Research Metrics for Health Science Schools: A Conceptual Exploration and Proposal

- 1Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Center on Commercial Determinants of Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Department of Global Health, Center on Commercial Determinants of Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

Research is a critical component of the public health enterprise, and a key component of universities and schools of public health and medicine. To satisfy varying levels of stakeholders in the field of public health research, accurately measuring the return on investment (ROI) is important; unfortunately, there is no approach or set of defined metrics that are universally accepted for such assessment. We propose a research metrics framework to address this gap in higher education. After a selected review of existing frameworks, we identified seven elements of the generic research lifecycle (five internal to an institution and two external). A systems approach was then used to broadly define four parts of each element: inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes (or impacts). Inputs include variables necessary to execute research activities such as human capital and finances. Processes are the pathways of measurement to track research performance through all phases of a study. Outputs entail immediate products from research; and outcomes/impacts demonstrate the contribution research makes within and beyond an institution. This framework enables the tracking and measurement of research investments to outcomes. We acknowledge some of the challenges in applying this framework including the lack of standardization in research metrics, disagreement on defining impact among stakeholders, and limitations in resources for implementing the framework and collecting relevant data. However, we suggest that this proposed framework is a systematic way to raise awareness about the role of research and standardize the measurement of ROI across health science schools and universities.

Accurately measuring the return on investment (ROI) is a critical yet often overlooked tenant of public health research and practice. Despite its ability to inform future investments, maximize benefits, and improve interventions, the field of public health lacks a standardized framework to measure such returns. In this paper, we propose a framework that can help higher educational research institutions measure the performance of various research projects. We hope that by utilizing a common framework, health science schools and universities can maximize the value of their research and their impact on the field of public health.

Introduction

Public health research contributes immensely to scientific breakthroughs, healthier communities, innovations, sound policies, and economic growth (Gostin et al., 2009). Public health research has a diverse set of stakeholders at varying levels including funders, policymakers, researchers, participants, and members of the community; and many of these stakeholders have an interest in quantifying the return on investment (ROI) for research (Cruz Rivera et al., 2017). However, despite some existing models, there is no universally accepted set of metrics to assess ROI for public health research; despite a growing demand to identify and develop standards to effectively measure and communicate research-related progress and success (Banzi et al., 2011). In addition, challenges such as inconsistent definitions of outcomes, time lapse between research and impact, issues in establishing attribution, and accommodating stakeholder perceptions make this goal complex (Graham et al., 2018). A universally accepted approach however, would provide a system to measure social, economic, and environmental benefits of research.

Research systems exist at multiple levels—institutional, state, national, and international—and some approaches to measuring them have been published (Hanney et al., 2020). Research measurement systems need to evolve and strengthen by including new dimensions and measures for each level (David and Joseph, 2014). Academic institutions often have their own systems tracking selected metrics within the context of their research ecosystem needs; however, they are often ad-hoc, limited in scope and informal in nature (Aguinis et al., 2020). Institutionalizing consistent and universal standards, such as definitions, data collection, analysis and reporting, would help improve practices in research tracking and measurement. In addition, having clear research strategic plans and goals would also optimize the selection and implementation of appropriate research metrics (Hanney et al., 2020).

Useful metrics provide valuable insights on the research process and enables benchmarking based on standard definitions for meaningful comparisons (University of Birmingham, 2021). Building a research measurement system and tools can enable academic institutions collect and provide research metrics on a consistent and reliable basis; and enables multidimensional ways of assessing the value and ROI of research. And an effective impact assessment framework can demonstrate how positive change resulting from research investments improves prioritization, decision-making, management of stakeholder expectations and promotes accountability and transparency at an institution.

The overall goal of this paper is to explore research measurement frameworks that are suitable for an academic school level application. Our objective was to propose a research measurement framework and explore its applicability in an academic setting in the United States.

The proposed framework focuses on research metrics within an academic institutional research ecosystem; to help guide research assessment and planning. We hope that this paper will lead to further application and testing of our proposed approach in other settings in the US and globally.

