Unveiling the Research Landscape of Sustainable Development Goals and Their Inclusion in Higher Education Institutions and Research Centers: Major Trends in 2000–2017

- 1Department of Industrial Management, Industrial Design and Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Sustainable Development, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

- 2Department of Biology, Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM), Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

- 3Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

- 4Life Quality Research Centre, Polytechnic Institute of Santarém, Santarém, Portugal

- 5Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS), Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 6Department of Science and Innovation-National Research Foundation of South Africa Centre of Excellence in Scientometrics and STI Policy (SciSTP), Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) have become the international framework for sustainability policy. Its legacy is linked with the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), established in 2000. In this paper a scientometric analysis was conducted to: (1) Present a new methodological approach to identify the research output related to both SDGs and MDGs (M&SDGs) from 2000 to 2017, with the aim of mapping the global research related to M&SDGs; (2) Describe the thematic specialization based on keyword co-occurrence analysis and citation bursts; and (3) Classify the scientific output into individual SDGs (based on an ad-hoc glossary) and assess SDGs interconnections. Publications conceptually related to M&SDGs (defined by the set of M&SDG core publications and a scientometric expansion based on direct citations) were identified in the in-house CWTS Web of Science database. A total of 25,299 publications were analyzed, of which 21,653 (85.59%) were authored by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) or academic research centers (RCs). The findings reveal the increasing participation of these organizations in this research (660 institutions in 2000–2005 to 1,744 institutions involved in 2012–2017). Some institutions present both a high production and specialization on M&SDG topics (e.g., London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and World Health Organization); and others with a very high specialization although lower production levels (e.g., Stockholm Environment Institute). Regarding the specific topics of research, health (especially in developing countries), women, and socio-economic issues are the most salient. Moreover, it has been observed an important interlinkage in the research outputs of some SDGs (e.g., SDG11 “Sustainable Cities and Communities” and SDG3 “Good Health and Well-Being”). This study provides first evidence of such interconnections, and the results of this study could be useful for policymakers in order to promote a more evidenced-based setting for their research agendas on SDGs.

Introduction

Increasing Awareness-Building in Sustainable Development Goals

Sustainability goals have emerged as a global strategy to solve critical world problems, as a result of the global environmental concerns that started in the 1970s. The origin of the notion of sustainable development can be traced back to its most-recognized milestone in 1987; the definition of Sustainable Development in the Brundtland Report1. Afterwards, different summits and conferences were held in which sustainability and sustainable development were the core discussions (e.g., Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992). During these early years, sustainable development was a guiding principle to bridge the North-South division (Siegel and Bastos Lima, 2020). However, what was meant by development was replete with competing ideas about its essential aims, together with various theories about its achievement (Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019). In this context, development goals became an unprecedented effort to bridge those divides and find common ground “with a set of ideas as the consensus global norm concerning both the ends and the means of development” (Fukuda-Parr, 2019). These development goals (MDGs and SDGs) are designed with the same principles: (1) Statement of a social political priority (goal); (2) Time-bound quantitative aspect to be achieved (target); and (3) Measurement tools to monitor progress (indicator) (Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019). The goals represent international agreements that create narratives and frame debates about the conceptualization of development challenges (Fukuda-Parr, 2019). It can be argued that the influence of these goals on policy, governments, and other societal stakeholders is mainly driven by their compelling discourse.

The First Development Goals: Millennium Development Goals

In 2000 eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were created at the Millennium Summit, with the ambition of their being achieved by 2015. These MDGs tackled topics such as extreme poverty and hunger, child mortality, and maternal health2. They represented an unprecedented effort to tackle the needs of the world's poorest countries. However, MDGs were criticized for: (1) Not being adequately aligned “with human rights standards and principles;” (2) Being formulated in a top-down process, only driven by international organizations and developing country governments; (3) Lacking accountability mechanisms; and (4) Omission of important priorities, i.e., inequality (International Human Rights Instruments, 2008; Fukuda-Parr, 2016, 2019). Another criticism of the MDGs was that they had unsuccessful effects in some important regions, such as Africa (Easterly, 2009). Despite these criticisms, although indeed not all goals were achieved by 2015, some progress was acknowledged (United Nations, 2015a). For instance, “the number of people living in extreme poverty has declined by more than half since 1990 and the literacy rate among youth aged 15–24 has increased globally, from 83% in 1990 to 91% in 2015” (Ki-Moon, 2015).

The Present: The Sustainable Development Goals

In 2012, the Conference Rio+20 adopted a 15-year plan called Agenda 2030 (2015–2030), targeting sustainable economic growth, social development, and environmental protection (United Nations, 2015b). As a result, Agenda 2030 established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a deadline in 2030. This agenda was settled as a normative shift (Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019) and has even been institutionalized as a policy paradigm (Siegel and Bastos Lima, 2020). The agenda has 169 targets and various indicators for monitoring their achievement. The topics of these goals cover five critical areas (the so-called 5 P's); People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership (United Nations, 2015b). While MDGs encompassed the notion of development as the North-South project to meet basic needs to end poverty, SDGs reconceptualised development as the “universal aspiration for human progress that is inclusive and sustainable” (Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019). Different from the MDGs, the SDGs pay an increased attention to the interlinkages among different sustainability dimensions and give great attention to inclusiveness; clearly captured in their motto “No one left behind” (Siegel and Bastos Lima, 2020). In practical terms, SDGs expand with respect to MDGs in: (1) Scope (e.g., there are new goals); (2) Reach (involving developed and developing countries); and (3) Engagement of a larger set of societal actors (e.g., citizen councils) in both their creation and implementation (Fisher and Fukuda-Parr, 2019). However, no specific mechanisms to ensure their applicability across different countries have been settled. One of the main concerns is that SDGs rely on individual countries and the goodwill of their governments on how to pursue and implement each of the goals. In this regard, Siegel and Bastos Lima (2020) pointed out that actual SDG-driven transformations depend on the political context of each country, particularly on how these goals are interpreted and prioritized at the national level. These authors even remarked that despite the very concrete formulation of SDGs, their conceptualization (and we could add, their operationalization) still leaves room for interpretation. Thus, the pursuing of some specific goals over others by some countries is known as “cherry-picking,” although quite often interpreted as conformity with the whole agenda (Forestier and Kim, 2020). However, the aim of Agenda 2030 and its accomplishment is fundamentally based on the integrative and indivisible nature of the goals (United Nations, 2015b), therefore “cherry-picking” should not be an acceptable approach, bringing attention to the relevance of monitoring the engagement and consecution of all SDGs by all countries.

The Role of Monitoring the Achievement of SDGs

In contrast to MDGs, monitoring became a key issue for SDGs. Since the launch of SDGs, an SDG Index3 has been developed, aiming to evaluate the achievement of each goal across all countries. The SDG index allows identifying priorities for action, support discussions, and debates to identify gaps in the development of the goals. A preliminary set of 330 indicators was introduced in March 2015 (Hák et al., 2016), but only 232 indicators were adopted. This is different from MDGs, in which indicators were only decided on an internal basis4. The development of indicators to monitor the achievement of SDGs was based on two parallel processes: (1) Multi-stakeholder public consultation led by the UN General Assembly Open Working Group on SDGs (established in 2013); and (2) Intergovernmental negotiations. Moreover, the indicators developed “come from a mix of official and non-official data sources” (e.g., the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, among others), all subjected to an extensive and rigorous data validation process [Sachs et al., 2018, 2019]. However, it has been argued that the translation of goals into quantitative indicators can “distort” their meaning, since indicators can be reinterpreted or used to create perverse discourses or incentives (Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019).

Interlinkages Among SDGs

Another distinctive aspect of SDGs in contrast to MDGs is the role of the relationships and interlinkages among the different goals. Several studies already analyzed the interlinkages and interdependencies between pairs of SDGs, both across or within SDGs, particularly regarding the effects that achieving one goal may have on the ability to achieve others. Pradhan et al. (2017) analyzed the synergies (i.e., progress in one goal favors progress in another) and trade-offs (progress in one goal hinders progress in another) within and across SDGs. They found that SDG1 “No poverty,” or SDG3 “Good health and Well-being” have synergetic relationships with many goals, while SDG12 “Responsible consumption and production” is associated with trade-offs as it has negative correlations with 10 other goals based on the data pair analysis. Later, Lusseau and Mancini (2019) analyzed how key synergies and trade-offs between SDG goals and targets, based on the World Bank categories data, vary with respect to a country's gross national income (GNI) per capita. They highlighted that SDG10 “Reduce Inequalities,” SDG12 “Responsible Consumption and Production,” and SDG13 “Climate Action” are the most central ones, interacting negatively (according to the negative strength value calculated in their study) with many other SDGs (for example in high-income countries SDG12 and SDG13 are antagonistic, based on the Laplacian graph and the eigenvalue centrality value). These kinds of conflicting relationships between SDGs suggest a need for differentiated policy priorities between countries as they progress toward the 2030 Agenda. Kroll et al. (2019) also analyzed trade-offs and synergies between goals and future trends until 2030 based on the SDG index data. They found positive developments with notable synergies in some goals (i.e., SDGs 1, 3, 7, 8, 9), despite others presenting trade-offs (i.e., SDGs 11, 13). There are also other studies that analyzed these interlinkages from a qualitative perspective (Singh et al., 2018; Fuso Nerini et al., 2019; Vinuesa et al., 2020). Particularly relevant for this study is that to date, there are no global studies on the interrelations among SDGs related to the research output of Higher Education Institutions to the best of our knowledge, a gap that this study intends to fill.

Development Goals and Their Relationship With Higher Education Institutions and Research Centers

As discussed above, MDGs and SDGs appeared as a result of the interest and commitment of governments of countries from all over the world toward sustainable development. As Caiado et al. (2018) stated, “The SDG agenda calls for a global partnership—at all levels—between all countries and stakeholders who need to work together to achieve the goals and targets, including a broad spectrum of actions such as multinational businesses, local governments, regional and international bodies, and civil societal organizations.” In this regard, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and Research Centers (RCs) should play an active and central role in promoting and participating in these new goals.

