- 1Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Department of Community Development, Faculty of Social Science, University of Timor-Leste (UNTL), Dili, Timor-Leste

- 3School of Social Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 4Institute for Human Security, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

This article reports on an empirical study conducted in Timor-Leste that explored the drivers, benefits, and challenges of partnerships and collaborations between water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) organisations as integral parts of the WASH system. The research design was primarily qualitative and included a data-collection workshop with 30 representatives from 16 civil society organisations (CSOs) in Dili, longitudinal research involving two rounds of semi-structured interviews over 2.5 years with five organisations, and semi-structured interviews with an additional 18 CSOs. We applied a framework of post-development theory, including critical localism and working contingently. Key drivers to form partnerships were found to be the identification of community WASH service gaps and the alignment of advocacy agendas. Key benefits reported were increased inclusion and empowerment outcomes and strengthened organisational knowledge and capacity. Challenges emerge when organisations' key staff change, strategies misalign, and financial and administrative capabilities differ. The study contributes practical insights into how civil society organisations (CSOs) partner to strengthen mutual WASH and GESI strategies and programmes and their outcomes. We recommend strengthening the partnerships between WASH and GESI organisations in ways that are cognisant of power dynamics, local priorities, and capacity needs and promote longevity and continuity through ownership of decisions at the local level. Our findings suggest that meaningful, reciprocal, and respectful engagement with WASH and GESI organisations enables WASH programmes to be in a better position to address the harmful norms that drive inequitable behaviours, thus strengthening localism, and the WASH governance system overall.

1. Introduction

The turbulent history of Timor-Leste, encompassing colonisation, military occupation, and domestic political challenges, has hampered development in the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector. The Republica Democratica de Timor Leste (RDTL), or the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, achieved independence on 20 May 2002 after 24 years of military occupation by neighbouring Indonesia (1975–1999) and 2 years under the administration of the United Nations (UN). The Indonesian occupation was fiercely resisted by an independence movement, resulting in a high death toll. Today Timor-Leste is considered a successful, resilient democracy but one that faces post-conflict and economic challenges (Croissant and Lorenz, 2018). One of these challenges is the provision of clean water and sanitation, with 43% of its people not having access to basic sanitation, 15% not having access to basic water supplies, and 72% not having access to basic hygiene (World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2021). The lack of access to water, sanitation and hygiene affects the poorest and most marginalised people, primarily in rural contexts (Troeger et al., 2015; Neely and Walters, 2016; Clarke et al., 2021).

Safely managed WASH services are commonly sought after and requested by those responsible for reproductive and domestic labour, predominantly women and girls (in all their diversity). WASH is an area of life that women and girls are often keen to participate in because of the pressing WASH needs they experience and their knowledge of community needs. Better access to WASH facilities would do much to improve the lives and status of the poorest women in Timorese society (Grant et al., 2019a). In 2021, Timor-Leste had a female Human Development Index (HDI) score of 0.580, in contrast with 0.633 for males, placing it among the lowest gender-parity ranked countries (United Nations Development Program (UNDP), 2022, p. 288). Women also have significant knowledge about WASH needs and systems that can be drawn on to design and implement effective and sustainable WASH. For these reasons, WASH and Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) advocacy and service are natural allies with civil society organisations (CSOs) in Timor-Leste, and their partnerships and collaborations are the focus of this study. We aim to provide insights for Timor-Leste CSOs collaborating to advance gender equality and build WASH systems led by Timorese people and supported by international donors and agencies. This article reports on an empirical study conducted in Timor-Leste (from 2018 to 2021) about selected partnerships developed across WASH and gender equality CSOs, with an in-depth focus on partnerships developed as part of a WaterAid-facilitated project to strengthen the WASH system in Timor-Leste.

2. Theoretical framing of the study

Focusing on locally led WASH and GESI CSO partnerships and collaborations, this study draws on and contributes to the literature and discourse about post-development theory, including critical localism and working contingently. We have integrated feminist, empowerment, and development theories related to conceptions of power and empowerment into the study design and analysis process and offer five foundational theoretical framings for this study: (i) post-development; (ii) critical localism; (iii) contingency theory; (iv) empowerment; and (v) CSO partnerships. Each provides a basis and rationale for an empirical study on CSO partnerships in Timor-Leste and is explained below with reference to partnerships and collaborations for development outcomes.

2.1. Post-development

Post-development theorists have long critiqued the notion of development as a Northern discourse that obscures local knowledge, systems, and practises (Escobar, 1995a,b). Escobar called for the development agenda to create intellectual space for a local agency to assert itself and for the recognition of the importance of grassroots movements (Escobar, 1992). Practical post-development theorists place significant weight on community-based initiatives and social movements. As Schoneberg offers: “Post-development demands the questioning of dominant discourses, representations, and power/knowledge nexus, and argues that this can only be achieved by local, i.e. Southern, movements and organisations themselves” (Schoneberg, 2017, p. 605).

In a study on aid and development trends in Timor-Leste in McGregor (2007) drew on the practical post-development approach adopted by Latouche (1993), Escobar (1995a,b), and Gibson-Graham (2005). McGregor found that post-development theories had ‘successfully challenged many of the ways in which we think about development but have yet to substantially influence development practice’ in Timor-Leste (2007, p. 155). While post-development theory questions the very desirability and centrality of the notion of “development,” the urgent humanitarian and sustainability challenges facing the world are undeniable. So, what are the alternatives to conventional and Northern-led development? In his study of development paradigms in Timor-Leste in 2007, McGregor found that “The international and individualised partnerships between institutions and communities would seem to hold the biggest potential for cross-cultural support and understanding” (2007, p. 167). Our study sought to explore one of the dimensions of the post-development social change agenda, which sees “local, pluralist and solidaristic initiatives [as] central, and where connexions to place, local knowledge and the non-human are highly valued” (Roche et al., 2020). A “localism,” to which we now turn.

2.2. Critical localism/localisation

Externally led development interventions are often poorly informed by local knowledge in terms of language, culture, history, and politics. The international humanitarian and development sector has long been criticised for ignoring local knowledge, being top-down and Northern-driven (Escobar, 1992). Local preferences and ways of working are often different from Western or “Northern” ideas and the practise of development agencies and may be overlooked by larger, better-resourced International Non-Governmental Organisations (INGOs) (Crewe and Harrison, 1998; Guttenbeil-Likiliki, 2020; Roche et al., 2020). Weak “local ownership”' and gaps between local and international priorities are major factors explaining the failure of many externally imposed state building interventions, such as that implemented by the UN in Timor-Leste after the violence and destruction of the Indonesian withdrawal in 1999 (Chopra, 2002).

In response to the critique of top-down approaches to development, “localisation” (or “locally led”) has emerged as a contemporary reform in the development sector. Drawing on the work of McCulloch and Piron (2019) and Booth and Unsworth (2014), Roche et al. define locally led development as “driven by a group of local actors who are committed to a reform agenda and would pursue it regardless of external support” and “who are local in the sense of not being mere implementers of a donor agenda” (2020, p. 137).

Although local participation has been a long-held guiding principle for development since the 1970's, it is elusive (Eversole, 2003). Despite progress in visions of and commitments to localisation, implementation is “patchy at best” (Roche and Denney, 2021, p. 23). Local partners are often utilised in a way that reinforces existing paradigms of donor power and North over South rather than transforming development practise (Roche and Denney, 2021, p. 23; Guttenbeil-Likiliki, 2020). Critics of top-down development call for critical engagement with the concept of “local” in terms of how power is shared but also warn against romanticising and over-validating the local level (Mac Ginty, 2015). In this vein, the localism agenda has been criticised for proliferating partnerships with “‘local” actors that remain entirely transactional in nature but provide a nod to wider donor trends’ (Smith, 2017, in Roche and Denney, 2021, p. 25). Critical localism, in comparison, challenges weak attempts to engage or empower at the local level, in some cases over-validating local norms at the expense of more flexible and activity-oriented (rather than place only) interpretations of the local (Mac Ginty, 2015). Broader conceptualisations of the local include systems of beliefs and practises that “loose communities and networks may adopt that change over time and with circumstances” (Mac Ginty, 2015, p. 851). By adopting a critical lens to local engagement, the present study investigates whether or not collaborative, genuine, and effective partnerships with local Timorese CSOs improve and strengthen outcomes for WASH and GESI programmes and organisations. It focuses on power, knowledge diversification, local beliefs, and norms and practises.