Selected Review of Existing Frameworks

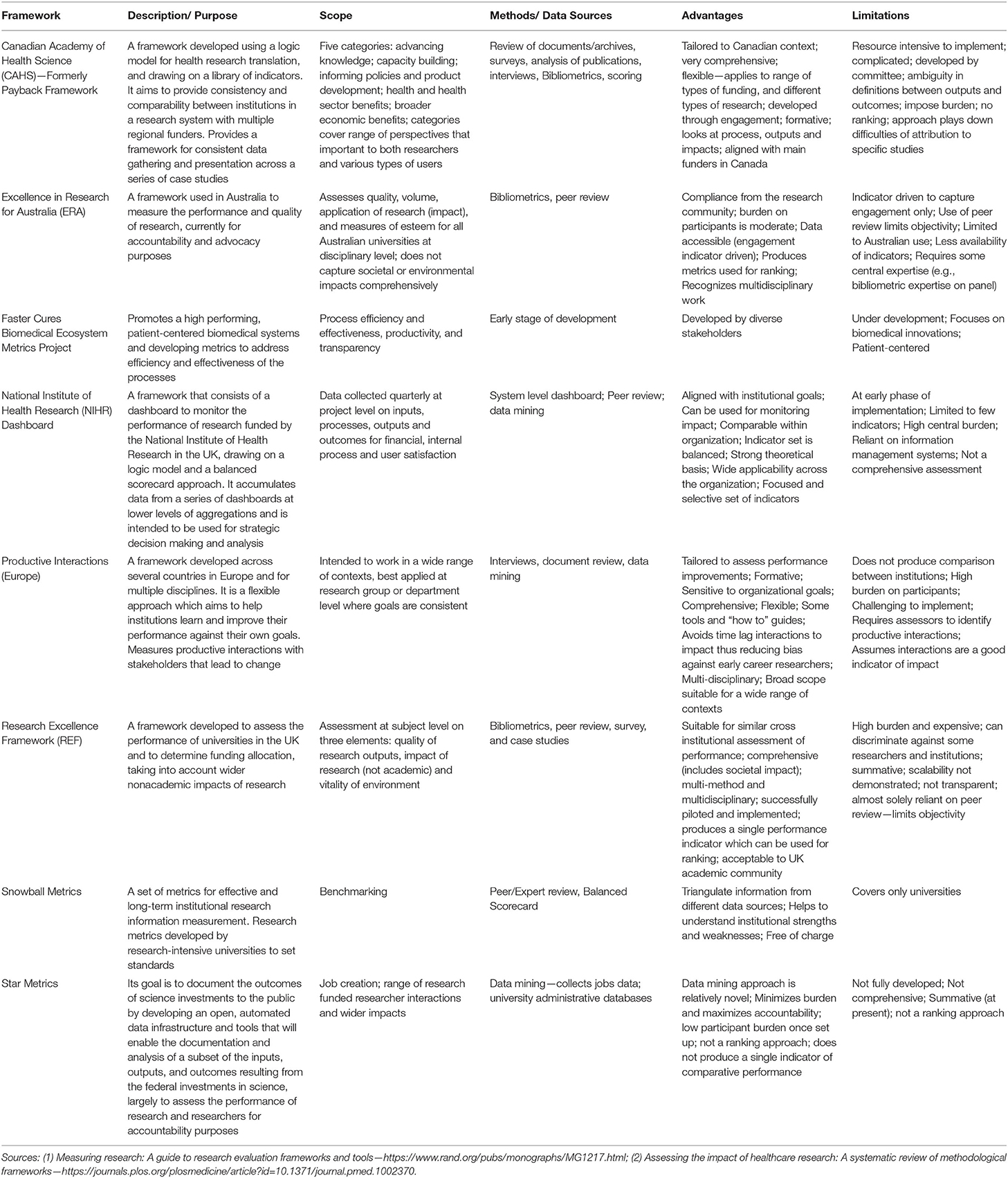

A number of research assessment frameworks have been developed and implemented in specific institutions or countries, over the past years (Guthrie et al., 2013). However, there are no guidelines or consensus either around one universal framework or even around the protocol to develop a methodological framework; hence reviewing some commonly used approaches was essential (Cruz Rivera et al., 2017). Therefore, we reviewed frameworks that were implemented at different scale to address research metrics and measurement issues (Table 1). All reviewed frameworks have been applied in specific setting or location; are not universally acclaimed; and none have been recommended for academic institutions. In addition, many suffer from other limitations such as cost, complexity, data collection burden, underdevelopment of definitions, and issues of scale (Table 1).

For example, the Research Excellence Framework is useful but focused on assessing the performance of universities to determine funding allocation; while the one used by the British National Institute of Health Research is complex and detailed with a high data collection burden (Table 1). The Canadian Academy of Health Science Framework provides consistency and comparability between institutions in a research system, consistent data gathering and presentation but is resource intensive, very complicated and has fewer standardized definitions. The Productive Interactions Framework, used widely in Europe, is broad, multi-disciplinary, and focused on individual institution's research goals, but does not allow for comparisons between institutions. The Snowball Metrics was actually developed by research-intensive universities for the primary goal of institutional benchmarking (and not internal assessments); it also utilizes fewer data sources and does not cover all impact metrics across needed domains. Further examples detailing the strengths and limitations of each framework we analyzed can be found in Table 1.

These frameworks indicate that utilizing a combination of qualitative and quantitative indicators often produces better result for research ROI assessments (Table 1). Moreover, a single metric may not tell the whole story about the outcome or impact of research, hence developing a practice of employing multiple metrics is beneficial. Each metric should be regularly evaluated for relevance to ensure alignment with organizational goals and changing research ecosystems and processes. While adopting a comprehensive approach to include all relevant metrics in an ecosystem is useful, it is also important to manage the data collection and reporting burden on the administrative staff and research community. It is also crucial to establish credible, acceptable, and customizable research metrics for an institution that take into account the views of stakeholders and interest groups. These lessons have informed the development of the proposed research measurement framework below.