In the past, HEIs played a role in “transforming societies and serving the greater public good, so there is a societal need for universities to assume responsibility for contributing to sustainable development” (Waas et al., 2010), and HEIs “should be leaders in the search for solutions and alternatives to current environmental problems and agents of change” (Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014). For Bizerril et al. (2018), the knowledge of sustainability in HEIs should be encouraged worldwide and especially those located in regions with serious social and environmental challenges. In this sense, researchers must discuss how to cooperate and to share knowledge for a sustainable society, and HEIs could respond to sustainability through cooperation. According to Lozano et al. (2015), HEIs (and in extension, RCs) could tackle sustainable development from the following initiatives: (1) Institutional frameworks (i.e., HEIs commitment with vision, missions, SD office…); (2) Campus operations related to the physical built environment (e.g., energy use and energy efficiency, waste, water and water management); (3) Education (e.g., courses on sustainable development); (4) Research (e.g., research centers, publications, research funding); (5) Outreach and collaboration (e.g., exchange programmes for students in the field of sustainable development); (6) Sustainable development through on-campus experiences; and (7) Assessment and reporting. Despite all these aspects, as Caeiro et al. (2013) study stated, only a few institutions follow a holistic implementation, in which sustainable development is applied in all traditional sustainability dimensions via its inclusion in social, economic, and environmental pillars.

The Role of Scientific Research in the Achievement of SDGs

Scientific research is one of the most relevant dimensions in the effective achievement of SDGs and Agenda 2030. According to Tatalović and Antony (2010) science did not factor strongly in the discussions on how to achieve MDGs goals. However, Leal Filho et al. (2017) see SDGs as an opportunity for scientific research to contribute to the achievement of the goals. For Leal Filho et al. (2018), development goals are an opportunity to encourage sustainability research through interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research. Several authors also support the important role of scientific research to achieve SDGs (Wuelser and Pohl, 2016), namely as a way to solve concrete social problems, while sustainability science5 could support the transition for sustainability. Yet, to our knowledge, no large-scale study has sought to investigate which SDGs are prioritized in the research by HEIs at a global level. The ambition of this study is precisely to fill this gap by providing a global mapping of research topics related to SDGs, identifying who the main contributing HEIs to this research are.

Scientometric Analyses of SDGs-Related Research Outputs From HEIs

Scientometrics is a research area focused on studying research activities (e.g., production, evolution, collaboration, impact, etc.) in order to understand the scientific dynamics across subject areas, institutions, or countries. Scientometric studies offer a powerful tool to generate global pictures of the research activities in a given area. There are different scientometric studies that previously analyzed sustainability, sustainable development or sustainability science based on a keyword search (Nučič, 2012; Schoolman et al., 2012; Hassan et al., 2014; Kajikawa et al., 2014; Pulgarin et al., 2015; Ramírez Ríos et al., 2016; Olawumi and Chan, 2018). Some studies focused on analyzing the output of sustainability in higher education (Bizerril et al., 2018; Veiga Ávila et al., 2018; Alejandro-Cruz et al., 2019; Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop, 2019). However, few studies have specifically analyzed scientific output on SDGs, probably due to the intrinsic difficulty in determining the contributions of science to SDGs (Armitage et al., 2020).

Despite these difficulties, some studies have already tried to analyze the interrelations among SDGs (Le Blanc, 2015; Griggs et al., 2017). Körfgen et al. (2018) analyzed the contribution of Austrian universities toward SDGs. Sweileh (2020) analyzed 18,696 publications from Scopus by searching the term “sustainable development goal.” Another study (Nakamura et al., 2019), analyzed 2,800 publications (with an expansion to 10,300), developed topic maps from the publications identified. One of the authors of this paper had already carried out a preliminary scientometric study (Bautista-Puig and Mauleón, 2019) by analyzing the core of scientific publications on MDGs and SDGs (n = 4,532) in addition to the interrelations between different SDGs from a scientometric point of view. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has approached a large-scale study of MDGs and SDGs relations from a scientometric point of view, considering the role of Higher Education Institutions and Research Centers in the production of research around MDGs and SDGs.

The development of these types of studies is paramount in order to assess and understand their potential limitations and robustness (Rafols, 2020), particularly given the increasing number that are starting to use keyword-based scientometric queries, and machine learning approaches (Pukelis et al., 2020) in order to map the contribution of research to the understanding of SDGs (e.g., Elsevier, OSDG tool, STRINGS Project, Dimensions, Aurora Project), and even their impact (e.g., Times Higher Education SDG Impact indicators). Thus, it is important that different methods and approaches are considered and discussed, particularly highlighting their advantages and limitations. This study aims at contributing also to this debate, as well as to provide scientometric evidence on the main research patterns around SDGs, that can help foster the debate on the role of universities to the SDGs goal.

Objectives

The main purpose of this article is to produce a quantitative study of the scientific research on development goals during the period 2000–2017. Our ambition is 2-fold, on the one hand to propose a scientometric method based on citation relations that can be used to identify research conceptually related to MDGs and SDGs (henceforth M&SDGs), and on the other hand to identify and analyze the main institutions involved in the development of M&SDGs-related scientific outputs, as well as to characterize the main underlying topics related to M&SDGs research. The scientometric analysis was guided by three main research questions:

- RQ1: How can M&SDGs research can be scientometrically delineated and collected? This question focuses on applying an advanced citation-based approach to determine what M&SDG-related research is.

- RQ2. How has M&SDGs research carried out by HEIs has developed over time? This question seeks to characterize how the production of research outputs on M&SDGs has evolved over time, with a special focus on its main producers (institutions and countries). The unit of analysis of this study is on HEIs and RCs (hereafter HEIs). For the more specific definition of these terms used in this study, the reader is referred to Supplementary Material.

- RQ3: What are the specific M&SDGs research topics that have been studied by HEIs? This question identifies and characterizes the main research topics studied in the scientific literature produced by HEIs, with a special focus on the interrelations among the 17 SDGs based on the ad-hoc glossary developed by Bautista (2019).

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section includes the methods section. This is followed by the results and discussions, providing answers to the research questions. Finally, the last section presents the main conclusions and suggestions for future research.

Methods

An important methodological difficulty with the definition of M&SDGs research is the discrepancy between what is research related to M&SDGs and what is research on M&SDGs. “Research related to M&SDGs” comprises research that is related to concepts, issues or ideas related to the M&SDGs but without necessarily a direct linkage to the M&SDGs core (e.g., an institution doing research related to malaria prior to the official launch of the SDGs). “Research on M&SDGs” comprises research directly focusing on the concepts, notions and principles of the M&SDGs (e.g., research directly mentioning “Sustainable Development Goal” or citing a paper that does it). In this work we partly incorporate both perspectives. Thus, we consider that a scientific publication is on the M&SDGs if it mentions either the concepts of MDG or SDGS (i.e., core research), or at a minimum cites, or is cited by, the core research. From a conceptual point of view it can be argued that our approach focuses on identifying research conceptually related to the “discourse of development goals,” and more specifically about how this topic has been constructed in the research by HEIs. With this citation-based approach we are providing a focused analysis on the scientific research that has a stronger cognitive6 alignment with the M&SDGs philosophy and aims, thus avoiding the limitations of semantic approaches (e.g., based on keywords), in which different selections of keywords and terms are possible (and potentially questionable—see Rafols, 2020).

The following methodological steps were followed: (1) Formulation of a search strategy to identify the core M&SDGs literature; (2) Expansion of the dataset based on direct citations (cited and citing publications); (3) Data collection refining and information processing; and (4) Development of scientometric indicators.

(1) Formulation of a search strategy to identify the core M&SDGs literature

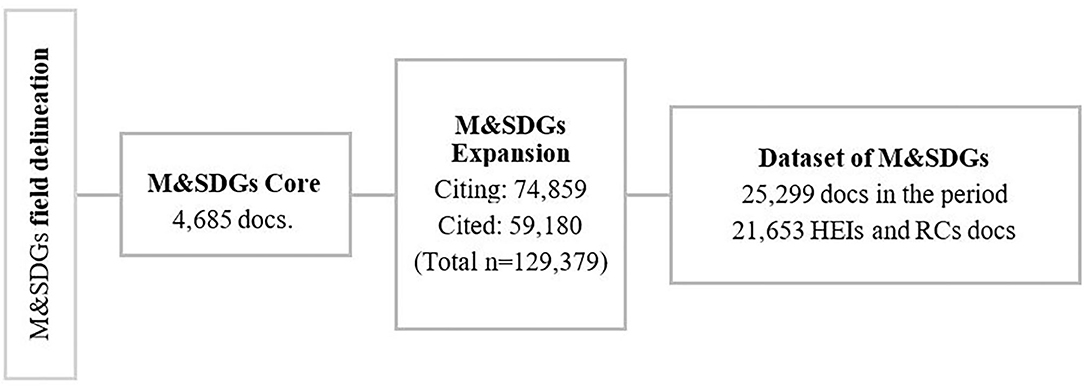

In the first step, we designed a search strategy composed by keywords that unambiguously relate to M&SDGs7. These keywords were searched in titles, abstracts, and keywords (author and paper keywords8). The search strategy was run using the in-house CWTS WoS database (limited to publications from the years 2000–2017). A total of 4,685 publications were collected, and all publication types indexed in the Web of Science were considered. These are considered as the M&SDGs core set of publications.

(2) Expansion of the dataset based on direct citations (cited and citing publications)

Starting from the M&SDG core set of publications (n = 4,685), the set of their direct citations (DC), considering both cited (n = 59,180) and citing (n = 74,859) publications were collected,9 resulting in a final set of distinct publications referred to as M&SDGs Expansion (n = 129,379).

(3) Data collection refining and affiliation information processing

In a following step, a total of 25,299 publications between 2000 and 201710 were selected, excluding 104,080 publications from years outside this period. These publications were further characterized, identifying those publications with at least one affiliation from HEIs (Figure 1), thus conforming the final dataset of analysis, with 21,653 publications (85.59%). The harmonization of the affiliations was based in the in-house CWTS database (Waltman et al., 2012).

Figure 1. Methodological workflow for delineating M&SDGs on this study and creating the final dataset.

(4) Development of scientometric indicators & analytics

The following indicators were analyzed for the final dataset:

(i) Research patterns

- Yearly trend in scientific output in M&SDGs overall and by these institutions. A trend analysis of 6-year blocks is considered.

- Cumulative Average Growth Rate (CAGR). The formula is the following:

Where X1 and Xn are the values found for the first and last periods studied. The expression is equivalent to the compound average growth rate (CAGR) often used in finance to measure mean growth across a time series.

- Output by institutions and countries: Absolute values and “Activity Index” (AI) of their M&SDGs research (Supplementary Equation 1). The AI was proposed by Frame (1977) and it is used to analyze the degree of relative specialization of an actor (institution or country) in a research field. The indicator represents the percentage contribution of each country to the total WoS production, compared to the percentage of contribution in the analyzed topic. ArcGis software was used for creating the maps.

