Structurally unjust: how lay beliefs about racism relate to responses to racial inequality in the criminal legal system

- 1Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, NY, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, Institution for Social and Policy Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Racial inequality has been a persistent component of American society since its inception. The present research investigates how lay beliefs about the nature of racism—as primarily caused by prejudiced individuals or, rather, to structural factors (i.e., policies, institutional practices) that disadvantage members of marginalized racial groups—predict reactions to evidence of racial inequality in the criminal legal system (Studies 1–3). Specifically, the current research suggests that holding a more structural (vs. interpersonal) view of racism predicts a greater tendency to perceive racial inequality in criminal legal outcomes. Moreover, White Americans' lay beliefs regarding racism, coupled with their general degree of preference for societal hierarchy, predict support for policies that would impact disparities in the U.S. prison population. Together, this work suggests that an appreciation of structural racism plays an important role in how people perceive and respond to racial inequality.

Introduction

Stark, obstinate racial inequality has long been a hallmark of American society. Indeed, substantial racial disparities persist in nearly every important domain of contemporary American life, including education (U.S. Department of Education, 2016; Oh et al., 2024), health (Washington, 2006), housing (Massey and Denton, 1993), and wealth (Bhutta et al., 2020). Among the many domains plagued by racial inequality, racial disparities in the U.S. criminal legal system are some of the most stark and persistent, especially those endemic to policing and mass incarceration (Alexander, 2010). Indeed, over the past several decades, an ever-growing list of high-profile instances of police brutality (e.g., the beating of Rodney King in 1992; the killings of Rekia Boyd in 2012, Michael Brown in 2014, and George Floyd in 2020), have coincided with a growing salience of racism and racial inequity in the U.S. criminal legal system (e.g., Weitzer, 2015; Creighton and Wozniak, 2019; Leach and Teixeira, 2022), which has garnered an influx of media attention and held a central position in public discourse. But how does the salience of such racial disparities impact White Americans' support for the punitive policies at their root?

Given that significant investment in policing and mass incarceration has led to a negligible reduction in crime rates (Alexander, 2010; Chalfin et al., 2022), one might expect that the very fact of their racially disparate impact would reduce support for the “tough on crime” policies that have engendered the growth of the carceral state. Consistent with this idea, recent research suggests that exposure to evidence of these racial inequities, as conveyed through racial justice movements like #BlackLivesMatter, may have reduced White Americans' levels of anti-Black bias (Sawyer and Gampa, 2018; Mazumder, 2019), increased their awareness of racial discrimination and support for policy efforts to redress racial inequality (Mutz, 2022), and even led to a significant decrease in police homicides (Skoy, 2021; Campbell, 2023).

Nonetheless, a separate, growing, body of research indicates that simply presenting White Americans with evidence of racial disparities in the criminal legal system, devoid of any context for how these disparities are created and maintained, may not lead to further interest in efforts to redress this inequality (see Hetey and Eberhardt, 2018). In fact, mere exposure to evidence of these racial disparities has been shown to either have no impact on policy preferences (e.g., Bobo and Johnson, 2004; Dunbar, 2022) or, in some cases, even lead to increased support for punitive carceral policies (Peffley and Hurwitz, 2007; Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014; Gottlieb, 2017; Peffley et al., 2017; Creighton and Wozniak, 2019). Given these divergent findings, further investigation is needed to elucidate the psychological factors implicated in the relationship between White Americans' exposure to racial inequality in the criminal legal system and their punitive policy support (or lack thereof). The present research considers two such factors: namely, lay beliefs about the nature of racism, and preferences for group-based societal inequality, more generally.

Lay beliefs about the nature of racism

There has been considerable social psychological research demonstrating that individuals' lay beliefs, or their “fundamental assumptions about the self and the social world” (Molden and Dweck, 2006) can meaningfully affect how they interpret and interact with their environment. Contemporary research in social psychology has explored how lay beliefs about the nature of racial prejudice vary among individuals, shaping how individuals think, feel, and behave, in a number of key ways (e.g., Hodson and Esses, 2005). For instance, variability in the belief that individuals' racial biases are relatively fixed or malleable (i.e., able to be altered) can predict how people navigate interracial interactions (e.g., Carr et al., 2012; Neel and Shapiro, 2012). Moreover, other research has documented individual and group differences related to which attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, are identified as “racist” (e.g., Sommers and Norton, 2006; Carter and Murphy, 2015). Building on this literature, the present work considers a different set of lay beliefs about the nature of contemporary racism; namely, whether, and to what extent, people primarily conceptualize racism in terms of individual-level biases and discrimination (i.e., interpersonal racism), or also in terms of a constellation of practices, policies, and social structures that systematically, and in tandem, function to disadvantage members of marginalized racial groups (i.e., structural racism).

Another body of research has investigated a conceptually similar distinction between person-centered and system-centered explanations of inequality, in general, and racial inequality, in particular. Foundational work in sociology and political science, for instance, has examined how Americans reason about societal inequality. Much of this work has considered explanations for poverty (e.g., Feagin, 1972, 1975) and economic inequality (Hochschild, 1981; Kluegel and Smith, 1986; McCall, 2013) as products of “individualistic” factors (e.g., effort, ability, moral failings on the part of members of the disadvantaged group), or of “structural” factors (e.g., differential access to opportunity, exploitation, discrimination). Consistent with the tenets of the American Dream, most Americans tend to endorse individualistic explanations for success (or lack thereof) rather than more structural explanations (see McCall et al., 2017). Similarly, classic work has considered person-centered, compared with system-centered, attributions for racial inequality (e.g., Campbell, 1971; Kluegel and Smith, 1986; McConahay, 1986). This work has demonstrated that White Americans, in particular, tend to disproportionately attribute the continued presence of racial inequality in U.S. society after the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s to the personal failings of Black Americans, such as Black Americans' lack of motivation to succeed, rather than to systemic barriers, such as persistent racial discrimination. These differing explanations for inequality are important, of course, because they predict support for different types of interventions aimed at reducing it, in addition to the presence or absence of such support. Specifically, endorsement of person-centered (vs. system-centered) explanations for inequality—racial or economic—is associated with lower support for government intervention to redress societal disadvantage (e.g., Kluegel, 1990; see also McCall et al., 2017).

Although related to this fundamental distinction between person-centered vs. system-centered attributions for racial inequality, the lay beliefs that we examine in the present work distinguish between different types of discrimination— as rooted in individuals' racial biases vs. discriminatory societal structures. That is, we examine differences in White Americans' lay beliefs of the nature of contemporary racism as an explanation for racial inequality.

Social scientists have long considered the multifaceted nature of racial discrimination. Allport (1954), for instance, noted the roles of both interpersonal factors, such as personality and attitudes, as well as societal factors, such as norms and laws, in supporting and maintaining the persistence of racial discrimination. Racial discrimination, and racism, more broadly, can be thought of as emerging from individuals and/or systems operating in ways that disadvantage racial minorities, relative to White people (see Rucker and Richeson, 2021). Interpersonal racism is characterized by the negative attitudes that individuals hold regarding members of different racial and/or ethnic groups. When considered at the interpersonal level, racism and racial prejudice are virtually synonymous, and discrimination is thought to emerge from individuals' prejudices, be they explicit or implicit. Structural racism, in contrast, is characterized by the interaction of policies, practices, and/or laws that disparately impact members of marginalized racial or ethnic groups. For instance, laws creating strict identification requirements to vote have a disparate negative impact on voter turnout among racial minority (and lower SES) voters (e.g., Hajnal et al., 2017). Such laws, policies, and practices may be formed with or without discriminatory intent. Indeed, evidence of racially disparate outcomes is often suggestive of the operation of structural racism.

Interpersonal and structural forms of racism are certainly not mutually exclusive, and both are concerning in their own right. Further, despite the removal of overtly discriminatory laws and some social conventions, there is considerable evidence suggesting that structural forms of racism continue to play a significant role in maintaining societal racial inequality (e.g., Massey and Denton, 1993; Bonilla-Silva, 2006; Hatzenbuehler, 2016; Salter et al., 2018; Rucker and Richeson, 2021). Yet, research suggests that White Americans are much less likely to think of contemporary racism in structural, compared to interpersonal, terms (e.g., Unzueta and Lowery, 2008; Nelson et al., 2013), which may help to account for the apparent disconnect between their support for racially egalitarian principles and relative lack of concern about persistent societal racial disparities (Bobo, 2001). Moreover, awareness of structural forms of racism seems to predict greater recognition of, and interest in redressing, societal racial inequality (e.g., Adams et al., 2008; O'Brien et al., 2009). Taken together, this work suggests that accounting for the extent to which White Americans conceptualize racism as interpersonal or structural may have important implications for predicting their responses, after being exposed to evidence of societal racial inequality.

Racism lay beliefs and hierarchy-maintaining ideologies

Among White Americans, why is there so little appreciation of the role of structural racism in maintaining racial inequality in contemporary society? One likely contributor is a lack of education about the history of racism in the U.S. (Nelson et al., 2013), as exposure to information about historical and structural racism appears to increase White Americans' appreciation for its impact (e.g., Adams et al., 2008; Bonam et al., 2019). But this failure to educate White Americans about this history is likely complimented by powerful, identity-based psychological motives. For example, there is evidence to suggest that, to mitigate threats to their self- and group-image, White Americans are motivated to deny personally harboring racial biases (e.g., O'Brien et al., 2010; Howell et al., 2017) and to downplay the contemporary impact of racism, in general, on members of disadvantaged groups (Adams et al., 2006). However, among White Americans who acknowledge that racism exists, reminders of structural forms of racism, compared with interpersonal forms, may be especially threatening. This heightened threat may be due to the greater difficultly White Americans face in denying that they benefit from structural racism, relative to their ability to deny accusations of holding individual-level racial biases (Unzueta and Lowery, 2008).

