The Impact of the Environmental Quality Label on the Companies Operating Within the Porto Conte Marine Protected Area in Sardinia (Italy)

- Department of Economics and Business, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy

The Porto Conte Natural Park, an institution managing and developing the area surrounding the territory of Alghero in Sardinia, decided to join the Park and Protected Area Network Environmental Quality Label (“Marchio di Qualità della Rete dei Parchi e delle Aree Protette”). The label may be awarded to products and accommodation facilities taking special care of the protection of the environmental and local development. In order to evaluate the benefits of this initiative on the companies operating within the park, a survey was administered among the companies awarded with the label and the local community. The companies recognized the benefits thereof, mostly in terms of reputation, as a result of the adoption of responsible environmental behaviors by the members of the business organization. In addition, greater attention to environmental protection resulted in a decrease of waste production and a rigorous compliance with the applicable rules and regulations. Most of the companies interviewed were generally satisfied with the park's project but complained about the poor advertising initiatives by the Park's Managing Body. As a matter of fact, about the 50% of the residents interviewed were not aware of the label award and the product certification. Considering that the residents of the park area are sensitive to environmental issues, and they believe that the park is a major asset for the area, better communication, and a greater involvement of all stakeholders in the initiative undertaken by the Park's Managing Body may help companies expand their business also locally.

Introduction

In Italy, the awareness of the need to protect the territory has been consolidating over the years, focusing on those land, river, lake, or marine areas which require a governmental intervention to secure their conservation. In Italy, the protected area heritage is quite wide and covers 10.5% of the national territory (MD of April 27, 2010). These areas include 24 national parks and 134 regional parks, with an area of ~29,000 km2 in total. In particular, parks are places where human activities play an important role (agriculture, livestock farming, crafts, tourism, etc.). For this reason, they are an expression and a vehicle for a diverse range of values. As a matter of fact, in addition to strictly environmentally friendly values, they can communicate other values and culture (traditions, foods, agricultural techniques, etc.) strictly connected to a territory by introducing them in the national and international dimensions. Originally perceived as a restriction by the local population (Heatherington, 2005; Jones and Burgess, 2005; Renzetti and Petrella, 2007; Dimitrakopoulos et al., 2010) and having a merely environmental protection function, during the last few years, parks have become labs to test novel land management policies, oriented by the principles of sustainable development. Nowadays, parks are considered places where the connection between the economy, social development and the environment is visible (Getzner, 2003, 2010; Naughton-Treves et al., 2005). Generating economic development to sustain local population is a widely shared goal among protected areas (Borrini-Feyerabend et al., 2013; Dudley et al., 2013; Mayer and Job, 2014). This also embodies the spirit of the Italian Framework Law no. 394/1991, known as the Italian Framework Law on Protected Areas, which is the legal instrument that lays down the core principles for the establishment and management of protected areas in Italy. Art. 14 of Title II of the Law includes the economic and cultural promotion objectives, so that the protected area may become a driving force for economic development, for the benefit of local communities. An effective tool to promote the Park area and also local businesses, is the award of the Park label to those companies which operate within the Park's territory. The logo is intended to promote local social and economic development and increase the awareness and participation of all stakeholders in the proper management of the environment (Kraus et al., 2014; Knaus et al., 2017; Escribano et al., 2020).

Several Italian parks have granted the use of their name and logo to services and products which meet specific quality requirements and the principles of environmental sustainability. This strategy has been carried out also by the Porto Conte Park in Sardinia that contributed to the creation of the Park and Protected Area Network Environmental Quality Label. Through the mark, the origin and top quality of the products and services offered with an environmentally friendly approach are certified. Since the label was created as a tool to foster the growth of the local territory and its community, a survey was carried out among a sample group of labeled companies, in order to assess whether they benefited from this initiative. The survey on the knowledge and perception of the significance of the Park label was extended to a sample of residents. Being aware of the role of the park within the territory and the initiatives implemented to protect the natural heritage and the economic development for the benefit of the whole community, they could serve as active stakeholders in supporting the initiatives promoted by the Park. In addition, residents could act as promoters for the label connected to the values of the territory (Wassler et al., 2021).

Context Study

The Regional Natural Park of Porto Conte is a nature reserve located in northwest Sardinia (https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sardegna), the second largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Being the Italian region with the longest of coastline, with its 1,897 kilometers, it includes some of the most popular beaches in Italy. Its natural heritage is rich in interesting sites and natural monuments, some of which are protected by the establishment of protected areas. In Sardinia, there are three national parks, two regional parks and several nature reserves and minor oases that cover an area of 2,734,978 ha, that is, ~11% of the entire region.