(ii) Subject specialization.

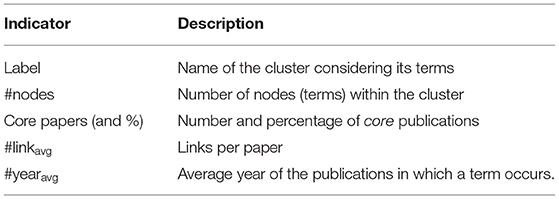

- Co-occurrence map11 based on keywords using the VOSviewer tool12 to identify thematic clusters within the scientific landscape. Regarding the clustering, VOSviewer applies its own algorithm based on modularity optimization (Van Eck and Waltman, 2017). Table 1 summarizes the indicators analyzed.

- Keywords “burst citation.” Burst is a concept associated with a change of a variable's value in a relatively short time. Those sudden increases in the usage frequency of keywords (i.e., burst strength) in order to determine the hotness of a topic were identified using Kleinberg's algorithm (Kleinberg, 2003). This value is not normalized, but the ranking order and the duration of the burst are rather relevant for its interpretation.

- Scientific production classification into the SDGs. In order to study the semantic relations between the different SDGs (in terms of SDGs sharing similar keywords across publications), the individual publications were classified in accordance with the different SDGs. To classify the publications into individual SDGS, an ad-hoc ontology (Bautista, 2019) with 4,122 terms has been applied. Publications were classified in different individual SDGs based on the linkage between the keywords in the publications and the ontology, allowing publications to be classified in more than one SDG when their keywords would point to different SDGs. A total of 20,749 (82.01%) publications were finally classified in at least one of the 17 SDGs. This includes keywords related to each SDG based on the United Nations-Description (e.g., “poverty” was classified into “SDG1-No poverty,” “sanitation” into “SDG6- clean water and sanitation”),13 as well as a manual-supervision of the keywords located as the core and its consequent extension.

Results

In this section the main results of the paper are presented in relationship to the main research questions formulated above.

Research Output and Main Actors

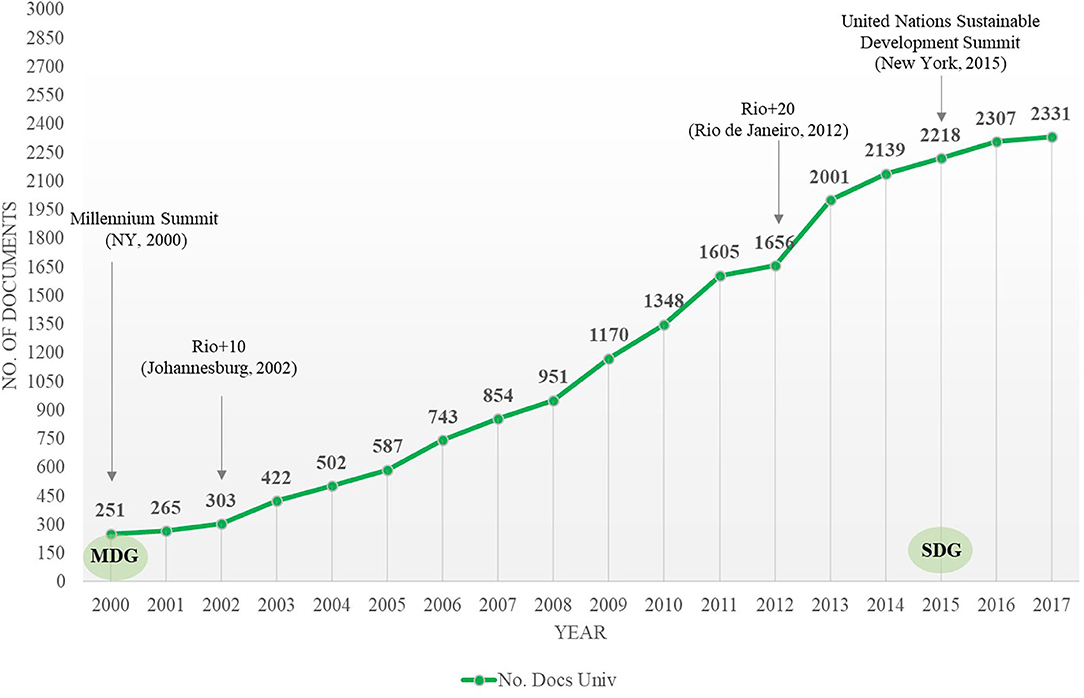

This section analyses the M&SDGs-related research output collected, as well as the main actors producing it and their specialization. Figure 2 presents the evolution of the scientific output of development goals produced. The scientific evolution shows a growing tendency, with an overall growth of 828.65% over the period and a CAGR of 14.01%. Since the launch of the SDGs in 2015, there has been a strong concentration of the M&SDGs research output, with more than 31.6% of the overall output published since the launch of the SDGs in 2015 (until 2017).

A total of 1,968 organizations were identified in the affiliations of these publications. The most productive institution was the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, with 1,963 publications (9.07%), followed by the World Health Organization (WHO), with 1,675 (7.74%), Johns Hopkins University with 1,324 (6.11%) and Harvard University with 1,079 (4.98%). However, when looking at the 6-year blocs as in Supplementary Table 1, different tendencies are shown over time. In the first 6-year (2000–2005) sample, the number of publications was 2,330 produced by 660 organizations identified. The most productive organizations in this period were the WHO, with 292 publications (12.53%), followed by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine with 272 (11.67%) and the Johns Hopkins University with 157 (6.74%). In the second period (2006–2011), a total of 6,671 publications were produced by 1,244 organizations. During this period, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine led the ranking with 682 publications (10.22%), followed by the WHO with 580 (8.69%) and the Johns Hopkins University with 439 (6.58%). In the third period (2012–2017), a total of 12,652 publications, produced by 1,744 organizations, were identified. The same ranking of organizations as in the previous period is also found: The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine leads with 1,009 publications (7.98%), followed by the WHO with 803 publications (6.35%) and the Johns Hopkins University with 728 (5.75%). Among the more productive HEIs there are only five institutions from developing countries: two form South Africa (the University of Cape Town and the University of the Witwatersrand), one from Uganda (Makerere University), one from Pakistan (Aga Khan University), and one from Brazil (the Federal University of Pelotas).

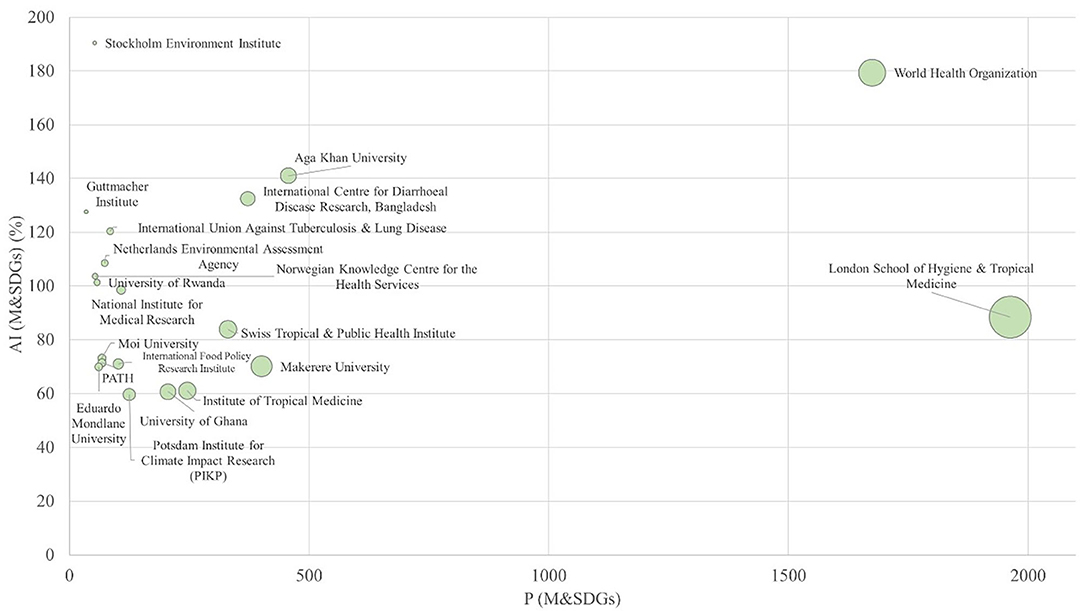

Figure 3 shows a scatter plot of the relation between the institutions with a higher scientific production on SDGs [P(M&SDGs)] and their AI around research on this topic [AI(M&SDG)]. The size of the bubbles indicates the number of publications in WoS of each institution (only institutions with more than 50 are included in the Figure). Overall, the most productive institutions present a lower AI (e.g., the Johns Hopkins University and Harvard University with P(M&SDG) = 1,324 publications and P(M&SDG) = 1,024, respectively, have an AI of 8.70 and 3.89, respectively). The WHO [P(M&SDG) = 1,675] and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine [P(M&SDG)= 1,963] present a high AI of more than 88% each. Among the institutions with the larges AI values we find other institutions such as the Stockholm Environment Institute (AI 190.47), Aga Khan University (AI 141.06), or the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (AI 132.55) (Figure 3).