2.3. Contingency theory and CSO partnerships

Contingency theory looks at how contextual factors shape organisational outcomes and asserts that organisational effectiveness depends on the organisation's ability to adapt to its environment. Turbulent environments require organic organisational approaches in the development sector to achieve their aims (Sauser et al., 2009). While contingency theory has evolved since the 1950's, more recent applications, such as that developed by Honig and Gulrajani (2018), offer three principles of contingency theory. Development actors must (i) focus on better understanding the local contexts in which they operate; (ii) adapt or tailor development initiatives to local contexts during project design; and (iii) change projects and programmes in line with how contexts change (Honig and Gulrajani, 2018, p. 69–70). To be effective, working contingently must be done in association with the autonomy,1 motivation, and trust of people working directly with communities and change agents. Together, these factors provide a pathway to advancing contingent ways of working with a focus on the individuals themselves within a context they uniquely understand (Honig and Gulrajani, 2018, p. 74).

Honig and Gulrajani (2018) emphasise the importance of trust, especially of field-level staff, in order to adapt to changing local circumstances. Trust is an essential component of working contingently, and “contingent ways of working need to be coaxed, not commanded” (Honig and Gulrajani, 2018, p. 71). In the WASH sector in Cambodia, localisation has been found to enhance the effectiveness of leaders through building on existing institutional arrangements and adapting to a variety of participants' needs (Nhim and Mcloughlin, 2022). However, increased autonomy alone is not a panacea. It needs to be supported carefully by tailored feedback loops that leverage positive change (Meadows, 1999). Honig and Gulrajani (2018) call for a fundamental rethink of where decision-making needs to take place to achieve the changes that development agencies aspire to, in line with the critical localism and post-development views of development outlined above.

2.4. Gender, empowerment, and movement building: “Power with”

CSO partnerships and social movement building are essential for advancing gender equality and inclusion in all societies (Htun and Weldon, 2018; MacArthur et al., 2022; Siscawati et al., 2022). Seeking renewed possibilities for social change in gender equality and associated issues, such as ending violence against women, international women's advocates have pursued partnerships with national women's movements (Batliwala, 2012; Horn, 2013; Guttenbeil-Likiliki, 2020). A stronger focus on supporting local or national women's organisations and movements follows several decades of feminist principles being overlooked in favour of “women in development” programmes and the “NGO-isation of feminist movements,” which have failed to bring about the hoped-for changes (Batliwala, 2012, p. 17–18). The Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development, for example, emphasised that local women's movements grounded in local struggles and experience are central to transforming current approaches to development. Pressure and action by local women's movements have the capacity to bring about improvements on substantive issues of concern to women within their own communities (Rajbhandari, 2014; Grant et al., 2019b; Niner and Loney, 2019).

Empowerment theorists also see that engaging local women's organisations and movements is a key form of power and an important domain of change. VeneKlasen and Miller (2002), Eyben et al. (2008), and Taylor and Pereznieto (2014) included “power with” in their frameworks as one of four key aspects of empowerment. “Power with” highlights the importance of the process of movement building and partnerships to agitate for rights and change social norms and conditions. As explained by VeneKlasen and Miller in 2002 (p. 55):

“Power with” involves finding common ground among different interests and building collective strength. Based on mutual support, solidarity and collaboration, “power with” multiplies individual talents and knowledge. “Power with” is a key tenet of empowerment, by building voice and increasing power through acting together around mutual interests. Advocacy groups seek allies and build coalitions drawing on the notion of “power with.”

The consideration of “power with” as a central tenet in empowerment theory invites us to look more deeply at the literature on coalitions and partnerships within feminist and women's movements, and how it might be useful for advancing not only WASH outcomes but also gender equality outcomes through WASH programming. We now present the relevant literature related to partnerships as another foundational body of work that informed the design of our present study.

2.5. CSO partnerships and the WASH system

Partnerships, coalitions, and networks are understood to be essential to the collective action required to address global challenges (Roche and Kelly, 2014; Doerfel and Taylor, 2017). Partnerships, such as those between North–South CSOs, can be understood to be: “… a response to complex problems in which partners can build on each other's comparative advantages through a rational division of labour. Through their complementary roles, partners can achieve goals they could never reach by themselves” (Elbers and Schulpen, 2013, p. 50).

Well-managed civil society partnerships can yield a range of benefits, including access to the political process, organisational legitimacy, and tangible and intangible resources (O'Brien and Evans, 2016). However, these benefits can only be realised if the power dynamics between the partners are addressed and considered meaningfully. A study on power dynamics between Northern and Southern women's movements and organisations found that Global North organisations often lacked contextual and cultural understanding of the focus country and communities and tended to follow their own agendas with little input from local organisations (Guttenbeil-Likiliki, 2020). It found that “elite feminism” tended to favour well-established organisations. Global South organisations faced uncertain financial and other sustainability factors when accountability and transparency were viewed as one way, and dependency and donor-and-beneficiary dynamics were perpetuated (Guttenbeil-Likiliki, 2020, p. 13). Similarly, a study of Northern and Southern NGO partnerships in Ghana, India, and Nicaragua found that Northern NGOs unilaterally set the rules of the partnerships even though informal rules allowed for more flexibility (Elbers and Schulpen, 2013, p. 48). These studies reveal the pitfalls of many North–South partnerships that reinforce existing power dynamics and the importance of evolving flexible partnerships and a broadening of the types of partnerships to include supporting local networks and coalitions. Until now, research has not been conducted on the bilateral partnerships formed between WASH and gender-focused organisations (North–South or local partnerships), which this study seeks to redress.

The growing complexity of the development landscape calls for “multiple perspectives and collective action” to address wicked problems such as human rights violations and climate change (Roche and Kelly, 2014, p. 60). “Traditional” aid relationships and projects need to shift towards critical localism agendas by engaging local CSOs to encourage policy agendas that focus on empowerment and voice, support domestic policy processes that reduce inequality, and build broader support for inclusive policy interventions (Roche and Kelly, 2014, p. 61). Networks and coalitions are considered a potentially effective means to support a localisation agenda: “NGOs will need to move beyond unique partnerships as bilateral relationships with a single “partner” or counterpart, but rather become simultaneously engaged with multiple actors through networks, coalitions and alliances” (Roche and Kelly, 2014, p. 61). Smith et al. (2016) also recognise that NGOs have catalysed progress in global health governance due in part to their relative independence, links to populations most affected, and a range of functions that they undertake, including building diverse coalitions and advocacy roles.

A number of studies have explored the emergence and success, or otherwise, of civil society coalitions related to driving social justice issues (Mizrahi and Rosenthal, 2001). Coalitions are more likely to change gender norms when formed in response to local events and critical junctures; are locally driven and owned; share a common purpose and values; and have adaptive and regularly renegotiated distributed leadership (Fletcher et al., 2016; Spark and Lee, 2018). In her review of how leaders collectively influence institutions, Nazneen (2019) found that the way in which coalitions can bring about positive change is influenced by their sources of material wealth, their collective strength, and their ideational collective power (i.e., ability to shape ideas and build legitimacy).

2.5.1. Rights-holder organisations: Part of the WASH system

WASH system strengthening is increasingly a focus for international civil society organisations and local WASH actors, as opposed to working purely at a project and infrastructure level in many contexts. Valcourt et al. (2020, p. 2) define a WASH system as “a collection of all the factors and their interactions which influence WASH service delivery within a given contextual, institutional or geopolitical boundary.” A focus on the system, and its interrelated parts, stems from evidence pointing to a high level of WASH project failure when human behaviours and system sustainability, as well as the complex relationships and varied actors that make up the WASH sector, are not adequately considered (Moriarty et al., 2013; Neely, 2019; Grant et al., 2020; Hollander et al., 2020; Valcourt et al., 2020; Huggett et al., 2022, p. 17–28).

