- 1International Livestock Research Institute (Senegal), Saint Louis, Senegal

- 2Columbia Climate School, International Research Institute for Climate and Society, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, United States

- 3Ziguinchor University, Ziguinchor, Senegal

- 4International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (Mali), Bamako, Mali

Gender mainstreaming in the dissemination and adoption of climate-smart agricultural technologies (CSA) and access to the climate information services (CIS) can help mitigate the effects of climate change and reduce specific disadvantages suffered by women and young people. In this study, we are addressing gender and age-related disparities in CSA and climate information services (CIS). Focusing on 473 households in the Thies, Louga and Kaffrine regions of Senegal, the results of the average treatment effect (ATE) method reveal a higher rate of resilient seed adoption among women. However, the rate of adoption of micro-dosing techniques and the use of climate information are higher among youth. A negative and significant adoption gap (GAP) confirms that not all of the population had been exposed to CSA and CIS technologies, hence the existence of a non-exposure bias justifying further dissemination. These results indicate that future initiatives should focus not only on broadening their reach but also on customizing delivery approaches to address gender and age disparities in adoption capacity. Such targeted efforts would enhance the overall impact of CSA and CIS programs while fostering more equitable and inclusive climate adaptation pathways in Senegal.

JEL Classification: O33, Q12, J16.

1 Introduction

Storms, floods, and drought (GIEC, 2021) have prompted UNESCO (2020) to call for changes in behavior and a reorganization of social structures. In Senegal, these climatic phenomena are reflected in irregular rainfall, resulting in water shortages and reduced agricultural yields, which can exacerbate food insecurity. Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) has emerged as a key strategy to enhance smallholder resilience by combining practices that improve productivity, strengthen adaptive capacity, and reduce environmental impacts (Ariom et al., 2022; Barasa et al., 2021; Arslan et al., 2015). Despite this, adoption of CSA practices among smallholder farmers across West Africa remains uneven, often shaped by socio-economic conditions, institutional support, and access to relevant climate information (Nantongo et al., 2021; Ouédraogo et al., 2019; Zougmoré et al., 2019).

Senegal's agriculture remains largely rain-fed, with irrigated farmland accounting for only 5% of the total harvested area of approximately 2.3 million hectares (Xie and Ringler, 2015). Women typically farm smaller plots and often lack access to important agricultural inputs, as well as information, and credit, exacerbating a gender productivity gap and increasing vulnerability to climate change (DAPSA, 2020; UN Women Africa, 2019; Derenoncourt and Jaquet, 2022). National policies—including the 2010 law on parity, the Emerging Senegal Plan (PSE, 2014), and the National Strategy for Gender Equity and Equality (SNEEG 2, 2016–2026)—have advanced gender equality, but disparities persist. Senegal ranks 113th out of 144 countries in gender inequality, with a gender inequality index of 55.2 in 2020 (EM2030, 2020). In sub-Saharan Africa, where women hold two-thirds of agri-food sector jobs, equitable access to agricultural services and inputs is essential to reducing these disparities (Nelson and Huyer, 2016). Differences in climate vulnerability are rooted in social structures and discriminatory norms that shape access to resources, income, time, and services (FAO, 2023), highlighting the need to address gender and age-related disparities in CSA and climate information services (CIS).

These conditions affect their ability to generate income, emphasizing the need to integrate gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) into interventions focused on promoting access to the climate information system (CIS) and the use of climate-smart agricultural technologies (CSA).

The “Accelerating Impacts of CGIAR Climate Research for Africa” (AICCRA) project promotes CSA adoption with attention to reducing gender and age-related disparities. Yet integration of gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) into productive activities depends largely on the capacity of Multidisciplinary Working Groups (GTP) and the National Civil Aviation and Meteorology Agency (ANACIM) to induce behavioral change. Diffusion of innovations—the process by which new technologies are communicated through social systems over time (Rogers, 1995)—is critical. Awareness of CSA and CIS, conveyed through radio, mobile phones, demonstration plots, and extension services, precedes behavioral change, which can occur at both individual and community levels.

AICCRA-Senegal designs communication strategies that are tailored to local contexts. Community radio broadcasts are timed for target populations, online platforms such as Jokolanté and iSAT deliver CSA awareness, and agricultural demonstration plots provide hands-on learning. Female extensionists often lead awareness activities to facilitate trust and participation among women. Mobile phone access remains limited in some rural areas, particularly for women, highlighting persistent structural barriers to information dissemination.

This study assesses how women and youth engage with CSA and CIS technologies disseminated through AICCRA, aiming to inform GTP and ANACIM strategies to reduce disparities in agricultural technology adoption. We focus on CSA technologies including climate-resilient groundnut and cowpea seeds, participation in demonstration plots, visits to technology parks, and receipt of climate information for agricultural decision-making. Our research question is: “Which dynamics influence the adoption of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices and climate information services (CIS) among smallholder farmers, and what are the implications for equitable climate adaptation?” We hypothesize that diffusion of CSA and CIS is partial, producing disparities in adoption across sub-populations.

2 Materials and methods

2 . 1 Study area

AICCRA-Senegal operates in the regions of Kaffrine, Thiès and Louga, accounting for one-fifth of the national territory, with a population which relies primarily on rain-fed agriculture1 as their main activity. Average annual rainfall in the Thiès region is between 400 to 600 mm, compared with 300 mm in the Louga region, and 400 to 860 mm in the Kaffrine region. In terms of the socio-demographic characteristics of farming households, agriculture is mainly dominated by men ANSD, (2023a),b,c. Indeed, the proportion of women in charge of plots is only 10% and 15% in the Louga and Kaffrine regions, respectively. The Thiès region specializes mainly in horticulture, while food crops (millet, maize, sorghum and rice) dominate in Louga and Kaffrine regions. However, in Louga, 38.6% of plots are devoted to crops such as cowpeas, watermelons, cassava and bissap (ANSD, 2023a,b,c).