Proposed Research Metrics Conceptual Framework

Overview

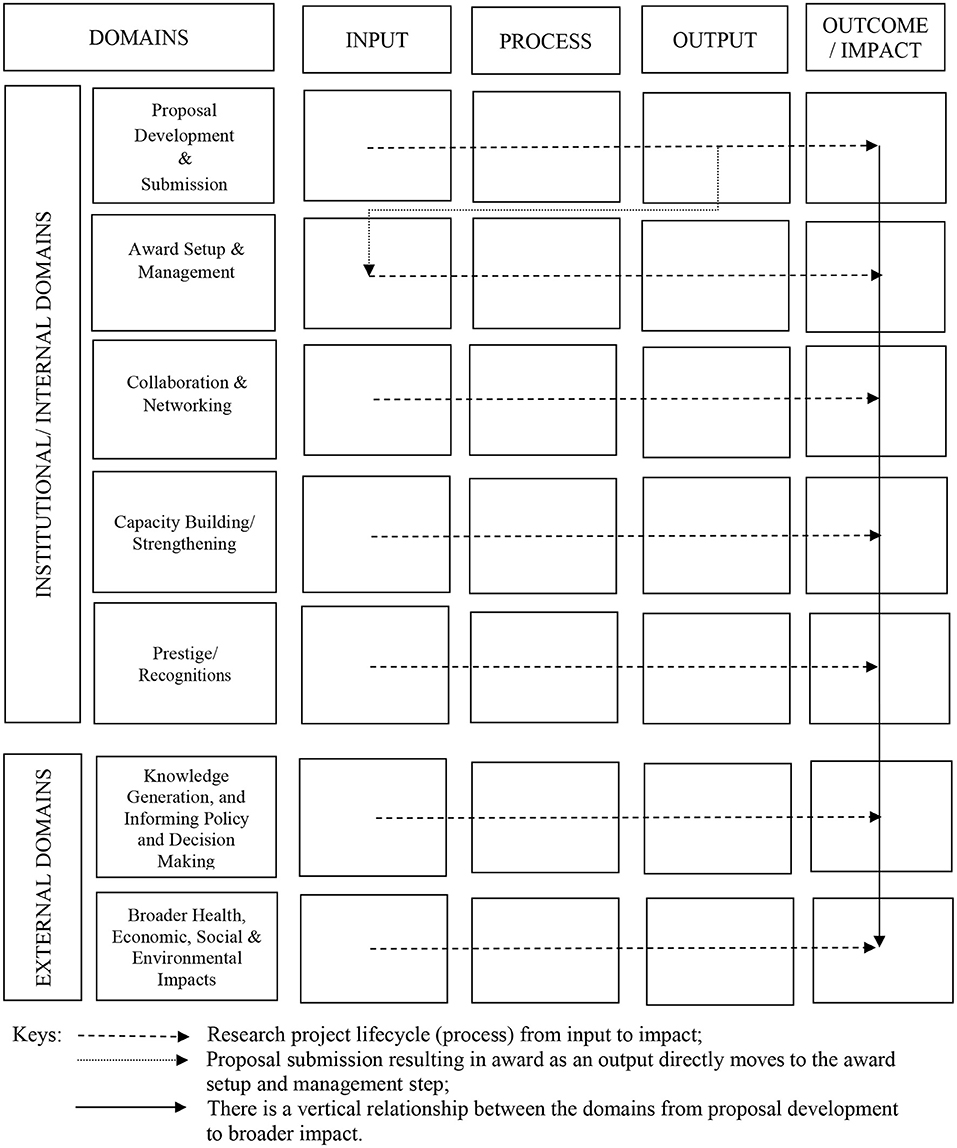

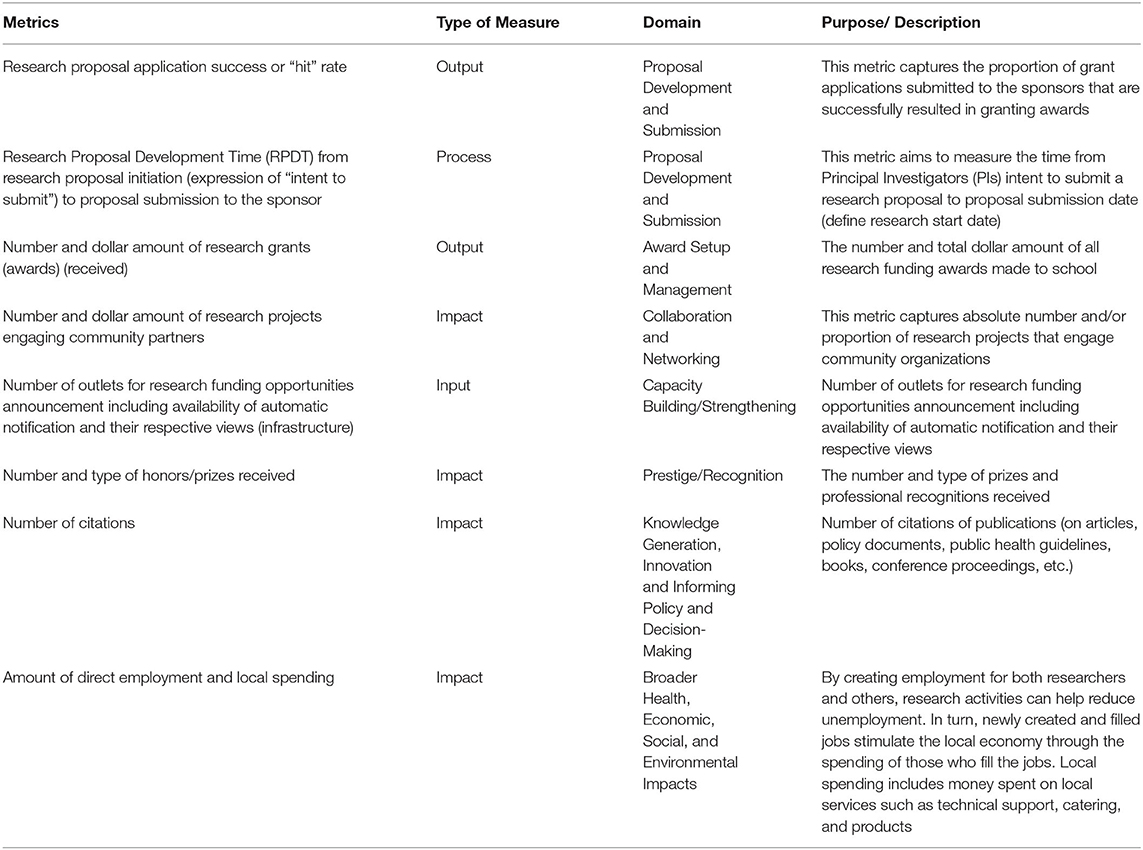

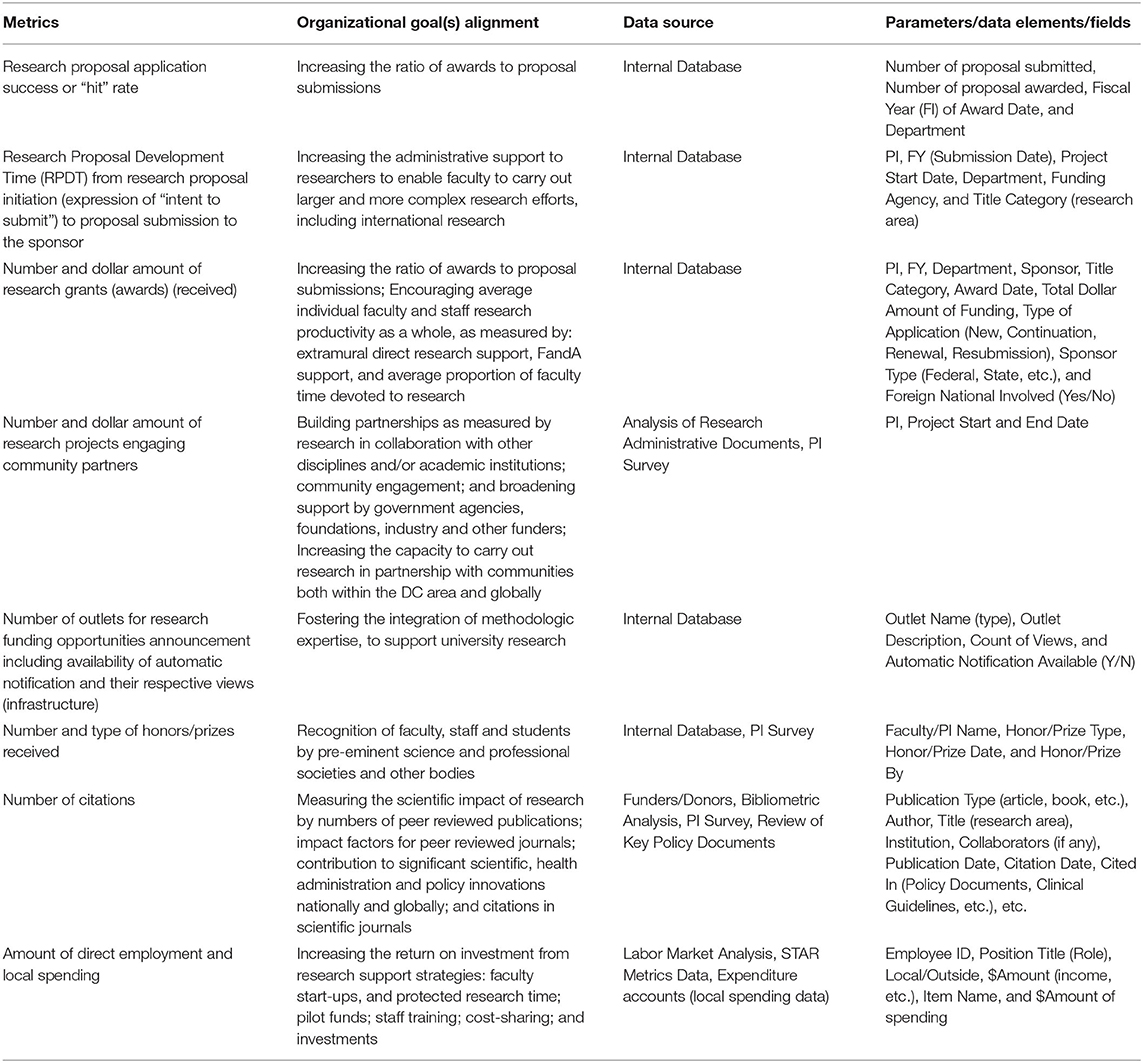

Our proposed research metrics framework uses a systems approach as one axes of measurement: Input, Process, Output, and Outcome/impact (Figure 1). On the other axes are seven domains that encompass the research lifecycle from proposal development to outcomes in society; and offer both an intra- and extra-institutional components. A portfolio of institutional research performance metrics corresponding to each domain and system category can be developed within each cell (Table 2). Each indicator can be selected to have some desired characteristics of a realistic metric, such as validity, credibility, responsiveness, reliability and availability (David and Joseph, 2014).

Table 2. Example research metrics for a school of health science (e.g., medicine, public health, and biomedical Science).

Axis 1: Research Lifecycle Categories

Metrics for each of the four system stages were identified through a research logic model of: (1) idea inception, (2) funding, to (3) wider benefit as follows (examples in Table 3).

Input Metrics

Input metrics include human capital (faculty, staff, and students), finance (funding), time, infrastructure, facilities and partnerships necessary to execute research activities and produce outputs. The underlying assumption is that creating a well-equipped research environment would result in better outputs and outcomes. The optimal research input metrics demonstrate quantitative and qualitative institutional capacity measures to conduct research and produce desired outputs. It is important for an organization to identify and measure inputs to inform research activities and set organizational targets. However, there are challenges in quantifying the level of human, financial and material resources needed for investment to bring about changes within an institution and wider society. The number, composition and experience of research teams (including faculty, staff, and students) and budget line items allocated for technical and administrative costs are examples of input metrics.