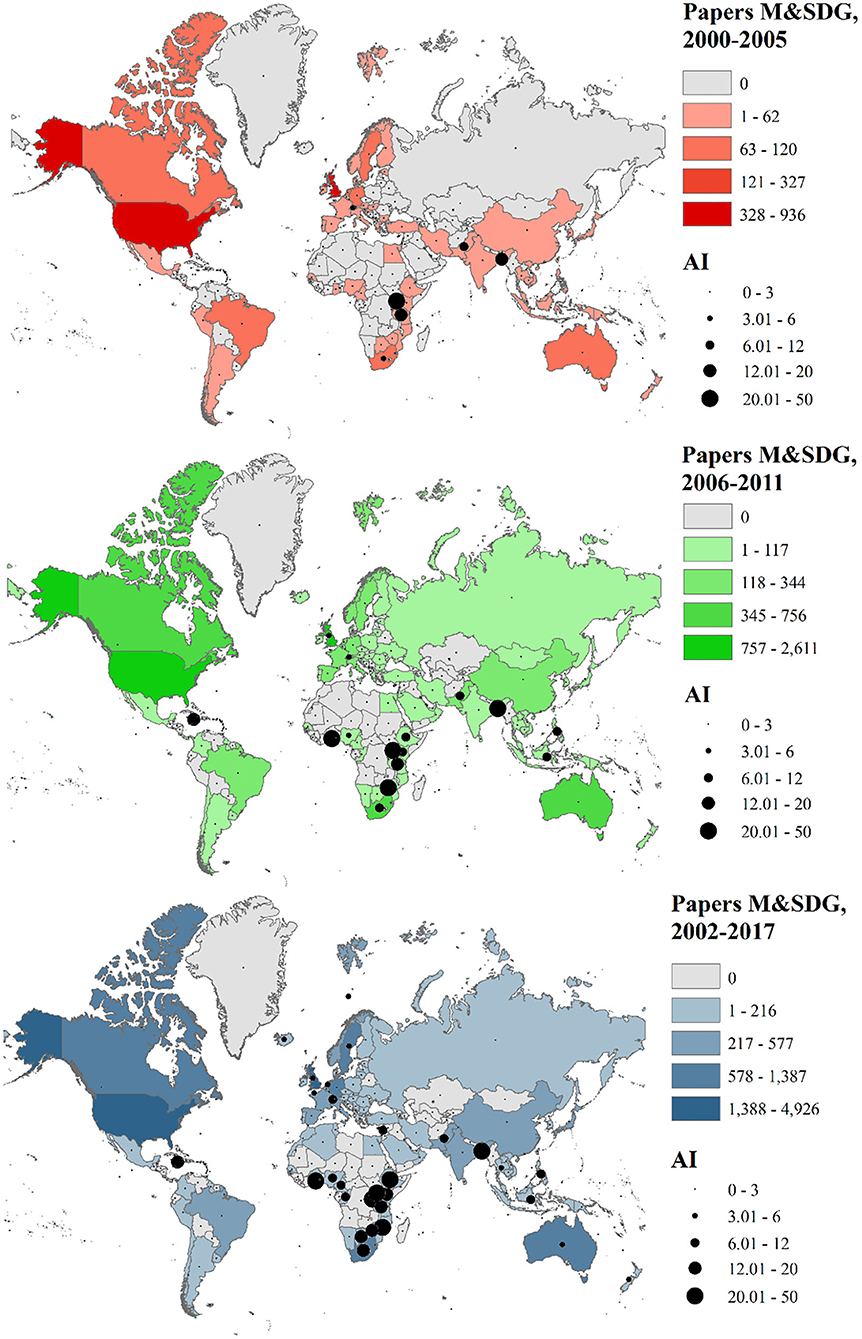

A map is drawn in order to show the geographical distribution of M&SDGs publications (Figure 4). The most productive countries during the whole period were the United States (8,473 publications, 39.13%), followed by the United Kingdom (6,053 publications, 27.95%), Switzerland (2,232 publications, 10.31%), Australia (1,959 publications, 9.05%), and Canada (1,757 publications, 8.11%). By periods, in the first one (2000–2005) a total of 67 countries produced at least one publication on M&SDGs research increasing to 86 countries in the second period, and to 95 countries in the third period, with the same set of countries mentioned above as the most productive in each period (Figure 4). From the point of view of the specialization (measured by the AI), African and Asian countries exhibit a stronger specialization in M&SDGs research compared to countries from other regions. Uganda is leading the specialization in the whole period (29 publications and AI of 24% in the first period: 107 and AI 32.60 in the second period and 265 publications and AI of 43.130 in the third period). Supplementary Table 2 provides information on 6-year blocs to see differences over time. Apart from Uganda, other African countries (Tanzania, South-Africa, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Rwanda, Mozambique, or Ethiopia) stand out in specialization. Besides, other countries from Asia (Bangladesh, Pakistan), or Europe (Switzerland) present a higher AI on the topic.

Figure 4. Geographic distribution of scientific publications and AI (countries with >20 publications).

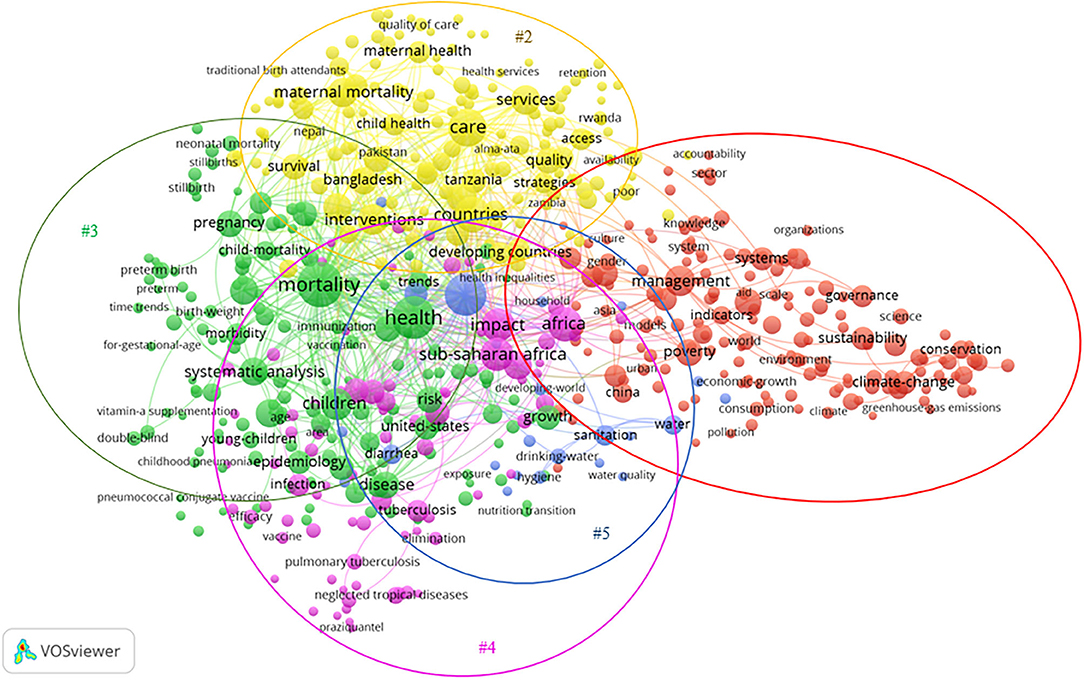

Keyword Co-occurrence Analysis

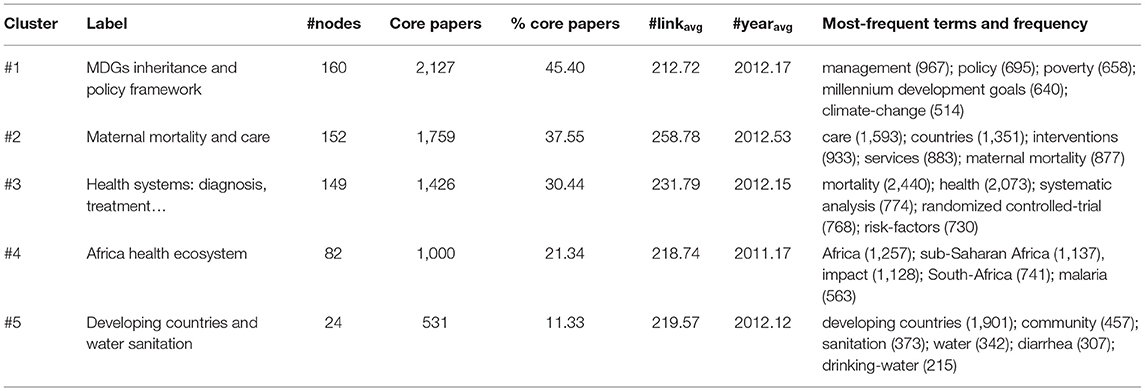

To reveal the main topics of the M&SDGs research, Figure 5 shows a keyword co-occurrence-based clustering. The parameters for creating the maps are detailed below: LingLog Modularity normalization method, 566 items; link of 65,446; link strength of 298,485; and repulsion, resolution and minimum cluster size with a value of 114. Keywords (nodes) in VOSViewer maps are located in such a way that the distance between them is related to their co-occurrence frequency. Terms located closely in the map means that they tend to appear together in the titles and abstracts of the papers, and therefore it can be argued that they are thematically connected. The following five clusters were identified: Cluster #1, with terms related to the millennium development goals inheritance and policy framework; Cluster #2 with terms about maternal mortality and care; Cluster #3 with terms related to the health systems (“diagnosis,” “treatment”); Cluster #4 with terms about the African health ecosystem, and Cluster #5 including terms related to the developing countries' landscape (health, community, water, and so on). Table 2 summarizes the main information of each cluster (number of nodes, core papers, average year, average links, and the most frequent keywords). It can be observed that cluster 1 is the largest in terms of publications, followed by cluster 2. The number of links per paper (#linkavg) is higher in cluster #2 and cluster #3, both related to health issues, suggesting a stronger connection between these two clusters. In most clusters, the average year (#yearavg) is 2012, suggesting that an important share of the output has been developed in the most recent years of study, which is backed up by the growing M&SDGs output over time discussed above. The percentage of core publications (i.e., directly referring to M&SDGs) for each cluster is indicated in the column “% core papers,” showing that clusters #1 and #2 (with 45.40 and 37.55% of core publications, respectively), are clusters with a stronger conceptual proximity with the M&SDGs core ideas and aims, while the other clusters have a more indirect relationship with these core ideas.

Keyword Burst Analysis

In this section, burst detection for keywords in M&SDGs publications is performed in order to show what terms have more rapidly increased attention in citations accumulation. We have identified at least 60 different bursting keywords during the period. Supplementary Table 3 lists the 60 keywords with the strongest citation bursts, along with their strength and time span. The term “middle income country” has the strongest citation burst with a burst strength of 75.13, followed by “tuberculosis” with 66.52 and “maternal health” with 64.98. Some keywords have only been “bursting” at the very beginning of the period (e.g., “low birth weight,” 2000–2003; “economic growth,” 2000–2001; and “rural Bangladesh,” 2000–2001). However, in more recent years, strongly bursting citation keywords include “new-born” (16.65, time span of 2015–2017), “middle income country” (75.13, 2014–2017), “maternal health” (64.98, 2014–2017), and “delivery” (36.38, 2014–2017).

