedom, and justice issues. The economic impact analyses will be useful and make cultural policies economically viable only when the above values are included in the national cultural strategies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akerlof, G. A., and Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. Q. J. Econ. 115, 715–753. doi: 10.1162/003355300554881

American Alliance of Museums (2017). Museums as Economic Engines: A National Report, An Economic Impact Study for the American Alliance of Museums, Oxford Economics. Washington, DC: American Alliance of Museums.

Americans for the Arts (2024). Arts and Economic Prosperity 6: The Economic and Social Impact Study. Washington, DC: Americans for the Arts.

Bakas, D., Kostis, P., and Petrakis, P. (2020). Culture and labour productivity: an empirical investigation. Econ. Model., 85, 233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2019.05.020

Baumol, W. J. (2000). Review: out of equilibrium. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 11, 227–233. doi: 10.1016/S0954-349X(99)00021-1

BEA (2013). RIMS II: An essential tool for regional developers and planners. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce.

Belegri-Roboli, A., Markaki, M., and Michaelides, P. (2010). Intersectoral Relations in the Greek Economy. Athens: INE-GSEE Studies.

Boix Domenech, R., De Miguel Molina, B., and Rausell Köster, P. (2021). The impact of cultural and creative industries on the wealth of countries, regions and municipalities. Eur. Plann. Stud. 30, 1777–1797. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2021.1909540

CEBR (2013). The Contribution of the Arts and Culture to the National Economy, Report for Arts Council England and the National Museums Directors' Council. London: CEBR.

Chuah, S. H., and Hoffmann, R. (2022). “Culture and economic behaviour: evidence from an experimental-behavioural economics research programme,” in Behavioural Business: The Psychology of Decisions in Economy, Business and Policy Contexts, eds. J. Blijlevens, M. Elkins, and A. Neelim (Singapore: Springer Nature), 37–81.

Coate, J., and Hoffmann, R. (2022). The behavioural economics of culture. J. Cult. Econ. 46, 3–26. doi: 10.1007/s10824-021-09419-2

Conference Board of Canada (2008). Compedium of Reeseach Papers: The International Forum on the Creative Economy. Ottawa, ON: Conference Board of Canada.

Costanzo, E., and Alderuccio, D. (2025). Culture and heritage for a just transition to climate-neutral and smart cities. Text mining supporting New European Bauhaus elements detection. Front. Sustain. Energy Policy. 4:1613079. doi: 10.3389/fsuep.2025.1613079

Deloitte (2014). Assessing the Socio-Economic Impact of Cultural Projects in Greece. Athens: DeloitteGreece.

Deloitte (2023). Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of Cultural Projects in Greece. Athens: DeloitteGreece.

D'Hernoncourt, J., Cordier, M., and Hadley, D. (2011). Input–Output Multipliers Specification Sheet and Supporting Material (Brussels, Belgium: Spicosa Project Report, Université Libre de Bruxelles – CEESE), 1–25.

Dorpalen, B. D., and Gallou, E. (2023). How does heritage contribute to inclusive growth?. J. Cult. Herit. Manage. Sustain. Dev. doi: 10.1108/JCHMSD-03-2022-0050

Dunlop, S., Galloway, S., Hamilton, C., and Scullion, A. (2004). Economic Impact Report of Cultural Sector in Scotland. Glasgow: Fraser of Allander Institute.

GraŽulevičiute, I. (2006). Cultural heritage in the context of sustainable development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 37, 74–79. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3626.3202

Indecon. (2009). Assessment of the Economic Impact of the Arts in Ireland: Arts and Culture Scoping Research Project submitted to the Arts Council. Dublin: Indecon.

Kafka, K. I., Kostis, P. C., and Petrakis, P. E. (2020). “Why coevolution of culture and institutions matters for economic development and growth?,” in Perspectives on Economic Development-Public Policy, Culture, and Economic Development. London: IntechOpen

Kiss, F. (2016). “The education of information and knowledge management of Cultural Heritage,” in Proceedings of TCL2016 Conference: Tourism and Cultural Landscapes: Towards a Sustainable Approach (Hungary: Budapest), 316–325.