In addition to motivations to preserve both self- and group-level esteem, beliefs about structural racism also likely connect with White Americans' motives to maintain the present racial hierarchy. According to Social Dominance Theory (SDT; Sidanius and Pratto, 1999), for instance, despite the ubiquity of group-based hierarchies among human social groups, people are generally motivated to perceive society as fair. Critically, SDT also emphasizes the important role of “legitimizing myths,” or status-legitimizing ideologies, as a means of maintaining perceptions of societal fairness, despite the ubiquity of group-based inequality (see also System Justification Theory; e.g., Jost, 2020). Neville et al. (2013), for instance, argue that the denial of structural forms of racism is a core component of a broader “colorblind” racial ideology, and serves as an important legitimizing myth to justify the existing racial status hierarchy. Consistent with this idea, they observe that “colorblind racism” is more likely to be observed among individuals higher in Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), an individual difference measure gauging one's degree of preference for social hierarchy (e.g., SDO; Sidanius and Pratto, 1999). In all, this research suggests that lay beliefs about the nature of racism, and preference for hierarchy more generally (i.e., SDO) may have interrelated, but conceptually distinguishable implications for predicting subsequent responses, after exposure to evidence of societal racial inequality.

To be sure, there are several psychological constructs that are likely related to White Americans' beliefs about structural racism (e.g., System Justification; Kay and Jost, 2003; Symbolic Racism; Kinder and Sears, 1981; Right-Wing Authoritarianism; Altemeyer, 1981; meritocratic threat; Knowles et al., 2014). However, SDO may be especially relevant due to its well-established association with individuals' beliefs about societal inequality. Indeed, individual differences in SDO have been shown to predict espousing ideologies and supporting specific policies implicated in the maintenance of intergroup hierarchy (see Pratto et al., 2006). Moreover, recent work has found that SDO influences the extent to which individuals perceive societal inequality between dominant and subordinated groups (Kteily et al., 2017), in addition to their support for policies designed to reduce it. Taken together, this work suggests that greater group dominance motives (i.e., higher SDO) likely operate in tandem with beliefs about structural racism in prompting people to deny or justify racial disparities. Consequently, the overarching question guiding the present research is whether lay beliefs about the interpersonal and/or structural nature of racism, perhaps in conjunction with individual differences in SDO, inform White Americans' responses, after exposure to racial inequality in the U.S. criminal legal system.

Overview of the present research

The present research examines whether individual differences in the tendency to think of racism in terms of biased individuals (interpersonal), or structures that disadvantage members of marginalized racial groups (structural), predict White Americans' reactions to evidence of racial inequality in the U.S. prison population (Studies 1–3). Specifically, in three studies, we examine the role of racism lay beliefs, in conjunction with individual differences in preference for societal hierarchy (i.e., SDO), in predicting reactions to evidence of racial disparities in the U.S. criminal legal system.

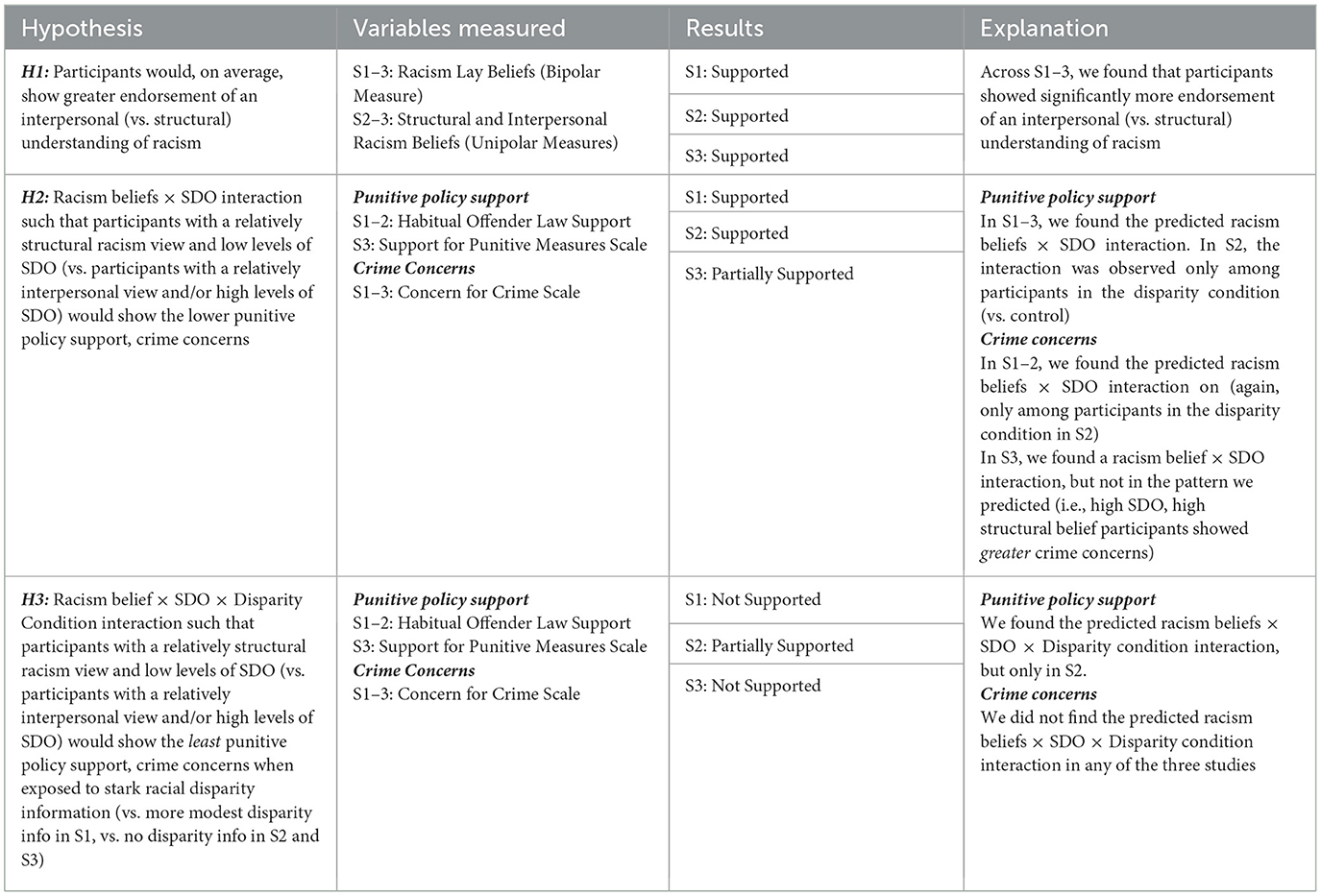

Consistent with past research (e.g., Unzueta and Lowery, 2008), we expected White Americans, on average, to endorse an interpersonal understanding of racism more than a structural one (H1). We also expected racism lay beliefs and SDO to predict responses to evidence of racial disparities in the U.S. prison population, such that White Americans with a relatively more structural (vs. interpersonal) lay belief, and those with relatively lower (vs. higher) levels of SDO would show lower support for harsh carceral policies (H2). Finally, we predicted that participants with a relatively structural racism view and lower levels of SDO (vs. those with a relatively interpersonal view and/or high levels of SDO) would show the least punitive policy support after exposure to information suggesting a stark racial disparity, compared to a more modest racial disparity information (S1), or to no racial disparity information (S2–3; H3). See Table 1 a summary of hypotheses, across Studies 1–3.

Study 1

In Study 1, we sought to examine (1) whether White Americans tend to endorse an interpersonal, rather than structural, understanding of racism (e.g., Unzueta and Lowery, 2008) and (2) whether White Americans' tendency to hold an interpersonal (vs. structural) lay belief predicts how they respond to evidence of racial inequality in the U.S. criminal legal system. Specifically, we sought to extend past research finding that exposure to starker vs. more modest racial disparities in the prison population led White American participants to express greater support for harsh carceral policies (e.g., Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014; Peffley et al., 2017). Given evidence suggesting that an appreciation for structural racism predicts greater interest in redressing racial disparities, we thought that the tendency to show more punitive policy support, after exposure to starker disparities in the prison system, may be limited to individuals who tend to endorse a relatively interpersonal (vs. structural) understanding of racism.

Moreover, we examined whether the role of interpersonal/structural racism beliefs, in predicting responses to racial disparities in the U.S. prison system, may also depend on participants' degree of preference for societal hierarchy (i.e., SDO), which we posit is an especially important individual difference factor in predicting reactions to evidence of racial inequality. The inclusion of SDO in the present study also allowed us to examine whether it is conceptually distinguishable from interpersonal/structural racism beliefs and, if so, to ascertain which is a more important predictor of responses to racial disparity information.

To this end, we recruited a sample of White participants and assessed their racism lay beliefs. We then exposed participants to information detailing either relatively stark or modest racial disparities in the U.S. prison population. Then, participants rated how much they would support a punitive policy being enacted in their home state, their concern that crime would increase should such a law be abolished, and their level of SDO. We expected that, consistent with past research, participants would report greater punitive policy support and crime concerns after exposure to evidence of a starker (vs. more modest) racial disparity in the U.S. prison population.