The Regional Natural Park of Porto Conte is named after Porto Conte, a site of significant geographic and naturalistic importance that covers most of it. The area of reference includes the Park itself and the agricultural lands located north of the town of Alghero. Established by Regional Law No. 4 of 26 February https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/19991999, it has an area of 5,350 ha within the administrative boundaries of the Municipality of Alghero (https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alghero), the latter being responsible for its management through the “Azienda Speciale Parco di Porto Conte” managing body, the Porto Conte Park Special Agency. On the coast of Alghero, also known as “Riviera del Corallo,” ~90 km long, there are some of the most famous Italian beaches, which facilitate tourist development. As a matter of fact, the territory of Alghero is the tourist area with the highest concentration of accommodation facilities in Sardinia and, in 2020, it ranked first among the best Sardinian tourist destinations, with 3,18,454 arrivals, i.e., 8.9% of the total number of arrivals to the island (Sired Regione Sardegna - Report, 2021). Sixty two percent of arrivals are international tourists who are mainly attracted by its pristine nature and leisure activities, such as hiking, climbing, and cycling, not to mention local food and wine (CNA Sardegna, 2017). Therefore, with its wide range of attractions, such as the pristine landscapes, a unique variety of plant and animal species, and traditional food products, the Park of Porto Conte plays a major tourist and recreational role for the territory of Alghero.

Park and Protected Area Network Environmental Quality Label

Considering that one of the purposes of the protected areas is the local social and economic development (Framework Law No. 394/1991), in order to fully implement this action, in 2012 the Managing Body of the Porto Conte Park launched the Park and Protected Area Network Environmental Quality Label (Figure 1). The label is designed to guarantee consumers that products and services meet environmental and quality standards, and, at the same time, it grants market visibility to the businesses involved in land protection and the promotion of the local natural heritage.

Figure 1. Park and protected area network environmental quality label. Source: www.algheroparks.it.

The label was created in the framework of the EU-funded RetraPark project, approved in 2009 under the Italy-France “Maritime” Operational Program. The project involved the Regional Natural Park of Porto Conte, the National Park of Asinara, the National Park of La Maddalena, the Office de l'Environnement de la Corse, and the Parc Naturel Régional de Corse. The aim of the project was the creation of a cross-border network of parks in Sardinia and Corsica to promote an integrated management of parks and protected areas and to develop joint awareness raising activities. The Managing Body of the Porto Conte Park played a crucial role in the quality assurance process of the Parks Network, the communication plan, the web portal, the creation of the logo, and the Network Label. Then, in 2015, the so-called “Park Network,” including the three parks located in North Sardinia and the Molentargius Regional Park in the south of the island, was established and the Park and Protected Area Network Environmental Quality Label (“Marchio di Qualità Ambientale della Rete dei Parchi e delle Aree Protette”) was launched.

It is a certification label that is only awarded to companies possessing quality standards certified in accordance with strict environmental sustainability production protocols. Companies interested in being labeled are required to submit their application to the local Park Managing Body and be evaluated by the Monitoring Body identified by the Label Committee, that launches the evaluation procedures, assesses compliance, and issues the label license. The use of the label is governed by a regulation that specifies the requirements for a number of categories of products and services, such as food, handicraft, cosmetic, household, pharmaceuticals products, not to mention tourist and accommodation services. The requirements provided for each category are described in each Quality Charter (http://algheropark.it). Workers are required to comply with some general principles regarding, first of all, the compliance with applicable rules and regulations, including environmental laws regarding air emissions, wastewater treatment, proper waste management, water supply, etc. Companies will also have to comply with the mandatory standards relating to food and workplace safety. In addition to the sectors of reference, mandatory requirements have been identified. Companies are required to meet them when submitting the label award request/renewal. To help the label beneficiary reduce its environmental impact, optional additional requirements have also been defined, i.e., additional objectives a company may pursue and apply through an improvement program. To be awarded the label, the company is required to comply with the set of main criteria and a number of optional ones, up to a score equal to 12. On a three-year basis, the company will have to set new optional criteria. To date, 42 companies have been awarded the Porto Conte Park Network label, including 21 farms, 12 accommodation facilities, and 9 tourist service companies.