Individual SDGs Analysis

Publication Prevalence

The following SDGs were most prevalently represented in the publications (Supplementary Figure 1): SDG3 “Good Health and well-being,” with 15,963 papers (76.93%); followed by SDG16 “Peace, justice and strong institutions,” with 11,658 (56.19%); SDG11 “Sustainable cities and communities,” with 9,541 publications (45.98%); and SDG10: “Reduce inequalities,” with 6,115 publications (29.47%). On the other hand, the least represented SDGs are: SDG 12 “Responsible production and consumption,” 939 papers (4.51%); and SDG7 “Affordable and clean energy,” with 1,095 (5.26%).

Geographic Distribution

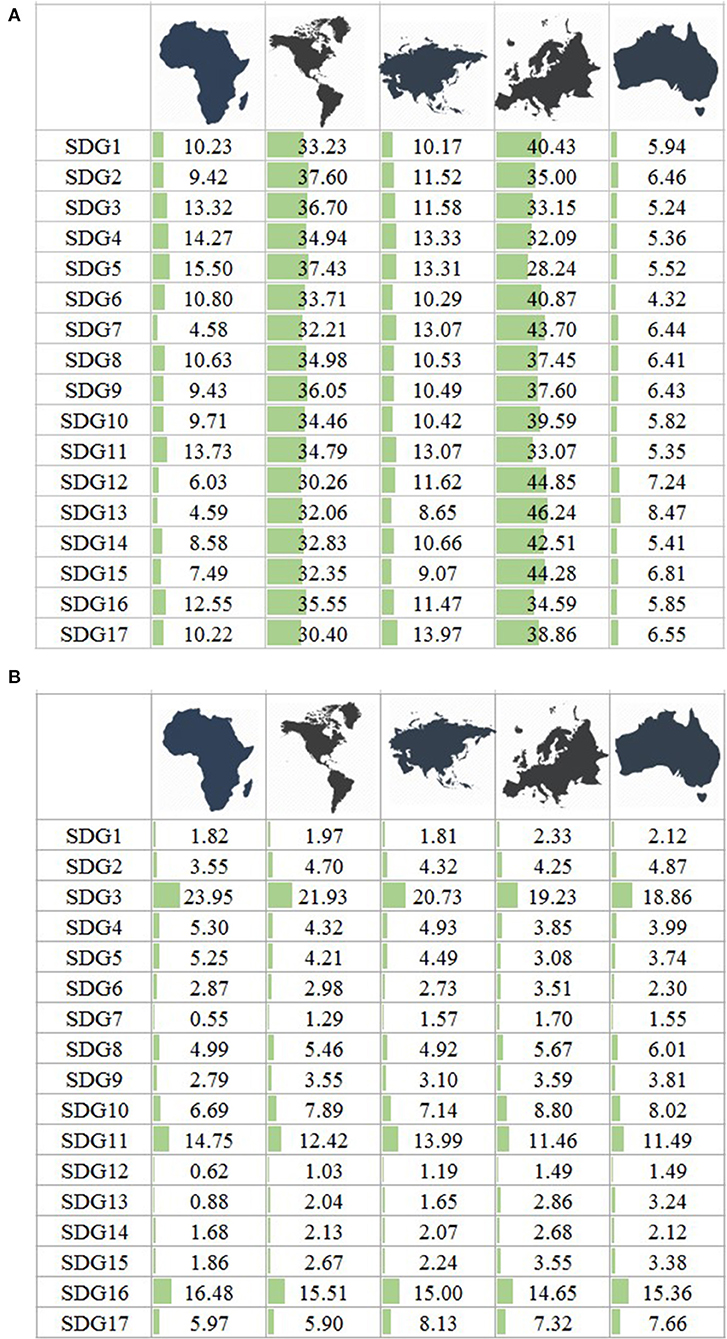

Figure 6 shows two different perspectives on the production of publications across continents related to their contribution to the research of each individual SDG. In Figure 6A, the contribution of each continent to each SDGs is presented (reading row-wise); while the table on the right depicts the share of each continent across the different individual SDGs (reading column-wise). Publications are assigned to each continent based on the affiliation of the first-author of the paper. The results of the left table show that all goals have higher production in Europe and North America. Considering all M&SDGs research, it can be observed that in Europe the largest percentage of output is in SDG13 “Climate action” (46.23%), followed by SDG12 “Responsible Production” (44.85%) and SDG15 “Life on Land” (44.28%). In America, the largest is SDG2 “Zero Hunger” (37.60%), followed by SDG5 “Gender Equality” (15.50%), and SDG3 “Good Health” (13.32%). In Africa, the highest production is in SDG5 “Gender Equality” (15.50%); SDG4 “Quality Education” (14.27%); and SDG11 “Sustainable cities” (13.73%). In Asia, the greatest output is in SDG17 “Partnership for the goals:” (13.97%); SDG4 “Quality Education:” (13.33%); and SDG5 “Gender Equality” (13.31%). Finally, in Oceania, the higher production of these institutions is in SDG13 “Climate Action” (8.47%); SDG12 “Responsible Production and consumption” (7.24%); and SDG15 “Life on Land” (6.81%). From a global perspective, if we consider the distribution of the publications on each goal by continent to determine their profile (Figure 6B), the approach of the different SDGs exhibit more similar patterns, although some SDGs—such as SDG3 “Good Health,” SDG16 “Peace, Justice,” and SDG10 “Reducing Inequalities”—stand out from the others.

Cognitive Relationships

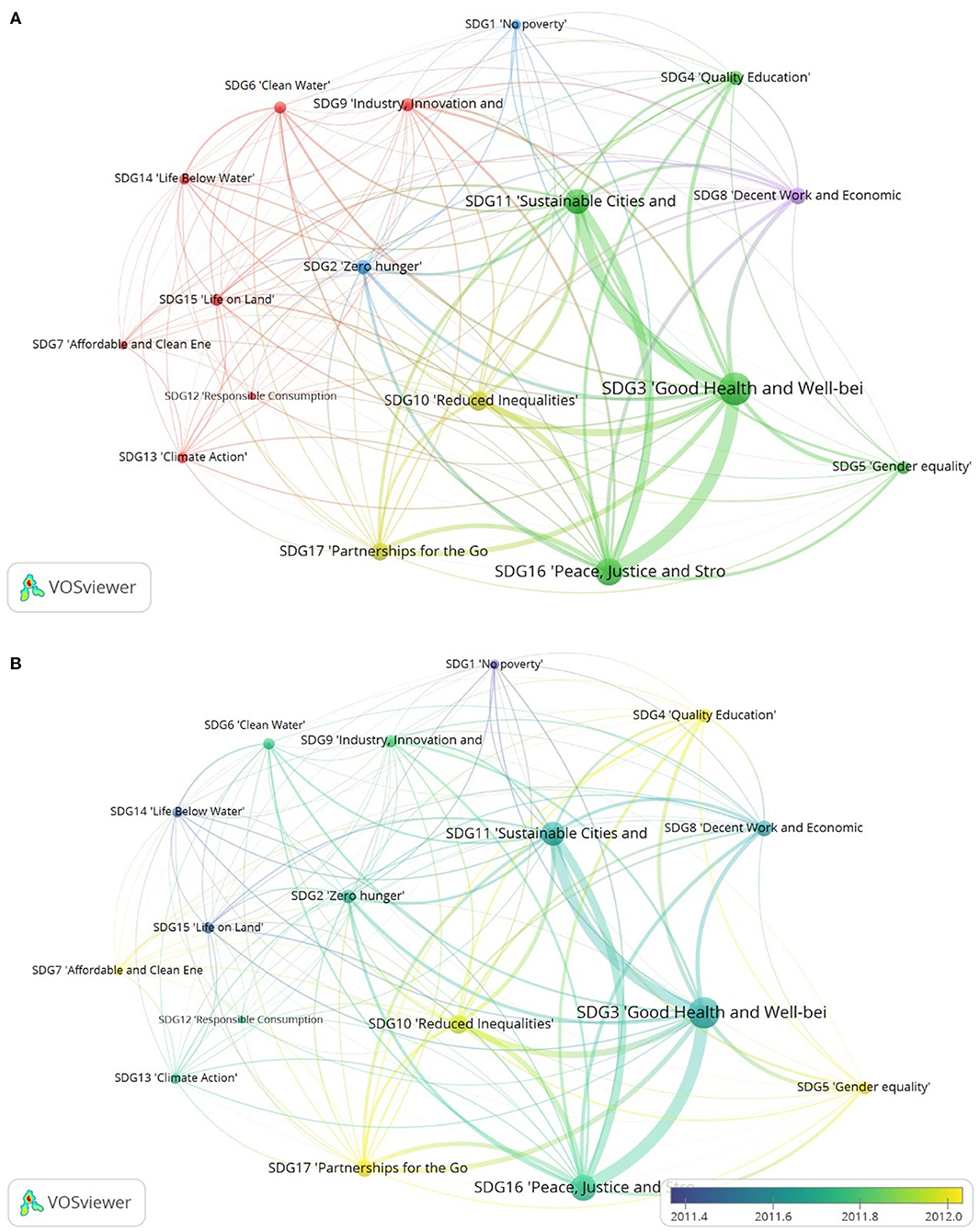

Although the interlinked nature of SDGs has been stressed, their interactions are “not explicit in the description of the goals” (Griggs et al., 2017). For instance, SDG11 “Sustainable Cities,” contains targets related to economic dimensions (e.g., financial and technical assistance for developed countries, expenditure on the conservation of cultural and natural heritage), social dimensions (e.g., number of deaths per disaster and urban population living in slums), or environmental dimensions (e.g., reducing the adverse environmental impact of cities per capita, or the proportion of urban solid waste), and these three could be conceptually linked to other SDGs, for example SDG6 “Clean Water.” In our study, to reveal their cognitive relations (measured via citations), a co-citation map has been created. The proximity between SDGs indicates their similarity in terms of co-citation occurrence (i.e., publications from the two SDGs appear often cited together in the same set of publications). The size of the nodes reflects the frequency of SDGs in terms of overall publications, and the thickness of the edges denotes how often these SDGs are co-cited. Figure 7A shows the SDGs map of the M&SDGs research. The following clusters of SDGs are identified:

Cluster 1 (red) is formed by SDGs with a strong industrial and energy orientation [SDG6 ‘Clean Water’, SDG7 ‘Clean Energy’, and SDG9 ‘Industry, Innovation’] and the environment (SDG15 ‘Life on Land’, and SDG14 ‘Life below Water’). Cluster 2 (blue) groups; SDG1 “No Poverty,” and SDG2 “Zero Hunger,” being two of the most important SDGs inheritance of MDGs. SDG1 is directly and indirectly related to all other SDGs, but dependent on SDG2 International Council for Science, 2015].

Cluster 3 (yellow) includes SDG10 “Reduced Inequalities,” and SDG17 “Partnership for the Goals,” linking the reduction of inequalities and partnership.

Cluster 4 (green) is composed by SDGs related with health, urbanization and peace: SDG3; “Good health;” SDG4 “Quality Education;” SDG 5 “Gender Equality;” SDG11 “Sustainable Cities;” and SDG16 “Peace, Justice.” For instance, SDG11 “Sustainable Cities” and SDG3 “Good Health” have a strong connection (link strength of 5,154).

Cluster 5 (purple) is composed only by SDG8 “Decent work.” However, this goal has links with SDG9 “Industry, Innovation” and SDG11 “Sustainable Cities,” or SDG3 “Good Health,” among others.

Figure 7B depicts the evolution of the SDG in each cluster from the average publication year (2011–2012). The more yellow indicates the more recent the publications. It can be observed how SDG3 “Good Health,” SDG8 “Decent Work,” SDG16 “Peace, Justice”, and SDG11 “Sustainable Cities” have had research output from earlier years, as compared to the other SDGs. From another perspective, SDGs with a stronger recentness in scientific output include SDG17 “Partnership for the Goals,” SDG10 “Reduced Inequalities,” SDG5 “Gender Equality,” and SDG4 “Quality Education,” indicate that awareness of areas related to education or gender are of a more recent nature.

Discussion

The proposal of the different SDGs in 2005 together with Agenda 2030 has led to the creation of a path of collective national and international awareness toward sustainability. One of the main features of SDGs is their increasing relevance not only for policy makers, who are encouraging sustainability-oriented policies, but also for the scientific community as a whole (Kajikawa et al., 2007; Sweileh, 2020). This study presents an empirical scientometric analysis of M&SDGs research, and the role of HEIs in its development. As stated in the literature review, few studies have focused on analyzing the research output of SDGs, and even fewer have focused on the role of the organizations developing such research. Thus, this paper contributes to the debate around the incorporation of the M&SDGs in the research agenda of HEIs by providing an overview of output in the area, and by proposing a practical methodology approach to delineate this area in bibliometric databases.

How Can M&SDGs-Research Be Scientometrically Delineated and Collected?

A well-delineated methodology is crucial to identify the research publications on a specific topic. In this study, we propose a citation-based methodology to track and monitor M&SDGs-related research. The application of our methodology retrieved a total of 25,299 publications, which identifies a much larger set of publications of M&SDGs at HEIs than in similar previous studies (Bizerril et al., 2018; Veiga Ávila et al., 2018; Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop, 2019). The study by Nakamura et al. (2019) used a very similar methodology as the one presented here, however we identified a larger set of publications related to M&SDGs (4,685 in the core and 25,299 in total in the present study vs. the 2,800 in the core and 10,300 total in Nakamura study). The main reason for this difference is that in the present study the MDGs were also considered, as well as the fact that the CWTS WoS version has a more efficient citation matching algorithm than the one in WoS (Olensky et al., 2016). The citation-based approach of this study, as well as in Nakamura et al. (2019), offers some advantages in comparison with previous studies that applied keyword-based approaches (Kajikawa et al., 2007; Elsevier Research Intelligence, 2015). For instance, it offers a systematic approach that can easily be reproduced and can be applied to any other database that records citation linkages among publications (e.g., Web of Science, Scopus, Microsoft Academic Graph, Dimensions, Crossref Open Citations, etc.), making possible the replication of this approach in future studies. Another important advantage of our approach is that it focuses on identifying publications that are cognitively related to M&SDGs, since the selected publications have cited/are citing relationships with the core literature on M&SDGs, thus avoiding the problem of delineating M&SDGs-related research using keywords. Keyword-based approaches would typically identify as SDGs-related research publications that only have a circumstantial relationships with SDGs, but that are not totally related to them (e.g., publications related to “economic growth,” but not in the philosophy underlying the M&SDGs—i.e., sustainable economic growth). Finally, the method developed here has the advantage that it captures the M&SDGs research output at the global level, thus providing an international perspective on the discussion around the study of the research activity on M&SDGs. However, in future studies other more local perspectives (e.g., the study of publications in local languages, local publishers) should be also explored.

How Has M&SDGs Research Carried Out by HEIs Developed Over Time?

The results presented in this study suggest that although one may presume that M&SDGs research would have a long tradition since the launch of the MDGs, there is an important concentration of publications in the most recent years, denoting a more recent interest in the SDGs (21.83% in 2000–2014, the MDGs period vs. 31.66% from 2015 to 2017 since the launch of the SDGs). However, we should take into consideration that by using WoS there is a strong bias toward English-language journals and might have distorted the results. In any case, this recency trend in the production of M&SDGs-related research is in line with the results obtained by Olawumi and Chan (2018) who observed that the scientific output on sustainable development, 2015–2016, represents 36.27% (vs. 21.42% on M&SDGs in the present study). There have also been previous publications discussing the growth of the scientific production related with sustainability. For example, Pulgarin et al. (2015) argued that the growth of research production in sustainability can be explained by “the impact of human activity on the environment” which “is leading to this area of research [sustainability] being studied from ever more different fields.” Olawumi and Chan (2018) consider that this increase could be also linked to “more efforts and resources” being devoted to this topic. For Nučič (2012), the increasing growth of the scientific output could be associated with “sustainability science as a highly interdisciplinary research field.” This is in line with Schoolman et al. (2012), who indicated that “sustainability research is more interdisciplinary than other scientific research” (based on the Shannon entropy measure), supporting the suggestion by Nakamura et al. (2019) that SDGs research is based on “transdisciplinary knowledge” between different fields, arguing that “most scientific disciplines are expected to contribute toward sustainability since in sustainability we have complex structures, including environmental, technological, societal, and economic facets” (Kajikawa et al., 2014).

In previous studies on M&SDGs the role of these institutions has not been specifically analyzed (e.g., in Nakamura et al., 2019). Institutions like the London School of Hygiene, the WHO, and the Johns Hopkins University stand out among the most productive institutions. Their predominant role can be explained by their relatively large sizes; however, their AI confirms that these institutions are also highly specialized on this topic too. The London School of Hygiene belongs to the University of London and is specialized in public health and tropical medicine; while the WHO is a specialized agency of the United Nations focused on international public health. As well, London School of Hygiene have focused recently on health systems' strengthening (HSS) (Seidman, 2017). The predominant role in output and specialization of the WHO, which is not a HEI or a RC but a supra-governmental organization that provides statistics for monitoring health-related aspects of the SDGs,15 may be also seen as a sign of the strong social and political relevance of M&SDGs research.

Some other organizations that, although smaller in terms of output, have a high degree of specialization are the Stockholm Environment Institute (AI 191.47), the Aga Khan University (AI 141.06), or the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (AI 132.55). This relative importance of small organizations goes in line with Nakamura's et al. (2019) results, who suggested that not always the largest institutions “set the agenda” in M&SDGs research, but that smaller ones also could be key players (e.g., Stockholm Environment Institute, and the University of London).

This study confirms the observation by Yarime et al. (2010) of an increasing number of countries engaged in research on sustainability. Our results also resonate with studies like that of Adomßent et al. (2014), who also stated that the HEIs' sustainability research is mostly produced by authors from developed countries such as the USA, the United Kingdom, Australia, or Canada. However, in terms of relative specialization, our study shows that African and Asian countries exhibit a much stronger specialization. A special case is South Africa. This country is the sixth country in number of M&SDGs publications, and one of its universities (i.e., University of Cape Town) is the most prolific African institution in M&SDGs research. This strong relevance of SDGs research in South African can be reinforced by the fact that “South Africa” is a topic in the M&SDGs research map since the name of the country appears as a node in the term co-occurrence map. Although our scientometric evidence is not strong enough to conclude that the higher performance of this country in M&SDGs is the direct effect of policies aimed at encouraging research on M&SDGs, it must be highlighted that the country counts with South Africa's National Development Plan (NDP), which defines national development priorities and provides the foundations for South Africa in order to achieve the SDGs (Cumming et al., 2017).

What Are the Specific M&SDGs Research Topics That Have Been Studied by HEIs?

The SDGs more frequently addressed by HEIs are SDG3 “Good Health” (76.93% of the publications), SDG16 “Peace, Justice” (56.19%), SDG11 “Sustainable Cities” (45.98%) and SDG10 “Reduced inequalities” (29.47%), which is in line with the higher percentage of overall HEIs involved on this research (Supplementary Table 4). Our results contrast with the results obtained by Salvia et al. (2019), who surveyed research experts in SDGs across continents, highlighting the following SDGs as having more activity: SDG 13 “Climate Action” (41%), SDG 11 “Sustainable Cities” (33%), and SDG 4 “Quality Education” (29%). This remarkable difference between a qualitative approach (i.e., surveys sent to experts in Salvia et al., 2019) and our quantitative approach, reinforces the importance of considering and combining different methodologies in the study of how science is contributing to the achievement of SDGs, and how academic stakeholders are approaching the different SDGs.

Regarding the interconnection of SDGs, according to Nilsson et al. (2016), SDGs are more interconnected among themselves than its predecessors, the MDGs. This idea of SDGs interconnecting among themselves is supported by their consideration as “enablers for integration,” which means that the internal structures of the different SDGs is conceived to fit across more different SDGs (Le Blanc, 2015), thus enabling their own integration and interconnection. This integrative and interconnected property of SDGs is observed in this study, since all goals have connections among them, being particularly remarkable the connections between the following three pairs, which presented a higher co-occurrence values: SDG16 “Peace, Justice” vs. SDG13 “Climate Action;” SDG3 “Good Health” vs. SDG11 “Sustainable Cities;” and SDG16 “Peace, Justice” vs. SDG11 “Sustainable Cities.” Moreover, the linkage between the pairs responds to complementary relationships. For instance, SDG3 “Good Health” and SDG11 “Sustainable Cities,” linking health with cities could be understood as housing, transport, and access to green spaces are major determinants of health and well-being (International Council for Science, 2015).