Process Metrics

Process metrics are used to track and evaluate research performance through all phases of a project lifecycle. They serve as a measure of organizational excellence in attaining the outputs produced by way of applying specific resource inputs together. Defining and implementing appropriate research processes creates a strong bridge to effectively transform research inputs into desired outputs. Process metrics may include efficiency, effectiveness, capacity, productivity, benchmarking, and research development time based measures.

Outputs

Outputs are products directed to beneficiaries or stakeholders that ultimately either are of valuable milestones or bring about desired changes. Outputs can be measured in a wide variety of ways such as the number of publications in peer-reviewed journals, number of patents acquired, and amount of research expenditures. They are generally measured by the volume and quality of immediate research products that a researcher, department, or institution, produces within a specified time frame.

Outcomes or Impacts

Outcomes or impacts refers to demonstrable contributions that research makes at the societal level to the economy, culture, public policy, services, health, environment, or quality of life, beyond simply adding to academia. Some metrics such as number of citations, downloads, and mentions in social media can be measured in the short-term; while others such as start-ups, revenue from commercialization, broader health, and economic impacts of research are captured through long-term tracking.

Axis 2: Research Lifecycle Domains

Each metric has been classified into a particular type of domain where all metrics share common characteristics that also facilitate data collection, analysis, and reporting (Figure 1). The domains are also broadly divided into five institutional/internal and two external/impact ones to represent the most important metrics that measure institutional performances vs. larger impacts for public health. Each domain is further descried below.

Proposal Development and Submission

Metrics in this category measure research inputs, processes, and outputs from proposal development, as well as individual and institutional metrics resulting from relevant processes. Examples include the number of eligible faculty participating in research development, time interval from expression of interest/funding opportunity to submission by the principal investigator (PI) to the funding agency (sponsor), and number of proposals developed and successfully submitted to funding agencies. These are generally internal/institutional pre-award performance metrics.

Award Setup and Management

Following receipt of grant funds after a submitted proposal is awarded, all the post-award research activities to the point of award closeout are captured within this domain. Examples include the number and aggregate dollar amount of awards received and the number of active projects. These are generally internal/institutional post-award performance metrics.

Collaboration and Networking

These metrics assess collaboration and networking with internal and external partners. They encompass diverse approaches to improving the culture of engagement with individuals, domestic and international organizations, communities, industry and other research partners. The metrics can measure the strength of inter- and multi-disciplinary research and the degree to which the research engages other stakeholders. Connections with various parties can help manage successful research outcomes and may include work with funders, governments, academic institutions, and industry partners. Higher numbers of interactions among various parties can be indicative of impactful production of research outputs. Collaborations (national or international) and networks can be established at the institutional level or by an individual researcher affiliated with the institution.