Further, we anticipated that participants' racism lay beliefs would moderate the effect of exposure to racial disparity information, such that those with a more structural (vs. interpersonal) racism belief would express less punitive policy support and less concern about crime when exposed to starker, rather than more modest, racial disparity information. We also anticipated that those with a relatively structural (vs. interpersonal) racism belief and relatively low (vs. high) levels of SDO would show the least punitive policy support and crime concern, after exposure to starker (vs. modest) racial disparity information.

Method

Participants

Power analyses (Faul et al., 2009) suggested that 235 participants would be adequate to detect a small-to-medium effect of our experimental manipulation and its interaction with racism lay beliefs (f2 = 0.04, assuming 80% power).1 We recruited an initial sample of 343 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk in exchange for $1. We were interested in the perspectives of White Americans, so we excluded 100 participants who did not self-identify solely as “White or Caucasian” and an additional two participants who did not report holding U.S. citizenship from the sample. After removing these participants, the final sample included 241 White U.S. Citizens (43% female; Mage = 36.26, SD = 11.06).

Materials and measures

Racism lay beliefs

Participants completed a single-item measure assessing their lay beliefs about racism. Using a measure adapted from past research (O'Brien et al., 2009), participants were first prompted: “When it comes to racism in the United States, which do you think is the bigger problem today: racist individuals who have negative attitudes toward racial and ethnic minorities, or institutional practices that disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities? Please indicate where you fall on this spectrum.” Then, participants indicated their response using an 11-point scale with responses ranging from “Individuals' negative racial attitudes and discriminatory behaviors committed by individuals toward other individuals” (1) to “Institutional practices and structural factors (e.g., laws, policies, etc.) that disadvantage some racial groups more than others” (11), with a midpoint anchored at “Both racially-biased individuals and institutional practices/structural factors that disadvantage some racial groups more than others” (6). Scores above 6 reflect a more structural racism lay belief and scores below 6 reflect a more interpersonal racism lay belief.

Racial disparity manipulation

Similar to manipulations used in previous research (e.g., Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014), participants were shown demographic information about the U.S. prison population. Specifically, participants were shown (a) the number of inmates in the U.S. prison population, (b) the number of prisons in the U.S., and (c) graphical representations of the gender and age demographics of the prison population. Last, they were shown a graphical representation of the racial demographics of the prison population, which was manipulated such that the population was either ~40% Black or ~60% Black. Importantly, these percentages were drawn from veridical U.S. prison demographic data, with 40% approximating the percentage of Black inmates in U.S. prisons, nationwide, and 60% approximating the percentage of Black inmates in states like Louisiana or Illinois (Sakala, 2014). The percentages of White inmates depicted in the prison population were roughly 30% and 11%, respectively, and percentages of other groups (e.g., Latinos) did not vary across conditions.

Habitual offender law support

Participants were first provided with a brief description of habitual offender laws: “[h]abitual offender laws (also often called ‘three-strikes' laws) are laws designed to impose harsher sentences on habitual offenders who are convicted of three or more serious criminal offenses.” Then, they read about the prevalence of these laws in the U.S. and were asked to report the extent to which they would support a habitual offender law in their state with a single-item measure (“I would support a proposed habitual offender law in my state”). Participants recorded their responses on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Concern about crime

Participants were first prompted “[r]ecently, the fairness and constitutionality of habitual offender laws have come under question, with several notable state and federal initiatives to have them significantly amended or repealed.” Participants then completed a four-item measure used in previous research (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014) to assess the extent to which they thought crime would increase if habitual offender laws were banned, nationally (e.g., “Given the controversy, how worried are you that crime will get out of control without habitual offender laws?”). Participants recorded their responses on six-point Likert scales from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extremely). Responses to the items were averaged to form an index of crime concerns. Higher scores reflect greater concern that crime will become uncontrollable if habitual offender laws are repealed (α = 0.93).

Racial disparity manipulation check

Participants were asked to recall whether the percentage of Black Americans in the U.S. prison population was more or < 50%. Participants in the stark disparity condition (60% Black) who indicated that the prison population was < 50% Black, and participants in the more modest disparity condition (40% Black) who indicated that the prison population was more than 50% Black, were designated as having failed the manipulation check.2

Social Dominance Orientation

Participants completed the Social Dominance Orientation-7 Scale (Ho et al., 2015)—an eight-item measure of the extent to which people agree or disagree with statements expressing anti-egalitarian views (e.g., “An ideal society requires some groups to be on top and others to be on the bottom”). Participants recorded their responses on seven-point Likert scales from 1 (strongly oppose) to 7 (strongly favor). Higher scores reflect higher levels of SDO (α = 0.94).

Political ideology

Participants completed a two-item measure assessing their endorsement of a liberal or conservative political ideology. Participants rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: “I endorse many aspects of the conservative political ideology” and “I endorse many aspects of the liberal political ideology.” Participants recorded their responses on point-point Likert scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The liberal item was reversed prior to averaging with the conservative item to index participants' level of political conservatism (r = 0.79). Higher scores reflect greater endorsement of a conservative political ideology.

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants completed the lay beliefs measure, embedded in a series of distractor measures, and administered prior to the experimental manipulation. Participants were next informed that they would complete a study on their opinions regarding a “randomly selected” policy initiative. All participants were told that they would provide judgments about a criminal legal policy and were provided with basic demographic information pertaining to the U.S. prison system. Embedded within this demographic information, participants were shown information suggesting either relatively stark (60% Black) or modest (40% Black) racial disparity in the prison system.

Afterwards, participants were provided with a brief description of habitual offender laws, and asked how much they would support a habitual offender law proposed in their state. Then, participants reported their crime concerns, and completed the racial disparity manipulation check. Finally, participants completed the demographic survey, where they reported their age, gender, political ideology,3 and SDO, after which they were debriefed, thanked, and compensated for their participation.

Results

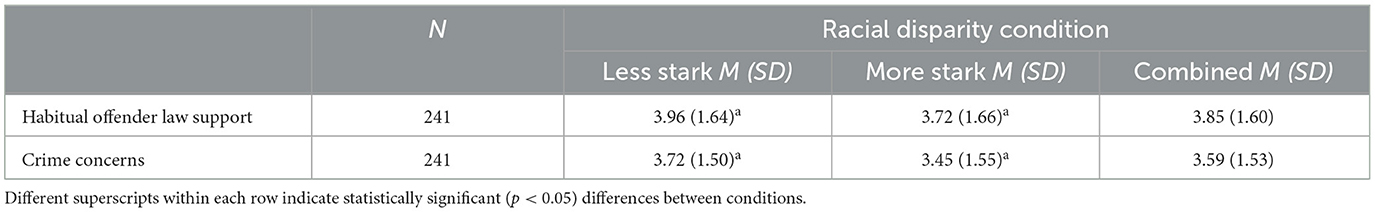

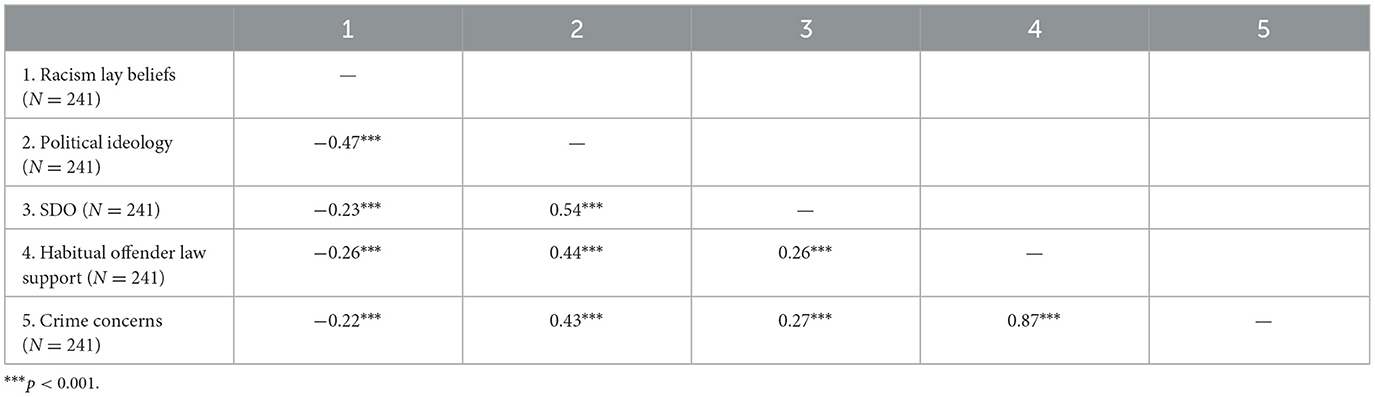

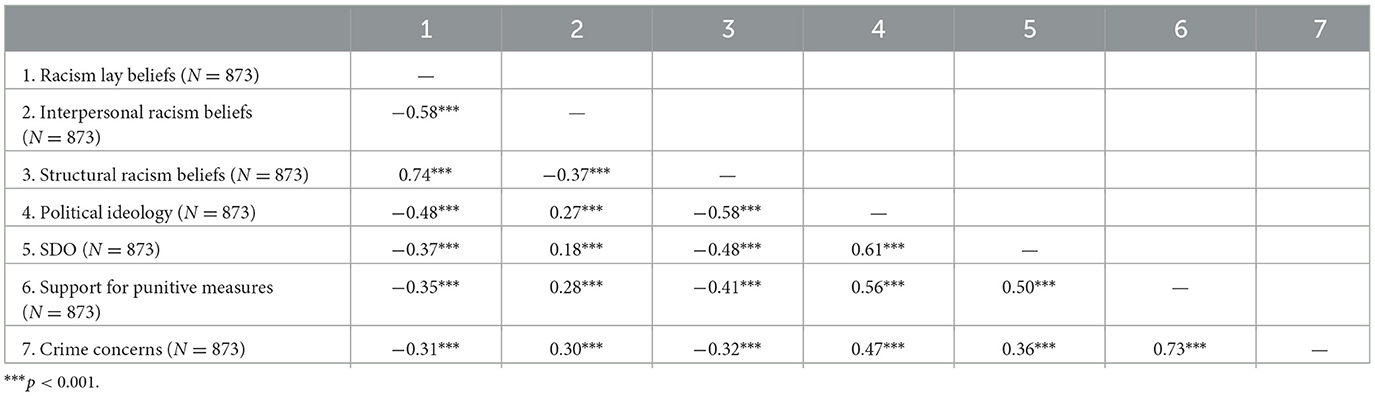

A summary of core hypotheses and results of Studies 1–3 are provided in Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations between measures in Study 1 are provided in Tables 2, 3, respectively.