The Thiès region boasts significant hydro-agricultural potential, making it an area of intense market gardening activity. Dior soils account for 70% of arable land. The Louga region, on the other hand, is characterized by brown and red-brown soils, lateritic outcrops and tropical ferruginous soils with little leaching. After Dakar, the Thiès region has the greatest economic potential in Senegal. It owes its favorable economic position to the dynamism of the agriculture, livestock, fishing, tourism, crafts, trade and mining sectors (ANSD, 2023b). The economy of the Louga region depends mainly on agriculture and livestock, two sectors that are particularly vulnerable to climatic conditions. The overwhelming majority of the region's population lives in rural areas, i.e., 78.3% (ANSD, 2023c). The region's main economic activities are agriculture, livestock breeding, forestry, trade, handicrafts, women's entrepreneurship and land transport (ANSD, 2023a).

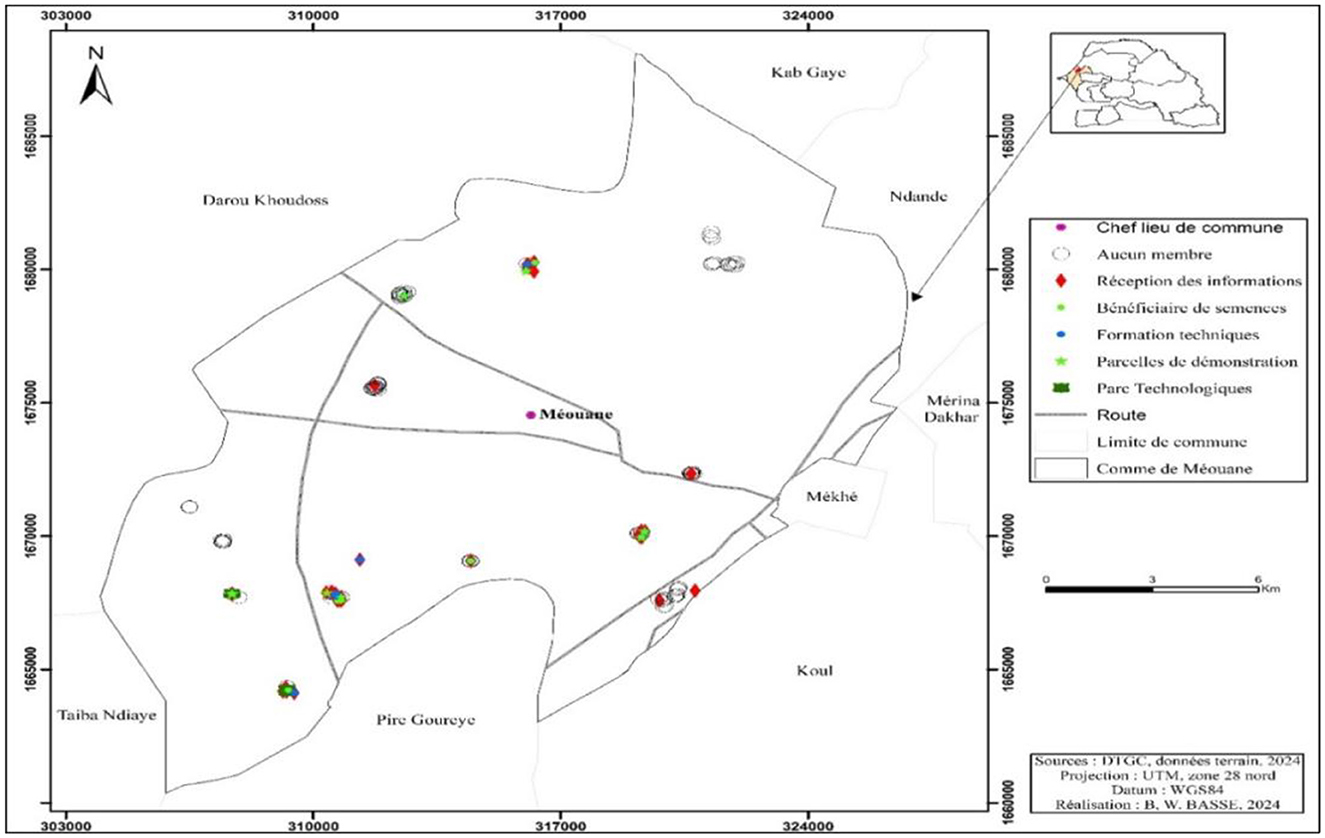

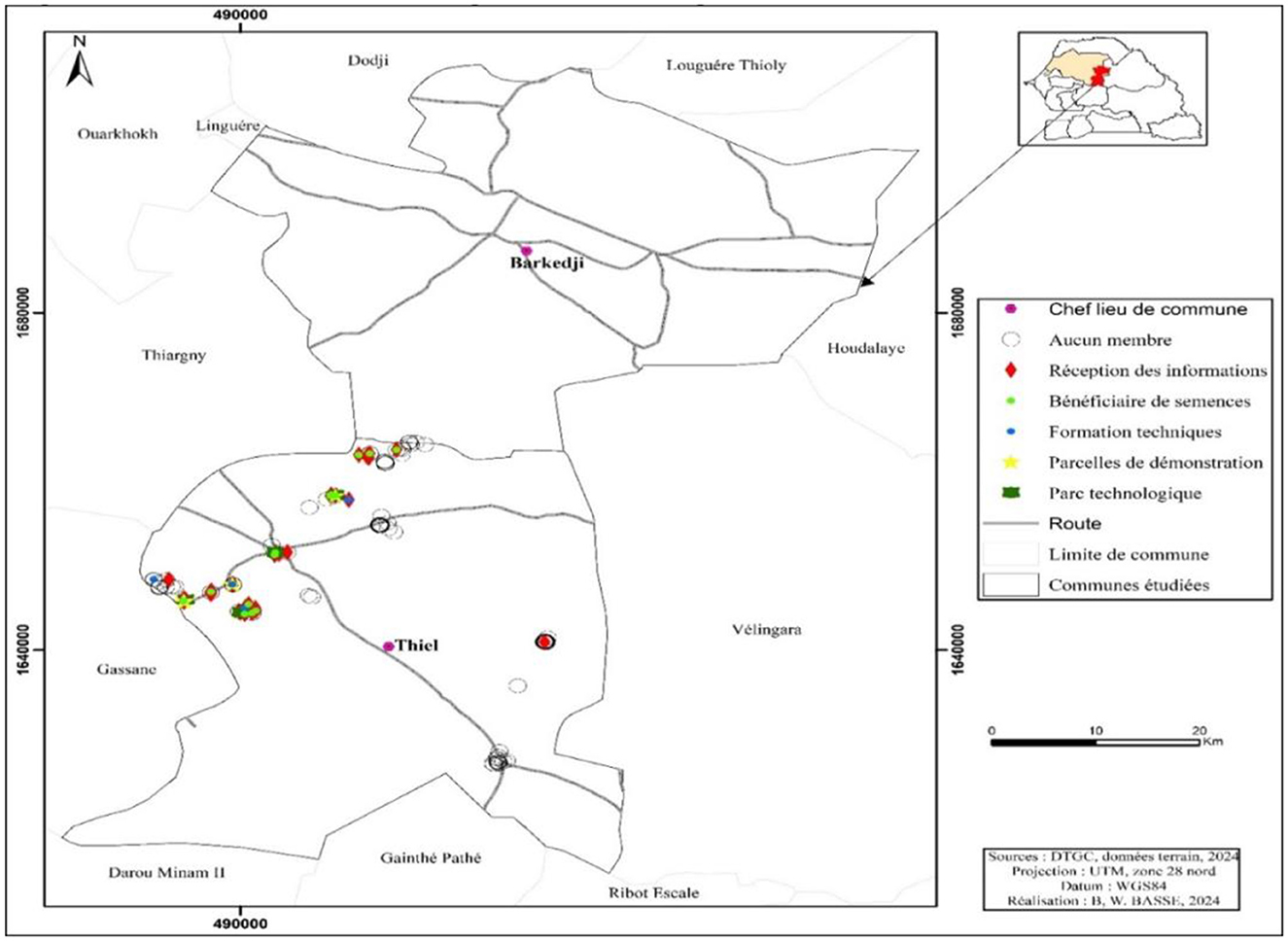

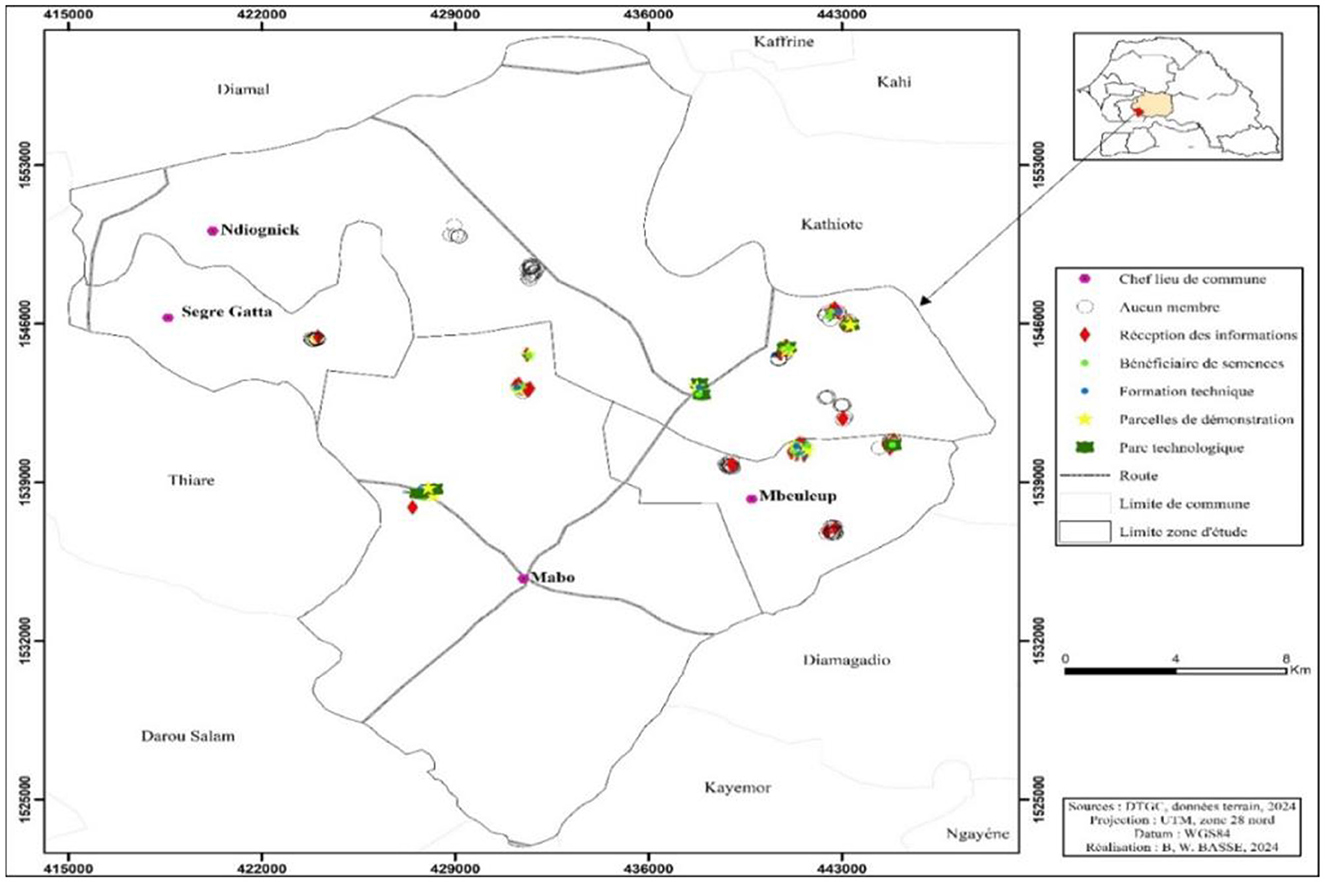

2.2 Distribution of CSA and CIS technologies

Figures 1–3 show relatively even distribution of CSA and CIS technologies across the three regions, with 31.0%, 30.4% and 38.5% of households in Thiès, Louga, and Kaffrine, respectively, being exposed to at least one technology. When analyzed by technology type, climate information reached the largest share of households (33.6%, n = 159), followed by resilient seeds (19.0%, n = 90) and microdosing techniques2 (14.2%, n = 67).

In terms of CIS, it was delivered by mobile phone. Seasonal forecasting included: seasonal length of the season, onset of rains, as well as the end-of-season end decadal forecast on rainfall with information on intensity of the rainfall.

In the case of resilient seeds, technicians from ANCAR played an essential role, providing exhaustive monitoring of the process from sowing to harvesting, ensuring that participants had a thorough understanding of each stage. Their involvement covered producers' choices, seed placement, sowing follow-up, maintenance, harvesting and seed conservation. Their presence at every stage ensured constant monitoring and proactive adaptation to the specific needs of each beneficiary. Before the start of each campaign, a communication campaign was launched to inform all stakeholders of the arrival of the seeds and the announcement of the year's agricultural season. Producers were then organized into cooperatives to foster close collaboration and collective management of resources. Once the seeds had been received, they were distributed, followed by monitoring. Each beneficiary was closely monitored by an agent. Regular exchanges take place between producers and agents/technicians, with particular emphasis on advice throughout the agricultural cycle, including the germination phase and the fertilizer application period. Effective pest control measures were put in place, with ANCAR supplying all seed beneficiaries with phytosanitary products.

2.3 Data collection and descriptive statistics

The survey was carried out in Wolof by AICCRA among 473 households in the Thiès, Louga and Kaffrine regions using a three-stage stratified sampling method. In the first stage, a sample of five communes corresponding to primary units was drawn at random; in the second stage, a sample of 41 villages/quartiers was drawn at random. Finally, in the third stage, a list of 473 randomly selected farming households were surveyed.

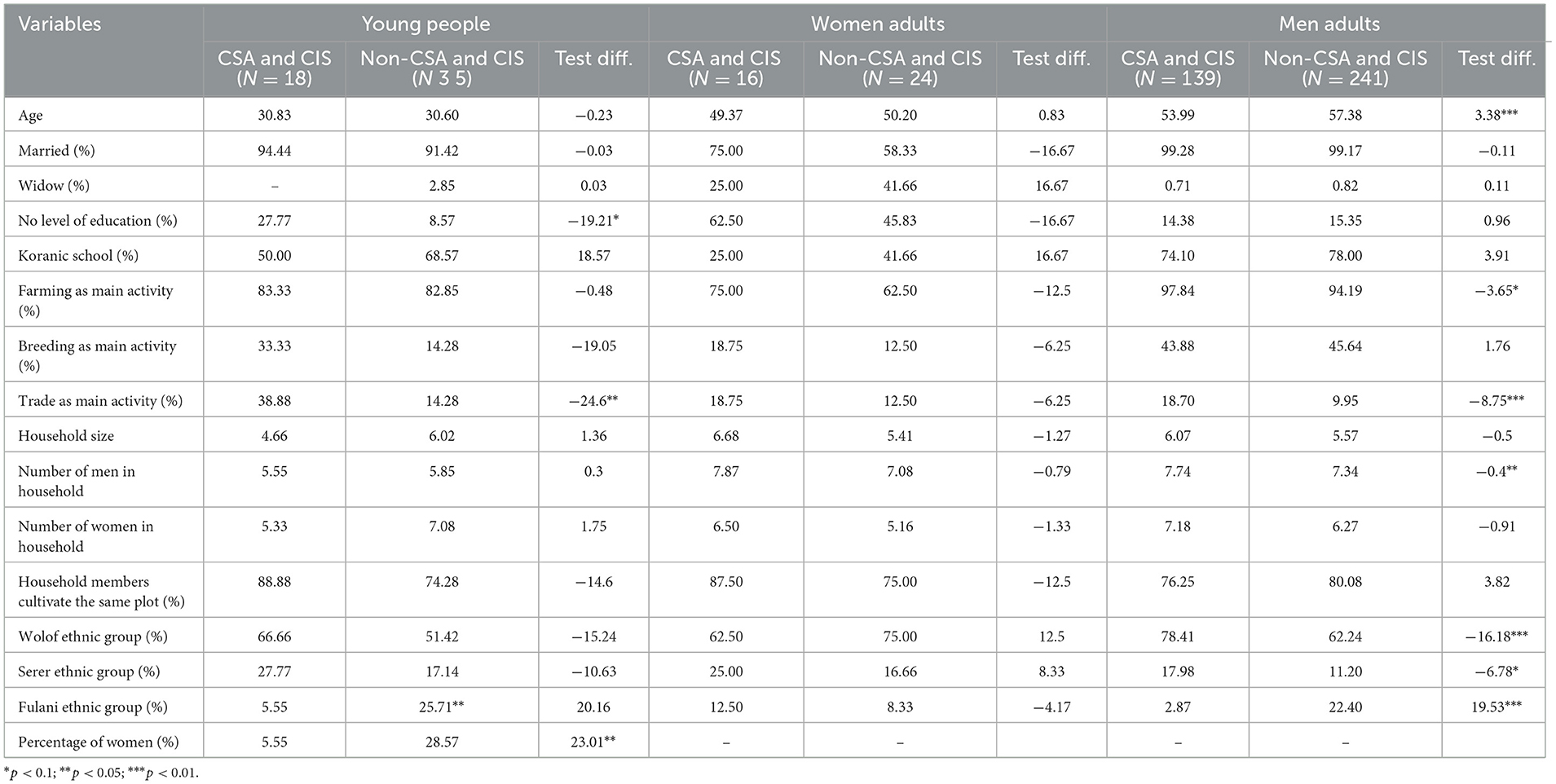

Table 1 outlines the socio-demographic characteristics of the different groups of technology users and non-users. For the purposes of the analysis, we used the 15–35 age group, according to the definition of young people in the African Union charter. Of households surveyed, 80.3% were headed by adult males. This can be attributed to the targeting of heads of households, resulting in few young heads of household being represented. This reflects the country's sociological structure, where large families typically live together in the same compound, with a head of household responsible for resource distribution.

Wolof is the majority ethnic group. The vast majority of heads of household are married. Widowhood is more widespread among adult women, where 41.7% of non-CSA&CIS women are widows. This reflects the reality of the country in general, and of the zone in particular, where tradition grants men a monopoly of authority within the family, and the woman is only head of household in the event of the man's death.

Of all three categories, the level of education is lowest in the female population. Most male heads of household have attended Koranic school: 74.1% and 78% in both types of household in the adult male category. Agriculture is the main activity. However, while most household members cultivate the same plot of land, livestock farming is still dominated by adult men, and trade is more developed among youth.

2.4 Method for estimating the average treatment effect (ATE)

The conceptual framework of the ATE estimation model is based on the causal model of (Rubin 1974) which is generally adapted to the analysis of the situation in which a treatment may or may not be administered to an individual. In the context of adoption, the status of the treatment corresponds to the status of exposure to the technology. Exposure is defined as knowledge of the technology, made possible by public information and awareness. In the context of our study, exposure means knowledge of CSA and CIS technologies. Let a binary variable determining the status of exposure to CSA and CIS technologies. ti = 1 means that the producer has been exposed to CSA and CIS technologies (and therefore knows about them) and ti = 0 means that he has not been exposed. Exposure is assumed to have an effect on the adoption of CSA and CIS technologies, which is an outcome variable.

The causal model of Rubin (1974) considers that for a given outcome variable, there are two potential outcome variables, corresponding to what an individual's situation would be under each of the alternatives, i.e., if the individual benefits from the treatment yi = 1 and if they do not yi = 0. These two outcomes are never observed at the same time for the same individual, as it is impossible to be both exposed and unexposed at the same time. As a result, for a treated individual, Y1 is observed while Y0 is unknown, and vice versa. The value corresponding to the result that would have been achieved if the individual had not been treated is called the “counterfactual” in the econometric evaluation literature Rubin, (1974).

The observed adoption outcome Y can be written as a function of the two potential adoption outcomes Y1 and Y0 and the exposure status as follows:

In the case of our study, where the adoption outcome is a binary variable taking the value 1 if the producer adopts the CSA and CIS technologies or 0 otherwise, then the expected value corresponding to the average adoption outcome of the CSA and CIS technologies boils down to the probability corresponding to the adoption rate measure (proportion of adopters in the population). The various treatment effects can therefore be written as follows:

ATE: Average Treatment Effect on the population, representing the potential adoption rate for the entire population:

ATE1: Average Treatment Effect on the treated sub-population, i.e., the adoption rate among the exposed (those who have been made aware of CSA and CIS technologies):

ATE0: Average Treatment Effect on the untreated sub-population, i.e. the potential adoption rate among the unexposed (those who have not been made aware of CSA and CIS technologies):

If Y0 = 0 the expression of the observed adoption outcome as a function of the potential adoption outcome and exposure status reduces to: y = Ey1.

This expression shows that the observed adoption outcome variable is a combination of the exposure variable and the potential adoption outcome variable, hence the name: Joint Population Exposure and Adoption Rate, better known as Joint Exposure and Adoption :

The average difference between JEA and ATE is called the adoption gap (GAP), which provides information on the demand for the technology. This GAP is given by the following equation:

The difference in mean between ATE and ATE1 is called positive selection bias.

The procedure for estimating the average treatment effect is based on the following equation, which identifies ATE(X)which underlies the conditional independence (CI) hypothesis (Diagne and Demont, 2007):

Where g is a known (non-linear) function of the covariate vector x and the parameter β must be estimated using the method of least squares or maximum likelihood using the observations (yi, xi) concerning the sub-population familiar with CSA and CIS technologies with y as the dependent variable and x the vector of explanatory variables. With an estimated parameter the predicted values are calculated for all observations in the sample in the sample (including observations in the sub-population without access) and ATE, ATE1 and ATE0 are estimated by taking the mean of the predicted values across the whole sample (for ATE) and the respective sub-samples (for ATE1 and ATE0).

The effects of adoption determinants as measured by the marginal effects K of the K-dimensions vector of covariates xgiven a point are estimated as follows:

The hypothesis considered in this research is based on the selection of observables. Exposure to CSA and CIS technologies is a phenomenon partly exogenous to the producer. Indeed, a producer does not choose to be exposed to CSA and CIS technologies, although he may undertake actions (participation in meetings, membership of farmers' organizations, training, etc.) that will facilitate his exposure to CSA and CIS technologies. However, certain unobservable factors mean that exposure is not totally exogenous, which can lead to a bias that may overestimate adoption (Diagne and Demont, 2007). In the study area, the extension of CSA and CIS technologies is channeled through supervisory structures (JOKALANTE, ANCAR, ISRA, DRDR, etc.), so this potential bias can be overlooked. In order to minimize this bias, a stratified random sampling plan by village (clusters) was chosen. All estimations were performed with Stata 15 software, using the adoption command developed by (Diagne and Demont 2007).

3 Results

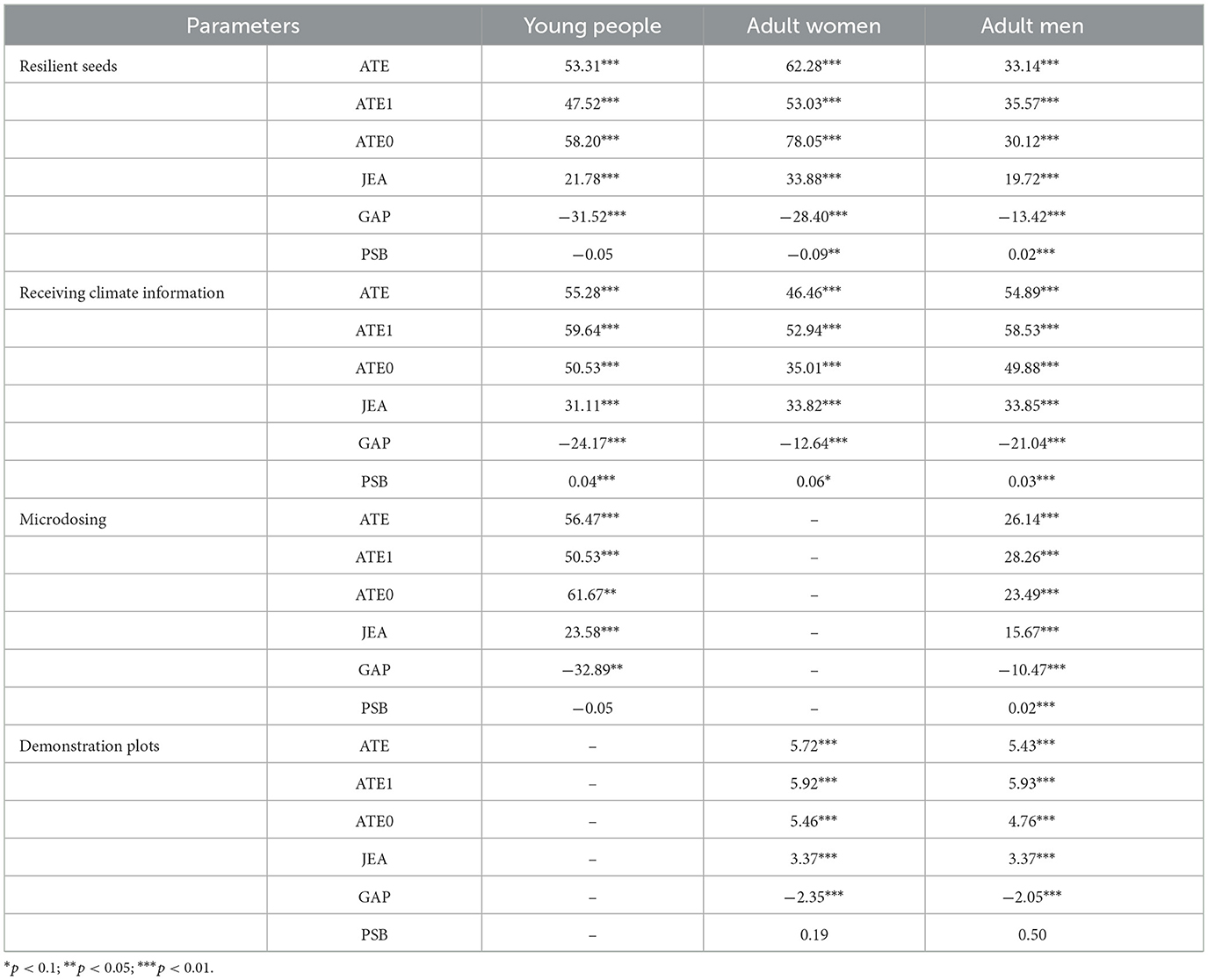

Table 2 presents the adoption rates of the different CSA and CIS technologies across sub-groups.

3.1 Adoption of resilient seeds

The results reveal that the current adoption rate of resilient seeds among youth is 21.8%, with an adoption gap of 31.5%. However, these rates are 33.9% and 28.4%, respectively, among women and 19.7% and 13.4%, respectively, among men. In addition, the results reveal that potential adoption rates (ATE0) in the unexposed sub-population for women and youth are higher than adoption rates in the exposed sub-population. This implies a targeting problem in the dissemination of resilient seeds for women and youth, and that these two groups are likely willing to adopt resilient seeds if they have access to them.

3.2 Use of climate information

With regard to the use of climate information, the current reception rate is higher and similar in among adult women and men, at 33.8% and 33.9% respectively, whereas the information reception gap is widest among young people (24.2%), with a higher potential reception rate (59.6%).

3.3 Adoption of microdosing

For microdosing technology, the adoption rate could reach 56.8% in the youth sub-population, whereas this rate is estimated, at the time of the survey, at 26.1% in the category of men aged over 36. This result implies that young people are more likely to adopt microdosing, with a joint exposure and adoption rate of 23.6%, which is higher than the rate estimated for the male sub-population (15.7%).

3.4 Demonstration plots

For the demonstration plots, the results show an adoption gap of 5.2% with a potential adoption rate of 13.5%.

4 Discussion

Our findings highlight significant adoption gaps across gender and age groups, suggesting that while current interventions are effective, there is additional opportunity to enhance widespread and equitable uptake of CSA and CIS technologies. For example, adoption of resilient seeds is relatively higher among women (33.9%) than men (19.7%) and youth (21.8%), yet both women and youth display substantial adoption gaps, with potential rates that exceed current exposure. This indicates untapped demand among these groups and points to targeting shortcomings in current dissemination strategies.

Additionally, youth show the highest potential adoption of climate information (59.6%) and microdosing (56.8%), suggesting that they are especially receptive to innovations when provided with access and support. Prior research in other low and middle income contexts has shown that young producers are generally more willing to take risks when adopting technological innovations (e.g., Chandio and Yuansheng, (2018) and often benefit from higher levels of education, which may further increase their openness to new practices compared to adult counterparts (e.g., Dontsop-Nguezet et al., 2011).

These findings reinforce the need to move beyond treating farmers as a homogenous group. Gender and age influence adoption trajectories differently: women tend to adopt certain practices at higher rates, yet face systemic barriers in access to land, inputs, and information; youth are more open to risk and innovation, yet often lack resources and targeted extension support. By contrast, adult men currently exhibit higher levels of access and adoption in some technologies, but with lower potential adoption rates, suggesting a ceiling effect.

Patterns observed in Senegal align with studies from other parts of Africa. In Benin, (Obossou et al. 2023) found that men were more likely to adopt soil and water conservation practices and improved livestock management systems, while women favored improved crop production systems. In Kenya, Ngigi and Muange (2022) reported gender gaps in access to CIS, with men better connected to early warning systems and adaptation advisory services, while women had greater access to short-term weather forecasts. These regional parallels suggest that heterogeneity in adoption is a consistent feature of CSA and CIS interventions and that addressing these disparities requires deliberate design.

In addition, in the Senegalize context, household members often farm on the same plots, with gender and age-related divisions of agricultural tasks, complicating individual-level adoption. This underscores the importance of embedding CSA and CIS dissemination within broader social norms and community dynamics. Promoting the rights and agency of men, women, and youth collectively can foster environments where adoption is shared rather than siloed, and where innovations are sustained at the household and community level.

Existing literature also underscores the multifaceted determinants of adoption. Obossou et al. (2023) highlight gender, age, farm size, land ownership, access to labor, and exposure to projects as key factors influencing uptake. In Kenya, Tesfaye et al. (2023) demonstrate that the establishment of climate-smart villages not only facilitated technology adoption but also advanced gender equality by explicitly addressing women's constraints. Together, these findings support Bernier et al. (2015), who emphasize that CSA and CIS technologies lose effectiveness when farmers are treated as a uniform group, rather than as diverse actors shaped by social and institutional contexts.

5 Conclusion

This study examined heterogeneity in the adoption of CSA and CIS technologies among youth, men, and women across three regions of Senegal. Two key lessons emerge for agricultural technology dissemination policy. First, the presence of significant adoption gaps indicates that not all populations have been adequately exposed to CSA and CIS technologies, revealing a non-exposure bias and underscoring the need for wider dissemination. Second, our results highlight targeting shortcomings in reaching women and youth, particularly with respect to climate-resilient seeds and microdosing techniques. Developing more precise identification and outreach strategies for these sub-populations is therefore critical to maximize adoption potential and ensure equitable benefits.

These findings suggest that future interventions should not only expand coverage but also tailor dissemination to account for gender- and age-related differences in adoption capacity. Doing so will strengthen the effectiveness of CSA and CIS initiatives while promoting more inclusive climate adaptation strategies in Senegal.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent from the participants/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ONW: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BWB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AN-DY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. EAS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TMG: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JEJ: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FMA: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KM: Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We acknowledged the funding by AICCRA (Accelerating CGIAR Climate Impact Research in Africa) by the World Bank (Project ID 173398).

Acknowledgments

The study was carried out as part of the AICCRA project. We thank all AICCRA partners (ISRA, ANCAR, CEERAS, AfricaRice, DRDR) for fruitful discussions and the interviewers for proactive collaboration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author.

Footnotes

1. ^According to ANSD (2023a),b,c, 69% of households in the Louga region are involved solely in rain-fed agriculture.

2. ^The microdosing technique consists of applying small quantities of appropriate mineral fertilizers to the seed holes of a crop.

References

ANSD (2023a). Situation économique et sociale de la région de Kaffrine. Available online at: www.ansd.sn/sites/default/files/2024-01/SES-Kaffrine_2020-2021-rev.pdf (Accessed November 23, 2023).

ANSD (2023b). Situation économique et sociale de la région de Thies. Available online at: www.ansd.sn/ses-regionales?field_year_value=2019&field_regions_ses_target_id=9 (Accessed November 23, 2023).

ANSD (2023c). Situation économique et sociale de la région de Louga. Available online at: www.ansd.sn/ses-regionales?field_year_value=2019&field_regions_ses_target_id=15 (Accessed November 23, 2023).

Ariom, T., Dimon, E., Nambeye, E., Diouf, N., Adelusi, O., and Boudalia, S. (2022). Climate-smart agriculture in African countries: a review of strategies and impacts on smallholder farmers. Sustainability 14:11370. doi: 10.3390/su141811370

Arslan, A., McCarthy, N., Lipper, L., Asfaw, S., Cattaneo, A., and Kokwe, M. (2015). Climate smart agriculture? Assessing the adaptation implications in Zambia. J. Agric. Econ. 66, 753–780. doi: 10.1111/1477-9552.12107

Barasa, P., Botai, C., Botai, J., and Mabhaudhi, T. (2021). A review of climate-smart agriculture research and applications in africa. Agronomy 11:1255. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11061255

Bernier, Q., Meinzen-Dick R, S., Kristjanson P, M., Haglund, E., Kovarik, C., Bryan, E., et al. (2015). Gender and Institutional Aspects of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices: Evidence from Kenya. CCAFS Working Paper. CCAFSWorking Paper. Copenhagen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

Chandio, A. A., and Yuansheng, J. (2018). Determinants of adoption of improved rice varieties in Northern Sindh, Pakistan. Rice Sci. 25, 103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2017.10.003

DAPSA (2020). Rapport de la phase 1 de l'Enquête Agricole Annuelle (EAA) 2019-2020. Rapport Final EAA 2019-2020 | Direction de l'Analyse, de la Prévision et des Statistiques Agricoles. Dakar: DAPSA.

Derenoncourt, E., and Jaquet, S. (2022). AICCRA-Senegal Gender-Smart Accelerator Grant concept note. 15 p. AICCRA-Senegal Gender-Smart Accelerator Grant Concept Note. Nairobi: CGIAR GENDER Impact Platform.

Diagne, A., and Demont, M. (2007). Taking a new look at empirecal models of adoption: average treatment effect estimation of adoption rate and its determinants. Agric. Econ. 37, 201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00266.x

Dontsop-Nguezet, P. M., Diagne, A., Okoruwa, V. O., and Ojehomon, V. (2011). Impact of improved rice technology (NERICA varieties) on income and poverty among rice farming household in nigeria: a local average treatment effect (LATE) approach. Quart. J. Int. Agric. 50, 267–291. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.155535

EM2030 (2020). EM2030. Un ≪ retour à la normale ≫ ne suffit pas : l'Indice du Genre dans les ODD 2022 d'EM2030. Equal Measures 2030. Woking (2022). Available online at: https://www.equalmeasures2030.org

GIEC (2021). Résumé à l'intention des décideurs. In: Changement climatique 2021: les bases scientifiques physiques. Contribution du Groupe de travail I au sixième Rapport d'évaluation du Groupe d'experts intergouvernemental sur l'évolution du climat [publié sous la direction de Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, et B. Zhou]. Suisse: Cambridge University Press. IPCC-AR6_WGI_SPM_Stand_Alone_WMO_FR_06.indd.

Nantongo, B., Joseph, S., Ngom, A., Dieng, B., Diouf, N., Diouf, J., et al. (2021). Evaluating the Impact of Weather and Climate Information Utilization on Adoption of Climate-Smart Technologies Among Smallholder Farmers in Tambacounda and Kolda Regions (Senegal). JEES. doi: 10.7176/JEES/11-2-05

Nelson, S., and Huyer, S. (2016). A Gender-Responsive Approach to Climate Smart Agriculture. Evidence and Guidance to Practitioners. Practice Brief Climate smart Agriculture. Nairobi: Global Alliance for Climate Smart Agriculture (GACSA).

Ngigi, M. W., and Muange, E. N. (2022). Access to climate information services and climate-smart agriculture in Kenya: a gender-based analysis. Clim. Change 174:2022. doi: 10.1007/s10584-022-03445-5

Obossou, E. A. R., Chah, J. M., Anugwa, I. Q., and Reyes-Garcia, V. (2023). Gender dimensions in the adoption of climate-smart agriculture technologies in response to climate change extremes in Benin. Reg. Environ. Change 23:93. doi: 10.1007/s10113-023-02085-4

Ouédraogo, M., Houessionon, P., Zougmoré, R., and Partey, S. (2019). Uptake of climate-smart agricultural technologies and practices: actual and potential adoption rates in the climate-smart village site of Mali. Sustainability 11:4710. doi: 10.3390/su11174710

PSE (2014). Plan Sénégal Emergent. Dakar: PSE| Ministère de l'Economie, du Plan et de la Coopération.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: Free Press. A division of Simon and Shuster, Inc.

Rubin, D. B. (1974). Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 66, 688–701. doi: 10.1037/h0037350

Tesfaye, A., Radeny, M., Ogada M, J., Recha J, W., Ambaw, G., Chanana, N., et al. (2023). Gender empowerment and parity in East Africa: evidence from climate-smart agriculture in Ethiopia and Kenya. Clim. Dev. 15, 768–778. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2022.2154124

UN Women Africa (2019). The Gender Gap in Agricultural Productivity in sub-Saharan Africa: Causes, Costs and Solutions. Policy Brief No. 11. East and Southern Africa Regional Office.

UNESCO (2020). Rapport mondial de suivi sur l'éducation 2020 : Inclusion et éducation : Tous, sans exception. Place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France. CC-BY-SA 3.0 (IGO). Available online at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/

Xie, H., and Ringler, C. (2015). Investir dans l'irrigation pour assurer la sécurité alimentaire dans le futur – perspective 2050 au Sénégal. 2 p; IFFPRI, Country Brief. 130063. pdf (ifpri.org). Nairobi.

Zougmoré, R., Partey, S., Totin, E., Ouédraogo, M., Thornton, P., Karbo, N., et al. (2019). Science-policy interfaces for sustainable climate-smart agriculture uptake: lessons learnt from national science-policy dialogue platforms in West Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sust. 17, 367–382. doi: 10.1080/14735903.2019.1670934

Keywords: climate information services, climate-smart agricultural technology, farmers, adoption, Senegal, gender

Citation: Worou ON, Moore M, Basse BW, Yessoufou A-D, Sarr EA, Gondwe TM, Joseph JE, Akinseye FM and Mbow K (2025) Exploring disparities in the diffusion and adoption of climate-smart agricultural and climate information system technologies in Senegal. Front. Environ. Econ. 4:1524321. doi: 10.3389/frevc.2025.1524321

Received: 13 November 2024; Accepted: 23 October 2025;

Published: 20 November 2025.

Edited by:

Davide Bazzana, University of Brescia, ItalyReviewed by:

Selene Righi, University of Pisa, ItalyMori W. Gouroubera, Alliance Bioversity International and CIAT, Senegal

Copyright © 2025 Worou, Moore, Basse, Yessoufou, Sarr, Gondwe, Joseph, Akinseye and Mbow. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Omonlola Nadine Worou, bi53b3JvdUBjZ2lhci5vcmc=

Omonlola Nadine Worou

Omonlola Nadine Worou Maya Moore

Maya Moore Blaise Waly Basse

Blaise Waly Basse Adjani Nourou-Dine Yessoufou

Adjani Nourou-Dine Yessoufou Etienne Aliouse Sarr1

Etienne Aliouse Sarr1 Therese Mwatitha Gondwe

Therese Mwatitha Gondwe Florounsho M. Akinseye

Florounsho M. Akinseye Khalifa Mbow

Khalifa Mbow