Capacity Building/Strengthening

This is a process of maximizing human, financial, material, and other resources to carryout activities effectively to consistently produce better results in achieving visions and goals of an organization. These metrics may include research infrastructure development, trainings, fellowship, participation of post-doctoral and graduate students (Masters and PhD), and academic career advancements. Capacity building is integral to any research activity, from the individual researcher, to management, and leadership staff. Examples of key infrastructure include the availability of automated systems for applications, systems for funding opportunity notifications and the number of research faculty and staff that are hired post-training.

Prestige/Recognition

These are measures of reputation attained by researchers (e.g., faculty, staff, students, and alumni) because of quality research efforts, such as awards and professional recognition.

External Impact Domains

Knowledge Generation, Innovation, and Informing Policy and Decision-Making

The generation and use of knowledge can have a significant impact on communities, organizations, and individuals. The impact of research also extends to regulators, legislators and policymakers as it helps them develop guidelines, resolve public health issues, and adjust future strategic plans accordingly. Example of indicators in this domain include number of article and patent citations, number of editorships in high-profile journals, and number of appoints to policy groups.

Broader Health, Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts

These metrics include the wider and longer-term benefits to society, depending on the type of research conducted. Such benefits include innovations, practices, services, and many other holistic improvements attributed to a number of contributors. These metrics are usually difficult to quantify and attribute to a particular organization or entity but include things like declines in disease prevalence; improvements in quality of care and service delivery; reduced unemployment; benefits from commercialization of research products; and advances in community awareness in healthcare utilization.

Standardizing Research Metrics

The use of standard terminology and definitions is integral to research performance and impact measurement systems. Defined terms provide clarity and consistency in communicating outcomes and helps improve the standardization process. In research metrics, there has been a lack of shared conceptual clarity and inconsistent use of definitions and terms, which has in turn created confusion, duplication, and inefficiencies for research stakeholders (Remme et al., 2010). Developing uniformity in the definition of terms, data and metrics is also critical for conducting balanced comparisons among peer institutions.

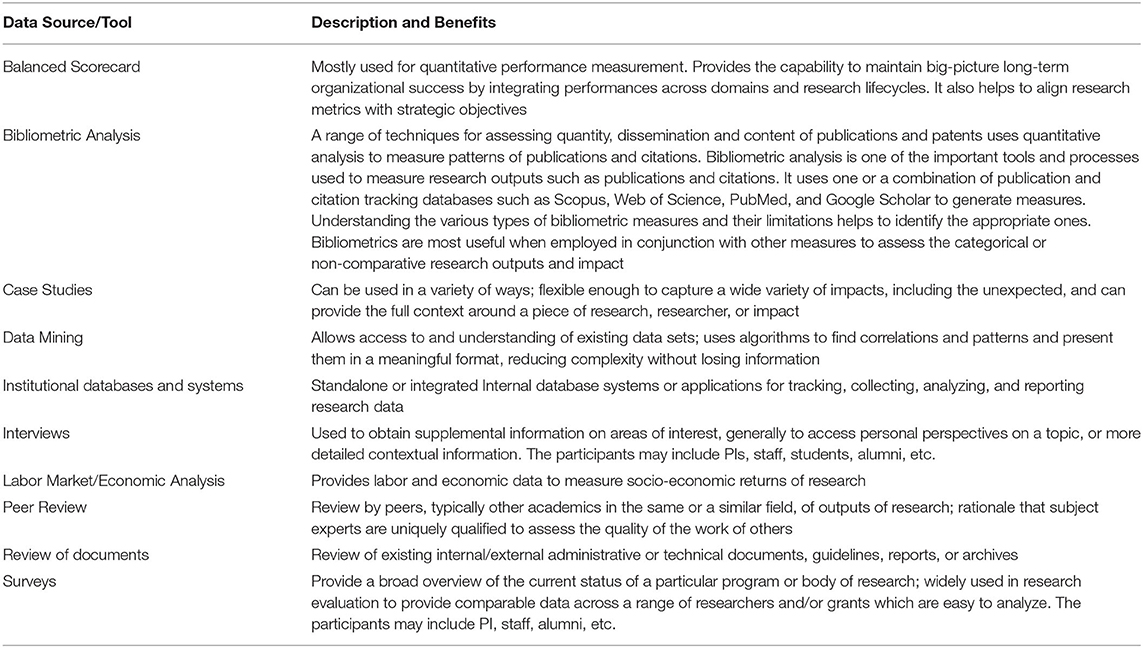

Each metric draws on data collected through one or more data sources that can be used individually or in combination; and the proposed framework allows all appropriate methods of data collection, aggregation, and analysis across research proposals, awards, projects, publications, and institutions. Table 4 presents examples of most common data sources and research data extraction methods across institutional and external impact domains; for example, research publications as outputs are often extracted from bibliometric analysis. Integration and interoperability of systems within an institution may be critical for reliably tracking and measuring research data across various systems and data sources.