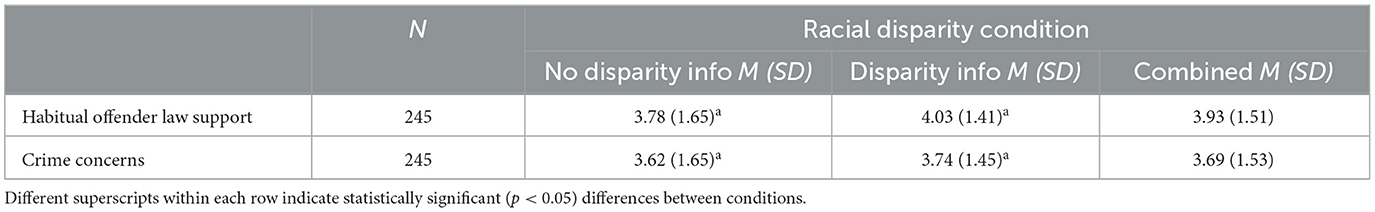

Table 2. Study 1 habitual offender law support, and concern for crime by racial disparity condition.

Table 3. Study 1 correlations among racism lay beliefs, political ideology, Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), habitual offender law support, and concern for crime.

Preliminary analyses

Participants in Study 1 were relatively liberal, on average (M = 3.46, SD = 1.96). As predicted, we also found that participants tended to hold a significantly more interpersonal understanding of racism, relative to the scale midpoint (M = 5.49, SD = 2.73), t(240) = −2.90, p = 0.004, 95% CI (−0.86, −0.16).

Further, we calculated correlations among racism lay beliefs, political ideology, and SDO. As shown in Table 3, racism lay beliefs (higher numbers reflect a more structural understanding) were significantly, negatively correlated with conservatism and SDO (rs = −0.47 and −0.23, respectively). Given this pattern of correlations, our primary analyses control for political ideology, participant age, gender, and educational level.

Primary analyses

Habitual offender law support

We regressed support for habitual offender laws on the racial disparity manipulation (60% Black vs. 40% Black), individual differences in racism lay beliefs (mean-centered), levels of SDO (mean-centered),4 and the interactions between the variables. Contrary to prior research (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014), we did not find a significant main effect of the racial disparity manipulation on support for habitual offender laws, t(227) = −0.34, p = 0.74, 95% CI (−0.23, 0.16). We also did not find a significant direct effect of racism lay beliefs, t(227) = −1.25, p = 0.21, 95% CI (−0.13, 0.03), or SDO, t(227) = 1.50, p = 0.14, 95% CI (−0.04, 0.27), on support for habitual offender laws. Additionally, we did not observe an interaction between racism lay beliefs and the racial disparity manipulation, t(227) = 1.31, p = 0.19, 95% CI (−0.02, 0.12).

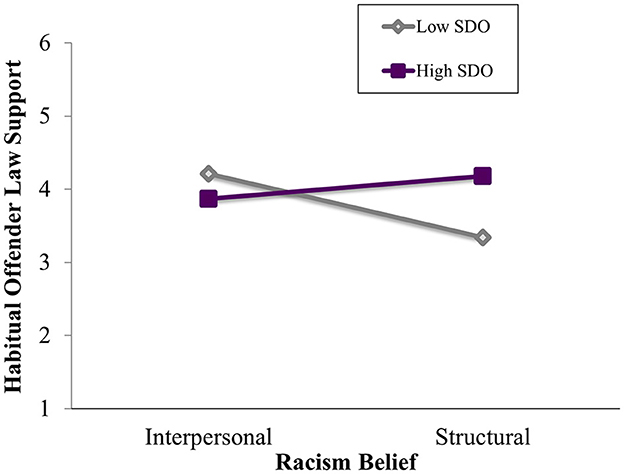

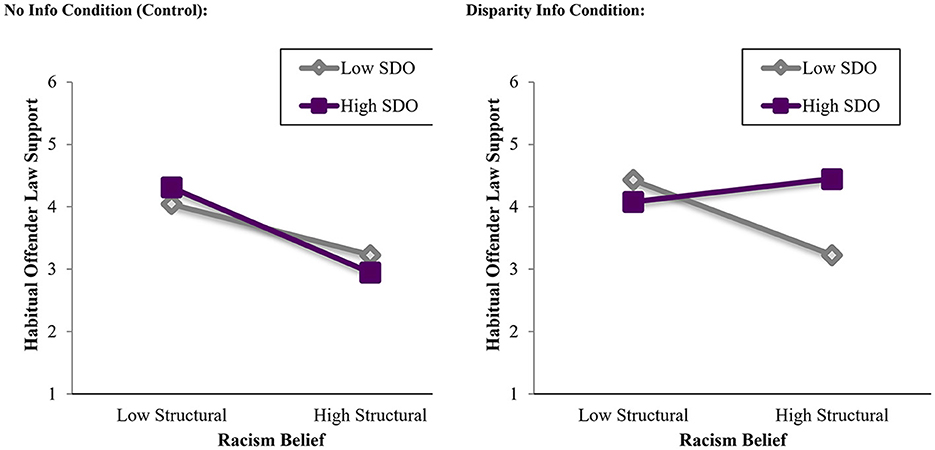

However, we did observe a statistically significant interaction between racism lay beliefs and SDO, t(227) = 3.51, p = 0.001, 95% CI (0.03, 0.11). As shown in Figure 1, whereas holding a more structural (vs. interpersonal) racism lay belief was associated with lower support for habitual offender laws among more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(227) = −3.00, p = 0.003, 95% CI (−0.26, −0.05), racism lay belief did not predict support for habitual offender laws among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), t(227) = 1.25, p = 0.21, 95% CI (−0.04, 0.15). Last, neither the interaction between SDO and the disparity manipulation, t(227) = −0.33, p = 0.74, 95% CI (−0.15, 0.11), nor the three-way interaction between racism lay beliefs, SDO, and the disparity manipulation, t(227) = −0.81, p = 0.42, 95% CI (−0.06, 0.02), were significant.

Figure 1. Interaction of racism belief and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) on support for a proposed habitual offender law in Study 1. SDO plotted at ± 1 SD above or below the mean.

Concern about crime

We submitted participants' reported crime concerns to the same regression outlined previously. Again, we found no main effect of the racial disparity manipulation, t(227) = −0.48, p = 0.63, 95% CI (−0.22, 0.14). There was also no direct effect of racism lay beliefs, t(227) = −0.66, p = 0.51, 95% CI (−0.10, 0.05), nor was the interaction between lay beliefs and the disparity manipulation statistically significant, t(227) = 1.54, p = 0.13, 95% CI (−0.01, 0.12).

Moreover, we did not observe a direct effect of SDO, t(227) = 1.80, p = 0.07, 95% CI (−0.01, 0.27), but its interaction with racism lay beliefs was statistically significant, t(227) = 3.66, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.03, 0.11). Similar to the pattern observed for habitual offender law support, holding a more structural (vs. interpersonal) lay belief was associated with lower levels of crime concern among the more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(227) = −2.65, p = 0.009, 95% CI (−0.23, −0.03). Among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), however, racism lay beliefs were unrelated to crime concerns, t(227) = 1.84, p = 0.07, 95% CI (−0.01, 0.17). Again, we did not find a significant interaction of SDO and the disparity manipulation, t(229) = 0.43, p = 0.67, 95% CI (−0.09, 0.14), or of the three-way interaction of racism lay beliefs, SDO and the disparity manipulation, t(227) = 0.68, p = 0.50, 95% CI (−0.02, 0.05).

Discussion

The findings of Study 1 suggest that White Americans' support for harsh criminal justice policies, after exposure to racial disparities in the U.S. prison population, depends both on their lay beliefs about the interpersonal and structural nature of racism, as well as their levels of SDO. Specifically, after exposure to racial disparity information (of any kind), it was only among participants with more egalitarian ideals (i.e., those low in SDO) that holding a relatively structural (vs. interpersonal) racism view was associated with lower support for habitual offender laws and lower crime concerns. Among participants higher in SDO, however, support for habitual offender laws and crime concerns did not differ as a function of their racism lay beliefs. In other words, it is the combination of a structural understanding of racism and a greater preference for societal egalitarianism that predicts concern about racial disparities in U.S. prisons.