Methods

The managers of all the certified companies operating within the Porto Conte Park were interviewed by means of a survey sent by email between January and July 2020. The survey was responded by 29 companies, that is, 69% of the total number of certified companies. Forty one percent are engaged in the agri-food sector, 31% are accommodation facilities (hotels, farmhouses, and restaurants), and 28% recreational service companies. The first part of the survey submitted to the managers concerned the respondents' profile and their environmental awareness. Then, the reasons that pushed them to be certified and the benefits gained from the award of the label were investigated. A survey was prepared to study a random sample of adults that had their customary residence in Alghero, aged between 21 and 71. The survey was created using Google Forms. A team of volunteers living in Alghero shared the survey among their contacts and administered the questionnaire via email, Facebook, and Instagram (Saha et al., 2020). The survey was administered to approximately 3,500 residents. 24.7% of them, that is, 864 residents, took part in the survey. Five percent of the surveys were discarded, being incomplete; therefore, the sample consisted of 820 residents that accounted for 2% of the entire population of the town. The response rate was of 23.4% and it could be considered acceptable for a survey administered via e-mail. In other studies, the response rate was 19% (Chen, 2000), 14.6% (Dyer et al., 2007) and 12.4% (Yu and Chancellor, 2018).

The survey addressed to residents collected, firstly, information on age, gender, and education, and evaluated environmental awareness. The second part of the survey investigated their acquaintance with Porto Conte and the role they believed it played on the territory. The last section of the survey concerned the residents' acquaintance with, and perception of, the role played by the Park and Protected Area Network Quality Label. Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet (ver. 2016), and descriptive statistics were calculated.

Results and Discussion

Results of the Survey Administered to Park-Labeled Companies

In the first section of the survey, information of the manager's profile was gathered. About 60% of respondents were aged between 31 and 50 years. Most of them had a high level of education, 41% of them having a University degree and 45% of them having a high-school diploma.

To assess the environmental awareness of the respondents, they were asked to evaluate the importance of the natural environment for their business according to a Linker type scale (from 1 = not important to 5 = extremely important): 83% stated that an unpolluted environment was extremely important for the success of their companies. The same percentage claimed to have a thorough understanding of the environmental impacts associated with their activities and to keep an environmentally responsible behavior during their work activities. Awareness of the economic benefits provided by the protected area motivated park users to safeguard natural resources (Heinen et al., 2017).