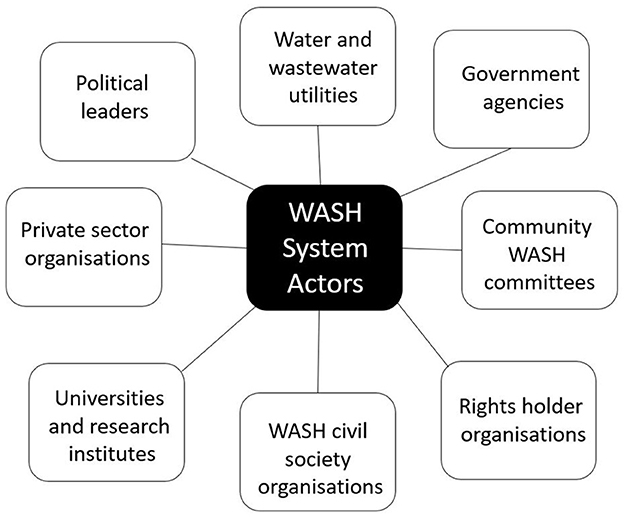

Partnering with diverse rights-holder organisations (RHOs) has become part of a broader trend within the rural water sector in low- and middle-income countries in an attempt to move away from infrastructure-focused models towards more integrated service delivery models. Service delivery models are conscious of the combined effect of a range of factors and how a range of governance and behavioural factors affect WASH delivery and success, including gender equality and social inclusion (GEDSI) (Huggett et al., 2022; Water for Women, 2022). WASH system strengthening is understood to involve working with, supporting, and strengthening the institutions and actors that are part of the broader WASH system, as well as the relationships between them (Jenkins et al., 2019; Nhim and Mcloughlin, 2022, p. 1–12). While the WASH system includes water utilities, government agencies, and CSOs, other actors are increasingly recognised as integral to the system, such as RHOs, including women's organisations, organisations for people with disabilities, and sexual and gender minorities organisations (Figure 1). As these actors work together in a range of ways, various support systems, or “building blocks,”2 are needed to facilitate their optimal functioning and interrelationships (Huston and Moriarty, 2018). Systems approaches are considered ways to not only tackle the complexity of WASH systems and address systemic failures but also to promote inclusion. Kimbugwea et al. (2022, p. 69) argue that adopting a system approach underpinned by human rights principles can advance progress towards inclusive and sustainable WASH for all. A range of tools and approaches has been developed within the WASH sector to guide practitioners and policymakers in how to consider and influence the many interconnected factors that make up the WASH system (Casey and Crichton-Smith, 2020; Valcourt et al., 2020). However, guidance to support partnerships between RHOs and WASH actors is nascent.

3. The Timor-Leste context: WASH and GESI CSOs

3.1. The WASH system in Timor-Leste

WASH services are delivered by a range of actors in Timor-Leste, including government agencies, water utilities, CSOs, and small-scale private sector actors (Willetts and Murta, 2015). Efforts to strengthen the WASH system in Timor-Leste have been undertaken by CSOs (such as the INGO WaterAid) looking to work with, influence, and engage the WASH system as a whole, including several levels of government (from the national to the suco or village level), utilities, businesses and local CSOs. Efforts have also been made by a range of WASH actors to improve gender-equality outcomes, shift gender norms, and empower women and girls in the development and delivery of water and sanitation programmes (Grant et al., 2019a; Huggett et al., 2022).

While governments are regarded as “rights duty bearers” globally (Carrard et al., 2020), they often fail to ensure delivery of effective WASH services, especially in challenging contexts such as those with disparate communities, mountainous terrains, and populations who do not have a high degree of disposable income. The local government bodies across 14 municipalities3 in Timor-Leste are highly diverse and home to different ethnolinguistic groups. These municipalities are further divided into 67 posto (administrative posts, formally sub-districts) and 442 localities or suku led by local councils headed by a xefe (chief). Local governance is a “hybrid” and complex form, embracing both newly introduced democratic processes and customary and ritual lisan practises (Cummins, 2010).

Local demand and donor focus on improved WASH services have resulted in CSOs and governments focusing more on inclusive programming, with the aim of achieving health and wellbeing outcomes for all members of the community. CSOs support and amplify women's and diverse perspectives, and their advocacy and engagement with government helps to hold to account those responsible for providing safely managed WASH and sanitation services. For these reasons, international and local CSOs, such as WaterAid in Timor-Leste, along with community and women's organisations, have become a key part of the ecosystem to deliver and work with governments to provide WASH services in Timor-Leste. Increasingly, CSOs see the benefits of collaboration between themselves and other organisations working on social justice issues for the intertwined and mutually beneficial goals of strengthened WASH and GESI (Water for Women, 2022).

3.2. GESI and civil society movements in Timor-Leste

The 2002 Constitution of Timor-Leste formalised equality between women and men in law. At the time, there was broad general support for gender equality, but in everyday reality, there are significant differences between the status of men, women, and non-binary gender expressions (Niner, 2018b; Niner and Nguyen, 2022). While many East Timorese in contemporary society believe women's and men's roles are balanced, from a political-economy or feminist-analysis perspective, gender relations remain inequitable (Niner, 2018a). Disparities in economic indicators are reflected in women's low substantive political participation in the labour force, the high rates of violence against women, and unequal education outcomes at higher levels for women and girls (Wild et al., 2022).

In documenting three key phases of civil society development in Timor-Leste, Wigglesworth (2013) explained that the political crisis of 2006–08 precipitated an analysis of Western development models and gave rise to activists promoting traditional practises and culture through development models that engaged better with local communities (p. 70). However, the way in which gender issues has been incorporated into these new approaches is still emerging.

Timor-Leste has an active women's movement comprising a coalition of local women's CSOs and key female leaders and parliamentarians, many of whom played significant roles in the independence movement. The kernel of an East Timorese women's movement was created in the early 1970's with the establishment of the Popular Organisation of Timorese Women (OPMT) as part of FRETILIN, the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor, which was opposed to colonial rule. Women are proud of the roles they played in the struggle for self-determination. As their role is yet to be fully recognised, the women's movement continues to advocate for this recognition (Niner and Nguyen, 2022).

After the end of the Indonesian occupation, East Timorese women continued to provide the bulk of care for their families and communities under the most difficult of conditions while also building up a strong movement for women's rights that drew upon the networks and alliances established during the occupation period (Wigglesworth, 2013). The first National Congress of the Women of Timor-Leste, held in June 2000, established Rede Feto, the mainstream umbrella organisation for the women's movement, and developed a Platform of Action for East Timorese Women. Held every four years, the Congress has provided a road map for action (Rede Feto, 2007). An admirable list of achievements includes gender mainstreaming policies, a gender quota resulting in 39% of women in the national parliament, a progressive domestic violence law, and the bolsa da mae social protection programme for mothers.

However, in Timor-Leste, strict binary gender roles undermine human development and equality goals. There is much anecdotal evidence of violent discrimination against LGBTQI+ people, who do not conform to these expected roles (Niner, 2022). Solidarity extended by Rede Feto in publishing a report documenting such abuses was a watershed moment for the LGBTQI+ movement in contesting conservative gender relations and values of the wider society. The movement advocated for the acceptance of and respect for the human rights of LGBTQI+ peoples through successful alliance building with other progressive social forces in society. In support of Gay Pride celebrations, the Prime Minister and President urged Timorese to create an inclusive nation and accept people with all sexual orientations, gender identities, and expressions (SOGIE); other senior politicians declared similar support (Niner, 2022). This illustrates the importance and role of CSO partnerships and coalitions in support of mutual agendas such as WASH and GESI.

As presented above, literature is available on the importance and role of CSO bilateral partnerships and coalitions in support of localist and contingent ways of working and the dynamics of the women's and LGBTIQ+ movements in Timor-Leste. Yet, little has been written on the WASH sector in Timor-Leste academically and nothing, until now, on the burgeoning relationships between the WASH sector and the women's and LGBTIQ+ movements.

4. Materials and methods

Our research design was primarily qualitative. It included three key data collection components: (i) a data collection workshop with 30 CSO representatives from 16 organisations in Dili to inform the research design and participants as well as collect data on drivers, benefits and challenges of CSO partnerships, (ii) a longitudinal research component using semi-structured interview guides over 2.5 years with two rounds of primarily in-person interviews with WaterAid Timor-Leste and four of their local GESI partners (iii) semi-structured interviews with another 18 civil society organisations. Participating organisations included local WASH organisations (n = 2), international WASH organisations (n = 3), local GESI organisations (n = 17), and international GESI organisations (n = 1). International organisations were defined as those that had offices and headquarters in another country, while local organisations were defined as born or based in Timor-Leste. Combining all participant types, 23 organisations were interviewed for the predominantly qualitative study. Our sample size was informed by Hagaman and Wutich (2017, p. 36), who found that ~20–40 interviews were needed to reach data saturation for all metathemes across data sets.

The organisations WaterAid Timor-Leste partnered with and that were involved in the longitudinal component of the study included three local organisations and one INGO:

A. Dili-based CSO focusing on supporting women and girls in engineering (local organisation).

B. Community development and WASH CSO based in Manufahi with eight staff (local organisation).

C. International CSO with a focus on gender equality (international CSO).

D. Women's organisation established since the Indonesian occupation and comprising five staff. Women in the organisation were part of the Independence movement (local organisation).

Participating organisations were purposefully sampled, drawing on the knowledge of the Timorese research team, WASH, and gender equality CSOs. Inclusion criteria included local and international organisations working on (a) GESI issues or (b) WASH issues. We used a single semi-quantitative interview template for the longitudinal study to capture changes in the partnership dynamics over time. Questions were asked about the purpose, nature, and development of the partnership between the organisations. Drawing from the literature (as outlined above), our questions related to power dynamics, decision-making processes, values, and typologies of partnerships. A major change occurred in 2020 with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to significant adjustments in programmes, less travel, and changes in some staff members in a number of organisations. However, despite these challenges, we conducted interviews in person in Dili, Liquisa, and Manufahi Timor-Leste, with a small number by phone when meeting in person was not possible. We conducted online joint analytical processes and joint development of recommendations for policy and practise with primary research partners (described below).

Notes during interviews were taken in Tetum and transcribed in summary into English, potentially losing some of the details and nuances of the conversations between researchers and interviewees. The English notes were then used as the basis for the analysis, though Timorese researchers were involved in coding and sensemaking processes to ensure the reliability of interpretations. The quality of the transcriptions of notes taken in Tetum which were transcribed and summarised in English was assured through timely reviews of notes, feedback, and regular phone conversations with Timorese researchers, so that any gaps were picked up early and transcripts could be improved. Given telecommunications issues in Timor-Leste, Whattsapp phone calls were most useful for these regular check ins and discussions about transcripts.

The analysis of the types of partnerships drew on a framework we adapted from Winterford (2017), who drew from Moore and Skinner (2010). It described a spectrum of collaborations from “independent,” where organisations operate separately with minimal interaction, to “collaborative,” where organisations are highly committed in a longer-term and formalised partnership, as described below:

• Independent: Organisations operate independently.

• Cooperative: Organisations remain independent but network and share information; low commitment; informal arrangements (no memorandum of understanding or contracts in place, for example).

• Coordinated: Some joint planning is conducted between organisations; project-based coordination; memorandums of understanding (MOUs) or contracts may be in place.

• Collaborative: Organisations share culture, visions, values, and resources; joint planning is undertaken; a high level of commitment by both parties is demonstrated; the partnership is formalised through agreements, contracts and the like.

Analysis was also informed by an inductive and deductive thematic coding undertaken in Dedoose and coding was conducted primarily by the Timorese research team members with quality assurance and contributions from the lead research team members to ensure reliability and trustworthiness. A codebook was developed by four data analysts, and was inductive and deductive, based on the research questions. Researchers also conducted thematic analysis (by hand) with the translated transcripts, in order to validate findings emerging from the Dedoose coding process. While COVID-19 travel restrictions limited the Australian research lead's ability to engage in person with the Timorese research team, we managed this through a series of online workshops and co-analysis processes with 10 members of the broader research team in Timor-Leste.

Deductive coding and thematic analysis was conducted with the transcripts to and informed by the research questions:

(RQ 1) What are the drivers, benefits, and challenges of engagement between WASH sector CSOs and gender equality and women's rights organisations?

(RQ 2) How can CSOs partner more effectively to maximise WASH, gender equality and inclusion outcomes in the context of a localisation agenda?

We provided all interviewees with information sheets outlining the purpose of the research and how the information they shared would be used and ensuring confidentiality. Interviewees were provided with this information sheet in hard copy and it was emailed to them prior to the interview. A consent form was read out by the interviewer at the start of the interview and participants were given the option to stop at any point without providing a reason, as well as withdrawing from the research process at any time. Consent was provided by way of interviewees signing the consent form provided. Ethics approval for this research was obtained (approval number UTS HREC REF NO. 2015000270).

5. Results

The following results stem from interviews with women's and WASH organisations that were both local and international and from all the interviews conducted across the study (n = 23). Interviewees provided insights into the types of collaborations underway between WASH and GESI organisations and the drivers, benefits, and challenges of collaboration between organisations of different sizes and types pursuing interrelated but different objectives.

5.1. Types of collaborations between WASH and GESI organisations

Collaborations took various forms, including programme implementation, contractual relationships, knowledge and information sharing, and informal networking. Partnerships between WASH and GESI CSOs were found to be driven by organisations wishing to strengthen the WASH system overall in Timor-Leste and achieve tangible gender equality outcomes, especially for women and girls. Of those interviewed for the project (n = 23), 14 were in some type of WASH–GESI partnership or engagement, and 9 others expressed an interest in collaborating in the future, though to varying degrees; 8 organisations reported having a formal partnership agreement in place (MOUs, funding arrangements, or contracts).

Two organisations described national-level forums in which WASH and GESI organisations shared information and discussed ideas together, such as the Forum Be'e Mos (Clean Water Forum), led by the National Directorate of Water and Sanitation Services (DNSAS), and the WASH and gender discussion forum led by the women's CSO, Fokupers.

Most organisations (5 out of 9) who were already partnering or connecting across WASH and GESI organisations described their current partnership as “cooperative,” and the others (4 out of 9) described it as “coordinated,” according to the spectrum used in this research (Figure 2). Most of the organisations interviewed for the longitudinal component of the study (3 out of 5) described their partnership as collaborative or between coordinated and collaborative, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. CSO interviewees involved in WASH and GESI partnerships identifying where their partnerships sit against a spectrum, adapted from Winterford (2017) and based on the work of Moore and Skinner (2010).

The research did not point to any model being more successful than the others. However, interviewees did express an interest in moving towards more “collaborative” types of partnerships characterised by a shared organisational culture, visions, values, and resources; joint planning and delivery of some services; and a high level of commitment from partners.

5.2. Drivers for partnerships

Partnerships between WASH and GESI organisations were shown to have been driven by a range of factors, including mutual agendas, observed community WASH needs, and commitments to inclusive practises. The most notable driver was “complementary agendas” due to the understood intersection between WASH and GESI objectives. Six GESI organisations that worked closely with communities were motivated to cooperate with WASH organisations as a result of the urgent and unfulfilled WASH-related needs that they saw and heard about in communities, particularly for women and girls. Responding to gaps in services was a key driver for collaboration, with organisations reporting they had undertaken partnerships to address gaps in government services, including combining resources and funds to meet community needs in remote villages.

The perceived mutual benefits reported by WASH and GESI interviewees were: increased economic empowerment through WASH both directly for women's business opportunities (e.g., water to produce coconut oil and vegetables) and indirectly by improving people's health and hence their productivity; less violence towards women and LGBTIQ+ people, who face bullying while trying to meet their daily WASH needs; improved family harmony by reducing tension around WASH-related work and roles, including decreasing gender-based violence through a better understanding of gender equality concepts at the community level and safer WASH access.

Mutual advocacy agendas were also expressed as key drivers for collaborations between organisations and across the sectors. For example, interviewees reported that they wished to utilise connected advocacy agendas to share WASH information at the community level (through and by local leaders) and to lobby the government at the national level to improve WASH services. Interviewees also saw that partnerships helped to improve the sustainability of WASH project outcomes through empowering women, shifting harmful gender norms, and improving the responsiveness of WASH services to people's real needs.

5.3. Benefits of partnerships

Regarding the drivers for collaboration, interviewees identified at least 14 distinct benefits of WASH and GESI partnerships, relating to three main areas: (1) increasing participation and inclusion of women in WASH programmes and related decisions, (2) mutual learning and capacity building, advocacy opportunities and connexions with government, and (3) shifts in gender norms (changing perceptions of roles and responsibilities related to WASH) (Table 1). Organisations within existing WASH and GESI partnerships reported positive power dynamics between CSOs, positive working relationships (including good communication styles and organisational policies), and the supportive nature of networks and bilateral partnerships in Timor-Leste.

Table 1. Benefits reported by CSO interviewees (n = 23) of partnerships between WASH and GESI organisations.

One national GESI organisation described the tangible benefits its members gained from the collaboration with a WASH organisation thus: “Some of our members in seven districts have already accessed clean water. For example, in one community, the water arrived at their house. That is the result of working together between [WASH organisation and GESI organisation].” Two GESI organisations described their positive working relationships with a larger WASH CSO: “We have a good working relationship because if there are some issues or a problem occurs, we try to resolve it [together].” The interviewee explained that this relationship began on a relatively equal footing: “they [the WASH CSO] did not come and dictate what they wanted. Instead, they came here to present to us about their project related to disabled people and that they wanted to work with us … we made a plan together with them and they support us with money, and we implemented our plan.”

A benefit of one partnership was the increased connexion between WASH partners and government actors at several levels. These CSO-government relations were facilitated by capacity-building initiatives for women's organisations so that they could confidently represent WASH issues themselves, thereby increasing their capacity to talk with government agencies and representatives. As one interviewee reported: “their activities have influence at the national level. They did different types of advocacies about decision-making with consideration of women's suffering regarding sanitation and hygiene.” In this case, the disproportionate challenges women face to use toilets instead of openly defecating, including increased risk of rape and violence, as well as to manage menstruation, were explained to political leaders and decision-makers. Advocacy benefits from the collaboration in one case resulted in GESI partners providing their suggestions on the state budget related to sanitation and hygiene, as noted by one interviewee: “Women's groups speak out about WASH problems in the communities. I think the big change is that this community aspiration reached the Parliament. They also had a meeting with the women's parliament group [GMPTL].”

5.4. Challenges of partnerships

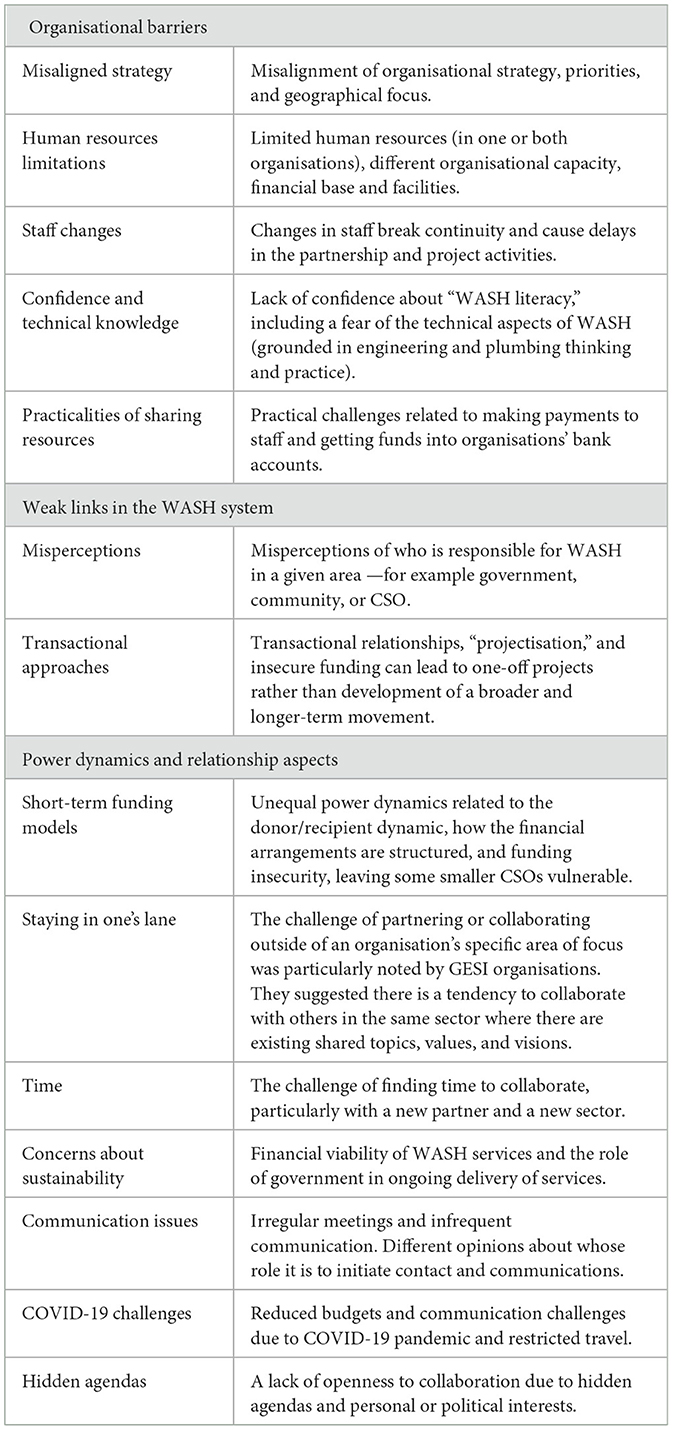

Establishing and maintaining partnerships between distinct organisations (and between individuals) requires continuous attention and improvement, facilitated through good communication and trust. This study looked closely at bilateral partnerships rather than coalitions; consequently, the lessons learned focus on partnerships between WASH and GESI organisations, though they could be considered beyond these particular types of relationships. Interviewees reported 14 distinct challenges (Table 2), broadly related to three main factors: (1) organisational barriers that prevented realisation of outcomes; (2) weak links in the WASH system; (3) power dynamics and relationships. These are elaborated below.

Table 2. Challenges reported by CSO interviewees (n = 23) of partnerships between WASH and GESI organisations.

Organisational barriers included a misalignment of organisational strategy, priorities, and geographical focus; limited human resources practises, organisational capacity, and facilities, particularly within smaller CSOs; and changes in staff, which broke continuity and caused delays in the partnership and project activities.

Weak links in the WASH system were reported to be related to misperceptions of who was responsible for WASH and therefore a reticence to get involved if it was perceived to be outside the domain of the CSO; transactional relationships and insecure funding leading to short-term projects rather than longer-term movement building; some functional barriers around providing funds into partner bank accounts; and power imbalances related to organisational capacity and size, leaving some smaller CSOs feeling vulnerable.

There were reports of a lack of openness to collaborate due to hidden agendas and personal or political interests. Others identified the challenge of partnering or collaborating outside what is perceived to be an organisation's specific area of focus. Interviewees mentioned a tendency to collaborate with others in the same sector and where there were shared values and visions and difficulty finding the time to collaborate, particularly with a new partner or sector. Communication challenges also arose due to irregular meetings and infrequent contact, and sometimes there was confusion about who needed to initiate the communication.

Funding dynamics, financial sustainability, and operational issues (related to accessing bank accounts) were identified as challenges in some WASH–GESI partnerships. For example, One GESI CSO reported that it faced considerable funding insecurity: “We don't have a permanent donor.” A WASH organisation felt that CSOs needed support to become more financially sustainable: “… if all are based on projects, they cannot sustain themselves. We need to think about this so that CSOs can be self-sustaining and developed.” Another funding-related challenge was noted in terms of how proficient organisations are at writing proposals. One GESI organisation explained that funding often goes to those who can prepare the required proposals rather than those who are best placed to do the work. This disadvantaged smaller, local-level organisations in Timor-Leste: “There are a lot of requirements from the funding agency, and people do not have good skills to prepare the proposal.”

Recommendations for supporting more effective collaboration included:

• Strengthening joint planning processes.

• WASH and GESI training.

• Ensuring both partners understood and could use data available on access to and quality of WASH.

• Ensuring both partners understood gender-norms issues.