The results of Study 1 offer key evidence regarding the relevance of racism lay beliefs for both perceptions of, and reactions to, racial disparities. Specifically, these results underscore the importance of examining individual differences in beliefs about the structural and/or interpersonal nature of racism, in addition to individual differences in SDO, in predicting White Americans' responses to evidence of racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Surprisingly, and contrary to past research (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014), policy support and crime concerns did not differ based exposure to different levels of racial inequality, in general, or in combination with lay beliefs or SDO. Given these inconsistent patterns of results, the role of racism lay beliefs in moderating reactions to varying levels of racial disparities remains unclear. With the present findings in mind, in Study 2, we sought to clarify the role of exposure to racial disparity information, in conjunction with structural racism beliefs and preference for social hierarchy (SDO), in shaping support for punitive carceral policies.

Moreover, there were notable limitations with our measure of racism lay beliefs in Study 1. First, our racism beliefs measure used a somewhat heavy-handed prompt (i.e., “which is the bigger problem today?”), which made it difficult to disentangle participants' general conceptualizations of racism from the extent to which they believe it to be a societal problem. And second, the use of a single-item, continuous lay belief measure limited our ability to capture a potentially more complex relationship between participants' interpersonal and structural racism beliefs. For example, responses at the midpoint of the scale indicated that participants' though that both interpersonal and structural factors were equally at play, but it was otherwise unclear how participants may have weighed their relative importance or significance. This measure was also unable to adequately capture the views of participants who thought that neither interpersonal nor structural forms of racism were a “big problem.” Thus, in Study 2, we revised the prompt to feature more neutral language, and measured racism beliefs both as separate, unipolar measures of interpersonal and structural beliefs, and as a single, bipolar measure.

Study 2

Study 2 re-examined the impact of exposure to racial disparity information on White Americans' support for carceral policies, both directly, and in conjunction with racism lay beliefs and SDO. Contrary to past research (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014), in Study 1, we found that the magnitude of the racial disparity to which participants were exposed had no impact on carceral policy support. To attempt to reconcile these discrepant findings, in Study 2, we conducted a more conservative test of the role of exposure to racial disparity information. Namely, we compared whether exposure to any racial disparity information, compared to no such exposure, affects participants' carceral policy preferences and crime concerns, either directly or in conjunction with lay beliefs about racism and/or SDO.

We recruited a sample of White participants and assessed both their racism lay beliefs and their level of SDO. In contrast with Study 1, however, participants were either exposed to information about the racial demographics of the prison population (using the “modest” disparity information from Study 1), or they were not exposed to any racial demographic information. As in Studies 1 and 2, participants then reported their support for habitual offender laws and their crime concerns, if such laws were abolished.

In line with findings from Study 1, we anticipated that participants with a relatively structural racism lay belief and a lower preference for social hierarchy would report the least support for punitive polices and be the least concerned about crime, compared with their high SDO counterparts, as well as participants with a relatively interpersonal understanding of racism. Further, we expected to observe this pattern of responses more strongly among participants who were exposed to information about the racial demographics of the prison population, compared to participants who were not exposed to racial disparity information.

Method

Participants

Power analyses (Faul et al., 2009) suggested that between 232 and 310 participants would be adequate to detect the interaction between racism lay beliefs and SDO (based on the effect size observed in Study 1) while also testing for the anticipated interaction between racism lay beliefs and racial disparity manipulation (f2 from 0.03 to 0.04, assuming 80% power). We recruited an initial sample of 413 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk in exchange for $1. Again, we were interested in the perspectives of White Americans, so we excluded 120 participants who did not self-identify solely as “White or Caucasian” and an additional six participants who did not report holding U.S. citizenship. We also excluded 42 participants from analyses for incorrectly recalling whether they were exposed to the racial demographics of the U.S. prison system.5 After removing participants who failed the manipulation check and those who requested their data be excluded, the final sample included 245 participants (51.4% self-identified as “female”; Mage = 36.93, SD = 11.06).

Materials and measures

Racism lay beliefs

Participants completed unipolar measures to assess beliefs about the structural and interpersonal nature of racism, separately. Specifically, participants were prompted “when I think of racism, I primarily think of…” and responded to the items “Institutional practices and structural factors (e.g., laws, policies, etc.) that disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities” (indicating an interpersonal lay understanding of racism) and “Negative attitudes and discriminatory behaviors by individuals toward racial and ethnic minorities” (indicating a more structural lay understanding of racism). Participants responded to each of these items on a six-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 5 (Very Much). Higher scores reflect greater endorsement of a structural and interpersonal racism belief, respectively.

Participants also completed a single-item measure similar to that used in Study 1, with a revision to the initial prompt. Participants were first prompted: “When you think of racism, is racism primarily caused by racist individuals who have negative attitudes toward racial and ethnic minorities (1), or is racism caused by institutional practices that happen to disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities (11).” The scale also anchored the midpoint, labeled “Racism is equally due to biased individuals and biased institutional practices” (6). Again, scores above 6 reflect a more structural racism lay belief and scores below 6 reflect a more interpersonal racism lay belief.6

Racial disparity manipulation and manipulation check

The manipulation and manipulation check were similar to those described in Study 1, with a few noteworthy changes. Instead of being shown two different disparity levels (e.g., 40% Black vs. 60% Black), participants were either provided with racially disparate prison demographic information (i.e., a prison population represented as 40% Black) or were provided with no racial demographic information. To ensure that any differences were not due to race being made salient in only one condition, however, the same screen appeared in both condition with “racial demographics” in the title, but whereas the actual information (i.e., pie chart) was presented in the racial disparity information condition, an error message appeared instead in the no disparity information condition (see the Supplementary material).

Additionally, as a manipulation check, participants were prompted “Did the graph that you previously viewed display the racial demographics of the U.S. prison population?” and either responded “Yes” or “No.”

Habitual offender law support

Participants completed the same item measuring their habitual offender law support described in Study 1, with higher numbers indicating greater support for habitual offender laws.

Concern about crime

Participants completed the same measure of crime concerns as was described in Study 1. Again, higher scores reflect greater concern that crime will become uncontrollable if habitual offender laws are repealed (α = 0.93).

Social Dominance Orientation

Participants reported levels of SDO (Ho et al., 2015) with the same measure used in Study 1. Again, higher scores reflect higher levels of SDO (α = 0.94).

Political ideology

Participants reported their political ideology with the two-item measure used in Study 1 (r = 0.82). Again, higher scores reflect greater endorsement of a conservative political ideology.

Procedure

Study 2 followed a procedure similar to that in Study 1. After providing informed consent, participants completed the lay beliefs measure, embedded in series of distractor measures, and administered prior to the experimental manipulation. Participants were then exposed to the prison demographic information (e.g., age, gender) within which they were randomly assigned either to be shown, or not shown, racial demographic information. Participants then indicated their support for habitual offender laws, crime concerns, and completed the racial disparity manipulation check item. Finally, participants completed the demographic survey on which they reported their age, gender, political ideology, and SDO, after which they were debriefed, thanked, and compensated for their participation.

Results

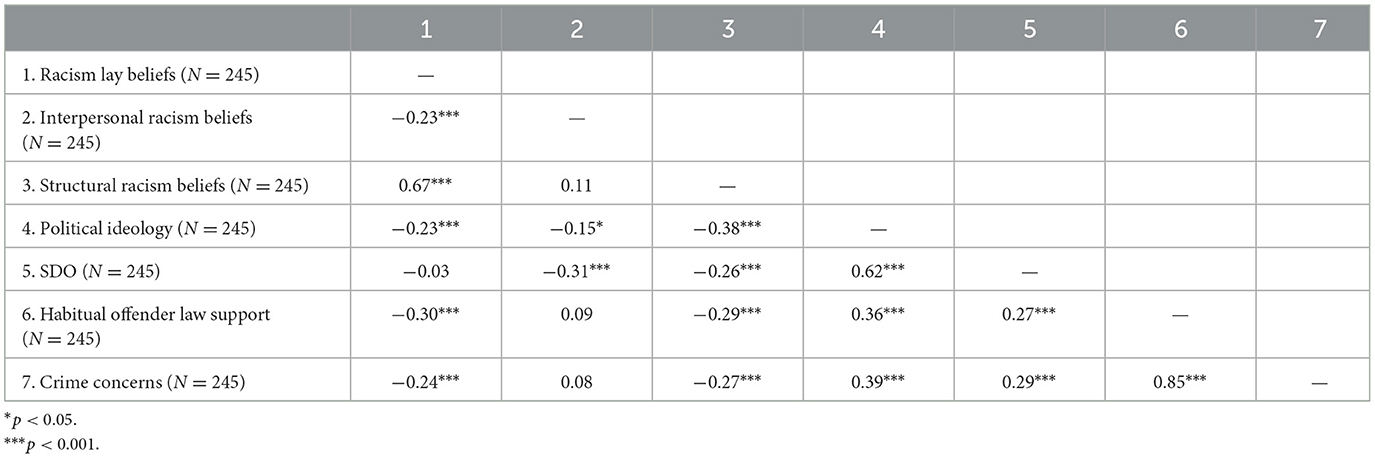

Descriptive statistics and correlations between measures are provided in Tables 4, 5, respectively.

Table 4. Study 2 habitual offender law support, and concern for crime by racial disparity condition.

Table 5. Study 2 correlations among racism lay beliefs, political ideology, Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), habitual offender law support, and concern for crime.