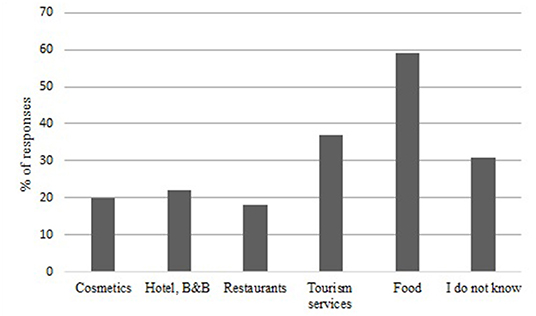

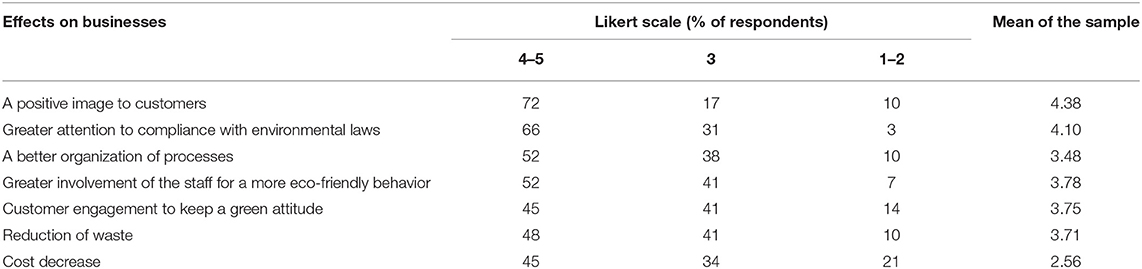

Further questions were posed regarding their opinion on the benefits deriving from the award of the Park label. The first question investigated the reasons why they decided to apply for the label (Figure 2). Results show that the majority of respondents (35%) applied because their customers appreciate their commitment to safeguarding the environment. Twenty eight percent of the companies applied because they already met the criteria laid down by the quality charters. This shows that operating in a natural area of great environmental value steered the choice of companies to raise their own awareness regarding the importance of environmental protection within the area where they operate, that also prompted policies intended to reduce their environmental impacts. Companies were also asked to evaluate, on a 5-point scale (from 1 = always to 5 = never) how often the environmental quality label might influence their customers' choices. In this regard, respondents believed that the label was often (55%) or sometimes (42%) appreciated by customers, and that the European ones (56% of responses) were more attentive to labeling, compared to local and national customers (24 and 20% of the answers, respectively). This seems to contradict the results of Sörensson and von Friedrichs (2013), who showed that Italians, compared to foreigners, were more attentive to the sustainability of the locations they visit. This is probably due to their limited trust in eco-labeling, as well as the Italians' poor acquaintance with it (Belcastro, 2020). The last part of the survey investigated the potential benefits gained from the award of the label. Respondents were asked to express their opinion on a 5-point scale regarding whether the award of the label and environmental protection could have a positive impact on companies (Table 1). The Environmental Quality Label was acknowledged to have fostered a positive image to the companies, thus achieving one of the main objectives that, in general, companies intend to achieve with environmental certification (Matuszak-Flejszman, 2009; Talapatra et al., 2019). It also helped companies comply with environmental regulations in a timely and strict manner. This is a great success connected to the label, because in Italy environmental regulations mostly consist of highly fragmented and complex sets of rules. It is therefore very hard to be acquainted with all the provisions governing the protection of the environment, which, moreover, are constantly evolving. Concern about complying with the regulations is one of the main reasons why companies seek environmental certification, as reported by organizations based in other countries (Jiang and Bansal, 2003; Matuszak-Flejszman, 2009; Jewalikar and Shelke, 2017; Talapatra et al., 2019). The Porto Conte Park Environmental Quality label, as well as the Environmental Management System ISO 14001, was effective to help companies comply with legal requirements.

Figure 2. Reasons why companies within the Porto Conte Natural Park decided to be certified with the “Marchio di Qualità Ambientale della Rete dei Parchi e delle Aree Protette.

Table 1. Perception of the surveyed managers regarding the benefits gained from the award of the Park and Protected Area Network Quality Label.

The companies had quite good results also in terms of environmental awareness raising among their staff and customers. The training/information activities for staff and users, are expected to help the in-house dissemination of sustainability values among the employees who were, therefore, motivated to keep proper environmental behaviors during work activities and were willing to raise awareness among customers, motivating them to have eco-friendly attitudes. Research showed that when people are provided with information about environmental problems, and what they can do to decreases their impact on the environment, they are willing to take pro-active environmental behaviors (Ramayah et al., 2012; Rahman and Reynolds, 2016; Lu and Wang, 2018; Abdullah et al., 2020).

This change of mindset within the company is not easy to achieve, since almost half of the certified companies did not report a very positive effect as a result of staff involvement and their ability to communicate the company's values to customers, although the latter is one of the requirements provided for by the Quality Charter. Certainly, training/information activities do not prove sufficient to affect positively employees' pro-environmental behaviors (Perron et al., 2006). Additional determinants, such as employees' motivation (Osbaldiston and Sheldon, 2003), environmental concern (Chan et al., 2014), self-efficacy (Scherbaum et al., 2008), and generational differences (Kim et al., 2016) may come into play.

On average, the companies surveyed reported a waste reduction during their work activities but did not experience any cost reduction.

In the last section of the survey, respondents were asked to evaluate on a 5-point scale (from 5 = fully satisfied to 1 = absolutely not satisfied), the level of satisfaction regarding the park label award: most of the operators (70%) were fully or very satisfied to have joined the Park's initiative and would suggest others to join.

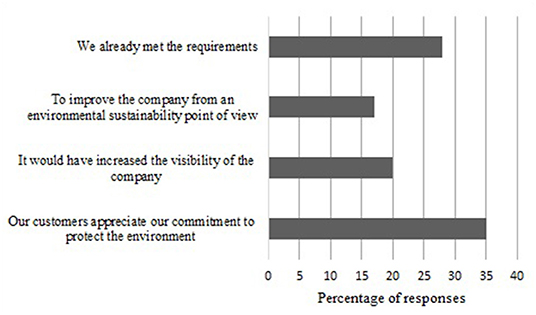

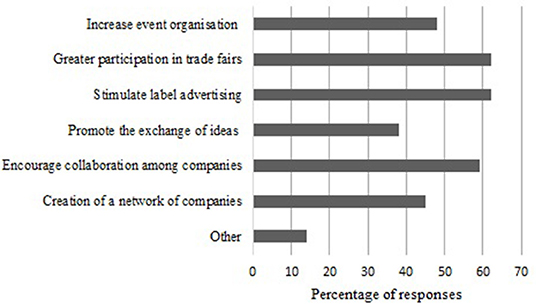

Respondents still believe that some actions to promote certified companies, are not sufficient (Figure 3). In particular, they believe that first of all, marketing should be boosted, since the main reason why they applied for the label was to increase their visibility and improve the company's image. They also feel that the Park Managing Body should further promote cooperation among labeled companies. This would prompt the mutual development of the Park's companies which would be encouraged to use and promote the Park's products and services among their customers.

Figure 3. Actions to promote the certified companies according to the managers (percentage of answers given by respondents who could give a maximum of two answers).

Survey on the Residents of the Porto Conte Park Area

In the first section of the survey, information of the residents' profile was gathered. The sample mainly consists of women (64%), mostly included in the 21–30 (38%) and 41–50 (19%) age groups and in possession of a high school (47.7%) or University degree (43.8%).

To assess the residents' interest in the park, they were asked whether they had ever visited the protected area. Only 12% of the respondents had never been there and most of them were adults aged over 40 years. Contrary to other communities which perceive a protected area as a very strict zone where some activities are prohibited (Oracion et al., 2005; Ciocanea et al., 2016), the residents of Alghero held a positive attitude toward the natural park. For the Park Managing Body this is an important starting point to gain the support to its strategies from the local community. Awareness of environmental threats or benefits fosters public support to new policy options (Jefferson et al., 2015; Heinen et al., 2017; Johnston et al., 2020).

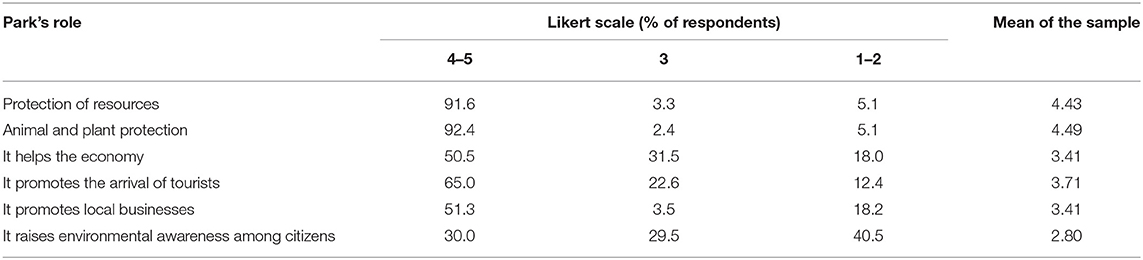

The answers to the question “Who have you visited the Park with?” were different depending on the age bracket. Most of the youngest respondents (41%) had visited the protected area during a school trip. The Park therefore is proving to carry out the important environmental education function, organizing initiatives involving schools through the “Speciale Scuole” program, that includes visits to museums, interactive exhibits, classrooms, and guided tours. Many young people (30%) have visited the protected area with friends, while families do not seem to have played an important role in introducing them to this part of the territory they live. The older interviewed adults, that is, over the age of 41, have visited the park with their families and friends, while, at all ages, a limited the percentage have joined organized groups for guided tours. In order to investigate the role played by the Park according to residents, respondents were asked to evaluate on 5-point scale (from 5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree), their opinion on the effectiveness of the Park in achieving its main objectives (Table 2). As perceived by the residents in other natural parks (Ciocanea et al., 2016), also the inhabitants of Alghero consider the Park mostly as a nature conservation instrument, while it plays a less prominent role as a driving force for the economic development of the territory. The idea that ecological benefits are greater than economic benefits is common to people living in other special natural areas of interest (Gao et al., 2014; Barbieri et al., 2019). This perception appears to be attributable to the lack of awareness of the economic benefits provided by the ecological system (Gao et al., 2014). The lack of information on the park's values is negatively reflected in the behavior of citizens toward environment issues. Indeed, interviewed residents believe that the presence of the Park did not sufficiently raise environmental awareness among residents. Their concern about the local environmental degradation and the misbehavior of the survey participants remains high. This residents' perception should suggest the Park Managing Body to pursue initiatives aimed at informing and raising awareness to protect the environment among citizens, since environmental education programs are crucial to promote pro-environmental behaviors (Antimova et al., 2012; Abdullah et al., 2020).