Other suggestions included targeting funding at the existing priorities of gender equality CSOs and for organisations to focus on their internal capacity. Regular, open communication between partners was emphasised as vital, including partnership check-in processes, addressing staff changes (which may involve rebuilding relationships), and emphasising the importance of individuals for partnership continuity and growth.

6. Discussion

We now reflect on the research findings with reference to the theoretical perspectives presented above, including a focus on women's empowerment through collective action, localism, post-development thinking, and contingency theory. We make two key points in relation to the results and the literature presented. Firstly, bilateral partnerships between international and local organisations yield mutual benefits and strengthen local-level civil society. Such partnerships support contingent ways of working in terms of building trust and autonomy at the local level. We also found evidence that partnerships between rights-holder and WASH organisations strengthened the WASH system, thereby contributing to a transition to post-development WASH services (beyond WASH projects/programmes run by INGOs). Secondly, uneven power dynamics exist in some cases and must be navigated carefully for working contingently and realising localism agendas. Each of these two key findings is discussed in turn below.

6.1. Mutual benefits of working contingently to strengthen the WASH system

The benefits of development partnerships are well-documented and have become common and expected modalities for aid donors and practitioners (Roche and Kelly, 2014). CSO partnerships literature is validated by the present study on WASH and GESI partnerships in Timor-Leste, especially in terms of O'Brien's observations that genuine and mutually beneficial partnerships can yield a range of benefits, including identity reinforcement, access to the political process, organisational legitimacy, and access to tangible and intangible resources (O'Brien and Evans, 2016). The three main themes of benefits (Table 1) that WASH and GESI organisations identified in their partnerships related to (i) increasing participation and inclusion, mutual learning, and capacity building, (ii) advocacy opportunities and connexions with government, and (iii) shift in gender norms, perceptions, and responses. The collective action, partnership arrangements, and focus on system strengthening driven by WaterAid and their direct partners can also be seen as an example of “power with” (VeneKlasen and Miller, 2002, p. 55) in that they found common ground among different interests and built collective strength. The benefits reported by CSOs in partnerships (particularly the longitudinal component) were found to be related to strengthening collective action, local-level pluralist governance, networks, and partnerships with heightened advocacy power and influence.

Larger international CSOs, such as WaterAid, tend to support Honig and Gulrajani's (2018) call for more contingent ways of working grounded in a deeper understanding of the local context, greater trust and autonomy of local actors, and adaptive ways of working. Yet, working contingently can only happen if the local partners are empowered (and supported in ways that are meaningful to them) and power dynamics are addressed at the start of and during the partnership. In our study, organisations reported that their partnership was founded on positive and flexible working relationships, communication styles, and organisational policies. This seems to indicate some of the characteristics that Honig and Gulrajani (2018) discuss in terms of increased autonomy and trust at the field level as essential components of contingent ways of working.

The partnerships in Timor-Leste at the centre of this study provide another example of working and changing aspects of the WASH system and supports Huggett et al. (2022, p. 38) finding that “integrating GEDSI within system-strengthening programming provides useful opportunities and leverage points for addressing systemic barriers to inclusion and empowerment.” Our study also supports the finding of Kimbugwea et al. (2022) that system approaches (when underpinned by human rights principles) can advance inclusion outcomes in WASH programmes. The authors' SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) regarding how a WASH programme in Cambodia and Uganda engaged with WASH system building blocks (2022, p. 75) found weaknesses in consultation and participation with women and marginalised groups, as well as limited understanding and space to discuss human rights to water and sanitation. Partnerships with RHOs are one way to help address these weaknesses and thereby increase the confidence and involvement of women and CSOs representing marginalised groups. Similarly, the benefits reported by the CSOs interviewed for our study included: increased participation of women and people with disabilities in the decision-making and delivery of WASH services; secured WASH rights for people with disabilities by elevating their needs to relevant parties (government and WASH organisations); increased information about and access to WASH services for women and people with disabilities (Table 1).

As pointed out by O'Brien and Evans (2016) and Guttenbeil-Likiliki (2020), the power dynamics between partners must be addressed and considered meaningfully before the benefits of partnerships can be realised. Our study supported this finding, concluding that power dynamics must be openly understood, discussed, and navigated in WASH and GESI partnerships. In addition to power dynamics being challenging for local and international CSOs to manage between themselves, organisational barriers (related to communications, staff continuity, and administrative coordination) and weak links in the WASH system (contested views of who is responsible for WASH and therefore reticence to get involved) were also identified as considerable challenges to well-functioning partnerships. As found in previous studies on North–South CSO partnerships, we observed challenging dynamics related to smaller local organisations' dependency on larger international ones. These dynamics indicate that the nature of development funding and associated power relations makes attempts to promote more locally led development difficult in practise. Yet, through the partnership models employed amongst organisations in this study, local-level organisations' capacity and independence were enhanced, indicating that, in future, these partnerships may contribute to notions of plurality and solidarity. This trajectory is supported by McGregor's study, which concluded that “Although some parts of the development architecture reviewed are flawed from a post-development perspective, particularly programmes that are broad in scale or have pre-determined project outputs and timelines, other initiatives, such as community or institutional partnerships and small grants programmes, have much to contribute to post-development futures. They are potentially flexible, community-focused, supportive of alternative sociopolitical spaces” (2007, p. 168).

6.2. Navigating uneven power dynamics

Our study offers insights into the extent to which a post-development and localist agenda is being pursued through CSO partnerships in the WASH and GESI sectors. We drew on the work of scholars who identified the shortcomings of top-down and Northern-driven development agendas (Crewe and Harrison, 1998; Guttenbeil-Likiliki, 2020; Roche et al., 2020) but also those who call for a nuanced perspective when it comes to championing the “local” (Mac Ginty, 2015). While emphasising the centrality of Southern movements and organisations (Schoneberg, 2017, p. 605), Schoneberg's description of post-development theory questions dominant discourses related to the power and knowledge nexus. The design of our study supported Escobar's call for the development agenda to create intellectual space for local agencies to assert themselves (also a central tenet of contingency theory), and for the recognition of the importance of grassroots movements (Escobar, 1992). Nonetheless, we found that the relationship between most WASH and GEDSI CSOs largely reinforced dominant partnership models (i.e., larger donor organisations partnering with smaller local organisations). These models were characterised by larger CSOs (primarily consisting of Timorese staff and backed internationally) engaged with smaller more grassroots organisations that, in turn, depended on the larger CSOs for funding and support. The concerns raised by some smaller local CSOs about their own sustainability and that of their partnership (as a result of shorter-term project-oriented engagement) point to the dependence of these partnerships on funding from one of the partners. The question that begs an answer is the degree to which a genuinely locally led agenda is being pursued, given McCulloch and Piron's (2019) claim that localism requires a commitment to reform regardless of the existence of external support.

The challenges experienced within the CSO partnerships in this study point to the challenges of working contingently. Power dynamics are often hard to shift, especially when there are financial and North–South organisational power and financial differences. To this end, several organisations reported having some unequal power dynamics related to funding insecurity, which left some smaller CSOs vulnerable. These challenges in terms of partner organisations' size and capacity were also reflected in the Siscawati et al. (2022) study that looked at partnerships between similar actors in Indonesia. The Indonesian study revealed similar issues related to organisations having different sizes and structures, which may or may not align with those of their partners, as well as mismatched or limited financial resources and sustainability (Siscawati et al., 2022, p. 14). The challenges related to power dynamics shared by CSOs in our study had similarities with those found by Guttenbeil-Likiliki (2020) in terms of some elements of the dependency mentioned above (donor–beneficiary dynamics) and uncertain financial and other sustainability factors. However, our study did not find that the WASH and gender organisations connected to Global North organisations lacked contextual and cultural understanding of the focus country and communities, largely because the staff carrying out programmes in Timor-Leste for these organisations were predominantly Timorese. Our study also did not find that the partnerships pursued by WASH organisations favoured those from elite feminist organisations. Rather, the partnerships WaterAid developed with GESI organisations were largely nascent or grassroots organisations, which were the focus of this study.

Despite the challenges in partnerships and the power dynamics that sometimes underpin them, our study found that having strong and diverse partnerships with not only WASH organisations but also RHOs, such as women's organisations, organisations for people with disabilities, and sexual and gender minorities organisations, supports working contingently and contributes to a localist agenda. This is done by and through local-level organisations bringing their understanding of the local contexts in which they operate, helping to adapt or tailor development initiatives to their contexts, building social movements in support of gender equality (“power with”), and strengthening the multifaceted WASH system overall.

7. Conclusion

Forming genuine and mutually advantageous partnerships with local civil society organisations within the WASH sector and beyond is a key aspect of strengthening the WASH system and furthers critical localism, decolonising, and post-development agendas. The findings of this study support and validate the approach taken by international organisations such as WaterAid to build strategic partnerships and collaborations with diverse local rights-holder organisations, including those championing gender equality and inclusion. The interest shown by participants in this study to foster partnerships that are “collaborative” in nature requires a high level of commitment from partners and is in line with key tenets of localism and working contingently. Collaborative partnerships, in this sense, are conscious of where power is situated, whose agendas are being pursued, where trust is being fostered, and locally informed ways of working and communicating together.

Rights-holder organisations are important parts of the overall WASH System—a system made up of a range of organisations and actors, complex relationships, and the people who depend on and use water and sanitation services. The roles of rights-holder organisations assessed in this study with WASH organisations could be considered beyond bilateral CSO partnerships, and with other WASH providers (such as utilities and private sector actors) to advance GEDSI and pro-poor outcomes and strengthen the interrelated WASH system. There is also a need to look beyond bilateral partnerships and towards coalitional relationships and their potential to advance mutually beneficial outcomes with consideration of the transactional costs. Further, diversity of partnerships with other parts of civil society (e.g., youth, climate, ethnic minorities), as well as other types of actors (government and private sector), could support deeper and more transformational approaches to WASH programming.

Given the practical and advocacy benefits identified by interviewees in this study resulting from WASH and GESI partnerships, it is recommended that further research delves into what particularly enabled them to advocate for improved WASH services with government agencies, and which strategies were most successful. A case study approach via longitudinal monitoring and evaluation processes, process tracing or contribution analysis could be particularly useful for examining these reported benefits and impact pathways.

This research revealed a range of nuanced drivers, benefits, and challenges within the partnerships studied and found mutual benefits concerning advocacy efforts and aligned agendas for WASH and GESI capacity development. It also revealed that WASH–gender equality CSO partnerships in Timor-Leste are providing opportunities to hear more directly from community members and reach the most marginalised.

8. Limitations

COVID-19 hindered the research process by limiting our movement and access to interviewees. Some interviews and co-analysis workshops had to be conducted online, which was not ideal given the internet and phone challenges in Timor-Leste.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Ethics approval for this research was obtained (approval number UTS HREC REF NO. 2015000270).

Author contributions

TN and AV co-developed the scope of the research project, conducted and transcribed interviews in Timor-Leste, led coding analysis in Dedoose, participated in co-analysis processes with the research team, contributed to, and reviewed the article. MG responsible for the conceptual and theoretical framing of the research, led research design and tools development, designed and co-conducted inception and in-country data collection processes and pilots, and led team authorship of the article. SN led gender and LGBTIQ+ movements history framing and content, wrote sections of the article, conducted reviews, and contributed to conceptual framing of the paper. CR contributed to conceptual framing of the paper and conducted reviews. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Australian Government's Water for Women Fund under the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) funded this research (Grant Number WRA-034).

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank all interviewees and CSO partners, including CSOs who were part of the inception workshop in Dili in 2018 and participated in interviews. We would also like to thank core research participants from WaterAid Timor-Leste and WaterAid Australia; Feto Engineering Timor-Leste, GFFTL, CARE Timor-Leste, Feto asaun ba sustentabilidade (FAS), and International Women's Development Agency (IWDA). Thank you also to Caitlin Leahy and Isobel Davis for support with data analysis and Professor Juliet Willetts for her review of the article. Thank you to Jess MacArthur for support with drawing Figure 2.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Autonomy is explained by Honig and Gulrajani (2018, p. 71) as being greater freedom from external control and influence for both organisations themselves and individual agents.

2. ^Building blocks may include policy and legislation, regulation and accountability, finance, monitoring, planning, infrastructure, water resource management, and learning and adaptation (Huston and Moriarty, 2018).

3. ^Including 12 municipalities and the Special Administrative Region of Oecusse Ambeno (RAEOA). As of January 2022, there were 14 municipalities.

References

Batliwala, S. (2012). Changing their World: Concepts and Practices of Women's Movements, 2nd Edn. Toronto, ON: Association for Women's Rights in Development (AWID).

Booth, D., and Unsworth, S. (2014). Politically Smart, Locally Led Development (Discussion Paper). London: Overseas Development Institute.

Carrard, N., Neumeyer, H., Pati, B. K., Siddique, S., Choden, T., Abraham, T., et al. (2020). Designing human rights for duty bearers: making the human rights to water and sanitation part of everyday practice at the local government level. Water 12, 378. doi: 10.3390/w12020378

Casey, V., and Crichton-Smith, H. (2020). System Strengthening for Inclusive, Lasting WASH that Transforms People's Lives: Practical Experiences from the SusWASH Programme. London: WaterAid. Available online at: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/informe-de-aprendizaje-global-de-suswash.pdf (accessed September 19, 2022).

Chopra, J. (2002). Building state failure in east timor. Dev. Change 33, 979–1000. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.t01-1-00257

Clarke, N. E., Dyer, C. E. F., Amaral, S., Tan, G., and Vaz Nery, S. (2021). Improving uptake and sustainability of sanitation interventions in timor-leste: a case study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1013. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031013

Crewe, E., and Harrison, E. (1998). “Development aid: success and failures,” in Whose Development? An Ethnography of Aid, eds E. Crewe and E. Harrison (London: Zed Books) 1–24.

Croissant, A., and Lorenz, P. (2018). “Timor-leste: challenges of creating a democratic and effective state,” in Comparative Politics of Southeast Asia, eds. A. Croissant and P. Lorenz (Cham: Springer).

Cummins, D. (2010). Democracy or democrazy? Local experiences of democratization in Timor-Leste. Democratization 17, 899–919. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2010.501177

Doerfel, M. L., and Taylor, M. (2017). The story of collective action: the emergence of ideological leaders, collective action network leaders, and cross-sector network partners in civil society. J. Commun. 67, 920–943. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12340

Elbers, W., and Schulpen, L. (2013). Corridors of power: the institutional design of North-South NGO partnerships. Voluntas 24, 48–67. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9332-7

Escobar, A. (1992). Imagining a post-development era? critical thought, development and social movements. Social Text 31/32, 20–56. doi: 10.2307/466217

Escobar, A. (1995a). Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Escobar, A. (1995b). “Imagining a post-development era,” in Power of Development, ed. J. Crush (London: Routledge), 211–227.

Eversole, R. (2003). Managing the pitfalls of participatory development: some insight from Australia. World Dev. 31, 781–795. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00018-4

Eyben, R., Kabeer, N., and Cornwall, A. (2008). Conceptualising Empowerment and The Implications for Pro-Poor Growth: A Paper for the DAC Poverty Network. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies.

Fletcher, G., Brimacombe, T., and Roche, C. (2016). Power, Politics and Coalitions in the Pacific: Lessons from Collective Action on Gender and Power (Research Paper). Suva/Birmingham: Pacific Women/Developmental Leadership Program, University of Birmingham.

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2005). Surplus possibilities: post-development and community economies. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 26, 4–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0129-7619.2005.00198.x

Grant, M., Foster, T., Willetts, J., Van Dinh, D., and Davis, G. (2020). Life-cycle costs approach (LCCA) for piped water service delivery: a study in rural Viet Nam. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. 10, 659–669. doi: 10.2166/washdev.2020.037

Grant, M., Megaw, T., Da Costa, L., Weking, E., and Huggett, C. (2019a). Review of the Implementation of WaterAid's Gender Manual and Facilitated Sessions. Sydney, Australia: Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. Available online at: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/review-of-the-implementation-of-wateraids-gender-manual-and-facilitated-sessions-in-timor-leste_0.pdf (accessed September 16, 2022).

Grant, M., Soeters, S., Bunthoeun, I. V., and Willetts, J. (2019b). Rural piped-water enterprises in cambodia: a pathway to women's empowerment? Water 11, 2541. doi: 10.3390/w11122541

Guttenbeil-Likiliki, O. (2020). Creating Equitable South-North Partnerships: Nurturing the Vā and Voyaging the Audacious Ocean Together. Melbourne, VIC: International Women's Development Agency (IDWA).

Hagaman, A. K., and Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? another perspective on Guest, Bunce, and Johnson's (2006) landmark study. Field Methods 29, 23–41. doi: 10.1177/1525822X16640447

Hollander, D., Ajroud, B., Thomas, E., Peabody, S., Jordan, E., Javernick-Will, A., et al. (2020). Monitoring methods for systems-strengthening activities toward sustainable water and sanitation services in low-income settings. Sustainability 12, 7044. doi: 10.3390/su12177044

Honig, D., and Gulrajani, N. (2018). Making good on donors' desire to do development differently. Third World Q. 39, 68–84. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2017.1369030

Horn, J. (2013). Gender and Social Movements Overview Report. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk (accessed September 17, 2022).

Htun, M., and Weldon, S. (2018). The Logics of Gender Justice: State Action on Women's Rights Around the World (Cambridge Studies in Gender and Politics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huggett, C., Da Costa Cruz, L., Geoff, F., Pheng, P., and Ton, D. (2022). Beyond inclusion: practical lessons on striving for gender and disability transformational changes in WASH systems in Cambodia and Timor-Leste. H2Open J. 5, 26–42. doi: 10.2166/h2oj.2022.039

Huston, A., and Moriarty, P. (2018). Building Strong WASH Systems for the SDGs Understanding the WASH System and Its Building Blocks: Working Paper. The Hague: IRC. Available online at: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/084-201813wp_buildingblocksdef_newweb.pdf (accessed September 19, 2022).

Jenkins, M. W., McLennan, L., Revell, G., and Salinger, A. (2019). Strengthening the Sanitation Market System: WaterSHED's Hands-Off Experience. The Hague: IRC. Available online at: https://watershedasia.org/hands-off-where-taking-a-step-back-is-severalsteps-forward/strengthening-the-sanitation-market-system_watersheds-hands-off-experience/ (accessed September 19, 2022).

Kimbugwea, C., Sou, S., Crichton-Smith, H., and Goff, F. (2022). Practical system approaches to realise the human rights to water and sanitation: results and lessons from Uganda and Cambodia. H2Open J. 5, 69. doi: 10.2166/h2oj.2022.040

Latouche, S. (1993). In the Wake of Affluent Society: An Exploration of Post-Development. London: Zed Books.

Mac Ginty, R. (2015). Where is the local? Critical localism and peacebuilding. Third World Q. 36, 840–856. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1045482

MacArthur, J., Carrard, N., Davila, F., Grant, M., Megaw, T., Willetts, J., et al. (2022). Gender-transformative approaches in international development: a brief history and five uniting principles. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 95, 102635. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102635

McCulloch, N., and Piron, L.-H. (2019). Thinking and working politically: learning from practice. Overview to special issue. Develop. Policy Rev. 37, O1–O15. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12439

McGregor, A. (2007). Development, foreign aid and post-development in timor-leste. Third World Q. 28, 155–170. doi: 10.1080/01436590601081955

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage Points – Places to Intervene in a System. The Sustainability Institute. Hartland VT. Available online at: https://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/ (accessed October 10, 2022).

Mizrahi, T., and Rosenthal, B. B. (2001). Complexities of coalition building: leaders' successes, strategies, struggles, and solutions. Soc. Work 46, 63–78. doi: 10.1093/sw/46.1.63

Moore, T., and Skinner, A. (2010). In How to Partner for Development Research, ed K. Winterford (Canberra, Australia: Research for Development Impact Network, RDI), 10. Available online at: https://rdinetwork.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/2020/08/How-to-Partner-for-DevelopmentResearch_fv_Web.pdf (accessed September 10, 2022).

Moriarty, P., Smits, S., Butterworth, J., and Franceys, R. (2013). Trends in rural water supply: towards a service delivery approach. Water Alt. 6, 329–349. Available online at: https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/trends_in_rural_water_supply_-_towards_a_service_delivery.pdf

Nazneen, S. (2019). How Do Leaders Collectively Change Institutions? Birmingham: Developmental Leadership Program (DLP). Available online at: https://www.dlprog.org/publications/foundational-papers/how-do-leaders-collectively-change-institutions (accessed September 19, 2022).

Neely, K. (2019). “Systems thinking and trans-disciplinarity in WASH,” in: Systems Thinking and WASH Tools and Case Studies for A Sustainable Water Supply. Rugby: Practical Action Publishing.

Neely, K., and Walters, J. P. (2016). Using causal loop diagramming to explore the drivers of the sustained functionality of rural water services in timor-leste. Sustainability 8, 57. doi: 10.3390/su8010057

Nhim, T., and Mcloughlin, C. (2022). Local leadership development and WASH system strengthening insights from Cambodia. H2Open J. 5, 469. doi: 10.2166/h2oj.2022.129

Niner, S. L. (2018a). It's Time for Women to Lead in Timor-Leste: Heroes of Timor-Leste Independence Struggle Should Make Way for the Younger Generation. Montrouge: LaCroix International. Available online at: https://international.la-croix.com/news/culture/its-time-for-women-to-lead-in-timor-leste/7603 (accessed September 19, 2022).

Niner, S. L. (2018b). LGBTI lives and rights in Timor-Leste. Diálogos 3, 157–207. doi: 10.53930/27892182.dialogos.3.87

Niner, S. L. (2022). Gender relations and the establishment of the LGBT movement in Timor-Leste. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 93, 102613. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102613

Niner, S. L., and Loney, H. (2019). The women's movement in timor-leste and potential for social change. Polit. Gend. 16, 874–902. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X19000230

Niner, S. L., and Nguyen, T. T. P. T. (2022). “Timor-leste: substantive representation of women parliamentarians and gender equality,” in Substantive Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments, eds. D. K. Joshi and C. Echle (London: Routledge), 159–182.

O'Brien, N. F., and Evans, S. K. (2016). Civil society partnerships: power imbalance and mutual dependence in NGO partnerships. Voluntas 28, 1399–1421. doi: 10.1007/s11266-016-9721-4

Rajbhandari, R. (2014). Women and Girls Rising Together. Asia Pacific Forum on Women Law and Development (APWLD). Available online at: https://apwld.org/women-and-girls-rising-together/ (accessed September 17, 2022).

Rede Feto (2007). Hau Fo Midar, Hau Simu Moruk [I Give Sweetness, I Receive Bitterness]. Dili, Timor-Leste: Rede Feto.

Roche, C., Cox, J., Rokotuibau, M., Tawake, P., and Smith, Y. (2020). The characteristics of locally led development in the Pacific. Polit. Govern. 8, 136–146. doi: 10.17645/pag.v8i4.3551

Roche, C., and Denney, L. (2021). “COVID-19: an opportunity to localise and reimagine development in the Pacific?,” in Reimagining Development: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Doing Development in an Era of Uncertainty, ed G. Varughese (Sydney, NSW: UNSW Institute of Global Development). Available online at: https://www.igd.unsw.edu.au/practice-papers-reimagining-development-how-do-practice-based-approaches-shape-localisation-development (accessed August 2, 2022).

Roche, C., and Kelly, L. (2014). “A changing landscape for partnerships: the Australian NGO experience,” in Rethinking Partnerships in a Post-2015 World: Towards Equitable, Inclusive and Sustainable Development, eds. L. M. Suarez and J. Malonzo (Philippines: IBON International), 60–68. Available online at: http://www.realityofaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/1.A-changing-Landscape-for-partnerships.pdf (accessed July 5, 2022).

Sauser, B. J., Reilly, R. R., and Shenhar, A. J. (2009). Why projects fail? How contingency theory can provide new insights – a comparative analysis of NASA's mars climate orbiter loss. Int. J. Project Manag. 27, 665–679. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.01.004

Schoneberg, J. M. (2017). NGO partnerships in Haiti: clashes of discourse and reality. Third World Q. 38, 604–620. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1199946