Preliminary analyses

We first examined the relationship between the bipolar and unipolar measures of interpersonal and structural racism beliefs. When measured via the unipolar items, participants showed significantly greater endorsement of an interpersonal racism view (M = 4.95, SD = 1.07), relative to a structural racism view (M = 3.67, SD = 1.59), t(244) = 11.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI (1.05, 1.51). Consistent with Study 1, when racism beliefs were measured via the bipolar measure, we found that participants tended to hold a significantly more interpersonal understanding of racism, relative to the scale midpoint (M = 5.13, SD = 2.50), t(244) = −5.43, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−1.18, −0.55). Primary analyses controlled for participants' endorsement of conservative political ideology, age, gender, education level and their interpersonal racism beliefs.

Primary analyses

Habitual offender law support

We regressed support for habitual offender laws on the racial disparity manipulation (disparity information vs. no disparity information), individual differences in structural racism beliefs (mean-centered), levels of SDO (mean-centered), and the interactions between the variables. We observed a significant effect of the racial disparity manipulation, t(231) = 2.08, p = 0.04, 95% CI (0.01, 0.40). Consistent with past research, but contrary to Study 1, participants who viewed racial disparity information (vs. no disparity information) reported greater support for habitual offender laws. Moreover, we observed a significant effect of structural racism beliefs, t(231) = −3.70, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.36, −0.11), such that the more participants tended to hold a structural racism view, the less support they expressed for habitual offender laws. This main effect was not moderated by an interaction with the racial disparity exposure manipulation, t(231) = 1.66, p = 0.10, 95% CI (−0.02, 0.23).

Further, the main effect of SDO was also not statistically significant, t(231) = 0.82, p = 0.41, 95% CI (−0.11, 0.26), nor was the interaction between SDO and the disparity exposure manipulation, t(231) = 1.04, p = 0.30, 95% CI (−0.07, 0.22), nor the interaction of SDO and structural racism beliefs, t(231) = 1.30, p = 0.20, 95% CI (−0.03, 0.14). However, we observed a significant three-way interaction between structural racism beliefs, SDO and the disparity manipulation, t(231) = 2.66, p = 0.01, 95% CI (0.03, 0.19).

As shown in Figure 2, we did not observe an interaction among participants who were not exposed to the racial disparity information, t(231) = −0.92, p = 0.36, 95% CI (−0.18, 0.07). However, we observed a significant SDO by lay belief interaction among participants who were exposed to the racial disparity information, t(231) = 2.95, p = 0.004, 95% CI (0.06, 0.28). Among participants who were exposed to racial disparity information, holding a more structural racism lay belief was associated with lower support for habitual offender laws among more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(231) = −3.56, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.58, −0.17), but structural racism beliefs did not predict support for habitual offender laws among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), t(231) = 0.95, p = 0.34, 95% CI (−0.12, 0.33).

Figure 2. Interaction of racism belief, Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), and disparity condition on support for a proposed habitual offender law in Study 2. SDO plotted at ± 1 SD above or below the mean.

Concern about crime

We submitted responses to the crime concern measure to the same regression outlined previously. We found no main effect of the racial disparity manipulation, t(231) = 0.95, p = 0.34, 95% CI (−0.10, 0.29), but a significant effect of structural racism beliefs, t(231) = −2.92, p = 0.004, 95% CI (−0.31, −0.06), such that the more participants tended to hold a structural racism view, the less concern about crime they reported. The interaction between the racial disparity manipulation and structural racism beliefs, however, was not significant, t(231) = 1.30, p = 0.19, 95% CI (−0.04, 0.21). The main effect of SDO was also not statistically significant, t(231) = 1.25, p = 0.21, 95% CI (−0.07, 0.30), nor was its interaction with the disparity manipulation, t(231) = 1.34, p = 0.18, 95% CI (−0.05, 0.25).

However, we did observe a significant interaction between SDO and structural racism beliefs t(231) = 2.08, p = 0.04, 95% CI (0.01, 0.17). Similar to the pattern observed in Study 1, holding a more structural racism belief was associated with lower levels of crime concern among the more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(231) = −3.82, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.48, −0.15). Among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), however, racism lay beliefs were unrelated to crime concerns, t(231) = −0.64, p = 0.53, 95% CI (−0.25, 0.13).

Although the three-way interaction between structural racism beliefs, SDO and the disparity exposure manipulation did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance, t(231) = 1.97, p = 0.05, 95% CI (0.0001, 0.17), given our predictions, we conducted exploratory analyses of the two-way interaction between SDO and structural racism beliefs within each disparity exposure condition. Consistent with our predictions, we did not observe an interaction among participants who were not exposed to the racial disparity information, t(231) = 0.07, p = 0.94, 95% CI (−0.12, 0.13).

However, we observed a significant SDO by lay belief interaction among participants who were exposed to the racial disparity information, t(231) = 3.01, p = 0.003, 95% CI (0.06, 0.28), such that, among participants who were exposed to racial disparity information, holding a more structural racism lay belief was associated with lower support for habitual offender laws among more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(231) = −3.34, p = 0.001, 95% CI (−0.56, −0.14), but structural racism beliefs did not predict support for habitual offender laws among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), t(231) = 1.24, p = 0.22, 95% CI (−0.08, 0.37).

Discussion

Building on the previous study, Study 2's findings further suggest that White Americans' support for harsh criminal justice policies, after exposure to racial disparities in the U.S. prison population, depends both on their lay beliefs about the structural nature of racism, as well as their egalitarian preferences, more generally. Specifically, and consistent with Study 1, it was only among participants with lower levels of SDO that holding a relatively structural racism view predicted less punitive policy support and crime concerns. Importantly, however, we only observed this interactive effect among participants who were exposed to racial demographic information (vs. those not exposed to racial demographic information). In other words, we find convergent evidence to suggest that the combination of a structural understanding of racism, and lower preference for societal hierarchy, following exposure to relevant racial disparity information, predicts White Americans' responses to evidence of racial disparities in the U.S. prison population.

Building from these consistent findings, in Study 3, we wanted to further examine the relationship between structural racism beliefs, SDO, and exposure to racial disparity information while addressing some limitations in our previous two Studies. First, we wanted to conduct Study 3 with a larger sample, to ensure adequate power to detect our higher order interactive effects. We also planned to measure participants' support for a variety of criminal justice policies, to ensure that our effects were not limited to a single policy type (i.e, habitual offender laws).

Study 3

Study 3 re-examined the impact of structural racism beliefs, SDO and exposure to racial disparity information on White Americans' support for punitive carceral policies. In Study 1, we found that participants' interpersonal/structural racism beliefs, combined with their level of preference for societal hierarchy (i.e., SDO) predicted support for a harsh carceral policy, regardless of the magnitude of the racial disparity to which they were first exposed. Further, in Study 2, we observed that it was only among participants exposed to racial disparity information (vs. no information) that the combination of structural racism beliefs and SDO predicted their carceral policy beliefs. To further elucidate the role of exposure to disparity information in shaping carceral policy beliefs, in Study 3, we again manipulated participants' exposure to racial disparity information (vs. no disparity information). We also refined the disparity manipulation to include U.S. racial demographics as relevant baseline information to illustrate the level of racial disparity in the U.S. prison population more clearly. Additionally, we asked participants about the extent to which they supported or opposed several other punitive carceral policies, to ensure that our findings generalize to a broader array of policies.

Consistent with Study 2, we anticipated that participants with a relatively structural racism view and a lower preference for social hierarchy would report the least support for punitive polices and be the least concerned about crime, compared with their high SDO counterparts and participants with a more interpersonal understanding of racism. Consistent with Study 2, we expected to observe this pattern of responses more strongly among participants who were exposed to information about the racial demographics of the prison population, compared to participants who were not exposed to racial disparity information.

Method

Participants

Power analyses (Faul et al., 2009) suggested that between 743 and 756 participants would be adequate to detect the interaction between racism lay beliefs, SDO, and racial disparity manipulation (based on the effect size observed in Study 2) while also testing for the interaction between racism lay beliefs and SDO observed in Studies 1 and 2 (f2 from 0.012 to 0.013, assuming 80% power). We recruited an initial sample of 1,066 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk in exchange for $1. Again, we were interested in the perspectives of White Americans, so we excluded 29 participants who did not self-identify solely as “White or Caucasian” and an additional nine participants who did not report holding U.S. citizenship. We also excluded 91 participants from analyses for incorrectly recalling whether they were exposed to the racial demographics of the U.S. prison system, as well as two participants who asked that their data be removed from the final sample, as they reported not completing the survey carefully. After removing these participants, the final sample included 873 participants (59.4% self-identified as “woman” or “female”; Mage = 44.01, SD = 13.55).

Materials and measures

Racism lay beliefs

Similar to those in Study 2, participants in Study 3 completed unipolar measures to assess beliefs about the structural and interpersonal nature of racism. Specifically, participants were prompted “Please rate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements” and responded to two structural items (“Most of the discrimination that racial and ethnic minorities face stems from policies that disproportionately disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities,” “Racism is primarily caused by institutional practices that disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities”) and two interpersonal items (“Racism is primarily caused by individuals who have negative attitudes toward, and beliefs about, racial and ethnic minorities,” “Most of the discrimination that racial and ethnic minorities face stems from interacting with racially-biased people”). Participants responded to each of these items on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores reflect greater endorsement of a structural (r = 0.87) and interpersonal (r = 0.70) racism belief, respectively.

Participants completed the same bipolar, 11-point, racism lay beliefs measure used in Study 2. Again, higher scores reflect a more structural (and less interpersonal) racism lay belief.

Racial disparity manipulation and manipulation check

The manipulation and manipulation check were similar to those described in Study 2 (i.e., racial disparity information vs. no racial disparity information). In Study 3, however, for each presentation of demographic information, including gender and age information, participants were also presented information about the U.S. population as a baseline. For example, among participants exposed to information about the racial demographics of the prison population, next to the graph of the racial demographics was a caption which read “Black/African Americans make up 13.3% of the U.S. population and make up 40.3% of the U.S. prison population” (see the Supplementary material).