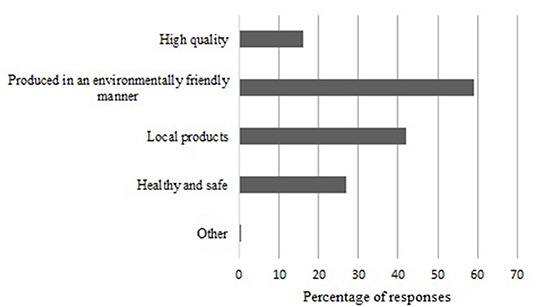

The last section of the survey investigated the residents' knowledge of the Park and Protected Area Network Label and the importance they attach to it. Sixty five percent of the respondents who were shown the label (Figure 1) could not recognize the logo, although the following question was “Do you know the Porto Conte Park and Protected Area Network Label?,” and a smaller percentage (46%) of respondents said they did not know there was such a thing. This could be due to the confusion generated by another logo by which the Porto Conte Park is promoted. Acquaintance with the label was different according to the age bracket; as a matter of fact, 56% of young people (aged 21–30) did not know it, compared to 32% of adults over 50 years of age. However, around 42% of those who did not know the label had frequented the park. This suggests that the advertising campaign carried out by the Park Managing Body was poor, as the managers of the Park-labeled companies also claimed. Those who knew the brand were asked whether they knew what kind of products/services could be awarded the label (Figure 4). Fifty nine percent of them associated the label with food and 76% of them considered the Park's products as better than conventional food. In particular, the main distinguishing feature of the Park's products is related to their low environmental impact production methods (Figure 5). This is an important strength of the park's products, since especially younger generations attribute great importance to food sustainability in their purchasing choices (Pomarici and Vecchio, 2014; Mancuso et al., 2021). Therefore, the food sector has a good reputation and is the one that is making the most out of the Park label. Indeed, it is the sector with the largest number of certified companies, but also because there are many initiatives carried out by the Park which involve them. In some cases, even the facilities helped publicize the Park's typical products and they considered the inclusion in their menu of those food products as an important element. Indeed, the sector is considered important for the development of accommodation facilities operating within the Park which have a strong interest in wine and food tourism. On the contrary, the facilities generally do not use the Park's logo as a distinctive sign in all the communication channels, their websites often do no display the logo, and no information regarding the certification is available.

Figure 5. Distinctive features of the Porto Conte Park's products according to residents (percentage of answers given by respondents who could give a maximum of two answers).

Limitations and Further Research

The study has some limitations that can be addressed in further research. The analysis was addressed only to the certified companies; therefore, it is difficult to determine unambiguously whether using the Park label contributed directly to achieving the environmental benefits. Comparison with park businesses that have not joined the label may allow for better feedback on the positive impact of certification. Future studies may investigate companies with the same type of certification, located in other parks in Italy, in order to have a larger sample on which assessments on the impact of certification in various economic sectors may be performed.

Conclusion

The survey concerning companies and residents within the Porto Conte Park in Alghero, showed that the protected area is considered an added value for the whole community. Companies operating within Porto Conte Park in Alghero, which were awarded the Park and Protected Area Network Label, considered it a good opportunity to highlight their commitment to environmental protection. Among the benefits attached to the label, therefore, there is a greater market visibility and the creation of a positive image for customers, especially for European tourists visiting the territory of Alghero to enjoy its natural beauty and pristine nature. From an organizational standpoint, companies recognize that the label helped them comply strictly with environmental regulations, while no improvement was reported, cost-wise. The survey administered to local residents showed that they appreciate the value of nature and have a positive attitude toward the natural park. A large percentage of the respondents visited the Porto Conte Park, but about half of them were not aware of the initiatives launched to promote the Park's products and services. The Park label is known by less than half of the residents interviewed, not being sufficiently informed about it, and it fails to encourage the local companies in their sustainable procuring practices and become brand ambassadors, thus contributing to improve the reputation of the label.

Given the results, this study can contribute to providing information on the benefits brought by the implementation of quality labels for natural parks. In a territory with a good environmental culture, companies and citizens are favorably inclined toward initiatives for the protection of natural resources, but they must be made more aware of the economic benefits that these can bring to the entire community.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdullah, S. I. N. W., Samdin, Z., Ho, J. A., and Ng, S. I. (2020). Sustainability of marine parks: is knowledge-attitude-behaviour still relevant? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 22, 7357–7384. doi: 10.1007/s10668-019-00524-z

Antimova, R., Nawijn, J., and Peeters, P. (2012). The awareness/attitude-gap in sustainable tourism: a theoretical perspective. Tour. Rev. 67, 7–16. doi: 10.1108/16605371211259795

Barbieri, C., Sotomayor, S., and Aguilar, F. X. (2019). Perceived benefits of agricultural lands offering agritourism. Tour. Plan. Dev. 16, 43–60. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2017.1398780

Belcastro, M. (2020). La sostenibilità ambientale nel turismo: un'analisi empirica sul valore aggiunto del marchio Ecolabel UE percepito dai consumatori di servizi ricettivi (Ph.D. thesis). University of La Sapienza-Rome, Rome, Italy.

Borrini-Feyerabend, G., Dudley, N., Jaeger, T., Lassen, B., Pathak Broome, N., Phillips, A., et al. (2013). Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 20. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Chan, E. S. W., Hon, A. H. Y., Chan, W., and Okumus, F. (2014). What drives employees' intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern, and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 40, 20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.03.001

Chen, J. S. (2000). An investigation of urban residents' loyalty to tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 24, 5–19. doi: 10.1177/109634800002400101

Ciocanea, C. M., Sorescu, C., Ianosi, M., and Bagrinovschi, V. (2016). Assessing public perception on protected areas in Iron Gates Natural Park. Procedia Environ. Sci. 32, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.proenv.2016.03.013

CNA Sardegna (2017). Economia e turismo: modelli a confronto la Sardegna ed i suoi competitori. Available online at: http://Cnasarda.it (accessed April 14, 2021).

Dimitrakopoulos, P. G., Jones, N., Iosifides, T., Florokapi, I., Lasda, O., Paliouras, F., et al. (2010). Local attitudes on protected areas: evidence from three natura 2000 wetland sites in Greece. J. Environ. Manage. 91, 1847–1854. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.04.010

Dudley, N., Stolton, S., and Shadie, P. (2013). Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 21. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Dyer, P., Gursoy, D., Sharma, B., and Carter, J. (2007). Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tour. Manag. 28, 409–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.002

Escribano, M., Gaspar, P., Mesias, F. J. (2020). Creating market opportunities in rural areas through the development of a brand that conveys sustainable and environmental values. J. Rural Stud. 75, 206–215.

Gao, J., Barbieri, C., and Valdivia, C. (2014). A socio-demographic examination of the perceived benefits of agroforestry. Agroforest Syst. 88, 301–309. doi: 10.1007/s10457-014-9683-8

Getzner, M. (2003). The economic impact of national parks: the perception of key actors in Austrian National Parks. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 6, 183–202. doi: 10.1504/IJSD.2003.004214

Getzner, M. (2010). Impacts of protected areas on regional sustainable development: the case of the Hohe Tauern national park (Austria). Int. J. Sustain. Econ. 2, 419–441. doi: 10.1504/IJSE.2010.035488

Heatherington, T. (2005). “As if someone close to me had died”: intimate landscapes, political subjectivities, and the problem of a park in Sardinia,” in Mixed Emotions: Anthropological Studies of Feeling, eds K. Milton and M. Svašek (Oxford: Routledge), 145–62. doi: 10.4324/9781003135470-9

Heinen, J. T., Roque, A., and Collado-Vides, L. (2017). Managerial implications of perceptions, knowledge, attitudes, and awareness of residents regarding Puerto Morelos Reef National Park, Mexico. J Coast. Res. 33, 295–304. doi: 10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-15-00191.1

Jefferson, R., Capstick, S., McKinley, E., Fletcher, S., Griffin, H., and Milanese, M. (2015). Understanding audiences: making public perceptions research matter to marine. Ocean Coast Manag. 115, 61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.06.014

Jewalikar, A. D., and Shelke, A. (2017). Lean integrated management systems in MSME reasons, advantages, and barriers on implementation. Mater. Today 4, 1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2017.01.117

Jiang, R. J., and Bansal, P. (2003). Seeing the need for ISO 14001. J. Manag. Stud. 40, 1047–1067. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00370

Johnston, J. R., Needham, M. D., Cramer, L. A., and Swearingen, T. C. (2020). Public values and attitudes toward marine reserves and marine wilderness. Coast. Manag. 48, 142–163. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2020.1732800

Jones, P., and Burgess, J. (2005). Building partnership capacity for the collaborative management of marine protected areas in the UK: a preliminary analysis RID C-3 322-2008. J. Environ. Manage. 77, 227–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.04.004

Kim, S. H., Kim, M., Han, H. S., and Holland, S. (2016). The determinants of hospitality employees' pro-environmental behaviors: the moderating role of generational differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 52, 56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.09.013

Knaus, F., Bonnelame, L. K., and Siegrist, D. (2017). The economic impact of labeled regional products: the experience of the UNESCO biosphere reserve Entlebuch. Mt. Res. Dev. 37, 121–130. doi: 10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-16-00067.1

Kraus, F., Merlin, C., and Job, H. (2014). Biosphere reserves and their contribution to sustainable development. A value-chain analysis in the Rhon Biosphere Reserve, Germany. Z. Wirtschaftsgeog. 58, 164–180. doi: 10.1515/zfw.2014.0011

Lu, J., and Wang, C. (2018). Investigating the impacts of air travelers' environmental knowledge on attitudes toward carbon offsetting and willingness to mitigate the environmental impacts of aviation. Transport. Res. D. Transport. Environ. 59, 96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2017.12.024

Mancuso, I., Natalicchio, A., Panniello, U., and Roma, P. (2021). Understanding the purchasing behavior of consumers in response to sustainable marketing practices: an empirical analysis in the food. Sustainability. 13, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/su13116169

Matuszak-Flejszman, A. (2009). Benefits of environmental management system in Polish companies compliant with ISO 14001. Polish J. of Environ. Stud. 18, 411–419.

Mayer, M., and Job, H. (2014). The economics of protected areas in a European perspective. Z. Wirtschaftsgeog. 58, 73–97. doi: 10.1515/zfw.2014.0006

MD of April 27 (2010). Approvazione dello schema aggiornato relativo al VI Elenco ufficiale delle aree protette, ai sensi del combinato disposto dell'articolo 3, comma 4, lettera c), della Legge 6 dicembre 1994, n. 394 e dell'articolo 7, comma 1, del D.Lgs. 28 agosto 1997, n.281. Published in Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 125 del 31.05.2010.

Naughton-Treves, L., Holland, M. B., and Brandon, K. (2005). The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 219–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.164507

Oracion, E. G., Miller, M. L., and Christie, P. (2005). Marine protected areas for whom? Fisheries, tourism, and solidarity in a Philippine community. Ocean Coast Manag. 48,393–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.04.013

Osbaldiston, R., and Sheldon, K. M. (2003). Promoting internalized motivation for environmentally responsible behavior: a prospective study of environmental goals. J. Environ. Psycho. 23, 349–357. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00035-5

Perron, G. M., Côté, R. P., and Duffy, J. F. (2006). Improving environmental awareness training in business. J. Clean. Prod. 14, 551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.07.006

Pomarici, E., and Vecchio, R. (2014). Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: an exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 66, 537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.058

Rahman, I., and Reynolds, D. (2016). Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 52, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.09.007

Ramayah, T., Lee, J. W. C., and Lim, S. (2012). Sustaining the environment through recycling: an empirical study. J. Environ. Manage. 102, 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.02.025

Renzetti, E., and Petrella, A. (2007). La percezione del Parco Naturale Adamello-Brenta nell'opinione dei residenti. Rapporto finale. Available online: http://www.pnab.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/LapercezionedelPnabnell'opinionedeiresidenti_UniversitàdiTrento2007 (accessed May 27, 2021).

Saha, S. K., Zhuang, G., and Li, S. (2020). Will consumers pay more for efficient delivery? An empirical study of what affects e-customers' satisfaction and willingness to pay on online shopping in Bangladesh. Sustainability 12, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/su12031121

Scherbaum, C. A., Popovich, P. M., and Finlinson, S. (2008). Exploring individual-level factors related to employee energy-conservation behaviors at work. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 38, 818–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00328.x

Sired Regione Sardegna - Report (2021). Movimento turistico Sardegna 2020 su 2019. Available online at: http://osservatorio.sardegnaturismo.it

Sörensson, A., and von Friedrichs, Y. (2013). An importance–performance analysis of sustainable tourism: a comparison between international and national tourists. J. Destination Mark. Manage. 2, 14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.11.002

Talapatra, S., Santos, G., Uddin, K., and Carvalho, F. (2019). Main benefits of integrated management systems through literature review. Int. J. Qual. Res. 13, 1037–1054. doi: 10.24874/IJQR13.04-19

Wassler, P., Wang, L., and Hung, K. (2021). Residents' power and trust: a road to brand ambassadorship? J. Dest. Mark. Manage. 19, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100550

Keywords: natural park, quality label, certified companies, benefits of certification, resident perception

Citation: Zito C and Manca G (2021) The Impact of the Environmental Quality Label on the Companies Operating Within the Porto Conte Marine Protected Area in Sardinia (Italy). Front. Sustain. 2:747682. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.747682

Received: 26 July 2021; Accepted: 27 September 2021;

Published: 04 November 2021.

Edited by:

Federica Murmura, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, ItalyReviewed by:

Caterina Tricase, University of Foggia, ItalyKalev Sepp, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Estonia

Silvio Cardinali, Marche Polytechnic University, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Zito and Manca. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gavina Manca, gmanca@uniss.it

Carla Zito

Carla Zito Gavina Manca

Gavina Manca