Kostis, P. C. (2021). Culture, innovation, and economic development. J. Innov. Entrep. 10, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13731-021-00163-7

Koumoutsea, A., Boufounou, P., and Mergos, G. (2023). Evaluating the creative economy applying the contingent valuation method: a case study on the Greek cultural heritage festival. Sustain. Special Issue Creat. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 15:16441. doi: 10.3390/su152316441

Mei, W. B., Li, K., and Huang, Y. Z. (2025). Constructing an evaluation index system for the tourism value of Guangdong's maritime silk road cultural heritage. Front. Sustain. Tour. 4:1645348. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1645348

Miller, R. E., and Blair, P. (2009). Input–Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nazara, S., Guo, D., Hewings, G. J., and Dridi, C. (2004). PyIO: Input–Output analysis with Python (No. 0409002). Germany: University Library of Munich.

Nurse, K. (2006). Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development; Commonwealth Secretariat. London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Panethimitakis, A., Athanassiou, E., and Zografakis, S. (2000). “Assessing structural change,” in 13th International Conference of International Input–Output Association on Input–Output techniques, Macerata, Italy.

Petrakis, P. E., Kostis, P. C., Kafka, K. I., and Kanzola, A. M. (2023). Cultural Change and Development and Growth. In The Future of the Greek Economy: Economic Development through 2035 (Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland), 99–113.

Petrakis, P. E., Kostis, P. C., and Valsamis, D. G. (2015). Innovation and competitiveness: culture as a long-term strategic instrument during the European Great Recession. J. Bus. Res. 68, 1436–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.029

Regional Development Institute- Panteion Univ (2017). Mapping the Cultural and Creative industries in Greece. Athens, Greece: Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports

Roslyn Kunin and Associates Inc. (2013). Nainamo Arts and Culture Economic Impact Study. Canada: Nainamo Economic Development Co.

Sarris, A. (1990). A Macro-Micro Framework for Analysis of the Impact of Structural Adjustment on the Poor in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development.

Sarris, A., and Zografakis, S. (2015). “The distributional consequences of the stabilization and adjustment policies in Greece during the crisis, with the use of a multisectoral computable general equilibrium model,” in Bank of Greece Working Paper.

Sarris, A. H., and Zografakis, S. (1999). A computable general equilibrium assessment of the impact of illegal immigration on the Greek economy. J. Popul. Econ. 12, 155–182. doi: 10.1007/s001480050095

Šlehoferova, M. (2014). “Creative industries in an economic point of view–the use of Input–Output analysis,” in 5th Central European Conference in Regional Science (Košice: Technical University), 890–899.

UCLG (2010). Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://cultureactioneurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/UCLG-Culture-4th-Pillar-ENG1.pdf (Accessed November 10, 2023).

UCLG ECOSOC (2013). The Role of Culture in Sustainable Development to Be Explicitly Recognized. Available online at: http://arsiv.uclg-mewa.org/doc/kultur_vHYBe.pdf (Accessed November 10, 2023).

Uskul, A. K. (2015). “The role of economic culture in social relationships and interdependence,” in Social Relations in Human and Societal Development, eds. C. Psaltis, A. Gillespie, and A. N. Perret-Clermont (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 145–165.

Wang, J., and Charles, M. B. (2010). “IO based impact analysis: a method for estimating the economic impacts by different transport infrastructure investments in Australia,” in ATRF 2010: 33rd Australasian Transport Research Forum (Canberra, Australia: Australasian Transport Research Forum), 1–24.

Zuhdi, U. (2014). Analyzing the role of creative industries in national economy of Japan: 1995-2005. Open J. Applied Sci. 4, 197–211. doi: 10.4236/ojapps.2014.44020

Keywords: cultural heritage, Greece, input-output analysis, multipliers, sustainable development

Citation: Koumoutsea A, Sarris A, Zografakis S and Boufounou P (2025) Evidence-based cultural policies toward sustainable development: the case of Greece. Front. Behav. Econ. 4:1489282. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2025.1489282

Received: 31 August 2024; Accepted: 16 October 2025;

Published: 14 November 2025.

Edited by:

Anwesha Mukherjee, University of Reading, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Koumoutsea, Sarris, Zografakis and Boufounou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paraskevi Boufounou, cGJvdWZvdW5vdUBlY29uLnVvYS5ncg==

Aikaterini Koumoutsea1

Aikaterini Koumoutsea1 Paraskevi Boufounou

Paraskevi Boufounou