Support for punitive measures

Participants completed a 12-item measure, adapted from past research (Chiricos et al., 2004; Hogan et al., 2005), gauging their support for a wide range of punitive carceral and criminal legal policies (e.g., “Making sentences more severe for all crimes,” “Locking up more juvenile offenders”; see Supplementary material for full list of items). Participants recorded their responses on 11-point Likert scales from 0 (Not supportive at all) to 7 (Very supportive). Higher numbers indicated greater support for punitive policy measures (α = 0.94).

Concern about crime

Participants reported their crime concerns with the same four-item measure used in Studies 1 and 2. Again, higher scores reflect greater concern that crime will become uncontrollable if habitual offender laws are repealed (α = 0.94).

Social Dominance Orientation

Participants reported levels of SDO (Ho et al., 2015) with the same measure used in Studies 1 and 2. Again, higher scores reflect higher levels of SDO (α = 0.93).

Political ideology

Participants reported their political ideology with the two-item measure used in Studies 1 and 2 (r = 0.83). Again, higher scores reflect greater endorsement of a conservative political ideology.

Procedure

Study 3 followed a procedure very similar to that of the previous two studies. First, participants completed a screening task designed to filter out automated responses, and those who passed this initial screener were directed to the consent form. After providing informed consent, participants completed the lay beliefs measures, embedded in series of distractor measures, just prior to the presentation of the prison demographics information and racial disparity manipulation. Participants were then exposed to the prison demographic information (e.g., age, gender) and were randomly assigned to be shown, or not shown, racial demographic information. Participants then indicated their support for punitive measures and crime concerns, followed by the racial disparity information manipulation check. Last, participants completed the demographic survey on which they reported their age, gender, and political ideology, and SDO, after which they were debriefed, thanked, and compensated for their participation.

Results

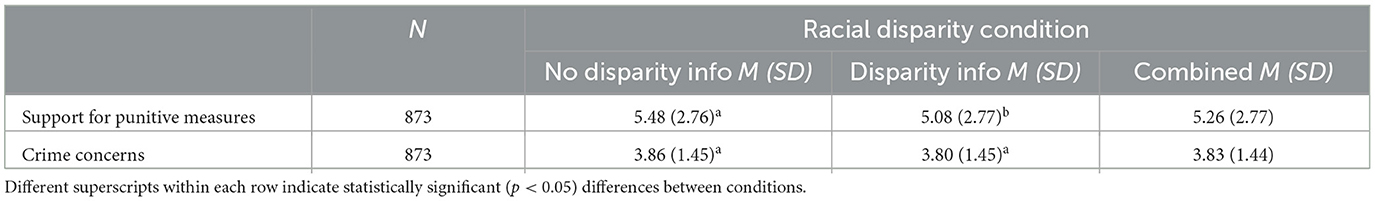

Descriptive statistics and correlations between measures are provided in Tables 6, 7, respectively.

Table 6. Study 3 support for punitive measures, and concern about crime by racial disparity condition.

Table 7. Study 3 correlations among racism lay beliefs, political ideology, Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), support for punitive measures, and concern for crime.

Preliminary analyses

When measured via the unipolar items, participants in Study 3, like those in Study 2, showed significantly greater endorsement of an interpersonal racism view (M = 4.24, SD = 1.18), relative to a structural racism view (M = 3.50, SD = 1.47), t(872) = 9.97, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.59, 0.88). Similarly, and consistent with Studies 1 and 2, when racism beliefs were measured via the bipolar measure, we found that participants tended to hold a more interpersonal understanding of racism, relative to the scale midpoint (M = 5.26, SD = 2.53), t(872) = −8.71, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.91, −0.58). Primary analyses controlled for participants' endorsement of conservative political ideology, age, education level and their interpersonal racism beliefs.

Primary analyses

Support for punitive measures

We regressed support for punitive measures on the racial disparity manipulation (40% Black vs. no race information), individual differences in structural racism beliefs (mean-centered), levels of SDO (mean-centered), and the interactions between the variables. We observed a significant effect of the racial disparity manipulation, t(854) = −2.68, p = 0.008, 95% CI (−0.38, −0.06). Contrary to our expectations, however, viewing disparity information (vs. no disparity information) was associated with less support for punitive measures. Moreover, we did not observe an effect of structural racism beliefs, t(854) = −0.61, p = 0.54, 95% CI (−0.17, 0.09), or an interaction between the racial disparity manipulation and structural racism beliefs, t(854) = −1.04, p = 0.30, 95% CI (−0.17, 0.05).

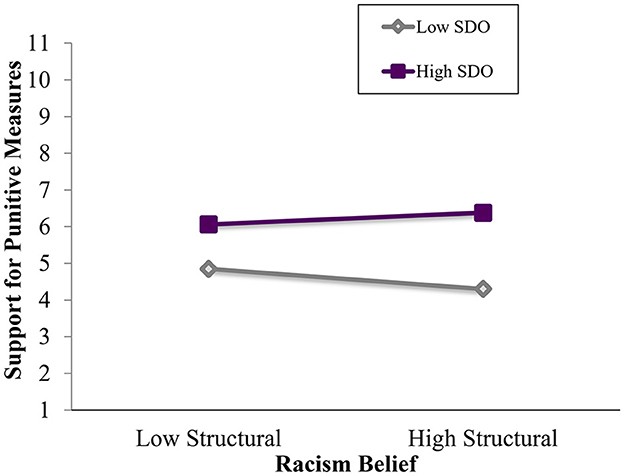

Further, we observed a significant effect of SDO, t(854) = 8.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.42, 0.68), which was qualified by a significant interaction between SDO and structural racism beliefs, t(854) = 2.96, p = 0.003, 95% CI (0.03, 0.17). As depicted in Figure 3, and consistent with Studies 1 and 2, our planned contrasts revealed that holding a more structural racism lay belief was associated with less support for punitive measures among the more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(854) = −2.31, p = 0.02 95% CI (−0.35, −0.03). Among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), however, structural racism beliefs were not associated with support for punitive measures, t(854) = 1.30, p = 0.19, 95% CI (−0.06, 0.27). Further, we observed neither an interaction between SDO and disparity exposure, t(854) = −0.11, p = 0.91, 95% CI (−0.13, 0.11), nor a three-way interaction between racism lay beliefs, SDO and the disparity exposure manipulation, t(854) = −1.73, p = 0.08, 95% CI (−0.13, 0.01).

Figure 3. Interaction of racism belief and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) on support for punitive measures in Study 3. SDO plotted at ± 1 SD above or below the mean.

Concern about crime

We submitted crime concerns to the same regression outline previously, which revealed no effect of the racial disparity manipulation, t(854) = −0.83, p = 0.41, 95% CI (−0.13, 0.05), structural racism beliefs, t(854) = 0.62, p = 0.55, 95% CI (−0.05, 0.10), or the interaction between the racism disparity manipulation and structural racism beliefs, t(854) = −1.69, p = 0.09, 95% CI (−0.12, 0.01).

We did, however, observe a significant main effect of SDO, t(854) = 4.37, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.09, 0.24), which was qualified by a significant interaction between SDO and structural racism beliefs, t(854) = 3.38, p = 0.001, 95% CI (0.03, 0.10). Interestingly, in contrast with Studies 1 and 2, our planned contrasts revealed that holding a more structural belief was not associated with concern about crime among the more egalitarian participants (−1 SD below the mean on SDO), t(854) = −1.60, p = 0.11 95% CI (−0.17, 0.02), although the pattern was in the predicted direction. Among the less egalitarian participants (+1 SD above the mean on SDO), however, structural racism beliefs were associated with greater levels of crime concern, t(854) = 2.51, p = 0.01, 95% CI (0.03, 0.21). The interaction of SDO and the disparity exposure manipulation was not significant, t(854) = −0.66, p = 0.51, 95% CI (−0.09, 0.05), nor was the three-way interaction between structural racism beliefs, SDO and the disparity exposure manipulation, t(854) = −1.26, p = 0.21, 95% CI (−0.06, 0.01).

Discussion

Building upon the previous studies, Study 3 provides further evidence that beliefs about the structural nature of racism predict responses to racial inequality in the criminal legal system. Indeed, individuals with a more structural understanding of racism tended to express lower support for a variety of punitive carceral policies. Moreover, like in Studies 1 and 2, it was primarily among participants with more egalitarian ideals (i.e., those low in SDO) that holding a relatively structural view of contemporary racism was associated with the lowest support for punitive policies.

Interestingly, and in contrast with Study 2, the interaction between structural lay beliefs and SDO had different implications for participants' crime concerns. Rather than greater structural beliefs and lower levels of SDO predicting the least crime concerns, as in Study 2, we found that Study 3 participants with greater structural beliefs and higher levels of SDO showed the greatest crime concerns. This unexpected finding suggests further work will be necessary to understand how, and perhaps when, structural beliefs and SDO interact at higher and lower levels of each construct to predict beliefs about crime. Indeed, believing both that racism is largely structural, and group-based hierarchy is ideal, may even reflect a preference for structural racism, a view which certainly has troubling historical (e.g., Jim Crow segregation; South African Apartheid) and contemporary (e.g., modern White nationalist movements) analogs. Nevertheless, these results offer yet further evidence that it is the combination of holding a relatively structural understanding of racism and preference for societal egalitarianism that predicts concern about racial inequality in the criminal legal system.