Every research activity or process has some data associated with it; but not all of this data is measured or recorded even though it may be necessary for relevant research metrics. Research data points and fields needed in each research lifecycle domain should be identified and clearly defined prior to the selection of relevant metrics. The unit of analysis and reporting is largely determined by the intended use of data; for example, some rates may be reported per PI, while others per proposal or per grant. These are some of the key decisions that institutional leadership will need to take prior to implementation of the proposed framework.

Discussion

An internal assessment of an institutional research ecosystem can begin with discussions amongst leadership, faculty, staff, and research administrators on defining the need for research metrics and its implementation prioritized according to resource availability. Research metrics ought to align with an organization's strategic goals. The proposed conceptual framework above serves as a foundational roadmap that will help initiate discussions among an institutions' research community regarding metrics and measurement systems that fulfill local needs. The collection of standardized metrics will enhance uniformity and reliability; and improve research tracking and measurement systems across academic institutions. This framework hopes to initiate such dialogue and serve as a potential tool to better understand research and guide investment decisions for the research community and stakeholders.

Implementing a research metrics framework contributes toward quantifying the ROI on research both internally within an institution and externally in society. Illustrating the value of research is crucial in sustaining donor and taxpayer support, informing policies, and highlighting broader societal benefits of research (Guthrie et al., 2017). The use of value measures, with tangible and intangible benefits, can support advocacy for investments and give decision-makers the opportunity to draw on evidence to inform advocacy and prioritization of action (Hunter et al., 2018). If implemented successfully, a research metrics framework can also help evaluate the performance of a research system against baseline measures, and provide feedback to guide evidenced-based practice.

There are factors that challenge the systematic tracking and measurement of research performance and impact in academic institutions. For instance, lack of common understanding and agreement among groups of diverse stakeholders (with varying interests on research metrics and impact assessment) can create problems in measurement. Additionally, the absence of a universally accepted standard research measurement system and set of metrics that appropriately assess outputs and impacts makes it more difficult (Boaz and Hanney, 2020; Hanney et al., 2020). Further, choosing a comprehensive approach may create a burden on data collection and tracking. Even with the selected relevant metrics, it is not uncommon to face difficulties in ensuring data availability and quality within institutions.

Limitations in human, financial and material resources and infrastructure is a common factor hindering the generation, development, integration and automation of ideal research performance and impact measurement systems (Boaz and Hanney, 2020). As is true for other research measurement systems, impact measurement is a challenge because it is hard to attribute (or accurately quantify) the contribution of an institution's research performance to a specific group or factors. For some research, relatively longer periods of time may be necessary to observe and produce impact, hence, making it challenging to track and measure (Bornmann, 2017). The most popular bibliometric databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar do not capture the entirety of research outputs and impacts. Benchmarking and ranking metrics also require peer institutions to have similar metrics for sensible comparisons.

Integrating systems is vital to track and measure relevant metrics in each part of the research lifecycle and minimizes the reliance on one measure. This framework proposes a comprehensive approach to interrelate the input, process, output and outcome/impact metrics to have a broader picture of research works. The framework tries to triangulate information from various data sources not relying on a few measures but a combination of metrics across the domains and research lifecycle.

The benefit of this conceptual framework is that it tries to adopt the strengths of existing metrics and address the gaps observed for current frameworks (as assessed in Table 1). It recommends integration of appropriate data sources and accommodates relevant comprehensive research metrics that can be applied across institutions with less burden. The purpose of this framework is to have comprehensive research metrics that can be used across health science institutions with less cost, complexity, data collection burden, inconsistency of definitions, and issues of scale as compared to existing frameworks. Moreover, the use of a research lifecycle approach to classifying research metrics employed by this framework provides a distinctive approach to measuring ROI.

This framework also proposes a systematic approach to include relevant research metrics and connect input, process, output, and impact for efficient tracking and measuring of research. The most popular frameworks reviewed in this paper have several limitations in scope, scale, standards, inclusion of relevant metrics, and laying out clear processes of research lifecycle. The practical implementation of the proposed framework within and across organizations can be realized overtime to help with key decisions including allocation of resources. This paper helps conceptualize and establish a broader understanding of such systematic research tracking and measurement at different levels with more efficiency to quantify ROI of research investments across the research lifecycle—to our knowledge for the first time.

Finally, this framework incorporates approaches such as comprehensiveness, standardization, integration, research lifecycle classification, and consistency in concepts to help in the advancement of research measurement especially now when the field is still evolving and there is no single approach that is universally accepted. To reduce the burden of implementation and to enhance successful operationalization, a gradual scale up and close collaboration with research and administrative leadership within institutions and externally with peer institutions are recommended as this is tested over time.

This proposal is at the conceptual stage that needs to be tested at various levels and replicated across various institutions. The proposed framework can be piloted within the context of a particular institution from small to large scale; and the availability of resources can determine the use of such an integrated research systems to optimize effective testing and implementation. The research community can further internalize this concept, collaborate and test this framework within specific settings in the future and generate sufficient data for better application.

Overall, stakeholder interest and demand for the evidence-based evaluation of research is growing locally and internationally; most appear to be committed to better understanding and measuring research output and impact (Boaz and Hanney, 2020). Advancements in technology and data mining techniques have made tracking, extraction, analysis and reporting (as well as data availability, accessibility, and quality), more efficient and effective. Research-intensive universities and those aspiring to become one ought to promote standard tracking and measurement of research output and outcomes. Although evolving gradually, efforts are being made by a number of governmental and non-governmental institutions to develop and institutionalize frameworks that systematically measure research productivity and impact (Hanney et al., 2020). We join that movement and hope our proposed framework will stimulate a global dialogue on the value and consistency of such measures across health science schools and universities.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the Office of Research Excellence, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aguinis, H., Cummings, C., Ramani, R. S., and Cummings, T. G. (2020). “An A is an A”: the new bottom line for valuing academic research. AMP 34, 135–154. doi: 10.5465/amp.2017.0193

Banzi, R., Moja, L., Pistotti, V., Facchini, A., and Liberati, A. (2011). Conceptual frameworks and empirical approaches used to assess the impact of health research: an overview of reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 9:26. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-26

Boaz, A., and Hanney, S. (2020). The Role of the Research Assessment in Strengthening Research and Health Systems. Impact of Social Sciences Blog. Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/09/08/the-role-of-the-research-assessment-in-strengthening-research-and-health-systems/ (accessed February 14, 2020).

Bornmann, L. (2017). Measuring impact in research evaluations: a thorough discussion of methods for, effects of and problems with impact measurements. High. Educ. 73, 775–787. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-9995-x

Cruz Rivera, S., Kyte, D. G., Aiyegbusi, O. L., Keeley, T. J., and Calvert, M. J. (2017). Assessing the impact of healthcare research: a systematic review of methodological frameworks. PLoS Med. 14:e1002370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002370

David, R., and Joseph, J. (2014). Study on performance measurement systems- measures and metrics. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 4:9.

Gostin, L. O., Levit, L. A., and Nass, S. J. (2009). The Value, Importance, and Oversight of Health Research. Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Graham, K. E. R., Langlois-Klassen, D., Adam, S. A. M., Chan, L., and Chorzempa, H. L. (2018). Assessing health research and innovation impact: evolution of a framework and tools in Alberta, Canada. Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 3:25. doi: 10.3389/frma.2018.00025

Guthrie, S., Krapels, J., Adams, A., Alberti, P., Bonham, A., Garrod, B., et al. (2017). Assessing and communicating the value of biomedical research: results from a pilot study. Acad. Med. 92, 1456–1463. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001769

Guthrie, S., Wamae, W., Diepeveen, S., Wooding, S., and Grant, J. (2013). Measuring Research: A Guide to Research Evaluation Frameworks and Tools. RAND Corporation. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG1217.html (accessed October 25, 2021).

Hanney, S., Kanya, L., Pokhrel, S., Jones, T., and Boaz, A. (2020). What is the Evidence on Policies, Interventions and Tools for Establishing and/or Strengthening National Health Research Systems and Their Effectiveness? WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Hunter, E. L., Edmunds, M., Dungan, R., Anyangwe, D., and Ruback, R. (2018). How Evidence Drives Policy Change: A Study of Return on Investment in Public Health and Multi-Sector Collaborations. Academy Health.

Remme, J. H. F., Adam, T., Becerra-Posada, F., D'Arcangues, C., Devlin, M., Gardner, C., et al. (2010). Defining research to improve health systems. PLoS Med. 7:e1001000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001000

University of Birmingham (2021). Responsible Metrics. University of Birmingham Intranet Website. Available online at: https://intranet.birmingham.ac.uk/as/libraryservices/library/research/influential-researcher/responsible-metrics.aspx (accessed February 14, 2021).

Keywords: health research, research metrics, public health, research outcomes, research impact, research measurement

Citation: Gemechu N, Werbick M, Yang M and Hyder AA (2022) Research Metrics for Health Science Schools: A Conceptual Exploration and Proposal. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 7:817821. doi: 10.3389/frma.2022.817821

Received: 18 November 2021; Accepted: 18 March 2022;

Published: 25 April 2022.

Edited by:

Michael Julian Kurtz, Harvard University, United StatesReviewed by:

Grisel Zacca González, Centro Nacional de Información de Ciencias Médicas, Infomed, CubaAnthony Bowen, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, United States

Copyright © 2022 Gemechu, Werbick, Yang and Hyder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nigussie Gemechu, ngemechu@gwu.edu

†ORCID: Nigussie Gemechu orcid.org/0000-0001-5285-484X

Meghan Werbick orcid.org/0000-0002-7688-4274

Michelle Yang orcid.org/0000-0002-9752-4235

Adnan A. Hyder orcid.org/0000-0002-7292-577X

Nigussie Gemechu1*†

Nigussie Gemechu1*†  Adnan A. Hyder

Adnan A. Hyder