As mentioned above, SDG3 “Good Health” is the most researched SDG identified in our study. This is not a surprise since this goal has a central role in the achievement of sustainable development (Pettigrew et al., 2015), and Biomedical Research is one of the largest research areas covered in Web of Science (Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). In any case, our results are in agreement with (Körfgen et al., 2018; Sweileh, 2020), and as pointed out by previous studies, SDG3 “Good Health” was found to have a higher share of synergies with other SDGs in most countries (Pradhan et al., 2017). The MDGs, experience has shown that without improvements in health systems performance, progress on the goals was both limited and potentially unsustainable (Seidman, 2017). This may explain why this specific health-related goal (SDG3) became more ambitious and central than in the MDGs (Seidman, 2017; Asi and Williams, 2018). It is important to highlight that one the major efforts of SDG3 has been to reduce mortality across population groups (e.g., “the poor” or “women and children”) (Buse and Hawkes, 2015), thus explaining the central role of “good health” in the map of topics presented in this study. However, from our data, there is no empirical evidence suggesting why health is the goal most researched.

Conclusions

Based on an advanced citation-based field delineation, this paper provides an extensive analysis of M&SDGs research over time and contributes to contextualize and understand its trajectory. The results of this study are relevant for planners and decision-makers in HEIs. First, this paper presents a new delineation procedure for M&SDGs-related research. The methodology is simple and reproducible, allowing its application in future studies for researchers, as well as its implementation in other citation databases (e.g., Scopus, Dimensions, Microsoft Academic Graph, etc.). Second, our work contributes to the expansion of the toolset of research instruments aimed at evaluating the development of research around M&SDGs. We provide a relevant proof of concept on how scientometric methodologies can support the monitoring of the research developed to support the achievement of M&SDGs. The approach proposed in this paper has relevance for all stakeholders engaged in the development of research activities related to M&SDGs (e.g., HEIs, RCs, governmental and supranational organizations, NGOs, and any stakeholder interested in SDGs). Developing reproducible methodologies (as done in this paper) and establishing a stable analytical monitoring framework is fundamental for a proper understanding of how science is contributing to the achievement of SDGs. However, it is important, not only to analyze the number of papers, but also the contribution itself of those papers with the goals, targets, and indicators.

From a scientometric point of view, this study provides a novel contribution to the scientometric analysis on SDGs research output, particularly since most scientometric studies have focused on developing semantic approaches, in which the use of keywords has been the most common approximation to the topic (Pukelis et al., 2020; Rafols, 2020). We adopt a citation-based approach. This approach does not suffer from the ambiguity of semantic approaches (e.g., synonymy, homonymy), and more fundamentally, our approach does not hold the limitation that keyword-based approaches may capture research that is not necessarily aligned with the principles and philosophical foundations of M&SDGs. Grounded on the idea that citations represent concept symbols (Small, 1978), in which scientific authors associate ideas by creating symbolic acts with their citations (see also Haustein et al., 2016), it can be argued that our approach captures the body of scientific literature most conceptually related with M&SDGs. To the best of our knowledge, only the Nakamura et al. (2019) study and this one have adopted such a citation-based approach, with this study being the most comprehensive to-date in the body of literature analyzed.

It is important however to remark that our citation-based approach still presents some limitations that must be observed when generalizing its findings. By considering only the Web of Science (WoS) database the study may have limitations due to the underrepresentation of other related published works, which may be indexed in other scientometric databases (e.g., Scopus, Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic…). Also, WoS does not cover all academic fields equally as it presents an underrepresentation of non-English speaking studies. The methodology proposed may not necessarily capture the whole picture of research related to M&SDGs. The sole use of direct citations related to a core set of publications may also be insufficient at times, since many publications genuinely linked to M&SDGs research may be more distanced in their citation relationship with the core set. In addition, despite all types of publications from WoS being included, some other typologies of interest (e.g., governmental reports) are not captured.

Considering the methodological limitations described above, future methodological improvements should take into account the possibility of characterizing not only the directly cited/citing publications of M&SDGs, but also other citation layers (e.g., 2nd, 3rd, or more—also known as citation cascades—Min et al., 2020) in the expansion of the core set of publications. The use of citation cascades would allow the introduction of a more fluid approach (in which a much larger set of scientific publications may be considered regarding their citation proximity to the core set), in contrast with the binary approach (i.e., publication are M&SDGs-related or not) used in this study. Moreover, since this is the first study that has approached the scientific output from MDGs and SDGs together, we cannot assess whether other scientometric approaches or delineations would have delivered other results, therefore this is an aspect to be considered in future studies. Moreover, future studies on the topic might be complemented by means of qualitative research methods to uncover more specific motivations and drivers for research on SDGs in different contexts. The combination of scientometric indicators with other monitoring indicators (e.g., the SDG index) should also be considered. Such combination of methods will enable more advanced insights on the relationship between the research production of countries (as done in this study) and their success in their actual achievement of the specific SDGs, thus providing a more holistic perspective on how research can complement and support the consecution of Agenda 2030.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11106113.v1.

Author Contributions

NB-P: conceptualization, data curation, software, visualization, formal analysis, and writing- original draft preparation. AA: investigation, and writing—review and editing. SL and UA: writing—review and editing. RC: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources, software, validation, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors: contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Department of Science and Innovation and the National Research Foundation of South Africa.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2021.620743/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Sustainable development was defined as a “kind of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations, 1987).

2. ^Information on the MDGs available at the following link: https://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/about/en/ (accessed December 30, 2019).

3. ^SDG Index available at: http://sdgindex.org/ (accessed December 30, 2019).

4. ^There was no public consultation, as with the SDGs.

5. ^Sustainability science is a new scientific field that investigates “complex and dynamic interactions between natural and human systems and aims “to bridge the gap between science and society and limit its knowledge to actions for sustainability” (Disterheft et al., 2013).

6. ^From a theoretical point of view, we build on the notion of citations as “concept symbols” (Small, 1978) in which any publication cited by or citing M&SDGs core publications can considered to have a cognitive association with M&SDGs research.

7. ^The search strategy was composed of the following parameters: TS = “Millennium Development Goal*” OR TS = “Millennium Goal*” OR TS = “Sustainable Development Goal*”.

8. ^Web of Science divides between author keywords (included in records of articles and determined by the authors) and keywords plus or “paper authors” (index terms automatically generated from the titles of cited articles).

9. ^The approach used in this study (identification of a seed of papers, and expansion based on citation relationships) has been used in previous studies (see Reijnhoudt et al., 2014).

10. ^The period corresponds with the launch of the MDGs in 2000.

11. ^Co-citation is defined as the frequency with which two publications are cited together by other publications.

12. ^VOSviewer is a software tool for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks. These networks may include nodes of journals, researchers, or individual publications, and they can be constructed based on citation, bibliographic coupling, co-citation, or co-authorship relations. Additionally, it offers text mining functionality that can be used to construct and visualize co-occurrence networks of terms extracted from a research dataset (https://www.vosviewer.com/—accessed December 30, 2019).

13. ^Information available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed December 30, 2019).

14. ^For more clarification of these values the author is referred to the VOSViewer Manual https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.8.pdf.

15. ^Information available at: https://www.who.int/sdg/en/.

References

Adomßent, M., Fischer, D., Godemann, J., Herzig, C., Otte, I., Rieckmann, M., et al. (2014). Emerging areas in research on higher education for sustainable development e management education, sustainable consumption and perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 62, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.045

Alejandro-Cruz, J. S., Rio-Belver, R. M., Almanza-Arjona, Y. C., and Rodriguez-Andara, A. (2019). Towards a science map on sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 11:3521. doi: 10.3390/su11133521

Armitage, C. S., Lorenz, M., and Mikki, S. (2020). Mapping scholarly publications related to the Sustainable Development Goals: do independent bibliometric approaches get the same results? Quantitative Sci. Stud. 1, 1092–1108. doi: 10.1162/qss_a_00071

Asi, Y. M., and Williams, C. (2018). The role of digital health in making progress toward Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 in conflict-affected populations. Int. J. Med. Inform. 114, 114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.11.003

Bautista-Puig, N., and Mauleón, E. (2019). “Unveiling the path towards sustainability: is there a research interest on sustainable goals?” in International Conference on Scientometrics & Informetrics, Vol. 17 (Rome), 2770–2771.

Bizerril, M., Rosa, M. J., Carvalho, T., and Pedrosa, J. (2018). Sustainability in higher education: a review of contributions from Portuguese Speaking Countries. J. Clean. Prod. 171, 600–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.048

Buse, K., and Hawkes, S. (2015). Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Glob. Health 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12992-015-0098-8

Caeiro, S., Azeiteiro, U. M., Filho, W. L., and Jabbour, C., (eds.). (2013). Sustainability Assessment Tools in Higher Education Institutions: Mapping Trends and Good Practices Around the World. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Caiado, R. G. G., Filho, W. L., Quelhas, O. L. G., Nascimento, D. L. d. M., and Ávila, L. V. (2018). A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 1276–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.102

Cumming, T. L., Shackleton, R. T., Förster, J., Dini, J., Khan, A., Gumula, M., et al. (2017). Achieving the national development agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through investment in ecological infrastructure: a case study of South Africa. Ecosyst. Serv. 27, 253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.05.005

Disterheft, A., Caeiro, S., Azeiteiro, U. M., and Leal Filho, W. (2013). “Sustainability science and education for sustainable development in universities: a way for transition,” in Sustainability Assessment Tools in Higher Education Institutions: Mapping Trends and Good Practices Around the World, eds S. Caeiro, W. L. Filho, C. Jabbour, and U. M. Azeiteiro (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 3–27.

Easterly, W. (2009). How the millennium development goals are unfair to Africa. World Dev. 37, 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.02.009

Elsevier Research Intelligence (2015). Sustainability Science in a Global Landscape. Available online at: https://www.elsevier.com/research-intelligence/resource-library/sustainability-2015

Fisher, A., and Fukuda-Parr, S. (2019). Introduction—data, knowledge, politics and localizing the SDGs. J. Hum. Dev. Capabil. 20, 375–385. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2019.1669144

Forestier, O., and Kim, R. E. (2020). Cherry-picking the Sustainable Development Goals: goal prioritization by national governments and implications for global governance. Sustain. Dev. 28, 1269–1278. doi: 10.1002/sd.2082

Frame, J. D. (1977). Mainstream research in Latin America and the Caribbean. Interciencia 2, 143–148.

Fukuda-Parr, S. (2016). From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: shifts in purpose, concept, and politics of global goal setting for development. Gender Dev. 24, 43–52. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2016.1145895

Fukuda-Parr, S. (2019). Keeping out extreme inequality from the SDG agenda – the politics of indicators. Global Policy 10, 61–69. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12602

Fukuda-Parr, S., and McNeill, D. (2019). Knowledge and politics in setting and measuring the SDGs: introduction to special issue. Global Policy 10, 5–15. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12604

Fuso Nerini, F., Sovacool, B., Hughes, N., Cozzi, L., Cosgrave, E., Howells, M., et al. (2019). Connecting climate action with other Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Sustainability 2, 674–680. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0334-y

Griggs, D. J., Nilsson, M., Stevance, A., and McCollum, D. (2017). A Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation. Paris: International Council for Science.

Hák, T., Janousková, S., and Moldan, B. (2016). Sustainable Development Goals: a need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic 60, 565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.08.003

Hallinger, P., and Chatpinyakoop, C. (2019). A bibliometric review of research on higher education for sustainable development 1998-2018. Sustainability 11, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/su11082401

Hassan, S. U., Haddawy, P., and Zhu, J. (2014). A bibliometric study of the world's research activity in sustainable development and its sub-areas using scientific literature. Scientometrics 99, 549–579. doi: 10.1007/s11192-013-1193-3

Haustein, S., Bowman, T. D., and Costas, R. (2016). “Interpreting “altmetrics”: viewing acts on social media through the lens of citation and social theories,” in Theories of Informetrics and Scholarly Communication, ed C. R. Sugimoto (De Gruyter Saur), 372–406. doi: 10.1515/9783110308464-022

Hesselbarth, C., and Schaltegger, S. (2014). Educating change agents for sustainability – learnings from the first sustainability management master of business administration. J. Clean. Prod 62, 24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.03.042

International Council for Science (2015). Review of the Sustainable Development Goals: The Science Perspective. Paris: International Council for Science (ICSU).

International Human Rights Instruments. (2008). Report on Indicators for Promoting and Monitoring the Implementation of Human Rights. Geneva: United Nations.

Kajikawa, Y., Ohno, J., Takeda, Y., Matsushima, K., and Komiyama, H. (2007). Creating an academic landscape of sustainability science: an analysis of the citation network. Sustain. Sci. 2:221. doi: 10.1007/s11625-007-0027-8

Kajikawa, Y., Tacoa, F., and Yamaguchi, K. (2014). Sustainability science: the changing landscape of sustainability research. Sustain. Sci. 9, 431–438. doi: 10.1007/s11625-014-0244-x

Kleinberg, J. (2003). Bursty and Hierarchical Structure in Streams. Data Mining Knowl. Disc. 7, 373–397. doi: 10.1023/A:1024940629314

Körfgen, A., Förster, K., Glatz, I., Maier, S., Becsi, B., Meyer, A., et al. (2018). It's a hit! Mapping Austrian research contributions to the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 10, 1–13. doi: 10.3390/su10093295

Kroll, C., Warchold, A., and Pradhan, P. (2019). Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies? Palgrave Commun. 5, 1–11. doi: 10.1057/s41599-019-0335-5

Le Blanc, D. (2015). Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustain. Dev. 23, 176–187. doi: 10.1002/sd.1582

Leal Filho, W., Pallant, E., Enete, A., Richter, B., and Brandli, L. L. (2018). Planning and implementing sustainability in higher education institutions: an overview of the difficulties and potentials. In. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 25, 713–721. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2018.1461707

Leal Filho, W., Wu, Y.-C. J., Brandli, L. L., Avila, L. V., Azeiteiro, U. A., Caeiro, S., et al. (2017). Identifying and overcoming obstacles to the implementation of sustainable development at universities. J. Integrative Environ. Sci. 14, 93–108. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2017.1362007

Lozano, R., Ceulemans, K., Alonso-Almeida, M., Huisingh, D., Lozano, F. J., Waas, T., et al. (2015). A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 108, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.048

Lusseau, D., and Mancini, F. (2019). Income-based variation in Sustainable Development Goal interaction networks. Nat. Sustain. 2, 242–247. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0231-4

Min, C., Chen, Q., Yan, E., Bu, Y., and Sun, J. (2020). Citation cascade and the evolution of topic relevance. J. Assoc. Information Sci. Technol. 2020, 110–127. doi: 10.1002/asi.24370

Mongeon, P., and Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106, 213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Nakamura, M., Pendlebury, D., Schnell, J., and Szomszor, M. (2019). Navigating the structure of research on Sustainable Development Goals. Policy 11:12.

Nilsson, M., Griggs, D., and Visbeck, M. (2016). Policy: map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. News 534:320. doi: 10.1038/534320a

Nučič, M. (2012). Is sustainability science becoming more interdisciplinary over time? Acta Geogr. Sloven. 52, 215–236. doi: 10.3986/AGS52109

Olawumi, T. O., and Chan, D. W. M. (2018). A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 183, 231–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.162

Olensky, M., Schmidt, M., and Van Eck, N. J. (2016). Evaluation of the citation matching algorithms of CWTS and iFQ in comparison to the web of science. J. Assoc. Information Sci. Technol. 67, 2550–2564. doi: 10.1002/asi.23590

Pettigrew, L. M., De Maeseneer, J., Anderson, M. I. P., Essuman, A., Kidd, M. R., and Haines, A. (2015). Primary health care and the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 386, 2119–2121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00949-6

Pradhan, P., Costa, L., Rybski, D., Lucht, W., and Kropp, J. P. (2017). A systematic study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) interactions. Earth's Future 5, 1169–1179. doi: 10.1002/2017EF000632

Pukelis, L., Bautista-Puig, N., Skrynik, M., and Stanciauskas, V. (2020). OSDG–open-source approach to classify text data by UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14569.

Pulgarin, A., Eklund, P., Garrote, R., and Escalona-Fernandez, M. I. (2015). Evolution and structure of ‘sustainable development’: a bibliometric study. Brazil. J. Information Sci. Res. Trends 9:24. doi: 10.36311/1981-1640.2015.v9n1.03.p22

Rafols, I. (2020). Consensus and Dissensus in ‘Mappings’ of Science for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Blog Post on 10th August 2020. Available online at: https://leidenmadtrics.nl/articles/consensus-and-dissensus-in-mappings-of-science-for-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs

Ramírez Ríos, J. F., Alzate Ibáñez, A. M., and Montenegro Riaño, D. F. (2016). Los discursos de la sostenibilidad: análisis de tendencias conceptuales a partir de mediciones bibliométricas. Questionar: Investigación Específica 4, 82–96. doi: 10.29097/23461098.114

Reijnhoudt, L., Costas, R., Noyons, E., Börner, K., and Scharnhorst, A. (2014). ‘Seed+ expand’: a general methodology for detecting publication oeuvres of individual researchers. Scientometrics 101, 1403–1417. doi: 10.1007/s11192-014-1256-0

Sachs, J., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., and Fuller, G. (2018). SD.G Index and Dashboards Report 2018. New York, NY: Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN).

Sachs, J., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., and Fuller, G. (2019). Sustainable Development Report 2019. New York, NY: Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN).

Salvia, A. L., Leal Filho, W., Brandli, L. L., and Griebelera, J. S. (2019). Assessing research trends related to Sustainable Development Goals: local and global issues. J. Clean Prod. 208, 841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.242

Schoolman, E. D., Guest, J. S., Bush, K. F., and Bell, A. R. (2012). How interdisciplinary is sustainability research? Analyzing the structure of an emerging scientific field. Sustain. Sci. 7, 67–80. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0139-z

Seidman, G. (2017). Does SDG 3 have an adequate theory of change for improving health systems performance? J. Glob. Health 7. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010302

Siegel, K. M., and Bastos Lima, M. G. (2020). When international sustainability frameworks encounter domestic politics: the sustainable development goals and agri-food governance in South America. World Dev. 135:105053. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105053

Singh, G. G., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Swartz, W., Cheung, W., Guy, J. A., Kenny, T. A., et al. (2018). A rapid assessment of co-benefits and trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals. Marine Policy 93, 223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.05.030

Small, H. (1978). Cited documents as concept symbols. Soc. Stud. Sci 8, 327–340. doi: 10.1177/030631277800800305

Sweileh, W. M. (2020). Bibliometric analysis of scientific publications on “sustainable development goals” with emphasis on “good health and well-being” goal (2015–2019). Global. Health 16:68. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00602-2

Tatalović Antony (2010). What Has It Done For The Millennium Development Goals?' Available online at: http://www.scidev.net/global/health/feature/science-what-has-it-done-for-the-millennium-development-goals-1.html

United Nations (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development. Oslo: United Nations.

United Nations (2015a). Millennium Development Goals: 2015 Progress Chart. Available online at: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20PC%20final.pdf

United Nations (2015b). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). Available online at: https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1

Van Eck, N. J., and Waltman, L. (2017). Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 111, 1053–1070. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2300-7

Veiga Ávila, L., Rossato Facco, A. L., Bento, M. H., dos, S., Arigony, M. M., Obregon, S. L., et al. (2018). Sustainability and education for sustainability: an analysis of publications from the last decade. Environ. Qual. Manage. 27, 107–118. doi: 10.1002/tqem.21537

Vinuesa, R., Azizpour, H., Leite, I., Balaam, M., Dignum, V., Domisch, S., et al. (2020). The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14108-y

Waas, T., Verbruggen, A., and Wright, T. (2010). University research for sustainable development: Definition and characteristics explored. J. Clean. Prod. 18, 629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.09.017

Waltman, L., Calero-Medina, C., Kosten, J., Noyons, E. C., Tijssen, R. J., van Eck, N. J., et al. (2012). The Leiden ranking 2011/2012: data collection, indicators, and interpretation. J. Am. Soc. Information Sci. Technol. 63, 2419–2432. doi: 10.1002/asi.22708

Wuelser, G., and Pohl, C. (2016). How researchers frame scientific contributions to sustainable development: a typology based on grounded theory. Sustain. Sci 11, 789–800. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0363-7

Keywords: sustainable development goals, millennium development goals, higher education institutions, sustainability science, bibliometrics, scientometrics

Citation: Bautista-Puig N, Aleixo AM, Leal S, Azeiteiro U and Costas R (2021) Unveiling the Research Landscape of Sustainable Development Goals and Their Inclusion in Higher Education Institutions and Research Centers: Major Trends in 2000–2017. Front. Sustain. 2:620743. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.620743

Received: 23 October 2020; Accepted: 01 March 2021;

Published: 25 March 2021.

Edited by:

Kim Ceulemans, TBS Business School, FranceReviewed by:

Mairon G. Bastos Lima, Chalmers University of Technology, SwedenFlorian Findler, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Austria