In Study 3, we aimed to further examine the role of exposure to racial disparity information in shaping subsequent support for carceral policies, though the present findings were ambiguous. In contrast with Study 2, we found an effect of exposure to the racial demographics of the prison system, but only on one of the two dependent measures assessed, and the effect was in the opposite direction as anticipated, and past research (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014) would suggest. Namely, we found that participants exposed to the racial demographics of the prison system showed less support for punitive carceral measures, compared with participants who did not view any racial demographic information. Moreover, unlike in Study 2, we did not observe a significant three-way interaction of exposure to disparity information, racism lay beliefs and SDO on support for punitive measures or crime concerns. Given these equivocal results, it is still unclear as to whether (or if) exposure to racial disparity information is either necessary or sufficient to differentially affect support for punitive policies driving racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Future research is needed to elucidate the role of exposure to disparity information in these outcomes.

General discussion

The present research examined the relevance of lay beliefs about the interpersonal and/or structural nature of racism, and degree of preference for social hierarchy (i.e., SDO), in predicting how White Americans perceive and respond to racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Across all three of our studies, and consistent with past research (e.g., Unzueta and Lowery, 2008; Nelson et al., 2013), we found that White American participants tended to hold a more interpersonal (and less structural) understanding of racism. Beyond documenting White Americans' relative lack of acknowledgment of structural racism, however, we also sought to investigate whether lay beliefs about racism, in conjunction with SDO, predict responses to evidence of racial inequality in the U.S. prison population.

Specifically, in Study 1, building from past research (Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014), we presented White Americans with demographic information about the national prison system, differentially presenting the racial disparity as relatively less-pronounced (40% Black) or quite stark (60% Black), prior to assessing participants' support for habitual offender laws, policies which contribute to racial disparities in incarceration (e.g., Alexander, 2010). We also measured participants' endorsement of an interpersonal or structural understanding of racism, and levels of SDO, as potential moderators the effect of disparity exposure. To our surprise, and contrary to past research (i.e., Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014), we did not observe an effect of exposure to different levels of racial disparity on participants' punitive attitudes in this Study.

Study 1 did suggest, however, that lay beliefs about racism, coupled with individual differences in social dominance orientation, predict responses to exposure to racial disparities in incarceration, irrespective of their magnitude. Specifically, among participants with more egalitarian attitudes regarding societal inequality (i.e., those lower in SDO), holding a relatively structural, rather than interpersonal, racism lay belief was associated with lower support for habitual offender laws, and lower crime concerns, after exposure to information about the racial demographics of the prison population. Among participants with relatively high levels of SDO, in contrast, racism lay beliefs were not related to support for habitual offender laws.

In Study 2, we further investigated the role of exposure to disparity information with a more conservative test: participants were either exposed to evidence of racial disparities in the U.S. prison system, or they were not exposed to any racial disparity information at all. We again measured participants' endorsement of a structural understanding of racism, and levels of SDO, as potential moderators the effect of disparity exposure. In contrast with Study 1, but consistent with past research, we found that participants exposed to racial disparities in U.S. prisons showed significantly more punitive policy support, compared with those who did not view any racial disparity information. Consistent with Study 1, we also found an interaction of structural racism beliefs and SDO, such that it was only among participants with lower levels of SDO that holding a relatively structural racism view predicted less punitive policy support and crime concerns. Notably, however, we only observed this interaction among participants who were exposed to evidence of racial disparities in the U.S. prison system (vs. those who were not exposed to racial disparity information).

Consistent with Studies 1 and 2, in Study 3 we again found that the combination of holding a relatively structural understanding of racism and a lower level of SDO predicted lower support for a variety of punitive carceral policies. Surprisingly, and contrary to predictions, we also observed that those with a more structural racism view and higher levels of SDO showed greater crime concerns. However, the effect of exposure to disparity information differed from our predictions and the findings from previous research. Indeed, we found that White American participants who were exposed to evidence of racial disparities in the U.S. prison system showed less support for punitive policies, relative to those who were not exposed to racial disparity information. Also, contrary to our findings from Study 2, this effect of racial disparity exposure did not operate in tandem with structural racism beliefs and SDO to predict punitive policy support. Although the impact of exposure to disparity information remains unclear, in all, the results of all three studies suggest that the combination of preference for societal egalitarianism, in general, and a structural understanding of racism are important in accounting for carceral policy preferences and crime concerns. Taken together, the present work speaks to the relevance of lay beliefs about the nature of racism in predicting both the perception of and responses to racial inequality in the criminal legal system.

Implications

The findings of the present work offer several theoretical and practical implications for research on how people perceive and reason about racial inequality. Namely, this work suggests an important, albeit largely overlooked, potential role of individual differences in beliefs about the nature of racism in helping to explain how White Americans respond to evidence of racial inequality. Indeed, a well-established, a highly influential body of social science research has thoroughly examined the differing implications of person-level (e.g., lack of effort), and system-level (e.g., discrimination) attributions for societal inequality (e.g., Kluegel and Smith, 1986). We contend, however, that much of this work has not disambiguated the potentially divergent implications of attributing inequality to different types of discrimination (e.g., interpersonal and/or structural racism; Rucker and Richeson, 2021). The present work makes the case that White Americans' lay beliefs about the structural nature of racism are relevant to their perceiving, and perhaps acknowledging, the prevalence of racial injustice in contemporary society (see also Salter et al., 2018).

Indeed, evidence from our three studies suggests that, among White American participants, a more structural understanding of racism, in combination with a lower degree of preference for societal group-based hierarchy, is associated with greater skepticism about harsh carceral policies. Yet the impact of exposure to actual evidence of racial inequality (i.e., statistics concerning racial disparities in the U.S. prison population) remains unclear. Future research should further examine the effects of different manipulations of racial disparity information to continue to elucidate the potential impact (if any) of this information on responses to societal inequality or the influence of other demographic disparities in the carceral population (e.g., the disproportionate representation of men, relative to women). Moreover, future research is needed to examine how different methods of communicating disparity information may shape how people respond to it and, of course, whether individual differences in lay beliefs and SDO moderate those responses.

Together, our findings across three studies suggest that variance in how White Americans conceptualize racism predicts how they respond to (and, presumably, reason about) racial disparities. In other words, the present research suggests that, in addition to measuring more general egalitarian beliefs, considering how people tend to conceptualize racism—as relatively more interpersonal or structural—can shed new light on how they evaluate racial disparities. This reasoning, in turn, contributes to peoples' support for efforts to reduce discriminatory laws and policies that contribute to the maintenance and/or exacerbation of racial disparities in any number of domains. Given the ubiquitous endorsement of an interpersonal view of racism in the United States, among the general public and within the social psychological literature (e.g., Adams et al., 2008; Salter et al., 2018; Rucker and Richeson, 2021), it is likely that current social-psychological models regarding how Americans respond to racial inequality may obscure important and divergent patterns of responses found only among individuals with a more structural, rather than interpersonal, understanding of racism.

In terms of its practical implications, the present research suggests that promoting a more structural understanding of racism, at least among individuals most concerned about societal stratification, may temper support for policies that contribute to racially disparate criminal legal outcomes. Moreover, our work adds further evidence suggesting that mere exposure to evidence of societal racial disparities does not, in itself, lead to broader support for their abolition (e.g., Hetey and Eberhardt, 2014, 2018). For advocates interested in increasing awareness of racial disparities to galvanize broader motivation in reducing them, our research suggests that awareness may need to be coupled with an effort to highlight how social structures can (unjustly) perpetuate such disparities.

Limitations and future directions

There are several noteworthy limitations of the present research that should be addressed in future research. For instance, future work will be necessary to identify the most robust way of measuring lay beliefs about the interpersonal and structural nature of racism. This effort would help to disambiguate the construct from related, but distinct, constructs (e.g., the denial of the existence of racism, in general). Although our findings were largely consistent across studies, despite notable differences in our measures, future research will benefit from further refining the measure of these constructs and, ultimately, performing a more thorough construct validation.

Furthermore, future work should examine whether the implications of a structural understanding of discrimination generalize to other domains (e.g., racial economic inequality) and types/targets of discrimination (e.g., sexism, classism). Also, given research suggesting malleability of these racism lay beliefs (e.g., Adams et al., 2008), future work should examine the causal implications of a structural understanding of racism on perceptions of and responses to societal racial inequality.

Finally, it will be critical for future research to further elucidate how beliefs about structural discrimination may inform how members of marginalized groups experience, cope with, and organize to resist their societal oppression. For instance, previous research has found evidence of a relationship between beliefs about structural discrimination and positive mental health outcomes (e.g., Utsey et al., 2000), as well as greater interest in collective action and political engagement (e.g., Anyiwo et al., 2018; Bañales et al., 2020). It will also be critical to continue elucidating the role of lay beliefs about the nature of discrimination in shaping the experiences and outcomes of members of subordinated groups.

Conclusion

Although there is much to be learned about how lay beliefs shape responses to racial disparities, the evidence amassed in the present research offers encouraging implications for both psychological theory and social change. Given the obstinacy of racial inequality in the United States, and throughout the world, a more complete understanding of the factors that shape perception of and reactions to these disparities will be crucial in both advancing academic discourse on racial inequality and stratification. This work will also be critical in creating effective interventions to galvanize broader support for reducing racial inequality, in the criminal legal system and beyond.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://osf.io/54v3x/?view_only=e5de5bf7d9b04afdb940b6b16a6344a1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Northwestern University Institutional Review Board, Yale University Institutional Review Board, UNC-Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions